Abstract

Most studies on the spatial determinants of radical voting adopt a purely contemporary approach, suggesting that the current characteristics of one’s geographical environment (most notably diversity and economic deprivation) largely determine the propensity to vote for a radical party. While this approach has led to new insights, in the current paper we also investigate whether there is a historical pattern with regard the spatial determinants of radical voting. Theoretically, this would suggest there is at least some form of continuity between the ‘tribalist’ voting of the 1930s (Popper, The open society and its enemies, Routledge, London, 1945), and the current wave of populist voting. In this results in the region. Our analysis, however, does not show any significant correlation between both results at the level of the small electoral districts. We do find more support for some level of historical continuity between communist electoral scores and left populist voting, than for the same relation on the radical right side of the electoral spectrum, and we close by offering some speculation on causes for this lack of continuity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is a well-known phenomenon that electoral results follow established geographical patterns, as political parties typically have their stronghold in specific cities and regions (Goguel, 1951; Johnston & Pattie, 2006). Although some studies have documented a ‘nationalization’ of electoral politics, i.e., a trend toward the occurrence of uniform electoral results across an entire country or political system (Caramani, 2004), in practice countries are far from politically homogeneous (Russo, 2014). Research in the United States even suggests that the country is becoming increasingly polarized across geographical lines, partly because partisans tend to relocate to regions where their preferred party has established an electoral advantage (Johnston et al., 2020; Miller & Conover, 2015; Shelley, 2022). It is striking to observe, however, that efforts to explain the geographical spread of specific party support tend to start from contemporary spatial determinants. A routine assumption is indeed that the current characteristics of a region determine the electoral strength of a specific political party during elections (Biswas, 2023; Cutts et al., 2020; Furlong, 2019; Lenzi & Perucca, 2021). While we certainly do not wish to question the important insights gained from this approach in the literature, it has to be noted that a strong historical path dependency should be taken into account, too (Flint, 2000). Various studies have shown that historical divisions continue to have an impact on current electoral results (Grabowski, 2019; Zagórski & Markowski, 2021). These historical determinants suggest a pattern of path dependency: once a political party has gained a stronghold in a specific region, it is more likely that this party and its candidates will continue to concentrate campaign efforts on this region. Voters, therefore, are more likely to continue to support this party, even when the original cleavage structure that initially gave rise to this first party success, might have disappeared already a long time ago.

One of the most sweeping changes in electoral politics in Europe during the last decades has been the rise of radical-right and populist parties (Rooduijn, 2018). In various countries, these parties have gained substantial support among public opinion, with programs based on nativism, distrust toward the political elite, and anti-immigrant sentiments (Lindholm & Rapeli, 2023). We know already a great deal about the individual-level determinants of radical-right voting, while there is also some research on the spatial determinants of this voting pattern, with an emphasis on the presence of ethnic minorities in the region (Arzheimer, 2009; Jambrina-Canseco, 2023; Ford & Goodwin, 2010; Rydgren and Ruth, 2013; Stiers & Hooghe, 2022).

Most of these studies, however, use the current characteristics of a region in order to explain the success of radical-right parties, and at first sight this seems a straightforward research design. In the theoretical literature there is indeed a tendency to see populist parties as a ‘new’ phenomenon, that combines a number of unique ideological features (Rydgren, 2018). Furthermore, most radical-right parties were founded in the recent past, so there is no obvious organizational continuity for these parties. Nevertheless, some studies already suggested a relation with historical demographic patterns: radical-right parties seem to have their electoral strongholds in those regions where there are more returnees from the former colonies, even when these have already settled several decades ago (Veugelers, 2020). Especially in Germany, some research has shown a pattern of persistence between the voting pattern in the 1930s and the current basis of electoral support for extreme-right voting (Cantoni et al., 2018; Pepinsky et al., 2023). While the original structural circumstances that might have given rise to an extreme right party have disappeared a long time ago, apparently there are still conditions that are conducive to an extreme right vote in those specific regions. As far as we now, however, this kind of analysis has not yet been conducted in other countries.

Theoretically, however, this is an interesting research question, because it allows us to determine to what extent the current wave of challenger parties actually can be considered as a totally new and unique phenomenon or whether there is at least some form of historical continuity with older right-wing authoritarian movements and parties. To a large extent, the nativism that is crucial to the current radical-right ideology is close to the ‘tribalism’ that was identified as a key identifying element of the authoritarian movements of the 1930s (Popper, 1945). According to Popper, tribalism should be conceptualized as a longing for strong leadership in a closed society, without any internal divisions or strong influences from outside the community. When we do observe a geographical pattern of historical continuity, this would be a reasonable argument to challenge the alleged ideological ‘novelty’ of this party family.

One of the reasons for this lack of research is that it poses a clear challenge to develop a coherent research design. Not only do we need access to current geographical data on the success of radical right parties, we also need comparable historical data, and furthermore there is also a need for a predecessor party that can clearly be identified, and that had some form of electoral success in the pre-war period. The time gap, too, needs to be sufficiently large so we can be certain that is not the same voters that are being counted in these elections as this would suggest an individual level pattern of continuity, and not an aggregate level effect. For the specific situation of the Flemish region of Belgium, all these conditions are fulfilled, and that is why we will focus on this region for the empirical analysis in the remainder of this paper. The region has had a successful radical-right party since the 1990s, while there was also a strong presence of authoritarian challenger parties in the 1930s (De Wever, 2007; Van Holsteyn, 2018). More specifically, we will investigate whether, even controlling for contemporary spatial determinants of an extreme right vote, we still find a pattern of historical continuity in the aggregate level results of these parties. Furthermore, we will investigate to what extent the same aggregate level variables (i.e., labour market structure, unemployment and diversity) can help us to explain the electoral score of extreme parties.

Equally important, however, is that radical left political parties have also been active in the region. In the political science literature, there is less attention for the rise of radical left than for the rise of radical left parties, but theoretically both sides of the political spectrum are equally relevant. Both for radical right as for radical left, it can be assumed that these parties function as challenger parties, that question and potentially disrupt the political status quo. With regard to voting motives too, this suggests that these voters have in common a form of discontent, and this might be one of the reasons their electoral scores are geographically concentrated (Hutter & Borbáth, 2019). More importantly, by comparing radical right and radical left parties, we obtain a more robust research design, with as a result we can be more confident that our results are not just the artifact of a rather unique single party. If we turn to our specific case, it can be observed that the Flemish region of Belgium also has a rather successful radical left political party. In fact, both in the 1930s as in the early party of the twenty-first century, various authors used the expression ‘the rise of the extremes’, to include both the radical right as the radical left (De Wever, 1994). The elections of 1936 were highly successful for the Belgian Communist Party, in the slipstream of the victory of the Front Populaire in France a few weeks earlier. Up until the 1980s the Communist Party gained seats in Parliament, and shortly after the end of World War II it even briefly participated in a coalition government (Gotovitch, 2012). While the Communist Party was abolished after it lost electoral appeal, its place at the extreme left side of the spectrum was taken by the ‘Labour Party’, that started from an orthodox Maoist inspiration, but rather successfully transformed itself into a left wing populist party (Delwit, 2016). This phenomenon allows us to investigate the historical continuities of radical voting, both on the right as on the left side of the political spectrum. The presence of successful radical right and radical left political parties, both in 1936 as in 2019, offer the ideal setting to investigate spatial patterns of radical voting, both at the radical right as on the radical left side of the political spectrum. While there is an abundance of research on radical right voting, it can be observed that thus far there is not all that much research available on the determinants of radical left voting (Marcos-Marne, 2021), so this obviously constitutes an important contribution to our knowledge of radical voting patterns.

The Belgian case

Belgium offers an interesting case to investigate the geographical and historical determinants of radical voting, first because the country has one of the oldest and most successful extreme-right parties in Europe: the ‘Flemish Interest’, or Vlaams Belang (Erk, 2005; Sijstermans, 2021). The party can be considered as a typical exponent of this specific party family, with an emphasis on the consequences of immigration, security and diversity issues. In the 2019 general elections in Belgium, the party obtained 18.5% from the vote in the Flemish region of Belgium. Furthermore, during those elections, we can observe a high degree of local variation in support for that party, ranging from 8.36 per cent in the university town of Leuven, to 33.49 in the former industrial town of Ninove. Self-evidently, individual level variation can explain a substantial part of these observed differences, but it does remain theoretically relevant to investigate the spatial determinants of the Vlaams Belang vote.

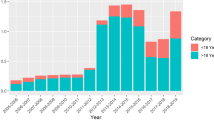

Furthermore, in the Belgian case there is also a historical precedent, as the country had quite active extreme-right political parties in the 1930s (Conway, 1996). The May 1936 elections led to the highest ever score for extreme-right parties in Belgium, as ‘Rex’ obtained 11.5, and the Flemish National Alliance (VNV) obtained 7.1 per cent of the vote. It has to be noted that both parties were competitors: while they shared a common extreme right ideology, they did split on the linguistic divide in Belgium. Rex originally was a French-speaking party, subsequently spreading out its activities to the Dutch-speaking part of the country, and it advocated a model of Belgian unity. After the German invasion of May 1940, Rex actively collaborated with the Nazi occupation force, and its leader was sentenced to death because he joined the German army (Conway, 1993). On the Flemish side, the Flemish National Alliance was in favour of an authoritarian political regime, but it also favoured a stronger autonomy for the Flemish region, against the Belgian unitary state. The VNV also collaborated intensively with the German occupation force after 1940 and several of its local mayors very actively participated in the persecution of the Jewish population in Belgium (De Wever, 1994; Gérard-Libois & Gotovitch, 1971; Vanden Daelen, 2019). It has to be noted that there is no strict organizational continuity from a historical perspective: after the end of World War II both parties were banned, and several of their leaders were prosecuted for active collaboration with the enemy. Only four decades later, in 1978, a new extreme-right political party was founded, the ‘Vlaams Blok’, that had its first major electoral success during the 1991 general elections (Breuning & Ishiyama, 1998). The 2019 elections, however, meant a real breakthrough for the Vlaams Belang that became the second party in the region of Flanders.

It could be argued, however, that we investigate mainly ‘radical’ voting, and that the pattern we find is not typical for ‘radical-right’ voting. As a robustness analysis, therefore, we will conduct exactly the same analysis but this time focusing on the radical-left vote, taking the Communist Party in 1936, and the extreme-left Labour Party in 2019 as examples. Again, there is no organizational continuity, as the Communist Party lost its last seats in Parliament in 1985, and completely ceased to exist in 2009. The current Labour Party only gained its first parliamentary seats in the Flemish region in 2019, obtaining 5.3 per cent of the vote.

If our goal is to compare the 1936 and the 2019 elections, the risk of a personal overlap is negligible, as in the whole of Belgium, there are only 1487 inhabitants above the age of 100 (and who were therefore eligible to vote in 1936), and it can be assumed that not all of them physically turned out to vote in 2019. Therefore we can be quite confident that it is not the same individuals that did take part in both the 1936 and the 2019 elections. If we would find any pattern on continuity, this has to be situated at the aggregate level, not at the individual level.

It is important to point out that Belgium is a federal country, with two linguistically segregated party systems. The Dutch language parties only compete in the Dutch-language region of Flanders, while the French-language parties only compete in the French-language region of Wallonia (Hooghe & Stiers, 2022).Footnote 1 In the Walloon region of the country, there is no viable radical-right party, while in Flanders the radical-right party is present since 1978, reaching up to 24 per cent of the vote (De Jonge, 2021). During those last four decades, the electoral profile of the ‘Vlaams Belang’ (the new name of the Vlaams Blok) has remained relatively unchanged, recruiting mainly lowly-educated voters with a high level of anti-immigrant sentiments (Deschouwer, 2018). Therefore, this analysis will remained limited to the Flemish region of Belgium, with some six million inhabitants, or more than half of the total Belgian population.

More specifically we will analyze election results at the level of the canton, which is the smallest geographical unit that is available for both the historical as the current elections. In 2019, the region of Flanders was divided in 103 cantons, which means that on average a canton has ca. 40,500 votes.Footnote 2 It is important to note that the canton is a purely administrative unit, that is solely used for the organization of the fieldwork of the elections. Cantons are not used to assign seats in the elections, as this happens on the much larger level of the electoral circumscriptions (five of them in Flanders, so on average there are 21 cantons in a circumscription). As such, candidate lists are the same all over the circumscription, so there is no obvious reason to assume the presence of candidates would have a specific effect on the canton level. The goal of a canton is not to offer a sense of geographical unity, as it typically consists of a major population center, and all the surrounding more rural areas. As the purpose of the cantons is purely administrative, it is a safe guess that most voters will not even be aware of the canton they are part of. For the purpose of the analysis, the main conclusion is that the canton is an ‘empty’ unit of spatial aggregation, with no specific characteristics with regard to district magnitude, popular candidates, or other possible intervening variables. For some analyses, however, the data are not available on the level of the ‘canton’, but only on the level of the larger ‘arrondissement’. Currently, the 300 municipalities in Flanders are grouped into 103 cantons and subsequently 22 arrondissements.

The most interesting feature for our purpose, however, is that the geographical boundaries of most of the cantons did not change all that much during the past century. When population figures rose substantially, some cantons have been split up, while some of the cantons near Brussels also changed their borders to allow for the complicated process of regionalization in Belgian politics. For 88 of the 103 cantons, however, not all that much changed, so this unit of observation can be used both for historical as for current election results. More specifically, we will compare the 1936 and the 2019 election results. These elections were selected because they represent a historical turning point for extreme political parties. In 1936, the extreme-right parties obtained their highest scores for this period (De Wever, 1992), and for the Vlaams Belang, this was repeated in 2019. For the Communists in 1936, and the Labour Party in 2019, these elections too were highly successful, leading to their highest ever scores.

For the analysis, we use official election results as they are gathered by the Belgian Ministry of the Interior. In total we can perform the historical analysis for 88 of the 103 current electoral cantons. A few adjustments were necessary to make this comparison possible. For three cantons in the province of East Flanders, recent municipal mergers implied the construction of larger cantons for the 2019 elections. For these three cantons we were able to reconstruct results for the 1936 elections, so we have the same observation unit in all three cases. In other cases, there is a direct historical continuity, but with some minor corrections as small rural municipalities were transferred from one canton to another. Mostly this had to do with municipal mergers, or with the fact that historically some population centers became more important. These were all smaller municipalities with just a few thousand inhabitants, as obviously the center cities of the canton always remain the same.

As in previous research, the challenge for this comparison is to be able to match the pre-war electoral circumscriptions with the current ones, and it has to be noted that in this regard, Belgium offers a high degree of stability. The system of arrondissements and cantons, as it was established when the current territory became part of France in 1795 basically has not changed all that much. The changes between 1936 and 2019 are limited, and find their origin in a distinct number of administrative motives. First, the country was linguistically segregated in 1963, in a Dutch, a French, a German speaking and a bilingual area. As the goal was to implement a very strict linguistic separation, this meant that some cantons were split up, so that they all fully belonged to just one language region. On the level of the arrondissements, there is just one major change, in that the bilingual area of the capital Brussels was separated from the Dutch language suburbs of Halle/Vilvoorde that surround the capital. All other arrondissements kept the same borders. Second, smaller municipalities were merged in 1976. In a vast majority of cases these mergers were conducted within the existing canton boundaries, so they did not change the functioning of this unit. In those cases where did this not happen, canton lines were changed to adjust to the new situation as a municipality obviously can only belong to one canton. Mostly this implied that very small rural former municipalities were moved from one canton to another, with a limited impact on the number of inhabitants involved. Third, the major cities of Antwerp, Ghent and Brussels continued to expand, incorporating in some instances suburbs that were previously the seat of a canton. As obviously the canton seat has to be a full and autonomous municipality, this meant that either these cantons were discontinued or merged into a canton seat further from the main city. Finally, there are also two cases were a smaller regional center gradually became more important over the decades, and was successful in establishing its own canton. This, however, only happened twice: with the municipalities of Aalter in East Flanders (that doubled its population during the twentieth century) and Genk in Limburg (that became a successful mining city, with a population that grew 20-fold). All these changes leave us with 88 cantons where the borders did not change substantially between 1936 and 2019.

Methods

To obtain a first view on the possible spatial continuity of radical voting, we first present a set of electoral maps of the Flemish Region in order to observe the strongholds of the radical parties in the 1936 and 2019 elections respectively. We subsequently estimate regression models explaining radical voting in each of the years under investigation separately, to test whether commonly identified measures such as unemployment levels and level of diversity explain radical voting (Gordon, 2018; Stiers & Hooghe, 2022). It has to be noted that, before the Second World War, Belgium did not have a system of universal unemployment protection, so that unemployment figures for the 1930s are still based only on registered workers (Vanthemsche, 1989: 105–152). Most likely, therefore the unemployment rates of the 1930s are an underestimate, but it has to be noted that this was a period of a rather deep economic crisis in the country (Baudhuin, 1946). However, as the same legislation was applied over the entire territory of the country, it is still possible to compare the different geographical units within Belgium. Diversity is measured as the percentage of non-EU citizens living in the canton (Stiers & Hooghe, 2022). For 1936 we use the percentage of non-Belgians in the total population. For both elections, we also include information about the basic economic structure, by including the percentage of the total labour force that is employed in industry. This allows us to assess whether industrial areas are more prone to be characterized by a radical electoral preference. We also include a control for district magnitude by including the number of valid votes cast.Footnote 3 The challenge for this research design was to find reliable economic and population data for 1936. We did find these data from the official Belgian statistics office; however, they were not collected at the level of cantons, but at the level of the larger arrondissements. Therefore, in these analyses, we explain radical voting on the arrondissement level. In a last step, and most central for our research question, we regress vote shares of the radical parties in 2019 on vote shares of these parties in 1936, again on the canton level. We also include control variables measured at this level in 2019. In this way, the models reveal whether historical continuities add to explaining support for radical parties in addition to the already known determinants of radical voting.

Results

First we look at electoral results at the level of the canton for the elections of both 1936 and 2019 (Fig. 1). In the Figure, darker shades represent higher electoral scores for the radical right party in resp. 1936 and 2019. While there are obvious differences, it is also clear that there are some regions (notably in the Eastern and Western parts of the region) where radical right parties obtain a high score in both elections. It has to be noted that these parties do not seem to obtain their highest scores in the major urban regions, that also have the highest level of cultural and ethnic diversity.

Source: Ministry of the Interior. White areas represent cantons that could not be reconstructed based on historical data; the white area in the bottom middle is Brussels. The letters indicate the main cities: B (Bruges), G (Ghent), A (Antwerp), L (Leuven), and H (Hasselt)

Scores for radical right parties in 1936 and 2019 (VNV and Vlaams Belang), Flemish Region of Belgium.

Subsequently we repeat the some exercise for radical left voting, where we compare the score of 1936 and 2019. We can observe that the radical left political parties obtain their highest scores in the urban areas of Antwerp, Ghent and Brussels, while their scores are much weaker in the more rural areas in the western part of the region (Fig. 2).

Source: Ministry of the Interior. White areas represent cantons that could not be reconstructed based on historical data; the white area in the bottom middle is Brussels. The letters indicate the main cities: B (Bruges), G (Ghent), A (Antwerp), L (Leuven), and H (Hasselt)

Radical left voting in 1936 and 2019.

While this representation might provide us with some guidance on historical continuity, more can be learned from further models explaining support for these radical parties. Therefore, first, we estimate OLS models predicting the vote share for the radical right and radical left respectively, in 1936 and 2019 respectively. As explained above, these analyses are on the level of the arrondissements, as only on this level the macro-economic data are available. The results are summarized in Table 1.

The results in Table 1 show that our variables do not add to explaining radical voting in 2019. Surprisingly, we do not find a significant association between the level of diversity and support for the radical-right Vlaams Belang in the 2019 elections, which has been reported in earlier research on the geographical determinants of radical-right voting (Evans & Ivaldi, 2021). The radical right party tends to perform better in industrial areas, or to express it differently: it scores less well in arrondissement that are dominated by employment in government and the service sector. We do find a positive association between unemployment levels and support for the radical left party in 2019. The radical left party indeed scores quite well in the former industrial regions, where some of the heavy industry has disappeared in recent decades. For the radical left, the structure of the labour market does not have an effect. Looking at the results for 1936, however, none of our variables of interest explain support for these radical parties. The radical right party performed less well in industrial areas in 1936, while in 2019 this relation is inversed. We further observe that the radical right VNV scored, on average, lower in larger districts, while the larger cities seem to be a stronghold for radical left voting both in 1936 and in 2019.

Our main interest, however, is to investigate historical continuities in radical voting. We therefore estimate another set of models with the 2019 election results as the dependent variable, and the electoral results at the level of the cantons as observation unit. As the labour market statistics of the 1930’s are only available on the larger aggregate level of the arrondissement, these data could not be included in this analysis on the level of the canton. Our initial assumption that there also might be a connection between the 1936 Rex vote and the Vlaams Belang score proved not to be the case, as obviously the Rex party started from a very francophone-dominated vision on the future of Belgium, which seems completely at odds with the Flemish nationalist framework of the Vlaams Belang. Therefore, we focus only on the 1936 score of the VNV. The results for this party are summarized in Table 2.

In the first model, it can be observed that the relation between the electoral score in 1936 and the score in 2019 is only borderline significant (p = 0.08). We cannot assume, therefore, that there would be a strong historical continuity between both elections. In the subsequent models 2 and 3, we control for ethnic diversity and unemployment in 2019, and both correlate negatively with the electoral score of the Vlaams Belang in 2019. However, when including these variables simultaneously, the effects are rendered non-significant. In a final model 5, we also control for the magnitude of the electoral canton, but this does not change the results of the analysis. The results of this regression analysis, therefore, do not suggest a strong historical continuity between radical right voting in the 1930s, and in the most recent elections in the country. Obviously, in this case, Belgium does not follow the pattern as it was established for radical right voting in Germany.

When we turn to the radical left side of the political spectrum, we can observe that at the aggregate level the correlation between the 1936 and the 2019 election results is stronger for radical left parties than it was for radical right parties (Table 3). To a large extent this is in line with what we know about communist voting: in both elections, these parties were virtually absent in rural and agricultural areas, while they obtained their best scores in more industrialized areas. It has to be noted in this regard that the largest metropolitan areas are in fact missing from our analysis, as especially in Brussels, Antwerp and Ghent, the cantons changed so dramatically that we cannot include them in a 1936–2019 comparison. For the 1930s, this indeed confirms the traditional research on the determinants of electoral support for radical left parties (Dupeux, 1959). From an ideological point of view, this is quite a surprising finding as throughout the 1960s and 1970s there was an intense rivalry between the Communist Party and the Labour Party. While the Communist Party adhered to a rather orthodox Marxist point of view, and has closed ties to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and its allies, the Labour Party, on the other hand, rather reflected the ideological vision of the People’s Republic of China. Despite these fierce ideological debates among extreme left political groups, both parties tend to share the same electoral strongholds. From a theoretical perspective, this is a relevant finding. There is some research available about the electoral support of radical left parties in the current era in Europa (Katsambekis and Kiopkiolis, 2019). However, most of these studies focus on political parties that do not have any historical continuity with Marxism (Font et al., 2021). The Belgian example, however, suggests that when there is a radical left political party that is still related to traditional Marxist debates, there is also a historical continuity with regard to electoral support. Radical left parties typically fare well in areas with a strong presence of ethnic minorities. This suggests that, both for radical right as for radical left political parties, there is at least some merit in investigating spatial patterns of historical continuity.

Discussion

In recent years, there have been numerous studies on spatial determinants of radical voting, which is routinely considered as a phenomenon that could endanger the long-term stability of liberal democratic systems. Most of these studies conceptualize radical parties as a recently new phenomenon, by investigating the effect of ethnic and cultural diversity, a hostile attitude toward political elites, or a protest against the consequences of economic globalization. Available research indeed shows that these considerations are significantly related to a vote for radical parties, and we do not wish to question these findings.

In this paper, however, our goal was to investigate to what extent there are also historical determinants of a radical vote. Back in the 1930s the functioning of liberal democracy was equally challenged by radical groups, both on the right as on the left side of the political spectrum. Popper (1945) famously stated that these authoritarian movements should be seen as a manifestation of ‘tribalism’, a concept that is remarkably close to the contemporary definition of populism and nativism.

The current analysis, however, did not show any significant historical continuities with regard to the electoral support basis of the authoritarian parties of the 1930’s, and the electoral success of radical parties in 2019, which is more than eight decades later. The radical right parties of the 1930s, and the party of 2019, clearly do not have the same geographical basis of electoral support. To some degree this supports the ‘nationalisation’ thesis of Caramani (2004). In the 1930s the strongholds for the VNV clearly corresponded to the presence of a well-known politician of that party (De Wever, 1994). In 2019, this pattern is totally absent, and in the regions where the Vlaams Belang scores best, the party in fact has no well-known candidates. This would suggest that the electoral score of the party is no longer dependent on any local politician but can be explained by other forms of political communication, like the mass media (Jambrina-Canseco, 2023).

There was some indication for continuity, however, for radical left parties, where indeed the 1936 communist strongholds continued to vote strongly for a radical left party in 2019. There might be a number of possible explanations for this pattern. First, the radical left party has its stronghold in the main industrial areas with a strong working-class presence, and a strong presence of labour unions. These areas are also the ones that are most likely to attract labour immigration. While there are some examples of communist parties performing quite well in rural areas (Boswell, 1998), this spatial pattern obviously is not present in Belgium. Second, the radical left political parties also have a distinct ideology that stresses international solidarity. In fact, studies show that the radical left parties actively recruit political candidates with an immigrant background (Celis et al., 2013). Ethnic voting patterns, therefore, might explain why this party is seen as attractive for voters in more diverse areas. This suggests a clear difference in the electoral recruitment pattern of extreme left and extreme right political parties. The extreme left political parties continue to have an urban, industrialized and culturally diverse stronghold, and they are virtually absent in the rural areas of the region. The extreme right political party, on the other hand, has continued its scope and obtains its highest score in regions that are culturally homogeneous. While we started our analysis with the hypothesis there would some form of historical and geographical continuity, this proved to be only the case for the radical left political party, not for the radical right political party.

As this is a single-country study, we cannot determine in a precise manner how to explain this pattern, but some elements stand out. First, it has to be noted that in Belgium, like in most other countries that were occupied by Nazi–Germany during the period 1939–1945, the radical right parties that had collaborated with the Nazis were abolished and their leaders were punished or at least removed from public life (Huyse & Dhondt, 2020). The same pattern was followed in other countries (Bergère et al., 2019), so that at least on the level of political leaders and parties, there cannot be any form of historical continuity. On the radical left side, on the other hand, this legal intervention did not take place and the communist parties of the 1930’s could easily continue into the 1950’s (Costalli & Ruggeri, 2019). Although this requires further research, this historical pattern does not suggest that the Belgian results would be exceptional in any way.

A second important element is that is seems clear from the current results that the radical right party has successfully spread outside its original strongholds, and now is clearly present across the territory. This phenomenon has also been documented in other studies on, e.g., Sweden, France, Belgium and Spain (Evans & Ivaldi, 2021; Ortega et al., 2022; Rydgren & Ruth, 2013; Stiers & Hooghe, 2022). These findings strongly suggest that the radical right parties are no longer limited by their initial pattern of spatial diffusion, and this might explain the lack of historical continuity. These two elements are not only present in Belgium but also in various other countries, and might point to a more general pattern. Whether or not the findings from this study on Belgium can be generalized to other cases too, however, needs to be further investigated.

Notes

These two regions include ca. 90% of the Belgian population. For the time being we leave aside the bilingual region of the capital Brussels, and the much smaller German-language region in the east of the country.

There are also five smaller ‘virtual’ cantons, that are used to group the votes of Belgian voting from abroad. These cantons are not included in the current analysis as they do not correspond to any real territory, and together only account for 7588 votes, which is about 0.2 per cent of all votes in the region.

Turning out to vote is compulsory in Belgium (both in 1936 as in 2019), and turnout rates are stable at ca. 90%.

References

Arzheimer, K. (2009). Contextual factors and the extreme right vote in western Europe, 1980–2002. American Journal of Political Science, 53(2), 259–275.

Baudhuin, F. (1946). Histoire économique de la Belgique, 1914–1939. Bruylant.

Bergère, M., et al. (Eds.). (2019). Pour une histoire connectée et transnationale des Épurations en Europe après 1945. Peter Lang.

Biswas, F. (2023). Electoral patterns and voting behavior of Bihar in assembly elections from 2010 to 2020. A spatial analysis. GeoJournal, 88(1), 655–689.

Boswell, L. (1998). Rural communism in France, 1920–1939. Cornell University Press.

Breuning, M., & Ishiyama, J. (1998). The rhetoric of nationalism: Rhetorical strategies of the Volksunie and Vlaams Blok in Belgium, 1991–1995. Political Communication, 15(1), 5–26.

Cantoni, D., Hagemeister, F., & Westcott, M. (2018). Voting for the far right in Germany. In D. Marin (Ed.), Explaining Germany’s exceptional recovery (pp. 107–112). CEPR Press.

Caramani, D. (2004). The nationalization of politics. Cambridge University Press.

Celis, K., Eelbode, F., & Wauters, B. (2013). Visible ethnic minorities in local political parties. A case study of two Belgian cities (Antwerp and Ghent). Politics, 33(3), 160–171.

Conway, M. (1993). Collaboration in Belgium: Léon Degrelle and the rexist movement 1940–1944. Yale University Press.

Conway, M. (1996). The Extreme right in inter-war francophone Belgium: Explanations of a failure. European History Quarterly, 26(2), 267–292.

Costalli, S., & Ruggeri, A. (2019). The long-term electoral legacies of civil war in young democracies: Italy, 1946–1968. Comparative Political Studies, 52(6), 927–961.

Cutts, D., Goodwin, M., Heath, O., & Surridge, P. (2020). Brexit, the 2019 general election and the realignment of British politics. Political Quarterly, 91(1), 7–23.

De Jonge, L. (2021). The curious case of Belgium: Why is there no right-wing populism in Wallonia? Government and Opposition, 56(4), 598–614.

De Wever, B. (1992). De Vlaams-nationalisten in de parlementsverkiezingen van 1936. Belgisch Tijdschrift Voor Nieuwste Geschiedenis, 23(3–4), 281–353.

De Wever, B. (1994). Greep naar de macht: Vlaams-nationalisme en nieuwe orde: Het VNV 1933–1945. Lannoo.

De Wever, B. (2007). Catholicism and fascism in Belgium. Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, 8(2), 343–352.

Delwit, P. (2016). PTB: Nouvelle gauche vieille recette. Luc Pire.

Deschouwer, K. (Ed.). (2018). Mind the gap. Political participation and representation in Belgium. ECPR Press.

Dupeux, G. (1959). Le front populaire et les élections de 1936. Armand Colin.

Erk, J. (2005). From Vlaams Blok to Vlaams Belang: The Belgian far-right renames itself. West European Politics, 28(3), 493–502.

Evans, J., & Ivaldi, G. (2021). Contextual effects of immigrant presence on populist radical right support: Testing the “halo effect” on front national voting in France. Government & Opposition, 54(5), 823–854.

Flint, C. (2000). Electoral geography and the social construction of space. The example of the Nazi party in Baden, 1924–1932. GeoJournal, 51(1), 145–156.

Font, N., Graziano, P., & Tsakatika, M. (2021). Varieties of inclusionary populism? Syriza, podemos and the five star movement. Government and Opposition, 56(1), 163–183.

Ford, R., & Goodwin, M. (2010). Angry white men: Individual and contextual predictors of support for the British National Party. Political Studies, 58(1), 1–25.

Furlong, J. (2019). The changing electoral geography of England and Wales: Varieties of “left-behindedness.” Political Geography, 75, 102061.

Gérard-Libois, J., & Gotovitch, J. (1971). L’an 40. La Belgique occupée. CRISP.

Goguel, F. (1951). Géographie des élections françaises de 1870 à 1951. Armand Colin.

Gordon, I. (2018). In what sense left behind by globalisation? Looking for a less reductionist geography of the populist surge in Europe. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 95–113.

Gotovitch, J. (2012). Du communisme et des communistes en Belgique. Aden.

Grabowski, W. (2019). Determinants of voting results in Poland in the 2015 parliamentary elections. Analysis of spatial differences. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 52(4), 331–342.

Hooghe, M., & Stiers, D. (2022). A tale of two regions: An analysis of two decades of Belgian public opinion. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 52(4), 655–674.

Hutter, S., & Borbáth, E. (2019). Challenges from left and right. The long-term dynamics of protest and electoral politics in western Europe. European Societies, 21(4), 487–512.

Huyse, L., & Dhondt, S. (2020). Onverwerkt verleden. Kritak.

Jambrina-Canseco, B. (2023). The stories we tell ourselves. Local newspaper reporting and support for the radical right. Political Geography, 100, 102778.

Johnston, R., Manley, D., Jones, K., & Rohla, R. (2020). The geographical polarization of the American electorate. A country of increasing electoral landslides? GeoJournal, 85, 187–204.

Johnston, R., & Pattie, C. (2006). Putting voters in their place. Geography and elections in great Britain. Oxford University Press.

Katsambekis, G., & Kiopkiolis, A. (Eds.). (2019). The populist radical left in Europe. Routledge.

Lenzi, C., & Perucca, G. (2021). People or places that don’t matter? Individual and contextual determinants of the geography of discontent. Economic Geography, 97(5), 415–444.

Lindholm, A., & Rapeli, L. (2023). Is the unhappy citizen a populist citizen? Linking subjective well-being to populist and nativist attitudes. European Political Science Review (in Press). https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000583

Marcos-Marne, H. (2021). A tale of populism? The determinants of voting for left-wing populist parties in Spain. Political Studies, 69(4), 1053–1071.

Miller, P., & Conover, P. (2015). Red and blue states of mind: Partisan hostility and voting in the United States. Political Research Quarterly, 68(2), 225–239.

Ortega, C., Trujillo, J. M., & Oñate, P. (2022). El surgimiento de la derecha radical en España. La explicación del voto a Vox en las elecciones andaluzas de 2018. Revista de Estudios Regionales, 124, 127–156.

Pepinsky, T., Goodman, S. & Ziller, C. (2023). Modeling spatial heterogeneity and historical persistence. Nazi concentration camps and contemporary intolerance. American Political Science Review, (in Press). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055423000072

Popper, K. R. (1945). The open society and its enemies. Routledge.

Rooduijn, M. (2018). What unites the voter bases of populist parties? Comparing the electorates of 15 populist parties. European Political Science Review, 10(3), 351–368.

Russo, L. (2014). The nationalization of electoral change in a geographical perspective. The case of Italy (2006–2008). GeoJournal, 79, 73–87.

Rydgren, J. (Ed.). (2018). The Oxford handbook of the radical right. Oxford University Press.

Rydgren, J., & Ruth, P. (2013). Contextual explanations of radical right-wing support in Sweden. Socioeconomic marginalization, group threat, and the halo effect. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(4), 711–728.

Shelley, F. (2022). The deeping rural–urban divide in US presidential politics. Presidential votes in Iowa, 2008–2020. Political Geography, 93, 102515.

Sijstermans, J. (2021). The Vlaams Belang. A mass party of the 21st century. Politics and Governance, 9(4), 275–285.

Stiers, D., & Hooghe, M. (2022). Ethnic diversity, anti-immigrant sentiments, and radical right voting in the Flemish region of Belgium. Swiss Political Science Review, 28(3), 496–515.

Van Holsteyn, J. (2018). The radical right in Belgium and the Netherlands. In J. Rydgren (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the radical right (pp. 478–504). Oxford University Press.

VandenDaelen, V. (2019). Living together in the “Yidishe Gas”: The case of Antwerp. Journal of Genocide Research, 21(3), 436–455.

Vanthemsche, Guy. (1989). De werkloosheid in België, 1929–1940. EPO.

Veugelers, J. (2020). Empire’s legacy. Roots of a far-right affinity in contemporary France. Oxford University Press.

Zagórski, P., & Markowski, R. (2021). Persistent legacies of the empires partition of Poland and Turnout. East European Politics and Societies and Cultures, 35(2), 336–362.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Greet Louw for her impeccable data collection, and Dr. Stiers thanks the Fund for Scientific Research FWO for generous funding.

Funding

Funding was provided by FWO Belgium

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to this manuscript. MH was mainly responsible for providing historical background, while DS was mainly responsible for analysis of the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest whatsoever.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hooghe, M., Stiers, D. Are there historical continuities in the geographical spread of radical voting? A comparison of the 1936 and 2019 election results in the Flemish region of Belgium. GeoJournal 88, 5743–5755 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-023-10936-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-023-10936-0