Abstract

Fisheries management must take account of environmental sustainability, economic profitability, and social benefits generated by the public resources. The traditional approach of maximum economic yield (MEY), however, is yet to consider social objectives in deriving quantitative quotes. Current MEY evaluation framework would be appropriate if the economic rent was distributed back to the public. If public resources are privatized as corporations, the rent largely flows to the owners of large capital in the fishing industry. This is in stark contrast to the aims of benefiting the community as a whole. In this short paper, we promote a socially responsible framework in decision-making of fisheries management. This approach is beyond the fleet-based MEY approach, for it incorporates fleet profitability, chain profitability, employment, environmental concerns, and broad social benefits, in strict accordance with stock sustainability. Recognizing the needs of fishers, as well as the interests of chain sectors and the broader community, is a vital part of ensuring responsible fishery management and a viable future for Australian fisheries. The established framework will provide open view scenarios and enrich the MEY approaches in fisheries management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Making Society Better Off

In Australia, the general policy is to ensure the commercial fishing industry contributes to Australia’s economy, society, and environment. Maximum economic yield (MEY), which is deemed as the most efficient harvest reference point, is highly promoted and adopted. Where possible, the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) applies MEY harvest strategy targets to key fish stocks in Commonwealth-managed fisheries. However, the current MEY approach is based on fishing fleet, which considers only total revenues and the total costs of fishing.

The Australian Commonwealth Fisheries Harvest Strategy Policy and Guidelines [1] clearly stated that the proclaimed management objective is “maximising net economic returns to the community, within the context of ecological sustainability.” This policy has required consideration of social impacts when managing fisheries. In fact, the importance of social objectives in fisheries management has been more and more recognized by fisheries researchers, economists, and policy makers in recent years. And many published works [2,3,4] has discussed social objectives for either state or Commonwealth fisheries of Australia. Yet, there has been a lack of framework and challenges in quantifying the whole chain-based MEY for all sectors incorporating social objectives to derive harvest strategies, especially for the MEY approach.

Australia’s oceans are some of the richest in species and most diverse on our planet (https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/news/2010/08/australian-oceans-are-most-biodiverse/). However, the oceans do not seem rich at least in terms of harvested stock per unit area, which may due to over-cautious approaches. A catch of more than 8 million tons has been reported for 1950–2010 to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.

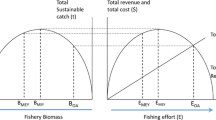

1.2 Fleet-Based MEY

MEY has been identified as a primary management objective for Australian fisheries and is under consideration elsewhere (Dichmont et al., 2015). The existing approach of MEY is fleet-based and used to authorize the profit-making of the fishing industry being a priority. One example is the Northern Prawn Fishery (NPF) in Australia, which is a multispecies tropical prawn fishery. Before 2000, the fishery had approximately 250 vessels in the 1980s and 120 vessels in the 1990s. The sustainable catch for the tiger prawns alone was estimated as 4000 t [5]. A bioeconomic study framework based on yield per recruit was also established to determine the fishing effort and season closure dates by Somers and Wang [6]. However, due to a number of reasons, its value is halved since the fleet-based MEY approach was implemented. Apart from the falling prawn prices, another key contributing factor is the total catch has been drastically reduced (as the total number of vessels is only 52). This makes people wonder if the fleet-based MEY approach should be modified toward maximum sustainable yield (MSY) so that more catches are allowed to benefit public instead of just the income for the fishing industry [7].

While Australia targets maximum MEY, our next door neighbor country New Zealand targets MSY. The MEY approach is to consider the fishing efficiency for the benefit of the fishing industry while the MSY approach is from the biological perspective that determines the limited amount we can remove each year. For an excellent review on this topic, see Bromley [8], Christensen [9], and Sumaila and Hannesson [10]. Bromley [8] has provided rigorous justification for why fleet-based MEY is not the same as “making society better off.” Pascoe et al. [11] recently shared their experience in Australian fisheries and compared with New Zealand fisheries managed by a counterpart approach.

When applying fleet-based MEY, government resource was devoted to increase the profit of a few companies which have a de facto monopoly on the resource. This approach is appropriate if the resource rent is fully collected by the government and redistributed to the society. This is partly achieved by collecting license fees of the fleet, but not going far enough. There is an urgent need to develop a framework, to fundamentally answer a key question: which side we stand for and whose benefit we are maximizing for. The fundamental problem here is the disconnection between objectives at the policy level (e.g., the Commonwealth Fisheries Harvest Strategy Policy, HSP) and the actual management at the operational level. In the HSP, MEY means “maximising net economic returns to the community, within the context of ecological sustainability,” which appears to be socially responsible. However, at the operational level, MEY is estimated purely based on fleet profitability ignoring the HSP objective: as to how the benefit should be distributed among the public that consists of different cohorts with different interests in different sectors, how the benefit flows should be modeled and the total benefit for the whole society should be maximized, not just the gain for a particular sector. This is the focus of our discussion. The established society-based MEY would provide an open view on fisheries management that is subject to more discussions among fisheries modelers, economists, and policy makers. The essential characteristic of this approach is to have the community’s interests clearly defined and incorporated.

1.3 Conflicts in the Objectives

There has long been a debate over the issue of maximizing economic efficiency (for fishing companies) versus community benefit in fisheries. Currently, the social concerns have been overwhelmed by arguments and criticisms from fisheries economists, who set social responsibilities (such as job creation and other happiness impacts) against “efficiency.” The current fleet-based MEY approach stops the benefit flow to other sectors, and does not account for the benefit drained from the community either. This might be the worst welfare-economic deal possible for the community, who does not benefit from the use of their public resources (i.e., the fish stocks), but pays higher prices for seafood because supply is maintained artificially low.

Including social objectives in management decisions is not necessarily conflicting with managing for healthy stocks and good economic returns. The framework we established here makes it possible to balance environmental, social, and economic goals.

2 Methods

2.1 Fleet-Based MEY Versus Value Chain-Based MEY

Applying social responsibility in fisheries management requires accounting for all interests in our community, when determining the optimal harvest level. The cost or gain must be dealt with carefully; one person’s cost can be another person’s gain (cf. Table 1). In fisheries, the income for the fishing industry is [12]:

where Y is the yield; P is the average fish price; E is the fishing effort; C is the total cost including labor, processing, fuel, license, and whatever the fixed or variable costs are. Here, the sustainable yield Y is generally calculated from the stock assessment models (i.e., MSY analysis) and as an input in the model. The fleet-based approach only considers cost in the fishing industry (Table 1).

Suppose nv is the number of vessels. Under the fleet-based approach, the income for the government is nv × cL, where cL is the license fee. Company tax paid on the resource rent gifted to companies by the Commonwealth is also taxed by the Commonwealth. So, the same jurisdiction receives the tax. But note that this tax does not occur in Australian state fisheries.

Now, let us expand the domain. We define a multiplier effect γ, which is the market price of fish. The total value of processed fish products increases from one sector to the next in the value chain, ending with consumers who bear the final cost for their consumption. γ consists of γ1, γ2, … , γn, depending on how many sectors (n) are involved in the chain, from dockside to dinner table. The net revenue in each sector starting from fleet is:

Here, Pf is the dockside fish price, and C0 is the cost in the fishing industry.

In intermediate sectors, besides the large cost of buying fish stocks, other costs include labor costs, the price of buying other goods and services, and taxes. If we simply assume the average cost proportion in each intermediate sector to be p, we have:

where γ = γ1γ2 … γn and p is always between 0 and 1. When γ ≫ C0/PfY, the MEY becomes almost the same as the MSY level. In the case of γ = 1, it becomes the fleet-based approach.

The parameter γ extends the scope beyond the fishing sector; the gross revenue from the community perspective is γPY. As there is always value added through the processing and marketing chain (i.e., a profit for each sector) for the sectors to remain viable [8], this results in γ > 1. The economic (multiplier) effect of fisheries in Australia was 5.79 [10].

Sumaila and Hannesson [10] argued that one has to take into account the productive resources necessary to obtain a product for some end use. Obviously, more fish needs more handling and processing, which means more cost. Normally, the additional cost will be covered by the next sector who buys fish from the fish wharf. If the fishing industry pays for the cost, it means they earn less economic rent. At an extreme case, PfY = C0, the fishing industry will earn no economic rent; and p = 1, all chain sectors make no extra profit. Bromley [8] pointed out, even under that situation, all sectors still make normal profit (including salaries and all operating costs). Note that collecting economic data and conducting bioeconomic modeling also incur substantial additional costs.

2.2 The Benefits of Applying Social Objectives

2.2.1 People

Employment is a shadow profit but is often treated as a cost. But it is not a cost to the society. Actually, the social performance of fisheries has been measured mainly through the use of income and employment figures. The fishers’ income, which is clearly a labor cost for the fishing industry, is also a source of income for the fishers. From the society viewpoint, the crew cost is like moving money from the left hand pocket and putting it back in the right hand pocket. Applying the society-based MEY approach also maintains/creates jobs in fish chain sectors. Some may worry that additional catch would result in drop in dockside price (Pf). In that case, the broader community consumers would be benefited.

2.2.2 Government

Let us look at the economic rent collected by the government. Under fleet-based approach, the income is from license fee and taxes. Commercial fishers pay a license fee to access a particular marine resource and pay for the right to own quota units of a particular species. These fees are often substantial as they support management, compliance, and research in that fishery. That license fee is even not a real “cost” to the fishing industry—the money has been put back into fisheries and benefit fisheries. When society-based MEY is applied, part of the rest of the economic rent (not collected by the government) flows into other sectors, especially for the fisheries-dependent sectors such as processing, distribution, and retail. Because the fleet-based MEY approach does not adhere to the objective described in the high-level policy, we recommend incorporating societal benefits to better achieve the management objective at the operational level. For example, if MEY is close to MSY, the simple approach may be to adopt MSY as a limit rather than as a target. Setting MSY as a limit has been widely recognized outside Australia.

3 Discussion

The fleet-based MEY approach has kept the fishing effort at a low level and stopped “rent drain” to the society, with the consequence of low economic effect in the broad economy. It is true that when the fisheries collapse, the fishing sector would perish and fishermen would have to find alternative employment. However, fishermen, and particularly those with vertically integrated businesses, place a lot of value on certain skilled employees, who play various roles within the company. In reality, businesses often continue to operate long into overdraft situations in an attempt to retain staff and keep their businesses operating. That is not what we promote. We argue for extra caution when lowering fisheries employment, when the fish stocks are considered healthy.

Some may argue that the fish caught by the fishing industry in Australia is sold to international consumers, thus it makes no sense to increase the captures of fish to benefit the other sectors. Even for fish stocks which would be exported, benefits are not at maximum from the social perspective. Fleet-based MEY is a suitable reference point only when the resource rent is fully collected by the government and is used to benefit the society. However, under the current situation where a large resource rent is collected by private companies, extending fleet-based MEY to a broad MEY would help re-distribute the resource rent in the economy. Fleet-based MEY is benefiting the fishing companies by exploiting public resources. Controls and regulations by the government are needed on commercial exploitation of fish resources—as a government function. Employment costs are absorbed in a sense when using a social benefits model, while the employers will argue against the social benefits model because their benefit will partially flow to the society due to more employment. In Australia, the total allowable catches (TAC) are obtained from fleet-based MEY and then individual transferable quotas (ITQs) are allocated. A TAC management strategy imposes an extra risk of overfishing due to natural and fishing-induced variability in stocks [13]. For this reason, input controls are more sensible. Stock assessment should be modified to account for the great natural variability in abundance, high reproductive potential, and resilience of marine fishes, relative to other taxa [14,15,16].

Globally, many fish stocks have been depleted due to overexploitation, pollution, and habitat loss [17]. In open access fisheries, fishing often reaches or even goes far beyond a cost-neutral position before it stops. Government subsidies are often granted to fisheries when the margin is low or negative, especially in developing countries. Thus, the precautionary approach was introduced to limit lost yield to overexploitation. It can be criticized that government assistance to unprofitable fisheries would result in government funds being diverted to inefficient uses (unprofitable fisheries) and away from other uses (roads, hospitals, and others). However, a broad MEY is far from being unprofitable even in the fishing sector [8].

Bycatch problems and the ecological stress on the environment and the targeted fish stocks due to the increased fishing pressure also need careful consideration and evaluation. However, the indicators of human-caused impacts are controversial and often difficult to collect. Nonetheless, fishing generates benefits, apart from food, employment, and income, and all of these benefits need to be factored into “economic” models to maximize benefit from replenishable natural resources.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) states that the goal for harvesting fish species is to achieve MSY. There is a broad range of existing parameter values for determining MEY beyond the scope of fishing fleet. And there is a need to bridge the gap in objectives between fisheries management and social benefits. While it is acceptable to have low fishing effort in order to protect fish stocks, there is much to consider before shrinking to fleet-based MEY. The rent “drain” from the fishing sector should be accepted, as it drains to the society, causing people to benefit from our precious resources.

4 Concluding Remarks

While we agree that the MEY theory is valid, we argue that determination of MEY is dynamic. Another disadvantage of MEY-based management involves large uncertainty. The estimated MSY is already highly uncertain for most fisheries. Adding economic variables on top of the uncertain biological parameters makes the estimated MEY very unreliable. Furthermore, collecting economic data and doing bioeconomic modeling incur additional costs. The fleet-based approach is not applicable to natural resources, with the reasons:

-

1.

The resource rent is not fully collected by the government and re-distributed to the broad community.

-

2.

Maximizing economic rent for private companies should not be obfuscated with the fishery efficiency.

-

3.

The benefit drained from the broad community is not accounted for, which leads to lower optimal fishing effort and catch levels.

-

4.

The large cost of buyback scheme is not factored in when moving MSY to fleet-based MEY. The cost is large to the government.

-

5.

Within the fleet, the fishing crew incomes and employment are also set at a minimum, when maximizing the fleet profit (fleet-based MEY).

-

6.

From the perspective of the “best interests of the community” [8], a fishery managing to achieve fleet-based MEY is unlikely to perform at full economic efficiency.

The society-based MEY approach that we are promoting simply factors in other benefits generated by the fishery—it may be beyond the traditional fleet-centric economic theory (which is largely confined to maximizing profit of the harvesting firms or fishing industry itself) and requires multidisciplinary research (social science, decision theory, and biological science, in particular).

The resource rent extracted via license fees is only a small proportion of the MEY value—possibly just as a proportion of cost recovery with an overall neutral effect. The absence of license fees would imply subsidy. Collection of the resource rent by the government or the broader community will result in greater catch and effort levels in fisheries compared to fisheries that operate at MEY. It balances a greater benefit to the society against the cost of reducing profitability of fishing fleets.

References

DAFF. (2007). Commonwealth fisheries harvest strategy: policy and guidelines. Canberra: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

Pascoe, S., Dichmont, C. M., Brooks, K., Pears, R., & Jebreen, E. (2013). Management objectives of Queensland fisheries: putting the horse before the cart. Marine Policy, 37, 115–122.

Pascoe, S., Brooks, K., Cannard, T., Dichmont, C. M., Jebreen, E., Schirmer, J., & Triantafillos, L. (2014). Social objectives of fisheries management: what are managers’ priorities? Ocean and Coastal Management, 98, 1–10.

Brooks, K., Schirmer, J., Pascoe, S., Triantafillos, L., Jebreen, E., Cannard, T., & Dichmont, C. M. (2015). Selecting and assessing social objectives for Australian fisheries management. Marine Policy, 53, 111–122.

Wang, Y. G., & Die, D. (1996). Stock-recruitment relationships of the tiger prawns (Penaeus esculentus and Penaeus semisulcatus) in the Australian northern prawn fishery. Marine and Freshwater Research, 47(1), 87–95.

Somers, I., & Wang, Y. G. (1997). A simulation model for evaluating seasonal closures in Australia’s multispecies northern prawn fishery. N. Am. J. Fish. Manage., 17(1), 114–130.

Wang, Y. G., & Wang, N. (2013). Rejoinder to Pascoe et al.’s (2013) comment paper. Fisheries, 38(11), 509–509.

Bromley, D. W. (2009). Abdicating responsibility: the deceits of fisheries policy. Fisheries, 34, 280–290.

Christensen, V. (2010). MEY = MSY. Fish and Fisheries, 11, 105–110.

Sumaila, U. R., & Hannesson, R. (2010). Maximum economic yield in crisis? Fish and Fisheries, 11, 461–465.

Pascoe, S., Kahui, V., Hutton, T., & Dichmont, C. (2016). Experiences with the use of bioeconomic models in the management of Australian and New Zealand fisheries. Fisheries Research, 183, 539–548.

Grafton, Q., Adamowicz, W., Dupont, D., Nelson, H., Hill, R. J., & Renzetti, S. (2008). The economics of the environment and natural resources. John Wiley & Sons.

Hsieh, C., Reiss, C. H., et al. (2006). Fishing elevates variability in the abundance of exploited species. Nature, 443, 859–862.

Beddington, J. R., & May, R. M. (1977). Harvesting natural populations in a randomly fluctuating environment. Science, 197, 463–465.

May, R., Beddington, J. R., et al. (1978). Exploiting natural populations in an uncertain world. Mathematical Biosciences, 42, 219–252.

Hutchings, J. A. (2000). Collapse and recovery of marine fishes. Nature, 406, 882–885.

Ye, Y., Cochrane, K., et al. (2012). Rebuilding global fisheries: the World Summit Goal, costs and benefits. Fish and Fisheries, 14(2), 174–185.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, J., Wang, N., Hu, ZH. et al. Incorporating Social Objectives in Evaluating Sustainable Fisheries Harvest Strategy. Environ Model Assess 24, 381–386 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10666-019-9651-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10666-019-9651-9