Abstract

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the regional disparities of multidimensional poverty (MPI) in the context of India. This study to our knowledge is the first of its kind which examined MPI disparity at a regional level. The study has classified the geographic area of India into six regions: Northern, Eastern, North Eastern, Central, Western and Southern region. Further, we explore MPI across population sub-groups within a region. Using the latest available household data from the National Family and Health Survey over 2005–2006 and 2015–2016 we explored how at the regional level multidimensional poverty changed within a decade. The paper estimates MPI in India at a regional level following the methodology of Alkire and Foster (2011). The Eastern rural region has the highest MPI 0.43 (2005–2006) and 0.21 (2015–2016). The lowest MPI is in the Northern region 0.14 and 0.03 respectively. The Northern region further has lowest MPI across all social sub-groups. The results also demonstrate regional concentration of MPI particularly in the Central and Eastern regions. A major disquieting feature is that the regional variation in MPI across the Eastern and the Northern region increased by four times in 2015–2016 compared to the earlier period. The study further obtains that though multidimensional poverty has reduced significantly over the decade the decline is regressive. It can be traced to the nature of regressivity in the decline in the different deprivation indicators. The present study suggests that India must endeavour the process of balanced regional development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

India has made noteworthy progress as far as its growth trajectory is concerned, particularly in the recent decade, (World Bank, 2018). However, the growth performance of the Indian subcontinent is exclusionary and non-inclusive. This has exacerbated the regional disparities, rural–urban divide, social and gender-based inequalities, (Dev, 2010). Further, at the backdrop of global integration and liberalization policies adopted by the government, India has suffered a phenomenal rise in spatial inequality owing to the better-performing regions taking the advantage of the turn in market movement (Mukhopadhyay & Garcés, 2018; Gajwani, et al. 2007; and Kanbur & Venables, 2007). Even after seven decades post-independence, the Indian government face the challenges of governance owing to rising inter-regional poverty and income disparity which are not explicit at aggregative levels. The study on multidimensional poverty and deprivations at the regional level of a huge country like India is of utmost importance. Following the pioneering initial theoretical contribution of Atkinson and Bourguignon (1982), Bourguignon and Chakravarty (2003) and later the important theoretical and empirical contributions of Alkire and Foster (2011), Alkire, and Seth (2015), Alkire et al. (2015), Sydunnaher et al. (2019), Das et al. (2021) and Alkire et al. (2021), the extant seam of literature on both the theoretical and empirical applications on multidimensional poverty has expanded rapidly. The research by Alkire and Foster (2011) led to the publication of the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) for more than a set of 100 countries, which is the special case of the Alkire-Foster class of measures.

This paper revisits the measurement of multidimensional poverty in the Indian context following the methodology of Alkire and Foster (2011), Alkire et al. (2015); Das et al. (2021); and Alkire et al. (2021). This study is the first of its kind to our knowledge which examines multidimensional poverty disparity at a regional level in India, further decomposing the population by social and religious groups. A growing number of studies explored the dynamics of multidimensional poverty. Studies are rather scant that investigates the dynamics of multidimensional poverty at a regional level for developing countries in general and India in particular. In the context of disparity in developing countries, Sydunnaher et al. (2019) and Deinne and Ajayi (2019) discuss that multidimensional poverty measure should be applied at a disaggregated level to explore the severity of poverty across geographical units. In India economic growth has been spectacular for the last two decades but socio-economic development has not been coherent with India’s high growth performance. Regional disparities are a disquieting feature in India despite policy initiatives by the government of India for inclusive growth and development. Large sections of Indian society do not have access to basic services such as health, education, housing and clean drinking water. The studies by Dholakia (1985), Das and Barua (1996) and Ohlan (2013) discussed that over the years regional disparities in India increased at an alarming rate and India’s policy perspectives needs to address these issues. This paper thus makes a novel contribution to understanding the recent picture of multidimensional poverty across the major regions of India.

The contribution of the paper is threefold. First, we empirically measure multidimensional poverty using the multidimensional index, following Alkire and Foster (2011) across the major regions of India. The study has classified the geographic area of India into six regionsFootnote 1: (1) Northern Region which includes the states of Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh; (2) Eastern region which includes the states of West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha and Jharkhand; (3) North Eastern region including the states of Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura, Assam and Meghalaya; (4) Central region which includes the states of Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh; (5) Western region which includes the states of Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Gujarat and Goa and (6) Southern region which includes the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. We have explored the intensity of deprivation expressed through multidimensional measure for the different regions in India. The results show that MPI was highest in the Eastern region for both the years 2005–2006 (0.372) and 2015–2016 (0.179). The Northern region has the lowest MPI for both the years. The Central and Eastern regions of India continue to have the highest concentration of regional poverty. There appears to be a perceptible decline in the MPI. However, the decline is regressive. The regressive nature of decline in MPI can be attributed to the regressive nature of decline in the multidimensional head count ratio and intensity of poor. Second, we have used the multi-dimensional poverty measure to examine poverty reduction trends in India over 2005–2006 and 2015–2016 across regions and sub-groups of population. Empirically thus this paper contributes to the seam of analysis by examining how multidimensional poverty reduced in India across regions and religious and social sub-groups of population within a region. We have classified the households into three groups based on the levels of deprivation as multidimensionally non-poor, ordinary multidimensional poor and severely multidimensional poor following the UNDP methodology (2010 and 2019). Third, to delve further upon the nature of inter-regional disparities, the paper develops a logistic regression model to explore the determinants of multidimensional poverty at the household level in the major six regions. We particularly examined how the household size, levels of education of the head household, age of the head of the household, the socio-religious group and the regional variation impact multidimensional poverty. The results based on the household analysis brings to the forefront the micro-factors determining MPI which are concealed in the aggregate analysis.

The paper henceforth is designed as follows: "Review of literature" section reviews the recent findings in the literature related to the measurement and dynamics of multidimensional poverty; "Methodology" section outlines the data, methodology for the multidimensional poverty measure and its properties; "Deprivation across indicators in different regions of India" section discuss the regional variation of deprivation across indicators and how they are important in explaining multidimensional poverty across the major regions of India; "Status of multidimensional poverty across regions of India" section discuss the status of multidimensional poverty across the regions decomposed further by headcount and intensity of poor; "MPI by population subgroups in different regions of India" section explores the MPI across the regions of India decomposed by population subgroups; "Degree of multidimensional poverty across regions of India" section explains the changes in the degree of multidimensional poverty across the regions of India; "Analysis of determinants of multidimensional poverty" section analyses the determinants of the degree of multidimensional poverty at the household level in relation to regional disparity; "Discussion" section presents the major discussion. Finally, "Conclusion and policy discussions" section concludes.

Review of literature

Poverty or deprivation in wellbeing can be measured through indicators covering monetary and non-monetary aspects. The monetary-based poverty estimates captured through the income poverty line undoubtedly throws important insights on poverty nevertheless it has certain shortcomings, (Bourguignon & Chakravarty, 2003 and Alkire & Santos, 2010). The limitations on the measurement of poverty based on monetary metrics stressed the need to develop the multidimensional poverty. The MPI is developed first by the OPHI, the University of Oxford which includes poverty across various dimensions. Wide-ranging literature discusses the importance of multidimensional poverty measure using varying indicators depending upon the perceptions of poverty, for example, Alkire (2002), Alkire and Foster (2011), Whelan et al. (2012), Santos (2014), Tripathi and Yenneti (2020), Khan and Hafidi (2021) and Das et al. (2021). However, the literature discussing MPI in the Indian context continues to be scant particularly in the regional context. The study by Sundaram and Tendulkar (1995) explored housing deprivations in rural and urban India for its major states for the year 1991. Based on the overcrowding indicators the shelter deprivation index was 13.41 for rural India and 8.27 for urban India. The study by Bhatty (1998) discussed educational deprivation in the context of India based on field survey investigation. The study found that rather than parental motivation the main obstacle to educational access is the costs of schooling and this indeed is the major explanatory factor for educational deprivation. The study by Alkire and Seth (2008) using 2002 below poverty line methodology based on the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data instead of using the below poverty line census data obtained that up to 33 per cent of the extreme poor are wrongly classified as non-poor by the below poverty line methodology. The study also developed the sample deprivation index and compared the results at a disaggregate level. Based on unit-level data of the NFHS, Mohanty (2011) measured multidimensional poverty and found that the child survival rate is linked with multidimensional poverty in India. The paper concluded that infant mortality and under-five mortality rates are extremely high among the population with abject multidimensional poverty compared to the non-poor. Using National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) data, Sarkar (2012) developed a multidimensional poverty index based on the following indicators—highest educational attainment of the members of the household, mean per capita expenditure, calorie intake, availability of electricity and type of cooking fuel used. The study concluded that based on the NSSO data rural poverty in India has declined over time. Poverty continues to be the highest among the socially vulnerable groups. The study by Mishra and Ray (2013) using NFHS data and NSSO data made a wide-ranging analysis of the living standards of the Indian population over the periods 1992–93 and 2004–2005. The study was conducted at a regional level and disaggregated further by socio-economic groups. The study concluded that the decomposable dimensions of poverty deprivation explained the vulnerability across the socio-economic groups compared to the levels of total deprivation. Alkire and Seth (2015) using NFHS data over 1996 and 2006 showed that though poverty levels have declined in India, the reduction is not identical across all the social indicators. Furthermore, the study discussed that the decline in poverty among the poorer sub-groups has been rather slow which has increased the income disparity across the population. The study by Tripathi and Yenneti (2020) using NSSO data on consumption expenditure explored the multidimensional poverty levels across the states of India based on the standard of living indicator, educational indicator and income level of the households. The results show a decline in multidimensional poverty in 2004–2005 from 62.2 per cent to 38.4 per cent in 2011–2012. Alkire, et al. (2021) explored how the levels of poverty have declined over 2005–2006 and 2015–2016 in India and across social groups. The paper also examined how steadily poverty declined across the poorest among the poor. Das et al. (2021) discussed the extent of poverty in India by exploring the consumption-based deprivation and multidimensional poverty for the period 2004–2005 and 2011–2012 using NSSO data. The study showed a significant reduction in multidimensional poverty and consumption poverty however the reduction is not identical across various sub-groups of the Indian population. The study concluded that there is a growing need in India to measure consumption poverty and multidimensional poverty, particularly for policy purposes. Table 1 provides the summary of findings in the recent literature of different dimensions of data source used and on the choice of indicators in the context of measurement of MPI in India.

From the findings of Table 1 we obtain that major data source used to explore the Indian MPI included NFHS; IHDS and NSSO. The authors have used varying time points based on the availability of the data. The majority of the studies have used health, educational, nutritional and asset indicators to measure MPI. While given the scope of the data sets another strand in the literature has explained the levels of MPI through the patterns and changes in consumption expenditure. However, the research on the regional dimension and across population sub groups is scant. This study addresses this major gap in the extant literature. The current study addresses the health, educational and standard of living indicators of MPI in an integrated framework. Further owing to the availability of data the period of observations is for 2005–2006 and 2015–2016 respectively. Such explorations throw insights into the shape of things across the timeline. The regional level study is important in the context of a largely dispersed country like India. Interestingly the present research endeavours along such direction. Using the Alkire and Foster (2011) methodology the present study scrutinizes the situation of multidimensional poverty for six major regions of India based on ten indicators grouped into three dimensions: health, education, and standard of living.

Methodology

Measurement of multidimensional poverty

The measure of multidimensional poverty index (MPI) essentially is based on the Alkire and Foster (2011) class of poverty measures. This study following the study by Alkire and Foster (2011) has developed the MPI where the household is the unit of observation. It has selected a set of indicators across which the deprivation is measured (Table 2), following Alkire and Foster (2021). Further a set of deprivation cut- offs has been denoted and a deprivation matrix is generated. This attaches a score to each unit of observation namely the household in each dimension. It takes the value of 1 if the household is deprived and 0 otherwise. Using a vector of weights wj (in percentage terms) that sum to 100, the weighted deprivation score \({c}_{i}\) is obtained, Eq. (1)Footnote 2 If the deprivation score exceeds the poverty cut-off denoted by k then they are indicated as multidimensionally poor.

The measures of multidimensional poverty for the entire population corresponding to the household-specific weights (Wi) and size of the household (hi) are given as follows, following the Alkire and Foster methodology (Alkire et al. 2015; and Das et al. 2021):

The aggregate deprivation score of the i-th household (ci) is given by

where dij is the status of deprivation of i-th household in j-th indicator which takes value 1 if the household is deprived in respect of deprivation cut-off and 0 otherwise, wj is the weight (in percentage term) of indicator j \(\left( {where \sum w_{j} = 100} \right)\). And hence ci lies between 0 and 100. Higher the ci, greater is the degree of deprivation of the household and vice-versa. Multidimensional poor are identified based on the threshold value of the weighted deprivation score c(k) = 33.33 (Alkire & Santos, 2010; Alkire & Seth, 2015; UNDP, 2010, 2015, and 2019).

Multidimensional Headcount Ratio (H) is the ratio of multidimensionally poor people to the total population. In percentage form, it is expressed as

where, q is the number of multidimensional poor households and n is the total number of households.

Intensity of Multidimensional Poverty (A) reflects the average deprivation score of the multidimensional poor people. In percentage form, it is expressed as

Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) is the ratio of aggregate deprivation score of multidimensional poor people to total population.

Hence, MPI is the product of multidimensional headcount ratio and intensity of poverty. This MPI is robustFootnote 3 as by altering the multidimensional poverty cut-offs (c(k)), the poverty ranks do not change, explained in detail in the result section.

Total population constituted with hi and Wi can be decomposed as

where nl is the number of households for r-th region, where l = 1, 2, …. m. The number multidimensional poor households in r-th region is qr = q [ci(r); k]. The MPI of r-th region can be expressed as

The MPI is additively decomposable with population share weights

The contribution of MPI of r-th region to overall MPI is measured as follows

Further Eq. (9) explain the contribution of the j-th indicator to MPI. Equation (10) explains the contribution of the j-th indicator to the r-th region.

The number of deprived people who are multidimensional poor in the indicator j is \(\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{q} W_{i} h_{i} c_{ij} \left( k \right)\). Hence, the contribution of j-th indicator to MPI can be expressed as

The contribution of j-th indicator to MPI of r-th region can be expressed as

Degree of multidimensional poverty and ordered logit model

We have categorized the households into three sub-groups on the basis of overall deprivation score of the households. These three groups are (i) multidimensionally non-poor, ii) ordinary multidimensional poor, and (ii) severely multidimensional poor. These three types can be defined by deprivation score \(c_{i}\) (UNDP, 2010, 2015, 2019). If, \(0 \le c_{i} < 33.33\), the ith household is multidimensional non-poor; 33 ≤ \(c_{i}\) < 50, the ith households is ordinary multidimensional poor and \(c_{i}\) ≥ 50%, the ith household is severely multidimensional poor.

The ordered logit model is used to estimate the impact of regional variation on the degree of multidimensional poverty at the household level because the outcome variable is an ordered variable as non-poor (= 0), ordinary poor (= 1) and severely poor (= 2) have a hierarchical order. It is used to analyse the degree of multidimensional poverty across sample households in India for pooled data of two years 2005–06 and 2015–16. For individual ‘i’ with time ‘t’ it is specified as in Eq. (9)

For an m (= 3 in the present case) alternative ordered logit model, the regression parameters β, and the m-1 threshold parameters, are obtained by maximizing the log likelihood with \(p_{ij} = \Pr \left( {y_{it} = j} \right)\), Cameron and Trivedi, (2005). If βj is positive, then an increase in xij necessarily decreases the probability of being in the lowest category (yit = 1) and increases the probability of being in the highest category (yit = m). The Marginal effects of the probability of choosing alternative j when regressor xit changes is given by

Here the regressors \(\left( {{\varvec{x}}_{{\user2{it }}} } \right)\) include the characteristics of the household (control variables in the model), regional dummies and time dummies (explained in Table 6).

Data

This study has calculated the MPI at the regional level of India utilizing the third (NFHS-3) and fourth rounds (NFHS-4) of the NFHS data for the years 2005–2006 and 2015–2016 respectively. The NFHS survey is conducted by the International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, India and it is an extended project of the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted globally. According to the reports of the IIPS (2007 and 2017), the sample level of the two surveys namely NFHS-3 and NFHS-4 are comparable over time across the states of India. Thus, we have utilized the data sets for cross-section estimates and inter-temporal comparisons. A total of 109,041 sampled households in 2005–06 and 601,509 sampled households in 2015–16 were considered for the analysis. This data set has been extensively used in the existing literature to measure multidimensional poverty in India (for example see Alkire & Seth, 2015; Alkire et al. 2018; and UNDP, 2019).

Dimensions and indicators of multidimensional poverty

Table 2 presents the constituents of the MPI, they consist of ten indicators which are classified under three important dimensions namely, education, health and the standard of living following the Human Development Reports (2010, 2015 and 2019) on the criterion for the choice of the dimensions. These indicators reflect different Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) extensively discussed by Alkire and Jahan (2018) and UNDP (2019). Equal weights are assigned to each dimension and each indicator within the dimensions following (Alkire & Santos, 2010; Alkire & Seth, 2015; UNDP, 2015, and 2019). The first two columns of Table 2 present the dimensions and indicators used in the analysis respectively, whereas the third column explains the deprivation cut-off of each of the ten indicators. As evident from columns four and five of Table 2 a perceptible decline in deprivation occurred over the decade expressed through the indicators. This decline of percentage share of deprived people is statistically significant for all indicators. The indicators measuring deprivation in electricity (−23.2) has the highest percentage change in decline followed by nutrition (−21.6) and sanitation (−18.5). The results demonstrate India’s ability to creating pathways to achieve SDG (7)—ensuring access to affordable modern energy for all; SDG (2)—ensuring zero hunger and food security for all and SDG (6)—ensuring availability of water and sanitation management for all. According to the reports of N.I.T.I. Aayog (2018) India has set the Goal for 2030 following the Sustainable Development Agenda, to end hunger and malnourishment. In addition, the report further emphasizes India’s target to improve sanitation and hygiene and lessen shocks owing to vulnerability. This empirical exercise reveals the several challenges India is still facing at the regional level in achieving the SDGs and further reduce regional disparity. The analysis of data highlights the key areas in which India needs to invest resources and closely monitor the regions to measure the decadal progress and shortfalls.

Results

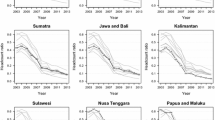

The robustness of the estimate of the multidimensional poverty index and its components is checked by dominance analysis (Alkire & Seth, 2015; Das et al. 2021). The dominance relation is shown across the regions in the years 2005–2006 and 2015–16. The multidimensional headcount ratio (H) and the multidimensional poverty index (MPI) are estimated by varying k that is using different estimation cut-offs. The use of different deprivation cut-offs by varying k does not alter the rank order of the H and MPI (as shown in Figs. 1, 2). Since in both periods each curve of a particular region lies below or above one another we find that the dominance behaviour is true between two regions. We also conducted the sensitivity analysis to see if the rankings of regions within the country alter when a different poverty cut-off is used (Alkire et al. 2019). Here we check the sensitivity of MPI and its component H for 10 different cut-offs. The relative ranking of six regions of India is shown in Fig. 1 for H and Fig. 2 for MPI for two different years respectively. In terms of H and MPI the relative positions of the East, Central, North-East, West, South, and North regions are same across different cut-offs. For the specific cut-off (k = 33.33) the values of H and MPI of different regions are also in the same order.

Source: As in Table 1. Compilation Author

Multidimensional Head Count Ratio across Regions for the different cut-off of Multidimensional Poverty

Source: As in Table 2. Compilation Author

MPI across Regions for the different cut-off of Multidimensional Poverty

Deprivation across indicators in different regions of India

Table 3 reports the percentage share of deprived people in the ten indicators of multidimensional poverty across regions for the years 2005–2006 and 2015–2016. The percentage share of deprivation varies widely across regions. Among six regions of India, the Eastern region has the highest deprivation in several indicators in 2005–2006 –cooking fuel (87.2 per cent), electricity (58.1 per cent), assets (56 per cent), schooling (34.2 per cent) and school attendance (30.3 per cent). The deprivations in other four indicators in this year (viz. nutrition, sanitation, housing and child mortality) were highest in the Central region. The Southern region of India has the lowest deprivations in all indicators except cooking fuel. The deprivation in cooking fuel was the lowest in the Western region. The percentage shares of deprived people across regions significantly declined for most of the indicators during 2005–2006 and 2015–2016. However, the rank order of the different regions with respect of deprivation across indicators was more or less same in the two periods.

The results based on the deprivation across the indicators among the regions of India indicate a degree of complementarity. For example, the Eastern and the Central region have higher population deprivation across the indicators in both years though there has been a decline in the share of deprivation in 2015–2016. Such findings explain the complementarity behaviour across the deprivation indicators. Educational deprivation may lead to welfare and nutritional deprivation owing to the lack of intrinsic knowledge on health and welfare. Nutritional deprivation may also create educational deprivation owing to ill health which exacerbates other forms of deprivation. Explorations on the regional dimension of the MPI throw proper insights into the crucial association of deprivation. Such relationships may get concealed at an aggregated standpoint. Identifying the complementarity in the share of population deprivation may contribute towards more suitable policy specification targeted across the most disadvantaged sub-population.

Status of multidimensional poverty across regions of India

Table 4 presents the percentage share of population across regions to the all-India total population; headcount ratio of multidimensional poverty (H); intensity of multidimensional poverty (A) and the overall multidimensional poverty index (MPI) across the major regions of India. Furthermore, it also presents the regional concentration of MPI namely MPIcont. During 2005–2006 the Eastern region had the highest H 68.4 per cent followed by the Central region 67.8 per cent. The region having the lowest H is the Northern region 32.1 per cent. In 2015–2016 the Eastern region continues to have the highest H 40.2 per cent, followed by the Central region 39.7 per cent. The lowest H is found in the Northern region 9.1 per cent. The Northern region experienced a threefold decline in H over the decade 2005–2006 /2015–2016. The Northern region had also experienced a large decline in the share of the population experiencing deprivation in the indicators of MPI. The findings from Table 4 reconfirm the findings of Table 3 that the decline in the components of MPI is regressive. The intensity of the multidimensional poor (A) is highest in the Eastern region in both the years 2005–2006 (54.4) and 2015–2016 (44.6). It is lowest in the Northern region (45.7) in the year 2005–2006 and in the Southern region (39.5) in the year 2015–2016. The MPI in 2005–2006 is highest in the Eastern region (0.372) and continues to be the highest (0.179) in 2015–2016 though there is a substantial decline over the decade. The Northern region has the lowest MPI in both the years 0.14 (2005–2006) and 0.03 (2015–2016). The regressive nature of decline in H and A over 2005–2006 /2015–2016 manifests in the regressive nature of the decline in MPI.

The regional concentration of multidimensional poverty is evident as we compare the MPIcont along with the share of population of a region. The contribution of MPI in Central and Eastern regions were higher compared to their share of population. These two regions account for 63 per cent of multidimensional poverty in India within the total population share of 48.6 per cent in 2005–06 thereby manifesting the concentration of poverty in the two regions. The concentration of multidimensional poverty increased further in 2015–2016 with MPIcont rising to 70.3 per cent within 47.5 per cent share of population.

MPIcont is relatively low in Northern ( 3.1 per cent) and Western (16.1 per cent) regions compared with their share of population (5.9 and 20.2 per cent respectively) and it has significantly declined during 2005–2006 and 2015–2016. This decline in MPIcont can be explained by the significant decline in the percentage share in the deprivation indicators (Table 3). The decline in the percentage share of deprivation across the indicators of MPI for the Northern region over 2005–2006 to 2015–2016 was about half for the schooling indicator; the nutrition indicator; child mortality indicator and about five times for the asset indicator. Such reduction in the population shares of deprivation explained the decline in the regional concentration of MPI.

The contributions of different indicators in the formulation of MPI are given in Appendix (Table 1). The salient features relating to the influence of different indicators in MPI are: (a) the contribution of four indicators namely nutrition, schooling, cooking fuels and sanitation is relatively high in both periods 2005–2006 and 2015–2016 respectively across all regions; (b) across all the regions the contribution of the indicators safe drinking water and child mortality is low in relative terms to MPI. (c) Further as far as intertemporal comparisons are concerned the contribution of the following indicators to MPI declined in 2015–2016 vis-à-vis in 2005–2006: schooling; nutrition; child mortality; sanitation; safe drinking water and housing. (d) As far as the share of the contribution of the indicators to MPI is concerned a substantial variation across regions is observed.

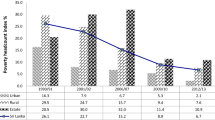

MPI by population subgroups in different regions of India

Table 5 reports the MPI across rural and urban areas; social sub-groups of population and religious sub-groups of the population for the Eastern; Western; Northern; South; North East and Central regions of India in the years 2005–2006 and 2015–2016. Rural poverty continues to be higher in all the regions of India for both years. Though for both the rural and urban areas MPI has reduced from 2005–2006 to 2015–2016 by almost half. The Eastern (0.43 in 2005–2006 and 0.21 in 2015–2016) and the Central (0.41 in 2005–2006 and 0.21 in 2015–2016) rural regions of India have higher MPI; the Northern rural region has the lowest MPI (0.18 in 2005–2006 and 0.05 in 2015–2016). The reduction in multidimensional poverty across rural and urban regions in India is regressive. The Scheduled Tribe (ST) population in the Eastern region have highest deprivation (0.52) followed by the Central region (0.50) in 2005–2006. In 2015–2016 the ST population for the Central region has the highest MPI 0.29 followed by the Eastern region 0.28. For other social sub-groups in both the years, the Eastern region and the Central region have higher MPI. The Northern region has the lowest MPI across all social groups for both years. The regions facing the lowest MPI were able to reduce deprivation faster over the decade for the social sub-groups of population. However, the deprivation continues to be highest among the ST population. As far as the position of MPI across religious subgroups of the population is concerned the Muslims across all regions have the highest MPI, for example, it is 0.44 for the Eastern region; 0.18 for the Western region and 0.40 for the North-Eastern region in 2005–2006. The Muslims continue to face greater deprivation in 2015–2016 though the levels of MPI have declined to almost half.

Degree of multidimensional poverty across regions of India

This section analyses trends in impoverishment for the geographical regions of India using the vector of deprivation cut-offs (k) (explained in "Methodology" section) for the years 2005–2006 and 2015–2016. The analysis explores how the subset of the population changes over time who are multidimensional poor but not impoverished in comparison to those who are ordinary multidimensional poor but not severely destitute Over the same period the sub-group of the population belonging to the set of ordinary multidimensional poor decreased in all regions. The percentage share of ordinary multidimensional poor decreased from 28.6 to 26.6 in the Eastern region, from 32.7 to 27.5 in the Central region, from 25 to 16 in the Western region and from 20.5 to 7.2 in the Northern region. In the Southern region it has declined at the extent of 18.4 percentage points, from 27.2 per cent to 9.4 per cent. The subgroup defined as severely multidimensional poor dropped from 39.8 per cent to 13.6 per cent in the Eastern region, from 20.3 per cent to 5.7 per cent in the Western region, from 11.6 per cent to 1.9 per cent in the Northern region, from 14.5 per cent to 1.8 per cent in the Southern region, from 27.7 per cent to 9.3 per cent in the North East region and from 35.2 per cent to 12.2 per cent for the Central region.

Such exploration reveals the degree of variability across regions in combatting absolute impoverishment in multidimensional poverty. The severity of destitution reduced by one third in the regions with a higher percentage of population experiencing severity in multidimensional poverty. For regions with fewer people within the sub-group severely multidimensional poor in 2005–2006, experienced a higher rate of decline, almost 10 times the population belonging to this group reduced in 2015–2016. The decline in ordinary multidimensional poor and severely multidimensional poor is not uniform across regions.

Analysis of determinants of multidimensional poverty

The results based on logistic regressionFootnote 4 across households and the impact of household’s characteristics, regional dummies (five dummies for six regions) and time dummy on the degree of multidimensional poverty is reported in Table 7. The household size, rural location, social group (ST, SC and OBC) and religious faith practiced (Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Sikh) significantly impact on the degree of multidimensional poverty. Multidimensional poverty levels decline for the Christian and Sikh households, for households in the Southern and the Northern regions. Further multidimensional poverty declines in small households and households with higher educated household head. The results demonstrate that the reduction in overall severity in multidimensional poverty across regions in India has not helped the households belonging to the marginalized social groups (ST and SC), the Hindu and Muslim households and household residing in the Eastern, Western and Central regions of IndiaFootnote 5.

The results based on the logistic regression Table 7 demonstrates the reflections of the impact of the policy spread in India to reduce multidimensional poverty and how the policy prescriptions have impacted the households. The choice of the explanatory variables to explore the impact on multidimensional poverty was restricted to demographic characteristics and socio-religious perspectives to reduce endogeneity in measurement. As far as the regional disparity in household characteristics of MPI is concerned, all the regions significantly impact the household level poverty at the multidimensional level. However, the degree of multidimensional poverty is significantly higher for the households located in Eastern, Western and Central regions. On the other hand, it is significantly low in the Northern and Southern regions. The Eastern region has the highest impact on the degree of multidimensional poverty with the marginal effect being 0.036, followed by the Central region (0.029).

Discussion

Deliberations on multidimensional poverty in India are on the topmost area of research particularly at the backdrop of the SDGs to eradicate poverty, hunger, malnutrition, illiteracy and other form of deprivations. This study examines the variations in the multidimensional poverty explicated through the headcount ratio, the intensity of poverty and MPI over 2005–2006 and 2015 -2016 for different geographic regions of India. The investigation of MPI across regions of India is crucial for policy insights since India shows vast heterogeneity across regions owing to climatic conditions, socio-cultural background and demographic changes. The results show that for the less impoverished regions the MPI almost reduced to more than half during 2005–2006 to 2015–2016. However, the eastern region of India continues to face high levels of MPI both in 2005–2006 and 2015–2016. Furthermore, when explorations of multidimensional poverty are made across social groups and religious groups, we find that the patterns of reduction of multidimensional poverty are regressive, such findings do not confirm the works of Alkire et al. 2021. The study by Alkire et al. (2021) obtained those states of India which had higher MPI reduced their levels of MPI faster in 2015–2016. However, the reduction in headcount ratio in MPI explained in the study by Alkire et al. (2021) showed a regressive trend confirming the present study.

The current study summarizes that despite lowering of deprivation along a regional dimension, the socially disadvantaged population sub-groups namely the STs and the Muslim population continue to be severely multidimensional poor in the most deprived regions, confirming the earlier studies of Das and Barua (1996); Sarkar (2012), Ohlan (2013) and recently Das et al. (2021).

The reduction in multidimensional poverty during 2005–2006 to 2015–2016 was due to a significant reduction of deprivation in the number of indicators particularly the schooling indicator, the nutritional security indicator, child mortality indicator, and electrification indicator. Such findings are confirmed in the study by Deaton and Drèze (2009) and Srivastava and Chand (2017). According to Gupta and Gupta (2013) and Jha and Acharya (2016), the Integrated Child Development Programme played a major role in uplifting the nutritional standards. The Government of India had launched various targeted nutritional programmes to improve the health standards, particularly among women and children across the deprived regions. These include Integrated Child Development Services Scheme; Midday Meal Programme and National Iodine Deficiency Disorders Control Programme among others. Since 1985 the Government of India has initiated efforts to provide affordable housing for poor households particularly the vulnerable social groups under the scheme Indira Awaas Yojana. The Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana declared in 2016, attempts to consolidate the earlier efforts and proposes to provide affordable housing for the socially vulnerable groups by 2022. The programme envisages providing a pucca house and linking with basic amenities like water supply, electricity and fuel connection. Such programmes with continuity in scope and application has impacted in reducing the deprivation in the indicators over time.

Recently the Government of India has launched a novel nutritional programme The POSHAN Abhiyaan in 2018, Paul et al. (2018). The thrust of emphasis of this programme is to reach the most deprived region so that there is a far-reaching reduction in overall nutritional deprivation in India. Such policy initiatives by the government of India demonstrate the renewed and continued efforts of the government to move towards the target of SDG of zero hunger and food security for all. Krishnan et al. (2017) discuss that the Right to Education Act 2009 enacted by the government of India was a landmark policy thrust for making school education compulsory for all. Such policy initiative had its transmission in reducing schooling deprivation inequality across the major regions of India. Thomas et al. (2020) discuss that the National Electrification Policy 2005 adopted by the government of India has a positive impact on household expenditure and household activities and asset ownership. The mission to provide electricity to all the Indian villages indeed enlarges the scope for expanding opportunities to tackle poverty and it has played an important role in reducing deprivation.

This study, an examination of the regional disparity in multidimensional poverty brings to the forefront that though India has benefited from a plethora of programmes on development yet regional and social disparities continue to exist in India which exacerbate the multidimensional poverty. Aklin et al. (2021) discuss in the context of India that public policies have played important role in ameliorating poverty. However, India has also experienced inequality as far as policy implementation is concerned even in a democratic arrangement of government. Such instances have transformed into the persistence of multidimensional poverty and exacerbating regional, social and religious disparity.

Conclusion and policy discussions

This paper is the first of its kind to our knowledge that investigated the status of multidimensional poverty over a decade 2005–2006 to 2015–2016 across the regions of India using the data sets from the third and the fourth rounds of National Family and Health Surveys. We have also categorized the households into three sub-groups following UNDP (2010, 2015, and 2019) based on the levels of deprivation to examine whether the depth and intensity of multidimensional poverty have reduced across the population over the decade. Furthermore, the paper also explored the multidimensional poverty changes over 2005–2006 and 2015–2016 for various social and religious groups of India. The results based on regional disparity in MPI show that Eastern region has the highest deprivation in 2005–2006 and even in 2015–2016 the region continues to face the highest deprivation. The North Eastern region of India experienced a rapid decline as far as deprivation in the intensity of poor is concerned. The results further show that reductions in multidimensional poverty across the regions of India continue to be regressive. The regions with high intensity and depth of poverty had a slow reduction in deprivation compared to regions that had low intensity and depth of poverty. As far as MPI across the social and religious population subgroups is concerned the Scheduled Tribes and the Muslims across the regions of India face the highest deprivation.

Turning to the indicators of multidimensional poverty we find that over the decade the deprivation in indicators particularly schooling, nutritional security, electricity and housing facility declined to almost half in the regions under study which explains the reduction in overall MPI from 2005–2006 to 2015–2016. The Government of India adopted several development programmes like the Integrated Child Development Programme, Midday Meal Programme, Universalizing Education and enacting the Right to Education for All (2009). Such programmes transpired into reducing deprivation in MPI. A common pattern that can be seen across almost all regions is that the share of the population that is severely multidimensional poor has gone down. However, the results from the study show that changes in population distribution from one sub-group to another was not uniform across regions. Analysing the multidimensional poverty determinants based on the logistic regression decomposed across regions, social groups and religious groups adds additional insights in the study. We find that the overall reduction in MPI has not helped the ST households and the Muslim households in particular. MPI reduces with the education of the head of the household and smaller household size have a significant reduction in MPI.

Policy discussions

The findings from this study demonstrated regional variations in reduction of MPI. This feature articulates the lack of commitment across the poor performing regions as far as policy implementation is involved. The gross regional disparities in the context of MPI in India are a glaring case study of policy implementation gaps/failures at the regional level. There is urgent need to explore in Indian context the importance of commitments across bureaucracy and political parties.

According to (Chopra, 2019) the policy framed at the national level in India face inconsistency as far as its implementation is concerned at sub-national levels. The study points out that the inconsistency as far as implementation is concerned could be owing to i) variation in degree of local political authority and ii) general rules described at the local contexts vary across regions as far as implementation is concerned. The central government often lacks clarity in facing these varying local challenges in the case of implementing the national policies. The study by (Hudson et al. 2019) rightly points out that there are two elements associated with commitment-i) action and ii) intention. The authors further point out that variations in outcomes in policy implementation is chiefly due to lack of intention. The study specifies that actions are traceable but intentions are not.

The failures in policy outcomes and hence the stark empirical evidence in Indian context with the context of regional poverty can be attributed chiefly to the following aspects:

(1) Lack of proper guidelines for implementation and local follow up; (2) no strict analysis is made at the administrative level in the past four decades to understand rigorously the causes of missing links in the implementation process; (3) lack of practices in organizing the major stakeholders in the projects. Contrary to being active agency in development programmes the stakeholders are often silent non-recipients of the development projects and (4) lack of consistency in the efforts of making the financial sanctions at the local level. There are absolutely no follow-up mechanisms.

However, there is a glimmering reality against the backdrop of despair at the regional level. Recently with the pressure from the civil society and the stern directions by the Apex Court of India increasing attention is being paid to the mother and child nutritional programmes, (Rajan et al. 2014).

In sum the task ahead is to ensure that policy design and implementation becomes a holistic process in the context of India’s efforts to attain the Sustainable Development Goals. The policy makers should strive to ensure that agencies associated with the process of implementation should possesses the adequate skill, competencies and the willingness to address the process of implementation of policies. To make both the short term and medium-term assessments on the efficacy of policy implementation there should be periodic reviews. Further to assess whether regional variation in the reduction in MPI is linked with policy failures there is the urgency of creating new data sets. Till date the data sets are linked with the outcomes of the variables but not linked with the policy prescriptions and implementation.

Limitations and scope for further research

The results of this study leave scope for quite a few avenues for further research. One interesting issue is understanding the differences in performance of multidimensional poverty across different subgroups of vulnerability. It is also important to analyse the different features of indicators of risk associated with different dimensions of vulnerability across the regions of India. This would be useful for providing guidance to policy planners for developing programmes on public welfare.

Data Availability

Data used for this study is available at International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. (2017). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16: India. Mumbai: IIPS. URL: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/nfhs-4Reports/India.pdf. ( Accessed on 6, May, 2021).

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. (2007). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06, India, Volume I and II, Mumbai: IIPS. URL: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/frind3/frind3-vol1andvol2.pdf. (Accessed on 6, May, 2021).

Notes

The states of India have been grouped into six zones having an Advisory Council "to develop the habit of cooperative working" among these States. Zonal Councils were set up vide Part-III of the States Reorganisation Act, 1956. The North Eastern States' special problems are addressed by another statutory body—The North Eastern Council, created by the North Eastern Council Act, 1971. The states are chosen to maintain a comparative perspective over the two rounds of NFHS namely NFHS-3 (2005–06) and NFHS-4 (2015–16).

Official age of children starting primary schooling in India is 6 years (Source: https://mhrd.gov.in/rte).

The results based on the logistic regression model are derived on the basis of probabilistic arguments.

Age of the household in completed years squared component is included to demonstrate the quadratic type of association between age and MPI following the study of Rahman (2013).

References

Aayog, N. I. T. I.(2018). SDG India Index, Baseline Report. Retrieved 14, May, 2021 from SDX-Index-India-21–12–2018.pdf (un.org)

Aklin, M., Cheng, C., & Urpelainen, J. (2021). Inequality in policy implementation: Caste and electrification in rural India. Journal of Public Policy, 41(2), 331–359.

Alkire, S. (2002). Dimensions of human development. World Development., 30(2), 181–205.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011). Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7–8), 476–487.

Alkire, S., & Jahan, S. (2018). The new global MPI 2018: aligning with the sustainable development goals. OPHI Working Paper No. 121. University of Oxford, Oxford. Retrieved 6, May, 2021 from https://www.ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/OPHIWP121_vs2.pdf

Alkire, S., Kanagaratnam, U., Nogales, R., & Suppa, N. (2019). Sensitivity analyses in poverty measurement: the case of the global multidimensional poverty index, https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:95e0828f-4365-4dc8-8850-af2a13892ce7

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2010). Multidimensional Poverty Index 2010: Research Briefing. University of Oxford, Oxford Retrieved 6, May, 2021 from https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:f150e243-8675-4899-a292-fd006aeaf038

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2011). Acute multidimensional poverty: A new index for developing countries. Proceedings of the German Development Economics Conference, Berlin 2011, No. 3, ZBW – Deutsche. Retrieved 6, May, 2021 from https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/48297/1/3_alkire.pdf

Alkire, S., & Seth, S. (2008). Measuring multidimensional poverty in India: a new proposal. OPHI Working Paper No. 15. University of Oxford, Oxford. Retrieved 6, May 2021 from http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1815355

Alkire, S., & Seth, S. (2015). Multidimensional poverty reduction in India between 1999 and 2006: Where and how? World Development, 72(C), 93–108.

Alkire, S., Foster, J. E., Seth, S., Santos, M. E., Roche, J. M., & Fernandez, P. B. (2015). Multidimensional poverty measurement and analysis: chapter 5-the Alkire-Foster counting methodology. OPHI Working Paper No. 86. University of Oxford, Oxford. Retrieved 6, May 2021 from https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:18453363-2bc0-4f3c-906c-0061968ee629/

Alkire, S., Oldiges, C., & Kanagaratnam, U. (2018). Multidimensional Poverty Reduction in India 2005 / 6 – 2015 / 16: Still a Long Way to Go but the Poorest Are Catching Up. Research in Progress Series 54a, Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, University of Oxford.

Alkire, S., Oldiges, C., & Kanagaratnam, U. (2021). Examining multidimensional poverty reduction in India 2005/6–2015/16: Insights and oversights of the headcount ratio. World Development. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105454

Atkinson, A. B., & Bourguignon, F. (1982). The comparison of multi-dimensioned distributions of economic status. The Review of Economic Studies, 49(2), 183–201.

Bhatty, K. (1998). Educational deprivation in India: A survey of field investigations. Economic and Political Weekly., 33(28), 1858–1869.

Bourguignon, F., & Chakravarty, S. R. (2003). The measurement of multidimensional poverty. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 1(1), 25–49.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Micro econometrics: Methods and applications. Cambridge University Press.

Chopra, D. (2019). Accounting for success and failure in policy implementation: The role of commitment in India’s MGNREGA. Development Policy Review, 37(6), 789–811.

Das, P., Paria, B., & Firdaush, S. (2021). Juxtaposing consumption poverty and multidimensional poverty: A study in Indian context. Social Indicators Research, 153(2), 469–501.

Das, S. K., & Barua, A. (1996). Regional inequalities, economic growth and liberalisation: A study of the Indian economy. The Journal of Development Studies, 32(3), 364–390.

Deaton, A., & Drèze, J. (2009). Food and nutrition in India: Facts and interpretations. Economic and Political Weekly, 44(7), 42–65.

Deinne, C. E., & Ajayi, D. D. (2019). A socio-spatial perspective of multi-dimensional poverty in Delta state. Nigeria. Geojournal, 84(3), 703–717.

Dehury, B. & Mohanty, S. (2015). Regional Estimates of Multidimensional Poverty in India. Economics, 9(1), Retrieved 6, May 2021 from http://www.economicsejournal.org/dataset/PDFs/journalarticles_2015-36.pdf

Dev, M. S. (2010). Inclusive growth in India: Agriculture poverty and human development. Oxford India Paperback.

Dholakia, R. H. (1985). Regional disparity in economic growth in India. Himalaya Publishing House.

Gajwani, Kiran, Ravi Kanbur and Xiaobo Zhang. (2007). Comparing the Evolution of Spatial Inequality in China and India: A Fifty-Year Perspective. Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics,155–177.

Gupta, A., Gupta, S., & Nongkynrih, B. (2013). Integrated child development services (ICDS) scheme: A journey of 37 years. Indian Journal of Community Health, 25(1), 77–81.

Hudson, B., Hunter, D., & Peckham, S. (2019). Policy failure and the policy-implementation gap: Can policy support programs help? Policy Design and Practice, 2(1), 1–14.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. (2017). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16: India. Mumbai: IIPS. Retrieved 6, May, 2021 from http://rchiips.org/nfhs/nfhs-4Reports/India.pdf

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro (2007). International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06, India, Volume I and II, Mumbai: IIPS. Retrieved 6, May, 2021 from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/frind3/frind3-vol1andvol2.pdf

Jha, P., & Acharya, N. (2016). Public provisioning for social protection and its implications for food security. Economic & Political Weekly, 51(18), 98–100.

Jose, A. (2019). India’s regional disparity and its policy responses. Journal of Public Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1933

Kanbur, R., & Venables, A. J. (2007). Spatial disparities and economic development. In D. Held & A. Kaya (Eds.), Global inequality: Patterns and explanations (pp. 204–215). Polity Press.

Khan, I., Saqib, M., & Hafidi, H. (2021). Poverty and environmental nexus in rural Pakistan: A multidimensional approach. GeoJournal, 86(2), 663–677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-10090-6

Krishna, A. H., Sekhar, M. R., Teja, K. R., & Swamy, B. A. (2017). Primary education during pre and post right to education (RTE) act 2009: An empirical analysis of selected states in India. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI), 6(11), 41–51.

Mishra, A., & Ray, R. (2013). Multi-dimensional deprivation in India during and after the reforms: Do the household expenditure and the family health surveys present consistent evidence? Social Indicators Research., 110(2), 791–818.

Mohanty, S. K. (2011). Multidimensional poverty and child survival in India. Plos one. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026857

Mukhopadhyay A, Garcés Urzainqui D. (2018). The dynamics of spatial and local inequalities in India. WIDER Working Paper; 2018. Retrieved 18, May 2021 from http://www.ecineq.org/ecineq_paris19/papers_EcineqPSE/paper_297.pdf

Ohlan, R. (2013). Pattern of regional disparities in socio-economic development in India: District level analysis. Social Indicators Research., 114(3), 841–873.

Paul, V. K., Singh, A., & Palit, S. (2018). POSHAN Abhiyaan: Making nutrition a jan andolan. Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy., 84(4), 835–841.

Rahman, M. A. (2013). Household characteristics and poverty: A logistic regression analysis. The Journal of Developing Areas, 47(1), 303–317.

Rajan, P., Gayathri, K. and Gangbar, J. (2014). ‘Child and maternal health and nutrition in South Asia – Lessons for India’. Working paper 323. Bangalore: Institute for Social and Economic Change.

Rauniyar, G., & Kanbur, R. (2010). Inclusive growth and inclusive development: A review and synthesis of Asian Development Bank literature. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 15(4), 455–469.

Santos, M. E. (2014). Measuring multidimensional poverty in Latin America: Previous experience and the way forward. OPHI Working Paper no. 66. University of Oxford, Oxford. Retrieved 6, May, 2021 from https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:6442bdb7-c0f4-4dbf-9ae5-a98477966a0d/download_file

Sarkar, S. (2018). Multidimensional Poverty in India: Insights from NSSO data. Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, University of Oxford. Retrieved 18, May 2021 from https //www.ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Sandip-Sarkar-Multidimensional-Poverty-in-India.pdf

Sarkar, S. (2012). Multi-dimensional Poverty in India: Insights from NSSO data. OPHI Working Paper. Resource document. Retrieved 6, May, 2021 from OPHI. Retrieved form Aug 14 2017, http: //www. ophi. org. uk/wp-conte nt/uploa ds/Sandi p-Sarka r-Multi dimen siona l-Pover ty-in-India. pdf

Sydunnaher, S., Islam, K. S., & Morshed, M. M. (2019). Spatiality of a multidimensional poverty index: A case study of Khulna City. Bangladesh. Geojournal, 84(6), 1403–1416.

Srivastava, S. K., & Chand, R. (2017). Tracking Transition in Calorie-Intake among Indian. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 30(347–2017–2034), 23–35.

Sundaram, K., & Tendulkar, S. D. (1995). On measuring shelter deprivation in India. Indian Economic Review, 30(2), 131–165.

Thomas, D. R., Harish, S. P., Kennedy, R., & Urpelainen, J. (2020). The effects of rural electrification in India: An instrumental variable approach at the household level. Journal of Development Economics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102520

Tripathi, S., & Yenneti, K. (2020). Measurement of multidimensional poverty in India: A State-level analysis. Indian Journal of Human Development, 14(2), 257–274.

UNDP (2019). The 2019 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). Retrieved 6, May, 2021 from http://hdr.undp.org/en/2019-MPI

UNDP (2015). Human development report 2015. Work for human development. United nations development Programme. Retrieved from 6, May, 2021 from http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2015_human_development_report.pdf.

UNDP. (2010). Human development report: The real wealth of nations: Pathways to human development. Macmillan.

Whelan, C., Nolan, B., & Maitre, B. (2012). GINI DP 40: Multidimensional Poverty Measurement in Europe: An Application of the Adjusted Headcount Approach (No. 40). AIAS, Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies. Retrieved 6, May, 2021 from http://archive.uva-aias.net/uploaded_files/publications/DP40-Whelan,Nolan,Maitre.pdf

World Bank (2018). India development update India's growth story (English). Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. Retrieved, 17, May 2021 from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/814101517840592525/India-development-update-Indias-growth-story

World Health Organization (2006). The world health report 2006: working together for health. World Health Organization. Retrieved 6, May, 2021 from https://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/

Funding

No funding is involved with this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Pinaki Das Methodology: Pinaki Das; Calculation: Bibek Paria; Formal analysis: Pinaki Das; Writing-original draft preparation: Sudeshna Ghosh; Resources: Pinaki Das.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

There is no potential conflict of interests

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table

8.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Das, P., Ghosh, S. & Paria, B. Multidimensional poverty in India: a study on regional disparities. GeoJournal 87, 3987–4006 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10483-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10483-6