Abstract

Dominant maternal ideologies impinge upon the career progression of academic mothers and non-mothers. Using “narratology” as a theoretical lens, this article offers insights into the working lives of academic mothers and non-mothers by drawing upon narratives collected by phenomenologically interviewing Palestinian women academics working at Palestinian universities. The analysis of the emerging persistent narratives shows that, as women, both mothers and non-mothers are influenced by socially constructed notions of “motherhood” and are accordingly put at a disadvantage within academia. In Palestine’s conservative, patriarchal context, academic non-mothers are expected to shoulder the burden of care within their families and to extend their mothering capacity to their students and co-workers. Furthermore, this study contributes to the contemporary debates on the tensions that exist between the prevailing discourses of the “altruistic mother” and the “career woman,” as well as the institutional demands that restrict women’s ability to simultaneously fulfill their work expectations and domestic roles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Within the extant literature on women academics, much attention has been devoted to the experiences of mothers and to how the ideology of motherhood impedes their ability to achieve a healthy work/life balance and to progress to higher academic positions (Dickson 2020; Huopalainen and Satama 2019; Leonard and Malina 1994; Ollilainen 2019; Raddon 2002; Ward and Wolf-Wendel 2012). Less attention, however, has been given to the impact of motherhood on non-mothers and on their experiences in academia. In this exploratory study, it is argued that, within higher education institutions, the ideology of motherhood influences both academic non-mothers and mothers.

In adopting the conceptual lens of “narratology” (Boje 2001), and by using “narrative infrastructures” (Deuten and Rip 2000) and “meta-conversations” (Robichaud et al. 2004) as analytical tools, this study seeks to locate the narratives emerging from the micro-stories of day-to-day interaction told by academic mothers and non-mothers, and to show how these individual narratives are shaped by institutionalized practices within both the work and family domains. By focusing on what women “say,” this study expounds “narrative elements, such as sequence, character and plot expressed in talk [which] reflect and structure people’s understandings of what they are doing, of who they are, [and] of what roles they do or can play” (Fenton and Langley 2011, p. 1176).

The motivation to explore the narratives of Palestinian academic mothers and non-mothers was initially triggered by Ramsay and Letherby’s (2006) study on the experiences of non-mothers in higher education, which demonstrates the inferior position they hold in comparison with academic men and mothers. Basing their work on two earlier studies of motherhood and academia (i.e., Leonard and Malina 1994; Munn-Giddings 1998), Ramsay and Letherby (2006) concluded that dominant maternal ideologies critically shape the experiences of both academic mothers and non-mothers and have major consequences for non-mothers in the work domain.

This article diverges from Ramsay and Letherby’s (2006) findings in three important respects that, together, frame its purpose. First, instead of focusing on the experiences of non-mothers alone, it explores the narratives of both academic mothers and non-mothers to develop an understanding of how women consume macro-level narratives. Secondly, it extends the analysis to a novel and marginalized context—i.e., occupied Palestine—where a conventional view of gender roles is predominantly upheld and where a mixture of forces (e.g., gender, patriarchy, religion, and colonialism) constrains women’s liberties and opportunities; in doing so, it provides a juxtaposition between the experiences of Palestinian women academics and women academics in other contexts. Thirdly, by taking an eclectic, receptive approach to each participant’s individualized social situation, this paper offers a nuanced interpretation of Ramsay and Letherby’s (2006) schematic articulation of “motherhood” as a mere impeding force. In this context, the following research question is addressed:

What role does motherhood play in shaping the academic careers of mothers and non-mothers?

It is important to note, however, that the use, throughout the paper, of the term “non-mothers” to refer to single or married childfree women does not in any way represent an acknowledgment of any demarcation lines categorizing women; it is merely a reflection of the terminology employed in the relevant literature. This is in keeping with this paper’s original intention, which is to make such lines less stringent.

This paper is organized as follows. First, it offers an overview of the status of women in Palestine, followed by a review of the pertinent literature. Then, it describes and justifies its research setting, methodological approach, and analytical techniques. Subsequently, it presents the findings in a structured way to show how the dominant macro-level narratives shape the research participants’ micro-level actions. It concludes by discussing the findings in relation to the existing literature and by making suggestions for future research.

Women in Palestine

In the context of occupied Palestine, women face a wide array of social, economic, and political challenges. According to Aghabekian (2019), the extent of women’s engagement in society and decision-making has been critically shaped by a long period of historical colonialism and oppression exercised against all Palestinians. This period extends over the 1917–1948 British Mandate, the 1948 Palestinian exodus (Al-Nakbah), throughout the repercussions of the 1993 Oslo Accords, and the enduring struggle linked to the longstanding colonial Israeli occupation (Sabella and El-Far 2019). Furthermore, as is the case in other conservative Arab Middle Eastern countries, Palestinian women’s participation in social life has been significantly constrained by the male-dominated (patriarchal) culture and the discriminatory social norms prevailing in their society (Aghabekian 2019; Sultan 2016). Drawing upon Hattab (2012), Sultan (2016) indicated that, alongside their sisters in Middle Eastern societies, Palestinian women continue to be subjected to social customs and practices that severely restrict their rights and opportunities, as well as to a patriarchal structure that reinforces traditional gender roles and expectations (Al-Dajani and Marlow 2013; Aruri 2018; Fakher 2018; Hattab 2012; PCBS 2015).

From the nineteenth century onwards, Palestinian women have demonstrated ever increasing degrees of participation in politics and leadership, which have grown markedly with the increasing restrictions and pressures placed by the occupying authorities upon the everyday realities of Palestinians (Aghabekian 2019). All over Palestine, women were engaged in civil disobedience during the first and second intifadas, cooperated in forming committees and charitable societies aimed at supporting the local community (James 2013; Richter-Devroe 2005), and also participated in what Johnson and Kuttab (2001, p. 37) termed “mother activism” in reference to informal forms of activism—e.g., “when older women sheltered youth and defied soldiers.” This new reality has contributed to challenging and somewhat changing some of the conventional attitudes and perceptions regarding women and their roles in the Palestinian society and public life (Aghabekian 2019). However, despite the increasing rates of educational attainment achieved by Palestinian women (UNDP 2015), their presence in leadership and decision-making positions remains considerably lower than that of men, and their voices are still dominated by their male peers in various contexts, including academia.

In occupied Palestine, there are 48 licensed and accredited higher education institutions, 31 of which operate in the West Bank (MoEHE 2018). During these institutions’ academic year 2017/2018, women constituted a little over 60% of the overall student body and only 23% of the academic staff (MoEHE 2018). Besides the effects of restrictive social norms and practices, women academics at Palestinian universities—along with their male colleagues—struggle with overwhelming teaching loads and a lack of resources and facilities. Their working lives are also significantly constrained by Israeli occupation policies and practices, which seek to deprive academics of their basic human rights and academic freedom: they experience frequent course cancelations and disruptions and are themselves subject to unlawful administrative detentions. Their daily commute to and from work is obstructed by temporary and permanent checkpoints and roadblocks, and their ability to travel abroad for academic conferences or research is considerably restricted (Scott 2019; Visweswaran 2015). These restrictions, coupled with difficulties in arranging visits for international academics (due to Israel’s stringent visa policies; see Scott 2019), aggravate the feelings of isolation and disconnectedness that already exist among Palestinian academics.

Women in academia

There is convincing evidence that the situation of women academics has improved in regard to the policy reforms stimulated by socio-cultural changes (e.g., paid maternity leave, the possibility of extending their tenure clock, and increased protection from deliberate discrimination in recruitment, promotion, and workload allocation procedures) (Acker and Armenti 2004; KELA 2017; Ollilainen 2019; Probert 2005). These reforms have led to a rise in women’s representation among higher education academics across the world, including the Middle East. This upturn, however, is disproportionate to women occupying leadership positions, that is, positions of power in the academic hierarchy (Karam and Afiouni 2014). Table 1 shows that, while their participation is improving, women remain largely under-represented in occupied Palestine’s higher academic positions (MoEHE 2017).

The persisting discrepancy between women’s presence among academic staff and their representation in senior positions has given rise to many studies aimed at exploring the status of women academics within modern Western societies (Mirick and Wladkowski 2018; Ollilainen 2019), as well as in other, typically marginalized, contexts like South Africa and the Middle East (Bhana and Pillay 2013; Dickson 2020; Mahabeer et al. 2018). Being largely concerned with the experiences of academic mothers, most such studies tend to explain women’s susceptibility to remaining in lower and less secure positions as a result of being caught between two “greedy institutions”—i.e., the university and the family (Acker 1980; Leonard and Malina 1994; Rhoads and Gu 2012). Within gendered universities, women academics are confronted with a “double bind” (Ramsay and Letherby 2006); they are expected to be competent, unemotional, and impartial while, at the same time, to act out their motherhood role vis-à-vis their students and colleagues. They are also entrusted with tasks that go beyond the typical demands of academic work; tasks that, as Probert (2005) suggested, are intelligibly associated with women (e.g., student welfare and pastoral care). Within the family, traditional gender roles require women, including academics, to contend with greater responsibilities for family work (Dickson 2020; Eliou 1988; Romanin and Over 1993), hence reducing their ability to rely upon the “power of absence from home for work” (Probert 2005, p. 69).

Women academics, moreover, experience what scholars call the “double burden” that emanates from having to simultaneously fulfill domestic and career responsibilities, which spawns “subtle and persistent” ways that put women at a disadvantage (Britton 2017; Huppatz et al. 2018). The underlying assumption here is that women are inclined to conform to social expectations, which impose greater family-related responsibilities upon them. Bailyn (2003, p. 139) maintained that women academics are normally portrayed as falling short of the ideal image of the perfect academic as “someone who gives total priority to work and has no outside interests and responsibilities” (Hermanowicz 2009; Magadley 2019). In the same vein, numerous scholars have cited the obstacles to women academics’ career progression caused by the onerous duties of motherhood and of the household (Magadley 2019; Romanin and Over 1993; Wolf-Wendel and Ward 2006). Romanin and Over (1993), for instance, indicated that women are more inclined than men to subordinating career advancement to marriage, childcare, and domestic duties; Wilton and Ross (2017) suggested that women academics devote more time and energy to childcare at the expense of research; and, Magadley (2019) posited that women experience more frequent career interruptions than men due to family-related circumstances, and that this has detrimental consequences for their remuneration and success as academics (see Lovejoy and Stone 2012). However, Naz et al. (2017) found that although, within a traditional context like Pakistan, women academics find it difficult to maintain a balance between work and family obligations, they often receive substantial support from parents and spouses, which contradicts the popular notion that women within conservative societies only encounter resistance to their career aspirations (see Dickson 2020).

Despite the predominance of the domestic responsibilities thesis within the existing literature, some scholars tend to favor explanations that underline the growing shift in higher education institutions towards the “managerial university,” and how this shift is reinforcing women’s subordination in academia (Grummell et al. 2009; Huppatz et al. 2018; Kenny 2017; Saunderson 2002). From this perspective, it is recognized that higher education institutions have been pressured to progressively embrace the ethos of “new managerialism,” which turns universities into “enterprises” (Huzzard et al. 2017). This involves the adoption of private-sector values and practices in the management of universities, including an emphasis upon governance and accountability, a move towards market orientation and efficiency, the intensification of competition, and pressure to secure non-governmental funding (Huopalainen and Satama 2019; Nikunen 2012). According to Grummell et al. (2009), the introduction of these values and practices has given rise to expectations of performativity (Kallio et al. 2016) that only “carefree” employees can meet; as women are less likely to be “carefree,” for them to succeed in the gendered university is almost impossible. Scholars who share similar standpoints assert how the growth of new managerialist culture in higher education is subjecting women to increased difficulties, making them more vulnerable (Huppatz et al. 2018; Nikunen 2012): they are allocated heavy teaching and administrative workloads while also being required to meet a number of performance expectations related to research output and external funding acquisition (Nikunen 2012). Taking a more radical approach, Huopalainen and Satama (2019) highlighted the incompatibility between motherhood and academia, indicating that mothers’ experiences are especially challenging within the masculinized context of higher education. Ward and Wolf-Wendel (2012, p. 7) acknowledged that women who are sincerely concerned about their success in the academic profession often find themselves effectively obliged to forgo the idea of having children.

Concerning the notion of “motherhood” and its influence—the focus of the current enquiry—the prevailing literature abounds with evidence showing that being a mother critically shapes women’s experiences in academia. Among the earliest studies to explore the challenges faced by women both inside and outside academia is that of Leonard and Malina (1994), who, viewing mothers as the most marginalized individuals in academia, attributed the relative rarity of women holding high-ranking academic positions to the issues related to bearing and raising children. Another defining study is that of Munn-Giddings (1998), which largely builds its arguments upon those of Leonard and Malina (1994). In an autobiographical sketch, Munn-Giddings concluded that, while women are generally at a disadvantage within academic institutions, those with children are even more so. As could be expected, these early initiatives have been sustained within the work of other more contemporary scholars, for instance, Ollilainen’s (2019) examination of women academics’ experiences of motherhood in America and Finland, and how the different policy frameworks adopted in those countries affect the ways in which these women manage their work and family obligations during maternity leave. Ollilainen (2019) highlighted the notion that despite the presence of family-friendly policies, women still felt pressured to be productive and to maintain a presence at work while being on maternity leave. Similarly, Dickson’s (2020) exploration of the perceptions of spousal support and of how it influences the lives and careers held by academic mothers working in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Dickson (2020) showed that while women reported receiving spousal support, they perceived this support to be not sufficiently practical or useful. Moreover, Huopalainen and Satama (2019)—as mothers (-to-be) and early-career researchers—reflected in their autoethnographic study upon their negotiated reality in relation to maternal experiences within the ever-changing expectations of “academia” and “motherhood,” showcasing that motherhood is not always a negative experience in the workplace. Another instance is found in Bhana and Pillay’s (2013) exploration of the lived experiences of women academics working at a South African university, where the authors focused upon how South African women academics negotiate the demands of home and work, highlighting that discriminatory gender relations work to reinforce the inferior status of women within higher education institutions.

While acknowledging the aforementioned arguments, this study resists the prevailing narrow conceptualization that allocates domestic responsibilities exclusively to mothers, centered around the idea that women with and without children hold different perspectives of the nature of domestic duties. Instead, it argues that motherhood, as an ideology, shapes the experiences of every woman, regardless of her social status (married or single, with or without children), and that all women are predisposed to issues linked to domestic responsibilities. The existing conceptions of motherhood and domestic duties contribute to creating confusion between the abstract concept of being a mother and the everyday social reality of human experiences. These depictions are presumed to overlook the possibility that women may exercise agency and resistance in order to improve their positions within both their families and workplaces, and thereby challenge the conventional rhetoric that represents them as incompetent. Furthermore, it is argued that these conceptions pay little attention to the changing nature of families, which tends toward a somewhat more egalitarian attitude in regard to domestic duties. The current articulations of domestic duties thus remain limited, not only to particular women, but more so to the specific line of tasks derived from childcare.

This paper develops its arguments by adopting the conclusion reached by Ramsay and Letherby (2006): the artificiality of separating academic mothers from non-mothers. With their groundbreaking research—which presents an illuminating discussion of the realities of childfree academic women—the authors challenged the spurious line dividing academic mothers and non-mothers. Ramsay and Letherby’s (2006) personal accounts—together with those of their childfree academic women colleagues—have uncovered distinctive insights into the situation of academic non-mothers, which is as challenging, as their status is disadvantaged, as that of academic mothers. Contrary to the findings of Leonard and Malina (1994) and Munn-Giddings (1998), Ramsay and Letherby (2006) demonstrated how motherhood equally influences academic non-mothers and mothers, whereas both are expected to abide by the expectations of womanhood, most of which characterize the “altruistic” mother; non-mothers are incorrectly perceived as having no obligations outside academia, which makes them more susceptible to place work at the center of their lives and devote to it the time and energy that mothers cannot (Ramsay and Letherby 2006).

Although this study takes Ramsay and Letherby’s (2006) main conclusion—i.e., that motherhood affects non-mothers as well as mothers, as its point of departure—it makes three distinctive contributions to the available body of knowledge pertaining to women academics. First, in contrast to Ramsay and Letherby’s (2006) specific concern with the experiences of academic non-mothers, this study explores the narratives of both mothers and non-mothers and demonstrates how the institutionalized practices found within both the university and household spheres shape women academics’ experiences, irrespective of their social status. Second, by investigating the experiences of academic mothers and non-mothers embedded within the Palestinian context, this study adds to the very limited body of literature on women academics working in turbulent and marginalized societies, especially those defined by colonialism, oppression, patriarchy, and conservatism—like occupied Palestine—who have to deal with the additional constraints associated with a prolonged colonial occupation and the resultant socio-economic disadvantages (Granerud 2012; Rought-Brooks et al. 2010; Sabella and El-Far 2019). Finally, and in spite of the formidable evidence substantiating the deterring effect of motherhood and the household upon women academics’ career progression (Raddon 2002; Ramsay and Letherby 2006; Wolf-Wendel and Ward 2006), this study attempts to explore unorthodox interpretations of the notion of motherhood and its influence. This entails probing beyond pre-established conceptions and considering those contemporary perspectives that highlight the empowering aspects of motherhood in the workplace (see Huopalainen and Satama 2019).

Methodology

This article develops its arguments through narrative data collected via the face-to-face phenomenological interviewing of Palestinian women academics who were working full-time at universities in the West Bank, Palestine. The choice of phenomenological interviews is supported by scholars (e.g., Sekaran and Bougie 2009) who consider them to be particularly instrumental in facilitating in-depth understandings of other individuals’ narratives.

The sample was selected purposively on the basis of characteristics relevant to this study. To enable the identification of the similarities and differences in the shared narratives of mothers and non-mothers, the sample included 14 participants, divided equally between mothers and non-mothers, and thus exceeded Onwuegbuzie and Leech’s (2007) recommendation of three per group. This sample size proved appropriate when it subsequently turned out that the last few interviews generated ideas and themes largely analogous to those generated by earlier ones—i.e., when theoretical saturation has been attained (Guest et al. 2006). Although it is recognized that the use of small samples may constrain the generalizability of any findings (Bhattacherjee 2012), the intention of this study is not to obtain statistically generalizable inferences, but to produce local knowledge and understandings that offer fine-grained and context-specific accounts.

Furthermore, to reflect the diversity that exists in the population of Palestinian women academics, the participants were selected from different age groups and academic disciplines, and included women who, at the time, held leadership positions and were actively engaged in research. All mothers, with one exception, expressed their conscious decision of having just one or two children. Among the non-mothers, some identified themselves as being childless by choice, and others as being unwillingly childless. Others still expressed their intention to become mothers in the near future. Table 2 provides some relevant socio-demographic information about the study sample.

To further corroborate the insights offered by the participants, and to develop a more holistic understanding of the situation of women academics at Palestinian universities, three semi-structured interviews were conducted with policy-makers in higher education. The first, held with the Palestinian Minister of Education and Higher Education (MHE), was aimed at examining the effect of policy-making, at the sectoral level, on the status of women academics. The remaining two interviews, which were conducted with the Vice Presidents for Academic Affairs at two distinct universities (hereafter VP1 and VP2), were aimed at exploring the role of policy-making, at the institutional level, in either facilitating or hindering the career advancement of women academics. Table 3 provides information about these policy-makers.

Interpretative phenomenology was adopted in this study to enable the researchers to give voice to the participants and understand the phenomenon through the narrative accounts of their own actions as well as those of others given by the women themselves (Smith et al. 2009). The interviews were carried out in two phases, the first in July 2016 and the second between March and June 2018, with some women being interviewed more than once. Each commenced by asking the interviewee to recount some of her experiences at the university where she was working, underlining the obstacles that had hindered her career advancement, as well as any aspects that had facilitated it. Throughout these loosely structured interviews, the researchers were keen on exploring a number of issues pertinent to both mothers and non-mothers: the effect of motherhood/non-motherhood on career advancement; children and the household; gendered choices in the household; gendered expectations within the academic institution; career and family-formation choices; and issues related to identity, motherhood, and career. Each interview lasted between one and a half and two hours and was tape-recorded after obtaining each participant’s consent. One week before each interview, the participants had been given a document describing the study, its purpose, and the main themes to be covered during the interviews, besides informing them that their participation was optional and that they could withdraw at any stage. In writing up the findings, to protect the personal identities of participants, only general information at the level of the entire sample was included. Moreover, when making reference to individuals within the text, the names of indigenous Palestinian plants and flowers were used as pseudonyms to protect their anonymity.

Following each phase of the fieldwork, the interviews were transcribed verbatim and translated from Arabic into English. The researchers then carried out a two-stage hermeneutic (interpretive) phenomenological analysis, as per Bhattacherjee’s (2012, p. 106) recommendation. The first stage involved viewing the phenomenon from the subjective perspectives of the participants, while the second involved the researchers’ interpretation of the narrative accounts and of the meanings the participants attached to their stories and experiences. This two-stage hermeneutic analysis enabled the researchers to adequately capture the connection between the micro and macro levels; it enabled them to continually iterate between their interpretations of the participants’ individual narratives (the part) and the context (the whole). By adopting the notions of “narrative infrastructures” (Deuten and Rip 2000) and “meta-conversations” (Robichaud et al. 2004) as interpretive tools embedded within the narratological theoretical lens, the analysis helped illuminate how the women were being influenced by the dominant institutionalized macro-level narratives within both the family and the university, and how the micro-stories they had shared emerged from the reciprocal interplay between fragments of different individual and institutionalized narratives—what Fenton and Langley (2011) called “laminating” (Seidl and Whittington 2014).

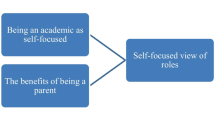

To generate rich thematic descriptions of the participants’ experiences, a blend of hermeneutic circle procedures was followed (Bhattacherje 2012). Structural analysis was conducted, initially by gaining an understanding and appreciation of the essence of each participant’s narrative. This entailed dealing with specific parts of each transcribed interview while, simultaneously, trying to place it within its specific socio-historic context. Then, first- and second-order concepts and themes were generated by identifying the similarities and differences between the individual cases within and across the two participant categories of mothers and non-mothers, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The researchers then endeavored to write individual and reflective accounts of the interplay between their interpretive activities and the participants’ interpretations of their personal experiences. This process facilitated highlighting the common threads connecting the participants’ narratives, but also enabled the emergence of the idiosyncratic nature of each participant’s experience.

Findings and discussion

The effect of “meta-narratives”: patriarchy, religion, and politics

The unusual setting of this study constitutes an important dimension that required the researchers to bear in mind various socio-political and economic aspects while analyzing the participants’ narratives. Although it bears a resemblance to other countries in the Arab MENA region and throughout the world, occupied Palestine represents a peculiar case of 70 years of political struggle that continues to take its toll on Palestinians. Velloso (1996) suggested that Palestinian women are faced with three interweaving layers of structural complexity—signaling the meta-narratives of patriarchy, religion, and politics—that largely shape their opportunities, choices, and entire life situations both at home and at work (Granerud 2012; Sabella and El-Far 2019; Sultan 2016).

In Palestinian society, patriarchy encourages women to invest themselves in traditional roles—i.e., mothers whose natural desire is to have and protect children. According to Tyson (2006), this socially constructed expectation of women concocts a reality in which they put all of their intelligence and power into the accomplishments of their husbands and children. The patriarchal portrayal of women’s intelligence and strength views these features as flaws and as indicators that they are incomplete. In the words of the participants, patriarchy imposes an ideology of female domesticity, which aggravates women’s isolation and diminishes their strength:

…I often find myself unable to compete, especially that my family – including my husband and in-laws – expects me to simultaneously, and independently, manage my domestic and career responsibilities. (Jerusalem Thorn)

…Our society helps men maintain their hierarchical roles both inside and outside the family… We are typically excluded from posts that require us to invest additional time and effort away from home… (Palestine Oak)

These comments reflect the views of those scholars (Al-Dajani and Marlow, 2013; Hattab 2012; Karam and Afiouni 2014) who have written about the cultural values prevailing within Arab countries and of how they tend to continually perpetuate discriminatory patriarchal and masculine norms by delineating the limits of women’s activities and prioritizing their domestic duties. The constraining characteristic of patriarchy is iterated by the MHE: “career women are almost always portrayed as performing traditional roles in, say, education, agriculture and nursing; certainly not as doctors, ministers, or university presidents.” VP1 shared a similar concern: “Palestinian women do not enjoy equal freedoms as men ... it is still problematic, even for liberal families, to urge their daughters to travel or live independently in pursuit of education or employment opportunities.”

As may have been expected, the interviews conveyed how some of the participants had internalized and reproduced conventional gendered expectations, both at home and at work. Crown Daisy commented that “household chores are my natural obligation” and that “I learned these ideals after my mother”; Grapevine described her ability to balance the roles of “ideal mother” and “academic woman,” indicating her capability of “caring for my household, profession and myself, all at the same time,” while Thyme remarked that there were three female vice presidents at her university, thereby unveiling her perception of the exceptionality of women attaining positions of leadership.

Although the patriarchal phenomenon is not exclusive to conservative Arab societies, the immense pressures associated with it are exacerbated in them by virtue of certain religious principles and norms that reinforce women’s subordination. Some scholars (Hattab 2012; Jamali et al. 2005; Kazemi 2000) have suggested that the confluence of “patriarchy” and “Islam” defines women’s lived realities and constrains their participation in the social, economic, and political arenas. For instance, in contrast to the dominant Islamic discourse on the role played by religion in ancient times in liberating Arab women and in explicitly granting them basic rights, Kazemi (2000) and Hattab (2012) stressed how Islamic teachings effectively support women’s subordination and unequal treatment in some of the domains in which they should allegedly be offered rights of entry, like inheriting. Some participants also highlighted the evenly antagonistic role played by religious leaders “who contribute to fortifying female domesticity and furthering the patriarchal agenda” (MHE), and the ways in which “clerical interpretations of religious teachings serve to justify and even legitimize female subjugation” (Star-of-Bethlehem).

Notwithstanding the combined effect of patriarchy and religion, the features that make the Palestinian context rather distinctive derive primarily from the ongoing Israeli occupation, which impinges upon every aspect of a Palestinian’s everyday life. As argued by Rought-Brooks et al. (2010), the enduring occupation has discernibly obstructed all efforts aimed at improving the social and legal structures affecting Palestinian women and their rights. Furthermore, with up to 40% of the male Palestinian population having spent spells of various lengths in Israeli detention camps since the 1967 Arab-Israeli war (Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association 2014), many Palestinian women find themselves obliged to assume the role of main (and sometimes sole) breadwinner while, at the same time, continuing to deal with their typical childcare and housework responsibilities. Nevertheless, the prevailing social and cultural values that generally relate leadership to men continue to be perpetuated in all spheres of life. Here, the MHE states that, “Despite their noteworthy historical contributions to the lives of both the family and the local community, women are still considered not suitable for leadership positions.”

Moreover, burdened by the complexities engendered by the occupation’s policies and practices, Palestinian universities are isolated from global academic networks, which makes the realities of Palestinian academic women even more challenging. Star-of-Bethlehem maintained that “being segregated from the international academic world forces Palestinian universities to depend completely on the limited local market for recruitment,” creating a situation wherein “staff members, men and women alike, have to contend with heavy workloads to compensate for staff shortages.” However, Palestine Oak claimed that this situation, “places women at an especially underprivileged position, given their typically greater domestic responsibilities.” VP2 also affirmed that the effect of the occupation on economic conditions restrains the universities’ ability to invest adequately in supporting academics, and specifically women, whose personal and career development needs may be substantially greater.

Laminating the individual narratives: the effect of motherhood on mothers and non-mothers

The findings substantiate the impeding effect of domestic duties on the career development and advancement of women, particularly of those with childcare responsibilities. For instance, Palestine Oak discussed her obligations towards her family and two daughters as a major factor that had repeatedly disrupted her career and had led to postponing her pursuit of a doctoral degree. Thyme and Jerusalem Thorn also asserted that their familial duties—especially those linked to them both having very young children—precluded them from pursuing doctoral studies. Being somewhat more frustrated, Terebinth emphasized that she had been “often compelled to reject high-ranking posts to evade the double burden of family and leadership.” All these reflections were further evidenced by one policy-maker, whose comment illustrates how women may sometimes internalize and perpetuate the traditional gender role expectations that hold them primarily responsible for the burden of care within their families:

Domestic responsibilities prevent women from accepting development opportunities … and, in the few instances when we forcibly urged competent women to continue their doctoral studies abroad, some have decided to leave the university and stay true to their natural caring role instead. (VP2)

Some markedly rebellious participants presented a fairly different position, expressing their rejection of the prevailing patriarchal and masculine norms that discriminate against women. Lovegrass, the mother of an only child, affirmed that she had a “warrior-like character” and did “not accept any kind of unfair treatment.” Throughout her interview, Lovegrass was keen on making various remarks that implied an unconventional view of the gender roles within the household, steadfastly affirming that “men should assume an equal share for domestic responsibilities.” Blepharis, who had served as Vice President for Community Outreach and, at the time of her interview, was a professor in a male-dominated subject area, also underlined the supportive role played by her spouse, who was acculturated to life in more liberal societies, and thus enabled her to combine two challenging and thriving careers with a healthy family life:

My husband’s willingness to assume full responsibility towards our four children enabled me to combine two extremely demanding professions … a pediatrician and a university professor.

The accounts of other participants underlined the empowering role of the immediate family. Grapevine stressed that, although she had been born and raised within a traditional religious community, her family had been a major source of encouragement: “my father taught me about life, determination and hard work … my older brother and sister offered me financial support and urged me to continue my [education] abroad.” In this respect, Grapevine’s comment appears to somewhat contradict the literature that views “family” as a force that prevents women from advancing their careers and shaping their lives as they themselves envision, thus validating the findings of those prior studies that stress the importance of family support (Dickson 2020; Naz et al. 2017). Thyme highlighted the influence of her progressive family on her educational attainments, while Crown Daisy affirmed: “it would not have been possible for me to succeed without the help of my family members, especially husband and mother.”

While acknowledging the great pressures imposed upon academic women with childcare responsibilities, the findings provide evidence that childfree women also experience the domestic sphere as a “greedy institution” (Acker 1980; Bagilhole 1993; Leonard and Malina 1994; Ramsay and Letherby 2006), and that this has detrimental consequences for their careers as academics. Although domestic responsibilities are generally associated with marriage and children (Leonard and Malina 1994; Munn-Giddings 1998), some single and childfree participants identified their consuming familial duties as the most significant factor hindering their career progression, with most of them being socially obligated to assume the role of principal caregiver for their parents or other family members. Sage, who lived with her elderly mother and aunt and was fully responsible for caring for both of them, stated: “my heavy responsibility prevents me from travelling to pursue higher education, or even considering any career-related plans and aspirations.” Sumac also described how her mother had constantly tried to push her to give up her doctoral studies abroad saying, “Enough [Sumac]! Your father is ill and I’m getting old…it’s time for you to return home to take care of us.” Being single and childfree, Sumac deplored that the prevailing social values and expectations held her entirely accountable for every detail related to her aging parents, while her two siblings, being married, were excused for having their own families and children to care for. Furthermore, Sumac recounted how, as her job was in a city other than her own, her parents constantly pressured to leave her work at the university to be more readily available whenever they needed her help during the day:

Belonging to a Muslim, conservative family and community, I’m required to live with my family for as long as I remain unmarried. … My parents incessantly push me to leave my work to avoid the risks of passing through Israeli-occupation checkpoints, as they claim; but what I feel they really mean is that they want me to stay around all the time … because I’m single and childfree, unlike my two married siblings.

Despite the widely held assumption that reserves mothering and domestic duties exclusively for women with childcare duties, the above comments show that it is not necessarily so, and that women “without” children are also subject to family-related “burdens” that curtail their career advancement. Aligned with Ramsay and Letherby’s (2006) assertion that not having children does not liberate women from caring responsibilities outside the university, the narratives of most childfree participants suggest that their arduous obligations towards their parents and other family members restrain their ability to work from home (e.g., Sage, Sumac, Terebinth) and consequently inhibit their research and scholarly productivity (e.g., Judean Iris, Sage). Hence, returning to Probert’s (2005) observation concerning mothers’ inability to rely on “the power of absence from home for work” (p. 69), the experiences of non-mothers seem to be similarly affected by the socially constructed ideologies and expectations of motherhood, in that, in their daily lives, they too are expected to take on mothering duties and to be responsible for the burden of care within their families—all of which limits their ability to work from home. Apart from highlighting how familial obligations evenly affect the experiences of non-mothers and mothers, the above line of thought accentuates the need to expand the existing conceptualization of domestic duties to include an array of caring responsibilities toward various family members—including spouses, parents, grandparents, siblings, and even the children of siblings—instead of upholding and sustaining the narrow understanding that limits domestic duties to the responsibility of providing care to one’s own children.

Quite predictably, the family- and societal-level expectations and assumptions that shape the experiences of women in Palestine are found to influence how non-mothers and mothers are treated in the academic context. Reflecting Munn-Giddings’ (1998) argument that women with childcare duties are the most marginalized in academia, almost all of the participants discussed how the masculine culture prevailing in Palestinian universities specifically placed academic mothers at a disadvantage (Palestine Oak, Crown Daisy). Nonetheless, several participants emphasized some gendered expectations and practices that similarly place non-mothers at a disadvantage. Jerusalem Thorn, a mother of two who had served as the head of an academic department for three consecutive years, described the underprivileged positions held by unmarried and childfree women in her department, testifying that “they are frequently assigned more work than mothers because they are presumed to have less domestic obligations.” Additionally, consistent with Probert (2005) and Ramsay and Letherby (2006), Jerusalem Thorn made it clear that non-mothers too are regarded as “caregivers” just because they are women and are thus expected to extend their mothering capacity to their students, co-workers, and the greedy university.

Other non-mothers further corroborated Jerusalem Thorn’s view. Sumac indicated: “Sometimes, I end up undertaking the tasks that mothers are unable to do because work should be completed anyway.” And Sage commented: “nearly all of my colleagues, women and men alike, expect me to be available all the time since I have no spouse or children.” To top it all off, Terebinth, a married childfree woman who was also annoyed by the prejudiced attitudes and expectations of her workmates, declared: “It’s true that I have no children, but I have plenty of obligations towards my home, husband and relatives.”

Furthermore, Sumac complained: “Everybody considers my excuses to be less important than those of mothers, deeming that I have fewer duties outside the university.” And Barbary Nut indicated: “Mothers in my department are more readily excused for leaving work early, or for frequently missing deadlines.” These individual accounts offer valuable insights that are fairly analogous to what Ramsay and Letherby (2006) empirically showed with respect to the situation of childfree women within the gendered university, suggesting that they are as marginalized as mothers. In this sense, as women “without” children are often perceived as having no domestic duties outside the institution, they are expected to give their all to work and to put in the time and energy that women with childcare duties cannot. Moreover, while, in their early work, Leonard and Malina (1994) argued that the lives of academic mothers are characterized by silence and exclusion, our participants’ comments suggest that non-mothers also experience silence and exclusion within the university, especially in that their unique and demanding domestic responsibilities are seldom considered or acknowledged.

Who decides for women? Career and family-formation choices

The data demonstrate that the pursuit of an academic career considerably shapes the ways in which women manage their life choices and make decisions related to marriage, family-formation, and childbearing age and timing. Embedded within the narratives of most of the participants is a manifestation of the ideological conflict—identified by Leonard and Malina (1994)—between the roles of the “altruistic mother” and the “career woman” (Romanin and Over 1993; Wolf-Wendel and Ward 2006), which brings to the fore the demands of both the family and the university as “greedy institutions” (Acker 1980; Ramsay and Letherby 2006). For instance, Christ’s Thorn, a young and remarkably enthusiastic female academic, affirmed her preference for voluntarily postponing marriage and motherhood (Ivancheva et al. 2019) until well-established on her career path, thus reproducing the narrative that “being a successful academic requires an all-consuming dedication to research and publishing,” which is often in competition with the great burdens typically imposed upon women with childcare responsibilities (Raddon 2002; Wolf-Wendel and Ward 2006). This resonates with Romanin and Over’s (1993) argument regarding the ways by which women deal with family and work commitments. While we acknowledge that both men and women are expected to sacrifice their family and personal lives to their academic careers, women are more likely than men to remain single and childfree to facilitate their career progression and avoid the pressures of multiple roles (Ward and Wolf-Wendel 2012). Star-of-Bethlehem and Lovegrass expressed similar views on the relation between career progression and marriage; both of them underlined that their late marriage had played a key role in facilitating their career progression. Here, it is also worth recalling Dickson’s (2020) and Naz et al.’s (2017) arguments regarding men and their parental and spousal support for their daughters and wives and how this could assist women academics in keeping a balance between the demands of family and career.

Furthermore, all the mother participants, with the exception of Blepharis, indicated that they had made the active choice to limit their families to one or two children, claiming that the demanding nature of the academic profession necessitated controlling their family size—see Romanin and Over’s (1993) discussion on the number of offspring and women’s experiences of career interruptions. Although some participants noted that such a choice had assisted them in realizing their career aspirations and achieving a prosperous family life, others stated that it had created significant tensions within their families, as having only one or two children is considered to be socially undesirable in Palestine. Jerusalem Thorn declared that her husband’s family ceaselessly demanded of her to have more children. Her husband did not exert any such pressure upon her because he was aware that having more children would require him to assume a greater share of housework and childcare responsibilities, and he was simply neither ready nor willing to do so. Grapevine recalled her mother’s unaccommodating attitude: “she was disappointed … she wanted me to have more kids … she used to continuously make me feel guilty.”

Several mother participants stated that working in academia seemed to have positively influenced the upbringing and education of their children. Grapevine and Thyme maintained that their careers had helped them bring up ambitious and autonomous children. Star-of-Bethlehem opined: “my inspiring journey has motivated my daughter to persevere and pursue higher education.” Lovegrass affirmed: “my experience assisted me in nurturing an open-minded son.”

Identity and career

In discussing the issues of personal identity at the nexus of motherhood and career, several participants openly identified some distinctions between the positions of mothers and non-mothers, which fares well with the views of Ramsay and Letherby (2006). For instance, reflecting upon her experience of being involuntarily childfree, Sumac described the constant feelings of inadequacy stemming from her internalization of those social norms and expectations that view women “without” children as unfulfilled and deficient, and that expected her, along other single and childfree women, to shoulder the burden of caring for parents and other family members. In an aggrieved tone of voice, she commented: “Non-mothers, like me, are regarded as incomplete women. Honestly, irrespective of my academic and professional achievements, sometimes I feel something is still missing in my life.”

She further elaborated:

Undeniably, mothers are required to sacrifice, to be dedicated, and to put so much time and effort in bringing up their children. Nevertheless, becoming responsible is a decision that mothers willfully make … they choose to be in that situation. … It is not reasonable to compare my situation to that of mothers. I’m morally obligated to care for my parents, while mothers find happiness and emotional fulfillment in caring for their own families and children.

Similarly, Barbary Nut spoke about her exasperation and went on to problematize the notion that non-mothers do not have any caring relationships towards individuals inside or outside the academic institution—i.e., towards the children of siblings and other relatives, as well as towards students: “Sometimes, I treat my siblings’ and other relatives’ children as my own … I tend to practice motherhood on them, and on my students as well.”

Nevertheless, some differences also emerged in how mothers and non-mothers define themselves and establish their self-identities (Ramsay and Letherby 2006). Perhaps as was to be expected, most of the mothers, either directly or indirectly, indicated that their families were the top priority in their lives, and that their mothering role was the defining feature of their identities as women (Jerusalem Thorn, Grapevine, Crown Daisy, and Palestine Oak). Jerusalem Thorn, for example, affirmed with confidence: “My family and children will always remain the center of my attention, though I am profoundly passionate about my career.” Similarly, seeming very keen on articulating her love for and dedication to her family, Grapevine commented: “My success and self-worth are greatly shaped by, and defined through, my ability to balance domestic and professional obligations.” Some mother participants, however, took a much more complex stance in describing their identities: “I’m an academic and my work is a direct representation of myself. This is not in contradiction with my being a mother, a wife, or anything else. All the different things I do constitute who I am.” (Lovegrass)

Contrastingly, the academic careers of most non-mother participants seemed to be more deeply embedded within their personal identities. Terebinth asserted: “Academia is a major component of my character.”; Sumac also considered her career to be an extension of her identity and expressed this by indicating that she devoted most of her time to research and university work, while Sage mentioned: “I cannot even imagine myself not being an academic,” and “Academia works for me like nothing else.”

Conclusion

While acknowledging the distinctiveness of each woman academic’s individual experiences, this study has revealed some notable commonalities and connections among them, which validates Ramsay and Letherby’s (2006) observation that, although motherhood is a key difference between women, both mothers and non-mothers are influenced by the socially constructed notion of motherhood and are therefore placed at a considerable disadvantage, both within their families and the university. Concurring with the proponents of the domestic responsibilities model (Romanin and Over 1993; Ward and Wolf-Wendel 2012; Wilton and Ross 2017), the family is found to be one of the most significant factors inhibiting mothers’ career progressions in academia, especially in regard to the fact that, in occupied Palestine, women are typically expected to shoulder most domestic obligations (PCBS 2015). Clearly, the model has turned out to be equally instrumental in explaining the underprivileged position of single and childfree women, who are also found to have domestic obligations in spite of their distinctive commitments and lifestyles. Moreover, corroborating Ramsay and Letherby’s (2006) view, women “without” children are also traditionally perceived as “caregivers” just because they are women and are accordingly expected to extend their mothering capacity to those around them—be these individuals’ children, parents, siblings, or even students. As such, they are generally required to devote more time to tasks that involve greater interaction with students, like academic orientation, and to carry out the work that women with children are deemed to be unable to do.

Consequently, with respect to the domestic responsibilities model, the arguments and inferences presented within this paper not only render the existing conceptualization of domestic responsibilities inadequate to fully understand and explicate the disadvantaged position of academic women, but also turn our attention to the need to expand the model’s narrow focus in order to include the distinctive family-related duties of non-mothers on the one hand, and the innumerable caring responsibilities that can be imposed upon women in general on the other. This becomes all the more relevant in a collectivistic, Muslim society like Palestine, where religious norms and principles stress the significance of being dutiful to one’s parents and elderly relatives, and where one’s family commitments extend beyond attending to the typical needs of the immediate family to those of the extended one—i.e., grandparents, aunts, uncles, and other relatives. Such constraining realities are often exacerbated by the fact that the traditional Palestinian home may, in some instances, accommodate up to three generations, and that children are normally expected to reside with their families for as long as they remain unmarried.

Moreover, while the existing evidence stresses the deterring effect of the family or household (Raddon 2002; Ramsay and Letherby 2006; Ward and Wolf-Wendel 2012), the findings lend credence to the previous evidence showing that immediate family members (e.g., parents, siblings, spouses) may sometimes play an active role in supporting women’s educational and professional advancement (Dickson 2020; Naz et al. 2017). Additionally, reflecting the inherent conflict presumed to exist between the roles of the “altruistic mother” and of the “career woman” (Leonard and Malina 1994), the pursuit of an academic career is found to have a considerable influence on how individual women manage their life choices, define themselves, and establish their self-identities.

In adopting “narratology” as a theoretical lens, this study sheds important light on the link between the micro and macro levels in understanding the disadvantaged position of Palestinian academic mothers and non-mothers, thereby enabling protection against what Seidl and Whittington (2014) termed “micro-isolationism”—i.e., the inclination to explicate local actions in their own terms and to disregard the influence of contextual variables, or the larger surrounding phenomena that give rise to such actions. Not only does this enable capturing more fully the social embeddedness of micro-level activities (Seidl and Whittington 2014) but also to better comprehend how the women’s narratives reflect their own understandings of what they are doing, and of what is being done to them—both inside and outside the family and academia. Hence, with its emphasis on “narrative infrastructures” and “meta-conversations,” narratology is considered apposite for grasping how actors create narratives as they interact and go about their everyday working lives, and how their individual narrative understandings may eventually contribute to making up the world they seek to describe.

Although this study adds to the very limited body of literature that explores the narratives of women academics in Arab Middle Eastern countries generally, and in the Palestinian context specifically, future research may deepen the current understanding in numerous ways. First, instead of attributing gender inequality at universities to unfair institutional practices, it would be essential to also account for the effect of the household on women’s working lives. This involves going beyond considering the requirements of maternity leave and early childhood, to include those associated with older offspring, the influence of the vicissitudes of family life, like divorce, separation, aging, and the menopause upon women’s professional development. Second, given that all of the women academics participating in this research were drawn from higher education institutions situated in the West Bank of occupied Palestine, it would be worth investigating whether the narratives of those working at universities in the Gaza Strip are different, especially in light of the fairly distinctive socio-economic and political realities that characterize the Strip as a result of over a decade of military siege. Third, although the main aim of the current study was to examine the role played by “motherhood” in the experiences of Palestinian academic mothers and non-mothers while considering the influence of the interweaving contextual forces defining the Palestinian context, it would have been worth to also account for any heterogeneity and differences found among the research participants. Accordingly, future researchers would do well to conduct intersectional analyses to examine how social categories of difference (e.g., class and age) interact to shape women’s distinctive experiences in academia. Finally, although this lies outside the scope of this paper, a comprehensive study addressing the dearth of statistics on female representation in academia across the Arab MENA region would prove invaluable for future research.

References

Acker, S. (1980). Women, the other academics. In Equal Opportunities Commission, Equal Opportunities in Higher Education. Report of an EOC/Society for Research in Higher Education Conference at Manchester Polytechnic, Manchester EOC.

Acker, S., & Armenti, C. (2004). Sleepless in academia. Gender and Education, 16(1), 3–24.

Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association. (2014). Palestinian political prisoners in Israeli prisons. Retrieved from: http://www.addameer.org/files/Palestinian%20Political%20Prisoners%20in%20Israeli%20Prisons%20(General%20Briefing%20January%202014).pdf. Accessed 10 January 2019.

Aghabekian, V. (2019). Demanding a bigger role: Palestinian women in politics and decision making. Medicine, Conflict, and Survival, 35(3), 241–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2019.1679948.

Al-Dajani, H., & Marlow, S. (2013). Empowerment and entrepreneurship: a theoretical framework. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 19(5), 503–524. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-10-2011-0138.

Aruri, A. (2018). Economic independence: a prerequisite for the social and political participation of Palestinian women. This Week in Palestine, 239(March), 30–32.

Bagilhole, B. (1993). Survivors in a male preserve: a study of British women academics’ experiences and perceptions of discrimination in a UK university. Higher Education, 26(4), 431–447.

Bailyn, L. (2003). Academic careers and gender equity: lessons learned from MIT. Gender, Work and Organization, 10(2), 137–153.

Bhana, D., & Pillay, V. (2013). How women in higher education negotiate work and home: a study of selected women at a university in South Africa. JHEA/RESA, 10(2), 81–94.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: principles, methods, and practices (2nd ed.). Florida, USA: University of South Florida.

Boje, D. M. (2001). Narrative methods for organizational and communication research. London: SAGE Publications.

Britton, D. M. (2017). Beyond the chilly climate: the salience of gender in women’s academic careers. Gender & Society, 31(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243216681494.

Deuten, J. J., & Rip, A. (2000). Narrative infrastructure in product creation processes. Organization, 7(1), 69–93.

Dickson, M. (2020). “He’s not good at sensing that look that says, I’m drowning here!”Academic mothers’ perceptions of spousal support. Marriage & Family Review, 56(3), 241–263.

Eliou, M. (1988). Women in the academic profession: evolution or stagnation? Higher Education, 17(5), 505–524.

Fakher, K. N. (2018). Cultural values and marital satisfaction: do collectivism and gender role orientation affect marital satisfaction among Palestinian couples? International Journal of Indian Psychology, 6(2), 74–97.

Fenton, C., & Langley, A. (2011). Strategy as practice and the narrative turn. Organization Studies, 32(9), 1171–1196.

Granerud, J. H. (2012). Belonging to Palestine: a study of the means and measures of Palestinian women’s belonging to their state and nation. Master thesis, Global Refugee Studies, Aalborg University, Aalborg.

Grummell, B., Devine, D., & Lynch, K. (2009). The care-less manager: gender, care and new managerialism in higher education. Gender and Education, 21(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250802392273.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82.

Hattab, H. (2012). Towards understanding female entrepreneurship in Middle Eastern and North African countries: a cross country comparison of female entrepreneurship. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 5(3), 171–186.

Hermanowicz, J. (2009). Lives in science: how institutions affect academic careers. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Huopalainen, A. S., & Satama, S. T. (2019). Mothers and researchers in the making: negotiating ‘new’ motherhood within the ‘new’ academia. Human Relations, 72(1), 98–121.

Huppatz, K., Sang, K., & Napier, J. (2018). If you put pressure on yourself to produce then that’s your responsibility’: mothers’ experiences of maternity leave and flexible work in the neoliberal university. Gender, Work and Organization, 26(6), 772–788.

Huzzard, T., Benner, M., & Karreman, D. (Eds.). (2017). The corporatization of the business school: Minerva meets the market. New York, USA: Routledge.

Ivancheva, M., Lynch, K., & Keating, K. (2019). Precarity, gender and care in the neoliberal academy. Gender, Work and Organization, 26(4), 448–462.

Jamali, D., Sidani, Y., & Safieddine, A. (2005). Constraints facing working women in Lebanon: an insider view. Women in Management Review, 20(8), 581–594. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420510635213.

James, M. K. (2013). Women and the Intifadas: the evolution of Palestinian women’s organisations. Strife Journal, 1(2013), 18–22.

Johnson, P., & Kuttab, E. (2001). Where have all the women (and men) gone? Reflections on gender and the second Palestinian Intifada. Feminist Review, 69(1), 21–43.

Kallio, K.-M., Kallio, T., Tienari, J., & Hyvönen, T. (2016). Ethos at stake: performance management and academic work in universities. Human Relations, 69(3), 685–709.

Karam, C. M., & Afiouni, F. (2014). Localizing women’s experiences in academia: multilevel factors at play in the Arab Middle East and North Africa. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(4), 500–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.792857.

Kazemi, F. (2000). Gender, Islam, and politics. Social Research, 67(2), 453–474.

KELA (2017). Maternity, paternity, and parental allowances. Retrieved from: www.kela.fi/web/en/parental-allowances. Accessed 18 March 2020.

Kenny, J. (2017). Academic work and performativity. Higher Education, 74(5), 897–913.

Leonard, D., & Malina, D. (1994). Caught between two worlds: mothers as academics. In S. Davies, C. Lubelska, & J. Quinn (Eds.), Changing the subject: women in higher education (pp. 29–41). London: Taylor and Francis.

Lovejoy, M., & Stone, P. (2012). Opting back in: the influence of time at home on professional women’s career redirection after opting out. Gender, Work and Organization, 19(6), 631–653.

Magadley, W. (2019). Moonlighting in academia: a study of gender differences in work-family conflict among academics. Community, Work & Family. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2019.1678458.

Mahabeer, P., Nzimande, N., & Shoba, M. (2018). Academics of colour: experiences of emerging Black women academics in curriculum studies at a university in South Africa. Agenda, 32(2), 28–42.

Ministry of Education & Higher Education. (2018). Statistical yearbook 2017/2018. Palestine: Ramallah.

Mirick, R. G., & Wladkowski, S. P. (2018). Pregnancy, motherhood, and academic career goals: doctoral students’ perspectives. Affilia, 33(2), 253–269.

Munn-Giddings, C. (1998). Mixing motherhood and academia–a lethal cocktail. In D. Malina & S. Maslin-Prothero (Eds.), Surviving the academy: feminist perspectives (pp. 56–68). London: Routledge.

Naz, S., Fazal, S., & Khan, M. I. (2017). Perceptions of women academics regarding work-life balance: a Pakistan case. Management in Education, 31(2), 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020617696633.

Nikunen, M. (2012). Changing university work, freedom, flexibility and family. Studies in Higher Education, 37(3), 1–7.

Ollilainen, M. (2019). Academic mothers as ideal workers in the USA and Finland. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 38(4), 417–429. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-02-2018-0027.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2007). Sampling design in qualitative research: making the sampling process more public. The Qualitative Report, 12(2), 238–254.

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. (2015). Women and men in Palestine: issues and statistics, 2015. Palestine: Ramallah Retrieved from: http://www.Pcbs.gov.ps/Downloads/book2171.pdf.

Palestinian Ministry of Education & Higher Education (MoEHE). (2017). Higher Education Statistical Yearbook 2016-2017. Available at: http://www.mohe.pna.ps/Portals/0/MOHEResources/Statistics/dalil%202017final.pdf?ver=EGccZYu_MV5gjKT2aFBQxg%3d%3d. Accessed 20 June 2019.

Palestinian Ministry of Education & Higher Education (MoEHE). (2018). Higher Education Statistical Yearbook 2017/2018. Available at: http://www.mohe.pna.ps/Portals/0/MOHEResources/Docs/Statistics/dalil%202018.pdf?ver=6hxPsMB7FHy_c6T0yuB8gw%3d%3d. Accessed 16 March 2020.

Probert, B. (2005). ‘I just couldn’t fit it in’: gender and unequal outcomes in academic careers. Gender, Work and Organization, 12 (1), 50-72.

Raddon, A. (2002). Mothers in the academy: positioned and positioning within discourses of the ‘successful academic’ and the ‘good mother’. Studies in Higher Education, 27(4), 387–403.

Ramsay, K., & Letherby, G. (2006). The experience of academic non-mothers in the gendered university. Gender, Work and Organization, 13(1), 25–44.

Rhoads, R. A., & Gu, D. Y. (2012). A gendered point of view on the challenges of women academics in the People’s Republic of China. Higher Education, 63(6), 733–750.

Richter-Devroe, S. (2005). The Palestinian women’s movement after Oslo. Al-Raida Journal, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.32380/alrj.v0i0.298.

Robichaud, D., Giroux, H., & Taylor, J. (2004). The metaconversation: the recursive property of language as a key to organizing. Academy of Management Review, 29(4), 617–634.

Romanin, S., & Over, R. (1993). Australian academics: career patterns, work roles, and family life-cycle commitments of men and women. Higher Education, 26(4), 411–429.

Rought-Brooks, H., Duaibis, S., & Hussein, S. (2010). Palestinian women: caught in the cross fire between occupation and patriarchy. Feminist Foundations, 22(3), 124–145. https://doi.org/10.1353/ff.2010.0018.

Sabella, A. R., & El-Far, M. T. (2019). Entrepreneuring as an everyday form of resistance. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(6), 1212–1235.

Saunderson, W. (2002). Women, academia and identity: constructions of equal opportunities in the ‘new managerialism’–a case of lipstick on the gorilla. Higher Education Quarterly, 56(4), 376–406.

Scott, J. W. (2019). Palestinian University fights Israeli visa restrictions. Retrieved from: https://www.birzeit.edu/en/blogs/palestinian-university-fights-israeli-visa-restrictions. Accessed 20 March 2020.

Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2009). Research methods for business: a skill building approach. UK: Wiley.

Seidl, D., & Whittington, R. (2014). Enlarging the strategy-as-practice research agenda: towards taller and flatter ontologies. Organization Studies, 35(10), 1407–1421.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method and research. London: Sage Publications.

Sultan, S. S. (2016). Women entrepreneurship working in a conflict region: the case of Palestine. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 12(2-3), 149–156.

Tyson, L. (2006). Critical theory today: a user-friendly guide. New York, United States: Routledge.

UNDP (2015). The 2014 Palestine human development report. Retrieved from: https://www.undp.org/content/dam/papp/docs/Publications/UNDP-papp-research-PHDR2015.pdf. Accessed 22 March 2020.

Velloso, A. (1996). Women, society and education in Palestine. International Review of Education, 42(5), 524–530.

Visweswaran, K. (2015). Palestinian Universities and everyday life under occupation. Retrieved from: https://www.aaup.org/article/palestinian-universities-and-everyday-life-under-occupation#.XoDZtTYdc6g. Accessed 20 March 2020.

Ward, K., & Wolf-Wendel, L. (2012). Academic motherhood: how faculty manage work and family. New Brunswick, USA: Rutgers University Press.

Wilton, S., & Ross, L. (2017). Flexibility, sacrifice and insecurity: a Canadian study assessing the challenges of balancing work and family in academia. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 29(1-2), 66–87.

Wolf-Wendel, L. E., & Ward, K. (2006). Academic life and motherhood: variations by institutional type. Higher Education, 52(3), 487–521.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

El-Far, M.T., Sabella, A.R. & Vershinina, N.A. “Stuck in the middle of what?”: the pursuit of academic careers by mothers and non-mothers in higher education institutions in occupied Palestine. High Educ 81, 685–705 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00568-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00568-5