Abstract

Many philosophers embrace grounding, supposedly a central notion of metaphysics. Grounding is widely assumed to be irreflexive, but recently a number of authors have questioned this assumption: according to them, it is at least possible that some facts ground themselves. The primary purpose of this paper is to problematize the notion of self-grounding through the theoretical roles usually assigned to grounding. The literature typically characterizes grounding as at least playing two central theoretical roles: a structuring role and an explanatory role. Once we carefully spell out what playing these roles includes, however, we find that any notion of grounding that isn’t irreflexive fails to play these roles when they are interpreted narrowly, and is redundant for playing them when they are interpreted more broadly. The upshot is that no useful notion of grounding can allow a fact to ground itself.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the last ten years or so, more and more philosophers have become interested in grounding: a distinctively metaphysical notion of determination that can bear an explanatory burden more familiar concepts (especially modal ones) cannot.Footnote 1 Grounding is usually thought to be irreflexive.Footnote 2 On the face of it the irreflexivity assumption is fairly intuitive and can even be seen as key to the original motivating thought that grounding correlates with a kind of structural and explanatory directedness. Despite this intuitive appeal, a number of authors (Jenkins 2011; Bliss 2014; Correia 2014; Wilson 2014; Rodriguez-Pereyra 2015) have argued that there might be genuine cases of self-grounding.Footnote 3 This paper argues that contrary to these authors’ view, any useful notion of grounding would have to be irreflexive.

Before getting into further details, some minimal regimentation of the target notion is necessary. Some prefer to stay neutral on the existence of a grounding relation and express grounding connections with the sentential connective ‘because’.Footnote 4 Following most of the literature, however, I will treat grounding as a relation between facts.Footnote 5 This will make the exposition more accessible, in part because understanding irreflexivity in relational terms is more straightforward, and in part because authors who have questioned the irreflexivity assumption have typically done so in relational terms.Footnote 6 As far as I can see, the discussion to follow could be recast in line with the connective view.Footnote 7

The literature customarily distinguishes between full and partial grounding. Intuitively speaking, a full ground makes a fact obtain on its own, while a partial ground helps it obtain, possibly along with some other facts. More precisely, we can understand both full and partial grounding as binary relations with a plural argument place for the grounding facts and a singular argument place for the grounded fact.Footnote 8 Then partial grounding can be defined in terms of full grounding: f 1…f m partially ground g iff there are some facts g 1…g n such that f 1…f m are among g 1…g n and g 1…g n together fully ground g.Footnote 9 (Note that we allow for degenerate pluralities consisting of only one fact. So when f is a full ground of g it’s also automatically a partial ground of g.)

In light of the distinction between full and partial grounding, we can get a better handle on what the rejection of irreflexivity amounts to by distinguishing between two options: (i) some fact f fully grounds f; (ii) some fact f partially grounds f. In the sequel I will focus on the second option, and accordingly, by ‘grounding’ I will always mean partial grounding unless indicated otherwise. Since my goal is to problematize self-grounding, this is a legitimate move: by the above definition, if f fully grounds f then it also partially grounds f, so any objection to partial self-grounding also spells trouble for full self-grounding. Now we can state a relatively precise target:

(Self-grounding Thesis) Possibly, there is a fact f such that f partially grounds f Footnote 10

Before getting into the details of the Self-grounding Thesis, it’s worth looking at two sorts of cases that have been proposed as potential counterexamples to the irreflexivity of grounding. The first one is due to Carrie Jenkins (2011) and goes as follows (Jenkins imposes no restrictions on the grounding relata, so I recast her example in terms of facts). One intuitive umbrella characterization of physicalism is that mental facts are grounded in physical facts. For example, the fact that I’m in a particular brain state grounds the fact that I’m in a particular pain state. Surely, the identity theory of the mind is faithful to the core idea of physicalism. However, this seems difficult to reconcile with the irreflexivity of grounding: the fact that I’m in such and such brain state cannot ground and at the same time be identical to the fact that I’m in such and such pain state. An obvious way out is to give up the irreflexivity assumption: mental facts are grounded in, but also identical to, physical facts. So the fact that I’m in the brain state grounds and is identical to the fact that I’m in the pain state.Footnote 11

The second example comes from an opponent of self-grounding, Kit Fine, who presents it as a paradox. Take the fact that something exists. (Here and in what follows, I will follow the convention—first introduced by Rosen (2010)—of representing facts with the ‘[‘, ‘]’ notation: ‘[S]’ abbreviates ‘the fact that S’.) Plausibly, for any fact f, f grounds the fact [f exists]. Substituting [Something exists] for f, we get that [Something exists] grounds [[Something exists] exists]. On the other hand, it’s also plausible that the existentially quantified fact that something exists is partially grounded by each of its witnesses. So, [[Something exists] exists] grounds [Something exists]. We therefore get that that [Something exists] and [[Something exists] exists] ground each other. By transitivity [Something exists] grounds itself, contradicting irreflexivity.Footnote 12

In what follows I will discuss the notion of self-grounding in much more detail; these examples serve to give an idea as to what its instances might intuitively look like. There may be further examples, but we already have enough on our plate.Footnote 13

One natural reaction to the counterexamples is to try to explain them away in irreflexivity-friendly ways. Many opponents of self-grounding have pursued this strategy,Footnote 14 but in what follows I will try something altogether different. Instead of discussing the individual counterexamples, I will argue directly that the Self-grounding Thesis cannot be true of any serviceable notion of grounding.Footnote 15 In Sect. 2, I will take a closer look at the theoretical roles assigned to grounding and will distinguish two that are fairly uncontroversial: a structuring and an explanatory role. Then in Sects. 3 and 4 I will argue that any interesting notion of grounding has to come close enough to playing these roles, and that any notion that satisfies this constraint is bound to be irreflexive.

My approach is in a sense more and in a sense less ambitious than trying to meet the counterexamples to irreflexivity head-on. On the one hand, it promises to give grounding enthusiasts a completely general reason for taking grounding to be irreflexive. On the other hand, it doesn’t specify where the counterexamples go wrong, and for all it says we might be left with no better choice than to reject the irreflexivity assumption. What I have in mind can be better understood by focusing again on Fine’s earlier mentioned puzzle. As I said, I believe that no useful notion of grounding can fail to be irreflexive. Suppose, however, that the formal principles that generate the puzzle also impose non-negotiable constraints on the target notion. If that is so, Fine-style puzzles show that the standing notion of grounding falls under jointly inconsistent constraints, and that nothing comes close enough to playing the grounding roles.

It’s crucial to keep in mind this feature of my approach throughout the rest of the paper. I will argue only that any useful notion of grounding is irreflexive, but I won’t try to explain away the apparent counterexamples to irreflexivity. For all I know, those counterexamples successfully show that nothing corresponds to my orthodox, irreflexive notion of grounding—it’s just that in that case, they also show that nothing deserves to be called ‘grounding’.Footnote 16 So rather than contributing to the existing literature on the counterexamples to irreflexivity, this paper offers a broader perspective on what is at stake in these debates. If you are confident that none of the arguments against irreflexivity works, the paper should reaffirm your conviction that grounding is irreflexive. If you find some of those arguments persuasive, you should stop being a grounding enthusiast.

2 The grounding roles

Above I presented two putative examples of self-grounding. But merely contending that there are counterexamples to irreflexivity doesn’t yet carve out an interesting notion of grounding that fails to be irreflexive. This can be appreciated by noting that there is a fairly standard use of the word ‘grounding’ in which it picks out a reflexive notion: it’s possible to introduce a new expression (say, ‘improper grounding’), stipulate that any fact improperly grounds itself, and distinguish between grounding in the narrow sense (the relation people usually have in mind when talking about grounding) and grounding in a broader sense (proper-or-improper grounding, which allows for self-“grounding”). There is nothing wrong with recognizing self-grounding in this sense: it may be terminologically and technically convenient to do so, similarly to well-entrenched distinctions between other metaphysical relations and their limiting cases. For example, it is standard to distinguish between proper parthood and parthood in mereologyFootnote 17; it is equally harmless to introduce broader notions of constitution, realization, and ontological dependence, according to which every material object constitutes itself, every property realizes itself, and every entity ontologically depends on itself. It is often formally convenient to regard identity as a special case of these relations, even though the philosophical contexts in which they do their work are not the ones in which they collapse into identity.Footnote 18

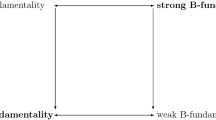

Grounding is no different in this regard. Many philosophers, whom I shall refer to as “dualists”, have already introduced non-standard notions of grounding that also include identity as a limiting case: proper-or-improper grounding (Schaffer 2009), weak ground (Fine 2012a, b), non-strict grounding (Correia 2014), etc. In what follows, I will collectively refer to these as “broad notions of grounding”.Footnote 19 Since the list of these notions is constantly growing, I cannot give a definition of what makes a notion of grounding broad. However, the following looks like a sufficient condition: if reflexivity is (or follows from) a stipulated property of a notion of grounding, then that notion of grounding is broad. By contrast, that notion of grounding that is widely assumed to be irreflexive, and whose irreflexivity self-grounders urge us to at least treat as an open question, is narrow. (In this regard, the narrow notion of grounding differs from the concept of strict ground, which is usually taken to be irreflexive by definition. Of course, irreflexivists think that narrow grounding is strict ground, but this is a substantive—if highly plausible—claim. See the next section for more on strict ground.)

While not all philosophers distinguish between grounding in the narrow sense and grounding in the broad sense, I know of no one who in principle rejects the distinction.Footnote 20 However, while we can extend the use of ‘grounding’ to cover identity, it is hardly news to be told that a fact can ground itself in this broader sense. For the Self-grounding Thesis to be interesting, we need to understand it as applying not merely to the broad notions of grounding, such as Schaffer’s proper-or-improper grounding or Fine’s weak ground.

This is a crucial point. Self-grounders often lament about grounding theorists’ tendency to uncritically assume that grounding is irreflexive (Jenkins 2011; Bliss 2014; Wilson 2014). But dualist approaches are standard fare, and nobody objects to them merely by insisting that grounding is irreflexive. So to make sense of the self-grounders’ complaint, we need to interpret them as saying that the narrow notion of grounding is widely and uncritically assumed to be irreflexive. In what follows, by ‘grounding’ I will always mean this narrow notion unless indicated otherwise. Note that this doesn’t beg any question against self-grounders; on the contrary, to ensure that the dispute isn’t merely verbal we need to understand them as arguing that that notion which dualists think is irreflexive isn’t irreflexive. To substantiate this claim, the self-grounder needs a notion that isn’t irreflexive but can play the grounding roles.

Why are these roles so important? Almost everyone agrees that we cannot reductively analyze grounding in other terms. However, we can still ask what grounding is good for, what theoretical roles a useful notion of grounding would have to play. While such role-specification won’t suffice for an analysis, it can give us some traction on what a relation has to be like to qualify as a candidate for being grounding. Recently, Dorr and Hawthorne (2013) took a similar approach to the notion of naturalness: debates over the utility of naturalness-talk become more tractable if we move away from the question of whether such talk is in good standing and focus on what could play the commonly accepted naturalness roles. Likewise, we can best approach the question of whether self-grounding is possible by asking whether a non-irreflexive notion could play the grounding roles. And since, as I argued above, the self-grounder should be interpreted as offering a revisionary conception of the narrow notion of grounding, what we are looking for is something that is a good candidate for playing the theoretical roles of grounding but whose roles are distinguishable from those of the broad notions.

What are these theoretical roles? While there is disagreement over questions of detail, two roles stand out as relatively uncontroversial: a structuring and an explanatory role. I will briefly describe these roles below, and in doing so, I will characterize them the way orthodox irreflexivists would. This is fair game. These characterizations are both widely accepted and prima facie plausible; self-grounders should at least strive to capture their spirit, to the extent that their denial of irreflexivity allows them to. In the sections to follow, we will see a number of (as I will argue, unsuccessful) attempts to weaken these roles. But in the meantime, these initial role-specifications will be useful starting points from which the rest of the discussion can take off.

First, the structuring role. The notion of grounding is often thought to “limn the ultimate structure of reality”: grounding tracks metaphysical priority, just like causation tracks temporal priority.Footnote 21 For one, if there is an absolutely fundamental level, it may best be described in terms of grounding: a fact is fundamental iff it’s ungrounded. For another, while the notion of relative fundamentality has no such straightforward analysis in terms of grounding, there is usually thought to be a tight link between the two notions: if f grounds g then f is more fundamental than, or metaphysically prior to, g.Footnote 22 This way, grounding can supposedly help us make sense of a layered picture of the world that more familiar concepts like supervenience, entailment or reduction cannot capture.Footnote 23

Second, the explanatory role. Grounding is widely seen as a distinctively metaphysical explanatory notion. This is often summarized by the slogan that grounding underlies ‘in virtue of’ and ‘because’ claims in metaphysical contexts.Footnote 24 However, the precise connection between grounding and explanation remains controversial. The controversy takes place against the backdrop of a widely shared assumption: explanatory realism, the view that explanations are backed by objective structural-determinative connections. As Ruben puts it, “[e]xplanations work, when they do, only in virtue of underlying determinative or dependency structural relations in the world” (1990: 210).Footnote 25 Explanatory realism doesn’t settle the exact relation between grounding and metaphysical explanation. One possible view is that grounding just is metaphysical explanation: the fact that f grounds g is itself an explanation in which f is the explanans and g the explanandum. (In line with my focus on partial grounding, in what follows by ‘explanans’ I will mean a partial explanans. Of course, every full explanans is also a partial explanans).Footnote 26 The other option is that grounding “backs” or “underlies” metaphysical explanation but isn’t identical to it.Footnote 27 The chief motivation for this latter view lies in the intuition that explanatoriness has an epistemic aspect that has no place in grounding, a supposedly mind-independent and objective relation. Audi, for example, tentatively suggests that grounding is necessary but not sufficient for metaphysical explanation: the latter requires an underlying grounding fact and that certain pragmatic and epistemic constraints also be in place (2012a: 119–120).

Here’s a way to make sense of this latter idea (my presentation borrows elements of Jenkins 2011, though Jenkins has different goals with the example, and doesn’t distinguish between grounding and metaphysical explanation). Perhaps ‘grounds’ is referentially transparent, but ‘explains’ isn’t: to get a metaphysical explanation, we also need the grounding fact and the grounded fact to appear under the right conceptual guises. Suppose, for instance, that [Sample S has H and O parts bound in such and such a way] grounds [Sample S is water], and that [Sample S is H2O] is identical to [Sample S is water]. If ‘explains’ isn’t referentially transparent, it’s conceivable that (1) is true while (2) is false:

- (1)

[Sample S has H and O parts bound in such and such a way] explains [S is H2O]

- (2)

[Sample S has H and O parts bound in such and such a way] explains [S is water]

You don’t need to accept this particular example to understand the basic idea: metaphysical explanation is a matter of tracing grounding connections and presenting them in an informative way. For the time being, I will put this view to the side; it will be relevant again in Sect. 4, where I will sketch a position that allows for self-grounding but not self-explanation. In this paper, I won’t decide between the “grounding is metaphysical explanation” and the “grounding backs metaphysical explanation” views, since my main argument doesn’t turn on the distinction (the distinction will matter for some possible responses to the argument and will be discussed in due course).Footnote 28

This closes my discussion of the structuring and explanatory roles. Are there any other theoretical roles for grounding? Some readers might think there are. For example, perhaps the impure logic of grounding (the interaction of grounding with the logical connectives) circumscribes a further set of theoretical roles (Correia 2005: Ch. 3, 2010, 2014; Rosen 2010; Fine 2012a). Others think that there are tight links between grounding and essence (Audi 2012a; Fine 2001, 2012a, 2015; Correia 2013) or reduction understood in terms of real definition (Rosen 2010). Yet others think that grounding plays an important explicatory role in helping us analyze other philosophically important notions, such as intrinsicality, truthmaking, and physicalism (see Witmer et al. 2005; Marshall 2015; Rodriguez-Pereyra 2005; Dasgupta 2014b for respective examples of each).

I don’t have much to say about these putative theoretical roles. I consider them more dubious than the structuring and explanatory roles, but the argument of the next few sections doesn’t rely on my doubts. All I will assume is that the structuring and the explanatory role are among the core theoretical roles of grounding (though perhaps not the only ones), and therefore the self-grounder has a serious problem if she has to give up either. In the next two sections I will assess the prospects of the Self-grounding Thesis in light of the structuring and the explanatory roles.

3 Self-grounding and the structuring role

Is the Self-grounding Thesis compatible with the structuring role? One important consequence of this role, as formulated above, is that a grounding fact is always more fundamental than the fact it grounds. This appears to rule out the Self-grounding Thesis: if f grounds g then f is more fundamental than itself, which is absurd.

Presumably, the self-grounder will object that the structuring role has been characterized too narrowly: implying the relation being more fundamental than isn’t the only way of imposing relations of relative fundamentality; implying the relation being as fundamental as is also a way of doing that. Grounding only has to conform to the following principle:

(Revised Fundamentality) If f grounds g then f is at least as fundamental as g

Since any fact is exactly as fundamental as itself, a non-irreflexive notion of grounding can play the structuring role.

Does Revised Fundamentality get the self-grounder off the hook? I don’t think so. If self-grounding is possible, then it looks like a counterexample to the claim that grounding plays the structuring role as originally understood. Addressing the counterexample requires more than absorbing it into the structuring role’s formulation. Otherwise we end up with a version of the structuring role that is already played by the broad notion of grounding. After all, it’s also true of weak ground and improper grounding that if f weakly/improperly grounds g, then f is at least as fundamental as g. This means that with respect to their structuring role there is no discernible difference between the broad notions of grounding and the narrow notion as the self-grounder conceives of it, which makes the latter redundant for playing the structuring role (understood as Revised Fundamentality). While a concept doesn’t need to be uniquely characterized by the theoretical roles it is assigned to in order to be intelligible, these roles should at least be different from the roles assigned to familiar concepts in its vicinity.

I should make it clear that the worry is not that there is nothing to distinguish the self-grounder’s conception of the narrow notion of grounding from the irreflexivist’s broad notion.Footnote 29 There is at least one fairly obvious difference between the two: they differ in their putative extension. The broad notions are reflexive, i.e. every fact bears them to itself, whereas self-grounders don’t normally think that (in the narrow sense) everything grounds itself. However, merely pointing out this difference in extension doesn’t yet give us an interesting revisionary conception of grounding. For that, we would need to know what grounding (as the self-grounder conceives of it) is good for in the sense explained in Sect. 2, i.e. how it’s related to relative fundamentality. To the extent that the playing of Revised Fundamentality doesn’t distinguish the self-grounder’s supposedly revisionary conception from the broad notions, it falls short of a giving a satisfactory role-specification. Moreover, if we accept my earlier methodological assumption that to get a grip on grounding we would need to get a grip on what it does, we should conclude that Relative Fundamentality doesn’t help us get a grip on the self-grounder’s notion of grounding.

The self-grounder’s notion of grounding might be thought to also play a second important role: although it doesn’t satisfy the original fundamentality role, it can be used to define a notion that does. One could define a notion of “super-strict” ground that is stipulated to be irreflexive: f 1 super-strictly grounds f 2 iff f 1 grounds f 2 but not vice versa. Unfortunately, self-grounding is also redundant for playing this explicatory/definitional role, since the broad notions already play this role, too. “Super-strict” grounding could also be defined in terms of the broad notions, e.g. weak ground: f 1 super-strictly grounds f 2 iff f 1 weakly grounds f 2 but not vice versa (Fine (2012a, b) gives a similar definition of strict ground). So, specifying the structuring role that the self-grounder’s notion of grounding is supposed to play in terms of (i) Revised Fundamentality and (ii) figuring in the definition of a stricter notion that plays the original fundamentality role, still doesn’t give us a good grip on the notion.

Why should the self-grounder worry that the broad notions of grounding make her revisionary conception of the narrow notion redundant? Take the following analogy. It’s common to distinguish between two roles for properties: on a sparse conception, properties are the things that explain similarity in nature and confer causal powers on their bearers, while on an abundant conception properties are the meanings of our predicates (Lewis 1983). Call properties in the first sense ‘universals’ and properties in the second sense ‘concepts’. Suppose we accept disjunctive concepts, but not disjunctive universals; perhaps we have been convinced by Armstrong’s (1978) arguments against them (call this view “Armstrongian”). What, then, are we to make of an anti-Armstrongian who insists that there are disjunctive universals? Obviously, we would want him to say more about how disjunctive universals could play the theoretical roles assigned to universals. Consider the following answer: universals explain similarity in nature and bestow causal powers on their bearers, except when they are disjunctive. Disjunctive universals are simply the meanings of our predicates, but they are universals nonetheless. Of course, this is a terrible answer. By giving it, the anti-Armstrongian fails to discharge the burden of explaining how he can weaken the theoretical roles while still offering a revisionary view of properties-qua-universals. If he simply admits these exceptions but adds nothing more to his theory, there will be no theoretical roles left for his properties-qua-universals to play that aren’t already played by the Armstrongian’s properties-qua-concepts. At this point, the Armstrongian may reasonably complain that the anti-Armstrongian hasn’t done enough to articulate theoretical roles for his supposedly revisionary conception of universals that differ from those played by her very ordinary conception of concepts.

Note that as in the previous case, the problem is not that there is no difference between what the Armstrongian means by ‘concept’ and what the anti-Armstrongian means by ‘universal’. The anti-Armstrongian doesn’t have to say that every disjunctive predicate picks out a universal in his sense, so the two will probably differ in their putative extension. Rather, the challenge is that universals, as the anti-Armstrongian conceives of them, don’t play the originally assigned “universal role”, and the revised role they are supposed to play doesn’t differ from that of the Armstrongian’s concepts. We still don’t know anything informative about how universals are linked to causal powers or similarity in nature. Importantly, just like in the case of the Self-grounding Thesis, this isn’t a challenge that the anti-Armstrongian in principle cannot meet. He might be able to offer a story about how certain disjunctive properties could explain similarity in nature and bestow causal powers on their bearers (see Clapp 2001). But any answer along these lines amounts to the claim that disjunctive properties-qua-universals differ from the Armstrongian’s properties-qua-concepts with respect to the theoretical roles they play.

To some, switching to Revised Fundamentality will not look quite as bad as the anti-Armstrongian’s response. For example, one might point out that at least one of the broad notions, namely Fine’s weak ground, captures a certain position in the explanatory hierarchy: when f weakly grounds g, f is not higher in the order of explanation than g. Not standing higher in the explanatory order is very similar to standing lower in it, i.e. to the kind of explanatory priority that strict ground is supposed to capture. By contrast, the objector might continue, we cannot say anything similar about universals and concepts.Footnote 30 Now, I’m not so sure about this. For example, the anti-Armstrongian could say that both universals and concepts track some sort of similarity: two things falling under the same concept are similar in how some language represents them, whereas two things falling under the same universal are also similar in how a joint-carving language would represent them. But never mind. Even if weak ground is closer to strict ground than concepts are to universals, I don’t think this undermines the main point of my analogy. This is because the relevant analogy isn’t between the weak ground/strict ground and the universals/concepts distinction. Rather, it’s between how the structuring role to be played by the self-grounder’s narrow notion of grounding differs from that played by the broad notion, and how the similarity-making and causal roles of the anti-Armstrongian’s universals differ from those of mere concepts. Even if we grant that the gap between concepts and universals is larger than that between weak and strict (or, more generally, broad and narrow) grounding, the difference between the structuring role of broad grounding and that of narrow grounding (on the self-grounder’s conception) seems exactly as small (nil) as that between the roles of concepts and the roles of universals on the anti-Armstrongian conception.

The self-grounder’s strategy of switching to Revised Fundamentality is very similar to my imagined anti-Armstrongian’s move: they both weaken the theoretical roles initially assigned to a certain notion, but without explaining how the resulting roles differ from those already filled by other concepts in the vicinity. So, the self-grounder has an as of yet undischarged burden that is very similar to the anti-Armstrongian’s: merely by embracing Revised Fundamentality, she hasn’t given us a revisionary conception of the narrow notion of grounding that plays the structuring role but isn’t irreflexive. There are obvious candidates for playing Revised Fundamentality, but these are the dualists’ broad notions: weak grounding, proper-or-improper grounding, non-strict grounding, and the like. And as we have seen in Sect. 2, these cannot be what the self-grounder has in mind. But then, merely by giving us Revised Fundamentality, the self-grounder hasn’t yet provided us with an adequate revisionary conception of grounding.

Note that this challenge, similarly to the one confronting the anti-Armstrongian about disjunctive universals, is not in principle unanswerable. Unfortunately, I cannot provide a sufficient condition for what would count as an interesting narrow notion of grounding that fails to be irreflexive (if I could come up with one, I could probably also cite a genuine case of self-grounding). However, I can give what strikes me as a plausible necessary condition: self-grounders would need to supply us with a version of the structuring role that their non-irreflexive notion of grounding can play but the broad notions cannot. This would go a long way toward carving out an interesting, revisionary conception of the narrow notion.

Anyone who rejects the irreflexivity assumption owes us a partial characterization of grounding that does justice to the spirit of the structuring role but is still recognizably an account of the narrow notion. It seems to me that advocates of the Self-grounding Thesis have failed to appreciate the severity of this problem; they have never explicitly discussed the theoretical roles grounding is supposed to play, let alone how these roles need to be revised in light of the alleged counterexamples to irreflexivity. I’m skeptical about the availability of such a revision, and until one is offered we have no reason to think that there is a non-irreflexive notion that comes close enough to playing the structuring role assigned to the narrow notion of grounding.

4 Self-grounding and the explanatory role

Let’s turn to the explanatory role. It’s a widely shared assumption that both the explanation relation itself and any explanatory relation deserving of the name are irreflexive. However, possibly because it seems so obvious, we are hard-pressed to find anyone in the general literature on explanation arguing for this claim. One might try to base the irreflexivity of explanation on a plausible connection between explanations and arguments. According to the classic D-N model (Hempel 1965), scientific explanations correspond to sound arguments that cite a law of nature. Likewise, one could maintain that grounding explanations correspond to arguments (deRosset 2013b: 12, Wilsch 2016). This could justify a constraint according to which circular explanations are unacceptable for the same reason circular arguments are. Explanations, as well as arguments, answer ‘Why?’-questions: an explanation provides a reason why its explanandum holds, while an argument provides a reason why its conclusion holds. Plausibly, the reason an explanatory argument gives for its conclusion is the same proposition as the explanans by which the corresponding explanation explains its explanandum. Thus, a putative explanation’s explanans partially explains its explanandum only if that premise of the associated argument that corresponds to the explanans provides some reason for the argument’s conclusion. It seems that circular arguments cannot satisfy this condition: we shouldn’t believe any proposition on the basis of that very proposition; and so, no proposition explains itself. (Of course, p is always a “reason” to believe p in the weak sense that one ought to believe the trivial logical consequences of one’s beliefs. Still, p doesn’t provide a reason to believe p. So, while a circular argument is sound, it cannot function as a rational convincer; and so, it can at best correspond to a completely vacuous explanation, i.e. a non-explanation.Footnote 31)

While the D-N model and argument views of explanation in general have come under criticism, the most common objections to them are powerless against the fairly modest claim that the existence of a sound, non-circular argument is necessary for non-probabilistic (including metaphysical) explanation. The most influential objections to argument views usually focus on the much more ambitious claim that arguments with certain features are also sufficient for explanation in general.Footnote 32 So the ban on non-circular arguments may be a good enough reason to insist on the irreflexivity of explanation even if we don’t subscribe to a general argument view.

There is also a further reason for thinking that explanation is irreflexive. Plausibly, and consistently with the realist view assumed in this paper, there is an epistemic constraint on what can count as an explanation: explanations need to have the potential to increase our overall understanding.Footnote 33 That is, for a statement such as ‘p explains q’ to express a genuine explanation, there should be a possible cognitive state of non-understanding, best expressed by the question ‘Why q?’, and an answer, ‘p’, learning of which replaces this state of non-understanding with a state of understanding. To achieve this goal, explanations have to be informative in the sense that the explanans clause conveys information not provided by the explanandum clause, or at least conveys information in a way not provided by the explanandum clause. Note that this requirement doesn’t mean that the explanans clause conveys information to every audience that the explanandum clause doesn’t convey in the same way, only that it’s capable of doing so in the right circumstances.Footnote 34

Just how weak my informativeness requirement is can be appreciated by considering the wide variety of scientific and metaphysical explanations that satisfy it. If John’s digestion of arsenic causally explains his food poisoning, then learning of his digestion of arsenic can equip us with new information we didn’t have when we asked why he had food poisoning. Similarly, if an action’s failure to maximize utility metaphysically explains the wrongness of that action, then learning of the action’s failure to maximize utility can equip us with information that we didn’t have when we asked why the action was wrong. Even the most trivial cases of logical grounding satisfy the informativeness requirement. Suppose conjunctions are explained by their conjuncts. Even if ‘Grass is green’ and ‘The sky is blue’ cannot equip us with information we didn’t have when we asked why ‘Grass is green and the sky is blue’ was true, at least they convey the same information in a new way: by describing two distinct atomic facts, as opposed to a single molecular fact.Footnote 35

No matter how weak, though, the informativeness constraint is violated by putative cases of self-explanation. This is because in these cases the explanans and the explanandum clause pick out the very same fact, and so appear to be equivalent with respect to the information conveyed. It seems, then, that the informativeness constraint rules out self-explanation. And if that is so, no non-irreflexive notion of grounding can play the explanatory role.Footnote 36

One might object that citing f in an explanation of f does have the potential to give us new information: although f is of course identical to f, that f explains f is something we may well not have known when we asked why f was the case. Couldn’t learning of that increase our understanding?Footnote 37 This objection brings to light an important feature of my formulation of the informativeness constraint. Let’s distinguish between the explanans and the explanatory product of an explanation.Footnote 38 The explanans is simply that which explains the explanandum; the explanatory product is the fact or proposition that the explanans explains the explanandum. I have formulated the informativeness constraint as a thesis about candidate explanantia. By contrast, the proposal at hand concerns explanatory products: it says that self-explanations can be informative if they furnish us with new explanatory products.

Now, I doubt that learning that f explains f could actually increase our understanding. However, I’m happy to grant that there may be some sentence, γ, such that ⌜γ explains γ⌝ conveys information that γ itself doesn’t convey. Yet even if this were so, and even if we granted (implausibly in my view) that such statements could increase understanding, this would do nothing to undermine the independently attractive principle that the explanans clause of a genuine explanation also has to have the potential to increase understanding. Again, think of explanations in terms of ‘Why?’-questions. The question ‘Why p?’ inquires after that which explains p. But that which explains p is simply p’s explanans; it is this explanans, say q, which explains p, not the explanatory product [q explains p]. So, I maintain that unless learning of the explanans itself has the potential to increase one’s understanding, we don’t have a genuine explanation.

An option in logical space I briefly mentioned in Sect. 2 becomes relevant here. As I noted there, some distinguish metaphysical explanation, a notion with epistemological import, from the purely metaphysical notion of grounding. One way to draw this distinction is to say that metaphysical explanation requires that the grounding and the grounded facts appear under the right conceptual guises or modes of presentation. The self-grounder might use this idea to argue that a ban on self-explanation doesn’t automatically rule out self-grounding: perhaps all cases of self-grounding are cases in which the relevant epistemic factors that would be needed for an explanation are not in place.

Here’s a way to cash out this idea. There are informative fact identities. Perhaps the terms flanked by such identities can serve as the explanans and explanandum clauses of the same explanation. For example, to tweak our example from Sect. 2, perhaps ‘S is water’ and ‘Sample S has H and O parts bound in such and such a way’ stand for the same fact, yet the sentence ‘The fact that sample S has H and O parts bound in such and such a way explains the fact that S is water’ is true. Following Ruben (1990: 218–222), call cases like this identity explanations.Footnote 39 It could be argued that each case of self-grounding corresponds to an identity explanation in which the explanans and explanandum clauses don’t convey the same information in the same way. In an attempt to explain ‘S is water’, citing ‘S is water’ would be completely uninformative, but perhaps citing ‘S has H and O parts bound in such and such a way’ would not be, despite the two sentences’ describing the same fact. But then, the self-grounder could argue, all we need for self-grounding is an informative identity explanation in which a fact under a mode of presentation explains the same fact under some other mode of presentation (restrictions might apply to what the relevant modes of presentations have to be like—more on this later).Footnote 40 This way, we can leave room for self-grounding without committing ourselves to the possibility of self-explanation. Let’s state the revised explanatory role in line with this conclusion:

(Revised Explanation) For any sentences χ and γ, if ⌜[χ] grounds [γ] ⌝ is true then so is ⌜[χ] explains [γ]⌝.Footnote 41

Revised Explanation allows for self-grounding, provided that the following condition is satisfied: the substitution instances of χ and γ pick out the same (self-grounding) fact, but they are not intersubstitutable salve veritate with necessarily co-referential expressions. With Revised Explanation, the self-grounder may argue, we have an explanatory role that can be played by a non-irreflexive notion of grounding. For example, perhaps the fact that a statue, S, has a certain mass, is grounded and explained by, and also identical to, the fact that a mereological fusion, F has that mass (because, say, S is F); yet S’s mass doesn’t explain F’s mass. How is that possible? If ‘explains’ creates opaque contexts, then it could happen that even though ‘F’ and ‘S’ have the same referent, we cannot swap them in ‘[F has mass m] grounds [S has mass m]’ without changing the sentence’s truth value. In the present case, for instance, the features of something under a fusion-guise explains the features of that very thing under a statue-guise, but not vice versa.Footnote 42

Revised Explanation implies that all successful counterexamples to irreflexivity feature facts that are presented by the explanans and explanandum clauses of an explanation in different ways. This proposal doesn’t explain how Fine’s, Krämer’s and Correia’s puzzles, which make no assumption about modes of presentation or conceptual guises, could feature a relation that plays the explanatory role of grounding. So, Revised Explanation would be of help only to a certain kind of self-grounder. Never mind: it would already be big news if there were genuine Jenkins-style cases of self-grounding. At this point, however, we should ask: even if identity explanations are possible, why think that any of them is a grounding explanation? After all, identity explanations are familiar, if controversial. But the mere possibility of identity explanations doesn’t show of any particular kind of explanatory relation that that relation can fail to be irreflexive. For example, even if identity explanations are possible, they have the typical characteristics of non-causal explanation: they are synchronic, don’t involve a spatiotemporal trajectory, and (given the necessity of identity) their explanans by itself metaphysically necessitates their explanandum. Thus, their possibility wouldn’t show that causation isn’t irreflexive. Do we have any better reason to think that they show that grounding isn’t?

To show that there can be grounding explanations whose explanans is identical to their explanandum, the self-grounder has to go beyond claiming that self-grounding involves identity explanation. To see this, first note that lots of facts could be described in lower- and higher-level vocabulary (analogously to the H- and O-parts/water example) to yield such an explanation. It is controversial whether all intrinsic macrophysical properties can be identified with the property of having parts that instantiate such and such properties and stand in such and such relations. But we can safely say that at least many can be: we can often replace the ordinary, higher-level description that picks out intrinsic macrophysical properties with a lower-level description of the entity’s parts and their microphysical properties and relations. For example, having a net charge of −2 is plausibly a micro-based property: it is the property of having two more electrons than protons.Footnote 43

Since self-grounders usually write as if they thought that the phenomenon of self-grounding was surprising and rare, the ubiquitous nature of such fact identities should already make us suspect that this is not really what they had in mind. Suppose, however, that the self-grounder does accept this characterization: every informative fact identity of the sort mentioned above is an instance of self-grounding. It should be conceded that this proposal doesn’t necessarily suffer from the problem I raised for modifications to the structuring role. While many facts figure in informative fact identities, one might reasonably (if controversially) deny that all do. For example, perhaps fundamental facts can be perspicuously described only in the language of fundamental physics. In that case, Revised Explanation won’t allow each fact to ground itself. On the other hand, any fact whatsoever weakly/improperly/non-strictly etc. grounds itself. So if there is a problem with Revised Explanation, it’s not that the broad notions of grounding can also play it. There is a good case to be made that they cannot.

However, it’s one thing to say that the role-player of Revised Explanation doesn’t collapse into the dualist notions and another that it’s a revisionary conception of the narrow notion of grounding. Notice that on the present proposal the role grounding plays in metaphysical explanations is very different in the irreflexive and in the reflexive cases. In the irreflexive case, the story is familiar: grounding is the explanatory relation that underlies metaphysical explanations and which accounts for the explanatory directedness between the grounder and the grounded. But in reflexive cases grounding cannot do this kind of work, since it doesn’t on its own introduce any kind of directedness between a fact and itself. For that, we need to switch from facts to facts-under-such-and-such-conceptual-guises, but now what accounts for the explanatory directedness are simply the guises. At this point, it’s hard to see how grounding itself is an explanatory relation in the intended sense: even if [S has H and O parts bound in such and such a way] explains [S is water], that the former fact grounds the latter has nothing to do with this. ‘The fact that S has H and O parts bound in such and such a way explains the fact that S is water’ comes out true simply because its first clause presents the very same fact under a lower-level conceptual guise than its second clause does.

Note that the problem is not that conceptual guises play some role in identity explanations. Perhaps that is also true in some cases of irreflexive grounding. For example, it seems that an explanation of why Samuel Clemens was a male novelist in terms of (i) Samuel Clemens being a novelist and (ii) Mark Twain being male is inferior to an explanation in terms of (i) and (ii*) Samuel Clemens being male. But, one might think, (ii) and (ii*) pick out the same fact under different conceptual guises.Footnote 44 So it might be reasonable to conclude that even in this ordinary irreflexive case, both grounding and the guises do some work in the explanation, in the sense that they both have the potential to increase understanding. Explaining [Clemens was a male novelist] by (i) and (ii*) is superior to explaining it by (i) and (ii) because in the former, our understanding is increased not only by learning of the presence of the grounding relation but also by being presented with the relata under the right conceptual guises.

Now, I don’t dispute that this is a possibility. Still, there is a crucial difference between this case and the water/H2O case: in the latter, the guises do all the explanatory work and underlying explanatory/determinative relations do none of it; that is, in the latter the explanation’s potential to increase our understanding solely derives from the guises it uses. We can verify this for ourselves by comparing a putative case of self-grounding to a standard case of irreflexive grounding, each of which features manifestly unexplanatory guises. In the Clemens/Twain example I just mentioned, it’s plausible to say that although [Twain is a male] is a sub-par partial explanans of [Clemens is a male novelist], it still goes some way toward explaining the explanandum; it still has the potential to increase the understanding of some audiences. By contrast, it doesn’t seem that [S has mass m] does anything to explain [S has mass m]. There is no rational agent whose understanding of [S has mass m] could possibly be increased by hearing the utterance, ‘S has mass m’. To my mind, this makes for a significant difference between identity explanations and even guise-sensitive irreflexive grounding explanations.Footnote 45

It may be helpful to draw here a comparison between grounding and a more traditional notion of ontological reduction that is often invoked in identity explanations.Footnote 46 As van Riel (2013) has recently observed, the relation between identity and reduction is somewhat puzzling: ‘water reduces to H2O’ is true only if ‘water’ and ‘H2O’ are co-referring terms, yet ‘H2O reduces to water’ seems false. So ‘reduces’ creates intensional contexts, and the truth value of ‘reduces’-sentences is sensitive to the conceptual guises under which the putative reduction relata are presented. With varying levels of explicitness, many philosophers subscribe to one version or other of this view (Smart 1959; Crane 2001; van Gulick 2001).

Now, clearly, identity isn’t itself an “explanatory relation”. The whole point of emphasizing the role of conceptual guises in reductive explanation is to show that reductions can showcase the desired explanatory asymmetry despite the fact that identity itself is a symmetric relation. But how can they showcase it? There is little consensus about the details, but a common strategy is to trace the asymmetry to epistemic differences between the reduced and the reduction base. As Crane (2001: 54) notes, metaphysically speaking the reduction relation is just identity, but the process of reducing a phenomenon makes that phenomenon more intelligible. I don’t want to commit myself to any particular way of cashing out this epistemic condition, but I’m sympathetic to van Riel’s recent attempt to at least give some plausible sufficient conditions for it. van Riel (2013: 757–758) suggests that if one term in an identity statement presents its referent under a conceptual guise that specifies the referent’s internal make-up, while the other term doesn’t, then concatenating the latter term, ‘reduces to’, and the former term (in that order) yields a true reduction sentence. No doubt this account could be refined further; what matters is that there are clearly a number of ways to reconcile the explanatory asymmetry of reduction with the symmetry of identity. To put it in a slogan form: a reductive explanation is reductive because the reduced is identical to the reduction base, but it’s an explanation because they occur under conceptual guises that display the right kind of informational asymmetry.Footnote 47

If this is correct, self-grounding is simply the ontological reduction of facts in the sense explained above. Which, of course, naturally raises the question: why think of ontological reduction as a case of grounding? We have seen that irreflexive grounding is very different from ontological reduction: in the former, much of the explanatory work is done by an explanatory relation, while in the latter, all the explanatory work is done by the conceptual guises under which the identity relata fall. These two types of explanation are so different that subsuming them under the same category seems deeply misleading. It seems, then, that Revised Explanation doesn’t help us to a conception of grounding that allows for self-grounding but is still apt to play the explanatory role.

One can of course always decide to use the word ‘grounding’ for the disjunction of (irreflexive) grounding and ontological reduction (or, to guarantee transitivity, the transitive closure of their disjunction). But the orthodox irreflexivist can agree that there are both grounding explanations underwritten by grounding and identity explanations where the explanatory work is done solely by the conceptual guises. She can even introduce a new term, ‘grounding*’, for this broader notion of grounding. The problem is that this broad notion seems like an excellent candidate for playing the explanatory role as specified by Revised Explanation. But then, the self-grounder hasn’t done enough to show that he has a revisionary conception of the narrow notion of grounding. We still have no information about how the explanatory role played by his supposedly revisionary conception of grounding differs from that of grounding*, which also satisfies Revised Explanation.

At this point, you might start suspecting that the foregoing lengthy discussion of Revised Explanation, fact identities, and conceptual guises was all a red herring. You might have this reaction because you might think there is a much simpler way of bringing the Self-grounding Thesis in line with the informativeness constraint: perhaps facts can ground themselves through “grounding loops”. The idea is that while simple cases of a fact directly grounding itself would indeed violate the requirement that explanations be informative, it may still be informative to learn that f 1 grounds f 2, that f 2 grounds f 3… and that f 17 (say) grounds f 1. If grounding is transitive, or if at least this particular instance of it doesn’t violate transitivity (which I will grant for the argument’s sake), then we get the result that f 1 grounds itself. There is nothing wrong with circles as such, so long as the circle is big enough—or so the thought goes.Footnote 48

Temping as this thought may be, it is misguided. My initial case against the explanatoriness of self-grounding made no assumption about the size of the circle that ends with a fact’s grounding itself. As I formulated it, the informativeness constraint demanded that the explanans clause convey information not provided by the explanandum clause, or at least convey information in a way it was not conveyed by the explanandum clause. Obviously, for any fact [χ], χ doesn’t convey any information that χ doesn’t convey in the very same way. Whether there are some other candidate explanans clauses that could do the job is neither here nor there.

The reason the size of a grounding circle might seem relevant to whether it can be explanatory is that the informativeness constraint does nothing to rule out any of the following explanatory hypotheses: (i) that f 1 explains f 2, (ii) that f 2 explains f 3, …, (xvii) that f 17 explains f 1, etc. However, from the fact that the constraint doesn’t rule out any single one of these possibilities it simply doesn’t follow that it doesn’t rule out their conjunction. I’m happy to concede that when we have what looks like a big grounding loop, there are plausibly some adjacent members in it that stand in the explanation relation: this is why we have the intuition that big loops are better than small ones. But this intuition does nothing to show that all such adjacent pairs stand in the explanation relation, and so it doesn’t show that the loop eventually reaches back to that first member.Footnote 49

Where does this leave us? Prima facie, for grounding to play the explanatory role it has to be irreflexive. We have seen that in the case of the structuring role, this prima facie assumption could in principle be defeated, and the analogy with disjunctive universals indicates what could count as a suitable defeater. A version of the structuring role weak enough to allow for violations of irreflexivility but specific enough to carve out a job description different from the one assigned to the broad notions might just do the trick. Similar remarks apply to the explanatory role. Introducing further constraints that drive a wedge between mere identity explanation and self-grounding would go a long way toward establishing that there is a non-irreflexive notion of grounding that is still a version of the narrow notion. Alternatively, explaining how grounding loops are compatible with the informativeness requirement on explanation might help, too. But in the absence of such arguments, we should conclude that the self-grounder has not yet offered a non-irreflexive notion that can play a sufficiently robust version of the explanatory role.

5 Conclusion

My main purpose in this paper has not been to deny there is a legitimate use of the word ‘grounding’ in which it doesn’t pick out an irreflexive notion; on the contrary, I want to suggest that for terminological, technical (etc.) reasons it may be convenient to recognize such a use, analogously to the broad notions of parthood, constitution, realization, and other metaphysical relations. What I want to cast doubt on is that there is a notion that (i) isn’t irreflexive but (ii) plays strong enough versions of the structuring and explanatory roles to still qualify as a notion of grounding. The revised notions I considered are not up to task, and I don’t see better revisions forthcoming.

Even if I turn out to be wrong about this last bit, I take myself to have shown something important. You cannot solve the puzzles of grounding by simply “rejecting” irreflexivity, and you don’t get to give up irreflexivity merely by offering intuitive “counterexamples” to it. If you want to be a self-grounder, you face the very real threat that no matter how you fill in the details, you wind up with a notion that is neither clear nor useful. However, while the challenge is serious it isn’t by its form insurmountable. The analogy with disjunctive universals gives us a reasonably clear idea of what would need to be done to articulate a revisionary conception of the narrow notion of grounding: find sufficiently fine-grained versions of the theoretical roles originally assigned to grounding that allow us to relax the irreflexivity assumption but which don’t coincide with the job description of the broad notions. Either way, realizing that there is a challenge is philosophical progress.

In the absence of a detailed story about how a non-irreflexive notion of grounding could play the core grounding roles, we need to regard this challenge as unanswered. This leaves us with two options: either any existing and forthcoming counterexample to irreflexivity is bound to be illusory, or grounding is unsuitable for the kind of job it has been invoked for and is therefore best abandoned.

Notes

Note that while Barnes (forthcoming) argues for the possibility of symmetric ontological dependence, she (rightly) takes pains to distinguish this relation from grounding. So, she should not be counted as a denier of the irreflexivity of grounding.

Cf. Rosen (2010), Audi (2012a, b), Raven (2012), and Skiles (ms). For a category-neutral notion of grounding, see Rodriguez-Pereyra (2005), Cameron (2008), Schaffer (2009) and Jenkins (2011). Bennett (2011, 2017) and J. Wilson (2014) defend a different view: ‘building’ (for Bennett) or ‘small-g grounding’ (for Wilson) function as placeholders for specific determinative relations.

This is true even of Fine (2010), who is otherwise a proponent of the connective view. On formulating the irreflexivity requirement for the connective ‘because’, see Schnieder (2010, 2015). In his more recent work Fine usually talks about the “non-circularity” of ground, which is very similar to irreflexivity.

Some might be puzzled about how the distinction I draw in Sect. 2 between grounding qua metaphysical explanation and grounding qua the relation underlying metaphysical explanation could be maintained on the connective view. See footnote 28 for details.

Dasgupta (2014a) argues that grounding is an irreducibly many-many relation. In what follows I will ignore this possibility, though I suspect that my main points would go through on this conception, too.

A similar definition is suggested by Fine (2012a), though he officially treats both full and partial grounding as primitives.

This formulation presupposes that grounding is a two-place relation, an assumption that at least one opponent of the irreflexivity of grounding, Jenkins (2011), questions. There are two reasons for this omission. First, while relevantly analogous formulations are available for more-than-two-place construals of grounding, adjudicating between the options would be a tedious detour. Second, so far as I can see the adicity of grounding plays little role in Jenkins’ rationale for self-grounding. The lion’s share of the work is done by the idea that ‘ground’-sentences don’t wear their logical structure on their sleeve and create contexts in which the terms standing for the putative grounding relata are not intersubstitutable salva veritate. I will discuss a proposal along these lines in Sect. 4.

Fine repeats the example with propositions and also with universal instead of existential quantification. I chose to focus on facts because I take grounding to be a relation between facts, and on existential rather than universal facts, because the latter introduce extra complications that are unrelated to the problem at hand.

Schnieder (2015) has recently taken a similar approach to the asymmetry of ‘because’: he argues that properly understood ‘because’ is always asymmetric (and so irreflexive) because its underlying “priority relations” (causation, grounding, etc.) are asymmetric. Schnieder’s approach is similar to mine insofar as he focuses on general methodological considerations rather than particular problem cases. In other regards, it is quite different: on the one hand, he is interested in causal as well as non-causal uses of ‘because’, but on the other hand, he accepts the asymmetry of priority relations as rock bottom. By contrast, I want to give independent reasons for thinking that grounding in the “underlying relation sense”, and not only in the “metaphysical explanation” sense (for more on this distinction, see below), is irreflexive.

In fact, for reasons spelled out in Kovacs (2016), I’m somewhat attracted to this negative conclusion.

Philosophers who argue that “constitution is identity”, for example Noonan (1993), can be understood as thinking that every material object constitutes itself. For broad (identity-permitting) notions of realization and ontological dependence, see Shoemaker (2007: 23) and Thomasson (1999: 26), respectively.

Note that being a broad notion doesn’t imply being a defined or stipulated notion. For largely technical reasons, Fine (2012a, b) accepts weak ground as a primitive and uses it to define strict ground. This is perfectly compatible with weak ground being an artificial extension of the narrow notion, just like (proper-or-improper) parthood can be accepted as a mereological primitive and nonetheless be seen as a broadening of the ordinary notion of (proper) parthood.

DeRosset (2013a) argues that Fine’s notion of weak ground is obscure, but he doesn’t make the same claim about broad notions of grounding in general.

I use the expressions ‘metaphysically prior to’ and ‘more fundamental than’ interchangeably. There are other (perfectly legitimate) notions of metaphysical priority; for instance, Schnieder (2010, 2015) uses the phrase ‘priority relation’ for explanatory relations (such as causation and grounding, where ‘grounding’ stands for the relation underlying metaphysical explanation). Note that some x can be metaphysically prior to some y in my sense without being so in Schnieder’s sense. For example, as Bennett (2017: Ch. 4) points out, a hydrogen molecule in Ithaca is more fundamental than some water in Phoenix, but the existence of the former doesn’t ground or explain the latter (in Bennett’s terminology: the former doesn’t “build” the latter).

In the introduction I said that the paper’s main arguments would go through even if we didn’t reify grounding but instead stuck to a connective view. In the present case this might seem less obvious, since the connective approach is often associated with the “grounding = metaphysical explanation view”. Schaffer (2016: 85–86), for example, has recently complained that this approach is only suitable for grounding qua metaphysical explanation but cannot capture grounding qua the relation that backs metaphysical explanation. I think Schaffer is mistaken about this; in fact, the connective versus relation debate is entirely orthogonal to the explanation versus relation-that-underlies-explanation distinction. For one, we could introduce two different connectives for grounding and metaphysical explanation, say ‘becauseg’ and ‘becausem’, and maintain that the former is transparent while the latter creates opaque contexts. There’s nothing incoherent about this approach to grounding qua the underlying relation; it’s similar to a view of causation suggested by the late Lewis’s (2004: 77) remark that causation by absence would make it difficult to treat causation as a relation. For another, commitment to a relation of metaphysical explanation is cheap in so far as we understand ‘relation’ in the abundant sense. (See Kovacs 2016: 10–11 for this second point, which should be credited to Louis deRosset.).

I would like to thank an anonymous referee for consistently pushing me to be much clearer in the next few paragraphs.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for pressing this objection.

Interestingly, Tahko and Lowe (2015: §3) mention the requirement of non-circularity in defense of the “asymmetry” of explanation. I think they mean to defend only the antisymmetry of explanation, given that they only reject distinct states of affairs mutually explaining each other but explicitly allow for self-explanatory states of affairs. It is also not clear that Tahko and Lowe’s self-explanatory states of affairs are of the objectionable sort. Some of their other remarks indicate that by self-explanation they mean something similar to the dualist notions: an extension of explanation as ordinarily understood. This is further buttressed by their sympathy for the idea that „every object x trivially depends for its identity upon itself” (§4.2, their emphasis).

See, for instance, Salmon (1977/1997).

Schnieder (2015: 138–140) mentions a similar justification for the asymmetry of explanation, but quickly dismisses it on the basis that it presupposes a “speech acts first” approach to explanation. I don’t agree with Schnieder’s assessment here, as I think that some kind of explanation-understanding link is plausible on any reasonable theory of explanation, including realist views. Realism about explanation implies only that the notion of explanation isn’t interest-relative; it doesn’t imply that explanation bears no conceptual ties to psychological notions like understanding and informativeness. See Friedman (1974: 7–8).

See Achinstein (1983: Ch. 3) for a helpful discussion of explanation, understanding, and ‘why’-questions.

Evnine (2008: 73–82) argues that the mental state of believing a conjunction is identical to the mental state of believing its individual conjuncts. I’m not sure if this implies that conjunctions and their conjuncts taken together convey the same information in the same way. But if it did, and Evnine turned out to be correct in identifying the two kinds of mental states, I would deny that conjunctions are explained by their conjuncts.

Cf. also Guigon (2015: 360–361) on this point. What if f 1 is explained by a plurality of facts, f 1 …f n —doesn’t citing f 1 …f n convey information that citing only f 1 doesn’t? Perhaps so, but the informativeness constraint rules out f 1 …f n as the full explanation of f 1 regardless. On the usual way of understanding the relation between partial and full explanation, f 1 …f n can fully explain f 1 only if each of f 1 …f n partially explains f 1 ; but given the informativeness constraint, f 1 cannot partially explain f 1 . Relatedly, one might think that if f 1 …f n explain f 1 , then f 1 ’s ability to explain f 1 in conjunction with f 2 …f n is a new piece of information over and above that provided by just citing f 1 . This is true, but is of little help here: if f 1 is the explanans then it should explain f n itself rather than just facts about it; accordingly, by citing it we should be able to convey new information, not just by citing facts about it. (Thanks to an anonymous referee for raising these issues.).

Thanks for an anonymous referee for pressing this objection, and for helping me clarify my stance on how we should understand the informativeness constraint.

See Ruben (1990: 6–9) for this terminology.

In its more common and less controversial use, ‘identity explanation’ means an explanation in which the explanans is an identity fact. This is not what I mean, and it’s also not what Ruben has in mind. The idea isn’t that the explanans is an identity fact; rather, there is an explanation whose explanans and explanandum clauses pick out the very same fact.

Note that it’s possible to combine the idea that ‘explains’ is not referentially transparent with the view that grounding just is metaphysical explanation. But in that case, there will be no way to drive a wedge between self-explanation and self-grounding. See Rosen (2010) in connection with this: while Rosen doesn’t technically deny that ‘grounds’ is referentially transparent, he accepts an extremely fine-grained, conceptual theory of facts according to which a sample’s being water and the same sample’s being H2O are different facts. He does so precisely to avoid violations of irreflexivity.

It’s not clear how the thesis could be generalized to facts no term in the language names, but the problems I will raise for Revised Explanation are independent from that.

See Kim (1998: 84); cf. Armstrong (1978: Ch. 18). Don’t confuse micro-based properties with microphysical properties and relations. The properties of being an O-atom and being an H-atom, and the relation of being bound in such and such a way, are microphysical. So, the fact [An O-atom and two H-atoms are bound in such and such a way] is presumably a microphysical fact and is not identical to the macrophysical fact [S is water]. By contrast, having O-parts and H-parts bound up in such and such a way is a micro-based property, so the fact [S has as parts O-atoms and H-atom parts that are bound in such and such a way] has a good claim to be identified with [S is water].

I owe this example, and the complication it illuminates, to an anonymous referee.

A referee suggests that by the self-grounder’s lights, grounding (broadly understood) plays an important role in both putative explanations. After all, the fusion has to be identical to the statue for the conceptual guises to do their work. I agree; however, I think this identity plays a merely enabling role in the explanation. It’s a precondition of the guises’ doing their explanatory work, but it doesn’t follow that the identity relation itself enters the explanation in the way grounding does in the irreflexive cases.

I say “more traditional” because while Rosen (2010) also argues that reduction entails grounding, he understands reduction in terms of real definition. This notion is different from the one that has been widely discussed in the philosophy of mind and science literatures and which I also have in mind here.

Of course, there are many competing notions of reduction, and some might imply that the asymmetry between the reduced and the reduction base cannot be established just by the conceptual guises. However, this would only make things worse for the self-grounder: it would imply that the relation between the two isn’t symmetric. But then what we have is not a case of self-grounding, after all.

Dasgupta (2014a: 11) hints that he wouldn’t be hostile to large enough grounding loops, though he doesn’t outright endorse their possibility.

One may wonder if the possibility of causal loops should give us some reason to accept the possibility of grounding loops. A complete answer would require a thorough discussion of the grounding-causation analogy, a topic worthy of a paper in its own right; here, I have to confine myself to a few brief remarks. First, even if self-grounding is conceivable, it doesn’t follow that a non-irreflexive notion could play the grounding roles. I’m willing to say the same thing about causation: if a relation isn’t irreflexive, it cannot play the causation roles. Even many friends of causal loops admit that no event in a causal loop explains itself (cf. Lewis 1976: 148; Hanley 2004: 125; Meyer 2012: 260–261.) Second, the distinction between narrow and broad notions of grounding has no analogue in the causation literature. Since there is no such thing as a well-worked out “broad notion of causation”, revisionists about causation have more wiggle room in weakening the theoretical roles assigned to causation. Perhaps this shows that despite a shared explanatory component, grounding is significantly different from causation and is in certain regards more akin to metaphysical notions like parthood and constitution. Alternatively, it might just show that we have a more nuanced understanding of the formal features of grounding than of those of causation. Either way, a non-irreflexive conception of causation doesn’t face the same obstacles a similar view of grounding does.

References

Achinstein, P. (1983). The nature of explanation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Armstrong, D. (1978). A theory of universals: Universals and scientific realism (Vol. II). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Audi, P. (2012a). A clarification and defense of the notion of grounding. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Audi, P. (2012b). Grounding: Toward a theory of the in-virtue-of relation. Journal of Philosophy, 109, 685–711.

Barnes, E. (forthcoming). Symmetric dependence. In R. Bliss, & G. Priest (Eds.), Reality and its structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bennett, K. (2011). Construction area: No hard hat required. Philosophical Studies, 154, 79–104.

Bennett, K. (2017). Making things up. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bliss, R. (2014). Viciousness and circles of ground. Metaphilosophy, 45, 245–256.

Cameron, R. (2008). Turtles all the way down: Regress, priority and fundamentality. Philosophical Quarterly, 58, 1–14.

Clapp, L. (2001). Disjunctive properties: Multiple realizations. Journal of Philosophy, 98, 111–136.

Correia, F. (2005). Existential dependence and cognate notions. Munich: Philosophia Verlag.

Correia, F. (2010). Grounding and truth-functions. Logique et Analyse, 53, 251–279.

Correia, F. (2013). Metaphysical grounds and essence. In M. Hoeltje, B. Schnieder, & A. Steinberg (Eds.), Varieties of dependence. Munich: Philosophia Verlag.

Correia, F. (2014). Logical grounds. Review of Symbolic Logic, 7, 31–59.

Crane, T. (2001). Elements of mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dasgupta, S. (2014a). On the plurality of grounds. Philosophers’ Imprint, 14(14), 1–28.

Dasgupta, S. (2014b). The possibility of physicalism. Journal of Philosophy, 111, 557–592.

deRosset, L. (2013a). What is weak ground? Essays in Philosophy, 14, 7–18.

deRosset, L. (2013b). Grounding explanations. Philosophers’ Imprint, 13(7), 1–26.

Dorr, C., & Hawthorne, J. (2013). Naturalness. Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, 8, 3–77.

Evnine, S. J. (2008). Epistemic dimensions of personhood. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fine, K. (2001). The question of realism. Philosophers’ Imprint, 1(1), 1–30.

Fine, K. (2010). Some puzzles of ground. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic, 51, 97–118.

Fine, K. (2012a). Guide to ground. In F. Correia, & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fine, K. (2012b). The pure logic of ground. Review of Symbolic Logic, 5, 1–25.

Fine, K. (2015). Unified foundations for essence and ground. Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 1, 296–311.

Friedman, M. (1974). Explanation and scientific understanding. Journal of Philosophy, 71, 5–19.

Guigon, G. (2015). A universe of explanations. Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, 9, 345–375.

Hanley, R. (2004). No end in sight: Causal loops in philosophy, physics and fiction. Synthese, 141, 123–152.

Hempel, C. G. (1965). Aspects of scientific explanation. New York: The Free Press.

Jenkins, C. (2011). Is metaphysical dependence irreflexive? Monist, 94, 267–276.

Kim, J. (1998). Mind in a physical world. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kovacs, D. M. (2016). Grounding and the argument from explanatoriness. Philosophical Studies. doi:10.1007/s11098-016-0818-9.

Krämer, S. (2013). A simpler puzzle of ground. Thought, 2, 85–89.

Lewis, D. (1976). The paradoxes of time travel. American Philosophical Quarterly, 13, 145–152.

Lewis, D. (1983). New work for a theory of universals. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 61, 343–377.

Lewis, D. (2004). Causation as influence. In J. Collins, N. Hall, & L. A. Paul (Eds.), Causation and Counterfactuals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Litland, J. (2013). On some counterexamples to the transitivity of grounding. Essays in Philosophy, 14, 19–32.

Marshall, D. (2015). Intrinsicality and grounding. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 90, 1–19.

Meyer, U. (2012). Explaining causal loops. Analysis, 72, 259–264.

Noonan, H. W. (1993). Constitution is identity. Mind, 102, 133–146.