Abstract

Brisbane is Australia’s third largest city, and capital of the state of Queensland. It has a sprawling urban footprint and impending connections to neighbouring metropolises, said to create a ‘200 km city’. The governing body of Brisbane controls the largest municipality in Australia, with unrivalled opportunity to influence both urban planning and marketing for the CBD and suburbs. Brisbane is home to over one million people, and its population has grown rapidly over the past decades, doubling in the past 40 years. Brisbane represents the quintessential city with an emerging quest for urbanity, both in brand and physical form. The relationships between the city’s urban planning and its branding is not well examined, despite clear entanglement between these two strategies. We use a case-study analysis of both Brisbane City (which is glossed as the Central Business District) and an outer-suburban area, Inala, to interrogate how urban identities and brand are being constructed in relation to their social settings and governance, with particular reference to the importance of city branding and its relationship to planning strategies. The manifestation of branding and relationship to place qualities at the core and on the periphery of Brisbane are examined, with relevance for other rapidly growing, ambitious cities. The focus of Brisbane’s push for urbanity is on the city centre, and is not representative of the typical suburban condition, nor of many cities dominated by suburban forms. An analysis of place brand, planning strategies and resident’s responses to place, from planning, architectural and anthropological perspectives are offered, as an alternative reading of place brand from the marketing dominated approach usually favoured in branding analysis. We make recommendations to incorporate a more complete version of place in the construction of a “genuine” urbanity. We argue that the recognition of resident-centred place identity in place branding will produce more socially sustainable places, as well as more authentic city brands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Brisbane, capital city of the State of Queensland and third largest city in Australia, has for decades languished behind the more populous southern capitals of Melbourne and Sydney in terms of its reputation as a place of culture or innovation. Despite Brisbane’s rapidly growing population, doubling in the past 40 years (ABS 2014) while its urban footprint joins to neighbouring metropolises to create a “200 km city” (Spearitt 2009), it was until relatively recently known by locals and interstate residents alike as a ‘big country town’. Brisbane’s attempts to transform this reputation began decades ago, and the latest version of this is the city government-lead place-branding campaign showcasing Brisbane as a ‘New World City’. This blends marketing with planning, but refers only to the CBD. Since Brisbane hosted the World Expo in 1988, its governing organisations have sought to promote and literally construct a more urban identity, through a process of city-reimaging and a re-configuration of the city centre into a vibrant and attractive urban environment. These branding and planning changes have been little examined; there is far less research on Brisbane’s urban planning history or places than Australia’s southern capitals, perhaps because of the perception that for many years it was unworthy of serious consideration.

The ‘Brisbane’ we write of is the area governed by Brisbane City Council (BCC), the largest local government authority in Australia, administering an area of over 1300 km2 (Brisbane City Council 2013b) (see Fig. 1). This unusually large jurisdiction, with an annual budget of nearly AUD$3 billion (Brisbane City Council 2013c), gives the local government authority power to define and manage branding of both inner city and outer suburban areas, under one governing body (Searle and Minnery 2014), in contrast with most other Australian cities. The greater Sydney area, for example, is made up of numerous of local government authorities, including the City of Sydney, which has jurisdiction over only the small CBD area, and lacks a coherent place branding authority (Kerr and Balakrishnan 2012). We examine the contrast between Brisbane’s core and periphery in terms of planning and branding approaches despite their unity within the BCC governance, which we see as a reflection of the difference in how places are valued differently, and as evidence of the perceived cultural capital of centre contrasted with edge.

The first section of the paper presents how place branding is weighted towards marketing rather than a full engagement with places, and how the selection of place features for branding can be analysed as a political process. We explain how place branding and planning strategies have become complementary in the process of city-reimaging. We then present the research questions and methods, followed by a section focused on the Inala case study as an example of an outer suburb with a strong sense of place. The fourth part focuses on the New World City case study: the production process of the city brand and its impact on the planning strategies in the context of the new City Centre Master Plan.

Where is the ‘place’ in place branding?

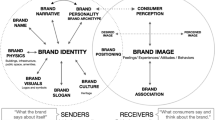

Over recent decades, place branding has been an emerging field of practice and analysis across a multiplicity of disciplines, from marketing and business analysis, to place and urban design (Kavaratzis and Ashworth 2005; Dinnie 2011). Within this diverse field there have been calls for more analysis of the ethics of place branding, and attention being directed towards the increasing application of city branding (Hankinson 2001 p. 129) and it effects, on not only the external audiences to whom a city brand is marketed, but also residents in place (McCann 2009; Insch 2011 p. 153).

Place branding goes beyond place-marketing (Giovanardi et al. 2013 p. 368) creating a unique and persuasive story of place leading to presumed economic benefits through the promotion of places as products for consumption (Cleave and Arku 2014). This requires the presentation of a harmonized place narrative (Pasquinelli 2013) in which discordant or mismatched versions of place can be silenced, ignored or erased (Medway and Warnaby 2014). The political implications of such branding are outlined by Smith (2005 p. 399) who refers to “city-reimaging” as a “deliberate (re)presentation and (re)configuration of a city’s image to accrue economic, cultural and political capital”, stressing the economic benefits that are presumed to flow from branding of places. Colomb and Kalandides (2010) and later Warnaby and Medway (2013), emphasise that the political tensions that arise between diverse stakeholders during the homogenisation and commodification of place qualities in creating a singular place brand are unavoidable.

Place theorists recognise that places are not only comprised of their physical, functional qualities in the present, but also consist of their associations with people, events and histories (Lynch 1960; Agnew 1987; Cresswell 2004). The classic geographic definition of place, proposed by Agnew, states that place is comprised of location, the cartographic description of place; locale, the understood function of a place e.g. as a park or a restaurant; and sense of place, which encompasses the social and emotional meanings associated with a place (1987 p. 28). Similarly, geographer David Harvey stresses place is not only physical, but is constructed and made meaningful only through the social (Harvey 1993 p. 5). The examination of place attachment in people-environment studies overwhelmingly argues that a holistic understanding of place is one where places are “unlike objects” (Russell and Ward 1982 p. 666) and understood as a “whole rather than a succession of parts”. Places carry deep affective meanings (Tuan 1974; Giuliani 1991, 2003), and can entwine with a person’s identity (Proshansky et al. 1983, Cuba and Hummon 1993; Twigger-Ross et al. 2003), their well-being (Atkinson et al. 2012) and feelings of belonging in the world (Read 2000; Lewicka 2010). Place identity—that is the identification a person feel towards an important place—is a key term here describing the deep levels of attachment people can develop to places (Tuan 1974), and the subsequent loss experienced if places change outside their control, or are destroyed (Read 1996).

Place as explained by architects and planners often borrows from geographic definitions, but also attributes high value on the genius loci, spirit of place, and the assertion that successful architecture involves a revealing of the genius loci through architectural interventions that respond to the uniqueness and particular character of any location (Norberg-Schulz 1980). Some schools of thought in architecture and urban planning have sought to build upon the authentic, and the genuine when responding to local audiences, with an emphasis on ‘character’ and existing fabric of places (Lynch 1960; Rowe and Koetter 1978; Alexander et al. 1977). Yet even within these aims, as Jiven and Larkham argue, genius loci, ‘sense of place’ ‘character’ and ‘appearance’ have come to be used interchangeably in urban design (2003 p. 73), thus emphasising the physical place characteristics, while the social and cultural aspects of places recede. Planning for social and cultural sustainability can require lengthy processes of consultation in order to achieve genuine resident participation and influence (Arnstein 1969; Falleth and Saglie 2011), and leads to a multiplicity of meanings for place (Massey 1993; Dempsey et al. 2011) rather than the simplicity of meaning required in branding. Hence, we question, how can place complexity and the place values of citizens, tourists and commercial enterprises alike come to be reconciled within place branding?

Place branding and city design

Architectural writers are frequently critical of banal places or indeed of ‘non places’ (Augé 2008), ‘placelessness’ (Relph 1976) or ‘generic’ places (Koolhaas and Mau 1995). Despite this there is a continued rise of ‘starchitects’ whose designer brand and fame offers a place pulling-power through the commissioning of buildings with global status, which speak less to the specifics of place and more to the importance of brand in design (Haila 2006; Zukin 1992). Knox (2011) argues that ‘starchitects’ buildings provide a physical backdrop of luxury and spectacle (2011, p. 276) and help to denote a place as being part of the club of ‘world cities’ and a centre of global captial. Sydney Opera House, designed by architect Jørn Utzon catapulted both architect and city to world status in 1973, prior to the global trend of iconic buildings. Frank Gehry’s New Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, opened in 1997, had a brief that called for an equivalent to the Sydney Opera House: an iconic building that would sell plane tickets to Bilbao (Jencks 2005 p. 11–12). This focus on the global and iconic (away from the local and authentic), aligns with Julier’s (2005) concept of urban designscapes, in which urban form is used to create a marketable form of symbolic capital which promotes a particular place brand to a world audience.

In contrast to these ‘generic’ (albeit spectacular) places, are Augé’s “anthropological places” (Augé 2008, p. 42) which include essential components of identity, relations and history. These terms give us the ingredients for what we argue is an ‘authentic’ place, where authenticity is defined by alignment with the ‘insider’ understanding of place (Relph 1976). Authentic place does not dictate an obsession with historic physical forms or nostalgia, Devine-Wright (2014) argues that place attachment is dynamic, open to change and that place change is an ongoing process that humans have long coped with. Similarly, Hobsbawm and Ranger argue that traditions undergo constant renewal (1983), but remain authentic when altered by insiders rather than imposed from without. Wang’s (2009) analysis of authenticity in tourism experiences further explains that places become meaningful when they trigger personal resonance in place, provoking what he calls “existential authenticity”. We argue that this person-activity-centred authenticity could be extended to non-tourists who judge place authenticity through their resonant experiences when genius loci is revealed in conjunction with the physical and functional aspects of place.

The goal of branding is to “increase margin, market share, revenue and market value” (Chasser and Wolfe 2010 p. 2) and given that place is ‘not an object’ but a dynamic holistic entity, the most common type of top-down place branding approach (Bennett and Savani 2003) may clash with aspirations for democratic participation in planning (Insch 2011). The balance of power in place branding, and accompanying urban regeneration, is in need of further exploration including qualitative—anthropological—accounts of place in order to better understand the social and cultural in place branding.

The politics of place branding

Places bands are political creations orchestrated through the promotion of particular place characteristics or associations and the forgetting of others (Madgin and Rodger 2013). The meanings of place vary between the multiple different people and groups who experience it, leading to diverse values and associations with place. These differences in place values are at the centre of some of the most fundamental disagreements of our current age and times past. The contrasting opinions between environmental and economic worth of places, for example, epitomise the differing political meanings possible with respect to one place.

Place branding theorists readily admit that branding is redolent with ambiguity and paradox (Brown et al. 2013), but municipalities nevertheless press on with branding their cities through careful imagery and punchy slogans that cannot, and do not pretend to reflect the complexity of places as a whole. While this is unavoidable (Insch 2011, Pasqunelli 2013, Brown et al. 2013), the consequences and specific nature of these disjunctures on the contemporary city are under-examined. What is aspects of place are emphasised in branding and why?

City brands deliberately emphasise what their creators imagine to be attractive qualities, sometimes with unintended consequences. Madgin and Rodger’s (2013) account of Edinburgh’s self-created ‘myth’ of being a cultural city, maintained over generations, and the consequences for its 20th Century de-industrialisation, demonstrate the importance of cities not believing their own hype. Kipfer and Keil (2002) examined Toronto’s beautification strategies in an effort to become more competitive utilising planning and design, while Rousseau (2009) examined the efforts of ‘loser cities’ to redefine themselves to catalyse economically regeneration, emphasising the processes of place commodification. Some place branding proponents conflate urban regeneration of the city’s physical fabric with the renewal of the brand marketing of a place, under the catch-cry of place branding (Bennett and Savani 2003), which is seldom how planners imagine urban regeneration processes or planning policy development to work. Yet the Edinburgh example demonstrates that city branding can and does affect planning decisions and ought to be carefully considered.

Branding is affected by political constraints, but similarly politics responds to place images put forward through branding, for example tragedies in some places receive more attention than similar events in others (see Kariel and Rosenvall 1984). In order to host political events, be influential in world affairs, a place must be known and understood on a global level. A ‘global city’ is one which is hyper-connected socially, culturally and economically with other global locations. While Brisbane considered as a ‘beta’ global city (behind the two ‘Alpha++’ cities of London and New York and numerous ‘Alpha+’ and ‘Alpha’ cities) (GaWC 2012) the branding of Brisbane as a New World City aims to speak to, and ascend, this global scale. Brisbane’s success in bidding for and then hosting the G20 World Leaders forum in 2014, was incorporated into marketing and city branding demonstrating that both economic and political power are intrinsic to place.

Research aims

From the recognition of the tension between place complexity and a need for clear branding message, Brisbane’s current city branding presents the opportunity to examine several aspects of place branding: the internal differences within a brand area and how these are reflective of perceptions of core (CBD) and periphery (suburbs); the lack of alignment between aspects of place identity (as experienced by residents) and place branding (as promoted through place brand marketing); and how branding can influence not only perceptions of city officials, but their planning teams, so that branding becomes an agent shaping the physical form of the city to align with branding image. We come to this analysis from the disciplines of planning, architecture and anthropology, deliberately taking a place-based rather than a marketing or promotion approach, in order to analyse ultimately, how much ‘place’ is really present within the current juggernaut of place branding activities in Brisbane and by extension elsewhere.

In order to answer this question fully this article has the following objectives:

-

Analyse the production process of the New World City brand;

-

Analyse the integration of brand elements by urban stakeholders involved in Brisbane City Council’s new City Centre Master Plan;

-

Put into perspective this process with other processes of place-identity development in Brisbane.

We examine Brisbane in two parts, the CBD, which is glossed for the whole city in branding strategies, and the suburban, peripheral area of Inala which is both geographically remote from the centre, and invisible in the main branding strategy, but which has a brand identity of its own for local audiences. These examples explain how branding can be at once highly influential over planning instruments and imagery, and almost irrelevant to the lives of everyday citizens who relate to the city and its parts in more local ways. We question how a place brand covering such diverse geographies can become authentic, and align with or contribute to ‘sense of place’, and what this might mean for audiences, brand creators, residents and planners.

Lucarelli and Berg’s (2011 p. 18) review of city branding research identifies three main research domains of city branding: firstly, the production of city brands, focusing on the management of brands and brand governance; secondly, the uptake and success of city branding; and thirdly, critical analysis of city brands and their effects on the economic, social and cultural life of cities. In this paper we contribute an analysis relating to the first and third points, an examination of the production of branding; and a critical analysis of the brand in context of the city as a place rather than a brand alone. While there have been numerous case studies of the place specific-branding strategies, there have been relatively few that look at a city such as Brisbane, and examine the holistic effects of its branding strategies and some of the impacts upon its citizenry. We address Cleave and Arku’s (2014) recent analysis of place branding and the impact it has upon people in place, through a specific analysis of centre versus periphery in Brisbane.

Methods

Our analysis uses qualitative methods to establish the meanings of place both in the CBD and Inala. In the CBD case, we examined the effect of place branding strategies on attitudes, and planner’s perceptions of the importance of branding on their work, as well as an analysis of the place branding documents produced by Brisbane City Council e.g. The New City Centre Master Plan, marketing documents, and websites. This has included the City Centre Master Plan itself (BCC 2012), Ideas Fiesta: Wrap Up Report (BCC 2013a), Planning for the Future: The Draft New City Plan (2013d), Eastern Neighbourhood Corridor Plan (2014a), Visit Brisbane website (2014b), Brisbane Marketing website (2014c), Brisbane City Council Annual Report (2013b). We conducted four semi-structured interviews with high-level planners and urban designers from Brisbane City Council, as well as members of Brisbane Marketing involved in the development of the New World City brand and in the conceptualisation phase of the New City Centre Master Plan (CCMP). The interviewees were selected for their key role in the development of New World City brand and in the application of the brand into recent planning documents. The length of each interview was 45–60 min, and took place in the interviewee’s work office, providing information on the following key points: the production process of the city brand; and the influence of the NWC brand on planning strategies within the new CCMP. While the number of interviews is small, the top-down nature of place branding, and the ‘on-message’ consistency of the interviews indicated that there was a consistent approach, rationale and application of place branding in BCC.

Our analysis of Inala’s place branding and place identity is based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted over several years (2007–2012) which specifically analysed place attachment, place identity and other aspects of place for the Indigenous and intercultural communities within Inala, and the presentation and reception of the suburb within Brisbane more broadly (Greenop 2012). The fieldwork involved semi-structured interviews with over 30 community members, and long-term participant observation with several local families and a community organisation, instrumental in creating and marketing local events. Supplementing this is an analysis of public events in Inala by other authors, also working from interviews and a qualitative analysis perspective.

The rationale for using Inala as case study comparison is to put the process and community involvement for the City Centre Master Plan and branding exercise into perspective, and compare the difference in brand reach between CBD and periphery. McFarlane (2011 p. 228) argues that we can use the concept of assemblage to better understand urban spatial forms. As McFarlane (2011 p. 652) states:

Cities are produced through processes of uneven development based on rounds of accumulation, commoditisation, and particular geographies of biased investment and preference that produce unequal processes of urbanisation.

In Brisbane, Inala and the city centre represent two very distinct urbanisation processes and expressions of brand, though they are within the same governance system. Assemblage also: “orientates the researcher to the multiple practices through which urbanism is produced” (McFarlane 2011 p. 652). Contrasting the city centre case study with the Inala case study helps in understanding the different outcomes of Brisbane’s planning as well as how those different geographies are being produced within the same city, in part as a result of city branding. This approach also enables us to develop a critical perspective on Brisbane’s urbanism.

We apply the concept of assemblage (McFarlane 2011) by analysing different facets (different geographies) of the same reality (one city: Brisbane). Critical urban theory is based on the critical approach of the Frankfurt School and ultimately, the aim of such an urban theory is to find alternatives to unjust urbanization processes (Bremner et al. 2011 p. 201). In our conclusion we propose suitable alternatives to the current situation in Brisbane.

Findings

Brisbane’s branding history

For decades of the 20th Century and somewhat persisting today, Brisbane has had the reputation of being, at best a ‘big country town’, and at worst being ‘1 hour and 20 years behind’ (Courier Mail 2013) referring to the lack of summer time daylight savings, and more substantially its ‘backward’ nature, politically, socially and and culturally. The current marketing focus on Brisbane as a ‘New World City’, eschews this history in favour of a tabula rasa evading associations with the colonial, the dominating conservative politics of the mid-late 20th Century, and the enduring image as a cultural desert. In particular the state’s history of the ultra-conservative state Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen who ruled for 19 years from 1968 to 1987 with an oppressive and draconian regime restricting civil liberties and one-vote-one-value democracy, is seen as particularly embarrassing for Queensland.

In 1988 the World Expo in Brisbane brought a new focus on the importance of engagement with domestic and global ideas, the arts, tourism and creativity. 1991 marked the beginning of a Labor Lord Mayorship under Jim Soorley, who oversaw planning changes which shifted the focus of Brisbane’s river to being a place of entertainment and recreation, rather than industry. The city was open to new planning ideas such as outdoor dining and residential densification around public transport nodes, and became involved in social justice initiatives such as the city taking a role in assistance for homeless people. Subsequent state governments, both Labor and conservative, reformed the State’s laws on rights to protest and brought an end to the voting gerrymander. Federal recognition of Aboriginal people’s rights to land through Native Title were also being establishedFootnote 1 (following the Mabo no 2 v State of Queensland decision in the High Court in 1992). Despite these huge social and urban changes, Brisbane’s reputation, its brand, in the larger capital cities remained tarnished, particularly in terms of lacking culture and sophistication. Brisbane’s positive attributes were acknowledged but did not impress the cultural elites: it has been seen as a place of development, of money and commerce, but not high culture.

Within Brisbane, distinct local brands developed for particular parts of the city, a response to place meaning, reputation and complex associations with places based on media and personal experiences. Inala was developed as a new public housing suburb in Brisbane’s south west from the 1950s and soon became home to post World War II European migrants, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and non-Indigenous populations, all drawn in on the basis of housing need (Kaeys 2006) (See Fig. 1). Following the initial residents, new cohorts of migrants including a large Vietnamese population from the 1970s, and more recently Polynesian and African families have added to Inala’s diverse community (ABS 2013). While the compulsion to move into Inala was, and often still is, based on accessing public housing, the continued residence of many families is based on place attachment, and the formation of supportive communities that allow residents to maintain their cultural values (Greenop 2012).

Inala has had an unenviable historical reputation as a place of relative poverty, social unrest and dysfunction (Peel 2003; Kaeys 2006). The media’s focus on problem events within the suburb and surrounding neighbourhoods in the 1980s and 90s resulted in a reputation that remains today, though this is reducing to an extent. If examined through the lens of branding, this reputation, though not ‘promoted’ by marketing strategies, was nevertheless disseminated through media and Inala was a ‘brand’ with negative associations (Peel 2003 p. 33; Greenop 2012) of being a ‘slum’ (Norton 2010) and Brisbane’s ‘worst suburb’ (see discussion in Peel 2003). Despite this, there is a depth of place identification of some of Inala’s residents attesting to the historical and continuing development of its sense of place. One resident stated that despite moving to Inala only to access public housing, “Inala is home now, for life” (Greenop 2012, p. 144). This place attachment leads to stability of people in place, created in part by the support of a culturally specific community, and aligns with the components of social sustainability outlined by Dempsey et al. (2011).

In more recent decades the Inala brand has been greatly improved through growing social capital within the suburb, built up over decades of work by residents to increase social cohesion, NGO capacity and capability, has resulted in favourable outcomes for infrastructure and services within Inala. These attributes have now become attractive to outsiders, for example recent press on Inala as an ‘exotic’ shopping destination (Courier Mail, April 2014; Brisbane News 2011). Improved public transport, urban renewal and other factors have led to increased property prices and investor interest within the past 5 years to name but one indicator of increasing desirability (Property Observer 2013). We argue that this has been a case of place-identity based branding, rather than branding reflecting a top-down agenda of brand promotion.

Inala: place brand and identity through incremental actions

Ethnographic research with members of the Aboriginal community within Inala investigated their very strong place attachment and in some cases place identity links to the suburb (Greenop 2012). For many Inala people they are “Inala Boys” (or Girls) first and foremost, and take great pride in their identification with the place, in spite of any tainted place reputation. This is similar to the findings of Brown et al. (2013) with the “Bad is Good” marketing of Belfast, and pride in identity discussed in other low socioeconomic status parts of Australia (Peel 2003).

We argue that such attachment, sense of place and authenticity of place is achieved in Inala through the work of both locals and the state in creating places that operate to enhance community while acknowledging history. While some commentators argue that reconciliation with Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples requires an acknowledgement by the state and individuals, of Aboriginal history, particularly colonisation and other harmful state practices and their ongoing effects (for example Read 2000), the branding of Inala contrasts with this approach. Many events and brand statements in Inala focus on resident’s contemporary experiences and continuity of cultures, both aiming for unity and celebrating diversity, and ongoing cultural strengths rather than deficiencies or historical damage.

Local Inala initiatives in place-making and developing community have included an Indigenous-operated community pre-school, active cultural groups and sporting teams, and the Stylin’UP Indigenous Youth Festival by Brisbane City Council and local community groups. These ongoing, diverse forms of place-making provide a deepening sense of place in Inala, based on activities and the history that gathers around their continuation over time. The Stylin’UP festival began in 2000 as a project by the Inala Elders (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporation) in partnership with the Brisbane City Council (Bartleet et al. 2009 p. 113) and community activists. The Stylin’UP motto: “Pride in self, pride in community, pride in culture” (Stylin’Up 2013) emphasises the place-based links developed through programs. Stylin’UP operates as community driven, state-supported event that develops local sense of place and through which place branding occurs.

The branding of the festival draws on the distinctive characteristics of the host location Inala, with its high proportion of Indigenous and migrant resident communities. While traditional dance, songs and food are celebrated, contemporary forms of culture in Hip Hop, R’n’B music and ‘krumping’ dances are also performed, drawing in youth to the festival, and incorporating cross-cultural forms to brand a more diverse and yet unified Inala identity.

The imagery used in the branding of this event seeks to not only capture a youth market, but influence that demographic positively, with its no-smoking, no-alcohol, no-drugs message (see Fig. 2). Much of the branded merchandise and promotion for Stylin’UP is produced by local youth, financially supported by the Brisbane City Council through embedded arts workers, guided by an intensive local process. The festival event welcomes Elders and families with their provision of an Elder’s tent offering a choice view, seating and refreshments in line with Indigenous protocols of respect and caring for older family members.

Other enterprises in Inala, such as businesses that provide culturally specific foods, clothing and goods from Vietnam and the Pacific Islands, highlight the commercial opportunities that are being developed through such residential communities that maintain their stability over time. In recent times the authenticity of Inala’s cultures and their maintenance of traditions has been seen as valuable cultural capital that those in the more ‘ordinary’ nearby suburbs seek to acquire.

Comments from the residents in the developer created, master-planned neighbouring suburb of Forest Lake, established in the 1990s have raised concerns over the difference between Inala and Forest Lake stating that: “‘[Inala] has wonderful community groups’…Local community leader Rob Scott said Inala had greater community co-operation than Forest Lake.” (South-West News 2008). This description highlights that sense of place and place identity in Inala are perceived as more developed than in Forest Lake, based on the involvement of community groups in decisions and planning within the community. While not erasing the socioeconomic disadvantages that Inala faces, this approach seems to be envied by at least some neighbours in Forest Lake who sense the danger of becoming a non-place where the developer ‘has done everything’.

Inala’s original planning includes components we would now identify as key to social sustainability: walkable local shops, schools, churches and playgrounds, forming important neighbourhoods hubs within the broader community. The street pattern of grids and a hierarchy of roads is highly navigable and suitable for bus-based public transport. This is in contrast to the culs-de-sac approach of more modern suburbs, including Forest Lake, in which privacy and car-based transport are emphasised, which many planners argue can lead to isolation and disconnected communities (Lucy and Phillips 2006).

The key points from the Inala case study that illustrate how planning and place identity are related are: place identity is related to the valuing of urban amenity for people of all ages, including social, educational, sporting and cultural facilities; place identity builds up over time (over decades) based on activities and experiences that occur in place; high levels of social capital and place identity are interconnected; the branding of Inala displays multiculturalism and Indigeneity as assets.

New World City: the production process of a city brand

The New World City brand was the subject of interviews three senior Brisbane City Council (BCC) employees: the manager of Brisbane Marketing (a division of Brisbane City Council), manager of Communication (BCC), and manager City Planning and Economic Development (BCC). BCC is also responsible for Urban Renewal Brisbane (URB) a planning division of BCC, and for producing the City Centre Master Plan and Brisbane City plan, documents which govern the city’s future development.

According to our interviewees, the process of re-branding Brisbane began with World Expo’88. From this time Brisbane’s domestic and international image became a key focus of politicians and planners, but Brisbane has suffered from being a relative ‘loser city’ (Rousseau 2009) compared to Sydney and Melbourne.

Interviewee 1 stated that the ‘New World City’ brand began development in November 2007 and continued for around 18 months, during which time more than 3600 interviews with community groups, residents associations and businesses were conducted, to develop an idea of what Brisbane “should be” (Interview 1 2013). “The idea was to get an overarching sense of what the city was and where the city wants to go in the future” (Interview 1). The resulting branding strategy is organised around two aspects: Brisbane as a tourist destination; and Brisbane as a ‘serious player’ in terms of economic and political influence, in line with ‘global city’ goals (e.g. as host of the G20 Summit in 2014). The interviewee stated that Brisbane Marketing’s focus “started with the marketing of Brisbane as a tourist destination…but [over time] more and more economic development became a priority too” (Interview 1).

In addition to interviews with stakeholders, Brisbane Marketing sought advice from international place brand experts to position Brisbane globally rather than in competition with other Australian cities, ironically, matching Sydney’s global approach (Kerr and Balakrishnan 2012). The New World City slogan was a result of this outsourcing to consultants, rather than the thousands of local consultations. The interviewee explained that the slogan has a multi-layered, and highly crafted set of meanings that are said to be contained within it:

“Australia’s” refers to the following: Quintessentially Australian—In a uniquely Brisbane way. Authentic and Iconic, proud achievers. Punching above our weight. “New” refers to: Forward thinking, creative, energetic and progressive. Fresh, youthful and enthusiastic; “World” refers to: Elevated beyond domestic stage. Confident. Global outlook; “City” refers to: Unique liveable urban communities. Central hubs of vibrant activity.” (Interview 1)

The individual parts of slogan carry the message, each word redolent; but the combination of the three words in combination—New World City—with their implications of the colonial ‘new world’ and a ‘new city’ are not discussed.

According to our interviewee, the brand is based on the key messages: Brisbane as an emerging global city;

-

1.

Innovating on what’s important from the past to set the tone for our future;

-

2.

Ranked the second best city in Asia for foreign investment;

-

3.

Named a ‘Gamma World City’ (gaining sense of confidence and desire to look to the future) [now elevated to a Beta World City (GaWC 2012)];

-

4.

Recognised for being friendly, tolerant, clean, green, sustainable, vibrant, youthful, energetic and creative. (Interview 1)

The latest campaign within the ‘New World City’ theme, is highly visual ‘Choose Brisbane’ (see Fig. 3) which Brisbane Marketing terms ‘serious player mode’. (Interview 1).

The city centre mater plan: a re-branding tool

Brisbane City Council’s City Centre Master Plan (CCMP) assists in the re-branding of the Central Business District and is draws upon the ‘New World City’ brand. The CCMP is a non-statutory document that helped shape the City Centre Neighbourhood Plan (Interviews 3 and 4 2014) which details local level actions. The Ideas Fiesta held in April–May 2013 (Interviews 3, 4) operated as both consultation and marketing for the CCMP; discussion of the plan was held alongside street picnics, films, laneway events, and entertainment. (BCC 2013a). Fiesta attendees were invited to comment on pre-selected design proposals both at the Ideas Fiesta event and through social media, to rank their popularity (Interview 4). This consultation and drafting of plans, operated by Brisbane City Council across a number of its divisions, has resulting in three CCMP themes of “Subtropical city” (influencing design), “River city” (locating public spaces) and “New World City” (promoting economic development) (Interviews 3 and 4). The CCMP is described within BCC as a marketing document even though it is purportedly to inform the planning of CBD neighbourhoods. The drafting of the CCMP by BCC was assisted by a major Brisbane planning firm played with most of the strategies based on the previous plan from 2006 (Interviews 3 and 4).

The city centre is imagined by BCC planners as different to the suburbs, the CBD design is seen as an iconic display of the Brisbane identity, in keeping with the New World City agenda (Interview 3). There is a specific aim to create a set of vibrant iconic places, each with their own ‘character’, offering offer a different experience (Interview 4, BCC 2013b p. 5). Interviewee 3 stated that the City Plan consultations are conducted differently, in a more conventional manner as residents in the suburbs are directly concerned with planning decisions (Interview 3). The BCC communication manager confirmed that: “We should be more clever about planning to create an identity that we can market to the world…nobody will choose to live in a city they have never heard of.” (Interview 2 2013).

The CCMP is also conceptualized around the vision of “Open Brisbane” which is itself informed by New World City (Economic development), the Subtropical city (Urban design) and the River city (Public spaces) strategies (Interviews 3 and 4). Interviewee 3 stated: “Some cities are trading on the past [European cities], Brisbane is looking forward [towards the future]…Brisbane as a New World City is vibrant, embracing, open [for businesses, for networking, to culture] and inviting to tourists” (Interview 3). The aim is for Brisbane to be seen as a better location for new business that Sydney or Melbourne (Interview 3)

Discussion

Planning and branding identities in planning outcomes

Planning is seen as central to Brisbane’s identity and the transformation of its brand, as described by BCC itself in their document ‘The making of a New World City 1991–2012’ (URB 2012). It states that planning and renewal initiatives from the 1990s are closely linked to the current objective of promoting Brisbane as the ‘New World City’. We can see this in current initiatives too, the Ideas Fiesta, for example, that both seeks and shapes opinions, with pre-selected schemes for approval; it entertains and ranks, rather than debates ideas, and those offered, we argue, were limited to generic spaces of consumption (Fullagar et al. 2013). The consumption marketed within the NWC brand is, as Bavinton (2010) argues for Newcastle (UK), a narrative of the sedate pleasures of food and wine, never becoming rowdy drunken, or aberrant. This is despite the well-known clashing of night-life noise and residents' expectations of quiet in Brisbane (Darchen and Ladouceur 2013) and other Australian cities, and the broader gentrification issues as incoming inner-city dwellers confront homelessness, drug abuse, or other social issues (see Shaw 2007).

The identity being promoted by the NWC includes ideas of a global, consumptive citizen who chooses Brisbane from a plethora of cities. The ‘open for business’ economic strategy is, we argue, being mirrored in designs that display visible ‘open’ consumption—retail, food and entertainment spaces—where the flows of capital are clearly seen to be business as well as leisure opportunities. The planning for ‘iconic places’ aims to establish a unique visual cues that will remind people of Brisbane. Wealth, class values and standards of decorum, in both people and spaces, are present in the designs and reflect the strategy for Brisbane to attract international workers and investors.

We argue that Brisbane’s branding strategy is still an attempt to shake off a suburban identity, with the focus on the need to ‘activate’ the CBD into a 24 h location, one of the global cultural cities. Brisbane City Council nevertheless recently foreshadowed a further major suburban development in the newly announced Upper Kedron “mega-suburb” (Courier Mail 2014a). While new suburbs are being constructed and promoted to a local audience as part of Brisbane’s family-based lifestyle, for an international audience Brisbane is the glossy CBD of high rise towers, the New World City of Brisbane Marketing. Inala in contrast, is promoted for a local, multi-cultural audience. While this is hardly surprising, the difference between local and international audiences, and the shaping of place brand and identity for both residents' and marketing needs is important to note. The core is privileged as was the city ‘really’ is, while the periphery is invisible except on a local level.

While branding proposes unique characteristics of place, the generic nature of the high rise glossy Brisbane CBD imagery and is arguably the opposite approach. The NWC brand acts a tabula rasa upon which businesses and internationally mobile individuals are able to make their mark in an ‘open’ city where capital flows freely. The ‘New World’ component of the brand slogan implies symbolic links to the colonial new world of the Americas, for some, including Australia. This new world symbolism links to the contemporary creation of a terra nullius, land without inhabitants, erasing violent colonial history, and the twentieth Century politics that are still resonant to many Brisbane residents’ place identity. In Inala, politics, diversity, local needs and issues are central to both the brand and activities. The re-imagining of Brisbane as a ‘new’ city without either a problematic colonial, or dull suburban, past does not reflect how these historic layers and entanglements affect and contribute to the place meaning and place identity of Brisbane, especially for its long-term residents. Despite the cultural capital embedded in Australia’s broader branding of being home to the “world’s most ancient living culture” (Tourism Australia 2012) within and planning and branding of city spaces Aboriginal cultures remain uncomfortably absent from branding of Australia’s urban places (McGaw et al. 2011, Behrendt 2009).

We argue that there are two factors have influenced the character of CCMP decision-making processes: firstly the CBD lacks a long-term coherent residential population (a legacy of Brisbane’s dominant suburban housing) and this has resulted in strong input to the CCMP consultation from CBD businesses, while residents’ contributions were less explicit. Secondly, the structure of Brisbane as a mega-council limits local democracy and facilitates the spread and adoption of the NWC brand as federating discourse. While place is present in the sense of branding the ‘place’ of Brisbane, and the physical interventions of planning being situated in place (location) and related to making particular types of places (locale) there is little consideration of the ‘sense of place’ or genius loci, in the NWC imagery, or the CCMP.

Core and periphery identities in branding

Residents’ perceptions of place identity builds up over time (over decades) based on activities and experiences that occur in physical settings that become meaningful to people; place branding is usually fast and top-down, based on marketing ideas rather than community aspirations or needs. The Inala case study demonstrates that high levels of social capital and place identity are interconnected. From the commentary by BCC planners we can see that this gives residents and community groups in Inala both freedom to ‘brand’ their suburb as they choose, but ignores their presence within the broader image of Brisbane, which is glossed as the CBD. In effect: it does not matter to the branding what Inala (or any other suburban area in Brisbane) is like, what matters is the CBD. The targeting of differing audiences for the CBD and suburban branding explains the difference between these two approaches: Inala as a brand speaks to its residents first and then to the Brisbane population more broadly. The Brisbane NWC brand attempts to address an ethnically diverse city in a slogan and imagery with few idiosyncrasies represented, aimed at in international audience whose preferences are unknown.

The consequences of this are that unique and important place identities (for Inala and of course many other places within Brisbane’s suburbs, see Ip 2005) is silo-ed into invisible (to marketing) suburban spaces on the periphery, while the CBD, with far fewer residents, can become a place with almost fantasy-like attributes. The CCMP and the building projects that it produces provide imagery of “a hedonistic leisurescape of individualised freedom” (Fullagar et al. 2013 p. 3). Fullagar et al. (2013) have argued in relation to Brisbane that some apartment projects promise liveability, while delivering few of the diverse services required by such a term. The branding and activities within Inala display multiculturalism and Indigeneity as assets, and residents have helped shape events and the place brand. The branding of Brisbane NWC in contrast attempts to provide a tabula rasa onto which any global identity could be projected, however in doing so it excludes the specificities of its audience or Brisbane’s residents and tends towards a “generic city” (Koolhaas and Mau 1995) approach.

Conclusion

City re-imaging is not new, as Smith (2005) explains municipal authorities set aside budgets for image building and shaping for many years; Karavatzis and Ashworth (2005, p. 506) also state that: “places differentiate themselves from each other to assert their individuality in pursuit of various economic, political objectives”. In the case of Inala, recent place branding affirms a unique an identity, based on distinctive place and resident characteristics, associated with this is a process in which some place activities are community-driven. These strategies at the periphery of the city are not well represented in the New World City branding of the core. For Brisbane CBD, the branding exercise is the latest iteration in the long-running re-imaging of Brisbane, using the CBD specifically to stand in for the whole city. An important characteristic of this is that the New World City branding precedes and informs planning strategies, especially the imperative of economic development and the shaping of city spaces to enable that.

We have argued that the NWC branding has served as a marketing tool to justify planning options used within the CCMP. The NWC brand has created an overarching, but limited, identity that has federated decision-makers from BCC in their planning strategies, and had a strong influence on planning strategies for the city centre. Place-identity in this case is not the product of deep public involvement, but rather, is informed by the aspiration for Brisbane to become a key economic player in the Asia–Pacific region. Strategies feeding into the CCMP then, are not considered as a tool to create a sense of place—connecting with the genius loci or residents’ place identity—but rather to reinforce the New World City brand.

While we acknowledge the challenge of engaging communities in a city centre context without a well-defined, or historically cohesive community of residents, we have argued that contrary to the Inala case study, in the CCMP public engagement is used a limited and often indirect way, contributing to place identity at the level of consultation only. In Inala planning and place-making was seen as a facilitator to create a sense of place but place identity was generated by resident’s activities. In the re-imaging of Brisbane’s identity the CBD is a strategic space, representing the whole city, where the NWC brand must be displayed, and this is made possible through Brisbane’s governance system as a mega-council.

Following our research question, the rationale for the NWC brand responds both to a need to assert Brisbane as strong economic player and also to promote a story of the city that is liberated from an embarrassing history. Brisbane’s violent colonial past offers the possibility of a a ‘bad is good’ approach to branding where acknowledgement of the city’s history could operate to reconcile disparate resident groups, as well as providing a genuinely unique sense of place for the city. The image of Brisbane could benefit from integrating Inala’s approach to present itself as an “open” city, that is, beyond being open to capital, the city as being open to distinctive, place-based identities. The branding would then draw on what is authentic and unique to Brisbane compared to other cities in Australia and global locations. This amounts to a more full acknowledging of additional meanings of place in the branding processes, and a contribution of the ‘periphery’ to the construction of an identity for the ‘core’.

In this call for change to planning and branding of Brisbane, we align with the argument made by Insch (2011) and others that place branding needs to incorporate resident buy-in and a more ethical approach, without which place branding becomes merely a chimera, lacking an authentic place identity to inform the brand. In summary to achieve this, we recommend two sets of actions: (1) Incorporate resident-centred processes, in the construction of Brisbane’s urban strategy; (2) Include the suburbs in the construction of this urbanity by developing planning strategies that consider the centre and the suburbs. Only through acknowledging the contemporary political, social and cultural identities that are already present in Brisbane, and their roots in its historical past, can the city hope to re-brand itself and come to terms with the haunting spectre of the its history.

Notes

Following the decision in the High Court in 1992: Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (Commonwealth Law Reports, HCA 23; [1992] 175 CLR 1 [3 June 1992]).

References

Agnew, J. A. (1987). Place and politics, the geographical mediation of state and society. Boston: Allen and Unwin.

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Silverstein, M., & Jacobson, M. (1977). A pattern language: Towns, buildings, constructions. New York: Oxford University Press.

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of planners, 35(4), 216–224.

Atkinson, S., Painter, J., & Fuller, S. (Eds.). (2012). Wellbeing and place. Fanham and Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Augé, M., (2008/1995). Non-Places. An introduction to the anthropology of supermodernity. London: Verso.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), (2014). “Capital Cities: past, present and future”, Media release. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3218.0Media%20Release12012-13?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3218.0&issue=2012-13&num=&view Accessed 3 Apr 2014.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2013). “2011 Census QuickStats, Inala, Statistical Local Area”. http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/quickstat/305071288?opendocument&navpos=220 Accessed 3 Apr 2014.

Bartleet, B. L., Dunbar-Hall, P., Letts, R., & Schippers, H. (2009). Sound links community music in Australia. Brisbane: Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University.

Bavinton, N. (2010). Putting leisure to work: city image and representation of nightlife. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 2(3), 236–250.

Behrendt, L. (2009). Home: The importance of place to the dispossessed. South Atlantic Quarterly, 108(1), 71–85.

Bennett, R., & Savani, S. (2003). The rebranding of city places: An international comparative investigation. International Public Management Review, 4(2), 70–87.

Bremner, N., Madden, D. J., & Wasmuth, D. (2011). Assemblages urbanism and the challenges of critical urban theory. City, 15(2), 226–240.

Brisbane City Council (BCC). (2012). City Centre Master Plan (CCMP) www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/ planning-building/planning-guidelines-and-tools/city-centre-master-plan/index.htm Accessed 3 April 2014.

Brisbane City Council (BCC). (2013a). Ideas Fiesta 11 April-3 May 2013. Wrap Up Report. Brisbane: Brisbane City Council. http://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/ideas_fiesta_wrap_up_report.pdf.

Brisbane City Council (BCC). (2013b). Brisbane City Council Annual Report, 2012-2013. Brisbane: Brisbane City Council.

Brisbane City Council (BCC). (2013c). Budget Summary 2013-2014, Brisbane: Brisbane City Council. http://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/067073.doc Accessed 10 Dec 2014.

Brisbane City Council (BCC). (2013d). Planning for the future: The draft New City Plan. Brisbane: Brisbane City Council.

Brisbane City Council (BCC). (2014a). Eastern corridor neighbourhood plan. Brisbane: Brisbane City Council.

Brisbane City Council (BCC). (2014b). “Visit Brisbane” http://www.visitbrisbane.com.au Accessed 3 Apr 2014.

Brisbane City Council (BCC). (2014c) “Brisbane Marketing”. http://www.brisbanemarketing.com.au. Accessed 23 Jan 2015.

Brisbane News, (2011). “Finding Flavour”, 19th January.

Brown, S., McDonagh, P., & Shultz, C. J, I. I. (2013). A brand so bad it’s good: The paradoxical place marketing of Belfast. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(11–12), 1251–1276.

Chasser, A. H., & Wolfe, J. C. (2010). Brand rewired: Connecting intellectual property, branding, and creativity strategy. New York: Wiley.

Colomb, C., and Kalandides, A., (2010). “The ‘be Berlin’ campaign: old wine in new bottles M. Kavaratzis (Eds), Towards Effective Place Brand Management: Branding European Cities and Regions (pp 173–90). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Courier Mail (newspaper), (2014).“OPINION: The Brisbane suburb of Inala is the place to go for Asian cuisine and groceries”, M. Butle reporter. 24th April. http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/opinion/opinion-the-brisbane-suburb-of-inala-is-the-place-to-go-for-asian-cuisine-and-groceries/story-fnihsr9v-1226895203841 Accessed 24 Apr 2014.

Courier Mail (newspaper), (2014a). “Mega-suburb all but set to emerge in Upper Kedron” http://www.couriermail.com.au/questnews/mega-suburb-all-but-set-to-emerge-in-upper-kedron/story-fni9r0hy-1227141213121.

Cleave, E., & Arku, G. (2014). Place branding and economic development at the local development in Ontario, Canada. GeoJournal,. doi:10.1007/s10708-014-9555-9.

Cresswell, T. (2004). Place: A short introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Cuba, L., & Hummon, D. M. (1993). A place to call home: Identification with dwelling, community, and region. The sociological quarterly, 34(1), 111–131.

Darchen, S., & Ladouceur, E. (2013). Social sustainability in urban regeneration: Case study of the Fortitude Valley renewal plan in Brisbane. Australian Planner, 50(4), 340–350.

Dempsey, N., Bramley, G., Power, S., & Brown, C. (2011). The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustainable Development, 19(5), 289–300.

Devine-Wright, P. (2014) Dynamics of place attachment in a climate changed world. In L. C. Manzo & P. Devine-Wright (Eds.), Place attachment: Advances in theory, methods and applications. London: Routledge.

Dinnie, K. (2011). City branding: Theory and cases. London: Pallgrave Mc-Millan.

Falleth, E., & Saglie, I. L. (2011). Democracy or efficiency: contradictory national guidelines in urban planning in Norway. Urban Research and Practice, 4(1), 58–71.

Fullagar, S., Pavlidis, A., Reid, S., & Lloyd, K. (2013). Living it up in the ‘new world city’: High-rise development and the promise of liveability. Annals of Leisure Research, 16(4), 280–296.

Giuliani, M. (1991). Towards an analysis of mental representations of attachment to the home. The Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 8(2), 133–146.

Giuliani, M. V. (2003). Theory of attachment and place attachment. In M. Bonnes, T. Lee & M. Bonaiuto (Eds.), Psychological theories for environmental issues (pp. 137–170). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Giovanardi, M., Lucarelli, A., & Pasquinelli, C. (2013). Towards brand ecology: An analytical semiotic framework for interpreting the emergence of place brands. Marketing Theory, 13(3), 365–383.

Globalization and World Cities (GaWC) Research Network, (2012). “The world according to GaWC 2012” Department of Geography, Loughborough University, Loughborough. http://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2012t.html Accessed 3 Apr 2014.

Greenop, K. (2012). It gets under your skin: Place meaning, attachment, identity and sovereignty in the urban Indigenous community of Inala, Queensland. PhD Thesis, School of Architecture, The University of Queensland.

Haila, A. (2006). The neglected builder of the global city. In N. Brenner & R. Keil (Eds.), The Global cities reader (pp. 282–287). London and New York: Routledge.

Hankinson, G. (2001). Location branding: a study of the branding practices of 12 English cities. The Journal of Brand Management, 9(2), 127–142.

Harvey, D. (1993). From space to place and back again: Reflections on the condition of postmodernity. In J. Bird, B. Curtis, T. Putnam, G. Robertson, & L. Tickner (Eds.), Mapping the futures local cultures, global change (pp. 3–29). London: Routledge.

Insch, A. (2011). Ethics of place making. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 7(3), 151–154.

Ip, D. (2005). Contesting Chinatown: Place-making and the emergence of ‘Ethnoburbia’’ in Brisbane, Australia. GeoJournal, 64(1), 63–74.

Jencks, C. (2005). The iconic building: The Power of Enigma. London: Frances Lincoln.

Julier, G. (2005). Urban designscapes and the production of aesthetic consent. Urban Studies, 42(5/6), 869–887.

Kaeys, S., (2006). “Stories of the Suburbs: the Origins of Richlands ‘Servicetown’/Inala Area on Brisbane’s Western Fringe” paper presented at The Pacific in Australia; Australia in the Pacific Conference, Australian Association for the Advancement of Pacific Studies (AAAPS), January QUT Carseldine. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/archive/00004995/ Accessed 5 July 2012.

Kariel, H. G., & Rosenvall, L. A. (1984). Factors influencing international news flow. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 61(3), 509–666.

Kavaratzis, M., & Ashworth, G. J. (2005). City branding: an effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick? Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 96(5), 506–514.

Kerr, G., & Balakrishnan, M. S. (2012). Challenges in managing place brands: The case of Sydney. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 8(1), 6–16.

Kipfer, S., & Keil, R. (2002). Toronto Inc. Planning the competitive city in the new Toronto. Antipode, 34(2), 227–264.

Koolhaas, R., & Mau, B. (1995). S, M, L, XL. New York: Monacelli Press.

Knox, P. L. (2011). Cities and design. London: Routledge.

Lewicka, M. (2010). What makes neighborhood different from home and city? Effects of place scale on place attachment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(1), 35–51.

Lucarelli, A., & Berg, P. O. (2011). City branding: a state-of-the-art review of the research domain. Journal of Place Management and Development, 4(1), 9–27.

Lucy, W., & Phillips, D. (2006). Tomorrow’s cities, tomorrow’s suburbs. Chicago: American Planning Association.

Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Madgin, R., & Rodger, R. (2013). Inspiring Capital? Deconstructing myths and reconstructing urban environments, Edinburgh, 1860–2010. Urban History, 40, 507–529. doi:10.1017/S0963926813000448.

McCann, E. J. (2009). City marketing. In K. Rob & N. Thrift (Eds.), International encyclopedia of human geography (pp. 119–124). Oxford: Elsevier.

McFarlane, C. (2011). Assemblage and critical urban praxis: Part one. Assemblage and critical urbanism. City., 15(2), 204–224.

McGaw, J., Pieris, A., & Potter, E. (2011). Indigenous place-making in the city: Dispossessions, occupations and implications for cultural architecture. Architectural Theory Review., 16(3), 296–311.

Massey, D. (1993). Power-geometry and a progressive sense of place. In J. Bird, B. Curtis, T. Putnam, G. Robertson, & L. Tickner (Eds.), Mapping the Futures Local cultures, global change (pp. 119–124). London: Routledge.

Medway, D., & Warnaby, G. (2014). What’s in a name? Place branding and toponymic commodification. Environment and Planning A, 46, 153–167.

Norberg-Schulz, C. (1980). Genius loci. New York: Rizzoli.

Norton, C., (2010) “Govt slammed for Bundy slum plan”, NewMail online, 22 December, http://www.news-mail.com.au/story/2010/12/22/government-slammed-for-bundaberg-slum-plan/.

Pasquinelli, C. (2013). Branding as urban collective strategy-making: The formation of Newcastle Gateshead’s organizational identity. Urban Studies, 51(4), 727–743.

Peel, M. (2003). The lowest rung voices of Australian poverty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Property Observer (2013) “Durack and Inala top the REIQ Brisbane’s 12 highest yielding suburbs for housing investment” http://www.propertyobserver.com.au/finding/location/qld/21932-news-top-12-brisbane-house-yield-suburbs.html Accessed 5 Nov 2013.

Proshansky, H. M., Fabian, A. K., & Kaminoff, R. (1983). Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3(1), 57–83.

Read, P. (1996). Returning to nothing: The meaning of lost places. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Read, P. (2000). Belonging: Australians, place and Aboriginal ownership. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Relph, E. (1976). Place and placelessness. London: Pion.

Rousseau, M. (2009). Re-imaging the city centre for the middle classes: Regeneration, Gentrification and symbolic policies in ‘loser cities’. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(3), 770–788.

Rowe, C., & Koetter, F. (1978). Collage City. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Russell, J. A., & Ward, L. M. (1982). Environmental psychology. Annual Review of Psychology, 33(1), 651–689.

Searle, G., and Minnery, J., (2014) “The influence of mega councils on urban planning outcomes: The case of Brisbane City Council” paper presented at Planning Institute of Australia congress 15–19 March.

Shaw, W. S. (2007). Cities of whiteness. Oxford: Wiley.

Smith, A. (2005). Conceptualizing city image change: The re-imaging of Barcelona. Tourism Geographies: An International Journal of Tourism Space, Place and Environment, 7(4), 398–423.

South-West News (newspaper), (2008). “Inala hailed as top model” Access 2 Apr 2014.

Spearitt, P. (2009). The 200 Km City: Brisbane, the Gold Coast, and Sunshine Coast. Australian Economic History Review, 49(1), 87–106.

Stylin’UP, (2013). “Stylin’Up” http://www.stylinup.com.au/?page_id=2 Accessed 3 Nov 2013.

Tourism Australia, (2012). “Aboriginal Australia” http://www.tourism.australia.com/en-au/marketing/experiences_5665.aspx Accessed 3 November 2013.

Tuan, Y. F. (1974). Topophilia. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Twigger-Ross, C., Bonaiuto, M., & Breakwell, G. M. (2003). Identity theories and environmental psychology (pp. 203–234). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Urban Renewal Brisbane (URB), (2012). The making of a New World City, 1991–2012 Brisbane: Brisbane City Council.

Warnarby, G., & Medway, P. (2013). What about the place in place marketing? Marketing Theory, 13(3), 345–363.

Zukin, S. (1992). The City as a landscape of power: London and New York as global financial capitals. In L. Budd & S. Whimster (Eds.), Global finance and urban living (pp. 8–9). London and New York: Routledge.

Interviews

Interview 1 (2013). Brisbane Marketing.

Interview 2 (2013). Interview with Brisbane City Council Communications Manager, 21st June.

Interview 3 (2014). Interview with Brisbane City Council Manager City Planning and Economic Development, 22nd January.

Interview 4 (2014) Brisbane Urban Renewal, 28th January.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank and acknowledge our research participants in Inala, and in Brisbane City Council, Brisbane Marketing and Brisbane Urban Renewal for their contribution to the research. This research was made possible through the support of the School of Architecture and the School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, The University of Queensland. We would like to thank Amy Learmonth for producing the map, the UQ-HAUS readership group for suggestions and the anonymous referees for excellent critical comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greenop, K., Darchen, S. Identifying ‘place’ in place branding: core and periphery in Brisbane’s “New World City”. GeoJournal 81, 379–394 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-015-9625-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-015-9625-7