Abstract

The interest in Citrus and related genera as ornamental plants has increased in recent years, motivating studies aimed at identifying genotypes, varieties and hybrids suitable for this purpose. The Citrus Active Germplasm Bank of the Embrapa Cassava & Fruits, a research unit of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation—Embrapa, contains more than 750 accessions with wide genetic variability, and their utilization for ornamental purposes is the objective of this study. For this purpose, we characterized 37 accessions with ornamental potential, classified in four categories for use in floriculture: potted plants, minifruit, hedges and landscaping. Through the use of 39 quantitative and qualitative morphological descriptors, the following accessions stood out for use landscaping and as potted plants: ‘Variegated’ calamondin, ‘Nasnaran’ mandarin, ‘Chinotto’ orange, ‘Trifoliate limeberry’, ‘Papeda Kalpi’, ‘Talamisan’ orange, ‘Wart Java’ lime, and ‘Chinese box-orange’, besides accessions of the genera Fortunella, Poncirus and Microcitrus. Among the accessions identified as having potential for use as minifruit plants, the common ‘Sunki’ mandarin was the most suitable, and in the hedge category, ‘Chinese box-orange’ and ‘Trifoliate limeberry’ stood out. The results obtained provide information to support citrus breeding programs for ornamental purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Citrus L. and related genera belong to the family Rutaceae and contain species with huge economic value, the highlights being trees producing sweet oranges [C. sinensis (L.) Osbeck], besides lemons [C. limon (L.) Burm. f.], limes (various species), tangerines and mandarins (various species) and grapefruits (C. paradisi Macfad.). In 2012, global production of citrus fruits reached 131.3 million metric tons (FAO 2015). The potential uses of citrus fruits, however, go beyond consumption of fresh fruit and juice, including raw materials such as essential oils for the production of medicines, pesticides, fragrances and flavorings (Silva 1995; Bizzo 2009).

Regarding the use of citrus plants for ornamental purposes, the first reports date to circa 1000 B.C. in China (Donadio et al. 2005). Despite this long heritage, the ornamental exploitation of citrus plants is still incipient and restricted to recommendations by a few landscape experts. In Europe in particular, a movement is starting to gain force in favor of ornamental citriculture, not only for use of varieties described and cultivated in the past, but also to establish genetic improvement programs to develop hybrids for this purpose, such as the efforts of research institutions in Italy (Del Bosco 2003).

The Citrus Active Germplasm Bank (CAGB) of Embrapa Cassava & Fruits, located in Cruz das Almas, Bahia state, Brazil, contains more than 750 accessions, making it highly representative in number of species and genera. It has potential for identification and generation of ornamental varieties, considering the significant genetic variability of its accessions. The study of this variability can support genetic improvement programs to generate ornamental hybrids. In this respect, the characterization of the accessions preserved is an essential step to identify the potential of this germplasm bank, because the data obtained from such studies will define the diversity of the accessions and determine their potential for employment in different categories of ornamental use, such as for potted plants, minifruit, landscaping or hedges.

Similar studies have been conducted for characterization of fruit-bearing species and their classification in ornamental use categories with pineapple (Ananas) (Souza et al. 2012a) and banana (Musa) (Souza et al. 2012b), resulting in a rich database for diverse applications as well as for genetic breeding, refinement of knowledge on taxonomy and evolution and conservation studies.

Investigation of the genetic resources available in the CAGB is important to generate new products to meet the needs of the market (Koehler-Santos et al. 2003). The most important traits involve the plant crown, leaves and fruits, where the major part of the available descriptors are concentrated.

Similar studies have been conducted by Mazzini and Pio (2010), who characterized the morphology of six citrus varieties and identified the ornamental potential of the Buddha’s hand citron [C. medica var. sarcodactylis (Hoola van Nooten) Swingle], so named because its fruits are similar to a hand and have strong yellow color, as well as the ‘Cipó’ and ‘Imperial’ sweet oranges, because of their drooping branches and variegated fruits and leaves.

Likewise, the purpose of this study was to characterize the accessions of the Citrus Active Germplasm Bank of Embrapa Cassava & Fruits by means of quantitative and qualitative morphological descriptors, to identify genotypes with ornamental potential and to classify them in different use categories. Another objective was to generate information for use in genetic improvement programs for development of ornamental citrus varieties.

Materials and methods

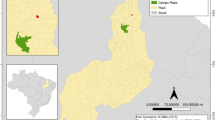

This study was conducted at the CAGB experimental area, located at 12º40′19″ south latitude and 39º06′22″ west longitude, in the municipality of Cruz das Almas, Bahia, Brazil.

According to the Köppen classification, the climate in Cruz das Almas is a transition between the Am and Aw zones, with average annual rainfall of 1143 mm, average temperature of 24.28 °C and relative humidity of 60.47 %. The soil of the experimental area is a typical dystrophic Yellow Latosol, A moderate, sandy clay loam texture, kaolinite, hypoferric, transition zone between subperennial and semideciduous rainforest, with slope of 0–3 %.

The CAGB is composed of at least two plants of each accession, which receive routine crop treatments. The rootstocks used are the ‘Rangpur’ lime (C. limonia Osbeck), ‘Volkamer’ lemon (C. volkameriana Ten. & Pasq) and ‘Cleopatra’ mandarin (C. reshni hort. ex Tanaka). The plants are grown with spacing of 5 m × 4 m or 6 m × 4 m, in function of the vigor of the different accessions.

We selected 37 accessions of citrus with ornamental potential: ‘Nasnaran’ mandarin {C. amblycarpa [(Hassk.) Ochse]}, ‘Galego Inerme Key’ lime [C. aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle], ‘Narrow Leaf’ sour orange (C. aurantium L.), ‘Bergamot’ orange (C. bergamia Risso & Poit.), ‘Taiwan’ mandarin (C. depressa Hayata), ‘Mauritius papeda’ (C. hystrix DC.), C. hystrix hybrid, ‘Variegated’ true lemon (C. limon), ‘Talamisan’ orange (C. longispina Wester), ‘Etrog’ citron (C. medica L.), ‘Variegated’ calamondin (C. madurensis auct.), ‘Chinotto’ orange (C. myrtifolia Raf.), ‘Star Ruby’ grapefruit (C. paradisi Macfad.), ‘Cleopatra’ mandarin (C. reshni hort. ex Tanaka), ‘Fairchild’ tangerine-tangelo [C. clementina hort. ex Tanaka × (C. paradisi × C. tangerina hort. ex Tanaka)], ‘Szincom’ mandarin (C. reticulata Blanco), ‘Valencia Trepadeira’ sweet orange (C. sinensis), ‘Variegated’ sweet orange (C. sinensis), ‘Jaboti’ tangor (C. sinensis × C. unshiu Marcow.), common ‘Sunki’ mandarin [C. sunki (Hayata) hort. ex Tanaka], ‘Tachibana’ orange [C. tachibana (Makino) Tanaka], ‘Mency’ tangor (C. tangerina × C. sinensis), ‘Papeda Kalpi’ (C. webberi Wester var. montana Wester), ‘Jindou’ kumquat [Fortunella hindsii (Champ. ex Benth.) Swingle], Fortunella sp., ‘Changshou’ kumquat (F. x obovata hort. ex Tanaka); ‘Jindan’ kumquat (F. x crassifolia Swingle); ‘Wart Java’ lime (Citrus sp.), Microcitrus papuana Winters, ‘Benecke’ trifoliate orange [Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf.], ‘Coleman’ citrange (C. sinensis × P. trifoliata), ‘Flying Dragon’ trifoliate orange (P. trifoliata), ‘Chinese box-orange’ (Severinia buxifolia [(Poir.) Ten.], ‘Limeberry’ {Triphasia trifolia [(Burm. f.) P. Wilson]}, ‘Cravo’ mandarin (C. reticulata), ‘Citros Processo’ (Citrus sp.), and ‘Jerônimo’ lime (Citrus sp.).

We applied 39 descriptors, 10 of them quantitative and 29 qualitative (IPGRI 1999). Among the quantitative descriptors, three were related to traits of the plants, four to leaf traits and three to fruit traits. Of the qualitative descriptors, five were related to attributes of the plants, nine to the leaves, five to the flowers and ten to the fruits. The definition of each ornamental category for classification of the accessions was based on the following characteristics:

-

Potted plants Plant height below 170 cm, crown diameter smaller than 150 cm, moderate or dense branching, preferably with few or no spines. Accessions with larger height and crown diameter could be considered, if associated with dwarf rootstock or plants manageable by topiary to keep them small.

-

Minifruits plants Fruit diameter (or length for elongated fruits) varying from 2.5 cm to 4.5 cm.

-

Hedges plants Dense branching.

-

Landscaping plants Broad category, possibly including potted plants, minifruit and hedges. One desirable common feature of plants in this category is absence or low density of spines.

The data were submitted to analysis of variance and the means were compared by the Scott–Knott test at 5 % probability, using the SAS statistical program (SAS Institute 2010). The colors were compared with the color chart of the Royal Horticulture Society (RHS). The relative contribution of each quantitative variable was calculated using the criterion of Singh (1981) by the Genes program (Cruz 2006). Finally, the Gower algorithm (1971) was applied for joint analysis qualitative and quantitative data by determining the genetic distance.

The hierarchical clusterings of the accessions were achieved by the UPGMA methods (unweighted pair group method using an arithmetic average) based on the average Euclidean distance between all the accessions. The validation of the clusterings was determined by the cophenetic correlation coefficient (r) (Sokal and Rohlf 1962).

The statistical software system (R Development Core Team 2006) was used for the analyses of genetic distance, hierarchical clusterings and cophenetic correlation. The cophenetic correlation was calculated by the t and Mantel tests (10,000 permutations). The dendrogram was generated based on the distance matrix by the MEGA 4 software system (Tamura et al. 2007).

Results and discussion

From applying the morphological descriptors utilized it was possible to characterize the accessions with ornamental potential, besides classify them in the use categories. The variability found was probably due to the great diversity among individuals in the CAGB regarding size, color and shape of the leaves (Fig. 1), fruits (Fig. 2) and flowers (Fig. 3). The evaluation of the relative importance of the 10 quantitative descriptors in judging the variability among the accessions was carried out by the method of Singh (1981). The crown diameter descriptor contributed 68.93 % of the morphological divergence between individuals, followed by plant height, which accounted for 30.92 %. These results show that these two variables are responsible for a significant part of the phenotypical variability identified (Table 1).

Morphological variability of leaves of 37 accessions of Citrus L. and related genera. a ‘Nasnaran’ mandarin (C. amblycarpa), b ‘Galego Inerme Key’ lime (C. aurantiifolia), c ‘Narrow Leaf’ sour orange (C. aurantium), d ‘Bergamot’ orange (C. bergamia), e ‘Taiwan’ mandarin (C. depressa), f ‘Mauritius papeda’ (C. hystrix), g C. hystrix hybrid, h ‘Variegated’ true lemon (C. limon), i ‘Talamisan’ orange (C. longispina), j ‘Etrog’ citron (C. medica), k ‘Variegated’ calamondin (C. madurensis), l ‘Chinotto’ orange (C. myrtifolia), m ‘Star Ruby’ grapefruit (C. paradisi), n ‘Cleopatra’ mandarin (C. reshni), o ‘Fairchild’ tangerine-tangelo [C. clementina × (C. paradisi × C. tangerina)], p ‘Szincom’ mandarin (C. reticulata), q ‘Valencia Trepadeira’ sweet orange (C. sinensis)\, r ‘Variegated’ sweet orange (C. sinensis), s ‘Jaboti’ tangor (C. sinensis × C. unshiu), t common ‘Sunki’ mandarin (C. sunki), u ‘Tachibana’ orange (C. tachibana), v ‘Mency’ tangor (C. tangerina × C. sinensis), w ‘Papeda Kalpi’ (C. webberi var. montana), x ‘Jindou’ kumquat (Fortunella hindsii), y Fortunella sp., z ‘Changshou’ kumquat (F. x obovata), aa ‘Jindan’ kumquat (F. x crassifolia), ab ‘Wart Java’ lime (Citrus sp.), ac Microcitrus papuana, ad ‘Benecke’ trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata), ae ‘Coleman’ citrange (C. sinensis × P. trifoliata), af ‘Flying Dragon’ trifoliate orange (P. trifoliata), ag ‘Chinese box-orange’ (Severinia buxifolia), ah ‘Limeberry’ (Triphasia trifolia), ai ‘Cravo’ mandarin (C. reticulata), aj ‘Citros Processo’ (Citrus sp.), ak ‘Jerônimo’ lime (Citrus sp.). Bars 5 cm

Morphological variability of fruits of 37 accessions of Citrus L. and related genera. a ‘Nasnaran’ mandarin (C. amblycarpa), b ‘Galego Inerme Key’ lime (C. aurantiifolia), c ‘Narrow Leaf’ sour orange (C. aurantium), d ‘Bergamot’ orange (C. bergamia), e ‘Taiwan’ mandarin (C. depressa), f ‘Mauritius papeda’ (C. hystrix), g C. hystrix hybrid, h ‘Variegated’ true lemon (C. limon), i ‘Talamisan’ orange (C. longispina), j ‘Etrog’ citron (C. medica), k ‘Variegated’ calamondin (C. madurensis), l ‘Chinotto’ orange (C. myrtifolia), m ‘Star Ruby’ grapefruit (C. paradisi), n ‘Cleopatra’ mandarin (C. reshni), o ‘Fairchild’ tangerine-tangelo [C. clementina × (C. paradisi × C. tangerina)], p ‘Szincom’ mandarin (C. reticulata), q ‘Valencia Trepadeira’ sweet orange (C. sinensis), r ‘Variegated’ sweet orange (C. sinensis), s ‘Jaboti’ tangor (C. sinensis × C. unshiu), t common ‘Sunki’ mandarin (C. sunki), u ‘Tachibana’ orange (C. tachibana), v ‘Mency’ tangor (C. tangerina × C. sinensis), w ‘Papeda Kalpi’ (C. webberi var. montana), x ‘Jindou’ kumquat (Fortunella hindsii), y Fortunella sp., z ‘Changshou’ kumquat (F. x obovata), aa ‘Jindan’ kumquat (F. x crassifolia), ab ‘Wart Java’ lime (Citrus sp.), ac Microcitrus papuana, ad ‘Benecke’ trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata), ae ‘Coleman’ citrange (C. sinensis × P. trifoliata), af ‘Flying Dragon’ trifoliate orange (P. trifoliata), ag ‘Chinese box-orange’ (Severinia buxifolia), ah ‘Limeberry’ (Triphasia trifolia), ai ‘Cravo’ mandarin (C. reticulata), aj ‘Citros Processo’ (Citrus sp.), ak ‘Jerônimo’ lime (Citrus sp.). Bars 5 cm

Morphological variability of flowers of 21 accessions of Citrus L. and related genera. a ‘Nasnaran’ mandarin (C. amblycarpa), b ‘Galego Inerme Key’ lime (C. aurantiifolia), c ‘Taiwan’ mandarin (C. depressa), d ‘Mauritius papeda’ (C. hystrix), e C. hystrix hybrid, f ‘Variegated’ true lemon (C. limon), g ‘Talamisan’ orange (C. longispina), h ‘Etrog’ citron (C. medica), i ‘Variegated’ calamondin (C. madurensis), j ‘Star Ruby’ grapefruit (C. paradisi), k ‘Valencia Trepadeira’ sweet orange (C. sinensis), l ‘Papeda Kalpi’ (C. webberi var. montana), m ‘Jindou’ kumquat (Fortunella hindsii), n Fortunella sp., o ‘Changshou’ kumquat (F. x obovata), p ‘Jindan’ kumquat (F. x crassifolia), q ‘Benecke’ trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata), r ‘Coleman’ citrange (C. sinensis × P. trifoliata), s ‘Flying Dragon’ trifoliate orange (P. trifoliata), t ‘Chinese box-orange’ (Severinia buxifolia), u ‘Limeberry’ (Triphasia trifolia). Bars 5 cm

The joint analysis of the qualitative and quantitative data of the 37 accessions evaluated led to the formation of eight groups (Fig. 4) by UPGMA based in the pairwise Euclidean distance between all the accessions, using the genetic dissimilarity (D dg = 0.4) as the cutoff point.

The dendrogram generated presented cophenetic correlation coefficient of r = 0.70 (P < 0.0001, 10,000 permutations). This coefficient permits assessing the consistency of the grouping pattern between the elements of the dissimilarity matrix as well as the elements of the simplified matrix obtained by the grouping method. Values near one indicate better graphical representation (Rohlf and Fisher 1968). According to the results, there was a good fit between the graphical representation of the Euclidean distances and the original matrix. In a similar study with pineapple, Souza et al. (2012a) found a relatively high cophenetic correlation coefficient (r = 0.81), a value considered good when dealing with quantitative and qualitative morphological data.

Group G1 is composed of only one accession, M. papuana, which originates from tropical Asia (USDA 2014) and has several attractive characteristics from the ornamental standpoint. Its small size and dense ellipsoidal crown (Table 2) make this species highly recommended for the potted plant and landscaping categories. Its high branch density and presence of spines allows its use to form hedges and its small elongated fruits (Tables 3, 4; Fig. 5a) are attractive and decorative. Probably the distinctive morphological traits of the fruits and leaves were decisive for this accession to be alone in this group. M. papuana has been successfully employed by the Citrus Genetic Improvement Program of Embrapa Cassava & Fruits as a parental in crosses aiming to obtain plants with ornamental qualities as well as to generate rootstocks, given the high drought tolerance of the genus Microcitrus (Swingle) (Swingle 1967).

Plant and detail of the branches of accessions of Citrus L. and related genera. a M. papuana, b ‘Flying Dragon’ trifoliate orange (P. trifoliata), c ‘Talamisan’ orange (C. longispina), d ‘Valencia Trepadeira’ sweet orange (C. sinensis), e, f ‘Variegated’ sweet orange (C. sinensis), g, h ‘Variegated’ true lemon (C. limon), i ‘Galego Inerme Key’ lime (C. aurantiifolia), j ‘Mauritius papeda’ (C. hystrix), k ‘Limeberry’ (Triphasia trifolia), l, m ‘Chinese box-orange’ (Severinia buxifolia), n ‘Chinotto’ orange (C. myrtifolia), o ‘Jindou’ kumquat (Fortunella hindsii), p ‘Changshou’ kumquat (F. x obovata), q) ‘Jindan’ kumquat (F. x crassifolia), r ‘Cravo’ mandarin (C. reticulata), s, t common ‘Sunki’ mandarin (C. sunki), u ‘Nasnaran’ mandarin (C. amblycarpa), v ‘Variegated’ calamondin (C. madurensis), w ‘Bergamot’ orange (C. bergamia), x ‘Papeda Kalpi’ (C. webberi), y ‘Etrog’ citron (C. medica)

Group G2 is formed of two well-defined subgroups, the first composed of the ‘Benecke’ and ‘Flying Dragon’ trifoliate oranges and the ‘Coleman’ citrange.

Varieties of P. trifoliataare widely distributed in northern and central China (USDA 2014). The trees are small to medium in size, with long spines (Table 2). Their leaves are trifoliated (Fig. 1ad, af) and their fruits (Fig. 2ad, af) have a papillate texture and are bright yellow when ripe, besides being highly aromatic, an important characteristic of ornamental plants. The flowering of Poncirus Raf. is abundant and its flowers and spines are large (Table 5; Figs. 3q, s, 5b), favoring use in landscaping and as hedges of for production of minifruit plants.

The ‘Coleman’ citrange has very similar traits to those of the Poncirus accessions, which compose its group (‘Benecke’ and ‘Flying Dragon’) and can also be recommended in the potted plant category.

Also in this group, the accessions ‘Wart Java’ lime, ‘Valencia Trepadeira’ sweet orange and ‘Talamisan’ orange form a second grouping. According to the system of Tanaka (1961), C. sinensis and C. longispina originated in Asia and are part of the subgenus Archicitrus. Due to the presence of highly dense crowns and uniform branching, the ‘Talamisan’ orange and ‘Wart Java’ lime are recommended as potted plants and for landscaping (Fig. 5c). The ‘Wart Java’ lime is also suitable for producing small fruits, because they have a rough peel and light yellow color when ripe (Fig. 2ab; Table 4).

The ‘Valencia Trepadeira’ sweet orange is an accession of Asian origin (USDA 2014) and although it produces relatively large leaves (Fig. 1q) and fruits (Fig. 2q) among sweet orange varieties (Table 4), it has an ovoid crown, with drooping branches, which can be supported on lattices to form pergolas, making it recommended for landscaping (Fig. 5d). Besides this, its flowering is intense, with large flowers and pinkish floral buds (Fig. 3k). It is also recommended as a parental to form hybrids because of its small size. In a similar study, Mazzini and Pio (2010) evaluated the ‘Cipó’ sweet orange, a synonym of ‘Valencia Trepadeira’, also finding it to have the same recommended uses as found here.

Group G3 is composed of only two accessions, the ‘Variegated’ sweet orange (Fig. 5e, f) and ‘Variegated’ true lemon (Fig. 5g, h). These accessions, whose species belong to the subgenus Archictrus (Lanjouw 1961; Tanaka 1961), are very similar and can be easily confused. They are medium-sized erect plants with ellipsoid crown (Table 2). They have great ornamental potential and can be managed through pruning or topiary, for use in pots or for landscaping. Their leaves have varied colors, with green and white or light cream shades and elliptical shape (Fig. 1h, r; Table 3). The fruits also have varied color, from yellow to dark green (Fig. 2h, r). They have the medium size of the common sweet orange, but the plant can be classified in the minifruit ornamental category because of the fruits appealing appearance when unripe. Probably the morphological traits of coloration and leaf shape were decisive in these two accessions isolation in this group.

The decorative value of the ‘Variegated’ sweet orange and ‘Variegated’ true lemon can be significantly enhanced by using dwarf rootstocks, a strategy that can also be applied to the other accessions evaluated.

Group G4 contains C. hystrix, along with a hybrid of this species and the ‘Galego Inerme Key’ lime. According to Tanaka (1961), these species belong to the subgenus Archicitrus. The ‘Galego Inerme Key’ lime is recommended for use in landscaping and in crosses aimed at producing ornamental hybrids, since this accession of totally free of spines (Fig. 5i).

The species C. hystrix is native to temperate and tropical Asia (USDA 2014). It has a dense crown with branches starting near the base (Fig. 5j). Its leaves are dark green and longipetiolate, with large phyllodes, composing up to 50 % of their size (Fig. 1f). The fruits are aromatic, green and highly attractive from the ornamental viewpoint due to their rough peels (Fig. 2f; Table 4). This accession is recommended for minifruit and landscaping plants.

According to Swingle (1967), C. hystrix is naturally hybridized with other species of the Citrus genus, and some of these hybrid varieties being included among the different forms described by Wester in the period between 1913 and 1915. This can explain the origin of the C. hystrix hybrid evaluated in this study, whose characteristics of size and foliage (Fig. 1g) are very similar to those of other C. hystrix varieties and is suitable for landscaping.

Three accessions formed Group G5: ‘Limeberry’, ‘Chinese box-orange’ and ‘Chinotto’ orange. The first is small, with dense branching (Table 2) and elliptical trifoliated leaves (Fig. 1ah; Table 3). The flowers are small and white and have three petals (Table 5; Fig. 3u). Its fruits are small and abundant, with dark green color (Fig. 2ah; Table 4), a trait that contrasts with the leaf color, giving it good ornamental potential (Fig. 5k). The ‘Limeberry’ probably originated in Asia (USDA 2014), and it is widely cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions as an ornamental and hedge plant. The observations in this study corroborate the indications by Swingle (1967) for this accession, which can be used as a potted plant, in landscaping and to form hedges.

S. buxifolia, commonly called the ‘Chinese box-orange’ or boxthorn, is native to tropical and temperate Asia (USDA 2014). It has medium size and a dense crown (Table 2; Fig. 5l, m) with high density of leaves and spines (Fig. 1ag) and small fruits (Fig. 2ag) and flowers (Fig. 3t). The fruits, which resemble berries, are black when ripe and abundant. This accession can be used as a potted plant or for landscaping.

C. myrtifolia, also known as the ‘Chinotto’ orange (Hodgson 1967), is small and without spines (Table 2), with branches completely covered by small, shiny, dark green leaves (Table 3). The coloration of its abundant fruits ranges from dark yellow to orange, making this species recommended for ornamental use in pots and landscaping (Fig. 5n). It is cultivated in Italy as a decorative plant (Saunt 1990; USDA 2014). It can also be recommended in the minifruit category.

In this study, we evaluated four species of Fortunella (Swingle), or kumquat, all of them in Group G6: F. hindsii, known as the ‘Jindou’ kumquat (Fig. 5o), F. x obovata, also called the ‘Changchou’ kumquat (Fig. 5p), Fortunella sp. and F. x crassifolia, popularly known as the ‘Jindan’ kumquat (Fig. 5q).

The data found for the ‘Jindou’ kumquat coincide with the descriptions of Swingle (1967) and Saunt (1990), who stated that the plants of this species are small with thin branches, differing from other species of the genus, which are much larger. This accession produces small, bright orange colored fruits and has strong ornamental potential (Fig. 2x; Table 4). The use of this species for ornamental landscaping was mentioned by Saunt (1990), and we can recommend it as a potted and/or minifruit plant as well.

The other three Fortunella accessions analyzed are very similar to each other and are recommended for use in the same categories mentioned above. The Changchou stands out for its pyriform fruits, which are quite different from the other kumquat species. These small fruits can also be used in decorative arrangements (Fig. 2z; Table 4).

Species of the Fortunella genus all produce small and abundant orange-colored fruits that are highly aromatic. The peel is fleshy and edible when the fruit is ripe. They are widely cultivated in Japan and China along with other subtropical regions (Swingle 1967).

Group G7 is formed of 17 accessions, of them 12 species and hybrids in the tangerine or micro-tangerine category. Tangerines and mandarins trees fall in an extensive and diversified group, containing different species and varieties that often have sharp distinctions, making it hard to list traits common to all of them. In general, they produce small flowers and medium-sized fruits with orange color that are easy to peel (Hodgson 1967; Saunt 1990).

These results are in accordance with the findings of Nicolosi et al. (2000), who studied the phylogenetic aspects of accessions of Citrus and related genera based on RAPD and SCAR markers, finding considerable genetic similarity among tangerine accessions. A similar result was obtained by Bastianel et al. (2001), who grouped tangerine and sour orange species in the same group, like in this study.

The ‘Cravo’ mandarin tree is probably native to Asia (USDA 2014). It is tall, without spines, with dense spheroid crown (Table 2) and produces medium-sized fruits with slightly rough surface and deep orange color when ripe (Fig. 2ai; Table 4). Because of its size, it is only recommended for landscaping (Fig. 5r), but is an interesting candidate for genetic alteration with parentals to reduce its stature, as has been achieved with Fortunella, Poncirus and Microcitrus. The size of the hybrids obtained could be reduced even more by using dwarf rootstock varieties. Another C. reticulate accession is the ‘Szincom’ mandarin, which has similar characteristics to the ‘Cravo’ variety and the same potential use.

The ‘Sunki’ mandarin tree is widely grown in temperate Asia (USDA 2014) and produces fruits classified as micro-tangerines (Fig. 5s, t). According to Araújo and Salibe (2002), this term refers to species or varieties of Citrus that have small leaves, flowers and (generally sour) fruits. As an adult, it reaches up to 4 meters (Table 2), with a dense spheroid crown and no spines. Its leaves are small and dark green (Fig. 1t; Table 3) and it yields plentiful fruit for most of the year. These micro-tangerines are oblate, with few seeds and have deep orange peels when ripe (Fig. 2t). Despite its tall size, the ‘Sunki’ mandarin tree is widely used for ornamental purposes due to the sharp contrast between its fruits and foliage. It can be used for landscaping of large open areas, although its best use is for production of small fruits. At the Citrus Genetic Improvement Program of Embrapa Cassava & Fruits the common ‘Sunki’ stands out as an important female parental in controlled crosses (Soares Filho et al. 2013, 2014). Observations in populations of hybrids in the field indicate that the ‘Sunki’ mandarin has great potential to minifruit production.

The ‘Cleopatra’ mandarin, Citrus sp. (in this article identified as ‘Citros Processo’), ‘Tachibana’ orange and C. depressa (‘Taiwan’ mandarin) are similar to the common ‘Sunki’ mandarin and can be recommended for the same ornamental uses. The ‘Cleopatra’, which is widely cultivated in tropical Asia and South America (USDA 2014), is a prolific fruit producer, making it attractive as an ornamental plant, mainly in the minifruit category (Hodgson 1967).

Citrus sp. refers to an accession that was impossible to identify to the species level, but it has characteristics very near those of the common ‘Sunki’ mandarin, as well as some similarity with the ‘Cleopatra’ variety, although the latter’s fruits are larger. The fruits are small (Table 4) and differ from the ‘Sunki’ variety only by the lighter orange color (Fig. 2aj). It is recommended for landscaping and decorative arrangements of minifruit plants.

C. amblycarpa, also known as ‘Nasnaran’ mandarin (USDA 2014), is a micro-tangerine species with dense ovoid crown and sparse spines (Table 2). The fruits are oblate and have rough peels which turn yellow when ripe (Fig. 2a; Table 4). It is a species recommended as a potted plant, for landscaping and as a minifruit plant (Fig. 5u).

The ‘Tachibana’ orange, native to Japan (USDA 2014), has similar appearance to micro-mandarin species, with tall stature, dense crown and no spines (Table 2). The fruits are small and oblate and turn yellow when ripe (Fig. 2u; Table 4). This accession can be recommended for landscaping and minifruit plants.

The ‘Jaboti’ tangor is a hybrid of the ‘Natal’ sweet orange and the ‘Satsuma’ mandarin. The accession is tall, with dense spheroid crown and has no spines (Table 2). Its leaves are dark green (Fig. 1s; Table 3). The fruits are oblate and medium sized, with deep orange color when ripe (Fig. 2s; Table 4). Due to the size of its crown, it is recommended for landscaping, but can also be used as a parental in crosses to obtain hybrids with other potential ornamental uses.

The ‘Mency’ tangor is a hybrid of the ‘Dancy’ tangerine and the ‘Mediterranean’ sweet orange (Hodgson 1967), with similar characteristics to the ‘Jaboti’ tangor, so the ornamental recommendations are the same.

The ‘Fairchild’ tangerine-tangelo is a hybrid of the ‘Clementine’ tangerine (C. clementina) and the ‘Orlando’ tangelo (C. paradisi x C. tangerina), commercially launched in 1964 (Soost and Roose 1996). It has medium size, ovoid crown and no spines (Table 2). It produces many fruits, which are orange and spheroid, with slightly truncated apex and base (Fig. 2o; Table 4). The description of Hodgson (1967) for this hybrid coincides with our observations. It is recommended for landscaping and as a parental to produce genotypes with ornamental potential.

The ‘Variegated’ calamondin is short, with spherical crown, no spines and medium to dense branching (Fig. 5v; Table 2). Its leaves are variegated, oval and small (Fig. 1k; Table 3), giving it good ornamental potential. The fruits are abundant, small, spherical and variegated when immature (Fig. 2k; Table 4). It is recommended for use as a potted plant, for landscaping and as a minifruit plant. It is sold by nurseries in Florida and California (USA) as a potted plant (Hodgson 1967).

Besides the 12 accessions with fruits classified as tangerines or mandarins already mentioned, five others are contained in Group G7: ‘Jerônimo’ lime, ‘Narrow Leaf’ sour orange, ‘Bergamot’ orange, ‘Papeda Kalpi’ and ‘Etrog’ citron.

The ‘Jerônimo’ lime was classified as Citrus sp., although it is possibly a natural hybrid of the rough lemon (C. jambhiri Lush.). This accession has small size, ovoid and drooping crown, with sparse to average branching (Table 2). It was included in this study mainly because of its small size and drooping branches, allowing it to be used as coverage for pergolas.

The ‘Narrow Leaf’ sour orange is cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions, and possibly originates from China (USDA 2014). It is a tall tree that grows vertically straight, with elliptical crown and no spines (Fig. 2o; Table 2). It has dark green lanceolate leaves that are long and narrow (Fig. 1c; Table 3), hence its name. According to Saunt (1990), sour orange varieties are grown for ornamental purposes in public and private gardens in many countries due to their perceived beauty. This is especially the case along the Mediterranean coast and in places in Arizona and California. Therefore, the ‘Narrow Leaf’ tree can be used for landscaping and in genetic improvement programs to generate hybrids with other potential ornamental uses.

C. bergamia, known as ‘Bergamot’, is a natural hybrid from crossing C. medica and [C. maxima (Burm.) Merr. x C. reticulata] (USDA 2014). The crown is pronouncedly erect (Fig. 5w), it does not have spines and its leaves stand out for their orbicular shape, bright green color and curled format (Fig. 1d). It is recommended for landscaping and in genetic improvement programs due to its unique foliage.

C. webberi var. montana, also known as ‘Papeda Kalpi’, is medium-sized, with a dense ovoid crown and no spines (Fig. 5x; Table 2). Its leaves are oval and longipetiolate, with winged petioles having the same size as the leaf limbus (Fig. 1w; Table 3). It is attractive for landscaping due to the shape and density of the crown, and can also be recommended as a potted plant and for forming hedges.

The ‘Etrog’ citron probably is native to China and India (USDA 2014), and is one of the basic Citrus species. Along with C. maxima and C. reticulate sensu Swingle, it is at the root of the ancestral species of Citrus (Barrett and Rhodes 1976; Velasco and Licciardello 2014). It has medium size, a crown with scarce to medium branching and has spines (Fig. 5y; Table 2). The fruits are large and ovoid, with a characteristic fragrance and yellow color when ripe (Fig. 2j; Table 4). Some varieties of the citron group, such as the ‘Buddha’s Hand’, are already widely used for ornamental purposes (Swingle 1967). The ‘Etrog’ citron can be used as a potted plant or for landscaping.

Group G8 only contains one accession, the ‘Star Ruby’ grapefruit. The tree is mediums-sized with a spheroid crown that has plentiful branches and low density of spines (Table 2). The ripe fruits are yellow and reddish pulp. This is the trait that sets it apart from the other accessions (Fig. 2m). It is recommended for landscaping and its fruits can be used in decorative arrangements.

Although the fruit persistence on trees was not directly evaluated in this work, it was observed that the accessions P. trifoliata selections, ‘Chinotto’ orange, ‘Star Ruby’ grapefruit, ‘Wart Java’ lime, M. papuana, ‘Jerônimo’ lime, ‘Variegated’ calamondin, ‘Variegated’ true lemon, ‘Variegated’ sweet orange, ‘Jaboti’ tangor, ‘Etrog’ citron, ‘Galego Inerme Key’ lime, ‘Papeda Kalpi’, ‘Narrow Leaf’ sour orange, ‘Bergamot’ orange, ‘Mauritius papeda’ and C. hystrix clearly presented more persistent fruits. On the other hand, mandarins, tangerines, micro-tangerines, and Fortunella spp., visually presented lower fruit persistence, indicated by the precocious fruit drop, in spite of their profuse fruiting. Fruit persistence is one of the traits to considerate for ornamental use in citrus, besides flowering and fruit set. Fruit persistence is particularly of interest because it determines the general value and attractiveness of a citrus ornamental tree, and might be a limitant factor in windy locations. All these traits are typical of the genotype and are genetically controlled, even though several environmental and physiological conditions might influence on them being also mediated by abiotic and biotic stresses and horticultural practices.

Conclusion

-

1.

The great morphological variability of the citrus accessions studied allows their classification in different ornamental use categories.

-

2.

The ‘Nasnaran’ mandarin, ‘Talamisan’ orange, ‘Variegated’ calamondin, ‘Chinotto’ orange, ‘Wart Java’ lime, ‘Limeberry’, ‘Variegated’ true lemon, ‘Variegated’ sweet orange, as well as the accessions belonging to the genera Fortunella and Poncirus, can be used in the potted plant and landscaping categories, although attention should be paid to the presence of spines in the case of Poncirus.

-

3.

‘Chinese box-orange’, ‘Limeberry’ and M. papuana can be employed as ornamental hedges.

-

4.

The common ‘Sunki’ mandarin can be used as a minifruit plant.

-

5.

The accessions studied can be used as parentals in crosses to generate ornamental citrus hybrids.

Abbreviations

- CAGB:

-

Citrus active germplasm bank

- UPGMA:

-

Unweighted pair group method using an arithmetic average

References

Araújo ARG, Salibe AA (2002) Caracterização físico-morfológica de frutos de microtangerinas (Citrus spp.) de potencial utilização como porta-enxertos. Rev Bras Frutic 24:618–621. doi:10.1590/S0100-29452002000300009

Barrett HC, Rhodes AM (1976) A numerical taxonomic study of affinity relationships in cultivated Citrus and its close relatives. Syst Bot 1:105–136

Bastianel M, Dornelles ALC, Machado MA, Wickert E, Maraschin SF, Coletta Filho HD, Schäfer G (2001) Caracterização de genotypes de Citrus spp. através de marcadores RAPD. Ciênc Rural 31:763–768. doi:10.1590/S0103-84782001000500004

Bizzo HR (2009) Brazilian essential oils: general view, developments and perspectives. Quím Nova 32:588–594. doi:10.1590/S0100-40422009000300005

Cruz CD (2006) Programa GENES: análise multivariada e simulação. UFV, Viçosa

Del Bosco SF (2003) The use for ornamental purposes of an ancient Citrus genotype. Acta Hortic 598:65–67

Development Core Team R (2006) A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Donadio LC, Mourão Filho FAA, Moreira CS (2005) Centros de origem, distribuição geográfica das plantas cítricas e histórico da citricultura no Brasil. In: Mattos Júnior D, De Negri JD, Pio RM, Pompeu Junior J (eds) Citros. Instituto Agronômico e Fundag, Campinas, pp 1–18

FAO (2015) FAOSTAT. Agricultural statistics database. World Agricultural Information Center, 2009 Rome. http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/default.aspx#ancor. Accessed 4 Jan 2015

Gower JC (1971) A general coefficient of similarity and some of its properties. Biometrics 27:857–874

Hodgson RW (1967) The botany of Citrus and its wild relatives. In: Reuther W, Webber HJ, Batchelor LD (eds) The citrus industry. University of California, Riverside

IPGRI—International Plant Genetic Resources Institute. Descriptors for Citrus. Rome: IBPGR (1999). http://www.bioversityinternational.org/e-library/publications/detail/descriptors-for-citrus-emcitrusem-spp/. Accessed 8 May 2012

Koehler-Santos P, Dornelles ALC, Freitas LB (2003) Characterization of mandarin citrus germplasm from Southern Brazil by morphological and molecular analyses. Pesq Agrop Bras 38:797–806. doi:10.1590/S0100-204X2003000700003

Lanjouw J (1961) International code of botanical nomenclature. Adopted by the Ninth International Botanical Congress (Montreal, 1959). Utrecht, 1961

Mazzini RB, Pio RM (2010) Morphological characterization of six citrus varieties with ornamental potential. Rev Bras Frutic 32:463–470. doi:10.1590/S0100-29452010005000043

Nicolosi E, Deng ZN, Gentile A, La Malfa S, Continella G, Tribulato E (2000) Citrus phylogeny and genetic origin of important species as investigated by molecular markers. Theor Appl Genet 100:1155–1166. doi:10.1007/s001220051419

Rohlf FJ, Fisher DR (1968) Tests for hierarchical structure in random data sets. Syst Biol 17:407–412. doi:10.1093/sysbio/17.4.407

SAS Institute (2010) SAS user’s guide: statistic: version 9.2. SAS Institute, Cary

Saunt J (1990) Citrus varieties of the world: an illustrated guide. Sinclair International, Norwich

Silva KT (1995) Development of essential oil industries in developing countries. In: Silva KT (ed) A manual on the essential oil industry. United Nations Industrial Development Organization, Vienna, pp 1–13

Singh D (1981) The relative importance of characters affecting genetic divergence. Indian J Genet Plant Breed 41:237–245

Soares Filho WS, Cunha Sobrinho AP, Passos OS, Souza AS (2013) Melhoramento genético. In: Cunha Sobrinho AP, Magalhães AFJ, Souza AS, Passos OS, Soares Filho WS (eds) Cultura dos citros. Embrapa, Brasília, pp 61–102

Soares Filho WS, Souza U, Ledo CAS, Santana LGL, Passos OS (2014) Polyembryony and potential of hybrid production in citrus. Rev Bras Frutic 36:950–956. doi:10.1590/0100-2945-345/13

Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ (1962) The comparison of dendrograms by objective methods. Taxon 11:33–40

Soost RK, Roose ML (1996) Citrus. In: Janick J, Moore JN (eds) Fruit breeding; tree and tropical fruits. Wiley, New York, pp 257–323

Souza EH, Costa MAPC, Souza FVD, Costa DS Jr, Amorim EP, Silva SO, Santos-Serejo JA (2012a) Genetic variability of banana with ornamental potential. Euphytica 184:355–367. doi:10.1007/s10681-011-0553-4

Souza EH, Souza FVD, Costa MAPC, Costa DS Jr, Santos-Serejo JA, Amorim EP, Ledo CAS (2012b) Genetic variation of the Ananas genus with ornamental potential. Genet Resour Crop Evol 59:1357–1376. doi:10.1007/s10722-011-9763-9

Swingle WT (1967) The botany of Citrus and its wild relatives. In: Reuther W, Webber HJ, Batchelor LD (eds) The citrus industry. University of California, Berkeley, pp 190–430

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S (2007) MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24:1596–1599. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm092

Tanaka T (1961) Citrologia. Semi-centennial commemoration papers on citrus studies. Citrologia Supporting Foundation, Osaka

USDA (2014) ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. Germplasm Resources Information Network—(GRIN). National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland. http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgibin/npgs/html/taxgenform.pl?language=pt. Accessed 12 Feb 2014

Velasco R, Licciardello C (2014) A genealogy of the citrus family. Nature 32:640–642. doi:10.1038/nbt.2954

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—CNPq (472492/2011-0), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for the scholarships granted. We also thank the researcher Orlando Sampaio Passos, curator of the Citrus Active Germplasm Bank of Embrapa Cassava & Fruits, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

dos Santos, A.R.A., de Souza, E.H., Souza, F.V.D. et al. Genetic variation of Citrus and related genera with ornamental potential. Euphytica 205, 503–520 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-015-1423-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-015-1423-2