Abstract

This article assesses the manifestations of violence in Nigeria’s 2019 general elections, focusing on trend and spatial dimensions. The article also engages three methodological concerns against most academic studies on electoral violence in Nigeria and beyond. First, research in this area are dominated by extensive narrative, which often reduces quantity of electoral violence in Nigeria to politicised (conflicting, speculative and unverifiable) aggregate data on fatalities. Second, the rising quantification of electoral violence in Nigeria are dominated by perception surveys with little efforts to reconcile them with actual records. Third, large-n studies on violence recorded around elections in Africa are proliferating with sophisticated quantification techniques, which hardly accommodate country-specific details. In contrast, this study observed 2177 incidents of conflict recorded in Nigeria during the period of the elections, and extracted 275 cases of electoral violence for analysis. These data allow us to re-examine the prevailing periodisation of electoral violence in the literature, which ignored violence during inter-election periods. This study also identifies the national distribution and subnational concentration of the violence. These are relevant to guide policy research, advocacies, decisions and security preparedness for peaceful election in Nigeria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Violence is one of the recurrent features of Nigeria’s electoral history and democratic journey since independence in 1960 (Diamond 1988; Hamalai et al. 2017; Joseph 1991; Omotola 2010a; Osaghae 2011; Oyediran et al. 1997; Maier 2000). Nigeria is not unique in this case; many other developing democracies and particularly African countries such as Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, Uganda and Zimbabwe have been marked as major hotspots of electoral violence (Basedau et al. 2007; Collier 2010; Goldsmith 2015; Matloa 2010; Omotola 2011). The situation remains alarming in the case of Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, where electoral crisis has continued unabated under the fourth republic beginning from 1999 (Angerbrandt 2018; Campbell 2010; Hamalai et al. 2017; Omilusi 2017; Verjee et al. 2018; Omotola 2019; Omotola and Nyuykonge 2015). Despite the weight of its threats to democratic participation, competition and legitimacy, electoral violence would appear not to have been given adequate attention by all relevant stakeholders in Nigeria, including aspirants, contestants, electorates, electoral officials and observers. It is often ignored, underestimated, overlooked, misrepresented, politicised or swept under the carpet by policymakers. Only key actors in the opposition, portraying themselves as victims (though not always the case as opposition too can deploy violence in their quest to wrestle power), usually raise critical eyebrow about the tendency.

Although there is a growing number of studies on various aspects of electoral violence in Nigeria, including causes, characteristics, consequences and control (Diamond 1988; ICG 2014; Omilusi 2017; Omotola 2009, 2010b; Onapajo 2014; Onwudiwe and Berwind-Dart 2010). However, most of them reduced empirical research on the subject to journalistic stories of violence with various qualitative techniques. The commonest element of quantification in the extant literature on electoral violence in Nigeria is aggregate data on fatalities, given by media, government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), which are often conflicting and difficult to verify (Angerbrandt 2018; Animashaun 2015; Bekoe 2011; Ezeibe 2020; Onimisi and Tinuola 2019). This set of studies often fall victim of politics of data control, which involves a tendency to underestimate or overestimate the threats of electoral violence by various stakeholders. They often rely on limited incidents of violence before, during and/or after elections, in most cases indiscriminately, and consider it as adequate sample to draw generalisation that are unlikely to support reliable trend and spatial analysis and forecast (Omilusi 2017; Onapajo 2014; Onwudiwe and Berwind-Dart 2010).

Some quantitatively advanced studies on the subject have resorted to sampling and surveying of public perception and expectation of violence during and after elections in Nigeria (Bratton 2008; Abdul-Latif and Emery 2015; Igwe 2012). This method offers disaggregate data to assess threat matrixes, including spatial analysis, and is increasingly becoming relevant in forecasting electoral violence during and after election in the country. Hence, the Youth Initiative for Advocacy, Growth and Advancement (YIAGA) and Clean Foundation among other non-governmental organisations (NGOs), media outlets and government agencies like the Electoral Institute (TEI), the research arm of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) have increasingly adopted this pre-emptive model to study electoral violence (see TEI 2019; 2020, CLEEN Foundation 2019, 2020). Afrobarometer, Gallup, and NOI Poll also offer relevant data in this regard. However, this set of studies focused more on probability than actual violence. Moreover, little or no efforts have been made to bridge the gap between expected level of violence and the actual incidents of violence recorded. Besides, it is barely suitable or used to study pre-election violence.

Finally, there is an emerging body of literature that employed sophisticated quantitative techniques to study electoral violence in Africa and beyond. They use various databases to assess actual trend of violence as well as the correlation with election period and causal factors in Africa (Goldsmith 2015; Benn et al. 2010; Bekoe and Burchard 2017; Daxecker 2014; Hafner-Burton et al. 2018; Salehyan and Linebarger 2014). This method offers better trend and spatial analyses of electoral violence in the region. However, most of the studies in this category focused on large number of elections and countries, which often rob them of insight into specific nature, patterns, threats and dynamics of electoral violence. In many cases, they provide correlation between election period and violence, which does not necessary amount to electoral violence as their conclusions always tend to suggest. Nevertheless, there are few related studies mostly commissioned by government institutions or NGOs on violence during specific election in Nigeria that have used self-compiled data for trend and/or geospatial analysis (SBM Intelligence 2019; National Human Rights Commission of Nigeria 2015). Yet, most of these analyses are victims of inadequate periodisation, given how they failed to properly account for inter-election period in Nigeria’s general elections.

Against this background, this study assesses the manifestations of violence in Nigeria’s 2019 general elections, with special attention on trend and spatial dimensions, while addressing some of the highlighted concerns against most academic studies on quantification of electoral violence in the country. In this process, this article address the following questions: how threatening or violent were Nigeria’s 2019 general elections? How was the violence and casualties distributed across the country? Or where were the hotspots or concentrated locations of the violence? And when was the most alarming period in the electoral process? These questions are important to determine the alarming period in the election processes and associated hotspots of violence in Nigeria. It is also significant to predict future patterns of electoral violence and how to prepare the appropriate institutions and strategies to maintain law and order during this period in the country.

The paper is organised into four sections. The first focuses on our clarification of the concept of election and ‘periodisation’ of general elections in Nigeria: pre-election, election, inter-election and post-election periods. This is important not only to clarify observable mix-ups in the usage of these typologies in the extant literature on the subject, but also because of the peculiarities of the ordering of elections in Nigeria along the federal structure. This makes it possible to locate all observable incidents in their right domain/period. The second deals with data and methods for the study. The analytical fulcrum of the paper comes up in section three. Specifically, it presents findings on trend and spatial analysis of electoral violence in Nigeria’s 2019 general elections. The final section recaps the central arguments and findings of the paper, underscoring its research and policy implications.

Problematisation and periodisation of election in Nigeria

Electoral violence is a form of political violence which is linked to the process of choosing leaders and/or representatives through voting. The connection between violence and election is defined by nature of the activities, motives, actors, targets, timing and context. Höglund (2009) observed that electoral violence has been used generally in two strands of research. The first approach considered electoral violence as a sub-set of activities in a larger political conflict. In this case, research attention is often focused on trend of ethno-communal violence and security environment of elections. Accordingly, a growing number of studies have explored the correlation between election period and armed conflicts in Africa (Cheibub and Hays 2017; Goldsmith 2015; Salehyan and Linebarger 2014). The second approach sees electoral violence as the ultimate kind of electoral fraud, that is, ‘clandestine efforts to shape election results,’ including ballot rigging, vote buying, and disruptions of the registration process (Höglund 2009). There is a significant body of literature on Nigeria in this area, although they are dominantly qualitative in analytical-orientation (Omotola 2009; Omilusi 2017; Onapajo 2014; Onwudiwe and Berwind-Dart 2010).

Although election violence and its meaning are not unique in Nigeria, the official meaning of the concept in the country is relevant from a legalistic perspective. Sections 96 and 131 of the Nigerian Electoral Act (2010) offer an insight into what constitute electoral violence in Nigeria. In this consideration, electoral violence connotes direct or indirect use of threat or force with the aim of preventing an aspirant from contesting or compel a person to support or reframe from supporting a candidate during campaign, to vote or reframe from voting during election, and on account of choice made during these periods thereafter. The Act considered that election is threatened by directly or indirectly inflicting or threatening minor or serious injury, damage, harm, loss, abduction, duress, fraudulent device or connivances aimed at preventing free will or compel, induce or prevail over the free will of a voter or contestant. Denying or demobilizing a contestant campaign assets or general capabilities for mobilising political support, such as media and vehicle are criminalised in Nigeria as threatening to the election (Federal Government of Nigeria 2010).

From the foregoing, defining electoral violence seems less problematic as its indicators are well spelt out. However, defining election period in Nigeria is not an easy task, from where a large n-study with focus on multiple elections and countries are likely to run into trouble. Generally, election is divided into pre-election, election and post-election periods. Of these categories, election period is the most constant of all, because election dates are usually fixed. The same cannot be said about pre-election and post-election periods. The common trend in the literature is to select one or two years, or between one and six months for assessment as pre or post-election periods; and a day or month as election period (Bekoe and Burchard 2017; Cheibub and Hays 2017; Daxecker 2014; Hafner-Burton et al. 2018; Salehyan and Linebarger 2014). Although these typologies are generally appealing in large n-studies, they are largely dictated by researcher’s convenience with little or no recourse to context specific details and the consequences are not always accounted for in the final analysis.

As a federal system, Nigeria’s general elections usually cover federal/national and state elections, with both executive and legislative elections taking place the same time, from where two different Saturdays mostly two weeks apart are always fixed officially as election period. This questions the logic of a day or a month reductionism of election period and suggests the need to take note of inter-election period. It is also important to note that election days are fixed and unfixed at will in Nigeria. For instance, in January 2018, INEC released a 2019 General Elections’ timetable that fixed Presidential and National Assembly (federal) elections on February 16, 2019 and Governorship and State House of Assembly (state) elections on March 2, 2019. On February 16, 2019, the day the federal elections were originally scheduled to hold, however, INEC postponed federal elections to February 23, 2019 and the state elections to March 9, 2019 (Omotola 2019). Similar situation was recorded in the 2015 General Elections in Nigeria. In some cases, voting also spilled into second day of election in few pulling units, due to logistic challenges such as late arrival of officials and delivery of materials, as well as overwhelming voters’ turnout and disruption, of which their record is difficult to come by (see e.g. BBC 2019). Besides, several elections were declared inconclusive, leading to several rerun elections. Amidst these, there are six states (Anambra, Bayelsa, Edo, Ekiti, Kogi, Ondo and Osun states) that are exempted from the general gubernatorial elections, given their unique dates for such, although their State House of Assembly elections conform with the general date. These among other things complicate any attempt to define election periods in Nigeria with absolute precision and mutually exclusive dates.

It is against the foregoing background that this study carefully approached election periodisation and adopted the following as summarised in Table 1. August 17, 2018 is adopted as the beginning of pre-election period. The date is selected being the date that INEC officially flagged off activities for the 2019 General Elections. The scope of pre-election period covers the period for the conduct of party primaries and resolution of disputes arising from such activities between August 18 and October 7, 2018; campaigns for federal and state elections that commenced on November 18 and December 1, 2018 respectively, and both ended 24 h to the day of each of the elections (INEC 2018). It is important to note that Osun State gubernatorial election fall within this period and may cause spurious effect on what is nationally termed pre-election violence in this consideration.

The election period covers the two official dates for both the federal and the state elections. There were several supplementary elections where INEC cancelled voting or declared them inconclusive, which also affect generalised conception of post-election period. This is mostly applicable to federal legislative elections and gubernatorial elections. In this connection, this study examined a major phenomenon of inconclusive gubernatorial elections that affected six states (Adamawa, Bauchi, Benue, Kano, Plateau and Sokoto States) on March 9 and reran on March 23, 2019. We decided to ignore cases where voting spilled to second day. Beside lack of access to comprehensive data on these cases, their exclusion is also necessitated by the need to clearly define inter-election period, which is generalised in the first case and adjusted to the specific context of the second case to avoid overlapping with post-election period. In the absence of official definition of post-election period, this study adopts six months after the state elections, from where the second inter-election period is deducted for the affected states. This period offers substantial latitude to capture reactions to the outcomes of some of the election tribunals. It is noteworthy however that the last day of post-election period, in this consideration, is about two months away from the gubernatorial elections of Bayelsa and Kogi States, from where some spurious effects can also creep to influence the final analysis. In view of these, this study generally covers 389 days between 2018 and 2019.

Data and methods

There are several possible sources of data on electoral violence in Nigeria. Content analysis of media and NGOs reports is a common resort in the literature on electoral violence in Nigeria. Some studies have used it to compile table of incidents, details of events, locations and fatalities of electoral violence in Nigeria (Onapajo 2014; Orji and Uzodi 2012). However, there are some notable errors that are associated with this method. Although self-compiled data from media reports can be verified, they are often less exhaustive or comprehensive and can be influenced by researcher’s bias and error, with negative implications for the final analysis. Although some NGOs can afford to compile exhaustive and less bias data on electoral violence (independently or from media) with minimum error, most of them release analysed reports of aggregate data with little or no attention for raw and verifiable data as well as methodology (how they arrived at their data).

It is against this background that some databases considerably provide systematically gathered and verifiable data on the subject or related matters. Prominent among these are Armed Conflict Location and Events Data Project (ACLED), Global Terrorism Database (GTD), Major Episodes of Political Violence (MEPV), Social Conflict Analysis Database (SCAD) and UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset. Studies on electoral violence in Africa have generally underexplored GTD and MEPV perhaps because of their restricted focus on violence, while a few of them have utilised SCAD (Daxecker 2014) and UCDP/PRIO dataset (Cheibub and Hays 2017). A growing number of them are however resorting to ACLED (Goldsmith 2015; Bekoe and Burchard 2017). Among these databases, ACLED is the only one that offers prompt data update and has released required data for the period covered at the time this study commenced (September 2019). Apart from being the newest of them, it contains the largest entries of violence on Nigeria and Africa generally in the last two decades. Between January 1, 1997 and September 10, 2019, ACLED documented 74,078 incidents in Africa and 15,022 in Nigeria. It is from these that 2,177 incidents that fell within the period covered as Nigeria’s 2019 General Elections were extracted.

ACLED collects and codes reported information on political violence, demonstrations (rioting and protesting) and select non-violent, politically important events (such as strategic developments event: agreement, arrests, change to group/activity, disrupted weapons use, headquarters or base established, looting/property destruction, non-violent transfer of territory, and other) (ACLED 2019a). Its entries include details like date, year, event type and sub-type, actors and associated actors, interactions, region, country, administrative units, locations, sources, notes, and fatalities. These are important to assess trend, scope, actors, characters, frequency, intensity and geospatial distribution of political violence and non-violent resistance as well as associated countermeasures. Out of these, election related incidents were extracted for selected period. It is important to note that most large-n studies that cover multiple elections and countries often focus on the correlation between social or political conflicts, as generally reported in chosen databases, and election period, rather than screen incident details individually for substantial reflection or connection with election matters (Goldsmith 2015; Bekoe and Burchard 2017; Cheibub and Hays 2017; Daxecker 2014).

Two major methods were employed to screen 2,177 incidents that fall within the scope of this study for their reflection or connection to election. First, entries that involve actors that are in the forefront of the election were extracted for inclusion. In this case, only the electoral management body and political parties are included without further screening on the assumption that all their activities during this period are directed towards elections. The same thing cannot be said of other actors like the security agencies and other state institutions, media, civil society organisations (CSOs) or NGOs and political militias, in the forefront of the election. Entries that involved these among other actors were initially excluded for further scrutiny to ascertain the actual relevancy and filtrate the influence of enduring engagements that does not have direct connection to the subject matter. The second approach for inclusion employed a combination of election-related keywords and details of entry’s note to scrutinise the relevance of incidents. Keywords employed in this consideration include candidate, nominee, contestant, campaign, rally, convention, elect, election, political, party, politician, poll, ballot, vote, voter, voting, commission, collation, declaration, and press briefing or conference. Although the keywords largely informed decision at this stage of inclusion, all entries were carefully examined before the process was finalised.

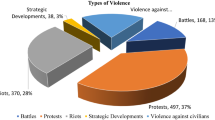

It is against this background that we arrived at 17.4 per cent (379) of the total entries within the period under consideration that qualified as election-related incidents. Table 2 shows that 267 entries qualified as election-related incidents in the first stage of the screening and another 112 entries joined them in the second stage of inclusion. Given that ACLED, however, covered non-violent resistance and other important political events, there is a need to narrow the scope of available data down to election-related violence. This was done by using sub-event type of data entry to screen out peaceful protest, while entries that involved protest with intervention and excessive force against protesters were retained. Relevant strategic developments were also retained. Finally, 104 election-related entries (27.4%) were classified as peaceful incidents and screened out of this consideration, while the remaining 275 entries (72.6%) qualified as violence.

Compared to many other studies on the subject, the incidents of electoral violence covered appears to be significant. Using various reports of NGOs, for instance, Onapajo (2014) was only able to compile 30 incidents of violence in Nigeria’s 2007 elections, which are believed to be more violent than 2019 elections. Although Nigeria’s 2011 elections are widely believed to be the most violent in the fourth republic, at least as at 2019, a commissioned study by Orji and Uzodi (2012) tracked and documented close to 90 incidents. In 2015 elections, National Human Rights Commission of Nigeria (2015) received reports of and documented 60 incidents of election-related violence and 55 fatalities across 22 states in 50 days. Between 14 October 2018 and 20 February 2019, SBM Intelligence (2019) also documented 67 incidents of electoral violence and 233 fatalities across 24 states. However, the report of SBM Intelligence excluded information on data and methodology.

Trend and spatial distribution of electoral violence

No fewer than 275 incidents of violence were recorded in direct connection to Nigeria’s 2019 General elections, which claimed 159 lives. Figure 1 offers trend of the incidents of violence and associated fatalities from pre-election to post-election periods, with disaggregated data for election and inter-election periods circled. Pre-election period appears to be the most violent and deadliest of the election cycle. It accounted for 51.3 per cent of the total incidents of violence and 52.2 per cent of fatalities recorded. On the average, 1 fatality is associated with 1.7 incident of pre-election violence. Moreover, an average of 0.7 incident of pre-election violence and 0.4 fatality were recorded daily in the period. This amounts to approximately 5.2 incidents and 3 fatalities on weekly average, as well as 20.1 incidents and 11.9 fatalities on monthly average.

Election period accounted for 25 per cent of the incidents of violence and 24.5 per cent of fatalities. This is apparently the most violent and deadliest period of the election periods on daily average. The three days of elections accounted for a quarter of incidents of violence and fatalities recorded in 389 days. Averagely, this amounts to 23 incidents per day and 13 fatalities per day. Of these, the state elections of March 9, 2019, was the deadliest in the election-cycle with 15.6 per cent of the total incidents of violence and 13.8 per cent of fatalities recorded. This among others are responsible for many cases of inconclusive and supplementary polls in Nigeria’s 2019 general elections.

At 9.8 per cent of the incident of violence and 8.2 per cent of the fatalities, inter-election period appears to be the least deadly in the trend. It amounts to approximately one incident and 0.5 fatality on daily average, as well as 6.8 incidents and 3.3 fatalities on weekly average. Amidst these, the two-weeks of the first inter-election period (IEP1) is significant, with 1.9 incidents of violence and 0.9 fatality on daily average, as well as 12.5 incidents and 6 fatalities on weekly average. The six months of the post-election period accounted for 13.8 per cent of the total incidents of violence and 15.1 per cent of the fatalities. Therefore, it amounts to 6.3 incidents of violence and 4 fatalities per month, 1.5 incidents and 0.9 fatality per week, as well as 0.2 incident and 0.1 fatality per day.

Figure 2 presents spatial distribution of incidents of violence in Nigeria’s 2019 General Elections. Notably, only Kebbi and Yobe States did not record incident of election related violence. Their enviable record was followed by Gombe, Kaduna and Niger States that had only one incident each, as well as Anambra, Borno, Plateau and Sokoto States that recorded two incidents each. However, Rivers, Awka Ibom and Delta states top the list of the most violent state during the elections, as they collectively accounted for 29 per cent of the total incidents of electoral violence recorded. The top nine most violent states (Rivers, Awka Ibom, Delta, Benue, Bayelsa, Lagos, Kogi, Ogun and Kano) had double-digit incidents that amounted to 55.6 per cent of the total record of electoral violence in the federation, which is made up of 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). Other key hotspots are Oyo, Osun, Edo, Imo, Enugu, Ondo and Taraba States and the FCT.

Figure 3 presents spatial distribution of fatalities of violence during Nigeria’s 2019 General Elections. Beside Kebbi and Yobe States where there was no incident of violence, there were nine states with incidents (Anambra, Bauchi, Gombe, Kaduna, Niger, Osun, Plateau and Sokoto States) without fatality. With one or two fatalities each, Ekiti, FCT, Zamfara, Ebonyi and Kaduna experienced less deadly incidents of violence in relation to Nigeria’s 2019 general elections. However, Rivers, Taraba, Delta and Abia States with double digit fatalities had the deadliest elections in the country in descending order. Kogi, Lagos, Benue, Adamawa, Bayelsa, Akwa Ibom, Borno, Kano and Kastina are other deadly hotspots of violence in Nigeria’s 2019 elections.

As evident in Table 3, North-West geopolitical zone recorded least incidents of violence with about 6 per cent of the total incidents in Nigeria’s 2019 general elections. Both South-East and North-West followed this record with about 10 per cent of the total incidents each. Again, the South-South recorded the highest incidents of violence in the country with about 38 per cent, no thanks to Rivers, Awka Ibom and Delta States that ranked most violent in that order. South-West with 19 per cent and North-Central with 17 per cent of total incidents of violence followed. North-West, South-East and North-Central had the least deadly elections with 9.4 per cent, 10.7 per cent and 12.6 per cent of the total fatalities recorded respectively. South-South and North-East geopolitical zones recorded the deadliest electoral violence with 35 per cent and 20 per cent of the total fatalities respectively.

No fewer than 141 incidents of pre-election violence were recorded in 33 states (except Gombe, Kebbi and Yobe) and the FCT with 83 fatalities recorded in 23 states (except Anambra, Bauchi, Gombe, Kebbi, Nasarawa, Niger, Ogun, Osun, Plateau, Sokoto, Yobe and Zamfara) and the FCT. The pre-election period was most violent in Awka Ibom, Delta and Rivers States where double digit incidents of violence were recorded. Other major hotspots were Osun, Ogun, Bayelsa, Abia, Edo and Benue states as well as FCT, where between eight and five incidents of pre-election violence were recorded. However, only Abia State recorded double digit fatalities in this period. Rivers, Delta, Borno, Kano, Kastina and Bayelsa equally had between nine and five fatalities.

Ten states accounted for all the incidents of electoral violence recorded during the federal elections on February 23, 2019. Amidst these, Rivers State was the most violent and deadliest with 37 per cent of the total incidents and 62.5 per cent of fatalities recorded. Other flashpoints of violence during the elections were Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Delta, Kogi, Lagos, Nasarawa, Osun, Oyo and Zamfara States where between one or two incidents were recorded. Accordingly, two fatalities were recorded in Delta State, and one each in Bayelsa, Kogi, Oyo and Zamfara. However, 16 states accounted for the 43 incidents of violence recorded, while ten states hosted all the fatalities during the state elections on March 9, 2019. Amidst these, Akwa Ibom was responsible for about 28 per cent of the incidents. Other major flashpoints are Kogi, Rivers, Oyo, Ondo, Benue and Enugu. Out of the six states covered for the supplementary elections on March 23, 2019, incidents of violence were recorded in Benue, Kano and Sokoto States and fatality was only recorded in Benue.

Lagos was the most violent state in the first inter-election period, with 24 per cent of all election-related incidents of violence recorded between the federal and state elections. It recorded about one incident every two days of the 13 days. Fifteen other states (Adamawa, Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Borno, Cross River, Delta, FCT, Gombe, Imo, Nasarawa, Ogun, Ondo, Sokoto and Taraba) also recorded one or two incidents of violence during the first inter-election period. However, Taraba, Lagos, Adamawa and Ogun States accounted for all fatalities within this period. One incident of violence was recorded each for Bauchi and Benue States, and one fatality was recorded in Benue, between the date of their inconclusive state elections and that of the supplementary elections.

The 38 incidents of post-election violence on record occurred in 17 states and the FCT. The affected states are Adamawa, Bauchi, Bayelsa, Borno, Edo, Enugu, Imo, Jigawa, Kano, Katsina, Kogi, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Rivers, Taraba and Zamfara. Yet, seven states (Adamawa, Benue, Edo, Kogi, Ogun, Rivers and Taraba) hosted all the 24 fatalities in the post-election period. Amidst these, Taraba state accounted for 58 per cent of the total fatalities with just 5 per cent of the total incidents of violence.

Conclusion

This article contributes to a growing body of knowledge on electoral violence in Nigeria and Africa. It emphasises the enduring importance of single or limited case study (in this case specific election/s in a particular country) on the subject of electoral violence as substantive and complimentary perspective in the age of large-n (multiple elections in multiple countries) analysis. A case study of this kind has the prospects of unveiling many unique and specific details that are hard to accommodate in large-n studies. The limited number of incidents that are examined in this study makes it easier to identify and exclude cases of non-election-related violence as well as peaceful election-related resistances. In this case, this study identifies the imperative need to pay more academic attention to the subject of non-violent resistance in the framework of electoral (conflict) management. This can promote advocacies and desire to consider and adopt peaceful methods of resistance and conflict engagement among political actors that are involved in election.

The country-focus of the paper also makes it possible to address the question of where and when electoral violence occurs. Most large-n studies on electoral violence in Africa does not have the luxury of paying adequate attention to dynamic effects of inappropriate periodisation in the final analyses. They are equally inappropriate to map out sub-national hotspots of electoral violence and less suitable to guide political and security decisions in this consideration. It is the hope of this study that further efforts will be made to explore more unique and specific details about electoral violence, including organisational, strategic, tactical and operational dynamics that are involved. Accordingly, political and security decision-makers and critical stakeholders in Nigeria are likely to benefit more from a study of this kind that will pay attention to all necessary (or selected but relevant, specific and unique) details in assessing patterns of electoral violence over the period of recent democratic journey in the country (since 1999). These are important to aid policy advocacy, political decision and security preparedness for peaceful, periodic, free and fair elections in Nigeria.

References

Abdul-Latif, R., & Emery, M. (2015). FES pre-election survey in Nigeria 2014. Washington, DC.: International Foundation for Electoral Systems.

ACLED. (2019a). Armed conflict location & event data project (ACLED) Codebook. https://acleddata.com (accessed on September 10, 2019).

ACLED. (2019b). Armed conflict location & event data project (ACLED). https://acleddata.com (accessed on September 10, 2019).

Angerbrandt, H. (2018). Deadly elections: post-election violence in Nigeria. Journal of Modern African Studies, 56(1), 143–167.

Animashaun, M. A. (2015). Nigeria 2015 presidential election: The votes, the fears and the regime change. African Journal of Election, 14(2), 186–211.

Basedau, M., Erdmann, G., & Mehler, A. (Eds.). (2007). Votes, money and violence: Political parties and elections in Sub-Saharan Africa. Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

BBC. (2019). Nigeria election 2019: Counting under way, 24 February 2019

Bekoe, D. (2011). Nigeria’s 2011 elections: Best run, but most violent. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace.

Bekoe, D. A., & Burchard, S. M. (2017). The contradictions of pre-election violence: The effects of violence on voter turnout in sub-Saharan Africa. African Studies Review, 60(2), 73–92.

Benn, E., Miguel, E., & Posner, D. N. (2010). Political competition and ethnic identification in Africa. American Journal of Political Science, 54(2), 494–510.

Bratton, M. (2008). Vote buying and violence in Nigerian election campaigns. Afrobarometer Working Paper No. 99.

Campbell, J. (2010). Nigeria: Dancing on the brink. Ibadan: Bookcraft.

Cheibub, J. A., & Hays, J. C. (2017). Elections and civil war in Africa. Political Science Research and Methods, 5(1), 81–102.

Foundation, C. L. E. E. N. (2019). Security threat assessment for 2019 general elections in Nigeria. Abuja: CLEEN Foundation.

Foundation, C. L. E. E. N. (2020). Security threat assessment for 2020 governorship elections in Ondo State, Nigeria. Abuja: CLEEN Foundation.

Collier, P. (2010). Wars, guns and votes: Democracy in dangerous places. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Daxecker, U. E. (2014). All quiet on election day? International election observation and incentives for pre-election violence in African elections. Electoral Studies, 34(June), 232–243.

Diamond, L. (1988). Class, ethnicity and democracy in Nigeria: The failure of the first republic. London: The Macmillan Press Ltd.

Ezeibe, C. C. (2020). Hate speech and election violence in Nigeria. Journal of Asian and African Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909620951208.

Federal government of Nigeria (FGN). (2010). Electoral Act. Abuja: FGN.

Goldsmith, A. A. (2015). Elections and civil violence in new multiparty regimes: Evidence from Africa. Journal of Peace Research, 52(5), 607–621.

Hafner-Burton, E. M., Hyde, S. D., & Jablonski, R. S. (2018). Surviving elections: Election violence, incumbent victory, and post-election repercussions. British Journal of Political Science, 48(2), 459–488.

Hamalai, L., Egwu, S. G., & Omotola, J.S. (2017). Nigeria’s 2015 general elections: Continuity and change in electoral democracy. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Höglund, K. (2009). Electoral violence in conflict-ridden societies: Concepts causes, and consequences. Terrorism and Political Violence, 21(3), 412–427.

ICG (International Crisis Group). (2014). Nigeria’s dangerous 2015 elections: Limiting the violence, Africa Report N°220, 21 November.

Igwe, D. O. (2012). The perception of electoral violence and democratization in Ibadan Oyo State Southwest Nigeria. Democracy and Security, 8(1), 51–71.

INEC. (2018). Time table and schedule of activities for 2019 general elections, January 9.

Joseph, R. (1991). Democracy and prebendal politics in Nigeria: the rise and fall of the second republic. Ibadan: Spectrum Books Ltd.

Maier, K. (2000). This House Has Fallen: Nigeria in Crisis. London: Penguin Books.

Matlosa, K., Khadiagala, G.M., Shale, V. (eds). (2010). When elephants fight: Preventing and resolving election-related conflicts in Africa. EISA.

National Human Rights Commission of Nigeria. (2015). A pre-election report and advisory on violence in Nigeria’s 2015 general elections. Abuja: The National Human Rights Commission of Nigeria, February 13, 2015.

Omilusi, M. (2017). Your vote or your life: Tracking the tangible and intangible dangers in Nigeria’s electoral politics.

Omotola, J. S. (2009). ‘Garrison’ democracy in Nigeria: The 2007 general elections and the prospects of democratic consolidation. Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, 47(2), 195–221.

Omotola, J. S. (2010). Elections and democratic transitions in Nigeria under the Fourth Republic. African Affairs, 109(437), 535–553.

Omotola, J. S. (2010). Mechanisms of post-election conflict resolution in Africa’s ‘new’ democracies. African Security Review, 19(2), 2–13.

Omotola, J. S. (2011). Explaining electoral violence in Africa’s new democracies. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 10(3), 52–73.

Omotola, J. S., Nyuykonge, C. (2015). Nigeria’s 2015 general elections: Challenges and opportunities, ACCORD Policy and Practice Brief (PPB) No. 33; available at http://www.accord.org.za/images/downloads/brief/ACCORD-policy-practice-brief-33.pdf.

Omotola, J. S. (2019). The Challenge of Electoral Management in Nigeria, Special Issue of Kujenga Amani on Perspectives on the Postponement of Nigeria’s 2019 Election, African Peacebuilding Network (APN), Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York; available at https://kujenga-amani.ssrc.org/2019/02/22/the-challenge-of-electoral-management-in-nigeria/

Onapajo, H. (2014). Violence and votes in Nigeria: The dominance of incumbents in the use of violence to rig elections. Africa Spectrum, 49(2), 27–51.

Onimisi, T., & Tinuola, O. L. (2019). Appraisal of the 2019 post-electoral violence in Nigeria. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 4(3), 107–113.

Onwudiwe, E., & Berwind-Dart, C. (2010). Breaking the cycle of electoral violence in Nigeria (p. 263). Special Report: United States Institute of Peace.

Orji, N., Uzodi, N. (2012). The 2011 post election violence in Nigeria. Policy and Legal Advocacy Centre (PLAC).

Osaghae, E. (2011). Cripple giant: Nigeria since independence. Ibadan: John Archers Ltd.

Oyediran, O., Diamond, L., & Kirk-Greene, A. (1997). Transition Without End: Nigerian politics and civil society under Babangida. Ibadan: Vantage Publishers.

Salehyan, I., & Linebarger, C. (2014). Elections and social conflict in Africa, 1990–2009. Studies in Comparative International Development, 50(1), 23–49.

SBM Intelligence. (2019). Mounting Electoral Violence. sbmintel.com.

TEI (The Electoral Institute). . (2019). Report of Security Threat Assessment for 2019 General Elections in Nigeria. Abuja: TEI.

TEI. (2020). Report of security threat assessment for 2020 governorship election in Edo State. Nigeria, Abuja: TEI.

Verjee, A., Kwaja, C., & Onubogu, O. (2018). Nigeria’s 2019 elections: Change, continuity, and the risks to peace (p. 429). Special Report: United States Institute of Peace.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oyewole, S., Omotola, J.S. Violence in Nigeria’s 2019 general elections: trend and geospatial dimensions. GeoJournal 87, 2393–2403 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10375-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10375-9