Abstract

Institutions are crucial for shaping society and its values and behaviors, especially in the context of the global environmental crisis. Institutions can play a significant role in enhancing the adaptive capacity of society to climate change, as emphasized by the IPCC reports. Char is a land-form that is highly vulnerable to climate change and related events. Char is a land-form that is highly vulnerable to climate change and related events. According to the Human Development Report (Assam Human Development Report 2014. Government of Assam, 2014), char dwellers are the poorest and the most vulnerable communities in Assam. This paper aims to understand how the institutions of the char areas of Assam, including both formal and informal institutions can foster the adaptive capacity of the communities residing in these vulnerable locations. To achieve this goal, we apply the adaptive capacity wheel (ACW), a widely accepted approach to determine the quality of institutions in the literature of institutional economics. ACW is a normative economic study, based on value judgments, and we interviewed 49 stakeholders of a total of 16 char villages of Assam. Our study reveals the characteristics and challenges of institutions of the char areas in Assam. It emphasizes the fact that about certain dimensions, like the institutions' capacity to generate resources, support modifications to their structure and pattern, improve the ability to learn, and ensure fairness in the governance system, the char institutions of Assam's various regions require extra attention. These areas are crucial for the people’s resilience to severe climate impacts. In addition to identifying regional variations in institutional quality, our research makes recommendations for institutional enhancements aimed at boosting societal adaptability. It is also argued that the study can be extended to other sensitive areas of the world with similar characteristics to char.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The idea of governance has gained popularity in policy studies as a way to overcome uncertainty in both natural and human systems (Pahl-Wostl 2009; IPCC 2021; Al-Malki and Durugbo 2023). The transition from a traditional government model to a new structure of decision-making that incorporates vertical and horizontal coordination, more participation, flexibility, and decentralization is a crucial component of governance processes (Biermann et al. 2010; Munaretto and Kolstermann 2011; Madni and Anwar 2020; Nguyen et al. 2021). Throughout human history, the social structure, also known as the institution, has evolved to meet various social challenges according to the prevailing culture and philosophy (Gupta and Dellapenna 2009; Fidelman 2019; Dau et al. 2022). The adaptability of a social system or an institution can lessen the possibility of being adversely affected by various extreme events and events caused because of climate change (Siders 2019; Moore 2010; Khan 2020). According to IPCC (2014, p. 1758), adaptive capacity can be defined as the ability of systems, institutions, humans and other organisms to adjust to potential damage, to take advantage of opportunities, or to respond to consequences. To achieve the reduction of possible losses from climate change and related catastrophes, it is imperative to comprehend how current institutions and social structures handle adaptation and mitigation to climate change (Saravade and Weber 2020). The lives and livelihoods of those who live in charFootnote 1 areas are unpredictable and unstable. The char region is harmed by erosion and this region is amongst the most flood-prone regions of Assam, a north-eastern state of India (HDR 2014). Since the char areas are some of the most vulnerable places in Assam, we looked into the char institutions' (a combination of both the formal and informal institutions) potential to lessen vulnerability there. We evaluated institutional quality using the adaptive capacity wheel (ACW) methodology, which was proposed by Gupta et al. (2010) and widely adopted and utilized by a number of studies. In terms of improving the community's ability to adapt to climate change, our study shows that the overall status of the quality of institutions currently in place in Assam's char areas is insufficient. But we have also discovered variations in the same among several char sites. The discussion of the fields where the current system must be carefully considered is included in the study. The study also reflects that the involvement of multiple actors and collaboration of different forms of institutions has the ability to improve the society’s capacity for adaptation, hence lowering its vulnerability to climate change.

Davis and North (1970), who are known as the founders of institutional economics, defined the institution as a set of fundamental political, social, and legal ground rules that govern economic and political activity (rules governing elections, property rights, and the rights of contract are examples of these ground rules). In economics, when we talk about the study of institutions, economists are particularly focused on the institutional arrangement (North and Thomas 1973; Yifu 1987). In this case, an institutional arrangements can be defined as a collection of behavioral norms that control a specific course of behavior and a system of relationships (Yifu 1987). Institutional arrangement can be formalFootnote 2 or informalFootnote 3 and are run by the government or voluntary organization (Yifu 1987; North and Thomas 1973). In our study, we consider these ideas of institution and institutional arrangement as bases for our institutional quality assessment.

Institutions have a significant impact on a region's long-term economic performance (Alonso et al. 2020). By encouraging change and innovation inside the system, institutions can improve society's capacity to deal with a variety of challenging conditions (North and Thomas 1973). Institutional reforms are frequently advocated to improve the relationship between the environment and humans in a society (Barker et al. 2003; Gupta et al. 2010; Laeni et al. 2020). But at the same time, they are also challenging to put into practice in a traditionally conservative society with its institutional structures (Gupta et al. 2010; Munaretto and Kolstermann 2011; Mandi 2019). Using panel data of 122 emerging economies for the years 1996 to 2020, Zhao and Madni (2021) discovered that economic and political reforms significantly contribute to conserving the environment in developing countries. Al-Saidi (2019) examined how interactions between institutions that are evolving quickly and slowly impact sustainable development. He recommended that reforms be adjusted to the regional and indigenous conditions of each nation. However, enhancing governance structures alone won't be enough to increase the ability to adapt to climate change; consideration of the power dynamics that both shape and are shaped by institutions is also vital (Fidelman 2019). A multi-level management model of institutional innovation was presented by Al-Malki and Durugbo (2023) after conducting a thorough assessment of the literature on institutional innovation. They claimed that institutional innovation develops shrewd institutions capable of surviving in a society marked by exponential change. According to Gupta et al. (2010), institutions must be more proactive and forward-thinking in the face of rapid environmental change, such as climate change. They contend that organizations must possess the capacity to adapt to the negative and irreversible effects of environmental change. While the process of natural adaptation may be sufficient for some cultures or institutions, it could not be enough for others. The existing institution or social structure should then be able to recognize the kind of support required, include it, and adjust to the new circumstance (Munaretto and Kolstermann 2011; Sethi et al. 2021). The capacity of social groups to adapt helps reduce the detrimental consequences of climate change as well as their susceptibility (Siders 2019). Thus, when climate change gets worse, it becomes more important to make different social systems like households, communities, and organizations more adaptable (Moore 2010; Fidelman 2021; Al-Malki and Durugbo 2023). This highlights the need for a deeper comprehension of how the current social structure and institutions respond to adaptation and mitigation of climate change (Saravade and Weber 2020). The impacts of institutional complexity affecting adaptation planning in European cities were investigated by Biesbroek et al. (2021). They discovered that institutional complexity might both facilitate and impede planning for adaptation by opening doors for cooperation and innovation but also posing difficulties for coordination and integration. In rural India, institutional variety and adaptive capacity were examined by Karpouzoglou et al. (2020). By giving people access to a variety of resources and knowledge, they demonstrated how institutional diversity can increase adaptive ability. However, it can also lead to conflicts and trade-offs between various actors and interests. A methodology for evaluating institutional adaptability in forest governance was put up by Ojha et al. (2023). They stated that learning, leadership, legitimacy, and leverage are the four characteristics that determine an institution's ability to change. They used case studies from Nepal and India to apply their framework and show how it may be used to determine the advantages and disadvantages of institutions for forest governance.

According to studies (Lebel et al. 2010; Vinke et al. 2017; Saikia and Mahanta, 2023b, e; Saikia and Das, 2024; Laeni et al. 2020), vulnerable populations are particularly susceptible to economic and social effects of hazardous occurrences caused by climate change. Climate and water-related challenges make Asia's coastal regions particularly susceptible (Pillai et al. 2010; PBL 2018). India and Bangladesh share about 54 trans-boundary rivers, which are vital for the livelihood of a large number of riverine communities. However, a number of causes, including climate change, have contributed to a decline in livelihood opportunities for and vulnerability status of these riverine communities throughout time (Sentinel 2022). Char areas are a special type of land-form found in Indian subcontinent in Ganga–Brhamaputra–Meghna (GBM) plains. Adjusting to the vulnerabilities induced by flood and soil erosion, managing a livelihood is not an easy task for the char dwellers who live with the river every day (Lahiri-Dutt 2014; Azam et al. 2019; Ahmed et al. 2021). The mouths of deltas, coastal regions, and wetlands are the closest geographical features to char environments, according to Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta (2013). However, they also note that char and other wetlands differ in several ways. In North-East India, char areas are spread across the Brahmaputra valley of Assam, covering four out of six agro-climatic zonesFootnote 4 of the state (GOA 2002–2003). Due to the fact that char areas are among the most prone to flooding in Assam and are also affected by erosion, the lives and livelihoods of individuals who reside there are the most vulnerable and unpredictable (HDR 2014). Health, educational, and employment options are scarce in Assam's char regions, and their availability is also impacted by floods and other climate-related variables (Kumar and Das 2019; Saikia and Mahanta 2023a).

There are studies available at the national and international levels that explore the function and potential of institutions in lowering community susceptibility to climate threats (Gupta and Dellapenna 2009; Gupta et al. 2010; Munaretto and Kolstermann 2011; Fidelman 2019; Siders 2019; Fernández and Peek 2020; Saravade and Weber 2020; Khan et al. 2020; Laeni et al. 2020; Nguyen et al. 2021; Al-Malki and Durugbo 2023; Huddleston et al. 2023). To the best of our knowledge, there aren't many studies focused on char institutions and their capacity to raise the adaptability and, consequently, social standing of the society residing in char areas, despite the fact that the char lands are vulnerable and the communities residing there are underdeveloped with few opportunities. The same holds true for the char regions of Assam. Therefore the respective study aims to pave a direction on this least explored but essential aspect of the studies on char areas.

The entire article is divided into four sections. Part two of the paper provides a detailed overview of the technique, while Section Three presents the findings and related comments. The paper's conclusion summarizes the key points and suggests future directions for this field of study.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area and sampling design

The island char and riverside char are the first and second categories, respectively, of char areas, according to the Government of Assam (GOA 1983) (Fig. 2). These areas are frequently impacted by a variety of climate-driven natural disasters, with flood being the most prominent one (Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta 2013; Saikia and Mahanta 2023a, c, d, 2024a, b). Flooding has badly devastated nearly all of Assam's char-dominated blocks (Fig. 1) (HDR 2014). In Fig. 1, the flood-affected blocks are shown in dark blue, whereas the Assamese char-dominated blocks are shown in light yellow. Since the dark brown area shows the combination of the two, it is obvious that the water has had a significant impact on the charred areas. Figure 2 depicts how char regions are structured.

Source HDR (2014) (re-constructed)

Char and flood dominated blocks of Assam.

According to the Assam’s char residents' demographic breakdown, Mishing people, a small number of Nepalis, Muslims from Na-Asomia, Rajbanshi caste members, and a few other indigenous groups all live in this area (Khandakar 2016; Hazarika 2018). Due to their lack of access to basic services like healthcare, education, and other facilities, char dwellers are one of Assam's poorest ethnic groups (GOA 2002–2003; HDR 2014).

To understand the adaptability of Assam's char institutions and their distinct characteristics across different char regions of Assam, we have considered one district with char areas from each of the four Agro-Climatic Zones of Assam where char lands are available. The district with the greatest concentration of char population is chosen for the study from each zone. As a result, the North Bank Plain Zone's North-Lakhimpur district, the Middle-Brahmaputra Valley's Morigaon district, the Upper-Brahmaputra Valley's Tinsukia district, and the Lower-Brahmaputra Valley's Dhubri district are taken into consideration. One revenue circle or the development block including char villages is randomly chosen from each chosen district, and four char villages are chosen for the study from each revenue circle. The study is primarily based on the stakeholders’ perception of the institutional quality. Interviews are conducted with different stakeholders from the selected study areas. This includes social actors, such as government representatives and regional leaders of the village, and common villagers (the villagers that may not be holding any such specific position), in each community. For the study, interviews were conducted with two to four stakeholders from each community and a total of 49 stakeholders were interviewed. The study area's location maps are shown in Fig. 3. The Geographic Information Science (GIS) method is used to create the maps. The study locations are indicated on the maps by the red-colored area that is highlighted. Furthermore, by enlarging the map layers, the surveyed villages from each revenue circle in the corresponding districts have been made clearer to see. The readers may easily identify the sandy riverine regions through these magnified figures.

2.2 Method

The application of indicator-based approaches is supported by various studies because it converts theoretical ideas into a set of variables or indicators that operate as an operational depiction of a system's attributes (Birkmann 2006; Khan et al. 2020). The indicators-based index technique often necessitates the following: a framework; a study's nature, objective, and context; the selection of variables and sub-indicators under each component; data collecting; and result aggregation (Binder et al. 2010; Asare-Kyei et al. 2015). The various dimensions of adaptive ability are represented by indices, which are created by combining the coded and combined indicators into a comparable range of values (Khan et al. 2020). To comprehend the adaptable nature of the institutions in the various char regions of Assam, the present study employs an indicator-based case-study research approach. Case-study research is a type of analytical inquiry that enables the contemporary phenomena of an object to be explored in the context of real-world experience (Yin 2014). As an analytical framework under this case-study research design, we have used the framework Adaptive Capacity Wheel (ACW) developed by Gupta et al. (2010). Scholars of institutional studies have used different approaches to study the resiliency and adaptive capacity of institutions to climate extremes. These approaches are such as “Adaptive Capacity Wheel (ACW)” (Gupta et al. 2010), “Adaptation in Collaborative Governance Regimes” (Emerson and Gerlak 2015), “Adaptive Governance and Resilience” (Djalante et al. 2011), “Examining Adaptational Readiness” (Ford and King 2015), “Disaster Resilient Hotel Indicators” (Brown et al. 2018). However, amongst all these methods, the ACW is a widely cited index for measuring institutional adaptive capacity, as shown by Sider (2019) in his systematic review of the literature. In the words of Munaretto and Kolstermann (2011), The adaptive capacity of institutions to climate change is a phenomenon that is very dependent on social and physical contexts. … By comparing multiple case studies, important lessons may be learnt to the benefit of both the cases under study and other regions. Even though ACW was first created to assess institutional capacity for mitigating climate change, it has since been adopted and adjusted in a number of other studies, including those that assess resilient transport (Essex 2015), the hotel sector (Nguyen et al. 2021), water catchment (Grecksch 2015), water governance (Grecksch 2013), and the wine industry (Pickering et al. 2015). We have employed the ACW methodology to investigate institutional quality in boosting society's ability to adapt to climate change due to the broad acceptance of the strategy, criteria, and methodology employed as well as its relevance to our proposed research.

2.2.1 Conceptual idea on adaptive capacity wheel (ACW)

Considering the social-ecological dimension, the concept of adaptive capacity of the institutions is crucial in order to reduce the society’s extent and degree of vulnerability to climatic extremities (IPCC 2001, 2021). According to Gupta et al. (2010), an institution's adaptive capacity results from the institution's inherent nature, which has the capacity to empower social actors for responding to both short- and long-term impacts by encouraging and allowing the society's creative responses both ex ante and ex post or through some planned measures. The adaptive capacity of institution encompasses: (1) the form of institutions, which may be formal or informal; values, customs, and laws; that permit society, including people, groups, and networks, to adapt to climate change and (2) how much actorsFootnote 5 of the institutions are permitted and encouraged to alter their institutional behavior in order to adapt and deal with changing environmental conditions by the institutions.

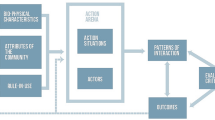

The index-based method has a number of benefits for evaluating an institution’s ability to adapt. First, it enables the identification of various institutional adaptation determinants based on a variety of sources, including the experience of the authors, the topic of interest, expert opinions, or literature reviews (Notenbaert et al. 2012; Bryan et al. 2015). It also makes it possible to utilize indicators to measure the chosen aspects qualitatively or quantitatively. Third, it makes it easier to aggregate the results of the determinants to determine the institution's overall quality (Siders 2019). This paper applies the adaptive capacity wheel (ACW) to examine the adaptability of institutions to climate change and their role in reducing social vulnerability. According to Klostermann et al. (2010) and Munaretto and Kolstermann (2011), the ACW is a normative economic tool that assesses an institution's capacity to adapt to climate change. According to Gupta et al, (2010), The fundamental story line is that institutions that promote adaptive capacity are those institutions that (1) encourage the involvement of a variety of perspectives, actors and solutions; (2) enable social actors to continuously learn and improve their institutions; (3) allow and motivate social actors to adjust their behavior; (4) can mobilize leadership qualities; (5) can mobilize resources for implementing adaptation measures; and (6) support principles of fair governance. Therefore, the wheel is based on six dimensions: variety, room for autonomous change, learning capacity, resources, leadership and fair governance. Amongst these dimensions, variety, room for autonomous change and learning capacity can represent the institution’s potential inherent flexibility. On the other hand, other three dimensions resources, leadership and fair governance are classically accepted dimensions for effective governance process. Improvements to the institution's variety dimension may allow it to respond to many predicted and unforeseen effects of climate change (Nooteboom 2006; Madni 2019). An institution is supposed to be flexible in handling various issues and providing suitable solutions for a variety of difficulties in order to effectively reduce the vulnerability of its people and enhance their adaptive nature (Gupta et al. 2010; Huddleston et al. 2023). Therefore, diversity within the institutions is crucial to accommodate a range of difficulties. This will let the organization handle a variety of issues according to the institutional actors' areas of expertise at various levels and in various sectors (Huq 2016; Fidelman 2017; Khan et al. 2020). Another feature of a good adaptable institution is redundancy. Possessing a backup plan in place in the event that an earlier endeavor fails can improve the institution's capacity to handle unfavorable circumstances (Shakya et al. 2018; Huddleston et al. 2023). Learning capacity is necessary in order to create new responses to climate change impacts. According to Argyris (1990), Gunderson and Holling (2002), Pahl-Wostl et al. (2007), Zhao et al. (2021) and other authors, this involves an institution's capacity for learning to do things better (single-loop-learning) and learning about the processes by which the institution may do better things (double-loop-learning). To facilitate learning capacity in the economy, the institutions need to enhance the mutual trust amongst the different actors (Rydén Sonesson et al. 2021). Simultaneously, it is imperative that an adaptable institution create enough room for its actors as well as the community to voice their worries (Dau et al. 2022). By navigating changes and potential regions of viewpoint adjustments, maintaining records and information about past occurrences helps institutions improve their capacity for learning (Nguyen et al. 2021). In a similar vein, institutional autonomy is crucial since top-down initiatives can appear ineffective due to lengthy processes and a lack of local knowledge (Polsky et al. 2007; Folke et al. 2005; Pelling and High 2005; Zhao and Madni 2021). Consequently, it is required that institutional actors operating at the regional level possess comprehensive knowledge and understanding of the current system (Huddleston et al. 2023). With the autonomy in decision makings and complete information and knowledge about the social system, the institutional actors can more effectively improvise the society's adaptive capability in response to environmental changes (Hurlbert and Gupta 2019; Haddad 2005; Walker et al. 2013). Nonetheless, institutions and institutional actors need to work with a defined plan of action and adhere to it (Shakya et al. 2018; Brown 2013; Gupta et al. 2010; Huq 2016). Resources Mandi and Anwar (2020) and Khan et al. (2020) and leadership (Batukova et al. 2019; Li et al. 2020; Xie and Yang 2021; Huddleston et al 2023) are crucial elements in any institutional change process, even when adjustments are needed to address climate change (Mandi and Anwar 2020). Institutions play a vital role in the creation and development of resources to support society with reduced vulnerability and by increasing society’s adaptive capacity to climate change (Gupta et al. 2010; Mostofi Camare and Lane 2015; Mandi and Anwar 2020). Human resource development can boost labor productivity, skill, and knowledge generation, and intern increase people's potential for adaptation (Morshedlou et al. 2018; Walker et al. 2013). Another key component that contributes significantly to the institutions' growing ability to adapt is access to technology and other financial resources for the construction of infrastructure, such as roads and communications, health care, and education (Salas and Yepes 2020; O'Donnell et al. 2018). More political and legal support from higher authorities is also vital for the various institutions and institutional actors in order to have more human and financial resources (FAO 2018; Huq 2016; Fidelman et al. 2017; Khan et al. 2020; Huddleston et al. 2023). Enhancing an institution's resilience and adaptability requires strong leadership. In a crisis, it is the leaders' duty to act promptly and appropriately (Szpak 2022). As a result, the institution's management needs to have a plan for improving local development and residents' quality of life (Hulbert and Gupta 2017, 2019). Accordingly, institutional leaders of intra- and interregional institutions can improve their institutions' ability to adapt through cooperation and co-management (Nursey-Bray et al. 2018; Sarmah and Mahanta 2023). A transparent and equitable process is followed by the institution (Gupta et al. 2010; Moser et al. 2015; Hurlbert and Gupta 2019). Legitimate policymaking has distinct accountabilities and is sensitive to the society that the institution serves (Barton 2013; Alessa et al. 2016). In addition, the idea of “good governanceFootnote 6” with specific attributes can be illustrated by fair governance (Gupta et al. 2010; Kolstermann et al. 2010; Munaretto and Kolstermann 2011; Fernández and Peek 2020; Dau et al. 2022). In light of the need for institutions to balance efficacy and efficiency in the face of climate change, Gupta et al. (2010) made the conscious decision to embrace “fair governance” as compared to “good governance” (Huddleston et al. 2023). Fair governance guarantees that innovation is not subordinated to efficiency (Hurlbert and Gupta 2019; Grothmann et al. 2013a, b). Table 1 lists the dimensions of ACW, along with the corresponding criteria and definitions for each.

2.2.2 Calculation procedure and presentation

The authors used a mixed methods technique, or what Creswell (2021) refers to as a “Exploratory Sequential Design,” to gather data that could be entered into the adaptive capacity wheel. This procedure is divided into two stages: gathering qualitative data in the first phase, and translating that data into quantitative form in the second phase to further sharpen and highlight the findings of the qualitative phase. For each criterion, information is gathered. Data can be gathered in a variety of methods, including through interviews and observations. Interviews, for instance, could be used to gather information about obstacles associated with implementation as well as informal regulations like norms and values. Creating a list of inquiries can aid in gathering data regarding the criteria. The questionnaire's questions are essentially separated into six categories, one for each dimension. The opening question is followed by the closing question. To elucidate the specifics of the responses, especially in relation to the definitions of the criteria mentioned in Table 1, open-ended questions with the possibility of follow-up questions are utilized. The opening and closing questions sought to identify any crucial elements that may have been overlooked during the debate as well as any overlapping or opposing concepts and forces that may exist inside the institutional framework in a given situation. Similar methods were applied to observations, but the researcher made sure that all pertinent aspects were covered by the dimensions. The questions posed weren't very complicated, and they were written so that anyone could understand them. The questionnaire was prepared in English language but during the interview, the questions were asked in the regional language Assamese. However, some of the respondents (those from other castes or communities) were unable to understand or speak Assamese at some points in the survey. In order to facilitate communication between the two sides in such a scenario, the authors employed a translator, who clarified the inquiries and responses. Without any further interpretation, the stakeholder's responses and observations are recorded in a formal background document. It was taking enough time to carefully record the responses. In order to improve the accuracy and dependability of the data, the responding stakeholder double-checks the recorded replies, which were descriptive in nature, once the survey is finished. The survey with one stakeholder took between one and a half and two hours, with an average of one hour and forty-three minutes.

Furthermore for the data analysis, it is essential that various researchers independently score the background information before discussing any differences in opinion on a particular criterion. This contributes to ensuring both transparency and reliable outcomes (Gupta et al. 2010). As a result, both researchers examined the data, assessed the criteria separately, and then talked about their scores. Through their debate, a final score for the criteria was established. For our study, we consider a total of 21 criterions under the six dimensions of ACW. To reach the second stage of the mixed method technique, that is to quantify the qualitative information, the study uses a five-point Likert scale technique. Following Gupta et al. (2010), each criterion are scored between − 2 to 2. The meaning of the scores and the respective colour to represent the quality is described in Table 2. We have utilized the Cronbach’s alpha reliability test to increase the confidence and overall robustness of the study because the reliability of the Likert scale analysis of qualitative data is frequently questioned. Cronbach's alpha is potentially the most frequently utilized estimator of reliability (Forero 2014). All the statistical analysis are done in the STATA 14 software.

According to Gupta et al. (2010), an equal weighting process can be used to determine the institution's overall value or quality while also allowing for the measurement of each dimension's and each criterion's quality. The value of the criterion for the specific region is measured using the average following a thorough analysis and understanding of the responses against each of the criteria. After determining the value of each criterion associated with a dimension, the dimension value is calculated by averaging the criterion values. By averaging the values of each dimension, the wheel's total value may be calculated. Mathematically it can be shown as follows:

The criterion value is measure using the following formula:

where, Xuv is the average value of the uth criterion of the wth location.

Yvw is the value of uth criterion accessed from the responses by vth respondent from the wth location.

n is the total number of respondent of the respective location.

Once the value of each criterion under the dimensions is measured, the dimension value is measured using the following formula:

Here, Zaw is the dimension value of ath dimension of the wth location.

Xiw represents the value of the ith criterion belonging to ath dimension of wth location.

m is the number of criterion under the dimension a.

After the calculation of the dimension values, the value of ACW of a location w is measured using the simple average of the dimension values.

ACWw is the value of Adaptive Capacity Wheel of wth location. Vw, LCw, RACw, Lw, Rw and Fw are the derived dimension values of variety, learning capacity, room for autonomous change, leadership, resources and fair governance of wth location respectively.

The Wheel is presented with the aid of the color provided by Gupta et al. (2010) after the derivation of the values of each criterion and the associated dimension. The accompanying Fig. 4 and Table 2 display the wheel and color that must be filled in relation to the range of values. The value of the wheel is represented by the inner circle. The six conditions of the institution's adaptive quality are represented by the central circle of the wheel, and the relevant criteria are shown in the outer circle.

Source Gupta et al. (2010)

Adaptive capacity wheel (ACW).

3 Results and discussion

The results of Cronbach’s alpha reliability test are presented in Table 3. According to Nunnally and Bernstein (1994), a reliability coefficient value higher than 0.7 is generally acceptable. In our study, the Scale reliability coefficient value is 0.8334, which is sufficiently high to consider the coding process and the analysis as reliable. Figure 8 in the appendix section provides a snap of result screen of the reliability test performed in STATA 14. In the appendix section's Table 5, the values measured for each dimension and the criteria for each dimension are displayed. Here, we give the ACW value's overall average, which is calculated by averaging the ACW values across all districts. Additionally, we have shown the ACW value for each sample district that was taken into consideration. In accordance with the presentation process, the adaptive capacity of the institutional setup existent in Assam's char regions can be depicted by using the proper hue in various dimensions and ACW criteria. The methodology section includes a discussion of the color fill technique. The adaptive capacity of char institutions of Assam as a whole is presented in Fig. 5 through the ACW methodology.

From the color fill, it is evident that the overall adaptive capacity of the char areas of Assam represents a slightly negative effect. The key findings are summarized in the Table 4. At the same time, it is worth mentioning that the char areas in various parts of Assam are inhabited by members of various communities and differ from one another in terms of their topographical makeup. As a result, it's possible that the ACW composite number does not accurately depict institutional capacity in Assam's various districts. Therefore we have presented the district-wise institutional quality through the ACW approach in Fig. 6. Moreover, for an in-depth understanding of the extent of institutional quality in enhancing the char dwellers’ adaptive capacity across different locations of the state, Fig. 7 may be taken into consideration.

Figure 7 displays the institutional arrangements’ criterion-wise scores and its power to improve the adaptability of several sample districts. The graph shows that practically every institutions’ criterion has to be improved. Most of the criteria give the lowest marks to the Dhubri district, which is followed by the Morigaon district. A better situation at their char institutions is shown by the slightly higher scores in the North-Lakhimpur and Tinsukia districts. It should be emphasized that some of the criteria in all areas need to be seriously improved in order to increase the ability of the char institutions to adapt. Criteria including diversity of solutions, the institution's capacity for single and double loop learning, the provision for providing information to the residents, acting in accordance with the plan, and the provision for providing financial help to the char inhabitants during times of emergency brought on by hazards, all are in need of special treatment in the char institutions of all the regions. The positive attributes the institution has earned in the criteria, such as trust, visionary, equity, and authority, show that people have faith in the prevailing institution and that they support the institutional structure.

Different districts show variations in the criteria under each dimension of the char institutions. A number of social actors and their involvement have been seen in some of the char locations. The institutional actors from the formal institutions, however, are allowed the least amount of liberty to behave in a way that will help them accomplish the intended results practically everywhere in the char areas.

We make an effort to address problems in our community. There are numerous problems in this area, ranging from the environment to infrastructure and development. We constantly work hard to find solutions. We also do our own planning. But we aren't getting full support from the government to accomplish those aims, said the Gaon Burha, the village leader of a village of Tinsukia district that was under survey. Another village stakeholder who is an active villager rather than an institutional actor said that our leaders are constantly with us and they always attempt to solve the problems to the best of their abilities. They do, however, receive the least amount of government assistance, which prevented them from completing all of their plans. Both formal and informal entities cooperate in some situations to achieve better results, such as assisting flood-affected homes, resolving disputes and debates, and allocating newly developed char lands to the needy char residents.

Though they are not receiving the necessary support from the government, the statement previously offered provides an indication of the institutional actors' intention to improve the status of the char regions. The latter comment demonstrates how locals have faith in their social actors. It also shows how cooperative the institutions in the relevant field are. Collaboration between various formal and informal organizations, social actors, and groups is essential for any civilization to advance. Sarvade and Weber (2020) and Dau et al. (2022) claimed in their recent research that strong collaboration can result in a better adaptation in society and an improvement in the status of those who live there.

The institutions of the char regions of the North-Lakhimpur and Tinsukia districts are more diverse than the institutions of the other two in terms of collaboration and the engagement of many social actors in the institutional arrangements and formal and informal institutions. The Mishing Autonomous Council (MAC)Footnote 7 (formal) and Takam Mishing Porin Kebang (TMPK)Footnote 8 (informal) are the regional communal organizations that work with the char inhabitants of these two villages, in addition to other social actors. This may have enhanced these two districts' char institutions' capacity for enhancing adaptation. Additionally, it is discovered that the Mishing community in the two districts has a strong informal institutional pattern. It is therefore plausible to assume that the informal institutional pattern has complemented the formal one to improve these study areas' ability for adaptation. In the district of Morigaon, the informal institution is weak. There is absolutely no informal institutional organization in the Dhubri district. Only one social actor serves as the formal institution's representative in the villages of Dhubri. All those elderly person in our village who used to participate in various decision-making processes and holding the structure of our informal institution are now dead, a stakeholder from a village in the Dhurbri district stated. He further stated that as of right now, our village lacks any informal administration. Only one Gaon Pnchayat (GP) member is available to us, and we only contact him or her when necessary. Interestingly, unlike the other three districts, Dhubri does not have a government-appointed village head person (Gaon Burha), hence the member of the GP is the only official representative of the char regions in that particular place. Being the only representative, it is challenging for me to handle all of the village's difficulties. Additionally, the government does not provide us with enough room or money to carry out development projects in the hamlet. Our responsibilities are limited to starting the aid distribution during emergencies and distributing the schemes to the recipients—remarked a GP participant from a Dhubri district’s survey village. Therefore, it is a question of how a few representations can result in a higher level of adaptability in the dominant institution.

In terms of generating resources for enhanced adaptation, char institutions are incredibly deficient. From the survey, it has been observed that the training sessions on disaster preparedness and livestock management were held in the char areas of the Tinsukia and North-Lakhimpur districts. The MAC usually collaborates with TMPK to organize these training sessions. However, no equivalent activities or arrangements are present in the other two districts. It is crucial for the institutions to plan such a training program in this area to improve the char dwellers' capacity for adapting. Studies and reports like Rani and Maheswari (2015) and CCA RAI (2014, 2023) have supported the training program for increasing the society's and the local population's adaptive capacity to combat the negative effects of climate change. The institutions in every char regions of Assam are also clearly in need of significant attention for aspects like room for autonomous change and learning ability to have institutional reform for boosting char dwellers' adaptive capacity.

4 Conclusion

In this paper, one of the state's most hazardous locations, the char regions of Assam, we have attempted to assess the institutional setup's capacity for adaptation. We highlight the intrinsic qualities of institutions that can enhance society's ability to adapt to climate change and its associated risks using the adaptive capacity wheel (ACW), a normative economic approach. Char areas are the most severely impacted by the climate, and this makes people most vulnerable. Society must become more resilient in order to lessen this susceptibility, and institutions both formal and informal are crucial in boosting a community's potential for adaptation. We may grade the many institutional dimensions and the criteria that fall under each of these categories using ACW. We can determine the areas that require attentive monitoring and policy changes for improvement because it gives us a clear picture of their performance or capacity.

It is crucial to realize that only one type of institution can’t carry out all the tasks and produce development on its own. Collaboration with other institutions or the local institution serving the community is essential. Including various social actor types in the decision-making process can increase an institution's diversity (Munaretto and Kolstermann 2011). It is evident from the study that institutions, their configuration, and their effectiveness in reducing vulnerability vary among different geographic sites. Communities living in this area might also have a different impact on it. Even though top-down techniques are frequently seen to be less effective, institutions must have the ability to organize themselves through local groups in order to have the freedom to make decisions based on their in-depth local knowledge (Munaretto and Kolstermann 2011). As a result, it has also suggested a potential area for additional investigation. Additionally, all of the char regions' institutional arrangements need to be improved in specific dimensions and criteria in order to boost the society's potential for adaptation. To increase the adaptability of the char institutions in Assam, a distinct approach to the institutions of various regions with diverse communities may be advised.

4.1 Scope for the further research

The study is limited to the char areas of only four districts as a representation of the entire char areas of the state. Capturing more of the char regions may provide more insightful and diverse outcomes in compliance to the present study. The paper also offers a wide range of opportunities for additional study about the critical assessment of formal and informal institutions' contributions to the growth of the char community. Our research also demonstrates the potential for investigating the relationship between the community's informal institutional structure and the institution's overall capacity for adaptation in a given place. Additionally, a broad scope has been reflected for a thorough examination into the relationship between the caliber of these institutions and how it has been able to lessen the vulnerability status of the residents of these particular regions of Assam. Char areas share similar characteristics with river deltas, wetlands, and other coastal regions worldwide that are vulnerable to floods and other climate-related natural hazards (Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta 2013; Lahiri-Dutt 2014). Consequently, the present study's approach can also be applied in these regions to comprehend the institutional adaptability of those regions to construct a community that is climate resilient and to shape policy perceptions.

Data availability

The study is based on the primary data and the authors are not willing to share the data publically. However, for the review process, the data can be accessed on request.

Notes

Chars are the new riverine lands and islands created by the continual shifting of the rivers, and emerge from the deposition of sand and silt from upstream. Chars are found along all the major river systems, both lining the banks of rivers and as mid-river islands (DFID 2000).

The judicial and political norms, the economic rules, and the contracts are constraints or rules under formal institutions (North 1990).

Geographically the entire state of Assam is divided into six agro-climatic zones. These six zones are: Upper Brahmaputra Valley, North Bank Plain Zone, Middle Brahmaputra Valley, Lower Brahmaputra Valley, Hill Zone and Barak Valley Zone. Out of these, the first four zones are covered by the Brahmaputra Valley and char areas are found across these four zones.

Good governance is a principle, covering the ideas of decentralization, rule of law, democracy, discretion into it (Botchway 2001).

MAC is an autonomous governing body of Assam.

TMPK is a Mishing students’ union and known as the father organization of MAC.

References

Ahmed Z, Guha GS, Shew AM, Alam GMM (2021) Climate change risk perceptions and agricultural adaptation strategies in vulnerable riverine char islands of Bangladesh. Land Use Policy 103:105287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105287

Alessa L, Kliskey A, Gamble J, Fidel M, Beaujean G, Gosz J (2016) The role of indigenous science and local knowledge in integrated observing systems: moving toward adaptive capacity indices and early warning systems. Sustain Sci 11:91–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0295-7

AlMalki HA, Durugbo CM (2023) Systematic review of institutional innovation literature: towards a multi-level management model. Manag Rev Q 73:731–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00259-8

Alonso JA, Garcimartin C, Kvedaras V (2020) Determinants of institutional quality: an empirical exploration. J Econ Policy Reform 23(2):229–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2020.1719102

Al-Saidi M (2019) Institutional change and sustainable development. In: Leal Filho W (ed) Encyclopedia of sustainability in higher education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63951-2_477-1

Argyris C (1990) Overcoming organizational defences: facilitating organizational learning. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

Asare-Kyei DK, Kloos J, Renaud FG (2015) Multi-scale participatory indicator development approaches for climate change risk assessment in West Africa. Int J Disast Risk Reduct 11:13–34

Azam G, Hossain ME, Bari MA, Mamun M, Doza MB, Islam SMD (2019) Climate change and natural hazards vulnerability of char land (bar land) communities of Bangladesh: application of the Livelihood Vulnerability Index (LVI). Glob Soc Welf 8(1):93–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-019-00148-1

Barton JR (2013) Climate change adaptive capacity in santiago de Chile: creating a governance regime for sustainability planning. Int J Urban Reg Res 37:1916–1933. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12033

Batukova LR, Bezrukikh DV, Senashov SI et al (2019) Modernization and innovation: economic and institutional role. Espacios 40:1–16

Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C (2003) Navigating social–ecological systems: building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge University Press and Assessment, Cambridge

Biermann F, Betsil MM, Vieira SC, Gupt J, Kanie N, Lebel L, Liverman D, Schroeder H, Siebenhuner B (2010) Navigating the anthropocene: The Earth System Governance Project strategy paper. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 2(3):202

Biesbroek R, Termeer C, Klostermann J, Wellstead A (2021) Theorising the complexity of climate change adaptation policy making: How institutional complexity shapes urban adaptation planning in Europe. Environ Sci Policy 116:82–91

Binder CR, Feola G, Steinberger JK (2010) Considering the normative, systemic and procedural dimensions in indicator-based sustainability assessments in agriculture. Environ Impact Assess Rev 30:71–81

Birkmann J (2006) Indicators and criteria for measuring vulnerability: Teoretical bases and requirements. Meas Vulner Nat Hazards Disast Resil Soc 20:55–77

Botchway FN (2001) Good Governance: the old, the new, the principle, and the elements. Florida J Int Law 13(2):159–210

Brown HCP, Smit B, Somorin OA, Sonwa DJ, Ngana F (2013) Institutional perceptions, adaptive capacity and climate change response in a post-confict country: a case study from Central African Republic. Clim Dev 5:206–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2013.812954

Brown NA, Orchiston C, Rovins JE, Feldmann-Jensen S, Johnston D (2018) An integrative framework for investigating disaster resilience within the hotel sector. J Hosp Tour Manag 36(2018):67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.07.004

Bryan BA, Huai J, Connor J, Gao L, King D, Kandulu J, Zhao G (2015) What actually confers adaptive capacity? Insights from agro-climatic vulnerability of Australian wheat. PLoS ONE 10:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117600

Climate Change (2021) The Physical Science Basis Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge University Press

Climate Change Adaptation in Rural Areas of India (CCA-RAI, 2023) https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/16603.htmL. Assessed on 02 July 2023

Climate Change Adaptation in Rural Areas of India (CCA RAI) (2014) Capacity building for climate change adaptation in India. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.8 http://www.climatechange.mp.gov.in/sites/default/files/resources/Human_Capacity_Development.pdf

Creswell JW (2021) A concise introduction to mixed methods research. SAGE Publications. https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=2s0IEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT8&ots=90Z1OREPQb&sig=rtC2p16l-oA8TyZBrKWHiZ1Oxdw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Dau LA, Li J, Lyles MA et al (2022) Informal institutions and the international strategy of MNEs: effects of institutional effectiveness, convergence, and distance. J Int Bus Stud 53:1257–1281. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-022-00543-5

Davis L, North DC (1970) Institutional change and american economic growth: a first step toward a theory of institutional innovation. J Econ Hist 30(1):131–49

Department of Environment, Science and Technology, Government of Himachal Pradesh (n.d.) Climate Change Adaptation in Rural Areas of India (CCA RAI). http://dest.hp.gov.in/?q=climate-change-adaptation-rural-areas-india-cca-rai

Djalante R, Holley C, Thomalla F (2011) Adaptive governance and managing resilience to natural hazards. Int J Disast Risk Sci 2(4):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-011-0015-6

Emerson K, Gerlak A (2015) Adaptation in collaborative governance regimes. Environ Manag 54:768–781

Engle NL, Lemos MC (2010) Unpacking governance: building adaptive capacity to climate change of river basins in Brazil. Glob Environ Chang 20:4–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.07.001

Essex J (2015) How can environmental sustainability thinking make disaster risk reduction better? 2016

FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization (2018) Institutional capacity assessment approach for national adaptation planning in the agriculture sectors. https://www.fao.org/3/I8900EN/i8900en.pdf

Fidelman P (2019) Climate change in the coral triangle enabling institutional adaptive capacity. University of New England. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108502238.017

Fidelman P (2021) Assessing the adaptive capacity of collaborative governance institutions. In R. Djalante & B. Siebenhüner (Eds.), Adaptiveness: Changing Earth System Governance (pp. 69–82). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108782180.006

Fidelman P, Tuyen TV, Nong K, Nursey-Bray M (2017) The institutions-adaptive capacity nexus: insights from coastal resources co-management in Cambodia and Vietnam. Environ Sci Policy 76:103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.06.018

Folke C, Hahn T, Olsson P, Norberg J (2005) Adaptive governance of social–ecological systems. Annu Rev Environ Resour 30(1):441–473

Ford JD, King D (2015) A framework for examining adaptation readiness. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change 20(4):505–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-013-9505-8

Forero CG (2014) Cronbach’s alpha. In: Michalos AC (ed) Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 1357–1359

García Fernández C, Peek D (2020) Smart and sustainable? Positioning adaptation to climate change in the european smart city. Smart Cities 3(2):511–526. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3020027

Government of Assam (GOA) (2002–2003) Socio-economic Survey, (2002–2003). Directorate of Char Areas Development Assam; Dispur, Guwahati-6

Grecksch K (2013) Adaptive capacity and regional water governance in North-Western Germany. Water Pol 15(5):794–815. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2013.124

Grecksch K (2015) Adaptive capacity and water governance in the Keiskamma river catchment, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Water 41:359–368

Grothmann T, Grecksch K, Winges M, Siebenhüner B (2013a) Assessing institutional capacities to adapt to climate change: integrating psychological dimensions in the adaptive capacity wheel. Nat Hazard 13(12):3369–3384. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-13-3369-2013

Grothmann T, Grecksch K, Winges M, Siebenhüner B (2013b) Assessing institutional capacities to adapt to climate change: integrating psychological dimensions in the adaptive capacity wheel. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 13:3369–3384. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-13-3369-2013

Gunderson LH, Holling CS (2002) Panarchy: understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Island Press, Washington

Gupta J, Termeer C, Klostermann J, Meijerink S, Brink M, Jong P, Nooteboom S, Bergsma E (2010) The Adaptive Capacity Wheel: a method to assess the inherent characteristics of institutions to enable the adaptive capacity of society. Environ Sci Policy 13:459–471

Haddad BM (2005) Ranking the adaptive capacity of nations to climate change when socio-political goals are explicit. Glob Environ Chang 15:165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.10.002

Hazarika L (2018) The Misings: an ethnographic profile. J Adv Scholarly Res Allied Educ 15(3):1–5

HDR (2014) Assam Human Development Report 2014. Government of Assam

Huddleston P, Smith TF, White I, Elrick-Barr C (2023) What influences the adaptive capacity of coastal critical infrastructure providers? Urban Clim 48:101416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2023.101416

Huq N (2016) Institutional adaptive capacities to promote ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) to fooding in England. Int J Clim Change Strat Manag 8:212–235. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijccsm-02-2015-0013

Hurlbert M, Gupta J (2017) The adaptive capacity of institutions in Canada, Argentina, and Chile to droughts and floods. Reg Environ Chang 17:865–877. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10113-016-1078-0/TABLES/2

Hurlbert MA, Gupta J (2019) An institutional analysis method for identifying policy instruments facilitating the adaptive governance of drought. Environ Sci Pol 93:221–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.09.017

IPCC (2001) Climate change 2001: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: summary for policymakers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. pp. 1–30

IPCC (2014) Summary for policy makers. In: Field, C.B., Barros, V.R., Dokken, D.J., Mach, K.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., Girma, B., Kissel, E.S., Levy, A.N., MacCracken, S., Mastrandrea, P.R., White, L.L. (Eds.), Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 1–34

Karpouzoglou T, Zulkafli Z, Grainger S, Dewulf A, Buytaert W, Hannah DM (2020) Environmental virtual observatories (EVOs): prospects for knowledge co-creation and resilience in the information age. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 42:40–48

Khan NA, Gao Q, Abid M (2020) Public institutions’ capacities regarding climate change adaptation and risk management support in agriculture: the case of Punjab Province, Pakistan. Sci Rep 10(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71011-z

Khandakar A (2016) Social exclusion of inhabitants of chars: a study of Dhubri District in Assam. Department of Sociology School of Social Sciences, Sikkim University, Gangtok

Klostermann J, Gupta J, Termeer K, Meijerink S, Brink M, Jong P, Nooteboom S, Bergsma E (2010) Applying the Adaptive capacity wheel on the background document of the content analysis’, institutions for climate change: A method to assess the inherent characteristics of institutions to enable the adaptive capacity of society. J. Environ. Sci. Int.

Kumar B, Das D (2019) Livelihood of the char dwellers of Western Assam. Indian J Hum Dev 13(1):90–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973703019839808

Laeni N, Brink M, Busscher T, Ovink H, Arts J (2020) Building local institutional capacities for urban flood adaptation: lessons from the water as leverage program in Semarang, Indonesia. Sustainability 12:10104. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310104

Lahiri-Dutt K, Samanta G (2013) Dancing with the river: people and life on the chars of South Asia. Yale University Press, New Haven

Lahiri-Dutt K (2014) Chars, Islands that float within rivers, Shima. Int J Res Island Cult 8(2):2014

Lebel L, Grothmann T, Siebenhüner B (2010) The role of social learning in adaptiveness: insights from water management. Int Environ Agreements 10:333–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-010-9142-6

Li H, Sheng Y, Yan X (2020) Empirical research on the level of institutional innovation in the development of China’s high-tech industry. IEEE Access 8:115800–115811. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3003932

Lok J (2018) Theorizing the ‘I’ in institutional theory: Moving forward through theoretical fragmentation, not integration. In: Brown AD (ed) The Oxford handbook of identities and organizations. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 1–24

Madni GR, Anwar A (2020) Meditation for institutional quality to combat income inequality through financial development. Int J Fin Econ 2020(26):2766–2775

Madni GR (2019) Probing institutional quality through ethnic diversity, income inequality and public spending. Soc Indic Res 2019(142):581–595

Meyer JW (2010) World society, institutional theories, and the actor. Ann Rev Sociol 36:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102506

Moore FC (2010) “Doing adaptation”: the construction of adaptive capacity and its function in the international climate negotiations. St. Antony’s Int Rev 5(2):66–88. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00138

Morshedlou N, Barker K, Nicholson CD, Sansavini G (2018) Adaptive capacity planning formulation for infrastructure networks. J Infrastruct Syst 24:04018022. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)IS.1943-555X.0000432

Moser C, Stauffacher M, Blumer YB, Scholz RW (2015) From risk to vulnerability: the role of perceived adaptive capacity for the acceptance of contested infrastructure. J Risk Res 18:622–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2014.910687

Mostofi Camare H, Lane DE (2015) Adaptation analysis for environmental change in coastal communities. Socio Econ Plan Sci 51:34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2015.06.003

Munaretto S, Kolstermann JEM (2011) Assessing adaptive capacity of institutions to climate change: a comparative case study of the Dutch Wadden Sea and the Venice Lagoon. Clim Law 2:219–120

Nguyen DN, Esteban M, Motoharu O (2021) Resilience adaptive capacity wheel: challenges for hotel stakeholders in the event of a tsunami during the Tokyo Olympics. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 55:102097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102097

Nooteboom S (2006) Adaptive networks, the governance for sustainable development. Eburon Uitgeverij, Utrecht

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

North DC, Thomas RP (1973) The rise of the western world: a new economic history. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Notenbaert A, Karanja SN, Herrero M, Felisberto M, Moyo S (2012) Derivation of a household-level vulnerability index for empirically testing measures of adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Reg Environ Change 13:459–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-012-0368-4

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH (1994) Psychometric Theory (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

Nursey-Bray M, Fidelman P, Owusu M (2018) Does co-management facilitate adaptive capacity in times of environmental change? Insights from fisheries in Australia. Mar Policy 96:72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.07.016

O’Donnell EC, Lamond JE, Thorne CR (2018) Learning and action Alliance framework to facilitate stakeholder collaboration and social learning in urban flood risk management. Environ Sci Pol 80:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.10.013

Ojha H, Shrestha K, Subedi Y, Shah R, Nuberg I, Heyojoo B, Cedamon E (2023) Assessing the adaptive capacity of forest governance institutions in Nepal and India: a framework and its application. For Policy Econ 125:102403

Pahl-Wostl C (2009) A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob Environ Chang 19(3):354

Pahl-Wostl C, Craps M, Dewulf A, Mostert E, Tabara D, Taillieu T (2007) Social learning and water resources management. Ecol Soc 12(2):5

PBL (2018) Geography of Future water challenges. PBL Netherlands Environmental Agency, The Hague

Pelling M, High C (2005) Understanding adaptation: what social capital offer assessments of adaptive capacity. Glob Environ Chang 15:308–319

Pickering K, Plummer R, Shaw T, Pickering G (2015) Assessing the adaptive capacity of the Ontario wine industry for climate change adaptation. Int J Wine Res 7:13–27

Pillai P, Philips B, Shyamsundar P, Ahmed K, Wang L (2010) Climate risks and adaptation in Asian coastal megacities. The World Bank, Washington

Polsky C, Neff R, Yarnal B (2007) Building comparable global change vulnerability assessments: the vulnerability scoping diagram. Glob Environ Chang 17:472–485

Rani BR, Maheswari KS (2015) Training need assessment on vulnerability and enhancing adaptive capacity of communities on climate change. Int J Agric Sci Res 5(3):61–68

Rydén Sonesson T, Johansson J, Cedergren A (2021) Governance and interdependencies of critical infrastructures: exploring mechanisms for cross-sector resilience. Saf Sci 142:105383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105383

Saikia M, Mahanta R (2023a) Measurement of Vulnerability to Climate Change in Char Areas: A Survey. Ecol. economy soc. INSEE j 6(1):2023. https://doi.org/10.37773/ees.v6i1.679

Saikia M, Mahanta R (2023b) Vulnerability to climate change and its measurement: A survey. Boreal Environ. Res. 28:111–124

Saikia M, Mahanta R (2023c) Does livestock loss affect livelihood? An investigation on char residing mishing community of Assam. Int. Journal of Com. WB 327–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-023-00198-6

Saikia M, Mahanta R (2023d) Riverbank erosion and vulnerability—a study on the char dwellers of Assam, India. Natural Hazards Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nhres.2023.10.007

Saikia M, Mahanta R (2023e) Livestock, livestock loss and livelihood: a note on Mishing char dwellers of Assam. Society Register. 7(4):57–70. https://doi.org/10.14746/sr.2023.7.4.04

Saikia M, Das P (2024) Economic, infrastructural and psychological challenges faced by the students of Assam: A study during COVID-19 pandemic. Society Register 8(1):13–30. https://doi.org/10.14746/sr.2024.8.1.03

Saikia M, Mahanta R (2024a) Can institutions reduce the vulnerability to climate change? A study on the char lands of Assam, India’Geo journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-024-11015-8

Saikia M, Mahanta R (2024b) An application of adjusted livelihood vulnerability index to assess vulnerability to climate change in the char areas of Assam, India. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci 104330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104330

Salas J, Yepes V (2020) Enhancing sustainability and resilience through multi-level infrastructure planning. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030962

Saravade V, Weber O (2020) An institutional pressure and adaptive capacity framework for green bonds: insights from India’s Emerging Green Bond Market. World 1:239–263. https://doi.org/10.3390/world1030018

Sarmah B, Mahanta R (2023) Role of institutions in conservation of wetland along with maintaining sustainable livelihood to its locals—a review. Econ Altern 29:759–775. https://doi.org/10.37075/EA.2023.4.07

Sentinel Digital Desk (2022) Livelihoods along India–Bangladesh Trans-boundary Rivers in Peril. The Sentinel, march, 2022. https://www.sentinelassam.com/topheadlines/livelihoods-along-india-bangladesh-trans-boundary-rivers-in-peril-584771

Sethi P, Bhattacharjee S, Chakrabarti D, Tiwari C (2021) The impact of globalization and financial development on India’s income inequality. J. Policy Model. 43(3):639–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2021.01.002

Shakya KKC, Gupta N, Bull Z, Greene S (2018) Building institutional capacity for enhancing resilience to climate change: an operational framework and insights from practice. Oxford Policy Management, Oxford

Siders AR (2019) Adaptive capacity to climate change: a synthesis of concepts, methods, and findings in a fragmented field’. Wires Clim Change 10:e573. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.573

Szpak A, Modrzyńska J, Piechowiak J (2022) Resilience of Polish cities and their rainwater management policies. Urban Climate 44:101228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2022.101228

Vinke K, Schellnhuber HJ, Coumou D, Geiger T, Glanemann N, Huber V, Knaus M, Kropp J, Kriewald S, Laplante BA (2017) Region at risk: the human dimensions of climate change in Asia and the Pacific. Asian Development Bank, Manila

Lebel L, Manuta J, Garden P (2010) Institutional traps and vulnerability to changes in climate and flood regimes in Thailand. Reg Environ Chang 11:45–58

Voronov M, Weber K (2020) People, actors and the humanizing of institutional theory. J Manag Stud 57(4):775–794. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12559

Walker W, Haasnoot M, Kwakkel J (2013) Adapt or perish: a review of planning approaches for adaptation under deep uncertainty. Sustainability 5:955–979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5030955

Xie J, Yang Y (2021) IoT-based model for intelligent innovation practice system in higher education institutions. J Intell Fuzzy Syst 40:2861–2870. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-189326

Yifu J (1987) An economic theory of institutional change: Induced and imposed change (Center Discussion Paper No. 537). Yale University Economic Growth Center

Yin RK (2014) Case study research: design and methods, 5th edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.30.1.108

Zhao J, Madni GR (2021) The impact of economic and political reforms on environmental performance in developing countries. PLoS ONE 16(10):e0257631. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257631

Zhao J, Madni GR, Anwar MA, Zahra SM (2021) Institutional reforms and their impact on economic growth and investment in developing countries. Sustainability 2021(13):4941. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094941

Acknowledgements

The first author would like to acknowledge Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund for providing the fellowship. Both the authors would also like to acknowledge Gauhati University, Assam, India for giving both academic and logistic support while writing the paper. We would also like to thank all the respondents who have provided their crucial information during the field survey.

Funding

The corresponding author received financial aid in the form of fellowship by the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund during the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collected and Manuscript written by Mrinal Saikia. Manuscript reviewed and corrected by Ratul Mahanta. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Saikia, M., Mahanta, R. Institutions’ adaptability in reducing vulnerability: a study in the char lands of Assam. Environ Syst Decis (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-024-09973-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-024-09973-y