Abstract

Ethics consultation is a commonly applied mechanism to address clinical ethical dilemmas. However, there is little information on the viewpoints of health care providers towards the relevance of ethics committees and appropriate application of ethics consultation in clinical practice. We sought to use qualitative methodology to evaluate free-text responses to a case-based survey to identify thematically the views of health care professionals towards the role of ethics committees in resolving clinical ethical dilemmas. Using an iterative and reflexive model we identified themes that health care providers support a role for ethics committees and hospitals in resolving clinical ethical dilemmas, that the role should be one of mediation, rather than prescription, but that ultimately legal exposure was dispositive compared to ethical theory. The identified theme of legal fears suggests that the mediation role of ethics committees is viewed by health care professionals primarily as a practical means to avoid more worrisome medico-legal conflict.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

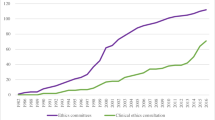

Clinical ethical dilemmas are a common occurrence in medical practice. These challenging situations, ranging from the authority of surrogate decision makers to moral distress to futility, often cause a paralysis in the progression of patient care and can create tensions among health care providers, patients, and family members of those under treatment. Since 1992, the Joint Commission, the major accreditation organization of hospitals in the United States, has mandated that health care centers have a mechanism to educate stakeholders and aid in the resolution of ethical dilemmas (Joint Commission 2014). As a result, ethics committees and consultants have become a common part of health care institutions. According to survey data, the percentage of hospitals with ethics committees has risen from 1 % in 1983 to 81 % in 2007 (Youngner et al. 1983; Fox et al. 2007).

With the rise in the prevalence of ethics committees, there are valid questions regarding the appropriate role of these bodies and ethics consultation in general in the resolution of clinical ethical dilemmas. Some of the concerns raised in the ethics literature itself are whether ethics committees possess a specialized knowledge base to address or should have a prescriptive role in resolving clinical ethical quandaries (Rasmussen 2013; Scofield 2012). In addition, there are logistical concerns as how feasibly to ensure all hospitals can have competent ethics consultants, what constitutes competency as well as who should pay for these services (Burda 2011).

What is largely unaddressed is how health care professionals themselves view the role of ethics committees in resolving these challenging situations. This includes questions of whether the ethics committee should have a regular role in addressing ethical dilemmas, whether that role or that of the hospital should be prescriptive in assigning a preferred clinical course when mediation fails and through what framework, if any, most ethical concerns should be approached. These questions are important to ethics consultants and committees, hospitals, health care providers and patients given that a significant portion of the perceived relevance of clinical ethics consultation rests with its ability to address the concerns of those involved with patient care. It is important therefore to assess how those who commonly request ethics support—eg., health care providers—view ethics consultation, its appropriate application and limitations.

Our objective was to use qualitative methodology to thematically examine how health care providers in a variety of professional roles, practice settings and previous experiences or lack thereof with clinical ethics processes view the role of ethics committees and hospitals in the resolution of ethical dilemmas. By identifying these themes, we hoped to provide insight to health care stakeholders and ethics committees as to where there are opportunities for ethics consultation to aid in case resolution as well as the perceived limitations of this process.

Materials and Methods

Theoretical Basis for Separate Qualitative Analysis

We performed a pre-planned secondary qualitative analysis of free-text responses to a case-based survey conducted at six hospitals between December 2013 and March 2014. The purpose of the survey was to present actual case scenarios, modified to protect the anonymity of those involved, from the ethics consult services of these centers to allow the quantitative assessment of the viewpoints of health care professionals on the appropriate role of ethics committees. Using a Likert scale, the survey was developed to allow respondents to:

-

1.

Judge whether ethics committees have a role in addressing clinical ethical dilemmas

-

2.

Explain whether the role of ethics committees or hospitals should be focused upon mediation rather than prescription of a particular case outcome when ethical conflict arises

-

3.

Compare how ethics committee members, ethics consultants and those who previously requested ethics consultation versus those health care providers with no previous involvement with formal ethics processes view case-specific queries and nuances.

However, the quantitative data from the survey provided no thematic explanations for why health care providers took the positions they did on the above issues. With that in mind, we provided survey respondents with the opportunity to give free-text responses to the presented survey cases. We a priori determined to use qualitative methodologies to analyze the free-text responses to evaluate possible thematic explanations for the viewpoints expressed by health care providers on the appropriate role of ethics committees, hospitals and clinical ethics consultation in patient care.

Study Setting

This study took place in a multi-hospital health system located in the United States. The hospitals whose providers were surveyed consisted of six sites ranging from a tertiary care academic medical center which serves as the base for multiple graduate medical education programs to four large community centers with high technical capabilities but limited academic missions to two small community centers with a focus upon high quality provision of standard medical and surgical care to proximate local populations. Each of these hospitals has an ethics committee with varying levels of activity in the areas of ethics consultation and education. The academic center’s ethics committee receives between 50 and 70 ethics consult requests per year and is responsible for the provision of education to health care providers and house staff on clinical ethics. In contrast, the ethics committee of one of the smaller community hospitals meets on an ad hoc basis to consider the approximately 4–5 ethics consult requests per year and has no formal education mission. At the time of this study, the research oversight process at this center was under revision with Institutional Review Board oversight of only six of the seven hospitals in the health care system. As such, we applied for and received IRB approval to conduct the ethics survey in six of the seven hospitals—the tertiary care academic center, three larger community centers and two smaller community centers.

Survey Preparation

To determine what the relevant clinical ethical issues in this health system were, the investigators approached the chairs of the ethics committees at the included hospitals to evaluate the most common and difficult case scenarios encountered. From these discussions, it became apparent that seven thematic ethical dilemmas arose most commonly. These areas included surrogate decision making authority, resolving conflicts on goals of therapy, approaches to caring for intellectually disabled adults (a prominent patient population in this setting), interpretation and application of advance planning documents and actionable medical orders (e.g., Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment), health care provider moral distress, as well as disputes within the treatment team on patient care and futility. While no case-based survey can be comprehensive of all relevant clinical ethical issues, the cases and themes chosen were in congruence with commonly encountered ethical challenges in the larger literature on ethics consultation (American Society for Bioethics and Humanities 2011).

The investigators prepared a survey (Appendix) that drew upon actual cases from the ethics consult services of the included centers modified to protect the privacy of the patients and providers involved. To further evaluate qualitatively the underlying themes that might explain the positions taken by the respondents, we provided an optional place for survey respondents to expound in a free-text manner on their thoughts on the cases presented. We did not make this a mandatory question as we wished to avoid a feeling of obligation in the survey respondents that might lead to rote, rather than consciously insightful, comments.

Survey Respondent Identification and Dissemination

We sought to obtain responses from health care providers in a variety of professional roles, practice settings and experiences or lack thereof with formal ethics processes (e.g., membership on ethics committee, participation in ethics consultation or requesting of ethics consultation). To allow this, we asked the chairs of the ethics committees at included centers for guidance on the relevant clinical roles in their practice settings. For example, at the tertiary care center, we identified the variety of clinical disciplines, graduate medical education programs, nursing expertise (floor versus intensive care unit), other health care professional roles (e.g., pharmacy, physician assistants, nurse practitioners) and other health care support staff (e.g., social workers, case management) that were likely to have insight into the clinical ethical dilemmas included in the survey. We also identified members of the health system legal staff and hospital administration at each site to allow comments from administrative stakeholders in the institutional setting. A similar process occurred prior to survey administration at each of the included study hospitals to identify potential subjects based on their professional role, area of specialty and involvement with ethics committees or consultation in the past.

Survey respondents were asked to provide demographic information and to self-classify their professional role and previous involvement with formal ethics processes as follows:

-

1.

Professional Roles—Attending Physician, Nurse, Resident, Fellow, Legal Staff, Other Healthcare Provider (e.g., Physician Assistant, Nurse Practitioner, Pharmacist), Other Healthcare Organization Staff (e.g., Social Worker, Case Management) or Member of Hospital/Health System Administration.

-

2.

Membership at any time on an Ethics Committee (Yes/No)

-

3.

Served at any time as an Ethics Consultant, a member of an Ethics Consult Subcommittee or Participated in Real-Time Resolution of Clinical Ethical Dilemmas (Yes/No)

-

4.

Requested an Ethics Consult (Yes/No)

The survey was administered to six respondents (three attending physicians, one resident, one nurse and one hospital administrator) from two included centers to validate that we were likely to receive varied, rather than congruent, responses based on the cases survey. Once established, we uploaded the survey to a commercially available electronic survey interface (SurveyMonkey©) to allow electronic distribution.

To obtain a disseminated yet confidentially answered set of survey responses, we approached potential respondents in the previously described clinical roles and practice settings with the guidance of the ethics committee chairs. If a potential respondent agreed to consider participation, we emailed the survey link to that individual. In the survey link email, we also assigned a study categorization number to the respondent that only allowed identification of study facility and professional role category as described above; this number was not unique to any particular respondent. This allowed for assessment of whether we were obtaining study responses from all sites and desired professional roles without compromising subject anonymity. We sought to obtain responses in a ratio proportionate to the relative size of the facilities studied with approximately half of potential respondents approached from the tertiary care center, one-third from the three large community centers and one-sixth from the two small community hospitals. All potential survey respondents received one reminder email to improve the response rate.

Qualitative Methodology

After study completion, two investigators, a medical student and attending physician/principal investigator of this study, initially read through the provided free-text responses to assess whether survey respondents had addressed the cases posed in their comments. The responses were then given to a third investigator, with expertise in qualitative research and not involved with survey construction, to classify them according to professional role and involvement with formal ethics processes. Each free-text response was analyzed as its own unit as our goal was thematic exploration across all study respondents. As described below in the results section, within the constraints of respondent anonymity, we did not find significant differentiation among those individuals who provided free-text responses in thematic exploration based on practice setting or professional role.

Following the tenets of Fereday and Muir-Cochrane (2006) for rigor in qualitative thematic analysis, we employed the iterative and reflexive model of Tobin and Begley (2004) as a way to enhance the standard data-driven approach of Boyatzis (1998). To facilitate this process, the medical student and attending physician investigators independently examined the entire set of responses and generated their own themes. Upon subsequent negotiation and examination through three iterative cycles, these independently generated frames of reference were incorporated into a final set of four basic themes derived from the data. Then the medical investigators independently selected what each of them considered the most representative and insightful responses relating to each theme area. After these selections were made, those responses that were selected by both medical investigators were used as the basic source for the thematic analysis by the qualitative method investigator to identify key quotations from respondents that addressed the theoretical framework above and the explanatory themes that were derived using the qualitative methods previously cited. In all cases, the full responses of the respondents were used to ensure proper contextual grounding.

Results

Characteristics of Survey Respondents and Free-Text Responses

Table 1 shows the characteristics of survey respondents in this study. A total of 240 health care professionals completed the study survey (108 from the tertiary care academic facility, 92 from the three large community hospitals and 40 from the two smaller community centers) with an overall response rate of 63.6 %. We received 307 total free-text responses from the survey respondents (some respondents provided more than one comment to individual cases) with 192 responses from health care professionals with previous involvement with formal ethics processes and 115 from health care professionals with no such previous involvement. There were no quantitative or perceived qualitative differences in the responses chosen for analysis based on practice setting or clinical role. All eight cases elicited a similar number of responses for subsequent qualitative analysis.

Qualitative Analysis Results

Based on the case-based scenarios presented to survey respondents and the iterative and reflexive process described above, the investigators identified two response themes related to the perceived roles of ethics committees and hospitals in aiding in the resolution of clinical ethical dilemmas and two explanatory themes for why respondents might have taken their positions on the appropriate roles of ethics committees and hospitals (Table 2). To aid reader evaluation of the identified themes, we would suggest that reference be made to Appendix, the survey instrument, to read the relevant case scenarios as relates to the responses used below as supportive evidence.

-

1.

The Ethics Committee Does Have a Role in Aiding Health Care Professionals in Resolving Clinical Ethical Dilemmas

Survey respondents in a variety of professional roles and experiences with formal ethics processes stated that ethics committees have a role in aiding health care professionals resolve challenging clinical scenarios, most prominently as an educational and support resource. This was also confirmed in the quantitative data. Mean Likert scale responses supporting ethics committee involvement in the presented cases ranged from 3.64 to 3.79 on a 5 point scale with overlapping 95 % Confidence Intervals across all practice settings. Some examples of responses that reflect this thematic conclusion are:

“I think the ethics committee role is to look at all sides of a situation[,] to educate all sides on the ramifications of any decision and to help balance patient/family autonomy and right [to] choose treatment plans and goals with the need of health teams to not harm a patient and act in the patient’s best interests.” Case 2 – Nurse – No Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“I was always of the opinion that the ethics committee’s role was support and assistance after reviewing case in a neutral position.” Case 3 – Nurse – No Previous Ethics Involvement - Small Community Hospital

“It is OFTEN beneficial for Ethics to mediate/educate staff in a way that facilitates all members of the team to be heard.” Case 6 – Other Healthcare Organization Staff – No Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“The Ethics committee needs to mediate between the son and boyfriend. They should discuss aspects and hopefully come to agreement.” Case 1 – Nurse – Previous Ethics Involvement – Large Community Hospital

“The family needs guidance and expects to receive some. That does not mean that the physician compels the parents to comply. Again, the ethics committee can be viewed as providing impartial input and serving as a mediator to resolve the situation.” Case 3 – Attending Physician – No Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

-

2.

The role of ethics committees and hospitals largely is or should be one of mediation, rather than prescription, in resolving clinical ethical dilemmas. At times, this is a source of healthcare provider frustration, especially as related to ethics committee actions.

As alluded to under the above theme and more explicitly shown below, surveyed health care professionals view the ethics committee and hospitals as having a mediating, rather than prescriptive, role in aiding in the resolution of clinical ethical dilemmas. Respondents, at times, expressed frustration that ethics committees were not authorized to force a particular course of action in some of the cases presented. In contrast, there is an underlying judgment that hospitals should rarely if ever take a prescriptive role in swaying the course of medical therapy. Some examples of responses that support this thematic conclusion are:

“It is not the ethics committee to persuade either party; however, it is their role to help balance the protection of the patient’s autonomy and the liability/responsibility of the oncologist.” Case 2 – Other Healthcare Provider – No Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“I have yet to have an ethics committee ‘choose a side’. I wish they would.” Case 3 – Attending Physician – Previous Ethics Involvement – Small Community Hospital

“It is not the hospital that is managing the patient. The ethics committee should facilitate discussions between all parties involved.” Case 6 – Attending Physician – No Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“I don’t [think or believe] it is the role of either party [ethics committee or hospital] to persuade. Their role should be to explain and help the other parties understand and make recommendations and as long as the choices of those autonomous parties are within reasonable medical practice then those decisions can be acted upon.” Case 2 – Resident – Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“The hospital can’t practice medicine- only the doctor can.” Case 8 – Attending – Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

-

3.

Health care professionals often view the resolution of ethical dilemmas through the prism of legal provisions with an underlying fear that not following what is perceived to be legally mandated may lead to medico-legal exposure and consequences. This sometimes comes at the expense of professional ethical viewpoints.

The survey respondents, in expressing their thoughts on how the presented ethical case dilemmas might be resolved, regularly delineated a tension between their perceptions of legal requirements in comparison to their own professional ethical viewpoints. The health care professionals presumed that perceived legal mandates would trump ethical concerns. Associated with this presumption was a further theme of moral distress, where health care professionals were frustrated by the perceived necessity to follow a legally mandated course at the expense of what they viewed as ethically normative. This was common to both individuals with and without previous ethics involvement. Some example quotations that provide evidence for this theme are as follows:

“Ethically, the boyfriend knows her best and should be allowed precedence over the son. Legally, I believe the son has the power here…whether that is right or wrong is another story. Yet another reason why law and medicine shouldn’t tread on each other’s ground. Sort of like separation of Church and State.” Case 1 – Resident – Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“It is unfortunate that the Institution official has the rights over family but I understand that this is currently the law. My experience with a similar situation has been dismal.” Case 4 – Attending – Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“Unfortunately, whether true or not, the assumption would be [that] the physician would be legally at fault for not following the legal guardian. The fear of litigation would direct the course of care.” Case 6 – Attending – Previous Ethics Involvement – Small Community Hospital

“The surgeons should pursue surgery and then extubate[,] and if [the patient] doesn’t do well[,] limit measures. The surgeon in this case could be liable if [he or she] doesn’t do surgery and that isn’t fair to them. Again medico legal trumps common sense.” Case 5 – Other Healthcare Organization Staff – Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“Legally we (health professional[s]) are supposed to follow the hierarchy, but personally I would believe more in the boyfriend who has known the patient better than the estranged son.” Case 1 – Attending – Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“Although we do not have an obligation to offer futile care, I think most clinicians in this situation would follow the family’s unreasonable wishes on fear of litigation.” Case 2 – Fellow – No Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“A decision must be made eventually; I don’t feel hospital or physician can make this decision so legal action will eventually have to be made.” Case 3 – Nurse – No Previous Ethics Involvement – Large Community Hospital

-

4.

Given the moral distress experienced by health care professionals when confronted by cases such as those presented, ethics committees should attempt to reconcile legal and ethical tensions. Health care professionals care more about this act of reconciliation than a theoretical moral framework through which to resolve the dilemma.

Survey respondents did not emphasize a desire for ethics committees to expound at length on moral or philosophical frameworks for resolving the clinical ethics cases presented. Instead, health care professionals focused most clearly on the theme that ethics committees should use their mediation role to facilitate a pragmatic reconciliation that allows a path forward in clinical care. This reconciliation should give voice to the concerns of clinicians and patients while allowing the avoidance of medico-legal consequences. Some example quotations that support this thematic conclusion include:

“The disagreement between the health care professionals is not a factor. The daughter is the legal decision maker. The ethics committee should continue to play the role of mediator/councilor as long as the daughter struggles with the decision but if she has clearly and thoughtfully decided[,] her wishes and directions should be heeded by the attending physician.” Case 7 – Nurse – No Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“The Ethics committee needs to mediate between the son and boyfriend. They should discuss aspects and hopefully come to agreement. Legally the son is the decision maker but the boyfriend is probably best able to identify the patient’s wishes.” Case 1 – Nurse – Previous Ethics Involvement – Large Community Hospital

“It is always appropriate for the physician to give his/her recommendation. The family needs guidance and expects to receive some. That does not mean that the physician compels the parents to comply. Again, the ethics committee can be viewed as providing impartial input and serving as a mediator to resolve the situation. Having to pursue legal remedy is a no-win situation for all involved.” Case 3 – Attending – No Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“Every effort must be made to educate and counsel the legally appointed guardian, and if said guardian is deemed to be making decisions that are not in the best interest of the patient, then perhaps the court could be petitioned to provide a different or additional guardian.” Case 6 – Nurse – No Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

“If the attending oncologist thinks it is futile effort to continue chemotherapy at this time, [the] Ethics committee should support this decision and convince the family of this decision.” Case 2 – Attending - Previous Ethics Involvement – Tertiary Care Facility

Discussion

In this multi-center survey study of health care professionals, we identified four themes that both clarify and explain how clinicians and other staff view the role of ethics committees and hospitals in the resolution of clinical ethical dilemmas. Survey respondents confirmed that ethics committees can aid in resolving these situations and that the mechanism for doing this is by mediation, rather than prescription, of a particular course. This supports the published core competencies on clinical ethics consultation which emphasizes a cooperative and facilitative process in resolving ethical dilemmas (American Society for Bioethics and Humanities 2011).

However, our survey data elucidates two further explanatory themes that suggest an underlying tension with the current mediation model in ethics consultation. First, health care professionals presume that legal proscriptions or regulations are the ultimate authority in resolving these difficult cases. This is a source of frustration and moral distress. As one of the respondents eloquently stated in reference to Case 5, “The surgeon in this case could be liable if [he or she] doesn’t do surgery and that isn’t fair to them. Again medico legal trumps common sense.” Similar quotations elicited from the presented cases show an undercurrent of medico-legal fear as a prism through which health care professionals approach clinical ethics cases. This raises the question of whether clinicians view ethics consultation as less a mechanism for positive resolution of difficult situations as much as a tool for avoiding medico-legal conflict with patients and their surrogate decision makers. One might go further to state that there exists a further subtext of ethical passivity among clinicians in this survey population. The above quotations show a consistent finding that as much as health care professionals have strong personal and professional ethical views on the clinical ethics case presented, they sometimes subordinate those opinions to legal exigencies that they assume are more authoritative.

In this context, this qualitative analysis suggests that ethics committees should focus on mediation in a manner that provides a pathway that resolves both professional moral distress and avoids medico-legal exposure. The latter may more expertly be performed by hospital legal departments; after all, most ethics consultants and committee members are not lawyers. However, ethics mediation can clearly facilitate clinicians verbalizing their concerns to patients about the course of therapy. This verbalization and consideration may be important in resolving moral distress by allowing all parties to feel that their concerns have been evaluated in the context of patient care. Such facilitation falls within the published core competencies of ethics consultation (American Society for Bioethics and Humanities 2011). Our data suggests that facilitated communication is far more valued by health care professionals in ethics consultation along with knowledge of legal and hospital regulations rather than a particular philosophical or moral framework that can be brought to bear in resolving clinical ethical dilemmas. In essence, health care professionals want a pragmatic, perhaps casuistry-based approach from ethics consultants, based on the qualitative survey data presented here.

There are three potential implications to this conclusion. First, while ethics committee members should have knowledge of moral and philosophical theories that underlie health care ethics, their practical education should perhaps predominantly focus upon communication skills and the regulatory environment in which they work. This has implications for the implementation of core competencies in ethics consultation in training and credentialing of ethics consultants (American Society for Bioethics and Humanities 2011). It may be necessary for training programs to focus more prominently on pragmatic mediation and legal particulars to ensure that consultants are prepared for the questions likely to arise in the clinical environment.

Second, to interface with the real-world concerns that clinicians have when encountering ethical dilemmas such as those presented, it is necessary for ethics consultants to have detailed knowledge of the clinical nuances of the cases in which they are called. If “good facts make good ethics” (Venkat 2012), then there is a fundamental obligation for effective consultation to include an assessment of what practical clinical alternatives exist that are both ethically and medico-legally available. This cannot be done in the abstract, but rather requires a robust interface with the clinical world. Again, from an educational perspective, some knowledge of pathophysiology, therapeutic alternatives and judging prognosis should be incorporated into training programs on ethics consultation. This would allow ethics consultants and committees to be effective in meeting the expectations of health care professionals who call for their services. The most practical way to do this is to ensure multi-disciplinary representation on ethics committees from which clinical expertise can be drawn. The themes presented in this study provide evidence that clinicians want an interface that can improve communication among all parties to an ethical dilemma. To do this, medical knowledge would seem to be a prerequisite.

Finally, the emphasis on legalities seen in our qualitative data raises the question as to whether ethics committees or consultants should ever recommend a course of care that would raise the likelihood of medico-legal conflict. The elicited quotations do not preclude this possibility as many of them discuss the need to go to court if necessary to reach a resolution. However, that is significantly resource-intensive and impractical in most cases. Instead, we would suggest that ethics committee members and consultants utilize our data in noting that their recommendations may lead to medico-legal consequences such as judicial resolution on surrogate decision making authority, for example. Since our data shows that these recommendations are likely to be unsurprising to health care professionals, it may allow ethics committees to present a series of options that fit within this context and perhaps emphasize case resolution pathways that include mediation as a means to avoid legal pathways to conflict resolution. That seems to be the practical conclusion of our second explanatory theme that ethics committees should act in a manner that ideally leads to reconciliation and avoids medico-legal conflict except as a last resort.

While our study has the strengths of surveying healthcare professionals in a variety of practice settings, professional roles and previous experience with ethics consultation, there are limitations. First, our study was conducted in one geographic region and in institutions under an overarching health care system that is based in this area. This may skew the views of the health care professionals surveyed, and we would urge other health care systems to validate our findings. Second, while the cases presented range over topics commonly encountered by ethics committees, they are not all-encompassing. It is possible that other topics might provide additional themes of relevance to how health care professionals view the role of ethics committees and hospitals in resolving ethical dilemmas. Finally, we did not conduct follow-up interviews with survey respondents predominantly for practical reasons, given the number of respondents in a variety of locations and practice settings, and there is the potential for bias with pre-identification of potential respondents. However, the topical breadth and number of responses received provides a robust set of qualitative data providing validation to the themes we have identified. In addition, we have attempted to limit the potential for selection bias in subject responses by both attempting to obtain a disseminated sample from varied professional roles as well as allowing anonymity in refusal to respond to the survey. We also note that the relative even distribution of responses across all eight cases supports that the themes identified in this study are not unique to particular areas of ethical concern.

In conclusion, this multi-center survey of health care professionals revealed qualitative themes that ethics committees and hospitals have roles in resolving clinical ethical dilemmas and that the role most expected is one of mediation rather than prescription. However, most health care professionals anticipated that legal regulations were most authoritative in resolving these cases and that ethics committees should attempt to reconcile parties involved in a manner that addresses professional moral distress and, if at all possible, avoids medico-legal consequences. Our findings have implications for how ethics committees and consultants are trained and what types of recommendations they can make that appropriately serve health care professionals and their patients.

References

American Society for Bioethics and Humanities. (2011). Core competencies for healthcare ethics consultation (2nd ed.). IL: Chicago.

Boyatzis, R. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Burda, M. (2011). Certifying clinical ethics consultants: Who pays? Journal of Clinical Ethics, 22(2), 194–199.

Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92.

Fox, E., Myers, S., & Pearlman, R. (2007). Ethics consultation in United States hospitals: A national survey. American Journal of Bioethics, 7(2), 13–25.

Rasmussen, L. (2013). The chiaroscuro of accountability in the second edition of the Core Competencies for Healthcare Ethics Consultation. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 24(1), 32–40.

Scofield, G. R. (2012). Ethics been very good to us. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 23(2), 165–168.

Tobin, G., & Begley, C. (2004). Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48(4), 388–396.

Venkat, A. (2012). Surrogate medical decision making on behalf of the never competent, profoundly intellectually disabled patient who is acutely ill. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 23(1), 71–78.

Youngner, S. J., Jackson, D. L., Coulton, C., Juknialis, B. W., & Smith, E. M. (1983). A national survey of hospital ethics committees. Critical Care Medicine, 11(11), 902–905.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Survey Instrument

Appendix: Survey Instrument

Case Questionnaire

Instructions

You will be presented a series of vignettes based on actual cases from within Allegheny Health Network hospitals, modified to protect the anonymity of the individuals involved. The purpose of this survey is to ascertain your views as a member of the health care team or hospital staff with regard to the issues presented. You are requested to circle the degree to which you agree or disagree with the statements following the cases and will be given the opportunity to add your own free-text impressions or opinions.

Cases

-

1.

Estranged Family as Surrogate Decision Maker

AB is a 79-year-old female recently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. She has been living with her boyfriend for the past 5 years and is largely estranged from her family. Yesterday, she fell and was brought to the hospital unconscious. AB does not have a living will or health care power-of-attorney document, and the hospital social worker reaches out to family to identify whether other surrogate decision makers exist. The social worker is able to contact a son who has not seen the patient in 10 years, but is the only surviving close family member. In the hospital, the patient has developed secondary complications, including pneumonia and septic shock, requiring intubation and pressors via central venous access. The boyfriend feels strongly that AB wouldn’t want to undergo these painful procedures, but the son is demanding that everything must be done for his mother. The attending physician speaks to the boyfriend and son, but is unable to bring them to agreement.

1 (Strongly Disagree)—3 (Neutral)—5 (Strongly Agree)—Please circle your response for each question.

-

(1)

The ethics committee has a role in resolving this dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(2)

The ethics committee should choose a side, rather than just mediate the dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(3)

The legal status of the potential surrogate decision makers, rather than their overall familiarity with the patient, should govern which path to follow if they are not able to come to a consensus decision. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(4)

Free Response from Surveyed Subject.

-

2.

Dealing with Family Expectations

BL is a 64-year-old male diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer. The attending oncologist believes that there is a 15 % chance of 5-year survival with aggressive chemo-and radiation therapy and a 40 % chance of 1-year survival with palliative care measures. The oncologist asks BL to consult with his family and make a decision. The patient and family decide to go with aggressive treatment because BL is a ‘fighter.’ The patient does well for about a week, but then the course doesn’t go well; BL develops complications with resultant need to delay continued cycles of chemo- and radiation therapy. After a few weeks the attending oncologist believes nothing else of a curative nature can be done and that they should move to palliative care. BL and his family refuse to switch to palliative care saying that he was doing better and maybe he would again. The attending oncologist explains slowly and clearly that while he was initially doing better, the treatment course was unsuccessful. The patient and family disagree with his comments and want another round of chemo- and radiation therapy. They believe that another round will cure him and that the hospital should provide treatment in line with the patient’s wishes.

1 (Strongly Disagree)—3 (Neutral)—5 (Strongly Agree)—Please circle your response

-

(1)

The ethics committee has a role in resolving this dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(2)

As long as the therapeutic option is within the spectrum of reasonable medical practice, the attending oncologist should defer to patient wishes on therapeutic options. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(3)

It is the role of the attending oncologist to persuade the patient and family to agree upon a course of treatment. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(4)

It is the role of the ethics committee to persuade either the attending oncologist or the patient/family to pursue a particular course of therapy. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(5)

Free Response from Surveyed Subject

-

3.

Conflict Among Surrogate Decision Makers

RA is a 17-year-old female patient who presents to the hospital unconscious after a motor vehicle accident. RA is unresponsive for several days, but is not showing progression to brain death. After a couple of weeks, it seems that RA will likely require long-term life support and has minimal to no rehabilitation potential. The hospital asks her parents whether they would prefer her to undergo tracheostomy and gastrostomy for long-term life-sustaining treatment or whether they would prefer life-sustaining treatment to be withdrawn. The mother and father both have raised RA since birth and are devastated by having to make this decision. The mother wants to withdraw life sustaining treatment; the father wants long-term life-sustaining treatment. Both say they know their daughter’s wishes. The attending physician explains that a decision must be made one way or the other to avoid complications related to long-term intubation, temporary nutritional support via nasal feeding tube and exposure to infectious complications through long-term ICU care. The mother and father cannot come to an agreement.

1 (Strongly Disagree)—3 (Neutral)—5 (Strongly Agree)—Please circle your response

-

(1)

The ethics committee has a role in resolving this dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(2)

After all mediation efforts have been tried, it is appropriate for the attending physician to choose a side in this dispute to resolve the situation at the bedside level. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(3)

After all mediation efforts have been tried, it is appropriate for the ethics committee to choose a side in this dispute to resolve the situation at the bedside level. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(4)

After all mediation efforts have been tried, it is appropriate for the hospital to pursue a legal remedy (court order) to resolve this dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(5)

Free Response from Surveyed Subject

-

4.

Patients With Intellectual Disability Requiring Institutionalized Care

JC is a 54-year-old male with Down’s Syndrome. He has been living in an institutionalized care setting since late adolescence. JC has done well within this setting but over the past few years has developed signs of early-onset dementia, a common occurrence in Down’s Syndrome patients. His family wishes to initiate do-not-resuscitate status and not pursue aggressive therapy if JC develops an acute or degenerative illness. During a series of examinations, JC’s physician diagnoses him with metastatic melanoma. The oncologist believes that with palliative measures JC will live for 1 year. With chemotherapy, the expected likelihood of 5-year survival is 40 %. The family believes that JC should not receive chemotherapy and should instead be placed in hospice care. The leadership of the institutionalized care setting disagrees, stating that there is a reasonable chance of patient recovery or life prolongation. The leadership of the residential institution states that they are required by law to pursue life-sustaining therapy for their residents and that if the family wishes to not pursue this therapy, JC will need to leave their care. The family doesn’t want aggressive treatment, but would have difficulty with caring for JC outside of institutionalized care.

1 (Strongly Disagree)—3 (Neutral)—5 (Strongly Agree)—Please circle your response

-

(1)

The ethics committee has a role in resolving this dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(2)

The leadership of the institutionalized care setting should have a role in determining the course of therapy in JC. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(3)

The family of JC should have the ultimate decision making authority for JC’s care. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(4)

It is the role of the ethics committee to choose a side, as opposed to mediating, in this dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(5)

It is the role of the hospital to choose a side, as opposed to mediating, in this dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(6)

Free Response from Surveyed Subject

-

5.

POLST

DP is a 54-year-old male patient with end-stage renal disease, poor overall functional status and requires long-term nursing home care. He is transported to the hospital following a fall at his facility. Upon arrival, the treating physicians note a large contusion on the patient’s head, an increased level of confusion from baseline and subsequently diagnose a subdural hematoma. The patient has a POLST form which calls for do-not-resuscitate status and limited additional interventions. However, the patient has a condition that requires acute surgical treatment for him to have any hope of recovery, and to perform this surgery, the patient would require intubation and subsequent clinical care. The patient is too confused to ask his interpretation of the POLST form he previously signed, and there are no available surrogate decision makers.

1 (Strongly Disagree)—3 (Neutral)—5 (Strongly Agree)—Please circle your response

-

(1)

The ethics committee has a role in resolving this dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(2)

Ethics consultation can provide an appropriate recommendation under time pressured circumstances such as in this case and should be available at all hours. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(3)

The treating physicians should default to full surgical treatment in this circumstance. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(4)

The do-not-resuscitate status of the patient should not apply during the patient’s surgery if that course is pursued, 1 2 3 4 5

-

(5)

Free Response from Surveyed Subject

-

6.

Moral Distress

RJ is a 40-year-old female who suffered a respiratory arrest following an overdose of prescribed antidepressant medications. She has been hospitalized for 3 months with multiple complications, including episodes of septic shock, GI bleeds and seizures. She has no close family members and instead has a court-appointed guardian. This guardian has elected to continue aggressive therapy despite the patient’s poor prognosis. The attending physician has reconciled herself to this course of therapy, though she agrees the patient’s prognosis is poor. However, the nurses involved with the patient’s care have a deep ambivalence in continuing this treatment plan.

1 (Strongly Disagree)—3 (Neutral)—5 (Strongly Agree)—Please circle your response

-

(1)

The ethics committee has a role in resolving this dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(2)

The ethics committee should perform a consult in this case based on the nursing request, even if the attending physician does not feel this is necessary. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(3)

The legal authority of the court appointed guardian should cause the entire treatment team to continue the current aggressive medical management. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(4)

The hospital should facilitate the recusal of any treatment team member who voices objections to the current treatment plan. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(5)

The hospital has an obligation to continue managing this patient with full life-sustaining treatments. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(6)

Free Response from Surveyed Subject

-

7.

Conflict within Healthcare Team

KN is a 77-year-old male who is diagnosed with colon cancer that can be treated surgically. The patient has early dementia and his daughter serves as his surrogate decision maker. The daughter elects for surgery, but after surgery, the patient cannot be extubated and requires pressor support. Three days post-operatively, the patient’s daughter requests that life-sustaining treatment be withdrawn, stating that her father would never want this level of aggressive care. The surgeon feels this is premature while the critical care consultant is unsure of the patient’s prognosis, but has no objection to the daughter’s request.

1 (Strongly Disagree)—3 (Neutral)—5 (Strongly Agree)—Please circle your response

-

(1)

The ethics committee has a role in resolving this dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(2)

Assuming that the parties cannot agree on a course of treatment, the ethics committee should choose a side rather than simply mediate a consensus solution. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(3)

The fact that there is disagreement among the health care professionals on prognosis should result in the daughter’s request being followed. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(4)

Free Response from Surveyed Subject.

-

8.

Futility

DK is a 90-year-old female with end-stage dementia who has been hospitalized recurrently with urinary tract infections and septic shock. She has no close family members, but has a long-standing primary care physician. The physician states that the patient never wanted limitations in her treatment options, even with the onset of dementia. During this hospitalization, the patient has developed c. difficile related diarrhea, an infected decubitus ulcer and appears in pain during turning and position transfers in bed. When this is brought to the primary care physician’s attention, he states that he will treat the patient’s symptoms, but still believes that treating the patient as “full code” is what is in line with the patient’s previously stated wishes.

1 (Strongly Disagree)—3 (Neutral)—5 (Strongly Agree)—Please circle your response

-

(1)

The ethics committee has a role in resolving this dispute. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(2)

The ethics committee should advocate for palliative care measures for this patient despite the stated views of the patient’s primary care physician. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(3)

If the ethics committee is in agreement, it is appropriate for the hospital to limit further aggressive care measures, such as intubation or central line placement for pressors, if the patient’s condition deteriorates. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(4)

If the ethics committee is in agreement, it is appropriate for the hospital to declare ongoing attempts at curative treatment futile and force the treating primary care physician to initiate palliative care measures. 1 2 3 4 5

-

(5)

Free Response from Surveyed Subject

Demographic Questionnaire

Study Categorization Number (Please enter number provided in email request to participate in study) NOTE—This number is only used to evaluate the facility and distribution of the responses:

Gender:

-

1.

Male

-

2.

Female

Subject Age:

-

1.

18–30

-

2.

31–40

-

3.

41–50

-

4.

51–60

-

5.

61+

Ethnicity:

-

1.

Hispanic or Latino

-

2.

Not Hispanic or Latino

-

3.

Choose Not to Answer

Race:

-

1.

Caucasian

-

2.

African-American

-

3.

American Indian/Native American

-

4.

Asian-Pacific Islander

-

5.

Other/Mixed Race

-

6.

Choose Not to Answer

Religion:

-

1.

None

-

2.

Christian (Church of England, Catholic, Protestant and all other Christian denominations)

-

3.

Buddhist

-

4.

Hindu

-

5.

Jewish

-

6.

Muslim

-

7.

Sikh

-

8.

Other

-

9.

Choose Not to Answer

Highest Level of Education:

-

1.

High school

-

2.

Some undergraduate

-

3.

Undergraduate

-

4.

Some post-graduate

-

5.

Master’s

-

6.

Professional (medical) degree (MD, Pharm.D, MSN)

-

7.

PhD

Role within healthcare organization (may choose more than one):

-

1.

Attending Physician

-

2.

Nurse

-

3.

Resident

-

4.

Fellow

-

5.

Legal Staff

-

6.

Other Healthcare Provider (e.g., nurse practitioner, PA, pharmacist, nutritionist)

-

7.

Other Healthcare Organization Staff (e.g., Social Worker, Case Management)

-

8.

Member of Hospital or Health System Administration (e.g., VP, CMO)

Are you currently or have you ever been a hospital ethics committee member:

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No

Do you now or have you ever served as a clinical ethics consultant, participated on a clinical ethics consult subcommittee or directly participated in the resolution of a clinical ethics consult in real time?

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No

Have you previously requested a clinical ethics consult?

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No

Primary Practice or Employment Location:

-

8.

Tertiary Care, Academic Center

-

9.

Large Community Hospital 1

-

10.

Large Community Hospital 2

-

11.

Small Community Hospital 1

-

12.

Small Community Hospital 2

-

13.

Large Community Hospital 3

-

14.

Health System Administration—Multiple Sites

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marcus, B.S., Shank, G., Carlson, J.N. et al. Qualitative Analysis of Healthcare Professionals’ Viewpoints on the Role of Ethics Committees and Hospitals in the Resolution of Clinical Ethical Dilemmas. HEC Forum 27, 11–34 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-014-9258-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-014-9258-0