Abstract

Chinese higher education policy texts appear to suggest that training ‘para-diplomats’ is a goal of China’s international student recruitment. However, few studies have considered the ways such policies are recontextualised and implemented at the institutional (meso-) level and become integral to students’ career pathways after graduation. To address this paucity, I purposefully selected two Chinese higher education institutions (HEIs) and undertook an ethnographic study to explore their policy work of translation. Basil Bernstein’s notions of classification and framing are employed here to nuance the mechanisms by which hidden messages were deliberately sent out by case-study institutions in everyday practices and processes. The findings reveal that routine aspects of university life, including visual cues, events and activities, and interactions between teachers and students, differed in their strengths of classification and framing, which either expanded or limited the range of career pathways that international students could envisage or progress to. This study offers a valuable contribution to the literature on higher education policy ‘implementation studies’, especially in the Chinese context, adding to our understandings about the powerful influence of the hidden curriculum on international students’ career choice. The implications of China’s experiences are discussed in terms of the role played by HEIs in the nexus of shaping graduates’ career choice and enhancing the national soft power.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The existing body of research on policy texts surrounding internationalisation of higher education suggests that international students are commonly positioned as a source of income and as future skilled workforce who can drive economic growth within the neoliberal structuring of higher education in the Global North (see, for example, Levatino et al., 2018; Lomer, 2017a). In contrast to other major destination countries such as the USA, the UK, and Australia, the recruitment of international students in Chinese higher education system is undergirded by a public diplomacy rationale and conceived as a means of enhancing the national soft power (Pan, 2013; Wu, 2019). Hosting more international students and training them ‘to tell China’s story and spread China’s voice’ (Ministry of Education, 2015), with particular focus on those from peripheral nation states, have been imagined as the ‘soft infrastructure’ of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and an instrument of realising China’s foreign policy goals (Cheng & Koh, 2022).

It is made clear in national policy discourses that higher education institutions (HEIs) should serve the nation’s diplomatic strategies, be directly responsible for offering a high standard of international education, and support international students to continue engaging with China (Ministry of Education, 2010, 2018a, 2019). In the Quality standards for international students in higher education institutions (Draft) (Ministry of Education, 2018a) and Management measures for the recruitment and training of international students in schools (Ministry of Education, 2017a), the abstractions of high-quality international higher education are translated into more contextualised practices, including curricular offerings. In addition to delivering course content, offering guidance counselling services, and organising extracurricular activities, such as interactions with teachers and guidance counsellorsFootnote 1 (‘fudao yuan’ in translation), orientation events, learning support, national conditions education and cultural experiences, internships, visits, seminars, etc. are foregrounded as an intended and required function of HEIs. These less explicit ways of teaching, as argued by Hong and Hardy (2022), p. 11, are ‘brand building activities’, which aim to work in tandem with the formal curriculum and create a cadre of alumni who have China-related competencies, be appreciative of ‘Chinese values’, and choose to work in the interests of China over the long-term (Ministry of Education, 2018a).

Whilst there is a level of consensus within the extant literature around the discursive constructions of international students as ‘para-diplomats’ and tools for enhancing the nation’s global influence in Chinese policy texts, little empirical research has actually been carried out with the aim of exploring how HEIs respond to and implement these international higher education policies in specific institutional contexts. A handful of studies have examined international students’ attitudes towards academic experiences in China (see, for example, Haugen, 2013; Tian & Lowe, 2018; P. Yang, 2018), using these factors as a proxy for the soft power potential of international higher education. This demonstrates a limited and narrow understanding of curricular offerings in Chinese HEIs as well as a broader range of potential mechanisms through which China’s diplomatic ends may be achieved. Though formal teaching and learning are highly relevant, they do not go into any great detail about how HEIs invest in the more hidden aspects of schooling or the so-called brand building activities (Hong & Hardy, 2022), which is explicitly associated with alumni’s connection and global influence accumulation in policy documents (Ministry of Education, 2017b).

Therefore, the aim of this study is to examine how China’s higher education internationalisation policy is implemented by meso-level policy actors, and ultimately impacts career pathways of international students. In particular, I ask: How do Chinese HEIs align with macro-level policy and adopt particular practices to support international students with a China-related career building? International students’ post-study aspirations and progression to China-related careers are foregrounded as a proxy for soft power because they indicate whether graduates have a lasting tie to China (see Lomer, 2017b), can forge connections between China and foreign countries (Gao & Liu, 2020), sympathise with China interests, and possibly influence public opinion (see Wilson, 2014).

To answer the research question, I draw on data collected through ethnographic research undertaking in two Chinese HEIs—Mountain Normal University and Seaside Vocational College—highlighting the ‘hidden curriculum’ that took place in everyday practices and processes where students gained knowledge of the career landscape and understood the ‘rules of game’, but also felt comfortable making particular career choices (see Wotherspoon, 2009). I offer a fine-grained analysis of the ways in which non-elite Chinese HEIs cope with the policy expectation and endeavour to shape international students’ career choice relevant to China’s broader geopolitical aims. The main contribution to the existing literature is that this article shifts from investigating policy creation and objects and takes the initiative in looking at institutional implementation and support for macro policy in the Chinese context.

The practice of a hidden curriculum and career choice

The hidden curriculum refers to ‘the tacit teaching of students of norms, values, and dispositions that goes on simply by their living in and coping with the institutional expectations and routines of schools day in and day out’ (Apple, 1979, p. 13). From this perspective, the reproduction of culture takes place both within and outside the formal curriculum; students may gain consciousness of the ‘rule of the game’ through implicit messages they receive from their everyday interactions with teachers (Gillborn & Youdell, 1999), as well as the ‘expressive order’ embodied in every aspect of educational institutions (Bernstein, 1975, pp. 38-39). In addition to the range of subjects presented to students, Neve and Collett (2018) argue that the discursive practices operating within the hidden curriculum can have a powerful influence on the learning and professional development of students.

Whilst the extant literature underlines the potential impact of the hidden curriculum on medical students’ career choices (see, for example, Hill, Bowman, Stalmeijer, & Hart, 2014; Phillips & Clarke, 2012), there remains surprisingly little scholarship exploring implicit messages carried within Chinese HEIs and how they are playing a role in shaping international students’ career choices and pathways upon graduation. Though policy documents do refer to the role and contributions of HEIs in achieving the China’s diplomatic ends through guidance counselling services and extracurricular activities (Ministry of Education, 2017a, 2018a), they do not refer explicitly how to organise these alumni connections building activities and being opaque has been a key feature of policymaking process in China (see Beeson, 2018). This suggests the dynamics between macro-level policy and HEIs practices as well as variations in institutional responses to policy priorities worthy of examination.

Translating policy discourses into contextualised practices: a Bernsteinian perspective

In understanding ‘school effects’ on students mobility, a number of important studies have tended to draw upon the concept of institutional habitus, which extends Bourdieu’s (1990) work on the individual habitus, to help explain the ways in which individual institutions play a significant role in shaping and influencing young people in progressing to higher education (see, for example, Reay, 1998; Reay, David, & Ball, 2001) or imagining the field of possibilities after graduation (see, for example, Lee, 2021; Xu & Sthal, 2023). Atkinson (2011), p. 338 critiques that the concept reduces the school or university to ‘one monolithic unit’, strongly associated with intake, and consequently masks any internal heterogeneity in schooling processes. In an attempt to address some of these issues, Bernstein’s (2000) notions of classification and framing are deployed here to nuance the mechanism by which norms, values, dispositions, and expectations are implicitly transmitted and taught through the hidden curriculum, where international students are instilled ambition and empowered to pursue China-related careers.

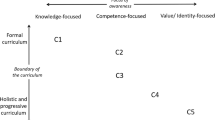

Bernstein’s (2000) theorisation on the pedagogic device allows a socio-analysis of the way in which stated mandated educational policies are re-produced and translated into action ‘at the level of schools, classrooms … ’ (Fitz, Davies, & Evans, 2005, p. 18). In particular, his paired concepts of classification (structure relations) and framing (interaction practices) can help nuance how the hidden messages are conversed into pedagogic communication in mundane aspects of school (university) life and thereby the examination of the kinds of hidden messages sent out about the ‘right’ kinds of career choices. Classification refers to the extent of insulation between categories (e.g. contents, resources, agents and discourses) at an organisational level; in the case of stronger classification, categories are well separated from each other, whereas the boundaries between categories are more permeable and elastic in the case of weaker classification. For example, boundaries can be created by the separation of resources and students into different groups (see, for example, Donnelly, 2014, 2015), as well as by marking out China-related careers as a highly differentiated, distinct post-study choice. Framing refers to the degree of control on communication in the pedagogical relationship between teachers and students. Donnelly and Evans (2016), p. 81 note that ‘the strength of framing determines the range of options presented’; strongly framed messages result in reduced options, whilst weaker framing might open up a plethora of possible options.

Classification and framing are valuable concepts in the sense they nuance cultural and social dimensions of schooling independent of institutions’ intake. By highlighting the institutional properties, they unpack the underlying structures of power and control within educational settings. Although widely applied to understand a variety of educational problems, particularly the structuring of curriculum and pedagogic practices (see, for example, Xu, 2021; Bourne, 2008; Singh, 2002), this couplet has not been deployed in the ‘choice’ research, with a notable exception of Michael Donnelly’s work. Theoretically, this article intends to expand our understanding of Bernstein’s notion to the Chinese context, by looking at how Chinese HEIs translate condensed codes of policy codes into practical work, thus recognising the importance of meso support in shaping, and potentially transforming, their engagement with China after graduation.

The study

This paper draws on research carried out in two Chinese HEIs, anonymised here ‘Mountain Normal University’ and ‘Seaside Vocational College’, which are based in the same provincial locality in China. These two institutions were selected on the basis of their good reputation in international education and international cooperation (details will be discussed later), and my familiarity with both the institutions and teachers also provided easy access to participants.

Brief notes about two case universities

Mountain Normal University is a comprehensive public university located in a prefecture-level city in East China. As one of the key provincial universities, it specialises in teacher education and since its establishment in 1959, 210,000 out of 300,000 (70%) of its graduates have been taking up a career in the education sector. The university was designated by the Ministry of Education as a National Base for Education Assistance and Development, Research Centre for China-South Africa People-to-People Exchange, Research Centre for the Promotion of Chinese language in Africa, and Teacher Selection and Training Centre for Confucius Institutes. In addition, it has been authorised to establish Confucius Institutes in Cameron, Tanzania, Mozambique, and South Africa and recruit international students from multiple continents. The university, especially its College of International Education, distinguishes itself as a leading institution in African studies, international student education and Chinese as a Foreign Language education, and their enrolled international students who were recruited as research participants for this study were also full of praise for this university in interviews.

Seaside Vocational College, by contrast, is located in a highly developed port city on southeast coast of China. Historically, it absorbed ‘left over’ students with ‘less desirable’ academic performance and suffers considerable prejudice in Chinese society. However, the institution is a national exemplary Vocational Education and Training (VET) college given its outstanding performance at engaging with local industry and enterprises and training highly skilled technicians. As the VET base of the Ministry of Commerce and leading institution of the Belt and Road Alliance for Industry and Education Collaboration (BRAIEC), Seaside is committed to providing both domestic and international students with vocationally oriented programs and helping Chinese vocational education take on the world. Since 2007, it has trained 3691 industrial officials and technicians from 123 developing countries, established a vocational college in Benin and assisted local Chinese companies in expanding business in countries of the BRI.

Though both Mountain Normal University and Seaside College strategically target at the African market and have a great proportion of African international students, they have very different intake profiles and other in-school factors. Whilst Mountain mainly admits international students who have learned Chinese and passed the HSK 3 and HSK 4Footnote 2 in its overseas Confucius Institutions, Seaside relied much more on word-of-mouth recommendations and its incoming students usually have to study Chinese from scratch. Other in-school nuances will be discussed in the next section.

Data collection and analysis

Ethnographic research was carried out in these two case institutions, where I paid close attention to the more taken for granted aspects of campus life, in an attempt to understand the hidden curriculum in their routine practices and processes. This included observation (and note-taking) of daily routines, important events and activities (two days a week at each institution in March–June 2021), interviews with teachers/administrators, guidance counsellors, and students, and the collection of artefacts (e.g. photographs of cultural landscapes, students’ work, and news feed).

An important part of the student participant recruitment occurred through word of mouth. Teachers of each institution put me in contact with a student they thought might be interested, and the students then recruited a few more peers. Based on these initial existing contacts, more potential participants were identified and recruited through this snowballing sampling technique (Cohen et al., 2011). A large portion of the students were from African countries and their ethnic backgrounds reflected the two HEIs’ strategic approach to the recruitment of international students from peripheral states and upholding national interests. Semi-structured interviews took place with around 14–15 students (aged 20–33) in each institution, which explored their work-related experiences at university and plans for the future. Two teachers (one subject teacher/administrator and one guidance counsellor) at each of these two institutions were also invited to take part in one-to-one interviews, which lasted approximately one to two hours each and focused on their reflections about the hidden curriculum.

Data were transcribed and thematically analysed in relation to the research question (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Initially, the code of the ‘hidden curriculum’ was assigned to raw data to tease out all of the tacit teaching that took place within the two institutions (see Apple, 1979). This generated additional inductive codes, including visual cues, events and activities, and interactions with teachers and alumnus, which enabled a thicker and more comprehensive elaboration on the bulk of the data (Joffe, 2012). As Bernstein’s (2000) theorisation was used, deductive codes (i.e. stronger classification, weaker classification, stronger framing, and weaker framing) were also applied to the raw data, which may fully capture nuances and qualitative differences of hidden messages transmitted and received in each case institution, thus contributing to the formation of the thematic map with regard to international students’ post-study career aspirations and choices.

Progressing to Chinese-related careers: hidden messages at two Chinese HEIs

Visual cues: buildings, resources, and cultural artefacts

The two case universities contained a wide range of visible cues in relation to educational and career choices. These included the design of buildings, interiority, cultural landscapes, and artefacts, as well as partnerships with industry, government, and a plethora of organisations. The selection, ordering, and arrangement of these often sent out implicit messages about China-related career choices.

Stronger classification of post-graduation choices was evident from the exhibition of visual cues at Seaside College, whose website declared its commitment to supporting the nation’s BRI and providing international students with high-quality vocationally oriented programs. A gorgeous building—BRI Alliance mansion—has been constructed recently, in order to cater to international students, raise the international reputation, and strengthen the BRI sustainable infrastructure connectivity. Within the building, the walls were hung with countless photos and text descriptions of the college’s partnership with governments, industries, and enterprises, and how its graduates benefitted from the integration between entrepreneurism and education (Fig. 1). In other words, the expressive order of Seaside, including expectations, conduct, character, and manners (Bernstein, 1975), was embodied in the building and cultural landscape, sending out the very overt messages about the institution’s ethos, an image of conduct, a moral order, post-graduation career choices, and importantly what constituted the most ‘right’ kinds of choices students should make. That said, working for/with Chinese enterprises and participating in the BRI are the route to follow.

In contrast, a different organisation of space was observed at Mountain Normal University, which sent out more weakly classified messages about post-graduation choices. The spatial design of the building entry was simple and plain, enabling international students to feel that they are no different from their domestic peers. Though slogan ‘Learning Chinese, double your world’ was displayed in the most conspicuous position of the entry and indicative of the importance of learning the Chinese language, it did not explicitly single out specific employment that students should consider or pursue. A bunch of national flags were placed in the corridor and created an international and diverse ambience, which was unique and has not been observed in other schools in this university (Fig. 2). Other cultural artefacts, including graduation and other photos, however, were stored in a specific, small room, and were not accessible to students in everyday life. As Yeoh, the guidance counsellor of Mountain noted:

Our school doesn’t make an effort to do these things, and we tend to treat international students as same as our domestic students. (Yeoh, male, 26-year-old, guidance counsellor)

This remark reflected Mountain’s alignment with macro-level policy which requires a shift in the management mode of international students from ‘special care’ to ‘assimilation management’ in China (Ministry of Education, 2018a, 2019). A blurred boundary of student groups was indicated, which emphasised a sense of similarities and integration between students rather than any differences and separation in institutional practices and processes.

Interactions between teachers and students

A further socio-cultural dimension of everyday practices to consider here is the interactions that took place between international students and teachers. These interactions also carried messages, which broadened or narrowed the post-study career choice. At Seaside, the management of international student education indicated stronger classification and framing:

Our school has many guidance counsellors, some of them are careers advisors, some of them are academic advisors and some are in charge of international students’ lives and organising activities. I am a career advisor, responsible for coordinating international students and enterprises. (Mr Luo, male, 31-year-old, guidance counsellor)

Within the institution, guidance counsellors were classified as ‘international students’ guidance counsellors’ and ‘domestic students’ guidance counsellors’, and each of them had different responsibilities, that is, career advisors, academic advisors, and life coaches. This separation contributed to the explicit marking out international students as a distinct group and it was taken for granted that career advisors should provide international students with specific guidance on career planning and professional development from time to time. Indeed, student participants mentioned how Mr Luo talked to them on a regular basis and checked on their thoughts and career plans in interviews.

While undertaking ethnographic observations at Seaside, I ran across small talk which took place in the corridors. It was between a teacher who had a liaison with local enterprises and an international student:

Teacher: Doing business is good… You’re quite fit for doing business, certainly…

Student: I want to start a small restaurant here, I like cooking… I want to be a chef… There’re no African restaurants here.

Teacher: Have you considered getting start with importing and exporting goods between Africa and China? Many of my Africans students are doing this… it’s lucrative.

Student: Yeah, yeah – it’s good… very flexible… and it’s also an option.

Teacher: Oh right… If you want to do it, I can recommend you some factories here…

(Fieldnotes, 2021/06/17)

Whilst the teacher might have only be aware of ‘doing business’ as the career pathway, stronger framing was, nonetheless, evident here from the single option that she presented and neglected to respond to the student’s proposal of starting an African restaurant in China. The student loved cooking and he has already sniffed out some opportunities for his catering business, but the only type of business mentioned by the teacher was ‘importing and exporting goods between Africa and China’. This stronger framing sent out messages that importing Chinese goods to Africa was probably the most desirable career that should be pursued, because of its lucrativeness. The teacher was exerting a greater degree of control in this conversation, as she made it less possible for information about choices other than the import and export business to be accessed. Any other types of business, including the one which interested her students, were not brought up within this interaction.

The stronger framing of interactions with teachers at Seaside appeared to instil the values and dispositions shared within the institution, and this might legitimise international students’ sense of being ‘business material’. Chance conversations and interviews with them revealed their business savvy and ambitions; they were well acquainted with Chinese enterprises (e.g. Huawei, Alibaba), China’s investment in the BRI, and business opportunities presented, and most of them already had business ideas and partners. An example is Rugema, who liaised with a Chinese and planned to register a company in Tanzania:

After returning home next month, I will start my own business right away. I will have a company that produces and sells soap. (Rugema, male, 33-year-old, Tanzania)

Rugema opened his WeChat which contained a long contact list, showing me his Chinese partners and photographs of the soap (Chinese brand) he was interested in. Like him, it appeared that all students were made acutely aware of endless business opportunities brought by China’s presence in their home countries and imagined the business route after the completion of their studies in China.

At Mountain, however, the approach taken by teachers reflected weakly framed messages sent out by the institution: career plans and choices are students’ privacy, and hence teachers and guidance counsellors were reluctant to talk about this matter in everyday interactions. This was common refrain among teachers and international students:

We don’t offer too much career advice because students are adults, and we want them to discover what they want to do through observations and practices. (Yeoh, male, 26-year-old, guidance counsellor)

When I met my supervisor, what we discussed most was my thesis… and we rarely talked about careers... (Valentine, male, 23-year-old, Nigeria)

Unlike Seaside, career-focused interactions with teachers and alumnus were absent at Mountain; instead, students were allowed to ‘discover what they want to do through observations and practices’. This weakly framed approach did not prioritise one specific career option for the group of students; rather, it gave them a greater degree of freedom to find out for themselves about what to do in the future, while opening up a wider range of career options other than starting a business.

A notable exception is Lucinilde who described how teachers at Mountain ‘persuaded’ her to become a Chinese language teacher in her home country, Mozambique, after graduation:

I want to be a Chinese language teacher because in my country [Mozambique], there are few local teachers teaching Chinese. Teachers here all said teaching Chinese fitted me well, because of my beautiful pronunciation. (Lucinilde, female, 22-year-old, Mozambique)

Stronger framing of post-study choice was evident from Lucinilde’s account, as she described how all teachers judged and commended her to have ‘the edge’ of ‘beautiful pronunciation’, which marked out a kind of identity and conveyed information about the career pathway. Whilst all students (both domestic and international ones) studying Chinese language in this normal university were made aware of teaching Chinese as one of the possible careers in the future, teachers’ praise and advice separated Lucinilde from other students, sending out a highly visible message that teaching Chinese is the most ‘appropriate’ route to follow. Probably, it was also this particular arrangement that further strengthened her resolve and ligitimised her sense of being a Chinese teacher in Mozambique.

Events and activities

In addition to the visual cues and interactions which were observed within the Seaside Vocational College, the kinds of events and activities also sent out stronger classified and framed messages about the career option available to its international students. Teachers at Seaside organised career preparation activities both on and off campus, which resonated with the ethos (i.e. serving the BRI and interest of the nation), organisational practices (i.e. an integration of industry and education), and education status of its institution (i.e. offering vocationally oriented programs). For example, Mr Luo, who was in charge of international students’ career advice, emphasised the ways in which China’s grand strategy was embedded within the very fabric of career-specific events and activities within the institution, highlighting China-related, business-focused careers as the ‘right’ kinds of choices that international students should opt for:

Our college provides professional and vocational training programs to government officials, technicians and entrepreneurs from developing countries, and most of them are from African countries. We organised tea parties for these officials, entrepreneurs and our students. They were extremely excited to see their compatriots and wanted to give our international students opportunities. Some of them were very senior and managing big enterprises in Africa, and they wanted our students to work as agents and help manage their business in China. (Mr Luo, male, 31-year-old, guidance counsellor)

During the tea parties, only international students were invited to attend and communicate with senior government officials, technicians, and entrepreneurs. This process by which domestic students were excluded appeared to be a purposeful one, given the likelihood that African international students were more likely to be selected as ‘agents’ and help their compatriots manage business in China. The institution was exerting a greater degree of power and control within the context, carrying implicit messages about who were perceived to be the ‘right’, ‘qualified’ candidates (i.e. African students) for this party and what was a possible job (i.e. business agent in China).

The Chinese language teacher, Ms Han, also recalled the experience of her strongly classifying and framing workshops, thus creating boundaries around business-oriented jobs and other possibilities which reduced the range of options open to students in terms of their career choices:

I took international students to visit local enterprises, as I know some cross-border e-commerce companies want to further expand the market in their countries, so I just took them to these companies, to have a talk. I also engaged them in activities such as e-commerce livestreaming and entrepreneurship competitions. I hope to sow a seed in their hearts, like ‘I want to start a business in China or in my home countries’, and I believe such natural learning occurring in everyday life works. (Ms Han, female, 37-year-old, Chinese language teacher)

Ms Han was making explicit here that she wanted to ‘sow a seed in their [international students’] hearts’ and encouraged them to ‘start a business in China or in their home countries’. The marking out of ‘local enterprises’, ‘cross-border e-commerce companies’, ‘e-commerce livestreaming’, and ‘entrepreneurship competitions’ were evident from the routine processes she put in place for supporting international students in learning and career decision-making. These excursions and internships again separated international students from their domestic peers and other China-related employments.

Those who attended Seaside similarly expressed how they developed the entrepreneurial skills from employability-related experience and aspired to progress to China-related, business focused careers as their future pathways. It was evident from their narratives that they felt capable of becoming successful entrepreneurs and did not display any feelings of doubt in their knowledge, capabilities, and chances of succeeding:

I’ll start up my business in China, logistics, it’s part of my big plan, to connect Africa to China. (Alex, male, 25-year-old, Burundi)

I want to create an application where people can sell and buy things, like Alibaba and Taobao, but a local one, for my country. I want to be Jack Ma in Burkina Faso, to solve problems for people. (Patrick, male, 21-year-old Burkina Faso)

Their feelings and aspirations reflected the kinds of messages sent out by Seaside: that all international students should engage with China and pursue a business-focused career after graduation; they are all ‘high-level business talents’ and therefore should ‘have a go’. Though it is hard to say to what extent the institutional practices might have had a bearing on the decision-making of these students, as ‘young people are not necessarily passive recipients of such knowledge’ (Donnelly, 2015, p. 86). Indeed, other social categories, such as class position, race, and gender, are often found to be influential in shaping international students’ aspirations and transitions after graduation (see, for example, Findlay, Prazeres, McCollum, & Packwood, 2017; Lee, 2021). The impact of the institutional practices might become clearer when comparing how students fared in a more weakly classified and framed context, such as Mountain.

Mountain is a normal university specialised in teacher education and the arrangement of resources and support at the institutional level, as such, reflected the peculiarities and specificities of the institution. In addition to lectures and workshops such as ‘How to be a qualified teachers’, ‘How to promote and teach Chinese in Africa’, and ‘Chinese language volunteer teachers’ pre-departure education meeting’ that I ran across and attended during my fieldwork, Ms Mow, the Chinese language teacher and deputy dean, also provided a first-hand account of institutional practices:

Our school will arrange overseas Confucius Institutes for students’ internships… Students also work as teaching assistants to assist professors with creating teaching materials, delivering learning materials and such; they observe how to teach, write a summary and learn how to teach well. (Ms Mow, female, 53-year-old, Chinese language teacher and administrator)

Students, such as Lancino and Shuhua, who have been learning Chinese at Mountain for five and three years respectively, also suggested how a variety of teaching internship jobs were provided by the institution and teachers which shaped their aspirations for being a teacher after graduation:

I am working as an intern in a local kindy now, and the school recommended internship to me. I found I really love kids and I enjoy the feeling of sharing knowledge. I think I’ll be a teacher after graduation, either an English teacher in China or a Chinese teacher at home. (Lancino, male, 24-year-old, Madagascar)

One of my friends is doing an internship job as a teaching assistant on campus. She talked a lot about her internship, like how to dress to attract students’ attention, and I really look forward to it! (Shuhua, female, 22-year-old, Kenya)

These excerpts reflected interrelationship between cultural practices and traditions, stores of career resources, and social capital within the institution, which led to opportunities and students’ imagined careers. Most students at Mountain saw teaching as a feasible, expected, and normalised transition for them and reacted to chances that arose. However, it was not only about knowledge of teaching and understanding the ‘rules of the game’ (Apple, 1979), but was also about feeling comfortable taking up this career. If they had not been enrolled in the Chinese language program and especially in a normal university with established resources and networks, it was unlikely that they would be able to access to internships in Chinese universities and overseas Confucius Institutes and hence felt ‘fitted in’ and comfortable with this choice.

Though it appeared that teaching as a viable career option was made highly visible and prominent at Mountain, my ethnographic fieldwork and conversations with participants revealed that the institution also allowed students to take time off in order to attend other events and activities. This was evidenced in multiple activities documented in my fieldnotes:

… Today a couple of students went to a local museum and work as volunteer docents… They learned objects displayed in the museum’s galleries by themselves first, before writing the scripts and leading the tours... (Fieldnotes, 2021/03/23)

… The guidance counsellor announced an ‘exploring culture’ activity in the class and students were invited to work as deliverymen and experience Chinese lifestyles and ways of working… (Fieldnotes, 2021/05/11)

Given the finite amount of time available within education institutions, the selection, ordering, and arrangement of content to fill this constrained time indicate what is prioritised as most important (Ball, Hull, Skelton, & Tudor, 1984). In this sense, institutional timetables carry implicit messages about what is most important and what teachers should transmit and students should be learning. Unlike Seaside, we can see here that work-integrated activities available at Mountain were more diverse and weakly framed, and the institution exerted less control by presenting a wide range of China- or Chinese language-related extra-curricular activities off campus. This expanded the range of possible career pathways and gave students more autonomy in exploring and deciding what they want to try and should be doing. For example, Xiaole also recalled the experiences of attending different events and activities at Mountain, which helped him decide what routes and options were most appropriate for him:

There’re many opportunities at Mountain. I taught Chinese students Swahili. I am also filming lives in China, to introduce Chinese culture to my country [Tanzania]. I also took part in the Chinese Poetry Recitation Competition and Chinese Song Singing Competition… I don’t think I’ll teach Chinese after graduation because I found my Chinese is not good enough… I’ve found what I’m good at through these competitions and activities. (Xiaole, male, 26-year-old, Tanzania)

The kinds of messages Xiaole was in receipt from the practice of the hidden curriculum may have shaped his perception about himself, as he evaluated his Chinese as ‘not good enough’ and distanced himself from teaching it. Attending Mountain, and being left to decide for himself what as appropriate for him (based on his interests and capabilities), could have meant that his negative perceptions of his Chinese language competency in relation to peers may have influenced his career choices.

Cases such as Xiaole are obviously not rare but common among international students enrolled at Mountain. A number of them also negatively positioned themselves against their peers in terms of Chinese language competency. Meanwhile, they further illustrated a plethora of events and activities organised by the school opened up various possibilities. It is clear that these students were not differentially positioned by teachers in terms of being ‘international students’, and the weaker classificatory and framed messages sent out by Mountain made less distinct a particular ‘teaching’ identity. As such, students’ aspirations have not been narrowed in the same way at Seaside, as they had more autonomy in considering where and what careers they might like to progress to.

Discussion and concluding remarks

This paper has explored some of the ways in which the two Chinese HEIs recontextualised and implemented macro-level policy through the hidden curriculum and sent out different kinds of messages to their international students about what they should to, in terms of their post-graduation career choices. Mountain Normal University did not make explicit to students what is the ‘right’ kind of career, whilst Seaside Vocational College sent out messages that made clear a business route should be taken. In this sense, Seaside might be criticised for ‘being too involved and thus to some extent inhibiting the trajectories of young people’, while Mountain could be praised for ‘empowering young people, enhancing their confidence and independence as they weave their own way through their myriad of possible choices’ (Donnelly, 2015, p. 98). Although these two institutions shared different educational and communicative processes, it appears that all students felt comfortable making particular career choices, but also have been instilled with aspirations to progress to China-related careers and continue engaging with China after graduation.

As state governed HEIs, the two case universities were negotiating between (and blending) the nation’s diplomatic strategies and taking full paly of their own potential resources, thus displaying different institutional choices and HE practices. They coincidentally pedagogised policy discourses through the practice of the curriculum as stipulated by the Quality standards for international students in higher education institutions (Draft) (Ministry of Education, 2018a), including visual cues, interactions between teachers and students, and their events and activities. However, they also expressed contrasting perceptions of management mode (i.e. ‘special care’ at Seaside and ‘assimilation management’ at Mountain) and expectations of the occupational destinations of their alumni (i.e. businessmen at Seaside and more viable options at Mountain) at the meso level. While they were constrained by power, cultivating ‘para-diplomats’ through the hidden curriculum (classification), the HEIs made meaning of official texts in relation to raising alumni’s career aspirations and enacted policies through complex communication processes within their own agencies (framing). Bernstein (2000) notes that when a text moves from its original site of policy production to a pedagogic site, it creates a space where challenge, change, and disruption can take place. In the Chinese higher education context, however, I argue that the policy process of fleshing out indicates HEIs’ dynamism and innovation in aligning with the nation’s aspirations and ambitions to re-emerge as a global superpower (Pan, 2013), as they also actively took institutional traditions, stores of career resources, and social capital into consideration and endeavoured to pursue their own goals of educating and developing students’ employability skills. For example, Seaside’s exclusion of domestic students from the tea parties can be a powerful device, signalling strong boundaries between international and domestic students and their possible career pathways.

Wilson (2014) highlights occupations such as senior government officials, journalists, or university lectures as desirable ‘positions of power’ that could multiple individual alumni’s attitudes and disproportionately influence public opinion. This suggestion appears to parallel to the assumption made in Chinese policy texts that all international students recruited by China’s HEIs should be ‘young elites’, ‘future leaders’, or ‘potential opinion leaders’ (see, for example, Ministry of Education, 2017b, 2018a). This is a flaw given the total international enrolment (492,185 in 2018) and a vast number of them flocking into provincial universities or even vocational colleges in China (Gong & Huybers, 2021; Xu, 2021), who are less likely to move into positions of influence in their post-study mobility and/or career trajectories. As ‘soft power can be ‘high’, targeted at elites, or ‘low’, targeted at the broader public’ (R. Yang, 2007, p. 24), I argue that those ‘grassroots’ international students epitomise a force to promote inter-civilisation exchange, drive economic growth, and deepen diplomatic relations from below, and accumulating soft power through ordinary alumni is also possible. Their employability and onward mobility, for example, not only matters to an international brand of China’s higher education (Hong & Hardy, 2022), but also is crucial to forward China’s economic and political interest (e.g. promoting China around the world and willingness to do business with China (Ministry of Education, 2018b).

Understanding the kinds of hidden messages Chinese HEIs sent out to international students about career choices is important on a number of different levels. Firstly, this article paradigmatically shifted from investigating policy creation to policy implementation, illustrating the dynamic natures of education policy in the Chinese context. Secondly, I captured instances of the ways in which provincial institutions aligned with the nation’s grand strategy, creating a cadre of alumni who have China-related competencies and formed part of the ‘soft infrastructure’ of the BRI (Cheng & Koh, 2022). It is important to note that although less prestigious institutions are limited by their intake, their particular cultures and practices can still be influential in supporting and potentially transforming international students’ involvement with China in the long run. Finally, this study also demonstrated the potential impact of the hidden curriculum in shaping the identity and professional development of students. Chinese HEIs’ practices and experiences of utilising the hidden curriculum as a useful tool to empower students to make active choices about post-study careers and pathways could be drawn upon in some regions of the world, where the public diplomacy rationale is strong in international education policy-space.

Change history

31 August 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01101-0

Notes

Guidance counsellors in Chinese higher education, or ‘fudao yuan’ in translation, are trained personnel ‘tasked with keeping close tabs on their student charges to ensure that their beliefs and behaviour do not violate approved boundaries’ (Perry, 2020, p. 10).

The HSK (hanyu shuiping kaoshi), translated as the Chinese Proficiency Test, is an international standardised test of Chinese language proficiency, which assesses non-native Chinese speakers’ abilities in using the Chinese language in their daily, academic, and professional lives. Test takers who are able to pass the HSK (Level III) can communicate in Chinese at a basic level in their daily, and those who pass the HSK (Level IV) can converse in Chinese on a wide range of topics and are able to communicate fluently with native Chinese speakers.

References

Apple, M. (1979). Ideology and curriculum. Routledge.

Atkinson, W. (2011). From sociological fictions to social fictions: some Bourdieusian reflections on the concepts of ‘institutional habitus’ and ‘family habitus’. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 32(3), 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2011.559337

Ball, S., Hull, R., Skelton, M., & Tudor, R. (1984). The tyranny of the ‘devil’s mill’: Time and task at school. In S. Delamont (Ed.), Readings on interaction in the classroom (pp. 41–57). Methuen.

Beeson, M. (2018). Coming to terms with the authoritarian alternative: The implications and motivations of China’s environmental policies. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 5(1), 34–46.

Bernstein, B. (1975). Class, codes and control (Volume 3): Towards a theory of educational transmission (Vol. 3). Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, critique (Revised ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Polity Press.

Bourne, J. (2008). Official pedagogic discourse and the construction of learners’ identities. In N. H. Hornberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of language and education (pp. 41–52). Springer.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cheng, Y. E., & Koh, S. Y. (2022). The ‘soft infrastructure’ of the Belt and Road Initiative: Imaginaries, affinities and subjectivities in Chinese transnational education. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 43(3), 250–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjtg.12420

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th ed.). London: Routledge.

Donnelly, M. (2014). The road to Oxbridge: Schools and elite university choices. British Journal of Educational Studies, 62(1), 57–72.

Donnelly, M. (2015). Progressing to university: Hidden messages at two state schools. British Educational Research Journal, 41(1), 85–101.

Donnelly, M., & Evans, C. (2016). Framing the geographies of higher education participation: Schools, place and national identity. British Educational Research Journal, 42(1), 74–92.

Findlay, A., Prazeres, L., McCollum, D., & Packwood, H. (2017). It was always the plan’: International study as ‘learning to migrate. Area, 49(2), 192–199.

Fitz, J., Davies, B., & Evans, J. (2005). Education policy and social reproduction: Class inscription & symbolic control. Routledge.

Gao, Y., & Liu, J. (2020). International student recruitment campaign: Experiences of selected flagship universities in China. Higher Education, 80, 663–678.

Gillborn, D., & Youdell, D. (1999). Rationing education: Policy, practice, reform, and equity. Open University Press.

Gong, X., & Huybers, T. (2021). International student flows into provincial China – The main motivations for higher education students. Higher Education Research & Development, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1981254

Haugen, H. Ø. (2013). China's recruitment of African university students: Policy efficacy and unintended outcomes. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 11(3), 315–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2012.750492

Hill, E., Bowman, K., Stalmeijer, R., & Hart, J. (2014). You’ve got to know the rules to play the game: How medical students negotiate the hidden curriculum of surgical careers. Medical education, 48(9), 884–894.

Hong, M., & Hardy, I. (2022). China’s higher education branding: Study in China as an emerging national brand. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 1–21.

Joffe, H. (2012). Thematic analysis. In D. Harper & A. R. Thompson (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners (pp. 209–223). John Wiley & Sons.

Lee, J. (2021). A future of endless possibilities? Institutional habitus and international students’ post-study aspirations and transitions. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 42(3), 404–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2021.1886907

Levatino, A., Eremenko, T., Molinero Gerbeau, Y., Consterdine, E., Kabbanji, L., Gonzalez-Ferrer, A., Jolivet-Guetta, M., & Beauchemin, C. (2018). Opening or closing borders to international students? Convergent and divergent dynamics in France, Spain and the UK. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 16(3), 366–380.

Lomer, S. (2017a). Recruiting international students in higher education: Representations and rationales in British policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lomer, S. (2017b). Soft power as a policy rationale for international education in the UK: a critical analysis. Higher Education, 74(4), 581–598.

Ministry of Education. (2010). 国家中长期教育改革和发展规划纲要 (2010-2020年) Outline of China’s national plan for medium and long-term education reform and development. Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China

Ministry of Education. (2015). 北京大学完善来华留学管理服务 开创留学生教育新局面 [Peking University improves the management service for international students in China and creates a new situation for the education of international students]. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s6192/s133/s134/201502/t20150211_185795.html

Ministry of Education. (2017a). 学校招收和培养国际学生管理办法 [Management measures for the recruitment and training of international students in schools]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-06/02/content_5199249.htm

Ministry of Education. (2017b). 与46个国家和地区学历学位互认! “一带一路”教育在行动 [Academic degree mutual recognition with 46 countries and territories! “One Belt One Road” education in action]. http://www.moe.edu.cn/s78/A20/moe_863/201706/t20170620_307369.html

Ministry of Education. (2018a). 来华留学生高等教育质量规范 (试行) [Quality standards for international students in higher education institutions. Draft]. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A20/moe_850/201810/t20181012_351302.html

Ministry of Education. (2018b). 一带一路国家留学生占留学生总数过半 Students from “One Belt One Road” countries make up more than half of the total number of international students. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s5147/201809/t20180929_350383.html

Ministry of Education. (2019). 质量为先,实现来华留学内涵式发展 [Quality comes first, to achieve the development of connotation-oriented studying in China]. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s271/201907/t20190719_391532.html

Neve, H., & Collett, T. (2018). Empowering students with the hidden curriculum. The clinical teacher, 15(6), 494–499.

Pan, S.-Y. (2013). China’s approach to the international market for higher education students: Strategies and implications. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 35(3), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2013.786860

Phillips, S. P., & Clarke, M. (2012). More than an education: the hidden curriculum, professional attitudes and career choice. Medical education, 46(9), 887–893.

Reay, D. (1998). ’Always knowing’ and ‘never being sure’: Familial and institutional habituses and higher education choice. Journal of Education Policy, 13(4), 519–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093980130405

Reay, D., David, M., & Ball, S. (2001). Making a difference?: Institutional habituses and higher education choice. Sociological Research Online, 5(4), 14–25.

Singh, P. (2002). Pedagogising knowledge: Bernstein’s theory of the pedagogic device. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 23(4), 571–582.

Tian, M., & Lowe, J. (2018). International student recruitment as an exercise in soft power: A case study of undergraduate medical students at a Chinese university. In X. Du & A. Härkönen (Eds.), International students in China: Education, student life and intercultural encounters (pp. 221–247). Palgrave Macmillan.

Wilson, I. (2014). International education programs and political influence: Manufacturing sympathy? Palgrave Macmillan.

Wotherspoon, T. (2009). The sociology of education in Canada: Critical perspectives. Oxford University Press.

Wu, H. (2019). Three dimensions of China’s “outward-oriented” higher education internationalization. Higher Education, 77(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0262-1

Xu, W. (2021). Fostering affective engagement in Chinese language learning: A Bernsteinian account. Language and Education, 36(3), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2021.1936543

Xu, W., & Sthal, G. (2023). International habitus, inculcation and entrepreneurial aspirations: International students learning in a Chinese VET college. Globalisation, Societies and Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2023.2193316

Yang, P. (2018). Compromise and complicity in international student mobility: The ethnographic case of Indian medical students at a Chinese university. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 39(5), 694–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2018.1435600

Yang, R. (2007). China’s soft power projection in higher education. International Higher Education, 9(46), 24–25.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China – Centre for Language Education and Cooperation (general project) [grant number: 22YH45C].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: In this article reference citation “Author, 2023” and “Author, 2022” should have been “Xu & Sthal, 2023” and “Xu, 2021”. The original article has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, W. Progressing to China-related careers: unveiling the hidden curriculum in Chinese international higher education. High Educ 87, 1709–1725 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01086-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01086-w