Abstract

Measurement of social well-being among deprived communities is crucial to assess the extent of marginalization and identify their needs for development and planning. In India, Scheduled Tribes are considered as one of the most marginalized and least developed communities. At the same time, their levels of well-being vary from one place to another which is relatively neglected and hardly examined. The present study is an attempt to assess levels of social well-being among tribes in Mizoram, Northeast India. It also examines the relationship between inequality, marginalization and autonomy movement in the state. Principal Component Analysis shows that minority tribes in the remote southern regions have shown relatively lower standard of living. The low level of well-being of ethnic minorities in the south is attributed to the process of peripheralization starting from the colonial period. The homelands of ethnic minorities in Mizoram coincide with the more peripheral, remote and less developed areas which are turning into ‘terrain of struggle’ due to inter-ethnic conflicts. The paper argued that provision of autonomous councils to the southern tribes in the post-Independence period has largely failed to reduce the gap between the dominant tribe in the north and the minority tribes in the south but rather encourages other communities to demand autonomy. Under this circumstances, it is advocated that the approach to decentralization in Northeast India and Mizoram in particular to be shifted from ethnic-based to place-based decentralization with emphasis on local development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, disparity in social well-being among ethnic communities has aroused considerable interest among academics (Dai et al. 2018; Lymperopoulou & Finney, 2017). Sometimes synonymously used with quality of life and standard of living, social well-being is an approach to evaluate quality of life to understand the needs of particular social groups (Rist, 1980). As a multi-dimensional concept, social well-being covers objective information on living conditions as well as subjective views to provide a picture of quality of life of a particular community in a region (Cooke et al. 2007; Shucksmith et al. 2009). Marked and persistent inequalities among ethnic groups have been well documented in both developed and developing countries (see Epprecht et al. 2011; Kijima, 2006).

In India, one of the most exploited, isolated and deprived communities are the Scheduled Tribes (STs) (Bhalla & Luo, 2013; Kijima, 2006; Xaxa, 2011). According to 2011 Census, Scheduled Tribes constitute 8.6 per cent of India’s total population. As a ‘target group for reservation policies’ (Kijima, 2006), they are safeguarded against cultural assimilation and resource exploitation from outside to enhance their well-being through targeted welfare policies. Tribes are highly concentrated in the Himalayan states of Northeast India where more than 160 STs and over 400 other tribal and sub-tribal communities are found (NEC 2008). Autonomous district councils are provided to certain tribes in different parts of the region. But, the region is still witnessing inter-ethnic tensions, violent insurgencies and demand of autonomy by minority tribes.

Relatively little attention has been given to inequality among the tribes in India. Most of the existing literatures deal with inequality at state and district levels which entail the risk of inclusion of other communities. No sincere effort is also given to examine the relationship between disparities in social well-being and the process of marginalisation of peripheral tribes and the autonomy movement. Not only that, the impact of ethnic-based decentralization on the well-being of the tribes is hardly assessed even though a number of works have been produced on the political and cultural dimensions (see Singh, 2008; Roluahpuia, 2016). Most studies have also overlooked the effect of decentralization on “indigenous groups that remain minorities after decentralization” (Duncan, 2007:712). The present study, therefore, is an attempt to analyse quantitatively the extent of inequality in social well-being among ethnic communities in the multi-ethnic state of Mizoram, Northeast India. It also tries to examine the process of peripheralization of ethnic minorities as well as the impact of identity-based decentralized institutions in the process of enhancement of well-being of minority communities.

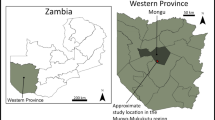

Also known as the Lushai Hills, the ethnic composition of Mizoram is dominated by a Tibeto-Burman speaking Mizos—a conglomerate of a number of tribes or sub-tribes who have traced a common origin including the Lusei (Lushai), the Mara (Lakher), the Lai (Pawi), the Paite (Paihte) and the Hmar (Fig. 1).Footnote 1 The Chakma and the Bru (Riang) constitute the non-Mizo communities in the state.Footnote 2 The state has experienced one of the most violent ethnic-based autonomy movements in India during 1966–1986. The Mizo National Front (MNF) led autonomy movement called Rambuai or ‘Troubled years’ was triggered by the failure of the Indian government to contain the severity of the infamous ecological disaster called Mautam tampui or ‘Bamboo famine’ of 1959–1960 (see Nag, 2001). Recently, the state has been witnessing demand for greater autonomy from the remotely located, culturally unique and relatively backward minority tribes like the Mara, the Lai, the Chakma, the Hmar and the Bru (see Bhatia, 2012). These minority tribes have been demanding either greater autonomy or separate autonomy to safeguard their cultural identities and uplift their socio-economic condition as well.

Literature review

Till recently, most geographical works on social well-being have been confined on analysis of objective parameters (see Knox, 1975; Pacione, 2003; Van Kamp et al. 2003; Marans & Stimson, 2011). Subjective well-being has been neglected by geographers except a few who have highlighted in their writings (see Pacione, 1982; Hellburn 1982; Smith, 1996) mainly due to paucity of data to determine “to what extent does where we live affect how we feel” (Ballas & Dorling, 2013:465). However, Wang and He (2016) observed that geographers’ emphasis on well-being has recently shifted from objective to subjective dimension (see Morrison, 2007, 2011; Dunning et al. 2008; Oktay & Rustemli, 2011; Saitluanga, 2014; Wang & Wang, 2016).

Ethnic inequality not only indicates peripheralisation and marginalisation of certain communities (Kuhn, 2015) but also generate hatred, social immobility and conflict (Alesina et al. 2012). Inter-tribal conflict in Northeast India is attributed to various interlinking factors like conflict over control of resources, disagreement over indigeneity as well as demand of autonomy by smaller communities (Bhaumik, 2004; Khobragade, 2010; Kolas, 2017). Intolerance among ethnic groups has resulted in widespread autonomy movement in the region (see Baruah, 1989; Xaxa, 2008; Roluahpuia, 2016).

To reduce ethnic conflicts and inequality, multi-ethnic states usually promote decentralization and multiculturalism (see Loh, 2017). In fact, while successful decentralization is expected to promote “the well-being of all people” (Kauzya, 2007: 12), experiences in some countries indicate that decentralization does not necessarily ensure ‘development’ or ‘democratic’ outcome (Seymour & Turner, 2002). It may also lead to “erosion of local conditions of well-being (Grindle, 2007: 70). As a result, countries have shifted the rationale for decentralization “from an emphasis on cultural, ethnic, linguistic, or religious factors, to one of achieving economic and social change” (Rodríguez-Pose & Ezcurra, 2010: 619). Recently, place-based approach of regional development has been advocated to enhance the unique capacity of territories (see Barca et al. 2012; Pugalis & Gray, 2016). By focussing on “identification and mobilisation of endogenous assets” (Dufty-Jones & Wray, 2013:112), the approach recognised the interests of ethnic and racial minorities in the process of regional development (see Pike et al. 2007).

Data and methodology

At the time of the study, there were eight districts in Mizoram. Stratified sampling technique was adopted to select 1313 households from three villages each of the eight districts to represent various tribal communities proportionately. Scheduled questionnaires were supplied to the respondents and face-to-face interviews were conducted at their residences. To get reliable information, only respondents above 18 years of age were selected.

Data were collected from a range of dimensions of social well-being including economic, social, housing, accessibility and residential environment dimensions to comprehend the broad concept of social well-being. Out of the 34 indicators selected to develop composite indices of social well-being, 19 were objective indicators while 15 were subjective indicators (see Table 1). The objective dimension comprises indicators pertaining to socio-economic, infrastructural, and accessibility measures. The subjective dimension may also be decomposed into indicators pertaining to satisfaction of residents from socio-economic environment, infrastructural condition, local services, and physical environments. Regarding subjective questions, respondents were requested to tick in one of the five boxes to indicate their level of satisfaction with each item on a five-point linear numeric version of a Likert scale, ‘1’ standing for strong level of dissatisfaction and ‘5’ representing a strong level of satisfaction.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is adopted as a quantitative technique to measure disparity in social well-being. Composite indices have been developed separately for the two dimensions of social well-being. The novel method developed by Nicoletti et al. (2000) has been applied here as a weighting technique. The method uses PCA to weight the index objectively according to the explained variance in the data. This method considers the factor loadings of the entire extracted components to weight a composite index (for detailed discussion on PCA, see Greyling, 2013; Saitluanga, 2017).

Objective social well-being

To measure objective social well-being among different ethnic groups, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was run in a Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and four components which explain 97.78 of the total variance were extracted. The percentage of variance explained is considered good enough to carry forward the analysis. The correlation coefficient matrix shows that most of the variables were inter-correlated and there was no extreme multicolinearity. The Kaiser-Meyer-Ohlin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy value was acceptable and the Bartlett’s test of Sphericity was significant at 0.05 level of significance.

The first component explains 51.78 per cent of the total variance explained. It is the most important component that determines variability in objective social well-being. This component consists of six indicator variables such as percentage of households good for residence (HH_Good), average distance to playground (Playground_D), number of schools/1000 population (School), percentage of workers engaged in non-agricultural sectors (No_Agri), number of health centers/1000 population (Hospital) and number of bank accounts/ household (Bank). The second component explains 20.39 per cent of the total variance explained. The indicators are household related well-beings such as percentage of reinforced cement concrete (RCC) houses (HH_RCC), percentage of households having treated tap water (Tap_Water), percentage of female graduate population (F_Grad), average distance to nearest bank (Bank_D), percentage of households having close drainage (Close_drainage) and percentage of households having septic tank (Septic_tank). The third component explains 17.60 per cent of the total variance explained. It includes indicators like percentage of households having computer (Computer), percentage of households having source of drinking water within premises (Water_Premises), percentage of households having four wheel vehicle (4Wheel) and per capita income (PCI). The fourth component includes three variables including percentage of households having separate bathroom (Bathroom), number of persons who have studied up to Class 12 and above per household (Edu 12) and percentage of households having more than three rooms (HH_3Rooms).

Variable weights were obtained with the help of PCA again. The highest weight was assigned to HH_Good (0.13) followed by Playground and School (0.11 each) while the lowest weights were assigned to HH_3Rooms, Edu12 and Bathroom. After the final weights were obtained, ethnic communities are classified into four categories based on their scores in the composite index (see Table 2). The Lushai (Lusei) and the Hmar communities are found out to be the highest ranking communities. The non-Mizo communities like the Chakma and the Bru are found at the bottom while the Mara (Lakher) and Lai (Pawi) occupy the middle position.

Subjective social well-being

Subjective social well-being among ethnic groups is measured again with the help of PCA. To construct a composite subjective index, the indicator variables were first normalized again. The correlation coefficients showed that most of the variables were inter-correlated and there was no extreme multicolinearity.

Four components were extracted which explain 97.69 per cent of the total variance. The first component contributes 49.49 per cent of the total variance explained. This component comprises indicators like satisfaction from community services within locality (S_Community), satisfaction from regularity of electricity (S_Electric), satisfaction from condition of village road (S_Infraroad), satisfaction from level of odour within neighbourhood (S_Smell), satisfaction from incidence of crime within locality (S_Crime) and satisfaction from local climatic environment for residence (S_Climate). The second component is constituted by indicators like satisfaction from quality of schools within village (S_School), satisfaction from availability of recreational places within village (S_Leisure), satisfaction from supply of water (S_Water) and satisfaction from supply of cooking gas (S_LPG). The third component comprises three variable indicators like satisfaction from quality of village for upbringing of children (S_Upchild), Satisfaction from safety of residence from landslide (S_Landslide) and satisfaction from slope of house site (S_Slope) while the fourth component which explained only 7.40 per cent of the total variance explained comprises satisfaction from participation in community activities (S_Participation) and satisfaction from economic condition of village (S_Economy).

Weights for every variable indicator were obtained again. S_Local has the highest weight score among all the indicators while S_Economy has the lowest weight. After obtaining the composite scores, ethnic groups were ranked on the basis of their scores. Hmar ethnic group has scored the highest in subjective well-being followed by Lai, Bru and Mara. The lowest ranking communities are the Lusei and the Chakma (see Table 3).

Despite the fact that the selected indicators for the two dimensions of well-being are not wholly comparable, it appears that the perceived living environment of the tribal communities differ from their objective environment. Although it is beyond the scope of this study to explain the difference between objective and subjective rankings, it may be noted that individual perception of well-being depends not only on the level of development of one’s own place but also on their “awareness of the experiences of other regions” (McCann, 2020: 257). Thus, subjective measurement could be influenced by the respondent’s level of knowledge which determines his/her level of aspirations and awareness on the state of affairs of his/her residential environment and of other regions.

Decentralization and regional development in Mizoram

The rise of inequality among the tribes of Mizoram is rooted in the colonial administration system and fragmented modernization process which has started during the colonial period. Tribes in the peripheral areas have lagged behind their counterparts in the centre not only because of their remote locations but also due to the unequal process of development which has hardly been addressed in the post-Independence period. After the production of colonial map and changed in administrative jurisdiction, the minority communities in Mizoram found themselves at the remotest corners of the state that wholly depended upon the new seat of administration in the north. After the Independence of India, the southern tribes have started demanding separate autonomy on account of their unique identities, relative backwardness and their settlements in a compact geographical area. The post-Independent India, while trying to achieve the dual target of protecting the identity of minority tribes and enhancing their quality of life through provision of autonomous councils, has largely failed to reduce the development gap. The disparity in social well-being between the dominant Lushai (Lusei) and peripheral minority communities is clearly observable from the above quantitative analysis (also see Table 4).

During the colonial era, Mizoram (then Lushai Hills) was the last frontier of India for the British Raj which has already annexed all the surrounding areas. The British were first reluctant to occupy the land which offered no valuable resources except timber and bamboo. However, after series of military explorations to subdue the warring tribes who often raided the colonial tea plantations in Cachar areas of Assam, the British formally occupied the Lushai Hills in 1890. As they entered the land from two sides, Lushai Hills was divided into two administrative areas – the South Lushai Hills and the North Lushai Hills. The former was ruled by the government of Bengal while the latter was under the government of Assam. To safeguard the hill tribes from their more civilised neighbours, the colonial government prohibited the entry of non-tribal plainsmen into the entire Lushai Hills by drawing a boundary line called the Inner Line which runs along the foothills (see Singh, 2008). Subsequently, the land was also declared a ‘backward tract’ and an ‘excluded area’ by the Government of India Acts 1919 and 1935 respectively which put the Lushai Hills under the control of the Governor in Council, not the provincial government.

During the initial period of the British occupation, the South Lushai Hills had the ‘locational advantage’ as the region was connected to Chittagong in Bengal (present Bangladesh) by River Khawthlangtuipui (Karnaphuli) through Tlabung (Demagiri)—the only river port-cum-trade centre in the entire Lushai Hills. However, starting with the handover of the administrative control of the South Lushai Hills to the government of Assam in 1898, the south has gradually lost its importance. River Tlawng (Dhaleshwari) which connects Assam with the capital of the Lushai Hills, Aizawl in the north became the main entry route of Mizoram until the construction of Aizawl—Silchar (Assam) road in 1942. The partition of British India and the formation of East Pakistan (present Bangladesh) at the time of the Independence of India led to complete closure of the Tlabung-Chittagong international border trade. The economy has struggled to cope up with the partition as the price of imported items like sugar, oil, salt have increased considerable after the partition while the price of exported items like cotton, til, orange etc. have declined substantially (see Roy Burman, 1970). The partition also stopped the export of bamboo and timber to Chandrakona Paper Mill in West Pakistan from the south Lushai Hills which has supplied almost 70 per cent of the raw materials. The southern Mizoram was thus connected to the outside world only through the north.

Moreover, the modernization process of the Lushai Hills, mainly through the works of the Christian missionaries, was highly localised and concentrated in the north mainly because of the remoteness of the south. The first two Christian missionaries arrived through the Tlawng River by boat and started working from Aizawl in 1894. They prepared a script of Duhlian—the language of the northern Lusei tribes which became the vernacular language in all schools throughout the state. Thus, the canonization of Duhlian has led to the rise of certain groups of people “who would eventually rise to be the elite of Zo society while others were marginalized” (Son-Doerschel, 2013:31). The non-Lusei speaking Mara tribe, on the other hand, got their first Christian missionary in 1907 only. The remoteness of the south has made it difficult to explore the land and the extreme south bordering Myanmar was not administered by the British until 1930 (Parry, 1932). Thus, the south became peripheral and the balance of power has shifted in favour of the Lusei dominated north since the colonial period which remains unchanged even after the Independence of India.

Ever since the dawn of the Independence of India, the Mara and the Lai tribes have been showing a tendency to separate from the dominant Lusei tribe. Realising their relatively low level of development and their minority status, they had the apprehension of losing their distinct identities and therefore exerted their rights to be accommodated in the post-colonial India (Hnialum, 2010). They have formed a political party called the Pawi-Lakher Tribal Union (PLTU) rather than joining the mainstream political parties. They were thus granted regional council in the name of Pawi-Lakher Regional Council (PLRC) in 1951 under the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution. However, the council was unable to function effectively due to ethnic power struggles between the Lai and the Mara (Pillai, 2002). In 1972, when the Mizo Hills Autonomous District under the government of Assam became a Union Territory (UT)—a province under the control of the central government with a certain degree of autonomy; the Lai and the Mara were also granted separate Autonomous District Councils (ADCs) to safeguard their customs and identities. At this time, the Chakmas who became the largest minorities in the state were also granted ADC.

The Chakmas and the Brus were hardly mentioned in the colonial history of Lushai Hills due to their negligible population. The Chakma have emigrated from the Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh during the colonial period and settled in the sparsely populated western borderlands of Mizoram. Significant numbers have joined them during the partition of India and after the construction of Kaptai Dam in 1957 as displaced migrants (see Roy Burman, 1970). The Bru or Reang are found in the northwestern borders of Mizoram. They speak a Tripuri dialect called Riang or KauBru which comes under Kokborak or Kokbarak. They are also considered by the Mizo as immigrants from the bordering state of Tripura but the Bru have claimed that they have once occupied the western part of Mizoram (Arshad, 2019; Chakma & Gogoi, 2018). The Chakmas and the Brus are relatively lagging behind other minorities as their modernization process has occurred lately. The first primary school in the Chakma settlement area was established only in 1949 (Paul, 2013). In the same year, the first three Mizo missionaries to work among the Chakmas and the Brus as evangelist teachers were sent by the Mizoram Presbyterian Church (Lawmsanga, 2010). Their standard of living, however, has hardly improved after more than 60 years. The Mizos perceive that they have no interest in education and other measures to improve their quality of life (Chakraborty, 2011). On the other hand, the two communities have claimed that the state government has discriminated against them in employment and deliberately blocked their access to education and other basic rights (see Chakma, 2009; Chakraborty, 2011; Chakma & Gogoi, 2018). Inter-ethnic tensions have frequently risen between the two communities and the Mizos. The Mizos have been pushing the government of India to dissolve the Chakma Council and they vehemently opposed when the Brus have demanded separate autonomous council within Mizoram (Roluahpuia, 2018).

The formation of Autonomous District Councils (ADCs) in the backward tribal areas of Northeast India was meant to protect the identity as well as to satisfy the demands of the ethnic minorities who do not share the agenda of the dominant ethnic group so that inter-ethnic assimilation and conflict may be avoided. According to Gassah (1997:3), ADCs were intended to serve three main purposes—to maintain the distinct identities of the smaller tribes, to prevent economic and social exploitation, and to allow the tribal people to develop and administer themselves according to their genius. While the ADCs are successful in promoting a sense of identity and territoriality among the tribes (Baruah, 1989), they are less successful in accommodating smaller communities within the council areas. As a result, they have been criticized for encouraging other minority communities to fight for autonomy (Lalfakzuala, 2016; Singh, 2008). Some scholars have advocated provision of either autonomous ‘regional council’ or ‘district council’ for underrepresented minority tribes (see Haokip, 2020). However, creation of more autonomous councils may foster difference and ‘separatist tendencies’ as it has happened elsewhere (see Cornell, 2002; Hale, 2004). In the meantime, the existing ADCs are craving for upgrading into territorial autonomous council to have full control on the entire administrative unit within their territory. It seems that attainment of ADC is seen as an ad-hoc institutional arrangement to pursue higher degree of autonomy in the form of Territorial Council, Union Territory and finally statehood (Patnaik, 2017).

Ethnic communities in Mizoram are not satisfied with the functioning of their autonomous councils due to deterioration of their own states of well-being. Even though the ADCs in Mizoram are not designed primarily to be agents of socio-economic development (Stuligross, 1999), they are empowered to enact legislations to enhance the standard of living by decentralizing full autonomy on a number of subjects including revenue, village administration, forest (other than reserve forest), urban administration, taxation and markets within their own jurisdictions. But, it seems that they have failed largely to deliver growth and decent standard of well-being. The Chakmas residing in the Chakma Autonomous District Council (CADC) area have lower literacy rate than the Chakmas in Lunglei and Mamit districts which are outside the CADC area (See Table 5). The autonomous district councils in the southern Mizoram were created without having any pre-existing infrastructures and knowledge to manage their own affairs. Delegation of power and functions without building the institutional capacity first has not only failed to eliminate deprivation but rather created places of exploitation, discontentment and widening disparities in distribution of income. Moreover, the longstanding problems of separatist tendencies and inter-ethnic tensions have not retreated with ethnic-based decentralization in Mizoram.

Ethnic-based political decentralization in a multi-ethnic region like Mizoram has largely failed to protect the identity of smaller or microscopic tribes. It is reported that smaller tribes the Brus, the Paites and the Hmars are also demanding some form of autonomy within the state (Haokip, 2020). Autonomy movement and inter-ethnic problem did not dissipate with the creation of autonomous councils for a particular tribe. Territorial fragmentation and cultural segmentation along ethnic lines have adversely affected the process of territorial integration and the efficiency of development planning in a small underdeveloped state like Mizoram. A shift in approach from ethnic-based to local development-based decentralization may be advocated to ameliorate poverty in minority areas (see Barca et al. 2012; Pugalis & Gray, 2016). As a decentralized form of regional planning, place-based approach demands inclusive participation of local population to accommodate ethnic minorities in the overall development process (Markusen, 1983).The approach also encourages the entire process of planning, execution and monitoring of local and regional development to be implemented along planning regions rather than administrative areas. This would enhance the well-being of the local population through establishment of strong and efficient regional development institutions, identification of assets and untapped potentials, and mobilization of various stakeholders in identification of growth strategies. At the same time, effective implementation of place-based approach of regional development requires provision and strengthening of basic infrastructures including transport and communication networks, education and health infrastructures.

With adequate investment from outside, the remote underdeveloped southern Mizoram has huge potential to become the gateway of not only Mizoram but also for the entire Northeast India. The inherent problem of the region—its remoteness and ‘locational dependency’ could be translated into investment gateway by opening the closed international borders with Myanmar and Bangladesh. Lately, initiatives have been taken by the central and state governments to translate the region’s untapped potential through an ambitious Indo-Myanmar bilateral project Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project (KMTTP). According to the government of India, the KMTTP which is one of the most important components of the ‘Look East Policy’ (now renamed Act East Policy) “aims to provide connectivity between India and Myanmar from ports on India’s eastern sea board to Myanmar’s Sittwe Port and further to North East India through Myanmar…to facilitate movement of goods” (GoI 2016:1). The significance of the Kaladan project is that it will enable the entire landlocked Northeast India to access to sea port in Myanmar through southern Mizoram. The initiatives taken to facilitate Indo-Bangladesh border trade including establishment of Trade Facilitation Centre (TFC) at Tlabung town and Integrated Check Post (ICP) at Kawrpuichhuah on the banks of the Indian side of Khawthlangtuipui or Karnaphuli River has also potential to revive the economy of the underdeveloped western part of Mizoram. The new emphasis on ‘developmental regionalism’ may change the economic geography of the south with investment in infrastructure and border trade. At the same time, without provision of other basic sectors of development, it may cause more impairment to the already underdeveloped and backward tribes.

Conclusion

The present study is broadly divided into two sections – quantitative analysis of social well-being of tribal communities in rural Mizoram and critical analysis of the relationship between inequality, autonomy movement and the working of decentralised governance from regional development perspective. The objective well-being of the ethnic minorities living in the border and remote southern parts of the state is found to be lower than the dominant Lusei speakers in the north. On the contrary, the subjective measure of well-being shows that all minorities except the Chakmas are more satisfied than the Lusei speakers in their standard of living. The Chakmas are not only the least satisfied community but also the least ranked community in the ranking of objective well-being. The low objective well-being of the southern tribes may be attributed to their late entry into development process, locational disadvantages, lack of investment and failure of the state and district councils to deliver basic infrastructures and services.

Tribes are not equal, but segmented culturally, socio-economically and are disparately colonised and discriminated. The peripheralization of the southern tribes in Mizoram has rooted in the unequal process of modernization during the colonial period. The formation of ethnic-based autonomous councils in the post-Independent period has not only failed to raise the low standard of living of the southern tribes but also increased the cultural distance between various communities. Moreover, imbalance in sharing of resources and power within the autonomous regions develops a general feeling of marginalization among the lesser communities which have accentuated their discontentment towards the dominant tribes. The prevailing ethnic problems may be tackled through place-based regional development approach which underlies enhancement of unique capacities of regions through provision of standard infrastructures including transportation and communication networks, markets for rural products, quality education as well as healthcare infrastructure and services. Recently, the government of India is unlocking the international borders through which goods, people and ideas will be flooded soon to the isolated and backward region. This is believed to affect the region’s economy, well-being and ethnicities of the southern tribes in one way or another.

Notes

The Mizos can be classified into two broad groups – the Duhlian speaking Lusei and the non-Lusei communities like the Mara, the Lai, the Paihte, and the Hmar who speak both Duhlian and their own language or dialect. The Duhlian speakers comprise more than 70 per cent of the total population of the state.

The Chakmas are the second largest linguistic communities Mizoram. The Mizos considered their rapid population increase in Mizoram, from 255 in 1911 to 17,497 in 1961 as per Census of India, as a demographic threat and many of them were pushed out to other states like Arunachal Pradesh and Assam (Hluna, 2001). Like the Chakmas, the Bru population has also increased rapidly from 51 in 1951 to 32,149 in 2011. In 1997, an inter-ethnic conflict between the Mizo and the Bru has resulted in mass outmigration of 35,000–40,000 Bru population from Mizoram to neighbouring state of Tripura (Roluahpuia 2018).

References

Alesina, A.F., Michalopoulos, S., & Papaioannou, E. (2012). Ethnic inequality. NBER WP 18512, CEPR Discussion Paper 9225.

Arshad, . (2019). Rehabilitation of displaced tribes in North East India: A case study of Reang Tribe in Mizoram. International Journal of Applied Social Science, 6(4), 906–917

Ballas, D., & Dorling, D. (2013). The geography of happiness. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell, & A. C. Ayers (Eds.), Oxford handbook of happiness. (pp. 465–481). Oxford University Press.

Barca, F., McCann, P., & Rodriguez-Pose, A. (2012). The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. Journal of Regional Science, 52(1), 134–152

Baruah, S. (1989). Minority policy in the North-East: Achievements and dangers. Economic and Political Weekly, 24(37), 2087–2091

Bhalla, A. S., & Luo, D. (2013). Poverty and Exclusion of Minorities in China and India. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bhatia, L. (2012). Education and Society in a Changing Mizoram: The Practice of Pedagogy. Routledge.

Bhaumik, S. (2004). Ethnicity, ideology and religion: Separatist movements in India's Northeast. In S.P. Limaye, M. Malik & R.G. Wirsing (Eds.), Religious radicalism and security in South Asia (pp. 219–244). Honolulu: Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies.

Chakma, P. (2009). Mizoram: Minority report. Economic and Political Weekly, 44(23), 20–21

Chakma, S. B., & Gogoi, S. (2018). The Bru-Mizo Conflict in Mizoram. Economic and Political Weekly, 53(44), 59–61

Chakraborty, A. S. (2011). Educational policies and social exclusion: A case study of Chakma tribes in Mizoram. Social Action, 61(3), 274–284

Cooke, M., Mitrou, F., Lawrence, D., Guimond, E., & Beavon, D. (2007). Indigenous well-being in four Countries: An application of the UNDP’s Human Development Index to Indigenous Peoples in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 7(9), 20

Cornell, S. E. (2002). Autonomy as a source of conflict: Caucasian conflicts in theoretical perspective. World Politics, 54(2), 245–276

Dai, Q., Ye, X., Wei, Y. D., Ning, Y., & Dai, S. (2018). Geography, ethnicity and regional inequality in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China. Applied Spatial Analysis, 11, 557–558

Dufty-Jones, R., & Wray, F. (2013). Planning regional development in Australia: questions of mobility and borders. Australian Planner, 50(2), 109–116

Duncan, C. R. (2007). Mixed Outcomes: The Impact of Regional Autonomy and decentralization on Indigenous Ethnic Minorities in Indonesia. Development and Change, 38(4), 711–733

Dunning, H., Williams, A., Abonyi, S., & Crooks, V. (2008). A mixed method approach to quality of life research: A case study approach. Social Indicators Research, 85, 145–158

Epprecht, M., Müller, D., & Minot, N. (2011). How remote are Vietnam’s ethnic minorities? An analysis of spatial patterns of poverty and inequality. Annals of Regional Science, 46, 349–368

Gassah, L. S. (1997). Autonomous District Council. Omson Publications.

Government of India (GoI). (2016). Reply to unstarred question No. 498. New Delhi: Rajya Sabha Secretariat. Details available at https://www.mea.gov.in/rajya-sabha.htm?dtl/26708/Question_No498_Transport_Project_Between_Mizoram_And_Myanmara.

Greyling, T. (2013). A composite index of quality of life for the Gauteng city-region: A principal component analysis approach. Occasional paper 07, The Gauteng City-Region Observatory, South Africa.

Grindle, M. S. (2007). Local governments that perform well: Four explanations. In G. S. Cheema & D. A. Rondinelli (Eds.), Decentralizing governance: Emerging cncepts and practices. (pp. 56–74). Brookings Institution Press.

Hale, H. (2004). Divided we stand: Institutional sources of ethnofederal state survival and collapse. World Politics, 56(2), 165–193

Haokip, T. (2020). Making a case for the formation of regional councils within Sixth Schedule area. In A. Pankaj, A. Sharma & A. Borah (Eds.), Social sector development in North-East India. Sage India.

Hellburn, N. (1982). Geography and the quality of life. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 72(4), 445–456.

Hluna, J. V. (2020). Chakma homeland: Chittagong Hill Tracts. Fraser Media & Publication.

Hnialum, R. T. (2010). Road to lai autonomous district council. Lawngtlai: Baptist Printing Press.

Kauzya, J. M. (2007). Political decentralization in Africa: Experiences of Uganda, Rwanda and South Africa. In G. S. Cheema & D. A. Rondinelli (Eds.), Decentralizing governance: Emerging concepts and practices. (pp. 75–91). Brookings Institution Press.

Khobragade, V. (2010). Ethnicity, insurgency and self-determinaion: A dilemma of multi-ethnic state: a case of North-east India. The Indian Journal of Political Science, 71(4), 1159–1174

Kijima, Y. (2006). Caste and tribe inequality: Evidence from India, 1983–1999. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54(2), 369–404

Knox, P. L. (1975). Social well-being: A spatial perspective. Oxford University Press.

Kolas, A. (2017). Framing the tribal: Ethnic violence in Northeast India. Asian Ethnicity, 18(1), 22–37

Kuhn, M. (2015). Peripheralization: Theoretical concepts explaining socio-spatial inequalities. European Planning Studies, 23, 367–378

Lalfakzuala, J. K. (2016). Ethnicity and autonomy: Unending political process in Mizoram. Social Change and Development, 13, 46–54

Lawmsanga. (2010). A critical study on Christian mission with special reference to Presbyterian Church of Mizoram. Ph.D Thesis, University of Birmingham.

Loh, F. K. W. (2017). Ethnic diversity and the nation state: From centralization in the age of nationalism to decentralization amidst globalization. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 18(3), 414–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2017.1346165

Lymperopoulou, K., & Finney, N. (2017). Socio-spatial factors associated with ethnic inequalities in districts of England and Wales, 2001–2011. Urban Studies, 54(11), 2540–2560

Marans, R. W., & Stimson, R. J. (Eds.). (2011). Investigating quality of urban life: Theory, methods, and empirical research. Springer.

Markusen, A. (1983). Regions and regionalism. In F. Moulaert & P. S. Wilson (Eds.), Regional analysis and the new international division of labor. (pp. 33–56). Kluwer Nijhoff.

McCann, P. (2020). Perceptions of regional inequality and the geography of discontent: Insights from the UK. Regional Studies, 54(2), 256–267

Morrison, P. S. (2007). Subjective wellbeing and the City. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 31, 74–103

Morrison, P. S. (2011). Local expressions of subjective well-being: The New Zealand experience. Regional Studies, 45(8), 1039–1058

Nag, S. (2001). Tribals, rats, famine, state and the nation. Economic and Political Weekly, 36(12), 1029–1033

Nicoletti, G., Scarpetta, S., & Boylaud, O. (2000). Summary indicators of product market regulation with an extension to employment protection legislation. Economics Department Working Papers No. 226, OECD.

North Eastern Council (NEC). (2008). North Eastern Region Vision 2020. New Delhi: Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region.

Oktay, D., & Rustemli, A. (2011). The quality of urban life and neighborhood satisfaction in Famagusta, Northern Cyprus. In R. W. Marans & R. J. Stimson (Eds.), Investigating quality of urban life: Theory, methods, and empirical research. (pp. 233–250). Springer.

Pacione, M. (1982). The use of objective and subjective measures of quality of life in human geography. Progress in Human Geography, 6(4), 495–514

Pacione, M. (2003). Quality-of-life research in urban geography. Urban Geography, 24(4), 314–339

Parry, N. E. (1932). The Lakhers. MacMillan.

Patnaik, J. K. (2017). Autonomous District Councils and the Governor’s Role in the Northeast India. Indian Journal of Public Administration, 63(3), 431–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019556117720594

Paul, D. (2013). Education and Chakmas in India. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing.

Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2007). What kind of local and regional development and for whom? Regional Studies, 41(9), 1253–1269

Pillai, S. K. (2002). Three matryoshkas ethnicity, Autonomy and governance. Faultlines Writing on conflict and resolution, 10.

Pugalis, L., & Gray, N. (2016). New regional development paradigms: An exposition of place based modalities. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, 22(1), 181–203

Rist, G. (1980). Basic questions about basic human needs. In K. Lederer (Ed.), Human needs : A contribution to the current debate (pp. 233–253). Cambridge, Mass: Oelgeschlager, Gunn & Hain.

Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Ezcurra, R. (2010). Does decentralization matter for regional disparities? A cross-country analysis. Journal of Economic Geography, 10(5), 619–644

Roluahpuia, . (2016). Ethnic tension in Mizoram: Contested claims, conflicting positions. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(29), 21–25

Roluahpuia. (2018). The Bru conundrum in North East India. Economic and Political Weekly, 53(17), 16–18.

Roy Burman, B. K. (1970). Census of India 1961: Demographic and Socio-economic Profiles of the Hill-Areas of North-East India. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General of India.

Saitluanga, B. L. (2014). Spatial pattern of urban livability in Himalayan region: A case of Aizawl City India. Social Indicators Research, 117(2), 541–559

Saitluanga, B. L. (2017). Himalayan quality of life: A study of Aizawl city. Springer.

Seymour, R., & Turner, S. (2002). Otonomi daerah: Indonesia’s decentralisation experiment. New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, 4(2), 33–51

Shucksmith, M., Cameron, S., Merridew, T., & Pichler, F. (2009). Urban-rural differences in quality of life across the European Union. Regional Studies, 43(10), 1275–1289

Singh, A. (2008). Ethnic diversity, autonomy, and territoriality in Northeast India: A case of tribal autonomy in Assam. Strategic Analysis, 32(6), 1101–1114

Smith, D. M. (1996). The quality of life - human welfare and social justice. In I. Douglas, R. Huggett, & M. Robinson (Eds.), Companion encyclopedia of geography-The environment and humankind. (pp. 772–790). Routledge.

Son-Doerschel, B. (2013). The making of the Zo: the Chin of Burma and the Lushai and Kuki of India through colonial and local narratives 1826–1917 and 1947–1988. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London.

Stuligross, D. (1999). Autonomous councils in Northeast India: Theory and practice. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 24(4), 497–525

Van Kamp, I., Leidelmeijer, K., Marsman, G., & De Hollander, A. (2003). Urban environmental quality and human well-being: Towards a conceptual framework and demarcation of concepts: A literature study. Landscape and Urban Planning, 65(1–2), 5–18

Wang, D., & He, S. (2016). Introduction. In D. Wang & S. He (Eds.), Mobility, sociability and well-being of urban living. (pp. vii–xiv). New York: Springer.

Wang, F., & Wang, D. (2016). Place, geographical context and subjective well-being: State of art and future directions. In D. Wang & S. He (Eds.), Mobility, sociability and well-being of urban living. (pp. 189–230). New York: Springer.

Xaxa, V. (2008). State, society, and tribes: Issues in post-colonial India. Pearson Longman.

Xaxa, V. (2011). The status of tribal children in India: A historical perspective. IHD - UNICEF Working Paper Series Children of India: Rights and Opportunities Working Paper No. 7. New Delhi: UNICEF.

Funding

This work was funded by the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi, India [Grant reference F.No.:02/301/ST/2016- 17/RP]. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saitluanga, B.L., Hmangaihzela, L. & Lalfakzuala, J.K. Social Well-being, Ethnicity and Regional Development in Mizoram, Northeast India. GeoJournal 87, 3277–3289 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10436-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10436-z