Abstract

Social sustainability has become an increasingly global concern, particularly in urban areas, where ensuring the well-being of urban societies is essential. However, the rapid urbanization of Dhaka city, Bangladesh, has transformed it into a prominent global megacity, accompanied by significant social challenges that impact its social sustainability status. Consequently, this study assessed the present condition of social sustainability in Dhaka city. To accomplish this objective, a quantitative research methodology was employed, utilizing a structured questionnaire survey as the means of data collection. The questionnaire is being held from May 1 to November 2, 2021, to collect as many responses as possible in this study. In this study, a multistage sampling technique was used to select 564 residents of Dhaka city. The results revealed Dhaka city residents have low satisfaction levels regarding social sustainability conditions. This indicates that there is a need for policymakers, urban planners, and implementing agencies to take action to improve the city’s social sustainability. The study’s empirical findings provide valuable evidence for informing socially sustainable planning, policy development, and practical implementation. Moreover, this research supports scholars in developing countries in broadening their perspectives regarding comparable urban social challenges. Furthermore, the study contributes to attaining Sustainable Development Goal 11, titled “ Sustainable cities and communities,” as established by the United Nations. By equipping policymakers with essential insights, the research outcomes aid in promoting inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities and human settlements, not only in Dhaka but also in similar urban settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The world’s urban population is rapidly increasing; cities in developing countries are most at risk from the growing population moving to urban areas. More than 76% of urban people live in developing countries, and the trend is expected to continue in more than 83% of developing countries. In contrast, roughly 16% of people will live in developed areas by 2050 (United Nations, 2019). The UN further noted that rapid urbanization was more likely to occur in developing countries than in developed countries in 2018, but the situation was inverse in 1950. In 1950, developed countries accounted for 60% of the total urban population, while developing countries accounted for 40%, increasing to 50% in 1970. We can see that urbanization is falling sharply in developed countries while rising dramatically in developing countries. Thus, large-scale rural–urban migration, rapid economic growth, and vast industrialization contribute to rapid urbanization and growth. Extreme urban expansion affects sustainable urban development (Marvuglia et al., 2020). Consequently, sustainable urban development is receiving the utmost attention to ensure a socially sustainable city worldwide.

Over the past 35 years, sustainable development has garnered considerable interest in the global political arena. Sustainable urban development stems from the idea of sustainable development, which has also drawn much interest from academics, urban planners, and policymakers globally in recent years (Larimian et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). UN report of the world commission on environment and development: Our common future states that sustainable development depends on three dimensions, namely environment, economics, and social (UN, 1987). The three dimensions of sustainable development are equally vital for sustainable urban development (Baffoe & Mutisya, 2015; Rafieian & Mirzakhalili, 2014).

Even though all three dimensions of the sustainability agenda are essential, social sustainability continues to be neglected in the scholarly literature (Akan & Selam, 2018; Hajirasouli & Kumarasuriyar, 2016; Kumar & Anbanandam, 2019). In contrast, social sustainability is crucial in urban planning, policy, and practice in developed and developing nations (Ali et al., 2019; Rogge et al., 2018). Social sustainability is now commonly linked to discussions of sustainable urban development (Ali et al., 2019). Recently, the notion of socially sustainable urban development has been gaining prominence in the academic literature, with a more considerable emphasis on social issues (Cho et al., 2015; Ring et al., 2021; Shirazi & Keivani, 2019; Wrangsten et al., 2022). Consequently, this idea is receiving more and more attention from governments, government agencies, politicians, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). However, implementing social sustainability for socially sustainable urban development is difficult because of the rising tendency of rapid urbanization, particularly in developing countries.

Rapid urbanization in most developing countries leads to severe social problems within urban areas (Ghalib et al., 2017; Zhang, 2016). The theory of urbanism contends that significant urban social problems result from rapid and uncontrolled urbanization (Wirth, 1938). As a city in a developing country, Dhaka has experienced excessive urban growth over the past few decades. Dhaka is one of the world’s megacities, having experienced huge population expansion due to its rapid urbanization over the past 40 years (Roy et al., 2018). The urban community of Dhaka is battling intensely with social problems, such as standard housing, urban poverty, health services, women’s empowerment, public transportation, sanitation, shelter, illiteracy, slums, corruption, and open spaces, as a result of the city’s rapid urbanization (Barai, 2020; Satu & Chiu, 2019; Yasmin, 2019). These social problems are accountable for guaranteeing social sustainability, which limits the sustainable urban development of city people (Ali et al., 2019; Woodcraft, 2012). Consequently, social sustainability requires proper consideration for socially sustainable urban development, which cannot be overlooked, particularly in developing cities.

Over the past two decades, many social scientists have worked on urban social sustainability. They emphasized specific issues, such as ‘social sustainability in tourism sector’ (Santos, 2023), ‘socially sustainable urban design’ (Timmerman et al., 2019), ‘urban neighborhood’ (Cho et al., 2015; Dave, 2011; Neamtu, 2012; Neilagh & Ghafourian, 2018; Rafieian & Mirzakhalili, 2014; Shirazi & Keivani, 2019; Shrivastava & Singh, 2019; Wang & Shaw, 2018; Woodcraft, 2012), ‘social sustainability of urban regeneration’ (Chan et al., 2019; Glasson & Wood, 2009), and ‘effects of urban form on social sustainability’ (Bramley et al., 2006; Bramley et al., 2009; Bramley & Power, 2009; Landorf, 2011; Dempsey et al., 2012; Kyttä et al., 2016; Ali et al., 2019). As the extensive literature suggests, most authors discuss the role of social sustainability in the urban context as it is essential for creating sustainable cities (Chan et al., 2019; Deviren, 2010; Hemania et al., 2017; Janssen et al., 2023; Weingaertner & Moberg, 2014). Meanwhile, a group of social scientists has focused on the definition and conceptualization of social sustainability as an emerging issue rather than its practical consequences (De Fine Licht & Folland, 2019; Hajirasouli & Kumarasuriyar, 2016; McKenzie, 2004; Vallance et al., 2011). However, none of these studies have focused on measuring the current status of social sustainability to develop socially sustainable urban areas. Therefore, due to the lack of in-depth research conducted in prior studies, it is crucial to place greater emphasis on measuring the current status of social sustainability in cities in developing countries. In order to address the gap in the existing literature, this study aims to measure the current status of social sustainability concerning socially sustainable urban development in Dhaka city. Understanding the current status of social sustainability for all stakeholders in Dhaka city is crucial. Thus, the primary research question for this article is: What is the current status of social sustainability in Dhaka city?

This study is based on empirical evidence and adds new knowledge to the existing body of the literature. As the first attempt of its kind, this study uses a ranking system of social sustainability themes to measure the current status of social sustainability through residents’ satisfaction in Dhaka city. Previous studies have focused on assessing social sustainability, but none have disclosed the rank of social sustainability themes from highest to lowest. Thus, by gathering specific empirical evidence about the status of social sustainability in Dhaka city, this study adds to the body of knowledge by assisting the government, policymakers, urban planners, urban municipalities, and implementing agencies in developing effective plans, formulating policies, and putting those plans into practice for a socially sustainable Dhaka city. Additionally, it helps them determine which social sustainability themes require immediate attention, namely, urban children, the aged, the disabled, and the scavengers, safety, urban poverty and slums improvement, social justice, open space, and transportation availability. Also, this study is essential for cities in developing countries confronting the same urban social problems due to rapid urbanization. Rapid urbanization is a problem not only for the city of Dhaka but also for several other cities, including Kolkata, Delhi, Shanghai, Beijing, Mumbai (Bombay), Kinki M.M.A. (Osaka), Beijing, Al-Qahirah (Cairo), and others (UN, 2014). Ultimately, this study also helps reach the sustainable development goal (SDG)-11, called “ Sustainable Cities and Communities.”

2 Literature review

2.1 Social sustainability and socially sustainable urban development

Social sustainability is an essential aspect of sustainable development that ensures the quality of life for every individual. The concept of social sustainability was central to the sustainability agenda in the late 1990s (Hajirasouli & Kumarasuriyar, 2016). Thus, scholarly literature defines social sustainability more precisely than ever (McGuinn et al., 2020; Partridge, 2014). Sachs (1999) defines social sustainability as human needs such as equitable incomes, access to goods, services, employment, human rights, and the importance of democracy. McKenzie (2004) illustrates, “ Social sustainability is a life-enhancing condition within communities and a process within communities that can achieve that condition.” Ali et al. (2019) describe social sustainability as achieving a better quality of life through the participation and interaction of community members. Hence, social sustainability is a condition of a society where basic human needs are ensured for current generations. Subsequently, it should be confirmed for future generations to create healthy and liveable communities.

In addition, sustainability concerns the resources that should be used carefully so they are sufficient for future generations without reducing the present quality of life. Therefore, social sustainability highlights the management of social resources (Ahmed & McQuaid, 2005; Sarkis et al., 2010). Social resources are any concrete or symbolic item that can be used as an object of exchange among people (Foa & Foa, 1980). Social resources are characterized by both tangible and intangible items (Moriggi, 2020). Social resources include tangible items such as money, information, goods, and services and intangible items such as love/affection and status within society (Webel et al., 2016). The authors also mentioned that social resources continuously improve people’s quality of life. Thus, social sustainability focuses on providing the same or greater access to social resources for future generations as the current generation (Michael & Peacock, 2011). Hence, social resources broadly include fundamental human rights.

Moreover, socially sustainable urban development has attracted increasing global attention. With a greater emphasis on social aspects, the notion of socially sustainable urban development is garnering considerable attention in the academic literature (Cho et al., 2015; Ring et al., 2021; Shirazi & Keivani, 2019; Wrangsten et al., 2022). Enyedi and Kovács (2006) claim that socially sustainable urban development is distinct from sustainable urban development because it places a greater emphasis on social factors. Socially sustainable urban development is accomplished when social aspects such as community involvement, social cohesion, solidarity, fairness, equity, participation, empowerment, and access are ensured in urban areas (Ogunsola, 2016). Therefore, socially sustainable urban development can be defined as a society and an urban condition where social aspects are gaining importance and being ensured in sustainable urban development.

2.2 Theoretical context

Making a sustainable urban requires ensuring social sustainability. Due to the world’s rising urbanization, maintaining sustainable cities is becoming increasingly difficult. Urban social problems resulting from urbanization affect social sustainability (Talan et al., 2020). In 1938, the theory of urbanism focused on how a city has grown due to rapid urbanization, leading to urban social problems. This study outlined how rapid urbanization contributes to social problems that impact social sustainability status. For socially sustainable urban development, this study focuses on the status of social sustainability in Dhaka as an example of a city from a developing country.

The concept of ‘sustainability’ has gradually come to the fore to create a sustainable future. In 1987, the sustainable development concept was formally proposed in a report, Our common future, submitted to the UN world commission on environment and development (WCED). This report defines sustainable development as a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (UN, 1987). The concept of sustainable development is addressed by three dimensions: economic, social, and environmental. Thus, sustainable development is well-known as a sustainable development theory or sustainability theory.

The theory of sustainable development argues that economic, environmental, and social dimensions need to be equally focused to ensure sustainability (Li et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2019; Jia et al., 2022; Yankovskaya et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022, a, b). However, recent literature has illustrated that social sustainability is less focused than economic and environmental dimensions. In addition, this scenario is more unbalanced in developing countries. In other words, social sustainability is less focused on ensuring sustainable urban development in the megacities of developing countries. Like all other megacities, Dhaka also faces an imbalance in social sustainability compared to the two dimensions that hinder socially sustainable urban development. Therefore, this study focuses on the theory of sustainable development, highlighting social sustainability for socially sustainable urban development in Dhaka city.

In sustainable development theory, the social dimension or social sustainability refers to meeting the basic needs of all and expanding opportunities to attain their aspirations for better life without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Social sustainability aims to achieve social requirements that meet all the basic needs of people living nationally or globally for society’s effective and lasting functioning (Talan et al., 2020). So, measuring the current status of the social sustainability of a country or city is essential to ensure sustainable development.

Measuring social sustainability depends on themes and indicators. In 2001, the UN Commission on sustainable development provided social sustainability themes (UN, 2001). Each theme has some indicators that should be identified to measure social sustainability. However, the UN mentioned that using and testing themes and indicators depends on country-specific conditions and basic societal needs. From this perspective, each country has introduced its urban sector policies to ensure sustainability depending on the needs of citizens. Consequently, Bangladesh also set a National urban sector policy in 2011 to ensure sustainability, concentrating on the citizens’ needs.

2.3 Urban social sustainability in Dhaka city, Bangladesh

Dhaka is the capital city of Bangladesh. In recent decades, Dhaka’s urbanization process has resulted in the city’s transformation into a megacity, which is afflicted by the population boom. Rajuk (2015) stated that only 37% of Dhaka’s population growth resulted from natural increase, while 63% was attributable to migration. The rural–urban migration trend in Dhaka is responsible for the rapid urbanization of the city’s population.

Population and density growth began in Dhaka in 1971 (Roy et al., 2019). As a result, Dhaka was ranked ninth out of the top 10 cities in terms of the total number of people living in urban areas in 2018 and is anticipated to be fourth in 2030 (UN, 2018). According to population density per square mile, Dhaka is the world’s first city to construct urban areas, with 41,000 people per square kilometer (Demographia, 2019). Thereby, Dhaka struggles with high population density due to rapid urbanization, which produces social problems and affects social sustainability (Khatun, 2019; Rahman, 2014; Roy et al., 2021).

The sustainability issue in Dhaka city is a significant worry for city planners and government officials (Rajuk, 2015). Due to this, it becomes impossible for city administration officials to guarantee the quality of life for Dhaka’s citizens (Degert et al., 2016; Sarker, 2020). Indeed, constructing a sustainable urban environment involves carefully considering social problems to ensure social sustainability (Ali et al., 2019). For example, in 2019, the ‘Safe cities index’ illustrated the nature of urban safety based on four indicators: digital, infrastructure, health, and personal safety; Dhaka scored 56th out of 60 cities, making it the fifth least safe city in the world (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2019). Furthermore, according to the quality-of-life ranking presented by Numbeo (2021), Dhaka ranks 238th out of 241 cities in terms of cost of living, housing affordability, crime rate, health system, traffic, and pollution. Therefore, measuring the current status of social sustainability through residents’ satisfaction in Dhaka city is a prime issue in building a socially sustainable urban.

3 Research methodology

3.1 Study area and sample selection

Dhaka is the capital city of Bangladesh. This study considers Dhaka city as a study area (geographical location). It is located at 23°42ʹ–23°52ʹ latitude in the north and the 90°22′–90°32ʹ longitude in the east (Roy et al., 2018). The total coverage area of this city is 302.92 square kilometers (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2013). Dhaka has witnessed significant changes in its societal landscape over time. Bangladesh, originally a predominantly rural-based society, has grappled with rural development challenges since its liberation. However, the agricultural revolution’s failure to generate sufficient economic growth has compelled rural inhabitants to seek better opportunities by migrating to Dhaka (Begum, 2007). This influx of rural–urban migration has led to a notable increase in the city’s population, driven by the economic and commercial prospects it offers (Rajuk, 2015). Even today, Dhaka remains the most alluring destination for millions of rural individuals, surpassing other cities in Bangladesh. The uncontrolled and rapid urbanization experienced by Dhaka has transformed it into a megacity, with a staggering population growth observed over the past four decades (Roy et al., 2018). Thus, the study considered Dhaka city as a study area, serving as an example of a developing country. Figure 1 shows the map of Dhaka city and its location in Bangladesh.

As a sampling technique, this study employed a multistage sampling strategy to choose its participants. According to the constitution of Bangladesh, when citizens reach 18, they are eligible to vote in national elections and other significant decision-making events. Therefore, the criteria for this study include voters in Dhaka city who participate in an online survey to provide their viewpoints. In addition, voters’ living experiences enable them to deliver insightful comments on Dhaka’s social sustainability status. The study considers all Dhaka city residents as a population; only the voters are considered a target population. Due to the vast population and the researcher’s cost and time constraints, a manageable sample size is essential because collecting data from each voter is difficult. With the help of G*Power 3.1.9.7, the sample size for this study was computed; the explicated sample size was 287, and the actual power was over 0.80, suggesting a respectable degree of sample power (Chin, 2001). Therefore, the minimum sample size for this study should be 287. Finally, the researcher collected 564 responses from Dhaka residents through an online survey via a structured questionnaire. From May 1 to November 2, 2021, this study placed the questionnaires to collect responses. It took about 6 months to collect as many responses as possible for this study. Table 1 presents the demographic profile of respondents in Dhaka city.

In addition, much scholarly literature mentioned that social sustainability needs for every individual to ensure the quality of life in a city, so this study did not mainly focus on the cluster. To ensure the representation of responses based on occupation, this study collected data from 49.65% of the students, as most age groups are youth in Dhaka city (Rajuk, 2015). This study found 16.49% were involved in private jobs, and 12.59% were engaged in government jobs. Whereas 8.51% were doing business, followed by the teacher (6.74%) and others (6.03%). Furthermore, this study indicates other responses, including poor/low-income people and older people.

4 Research framework

Based on the Commission on sustainable development and National urban sector policy, 2011, this study selected 11 themes to measure social sustainability in the context of Dhaka city, namely (1) Health Facilities (HF), (2) Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment (GEWE), (3) Urban poverty and Slums Improvement (UPSI), (4) Urban children, aged, disabled people, and the scavengers (UCADS), (5) Transportation Availability (TA), (6) Satisfied with Space (SWS), (7) Open Space (OS), (8) Social Capital (SC), (9) Safety (SF), (10) Social Justice (SJ), and (11) Education Facilities (EF) (see Appendix A). Literature has already revealed that Dhaka city’s 11 social sustainability themes are highly significant. Therefore, empirical evidence of social sustainability is crucial in the context of Dhaka city. In this study, 62 indicators were selected under 11 social sustainability themes, namely a five-point Likert scale (i.e., 5-Strongly agree, 4-Agree, 3-Neither agree nor disagree, 2-Disagree, 1-Strongly disagree)Footnote 1 was used in the survey questionnaire where respondents were required to respond to the items. According to Lekjaroen et al. (2016), the mean score was interpreted on a Likert scale as 1.00–1.80 means ‘Strongly disagree,’ 1.81–2.60 means ‘Disagree,’ 2.61–3.40 means ‘Neither agree nor disagree,’ 3.41–4.20 means ‘Agree’ and 4.21–5.00 means ‘Strongly agree.’ Thus, this study used the same interpretation of the mean score on a Likert scale to facilitate the data analysis.

A pre-testing procedure must be conducted to develop a survey questionnaire or confirm the variables’ measurability (Hilton, 2017; Ikart, 2019). This study evaluated the survey questionnaire’s content validity as part of the pre-testing process (see Appendix B). To check the content validity for the individual item (I-CVI) and overall scale (S-CVI) scores, a structural questionnaire was placed on 06 experts, including Directors of urban planning and development, City planners, Consultants, and Program analysts from national and international platforms with four scale degrees of relevance (consistency, representative of concepts, relevance to concepts, and clarity in terms). Based on the experts’ direction, 01 item needs to eliminate due to the I-CVI score, 01 item must be merged with other existing items, and 02 items were suggested to be rearranged (see Appendix B). Finally, based on experts’ comments and relevance ratings, 62 items were selected under 11 variables, as follows in Table 2.

Skewness and kurtosis explicate the normal distribution of a dataset (Hair et al., 2022). Therefore, this study performed a normality test by checking skewness and kurtosis values (see Appendix C). As a result, all the skewness and kurtosis values for each item were within the threshold level ± 2. It means that data were normally distributed for the study. The reliability of the adopted items was measured using Cronbach’s Alpha to examine the quality of the research instruments. Hair et al. (2022) identified that Cronbach’s alpha value should exceed a threshold of 0.70, which reflect reliable, although a threshold of 0.60 is acceptable. The author also stated that a higher threshold of 0.70 indicated higher reliability. According to Table 2, the result of the reliability analysis showed that the overall Cronbach’s Alpha value was 0.951 with the 62 items. Likewise, Cronbach’s Alpha values for all individual variables ranged from 0.899 to 0.957, indicating that all variables obtained greater than 0.70, significantly higher reliability. Hence, all the measuring variables meet the required threshold value of Cronbach’s Alpha which is acceptable, valid, and reliable for this study.

4.1 Data analysis

This study used the social package for social science (SPSS) and MS Excel to analyze data. To check the content validity, this study calculated I-CVI and S-CVI scores. Reliability was measured to assess the internal consistency of items, and Skewness and Kurtosis values were tested to check the assumption of normality for an individual variable. We used frequency distribution to get an overview of respondents’ demographic profiles. Finally, descriptive statistics like Standard deviation (SD) and Weighted average score (WAS) were assessed to measure the current status of social sustainability in Dhaka city.

5 Results

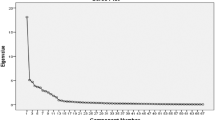

This study used descriptive statistics, i.e., weighted average score, and standard deviation, to measure the status of social sustainability in Dhaka. In Fig. 2, social sustainability themes were ranked 1–11 based on the largest to lowest mean scores. The overall mean of 62 items was 2.619, representing the current status of social sustainability in Dhaka city. The individual mean of items (see Appendix D) and the overall mean of each variable were calculated and ranked, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

The study has developed a framework for measuring social sustainability conditions in Dhaka city. To reflect Dhaka’s current social sustainability status, this study ranked social sustainability themes from highest to lowest mean scores. The highest mean score indicates a high degree of satisfaction, while the lowest mean score indicates a lower level of satisfaction among the residents of Dhaka city. Regarding the current status of social sustainability in Dhaka, the overall mean result was neutral. Still, most of the mean score was disagreeable, as indicated by the respondents’ opinions. Out of the 11 social sustainability themes, respondents showed their neutral position on education facilities, health facilities, social capital, satisfaction with space, gender equality, and women’s empowerment (see Fig. 3). However, most respondents disagreed with the rest of the social sustainability themes in Dhaka city, namely, urban children, the aged, the disabled, and the scavengers, safety, urban poverty and slums improvement, social justice, open space, and transportation availability (see Fig. 3).

Source: Prepared by authors Note: ‘Neutral’ means I have no experience or I have experience, but my judgment is indifferent. ‘Disagree’ means experience and judgment do not favor one over the other

Neutral and disagreeing positions on social sustainability themes based on respondents’ opinions of Dhaka city.

Regarding 11 social sustainability themes, Education facilities (EF) received the highest mean score in Dhaka city’s social sustainability status. Item EF1 (free and compulsory education at the primary level) had the highest mean score. Notably, the mean score of items EF2 (free secondary education for girls), EF3 (specific educational zones for secondary and tertiary education are located according to urban plan), EF4 (arrangement of primary, non-formal, and vocational education with special programs for women), and EF5 (education is expanding through organizing awareness and advocacy programs) was the neutral position. Also, Health facilities (HF) rank second with a mean score of 3.037. The mean value of health facilities showed the Likert scale’s ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ stance. The result indicated that the items HF4 (arrangements for protecting against transmitted diseases threats like aids), HF1 (free primary healthcare service for women and children), and HF2 (hospitals are located in the residential areas) had the highest mean value of 3.121, 3.090, and 3.043, respectively, whereas HF3 (enough rehabilitation facilities for drug addicts) and HF5 (urban social services for healthy urban development) received the lowest mean scores of 2.972 and 2.963, respectively. Social capital (SC) ranks third with a mean score of 2.795. SC1 (relationship with neighbors) got a higher mean value of 2.885, whereas SC8 (plan to change it in the same neighborhood) received a lower mean value of 2.642. The mean score of 08 items was the ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ point of the Likert scale, which means that all the social capital items are indifferent based on the opinion of the Dhaka city residents.

Satisfied with space (SWS) ranks fourth with a mean score of 2.773. The overall mean value of satisfaction with space showed the Likert scale’s ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ stance. The result indicates that the items SWS2 (satisfied with the size of the house) had the highest mean value of 2.819, whereas SWS3 (climatic comfort of my home during summertime), SWS4 (climatic comfort of my house during wintertime), and SWS1 (satisfied with the spatial organization of the house) received the lowest mean scores of 2.789, 2.770, and 2.715, respectively. It means residents’ decisions are neutral in terms of the current condition of satisfaction with the space of Dhaka city. Likewise, Gender equality and women’s empowerment (GEWE) is in the fifth rank, with a mean score of 2.688. The items GEWE7 (scientific compilation of data) and GEWE1 (gender-sensitive urban planning and management strategies) had the highest mean value of 2.934 and 2.716, respectively. The mean value for the remaining gender equality and women’s empowerment items ranges from 2.532 to 2.693. Residents’ opinions on all gender equality and women’s empowerment items were indifferent.

Based on the results of social sustainability status in Dhaka city, Urban children, older people, disabled people, and scavengers (UCADS) rank sixth with a mean value of 2.467. The overall mean value showed the ‘Disagree’ stance on the Likert scale. The mean value of all individual items ranges from 2.293 to 2.463, except for UCADS6 (promote programs to eliminate malnutrition), with a score of 3.046. The result indicated the least satisfaction among the residents of Dhaka city as they believe that all UCADS items are absent to ensure a socially sustainable urban, which needs serious consideration currently. Likewise, Safety (SF) ranks seventh in Dhaka city’s current status of social sustainability. The overall mean value showed the ‘Disagree’ stance on the Likert scale. SF5 (feeling safe in my neighborhood) and SF3 (my house is safe during travel time) had the highest mean values of 2.679 and 2.615, respectively. Whereas the mean value of the remaining items of safety ranged from 2.316 to 2.53, reflecting the lowest satisfaction level among Dhaka city residents. Overall, the current safety status is unsatisfactory, which is expecting close attention from the government, and city management/implementation authorities to ensure the safety of all the residents of Dhaka city.

There were six items to measure the condition of Urban poverty and slums improvement (UPSI), which ranks eighth with a mean value of 2.415. The overall mean value showed the ‘Disagree’ stance on the Likert scale. On the other hand, the item of UPSI5 (equal access to essential urban services) had the highest mean value of 2.865, representing the ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ stance of the Likert scale. The rest of the items ranged from 2.246 to 2.404. The result indicated the lowest satisfaction level among Dhaka city residents regarding urban poverty and slum improvement. Therefore, a significant consideration is required to improve urban poverty and slums in Dhaka. The ninth rank acquired Social justice (SJ) with a mean value of 2.378. The overall mean value showed the ‘Disagree’ stance on the Likert scale. The items SJ1(fair distribution of resources, especially those most in need), SJ2 (equality of rights that ensured for every citizen of Dhaka), SJ3 (fair access for all people to economic resources, services, and rights), and SJ4 (actively participating in communal activities and decision-making that affect their lives) had a mean value of 2.417, 2.300, 2.378, and 2.418, respectively. Residents felt Dhaka had not adequately implemented social justice based on the results. Thus, government, policymakers, city planners, and city management authorities must emphasize ensuring social justice in Dhaka, as social justice is necessary to make a city socially sustainable.

Open space (OS), with a mean value of 2.329, ranks tenth in terms of social sustainability in Dhaka city. The overall mean value showed the ‘Disagree’ stance on the Likert scale. All individual item’s mean values ranged from 2.268 to 2.438, which showed a lower level of satisfaction for getting the facilities from open space in Dhaka city. As every city needs adequate open space for citizens’ healthy liveability, Dhaka’s present open space condition is a dream to us. Moreover, Transport availability (TA) in Dhaka city ranks eleventh with a mean score of 2.304. The overall mean value showed the ‘Disagree’ stance on the Likert scale. The findings revealed that the mean value of all individual items (i.e., reaching to bus stop easily from my home, availability of public transport in Dhaka, satisfaction level of public transportation, and public transport accessibility) ranged from 2.220 to 2.406, which indicated a lower level of satisfaction among the residents of Dhaka city regarding the transport availability. Therefore, paying attention to all available transport items is necessary to make a socially sustainable Dhaka city. Overall, the analysis of the results revealed that social sustainability is unsatisfactory, as its aspects are not accorded sufficient weight to ensure socially sustainable urban development.

6 Discussion

Social sustainability is essential to ensure the sustainability of worldwide urban areas (Lara-Hernandez & Melis, 2018). It is imperative to emphasize that social sustainability must be globally applied, encompassing the resolution of issues on the well-being and quality of living of individuals and communities on a global scale. For instance, ensuring social sustainability is crucial in empowering marginalized groups to enhance their overall quality of life (UN-Habitat, 2020). Also, the UN-Habitat (2020) report emphasized the necessity of employing social sustainability measures to ensure gender equality and provide adequate attention to the needs of migrants, ethnic minorities, and individuals with disabilities. Similarly, social sustainability must encompass five fundamental domains: culture and community, health and well-being, mobility and access, equity, fair trade, and economic outcomes (Property Council of Australia, 2020). Concurrently, the sustainable development goals (SDGs) aim to establish a global social dimension of sustainability, including eradicating poverty, promoting good health and well-being, ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education, achieving gender equality, reducing inequality, and fostering peaceful and inclusive societies (McGuinn et al., 2020). Therefore, the need for social sustainability should be applied globally.

However, since social sustainability is less focused, some studies have empirically measured it but had different purposes than this study. To exemplify, Dogu and Aras (2019) made a scale measuring social sustainability in Güzelyurt in Northern Cyprus. The authors made a measurement scale based on seven variables of social sustainability, such as sense of belonging, social capital, perceived environment, social interactions/security, interaction with space, satisfied with space, voice, and influence. Unfortunately, the social sustainability variables were not satisfactory in Güzelyurt. Moreover, Larimian and Sadeghi (2021) evaluated social sustainability in the urban areas of Dunedin, New Zealand, and found whether design quality influenced social sustainability. They examined the relationships between design quality and overall social sustainability using seven variables: social interaction, safety and security, social equity, social participation, neighborhood satisfaction, sense of place, and housing satisfaction. They found a strong positive correlation between these variables.

Similarly, Ali et al. (2019) assessed how urban form contributed to more significant social sustainability outcomes in Irbid, Jordan. Five features of urban conditions, such as density, land use distribution, building height, type of housing, and access, were used to see how they affected social sustainability variables, such as access to services, open spaces, and parks, availability of transportation, job accessibility, social interaction, safety, residential stability, sense of belonging, and neighborhood as a place to live. Their findings demonstrated that respondents’ satisfaction ranged from moderate to relatively low, and urban form significantly impacted social sustainability. Additionally, an evaluation technique was established by Yu et al. (2017) to gauge the social sustainability of urban housing demolition in Shanghai, China. They measured social sustainability using 22 indicators and revealed that health and safety, social equality, and adherence to the law must be considered critical in urban housing demolition’s social sustainability. Overall, it is evident from the studies mentioned above that social sustainability needs to be implemented to ensure the residents’ quality of life. Hence, the current status of social sustainability should be measured to ensure socially sustainable urban development.

Therefore, the study measured the social sustainability status through the residents’ satisfaction with Dhaka city. Upon analyzing the findings, it became evident that the current state of social sustainability in Dhaka is unsatisfactory, primarily due to the lack of adequate significance given to its various aspects in establishing socially sustainable urban areas. Though, implementing social sustainability is essential for Dhaka city to ensure residents’ quality of life. Moreover, these findings hold significance not only for Dhaka city but also for cities in developing countries, such as Kolkata, Delhi, Shanghai, Beijing, Mumbai, Kinki M.M.A., Beijing, Al-Qahirah, and others, which confront substantial social challenges due to rapid urbanization. Hence, these cities can also consider this study to measure their current level of social sustainability, thereby progressing toward becoming sustainable cities.

7 Conclusions and practical implication

This research endeavor aimed to assess the current status of social sustainability to foster a socially sustainable Dhaka city, which stands as a representative case of a developing nation. The findings obtained from this study shed light on the current condition of social sustainability within Dhaka city through residents’ satisfaction. The results indicate a neutral stance, but many residents submitted an unsatisfactory state for the examined social sustainability themes. Specifically, out of the 11 social sustainability themes scrutinized in this investigation, the following five themes—namely, education facilities, health facilities, social capital, satisfaction with space, gender equality, and women’s empowerment—reside in a neutral position. This implies that the residents of Dhaka city have not entirely embraced nor rejected the prevailing circumstances concerning these aspects.

Conversely, the remaining six social sustainability themes—urban children, the aged, the disabled, and the scavengers, safety, urban poverty, and slums improvement, social justice, open space, and transportation availability—manifest disapproval or disagreement. Again, it means Dhaka city residents are unsatisfied with the current condition. Notably, the current status of social sustainability is not in a good position in Dhaka city. Therefore, based on the citizen’s dissatisfaction with the status of social sustainability in Dhaka, concerned authorities are constructively and strategically guided by this submission of residents in Dhaka with people-based pre-formulating specific solutions to make Dhaka a socially sustainable city.

In this regard, firstly, they should develop their current strategies to consider those social sustainability themes that are not in good condition, such as transport availability, open space, social justice, urban poverty and slum improvement, safety, and urban children, elderly, disabled, and scavengers. However, the remaining social sustainability themes, i.e., education facilities, health facilities, social capital, satisfaction with space, gender equality, and women’s empowerment, need further improvement actions to be taken by keeping the current conditions consistent, which can also help to enhance the current status of social sustainability in Dhaka. Secondly, Bangladesh’s urban planning and policies must be revisited to improve/add to current social sustainability conditions to make Dhaka city socially sustainable for present and future generations. Thirdly, this study can be an example for cities in developing countries where rapid urbanization creates social problems that influence the status of social sustainability. From this point of view, this study opens a further window for those cities facing similar problems that can use this measurement framework to identify the current condition of social sustainability. Fourth, the UN has set the goal for cities and human settlements to be inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable (SDG-11). Thus, the findings of this research draw the attention of city authorities to reach Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)-11, known as “ Sustainable Cities and Communities,” which is possible by ensuring or implementing social sustainability for city dwellers.

8 Scope of future works

Social sustainability is essential to ensure the long-run needs of people in a society. It has become a prominent issue worldwide to ensure socially sustainable urban development. However, the lack of significance of social sustainability, especially in cities in developing countries, increases the need for every stakeholder to know the current status of social sustainability. Therefore, this study reveals the current status of social sustainability that helps the city authorities create insightful thinking to build socially sustainable urban for present and future generations.

However, the limitations of this study are not to be overlooked. First, this study only used quantitative research to answer the research question. Second, this study only used a questionnaire survey to collect data. Third, this study adopted all the literature variables to measure the social sustainability status for socially sustainable urban development in Dhaka city. Nevertheless, from the limitations of this study, there is a scope created for future researchers. For example, a mixed-methods research approach can incorporate different methods to help future researchers investigate various aspects and insightful outcomes of urban social sustainability. Also, there is a chance to use multiple data collection methods such as case studies, interviews, and focus group discussions to explore different aspects of urban social sustainability. Also, index development for social sustainability can be considered based on the city’s culture and basic social needs. Overall, the study might help researchers in developing countries diversify their thinking on social sustainability for socially sustainable urban development.

Data availability

Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Strongly disagree-experience and judgment are strongly not in favor of this aspect, Disagree-experience and judgment are not in favour of one over the other, Neither agree nor disagree-I have no experience or I have experience but my judgment is indifferent, Agree-experience and judgment are in favour of one over the other, and Strongly agree-experience and judgment strongly favour. For details-(Saaty, 1990).

References

Ahmed, A., & McQuaid, R. W. (2005). Entrepreneurship, management, and sustainable development. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 1(1), 6–30.

Akan, M. Ö. A., & Selam, A. A. (2018). Assessment of social sustainability using social society index: A clustering application. European Journal of Sustainable Development. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2018.v7n1p363

Al-Dahmashawi, D., Hassan, D., Sabry, H., & Mahmoud, S. (2014). Incorporating social sustainability themes in the built environment. Journal of American Science, 10(5), 141–151.

Ali, H. H., Al-Betawi, Y. N., & Al-Qudah, H. S. (2019). Effects of urban form on social sustainability –a case study of irbid, jordan. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2019.1590367

Baffoe, G., & Mutisya, E. (2015). Social sustainability: A review of indicators and empirical application. Environmental Management and Sustainable Development. https://doi.org/10.5296/emsd.v4i2.8399

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2013). District statistics 2011 Dhaka. http://203.112.218.65:8008/WebTestApplication/userfiles/Image/District%20Statistics/Dhaka.pdf

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2014). Population and housing census, urban area report. http://203.112.218.65:8008/WebTestApplication/userfiles/Image/National%20Reports/Population%20%20Housing%20Census%202011.pdf

Barai, M. K. (2020). Conclusion Bangladesh’s development—challenges to sustainability and the way forward. In Munim Kumar Barai (Ed.), Bangladesh’s Economic and Social Progress From a Basket Case to a Development Model. Singapore: Springer.

Begum, A. (2007). Urban housing as an issue of redistribution through planning? The case of Dhaka city. Social Policy & Administration, 41(4), 410–418.

Bramley, G., Dempsey, N., Power, S., & Brown, C. (2006). What is ‘social sustainability’, and how do our existing urban forms perform in nurturing it. Sustainable Communities and Green Futures’ Conference, Bartlett School of Planning, University College London, London., http://www.city-form.org/uk/pdfs/Pubs_Bramleyetal06.pdf

Bramley, G., Dempsey, N., Power, S., Brown, C., & Watkins, D. (2009). Social sustainability and urban form: Evidence from five british cities. Environment and Planning a: Economy and Space, 41(9), 2125–2142. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4184

Bramley, G., & Power, S. (2009). Urban form and social sustainability: The role of density and housing type. Environment and Planning b: Planning and Design, 36(1), 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1068/b33129

Chan, H. H., Hu, T.-S., & Fan, P. (2019). Social sustainability of urban regeneration led by industrial land redevelopment in taiwan. European Planning Studies, 27(7), 1245–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1577803

Chin, W. W. (2001). Pls-graph user’s guide. (CT Bauer College of Business, University of Houston, USA Issue.

Cho, I. S., Heng, C.-K., & Trivic, Z. (2015). Re-framing urban space: Urban design for emerging hybrid and high-density conditions. New York: Routledge.

Committee on Urban Local Governments. (2011). National urban sector policy, 2011 (draft) http://fpd-bd.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/National_Urban_Sector_Policy_2011_Bangladesh_Draft.pdf

Cuthill, M. (2010). Strengthening the ‘social’ in sustainable development: Developing a conceptual framework for social sustainability in a rapid urban growth region in australia. Sustainable Development, 18(6), 362–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.397

Dave, S. (2011). Neighbourhood density and social sustainability in cities of developing countries. Sustainable Development, 19(3), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.433

De Fine Licht, K., & Folland, A. (2019). Defining “ social sustainability” : Towards a sustainable solution to the conceptual confusion. Journal of Applied Ethics, 13(2), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.5324/eip.v13i2.2913

Degert, I., Parikh, P., & Kabir, R. (2016). Sustainability assessment of a slum upgrading intervention in bangladesh. Cities, 56, 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.03.002

Demographia. (2019). Demographia world urban areas (built up urban areas or world agglomerations) 15th annual edition ,april 2019. http://www.demographia.com/db-worldua.pdf

Dempsey, N., Brown, C., & Bramley, G. (2012). The key to sustainable urban development in uk cities? The influence of density on social sustainability. Progress in Planning, 77(3), 89–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2012.01.001

Deviren, A. S. (2010). Social sustainability in urban areas: Communities, connectivity and the urban fabric edited by Tony Manzi, Karen Lucas, Tiny Lloyd Jones and Judith Allen, London and Washington DC Earthscan. Urban Research & Practice, 3(3), 341–343.

Dogu, F. U., & Aras, L. (2019). Measuring social ssustainability with the developed mcsa model: Guzelyurt case. Sustainability, 11(9), 2503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092503

Enyedi, G., & Kovács, Z. (2006). Social changes and social sustainability in historical urban centres: The case of central europe. Centre for Regional Studies of Hungarian Academy of Sciences. https://books.google.com.my/books?id=NxLbPAAACAAJ

Foa, E. B., & Foa, U. G. (1980). Resource Theory. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-3087-5_4

Ghalib, A., Qadir, A., & Ahmad, S. R. (2017). Evaluation of developmental progress in some cities of punjab, pakistan, using urban sustainability indicators. Sustainability, 9(8), 1473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081473

Glasson, J., & Wood, G. (2009). Urban regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 27(4), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.3152/146155109X480358

Hair, J. F., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Black, W. C. (2022). Multivariate data analysis. United Kingdom: Cengage Learning. https://books.google.com.my/books?id=PONXEAAAQBAJ

Hajirasouli, A., & Kumarasuriyar, A. (2016). The social dimention of sustainability: Towards some definitions and analysis. Journal of Social Science for Policy Implications, 4(2), 23–34.

Hemania, S., Das, A. K., & Chowdhury, A. (2017). Influence of urban forms on social sustainability: A case of guwahati, assam. Urban Design International, 22(2), 168–194. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-016-0012-x

Hilton, C. E. (2017). The importance of pretesting questionnaires: A field research example of cognitive pretesting the exercise referral quality of life scale (er-qls). International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2015.1091640

Ikart, E. M. (2019). Survey questionnaire survey pretesting method: An evaluation of survey questionnaire via expert reviews technique. Asian Journal of Social Science Studies, 4(2), 1.

Janssen, C., Daamen, T. A., & Verheul, W. J. (2023). Governing capabilities, not places–how to understand social sustainability implementation in urban development. Urban Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231179554

Jia, J. R., Anser, M. K., Peng, M. Y. P., Yousaf, S. U., Hyder, S., Zaman, K., & Bin Nordin, M. S. (2022). Economic determinants of national carbon emissions: Perspectives from 119 countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677x.2022.2081589

Khatun, F. ( 2019). Dhaka: A sustainable city? The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/op-ed/politics/dhaka-sustainable-city-139009

Kumar, A., & Anbanandam, R. (2019). Development of social sustainability index for freight transportation system. Journal of Cleaner Production, 210, 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.353

Kyttä, M., Broberg, A., Haybatollahi, M., & Schmidt-Thomé, K. (2016). Urban happiness: Context-sensitive study of the social sustainability of urban settings. Environment and Planning b: Planning and Design, 43(1), 34–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813515600121

Landorf, C. (2011). Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 17(5), 463–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.563788

Lara-Hernandez, J. A., & Melis, A. (2018). Understanding the temporary appropriation in relationship to social sustainability. Sustainable Cities and Society, 39, 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.03.004

Larimian, T., Freeman, C., Palaiologou, F., & Sadeghi, N. (2020). Urban social sustainability at the neighbourhood scale: Measurement and the impact of physical and personal factors. Local Environment, 25(10), 747–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2020.1829575

Larimian, T., & Sadeghi, A. (2021). Measuring urban social sustainability: Scale development and validation. Environment and Planning b: Urban Analytics and City Science, 48(4), 621–637.

Lekjaroen, K., Ponganantayotin, R., Charoenrat, A., Funilkul, S., Supasitthimethee, U., & Triyason, T. (2016). IoT Planting: Watering system using mobile application for the elderly. In 2016 international computer science and engineering conference (ICSEC) (pp. 1–6). IEEE.

Li, Y. J., Zhao, X. K., Shi, D., & Li, X. (2014). Governance of sustainable supply chains in the fast fashion industry. European Management Journal, 32(5), 823–836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2014.03.001

Ma, S. Q., Dai, J., & Wen, H. D. (2019). The influence of trade openness on the level of human capital in china: On the basis of environmental regulation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 225, 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.238

Marvuglia, A., Havinga, L., Heidrich, O., Fonseca, J., Gaitani, N., & Reckien, D. (2020). Advances and challenges in assessing urban sustainability: An advanced bibliometric review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 124, 109788.

McGuinn, J., Fries-Tersch, E., Jones, M., Crepaldi, C., Masso, M., Kadarik, I., Lodovici, M. S., Drufuca, S., Gancheva, M., & Geny, B. (2020). Social sustainability: Concepts and benchmarks. European Parliament. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1337271/social-sustainability/1944961/

McKenzie, S. (2004). Social sustainability: Towards some definitions. https://www.unisa.edu.au/siteassets/episerver-6-files/documents/eass/hri/working-papers/wp27.pdf

Michael, Y., & Peacock, C. J. (2011). Social sustainability: A comparison of case studies in uk, USA and australia. 17th Pacific Rim Real Estate Society Conference, Gold Coast,

Moriggi, A. (2020). Exploring enabling resources for place-based social entrepreneurship: A participatory study of green care practices in finland. Sustainability Science, 15(2), 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00738-0

Munira, S., & San Santoso, D. (2017). Examining public perception over outcome indicators of sustainable urban transport in dhaka city. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 5(2), 169–178.

Neamtu, B. (2012). Measuring the social sustainability of urban communities: The role of local authorities. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 37E, 112–127.

Neilagh, Z. M., & Ghafourian, M. (2018). Evaluation of social sustainability in residential neighborhoods. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 7(1), 209–217.

Numbeo. (2021). Current quality of life index. Retrieved 14.07.2021 from https://www.numbeo.com/quality-of-life/rankings_current.jsp

ODPM. (2003). Sustainable communities: Building for the future. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20060502112859/http://www.odpm.gov.uk/index.asp?id=1139873

Ogunsola, S. A. (2016). Social sustainability: Guidelines for urban development and practice in Abuja City. Nottingham Trent University (United Kingdom).

Partridge, E. (2014). Social sustainability Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 6178–6186). Netherlands: Springer.

Property Council of Australia. (2020). A common language for social sustainability. https://universaldesignaustralia.net.au/common-language-social-sustainability/

Rafieian, M., & Mirzakhalili, M. (2014). Evaluation of social sustainability in urban neighbourhoods of karaj city. International Journal of Architectural Engineering & Urban Planning, 24(2), 122–130.

Rahman, H. Z. (2014). Urbanization in bangladesh: Challenges and priorities. Bangladesh Econ. Forum,

Rajuk. (2015). Dhaka structure plan 2016–2035 http://www.rajukdhaka.gov.bd/rajuk/image/slideshow/1.%20Draft%20Dhaka%20Structure%20Plan%20Report%202016-2035(Full%20%20Volume).pdf

Ring, Z., Damyanovic, D., & Reinwald, F. (2021). Green and open space factor vienna: A steering and evaluation tool for urban green infrastructure. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 62, 127131.

Rogge, N., Theesfeld, I., & Strassner, C. (2018). Social sustainability through social interaction—a national survey on community gardens in germany. Sustainability, 10(4), 1085.

Roy, S., Sowgat, T., Ahmed, M. U., Islam, S. T., Anjum, N., Mondal, J., & Rahman, M. M. (2018). Bangladesh: National urban policies and city profiles for dhaka and khulna. http://www.centreforsustainablecities.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Research-Report-Bangladesh-National-Urban-Policies-and-City-Profiles-for-Dhaka-and-Khulna.pdf

Roy, S., Sowgat, T., Islam, S. T., & Anjum, N. (2021). Sustainability challenges for sprawling dhaka. Environment and Urbanization Asia, 12(1Suppl), S59–S84.

Roy, S., Sowgat, T., & Mondal, J. (2019). City profile: Dhaka, bangladesh. Environment and Urbanization Asia, 10(2), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975425319859126

Saaty, T. L. (1990). How to make a decision: The analytic hierarchy process. European Journal of Operational Research, 48(1), 9–26.

Sachs, I. (1999). Social sustainability and whole development: Exploring the dimensions of sustainable development. Zed Books.

Santos, E. (2023). From neglect to progress: Assessing social sustainability and decent work in the tourism sector. Sustainability, 15(13), 10329. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310329

Sarker, P. (2020). Analyzing urban sprawl and sustainable development in dhaka, bangladesh. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development. https://doi.org/10.7176/JESD/11-6-02

Sarkis, J., Helms, M. M., & Hervani, A. A. (2010). Reverse logistics and social sustainability. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 17(6), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.220

Satu, S. A., & Chiu, R. L. (2019). Livability in dense residential neighbourhoods of dhaka. Housing Studies, 34(3), 538–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1364711

Schieman, S. (2005). Residential stability and the social impact of neighborhood disadvantage: A study of gender-and race-contingent effects. Social Forces, 83(3), 1031–1064. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2005.0045

Shirazi, M. R., & Keivani, R. (2019). The triad of social sustainability: Defining and measuring social sustainability of urban neighbourhoods. Urban Research & Practice, 12(4), 448–471.

Shrivastava, V., & Singh, J. (2019). Social sustainability of residential neighbourhood: A conceptual exploration. International Journal of Emerging Technologies, 10(2), 427–434.

Talan, A., Tyagi, R. D., & Surampalli, R. Y. (2020). Sustainability: fundamentals and applications. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119434016.ch9

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2019). Safe cities index 2019. https://safecities.economist.com/safe-cities-index-2019/

Timmerman, R., Marshall, S., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Towards socially sustainable urban design: Analysing acto r-area relations linking micro-morphology and micro-democracy. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 14(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.2495/SDP-V14-N1-20-30

UN-Habitat. (2020). The new urban agenda. (HS/035/20E). https://unhabitat.org/the-new-urban-agenda-illustrated

United Nations. (1987). Report of the world commission on environment and development: “ Our common future” . https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/42/427&Lang=E

United Nations. (2001). Indicators of sustainable development: Guidelines and methodologies. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/dsd/resources/res_publsdt_ind.shtml

United Nations. (2014). World urbanization prospects,the 2014 revision. https://population.un.org/wup/publications/files/wup2014-report.pdf

United Nations. (2018). The world’s cities in 2018. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/the_worlds_cities_in_2018_data_booklet.pdf

United Nations. (2019). World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision. (ST/ESA/SER.A/420). https://population.un.org/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2018-Report.pdf

Vallance, S., Perkins, H. C., & Dixon, J. E. (2011). What is social sustainability? A Clarification of Concepts. Geoforum, 42(3), 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.01.002

Wang, M. H., Ho, Y. S., & Fu, H. Z. (2019). Global performance and development on sustainable city based on natural science and social science research: A bibliometric analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 666, 1245–1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.139

Wang, Y., & Shaw, D. (2018). The complexity of high-density neighbourhood development in china: Intensification, deregulation and social sustainability challenges. Sustainable Cities and Society, 43, 578–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.08.024

Webel, A. R., Sattar, A., Schreiner, N., & Phillips, J. C. (2016). Social resources, health promotion behavior, and quality of life in adults living with hiv. Applied Nursing Research, 30, 204–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2015.08.001

Weingaertner, C., & Moberg, Å. (2014). Exploring social sustainability: Learning from perspectives on urban development and companies and products. Sustainable Development, 22(2), 122–133.

Wirth, L. (1938). Urbanism as a way of life. American Journal of Sociology, 44, 33–24.

Woodcraft, S. (2012). Social sustainability and new communities: Moving from concept to practice in the uk. Procedia–Social and Behavioral Sciences, 68, 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.204

Wrangsten, C., Ferlander, S., & Borgström, S. (2022). Feminist urban living labs and social sustainability: Lessons from sweden. Urban Transformations, 4(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42854-022-00034-8

Yankovskaya, V. V., Mustafin, T. A., Endovitsky, D. A., & Krivosheev, A. V. (2022). Corporate social responsibility as an alternative approach to financial risk management: Advantages for sustainable development. Risks, 10(5), 18.

Yasmin, F. (2019). Identification of the existing social problems and proposing a sustainable social business model: Bangladesh perspective. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 11(9), 1–81.

Yildiz, S., Kivrak, S., & Arslan, G. (2019). Contribution of built environment design elements to the sustainability of urban renewal projects: Model proposal. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 145(1), 10.

Yu, T., Shen, G. Q. P., Shi, Q., Zheng, H. W., Wang, G., & Xu, K. X. (2017). Evaluating social sustainability of urban housing demolition in shanghai, china. Journal of Cleaner Production, 153(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.005

Zhang, X. Q. (2016). The trends, promises and challenges of urbanisation in the world. Habitat International, 54, 241–252.

Zhang, X. Y., Cao, Y. H., Tang, M. F., Yu, E. Y., Zhang, Y. Q., & Wu, G. (2022). Evaluation of a chongqing industrial zone transformation based on sustainable development. Sustainability, 14(9), 13.

Zhang, Y. N., Wang, Y., & Wei, J. H. (2022). Evaluation of sustainable development of an agricultural economy based on the dpsir model. Journal of Sensors, 2022, 14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2591275

Zhang, Z. G. (2022). Evolution paths of green economy modes and their trend of hypercycle economy. Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment, 20(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjpre.2022.03.001

Funding

This research is under Ph.D. work, there is no funder or financial sponsor in the entire research process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study’s research objectives, questionnaire, and methodology were approved by the Universiti Malaya Research Ethics Committee (UMREC) (Reference Number: UM.TNC2/UMREC-1018).

Informed consent

All participants in this study were informed about the purpose of the research and how the data will be used. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Table

3.

Appendix B

Table

4.

Appendix C

Table

5.

Appendix D

Table

6.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Razia, S., Abu Bakar Ah, S.H. The hidden story of megacities: revealing social sustainability status through residents’ satisfaction in Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Environ Dev Sustain 26, 24381–24413 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03648-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03648-5