Abstract

This study investigates the link between the educational characteristics of partners in heterosexual relationships and their transition to second births, accounting for the selection into parenthood by fitting multi-level event history models. We compare the fertility of Beckerian unions characterized by gender-role specialization with the fertility of dual-earner couples, characterized by the pooling of incomes. Focusing on the economic aspect of the educational degree, in a first step, we estimate the earning potential and unemployment risks by field and level of education, country and sex using European Labour Force Surveys. Next, we link these results with Generation and Gender Survey data from six countries and model couples’ transition to second births. We find evidence in support of both the pooling of resources family model (notably in Belgium) and the Beckerian gender-role specialization model. The effects of the earning potential and unemployment risk attached to his and her field of education tends to vary by country context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The expansion of women’s participation in higher education and in the labour market has led towards a diffusion of the dual-earner family model across Europe. Also, but at a slower pace, men have become more involved in household and family activities (Goldscheider et al. 2015). Gender differences in work and family involvement, which vary across contexts and over time, lead to gender differences in the trade-off between individuals’ investments in socio-economic resources and their childbearing decisions. Prominent micro-economic theories predict gender differences in the association between education and fertility: a positive association for men due to income effects and a negative association for women due to opportunity costs (Becker 1991). These predictions are based on the assumption that partners have a traditional gender division of labour, which was considered conducive to fertility, at least in the past.

More recent approaches suggest that the dual-earner family model, where partners pool their incomes (Oppenheimer 1994), may have become more conducive to fertility than the Beckerian specialization model in the last couple of decades. Yet, whether or not that is the case is still an open question. This is because many studies on fertility behaviour tend to keep an individual perspective. Since the association between socio-economic resources and fertility may differ between men and women, the focus on only one partner leads to unclear and misleading results (Singley and Hynes 2005; Trimarchi and Van Bavel 2017). Given the potential biases derived from an individual-only perspective and since the majority of births occur within unions, scholars have increasingly highlighted the relevance to approach fertility from a couple’s perspective (Corijn et al. 1996; Gustafsson and Worku 2006; Nitsche et al. 2018; Van Bavel 2012).

In this paper, we aim to overcome some of the limitations of earlier studies on the association between partners’ socio-economic resources and fertility. First, several couple-level studies have only addressed the transition to first birth (Begall 2013; Corijn et al. 1996; Gustafsson and Worku 2006; Jalovaara and Miettinen 2013; Trimarchi and Van Bavel 2018; Vignoli et al. 2012). However, low first birth rates are not the major driving force of very low fertility levels (Billari and Kohler 2004). Nowadays, fertility differences across European countries are prevalently due to differences in second- and higher-order births rather than in first birth transition probabilities (Klesment et al. 2014; Van Bavel and Rozanska-Putek 2010). Thus, it is critical to address the transition to higher-order births from a couple-level perspective.

Second, the few studies focusing on the transition to second- and higher-order births from a couple’s perspective have disregarded the selection into parenthood (Dribe and Stanfors 2010; Nitsche et al. 2018). This is a major shortcoming, since some highly educated partners, for unobserved reasons, may be more likely to have a child or be more likely to have it at an earlier age compared to other highly educated peers. Such selection makes them also more likely to have a second child earlier, and the positive association between education and fertility would then apply only to a selective subgroup (Kravdal 2001, 2007; Kravdal and Rindfuss 2008; Kreyenfeld 2002; Tesching 2012).

Next, the strand of research that focuses on the role of partners’ relative socio-economic resources for fertility has also considered employment, occupation and income of partners, beyond the level of education (e.g. Begall 2013; Dribe and Stanfors 2010; Jalovaara and Miettinen 2013; Osiewalska 2017; Vignoli et al. 2012). The use of variables that are associated with the economic aspect of education accounts for the fact that medium and especially highly educated people have become more heterogeneous groups due to the expansion of schooling and the generalization of participation in higher education. Field of study can be considered a distinctive predictor for partners’ labour market outcomes and cultural resources (Van de Werfhorst 2001; Reimer et al. 2008; Van Bavel 2010), but it has been often disregarded in previous studies. While gender inequalities in higher education are disappearing, the gender segregation with regard to the field of study has remained stable over time (Charles and Bradley 2009; DiPrete and Buchmann 2006). This reflects inequalities in the labour market, ensuing differences concerning the earning potential of men and women given the same level of education (Blau and Kahn 2016).

In fertility studies, one way to account for these differences is to use information about employment, occupation and income of the partners as independent variables. However, the use of these variables is problematic when studying fertility, since those are affected by childbearing decisions. This means that scholars have to deal with endogeneity when studying the relationship between employment, occupation, income and fertility rates. In contrast, the decision about the main field of study, which characterizes the highest level of education attained, is taken relatively early in the life course and it tends to be much more fixed over time, hence entailing less endogeneity issues.

With this paper, we contribute to the debate on the role of partners’ socio-economic status for couples’ fertility at least in two important ways. First, we study couples’ transition to second births taking into account the selection into parenthood, following an approach proposed by Kravdal (2001). Second, we propose a way to limit endogeneity issues due to the lack of time-varying information on earnings, employment status and occupation. For each partner, we estimated the earning potential and unemployment risks that are embodied in the educational degree, by using the European Labour Force Surveys (EU-LFS). We linked the results of these estimations with the Generations and Gender Surveys (GGS) of six European countries given the information on the level of education, field of study, sex and country of residence. This approach allows us to estimate the effect of couple pairings by educational level, earning potential and unemployment risks on second birth rates.

2 Education and Fertility: Economic and Cultural Aspects

In this study, we look at two dimensions of educational attainment (Lappegård and Rønsen 2005): level of education and field of study. These two dimensions are predictors of individual’s labour market outcomes, i.e. earning potential and unemployment risks. According to the Human Capital Theory, a higher level of education leads—after some time—to higher income (Becker 1964). However, not all study disciplines, given the same level of education, have similar labour market outcomes across Europe (Van de Werfhorst 2001; Reimer et al. 2008).

Next, this study focuses on second birth rates as main fertility outcome. Scholars have argued that declining second birth rates strongly explain the decline in fertility levels (Billari and Kohler 2004; Frejka 2008). The magnitude of this effect differs across regional contexts. Zeman et al. (2018) show that, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, cohort fertility (1955–1970) fell because of lower second birth transitions, whereas in Western and Northern European countries, cohort fertility fell more moderately across parities. These differences may be linked to several institutional factors: Central and Eastern European countries, relatively to Western and Northern Europe, are characterized by higher level of economic uncertainty in combination with difficult arrangements to reconcile family and work (Zeman et al. 2018).

2.1 Assortative Mating and Fertility

An extension of micro-economic theory to family behaviour, the New Home Economics, assumes that members of a family allocate efficiently and rationally their resources between household chores and labour market jobs (Becker 1991). Partners tend to specialize for efficiency reasons: the specialization strategy increases the interdependency between the partners, and it contributes to the value of the marriage.

Within the New Home Economics’ framework, men and women have different comparative advantages in household and market activities. Marriage may be seen as a contract between sexes: women trade their “expertise” in household activities, whereas men trade their income and market activities. According to Becker (1991), positive assortative mating in non-market traits (e.g. similar intelligence, similar attractiveness) maximizes the utility of marriage in combination with negative assortative mating in earning potential, implying differences in income between husband and wife, with the former typically having the higher earning potential.

Following Becker’s specialization model, it is possible to distinguish between two types of effects that drive the relationship between earning potential and fertility: the income and the price effect. The price effect is typical for those partners that specialize in household activities, traditionally women, since a higher income means greater opportunity costs. The income effect characterizes the relationship between earning potential and fertility for partners who specialize in labour market activities, typically men, since a higher income will allow them to afford more children. The balance in price and income effects between partners may yield to an efficient family model, which will be eventually conducive to fertility. Thus, a pairing would be conducive to fertility if the woman has a lower earning potential than her partner.

With increasing women’s human capital and participation in the labour market, Becker himself acknowledged that the division of labour may be detached from gender roles: “husbands would be more specialized in household work and wives to market activities in half marriages and the reverse would occur in the other half” (Becker 1991: 78). Given the societal changes that occurred from the early 1970s onwards, a specialization model is not necessarily built on traditional gender roles: the overall imbalance in earning potential between partners can be conducive to childbearing. Even if educational homogamy remains strong, traditionally, hypergamy was prevailing: if there was a difference in educational attainment, the husband tended to have more education than his wife. In more recent cohorts, hypogamy has become more common than hypergamy: more often the woman has more education than the man (Esteve et al. 2012; De Hauw et al. 2017; Grow and Van Bavel 2015).

The persistent gender segregation with regard to study disciplines challenges the idea that, within hypogamous couples, the woman has a higher earning potential than the man. Often, if the woman is highly educated and her partner has a lower level of education, the woman tends to be the main earner of the household (Klesment and Van Bavel 2017). However, female-dominated fields are typically less profitable in terms of earnings, and they tend to have a lower risk of skill depreciation but good compatibility between work and family. Women (but also men) may choose their field of study according to their attitudes about traditional gender roles (Van Bavel 2010). Men who choose a typically male-dominated field and women who self-select themselves in female-represented fields may have gender-stereotypical norms about the role of mother and father. We could define a “stereotypical couple” as one constituted of a man who graduated in a male-dominated field and a woman who graduated in a female-dominated field. Within a stereotypical couple, traditional gender identities may not be questioned, even if the earning potential of the partners is similar or even unbalanced in favour of the woman. The previous research showed that women graduated in a typical female-dominated field of study have a higher rate of first birth compared to their counterparts who graduated in fields with lower presence of women (Lappegård and Rønsen 2005; Martín-García and Baizán 2006; Van Bavel 2010; Tesching 2012; Begall and Mills 2013), while mixed results have been found for higher-order births and completed fertility (Hoem et al. 2006a, b; Tesching 2012). In contrast, female-dominated fields were not conducive to childbearing for men (Lappegard et al. 2011; Martín-García 2009).

Altogether, these findings support the argument that fields of study where women are over-represented are connected to fertility. They may be conducive to exhibit higher fertility, and conversely, higher fertility intentions may lead to a higher inclination to choose female-dominated fields. To our knowledge, no previous study has accounted for differentials in the economic aspects that are embodied in an educational degree (reflecting a level as well as a field of education) of both partners. This is a major shortcoming in fertility studies, especially with the diffusion of the dual-earner family model, where both partners contribute to the household income.

As pointed out by Oppenheimer (1988, 1994), the specialization of partners in paid and unpaid work can be a troublesome family model, especially in times of crisis, divorce or death of one of the partners (Oppenheimer 1988, 1994). In contrast with Becker, according to Oppenheimer (1988), individuals’ gains from marriage would derive from the possibilities to increase their standards of living by marrying a partner with higher earning potential than herself or himself. Oppenheimer (1994) suggested that given the structural changes in a globalized world, the pooling of resources between partners is a more efficient family model compared to specialization. Women’s employment may be an adaptive strategy that permits to diversify the family resources and to raise the economic living standards.

The consequences of a dual-earner society for fertility are not straightforward. A high level of earning potential at couples’ disposal helps to face the direct (and indirect) costs of children. Nevertheless, the costs of children are not fixed for every couple: partners desire that their own children have a similar or higher standard of living than themselves (Oppenheimer 1994; Hobcraft and Kiernan 1995). As a consequence, higher earning potential also implies higher costs of children.

Recently, Sobotka and Beaujouan (2014) showed that a two-child family ideal is persistent across time and contexts, even though findings have been unclear on the role of education and gender differences in shaping fertility intentions (Puur et al. 2008; Testa et al. 2014). Regardless of who is the partner with the highest earning potential, higher earnings may be functional to meet a two-child family ideal. A Swedish study supports the argument that a higher availability of socio-economic resources, measured by partners’ income and level of education, enhances the transition to the second and third births (Dribe and Stanfors 2010). Osiewalska (2017) found that, in Austria and Bulgaria, highly educated homogamous couples tend to have a lower number of children relatively to couples with a lower level of education. Additionally, hypogamous couples were found the least conducive to fertility. In France, instead, differentials in fertility levels by educational pairings were less pronounced (Osiewalska 2017). Nitsche et al. (2018) found that highly educated women partnered with highly educated men have among the highest second birth rates in several regions of Europe. All these studies account for both partners’ characteristics but disregard the selection into parenthood. This selection may be driven by observed couples’ characteristics, such as the timing of couple formation and union duration, or unobserved, such us fecundity of partners. Disregarding the selective entry into parenthood would lead to biased results when studying the transition to the second births.

2.2 Research Hypotheses

Based on theoretical arguments and previous findings, we formulate competing hypotheses based on two different family models. The first one assumes that specialization is the most conducive model for having an additional child. It is based on the Beckerian argument, according to which an imbalance of earning potential in favour of the man leads to a division of labour based on sex roles, which, in turn, may be an efficient way to run a family with kids. From the perspective of this model, we formulate three hypotheses based on three indicators of partners’ socio-economic status. First, the specialization model implies that hypergamous couples (i.e. where the man is more educated than the woman) have higher second birth rates than couples where the woman is more educated than the man or than homogamous couples (Hypothesis 1a). Second, this family model implies that the male partner’s earning potential is positively associated with fertility rates, whereas the female partner’s earning potential is negatively associated with fertility (Hypothesis 1b). Third, it implies that the higher the unemployment risks of the male partner, the lower the second birth rates, whereas female partners’ unemployment risks are positively associated with fertility rates (Hypothesis 1c).

The alternative family model assumes that the pooling of resources is the most efficient family model conducive to fertility. A higher availability of socio-economic resources within the couple may lead to higher second birth rates because it may be easier to afford the—direct and indirect—costs of children. According to Hypothesis 2a, we expect that couples where both partners are highly educated have higher second birth rates than other pairings; consequently the presence of at least one highly educated partner may enhance fertility. Next, we expect that the earning potential of both partners is positively associated with second birth rates (Hypothesis 2b). Finally, the higher the risk of unemployment for both partners, the lower the second birth rates (Hypothesis 2c).

3 Data and Methods

3.1 Sample Selection and Dependent Variables

We used Generation and Gender Surveys (GGS) of the six European countries which collected comparable and suitable information on the field of study (i.e. Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania),Footnote 1 and we focused on respondents born between 1960 and 1987. Since the focus of the study is fertility, we selected couples in which the woman was 15–45 years old at the beginning of the co-residential union.

Our aim is to study how fertility relates to both his and her educational degree in heterosexual couples; thus, we dropped cases where this information was not applicable or not available. First, since we focus on field of study and this is only applicable for people who obtained at least an upper-secondary level, respondents with lower education are not in our study population. Second, since we study fertility at the couple level, we need information about both partners’ education; hence, our study includes only those who were in a co-residential union at the time of interview. From an initial sample of 34,647 respondents, we dropped 9840 respondents who were not living with a partner at the time of the interview. Third, we also dropped couples where information on partners’ educational level and field of study was lacking (n = 1575). Fourth, we excluded couples in which one of the partners had a child from a previous relationship (n = 1622) or in which the first child was already born before the start of the co-residential union (which would yield negative event times; n = 694), as well as cases with missing information about the timing of union formation (n = 39) or first birth (n = 14). Couples formed by partners with missing information on earning potential and unemployment risks were also deleted (n = 119). Overall, our sample counted 15,296 couples.

For first births, we start our observational period at the time of co-residential union, and we censor the couple after 15 years or at the time of the interview, whichever comes first. With regard to higher-order births, the time process is given by the time since the previous birth until the subsequent conception, and censoring occurred after 15 years or interview time, whichever comes first. We dropped respondents with an invalid time to event for survival analysis (n = 80) and obtained a total sample of 12,673 couples at risk for the second births, 7401 couples for the third births. See Table 4 in Appendix for a detailed overview regarding the sample selection.

3.2 Main Independent Variables

3.2.1 Pairing by Level of Education

The educational pairing is defined as the combination of both partners’ levels of educational attainment. We used a four-level compound measure which compares partners’ educational levels: couples where men and women have the same educational attainment, i.e. homogamous couples [(1) “both medium”, (2) “both high”]; (3) hypergamous couples in which the man is highly educated and the woman medium educated; and (4) hypogamous couples in which the woman is highly educated and the man medium educated. Levels of education were harmonized across countries using the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED 1997). The medium category consists of individuals who attained the upper-secondary and post-secondary level (ISCED 3, 4). Respondents and their partners were defined highly educated if they received a bachelor/master/PhD degree (ISCED 5, 6).

3.2.2 Partners’ Earning Potential by Educational Degree

The field of study variable in GGS was collected as an open question and refers to the main discipline of the highest level of education attained. To harmonize the categories across countries and across surveys, we followed the same UNESCO/ISCED guidelinesFootnote 2 as applied in the European Labour Force Surveys (EU-LFS), since we need to link information from EU-LFS to our GGS data. The harmonized variable consists of eight categories, including general/unspecified field (1); humanities and arts (2); social sciences/business/law (3); science and technology (4); agriculture (5); education (6); health and welfare (7); and services (8). A detailed description of each category is available in Table 5 of Appendix.

Following Xie et al. (2003), we define the earning potential as a latent, unobservable, capacity to earn an income. The earning potential has been estimated using the 2014 release of EU-LFS data. The EU-LFS is a large household survey that collects information about the labour force participation of people aged 15 years and older living in private households. Since 2009, EU-LFS collects income information, which is categorized in income deciles and it is applicable only to respondents who declared to be employee in the reference week.

Thus, using 2009–2013 EU-LFS data and by means of OLS regressions, we estimated the earning potential based on a sample of full-time working people aged 20–64, following the equation:

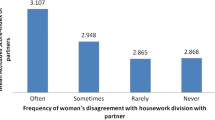

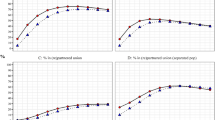

The value of interest for us is the regression coefficient β5 that is estimated separately for each country and sex. This regression coefficient refers to the relative difference in the expected income decile given a certain level of education and discipline of study. Figure 1 shows the size of β5 for medium and highly educated men, relatively to the medium educated men graduated in science and technology, which is the modal category. Similarly, Fig. 2 shows the size of β5 estimated separately for women.

3.2.3 Partners’ Unemployment Risks by Educational Degree

The unemployment risk captures the expected likelihood to be without a job by people who graduated in a particular subject and with a given level of education at any point in time. By means of logistic regressions and EU-LFS data, we estimated unemployment risks Pun of the economically active population, aged 20–64 years, between 2003 and 2013, according to the following equation:

Similarly to the earning potential, our value of interest is the regression coefficient β5, which indicates the relative difference in the likelihood to be unemployed given the level of education and the study discipline. As above, Fig. 3 shows the size of β5 for medium and highly educated men, relatively to the medium educated men graduated in science and technology. The higher the bar below the zero line, the lower the probability of being unemployed in a certain period. In general, a higher level of education is protective against unemployment, with few exceptions (see, e.g. Belgian highly educated men graduated in humanities and arts). Figure 4 shows the estimations for women.

3.3 Control Variables

In all models, we controlled for the age difference between partners: age difference of 0 or 1 (age homogamy); if the woman is older than the man; the man is older than the woman by 2–4 years; or the man is older than the woman 5 years or more. Furthermore, we included a number of covariates that are available for the respondent: the sex, enrolment in education (time-varying); union order. We also control for the type of union, i.e. whether partners got married, as a time-varying covariate. Next, in models of first birth, we accounted for the woman’s age at union formation and its square. For higher-order births, we included the woman’s age at the first birth and its square. In the models for the transition to the third birth, we accounted for the sex of previous children. Finally, we also control for the gender composition of partners’ field of study. We do so to account for the fact that fields of study with higher proportion of women may lead to occupations characterized by a stable employment path and easier ways to combine work with child-rearing. As argued by previous studies, especially for women, these features may be positively associated with birth rates (Hoem et al. 2006a, b; Tesching 2012). We used the UNESCO/OECD/Eurostat database on educationFootnote 3 to obtain the share of women within a field by country and across levels of education. This database has time series from 1998 until 2012 for the absolute number of graduates (both sexes) in each field of study, excluding the general/unspecified field.Footnote 4 We extracted the number of females and the total number of graduates for each field and country, pooling data of ISCED 1997 from level 3 to 6 to calculate the proportion of women by country and field. We calculated the proportion of women by field, country and year, and we averaged over the years available for each country; Fig. 6 in Appendix shows the gender composition of each field of study by country. Table 1 gives information on the independent variables and the number of events occurring for each country sample.

3.4 Analytical Strategy

We apply piecewise linear hazard models to estimate the effect of pairing by level of education and field of study on the first, second, and third birth rates, using the aML software (Lillard and Panis 2003). When studying the effect of education on higher-order births, several studies argued that it is important to account for the selection into parenthood (Kravdal 2001, 2007; Kravdal and Rindfuss 2008; Kreyenfeld 2002). Following Kravdal (2001), we controlled for the selectivity into parenthood by modelling the first, second and third births jointly, where birth episodes are nested within couples. The system of equations can be formally displayed as follows:

The superscripts 1, 2 and 3 refer to the equation for the first, second and third births, respectively, and ln h(t) is the log-hazard of occurrence at time t. In the equation for the first birth, γ′T(t) is a piecewise linear transformation of time since household formation, with nodes at 2, 3, 5, 7 and 10 years. For the second and third births, γ′T(t) is a piecewise linear transformation of time since the previous birth, with nodes at 2, 4, 6 and 11 years. The covariate profile (both for fixed and time-varying covariates) is given by β′X(t), which shifts the baseline hazard up or down. The random variable ε represents the unobserved heterogeneity term, which is assumed to be normally distributed with mean 0 and variance σ2, which will be estimated. The distribution of ε is approximated by ten integration points in our models. We present models that have been run separately by country. Note that we included the transition to the third births in our system of equation to improve the estimation of the random effect included in our model. Yet, we will discuss second birth estimates only, since they are the focus of this study. The first and third births estimates are available in Electronic Supplementary Material.

4 Results

Tables 2 and 3 show the results concerning the effects of the main independent variables on the transition to the second birth. For each main independent variable, we ran models excluding the gender composition of partners’ field of study and including it. The effects of other control variablesFootnote 5 are in line with our expectations, but discussing them is beyond the focus of the paper. Full models are available in Electronic Supplementary Material.

4.1 The Effect of Educational Pairing

Table 2 shows the effect of educational pairing on the transition to the second births separately country by country. In model 1 (M1), we do not control for the gender composition of the field of study in which partners graduated. In M1, for the majority of countries which pertain to Central and Eastern Europe, we find that couples with highly educated women tend to have lower birth rates compared to couples with medium educated women, irrespective of the male partner’s education. In most of the countries, the sign of the effects supports Hypothesis 1a based on the specialization family model, according to which hypergamous couples have higher fertility rates relative to other pairings. Yet, these results are not statistically significant. The Belgian results support Hypothesis 2a, based on the pooling of resources family model: the presence of at least one highly educated partner has a positive effect on second birth rates, and couples with both partners highly educated have the highest second birth rates.

When we control for the type of field of study of the partners in model 2 (M2), results generally remain in line with what we found in M1. However, it is noticeable that, in some countries, the inclusion of this variable moderates the association between the educational pairings and second birth rates. On top of the level of education, the gender composition of the study field also matters. For instance, in Belgium, the effect of educational pairing loses strength. Here, couples formed by women who choose a female-dominated study discipline tend to have higher second birth rates. Similarly, in Poland, the negative effect of woman’s high level of education on second birth rates is to some extent reduced if the woman graduated in a female-dominated field. In Austria, highly educated homogamous couples have almost 32% higher second birth rates than the reference category after controlling for the gender composition of partner’s study field (exp(0.28) = 1.32). These results could perhaps be explained by the fact that female-dominated fields of study tend to lead to occupations that are more compatible with child-rearing.

4.2 The Role of Earning Potential and Unemployment Risks

Table 3 shows the results concerning the effects of earning potential and unemployment risks of both partners on the transition to the second births. Models 3 and 4 look at the role of earning potential, where the former (M3) does not control for the gender composition of partners’ study field, while the latter (M4) does. Overall, little changes between M3 and M4, in both models, a unit increase in the female partner’s earning potential has a negative effect on second birth rates in Bulgaria, Poland and Romania, whereas it has a positive effect in Belgium. The male partner’s earning potential has a positive effect on the transition to second births in Belgium. The results for Belgium clearly support Hypothesis 2b implied by the pooling of resources family model. In the other countries, however, the findings are more mixed. We do not find clear support for hypotheses 1b or 2b, given that the sign and statistical significance of the effects of partners’ earning potential are not consistent with these hypotheses. In Central and Eastern European countries, we found a negative effect of the female-partner’s earning potential on birth rates, a finding supporting Hypothesis 1b. However, results for the male partner are not statistically significant.

Models 5 and 6 look at the role of unemployment risks. In M5, we found that higher unemployment risks of both partners tend to inhibit transition to the second birth in Austria and Belgium. This is line with Hypothesis 2c, based on the pooling of resources family model. In Lithuania, we do not find a statistical significant effect of partners’ unemployment risks. In Bulgaria, Poland and Romania, we find that higher unemployment risks of the female partner are positively associated with second birth rates, a finding that supports Hypothesis 1c. In M6, when we include the variable indicating the gender composition of partners’ fields of study, results tend to remain the same, at least in the direction of the effects.

4.3 Alternative Models’ Specifications

As mentioned in the data section, we have to deal with a selective sample, i.e. we only observe fertility histories of those unions intact at the time of interview. To check whether differences in union duration may alter the results, we analysed the data separately by union’s cohort. The youngest cohorts are more heterogeneous in terms of union stability given that their time of union formation is closer to the interview, and thus, they may represent a less selective group. The analyses based on the sample of the youngest cohorts showed a very similar pattern to the results presented here. However, we should keep in mind that the sample size for these is smaller; thus, estimates tend to be more uncertain.

Next, to check whether our results are sensitive to the differential in earning potentials and unemployment risks between men and women, we have ran models using male partners’ estimates of earning potential and unemployment risks also for the female partners. The results are in line with those showed here.

We have also verified whether our conclusions would differ if we take into account that earning potential and unemployment risk would be predicted to be different for men and women with and without children. We have re-estimated both factors using a model in the first stage that takes into account the number of children younger than 15 years in the household. (A more comprehensive measure of the fertility history was not possible with the data at hand.) The results, available upon request, did not alter our conclusions.

Additionally, recognizing that the data we used to estimate the unemployment risk were sometimes far off in time from the interview date, we have re-estimated our models using a subset of unemployment data closer to the GGS interviewing period, namely unemployment risks for the years 2003–2008 instead of 2003–2013. The results of the re-estimation do not lead to any different conclusions, except that in Lithuania, we found a statistically significant negative effect of the male partner’s unemployment risks on second birth rates.

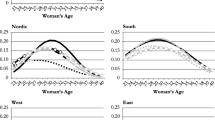

Finally, Fig. 5 compares the results obtained from a model that accounts for time constant unobserved factors of the couple (joint panel in Fig. 5), which is the one applied in this paper, and a model without random effect (separate panel in Fig. 5). In most of the countries, the separate modelling tends to inflate the positive effect of women’s education. This is due to the fact that couples who got their first child earlier than their average peers also enter the risk set for second childbearing earlier.

5 Discussion

In recent years, scholars have increasingly investigated the association between male partners’ characteristics and fertility, which may be related to the increased awareness of the importance of gender equality within the couple and in society for fertility (McDonald 2000; Huinink and Kohli 2014; Esping-Andersen and Billari 2015; Goldscheider et al. 2015). Since parenthood requires parental investment from both men and women, scholars have acknowledged the importance of keeping a couples’ perspective in fertility research. Still, studies focusing on the couple as main unit of analysis and considering both partners characteristics have remained relatively scarce.

This paper has contributed to the emerging literature on the role of both partners’ characteristics for fertility in two ways. First, we propose an approach to account for the economic aspects of education, such as income and employment, in a way that incurs less endogeneity issues compared to when actual earnings or unemployment are entered into the equation. Second, in our study about couples’ transition to second births, we have accounted for the selection into parenthood. While previous studies have focused either on first- or higher-order births separately, we were able to account for unobserved characteristics of the couple that often drive the selection into parenthood by modelling parities progressions jointly.

Using data from six European countries, we tested hypotheses derived from two different family models. The specialization model is based on the traditional gender division of labour, whereas the pooling of resources model is based on the dual-earner family. Overall, our findings very clearly differ by country and they do not support hypotheses deriving from only one family model. We found that Belgium is the only country where all hypotheses derived from the pooling of resources model are supported. Here, the highly educated homogamous couples have the highest second birth rates and the presence of at least one highly educated partner increases fertility rates (Hypothesis 2a). Next, both his and her earning potential are positively associated with second birth rates (Hypothesis 2b), whereas his and her unemployment risks are negatively associated with fertility (Hypothesis 2c).

In Austria, results are mixed: we found that highly educated homogamous couples have the highest second birth rates relative to other pairings, but only when we control for the gender composition of partners’ field of study. This is related to the fact that couples where the male partner graduated in a female-dominated field of study tend to have lower second birth rates in Austria.

In Central–Eastern European countries, if we found statistically significant effects, they tend to support hypotheses based on the specialization family model. In Bulgaria, Poland and Romania, we found that couples where the woman has a high level of education have the lowest second birth rates compared to other couples. Additionally, female partners’ earning potential is negatively associated with fertility rates, whereas the opposite holds for unemployment risks, findings which are line with hypotheses 1b and 1c.

In contrast to previous studies, we aimed to explicitly consider two aspects entailed by an educational degree to better understand fertility dynamics at the couple level. Unfortunately, due to data availability, our categories of study disciplines are relatively broad; thus, we could not account for several aspects entailed by an educational degree. We mainly considered the economic dimension, leaving the cultural aspects on the background. This choice might have limited the interpretation of our results, and future research could find ways to disentangle between the cultural and economic aspects. For instance, our two-step approach could be improved if we could have the data to also estimate cultural traits of educational degrees in the first step.

Other limitations of this paper should be mentioned. First, our sample suffers from a selection bias since we only included unions that were intact at interview time. As a result, our sample over-represents stable unions, which are more conducive to childbearing. The selectivity would not be a problem if dissolution rates were random across educational pairings. However, divorce studies suggest that educational pairings are correlated with divorce risks (Kalmijn 2003; Mäenpää and Jalovaara 2014; Theunis et al. 2018). Changes over time have been observed, and women’s positive educational gradient in divorce rates is flattening out (Härkönen and Dronkers 2006; Matysiak et al. 2014). Country-specific studies showed that educational hypogamy does not necessarily lead to higher divorce rates, especially with regard to unions formed in the 1990s and afterwards (see Schwartz and Han (2014) for the USA and Theunis et al. 2018 for Belgium). To check the sensitivity of our results to a possible sample-selection effect, we ran alternative models only considering unions formed in the 1990s and onwards. Overall, results turned out to be in line with the patterns presented in this paper. However, it is also possible that our results reflect this selection only for some countries. For instance, we have seen that the pooling of resources family model seems to be adequate to describe fertility behaviour in the Belgian context but not in the Bulgarian, Polish or Romanian ones. One explanation for this is that in the latter contexts, results reflect the selection driven by differentials in union dissolution rates across educational pairings, whereas this is not the case of Belgium, where this gradient has been disappearing (Theunis et al. 2018). If data allow, in the future, it will be useful to prospectively look at couples’ union formation and dissolution.

Further investigations are necessary to really understand the role of educational pairing for fertility dynamics. Here, we point out two major challenges for future research. First, from the micro-level analysis of fertility, the challenge will be to address the role of reverse causation between education and fertility (and fertility intentions). We acknowledge that education and fertility may be jointly determined, since individuals who have less of a desire to have children will simultaneously prefer to invest more in education. Decisions concerning education and fertility may therefore be part of the same family building process. Still, the couple-level approach entails that educational and partnerships trajectories of both partners are simultaneously taken into account. Childbearing may impede acquiring high levels of education, also affecting the educational pairing that lower educated individuals may form. To fully address these issues from a couple-level perspective, detailed data on both partners’ educational and partnership trajectories are needed.

The second challenge for future research on educational pairing and fertility will be to reconcile macro- and micro-levels of analysis. In our study, we have tested the same hypotheses in six different contexts, without accounting for the country differences and changes over time. Simplifying our results a lot, we found that, relatively to the medium educated couples, more educated couples have higher fertility rates in Western European countries, whereas lower educated couples have higher fertility in Central and Eastern European countries. Additionally, the effect of unemployment risk on second birth rates tends to be gender specific in the latter set of countries and gender neutral in the former group. In short, we found some evidence of the specialization family model as stimulating fertility in Central and Eastern European but not in Western European countries.

These patterns suggest that fertility responses depend on the specific conditions of family and work reconciliation. These conditions consist in the intersection of family policies, labour market structures and gender norms, which vary across European countries (Matysiak and Węziak-Białowolska 2016). In the last decade, extensive emphasis has been given to the roles of men and women within families which, in turn, have been also changing over time. To the extent that men become more involved in the family sphere, the pooling of resources family model may stimulate fertility (Goldscheider et al. 2015). Beyond gender role differences, our results may also reflect the different levels of economic security within our set of countries (Matysiak et al. 2018). Thus, convergence towards a pooling of resources family model which potentially may stimulate fertility will depend on several interacting factors. Future studies should cast more light on these factors.

Notes

We excluded France because categories of education, health and welfare and services were not included, harming the comparability of results. We also had to exclude Norway because it was not possible to estimate the earning potential by means of the European Labour Force Surveys, given that the income variable for this country was not available.

http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Pages/international-standard-classiication-of-education.aspx accessed on the 14 September 2015.

This database is an administrative data collection that is administered jointly by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics (UNESCO-UIS), the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Statistical Office of the European Union (EUROSTAT).

Since Eurostat does not provide information on the general/unspecified field of study, we calculated the proportion of women in this category using GGS data themselves, considering all men and women born between 1960 and 1987 with at least upper-secondary degree.

Control variables for the transition to the second birth include duration splines, woman’s age at the first birth and its square, union’s cohorts, respondent’s sex, respondent’s enrolment, union order of the respondent, type of union, age difference between partners.

References

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Becker, G. S. (1991). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Begall, K. (2013). How do educational and occupational resources relate to the timing of family formation? A couple analysis of the Netherlands. Demographic Research,29(October), 907–936.

Begall, K., & Mills, M. C. (2013). The influence of educational field, occupation, and occupational sex segregation on fertility in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review,29, 720–742.

Billari, F., & Kohler, H.-P. (2004). Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe. Population Studies,58(2), 161–176.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2016). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. IZA Discussion Paper Series, no. 9656.

Charles, M., & Bradley, K. (2009). Indulging our gendered selves? Sex segregation by field of study in 44 countries. American Journal of Sociology,114(4), 924–976.

Corijn, M., Liefbroer, A., & de Gierveld, J. (1996). It takes two to tango, doesn’t it? The influence of couple characteristics on the timing of the birth of the first child. Journal of Marriage and the Family,58(1), 117–126.

De Hauw, Y., Grow, A., & Van Bavel, J. (2017). The reversed gender gap in education and assortative mating in Europe. European Journal of Population, 33(4), 445–474.

DiPrete, T. A., & Buchmann, C. (2006). Gender-specific trends in the value of education and the emerging gender gap in college completion. Demography, 43(1), 1–24.

Dribe, M., & Stanfors, M. (2010). Family life in power couples: Continued childbearing and union stability among the educational elite in Sweden, 1991–2005. Demographic Research,23, 847–878.

Esping-Andersen, G., & Billari, F. C. (2015). Re-theorizing family demographics. Population and Development Review,41(1), 1–51.

Esteve, A., García-Román, J., & Permanyer, I. (2012). The gender-gap reversal in education and its effect on union formation: The end of hypergamy? Population and Development Review,38, 535–546.

Frejka, T. (2008). Overview Chapter 2: Parity distribution and completed family size in Europe. Demographic Research,19(July), 139–170.

Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behaviour. Population and Development Review,41(2), 207–239.

Grow, A., & Van Bavel, J. (2015). Assortative mating and the reversal of gender inequality in education in Europe—An agent-based model. PLoS ONE,10(6), e01.

Gustafsson, S., & Worku, S. (2006). Assortative mating by education and postponement of couple formation and first birth in Britain and Sweden. In S. Gustafsson, & A. Kalwij (Eds.), Education and postponement of maternity. Economic analysis for industrialized countries (pp. 259–284). Dordrecht: Springer.

Harkonen, J., & Dronkers, J. (2006). Stability and change in the educational gradient of divorce. A comparison of seventeen countries. European Sociological Review,22(5), 501–517.

Hobcraft, J., & Kiernan, K. (1995). Becoming a parent in Europe: Discussion Paper WSP/116, Welfare State Programme. London: The Toyota Centre London School of Economics.

Hoem, J. M., Neyer, G., & Andersson, G. (2006a). Education and childlessness. Demographic Research,14(May), 331–380.

Hoem, J. M., Neyer, G., & Andersson, G. (2006b). Educational attainment and ultimate fertility among Swedish Women Born in 1955–59. Demographic Research,14, 381–404.

Huinink, J., & Kohli, M. (2014). A life-course approach to fertility. Demographic Research, 30, 1293–1326.

Jalovaara, M., & Miettinen, A. (2013). Does his paycheck also matter? Demographic Research,28(April), 881–916.

Kalmijn, M. (2003). Union disruption in the Netherlands: Opposing influences of task specialization and assortative mating? International Journal of Sociology,33(2), 36–64.

Klesment, M., & Van Bavel, J. (2017). The reversal of the gender gap in education, motherhood, and women as main earners in Europe. European Sociological Review, 33(3), 465–481.

Klesment, M., Puur, A., Rahnu, L., & Sakkeus, L. (2014). Varying association between education and second births in Europe: Comparative analysis based on the EU-SILC data. Demographic Research,31(1), 813–860.

Kravdal, Ø. (2001). The high fertility of college educated women in Norway. Demographic Research,5(December), 187–216.

Kravdal, Ø. (2007). Effects of current education on second- and third-birth rates among Norwegian women and men born in 1964: Substantive interpretations and methodological issues. Demographic Research,17(November), 211–246.

Kravdal, O., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2008). Changing relationships between education and fertility: A study of women and men born 1940 to 1964. American Sociological Review,73(5), 854–873.

Kreyenfeld, M. (2002). Time squeeze, partner effect or self-selection? Demographic Research,7(July), 15–48.

Lappegård, T., & Rønsen, M. (2005). The multifaceted impact of education on entry into motherhood. European Journal of Population,21(1), 31–49.

Lappegard, T., Ronsen, M., & Skrede, K. (2011). Fatherhood and fertility. Fathering,9(1), 103–120.

Lillard, L. A., & Panis, C. W. A. (2003). aML: Multilevel multiprocess statistical software, version 2.0. Los Angeles, CA: EconWare.

Mäenpää, E., & Jalovaara, M. (2014). Homogamy in socio-economic background and education, and the dissolution of cohabiting unions. Demographic Research,30(June), 1769–1792.

Martín-García, T. (2009). ‘Bring men back in’: A re-examination of the impact of type of education and educational enrolment on first births in Spain. European Sociological Review,25(2), 199–213.

Martín-García, T., & Baizán, P. (2006). The impact of the type of education and of educational enrolment on first births. European Sociological Review,22(3), 259–275.

Matysiak, A., Sobotka, T., & Vignoli, D. (2018). The Great Recession and fertility in Europe: A sub-national analysis. Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers VID WP 02/2018.

Matysiak, A., Styrc, M., & Vignoli, D. (2014). The educational gradient in marital disruption: A meta-analysis of European research findings. Population Studies,68(2), 197–215.

Matysiak, A., & Węziak-Białowolska, D. (2016). Country-specific conditions for work and family reconciliation: An attempt at quantification. European Journal of Population,32(4), 475–510.

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 26(3), 427–439.

Nitsche, N., Matysiak, A., Van Bavel, J., & Vignoli, D. (2018). Partners’ educational pairings and fertility across Europe. Demography,38, 1–36.

Oppenheimer, V. (1988). A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology,94(3), 563–591.

Oppenheimer, V. (1994). Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review,20(2), 293–342.

Osiewalska, B. (2017). Childlessness and fertility by couples’ educational gender (in)equality in Austria, Bulgaria, and France. Demographic Research,37(August), 325–362.

Puur, A., Oláh, L. S., Tazi-Preve, M. I., & Dorbritz, J. (2008). Men’s childbearing desires and views of the male role in Europe at the dawn of the 21st century. Demographic Research, 19, 1883–1912.

Reimer, D., Noelke, C., & Kucel, A. (2008). Labour market effects of field of study in comparative perspective: An analysis of 22 European countries. International Journal of Comparative Sociology,49(4–5), 233–256.

Schwartz, C. R., & Han, H. (2014). The reversal of the gender gap in education and trends in marital dissolution. American Sociological Review, 79(4), 605–629.

Singley, S. G., & Hynes, K. (2005). Transitions to parenthood: Work-family policies, gender, and the couple context. Gender & Society,19(3), 376–397.

Sobotka, T., & Beaujouan, E. (2014). Two is best? The persistence of a two-child family ideal in Europe. Population and Development Review, 40(3), 391–419.

Tesching, K. (2012). Education and fertility. Dynamic interrelations between women’s educational level, educational field and fertility in Sweden. Stockholm University Demography Unit—Dissertation Series, No 6.

Testa, M., Cavalli, L., & Rosina, A. (2014). The effect of couple disagreement about child-timing intentions: A parity-specific approach. Population and Development Review,40(March), 31–53.

Theunis, L., Schnor, C., Willaert, D., & Van Bavel, J. (2018). His and her education and marital dissolution: Adding a contextual dimension. European Journal of Population,34(4), 663–687.

Trimarchi, A., & Van Bavel, J. (2017). Education and the transition to fatherhood: The role of selection into union. Demography,54(1), 1–42.

Trimarchi, A., & Van Bavel, J. (2018). Pathways to marital and non-marital first birth: The role of his and her education. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research,2017(15), 143–179.

Van Bavel, J. (2010). Choice of study discipline and the postponement of motherhood in Europe: The impact of expected earnings, gender composition, and family attitudes. Demography,47(2), 439–458.

Van Bavel, J. (2012). The reversal of gender inequality in education, union formation and fertility in Europe. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research,10, 127–154.

Van Bavel, J., & Rózańska-Putek, J. (2010). Second birth rates across Europe: Interactions between women’s level of education and child care enrolment. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 8(1), 107–138.

Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2001). Field of study and social inequality. Four types of educational resources in the process of stratification in the Netherlands. Catholic University of Nijmegen.

Vignoli, D., Drefahl, S., & De Santis, G. (2012). Whose job instability affects the likelihood of becoming a parent in Italy? A tale of two partners. Demographic Research,26(January), 41–62.

Xie, Y., Raymo, J. M., Goyette, K., & Thornton, A. (2003). Economic potential and entry into marriage and cohabitation. Demography,40(2), 351–367.

Zeman, K., Beaujouan, É., Brzozowska, Z., & Sobotka, T. (2018). Cohort fertility decline in low fertility countries: Decomposition using parity progression ratios. Demographic Research,38(1), 651–690.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement No. 312290 for the GENDERBALL project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Trimarchi, A., Van Bavel, J. Partners’ Educational Characteristics and Fertility: Disentangling the Effects of Earning Potential and Unemployment Risk on Second Births. Eur J Population 36, 439–464 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-019-09537-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-019-09537-w