Abstract

This paper examines the interactions between financial development, economic growth and (macro)prudential policy on a sample of 12 euro area countries. Our main takeaway is that active (macro)prudential policy supports the positive finance-growth nexus instead of disrupting it. These benefits are found to be more likely to materialize during tightening of (macro)prudential policy measures and not during easing. This result is conditional on the ability of (macro)prudential policy to curb excess credit growth and mitigate systemic risk, which would otherwise disrupt the market. Moreover, we assert that when analysing the effects of (macro)prudential policy, it is important to account for the direction of (macro)prudential measures, not just for the frequency at which they are implemented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Financial development is an important condition for sustainable growth. Improvements in the key functions of the financial sector promote economic growth through capital accumulation and technological progress. Furthermore, they foster productivity, mobilize savings and investment and broaden access to finance in the population. The majority of empirical studies find a positive and statistically sound relationship between financial development and economic growth (see Arestis et al. 2015; Biljsma et al. 2017 and Valickova et al. 2015 for meta-analytical evidence).

However, the finance-growth relationship is much more complex and deserves further exploration. It is now widely recognized that excessive growth in the financial sector might endanger the economy when it results in a financial crisis (Cerra and Saxena 2008; Abiad et al. 2009; Reinhart and Rogoff 2008). In this respect, the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 serves as a particularly costly reminder of the destabilizing effects of major fluctuations in the financial sector (Ball 2014). In response to the crisis, multiple policies have been put forward by academics, central banks, regulators and other policy makers, aimed at preventing systemic risk build-ups and thus reducing the likelihood and impacts of crises on the financial sector and the economy as a whole. In fact, the importance of a sound regulatory framework is expected to grow as financial development progresses.

One of the newly emphasized policies is macroprudential policy, which aims at promoting financial stability. Macroprudential policy measures avert the emergence of financial imbalances and build resilience in the financial sector in good times so that financial intermediation and lending can support the economy in bad times (Smets 2014; Sánchez and Röhn 2016). As a relatively new policy, it attracts the attention of researchers, who study its use, effectiveness and interactions with other existing policies to identify its impacts on financial sector development and economic growth.

In this paper, we provide new empirical evidence on the interactions between financial development, (macro)prudential policy and economic growth. We demonstrate that the established finance-growth nexus is affected by active use of (macro)prudential policy measures. We find that economies that have been actively using (macro)prudential policy tend to benefit from financial development more than economies where (macro)prudential policy is less active. Interestingly, this only becomes evident when we consider the direction of (macro)prudential policy measures instead of relying on mere frequency of use in the form of a cumulative index.

There are two other studies (to our knowledge) that empirically assess (macro) prudential policy implications for the finance-growth nexus. Bernier and Plouffe (2019) examine the impact of financial innovation on economic growth using R&D expenditure in the financial services sector and evaluate the influence of macroprudential policy on this relationship. They rely on an unbalanced panel of 23 countries spanning 1996–2014 and do not find any evidence of macroprudential policy influencing the finance-growth nexus. Agénor et al. (2018) use country-level data from 64 advanced and developing economies over the 1990–2014 period and analyse the empirical link between financial openness, prudential policies and economic growth. They find that economies where prudential policy is used to tighten credit conditions tend to benefit from higher growth. At the same time, they discover that higher financial openness tends to offset this positive effect.

Our study differs from the two mentioned above in several important respects. First, we track down the finance-growth nexus while differentiating between the frequency and the direction of (macro)prudential policy measures. To this end, we accommodate two (macro)prudential policy indexes developed by Cerutti et al. (2017a, b). We discover that the initial choice of (macro)prudential policy index delivers significantly different point estimates as regards the impact on the finance-growth nexus. Second, we extend the period analysed past 2014, when most of the (macro)prudential policy measures took effect. This extension is important, as we record over 150 (macro)prudential policy actions in our sample in the 2014–2017 period alone, as compared to a total of 220 over the whole 2000–2013 period. We run our analysis on a sample of twelve euro area countries. The euro area can be considered an appropriate panel to investigate the macro-financial linkages, particularly because, thanks to financial integration and converging prudential regulations (Romero-Ávila 2007), the countries are relatively homogenous compared to the rest of the world (Creel et al. 2015; Bengtsson 2020).

The remainder of the paper is organized into five sections. The following section contains a literature review. Section 3 introduces our data and summary statistics. Section 4 describes our baseline specification results. Section 5 subjects our results to a battery of robustness tests. Section 6 concludes.

2 Literature review

The idea to theoretically connect financial system with economic development dates back to the works of Bagehot (1873) and Schumpeter (1952). The empirical analysis of the finance-growth nexus was conducted for the first time in the 1990s and has been led by a seminal paper by King and Levine (1993), which confirm Schumpeter’s view that financial system can promote economic growth on data from 80 countries. Most of the authors agree on existence of a relationship between finance and economic growth, but the direction of causality is further discussed and elaborated on. First strand of literature attains to a causal direction from financial development to economic growth, i. e. policies leading to development of financial systems lead to economic growth (McKinnon 1973; King and Levine 1993; Levine, et al 2000). Second group of papers argue in favour of the direction coming from economic growth to financial development, i. e. growing economy increases demand for financial services and thus induces financial sector expansion (Gurley and Shaw 1967; Goldsmith 1969; Jung 1986). Lastly, some papers postulate that the causal direction is two-way, so financial development and economic growth reinforce each other (Patrick 1966; Blackburn and Hung 1998; Khan 2001). In the 2000s, studies started to indicate that the finance-growth nexus can also be of a non-linear nature (Rioja and Valev 2004; Cecchetti and Kharroubi 2012; Arcand et al. 2015).

Studies published after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis tend to be more critical on the positive relationship between financial development and economic growth. Rousseau and Wachtel (2011) find out that the nexus is not as strong on more recent data, as increased fragility and occurrence of financial crises reduces the impact of financial development on economic growth. This view is further empirically confirmed by Beck et al. (2014) who add a summary on how oversized financial sector may hamper the real economy. Arcand et al. (2015) show that financial depth starts having a negative effect on output growth when credit to the private sector reaches 100% of GDP. Other recent empirical studies also find more finance is only good up to a certain point, after which it starts to worsen the socio-economic outcomes (Cecchetti and Kharroubi 2019; Čihák and Sahay 2020). This strand of literature goes hand in hand with studies showing that financial development can increase the probability of financial distress (Loayza and Ranciere 2006; Mendoza et al. 2009; Caprio et al. 2014) which, in turn, tends to slow down economic growth (Creel et al. 2015; Prochniak and Wasiak 2017; Balta and Vašíček 2020).

(Macro)prudential policy aims at preventing and mitigating excessive credit growth, systemic risk and leverage by increasing resilience of the financial system which in turn lowers the probability of a banking crisis. This has been widely described and documented in the recent literature, both theoretically (Galati and Moessner 2013; Bianchi and Mendoza 2018) and empirically (Claessens et al. 2013; Sánchez and Röhn 2016; Araujo et al. 2020; Nakatani 2020). One can expect that active (macro)prudential policy, when achieving its main goals and objectives, would lead to faster, yet more sustainable economic growth. On a sample of euro area countries, Creel et al. (2015) show that finance effects are not favourable to economic performance, because of the high level of financial depth. However, they point out that the consideration of institutional and regulatory framework can influence their analytical outcomes. In our analysis, we elaborate on this statement by considering the effects of active (macro)prudential policy (Table 1).

3 Data

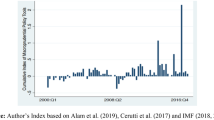

We base our econometric analysis on annual data collected from a variety of sources. Our dataset is a balanced panel of twelve euro area countries spanning 2000–2017. Table 8 in the “Appendix” presents a data overview and summary statistics. In a monetary union such as the euro area, country-specific imbalances cannot be offset by the uniform monetary policy and are hard to correct using the institutionally constrained fiscal policy. (Macro)prudential policy provides countries with a set of tools that can be tailored to specific risks on the national level, tools which have shorter implementation lags than other public policies to offset divergences in national financial cycles and promote sustainable growth (Fig. 1).

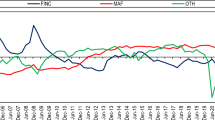

Our first set of variables aims to capture economic performance. For this purpose, we rely on the three indicators most commonly found in the empirical literature: gross domestic product (GDP), GDP per capita (GDPPC) and gross value added (GVA) in nominal terms. The data on all the variables are seasonally adjusted and transformed into annual growth rates (Fig. 2).Footnote 1

Source: World Bank, Svirydzenka (2016), own elaboration. Note: The shaded regions mark the area between the first and third quartile and minimum and maximum of the cross-country distribution. The solid red line denotes the mean and the dashed blue line the median. The sample size is 12 countries

Economic Growth and Financial Development in Twelve Euro Area.

Our second indicator of interest is the Financial Development Index (FDI) taken from the IMF database and described in Svirydzenka (2016). The FDI ranges from 0 to 1; the higher the number, the more financially developed the country is. To improve the interpretation value of the indicator, we multiply the raw data values by 100 (Fig. 2). Hasan et al. (2018) state that the most common indicators of financial development depict the depth, efficiency and stability of the banking sector and the depth and efficiency of stock markets. All of these aspects are covered in the FDI.

Our third indicator captures the effects of (macro)prudential policy measures. We rely on two indexes: the Macroprudential Policy Index constructed by Cerutti et al. (2017a) and the Prudential Policy Index from Cerutti et al. (2017b). We employ two different measures, because the first captures frequency of (macro)prudential policy actions, while the latter also contains information on direction of such actions. Therefore, we can also analyse whether active (macro)prudential policy (without considering the direction of its measures) has an impact on the finance-growth nexus or whether such impact is influenced by the tightening or loosening nature of (macro)prudential policy actions.

Since the ready-to-use data start in 2000 and end in 2014, we extend the datasets using data from Budnik and Kleibl (2018) and ESRB (2020) following the methodology of the original indexes. Altogether, these different data sources allow us to produce two indexes of (macro)prudential policy measures over the 2000–2017 period. As there is less consensus on data related to prudential regulation compared to data on economic growth and financial development, we explain in more detail how these data were originally compiled and treated in the following paragraphs.

The Macroprudential Policy Index (MPI) contains twelve macroprudential policy instruments as simple binary variables. The macroprudential instruments covered are the general countercyclical capital buffer/requirement, the leverage ratio for banks, time- varying/dynamic loan-loss provisioning, caps on the loan-to-value ratio and the debt-to- income ratio, limits on domestic currency loans, limits on foreign currency loans, reserve requirement ratios in foreign currency, a levy/tax on financial institutions, capital sur- charges on systemically important financial institutions, limits on interbank exposures and concentration limits. The index for each of the instruments employed takes the value of 1 if it is active and 0 if it is inactive. An overall macroprudential index is calculated as the simple sum of the scores for all instruments (Fig. 1, panel A). The MPI does not consider the direction of the instruments (whether the policy is tightening or loosening).

The Prudential Policy Index (PPI) comprises actions of a (micro and macro) prudential nature and records changes and their effect. It covers nine types of prudential instruments: general capital requirements, real estate credit-related specific capital buffers, consumer credit-related specific capital buffers, other specific capital buffers, domestic currency capital requirements, foreign currency capital requirements, interbank exposure limits, concentration limits and loan-to-value (LTV) ratio limits. The instrument has a 1 or -1 entry depending on whether the prudential tool was tightened or loosened in the given period. The index equals 0 in those years when no change occurs (Fig. 1, panel B).Footnote 2

We divide the instruments included in the indexes in two main categories – capital-based and borrower-based. The capital-basedFootnote 3 instruments primarily target the banks, while the borrower-basedFootnote 4 measures limit borrowing of firms and households. This categorisation allows us to differentiate between different types of (macro)prudential policy measures in the further analysis.

Visual inspection of the two indexes in Fig. 1 shows that the frequency of use of (macro)prudential policy instruments is growing over time. Furthermore, the nature of the policies shifted from loosening at the beginning of the sample to tightening at the end of the sample. As of 2014, all instruments implemented in the panel of countries analysed were of a tightening nature. Moreover, the data point to a large degree of heterogeneity across the countries analysed (Fig. 3). The heterogeneity does not appear to be explained simply by country size, degree of openness, regional or other specific factors. For this reason, we decided to employ a dynamic panel data analysis as described in the next section, which allows us to exploit the cross-sectional variability in the sample.

4 Finance-growth nexus and (macro)prudential policy

To study the effect of (macro)prudential policy measures on the finance-growth nexus, we run a series of panel regressions in which (\(\Delta {y}_{i,t}\)) is economic growth. We begin with a baseline specification in which (\(\Delta {y}_{i,t}\)) is regressed on the financial development index (\(FD{I}_{i,t}\)):

The \(\gamma\) coefficient measures the strength of the finance-growth nexus. We employ country-fixed effects (\({\delta }_{i}\)) to control for unobserved factors across countries. The model is estimated using the Blundell and Bond (1998) System-GMM (Generalized Method of Moments) with Instrumental Variables to mitigate the reverse causality problem.Footnote 5 Motivated by the finance-growth literature, we employ a wide range of controlsFootnote 6 stacked in vector \({X}_{i,t-1}\) that include: labour productivity growth (\(labou{r}_{i,t-1}\)), trade openness (\(ope{n}_{i,t-1}\)), the inflation rate (\({inf}_{i,t-1}\)), the ECB monetary policy conditions index (\(MC{I}_{i,t-1}\)),Footnote 7 and a financial crisis dummy (\(crisi{s}_{i,t}\)).Footnote 8

The results of the baseline model specification are shown in Table 1. We confirm the existence of the finance-growth nexus for our sample countries using the 2000–2017 data. More specifically, a one-point increase in the \(FD{I}_{i,t}\) is associated with about a 0.24 pp increase in GDP growth. This estimate is fairly standard and places us close to the mean of the estimates of other studies surveyed in Arestis et al. (2015) and Valickova et al. (2015). The estimate is robust across different model specifications. Our control variables have the expected sign. Note that we are able to trace the relationship further back in time (1980–2017, see Table 1) but this time span cannot be matched to the dataset of the (macro)prudential policy actions which is available since 2000.

4.1 How robust is the finance-growth nexus to (macro)prudential policy actions?

In this section, we test whether the established finance-growth nexus would be in any way affected by active (macro)prudential policy. To this purpose, we consider a set of extended regressions where (in line with our earlier discussion) we allow the effect of financial development on economic growth to depend on the frequency and the direction of (macro)prudential policy measures (\({MPP}_{i,t}\)). We augment Eq. (1) with the following interaction term:

where in \({MPP}_{i,t}\) we gradually consider changes to the Macroprudential Policy Index \(\left({MPI}_{i,t}\right)\) which measures the frequency of macroprudential policy actions and the Prudential Policy Index \(\left({PPI}_{i,t}\right)\) that measures the direction of such actions. The \(\zeta\) coefficient reflects the joint impact of financial development and active (macro)prudential policy on economic growth.Footnote 9

The results of the augmented model are summarized in Table 2. We find that accounting for the frequency of macroprudential policy measures tends to offset the positive effects of financial development on economic growth (columns 1, 2 and 3). Since macroprudential policy is of a preventive nature, it may be overly limiting in terms of its influence on bank lending, thus lowering economic growth.Footnote 10 Sánchez and Röhn (2016), who also employ \({MPI}_{i,t}\) to investigate the link between macroprudential policy and GDP growth, argue that more frequent use of macroprudential policies may be associated with lower economic growth.

However, the appropriateness of employing a cumulative macroprudential policy index such as \({MPI}_{i,t}\) should be discussed. One possible caveat is associated with the reverse causality problem for which is impossible to control at full. Specifically, countries may choose to implement certain (macro)prudential policies in response to output growth conditions. One other issue is the danger of recording a spurious regression. Trying to explain economic growth by the mere number of new policy instruments might by tricky for several reasons. First, one cannot distinguish between tools that are meant to tighten market conditions or to loosen them.Footnote 11 Second, several tools can be set to a non-zero value without affecting the market.Footnote 12 Third, the estimation period might just be too short on active macroprudential measures for the estimate to be robust. Most of the macroprudential policy measures took place only after the adoption of Basel III accords in 2010.Footnote 13

Interestingly, if we account for the direction of the (macro)prudential policy measures by applying the \({PPI}_{i,t}\), the offsetting effect disappears (columns 4, 5 and 6). Carefully employed and targeted (macro)prudential policy measures have the potential to generate benefits for the economy by reducing systemic risk and lowering the probabilities of crises, thus improving financial stability. Financial instability has been found to decrease economic growth (Jarrow 2014; Creel et al. 2015; Prochniak and Wasiak 2017; Balta and Vašíček 2020) so the growing role of (macro)prudential policy is expected to contribute to faster economic growth rather than diminishing it. Multiple estimates of the interaction term \(\left({FDI}_{i,t}{\times PPI}_{i,t}\right)\) suggest that the positive finance-growth nexus can be substantially strengthen by an active use of (macro)prudential policy.

4.2 Asymmetric effects of (macro)prudential policy measures

Next, we estimate the augmented model while accounting for the extent to which (macro)prudential policy is tightening or loosening over the period analysed. In this exercise, we use information from \({PPI}_{i,t}\) which measures the direction of the (macro)prudential policy changes. This helps us to verify whether the tightening or loosening of the macroprudential policy might impact economic growth and the finance-growth nexus in an asymmetric fashion. Results are summarized in Table 3. Two main conclusions can be drawn from these additional estimates.

First, (macro)prudential policy aimed at tightening of the financial sector is found to increase economic growth. Within our sample, a one standard deviation increase in \(\left({PPI}_{i,t}\right)\) would be associated with a 0.5 pp increase in economic growth when averaging different estimates from columns 1, 2 and 3. This shows that active (macro)prudential policy is good for the economy if it succeeds in limiting excess credit growth and mitigating systemic risk. Therefore, it should be actively implemented to restrict possible disruptions at the financial sector. Compared with other public policies, (macro)prudential measures benefits from smaller implementation lags and the possibility to tailor the policy instruments to specific risks without causing a generalised reduction in economic growth and limiting the costs of policy intervention. In turn, (macro)prudential policy easing is found to have no statistically significant effect on economic growth.Footnote 14

Second, the amplification effects of active (macro)prudential policy on the finance-growth nexus are found to be driven by tightening, not easing. This shows that the positive finance-growth nexus is stronger in economies where (macro)prudential policy is actively used to curb down excess credit growth and mitigate systemic risk.

4.3 Differentiating between capital- and borrower-based measures

Next, we check whether the documented impact of macroprudential policy on the finance-growth nexus differs with respect to the type of policy in question. Specifically, we divide the policy actions as they appear in the \({PPI}_{it}\) into capital-based and borrower-based. While both, capital- and borrower-based measures aim to strengthen the resilience of the banking system and reduce the potential for imbalances to accumulate, they are different in terms of the targeted entity. Borrower-based measures are applied almost exclusively to bank loans and are directly restricting the amount of credit available to the private sector. This is in contrast to the capital-based measures which are usually designed in a way that affects bank capitalization. For instance, Cerutti et al. (2017a) and Fendoğlu (2017) document that borrower-based measures are more effective in reducing leverage and credit growth.

Estimates as they appear in Table 4 show that while both capital- and borrower-based measures affect the finance-growth nexus (and confirm our baseline estimates), we document significant differences in the magnitude of the response. Specifically, estimates suggest that the effect of LTV tightening on the finance-growth nexus is about twice the size of the effect of capital-based measures. Despite the lower estimated effect, the identified effect of capital-based measures is positive and sizeable and we attain ourselves to a strand of studies where capital-based measures have significant associations with lower traditional credit growth (Claessens et al. 2013). Additionally, our results echo those of Ampudia et al. (2021) who also find amplified impact of LTV on both output and credit compared to other borrower- and capital-based measures. Araujo et al. (2020) indicate that the stronger impact of borrower-based measures may just be driven by much more intense tightening of these tools compared to others. We cannot argue against this as our data do not allow for measurement of the strength of macroprudential policy tightening or loosening.

4.4 Addressing the endogeneity concerns: a two-stage least square estimation

A potential challenge in estimating the effects of (macro)prudential policy actions is that decisions to take policy actions are based on development of financial conditions whose are closely connected to the real economy. Estimating the joint impact of financial development and (macro)prudential policy on economic growth thus poses an identification challenge. We address the potential sources of endogeneity in several ways. The most important concern is the presence of reverse causality and simultaneity. Specifically, it could be that in periods of economic growth, the risk of overheating in the banking sector increases which forces hand of the (macro)prudential authority. If left uncorrected, the bias could somewhat inflate our estimated parameters, making them the upper bound of the true relationship. To cater for simultaneity, we consider several important right-hand side controls, all lagged by one year. To mitigate (at least partially) the presence of reverse causality, we rely on instrumental variable approach and the GMM estimator. The omitted-variable bias is of lesser concern as we gradually consider multiple right-hand side controls as well as country-fixed effects.

Bearing in mind the disadvantages of the GMM estimator for panels with relatively small number of individuals as described in Roodman (2009) and Bun and Windmeijer (2010), we further consider a two-stage least square approach with a specific instrument for (macro)prudential policy actions introduced in Gadatsch et al. (2018)—the index of macroprudential authority strength to pursue its goal. We assume that (macro)prudential policy measures are more likely to be taken if the central bank plays a leading role in the decision-making process. This claim has support in the literature. For instance, Lim et al. (2013), Masciandaro and Volpicella (2016) and Bengtsson (2020) find that a larger role of the central bank in macroprudential policy decision-making process leads to a speedier application of policy measures. To quantify the strength of macroprudential authority, we create an index which we term \({INST}_{i,t}\) for each country in our sample. The \({INST}_{it}\) values lie within a 0,1 interval, depending on whether the country’s institutional arrangement full-fill the criteriaFootnote 15 set by ESRB (2011). ESRB (2014) in a follow-up report has already assessed quantitatively to which degree member states have fulfilled this recommendation. Further details on the construction of \(INST\) are provided in “Appendix 5”.

We estimate the following two-stage least squares panel model:

First stage:

Second stage:

where the previously defined terms are the same, \({\widehat{PPI}}_{i,t}\) represents the instrumented (macro)prudential policy index, \({\delta }_{i}\) and \({\vartheta }_{t}\) are country- and year-fixed effects. Since we employ year-fixed effect, we do not employ the \({crisis}_{it}\) dummy in the 2SLS model.

Table 5 shows the estimated first stage regression. Our instrument \({INST}_{it}\) enters significantly with a positive sign at a 1% or 5% confidence level. The estimated parameter shows that country in which the macroprudential authority has more strength to purse its objective of financial stability has more instruments in place and its (macro)prudential policy is tighter. Since majority of (macro)prudential actions in our sample has been of a tightening nature, the positive sign was expected. Overall, we claim that we have a strong instrument in hand and proceed with the IV estimation.

Table 6 shows our second stage IV results which largely confirm our baseline estimated as they appear in Table 3. A one standard deviation increase in \({PPI}_{it}\) is found to be associated with about 0.32 pp increase in economic growth as a result of financial development when averaging estimates from columns 1, 2 and 3. The reported increase from the baseline model estimated via GMM estimator was 0.5 pp. The reduction in parameter size could be the outcome of better accounting for the endogeneity bias—which works upwards in our case—with the 2SLS estimation and a new instrument. We also confirm our prior finding that the positive effect of active (macro)prudential policy on the finance-growth nexus works through tightening of the policy.

5 Robustness checks

In this section, we demonstrate that our base results that (macro)prudential policy significantly affects the finance-growth nexus are quite robust. First, one might be concerned about the medium-term effects of (macro)prudential policy measures, as our model is contemporaneous, looking at the immediate effect. Part of this concern might be mitigated by the fact that we use annual data. Nevertheless, we conduct two robustness checks to address this potential issue. One, we introduce a richer lag structure into the regression specification. We employ up to 5 lags of the interaction term (\(FD{I}_{i,t} \times MP{P}_{i,t}\)) and its components. The results are displayed in Table 11. Allowing for a richer lag structure delivers estimates that are not statistically different from zero, showing that our original contemporaneous model is appropriate. Second, we follow Agénor et al. (2018) and consider model with computed non-overlapping three-period averages (Table 7). By doing so, we can properly distinguish growth from business cycle effects as well as mitigate reverse causality concerns.

Second, we show that our estimates are largely robust to a wide variety of sample perturbations (Table 12). For each sample perturbation, we report the point estimate for the coefficient of interest, the interaction term (\(FD{I}_{i,t} \times MP{P}_{i,t}\)), for the six specifications of the augmented model in Table 2. As is apparent, the point estimate is robust to a large proportion of the permutations, but not to all of them. First, we drop the control variables one at a time. It can be seen that our results remain largely unchanged following the removal of the controls. If anything, we report stronger estimates following the removal of \(MC{I}_{i,t-1}\), which is reassuring, as it indicates that monetary policy actions are not driving our results. We next drop outlier observations, which are identified as those with residuals more than two standard deviations above or below the average. Last, we drop Luxembourg and Ireland from the sample. Luxembourg, despite its geographical size, is a European financial centre and forms an outlier of its own in most of the variable categories. Ireland’s GDP data was subject to many unusual factors over the 2015–2017 period, making it a natural candidate for our sensitivity exercise (FitzGerald 2015). Our results for both sample perturbations remain significant at least at the 10% level.

Last, we test the robustness of our results to yet another change in estimator. Specifically, we re-estimate both, the baseline model from Table 1 as well as the augmented baseline model from Table 2 using the bootstrap-based bias-corrected (BBBC) estimator proposed by De Vos et al. (2015). This is to verify that the instrumental variable technique does not lead to poor small-sample properties (Kiviet 1995; Bun and Windmeijer 2010). The results are shown in Tables 13 and 14 in the Appendix. Based on the estimated coefficients, it seems safe to say that our findings are not prone to the weak instrument problem.

6 Conclusion

We document that the finance-growth nexus is significantly affected by active use of various (macro)prudential policy measures. We find that (macro)prudential policies support the positive finance-growth nexus instead of disrupting it. In other words, economies with (macro)prudential policy that is actively used to prevent the occurrence of a credit boom and to limit systemic risk tend to benefit from financial development more than economies where (macro)prudential policy is inactive. This only becomes evident when we consider the direction of (macro)prudential policy measures instead of relying on mere frequency of use in the form of a cumulative index.

The reported evidence echoes the research implying that there is a non-monotone (inverted U-shape) relationship between financial development and economic performance. Empirical studies find that more finance is only good up to a certain point, after which it starts to worsen the socio-economic outcomes (see Cecchetti and Kharroubi 2019; Čihák and Sahay 2020 and Gaffeo and Garalova 2014 for European evidence). This is linked to the growing body of literature doubting the usefulness of the financial sector. Several studies point to the increasing costs of financial intermediation (French 2008; Philippon and Reshef 2012; Bivens and Mishel 2013), while others warn against the ever rising riskiness of the financial sector (Bai et al. 2016; Bell and Hindmoor 2018) and the growing costs of financial imbalances (Jordà et al. 2011). Yet, (macro)prudential policy and its pre-emptive nature is rarely discussed or considered in the theoretical model setups or empirical frameworks even though it has the potential to limit the costs associated with a growing financial sector. In this regard, we offer one of the first empirical estimates of how (macro)prudential policy can affect the finance-growth nexus.

We also contribute to the literature that argues that it is not ‘too much finance’ but rather ‘quantity versus quality of finance’ that matters. This literature finds that while quality of finance is conducive to economic growth, the effect of quantity of finance on growth is indeterminable, ranging from positive to negative or zero (Koetter and Wedow 2010; Hasan et al. 2018).

At the EU level, Romero-Ávila (2007) show that the harmonization of the law concerning the banking sector benefited economic growth by increasing the efficiency of financial intermediation. Using EU sample, Creel et al. (2015) find that financial depth does not have a positive effect in the euro area. Creel et al. highlight, among other, the need to incorporate assessment of the regulatory and policy tools that policymakers can and will use in order to tackle the effect of financial instability in the future research. We offer EA-based empirical evidence to fill this gap. We complement international evidence on the effect of macroprudential policies on the link between economic growth on one side and financial innovation (Bernier and Plouffe 2019) and financial openness (Agénor et al. 2018) on the other.

What remains unclear is the effect of advances in non-bank financial intermediation on the finance-growth nexus. This is where the role of (macro)prudential policy in fostering benefits from finance to economic growth might be limited. This is because so-called shadow entities are typically less regulated than their bank counterparts (Plantin 2015; Hodula et al. 2020). From a policy perspective, it may be important to examine the extent to which the growing importance of shadow banking activities might weaken the effectiveness of the regulatory activities of central banks and national regulators, at both national and international level.

As a final note, let us briefly discuss the caveats associated with the analysis of the (macro)prudential policy effects. First, while we control extensively for reverse causality, we might not have been completely successful. This would imply that countries experiencing faster economic growth react by adopting (macro)prudential policies more frequently. If this is the case, our parameter estimates could be overvalued. Second, while we did account for the direction of the (macro)prudential policy measures, we did not account for their intensity. This particular caveat is inherently associated with the existing data limitations and constitutes a promising avenue for future research in this area.

Notes

Bekaert and Popov (2019) argue in favour of using rolling windows to compute average GDP growth over a given period (typically three to five years). This is to correct for relative heterogeneity of sample countries. Given that our sample is a relatively homogeneous monetary union, we pursue our analysis using annual growth rates, but we use the averages in our robustness check section.

Note that for both indexes, we assign the same weights to the different measures. This allows us to investigate the overall effectiveness of (macro)prudential tools.

The capital-based measures are limits on domestic and foreign currency loans, time-varying/dynamic loan-loss provisioning, reserve requirements, limits on interbank exposures, concentration limits, capital requirements, capital buffers, leverage ratio and capital surcharge on SIFIs,

In both indexes, loan-to-value ratio limit is the only borrower-based (macro)prudential instrument.

The instruments used in the System-GMM regression are lagged levels (two periods) of the dependent variable. For the level equation the instruments are the lagged differences (one period). The exogenous covariates and the crisis dummy are instrumented by themselves in the differenced and level equations.

The control variables were chosen in line with previous studies on the finance-growth nexus. For a detailed overview of the use of control variables in such studies, please refer to the dataset of the meta-analysis by Biljsma et al. (2017).

The MCI combines 14 different variables in four categories, namely interest rates, monetary aggregates, balance sheet items and the exchange rate. This enables us to capture the effects of both conventional and unconventional monetary policies, which is essential in the post-crisis period. For details on the calculation of the MCI, please refer to Malovana and Frait (2017) and the "Appendix 2".

In this case, a reverse causality would imply a situation where faster economic growth would lead to greater use of (macro)prudential policies. In fact, it also motivates the use of GVA growth side by side with GDP and GDPPC growth. GVA corrects for excess growth just on account of increased tax collection due to better compliance/coverage.

For example, several countries argue that the counter-cyclical capital buffer should be set at non-zero value for a normal risk environment (ESRB, 2020b).

The original macroprudential policy index of Cerutti et al. (2017b) ends in 2014.

Our findings are in line with Agénor et al. (2018) who also find a positive effect of (macro)prudential tightening on economic growth of around 0.7 pp.

For example, the Czech Republic is graded 1 (fully compliant), as the central bank (CB) is the macroprudential authority. On the other hand, countries like Finland are graded 0.25 (materially non-compliant), because a financial stability authority separate to the CB is tasked with macroprudential policy.

References

Abiad A, Balakrishnan R, Brooks PK, Leigh D (2009) What’s the damage? Medium-term output dynamics after banking crises, IMF Working Paper No. 09/245, International Monetary Fund

Agénor P-R, Gambacorta L, Kharroubi E, Pereira da Silva LA (2018) The effects of prudential regulation, financial development and financial openness on economic growth, BIS Working Papers No 752, Bank for International Settlements

Aiyar S, Calomiris CW, Wieladek T (2014) Does macro-prudential regulation leak? Evidence from a UK policy experiment. J Money Credit Bank 46(s1):181–214

Akinci O, Olmstead-Rumsey J (2018) How effective are macroprudential policies? An empirical investigation. J Financ Intermed 33:33–57

Ampudia M, Lo Duca M, Farkas M, Perez-Quiros G, Rünstler G, Tereanu E (2021) On the effectiveness of macroprudential policy. ECB Working Paper No. 2559, European Central Bank

Araujo JD, Patnam M, Popescu MA, Valencia MF, Yao W (2020) Effects of macroprudential policy: evidence from over 6,000 estimates. IMF Working Paper No.20/67, International Monetary Fund

Arcand JL, Berkes E, Panizza U (2015) Too much finance? J Econ Growth 20(2):105–148

Arestis P, Chortareas G, Magkonis G (2015) The financial development and growth nexus: a meta-analysis. J Econ Surv 29(3):549–565

Bagehot W (1873) Lombard street: a description of the money market. HS King&Company

Bai J, Philippon T, Savov A (2016) Have financial markets become more informative? J Financ Econ 122(3):625–654

Ball L (2014) Long-term damage from the great recession in OECD countries. Eur J Econ Econ Policies: Interv 11(2):149–160

Balta N, Vašíček B (2020) Financial channels and economic activity in the euro area: a large-scale Bayesian VAR approach. Empirica 47(2):431–451

Beck T, Degryse H, Kneer C (2014) Is more finance better? Disentangling intermediation and size effects of financial systems. J Financ Stab 10:50–64

Bekaert G, Popov A (2019) On the Link between the Volatility and Skewness of Growth. IMF Econ Rev 67(4):746–790

Bell S, Hindmoor A (2018) Are the major global banks now safer? Structural continuities and change in banking and finance since the 2008 crisis. Rev Int Poli Econ 25(1):1–27

Bengtsson E (2020) Macroprudential policy in the EU: a political economy perspective. Glob Financ J 46:100490.

Bernier M, Plouffe M (2019) Financial innovation, economic growth, and the consequences of macroprudential policies. Res Econ 73(2):162–173

Bianchi J, Mendoza EG (2018) Optimal time-consistent macroprudential policy. J Polit Econ 126(2):588–634

Biljsma M, Cool K, Non M (2017) The effect of financial development on economic growth: a meta-analysis, CPB Discussion Paper No 340, CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis

Bivens J, Mishel L (2013) The pay of corporate executives and financial professionals as evidence of rents in top 1 percent incomes. J Econ Perspect 27(3):57–78

Blackburn K, Hung VT (1998) A theory of growth, financial development and trade. Economica 65(257):107–124

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econ 87(1):115–143

Boar C, Gambacorta L, Lombardo G, Pereira da Silva LA (2017) What are the effects of macroprudential policies on macroeconomic performance? BIS Q Rev Sept

Budnik KB, Kleibl J (2018) Macroprudential Regulation in the European Union in 1995–2014: Introducing a New Data Set on Policy Actions of a Macroprudential Nature, ECB Working Paper No 2123, European Central Bank

Bun MJG, Windmeijer F (2010) The weak instrument problem of the system GMM estimator in dynamic panel data models. Economet J 13(1):95–126

Caprio G Jr, D’Apice V, Ferri G, Puopolo GW (2014) Macro-financial determinants of the great financial crisis: Implications for financial regulation’. J Bank Financ 44:114–129

Cecchetti SG, Kharroubi E (2012) Reassessing the impact of finance on growth (No. 381). BIS Working Papers No 381, Bank for International Settlements

Cecchetti SG, Kharroubi E (2019) Why does credit growth crowd out real economic growth? Manch Sch 87:1–28

Cerra V, Saxena SC (2008) Growth dynamics: the myth of economic recovery. Am Econ Rev 98(1):439–457

Cerutti E, Claessens S, Laeven L (2017a) The use and effectiveness of macroprudential policies: new evidence. J Financ Stab 28:203–224

Cerutti E, Correa R, Fiorentino E, Segalla E (2017b) Changes in prudential policy instruments—a new cross-country database. Int J Cent Bank 13(1):477–503

Claessens S, Ghosh SR, Mihet R (2013) Macro-prudential policies to mitigate financial system vulnerabilities. J Int Money Financ 39:153–185

Creel J, Hubert P, Labondance F (2015) Financial stability and economic performance. Econ Model 48:25–40

Čihák M, Sahay R (2020) Finance and Inequality, IMF Staff Discussion Notes 20/01, International Monetary Fund

De Vos I, Everaert G, Ruyssen I (2015) Bootstrap-based bias correction and inference for dynamic panels with fixed effects. Stand Genomic Sci 15(4):986–1018

Deli YD, Hasan I (2017) Real effects of bank capital regulations: global evidence. J Bank Financ 82:217–228

ESRB (2011) Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board of 22 December 2011 on the Macro-prudential Mandate of National Authorities. ESRB/2011/3, European Systemic Risk Board

ESRB (2014) Recommendation on the Macro-Prudential Mandate of National Authorities (ESRB/2011/3), Follow-up Report—Overall assessment, ESRB/2011/3, European Systemic Risk Board

ESRB (2016) A Review of Macro-prudential Policy in the EU in 2015. European Systemic Risk Board, Frankfurt am Main

ESRB (2020) Overview of National Macroprudential Measures. www.esrb.europa.eu/national_policy/shared/pdf/esrb.measures_overview_macroprudential_measures.xlsx.

Fidrmuc J, Lind R (2020) Macroeconomic impact of basel III: evidence from a meta-analysis. J Bank Financ 112(C)

Fendoğlu S (2017) Credit cycles and capital flows: Effectiveness of the macroprudential policy framework in emerging market economies. J Bank Financ 79:110–128

FitzGerald J (2015) Problems interpreting national accounts in a globalised economy- ireland, quarterly economic commentary: special articles. Economic & Social Research Institute

French KR (2008) Presidential address: the cost of active investing. J Financ 63(4):1537–1573

Gadatsch N, Mann L, Schnabel I (2018) A new IV approach for estimating the efficacy of macroprudential measures. Econ Lett 168:107–109

Gaffeo E, Garalova P (2014) On the finance-growth nexus: additional evidence from Central and Eastern Europe countries. Econ Chang Restruct 47(2):89–115

Galati G, Moessner R (2013) Macroprudential policy—a literature review. J Econ Surv 27(5):846–878

Goldsmith RW (1969) Financial Structure and Development. Yale University Press

Gurley JG, Shaw ES (1967) Financial structure and economic development. Econ Dev Cult Change 15(3):257–268

Hasan I, Horvath R, Mares J (2018) What type of finance matters for growth? Bayesian model averaging evidence. World Bank Econ Rev 32(2):383–409

Hodula M, Melecky A, Machacek M (2020) Off the radar: factors behind the growth of shadow banking in Europe. Econ Syst 44(3):100808

Jarrow RA (2014) Financial crises and economic growth. Q Rev Econ Financ 54(2):194–207

Jordà O, Schularick MH, Taylor AM (2011) When credit bites back: leverage. Business Cycles, and Crises, NBER Working Papers No. 17621, National Bureau of Economic Research

Jung WS (1986) Financial development and economic growth: international evidence. Econ Dev Cult Change 34(2):333–346

Khan A (2001) Financial development and economic growth. Macroecon Dyn 5(3):413–433

King RG, Levine R (1993) Finance and growth: Schumpeter might be right. Q J Econ 108(3):717–737

Kiviet JF (1995) On bias, inconsistency, and efficiency of various estimators in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 68(1):53–78

Koetter M, Wedow M (2010) Finance and growth in a bank-based economy: is it quantity or quality that matters? J Int Money Financ 29(8):1529–1545

Kolcunová D, Malovaná S (2019) The Effect of higher capital requirements on bank lending: the capital surplus matters. CNB Working Paper 2/2019, Czech National Bank

Levine R, Loayza N, Beck T (2000) Financial intermediation and growth: causality and causes. J Monet Econ 46(1):31–77

Lim CH, Krznar MI, Lipinsky MF, Otani MA, Wu MX (2013) The macroprudential framework: policy responsiveness and institutional arrangements. IMF Working Paper No. 13/166, International Monetary Fund

Lo Duca M, Koban A, Basten M, Bengtsson E, Klaus B, Kusmierczyk P, Lang JH (2017) A new database for financial crises in European Countries, ESRB Occassional Paper Series No. 13, European Systemic Risk Board

Loayza NV, Ranciere R (2006) Financial development, financial fragility, and growth. J Money Credit Bank 1051–1076

Malovana S, Frait J (2017) Monetary policy and macroprudential policy: rivals or teammates? J Financ Stab 32:1–16

Masciandaro D, Volpicella A (2016) Macro prudential governance and central banks: facts and drivers. J Int Money Financ 61:101–119

McKinnon RI (1973) Money and Capital in Economic Development. Brookings Institution

Mendoza EG, Quadrini V, Rios-Rull JV (2009) Financial integration, financial development, and global imbalances. J Polit Econ 117(3):371–416

Patrick HT (1966) Financial development and economic growth in underdeveloped countries. Econ Dev Cult Change 14(2):174–189

Philippon T, Reshef A (2012) Wages and human capital in the US finance industry: 1909–2006. Q J Econ 127(4):1551–1609

Plantin G (2015) Shadow banking and bank capital regulation. Rev Financ Stud 28(1):146–175

Prochniak M, Wasiak K (2017) The impact of the financial system on economic growth in the context of the global crisis: empirical evidence for the EU and OECD countries. Empirica 44(2):295

Reinhart CM, Rogoff KS (2008) This time is different: a panoramic view of eight centuries of financial crises. NBER Working Paper No. 13882, National Bureau of Economic Research

Rioja F, Valev N (2004) Does one size fit all?: A reexamination of the finance and growth relationship. J Dev Econ 74(2):429–447

Romero-Ávila D (2007) Finance and growth in the EU: new evidence from the harmonisation of the banking industry. J Bank Finance 31(7):1937–1954

Roodman D (2009) How to do xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in stata. Stand Genomic Sci 9(1):86–136

Rousseau PL, Wachtel P (2011) What is happening to the impact of financial deepening on economic growth? Econ Inq 49(1):276–288

Sánchez AC, Röhn O (2016) How do policies influence GDP tail Risks? OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1339, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Schumpeter JA (1952) Theorie der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung: Eine Untersuchung über Unternehmergewinn, Kapital, Kredit, Zins und den Konjunkturzyklus

Smets F (2014) Financial stability and monetary policy: how closely interlinked? Int J Cent Bank 10(2):263–300

Svirydzenka K (2016) Introducing a new broad-based index of financial development. IMF Working Paper No. 16/05, International Monetary Fund

Valickova P, Havranek T, Horvath R (2015) Financial development and economic growth: a meta-analysis. J Econ Surv 29(3):506–526

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank two anonymous referees for valuable comments. We are gratefull to Simona Malovaná, Michal Franta, Roman Horváth, Jan Frait, Zuzana Rakovská, Jan Libich, Lukáš Pfeifer, Jiří Gregor and Peter Molnár for comments on an earlier version of the paper. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Czech National Bank or its management.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the Technical University of Ostrava Grant SP2020/110 and the project APVV under Grant APVV-20–0499. Ngoc Anh Ngo declares that this paper has been elaborated in the framework of the grant programme "Support for Science and Research in the Moravian-Silesian Region 2021" (RRC/10/2021), financed from the budget of the Moravian-Silesian Region.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Jesus Crespo Cuaresma.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Appendix 1: Data

In order to provide more information, Table 8 reports all our variables, their summary statistics and their data sources.

1.2 Appendix 2: Monetary conditions index estimation procedure

There are a number of approaches that allow a large number of time series to be combined into a single composite index. In the case of the indicator presented in this paper, we use a factor model estimate. Consider an n-dimensional vector of stationary observable variables \(X={\left({X}_{1},\dots ,{X}_{n}\right)}^{^{\prime}}\) that are linearly dependent on an m-dimensional vector of originally unobservable factors \(F=\left({F}_{1},\dots ,{F}_{m}\right)\). The baseline factor model then takes the following form:

where \(\Lambda\) is a matrix of factor loadings, \({A}_{i}\) is a matrix of autoregression coefficients for \(p\) lags and \({\varepsilon }_{t},{u}_{t}\) are i.i.d. Gaussian error terms. We use the maximum likelihood method to estimate the factor model. While more complicated to calculate, the maximum likelihood method, unlike the principal components method, makes it possible to test whether the number of common factors selected is sufficient. The optimal number of factors to estimate is primarily based on parallel analysis. The optimal number of lags is chosen based on the Schwarz information criterion. For our data, results of statistical tests prefer a factor model with 3 estimated factors and 1 lag. The robustness and sensitivity analysis of the selected model specification to calculate MCI was performed with respect to the number of lags used, number of factors estimated, the estimation period, and the variables included in the estimation.

Table 9 summarizes the set of 15 variables that reflect the monetary conditions in the euro area. Variables in respective blocks were treated as follows: (1) interest rates enter the estimation in levels; (2) monetary aggregates are expressed in year-on-year change and in reciprocal values (switched sign) so that that an increase would correspond to a monetary tightening, as for interest rates; (3) ECB balance sheet items are expressed in year-on year change with a negative sign for all these variables; and (4) exchange rate is transformed into a year-on-year change with the sign left unchanged.

To save space, we do not report all the robustness checks performed; they are available upon request. Figure

4 (left-hand graph) shows the relative contribution of each of the estimated factors to the final index. The figure also plots the MCI as normalized using the mean and standard deviation of the 3-month EURIBOR. The right-hand graph shows results of a simulation exercise in which the index was estimated multiple times, each time with one variable excluded from the input data set. This approach is very similar to a more formal bootstrapping proposed by Gospodinov and Ng (2013).

1.3 Appendix 3: Dating of financial crises in the Euro area

In identifying crisis-type events, we rely on a financial crises database for European countries maintained by the ESRB. The dates, presented in Table 10, were selected by the ESRB based on a quantitative identification approach, which had been cross-checked with expert judgement from national and European authorities (qualitative approach). This expert judgement was sought by the ESRB whenever the adopted quantitative approach did not identify event dates included in Laeven and Valencia (2013) and Babecky et al. (2014). In such cases, the dates were submitted to national authorities for revision in order to assess the most appropriate dates to be included in the dataset.

1.4 Appendix 4: Additional estimates

Section 4 discussed several additional empirical specifications. Results are reported below in Tables 11, 12, 13. The first reports estimates of the interaction term from Eq. 2 using richer lag structure. The second contains estimates of the interaction term from Eq. 2 for various sample perturbations. The final table reports the estimates of the model as specified in Eq. 2 using alternative estimator (Table 14).

1.5 Appendix 5: The index of macroprudential authority strength

We use the ESRB (2014) assessment of the implementation of the ESRB's Recommendation on the macro-prudential mandate of national authorities to set up a macroprudential authority strength index. In 2014, the ESRB evaluated the degree to which EU member states are compliment with the Recommendation. We are interested in the assessment related to the Sub-recommendation B.3. which requires that the central bank plays a leading role in macro-prudential policy, given their institutional and functional strengths.

Table 15 summarizes the extent of the central bank’s role in the macro-prudential policy of individual countries. The ESRB grades countries according to their efforts to implement the ESRB Recommendation on a zero to one scale (0 = Non-compliant; Materially non-compliant = 0.25; 0.5 = Partially compliant; 0.75 = Largely compliant; 1 = Fully compliant). Table 16 show the standards as set by the ESRB regarding grading the Sub-recommendation B.3.

Figure 5 shows the index values for our sample countries. Since the ESRB performed its assessment in 2014, we re-do the assessment for 2017 to check for any changes in the institutional setup.

Source: ESRB (2014); assessment for the year 2017 was performed by the authors

Overview of \(INS{T}_{i,t}\) Values for the Sample of Countries.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hodula, M., Ngo, N.A. Finance, growth and (macro)prudential policy: European evidence. Empirica 49, 537–571 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-022-09537-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-022-09537-w