Abstract

Trisomy 13 and 18 (T 13/18) are rare chromosomal abnormalities associated with high morbidity and mortality. Improved survival rates and increased prevalence of aggressive medical intervention have resulted in families and physicians holding different perspectives regarding the appropriate management of children with T 13/18. Families were invited for open-ended interviews regarding their experiences with the medical care of a child with T 13/18 over the past 5 years. Seven of 33 invited families were surveyed; those who had spent more than 40 days in the hospital were most likely to accept the invitation (OR 8.8, p = 0.02). Grounded theory technique was used to analyze the interviews. This method elicited four key themes regarding family perspectives on children with T 13/18: (1) they are unique and significant, (2) they transform the lives of others, (3) their families can feel overwhelmed and powerless in the medical setting, (4) their families are motivated to “carry the torch” and tell their story. Families also emphasized ways in which Internet support groups can provide both positive and negative perspectives. The ensuing discussion explores the difficulties of parents and physicians in forecasting the impact that T 13/18 will have on families and emphasizes a narrative approach to elicit a map of the things that matter to them. The paper concludes that while over-reliance on dire prognostic data can alienate families, examining the voice, character and plot of patient stories can be a powerful way for physicians to foster shared decision-making with families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Trisomy 13 and 18 (T 13/18) are the most common autosomal trisomies diagnosed in fetuses and infants after trisomy 21, occurring in one of 12,240 births and one of 6670 births respectively (Meyer et al. 2016). Besides severe growth and developmental delays, congenital heart disease and gastrointestinal abnormalities also occur frequently in both of these conditions. For many years, a philosophy of minimal intervention has been the rule for T 13/18, resulting in 1-year survival rates between 0 and 10% (Lakovschek et al. 2011). However, as demonstrated by 1-year survival rates as high as 44% in a cohort of patients in Japan who received cardiac surgery, emerging data has suggested that aggressive management can be effective in some patients (Maeda et al. 2011). Consequently, in some settings such interventions have become more commonplace (Josephsen et al. 2016; Nelson et al. 2012), with 5-year survival rates of 10 and 12% for trisomy 13 and 18 respectively in a recent multi-state study in the United States (Meyer et al. 2016).

Physician opinions on how to manage patients with T 13/18 are varied in light of the evolving outcomes (Kumar 2011; Wilkinson 2010; Donohue et al. 2010). In a survey of families who were members of T 13/18 Internet networks, 63% of families of children with T 13/18 reported having a helpful health-care provider, while half described being told by providers that their child’s life would be meaningless or characterized by suffering (Janvier et al. 2012; Guon et al. 2014). Such variation is demonstrated not only in physician counseling, but also behavior. A survey of 54 neonatologists in 2008 demonstrated that 56% would not consider initiation of resuscitation of a 36-week infant with trisomy 18 and congenital heart disease (McGraw and Perlman 2008). The 44% that expressed willingness to initiate resuscitation described parental preference as their main reason for considering resuscitation.

While physicians are divided on their perspectives towards medical intervention, families increasingly express attitudes of hopefulness and optimism regarding their child’s experiences with T 13/18. In the same Internet survey, 89% of respondents described their child’s life as positive and 99% of them described their child as happy (Janvier et al. 2012). The varied perspectives within the literature demonstrate a contrast in how the survival rate and disability of T 13/18 are interpreted between physicians who might resist resuscitation and what Guon and Janvier characterize as the “child-centered” approach of their parents (Guon et al. 2014).

To further complicate physician guidance, beyond a child’s already uncertain medical future, parents and providers turn out to be surprisingly poor predictors of the emotional implications of a child’s disability (Peters et al. 2014; Halpern and Arnold 2008). Nevertheless, upon the birth of a child with T 13/18, these stakeholders are together tasked to make decisions with profound future implications. Given the limitations in anticipating the future for children with T 13/18, our study sought to interview experienced families to provide accounts of what a parent might expect when caring for a child with T 13/18. This information could improve the ability of medical teams to counsel families about what they might expect in the coming days to years.

Methods

Study Design

We used a predominantly qualitative mixed methods approach, performing and analyzing interviews of families that met our recruitment criteria. The survey questions were drafted by the authors of the study based on analysis of similar assessments of this population (Kosho et al. 2013; Janvier et al. 2012; Guon et al. 2014) and reviewed by a neonatologist and geneticist for clarity and content. The survey consisted of 10 questions asked in a semi-structured open-ended format. The first five questions were focused on parents’ descriptions of their experiences of caring for their child; the latter questions asked parents to suggest ways that they might counsel a friend or family member who had a child with T 13/18. This study was approved by the Saint Louis University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Participant Sampling and Recruitment

A review of the electronic medical records of a quaternary pediatric referral center and its affiliated maternal-fetal hospital in St. Louis, Missouri yielded 33 children with the diagnoses of T 13/18 that were born over a 5 year period between 2011 and 2016. Recruitment letters were mailed to the last known address for the families of each of these children including a copy of the survey and invitation to respond either by phone, in person, or in writing. Families that agreed to be interviewed were reimbursed for their travel expenses and given a $25 gift card. Due to the sensitive nature of the topic, only one letter was sent to each family. If no response was received, this was assumed to imply that the family had declined to participate.

Data Collection

Both authors were present for all of the interviews, which occurred between July 2016 and September 2016 and lasted from 50 to 75 minutes each. All of the interviews were performed in person except for one that was performed by phone. The interviews were digitally recorded, then transcribed verbatim by an independent transcription service. Transcripts were coded to maintain patient confidentiality.

Data Analysis

Qualitative analysis of the interviews was performed using the grounded theory approach. This method involves collecting information from each transcribed interview and creating common categories where data from different interviews can coalesce. Through further analysis of the categories, investigators can construct unifying “theories” or themes that are “grounded” in the original interview data, allowing them to draw conclusions with implications for future practice (Charmaz 2014).

The authors independently analyzed each interview, deriving “initial codes” to describe specific events in each survey; after successive analyses, they created “focused codes” to describe general themes derived from groups of initial codes observed in one or more interviews. During the analysis phase, they met on a biweekly basis to compare coding results and discuss theories drawn from the data, ultimately developing the themes discussed below.

For the quantitative portion of the results, a two-tailed test was performed to assess the difference in the number of hospital days (inpatient only) and clinical encounters (total number of inpatient, outpatient and emergency room visits) between families who chose to participate in the interview and those that did not. Additionally, an odds ratio was reported with one as the denominator to assess the increased likelihood of interview response for those who had spent more time in the hospital. For these tests, an alpha of 0.05 was selected for demonstrating statistical significance.

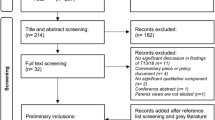

Results

We interviewed a total of seven families out of 33 eligible patients (21%). The families who accepted the interview invitation had significantly more hospital days (73.7 vs. 24.4, p = 0.03) and clinical encounters (22.6 vs. 5.3, p = 0.05) documented in the electronic medical record than those who did not respond (Table 1). Families of children who spent more than 40 days in the hospital were 8.8 times more likely to accept the invitation (OR 8.8, p = 0.02).

Among the interviewed families, three had children who had passed away between the ages of 3 and 16 months; the other four families had living children ranging from 12 to 30 months of age. Families were diverse with respect to race, educational attainment and marital status (Table 2). In addition to the two hospitals whose electronic medical records were used to identify the patients, the patients had also received care at an additional seven hospitals.

Qualitative analysis of the transcribed interviews yielded four themes. First, parents saw their children as significant, having special importance within their communities and faith traditions. As a result, they resisted attempts to reduce their child to a medical diagnosis. Second, they saw their child as having a transformative effect on those around them. However, while the effects were often positive, parents warned that the challenges of their child’s complex disease could also create ruptures in relationships. Third, many parents felt that engaging the medical system brought feelings of powerlessness which alienated them from their child. Finally, parents emerged from these experiences motivated to tell their child’s story, believing that storytelling could be therapeutic for them and helpful for others.

Theme #1: Our Child is Unique and Significant

“She doesn’t live in our world, we live in hers” (#28)

All of the parents interviewed described unique and distinctive qualities for their child. They often characterized their children as energetic and opinionated, using words like “bossy” and “magnetic” (#10), “feisty,” and “proud of herself” (#17), “spunky” and “sassy” (#28), and a “princess warrior” that ran her household (#10).

Some parents saw their child as an autonomous entity with his or her own agency and plan. One family felt encouraged by their doctor telling them that their daughter would “tell her own story” (#12). Another was reassured when a doctor told them that their daughter “doesn’t live in our world, we live in hers” (#28). By giving agency to their vulnerable child and seeing her outlook as potentially hopeful, they were both able to find comfort in their child’s “open future” (Davis 1997), while also feeling relief from the overwhelming burden of the decisions that they were trying to make.

“God, this is your baby, you do what you want” (#3)

Beyond their children’s unique individual traits, most of the parents also saw their children as having a spiritual significance, believing that their child’s ultimate outcome was in the hands of God.

As parents struggled to balance their faith with the challenging realities of their child’s diagnosis, many parents relied on prayer to cope with their limited ability to control their child’s outcome. One mother recalls that she “prayed incessantly, gave it all up to God. I never accepted the norm… I never researched trisomy 18 and any time they would tell me this is what’s going to happen… ‘thanks, but I don’t hear it’” (#10). Likewise, another mother stated that after her newborn daughter was diagnosed, her coping resources consisted of “nothing but prayer” because the “negativity” of what she saw online contrasted with what she “felt in [her] heart; there is nothing but life in her” (#17).

Some parents even described supernatural experiences regarding their child: “I swear [God] spoke to me like I am talking to you now” (#10). One mother spoke of how God guided her after the severe domestic abuse she had experienced prior to her daughter’s birth.

I had a lot of hate in my heart because of what her dad did… but then… [God] spoke to me, he was like, this is not your choice, she is a miracle. It’s for other people to see and kind of learn from her… I remember I cried and I just surrendered. I’m like, well God, this is your baby, you do what you want (#3).

“Pretend like this diagnosis [does] not exist and take care of her like before” (#17)

In contrast to the meaning found in the time they shared with their child, all of the families described discomfort with the ways that the diagnosis of T 13/18 seemed to take an outsized role in the manner in which some medical providers treated their child.

Several parents described feeling that providers were unwilling to provide appropriate medical care once they became aware of the diagnosis. One mother recalled how nurses “quit coming in” to care for her daughter, turning down oxygen saturation alarms on the monitors:

Every time she alarmed with apnea or something, they just got annoyed. So they turned the parameters down… First it was 88, then 86, 84; it was okay for her to sat that low. But it wasn’t okay before the diagnosis (#17).

Other families remembered feeling fatigued by what they perceived as an overemphasis on the negative aspects of their child’s medical condition. Although they ended up being pleased with their hospice experience, one family recalled being jarred by the initial conversations with the hospice team: the nurse that came to perform her first evaluation proceeded to “tell us about all her features that reflect trisomy 18… we did not notice the low-set ears (we did after that); because in our eyes she is beautiful” (#12). Another mother described feeling traumatized by the “genetic counselors and other indignant nurses telling me, well the babies like that don’t make it…they tried to make me feel like there is no hope for [my daughter]” (#3).

“I really was just focused on [my daughter]… I wasn’t concerned about what statistics were” (#10)

As families struggled to balance their optimism against the perceived hopelessness of the medical prognosis, many of them became ambivalent about the value of statistics in helping them understand their child’s story. One mother remarked, “I really was just focused on [my daughter]. I didn’t care about trisomy 18… I wasn’t concerned about what statistics were” (#10). Another commented, “the statistics part… is a whole different outlook than what I’ve got with me today” (#17).

As a result, families felt conflicted when trying to make sense of the medical data. Some families wanted to limit the information that they received. For example, one mother declined to be tested for chromosomal abnormalities despite the prenatal diagnosis of “extensive heart defects” because she didn’t want to know about conditions that couldn’t be addressed anyway. As a result, she didn’t find out about the diagnosis of trisomy 18 until after birth. Looking back, she says that declining testing “was another thing that I would not change; I wouldn’t go back and get the optional testing done because I think that would have made me give up hope” (#28). Others realized the value of medical information, even while acknowledging how difficult it was to receive. While one mother stated that she resisted doctors that “kept statistics on the forefront of the conversation,” the medical data did serve to “keep me grounded… and prepared” (#10). Another couple recalled a detailed conversation that took place with a neonatologist 2 months prior to their daughter’s delivery: “I remember just going home and being completely exhausted and overwhelmed and I don’t even remember what she said.” However, as challenging as the conversation was, the family was glad that it had happened because it gave them the ability to make choices for their daughter: “I am so grateful that… everything… was our choice, as awful as those choices were. But at least I can look back and say we made the choices for our family that were right for our family” (#12).

These families demonstrate contrasts in the way that medical data was construed. For some families, medical statistics and diagnoses served to overwhelm the particularities of their child, replacing the hope they felt in their child with dire prognostication, limiting the possibilities that might be offered to them. However, for other families, medical data served the opposite function, putting their child back into their hands, giving them the ability to choose how their child might receive care.

Theme #2: She Transformed Our Lives

Perhaps the reason that many families were acutely aware of the depersonalizing effects of the T 13/18 diagnosis was because medical statistics contrasted starkly with their experience of the transformative effect of their child on their lives. The published data seemed to suggest that their children’s lives would be short and burdensome. However, the days spent with their children felt much richer. During the interviews, families were eager to reflect on the ways that their child had affected their own lives and those of their children, families and friends. One mother recalled,

The time I had with her is worth every tear, worth every moment of pain I have now. It was so worth it… They can’t say [trisomy 18] is incompatible with life, she lived, she was with us. It was the best 120 days I think we had (#12).

However, while they uniformly felt that their child’s effect on their lives was positive, they also were forthright about the challenges that their illness introduced.

“That’s [my sister] ringing the bells” (#28)

Two themes emerged in the ways that parents talked about the impact of children with T 13/18 on their siblings: personal connection and unexpected maturity. Several families spoke of the intimate bonds that their children formed with their sibling with T 13/18. At times these connections were happy: one mother discussed how the siblings were “so connected” that her daughter with trisomy 18 would “just bubble up with joy when she heard them” (#10). Sometimes these connections brought sadness: one mother, whose family had together experienced the challenges of homelessness and poverty, recalled how her 11 and 16-year-old children “went through the same emotional breakdown as I did” as they struggled to care for a new child with trisomy 18 (#3). Sometimes they brought comfort: 3 months after her infant with trisomy 18 had passed away, one mother remembers the peace she felt when her 2-year-old announced, “that’s [my sister] ringing the bells” as they sat together quietly waiting for the beginning of a church service.

Families also reflected on their children’s resilience and wisdom as a result of sharing their lives with a sibling with T 13/18. One mother spoke of how the roles of bathing and tube feeding their sibling with trisomy 18 had resulted in a daughter who was “mature beyond her years” (#10). Another mother discussed how having a daughter with trisomy 18 helped her teach her children that they can be happy during hard times and can cry “good tears” (#3).

However, parents also remembered ways in which being “just too busy” (#17) caring for a child with T 13/18 negatively affected other children in the family. One mother remembers her 2-year-old asking her “so you don’t want me?” after she returned from yet another 2 hour drive to the NICU (#28).

“Medical things… either pull you a lot closer or they tear you [apart]” (#28)

In addition to the effects on siblings, parents discussed how they were transformed themselves. One mother noted that despite having experience parenting other children, having a daughter with trisomy 18 taught her how to be “completely unselfish,” “to just put everything on the shelf…she was just the priority… we all grew as a result of it, my kids included” (#10). Another mother talked about how she had learned to see the “decathlon” of caring for her daughter as “beautiful,” cherishing even the most mundane experiences: “I enjoy the oxygen tank that’s beeping, it used to get on my nerve (sic), waking me up every 5 s… you got to stay positive!” (#3).

The parents were likewise forthcoming about the practical and emotional challenges they experienced. One family felt that the prenatal diagnosis of trisomy 18 took the joy out of their pregnancy, throwing “the things that you would normally do as a normal pregnant couple totally out of the window” (#12). Similarly, another mother felt that her pregnancy “should have been the most happiest moment, but the whole 9 months I was pretty much tortured … by the voices of the nurses… [telling me] she is going to die” (#3). One mother remembered the frustration of always wondering whether or not holding her daughter might hurt her. At times she would receive contradictory information: “The nurse taking care of her would say, ‘you come in and hold her,’…then the physical therapist was like, ‘she gets cranky when you take her out of there so I would leave her.’” As a result, she didn’t feel like she could “fulfill the role [of the parent] that I wanted to be… she was having enough trouble, I didn’t want to cause more” (#28).

Having a child with T 13/18 added tension to the relationships of all of the parents; however, the couples differed in the ways that they responded to this stress. One mother discussed how, “for some families, there is no possible way that they could alter their lives… to take care of somebody like her” (#17). A second family felt that if it weren’t for their age and experience, “I don’t think that a younger [husband] and younger [wife] would be together… it was very stressful, but we had a strong bond and we kept level heads” (#12). Unfortunately, one mother described how the days during and after the life of her daughter were “the beginning of the end” of her marriage. She discussed how in the context of grief, she and her ex-husband “became exaggerated versions of ourselves;” the stresses of caring for an ill child, she said, “either pull you a lot closer or they tear you [apart]” (#28).

Theme #3: We Needed An Advocate

Families saw their children with T 13/18 as both unique and transformative; however, in the context of receiving medical care, families universally described feeling overwhelmed and powerless, at times due to the uncertainties inherent in their child’s diagnosis, at times due to obstacles that presented themselves in the medical setting.

“There was nobody to be in between me and them” (#17)

Particularly in the early days of the diagnosis, families often found themselves “desperate for answers” (#12) and unsure of how to move forward. One family reflected on the “overwhelming amount of information” that they received from physicians, the Internet and other people, finding it “very conflicting and you are never 100% sure you are making the right choice” (#12). Another mother remembered feeling ill-equipped to advocate for her child while in the hospital; “I didn’t know how to say, ‘make my daughter a full code’… I didn’t know what a DNR meant.” Without being versed in the basic language of the NICU, she “didn’t know the right questions to ask. And there was nobody to be in between me and them, there was nobody” (#17).

“I wouldn’t put her down for hours… because she was finally mine” (#28)

As families searched for answers, many of them felt that the hospital presented barriers to their ability to provide optimal care for their children. One mother remembers a physician telling her “she was taught in medical school not to treat kids like mine” (#18). In another instance, a senior physician stated in a care conference, “if it is my own daughter, I wouldn’t waste the digoxinFootnote 1 on her” (#17). At other times, obstacles were subtle and well intentioned. One mother struggled to recall a fond memory of the 14 weeks she spent with her child in the “sterile” NICU because, “I didn’t feel like she was mine;” “all of my pictures I’m in a hospital gown and no wedding ring… that’s not me.” After her daughter passed away, she finally had a chance to craft the memories that she wanted:

I wanted my picture taken because she wasn’t attached to anything… and then I wouldn’t put her down for some hours… because she was finally mine… because she wasn’t connected and nobody cared what I did (#28).

“You are the one who knows your child better than anybody” (#10)

Many families responded to these barriers by taking increased ownership of their child’s care, at times seeing themselves as protecting their child from the medical team: “I never left her side…you are the biggest advocate and you can’t ever forget that” (#10). They placed a high value on provider relationships characterized by trust, humility, respect, and shared decision-making. They wanted providers that were trustworthy: “I have to believe that you’re telling me the truth about my daughter’s condition… or I will not be able to live with myself” (#12). They wanted “humble” (#4) providers who would acknowledge, “that no one knew [my daughter] better than me and that I knew what her best care was” (#10). They wanted providers to respect them and “treat [my son] just like you would treat your baby” (#4). Finally, they wanted doctors to include them in decisions; one mother recalled how she appreciated an instance where she was invited to give input when her child was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit: “for the first time, here’s a doctor asking me [for my plan]… because I’ve been through this over and over and over… for the past two and a half years” (#17).

Theme #4: I Want to Tell Her Story

Parents refused to allow medical providers to narrow the scope of their child’s narrative to entail their diagnosis alone, rather believing that their child’s story was transformative, important and worthy of sharing broadly, both to impact others and to support themselves.

“Mom, I am tired, you can carry the torch now” (#10)

All of the families expressed a particular interest in supporting other families who had children with T 13/18. One mother described her daughter as a 1-year-old with a desire to “impact so many people,” a “purpose” that her mother perceived her daughter passing to her in her final hours: “Mom, I am tired, you can carry the torch now.” As a response, this mother actively looks for opportunities to help others and is considering writing a book (#10). Another mother continues to share her child’s story via an online blog 2 years after she has passed away as a way to allow her life to impact others:

If there is something that we can say from our experience that will help somebody else, that’s really important because we want her life to have purpose and we want her life to have meaning. And anything that I can do to make sure that that stays forever I’ll do (#12).

Families felt that sharing about their child was “healing” (#10) and “therapeutic” (#28) for themselves as well. One family saw their story as a way of honoring their child’s memory: “it’s really important for us to still get to talk about her…2 years out, nobody really asks about [our daughter] anymore” (#12).

While the families all were interested in supporting other families with T 13/18, they were mixed on the utility of Internet groups as a forum for sharing their story. One family described being inspired by families from around the world who had children with trisomy 13 who were flourishing (#4). Two mothers described a particular online network as “positive” (#17) and even “amazing” (#18). However, these same mothers also both warned of other online resources, describing one online leader as “a crook” (#18) and describing some online T 13/18 groups as “very depressing” and “all about death” (#17). Some parents didn’t utilize online networks because they felt like online interactions distracted them from caring for their child: “I can’t focus on what’s going on in the trisomy 18 world, I have to just focus on [my daughter]” (#10). Another didn’t feel like online support groups fit her personality: “I’m naturally an introvert, the idea of… talking to people I don’t know, it wasn’t really my thing” (#28). A mother who chose hospice for her child described online resources as often being characterized by judgment from parents with surviving children towards those who didn’t choose aggressive interventions; consequently, she felt that the groups didn’t represent parents like her:

What you’re going to see is all the parents that still have living trisomy kids are the ones that are out there saying, do this, do this, do this. It’s the rest of us, the 90%… we basically keep our mouth shut about it because that’s not what our story was (#12).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to help providers and parents bridge differences in the ways that they perceive children with T 13/18 by providing concrete examples of families who have experienced similar challenges. This is particularly important because in the absence of such information, both physicians and patients can be poor predictors of future outcomes.

Research on “affective forecasting” demonstrates that people tend to overestimate the negative emotional impact of a loss; this is known as “impact bias.” Moreover, they also underestimate the quality of life of those living with a disability; this is known as the “disability paradox” (Halpern and Arnold 2008). While these phenomena have not been studied specifically for parents of children with T 13/18, the data implies that families will tend to assume they will have a more negative emotional response to their child’s disease and that their child’s quality of life will be lower than the quality of life they will actually experience in the future.

Clinicians experience similar biases when offering “empathetic forecasting”; that is, attempting to forecast the impact on a patient or family’s life in the future. In certain situations, clinicians will demonstrate a stronger negative bias than a person would for themselves; at times, the bias can be similar or even positive (Peters et al. 2014). Notably, excessive negative forecasting from physicians and nurses is a critique that many families in our study expressed about their children’s prenatal and neonatal courses. Our study was designed to mitigate some of the parent and provider impact bias by examining information from families who would be less likely to be subject to the disability paradox, as they have experienced the care of a child with T 13/18 for themselves.

Narrative Humility

Avoiding impact bias requires providers to practice “narrative humility” (Charon 2007); that is, not allowing medical data to replace the practice of being present and recognizing what is meaningful for a child and their family. Concluding from the published literature that T 13/18 will necessarily lead to an intolerable life may ignore the role of the individual family in defining what a “quality life” might entail for their child.

From the interviews, we learned that families saw themselves as advocates for a special child, searching for healers whom they could trust to listen to them and act on behalf of the child and their family. The families we interviewed viewed their child as a brother or a sister, a son or daughter. They saw their child as having a name, a personality, meaning and purpose. They understood them as being woven into a framework of relationships that included their family, their friends and their God. Perceiving these priorities, the provider should recognize that the “mere functionality” (Bishop 2011) demonstrated by lab results and vital signs is but means to a greater end: the thriving of patients and those communities within which the patient is inextricably embedded.

What does a “good life” look like for a child or a family in the context of neurologic impairment, severe disability and an uncertain future? Differences in such thick understandings of the status of children contribute to the chasm that can exist between physicians and families. Yet, perhaps developing a mutual understanding of the meaning and significance of a specific child residing in a particular community can allow for the possibility of shared values and decisions. This paper suggests that such common ground can be found in the often-overlooked stories that families tell about their children.

The Role of Narrative in the Clinical Encounter

When families were asked why they agreed to participate in this study, they all answered that they believed their child had a story that still needed to be told, despite having spent an average of 74 days each in the hospital. This narrative impulse seemed to be a response to their feelings of powerlessness as they struggled to grasp their child’s diagnosis. They described feeling at odds with the medical staff, often not understanding what they were being told. For some, seeking answers online only compounded the torrent of competing information. As a result, despite weeks and months together at the bedside, families felt that there were things that their doctor needed to know that had not yet been heard.

In her article “How Do Patients Know?” Rebecca Kukla compares the role of patients’ stories in medical decision-making with the dominant model of the physician-patient relationship, where doctors provide the “facts,” and patients apply their “values” to those facts (Kukla 2007). Kukla suggests that this model does not describe the clinical encounter quite so neatly as it may appear. For one thing, particularly with regards to rare and complex disorders such as T 13/18, the expectation for anyone but the most specialized doctor to have all of the relevant facts is unrealistic. In fact, at times a patient with a rare disease may actually know more than their doctor about recent developments within the narrow scope of their own illness. Secondly, in view of the disability paradox, the presumption that patients have a precise view of their own values as they apply to the care of their child in the future is also likely naïve.

Beyond the limitations of the dominant model, Kukla suggests further reasons why a physician might play an important moral role in medical decision-making. First, there is no value-neutral form of medicine. When exploring questions about suffering, prolonging life or the effects of illness and healing on a family, medicine routinely requires physicians to exercise values, often requiring them to make judgments of what means might be permissible to meet acceptable and achievable ends. Second, in some situations, clinicians may be in a better position to provide moral discernment due to their experience in dealing with similar scenarios in the past, while a patient or family may be confronting the questions for the first time.

As values can thus fall within contested territory between families and doctors, Kukla suggests a way beyond the debates between medical facts (which we have observed that many patients view with ambivalence) and values. She suggests that storytelling is a particular way that people are able to share valuable information beyond what a clinician might be able to glean from their own experience or observations at the bedside. Storytelling, she says, gives

An understanding of the real practical and emotional impact of living with a particular disability… such narrative and emotional knowledge is often crucial to high quality practical deliberation and decision-making. This is a form of expertise that cannot be neatly categorized as either ‘factual’ knowledge or knowledge of ‘values,’ but it is certainly a kind of medical knowledge that is highly relevant for patients (Kukla 2007).

The lack of important shared knowledge that can only be derived from stories may explain why parents and providers so frequently come to different conclusions even though they may both be aware of the same data and invested in the good of the same patient.

Learning to gather such “narrative and emotional knowledge” is a crucial skill for physicians caring for children with T 13/18. Physicians are experts at gathering and evaluating medical information and then providing it to patients and their families. As a result, they can be tempted to feel that every situation can be addressed by either obtaining or furnishing more data; similarly, they can feel that that objective knowledge alone should be enough to determine the proper medical decision. However, they should also be aware of the inherent limitations of clinical data. In a complex case, eventually, physicians may come to a place where they have already deployed all of the actionable information; it is then time to hand the baton to the patient and their family to tell the stories necessary to interpret the data.

A Narrative Approach

Although a physician may be able to skillfully describe the clinical factors that inform decision-making, these bare facts may provide little comfort to a family and provider struggling with a shared decision. Often all available options entail considerable risk. Given their limited ability to predict the future, how can families and providers possibly choose where to go from there?

In her article “Narrative Ethics,” Martha Montello suggests that close examination of discrete elements of a family’s story may enable a provider to discern the values that matter most to them. As occurs in a good work of literature, she suggests, crafting a satisfying resolution will require close attention to the narrative’s voice, character and plot. These components can reveal the depth and complexity of a family’s moral world, contributing vital perspective to the impossible decisions that families and providers are tasked to make (Montello 2014).

With regards to voice, a doctor or nurse may be tasked with navigating the overlapping and sometimes conflicting stories that different stakeholders can tell. Whose priorities are being expressed—the mother, the father, the grandparent, the pastor? Are there voices that are missing? The provider may choose to question family members directly or even individually to ensure that the quiet, but crucial, voices are heard.

Additionally, it is important to acknowledge the ways that the emergence of social media has brought powerful and potentially competing voices into clinical encounters (Powell et al. 2011; Moorhead et al. 2013). These voices have the potential to help a family forge a path forward, such as the family we interviewed that gained hope for their own child from interactions with thriving families of children with T 13. However, as noted in our interviews, online voices can also be demoralizing, potentially influencing decisions being made at the bedside through judgment and shame. In acknowledging the role of the Internet, providers may want to warn families of ways in which online opinions can subtly replace the voices of those who are most invested in the child’s care. They may remind the family that their child is unique and special, their story unable to be fully captured in a blog post or news feed. Indeed, the family and medical providers who have cared for a child at the bedside will be in a much better position to speak on behalf of the child as compared to opinions derived from the Internet.

With regards to character, the provider must determine: “Whose story is this?” A story will not be complete without the contributions of both major and minor characters. However, the role of the provider is to ensure that the priorities of secondary stakeholders do not obscure what matters most for the patient and their family. At times, the “hero” of the story might initially appear to be the loudest voice in the room or the physician who is making medical recommendations. However, providers should examine themselves and others to determine whether personal beliefs about parenting, illness, medicine and disability are taking on an excessive role in a story in which they are not at the center. For example, providers might ask themselves, “Are we rushing the family to make a decision because it is best for the child or because the practice of waiting rather than ‘doing’ is contrary to the ethos of modern medicine?” Or, when working to resolve differences involving family members and/or providers, a physician might ask, “What can we do together to ensure a good life for your child?” in order to steer conversation away from minor characters and back to the patient.

With regards to plot, most families of a child with T 13/18 are in the midst of an unanticipated twist in their story. For many of them, a hopeful future may seem suddenly unclear, their fortunes suddenly reversed. The role of the physician can be to help them find a happy, or at least meaningful, way forward. This conversation may begin with a narrative question such as, “What would you see as a good next chapter to this story?” Rather than being directive, this approach asks families to reflect on their own priorities and how they will choose the next steps in the plot of their story.

Through analysis of their narrative, the physician or nurse aims to escort a patient and family to resolution. At times, all options in a difficult case may be sad or undesirable. In such a situation, a happy ending may not be possible. Rather, the role of the medical providers can be to derive patterns from the voices, characters and plot in a family’s story, finding ways to take the tattered ends of the last chapter and begin a new story that is coherent with the one that came before. Focusing on resolution, the caregiver can help families and medical providers recognize the things that matter most to them, reminding them that whatever the challenges of their current situation, that there is still a good and valuable story to be told (Montello 2014).

Conclusion

Many medical providers have chosen their careers because they seek to cultivate the type of flourishing that can advance even when the medical prognosis worsens. It is important to them to encourage children and families to define for themselves what it means to live life well together. While clinical data may help these providers understand the intricacies of disease, it is narrative that helps them understand the richness of life. The role of the physician or nurse is to make a family’s story a lens through which clinical symptoms are revealed not as value-neutral “objective findings” but harbingers of triumph or grief, hope or loss.

In our study, we had the opportunity to interview seven families of children with T 13/18. These families described joys and challenges in navigating the plot twists of their child’s disease. They came to realize that within their experiences with T 13/18, a story had emerged that gave meaning to their lives. Admittedly, such stories can be as complex and opaque as the people who tell them. But amidst the confluence of voices and characters, there are themes that a provider can discover. Asking narrative questions and together mapping the things that are meaningful allows family members and providers to together craft the medical data into a path forward towards a broader experience of health and flourishing.

Limitations

Being a qualitative study, our interviews were not designed to provide universally generalizable data; rather, they were intended to identify important themes to consider when caring for a child with T 13/18.

Several factors likely explain our low response rate. First, our responses may have been limited by the choice to only send a single invitation to families. Additionally, it seems that having a longitudinal relationship with our hospital was important. Families were 8.8 times less likely to agree to an interview if their child spent less than 40 days in our hospital (22 of the 33 invited families had less than 40 hospital days). Finally, some of the families may have been deterred from participating by the distrust of the medical system expressed in the interviews, particularly when their relationships with our hospital had been more cursory.

It is also likely that our cohort was biased towards families who value narrative in the medical setting, as those who were interested in telling their story were more likely to respond to an invitation to talk about their child. However, it is important to note that those interviewed were a diverse group with regards to educational level, race and marital status; thus storytelling may serve an important function that applies in a variety of cultural settings.

Further research is needed to understand the families that choose not to engage in surveys such as this one or the online surveys by Janvier et al. and Kosho et al. Do these families have different desires for their children and their relationships with the medical staff than those who have deliberately chosen to speak on behalf of their children either online or in an interview? Such knowledge could help empathetic forecasting for families of children with T 13/18 as well as other severe or complex diagnoses.

Notes

Digoxin is a cardiac medication.

References

Quotes from interviews are marked by subject number. Transcriptions are not available for public viewing under IRB restrictions.

Bishop, J. P. (2011). The anticipatory corpse: Medicine, power, and the care of the dying. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (introducing qualitative methods). London: Thousand Oaks.

Charon, R. (2007). What to do with stories: The sciences of narrative medicine. Canadian Family Physician, 53(8), 1265–1267.

Davis, D. S. (1997). Genetic dilemmas and the child’s right to an open future. Hastings Center Report, 27(2), 7–15.

Donohue, P. K., Boss, R. D., Aucott, S. W., Keene, E. A., & Teague, P. (2010). The impact of neonatologists’ religiosity and spirituality on health care delivery for high-risk neonates. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 13(10), 1219–1224. doi:10.1089/jpm.2010.0049.

Guon, J., Wilfond, B. S., Farlow, B., Brazg, T., & Janvier, A. (2014). Our children are not a diagnosis: The experience of parents who continue their pregnancy after a prenatal diagnosis of trisomy 13 or 18. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A, 164(2), 308.

Halpern, J., & Arnold, R. M. (2008). Affective forecasting: An unrecognized challenge in making serious health decisions. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(10), 1708–1712. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0719-5.

Janvier, A., Farlow, B., & Wilfond, B. S. (2012). The experience of families with children with trisomy 13 and 18 in social networks. Pediatrics, 130(2), 293–298. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0151.

Josephsen, J. B., Armbrecht, E. S., Braddock, S. R., & Cibulskis, C. C. (2016). Procedures in the 1st year of life for children with trisomy 13 and trisomy 18, a 25-year, single-center review. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 172(3), 264–271. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31525.

Kosho, T., Kuniba, H., Tanikawa, Y., Hashimoto, Y., & Sakurai, H. (2013). Natural history and parental experience of children with trisomy 18 based on a questionnaire given to a Japanese trisomy 18 parental support group. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 161a(7), 1531–1542. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.35990.

Kukla, R. (2007). How do patients know? Hastings Center Report, 37, 27–35.

Kumar, P. (2011). Care of an infant with lethal malformation: Where do we draw the line? Pediatrics, 128(6), e1642–1643; author reply e1643-1644. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2869A.

Lakovschek, I. C., Streubel, B., & Ulm, B. (2011). Natural outcome of trisomy 13, trisomy 18, and triploidy after prenatal diagnosis. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 155a(11), 2626–2633. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.34284.

Maeda, J., Yamagishi, H., Furutani, Y., Kamisago, M., Waragai, T., Oana, S., et al. (2011). The impact of cardiac surgery in patients with trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 in Japan. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 155a(11), 2641–2646. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.34285.

McGraw, M. P., & Perlman, J. M. (2008). Attitudes of neonatologists toward delivery room management of confirmed trisomy 18: Potential factors influencing a changing dynamic. Pediatrics, 121(6), 1106–1110. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1869.

Meyer, R. E., Liu, G., Gilboa, S. M., Ethen, M. K., Aylsworth, A. S., Powell, C. M., et al. (2016). Survival of children with trisomy 13 and trisomy 18: A multi-state population-based study. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 170a(4), 825–837. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.37495.

Montello, M. (2014). Narrative ethics. Hastings Center Report, 44(1 Suppl), S2–S6. doi:10.1002/hast.260.

Moorhead, S. A., Hazlett, D. E., Harrison, L., Carroll, J. K., Irwin, A., & Hoving, C. (2013). A new dimension of health care: Systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(4), e85. doi:10.2196/jmir.1933.

Nelson, K. E., Hexem, K. R., & Feudtner, C. (2012). Inpatient hospital care of children with trisomy 13 and trisomy 18 in the United States. Pediatrics, 129(5), 869–876. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2139.

Peters, S. A., Laham, S. M., Pachter, N., & Winship, I. M. (2014). The future in clinical genetics: Affective forecasting biases in patient and clinician decision making. Clinical Genetics, 85(4), 312–317. doi:10.1111/cge.12255.

Powell, J., Inglis, N., Ronnie, J., & Large, S. (2011). The characteristics and motivations of online health information seekers: Cross-sectional survey and qualitative interview study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(1), e20. doi:10.2196/jmir.1600.

Wilkinson, D. J. (2010). Antenatal diagnosis of trisomy 18, harm and parental choice. Journal of Medical Ethics, 36(11), 644–645. doi:10.1136/jme.2010.040212.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate support received from Saint Louis University and SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital. Saint Louis University Department of Pediatrics provided the funding for this research.

Funding

This study was funded by the Saint Louis University Department of Pediatrics, Award Number: 2-00330.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arthur, J.D., Gupta, D. “You Can Carry the Torch Now:” A Qualitative Analysis of Parents’ Experiences Caring for a Child with Trisomy 13 or 18. HEC Forum 29, 223–240 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-017-9324-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-017-9324-5