Abstract

Several studies have investigated the efficacy and safety outcomes of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF). Herein, this meta-analysis was aimed to compare the effect of NOACs with warfarin in this population. We systematically searched the PubMed database until December 2019 for studies that compared the effect of NOACs with warfarin in patients with AF and HF. Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were abstracted and then pooled using a random-effects model. A total of nine studies were included in this meta-analysis. Compared with warfarin use, the use of NOACs was significantly associated with reduced risks of stroke or systemic embolism (RR = 0.82 (95% CI, 0.73–0.92)), all-cause death (RR = 0.87 (95% CI, 0.80–0.94)), major bleeding (RR = 0.84; (95% CI, 0.74–0.97)), intracranial hemorrhage (RR = 0.50; 95% CI, 0.43–0.59), and hemorrhagic stroke (RR = 0.49 (95% CI, 0.38–0.63)). There were no differences in the risks of ischemic stroke (RR = 0.89 (95% CI, 0.75–1.04)) and gastrointestinal bleeding (RR = 1.11 (95% CI, 0.79–1.55)) in patients treated with NOACs versus warfarin. Compared with warfarin use, the use of NOACs had similar or lower risks of thromboembolic and bleeding events in patients with AF and HF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is regarded as the most common arrhythmia with an increasing risk of death and morbidity [1]. Heart failure (HF) is a highly complex clinical syndrome with a prevalence that increases with age. They often coexist in clinical practice, and HF is an independent risk factor of thromboembolic complications among AF patients. As such, HF is incorporated into the CHA2DS2-VASc score (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age 65–74 years, diabetes mellitus, vascular disease (prior myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, or aortic plaque), female (1 point each), age ≥ 75 years, and prior stroke/transient ischemic attack/thromboembolism (doubled)) for stroke prediction in AF [2]. More recently, several studies have found that HF patients are at increased risks of thromboembolic events regardless of the presence of AF [3, 4]. Prior randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have found that non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are at least as effective as warfarin and could have a better safety profile for stroke prediction in patients with AF [5,6,7,8]. Current guidelines consistently recommend NOACs as the first choice of drugs in AF patients [1, 9, 10]. A number of studies have investigated the efficacy and safety outcomes of NOACs versus warfarin in patients with AF and HF [11,12,13,14].

Two previous systemic reviews including four RCTs have proposed that the NOACs is at least not associated with increased risks of stroke or systemic embolism, major bleeding, and intracranial hemorrhage in HF patients with AF [15, 16]. Nevertheless, the populations in RCTs are generally selected with strict selection criteria, which are sometimes different from the real-world practice [17]. In recent years, several observational studies have investigated the role of NOACs in patients with AF and HF. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to re-assess the efficacy and safety outcomes of NOACs versus warfarin in patients with AF and HF.

Methods

Study search

We systematically searched the PubMed database from inception to December 2019 for studies that reported the efficacy and safety outcomes of any NOAC with warfarin in patients with AF and HF. The following search terms (and their similar terms) were used: atrial fibrillation, heart failure, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, direct oral anticoagulants, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, vitamin K antagonists, and warfarin. We also screened the reference lists of the retrieved studies in order to find the additional studies. No language restrictions were applied during the search in this meta-analysis.

Eligibility criteria

Studies could be included if they met the criteria: (1) RCTs or observational studies that compared the effect of NOACs versus warfarin among patients with AF and HF; (2) any NOAC (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or edoxaban; any dose) versus warfarin; (3) studies reporting at least one of the efficacy or safety outcomes. Efficacy outcomes included stroke or systemic embolism, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and all-cause death, while safety outcomes included major bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage and gastrointestinal bleeding; and (4) effect estimates of the study was adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and its 95% confidence intervals (CIs). If the substantial overlap was found among the different studies, we only included the study with the longest follow-up or largest sample size.

Study selection and data abstraction

We first read the titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies to screen out the available studies. The full texts of these eligible studies were then reviewed in more detail. Two independent reviewers screened all of the retrieved studies in the search. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. In addition, we abstracted the baseline characteristics of the included studies, such as the first author and publication year, type of study, definitions of AF or HF, number of NOACs or warfarin users, type or dose of NOACs, follow-up duration, and outcomes.

Risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality of the RCTs was evaluated according to the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool [18]. The quality of the observational studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa score, which involved the selection of cohorts, comparability of cohorts, and assessment of the outcome [19]. A Newcastle-Ottawa score of < 6 points indicated a low quality [20].

Statistical method

All statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager version 5.30 software (the Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). We applied the Cochrane Q test combined with the I [2] values to assess the heterogeneity across the included studies. P < 0.1 and I2 > 50% indicated a significant heterogeneity, respectively. For each study, we calculated the natural logarithm of the RR (Ln[RR]) and its corresponding standard error (SELn[RR]). And then, Ln[RR] and SELn[RR] were pooled using a random-effects model weighted by the inverse-variance method. In addition, we re-analyzed these analyses with a fixed-effects model in the sensitivity analysis. The subgroup analysis was not performed based on the design of study (RCTs versus observational studies). The possible presence of publication bias was checked by observing the symmetry characteristics of the funnel plots.

Results

Study selection

As shown in Supplemental Fig. 1, a total of nine studies (four RCTs [11,12,13,14] and five observational studies [21,22,23,24,25]) were included in the present meta-analysis. Thereinto, four RCTs were from the sub-analyses of the RE-LY (dabigatran), ROCKET AF (rivaroxaban), ARISTOTLE (apixaban), and ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 (edoxaban) trials, respectively. Baseline characteristics of the included RCTs are shown in Supplemental Table 1. All of the four RCTs had a low risk of bias, whereas all of the five observational studies had moderate-to-high quality.

Efficacy and safety of NOACs versus warfarin

Efficacy

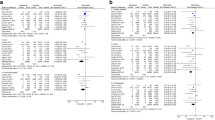

Compared with warfarin use, the use of NOACs was significantly associated with reduced risks of stroke or systemic embolism (RR = 0.82 (95% CI, 0.73–0.92); P = 0.001; I2 = 35%; Fig. 1) and all-cause death (RR = 0.87 (95% CI, 0.80–0.94); P = 0.0007; I2 = 64%; Fig. 2). There was no difference in the risk of ischemic stroke (RR = 0.89 (95% CI, 0.75–1.04); P = 0.15; I2 = 28%; Supplemental Fig. 2) in patients with NOACs versus warfarin.

Random-effects model for comparing the stroke or systemic embolism of NOACs with warfarin in patients with AF and HF. Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; HF, heart failure; NOACs, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants; DA, dabigatran; RIV, rivaroxaban; API, apixaban; EDO, edoxaban; LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; HFpEF, heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error; IV, inverse of the variance

Random-effects model for comparing the all-cause death of NOACs with warfarin in patients with AF and HF. Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; HF, heart failure; NOACs, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants; DA, dabigatran; RIV, rivaroxaban; API, apixaban; EDO, edoxaban; LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; HFpEF, heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error; IV, inverse of the variance

Safety

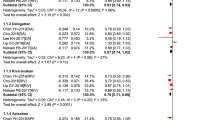

Compared with warfarin use, the use of NOACs was significantly associated with decreased risks of major bleeding (RR = 0.84 (95% CI, 0.74–0.97); P = 0.01; I2 = 82%; Fig. 3), intracranial hemorrhage (RR = 0.50 (95% CI, 0.43–0.59); P < 0.00001; I2 = 0%; Fig. 4), and hemorrhagic stroke (RR = 0.49 (95% CI, 0.38–0.63); P < 0.00001; I2 = 0%; Supplemental Fig. 3). We found no difference in the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (RR = 1.11 (95% CI, 0.79–1.55); P = 0.54; I2 = 89%; Supplemental Fig. 4) in patients with NOACs versus warfarin.

Random-effects model for comparing the major bleeding of NOACs with warfarin in patients with AF and HF. Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; HF, heart failure; NOACs, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants; DA, dabigatran; RIV, rivaroxaban; API, apixaban; EDO, edoxaban; LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; HFpEF, heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error; IV, inverse of the variance

Random-effects model for comparing the intracranial hemorrhage of NOACs with warfarin in patients with AF and HF. Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; HF heart failure; NOACs, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants; DA, dabigatran; RIV, rivaroxaban; API, apixaban; EDO, edoxaban; LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; HFpEF, heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error; IV, inverse of the variance

Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis

For the efficacy and safety outcomes of NOACs versus warfarin, a fixed-effects model analysis produced the similar results with the aforementioned analyses. In subgroup analysis on the design of study, we found no significant interaction between data of RCTs versus observational studies for the outcomes of stroke or systemic embolism, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, major bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage and gastrointestinal bleeding (all Pinteraction > 0.05). However, the use of NOACs versus warfarin decreased the risk of all-cause death in observational studies (RR = 0.80 (95% CI, 0.72–0.88); P < 0.0001; I2 = 67%), but not in RCTs (RR = 0.95 (95% CI, 0.88–1.03); P = 0.19; I2 = 0%) (Pinteraction = 0.009; Fig. 2).

Publication Bias

The publication biases assessed by the funnel plots of the reported efficacy and safety outcomes are shown in Supplemental Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11.

Discussion

In the present analysis, we combined the data of RCTs and observational studies to compare the efficacy and safety outcomes of NOACs with warfarin in patients with AF and HF. Our pooled data indicated that [1] compared with warfarin use, the use of NOACs was associated with the reduced risks of stroke or systemic embolism, all-cause death, major bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, and hemorrhagic stroke [2], there were no differences in the risks of ischemic stroke and gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with NOACs versus warfarin. Re-analyses with a fixed-effects model produced the similar results with the main analyses.

The populations in RCTs are generally selected with strict selection criteria, which are sometimes different from the real-world settings. Our current meta-analysis included the real-world data adding to an already existing meta-analysis including four RCTs. We found no significant interactions between data of RCTs versus observational studies for the efficacy and safety outcomes except all-cause death. As such, our findings suggest that NOACs had similar or lower risks of thromboembolic and bleeding events compared with warfarin in patients with AF and HF. NOACs might be reasonable alternatives to warfarin in patients with AF and HF. The sub-type of heart failure is important and should be included in the further study.

Previously, data from the Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies (COMPASS) trial [26] has indicated that in patients with stable coronary artery disease and sinus rhythm, the use of low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) plus aspirin might decrease the risk of major vascular events compared with the use of aspirin alone. In addition, data from the Cardiovascular Outcome Modification, Measurement AND Evaluation of Rivaroxaban in patients with Heart Failure (COMMANDER-HF) trial [27] has found that in HF patients without AF, low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) is associated with a reduced risk of stroke. A prior meta-analysis including 9490 patients with HF and sinus rhythm has suggested that anticoagulant therapy could decrease the stroke risk but increase the risk of major bleeding [28]. More recently, data from the observational studies suggest that anticoagulant therapy could help decrease the risk of stroke induced by HF [29]. On the other hand, HF patients with the anticoagulant therapy might be also at a high risk of bleeding [30]. However, no studies have been performed to observe the effect of NOACs versus warfarin in patients with with HF and sinus rhythm. HF patients without AF are at increased risks of stroke or death [4, 31]. Based on our current data, the use of NOACs was at least non-inferior to warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with AF and HF.

Limitations

The following limitations should be acknowledged in our current meta-analysis. First, the subgroup analyses based on the type or dosage of NOACs were not performed due to the limiting data. Second, we did not take the time in the therapeutic range of warfarin users into consideration. Third, the residual confounders (e.g., age, baseline chronic conditions) in the real-world studies might exist. Fourth, the different definitions of the studied outcomes might affect our pooled data. Finally, we included both HF patients with reduced ejection fraction and those with preserved ejection fraction for analysis. Further study should include a sub-analysis between preserved and reduced ejection fraction as they represent totally different populations.

Conclusions

Compared with warfarin use, the use of NOACs had similar or lower risks of thromboembolic and bleeding events in patients with AF and HF. The use of NOACs was at least non-inferior to warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with AF and HF.

References

January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Furie KL, Heidenreich PA, Murray KT, Shea JB, Tracy CM, Yancy CW (2019) 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in Collaboration With the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 140(2):R665

Zhu W, Xiong Q, Hong K (2015) Meta-analysis of CHADS2 versus CHA2DS2-VASc for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation patients independent of anticoagulation. Tex Heart I J 42(1):6–15

Adelborg K, Szépligeti S, Sundbøll J, Horváth-Puhó E, Henderson VW, Ording A, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT (2017) Risk of stroke in patients with heart failure. Stroke. 48(5):1161–1168

Kang SH, Kim J, Park JJ, Oh IY, Yoon CH, Kim HJ, Kim K, Choi DJ (2017) Risk of stroke in congestive heart failure with and without atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 248:182–187

Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Halperin JL, Waldo AL, Ezekowitz MD, Weitz JI, Špinar J, Ruzyllo W, Ruda M, Koretsune Y, Betcher J, Shi M, Grip LT, Patel SP, Patel I, Hanyok JJ, Mercuri M, Antman EM (2013) Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. New Engl J Med. 369(22):2093–2104

Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A, Bahit MC, Diaz R, Easton JD, Ezekowitz JA, Flaker G, Garcia D, Geraldes M, Gersh BJ, Golitsyn S, Goto S, Hermosillo AG, Hohnloser SH, Horowitz J, Mohan P, Jansky P, Lewis BS, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Parkhomenko A, Verheugt FWA, Zhu J, Wallentin L (2011) Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. New Engl J Med. 365(11):981–992

Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Berkowitz SD, Fox KAA, Califf RM (2011) Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. New Engl J Med. 365(10):883–891

Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, Wang S, Alings M, Xavier D, Zhu J, Diaz R, Lewis BS, Darius H, Diener H, Joyner CD, Wallentin L (2009) Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. New Engl J Med. 361(12):1139–1151

Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, Castella M, Diener H, Heidbuchel H, Hendriks J, Hindricks G, Manolis AS, Oldgren J, Popescu BA, Schotten U, Van Putte B, Vardas P, Agewall S, Camm J, Baron Esquivias G, Budts W, Carerj S, Casselman F, Coca A, De Caterina R, Deftereos S, Dobrev D, Ferro JM, Filippatos G, Fitzsimons D, Gorenek B, Guenoun M, Hohnloser SH, Kolh P, Lip GYH, Manolis A, McMurray J, Ponikowski P, Rosenhek R, Ruschitzka F, Savelieva I, Sharma S, Suwalski P, Tamargo JL, Taylor CJ, Van Gelder IC, Voors AA, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Zeppenfeld K (2016) 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J 37(38):2893–2962

Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, Albaladejo P, Antz M, Desteghe L, Haeusler KG, Oldgren J, Reinecke H, Roldan-Schilling V, Rowell N, Sinnaeve P, Collins R, Camm AJ, Heidbüchel H, Lip GYH, Weitz J, Fauchier L, Lane D, Boriani G, Goette A, Keegan R, MacFadyen R, Chiang C, Joung B, Shimizu W (2018) The 2018 European heart rhythm association practical guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 39(16):1330–1393

Magnani G, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Murphy SA, Nordio F, Metra M, Moccetti T, Mitrovic V, Shi M, Mercuri M, Antman EM, Braunwald E (2016) Efficacy and safety of edoxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: insights from ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48. Eur J Heart Fail 18(9):1153–1161

Ferreira J, Ezekowitz MD, Connolly SJ, Brueckmann M, Fraessdorf M, Reilly PA, Yusuf S, Wallentin L (2013) Dabigatran compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and symptomatic heart failure: a subgroup analysis of the RE-LY trial. Eur J Heart Fail 15(9):1053–1061

McMurray JJV, Ezekowitz JA, Lewis BS, Gersh BJ, van Diepen S, Amerena J, Bartunek J, Commerford P, Oh B, Harjola V, Al-Khatib SM, Hanna M, Alexander JH, Lopes RD, Wojdyla DM, Wallentin L, Granger CB (2016) Left ventricular systolic dysfunction, heart failure, and the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ Heart Fail 6(3):451–460

van Diepen S, Hellkamp AS, Patel MR, Becker RC, Breithardt G, Hacke W, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Nessel CC, Singer DE, Berkowitz SD, Califf RM, Fox KAA, Mahaffey KW (2013) Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban in patients with heart failure and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Circ Heart Fail 6(4):740–747

Savarese G, Giugliano RP, Rosano GM, McMurray J, Magnani G, Filippatos G, Dellegrottaglie S, Lund LH, Trimarco B, Perrone-Filardi P (2016) Efficacy and safety of novel oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a meta-analysis. JACC Heart Fail 4(11):870–880

Xiong Q, Lau YC, Senoo K, Lane DA, Hong K, Lip GYH (2015) Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) in patients with concomitant atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur J Heart Fail 17(11):1192–1200

Fawzy AM, Yang WY, Lip GY (2019) Safety of direct oral anticoagulants in real-world clinical practice: translating the trials to everyday clinical management. Expert Opin Drug Saf 18(3):187–209

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA (2011) The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 343:d5928

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P (2014) The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 29 Dec 2019

Xue Z, Zhou Y, Wu C, Lin J, Liu X, Zhu W (2015) Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation: evidences from the real-world data. Heart Fail Rev (in press)

Martinez BK, Bunz TJ, Eriksson D, Meinecke AK, Sood NA, Coleman CI (2019) Effectiveness and safety of rivaroxaban vs. warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 6(1):10–15

Amin A, Garcia Reeves AB, Li X, Dhamane A, Luo X, Di Fusco M, Nadkarni A, Friend K, Rosenblatt L, Mardekian J, Pan X, Yuce H, Keshishian A (2019) Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants in older adults with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and heart failure. PLoS One 14(3):e213614

Yoshihisa A, Sato Y, Sato T, Suzuki S, Oikawa M, Takeishi Y (2018) Better clinical outcome with direct oral anticoagulants in hospitalized heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc Disor 18(1)

Adeboyeje G, Sylwestrzak G, Barron JJ, White J, Rosenberg A, Abarca J, Crawford G, Redberg R (2017) Major bleeding risk during anticoagulation with warfarin, dabigatran, apixaban, or rivaroxaban in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Manag Care Spec PH 23(9):968

Friberg L, Oldgren J (2017) Efficacy and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Open Heart 4(2):e682

Connolly SJ, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, Dagenais G, Dyal L, Lanas F, Metsarinne K, O'Donnell M, Dans AL, Ha J, Parkhomenko AN, Avezum AA, Lonn E, Lisheng L, Torp-Pedersen C, Widimsky P, Maggioni AP, Felix C, Keltai K, Hori M, Yusoff K, Guzik TJ, Bhatt DL, Branch KRH, Cook Bruns N, Berkowitz SD, Anand SS, Varigos JD, Fox KAA, Yusuf S, Sala J, Cartasegna L, Vico M, Hominal MA, Hasbani E, Caccavo A, Zaidman C, Vogel D, Hrabar A, Schygiel PO, Cuneo C, Luquez H, Mackinnon IJ, Ahuad Guerrero RA, Costabel JP, Bartolacci IP, Montana O, Barbieri M, Gomez Vilamajo O, Garcia Duran RO, Schiavi LB, Garrido M, Ingaramo A, Bordonava AP, Pelagagge MJ, Novaretto L, Albisu Di Gennero JP, Ibanez Saggia LM, Alvarez M, Vita NA, Macin SM, Dran RD, Cardona M, Guzman L, Sarjanovich RJ, Cuadrado J, Nani S, Litvak Bruno MR, Chacon C, Maffei LE, Grinfeld D, Vensentini N, Majul CR, Luciardi HL, Gonzalez Colaso PDC, Ferre Pacora FA, Van Den Heuvel P, Verhamme P, Ector B, Debonnaire P, Van De Borne P, Leroy J, Schroe H, Vranckx P, Elegeert I, Hoffer E, Dujardin K, Indio DO, Brasil C, Precoma D, Abrantes JA, Manenti E, Reis G, Saraiva J, Maia L, Hernandes M, Rossi P, Rossi Dos Santos F, Zimmermann SL, Rech R, Abib E Jr, Leaes P, Botelho R, Dutra O, Souza W, Braile M, Izukawa N, Nicolau JC, Tanajura LF, Serrano Junior CV, Minelli C, Nasi LA, Oliveira L, De Carvalho Cantarelli MJ, Tytus R, Pandey S, Lonn E, Cha J, Vizel S, Babapulle M, Lamy A, Saunders K, Berlingieri J, Kiaii B, Bhargava R, Mehta P, Hill L, Fell D, Lam A, Al-Qoofi F, Brown C, Petrella R, Ricci JA, Glanz A, Noiseux N, Bainey K, Merali F, Heffernan M, Della Siega A, Dagenais GR, Dagenais F, Brulotte S, Nguyen M, Hartleib M, Guzman R, Bourgeois R, Rupka D, Khaykin Y, Gosselin G, Huynh T, Pilon C, Campeau J, Pichette F, Diaz A, Johnston J, Shukle P, Hirsch G, Rheault P, Czarnecki W, Roy A, Nawaz S, Fremes S, Shukla D, Jano G, Cobos JL, Corbalan R, Medina M, Nahuelpan L, Raffo C, Perez L, Potthoff S, Stockins B, Sepulveda P, Pincetti C, Vejar M, Tian H, Wu X, Ke Y, Jia K, Yin P, Wang Z, Yu L, Wu S, Wu Z, Liu SW, Bai XJ, Zheng Y, Yang P, Yang YM, Zhang J, Ge J, Chen XP, Li J, Hu TH, Zhang R, Zheng Z, Chen X, Tao L, Li J, Huang W, Fu G, Li C, Dong Y, Wang C, Zhou X, Kong YE, Sotomayor A, Accini Mendoza JL, Castillo H, Urina M, Aroca G, Perez M, Molina De Salazar DI, Sanchez Vallejo G, Fernando MJ, Garcia H, Garcia LH, Arcos E, Gomez J, Cuervo Millan F, Trujillo Dada FA, Vesga B, Moreno Silgado GA, Zidkova E, Lubanda J, Kaletova M, Kryza R, Marcinek G, Richter M, Spinar J, Matuska J, Tesak M, Motovska Z, Branny M, Maly J, Maly M, Wiendl M, Foltynova Caisova L, Slaby J, Vojtisek P, Pirk J, Spinarova L, Benesova M, Canadyova J, Homza M, Florian J, Polasek R, Coufal Z, Skalnikova V, Brat R, Brtko M, Jansky P, Lindner J, Marcian P, Straka Z, Tretina M, Duarte YC, Pow Chon Long F, Sanchez M, Lopez J, Perugachi C, Marmol R, Trujillo F, Teran P, Tuomilehto J, Tuomilehto H, Tuominen M, Tuomilehto H, Kantola I, Steg G, Aboyans V, Leclercq F, Ferrari E, Boccara F, Messas E, Mismetti P, Sevestre MA, Cayla G, Motreff P, Stoerk S, Duengen H, Stellbrink C, Guerocak O, Kadel C, Braun-Dullaeus R, Jeserich M, Opitz C, Voehringer H, Appel K, Winkelmann B, Dorsel T, Nikol S, Darius H, Ranft J, Schellong S, Jungmair W, Davierwala P, Vorpahl M, Bajnok L, Laszlo Z, Noori E, Veress G, Vertes A, Zsary A, Kis E, Koranyi L, Bakai J, Boda Z, Poor F, Jarai Z, Kemeny V, Barton J, Mcadam B, Murphy A, Crean P, Mahon N, Curtin R, Macneill B, Dinneen S, Halabi M, Zimlichman R, Zeltser D, Turgeman Y, Klainman E, Lewis B, Katz A, Atar S, Zimlichman R, Nikolsky E, Bosi S, Naldi M, Faggiano P, Robba D, Mos L, Sinagra G, Cosmi F, Oltrona Visconti L, Carmine DM, Di Pasquale G, Di Biase M, Mandorla S, Bernardinangeli M, Piccinni GC, Gulizia MM, Galvani M, Venturi F, Morocutti G, Baldin MG, Olivieri C, Perna GP, Cirrincione V, Kanno T, Daida H, Ozaki Y, Miyamoto N, Higashiue S, Domae H, Hosokawa S, Kobayashi H, Kuramochi T, Fujii K, Mizutomi K, Saku K, Kimura K, Higuchi Y, Abe M, Okuda H, Noda T, Mita T, Hirayama A, Onaka H, Inoko M, Hirokami M, Okubo M, Akatsuka Y, Imamaki M, Kamiya H, Manita M, Himi T, Ueno H, Hisamatsu Y, Ako J, Nishino Y, Kawakami H, Yamada Y, Koretsune Y, Yamada T, Yoshida T, Shimomura H, Kinoshita N, Takahashi A, Yusoff K, Wan Ahmad WA, Abu Hassan MR, Kasim S, Abdul Rahim AA, Mohd Zamrin D, Machida M, Higashino Y, Utsu N, Nakano A, Nakamura S, Hashimoto T, Ando K, Sakamoto T, Prins FJ, Lok D, Milhous JG, Viergever E, Willems F, Swart H, Alings M, Breedveld R, De Vries K, Van Der Borgh R, Oei F, Zoet-Nugteren S, Kragten H, Herrman JP, Van Bergen P, Gosselink M, Hoekstra E, Zegers E, Ronner E, Den Hartog F, Bartels G, Nierop P, Van Der Zwaan C, Van Eck J, Van Gorselen E, Groenemeijer B, Hoogslag P, De Groot MR, Loyola A, Sulit DJ, Rey N, Abola MT, Morales D, Palomares E, Abat ME, Rogelio G, Chua P, Del Pilar JC, Alcaraz JD, Ebo G, Tirador L, Cruz J, Anonuevo J, Pitargue A, Janion M, Guzik T, Gajos G, Zabowka M, Rynkiewicz A, Broncel M, Szuba A, Czarnecka D, Maga P, Strazhesko I, Vasyuk Y, Sizova Z, Pozdnyakov Y, Barbarash O, Voevoda M, Poponina T, Repin A, Osipova I, Efremushkina A, Novikova N, Averkov O, Zateyshchikov D, Vertkin A, Ausheva A, Commerford P, Seedat S, Van Zyl L, Engelbrecht J, Makotoko EM, Pretorius CE, Mohamed Z, Horak A, Mabin T, Klug E, Bae J, Kim C, Kim C, Kim D, Kim YJ, Joo S, Ha J, Park CS, Kim JY, Kim Y, Jarnert C, Mooe T, Dellborg M, Torstensson I, Albertsson P, Johansson L, Al-Khalili F, Almroth H, Andersson T, Pantev E, Tengmark B, Liu BO, Rasmanis G, Wahlgren C, Moccetti T, Parkhomenko A, Tseluyko V, Volkov V, Koval O, Kononenko L, Prokhorov O, Vdovychenko V, Bazylevych A, Rudenko L, Vizir V, Karpenko O, Malynovsky Y, Koval V, Storozhuk B, Cotton J, Venkataraman A, Moriarty A, Connolly D, Davey P, Senior R, Birdi I, Calvert J, Donnelly P, Trevelyan J, Carter J, Peace A, Austin D, Kukreja N, Hilton T, Srivastava S, Walsh R, Fields R, Hakas J, Portnay E, Gogia H, Salacata A, Hunter JJ, Bacharach JM, Shammas N, Suresh D, Schneider R, Gurbel P, Banerjee S, Grena P, Bedwell N, Sloan S, Lupovitch S, Soni A, Gibson K, Sangrigoli R, Mehta R, I-Hsuan Tsai P, Gillespie E, Dempsey S, Hamroff G, Black R, Lader E, Kostis JB, Bittner V, Mcguinn W, Branch K, Malhotra V, Michaelson S, Vacante M, Mccormick M, Arimie R, Camp A, Dagher G, Koshy NM, Thew S, Costello F, Heiman M, Chilton R, Moran M, Adler F, Comerota A, Seiwert A, French W, Serota H, Harrison R, Bakaeen F, Omer S, Chandra L, Whelan A, Boyle A, Roberts-Thomson P, Rogers J, Carroll P, Colquhoun D, Shaw J, Blombery P, Amerena J, Hii C, Royse A, Singh B, Selvanayagam J, Jansen S, Lo W, Hammett C, Poulter R, Narasimhan S, Wiggers H, Nielsen H, Gislason G, Kober L, Houlind K, Boenelykke Soerensen V, Dixen U, Refsgaard J, Zeuthen E, Soegaard P, Hranai M, Gaspar L, Pella D, Hatalova K, Drozdakova E, Coman I, Dimulescu D, Vinereanu D, Cinteza M, Sinescu C, Arsenescu C, Benedek I, Bobescu E, Dobreanu D, Gaita D, Iancu A, Iliesiu A, Lighezan D, Petrescu L, Pirvu O, Teodorescu I, Tesloianu D, Vintila MM, Chioncel O (2018) Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in patients with stable coronary artery disease: an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 391(10117):205–218

Zannad F, Anker SD, Byra WM, Cleland JGF, Fu M, Gheorghiade M, Lam CSP, Mehra MR, Neaton JD, Nessel CC, Spiro TE, van Veldhuisen DJ, Greenberg B (2018) Rivaroxaban in patients with heart failure, sinus rhythm, and coronary disease. New Engl J Med 379(14):1332–1342

Ntaios G, Vemmos K, Lip GY (2019) Oral anticoagulation versus antiplatelet or placebo for stroke prevention in patients with heart failure and sinus rhythm: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Stroke:32384623

Chung S, Kim T, Uhm J, Cha M, Lee J, Park J, Park J, Kang K, Kim J, Park HW, Choi E, Kim J, Kim C, Lee YS, Shim J, Joung B (2019) Stroke and systemic embolism and other adverse outcomes of heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction in patients with atrial fibrillation (from the comparison study of drugs for symptom control and complication prevention of atrial fibrillation [CODE-AF]). Am J Cardiol (in press)

Schrutka L, Seirer B, Duca F, Binder C, Dalos D, Kammerlander A, Aschauer S, Koller L, Benazzo A, Agibetov A, Gwechenberger M, Hengstenberg C, Mascherbauer J, Bonderman D (2019) Patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction are at risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Med 8(8):1240

Melgaard L, Gorst-Rasmussen A, Lane DA, Rasmussen LH, Larsen TB, Lip GY (2015) Assessment of the CHA2DS2-VASc score in predicting ischemic stroke, thromboembolism, and death in patients with heart failure with and without atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 314(10):1030–1038

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Under the directions of Jian Hu and Jianyong Ma, Faxiu Chen, Yunguo Zhou, Qin Wan, and Peng Yu contributed to the whole process of this meta-analysis including study design, literature search, data curation, methodology, data analysis, data interpretation, and draft writing. Jian Hu and Jianyong Ma revised the original draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 148 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, F., Zhou, Y., Wan, Q. et al. Effect of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Fail Rev 26, 1391–1397 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-020-09946-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-020-09946-8