Abstract

This research studied the relationship between parenthood and life satisfaction in Switzerland. We tested predictions derived from set-point theory, the economic model of parenthood, the approaches that underscore work–family conflict and the psychological rewards from parenthood, and the ‘taste for children’ theory. We used Swiss Household Panel data (2000–2018) to analyse how life satisfaction changed during parenthood (fixed-effects regression) separately for a first child and a second child, mothers and fathers, and various socio-demographic groups. Our results showed that having a second child, which is common in Switzerland, correlates negatively with mothers’ life satisfaction. The observed patterns are consistent with the idea that mothers’ life satisfaction trajectories reflect work–family conflict. We found partial support for the set-point and the ‘taste for children’ theories. Our results did not support the approaches that emphasize the importance of psychological rewards from parenthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the research on the link between parenthood and life satisfaction has flourished. This comes as no surprise given the importance of this topic, especially in low-fertility societies. Studying the well-being consequences of parenthood helps researchers understand fertility choices (Kohler et al. 2005; Baranowska and Matysiak 2011; Billari 2009; Myrskylä and Margolis 2014; Aassve et al. 2012), informs whether people manage to satisfy the common aspiration to become a parent (Baumeister 1991), and suggests policies to improve the conditions for parenthood (Aassve et al. 2012; Billari 2009).

The past research on the relationship between parenthood and life satisfaction has produced contradictory results. The use of various data (e.g. cross-sectional vs. longitudinal), methods (e.g. those that control for individual heterogeneity or not), and focus on various country contexts has shown that parents are happier (e.g. Aassve et al. 2012; Pollmann-Schult 2014; Mikucka 2016), less happy (e.g. Stanca 2012; Hansen 2012), or (at least in the long run) just as happy as childless people (e.g. Clark et al. 2008; Myrskylä and Margolis 2014). The divergent findings and the complexity of interactions between parenthood and other variables suggest that our understanding of this relationship is still partial. The current debate, in our view, is subject to two main shortcomings. Our paper attempts to overcome, at least in part, both of these shortcomings.

First, in methodological terms, the longitudinal evidence available so far has been based on only a few country contexts. The attention of researchers has focused mostly on Germany (Baetschmann et al. 2016; Myrskylä and Margolis 2014; Pollmann-Schult 2014) and—to a lesser extent—on Great Britain (Myrskylä and Margolis 2014), Poland (Baranowska and Matysiak 2011), Australia (Parr 2010) and Russia (Mikucka 2016). Therefore, the first goal of this study is to extend the empirical longitudinal evidence to a social context where the relationship between parenthood and life satisfaction has not been systematically investigated thus far, i.e. Switzerland. Extending the empirical evidence is useful as such. It helps us to understand whether the results differ across social contexts and whether the discrepancies among the results of various studies reflect merely the differences among social contexts. However, studying the case of Switzerland offers an additional advantage. Gender roles in Switzerland are predominantly traditional and—despite its wealth—the country offers only limited state support for parenthood, which aggravates the economic costs of parenthood and the work–family conflict for women. For these reasons, it is plausible that the effect of parenthood on life satisfaction is more negative in Switzerland than elsewhere.

The second shortcoming of the current debate is that past studies only to a limited extent derived empirical predictions from theoretical models. In particular, they only rarely systematically studied the theoretical predictions regarding the effects of a child’s age, parity, parental gender, and socio-demographic characteristics. Therefore, the second goal of our analysis is a rigorous test of the predictions derived from the set-point theory, the economic model of parenthood, the approach that underscores work–family conflict, the psychological rewards from parenthood, and the approach that emphasizes the ‘taste for children.’ This allows us to verify how universal these theoretical models are and to identify the empirical patterns that cannot be explained by existing theories.

2 Theories of the Parenthood’s Effect on Life Satisfaction

The literature has proposed various frameworks to conceptualize the link between parenthood and life satisfaction. Below, we describe these theoretical approaches, and we derive predictions about the changes of parental life satisfaction associated with the ageing of a child, the differences between having a first child and a second child, the gender differences between parents, and the differences among social groups.

Set-point theory According to set-point theory, the effect of any event on life satisfaction is only temporary. After an event, whether it is positive or negative, people adapt to the new situation, and their life satisfaction returns to the pre-event ‘baseline’ level. This baseline level of life satisfaction changes little over time and is shaped by genetic factors and early socialization rather than by events experienced over the life course (Headey and Wearing 1989). Accordingly, set-point theory predicts that although a birth of a child may affect parental life satisfaction, in the long run parenthood has no effect. This pattern should be universal; that is, among men and women and among people from various social strata, parenthood should have no effect on life satisfaction in the long run.

Economic costs The economic approach emphasizes the financial costs of parenthood, specifically both the direct financial costs and the opportunity costs. The direct costs, especially the costs of childcare, may be substantial particularly in countries where the state support for parents is limited. The opportunity costs of parenthood refer to the loss of income due to work interruptions and a concomitant worsening of career opportunities. These costs are particularly high for families with young children (Becker 1991) where a mother interrupts employment. The economic approach implies that if childcare is scarce or expensive, the care-intense period of parenthood, i.e. until school age, affects parental life satisfaction more negatively than other periods. Gender differences should be negligible as long as parental incomes are pooled.

Work–family conflict Parenthood also creates a work–family conflict (Gatrell et al. 2013; Greenhaus et al. 2003; Currie and Eveline 2011). If parents face difficulties in combining parenthood with employment, this may—independently from the decreased incomes—create stress and lower their life satisfaction. Work–family conflict is plausibly strongest during the care-intense stages of parenthood; therefore, parental life satisfaction should be lowest in this period. As parenthood is typically women’s responsibility, women tend to experience stronger work–family conflict than men experience; thus, their life satisfaction should be more negatively affected. Especially, higher-educated women, whose careers may be more rewarding than the careers of lower educated women, may experience considerable work–family conflict, with negative consequences to their life satisfaction.

Psychological rewards The demands–rewards theory postulates that the economic costs of parenthood are counterbalanced by psychological rewards (self-esteem, self-efficacy, and parental satisfaction), which tend to be highest among parents of children under the age of 5 years (Nomaguchi 2012). If parental life satisfaction reflects psychological rewards from parenthood, then life satisfaction should increase when people become parents and should be highest during the care-intense stage and decline around a child’s school age when peers gain importance in the child’s life and the emotional intimacy in the parent–child relationship declines (Pollmann-Schult 2014; Nomaguchi 2012). Another prediction is that parenthood should increase women’s life satisfaction more than men’s life satisfaction, because women are more involved in child rearing than men.

‘Taste for children’ Individual preferences or ‘taste for children’ is another factor that potentially shapes parental life satisfaction (Kravdal 2014). According to this approach, the match between personal tastes and experiences rather than a mere fact of having a child or not plays a major role in parental life satisfaction. Having more children and having them quickly one after another may indicate a stronger preference for parenthood; therefore, people who ultimately have more children should derive more life satisfaction from parenthood than people who have fewer children. Moreover, if women have more control over fertility than men, parenthood may reflect their preferences more closely than the preferences of men, which contributes to a more positive effect of parenthood on life satisfaction among women.

3 Previous Research and Our Hypotheses

The research has accumulated vast empirical evidence on the relationship between parenthood and life satisfaction. Cross-sectional studies, which compared the life satisfaction of parents and childless people, have shown mixed results, with some studies pointing to a positive (e.g. Aassve et al. 2012) and other studies pointing to a negative (e.g. Margolis and Myrskylä 2011; Stanca 2012) correlation between parenthood and life satisfaction. Self-selection to parenthood limits the causal interpretation of these results and may contribute to the discrepancies among various studies. Indeed, studies that use longitudinal data and studies that attempt to control for individual fixed effects have drawn a more consistent picture. They documented, among other findings, how parental life satisfaction changes with the ages of children and with parities, and they provided evidence on social and gender differences.

Stages of parenthood The period directly after the birth of a first child typically stands out with a systematically elevated life satisfaction (Myrskylä and Margolis 2014; Pollmann-Schult 2014; Baetschmann et al. 2016; Frijters et al. 2011; Mikucka 2016), especially among women. This increase is preceded by the anticipation effect, i.e. an increase that occurs one or two years before the birth, which may reflect, for example, a satisfying partnership or a career advancement that increases a couple’s probability of having a child. After the birth, parental life satisfaction typically returns to the pre-anticipation level; complete adaptation was already reported for parents of one- and 2-year-old children (Mikucka 2016; Myrskylä and Margolis 2014; Pollmann-Schult 2014; Frijters et al. 2011). The nature and meaning of this decline is probably the most controversial issue in this literature, as it may reflect the (temporarily increased) costs of parenthood and work–family conflict or it may signify a long-term adaptation. Only few studies have analysed parental life satisfaction at older ages of children. Their results are mixed. On the one hand, Pollmann-Schult (2014) showed no further decline, and Mikucka (2016) showed a long-term increase in parental life satisfaction after a child entered school. On the other hand, some research has concluded that parenthood has no long-term effect on life satisfaction (Myrskylä and Margolis 2014; Frijters et al. 2011; Clark et al. 2008).

Hypothesis 1a Due to the adaptation mechanism, parenthood has no long-term effect on life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 1b Due to the economic costs of parenthood, life satisfaction declines during the care-intense stage, and mothers and fathers are similarly affected.

Hypothesis 1c Due to the work–family conflict triggered by parenthood, life satisfaction declines during the care-intense stage, and the decline is stronger among mothers than among fathers.

Hypothesis 1d Due to the psychological rewards of parenthood, life satisfaction increases with parenthood, especially during the care-intense stage.

Parity and fertility pattern A majority of studies have limited their interest to a first birth; thus, the evidence on the differences between parities is limited. Among the exceptions, some analyses have suggested that having a first child is a more positive experience than having subsequent children (Myrskylä and Margolis 2014; Kohler et al. 2005). Other studies have suggested that subsequent children may have less negative (or more positive) effects on parental life satisfaction than a first child (Angeles 2010; Mikucka 2016). The differences in parental life satisfaction according to the fertility pattern of a couple were studied by Margolis and Myrskylä (2015), who showed that a smaller drop in life satisfaction after a first birth correlated with a higher hazard of having a second child. Margolis and Myrskylä interpreted their results as the effect of early parenthood experiences on future fertility decisions. However, studying the differences among parents with various fertility patterns may also be a tool to verify the predictions of the ‘taste for children’ theory.

Hypothesis 2 People who have a stronger ‘taste for children’ (i.e. parents who have more children and parents who have them quickly one after another) experience a greater increase in life satisfaction in response to parenthood.

Mothers and fathers Part of the research has studied gender differences without considering the various ages of children. These studies have generally shown a more positive effect of parenthood on women’s than on men’s life satisfaction (Kohler et al. 2005; Baranowska and Matysiak 2011). In addition, Myrskylä and Margolis (2014), who accounted for the various ages of children, showed that after a birth, women’s life satisfaction increased more than men’s life satisfaction consistently with women’s stronger control over fertility, which results in a better match between their fertility behaviour and their ‘taste for children.’ In contrast, an analysis by Mikucka (2016) demonstrated that during the care-intense stages of parenthood, mothers’ life satisfaction declined more than men’s life satisfaction, which plausibly reflected the work–family conflict experienced by women.

Hypothesis 3 If women have greater control over fertility than men, their life satisfaction should increase with parenthood more than men’s life satisfaction, independently of the child’s age.

Social differences Plausibly, life satisfaction consequences of parenthood differ among social strata. The research has shown that higher education correlates with a greater increase in life satisfaction during parenthood only among men (Myrskylä and Margolis 2014), which perhaps reflects a stronger ‘taste for children’ of highly educated men or their greater psychological rewards from parenthood. Among women, higher education correlated with a greater decline of life satisfaction after a birth (Myrskylä and Margolis 2014), which may indicate a stronger work–family conflict. This result is plausibly driven by the longer employment hours of higher-educated women, but to the best of our knowledge, the past research did not address this issue. The moderating effect of income has been investigated relatively rarely. Among the exceptions, Mikucka (2016) showed that among women, a high income at first birth correlated with a stronger increase in life satisfaction after a birth, which suggests that economic resources play a buffering role.

Hypothesis 4a Due to work–family conflict, the life satisfaction among women declines during the care-intense stage of parenthood, and the decline is stronger among higher-educated women than among lower-educated women.

Hypothesis 4b Due to work–family conflict, the life satisfaction among women declines during the care-intense stage of parenthood, and the decline is stronger among women who work longer hours than among women who work shorter hours.

Hypothesis 5 Due to the economic costs of parenthood, people with higher incomes derive more life satisfaction from parenthood than people with lower incomes.

4 The Context of Switzerland

The life satisfaction consequences of parenthood in Switzerland have rarely been analysed before (to a limited extent, it has been studied by: Anusic et al. 2014; Mikucka and Rizzi 2016; Roeters et al. 2016). However, Switzerland is an interesting case. As Switzerland offers low state support for families with children, the effect of parenthood on life satisfaction may be particularly negative.

The total fertility rate in Switzerland has the value of approximately 1.5 (which is somewhat lower than the European Union average of 1.58) and shows a slight increase after early 2000 when it decreased to approximately 1.4. The fertility pattern in Switzerland is quite specific and comprises three components. First, the transitions to second births are frequent, comparable to the Scandinavian countries and Ireland (Vono de Vilhena and Matthiesen 2014), and births are usually closely spaced. Second, Switzerland stands out with relatively high childlessness; approximately 20% of people have no children at the end of their reproductive life (Burkimsher and Zeman 2017), and childlessness is socially accepted. Finally, people become parents relatively late in their life (Tanturri et al. 2016), and parenthood is strictly connected to marriage, with the share of births out of wedlock being among the lowest in Europe.

The state support for parenthood in Switzerland is low. Only 8.5% of three-year-old children attend preschool compared with 68% in the EU-27 countries (OECD 2015, data for 2010). Not surprisingly, the proportion of children aged 0–2 years who use informal childcare (e.g. grandparents, see: Le Goff et al. 2011) is one of the highest in Europe (OECD 2015). The spending on childcare and preschool programmes is the lowest of all the OECD countries and corresponds to 0.2% of GDP. Not surprisingly, the cost of childcare as a percentage of household income is the highest in the OECD countries, and it reaches the value of approximately 50% (vs. 11% in the OECD countries; OECD 2015). Moreover, the entry into school is problematic due to the scarcity of supervised lunch programmes or afterschool care services. Maternity leave in Switzerland, which is 14 weeks at the federal level, is one of the shortest in Europe, and the country does not offer paternity and parental leave at all (OECD 2015; Valarino et al. 2017). The main instrument of reconciliation between work and family life is women’s part-time employment (Levy et al. 2006; Widmer and Ritschard 2009), and 45.6% of women work part-time (in Europe, this share is higher only in the Netherlands: 60.7%; OECD 2015, data for 2012).

5 Data and Methods

5.1 Data

We use data from the Swiss Household Panel (SHP, see: Tillmann et al. 2016). The data are collected annually by using computer-assisted telephone interviewing. The survey started in 1999 with a stratified random sample of private households from the Swiss telephone directory (Voorpostel et al. 2015), and refreshment samples were initiated in 2004 and 2013. The SHP follows the respondents, their children, and (since 2007) the respondents’ cohabitants who leave the original household until death or institutionalization (Voorpostel et al. 2015). Attrition in the SHP is somewhat higher than in other large European panel studies (Lipps 2007), but it is largely random; thus, the risk of non-response bias in the SHP is low (Voorpostel 2009).

Currently, there are 19 waves of the SHP available; however, as life satisfaction was not observed in Wave 1, our analysis uses 18 waves. We can trace the respondents up to a maximum of 17 years before or 17 years after a birth; however, no respondent is observed over the entire period before and after a birth. We estimate our models on a sample of parents defined as people who were observed in the waves that directly preceded or directly followed a birth and whose child was aged 15 years or younger. The sample also includes the observations that preceded the birth. To estimate the effect of parental age on life satisfaction, we include in the analysis a control sample. In the analysis for a first child, the control sample consists of childless people, and in the analysis for a second child, it consists of childless people and people with only one child. Finally, we excluded from the sample people younger than 18 and older than 60 years. Overall, our sample consists of 9,301 people and 45,013 observations in the analysis for a first child and 11,426 people and 56,964 observations in the analysis for a second child (for details, see Table 1).

5.2 Method

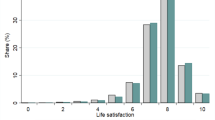

Our dependent variable is life satisfaction, which is captured with the question: “In general, how satisfied are you with your life if 0 means ‘not at all satisfied’ and 10 means ‘completely satisfied’?” The variable approximates a normal distribution, is negatively skewed, and peaks at the value of 8, which is both its overall mean and its median.

Our analysis uses a fixed-effects regression. A fixed-effects regression models the within-person variation of life satisfaction, and the between-persons time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity is controlled for by including individual fixed intercepts, which partly solves the selection issues and controls for the panel structure of the data (Allison 2009; Andreß et al. 2013). Thus, in this analysis, we explicitly focus on individual trajectories of life satisfaction.

We regress life satisfaction on the stages of parenthood represented by the age of a child and the years preceding a birth. We code the stages of parenthood as a set of dichotomous variables (thus, we estimate the so called ‘dummy impact function’, see: Brüderl and Ludwig 2015) separately for a first child and a second child. The reference category is the period three or more years before the birth. Equation 1 presents the model used in the analysis for a first child.

In Eq. 1, coefficients \(\beta _{1}\)–\(\beta _{4}\) describe the dynamics of life satisfaction in the period before a birth (B2Y—2 years before a birth, B1Y—the year preceding a birth) among men and women, coefficients \(\beta _{5}\)–\(\beta _{36}\) describe the dynamics of life satisfaction after a birth, according to the age of a child (e.g. Birth—a child is below 1 year old; A1—a child is one year old; A15—a child is fifteen years old). The interactions with parental gender allow estimating separate trajectories of life satisfaction for men and women. \({\mathbf{X}}_{\mathbf{it}}\) is a vector of control variables (other children in the household, parental age, marital status, health satisfaction, self-rated health, household income, own unemployment; for details, see Sect. 5.4) and \({\mathbf{B}}_{\mathbf{K}}\) is the vector of respective coefficients. Coefficient \(\alpha _{i}\) refers to individual fixed intercepts, and \(u_{it}\) is the residual.

5.3 Moderating Variables

In order to estimate how trajectories of life satisfaction differ among social groups, we account for moderating variables. We define all moderating variables as time-invariant. Equation 2 shows how we include them in the analysis for the first child.

As shown in Eq. 2, we interact the moderating factors (‘Mod’) with dummies coding child’s age (and the pre-birth period) and with interactions of these dummies with gender. This allows us to estimate separate trajectories of life satisfaction for men and women belonging to various socio-demographic groups (as coded by moderating factors), and test whether the differences between these trajectories are statistically significant.

We account for the following moderating factors:

- 1.

Household income: we classify respondents as having a high income if their household income per capita over the observation period is above the wave-specific average in at least half of the waves;

- 2.

Education: we assign to respondents high education if, at least once during the panel, they declared one of the following educational levels: bachelor/maturity; vocational high school with master certificate, federal certificate; technical or vocational school; vocational high school, ETS, HTL, etc.; university, academic high school, HEP, PH, HES, FH;

- 3.

Average hours of employment when the respective child was 1–4 years old (below vs. over 20 h per week and below vs. over 30 h per week);

- 4.

Time interval between a first birth and a second birth: we distinguish respondents who had their second child 1–2 years after a first birth, and those who did not have a second child in this period (i.e. they had a second child 3 or more years after a first, or they did not have a second child at all);

- 5.

Overall number of children as observed by the panel: we distinguish respondents who had 1–2 children versus respondents with 3 or more children.

5.4 Control Variables

We control for factors which correlate with both life satisfaction and the age of the child, but do not capture the mechanisms through which parenthood affects life satisfaction. In particular, it is crucial in our analysis to distinguish the effect of child’s age from the effect of parental age. Life satisfaction changes systematically with age (Blanchflower and Oswald 2008) and is clearly correlated with child’s age and stages of parenthood. Thus, we control for parental age, allowing for both the linear and quadratic effect. Moreover, as parenthood transitions may coincide with changes of marital status, we control for marital status (single, married as a reference, divorced and separated, widowed). We also mark as separate dummies the years directly before and directly after marriage and divorce, because these tend to be the periods of particularly high (in case of marriage) or particularly low (for dissolution) life satisfaction (Clark and Georgellis 2013; Clark et al. 2008). Moreover, we control for health satisfaction and self-rated health (Wilkins 2014), household income per capita (Frijters et al. 2004), and own unemployment (Winkelmann and Winkelmann 1998). Finally, we control for the presence of other children in the household (e.g. presence of children of parity 2, 3, 4 and 5 in a model for a first child): for each child we include three dummies: the year preceding a birth, the year directly following a birth, and the subsequent years. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of the variables used in the analysis.

6 Results

Figure 1 shows the trajectories of life satisfaction experienced by mothers and fathers of a first child and a second child, as estimated by a fixed-effects regression. The full table of results, including the control variables, is presented in Table 2. The following sections inspect these patterns considering our hypotheses.

Trajectories of life satisfaction during parenthood among men and women. Note: fixed-effects regression with standard errors clustered on individuals; ‘sig.’—statistical significance of the difference between the trajectories of life satisfaction: +: \(p<0.10\), *: \(p<0.05\), ***: \(p<0.01\). Full circles mark a change (compared to 3 years before the birth) significant at 95%, empty circles mark a change significant at 90%.

6.1 Stages of Parenthood

Figure 1 shows the gender and parity differences in the parental life satisfaction trajectories. A first birth is the period of elevated life satisfaction among men and women, but the change is short-lived: one to 2 years after the birth, life satisfaction returns to the pre-birth period. After a birth of a second child, fathers’ life satisfaction also temporarily increases, but mothers’ life satisfaction gradually declines and when a second child is 3–5 years old (which corresponds to the care-intense stage of parenthood) it remains lower than in the reference period. Moreover, during this care-intense stage (up to the age of 4 years), mothers’ life satisfaction declines stronger than fathers’ life satisfaction.

This pattern is consistent with Hypothesis 1c, which states that parenthood depresses life satisfaction during the care-intense stage, especially among women, due to work–family conflict. This pattern does not support Hypothesis 1b, which states that the economic costs of parenthood decrease the life satisfaction of mothers and fathers to the same extent. Our results suggest that work–family conflict shapes parental life satisfaction, and it is especially strong among mothers who have two children.

We do not find support for the hypothesis that psychological rewards and parental life satisfaction decrease after the care-intense stage of child rearing (Hypothesis 1d). In contrast, a second child’s (i.e. often the last child’s) entry into primary school seems to be a relief for mothers in Switzerland, which perhaps reflects the difficulties that result from a low coverage of childcare services during the preschool years.

Set-point theory predicts that in the long run, parenthood has no effect on life satisfaction (Hypothesis 1a). Our evidence is not fully conclusive, in part because the ‘long run’ is not clearly theoretically defined. If we assume that adaptation should occur approximately 3–5 years after a birth, we must reject the adaptation hypothesis for women who have their second child, because their life satisfaction is lower than before a second birth. However, there is a period (10–14 years after a birth) when parental life satisfaction does not differ significantly from its pre-birth levels. This holds for both men and women who have their first or second child. The estimated trajectories of life satisfaction seem to increase when a child reaches the age of 15 years; however, a definite test of the long-term consequences of parenthood requires an observation span longer than what is available in our data.

6.2 Parity and Fertility Pattern

We expected (Hypothesis 2) that parents who have more children and parents who have children more quickly one after another have a stronger ‘taste for children,’ and they experience more positive trajectories of life satisfaction than parents who have fewer children or parents who wait longer before having a second child. To test these predictions, we compared the trajectories of the life satisfaction of parents who had a second child up to 2 years after a first birth with the trajectories of parents who did not have a second birth in this period (see Fig. 2).

Trajectories of life satisfaction during parenthood: the moderating effect of the distance between the first and second births. Fixed-effects estimates. Note: for details, see Fig. 1.

The estimates show no consistent differences in the effect of having a second child. However, the effect of having a first child is more negative (at a 90% confidence level) among women who had a second child sooner than among women who waited longer or who only had a single child. This result is at odds with Hypothesis 2 and the prediction of the ‘taste for children’ theory.Footnote 1

Figure 3 compares parents who have three or more children with parents who have only one or two children. The differences are only weakly statistically significant, but the results for women generally support the prediction that parents who have fewer children derive less life satisfaction from parenthood than parents who have more children. The results for men go in the opposite direction. This suggests that having more children may indeed indicate a stronger ‘taste for children,’ which, in turn, correlates with a greater increase of life satisfaction during parenthood. This finding supports Hypothesis 2 derived from the ‘taste for children’ theory and is consistent with previous studies (Margolis and Myrskylä 2015).

Trajectories of life satisfaction during parenthood: the moderating effect of the overall number of children observed during the panel. Fixed-effects estimates. Note: for details, see Fig. 1.

6.3 Mothers and Fathers

We expected that parenthood has a more positive effect on the life satisfaction of women than on the life satisfaction of men (Hypothesis 3), because of women’s greater control over fertility behaviour. Figure 1 shows that directly after a first birth, women experience a greater peak of life satisfaction than men. However, this period of sharp gender differences is short-lived. Additionally, among parents with two children, men’s life satisfaction temporarily increases, whereas women’s life satisfaction gradually declines. These results are at odds with the predictions of the ‘taste for children’ theory.

6.4 Social Differences

Figure 4 shows that the moderating effect of education varies across genders. The differences between higher- and lower-educated men are negligible, whereas the trajectories for higher-educated women are more negative than the trajectories of lower-educated women. This is especially visible in the care-intense stage of parenthood for a first child. This finding plausibly reflects the work–family conflict experienced by higher-educated women, as postulated by Hypothesis 4a.

Trajectories of life satisfaction during parenthood: the moderating effect of education. Note: for details, see Fig. 1.

This negative effect of parenthood on the life satisfaction of educated women may be driven by their longer working hours (Hypothesis 4b). Figure 5 compares mothers who worked below and over 20 hours and below and over 30 hours weekly on average when their child was one to 4 years old. The differences are only weakly statistically significant, but they suggest that motherhood is less satisfactory among women who work longer hours when their children are young. The ‘employment penalty’ seems to be particularly consistent and long-term among the mothers of two children. This result is consistent with Hypothesis 4b, which postulates that longer employment hours contribute to work–family conflict and the lower life satisfaction of mothers.

Trajectories of life satisfaction during parenthood: the moderating effect of working at least 20 h per week and 30 h per week (on average) when the child was 1–4 years old. Note: for details, see Fig. 1.

We also expected that people with higher incomes experience more positive changes of life satisfaction during parenthood than people with lower incomes, because higher incomes help them deal with the economic costs of parenthood (Hypothesis 5). Figure 6 compares people with an above-average household income per capita and people with a below-average income. The differences are not very strong, but they suggest that mothers in wealthier households experience parenthood more positively than women in poorer households.

Trajectories of life satisfaction during parenthood: the moderating effect of household income per capita. Note: for details, see Fig. 1.

7 Additional Analyses

7.1 Sex of a Child

Sex of a child is a potentially interesting moderator of the relationship between parenthood and life satisfaction that might contribute to the discussion on the ‘taste for children’ theory. Unfortunately, the SHP does not provide information on parental preferences regarding children’s sex, which precludes a direct test. However, general theories suggest that parents prefer a child of the same gender as theirs (homophily hypothesis), and—in case of two or more children—parents typically prefer mixed composition of children over same-sex children (so called ‘separate spheres’ belief). We run an additional analysis to test whether gender of children moderates the life satisfaction consequences of parenthood (see Fig. 7 in On-line Appendix): we compared the effect of having a daughter and a son as a 1st child, and we compared parents having two children of mixed gender with those having two children of the same gender. The results showed that the differences between the trajectories of life satisfaction of these groups are negligible and not statistical significant.

7.2 Welfare Support

Welfare support, including measures, such as financial allowances for families with children or access to formal childcare, might improve parental life satisfaction by reducing economic costs of parenthood and family work conflict. The SHP includes information on welfare transfers (i.e. whether the respondent receives child/family allowance) and the use of formal childcare.

A comparison of life satisfaction trajectories of parents who ever used formal childcare when their child was 4 years old or younger and those who never used childcare at that stage showed that life satisfaction of women who used formal childcare declined stronger than life satisfaction of mothers who never used childcare (see Fig. 8 in On-line Appendix). This pattern suggests that what we observe is not the (potentially beneficial) effect of childcare on life satisfaction but rather the (potentially negative) effect of the need for childcare on parental life satisfaction. In fact, use of childcare reflects the parental need for childcare, which typically is driven by mothers’ employment. Families who use childcare, and who might for this reason experience lower work–family conflict, in fact experience considerable work–family conflict, with negative spillovers for their life satisfaction.

Estimating the effect of child allowance proved difficult for another reason. Switzerland offers universal family allowance for both employed and inactive people (with some additional conditions): parents of children up to 16 years old and of children aged 16–25 in education receive a monthly allowance for each child. The universal character of the allowance is an obstacle for estimating its effect: only about 15% (depending on child’s age) of families have never received an allowance, and this group is too small to provide reliable, stable estimates.

7.3 Unplanned Versus Planned Pregnancies

The SHP includes a question on fertility intentions for the 24 months following the interview. In our sample, 67% of first children and 81% of second children were planned. We used this information to compare life satisfaction of parents who intended to have a child about 1–2 year before its birth (two waves before the birth has been recorded) with those who did not intend to have a child. The results are unstable and difficult to interpret because of the small size of the group who did not plan the pregnancy.

8 Robustness Checks

Our study design, in particular the inclusion of control sample in the analysis, attempts to estimate how life satisfaction trajectories of parents differ from the (hypothetical and unobserved) life satisfaction trajectories of the same people in the event of remaining childless (or having only a single child in the analysis for two children). In other words, we assume that the control sample does not differ substantially from parents in the reference period, primarily because we expect no anticipation effect during the reference period (Baetschmann et al. 2016, p. 246 documented modest anticipation effects already 5 years before first birth, but most studies detected anticipation effects 1–2 years before birth only). We checked the validity of our assumption by estimating the models with a reference period of 6 or more years before the birth. The results do not change substantially.

9 Discussion

This study investigated changes of life satisfaction upon a transition to parenthood and over its course, accounting for first and second births and ageing of children. It attempted to provide empirical evidence from a new social context, Switzerland, and to systematically test predictions derived from theories conceptualizing the link between parenthood and happiness.

For a first child, our analysis showed a pattern similar to the one observed by previous studies (primarily in: Myrskylä and Margolis 2014; Baetschmann et al. 2016). Parents’ life satisfaction increased in the year preceding a first birth, peaked directly after the birth, and declined afterwards; the changes were more pronounced among mothers than among fathers. The effect size of the peak at first birth (0.45 on a scale from 0 to 10 [i.e. 4.5%] among women and 0.17 [1.7%] among men) is comparable to those estimated in other social contexts: among women 5.5% in the UK (Myrskylä and Margolis 2014), 3.6% in Germany (Myrskylä and Margolis 2014), and 3% in Russia (Mikucka 2016); among men 2% in Russia and about 3% in Germany and the UK.

However, the trajectories estimated for a second child differed from those estimated by other studies, as they showed a statistically significant decline of maternal life satisfaction between the ages of 1 and 4 of a second child. In Switzerland, majority of parents decide to have two children, and therefore, this result applies to majority of them. This negative effect of parenthood on life satisfaction is an exception among longitudinal studies which demonstrated primarily positive, although short-lived, effects. This suggests that the “parenthood paradox” (i.e. the fact that people have second children although this experience lowers their life satisfaction) is stronger in Switzerland than in other countries. Although having a two-child family may be a source of meaning (Baumeister 1991) and psychological rewards, this goal seems to be in conflict with other goals, plausibly career and leisure.

This result also suggests that the low level of state support for families that characterizes the Swiss context indeed worsens the motherhood experience especially for a second child. This is consistent with previous studies showing that external resources improve parenthood experience at higher parities, but not so much for parents having a first child (Mikucka and Rizzi 2016). In particular, the result may reflect Switzerland’s low coverage of formal childcare during the intense stage of parenthood. The short parental leave and the absence of leaves for fathers are another weakness of the Swiss family policy that could explain the decline of women’s satisfaction during the preschool period. Other results of our study may point to the financial accessibility of formal childcare, such as the higher satisfaction of fathers having their first child when they have a higher income. Moreover, we showed that fathers with one child are more than half point happier than fathers with three children or more. This result might be related to financial difficulties faced by larger families in Switzerland. Overall, our results echo those of a recent study showing a mismatch between family policies and public attitudes in Switzerland. According to Valarino et al. (2017), about half of the respondents state that paid leave should be longer than the present 4 months leave, and about 80% think the father should take at least some leave or that leave should be equally shared between partners. In conclusion, grandparenting and women’s part-time job, which represent the main strategies of families in Switzerland, may not be perceived as satisfactory to balance work and family. Development of accessible childcare services, more generous transfers for large families, extension of the paid leave, and an equal share of the leave between partners should be a priority in the agenda of policy makers. This is of paramount importance to adapt further the Swiss welfare system to the changing role of women in the labour market and to the new involvement of fathers in the family.

Apart from providing new empirical evidence, our study systematically tested predictions of theoretical models linking parenthood and life satisfaction. We verified hypotheses derived from set-point theory, economic model of parenthood, the approach stressing work–family conflict, psychological rewards from parenthood, and the approach emphasizing the ‘taste for children.’

Our results are most consistent with the approach postulating that work–family conflict shapes parental life satisfaction. The theory implies that parental life satisfaction should decrease during the care-intense stages of parenthood especially among women (H1c) and that the effect of parenthood should be during this stage more negative among higher-educated women than among lower educated women (H4). Indeed, mothers having a second child who is 1–4 years old were less satisfied with their lives than they had been before a second child was born, and life satisfaction among higher-educated mothers having a first child declined more during the care-intense stage with a first child than among lower educated mothers.

Our results were also partly consistent with the approach emphasizing the role of economic costs for life satisfaction of parents. We expected that people with higher incomes derived more life satisfaction from parenthood than those with lower incomes (H5). In our analysis, among men having a first child aged 2 and 7, fathers with higher incomes had more positive trajectories of life satisfaction than fathers with lower incomes. Observing a moderating effect of income among men but not among women is not surprising in a relatively gender-traditional society, where the responsibility for economic well-being of a household rests predominantly on men. However, overall these results do not support previous conclusions that economic factors are the main force reducing parental life satisfaction (e.g. Stanca 2012).

The results of our study provided some support to the set-point theory. Such a test is complicated by the fact that the ‘long run’ is not clearly theoretically defined. Our results indeed showed a period (when a child is 13–14 years old) when parental life satisfaction consistently did not differ from the life satisfaction before birth. However, after the child’s age of 14, the trajectories of life satisfaction were increasing (among men and women, having a first child and a second child). This suggests that the period when parenthood has no effect on life satisfaction may be just a transitory stage, after which parenthood improves parental life satisfaction. This needs to be verified by future studies.

We found no support for the approach emphasizing the psychological rewards from early parenthood. The care-intense stage of parenthood seems the most difficult period, and it affects women more negatively than men; instead, the theory postulated that it should be the most rewarding. Even if the psychological rewards from parenthood are indeed highest during the care-intense stage of parenthood, it seems that they do not counterbalance the strains and challenges characterizing this stage, and the net effect on life satisfaction remains negative.

Similarly, we did not find much support for the approach stressing ‘taste for children’ as the major force shaping parental life satisfaction. Although women plausibly have greater control over the fertility than men do, women’s life satisfaction increases more than men’s only during the short period surrounding the first birth. We also expected that parents having more children and parents having children quickly one after another derive more life satisfaction from parenthood. We found that parents having three or more children had more negative trajectories of life satisfaction than parents with only one or two children. On top of that, women who waited longer than 2 years before having their second child experienced more positive trajectories of life satisfaction during parenthood than women who had their second child within 2 years after a first birth. These results question whether the ‘taste for children’ is indeed revealed through fertility behaviour, and it suggests that these decisions are guided by social norms rather than by personal preferences. This applies not only to fertility decisions. Also, higher-educated parents had overall more positive trajectories of life satisfaction than lower educated parents, although pursuing higher education delays parenthood and suggests lower importance of parenthood among life goals.

The limitations of our study are similar to those present in other studies on fertility and life satisfaction. First, the fixed-effects regressions control for the time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity between individuals but not for the time-varying one. In particular, if parents are a select group and have specific unobserved (e.g. psychological) characteristics, then their age trajectories of life satisfaction may systematically differ from life satisfaction age trajectories of childless people. Second, the chosen methodological framework and the estimation of separate trajectories for various subgroups limits our possibility to account for several moderating factors in a single estimation. This opens the floor for speculations which are not always easy to resolve, for example to which extent are the differences between educational groups driven by household income. Third, important segments of population, such as people not residing with their children (e.g. after a divorce), step parents, or adoptive parents are not included in the analysis. Arguably these groups have their own limitations and specificity and our results should not be extended to these other groups.

Despite these shortcomings, our study contributes to the field by providing empirical evidence for a previously unstudied social context, and offers a systematic test of major theories. We come up with two take-home messages. First, the Switzerland is a case where we observe ‘parenthood paradox:’ the most common fertility pattern, i.e. two children relatively closely spaced, is the pattern correlating with a decline of parental life satisfaction, especially among women. This and the poor performance of hypotheses derived from ‘taste for children’ theory suggest that when it comes to fertility, people often choose paths which do not immediately make them happier. In other words, fertility behaviour seems to be guided by norms and values, and to a lesser degree by a calculation of immediate costs and benefits. Second, as predicted by the set-point theory, there exists a time span when parental life satisfaction returns to the pre-birth level. This happens when a child is about 13–14 years old. However, our estimates suggest that this null effect may be just a transitory stage, and parental life satisfaction may further increase when children become older. This and others issues unresolved by this study are a promising area for future studies.

Notes

It is possible that this difference in trajectories is driven by unintended pregnancies among women who have a second child sooner, but our data do not allow us to test this hypothesis.

References

Aassve, A., Goisis, A., & Sironi, M. (2012). Happiness and childbearing across Europe. Social Indicators Research, 108(1), 65–86.

Allison, P. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. In: Quantitative applications in the social sciences. SAGE Publications.

Andreß, H. J., Golsch, K., & Schmidt, A. W. (2013). Applied panel data analysis for economic and social surveys. Berlin: Springer.

Angeles, L. (2010). Children and life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 523–538.

Anusic, I., Yap, S. C., & Lucas, R. E. (2014). Testing set-point theory in a Swiss national sample: Reaction and adaptation to major life events. Social Indicators Research, 119(3), 1265–1288.

Baetschmann, G., Staub, K. E., & Studer, R. (2016). Does the stork deliver happiness? Parenthood and life satisfaction. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 130, 242–260.

Baranowska, A., & Matysiak, A. (2011). Does parenthood increase happiness? Evidence for Poland. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 9, 307–325.

Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Meanings of life. New York: Guilford Press.

Becker, G. S. (1991). A treatise on the family (enlarged ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Billari, F. C. (2009). The happiness commonality: Fertility decisions in low-fertility settings. In How generations and gender shape demographic change. Towards policies based on better knowledge, GGP conference proceedings (pp. 7–31). New York and Geneva: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science and Medicine, 66(8), 1733–1749.

Brüderl, J., & Ludwig, V. (2015). Fixed-effects panel regression. In H. Best & C. Wolf (Eds.), The sage handbook of regression analysis and causal inference (pp. 327–357). London: Sage.

Burkimsher, M., & Zeman, K. (2017). Childlessness in Switzerland and Austria. In M. Kreyenfeld & D. Konietzka (Eds.), Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, causes, and consequences, demographic research monographs (A series of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research). Cham: Springer.

Clark, A. E., Diener, E., Georgellis, Y., & Lucas, R. E. (2008). Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis. The Economic Journal, 118(529), F222–F243.

Clark, A. E., & Georgellis, Y. (2013). Back to baseline in Britain: Adaptation in the British Household Panel Survey. Economica, 80(319), 496–512.

Currie, J., & Eveline, J. (2011). E-technology and work/life balance for academics with young children. Higher Education, 62(4), 533–550.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2004). Money does matter! Evidence from increasing real income and life satisfaction in East Germany following reunification. American Economic Review, 94, 730–740.

Frijters, P., Johnston, D. W., & Shields, M. A. (2011). Life satisfaction dynamics with quarterly life event data. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 113(1), 190–211.

Gatrell, C. J., Burnett, S. B., Cooper, C. L., & Sparrow, P. (2013). Work-life balance and parenthood: A comparative review of definitions, equity and enrichment. International Journal of management reviews, 15(3), 300–316.

Greenhaus, J. H., Collins, K. M., & Shaw, J. D. (2003). The relation between work–family balance and quality of life. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 510–531.

Hansen, T. (2012). Parenthood and happiness: A review of folk theories versus empirical evidence. Social Indicators Research, 108(1), 29–64.

Headey, B., & Wearing, A. (1989). Personality, life events, and subjective well-being: Toward a dynamic equilibrium model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(4), 731.

Kohler, H.-P., Behrman, J. R., & Skytthe, A. (2005). Partner + children = happiness? The effects of partnerships and fertility on well-being. Population and Development Review, 31(3), 407–445.

Kravdal, Ø. (2014). The estimation of fertility effects on happiness: Even more difficult than usually acknowledged. European Journal of Population/Revue Européenne de Démographie, 30(3), 263–290.

Le Goff, J.-M., Barbeiro, A., & Gossweiler, E. (2011). La garde des enfants par leurs grands-parents, créatrice de liens intergénérationnels. L’exemple de la Suisse romande. Revue des Politiques Sociales et Familiales, 105(105), 17–30.

Levy, R., Gauthier, J.-A., Widmer, E., et al. (2006). Entre contraintes institutionnelle et domestique: les parcours de vie masculins et féminins en Suisse. The Canadian Journal of Sociology, 31(4), 461–489.

Lipps, O. (2007). Attrition in the Swiss Household Panel. Methoden, Daten, Analysen, 1(1), 45–68.

Margolis, R., & Myrskylä, M. (2011). A global perspective on happiness and fertility. Population and Development Review, 37(1), 29–56.

Margolis, R., & Myrskylä, M. (2015). Parental well-being surrounding first birth as a determinant of further parity progression. Demography, 52(4), 1147–1166.

Mikucka, M. (2016). How does parenthood affect life satisfaction in Russia? Advances in Life Course Research, 30, 16–29.

Mikucka, M., & Rizzi, E. (2016). Does it take a village to raise a child? The buffering effect of relationships with relatives for parental life satisfaction. Demographic Research, 34, 943–994.

Myrskylä, M., & Margolis, R. (2014). Happiness: Before and after the kids. Demography, 51(5), 1843–1866.

Nomaguchi, K. M. (2012). Parenthood and psychological well-being: Clarifying the role of child age and parent-child relationship quality. Social Science Research, 41(2), 489–498.

OECD. (2015). Family database. Paris: Electronic Database.

Parr, N. (2010). Satisfaction with life as an antecedent of fertility: Partner + happiness = children. Demographic Research, 22(21), 635–661.

Pollmann-Schult, M. (2014). Parenthood and life satisfaction: Why don’t children make people happy? Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 319–336.

Roeters, A., Mandemakers, J. J., & Voorpostel, M. (2016). Parenthood and well-being: The moderating role of leisure and paid work. European Journal of Population, 32(3), 381–401.

Stanca, L. (2012). Suffer the little children: Measuring the effects of parenthood on well-being worldwide. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 81, 742–750.

Tanturri, M. L., Donno, A., Faludi, C., Miettinen, A., Rotkirch, A., & Szalma, I. (2016). Micro-determinants of childlessness in Europe: A cross-gender and cross-country study. In: Conference paper, paper presented at European population conference, Mainz. August, 31–September, 3.

Tillmann, R., Voorpostel, M., Kuhn, U., Lebert, F., Ryser, V.-A., Lipps, O., et al. (2016). The Swiss household panel study: Observing social change since 1999. Longitudinal and Lifecourse Studies: International Journal, 7(1), 64–78.

Valarino, I., Duvander, A.-Z., Haas, L., & Neyer, G. (2017). Exploring leave policy preferences: A comparison of Austria, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society, 25(1), 118–147.

Vono de Vilhena, D., & Matthiesen, S. (2014). Who is doing it again: Varying association between education and second births in Europe. In: Comparative analysis based on the EU-SILC data. Families and societies–digest 11, Population Europe, Berlin.

Voorpostel, M. (2009). Attrition in the Swiss Household Panel by demographic characteristics and levels of social involvement. In: Working papers serie 1–09. Lausanne: FORS.

Voorpostel, M., Tillmann, R., Lebert, F., Kuhn, U., Lipps, O., Ryser, V.-A., et al. (2015). Swiss Household Panel user guide (1999–2014). Wave 16. Lausanne: FORS.

Widmer, E. D., & Ritschard, G. (2009). The de-standardization of the life course: Are men and women equal? Advances in Life Course Research, 14(1), 28–39.

Wilkins, R. (2014). Life satisfaction, health and wellbeing. Families, Incomes and Jobs, 9, 66.

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (1998). Why are the unemployed so unhappy? Evidence from panel data. Economica, 65(257), 1–15.

Funding

Funding was provided by Belgian French-speaking Community (BE) (Grant No. subvention 15/19-063).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: References to the special issue entitled “The Parenthood Happiness Puzzle”, published in 2016, have been added.

Ester Rizzi and Małgorzata Mikucka were supported by the ARC grant funded by the Belgian French-speaking Community within the project Family transformations - Incentives and Norms (subvention: 15/19–063). This study has been realized using the data collected by the Swiss Household Panel (SHP), which is based at the Swiss Centre of Expertise in the Social Sciences FORS. The project is financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation. We thank our colleagues of the Centre for Demographic research in Louvain-la-Neuve who participate to the internal seminar “Midi de la recherché”, Marieke Voorpostel and two anonymous reviewers of the FORS Working papers series for their useful comments.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mikucka, M., Rizzi, E. The Parenthood and Happiness Link: Testing Predictions from Five Theories. Eur J Population 36, 337–361 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-019-09532-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-019-09532-1