Abstract

Post-conflict countries (PCC) guide their priorities toward restoration of socioeconomic conditions and relegate sustainability objectives to the background. With the aim to provide insights for the current discussion on rural environmental sustainability in today’s post-conflict Colombia, we analyzed the environmental dynamics of seven PCC. We found that (1) deforestation and land use conflicts were frequent impacts in both conflict and post-conflict scenarios, that (2) return of displaced population, the infectiveness of land use planning, and the dependence on the primary sector were frequent drivers of environmental change; and that (3) natural resources extraction tends to be intensified in post-conflict period. We discuss these findings in light of the current environmental problems of Colombia and the post-conflict environmental challenges. We conclude that in order to ensure environmental sustainability in post-conflict scenario, Colombia should act on structural aspects that go beyond the environmental objectives proposed in the peace agreement between the government and FARC: strengthening environmental institutions, integrating long-term environmental objectives across all sectors, and deintensifying the dependence of the economy in the extractive sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Post-conflict countries (PCC) are those who have suffered an armed conflict and that have entered a process that involves the achievement of peace milestones far beyond the ceasefire (Brown et al. 2012; Ugarriza 2013). Peace milestones in PCC include cessation of hostilities and violence; signing of political/peace agreements; demobilization, disarmament, and reintegration; refugee repatriation; establishing a functioning state; achieving reconciliation and societal integration and economic recovery (Brown and Langer 2012, 13). The achievement of such peace milestones brings benefits to the population, institutions, the formal economy, and territory (cf. Guerra and Plata 2005; Quaynor 2012; Appel and Loyle 2012). However, a post-conflict scenario may also involve negative environmental impacts in rural areas, because States often rely on the use of natural resources for peace building (Evans 2004; Lujala and Rustad 2012).

The negative environmental impacts in PCC have been widely documented (UNEP 2000, 2007a, b, 2011; Rustad and Binningsbo 2012). In PCC, natural resource management differs during peacetime. During post-conflict process, the State’s priorities focus on socioeconomic recovery, peacekeeping, and poverty reduction (Niño and Devia 2015), while natural resource management and environmental sustainability objectives are pushed to the foreground (Bruch et al. 2009; Beevers 2012). Moreover, PCC tends to face social capital degradation, poverty, and low levels of governance (Ansoms and McKay 2010; Dulal et al. 2011; Rondinelli 2008), which also threatens environmental sustainability. In some PCC, ecosystems’ conservation has been affected by the expansion of agricultural production and forest exploitation in natural protected areas (Ijang and Cleto 2013), while soils overexploitation for agricultural production has led to loss of soil fertility, soil erosion, and deforestation (Katunga and Muhigwa 2014).

After more than five decades of armed conflict, the Colombian government has signed a peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC: Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia). Colombia is one of the most megadiverse countries in the world, and it currently faces environmental problems that compromise rural environmental sustainability. These problems include (1) extensive cattle farming which has been contributing to land degradation, deforestation, and greenhouse gas emissions; (2) the environmental impacts of poorly regulated extractive industries; (3) climate change vulnerability; (4) poor environmental integration to the national policy framework; and (5) wide disparities in income, landholdings, and access to ecosystem services (OCDE 2014; Suarez and Calderon 2015). This context will pose several challenges to the achievement of environmental sustainability in rural Colombia in a post-conflict scenario.

There are many examples of countries which have shown varying dynamics of environmental transformation in post-conflict scenarios (Evans 2004; Lujala and Rustad 2012). Tracing the diverse drivers of environmental change and their impacts, could provide some insights of the environmental challenges that PCC countries such as Colombia may face.

In this context, this article aims to analyze the dynamics of environmental sustainability in PCC, with the aim to provide insights for the current discussion on environmental sustainability of rural areas in a post-conflict Colombia. The specific objectives are to: (1) identify environmental impacts associated with periods of conflict and post-conflict; (2) identify drivers of environmental change in post-conflict scenarios; and (3) analyze the relationship between natural resource extraction and post-conflict scenarios.

2 Colombia: an armed conflict in a megadiverse territory

Colombia’s rural population has historically endured many events that have affected their well-being. The armed conflict, drug trafficking, landmines, and disputes over control of the territory, have affected the livelihoods and well-being of the rural population (Boron et al. 2016). Colombian rural population has endured armed confrontations, massacres, and forced displacements (Ibáñez and Vélez 2008). About 6 million hectares of land was abandoned because of conflict. In this period, the displaced population reached 3.6 million people, 60% of which were rural population (UNDP 2011). Colombia is among the top countries with the highest number of displaced population (UNDP 2011).

The armed conflict has brought challenges for environmental sustainability in Colombia. For over more than five decades, the armed confrontation has intensively developed in a context of high biodiversity and natural resources (Hanson et al. 2009; Boron et al. 2016). Colombia has 20.1% (23 million ha) of its territory under the figure of natural protected areas (PNN 2016) and is considered a megadiverse country that hosts an important part of global biodiversity (Arbeláez-Cortés 2013). Colombian armed conflict and drug trafficking have put at risk two of the most biodiverse ecosystems worldwide: the Amazon Rainforest and the Choco region (Rincón-Ruiz et al. 2016; Hanson et al. 2009). The Sierra Nevada de Santa Martha, recognized as the world’s most irreplaceable nature reserve (Le Saout et al. 2013), has been considerably affected by illicit crops and the armed conflict (Fjeldså et al. 2005).

The Colombian armed conflict has generated positive and negative environmental impacts. Positive impacts are associated with ecosystem conservation due to conflict restrictions (e.g., landmines or prohibitions regarding land access) that have excluded some areas for productive development (Dávalos 2001; Álvarez 2003). However, some authors argue that the negative environmental impacts of the conflict are widespread because coca crops (Erytrhoxylum coca) and illegal mining have generated deforestation and land transformation in areas such as the northern Andes and the southern Chocó (Álvarez 2003; Dávalos et al. 2011; ILPI 2014). It is estimated that a coca hectare requires the deforestation of one or two hectares (Rincón-Ruiz and Kallis 2013; Transnational Institute 2004). Moreover, environmental impacts have also been induced by the Colombian and US government’s efforts to reduce illegal coca plantations. Aerial fumigation with glyphosate—a broad-spectrum systemic herbicide and crop desiccant—has impulsed natural forest deforestation and the expansion of illicit crops in the Caribbean and Pacific region (Rincón-Ruiz and Kallis 2013). Aerial fumigation with glyphosate has also caused soil fertility loss, water pollution, and human health diseases.

3 Methods

Seven countries were selected to analyze environmental sustainability within post-conflict scenarios: Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burundi, El Salvador, Liberia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone. The countries were selected on the basis of the following three criteria: (1) A peace agreement has been reached; (2) the armed confrontations have ceased; and (3) information related to environmental impacts during conflict and post-conflict periods was available.Footnote 1 PCC countries were selected using the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (2015), which identifies the configuration of international armed conflicts, its scale, and current status. We reviewed literature in Google Scholar, Web of Science, and SCOPUS. We constructed matrixes in which for each country we register the reported literature on environmental impacts during conflict and post-conflict scenarios (objective 1) and the main drivers of change during the post-conflict scenario (objective 2).

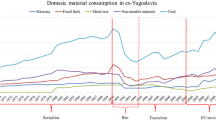

The relationship between natural resource extraction and post-conflict scenarios (objective 3) was analyzed through material flow accounting, which quantifies the use of natural resources by modern societies (Behrens et al. 2007). This approach has been known as industrial metabolism (Ayres 1994) or social metabolism (Fischer-Kowalski and Amann 2001). We use data provided by the Global Material Flows Database (WU 2014) regarding the total domestic extraction of materials between 1980 and 2013 for the PPC and for Colombia. Total domestic extraction includes: (1) fossil fuels (e.g., coal, oil, gas, and peat); (2) biomass (e.g., agriculture, forestry, and fisheries); (3) industrial and construction minerals; and iv) ores. Total domestic extraction included: (a) the used domestic extraction, which consists of materials that acquires value within the economic system (i.e., are consumed or processed) and (2) the unused domestic extraction which refers to materials that are not used by the economic system (e.g., waste of mining or biomass extraction). We compared the median growth rates of total domestic extraction for the periods before and after the peace agreement in PCC countries. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine whether there were significant differences between these two medians.

4 Results

The analyzed PCC countries are located in the regions of Latin America (El Salvador), Africa (Angola, Burundi, Liberia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone), and Europe (Bosnia and Herzegovina). The causes of these conflicts are diverse and include political, social, economic, ethnic, and religious causes. Table 1 presents a summary of the conflicts in the PCC countries and the years when peace agreement was reached. The economic, social, and environmental characteristics of PCC and Colombia are diverse (Table 2).

4.1 Environmental impacts in conflict and post-conflict periods

Deforestation was a frequent negative environmental impact during the armed conflicts (i.e., Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burundi, El Salvador, Liberia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone). For instance, in Liberia between 1990 and 2000, deforestation was up to 76,000 hectares/year (FAO 2005). Land use conflicts were also evidenced in Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and El Salvador. Biodiversity loss and water resource affectation were also negative impacts of armed conflicts. In Sierra Leone for example, the Heritiera utilis tree was extinguished from the West Africa forest reserve and African elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis) declined in the Gola Forest during conflict (Lebbie 2002; Lindsell et al. 2011). Some positive environmental impacts were evidenced during armed conflicts such as forest cover growth in Angola, El Salvador, Sierra Leone, mainly due to land access restrictions (Table 3).

Deforestation processes in armed conflict were an outcome of two main causes. The first one was related to pressure exerted by refugees, displaced people, and massive migrations of people who had previously been scattered across the landscape (Ordway 2015; US Forest Service 2006; REMA 2009). The second one was that forest resources became a readily source of income to fuel warfare (Global Witness 2013; McCandless and Christie 2006). Other environmental impacts were the abandonment of land and land tenure conflicts due to displacement processes (Cain 2013) and land degradation due to landmines (REC 2000).

In the post-conflict scenario, the most frequent environmental impact was deforestation which was evidenced in 5 of the 6 analyzed countries (Table 4). However, a marginal forest growth was evidenced in El Salvador. In Angola, forest area decrease has been reported (Schneibel et al. 2016), while in Rwanda the forest cover loss is up to 64% (REMA 2009). In Sierra Leone, there has also been forest cover loss during the post-conflict scenario (Tänzler 2013). In El Salvador, a significant impact was the expansion of agricultural production in areas with unfit and poor-quality soil (i.e., Salvador). Water resources were also affected in Rwanda and Sierra Leone.

4.2 Drivers of environmental change in post-conflict countries

The drivers of environmental change in PCC are presented in Table 5. A common driver was ‘ineffective land use planning’ (4 countries), which affected land distribution and access and generated pressure over ecosystems (Maconachie 2008; UNEP 2011). Another important driver was the ‘return of displaced population’ through refugee camp installations (UNEP 2011) and the return of farming communities (Leite 2015), which exert pressure on local governments to make fast decisions (cf. Cain 2013). ‘Demand for land for agricultural production’ generated pressures over land and forests. The ‘dependence on the primary sector’ through the promotion of forest industries, charcoal production, and mining was also a driver of environmental change (REMA 2009; Forest Industries 2011; Brown et al. 2012). In turn, ‘unsustainable agricultural practices’ were related to soil and forest overexploitation (Cain 2013; Brown et al. 2012). In the analyzed countries, the environmental dimension was not integrated (or only tangentially) to the peace agreements.

4.3 Dynamics of natural resource extraction in post-conflict countries

Economic dependence on the primary sector was identified as a source of environmental impacts in PCC. Table 6 shows the growth rate median of the total domestic extraction of materials (ton/km2) for the analyzed PCC. The growth rate medians report the period before and after the peace agreements using data from 1980 to 2013. Sierra Leone and Liberia presented significant higher growth rates of the total domestic extraction during the post-conflict scenario than in conflict. Higher growth rates of biomass extraction during post-conflict scenarios were found in Angola, Bosnia, and Sierra Leone. Extraction growth rates of industrial and construction minerals were higher in Burundi and Rwanda during post-conflict times, while the growth rate of ore extraction was higher in Bosnia, Liberia, and Sierra Leone during the post-conflict era.

5 Discussion

The analyzed PCC differ in the causes of armed conflicts (Table 1) and in their economic, environmental, and social characteristics (Table 2). The socioecological contexts of each country may determine the dynamics of a post-conflict scenario and rural environmental sustainability. Colombia shows the highest population and GDP per capita and the second highest score in the Human Development Index. However, Colombia shows the highest score in inequality of income distribution (GINI Index). In terms of environmental features, Colombia shows the highest proportions of total area in forest coverage and in natural protected areas, but at the same time shows one of the highest rates of natural resources extraction. The differences across PCC and Colombia limit the extrapolation of environmental transformations on the post-conflict Colombia. However, in this section we highlight the more common environmental impacts and drivers of change that were found in PCC, and we particularly discuss them in terms of the Colombian context. This discussion is not intended to prognosticate rural environmental pathways in Colombia; rather, it is aimed to stress the environmental challenges that Colombia may face in a post-conflict scenario.

5.1 Deforestation: a common impact in PCC and a current environmental problem in Colombia

Our results highlight that deforestation was the most common negative impact of both conflict and post-conflict periods (Tables 3, 4). Forest cover loss was reported in conflict and post-conflict periods in Bosnia, Liberia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone. Currently, deforestation is one of the most important environmental problems of Colombia. The expansion of agricultural frontiers for cattle ranching, illicit crops, domestic, and commercial forest exploitations, has been the biggest drivers of deforestation in Colombia (González et al. 2011; Rincón-Ruiz and Kallis 2013). Illegal mining activities have also prompted deforestation. During 1990 and 2010, the country lost 6 million ha of forest, especially in the Andes, Amazonian, and Caribbean region (DNP 2015).

Furthermore, our results show that in PCC (e.g., Burundi, Rwanda) return of displaced population has been identified as a driver of environmental impacts (Bunte and Monnier 2011; UNEP 2011; Ntampaka 2006). The current Colombian peace agreement proposed the creation of a ‘land fund’ (3 million ha) for a massive formalization of rural property (about 7 million hectares), especially directed to conflict victims. Addressing deforestation in post-conflict Colombia is urgent because deforestation also impacts soil quality, water resources, and the provision of ecosystem services to rural population (DNP 2015). Moreover in Colombia, hot spots of deforestation match with the designed territories for peace building (DNP 2015). The implementation of policies toward the return of displaced population in post-conflict scenarios should be integrated with policies addressing deforestation dynamics. In this direction, the current peace agreement in Colombia includes ecological restoration and economic programs in areas with illicit crops and payment for ecosystem services.

5.2 Land use conflicts in PCC and its current state in Colombia

Land use conflicts have been a recurrent environmental impact in conflict and post-conflict periods. In El Salvador, population growth and density have produced occupation of unfit and poor soil for agricultural production (Corriveau-Bourque 2013). This situation had resulted in land use conflicts, which in 2010 affected 49% of the total area of the country (MAG 2010).

Land use conflicts are a current problem in Colombia (DNP 2015). Colombia has 22 million hectares with suitability for agricultural activities. However, only 5.3% is currently used according to this suitability. Meanwhile, 15.6% of the total area of Colombia (17 million ha) suffer overexploitation, surpassing the natural productive capacity of soil. The agricultural frontier is also expanding, and it has been affecting areas of environmental interest. Data from 2000 to 2009 have shown an increase of agricultural, mining, pastures, and grassland areas, while water bodies and forests have decreased (DNP 2015).

These land use conflicts have contributed to soil quality degradation (i.e., soil erosion, desertification, and salinization). About 28% of Colombian territory has soil quality problems, and 40% of it has some level of erosion (IGAC 2014; DNP 2015). The use of chemicals, deforestation, conventional tillage practices, the use of heavy machinery, and intensive irrigation have also generated soil degradation (Pérez and Pérez 2002; Ortiz et al. 2011; DNP 2015). These anthropic causes are exacerbated due to the fragility of some soils and the effects of climate change and variability (DNP 2015).

The current situation of land use conflicts and soil degradation poses a critical challenge in the Colombian post-conflict context. Peace-building programs will have to face that more than 90% of the prioritized municipalities has land use restrictions (UN and German Cooperation 2015). Although Colombia has a variety of environmental policies which can play an important role for post-conflict scenarios, the biggest challenge the country will face is the joint and coordinated action with other State sectors toward meeting environmental objectives (Feola et al. 2015), particularly in relation to land use management (DNP 2015).

5.3 Ineffective land use planning as driver of change in PCC and a structural problem in Colombia

Ineffective land use planning was a common driver of environmental change in countries such as Angola, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and El Salvador (Table 5). For instance, in Angola, displaced people were relocated to their original territories without securing their livelihood conditions. This situation caused land use intensification which affected soil fertility (Cain 2013). In Sierra Leone, wetlands were considered as areas for agricultural expansion and thus increased the pressure over these ecosystems (Maconachie 2008). The ineffectiveness of land use planning in Colombia is currently driven by the high informality and insecurity of land tenure (DNP 2015). Moreover, the government’s lack of the ‘vacant land’ inventory has encouraged a pattern of land occupation without regulation and according to its suitability (DNP 2015). Furthermore, rural land use planning is still incipient due to technical and financial restrictions. There is also a convergence of multiple land use instruments which limits continuity and coherence of rural land planning (DNP 2015).

In Colombia, the implementation of the peace agreement intends to address the current limitations of land use planning (MC 2016). Some of the programs included are: massive formalization of land; the creation of a rural cadastre; and the implementation of an agricultural jurisdiction aimed to resolve conflicts of land use and tenure. Furthermore, the government will define general land use guidelines according to land suitability and will develop reconversion programs in land with use conflicts. Environmental land use planning will be developed with the aim of delimiting the agricultural frontier and protecting areas of environmental interest (i.e., Paramus, watersheds, wetlands, and water springs).

5.4 Dependency on the primary sector: a driver of change that is deepened in post-conflict scenarios

Another driver of environmental change in PCC was the economic dependency of the primary sector. This driver was reported in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burundi, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. For instance, Sierra Leone has more than one hundred mining companies, and 82% of its land is allocated in exploration or exploitation licenses. Moreover, nearly 10% of Sierra Leone’s arable land is under negotiation for agribusiness, mining, and industrial agriculture. In Liberia, extensive commercial logging, energy and mineral sectors, plantations and permanent agriculture, charcoal production, and mineral extraction were the main drivers of forest deforestation and degradation (REFACOF 2014).

In the last decades, Colombia has undergone a strong re-primarization process of the economy, mainly to mining and hydrocarbons (Pérez-Rincón 2016). This re-primarization has generated environmental and social effects that have resulted in socioenvironmental conflicts throughout the country (Pérez-Rincón 2016). Of the 115 recorded socioenvironmental conflicts, 94% of them have affected rural and suburban areas (Pérez-Rincón, 2016). The post-conflict scenario in Colombia envisions new opportunities for economic development in rural areas (García and Slunge 2015), and it is expected that the extractive economy will bring revenues for financing peace-building programs (McNeish 2016). Production of biofuels from palm oil and mining are among the sectors with potential growth. The government policy that promotes oil palm cultivation, maps out 3 million hectares of this crop by 2020 (Castiblanco et al. 2013). Moreover, mining has been declared as a national interest activity for economic and social development and currently represents 8% of national land use (Pérez-Rincón 2016; García and Slunge 2015). Scholars have reported the negative environmental impacts in Colombia of both oil palm cultivations (Marín-Burgos 2014) and mining (Ortiz et al. 2014; CGR 2013; Pérez-Rincón 2016).

Our results suggest that the extraction of natural resources can be intensified during the post-conflict scenario (Table 6): Almost all countries, except El Salvador, showed an increase of the median growth rates of extraction of at least one natural resource sector (i.e., biomass, fossil fuels, industrial, and construction minerals and ores). The re-primarization of the Colombian economy in the last decades and the current plans of expanding oil palm cultivation and mining, suggest the possibility of the intensification of natural resources extraction during the post-conflict Colombia and of its associated socioenvironmental impacts, such as it occurred in PCC.

A future intensification of natural resources extraction in Colombia will contradict peace-agreement intentions on delimiting the expansion of the agricultural frontier. This scenario can imply new sources of conflict between development projects—promoted from the national level—and local communities. Therefore, the most urgent challenge for the post-conflict scenario is the sectorial (e.g., agriculture, mining, trade, and infrastructure) and institutional coordination toward the execution, monitoring, and compliance of environmental policies (see Feola et al. 2015).

6 Conclusions

This study explores the dynamics of environmental sustainability in post-conflict countries, with the aim to provide insights for the current discussion on rural environmental sustainability in a post-conflict Colombia. We found that (1) deforestation and land use conflicts were frequent impacts in both conflict and post-conflict scenarios, that (2) return of displaced population, the ineffectiveness of land use planning, and the dependence on the primary sector were frequent drivers of environmental change; and that (3) natural resources extraction tends to be intensified after the signing of peace agreements. Every armed conflict and post-conflict scenario is the result of particular socioecological dynamics, which limit the extrapolation of such dynamics in a particular context. However, the common environmental dynamics identified in this research provides environmental elements on which to pay attention to if a country will enter into a post-conflict process, such as the Colombian case or other countries that are currently in conflict within biodiversity hot spots (c.f. Hanson et al. 2009) and could enter into peace processes (Syria, Lebanon, Sudan, Nigeria, Congo, Yemen, or Afghanistan).

Currently, Colombia suffers environmental problems such as deforestation and land use and tenure conflicts. And the institutional integration for environmental compliance is weak due to technical, legal, and financial limitations. With this background, the Colombian government projects the expansion of the extractive economy, among others, aimed to finance peace-building programs. On the other hand, the peace agreement includes environmental objectives such as the delimitation of agricultural frontiers and the implementation of participatory land use planning. Such contradictions between development and environmental objectives can jeopardize rural environmental sustainability in the post-conflict Colombia and thus may exacerbate socioenvironmental conflicts. The experience of environmental dynamics in post-conflict scenarios, together with the current Colombian environmental problems, recalls the urgency of strengthening environmental institutions, integrating long-term environmental objectives across all sectors, and deintensifying the dependence of the economy in the extractive sector.

The relationship between the environment and armed conflict has been widely evidenced (Ross 2004; Humphreys 2005; Van der Ploeg 2011). Thus, the environmental sustainability dimension should be integrated into peace agreements and post-conflict policies. Colombia peace agreement provides an outstanding example because it integrated environmental concerns. However, the responsibility of securing environmental sustainability cannot be only placed in the implementation of the peace-agreement policies. The preservation of such unique natural richness (e.g., the Amazon, Andes, and Chocó regions) should be a national consensus and a demand from the international community.

Notes

We found literature addressing environmental impacts in countries such as Afghanistan (UNEP 2003; Habib et al. 2013), Irak (UNEP 2007c), and Congo Democratic Republic (Debroux et al. 2007; Ijang and Cleto 2013; Burt and Keiru Huston 2014; Katunga and Muhigwa 2014). However, these countries are nowadays facing armed confrontations and therefore they were not included in the analysis.

References

Álvarez, M. D. (2003). Forests in the time of violence: Conservation implications of the Colombian war. Journal of Sustainable Forestry. doi:10.1300/J091v16n03_03.

Ansoms, A., & McKay, A. (2010). A quantitative analysis of poverty and livelihood profiles: The case of rural Rwanda. Food Policy. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.06.006.

Appel, B. J., & Loyle, C. E. (2012). The economic benefits of justice: Post-conflict justice and foreign direct investment. Journal of Peace Research. doi:10.1177/0022343312450044.

Arbeláez-Cortés, E. (2013). Knowledge of Colombian biodiversity: Published and indexed. Biodiversity and Conservation, 22(12), 2875–2906.

Ayres, R. U. (1994). Industrial metabolism: Theory and policy. In R. U. Ayres & U. E. Simonis (Eds.), Industrial metabolism: Restructuring for sustainable development (pp. 3–21). New York: UNU Press.

Beevers, M. (2012). Forest resources and peacebuilding: Preliminary lessons from Liberia and Sierra Leone. In P. Lujala & S. Rustad (Eds.), High-value natural resources and peacebuilding (pp. 360–367). London: Earthscan.

Behrens, A., Giljum, S., Kovanda, J., & Niza, S. (2007). The material basis of the global economy: Worldwide patterns of natural resource extraction and their implications for sustainable resource use policies. Ecological Economics. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.02.034.

Boron, V., Payán, E., MacMillan, D., & Tzanopoulos, J. (2016). Achieving sustainable development in rural areas in Colombia: Future scenarios for biodiversity conservation under land use change. Land Use Policy, 59, 27–37.

Brown, O., & Crawford, A. (2012). Conservation and peacebuilding in Sierra Leone. International Institute for Sustainable Development-IISD. http://www.iisd.org/pdf/2012/iisd_conservation_in_Sierra_Leone.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2016.

Brown, O., Hauptfleisch, M., Jallow, H., & Tarr, P. (2012). Environmental assessment and development: Initial lessons from capacity building in Sierra Leone. In D. Jensen & S. Lonergan (Eds.), Assessing and restoring natural resources in post-conflict peacebuilding (pp. 327–342). London: Earthscan.

Brown, G., & Langer, A. (2012). Elgar handbook of civil war and fragile states. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Bruch, C., Jensen, D., Nakayama, M., Unruh, J., Gruby, R., & Wolfarth, R. (2009). Post-conflict peacebuilding and natural resources. Yearbook of International Environmental Law., 19(1), 58.

Bunte, T., &. Monnier, L. (2011) Mediating land conflict in burundi: A documentation and analysis project. Accord. Retrieved from https://www.africaportal.org/dspace/articles/mediating-land-conflict-burundi-documentation-and-analysis-project.

Burgess, R., Miguel, E., & Stanton, C. (2015). War and deforestation in Sierra Leone. Environmental Research Letters. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/9/095014.

Burt, M., & Keiru Huston, B. (2014). Community water management: Experiences from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Afghanistan, and Liberia. In E. Weinthal, J. Troell, & M. Nakayama (Eds.), Water and post-conflict peacebuilding (pp. 95–115). London: Earthscan.

Cain, A. (2013). Angola: Land resources and conflict. In J. Unruh & R. Williams (Eds.), Land and post-conflict peacebuilding (pp. 177–204). London: Earthscan.

Castiblanco, C., Etter, A., & Aide, T. M. (2013). Oil palm plantations in Colombia: A model of future expansion. Environmental Science & Policy. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2013.01.003.

Corriveau-Bourque, A. (2013). Beyond land redistribution: Lessons learned from El Salvador’s unfulfilled agrarian revolution. In J. Unruh & R. Williams (Eds.), Land and post-conflict peace building (pp. 321–343). London: Earthscan.

CGR—Contraloría General de la República de Colombia. (2013). Minería en Colombia: Derechos, políticas públicas y gobernanza. http://www.contraloria.gov.co/documents/20181/472306/01_CGR_mineria_I_2013_comp.pdf/40d982e6-ceb7-4b2e-8cf2-5d46b5390dad. Accessed November 20, 2016.

Clover, J. (2005). Land reform in Angola: Establishing the ground rules. In Ground up: land rights, conflict, and peace in sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 347–380). Retrieved from https://www.issafrica.org/pubs/Books/GroundUp/7Land.pdf.

Crespin, S. J., & Simonetti, J. A. (2016). Loss of ecosystem services and the decapitalization of nature in El Salvador. Ecosystem Services, 17, 5–13.

Dávalos, L. M. (2001). The San Lucas mountain range in Colombia: How much conservation is owed to the violence? Biodiversity and Conservation, 10(1), 69–78.

Dávalos, L. M., Bejarano, A. C., Hall, M. A., Correa, H. L., Corthals, A., & Espejo, O. J. (2011). Forests and drugs: Coca-driven deforestation in tropical biodiversity hotspots. Environmental Science and Technology, 45(4), 1219–1227.

Debroux, L, Hart, T, Kaimowitz, D., Karsenty, A., & Topa, G. (Eds.) (2007). Forests in post-conflict Democratic Republic of Congo: Analysis of a Priority Agenda. A joint report by teams of the World Bank, Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Centre International de Recherche Agronomique pour le Developpement (CIRAD), African Wildlife Foundation (AWF), Conseil National des ONG de Developpement du Congo (CNONGD), Conservation International (Cl), Groupe de Travail Forets (GTF), Ligue Nationale des Pygmees du Congo (LINAPYCO), Netherlands Development Organisation (SNV), Reseau des Partenaires pour I’Environnement au Congo (REPEC), Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC), World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). xxii, 82p. ISBN 979-24-4665-6.

Delgado-Matas, C., Mola-Yudego, B., Gritten, D., Kiala-Kalusinga, D., & Pukkala, T. (2015). Land use evolution and management under recurrent conflict conditions: Umbundu agroforestry system in the Angolan Highlands. Land Use Policy. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.07.018.

DNP. (2015). El campo colombiano: un camino hacia el bienestar y la paz misión para la transformación del campo. Colombia. https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/Agriculturapecuarioforestal%20y%20pesca/El%20CAMPO%20COLOMBIANO%20UN%20CAMINIO%20HACIA%20EL%20BIENESTAR%20Y%20LA%20PAZ%20MTC.pdf. Accessed December 9, 2016.

Dulal, H. B., Brodnig, G., & Shah, K. U. (2011). Capital assets and institutional constraints to implementation of greenhouse gas mitigation options in agriculture. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. doi:10.1007/s11027-010-9250-1.

Evans, D. (2004). Using natural resources management as a peacebuilding tool: Observations and Lessons from Central Western Mindanao. Journal of Peacebuilding and Development. doi:10.1080/15423166.2004.374539576996.

FAO—Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2005). State of the World’s forest. Rome. http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5574e/y5574e00.htm. Accessed October 12, 2016.

FAO—Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2015). The forest sector in Bosnia and Herzegovina preparation of IPARD forest and fisheries sector reviews in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/a-au015e.pdf.

Feola, G., Agudelo Vanegas, L. A., & Contesse Bamón, B. P. (2015). Colombian agriculture under multiple exposures: A review and research agenda. Climate and Development. doi:10.1080/17565529.2014.934776.

Fischer-Kowalski, M., & Amann, C. (2001). Beyond IPAT and Kuznets curves: Globalization as a vital factor in analyzing the environmental impact of socio-economic metabolism. Population and Environment, 23(1), 7–47.

Fjeldså, J., Alvarez, M. D., Lazcano, J. M., & León, B. (2005). Illicit crops and armed conflict as constraints on biodiversity conservation in the Andes region. Ambio, 34(3), 205–211. doi:10.1579/0044-7447-34.3.205.

Forest Industries. (2011). Forest loss threatens Sierra Leone water supplies. http://forestindustries.eu/content/forest-loss-threatens-sierra-leonewater-supplies. Accessed March 7, 2016.

Garbarino, M., Mondino, E. B., Lingua, E., Nagel, T. A., Dukić, V., Govedar, Z., et al. (2012). Gap disturbances and regeneration patterns in a Bosnian old-growth forest: A multispectral remote sensing and ground-based approach. Annals of Forest Science. doi:10.1007/s13595-011-0177-9.

García, J., & Slunge, D. (2015). Environment and climate change management: Perspectives for post conflict-Colombia. Policy Brief. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/42061. Accessed September 8, 2016.

González, J. J., Etter, A. A., Sarmiento, A. H., Orrego, S. A., Ramírez, C., Cabrera, E., et al. (2011). Análisis de tendencias y patrones espaciales de deforestación en Colombia. Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología.

Guerra, M. D. R., & Plata, J. J. (2005). Estado de la investigación sobre conflicto, posconflicto, reconciliación y papel de la sociedad civil en Colombia. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 21, 81–92.

Global Witness. (2013). Logging in the shadows: An analysis of recent trends in Cameroon, Ghana, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Liberia. How vested interests abuse shadow permits to evade forest sector reforms. http://www.foresttransparency.info/report-card/2012/lessons-learnt/analysis=/938/logging-in-the-shadows-how-vested-interests-abuse-shadow-permits-to-evade-forest-sector-reforms/. Accessed August 8, 2016.

Global Witness. (2015). The new snake oil? Violence, threats, and false promises at the heart of Liberia’s palm oil expansion. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/land-deals/new-snake-oil/ Accessed December 9, 2016.

Habib, H., Anceno, A. J., Fiddes, J., Beekma, J., Ilyuschenko, M., Nitivattananon, V., et al. (2013). Jumpstarting post-conflict strategic water resources protection from a changing global perspective: Gaps and prospects in Afghanistan. Journal of Environmental Management. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.07.019.

Hanson, T., Brooks, T. M., Da Fonseca, G. A. B., Hoffmann, M., Lamoreux, J. F., MacHlis, G., et al. (2009). Warfare in biodiversity hotspots. Conservation Biology, 23(3), 578–587. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01166.

Hecht, S. B., Kandel, S., Gomes, I., Cuellar, N., & Rosa, H. (2006). Globalization, forest resurgence, and environmental politics in El Salvador. World Development, 34(2), 308–323.

Hecht, S. B., & Saatchi, S. S. (2007). Globalization and forest resurgence: Changes in forest cover in El Salvador. BioScience. doi:10.1641/B570806.

Herrador-Valencia, D., i Juncà, M. B., Linde, D. V., & Mendizábal, E. (2011). Tropical forest recovery and socio-economic change in El Salvador: An opportunity for the introduction of new approaches to biodiversity protection. Applied Geography, 31(1), 259–268. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.05.012.

Humphreys, M. (2005). Natural resources, conflict, and conflict resolution uncovering the mechanisms. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 49(4), 508–537. doi:10.1177/0022002705277545.

Ibáñez, A. M., & Vélez, C. E. (2008). Civil conflict and forced migration: The micro determinants and welfare losses of displacement in Colombia. World Development, 36(4), 659–676.

IGAC—Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi. (2014). Noticias.igac.gov.co: IGAC revela “anti ranking” de los departamentos con los mayores conflictos de los suelos en Colombia. Retrieved from http://www.igac.gov.co/wps/wcm/connect/c8eb398044ab6ec2bbd1ff9d03208435/IGAC+revela.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

Ijang, T. P., & Cleto, N. (2013). Dependency on natural resources: Post-conflict challenges for livelihoods security and environmental sustainability in Goma, The Democratic Republic of Congo. Development in Practice. doi:10.1080/09614524.2013.781126.

ILPI—International Law and Policy Institute. (2014). Protection of the Natural Environment in Armed Conflict: An empirical study. http://ilpi.org/publications/armed-conflicts-environmental-consequences-and-their-derived-humanitarian-effect/. Accessed December 9, 2016.

Kanyamibwa, S. (1998). Impact of war on conservation: Rwandan environment and wildlife in agony. Biodiversity and Conservation, 7(11), 1399–1406.

Katunga, M. M. D., & Muhigwa, J. B. (2014). Assessing post-conflict challenges and opportunities of the animal-agriculture system in the Alpine Region of Uvira District in Sud-Kivu Province, D.R. Congo. American Journal of Plant Sciences. doi:10.4236/ajps.2014.520311.

Kimonyo, J. P. (2006). Towards a sustainable management of the land problem in Burundi—How much land for how many people? Netherlands Institute of International Relations. Acceded December 12, 2016.

Le Saout, S., Hoffmann, M., Shi, Y., Hughes, A., Bernard, C., Brooks, T. M., et al. (2013). Protected areas and effective biodiversity conservation. Science, 342(6160), 803–805.

Lebbie, A. R. (2002). Distribution, exploitation and valuation of non-timber forest products from a forest reserve in Sierra Leone. (Doctoral dissertation). Njala University, Sierra Leone.

Leite, A. C. M. (2015). The potential of REDD+ as a conservation opportunity for the Angolan Scarp Forests: Lessons from the unique Kumbira forest. https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/82239. Accessed March 13, 2016.

Lindsell, J. A., Klop, E., & Siaka, A. M. (2011). The impact of civil war on forest wildlife in West Africa: Mammals in Gola Forest. Sierra Leone. Oryx, 45(01), 69–77. doi:10.1017/S0030605310000347.

Lujala, P., & Rustad, S. A. (2012). High-value natural resources and post-conflict peacebuilding. http://environmentalpeacebuilding.org/assets/Documents/LibraryItem_000_Doc_083.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2016.

Maconachie, R. (2008). New agricultural frontiers in post-conflict Sierra Leone Exploring institutional challenges for wetland management in the Eastern Province. The Journal of Modern African Studies. doi:10.1017/s0022278x08003212.

MAG—Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería de El Salvador. (2010). Conflicto de uso de suelo en la república de El Salvador. San Salvador. http://www.mag.gob.sv. Accessed December 12, 2016.

Marín-Burgos, V. (2014). Access, power and justice in commodity frontiers. The political ecology of access to land and palm oil expansion in Colombia. Doctoral thesis, University of Twente, The Netherlands.

Mbaiwa, J. E. (2004). Causes and possible solutions to water resource conflicts in the Okavango River Basin: The case of Angola, Namibia and Botswana. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 29(15–18), 1319–1326. doi:10.1016/j.pce.2004.09.015.

McCandless, E., & Christie, W. T. (2006). Moving beyond sanctions: Evolving integrated strategies to address post-conflict natural resource-based challenges in Liberia. Journal of Peacebuilding and Development. doi:10.1080/15423166.2006.133909151693.

MC—Mesa de Conversación Colombia. (2016). Acuerdo general para la terminación del conflicto y la construcción de una paz estable y duradera. Retrieved from https://www.mesadeconversaciones.com.co/sites/default/files/24-1480106030.11-1480106030.2016nuevoacuerdofinal-1480106030.pdf.

Mason, N. H. (2014). Environmental governance in Sierra Leone’s mining sector: A critical analysis. Resources Policy, 41, 152–159. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2014.05.005.

McNeish, J. A. (2016). Extracting justice? Colombia’s commitment to mining and energy as a foundation for peace. The International Journal of Human Rights. doi:10.1080/13642987.2016.1179031.

Niño, J., & Devia, C. (2015). Inversión en el Posconflicto: Fortalecimiento institucional y reconstrucción del capital social. Revista De Relaciones Internacionales. Estrategia y Seguridad., 10(1), 203–224.

Ntampaka, C. (2006). La question foncière au Burundi. Implications pour le retour des réfugiés, la consolidation de la paix et le développement rural. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations.

OCDE. (2014). Evaluaciones de desempeño ambiental. Colombia. http://www.oecd.org/env/country-reviews/Evaluacion_y_recomendaciones_Colombia.pdf . Accessed December 9, 2016.

Ordway, E. M. (2015). Political shifts and changing forests: Effects of armed conflict on forest conservation in Rwanda. Global Ecology and Conservation, 3, 448–460.

Ortiz, A. M., Cajiao, S., Lozano, J., Zárate, T., & Zárrate, G. (2014). Minería y medio ambiente en Colombia (No. 012025). FEDESARROLLO. http://www.fedesarrollo.org.co/wp-content/uploads/Fedesarrollo-Informe-Miner%C3%ADa-y-medio-Ambiente-final-final-final-080714.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2016.

Pérez, E., & Pérez, M. (2002). El sector rural en Colombia y su crisis actual. Cuadernos de desarrollo rural, 48(35), 58–65.

Pérez-Rincón, M. A. (2016). Caracterizando las injusticias ambientales en Colombia: estudio para 115 casos de conflictos socio-ambientales. Working paper, MA-CA-Univalle-0101. Proyecto Metabolismo Social y Conflictos ambientales en países andinos y centroamericanos. Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B2Tz54vt5A1SmpHMWJTQi1oNHc/view?pref=2&pli=1. Accessed June 9, 2016.

PNN—Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia. (2016). Registro Único Nacional de Áreas Protegidas de Colombia. http://runap.parquesnacionales.gov.co/. Accessed April 12, 2016.

Quaynor, L. J. (2012). Citizenship education in post-conflict contexts: A review of the literature. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice. doi:10.1177/1746197911432593.

REC—Regional Environmental Center. (2000). The Regional Environmental Reconstruction Program for South Eastern Europe (REReP). http://documents.rec.org/publications/buildingbetter_env_2000_eng.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2016.

REFACOF—African women’s network for community management of forests (2014). The role of women in deforestation and forest degradation in Liberia: A case study of women’s perception in Gbarpolu County. Report. http://www.itto.int/files/itto_project_db_input/3047/Technical/Rapport_Liberia_FINAL_Mai14.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2016.

REMA—Rwanda Environment Management Authority. (2009). Rwanda state of environment and outlook: Our Environment for Economic Development. http://www.unep.org/pdf/rwanda_outlook.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2015.

Rincón-Ruiz, A., Correa, H. L., León, D. O., & Williams, S. (2016). Coca cultivation and crop eradication in Colombia: The challenges of integrating rural reality into effective anti-drug policy. International Journal of Drug Policy, 33, 56–65.

Rincón-Ruiz, A., & Kallis, G. (2013). Caught in the middle, Colombia’s war on drugs and its effects on forest and people. Geoforum, 46, 60–78.

Rondinelli, D. A. (2008). The challenges of restoring governance in crisis and post-conflict societies. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and United Nations Development Programme, UN, NY. Public Administration and Development, 28(2), 165.

Ross, M. L. (2004). How do natural resources influence civil war? Evidence from thirteen cases. International Organization., 58(1), 35–67. doi:10.1017/S002081830458102X.

Rustad, S. A., & Binningsbo, H. M. (2012). A price worth fighting for? Natural resources and conflict recurrence. Journal of Peace Research. doi:10.1177/0022343312444942.

Schneibel, A., Stellmes, M., Röder, A., Finckh, M., Revermann, R., Frantz, D., et al. (2016). Evaluating the trade-off between food and timber resulting from the conversion of Miombo forests to agricultural land in Angola using multi-temporal Landsat data. Science of the Total Environment. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.137.

Suarez, A., & Calderon, P. (2015). Retos para la producción agropecuaria sustentable en Colombia. pp. 97-108. En: Rivera, Ramón (Ed.) Alternativas Sustentables de participación comunitaria para el cuidado del medio ambiente. Málaga, España. ISBN-13: 978-84-16399-67-3. http://www.eumed.net/libros-gratis/2016/1515/produccion.htm. Accessed October 12, 2016.

Tänzler, D. (2013). Forests and conflict: The relevance of REDD+. Environmental Change and Security Program Report, 14(2), 26.

Transnational Institute. (2004). Fumigaciones químicas y programa antidrogas. Recovered from https://www.tni.org. Accessed November 26, 2016.

Ugarriza, J. E. (2013). La dimensión política del postconflicto: discusiones conceptuales y avances empíricos. Colombia Internacional. doi:10.7440/colombiaint77.2013.06.

UNDP—United Nations Development Program. (2011). Colombia rural. Razones para la esperanza. Informe Nacional de Desarrollo Humano 2011. Bogotá: INDH PNUD. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/colombia/docs/DesarrolloHumano/undp-co-ic_indh2011-parte1-2011.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2016.

UNDP. (2017). Human Development Index (HDI). Human Development Reports. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi. Accessed Jan 14 2017.

UNEP—United Nations Environment Programme. (2011). Rwanda from post-conflict to environmentally sustainable development. http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/UNEP_Rwanda.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2016.

UNEP—United Nations Environment Programme. (2000). Post-conflict environmental assessment—FYR of Macedonia. http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/fyromfinalasses.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2016.

UNEP—United Nations Environment Programme. (2003). Afghanistan post-conflict to environmental assessment. http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/afghanistanpcajanuary2003.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2016.

UNEP—United Nations Environment Programme. (2007a). Sudan post-conflict environmental assessment. http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/sudan/00_fwd.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2016.

UNEP—United Nations Environment Programme. (2007b). Lebanon post-conflict environmental assessment. http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/UNEP_Lebanon.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2016.

UNEP—United Nations Environment Programme. (2007c). Iraq post-conflict assessment, clean-up and reconstruction. http://www.unep.org/disastersandconflicts/portals/155/disastersandconflicts/docs/iraq/Iraq_pccleanup_report.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2016.

UNEP—United Nations Environment Programme. (2010). Sierra Leone: From post-conflict to environmentally sustainable development. http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/Sierra_Leone.pdf Accessed June 8, 2016.

United Nations and Germany Cooperation. (2015). Consideraciones ambientales para la construcción de una paz territorial estable, duradera y sostenible en Colombia. http://www.co.undp.org/content/dam/colombia/docs/MedioAmbiente/undp-co-pazyambiente-2015.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2016.

Uppsala Conflict Data Program (2015). UCDP database. Uppsala University. http://ucdp.uu.se/. Accessed August 12, 2015.

US Forest Service International Programs, Department of Agriculture (2006). Technical assistance to the US Government Mission in Burundi on natural. https://rmportal.net/library/content/usda-forest-service/africa/USFS_Burundi_Trip_Report.pdf/. Accessed December 13, 2016.

Van der Ploeg, F. (2011). Natural resources: Curse or blessing? Journal of Economic Literature, 49(2), 366–420.

WIID-ONU. (2017). World Income Inequality Database. United Nations University. https://www.wider.unu.edu/project/wiid-world-income-inequality-database. Accessed Jan 14 2017.

Witmer, F. D. (2008). Detecting war-induced abandoned agricultural land in northeast Bosnia using multispectral, multitemporal Landsat TM imagery. International Journal of Remote Sensing. doi:10.1080/01431160801891879.

World development indicators. (2017). The World Bank development indicators data. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators. Accessed Jan 14 2017.

WU. (2014). Material flows database. http://www.materialflows.net/home/. Accessed August 19, 2016.

Acknowledgments

We thank Universidad De la Costa (Barranquilla, Colombia) for funding the project ‘Conservation agriculture and environmental sustainability strategy for Colombian post-conflict.’ We also appreciate the valuable suggestions of Ph.D. C. Botero-Saltarén, W. Hossack, J. Zúñiga-Barragán, and peer reviewers for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Suarez, A., Árias-Arévalo, P.A. & Martínez-Mera, E. Environmental sustainability in post-conflict countries: insights for rural Colombia. Environ Dev Sustain 20, 997–1015 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-9925-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-9925-9