Abstract

Reporting on the results of a sequential mixed-methods study conducted in the Iranian higher education context, this paper addressed measures and features of teacher effectiveness evaluation from EFL lecturers’ perspectives. In so doing, two groups of lecturers were recruited to participate in quantitative (n = 43) and qualitative (n = 14) phases of the research. The findings obtained from a researcher-developed questionnaire and semi-structured interviews were threefold. First, five independent evaluation measures (SETs/students’ ratings, student learning outcomes, peer evaluation, self-evaluation, and observation) were introduced. Second, features of a successful teacher evaluation system were discussed. Third, evidence for a differentiated teacher appraisal model was presented. The model discussed called for L2-specific features in L2 teacher effectiveness evaluation. The findings were imbued with several implications for the main stakeholders, e.g. administrators and teachers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Whereas research on teacher effectiveness seemed to be of fitful progress in the first half of the twentieth century (e.g., Ryans 1949), the issue started to draw more attention in the second half of the century (e.g., Doyle 1977). The trend, in particular, has come to its own and become more systematic by the outset of the third millennium (Darling-Hammond et al. 2005; Kane et al. 2008). More recently, research continued to gather momentum (e.g., Darling-Hammond et al. 2013; Muijs et al. 2014; Stronge et al. 2011). All in all, what we know about teacher effectiveness research (TER) is theoretically and conceptually based on research from the 1970s onwards (Mazandarani and Troudi 2017), inasmuch as the history of research on teacher evaluation is rather speculative prior to 1970 (Shinkfield and Stufflebeam 1996). The theoretical advancement has led to the emergence of different frameworks, models, and schemes for teacher evaluation (Campbell et al. 2003; Cheng and Tsui 1999; McBer 2000), the mainstay of which has always been the very issue of quality teaching.

Despite its long history, TER has been shown to be limited from different perspectives. First, much of what we know today about teacher effectiveness is heavily driven by research studies in Western contexts, thereby constraining our understanding in non-Western contexts. As Campbell et al. (2004b) contend, much of the research conducted on educational effectiveness has been in the USA, the Netherlands, and the UK. This simply shows that TER could yet be in a state of flux in other contexts, including the Middle-Eastern one, and more notably in the Iranian EFL (English as a Foreign Language) context in which few studies have been conducted on TER (e.g., Ostovar Namaghi 2010). Second, teacher education research in higher education, as compared to primary and secondary education, has been far less investigated (Mazandarani 2020). A quick search of academic databases using “teacher” and “lecturer” effectiveness/evaluation simply corroborates the idea, despite the fact that the two terms have been used interchangeably in the literature. It is worth highlighting that in this study, unless otherwise specified, the authors have used both terms to refer to higher education context. Third, the growing body of the literature on teacher effectiveness has evolved from mainstream or general education (e.g., Kupermintz 2003). Indeed, the literature on EFL contexts (e.g., Coombe et al. 2007) is inextricably sparse. Fourth, much of TER revolves mainly around limited sources of data, i.e. students learning outcomes (Campbell et al. 2004b; Tucker and Stronge 2005), student ratings or evaluations of teaching effectiveness (Marsh 2007) as the indicators of teacher effectiveness, and based on a single administrator’s observations which, as Wilkerson et al. (2000, p. 179) contend, characterises traditional mode of teacher evaluation. To some, teacher evaluation is simply classroom observation (Danielson and McGreal 2000, p. 47). Yet, as the literature suggests, multiple measurements and source of data should be included in the process of teacher evaluation (Looney 2011, p. 449). Fifth, a cursory glance over the literature on TER yields equivocal results, probably due to methodological inconsistencies including design, sampling, levels of analysis, etc., which can potentially bring forth a false conception of teacher effectiveness.

Such concerns testify to the multidimensionality of teacher effectiveness, necessitating the need for the so-called differentiated models for teacher effectiveness (Campbell et al. 2003; Kyriakides 2007). To date, there has been little robust research which has taken into account all the above-raised dimensions particularly in EFL contexts. It is, therefore, appropriate to conclude that much of what is known about teacher effectiveness is more of one-size-fits-all nature. Given such concerns, this paper is an attempt to bring to the fore Iranian EFL teachers’ perceptions and attitudes towards teacher effectiveness evaluation exploring teachers’ wants, likes, dislikes, and ideals as to effective language teaching. Reporting on part of a research project (Mazandarani 2014), this paper made an endeavour to inquire into teachers’ understanding of the “measures” and “features” of teacher effectiveness evaluation. In so doing, the following research questions were formulated:

-

What are Iranian EFL lecturers’ perceptions of measures of teacher effectiveness evaluation?

-

What are Iranian EFL lecturers’ perceptions of features of a teacher effectiveness evaluation system?

2 Review of literature

2.1 Teacher effectiveness research

TER has always been entwined with features of an effective teacher. Adopting a critical stance, Arthur et al. (2003, p. 235) made their well-posed question of “effective in terms of what?”. As such, the notion of teacher effectiveness then appears to be rather enigmatic, given that different stakeholders, i.e., policymakers, administrators, teachers, students, etc., may hold different, if not contradictory, views on effective teaching. Such concerns have led researchers to constantly struggle with their quest for identifying the “best” characteristics needed for effective teaching. The emergence of several national and international organisations such as The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) along with its various surveys and assessment tools including Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) and The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) convey a clear message, i.e. the importance of “quality” teaching in education.

Effective teaching can surely facilitate effective learning and maximise the overall quality of (higher) education. Despite its straightforwardness in mainstream education contexts, the literature suggests that as for TER, it is back to square one, especially in EFL contexts. This supports Campbell et al.’s (2003, p. 354) notion of “differential effectiveness across different subjects in the curriculum, or across different components”. The next issue resting at the heart of TER is the standards or criteria against which teachers can be evaluated. Indeed, there have been some controversies over the operationalised definition of the widely accepted criteria for teacher evaluation. For instance, despite its relatively rich literature, as Spooren et al. (2013) argue, the validity of student evaluation of teachers is a point of contention among researchers. As the literature suggests, such ratings could be associated with other factors such as “grading leniency” (Griffin 2004) and hence need to be interpreted with caution.

Teachers need to be well aware of the objectives, goals, as well as other stakeholders’ expectations to which they are deemed to live up to. Otherwise, whatever attempts teachers undertake may eventually turn out to be futile. Raising teachers’ awareness of clear and transparent measures of evaluation, therefore, seems to be the very first step in the right direction. Such a transparent system can win the teachers’ “buy-in” (Goe et al. 2012, p. 22). Another concern as to TER relates to the old yet contentious adage of “good teachers are born, not made”. According to Harmer (2007, p. 23), some people possess a natural affinity for teaching. Nevertheless, as he continues, there is a possibility for those who lack such a natural endowment to become effective teachers. Therefore, educational systems and in particular pre-service and in-service teacher development programmes and teacher certification tend to be highly influential in shaping teachers’ professional lives. This area, i.e., ex ante qualification (certification) versus ex post measurement as an indicator of teacher effectiveness, per se is imbued with various tensions in the literature. Whereas advocates of teacher certification believe that teacher effectiveness is contingent on teacher certification and the quality of preparation teachers receive (Darling-Hammond et al. 2005), others tend to adopt a more cautious stance to the relationship between teacher effectiveness and teacher certification (e.g., Kane et al. 2008). Finally, what deserves to be more heeded is the perplexing concept of “effectiveness” which has been characterised as “doing the right thing” and with this in view is more important than “efficiency” which has been translated into “doing the things right” (Januszewski and Molenda 2008, p. 60). As to the clichéd dichotomy between teaching as science and/or art (Harmer 2007), one may consider effective teaching as a science and efficient teaching as an art. Consequently, arriving at a working definition of effectiveness and recognising its connotations in teacher evaluation is prerequisite for TER. It is, hence, apparent that further research is needed to throw light upon the hidden dimensions of TER, albeit the commendable advancements in the past few decades.

2.2 Teacher evaluation models, frameworks, and schemes

Perhaps, at the heart of research on various educational topics is one single concept, i.e. “quality” and “excellence”; and teacher evaluation is no exception. The relevant literature reveals that whereas some educational systems (mostly Western) have developed their own national teacher appraisal systems, other countries tend to avail themselves of appraisal schemes which have mostly been borrowed or copied from other countries. Given the social, political, cultural and economic attachments of teacher evaluation systems, by no means can it be logical to extrapolate a working appraisal system from one context to another context with different socio-cultural features, e.g. from Western to the Middle-Eastern one, unless the above-raised features are localised and customised.

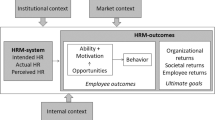

To date, there exist only a few laudable models and frameworks appertaining to teacher evaluation and teacher effectiveness targeting higher education. Much of the current literature on TER models and frameworks has evolved since 2000 onwards. Amongst others, the Hay McBer model of teacher effectiveness (McBer 2000), which introduces “professional characteristics”, “teaching skills”, and “classroom climate” as measures of teacher effectiveness (p. 6), Campbell et al.’s conception of differentiated model (Campbell et al. 2003, 2004a), discussing five domains of difference between their proposed differential model and those of others. Cheng and Tsui’s multimodels of teacher effectiveness which is a combination of seven models of teacher effectiveness (Cheng and Tsui 1999), and Goe, Bell, and Little’s research synthesis (2008), which provides an overview of different approaches towards teacher effectiveness measurement, thereby proposing a comprehensive definition of constituents of teacher effectiveness, are amongst the highly cited research studies pertinent to teacher effectiveness. Despite all their merits, a quick review of the literature reveals that such models have rarely been adopted in other contexts, i.e. EFL contexts, given that the success of such models, as stated earlier, is contingent upon several contextual (e.g., socio-economic and socio-cultural) factors.

2.3 Teacher evaluation in EFL/ESL context

The literature on TER is replete with studies focused on teacher evaluation in mainstream primary education contexts which serves as an overarching domain for language education. Notably, TER in EFL/ESL higher education contexts is sparse, and as such, it tends to be rather alienated from the idiosyncratic features of teaching in a context in which the medium of instruction is different from students’ mother tongue. Indeed, the literature shows that TER has not been well apportioned across different educational contexts, i.e. mainstream versus L2 educational contexts. It is, therefore, not hyperbolic to state that TER has come to its own through mainstream primary education with little appreciation of challenges of teaching in higher education L2 context. While some researchers view language teacher education as a microcosm of teacher education sharing a lot both in theory and practice (e.g., Crandall 2000, p. 34), others adopt a rather skeptical stance questioning the extent to which findings in mainstream education tend to applicable to that of L2. It is worth highlighting that the literature on teacher education and teacher development in L2 context is rather robust (Borg 2006; Crandall 2000; Johnson 2009). Nevertheless, teacher evaluation in L2 contexts and especially in the Middle-Eastern contexts has seemingly been left out, albeit few published works (e.g., Coombe et al. 2007). Although these very few attempts could hold a promise, they have been rather marginalised as they failed to take into account the multifaceted nature of teacher evaluation.

3 Method

3.1 Context and participants

A non-probability convenience sampling strategy was used which according to Dörnyei and Taguchi (2010, p. 61) is “the most common non-probability sampling type in L2 research”. The sampling was also purposive, in that the participants were selected “based on specific purposes” (Teddlie and Yu 2007, p. 77). The participants were deliberately selected based on the assumption that they all shared particular characteristics required for inclusion in the study, thereby enabling the researchers for deep exploration of “central themes and puzzles” (Ritchie et al. 2003, p. 78). To this end, a set of selection criteria was put forward including participants’ affiliation, level of qualification, academic major, employment status, and gender. In order to maximise the “transferability” (Teddlie and Yu 2007, p. 78) of the findings, lecturers holding different educational degrees within the realm of English Language Teaching (ELT), including Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL), English Language Translation Studies, English Linguistics, and English Language Literature who were affiliated to different universities and higher education institutions were purposively selected. As to the lecturers’ academic qualifications, they were of three categories, i.e. MA holders, PhD candidate, and PhD holders. A total of 43 lecturers who met the selection criteria, took part in the first phase of the study. Demographics of the participants in the quantitative phase of the study are presented in Table 1.

In a similar fashion, a purposive and criterion-based sample of lecturers were requested to take part in the second phase of the study, i.e. interview. A total of 14 participants who met the selection criteria, the details of whom are shown in Table 2, were invited to participate in the interviews.

3.2 Instruments

3.2.1 Questionnaire

In order to increase the validity and credibility of the results, multiple approaches to data collection were adopted. In particular, a researcher-developed Likert scale questionnaire was developed to measure the lecturers’ perceptions of teacher evaluation. The questionnaire comprised 63 closed-ended statements, six open-ended questions, and a section on the respondents’ demographics. The questionnaire was developed to collect both factual and attitudinal data (Dörnyei and Taguchi 2010). An attempt was made to inform the statements based on the reviewed literature and the pertinent gap, confirmed by two topic experts in the field who earned their PhD in TESOL and education. The open-ended section was also developed thematically to mirror the close-ended section of the questionnaire. The main constructs of the questionnaire included general perceptions towards TE, measure of TE evaluation, ways to improve TE, and critical teacher appraisal model. Both deductive and inductive approaches were combined to design the questionnaire, forming an initial item pool of 98 items. After expert review, the instrument was subjected to a pilot study on 15 lecturers, the results of which helped improve the validity and reliability of the instrument. Every attempt was made to select lecturers with similar features and characteristics relevant to the study. In particular, the pilot test helped with the problematic wordings, lay-out, and instruction (Oppenheim 1992). The final version of the questionnaire included 63 items scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.

3.2.2 Interview

To uncover lecturers’ perceptions towards teacher evaluation, semi-structured interviews, the most common type of interview in applied linguistics research (Dörnyei 2007), were conducted. In so doing, an interview guide structuring the course of interview (Kvale and Brinkmann 2009, p. 130), was developed. The interview protocol comprised three sections, namely warm-up questions, main questions which were “thematically” and “dynamically” (Kvale and Brinkmann 2009) related to research questions, and some probing and closing questions. The introductory section of the interview guide included questions related to the participants’ careers and interests. The major content questions were formulated to cover the following main themes: general perceptions of teacher effectiveness, measures of evaluation, a set of criteria (standards) for teacher effectiveness, ways to improve teacher effectiveness, perceptions of the existing appraisal model in Iran, multidimensionality of teacher effectiveness, and critical teacher appraisal. The closing section of the interview included questions which were specifically designed to provide the interviewees with an opportunity to freely express their opinions with a particular focus on the areas which had escaped the researcher’s attention and had not been discussed in the interviews. All the interviewees were informed of the aims of the study and were ensured of confidentiality and privacy. Twelve out of fourteen interviews were conducted one-on-one with each participants and another two were conducted online. The follow-up face-to-face interviews helped “convey a picture of the reality of people’s lives” (Gillham 2008, p. 100). Both instruments, i.e. questionnaire and interview protocol were thematically developed on similar themes, thereby allowing to probe into similarities and differences between the data collected from the two datasets.

3.3 Procedure

A sequential mixed methods design was adopted in order to collect both quantitative and qualitative data, in which, as Hesse-Biber (2010) argues, quantitative data (quan) is in the service of the qualitative data (QUAL). Being more exploratory in nature, the present study was aimed at delving into the participants’ perceptions of and attitudes towards teacher effectiveness evaluation. The choice of a sequential mixed methods design was informed by a number of procedural reasons and practical consideration (Creswell 2014). Drawing on “pragmatism”, mixed methods design provided the researchers with the chance to “bring out the best of both paradigms”, “multi-level analysis” of complex phenomena, and hence “improved validity” through corroborating quantitative and qualitative data (Dörnyei 2007, p. 45). Indeed, the methodological novelty of this study, compared to the existing body of literature, is collecting both quantitative and qualitative data. Such a combination allowed us not only to drill down into participants’ perceptions towards the statements of the questionnaire, but also to explore their lived experiences and insights into the areas which have been left out or found to be critical in the questionnaire during the qualitative phase of data collection. Having collected and analysed both types of raw data, the findings were then merged to arrive at a deeper understanding of the phenomenon. As to the ethical considerations, the participants’ informed consent was obtained and every attempt was made to ensure their anonymity, privacy, and confidentiality. The researchers remained vigilant throughout the conduct of the study about the “costs/benefits ratio” (Cohen et al. 2011, p. 75).

3.4 Data analysis

The quantitative analysis of the questionnaire was conducted using SPSS, whereas the thematic analysis of the interview quotations, reported and transcribed verbatim, was done using NVIVO which allows for management of large qualitative datasets. Descriptive statistics including frequency and percentage were used to analyse quantitative data in SPSS. The analysis of qualitative data involved organising, transcribing, exploring, coding, reporting, and interpreting the data (Creswell 2012, pp. 261–262). As such, informed by an iterative approach (Bryman 2012), the coding process involved reading and dividing the interview transcripts into several segments, labelling the segments by attaching keywords, condensing the data, reducing the generated codes, and finally collapsing the generated codes into themes (Brinkmann and Kvale 2018, p. 121; Creswell 2015, p. 243). Several features including memos, annotations, and descriptions were used to better make sense of the generated themes, categories and subcategories.

4 Findings

This section presents the findings drawn from two data sources in two categories, i.e. measures of teacher evaluation, and features of evaluation system. It is worth highlighting that the emergence of the ideas and categories is of different patterns. That is, whereas some themes and categories were supported by both datasets (questionnaire and interview), some other received support from only one dataset (interview or questionnaire).

4.1 Measures of teacher evaluation

The merging of themes and categories obtained from the two datasets culminated in the emergence of five major measures of evaluation summarised in Table 3, as follows.

4.1.1 Student evaluations of teachers (SETs)/student ratings

As an easy measure, students' evaluations of teachers are indeed students’ opinions or ratings germane to their teachers’ capabilities (Hornstein 2017). The statistical analysis of the quantitative data showed that 79% of the respondent lecturers considered students’ voices as one of the criteria for teacher appraisal (Item 1: “Different stakeholders’ voices e.g. teachers, students, administrators, etc. who have a stake in teaching, should be heard and incorporated into the appraisal model.”). The thematic analysis of the qualitative data supported these results. For instance, Parham, an interviewee, had a quite positive stance towards SETs and stated:

At university level, especially EFL, teaching English to foreign language students, I think the students can be a good source of feedback but not the only one … just provided that they are instructed how to evaluate their teachers.

Although the findings were generally in favour of student ratings, some participants had their own reservation. For instance, Niloofar, one of the interviewees, touched upon the demerits inherent in SETs (e.g., grading bias) and stated:

… the one I remember was that the students are asked without any preparation to answer some questions and evaluate the instructor while the instructor was present in the class; the problem was that if the evaluation was before the mid exam, the result was different, if it was after the midterm exam it was different, if it was during the last sessions of the semester the result was different … So it is not objective, it is always subjective….

Interviewees’ skeptical approaches towards SETs were also supported by quantitative data, in that 95.3% of the lecturers called upon students’ training for evaluating their teachers (Item 19: “Students should be informed of the criteria for identifying an effective teacher.”).

4.1.2 Students’ learning outcomes/achievement

Student achievement simply refers to the extent to which students can learn pre-determined content knowledge. Serving as a criterion for success in education, students achievement tends to be measured based on a score showing the students’ competence in learning (Bakar 2018). The quantitative data revealed that only nearly half of the respondents (51.2%) favoured students’ learning outcomes as an indicator of their effectiveness (Item 24: “Students’ learning outcomes (e.g. test results, achievement) can be a good indicator of teacher effectiveness.”). In addition, only 4.7% strongly expressed their concurrence with the idea which clearly testifies to the low status of such a measure of evaluation. In a similar vein, Sam lent weight to the importance of student achievement and posited:

To me, an effective teacher is someone who is or the extent someone is successful in his career, in his job. I mean, the results, the extent students are successful, can pass [the exams]… The extent the students can achieve the course….

It is worth reporting that 60.5% of respondents maintained that such a measure can go astray due to factors which are not in the hands of teachers (Item 22: “Students’ learning outcome is highly vulnerable to student-specific factors which are beyond teachers’ control.”).

4.1.3 Peer evaluation/observation

Peer evaluation is considered as one of the approaches to teacher evaluation and development (Looney 2011). It is an approach by which lecturers are evaluated by their colleagues with aim of cultivating student learning. The analysis of the quantitative data made known that 79.1% of the lecturers approved the contribution of peer evaluation to teacher effectiveness (Item 13: “Peer evaluation contributes to the improvement of teacher effectiveness.”). As to the goal of evaluation, 39.5% of the lecturers espoused the suitability of peer evaluation for summative purposes (Item 15: “Peer evaluation could be used for summative evaluation”). The results are rather surprising on the grounds that peer observation is not currently practiced as a measure of teacher appraisal in the context of this study.

The following excerpt from an interviewee indicates his preference for peer evaluation as a learning opportunity:

I do believe that peer assessments can help us to learn from each other… and to accelerate the process of effectiveness better. It can provide us with a very good picture of effectiveness …. (Soroush)

4.1.4 Self-evaluation

Teacher self-evaluation is another important aspect of teacher evaluation and development through which a teacher evaluates his/her teaching based on a set of criteria with the aim of improving his/her pedagogical and professional practices. Self-evaluation was supported by 95.3% of the respondents (Item 9: “Teachers’ self-evaluation will help them reflect on their own teaching practices.”). Notably, 74.4% of the lecturers thought well of self-evaluation for “formative” purposes (Item 11: “Self-evaluation should be used for formative purposes.”). Sepehr, one of the interviewees, expressed his support and stated:

… it should be a fair kind of evaluation because no one is more fair than you to yourself.

4.1.5 Observation (external/internal)

Observation is a process in teacher evaluation and development in which an outsider, e.g. principal, administrator, etc. monitors and observes teachers’ practices in the class. The results of the survey indicated that less than half the lecturers (46.5%) had a positive stance towards observation as a measure of evaluation (Item 53: “External observation should be considered as a measure of evaluation in the Iranian appraisal model.”). Moreover, 55.8% of participants expressed their opposition to an external format of observation, i.e. to be evaluated by an external appraiser (Item 26: “Teachers are not willing to be evaluated by an external observer.”).

The thematic analysis of the interviews culminated in strong support for observation. One supporting excerpt is as follows:

…Then select someone or a few people, two or three, depending on the size of the university to evaluate their works, at the beginning, middle, at the end. (Parham)

4.2 Features of an appraisal system

The analysis of the data showed traces of features of a successful appraisal system which from lecturers’ perspectives should be paid more attention, the most salient ones are summarised in Table 4, as follows.

4.2.1 Power relations

It is maintained that a teacher effectiveness evaluation system should be free from the web of power relations in which some teachers, regardless of their teaching capabilities, become privileged and underprivileged teachers based on power relations between teacher and administrators/appraisers. As to the survey, 58.1% of the lecturers concurred with the idea that appraisal can be affected by power relations (Item 54: “Power relations might dominate teacher appraisal.”). This was supported by qualitative data. Referring to the imbalance between power and knowledge, Niloofar maintained:

But I want to say that the gap is between power and knowledge; the one who has got the knowledge does not have the power and the one who has got the power I cannot see any knowledge in them.

4.2.2 Fair and convincing/knowledgeable appraisers

The results showed that 93% of the respondents maintained that the appraisal system should be convincing and assuring the fairness of the appraisal (Item 28: “Teachers need to be convinced of the fairness of the evaluation system through which they are assessed.”). The following excerpt pictures the interviewee’s call for a fair evaluation:

…Well, I want to be polite and nice but we have friends and we have enemies and …, that is again subjective… Some people are not fair. Can everybody be a good judge? … Of course not. It’s some personal characteristics, a fair-minded a fair-minded individual is needed to be a judge ….

The need for a set of fair criteria for teacher evaluation which is clear and transparent to both appraisers and teachers was also supported by qualitative data. As Niloofar put it forward:

… there are two strategies: one is to catch someone red-handed and two is to make improvements. If we are after improvement, everything must be crystal-clear….

Moreover, 95.4% of the respondents called for skilled and knowledgeable appraisers more than half of whom (51.2%) strongly agreed with the idea (Item 14: “Colleagues who evaluate a faculty need to be skilled in evaluation.”).

4.2.3 Multi-measure approach

The dire need for a multi-measures approach towards teacher evaluation received the lectures’ full support. Indeed, one of the statements arguing for a multi-measures approach were supported by 100% of the respondents (Item 7: “Administrators (e.g. Dean, Head of department) should adopt a multi-measure rather than a single-measure approach towards teacher effectiveness appraisal.”).

4.2.4 Transparency

The relevant literature reveals that the iniquitous systems of teacher appraisal are the ones in which teacher evaluation mechanism is rather unpublicised or vague. The need for transparent criteria for teacher evaluation received exceeding interest on the part of the lecturers (93%) from whom 48.8% strongly agreed with the idea (Item 27: “Teacher effectiveness should be evaluated based upon a set of transparent standards/criteria.”).

Transparency also emerged from the analysis of the interviews. Ali, for instance, mentioned:

When the expectations are clear then your job will become easier. Because you become aware of the values by which you will be evaluated.

4.2.5 Formative appraisal

Around two-thirds of respondents (69.7%) called for a formative-oriented teacher evaluation (Item 4: “Teachers’ appraisal should mostly focus on formative purposes, i.e. professional development.”). The following excerpt from Parham corroborates the results:

It should be formative one in order to help teachers to improve the quality of their work, the quality of what they’re doing, their performance, so it should be informative for the teachers themselves not for promotion….

4.2.6 Non-teacher-controlled factors affecting TE

For an appraisal system to be successful, it needs to control for some intervening variables. The statistical and thematic analyses of the datasets led to the emergence of several categories as shown in Table 5:

Curriculum and syllabi:

As to the survey, 62.8% of respondents gave prominence to national curriculum and syllabi as a boosting device for teaching (Item 60: “National curriculum and syllabi are important factors in promoting teachers effectiveness.”).

Also, referring to the need for tailoring the syllabi in order to accommodate the students’ needs, Sahand stated:

The teacher is the best syllabus designer. No outside influence should force him[/her] into reconsidering his term instruction. The only thing he should be informed about is the overall expectation of the syllabus results.

Facilities and equipment:

There is little doubt that by the outset of the third millennium and with the advent of technology and its exceeding expansion in education, facilities and equipment have often been at the heart of the quality of education. This issue was raised by Ali:

When you don’t have a laboratory [English Language Lab] okay how can you teach your students, for example, listening courses…, how?

Salary and financial incentives:

One factor which may interfere with teachers’ quality can be the financial incentives they receive. Majid, for instance, expressed his concerns over the financial side of his career and stated:

…But sometimes due to financial crisis or financial shortage teachers have to teach 50 hours, 60 hours a week, this is a catastrophe so they have to neglect quality because only quantity here works.

Student-related factors:

As to the survey, 60.5% believed that the same teacher could be of different degrees of effectiveness with different groups of students (Item 23: “An effective teacher might be less effective with a particular group of students or a particular course.”). Rima, one of the interviewees, touched upon this area and posited:

Some students are not motivated in learning … so having motivation in a student is very important.

Leadership/conflict of interest:

The results revealed that 72.1% of the respondents agreed upon the influential role of educational leadership in teacher effectiveness (Item 59: “Educational leadership tends to exert influence on teacher effectiveness.”).

However, one important point is the extent to which universities adhere to their publicised mission and vision. The findings showed “conflict of interests” between the universities’ understanding of education with that of their academic staff. This is apparent in the following quote from Niloofar:

… their policy might not necessarily be related to my policy and commitment as a teacher. As a teacher, I must, you know, uh be honest in the message I am sending but their policy might be attracting students…

5 Discussion

Students’ learning outcome was introduced as a measure of teacher effectiveness. This finding is consistent with the literature (e.g., Marsh 2007). Despite the overall consensus on the contributions of effective teachers to students’ achievement (e.g., Sanders et al. 1997; Tucker and Stronge 2005), the literature on students’ learning outcome as the main criterion for teacher evaluation is rather inconsistent. The famous quote from Angelo and Cross (1993, p. 3) which is “teaching without learning is just talking” may represent a group of stakeholders to whom effective teaching is nothing but students’ achievement.

The findings revealed that lecturers tend to give credit for SETs as a measure of evaluation. Our findings echo the enduring popularity of SETs in the literature expanding over decades (e.g., Cohen 1981; Marsh 2007). Despite their full support, nevertheless, teachers appeared to be rather skeptical about the validity and reliability of SETs; a concern which is also consonant with the relevant literature (e.g., Greenwald 1997; Spooren et al. 2013). Indeed, student ratings serve as a double-edged phenomenon in higher education with both proponents who view it as an elixir and opponents who regard it as nothing but indignation, and of course, a third group who fall in between (Feldman 2007). In addition, the “weight” assigned to SETs in the overall evaluation scoring system was one finding of this study on which little research has been conducted. There is little doubt that SETs can potentially be influenced by non-evaluative factors, e.g., teachers’ gender (e.g., Kierstead et al. 1988), Doctor Fox Effect (e.g., Peer and Babad 2014; Ware and Williams 1975), students’ lack of awareness of the working definition of effective teaching and its multidimensional nature. One intruding factor which should be thrust aside is the old yet contentious adage of “the better teachers’ scores, the better students’ SETs”. It has been suggested that teachers’ scoring, i.e. grading leniency and grading discrepancy (e.g., Griffin 2004), can impact students’ SETs, whereby students may praise or penalise their teachers based on their grades.

It was shown that peer evaluation was perceived mostly as a measure for “formative” purposes. Our findings are consistent with the literature. As an element for academic staff’s promotion and tenure (Kohut et al. 2007), peer evaluation/observation can be used for both formative purposes, i.e. feedback, on-the-job-training opportunity, and summative purposes, i.e., a supplementary measure for a multi-measure formal teacher appraisal (Looney 2011). However, relevant literature reveals that, compared to other measures of teacher evaluation, the effectiveness of peer evaluation/observation has not been much investigated (e.g., Kohut et al. 2007; Looney 2011). Similar to student ratings, peer evaluation should not be regarded simplistically as a box-ticking activity. Indeed, similar to students, peer teachers/colleagues themselves need to be well-briefed on the goals and standards of teacher appraisal. They should be well-trained with the skills needed for an effective appraisal. In short, what we need are “qualified” peer observers. Therefore, not all colleagues are equally capable of doing the evaluation; an issue which has seemingly escaped administrators’ attention. Furthermore, it appears that peer observers should be selected from among colleagues within the same department. Subject-specialist peers whose evaluations are based on the content of teaching (Shinkfield 1994, p. 259) and the challenges of L2 teaching can maximise the effectiveness of the appraisal. However, selection of observers and observees within the same department is not totally risk free and unbiased, particularly once peer observers are colleagues with the same or lower academic rank, and herein arises a number of concerns, e.g. peer observes’ feelings of rivalry, enmity, contempt, etc.

Despite its worldwide recognition as an important source of data in teacher evaluation (e.g., Nygaard and Belluigi 2011), self-evaluation was revealed as a missing measure in the context of this study. Serving as an empowerment tool, self-evaluation provides teachers with an opportunity to give voice to their wants, likes, dislikes, etc. The lecturers’ high regard for self-evaluation corroborates the previous studies (e.g., Kyriakides et al. 2002). Whereas teacher self-evaluation has enjoyed popularity, its application is rather under question (Marsh 2007). There is little doubt that self-evaluation needs to be complemented with other evaluation measures, on the grounds that hardly can all teachers do impartial and valid self-evaluation all of the time.

Finally, observation was found to be amongst the sources though which administrators can obtain information about one’s teaching effectiveness. As a common instrument to measure teachers’ progress (Caughlan and Jiang 2014), observation tends to be an important element in teacher appraisal (e.g., Stodolsky 1984). This finding is supported by the literature which is replete with studies recommending inclusion of observation as measure of teacher evaluation. As Danielson and McGreal (2000, p. 47) contend, for some, “teacher evaluations is synonymous with classroom observation”. Nevertheless, despite the rich history of observation in teacher evaluation systems, the extent to which such a measure may account for one’s teaching effectiveness is not well-investigated. Our findings indicated that the participants were rather skeptical about this measure. One reason for such apprehension seems to be due its summative nature and its job-related consequence thereupon.

As to the features of an ideal appraisal system, “transparency” of the standards or criteria for effective teaching was a feature which received strong support in this study. Indeed, teaching standards and the process of data collection should be clear, open, and transparent to teachers (e.g., Goe et al. 2012; Middlewood 2001). It is teachers’ indisputable right to know the expectations directed towards them on the part of policymakers and administrators. There is little hesitation that a fair appraisal system is contingent upon a transparent set of benchmarks on which there is an overall consensus.

Our findings placed much emphasis on a multi rather than a single-measure approach towards teacher evaluation. Given the complex and multidimensional nature of teaching, single-mode measurements may not demonstrate teachers’ real performance (Wilkerson et al. 2000, p. 180). The use of different sources of information can provide more realistic data, on the assumption that each and every single measure of evaluation, as stated earlier, carries with it a number of limitations and shortcomings. Indeed, multiple sources (evidence) can evaluate different constructs of teaching effectiveness (Peterson 1987) and hence can cover dimensions which are overlooked by some measures. The use of multiple measures provides administrators with an opportunity to crosscheck the results of each measure against other measures culminating in a rigorous and robust evaluation. However, the apportionment of the overall scoring among different measures is a contentious area on which the literature is rather sparse.

5.1 Evidence for context-specific and subject-specific teacher evaluation system

“Contextualisation” of the evaluation was one finding of overriding significance in this study. The results showed that the lecturers called for the so-called context-specific appraisal system which can accommodate the peculiarities of teaching across different educational contexts with different economic, political, socio-cultural dimensions. This idea was backed by 65.1% of respondents (Item 63: “The Iranian appraisal model needs to be informed by the political, cultural and social specificities in Iranian context”.). Moreover, the view that an appraisal system needs to be informed by TEFL-specific criteria was also advocated by 65.2% of lecturers (Item 3: “An EFL teacher effectiveness model needs to be evaluated upon TEFL-specific subject criteria rather than generic education criteria.”). The following quote from Majid is an example:

I think it should be classified according to the major of the lectures. There should be a kind of difference between someone who teaches English and someone who teaches Arts or someone who teaches Engineering. It should be field-specific, I think.

Perhaps our most salient finding is the irresistible urge for a differentiated teacher evaluation system enriched by a “glocalised” stance. In particular, the Iranian lecturers’ call for a context-specific and EFL-specific appraisal model brings to the fore concerns over the generic appraisal model or the so-called “one-size-fits-all” approaches towards teacher evaluation. Teaching is a multifaceted and contextualised phenomenon (Wilkerson et al. 2000, p. 180). There is little doubt about the role of context in teaching effectiveness (Darling-Hammond and Snyder (2000). The literature on academic discipline-specific teacher evaluation is yet in a state of flux. Despite few studies focused on subject-specific teacher appraisal (e.g., Gallagher 2004), further research is needed to bring to light how different issues such as appraisers’ academic background can exert impact on their evaluations of teachers with different academic expertise. As Campbell et al. (2004a, p. 2) contend, “the contexts and conditions in which students are enabled to learn can differ; students differ; the extent to which objectives for learning are achieved can differ; and the values underlying learning and effectiveness can differ.”

Our findings gave rise to a number of issues which from the participants’ perspectives, were beyond teachers’ control and hence need to be paid thorough attention throughout the process of teacher evaluation. It was shown that an effective teacher with one group of students may not necessarily be effective with another group, on the assumption that student-related factors such as age, gender, multiple intelligences can differ from one student to another. Further research is needed to identify the extent to which different student-specific characteristics can relate to teacher performance and hence teacher evaluation.

6 Conclusion

The multidimensional nature of teacher evaluation and its features were the mainstay of this study. Five measures of evaluation were introduced as sources of information for evaluating teacher effectiveness, viz. SETs, students’ learning outcomes, peer evaluation, self-evaluation, and observation. In addition, the findings revealed that a rigorous appraisal system is expected to retain a number of features the most salient of which include transparency, fairness, multiple measurement, formative evaluation, taking cognisance of unequal power relations, and the so-called non-teacher-controlled factors. Our findings were, in general, reminiscent of a differentiated approach towards teacher evaluation, whereby the role of the context within which teaching transpires, and the peculiarities, subtleties and eccentric features and challenges of teaching in a language different from both teachers and students’ mother tongue along with other contextual difference are taken into consideration. The findings are significant as they addressed a gap in the literature in terms of the context in which teacher evaluation is investigated, i.e. a non-western EFL context. It is concluded that whereas teaching is said to be a multifaceted phenomenon, the evaluation of teaching is surely a much more multidimensional, time-consuming, and formidable task. Repudiating the so-called one-size-fits-all approach towards teacher evaluation, the present study calls for a more pragmatic and multi-measure approach by which the voices of the main parties and stakeholders in educational systems, i.e., students, teachers, peers, administrators are included. The study also concludes that teacher evaluation could be most effective, provided that teachers are well informed of transparent criteria/standards and the consequences of evaluation. The interpretation of the results of teacher evaluation should be conducted with caution. Teachers should not be marked down as either effective, less effective, ineffective based upon a single one-off appraisal, given that research has brought into contention the idea that teachers tend to demonstrate equally similar degrees of effectiveness with various groups of students (e.g., Kelly 2009) in different contextual settings.

References

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Arthur, J., Winfred, B. J., Winston, E. P. S., & Bell, S. T. (2003). Effectiveness of training in organizations: A meta-analysis of design and evaluation features. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.234.

Bakar, R. (2018). The influence of professional teachers on Padang vocational school students’ achievement. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 39(1), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2017.12.017.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition and language education: Research and practice. London: Continuum.

Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2018). Doing interviews (2nd ed.). London: SAGE.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, J., Kyriakides, L., Muijs, D., & Robinson, W. (2003). Differential teacher effectiveness: Towards a model for research and teacher appraisal. Oxford Review of Education, 29(3), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980307440.

Campbell, J., Kyriakides, L., Muijs, D., & Robinson, W. (2004a). Assessing teacher effectiveness: Developing a differentied model. London: Routledge.

Campbell, J., Kyriakides, L., Muijs, D., & Robinson, W. (2004b). Effective teaching and values: Some implications for research and teacher appraisal. Oxford Review of Education, 30(4), 451–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305498042000303955.

Caughlan, S., & Jiang, H. (2014). Observation and teacher quality. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(5), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114541546.

Cheng, Y. C., & Tsui, K. T. (1999). Multimodels of teacher effectiveness: Implications for research. The Journal of Educational Research, 92(3), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220679909597589.

Cohen, P. A. (1981). Student ratings of instruction and student achievement: A meta-analysis of multisection validity studies. Review of Educational Research, 51(3), 281–309. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543051003281.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Coombe, C. A., Al-Hamly, M., Davidson, P., & Troudi, S. (2007). Evaluating teacher effectiveness in ESL/EFL contexts. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Crandall, J. (2000). Language teacher education. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 20, 34–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190500200032.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2015). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (5th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

Danielson, C., & McGreal, T. L. (2000). Teacher evaluation to enhance professional practice. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Darling-Hammond, L., Holtzman, D. J., Gatlin, S. J., & Heilig, J. V. (2005). Does teacher preparation matter? Evidence about teacher certification, teach for America, and teacher effectiveness. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13(42), 1–48.

Darling-Hammond, L., Newton, S. P., & Wei, R. C. (2013). Developing and assessing beginning teacher effectiveness: The potential of performance assessments. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 25(3), 179–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-013-9163-0.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Snyder, J. (2000). Authentic assessment of teaching in context. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(5–6), 523–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00015-9.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dörnyei, Z., & Taguchi, T. (2010). Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Doyle, W. (1977). Paradigms for research on teacher effectiveness. Review of Research in Education, 5, 163–198. https://doi.org/10.2307/1167174.

Feldman, K. A. (2007). Identifying exemplary teachers and teaching: Evidence from student ratings 1. In R. P. Perry & J. C. Smart (Eds.), The scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education: An evidence-based perspective (pp. 93–143). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Gallagher, H. A. (2004). Vaughn elementary’s innovative teacher evaluation system: Are teacher evaluation scores related to growth in student achievement? Peabody Journal of Education, 79(4), 79–107. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327930pje7904_5.

Gillham, B. (2008). Developing a questionnaire (2nd ed.). London: Continuum.

Goe, L., Bell, C., & Little, O. (2008). Approaches to evaluating teacher effectiveness: A research synthesis. Washington, DC: National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality.

Goe, L., Biggers, K., & Croft, A. (2012). Linking teacher evaluation to professional development: Focusing on improving teaching and learning. Washington, DC: National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality.

Greenwald, A. G. (1997). Validity concerns and usefulness of student ratings of instruction. American Psychologist, 52(11), 1182–1186. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.11.1182.

Griffin, B. W. (2004). Grading leniency, grade discrepancy, and student ratings of instruction. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 29(4), 410–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2003.11.001.

Harmer, J. (2007). How to teach English. Essex: Pearson Longman.

Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2010). Mixed methods research: Merging theory with practice. New York: Guilford Publications.

Hornstein, H. A. (2017). Student evaluations of teaching are an inadequate assessment tool for evaluating faculty performance. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1304016. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1304016.

Januszewski, A., & Molenda, M. (2008). Educational technology: A definition with commentary. New York, NY: Routledge.

Johnson, K. E. (2009). Second language teacher education: A sociocultural perspective. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kane, T. J., Rockoff, J. E., & Staiger, D. O. (2008). What does certification tell us about teacher effectiveness? Evidence from New York City. Economics of Education Review, 27(6), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2007.05.005.

Kelly, S. (2009). Tracking teachers. In L. J. Saha & A. G. Dworkin (Eds.), International handbook of research on teachers and teaching (Vol. 21, pp. 451–461). New York, NY: Springer.

Kierstead, D., D’Agostino, P., & Dill, H. (1988). Sex role stereotyping of college professors: Bias in students’ ratings of instructors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(3), 342–344. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.3.342.

Kohut, G. F., Burnap, C., & Yon, M. G. (2007). Peer observation of teaching: Perceptions of the observer and the observed. College Teaching, 55(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.55.1.19-25.

Kupermintz, H. (2003). Teacher effects and teacher effectiveness: A validity investigation of the Tennessee value added assessment system. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25(3), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737025003287.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interivews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kyriakides, L. (2007). Generic and differentiated models of educational effectiveness: Implications for the improvement of educational practice. In T. Townsend (Ed.), International handbook of school effectiveness and improvement (pp. 41–56). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Kyriakides, L., Campbell, R. J., & Christofidou, E. (2002). Generating criteria for measuring teacher effectiveness through a self-evaluation approach: A complementary way of measuring teacher effectiveness. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 13(3), 291–325. https://doi.org/10.1076/sesi.13.3.291.3426.

Looney, J. (2011). Developing high-quality teachers: Teacher evaluation for improvement. European Journal of Education, 46(4), 440–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2011.01492.x.

Marsh, H. W. (2007). Students’ evaluations of university teaching: Dimensionality, reliability, validity, potential biases and usefulness. In R. P. Perry & J. C. Smart (Eds.), The scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education: An evidence-based perspective (pp. 319–383). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Mazandarani, O. (2014). EFL lecturers’ perceptions of teacher effectiveness and teacher evaluation in Iranian universities. Doctoral Thesis. University of Exeter, Exeter.

Mazandarani, O. (2020). The status quo of L2 vis-à-vis general teacher education. Educational Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1729101.

Mazandarani, O., & Troudi, S. (2017). Teacher evaluation: What counts as an effective teacher? In S. Hidri & C. Coombe (Eds.), Evaluation in foreign language education in the Middle East and North Africa. Cham: Springer.

McBer, H. (2000). Research into teacher effectiveness: A model of teacher effectiveness. Research Report No. 216. London: Report by Hay McBer to the Department for Education and Employment (DfEE).

Middlewood, D. (2001). The future of managing teacher performance and its appraisal. In D. Middlewood & C. E. M. Cardno (Eds.), Managing teacher appraisal and performance: A comparative approach (pp. 180–195). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Muijs, D., Kyriakides, L., van der Werf, G., Creemers, B., Timperley, H., & Earl, L. (2014). State of the art – teacher effectiveness and professional learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(2), 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.885451.

Nygaard, C., & Belluigi, D. Z. (2011). A proposed methodology for contextualised evaluation in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(6), 657–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602931003650037.

Oppenheim, A. N. (1992). Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement. London: Continuum.

Ostovar Namaghi, S. A. (2010). A data-driven conceptualization of teacher evaluation. The Qualitative Report, 15(6), 1504–1522.

Peer, E., & Babad, E. (2014). The Doctor Fox research (1973) rerevisited: “Educational seduction” ruled out. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033827.

Peterson, K. D. (1987). Teacher evaluation with multiple and variable lines of evidence. American Educational Research Journal, 24(2), 311–317. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312024002311.

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Elam, G. (2003). Designing and selecting samples. In J. Ritchie & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (pp. 77–108). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Ryans, D. G. (1949). The criteria of teaching effectiveness. The Journal of Educational Research, 42(9), 690–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1949.10881737.

Sanders, W. L., Wright, S. P., & Horn, S. P. (1997). Teacher and classroom context effects on student achievement: Implications for teacher evaluation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 11(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1007999204543.

Shinkfield, A. J. (1994). Principal and peer evaluation of teachers for professional development. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 8(3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00973724.

Shinkfield, A. J., & Stufflebeam, D. L. (1996). Teacher evaluation: Guide to effective practice. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Spooren, P., Brockx, B., & Mortelmans, D. (2013). On the validity of student evaluation of teaching: The state of the art. Review of Educational Research, 83(4), 598–642. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313496870.

Stodolsky, S. S. (1984). Teacher evaluation: The limits of looking. Educational Researcher, 13(9), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X013009011.

Stronge, J. H., Ward, T. J., & Grant, L. W. (2011). What makes good teachers good? A cross-case analysis of the connection between teacher effectiveness and student achievement. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(4), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487111404241.

Teddlie, C., & Yu, F. (2007). Mixed methods sampling. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906292430.

Tucker, P. D., & Stronge, J. H. (2005). Linking teacher evaluation and student learning. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Ware, J. E. J., & Williams, R. G. (1975). The Dr. Fox effect: A study of lecturer effectiveness and ratings of instruction. Academic Medicine, 50(2), 149–156.

Wilkerson, D. J., Manatt, R. P., Rogers, M. A., & Maughan, R. (2000). Validation of student, principal, and self-ratings in 360° feedback® for teacher evaluation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 14(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1008158904681.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Close-ended questionnaire

Appendix: Close-ended questionnaire

Please read each statement and put a tick under your chosen response.

Item no. | Statement | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Strongly agree | agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

1. | Different stakeholders’ voices e.g. teachers, students, administrators, etc. who have a stake in teaching, should be heard and incorporated into the appraisal model | |||||

2. | A friendly personality is important to teacher effectiveness | |||||

3. | An EFL teacher effectiveness model needs to be evaluated upon TEFL-specific subject criteria rather than generic education criteria | |||||

4. | Teacher s’ appraisal should mostly focus on formative purposes, i.e. professional development | |||||

5. | Teachers’ appraisal should mostly focus on summative purposes, e.g. promotion, tenure, etc | |||||

6. | Teacher effectiveness appraisal should mainly focus on teachers’ performance | |||||

7. | Administrators (e.g. Dean, Head of department) should adopt a multi-measure rather than a single-measure approach towards teacher effectiveness appraisal | |||||

8. | Appraisal models mainly depend on students ratings with less attention given to other stakeholders such as teachers | |||||

9. | Teachers’ self-evaluation will help them reflect on their own teaching practices | |||||

10. | Teachers’ beliefs tend to exert influence on teacher effectiveness | |||||

11. | Self-evaluation should be used for formative purposes | |||||

12. | Self-evaluation should be used for summative purposes | |||||

13. | Peer evaluation contributes to the improvement of teacher effectiveness | |||||

14. | Colleagues who evaluate a faculty need to be skilled in evaluation | |||||

15. | Peer evaluation could be used for summative evaluation | |||||

16. | Teacher s’ gender tends to exert influence on students’ ratings | |||||

17. | Teacher s’ age tends to have impacts on students’ ratings | |||||

18. | Teachers who give high marks tend to be rated as more effective by students | |||||

19. | Students should be informed of the criteria for identifying an effective teacher | |||||

20. | The easier the course, the higher the students’ ratings of their teachers | |||||

21. | It is a good idea to collect students’ ratings in mid-semester in order to eliminate the “grading bias” effect | |||||

22. | Students’ learning outcome is highly vulnerable to student-specific factors which are beyond teachers’ control | |||||

23. | An effective teacher might be less effective with a particular group of students or a particular course | |||||

24. | Students’ learning outcomes (e.g. test results, achievement) can be a good indicator of teacher effectiveness | |||||

25. | Administrators’ (e.g. Dean, Head of Department, etc.) appraisal is subjective and biased | |||||

26. | Teachers are not willing to be evaluated by an external observer | |||||

27. | Teacher effectiveness should be evaluated based upon a set of transparent standards/criteria | |||||

28. | Teachers need to be convinced of the fairness of the evaluation system through which they are assessed | |||||

29. | There is a direct correlation between teacher s’ level of academic qualifications and their effectiveness | |||||

30. | Universities from which teachers have graduated are influential factors in their effectiveness | |||||

31. | An effective teacher has excellent pedagogical skills | |||||

32. | Teachers’ subject knowledge lies at the heart of teacher effectiveness | |||||

33. | Effective EFL teachers should have TEFL-driven understanding of teaching | |||||

34. | Teacher leadership contributes to teacher’s effectiveness | |||||

35. | Teachers’ personal traits (e.g. patience) play an important role in their effectiveness | |||||

36. | Teachers’ language proficiency does not contribute to teacher effectiveness | |||||

37. | Effective language teachers should consider Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) in their teaching practices | |||||

38. | Effective language teachers dedicate themselves to their students to the extent that their needs are met | |||||

39. | Effective teachers are open to their students’ voices | |||||

40. | Teacher authority is the keystone of the notion of teacher effectiveness | |||||

41. | Effective teachers are accountable to other stakeholders, e.g. students, administrators, etc. | |||||

42. | An effective teacher respects the students | |||||

43. | An effective language teacher engages all students in classroom activities | |||||

44. | EFL teachers should have the required knowledge of curriculum development, lesson plan, syllabus design, etc. | |||||

45. | An effective TEFL teacher is familiar with assessment strategies for assessing learners’ different language skills | |||||

46. | Effective language teachers tend to be sensitive to important issues such as students’ race, social class, etc. | |||||

47. | Teachers’ experience is a cornerstone of their teaching effectiveness | |||||

48. | An effective teacher establishes a friendly environment in the classroom | |||||

49. | An effective teacher knows how to deal with unexpected situations in the classroom | |||||

50. | An effective teacher should be innovative | |||||

51. | I am not well-aware of the evaluation system and the appraisal model adopted by administrators for evaluating teacher effectiveness in the Iranian higher education | |||||

52. | The existing appraisal model used in the Iranian higher education is a reliable and valid indicator of my teaching effectiveness | |||||

53. | External observation should be considered as a measure of evaluation in the Iranian appraisal model | |||||

54. | Power relations might dominate teacher appraisal | |||||

55. | Universities should have units that provide technical and general advice to less effective teachers | |||||

56. | I am happy with the existing appraisal model adopted in my university | |||||

57. | There is a need to revisit the existing Iranian appraisal model | |||||

58. | Developing an accredited professional preparation programme will not help teachers gain the required skills | |||||

59. | Educational leadership tends to exert influence on teacher effectiveness | |||||

60. | National curriculum and syllabi are important factors in promoting teachers effectiveness | |||||

61. | Designing a good teacher education programme (TEP) for pre-service teachers can contribute to their teaching effectiveness | |||||

62. | Staff development programme such as Teacher Development Programme (TDP) can promote teacher effectiveness | |||||

63. | The Iranian appraisal model needs to be informed by the political, cultural and social specificities in Iranian context | |||||

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mazandarani, O., Troudi, S. Measures and features of teacher effectiveness evaluation: perspectives from Iranian EFL lecturers. Educ Res Policy Prac 21, 19–42 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-021-09290-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-021-09290-0