Abstract

Health care professionals often face moral dilemmas. Not dealing constructively with moral dilemmas can cause moral distress and can negatively affect the quality of care. Little research has been documented with methodologies meant to support professionals in care for the homeless in dealing with their dilemmas. Moral case deliberation (MCD) is a method for systematic reflection on moral dilemmas and is increasingly being used as ethics support for professionals in various health-care domains. This study deals with the question: What is the contribution of MCD in helping professionals in an institution for care for the homeless to deal with their moral dilemmas? A mixed-methods responsive evaluation design was used to answer the research question. Five teams of professionals from a Dutch care institution for the homeless participated in MCD three times. Professionals in care for the homeless value MCD positively. They report that MCD helped them to identify the moral dilemma/question, and that they learned from other people’s perspectives while reflecting and deliberating on the values at stake in the dilemma or moral question. They became aware of the moral dimension of moral dilemmas, of related norms and values, of other perspectives, and learned to formulate a moral standpoint. Some experienced the influence of MCD in the way they dealt with moral dilemmas in daily practice. Half of the professionals expect MCD will influence the way they deal with moral dilemmas in the future. Most of them were in favour of further implementation of MCD in their organization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Professionals in care for the homeless face various moral issues (Mcgrath and Pistrang 2007; Renedo 2013; Timms and Borrell 2001). They experience some of these issues as moral dilemmas (Banks and Williams 2004; Keinemans and Kanne 2013). Responsible for providing good work, they must choose between two options which both inevitably include losses and involve emotions of remorse, regret or guilt (Macintyre, 1990; Nussbaum 1986, 2001). For example, a professional might feel caught between his professional duty to respect a client’s autonomy and his duty to protect the client against his life-threatening behaviour related to his alcohol addiction.

In the last century, social professionals in care for the homeless have been guided in providing good work and in dealing with moral dilemmas in several ways. What began as a philanthropic activity, inspired by clerically and educationally inspired principles, developed into professional care, guided by ethical codes of behaviour. Changing circumstances at the end of the twentieth century led to the (re)introduction of outreach work which, in turn, led to new dilemmas for professionals. Meeting homeless people in their own habitat instead of in the office, as practiced by the Salvation Army earlier that century required, for instance, reorientation of client-staff boundaries, due to the homeless person’s right to privacy in public spaces (Fisk et al. 1999). This reorientation led to the development of new guidelines for professional behaviour. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, professional behaviour in social professions has become increasingly structured by principles like ‘client autonomy’ and ‘empowerment’ as laid down in, sometimes evidence-based, recovery- and empowerment-oriented methodologies. Uniform guidelines were presumed to make care controllable, transparent, answerable, and accountable to both government and client systems.

However, despite these efforts, social workers still face dilemmas (Banks 2011; Dam et al. 2013; Doorn 2008; Hem et al. 2014; Keinemans and Kanne 2013; Weidema et al. 2012).

Banks (2011), discussing ethics in social professions in a time of neo-liberal policies, notices a focus on effectiveness, regulation, and individual ethical responsibility. She highlights the danger of the possible clash between professional assessment of what good care for a specific client should mean and the management’s assessment of good care. She pleads for more attention to situated ethics.

Similar developments are seen in The Netherlands. Budget cuts and target-oriented policy regulations, related to recent economic crises and Dutch decentralization of care, may present Dutch professionals with new dilemmas.

Simultaneously, in the last decades the view that professional decisions cannot be adequately legitimized by applying abstract rules alone gained ground (Walker 2003). Principles like autonomy and recovery are important ingredients of the dominant moral and legal framework and may serve as general guidelines. However, principles cannot prevent moral dilemmas which belong to the inevitable contingencies of (professional) life. They have to be customized and justified in different concrete situations. Moreover, two different principles may collide with each other (Nussbaum 1986). For example, a client, heavy alcoholic, may have the right to make the autonomous choice to drink himself to death. However, the professional may also feel bound to her professional duty to stimulate the client to recover, get healthy, and to stop drinking. How should the professional apply the principle of recovery, especially when it collides with the principle of autonomy?

Some authors point to the fact that experiencing moral dilemmas may cause uncertainty, which in turn may lead to moral distress. Uncertainty and distress could possibly hinder the ability to provide ‘good care’ and will therefore affect the quality of care (Molewijk et al. 2008a; Silén 2012).

Ethical support aids have been developed in order to assist professionals in dealing with their moral dilemmas in concrete situations. Moral case deliberation (MCD) is one of these aids. MCD is a structured, democratic method of dialogically reflecting and deliberating on moral questions (Dartel and Molewijk 2014; Kessels et al. 2013; Molewijk and Ahlzen 2011; Nelson, 1994). It is based on the assumption that, in line with hermeneutical views (Gadamer 2010), decision making is an inherently normative and context-sensitive activity that is dialogically framed within contexts in interaction with all kinds of knowledge and daily, personally, or generally accepted judgments, thoughts, and emotions. A moral dilemma is regarded as a valuable source of experiential knowledge which serves as a wake-up call and suitable starting point for moral deliberation (Kessels et al. 2013).

Groups that practice MCD usually consist of 8–12 people. Different conversation methods can be used in MCD, such as the dilemma method or the Socratic dialogue (Kessels et al. 2013; Molewijk and Ahlzen 2011). The dilemma method helps professionals to formulate a decision, or differences in opinion in the case of a concrete moral dilemma. Socratic dialogue helps professionals to gain insight into moral questions, helps to search for consensus, but does not necessarily lead to a decision. A dilemma question is, for instance: Should I withdraw care from a client who does not meet the institution’s treatment criteria or not? A moral question suitable for deliberation in Socratic dialogue is, for instance: What does client-centered care in this situation mean? Reflection and dialogue are the most vital and indispensable elements of MCD, and they are more important than following the methodical steps.

MCD as clinical ethical support (CES) was introduced in the last decade in (mental-) health care. Professionals in different professional settings in (mental-) health care and elderly care report that they feel that MCD strengthened their ability to deal with moral dilemmas (Dam et al. 2013; Molewijk et al. 2008b; Stolper et al. 2012; Weidema et al. 2012).

In 2011, the management of a Dutch institution for care for the homeless asked the first author to help them to investigate whether MCD could help the professionals to deal with their moral dilemmas. They decided to start a phased project to find out if MCD could be of value. Evaluation research would sustain the management in their decisions about potential implementation of MCD. So far, little experience has been documented with methodologies meant to support professionals in care for the homeless in dealing with their moral dilemmas (i.e., ethics support). Nor is it sufficiently clear how professionals perceive the contribution of MCD in their dealing with moral dilemmas. This research aims to fill this gap.

This report describes the second phase of the project: the evaluation research concerning this moral case deliberation (MCD) pilot project in a Dutch institution for care for the homeless. The research question is:

What is the contribution of MCD in supporting professionals in an institution for care for the homeless to deal with moral dilemmas?

Context of Study

The entire evaluation research had two goals: the monitoring of implementation of MCD and formative evaluation of the contribution of MCD to professionals’ experienced ability to deal with moral dilemmas. The project and the research consisted of three phases: in the first phase, the moral dilemmas professionals faced, how they dealt with moral dilemmas and the professionals’ need for ethics support were investigated (Spijkerboer, Stel, Molewijk and Widdershoven, accepted for publication). The second phase concerned evaluation of a pilot of 3 MCDs in a limited number of teams. Following the pilot, management was decidedly positive on the continuation of the project and further implementation of MCD. This article presents the results concerning the evaluation of MCD during the pilot (i.e., the second phase). The research concerning the implementation of MCD is not included in this article.

The institution for care for the homeless under study provides ambulant, crisis, residential, and outreaching care to homeless people in different cities and villages in the Western part of The Netherlands. At the time of the research, 95 professionals worked mostly as (semi-) residential or ambulant social workers alongside 15 managers, team coordinators, and workers with facilitating and advisory functions. Preliminary research (first phase of the project) in the institution—investigating the moral dilemmas professionals faced and how they dealt with them (Spijkerboer et al., accepted for publication)—showed that professionals encountered major moral dilemmas related to rules, although at the same time these rules helped them to deal with moral dilemmas. Other dilemmas were related to a professional’s care to preserve the client’s autonomy, the supposed importance of keeping a client’s trust, and to cooperation with diverse colleagues. As this research proved the need for support, the management of the institution decided to start a pilot of MCD.

Intervention and data sampling took place from January until July 2013. Most professionals had never attended MCD before.

Two BA student researchers, writing a research report in their final year at the Leiden University of Applied Sciences and having finished their year-long traineeship in care, carried out the interviews under the guidance of the first author. The whole research process was supervised by three academic supervisors (GW, BM, JS).

Methodology

A mixed-methods research design was chosen (Greene 2007; Mertens 2010). Quantitative research was used to gain insight in the way professionals experienced MCD and to formulate new questions. Qualitative research was subsequently used to check the results and deepen the insights (Greene 2007; Mertens 2010).

In correspondence with the views of Greene (2007), mixed methods are regarded as advocating enquiry of, reflection on and dialogue between epistemological assumptions of both qualitative and quantitative methods in order to enhance validity of data and conclusions. Both methods are estimated to represent their own ‘wisdom’. Quantitative research was used to gain insight in the way professionals experienced MCD and to formulate new questions. Qualitative research was subsequently used to check the results and deepen the insights (Greene 2007; Mertens 2010).

Responsive evaluation is a reaction to traditional top-down research methods in which often merely the researchers define the core research question. Responsive evaluation starts from questions, views and goals of stakeholders (management and professionals of the institution) without defining preconceived standards as cardinal points for evaluation. In practice, this means that the meaning of results and conclusions is negotiated in continuous dialogue between management, professionals and researchers by member checking found data with professionals and discussing results with the management. For example, in this second phase member checks were meant to further validate the meaning of the quantitative findings. At the same time, they stimulated stakeholders’ ownership of research outcomes and facilitated implementation of the intervention (i.e., MCD). Moreover, continuous consultation of critical voices is meant to prevent unbalanced and incorrect conclusions. This procedure necessitates thick description of the research process, enabling external transfer to other institutions and researchers; it enables them to assess the value of the results for their own institution or research and to use insights in an appropriate way. Therefore, the procedure and process of the research were transparently described with sufficient detail (Mertens 2010).

MCD and the responsive research design are both action-oriented. They both start from the presumption that action provides knowledge. Together they pursue inclusion of all participants in both the normative debate during MCD, as well as in the validation of knowledge generated by the research by member checks (Greene and Abma 2001; Weidema et al. 2012; Abma et al. 2009; Mertens 2010), ensuring synchronization of the implementation process with the dialogical nature of the intervention itself (Weidema et al. 2012).

Research Question

The research question was: What is the contribution of MCD in supporting professionals in an institution for care for the homeless to deal with moral dilemmas? The participating professionals’ evaluation of MCD as a method, and the effects that participants experienced when dealing with dilemmas after having attended 3 MCDs in a pilot were investigated.

Intervention: MCD

MCD is a group meeting in which a structured conversation method is used (Dartel and Molewijk 2014; Kessels et al. 2013). It starts from the epistemological assumption, inspired by Aristotelian (Aristotle 2008), Socratic (Nelson 1994; Kessels et al. 2013), hermeneutical, and dialogical (Gadamer 2010) views, that decision-making is a dialogical context-dependent moral activity instead of a matter of applying ethical theories (such as consequentialism or deontology) in a deductive way. MCD starts with how participants experience and interpret the situation. Answers to moral questions are supposed to develop during the MCD process in interaction with others (Molewijk et al. 2008a) and by becoming aware of their intricacy and of their historical and contextual background. Decisions have to be justified in a concrete case with the help of conscientious joint deliberation with several stakeholders. Deliberation starts from the experience of conflict or unease that is regarded to be an important moment to start reflection and deliberation on moral dilemmas/questions.

Facilitators of MCD serve as a Socratic guide and facilitate dialogue, reflection and deliberation on moral dilemmas by stimulating participants to communicate in an open way, by asking open questions and empathizing with others’ opinions. They encourage critical questioning of presuppositions (Abma et al. 2009; Kessels et al. 2013; Molewijk et al. 2008a). They do not function as an advising expert but are process oriented instead. They support participants to concentrate on and deliberate about a moral question/dilemma. They support dialogue instead of debate, postponement of initial judgments, investigation of and reflection and deliberation on values and norms related to the moral dilemma or question in the concrete case. Investigation of different perspectives by asking open questions and empathizing with each other is supposed to help broaden the view on the moral question and is regarded as conditional for moral deliberation. In this way, MCD fosters moral competences and enables participants to deal responsibly with moral dilemmas.

The dilemma method was chosen in all MCDs during the pilot (Molewijk and Ahlzen 2011) (Appendix Table 6). Participants learn to justify their decision in a dilemma in the concrete case and to formulate a consensus or differences in vision. The method contains several steps, although continuous reflection, deliberation and scrutinization of each others' reasoning are the most important ingredients. Investigation of facts, their meaning, associated emotions and related values are integrated in steps one, two, three, and four. This investigation helps the case presenter to formulate the most authentically experienced dilemma and to identify the underlying moral question as distinguished from other professional dilemmas and questions. In step five, the values and norms—linked to these facts, emotions, and meanings—are investigated, reflected on, and balanced from different perspectives. Brainstorming about possible alternatives takes place in step six. Answers, consensus and/or differences are formulated in steps seven and eight.

Facilitators in the pilot were trained (Stolper et al. 2015) in securing these conditional aspects of MCD.

Information meetings were organized beforehand with each team, lasting approximately 15 minutes, in which basic information was given about MCD (goal of the pilot, short explanation about MCD, confidentiality, evaluation research) and in which participants could ask questions. All teams voluntarily decided to let their team managers participate in MCD.

Research Methods

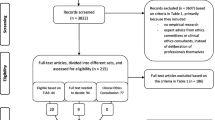

Quantitative (questionnaires: slightly adapted, not validated questionnaires (Molewijk et al. 2008b; Molewijk et al. 2008c) and qualitative methods (individual interviews, two rounds) were sequentially used (Fig. 1) to answer the research question. The individual interviews were meant to check the results from the questionnaires, deepen the interpretation and investigate new, emerging questions (Greene et al. 1989).

Questionnaires were filled in immediately after each MCD by each participant. Each question in the questionnaire (43 questions) could be answered on a Likert scale 1–5 (Molewijk et al. 2008b; Molewijk et al. 2008c). Topics covered by the questionnaire were: evaluation of MCD in general, evaluation of MCD as a useful method to deal with moral dilemmas, supposed effect of MCD (such as the experienced ability to identify the moral question, values and norms, or the experienced/supposed effect on dealing with moral dilemmas in daily work), quality of the dialogue, facilitator, and introduction pilot. Participants could also provide comments. Questions that were added to the questionnaire were: I felt involved in the conversation and the four questions concerning the experience of the implementation process. These questions and the related findings are not included in this report.

Interview topics in both rounds (qualitative research) were formulated on the basis of former outcomes from quantitative (round one) and quantitative/qualitative data (round two) (development). Interview topics (Appendix Table 7) in round one (six respondents) were discussed by the researcher/first author and student researchers and defined by them, the students were supervised by two authors. The topics were: experiences, introduction, facilitators, preconditions, experienced effects on dealing with moral dilemmas/in daily work, suggestions. The first topic (‘experiences’) was questioned in an open way, after which the interviewers asked for clarification when needed. Insights were checked for the second time on convergence and divergence in round 2, because new questions came up when qualitative and quantitative data did not correspond. Questions in both rounds were partly adapted to each team, depending on the specific quantitative data from that team. Quantitative data showed, for instance, that participants in one team evaluated the contribution of MCD to their ability to deal with moral dilemmas as less useful than in other teams. The interview question was: ‘Can you explain this difference in outcome?’

Facilitators’ and student researchers’ (who attended 9 MCDs) written reflections concerning the perceived conversational atmosphere, participants’ conversational skills and existing moral competences were gathered and discussed after every MCD. This was to secure, adjust, and enhance the quality of the facilitation process by fine-tuning inevitably different facilitating styles. Students, when present, also filled in skills assessment lists to evaluate the facilitators’ skills, the results of which were discussed by facilitators.

Both student researchers were trained in asking open and supplementary questions. They signed statements of confidentiality beforehand in order to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of participants in MCD and research.

Participants

Five teams volunteered to participate in the MCD project: the management team, an intake team, a team providing residential care, a crisis-care team, and an ambulatory team. One of the teams was split into two because the group was too large. All six groups (4–10 members) participated three times in a MCD. Each MCD lasted one and a half hours. The total number of participants was 39; not all could always attend the MCD due to work-related priorities, illness, or holidays. The number of times each participant attended MCD was not tracked. MCDs were facilitated by three different certified MCD facilitators (1:12x [first author], 2:5x, 3:1x).

The 39 participants filled in a total of 102 questionnaires immediately after each MCD.

Some interview respondents (round 1) signed up voluntarily after a general request. Two respondents who were critical of MCD were explicitly invited to participate. Both consented to do so. The six respondents for member-check interviews of round 2 were recruited by chance, based on their attendance at work on the appropriate day. Respondents in round two differed from those in round one, which was checked beforehand.

Analysis

Results of the questionnaire were described and analyzed in SPSS18. On a Likert scale (1:lowest score; 5:highest score), scores ≤2.9 were regarded as low scores, scores ≥3 and ≤3.4 were regarded as moderate scores. Scores ≥3.5 were seen as positive and scores ≥4 as very positive. Due to the limited number of MCDs and participants, no multivariate analysis was executed. Written comments were noted.

Interviews from round one were transcribed. Notes were made during the second-round interviews. Data were coded in an open way (Mertens 2010). Codes were first defined by each individual researcher (first author and two student researchers) and subsequently discussed and determined by consensus, supervised by the supervisors.

Finally, some quantitative and qualitative codes, such as ‘perspectives’, were analyzed together for the purpose of comparison, complementarity and triangulation (Mertens 2010; Greene et al. 1989).

Research Ethics

Participants in the quantitative part of the research were informed orally about the goal of the research. They filled in the questionnaires anonymously and were allowed to refuse to return the questionnaire. In the qualitative part of the research, participants were informed about the goal of the research and the fact that anonymity would be assured orally or in writing. Data was stored confidentially and anonymously. All interviewees gave their consent for the data to be used for research by signing a consent form. Student researchers signed statements of secrecy in order to ensure confidentiality during and after the research process.

Results

This section presents the results of the research. The research question was: What is the contribution of MCD in supporting professionals in an institution caring for the homeless to deal with moral dilemmas?

First, some examples of the discussed moral dilemmas are presented, followed by a general evaluation along the themes: dilemma method; relation reflection-ethical protocols; managements’ participation in the MCD meetings. Subsequently, the results concerning the contribution of MCD to participants’ ability to deal with moral dilemmas are presented along the themes: conditions for moral competence (cooperation, communication, empathizing); formulating the moral dilemma; different perspectives; expected and experienced effect of MCD on dealing with moral dilemmas in daily work.

In each section, the quantitative results are presented first, followed by the qualitative results, in order to clarify the extent to which quantitative data are confirmed, disconfirmed, deepened or supplemented.

Discussed Moral Dilemmas

In the 18 MCDs, 18 moral dilemmas were discussed. Examples of dilemmas that were discussed are: May I allow client X to drink alcohol that endangers his health or not? May I exclude client Y from care when he does not adhere to the institution’s rules or not?

The Dilemma Method

Quantitative data show that professionals valued the three MCDs as positive (Table 1).

Respondents thought MCD touched upon the essence of their work (mean 4.03). They felt very involved in the deliberation (mean 4.14). Some written comments given by participants in the questionnaire were: “It was nice, fascinating”; “It was good to do MCD in a little group; everyone got his turn”; “Nice to hear what others think and would like to do”. MCD is seen by one interviewee as a method that exceeds the personal perspective by also paying attention to organizational and policy levels. A respondent qualified MCD as a method stimulating good professional intentions: “It is about you as a professional and brings out the best in you” (R1). Another respondent said: “[The method] helps to clarify the dilemma and that is what it is all about” (R3).

Qualitative data showed that some respondents believed that the structure of the method helped their team to use the time for deliberation effectively: “It is important for our team to stick to the method” (R5). The use of a structured method and elucidation of the various perspectives helped participants to keep focused during deliberation:

“The gradually increasing focus forces you to fill in different perspectives, values, and norms […….]. Occasionally, we had difficulty in doing this. But it is good to have difficulties, which makes it more precise” (R3).

Some respondents valued the practical guide MCD offers for gaining insight instead of finding the practical solution: “MCD has to stimulate insight. That should be the profit” (R3).

Relation Reflection-Ethical Protocols

Qualitative data show differences in the extent to which protocols should be reflected on in MCD. MCD should, according to one respondent, be exclusively focused on issues in which protocols are absent: “I don’t need to talk about this. It is in the protocol that it is not allowed” (R2). On the other hand, one interviewee said, “Our work is full of procedures, prescriptions, and methods. When you analyze the question, you inevitably have to wonder what it all means” (R3). The same respondent mentioned that MCD can serve as a means to adjust protocols when necessary, with the additional effect that protocols stay alive in professionals’ heads.

Participation of Management and Other Colleagues

Most participants felt comfortable with the team coordinator as participant in MCD. Others suggested that a coordinator’s participation should be considered for every single meeting. MCDs with participants from different locations/teams and professionals from within the institution as MCD facilitators were recommended.

The management team also participated as a team in MCD. This was felt by some as stimulating their involvement and participation in the pilot.

Contribution of MCD to Participants’ Ability to Deal with Moral Dilemmas

Cooperation, Communication, Empathizing

Quantitative results show that participants experienced other participants as very interested in the deliberated issue (mean of 4.04) and also valued the quality of conversational skills in themselves and in other participants. Participants experienced their colleagues as trying to listen to each other and trying to empathize (Table 2). According to participants, MCD fosters working together as a team and team communication (mean:3.74).

Qualitative results show that respondents appreciate the better cooperation MCD can bring but they do not regard it as the main goal of MCD. One respondent says she appreciated exchanging insights with colleagues and to hear their reasons:

“….I appreciate talking about it with colleagues…and you hope they also will tell what their reasons are….” (R2),

Another interviewee emphasized that MCD should not be used as a means to improve team cooperation: “MCD is not about cooperation; it is about the moral case” (R3). Instead, other methods were seen as appropriate to focus on cooperation issues, like intervision. At the same time, some interviewees said that MCD should have the goal that colleagues will understand each other better.

Another respondent said, “[Better cooperation] is not the goal of MCD, but can be a bonus” (R6).

Some respondents said there was already an atmosphere of open communication in their team. Therefore, they did not expect MCD to enhance their team communication. They expressed their wish to learn more about other perspectives in the future instead.

The open and nonjudgmental atmosphere, which allowed people to dare to say what they thought, was valued.

Formulating the Moral Dilemma

Quantitative data (Table 3) show that participants did not experience great difficulty in recognizing a moral dilemma or in formulating the underlying moral question. They were moderately helped by MCD. Participants thought the discussed issues were not too difficult (mean:3.2), but did find that MCD gave them a better understanding of them (mean:3.5).

Qualitative findings shed more light on these findings. Some interviewees said it was difficult to identify the moral dilemma and to unravel the moral question and values at stake. MCD helped them to do so. “Sometimes it was very easy. But sometimes it was difficult to find out if it was a moral question or not” (R 5); “In every MCD it has been hard to get the moral question clear” (R3). Interviewees said they valued taking time to investigate the dilemmas and the norms and values at stake. MCD focuses on aspects that could remain hidden and prevents participants from drawing conclusions too fast.

Respondents indicated that they did not want to spend time in MCD choosing a dilemma (Appendix Table 6). According to them, MCD should have a clear focus and be prepared with a written case/dilemma beforehand in order to make optimum use of time during MCD. Interviewees were critical about the chosen dilemmas. They said they were not interested in the chosen dilemma or wanted other themes to be discussed.

Different Perspectives

Quantitative data show that participants became more aware of their own and others’ perspectives and values (Table 4). This is confirmed by qualitative data. MCD helps professionals to learn about their own stances. An interviewee described how her opinion became clear after considering different client values with her colleagues. She came to the conclusion that the client under consideration deserved a decent life, although he only seemed to want beer. The value of the right to a decent life was deemed more important that the value of autonomy and a client’s own choice. “Normally these opinions are not discussed. It is good to learn what your opinion is and why your colleague thinks differently’’ (R4).

MCD allows professionals to better understand each other’s vision. Moreover, to get to know the way colleagues justify their opinions is appreciated: “You know each one’s opinions. But to know how someone comes to this position helps in justifying” (R1). MCD helps to test your own view against that of colleagues, especially those with whom you do not easily talk. Focusing on other perspectives and not only on your own is seen as an additional value of MCD: “I think it is a very nice method, because it not only focuses on your own standards and values but on those of all team members” (R5).

Expected and Experienced Effect of MCD on Dealing with Moral Dilemmas in Daily Work

Half of the participants (50) expect that MCD will influence their daily work in the future. Thirteen participants did not expect that MCD would influence their daily work; 23 did not know at that time; 15 participants did not fill in the answer. Participants thought that MCD should have consequences for institutional policy (Table 5).

MCD also had immediate practical effects regarding the care for the clients/patients, as qualitative data show. Interviewees reported that MCD influenced the way clients were treated and how decisions were justified and carried out. In one MCD, a solution was found for a situation where the rules prevented participants from following a client’s own choice. By allowing the client to choose his own punishment, both important values (following the rules and respect for client’s autonomy) were complied with. One respondent said, “The first and last deliberation had practical effects. We said to each other: ‘we have to put this decision into practice’” (R3).

Discussion

This article presents results of an evaluation study of a pilot MCD in a Dutch institution for care for the homeless. The research question was: What is the contribution of MCD in supporting professionals in an institution for care for the homeless to deal with moral dilemmas?

Professionals in the present study generally evaluated MCD positively. They felt highly involved in MCD and thought MCD touched the essence of their work. As the results above show, professionals felt that MCD moderately to greatly affected the way in which they dealt with their moral dilemmas. Some recognized moral dilemmas better, and were supported in unraveling norms and values in the moral dilemma discussed. They became aware of other perspectives and felt supported in identifying their own and others’ values and norms. MCD helped them to reflect on the norms and values at stake and to formulate their opinion.

MCD has been previously evaluated in health care, including elderly care (Dam et al. 2013; Janssens et al. 2015), and mental-health care (Molewijk et al. 2008b, 2008c; Weidema et al. 2012). MCDs in the present research were carried out on a smaller scale than in the other studies discussed here: fewer MCDs and fewer participants were involved. Nevertheless, similarities and differences are seen when results of quantitative figures and qualitative findings are compared. These are addressed below.

Professionals in our study valued the three MCDs in which they participated as positively as the professionals in comparable institutions in mental-health care did (Molewijk et al. 2008b, 2008c).

Method, Conditions for Moral Deliberation

Professionals participating in our study value the structured way of deliberating in MCD. MCD met the conditions related to communication and empathizing as formulated before the project. Attention to communicative skills does not need to be a focus for all participants to the same extent. MCD influences team cooperation positively according to our study, although some professionals say the goal of MCD should be moral deliberation instead of better cooperation. It is not clear to what extent MCD contributed to stimulating participants’ ability to empathize. It is possible that they were already able to empathize, but did not have enough time or opportunity in their daily work to do so. MCD helped to create conditions and gave opportunity for moral deliberation. It seems to be important to take the time for empathy (Kessels et al. 2013).

Formulating the Moral Dilemma and the Moral Question

Professionals in our study experienced some, but not too much, trouble with formulating the moral question, as did the mental-health care professionals. The respondents in homeless care seem to find it less difficult to recognize the moral question than their colleagues in a mental health-care ward (Molewijk et al. 2008c). It is possible that the professionals overestimated their moral awareness. However, this can also be related to the fact that organizations who care for the homeless are horizontally structured organizations, in which professionals feel responsible for their decisions and actions. They possibly regard moral dilemmas as a recognizable and identifiable part of their job. It is not clear if this is different for mental-health-care professionals.

Professionals in care for the homeless seem to be moderately supported by MCD in recognizing or formulating a moral dilemma. Qualitative data showed that MCD helped them more or less in doing this. MCD gave them insight into the discussed dilemma. Mental-health-care professionals gave high scores to the function of MCD for gaining insight into moral issues, and for paying attention to reasons and arguments (Molewijk et al. 2008b). In another mental-health ward, participants reported an increase of insight into moral issues in the mental-health-care institution (mean 7.95 on a scale of 1–10) (Molewijk et al. 2008c). This difference in evaluation is possibly related to their assumed understanding of moral issues before MCD, to better quality of MCD in mental-health care, or to the low number of MCDs that was part of this pilot. Learning takes time, and maybe the available time was too short.

Perspectives

Professionals in our study became more aware of other perspectives. They recognized the moral dilemmas and associated values better. Other studies’ data are in line with these findings: MCD contributed to the understanding of each other by broadening perspectives (Weidema et al. 2012). Professionals in elderly care learned to acknowledge and integrate multiple perspectives (Janssens et al. 2015).

Contribution to Care and Dealing with Moral Dilemmas

Half of the professionals in care for the homeless expected MCD to influence their daily work in the future. Eighty-five percent of the respondents in a mental-health-care ward expected the same (Molewijk et al. 2008c). Participants in our study said MCD influenced how they dealt with their moral dilemmas in daily practice. No conclusions can be drawn concerning the question if the conclusions they made were responsible decisions in the eyes of others besides themselves.

Some professionals in our study mentioned concrete examples of the influence MCD had on the way they dealt with moral dilemmas. Many professionals in the other studies think that MCD affects the quality of care. Professionals in mental-health care thought MCD brought better quality of care, because it fostered client-centered care (Weidema et al. 2012). Professionals in elderly care say MCD raises awareness and understanding, thus promoting deliberation on moral issues (Janssens et al. 2015). They consider that improved communication and better understanding contributed directly to the quality of care. The present study shows that professionals in care for the homeless thought MCD raised their awareness of other perspectives and improved mutual collegial understanding, without directly estimating that these elements improved quality of care. It is not clear where these differences come from. Maybe the pilot in care for the homeless included too few MCDs for professionals to be able to experience direct influences on their daily work. Apart from these findings, no study has sufficiently clarified in what way MCD really affects the quality of care.

All findings together indicate that MCD affects professionals’ way of dealing with moral dilemmas. Professionals’ ability to identify moral dilemmas, questions, and conflicting values at stake, i.e., their awareness of moral issues, is enhanced. Dauwerse et al. (2013) stated that moral awareness is an important part of the institution’s ethical climate, next to the attention to ethical issues, the fostering of ethical reflection and the support given to employees to do so. A good ethical climate may lower moral distress and MCD plays an important role in creating this climate.

Professionals’ ability to investigate and discuss conflicting values at stake in dialogue with other people’s perspectives is also enhanced. This may have influenced their moral reasoning, but this is not clear.

Some professionals report MCD influenced their dealing with dilemmas in daily practice. It is not clear to what extent MCD influenced concrete behaviour in practice. Future research can help to answer this question by questioning professionals’ dealing with moral dilemmas after participating in MCD.

As described in the introduction, moral case deliberation is considered to be an activity that requires dialogue, investigation, reflection and deliberation on arguments and assumptions of MCD participants, instead of a matter of applying ethical theories or preconceived standards of ethical reasoning. Decision making is considered to be a dialogical and hermeneutical activity that requires joint investigation, reflection and deliberation on assumptions, instead of a matter of applying ethical theories or preconceived standards of ethical reasoning. MCD gives room to and stimulates this process by supporting joint investigation, reflection, and deliberation. Findings do not shed light on right or wrong legitimation of justifications.

Findings show that participants felt supported in dealing with moral dilemmas by becoming aware of other perspectives and of the moral dimension of dilemmas. Some professionals report MCD influenced their dealing with dilemmas in daily practice. They apparently perceive MCD as a support in dealing with moral dilemmas in practice. Since this study did not aim at measuring effects we cannot say to what extent MCD influenced concrete behaviour in practice or to what extent MCD influenced quality of care or clients. Future research can help to shed a light on this question by questioning professionals’ dealing with moral dilemmas after participating in MCDs or by investigating clients’ experiences of professional treatment after they participated in MCDs.

According to the MT, the criteria they formulated in advance were sufficiently met. As a consequence, the management team decided to continue the project and implement MCD further with more voluntarily participating teams and with educated facilitators from the institution.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Only a limited number of professionals (39) participated in this study. Conclusions can therefore only be drawn with care and are not generalizable to other contexts. Comparison with research data from relatively comparable contexts, mental-health institutions and an institution for elderly people, made it possible to validate conclusions and to generate new questions due to divergent outcomes. General validity of the research findings can be enhanced in the future by using validated questionnaires, by doing research with the same and other designs and through multiple case studies (Greene 2007; Mertens 2010). Subsequently, new designs, developed on the basis of this knowledge, may contribute to knowledge about the effect of MCD on professionals’ behavior in daily practice or to quality of care.

The use of student researchers as interviewers was, on the one hand, regarded as a strength in the research. Respondents possibly gave their information more easily because they were recruited by student researchers whom they considered their equals, which may have been different in the case of the main researcher. It facilitated participants to express their views on MCD because their role as a student possibly gave less rise to participants’ feelings of power difference (Mertens 2010). Their trainee experience the year before the research possibly made it easy for them to empathize with participants, which may have facilitated the interviews. On the other hand, student researchers lacked significant interview experience. Although they were trained in open questioning, this may have prevented them from finding deepening insights.

Conclusion

Professionals in care for the homeless face various moral dilemmas. MCD as ethics support has been evaluated positively. Results of this evaluation study show that MCD helped professionals in dealing with their moral dilemmas: MCD enhanced professionals’ ability to recognize and understand moral dilemmas and conflicting values. It helped participants to become aware of other perspectives. It also helped to create conditions for making moral considerations in dialogue with other perspectives. We recommend future action-oriented research and other research designs to help make conclusions more robust and help management, staff, and professionals of different institutions to make accountable decisions.

References

Abma, T., Molewijk, B., & Widdershoven, G. A. M. (2009). Good care in ongoing dialogue. Improving the quality of care through moral deliberation and responsive evaluation. Health Care Analysis, 17(3), 217–235.

Aristotle. (2008). Ethica Nicomachea. Translated by Hupperts, C. and Poortman, B. Budel: Uitgeverij Damon.

Banks, S. (2011). Ethics in an age of austerity: Social work and the evolving new public management. Journal of Social Intervention, 20(2), 5–23.

Banks, S., & Williams, R. (2004). Accounting for ethical difficulties in social welfare work: Issues, problems and dilemmas. British Journal of Social Work, 35(7), 1005–1022.

Dauwerse, L., Abma, T., Molewijk, B., & Widdershoven, G. (2013). Goals of clinical ethics support. Perceptions of Dutch Health Care Institutions. Health Care Analysis, 21(4), 323–337.

Fisk, D., Rakfeldt, J., Heffernan, K., & Rowe, M. (1999). Outreach workers’ experiences in a homeless outreach project; issues of boundaries, ethics and staff safety. Psychiatric Quarterly, 70(3), 231–247.

Gadamer, H.-G. (2010). Wahrheit und Methode (7. Aufl.) [Truth and Method] (7th ed.). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Greene, J. C., & Abma T. A. (Eds.). (2001). Responsive evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 92, 1–105.

Greene, J. (2007). Mixed methods in social inquiry. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Greene, J., Caracelli, V., & Graham, W. (1989). Towards a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255–274.

Hem, M. H., Molewijk, B., & Pedersen, R. (2014). Ethical challenges in connection with the use of coercion: A focus group study of health care personnel in mental health care. BMC medical ethics,. doi:10.1186/1472-6939-15-82.

Janssens, R. M. J. P. A., van Zadelhoff, E., van Loo, G., Widdershoven, G. A. M., & Molewijk, B. A. C. (2015). Evaluation and perceived results of moral case deliberation: A mixed methods study. Nursing Ethics, 22(8), 870–880.

Keinemans, S., & Kanne, M. (2013). The practice of moral action: A balancing act for social workers. Ethics and Social Welfare, 7(4), 379–398.

Kessels, J., Boers, E., & Mostert, P. (2013). Free space: Field guide. Amsterdam: Boom.

Macintyre, A. (1990). Moral dilemmas. Philosophy and phenomenological research, 1(50), 367–382.

Mcgrath, L., & Pistrang, N. (2007). Policeman or friend? Dilemmas in working with homeless young people in the United Kingdom. Journal of Social Issues, 63(3), 589–606.

Mertens, D. (2010). Research and evaluation in education and psychology. Los Angeles: Sage publications.

Dartel, H. van, & Molewijk, B. (2014). In gesprek blijven over goede zorg. Overlegmethoden voor ethiek in de praktijk [Keep on deliberating on good care. Conversation methods for ethics in practice]. Amsterdam: Boom.

Molewijk, A. C., Abma, T., Stolper, M., & Widdershoven, G. (2008a). Teaching ethics in the clinic: The theory and practice of moral case deliberation. Journal of Medical Ethics, 34(2), 120–124.

Molewijk, B., & Ahlzen, R. (2011). Should the school doctor contact the mother of a 17-year-old girl who has expressed suicidal thoughts? Clinical Ethics, 6, 5–10.

Molewijk, B., Verkerk, M., Milius, H., & Widdershoven, G. (2008b). Implementing moral case deliberation in a psychiatric hospital: Process and outcome. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 11(1), 43–56.

Molewijk, B., Zadelhoff, E., Lendemeijer, B., & Widdershoven, G. (2008c). Implementing moral case deliberation in Dutch health care: Improving moral competency of professionals and quality of care. Bioethica Forum, 1(1), 57–65.

Nelson, L. (1994). De socratische methode [The Socratic method]. Amsterdam: Boom.

Nussbaum, M. (1986). The fragility of goodness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nussbaum, M. (2001). Upheavals of thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Renedo, A. (2013). Care Versus Control: The Identity Dilemmas of UK Homelessness Professionals Working in a Contract Culture. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 24(3), 220–233.

Silén, M. (2012). Encountering ethical problems and moral distress as a nurse. Experiences, contributing factors and handling. 2012. http://hj.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:450421/FULLTEXT02.pdf. Accessed 13 Feb 2016.

Stolper, M., Metselaar, S., Molewijk, B., & Widdershoven, G. (2012). Moral case deliberation in an academic hospital in the Netherlands. Tensions between theory and practice. Journal international bioétique, 23(3–4), 53–66.

Stolper, M., Molewijk, B., & Widdershoven, G. (2015). Learning by doing. Training health care professionals to become facilitator of moral case deliberation. HEC Forum, 27(1), 47–59.

Timms, P., & Borrell, T. (2001). Doing the right thing—ethical and practical dilemmas in working with homeless mentally ill people. Journal of mental health, 10(4), 419–426.

van der Dam, S., Schols, J. M.G.A., Kardol, T. J.M.; Molewijk, B. C., Widdershoven, G. A.M. & Abma, T. A. (2013). The discovery of deliberation. From ambiguity to appreciation through the learning process of doing Moral Case Deliberation in Dutch elderly care. 2013; In Dam, van der S. Ethics support in elderly care. Maastricht: Universitaire Pers Maastricht. pp 95–113.

van Doorn, L. (2008). Morele oordeelsvorming [Moral judgment]. Maatwerk, 9(4), 4–7.

Walker, U. (2003). Moral contexts. Maryland: Rowland & Littlefield Publishers.

Weidema, F. C., Molewijk, A. C., Widdershoven, G. A. M., & Abma, T. A. (2012). Enacting ethics: Bottom-up involvement in implementing moral case deliberation. Health Care Analysis, 20(1), 1–19.

Spijkerboer, R. P., Widdershoven, G. A. M., Stel, J. C. van der, & Molewijk, A. M. Moral dilemmas in care for the homeless: What issues do professionals face, how do they deal with them and do they need ethics support? Accepted for publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Guus Bakker and Tisra van Exel for their contribution as student researchers to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spijkerboer, R.P., van der Stel, J.C., Widdershoven, G.A.M. et al. Does Moral Case Deliberation Help Professionals in Care for the Homeless in Dealing with Their Dilemmas? A Mixed-Methods Responsive Study. HEC Forum 29, 21–41 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-016-9310-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-016-9310-3