Abstract

In the contemporary arena of e-commerce strategies, companies are increasingly drawn to the use of referral program incentives to prompt existing customers to recruit new ones. However, the existing knowledge falls short of unraveling the intricate dynamics governing the sharing of diverse rewards in company-consumer and consumer-consumer relationships. This study bridges this gap by unveiling a nuanced connection between the effectiveness of referral rewards and the interplay of both the recipient’s propensity to refer during the referral stage and the recipient’s inclination to accept during the acceptance stage. Through three scenario-based experiments, we explore the influence of the consumer-company relationship on individuals’ willingness to engage in referrals during the referral stage, identifying two pivotal psychological mechanisms: economic and social motivation. Our findings underscore those selfish incentives, primarily benefiting the sender, outperform prosocial incentives, particularly within exchange norms, yet reveal the reputational advantages associated with prosocial referral rewards in communal norms. Shifting the focus to the acceptance stage, we scrutinize the relationship between the referrer and the recipient, discovering that sender-benefiting rewards may undermine a recipient’s acceptance due to negative motivational inferences, yet this effect can be moderated by relationship norms. Our findings offer a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted role played by referral rewards in shaping consumer behavior within social e-commerce, providing valuable guidance for companies seeking to optimize their referral strategies by aligning rewards with relationship norms to enhance overall effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the evolving paradigm of social e-commerce, it has gained global prominence by seamlessly integrating social media with online shopping. This innovative approach empowers users to engage in shopping, share experiences, and conduct transactions on platforms, thereby facilitating product discovery, seeking advice, and enhancing brand engagement. To diversify revenue streams, cater to user needs, and expand their user base, an increasing number of social media platforms are embracing social e-commerce. For instance, Instagram has elevated the shopping experience through the strategic use of hashtags and the introduction of dedicated stores. TikTok, on the other hand, has emerged as a platform for showcasing and selling products through engaging videos. Meanwhile, Facebook’s Marketplace has undergone substantial enhancements to bolster e-commerce and social shopping experiences [1]. This phenomenon has piqued mounting interest from both researchers and practitioners.

In essence, consumers actively share news with their social connections daily, driven by motivations such as interest, assistance, or personal benefit [2]. These sharing behaviors manifest as either “free” or “paid,” with companies implementing Reward Referral Programs (RRPs) to incentivize current customers (referrers) to recommend their product information to others (recipients) [3]. While RRPs lead to acquiring new customers and sales, they also incur increased costs for companies [4]. Referrers engage in rewarded referrals for benefits, occasionally sharing product information even without a reward [5]. For recipients, obtaining a reward or aiding others in receiving one increases the behavioral cost, requiring them to sign up for memberships or perform additional actions to activate the referral [6]. Moreover, the presence of rewards may instill skepticism in recipients regarding the credibility and authenticity of the referrer [7]. Hence, a comprehensive understanding of people’s motivations and the psychological underpinnings of rewarded referral is pivotal for both theoretical advancement and practical applications. Thus motivated, this study proposes three key research questions: (1) What motivates consumer refer behavior in social e-commerce? (2) How do people’s referral and acceptance of different rewards vary based on the relationship between the company and individuals, as well as among individuals and their relationships? (3) What factors contribute to the success of reward referral?

Importantly, the motivation behind individuals referring company information is primarily rooted in self-interest, driven by the fundamental instinct of biological survival [8]. Extensive studies, including research by Imas (2014), support this assertion [9]. Some scholars argue that self-interested rewards often carry greater influence than altruistic ones [10], emphasizing the potency of economic motivation when individuals anticipate financial gains or rewards [11]. Simultaneously, human behavior is shaped by social motivation, fostering acts of aid, support, and altruism [12]. Glazer and Konrad (1996) discuss how the reputational benefits of altruistic behaviors lead to more generous actions such as donating and helping [13]. Research by Gershon et al. (2020) demonstrates that altruistic rewards (i.e., recipient-benefiting) can be as motivating as self-interested rewards (i.e., sender-benefiting) in customer referrals within social circles [14]. However, there is limited existing research providing insight into systematic differences between consumers’ altruistic and self-interested motivations in rewarding referrals. In practice, companies offer a variety of rewards that benefit the referrer to stimulate referring behavior. At the same time, there are companies that communicate to consumers that through their referring, their friends will benefit. In light of this, there is a need to further explore and understand the impact of different types of rewards (benefiting the referrer and benefiting their friends) on consumer behavior.

While individuals generally prioritize self-interested rewards benefiting themselves, there’s a propensity to also engage in referring altruistic rewards to help a friend [15]. It has been demonstrated that person-to-person relationship characteristics can be applied similarly to relationships with both people and companies [16]. Understanding the complex interplay between companies and individuals, as well as interpersonal relationships, is crucial. Consumer-company interactions establish diverse relationships that shape consumer engagement criteria and responses to company conduct [17]. We predict that individuals maintaining exchange relationships with companies will likely prioritize self-interest, whereas those fostering communal relationships might demonstrate a stronger inclination toward altruism. Correspondingly, consumers engaged in exchange relationships may exhibit behaviors driven by self-interest, while those involved in communal relationships could lean towards more helpful behaviors. Our study integrates these relational norms into reward referral, providing insights into their impact on consumer behavior in both company-consumer interactions and interpersonal dynamics, influencing the likelihood of referring and accepting various reward types.

For a successful reward referral program, the key lies not only in the referrer referring company information but also in the recipient’s willingness to accept and take action (such as signing up as a new user or making a purchase). While numerous studies have delved into consumers’ behaviors regarding referral and rewards in social e-commerce, they have often examined these aspects separately [18]. Fewer studies have simultaneously explored both the willingness of referrers and recipients to refer and accept. Building on Gershon’s (2020) examination of the effectiveness of pro-social incentives by dividing rewards into two stages—referrals and acceptance—we will explore the motivation and psychological logic behind consumers’ recommendation and acceptance of different reward types across different relationship norms during both stages [14].

To advance this line of research, this paper presents findings from three meticulously conducted scenario-based experiments exploring the influence of referral reward programs on both the likelihood of making referrals and the acceptance of such referrals. In our study, we investigate how consumer-company relationship norms impact consumers’ inclination to recommend various reward types during the referrals stage (Study 1). Study 2 utilizes different participants to validate the effect of consumer-company relationship norms and reward types on consumers’ willingness to refer during the referrals stage, while also revealing mediating mechanisms. Finally, Study 3 delves into how these norms shape the willingness to accept different reward types and their mediating mechanisms from the recipient’s perspective during the acceptance stage.

This paper significantly contributes to the existing literature on rewarding referrals. We conduct an extensive review of Referral Reward Programs (RRPs), highlighting crucial determinants for their success. We stress their reliance not just on current users’ willingness to initiate referrals [19], but also on prospective users’ openness to accepting these referrals [20]. While previous research has deeply explored the influencing mechanisms on both referrers’ and recipients’ behavioral intentions, there’s a noticeable void in understanding their cohesive behavior as a unified entity. In an effort to address this gap, our study examines the combined impacts of diverse referral rewards on both the referral stage and the acceptance stage. Additionally, inspired by Gershon’s (2020) work, we frame pro-social rewards (recipient-benefiting) and self-interested rewards (sender-benefiting) within a research framework [14]. We explore how sender-benefiting and recipient-benefiting incentives shape consumers’ referral behavior at distinct stages. Furthermore, our research advances relational norms theory. We propose that the efficacy of rewards in referral rewards is contingent upon relational norms between consumers and company, as well as among individuals. Specifically, we hypothesize that sender-benefiting rewards prove more impactful in exchange relationships, while recipient-benefiting rewards gain preference in communal relationships. Understanding the motivation behind referral rewards among friends versus strangers holds both theoretical significance and practical interest. The subsequent sections unfold the theoretical underpinnings, our proposed conceptual model, and the hypotheses guiding our research.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Referral rewards and referral behavior

Rewarding referrals is a strategic approach adopted by companies to encourage individuals to refer their products, services, or brands within their social circles [6]. Typically, this strategy is implemented through a rewards program that leverages existing social relationships to attract new customers [4]. The process involves the referrer initiating the referral, deciding to make the referral, and the recipient deciding whether to become a new customer [21]. Referrers play a pivotal role in these programs, attracting new customers by sharing personal experiences or product knowledge [4]. In rewarded referrals, referrers are incentivized to participate in a referral program that actively promotes a specific product or service within their social circle [22]. For instance, Amazon’s member referral program offers Prime members rewards such as account balances or coupons for successfully inviting new users [23].

On the other hand, recipients play a critical role in determining whether to follow the referrer’s advice on purchasing or using a product or service, significantly influencing the success of the referrals [7]. In practical terms, companies frequently employ reciprocal rewards to incentivize referrers to refer and motivate recipients to accept referrals. For example, Airbnb’s referral program rewards existing users with travel credits or discount coupons for inviting friends to sign up and complete their first booking, while new users also receive discounts. While both parties stand to gain, in practice, the referrer contemplates what they can gain by making a referral, and the recipient considers what they can gain by accepting, with little emphasis on the benefits received by the other party. Simultaneously, this approach may raise questions; when referring with someone unfamiliar, does the knowledge that the other person will also receive a reward lead the recipient to believe that the benefits are being equally shared? Addressing this aspect separately provides a clearer understanding of the psychological motivations behind both referring and accepting behaviors.

Extensive academic research on reward referral exists, primarily concentrating on either the recipient’s or the referrer’s viewpoint (see Appendix A for a comprehensive overview). Gershon (2020) notably introduced recipient-benefiting rewards into referral programs, emphasizing pro-social behavioral aspects and examining their impact on both the sender and the recipient throughout the referral and acceptance stages [14]. In inspiration of Gershon’s groundwork, our study further delves into the intricate ramifications of diverse rewards throughout both the referral and acceptance stages.

2.2 Egotistic or altruistic rewards

Referral rewards, a strategic tool used by companies to stimulate customers in advocating their products or services and disseminating marketing messages, have gained significant attention [4]. The type of reward offered plays a crucial role in influencing a consumer’s willingness to engage in a promotional campaign [20]. Companies often extend invitations for customers to share their ads or promotions, sweetening the deal with a promo code for a discounted subsequent purchase in our day-to-day interactions [24]. Research underscores that self-benefiting behavior is an innate and instinctive inclination requiring less cognitive effort than mutual or altruistic behavior [25]. Consequently, the most effective rewards are those maximizing material payoff for the decision maker, such as sender-benefiting rewards that provide direct financial benefits to the referrer [4]. Individuals exhibit heightened effort when offered sender-benefiting rewards, primarily driven by self-interest [26].

In practice, another intriguing scenario involves consumers actively sharing a company’s ads or promotions without any explicit rewards. For instance, Nike enthusiasts frequently post information about Nike promotions on social media without expecting material returns. Forsythe (1994) reveals that even in the absence of consequences for selfish behavior, people, on average, share about 25% of a given endowment [27]. Enter recipient-benefiting rewards, bestowed upon the recipient of the referral information [14]. In contrast to sender-benefiting rewards, recipient-benefiting rewards do not offer direct financial benefits to the referrer; instead, they confer social recognition and reputation benefits [28]. Offering benefits in a communal relationship becomes a response to another person’s needs without seeking reciprocation, suggesting that people share promotions to help companies and enable others to receive rewards for the reputational benefits it brings [29].

Many retailers adopt a reciprocal reward system, incentivizing both the referrers and recipients. While acknowledging the effectiveness of this approach, we recognize its success may stem from intricate reasons. Firstly, the referrer and the recipient may not be aware of the specific benefit the other receives and therefore will refer and accept if they know they receive a benefit. Secondly, if the other person’s benefits are mentioned, for mutual strangers or unfamiliar friends, the purpose of referring and accepting is still to gain benefits for themselves. If the motivation for referring is to gain a material benefit, then emphasizing that the recipient will also benefit may make it seem as if one’s own benefit is also being shared. Altruistic motives will only be present if there is a stronger relationship between the referrer and recipient. Consequently, we argue that the underlying psychological states behind referring and accepting behaviors differ. This paper deviates from prior studies by dissecting each state individually.

In our current work, we not only scrutinize the willingness to refer and accept but also delve into how it influences the type of rewards (sender-benefiting vs. recipient-benefiting) that are referred and accepted—an aspect hitherto unexplored in referral rewards research.

2.3 Relationship norms in referral rewards

The effectiveness of referral rewards is influenced by several factors, including the appeal of the rewards [30], the relationship between the referrer and the recipient [31], and the perceived social or economic costs associated with the act of referring [7]. Heyman and Ariely (2004) put forth the notion that distinguishing money markets from social markets hinges on returns and forms [32]. In this context, the provision of monetary returns characterizes a money market, adhering to market norms, while the absence of returns or the provision of nonmonetary returns designates a social market, aligning with social norms [33]. Human interactions give rise to diverse relationships, each following distinct norms [34]. Consumer interactions with brands, though not equivalent to human relationships in depth, exhibit relational characteristics [35]. Consequently, relationship norms play a pivotal role in shaping consumers’ perceptions, influencing their evaluations of companies, and guiding their responses to company behavior [36].

Clark (1984) categorized interpersonal relationships as either exchange or communal, contingent upon the rule of benefit giving and receiving [37]. In an exchange relationship, benefits are provided with the expectation of an equivalent financial return, whereas communal relationships involve giving benefits in response to the needs of another party without expecting a return [38]. Building upon this framework, Aggarwal (2004) extended exchange and communal relationship norms to company relationships [35]. Exchange relationships, akin to interactions with strangers and businesses, involve providing benefits with the anticipation of rewards. Communal relationships, reflective of familial, romantic, and friendly connections, entail providing benefits based on another person’s needs and expressing concern for them. The alignment of a company’s marketing behavior with relationship norms is crucial, as positive evaluations by consumers ensue only when both are consistent [39].

In this research, we posit that during the referral stage, the norms of the consumer-company relationship (exchange vs. communal) will significantly influence their inclination to refer different types of rewards (sender-benefiting rewards vs. recipient-benefiting rewards). Building on this premise, we also anticipate that during the acceptance stage, the norms of the consumer-consumer relationship (exchange vs. communal) will similarly shape their willingness to accept different types of rewards (sender-benefiting rewards vs. recipient-benefiting rewards).

3 Conceptual model and research hypotheses

This paper introduces a two-stage research model to scrutinize user behavior within the realm of social e-commerce referrals. In the initial referral stage, we delve into users’ inclination to refer to a social e-commerce platform. Subsequently, in the acceptance stage, our focus shifts to exploring recipients’ willingness to accept referrals. These dual stages collectively underpin the intricated dynamics and success of a social e-commerce referral program.

3.1 The referral stage from the referrer’s perspective

In the first stage of a reward referral, companies provide diverse incentives with the aim of inspiring consumers to kickstart the referral process. The nature of relationships between companies and consumers plays a pivotal role in shaping consumers’ readiness to advocate for specific types of rewards. Consequently, delving into the motivation and rationale behind referral behavior becomes imperative for a comprehensive understanding of this dynamic process.

3.1.1 Interaction between reward types and relationship

Throughout the extensive history of mankind, individuals have navigated an environment marked by limited resources [40]. Consequently, self-interest has emerged as a protective instinct in the face of challenges and competition, evident across diverse life domains, encompassing economic endeavors, social interactions, and various facets of human existence [41]. In the realm of economics, the rational economic man theory posits that individuals will make optimal choices to maximize their self-interest [42]. Even within the bounds of finite rationality, self-interest persists as an automated and unconscious instinct [43]. Referral rewards, involved in the allocation of resources between referrer and recipients, align with people’s self-interested instincts, particularly for referrer who play a central role in referral tasks. Consequently, while recipient-benefiting rewards offer certain advantages, sender-benefiting rewards remain the preferred choice for referrer. Hence, we hypothesize as follows:

H1

Sender-benefiting rewards are more likely to motivate consumers’ willingness to refer than recipient-benefiting rewards.

Beyond the type of reward, the way existing consumers respond to reward referrals is shaped by their relationship with the company. The company’s solicitation for assistance from existing consumers through a reward referral program can be perceived as either a paid service or a favor, depending on the consumer’s relational perception of the company. Exchange norms drive referrals in exchange for financial rewards, while communal norms see referrals as acts of assistance without the expectation of rewards [44]. Moreover, in line with the priming effect, the activated relational norms between consumers and the company also influence how consumers navigate relationships with other consumers [45]. Moreover, rewarded referrals expose recipients to a conflict between market and social norms [46], potentially blurring interaction norms with the recipient. Consequently, referrers handle their relationship with the recipient in accordance with the company’s relational norms. Aligning reward types with relational norms helps consumers clarify exposed norms and guides their behavior accordingly. Sender-benefiting rewards provide direct benefits to the referrer but may involve social or psychological costs, such as profiting from friends [14]. However, in exchange relationships, seeking financial benefits aligns with exchange purposes [47]. Hence, when consumers perceive an exchange relationship with the company, sender-benefiting rewards enhance consumers’ referral inclination compared to recipient-benefiting rewards. Thus, we hypothesized the following:

H2a

When sender-benefiting rewards are offered, a consumer with an exchange relationship is likelier to refer a product than a consumer with a communal relationship.

Recipient-benefiting rewards do not provide direct financial benefits to the referrer; instead, they offer social recognition and reputational benefits [14]. In communal relationships, referrals are seen as helping behavior, often without seeking tangible rewards [48]. The lack of personal economic gain triggers social norms, emphasizing social recognition and adherence to social expectations [49]. Similarly, communal relationships between the referrer and the company foster a communal norm, driving referrals even without economic self-interest. Consequently, consumers in communal relationships are more likely to refer products associated with recipient-benefiting rewards than those with self-benefiting rewards. Hence, we hypothesized the following:

H2b

When recipient-benefiting rewards are offered, a consumer with a communal relationship is likelier to refer a product than a consumer with an exchange relationship.

3.1.2 The mediating role of economic and social motivation

Human behavior is intricately driven by motivation, a pivotal determinant in comprehending individual behavioral choices, and it originates from various stimuli [50]. In the realm of motivation, Grant (2010) categorizes it into intrinsic and extrinsic forms [51]. Intrinsic motivation is characterized by the spontaneous human perception of an activity, inherently related to the activity itself. Conversely, extrinsic motivation propels action due to external rewards, encompassing rewards, monetary gain, honor, and other external inducements [52].

Referral behavior, akin to word-of-mouth practices, involves consumers sharing their personal experiences with potential consumers [53]. Hennig (2004) identified five motive categories underpinning word-of-mouth communication: access to information, social motives, community relationship maintenance, financial incentives, and learning motives [50]. Internal motivation encompasses personal interests, values, and self-fulfillment [54], while external motivation involves rewards or incentives from the outside, such as money, social recognition, or other tangible benefits [31]. Research indicates that internal motivation may prompt individuals to be more inclined to share referrals as they align with their interests or values [55]. Conversely, external motivation may drive increased refer behavior, as individuals seek to attain specific rewards or recognition [49]. Notably, financial rewards emerge as the most common external stimuli propelling users to engage in word-of-mouth referrals [31]. In this dynamic, rewards serve as external stimuli, wielding influence over consumers’ referral behavior [49].

An exchange relationship operates on the premise that benefits are bestowed with the anticipation of reciprocal returns [35]. When referring brand or product information to others, consumers engage in the sharing of their experiences and sentiments, expending time and energy to persuade others—a process incurring energy costs [56]. Grounded in economic exchange theory, which posits that behavioral costs can be offset by economic benefits, providing material rewards to referrers becomes instrumental in stimulating and promoting referring behavior [38]. In daily life, monetary rewards stand out as the most prevalent and effective form of motivation [57]. Whether employed as an incentive for weight loss, vaccination, exercise [58], or as a mechanism to prompt individuals to refer marketing brand messages [59], monetary rewards consistently prove to be a potent motivator [57]. Within the realm of exchange relationships, individuals, prioritizing their self-interests, naturally gravitate towards referring to self-benefiting rewards that offer direct tangible benefits. Consequently, sender-benefiting rewards emerge as a catalyst, increasing referrers’ willingness to advocate a product by stoking their motivation to attain financial benefits. This underpins our hypothesis:

H3a

For consumers who are in an exchange relationship with a company, sender-benefiting rewards can stimulate their economic motivation and increase their willingness to refer.

While it is acknowledged that selfish incentives tend to more effectively motivate effort than their prosocial counterparts [9], Baumeister (1995) underscores that the innate drive to form and sustain relationships is a fundamental aspect of human social behavior [60]. Individuals may make sacrifices at a material level, yet the reciprocity inherent in human interactions often results in social rewards, such as heightened status or respect. Ellingsen and Johannesson (2008) introduced the concept of social motivation, which encompasses behavior driven by social factors like the desire for social acceptance and conformity to social norms [61]. Consequently, reputational rewards become a potent motivator, as individuals harbor a robust desire for social approval [48]. The impetus behind seeking social recognition propels consumers to refer a product within the context of a social e-commerce platform.

Recipient-benefiting rewards yield reputational benefits [14], offering a distinctive avenue for individuals within communal relationships to manifest their sense of responsibility and obligation towards others, devoid of any expectations for reciprocation [35]. Through word-of-mouth communication, consumers actively contribute to companies’ promotional efforts, garnering recognition and praise from their social circles [62]. While this may not result in direct material benefits for referrers, it engenders ancillary advantages, such as the cultivation of a social identity [63]. The act of aiding others through referrals, although lacking immediate material gain, contributes to the accretion of social capital for the referrer, fostering a sense of belonging and the maintenance of close personal relationships [60]. Consequently, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H3b

For consumers in a communal relationship with a company, recipient-benefiting rewards can stimulate social motivation and thus increase their willingness to refer.

The research model for the referrals stage is presented in Fig. 1.

3.2 The acceptance stage from a recipient’s perspective

The success of referrals hinges not only on motivating consumers to initiate them to refer but also on the willingness of recipients to accept these referrals, ultimately realizing a company’s marketing objectives such as acquiring new customers or influencing purchasing behavior. Consequently, we further delve into the dynamics of how these two categories of rewards impact recipients’ willingness to accept referrals during the acceptance stage.

3.2.1 Effect of different types of rewards on recipients’ willingness to accept referrals

To maintain consistency in research terminology, this paper predominantly classifies reward beneficiaries from the referrer’s viewpoint. Sender-benefiting rewards pertain to instances where the referrer receives benefits, whereas recipient-benefiting rewards denote cases where the recipients receive benefits. Consequently, in the acceptance stage, sender-benefiting rewards appear altruistic to the recipients, while recipient-benefiting rewards come off as self-interested. Thus, sender-benefiting rewards, favored in the referral stage, are comparatively less preferable than recipient-benefiting rewards in the acceptance stage. This is due to sender-benefiting rewards lacking direct financial benefits for the recipients. However, recipients face higher behavioral costs (like signing up or completing tasks) during the acceptance stage [14].

Aligned with economic exchange theory [64], recipients adopt a rationale prioritizing their utility maximization, meticulously weighing costs and benefits before accepting a referral. Indirect benefits, such as information acquisition and search reduction through referrals, are considered less attractive compared to direct rewards like monetary incentives [65]. Consequently, consumers show a greater inclination to accept recipient-benefiting rewards, primarily due to their financial benefits. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

H4: Recipient-benefiting rewards are likelier to motivate recipients to accept referrals than sender-benefiting rewards.

3.2.2 The mediating role of motivational inference

In the acceptance stage, where sharing serves as a persuasive behavior, the motivation and persuasive skills of a referrer exert a profound influence on consumers’ evaluation of persuasive information, ultimately influencing whether the referral is accepted or rejected [66]. Consequently, the impact of sender-benefiting and recipient-benefiting rewards on recipients can lead to distinct motivational inferences.

Based on the theory of multiple motive inference, when recipients encounter multiple motives, they evaluate primary behavioral motives considering situational factors and their familiarity with the referrer [67]. For instance, if situational factors prompt consumers to view a spokesperson in an advertisement as solely money-oriented, it diminishes the product’s credibility and weakens the advertisement’s persuasive impact [68]. Similarly, concerning reward-based referrals, rewards serve as cues prompting recipients to evaluate the motive behind the refer behavior. If recipients perceive that the referrer stands to gain personally from their referrals, they might interpret the motives as self-centered and selfish, leading to resistance toward the referral. As a result, the willingness to accept rewards benefiting the referrer decreases. Conversely, recipient-benefiting rewards, offering direct benefits to the recipient, are perceived as a genuine concern for the recipient’s well-being. This perception fosters a higher willingness to accept the referral. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5

Motivational inference mediates the relationship between referral reward type and recipients’ willingness to accept referrals. Specifically, recipient-benefiting rewards provide direct benefits to the recipient, leading to positive inferences regarding the referrer’s referral motivation. Conversely, sender-benefiting rewards only benefits the referrer without direct benefits for the recipient, leading to negative inferences about the referrer’s referral motivation.

3.2.3 Moderating effect of relationship type

Research underscores that the strength of a recipient’s relationship with a referrer significantly influences the perceived cost associated with accepting a referral [14]. Typically, individuals tend to be more receptive to referrals from close acquaintances than from strangers [69]. This tendency stems from the richer dynamics of stronger relationships characterized by increased interactions, longer durations, and heightened reciprocity [70]. Furthermore, the strength of the relationship significantly impacts the recipient’s perception of the referrer’s motivation behind the referral [20].

Within the context of sender-benefiting rewards, where the introduction of monetary incentives may trigger negative motivational inferences, recipients entrenched in a communal relationship, indicative of a strong bond, are still inclined to accept the referral. This acceptance can be attributed to the altruistic principles inherent in communal relationships, which mitigate the impact of negative motivational inferences. In contrast, within exchange relationships characterized by weaker connections, the predominant principle of interaction revolves around the notion of exchange [71]. In these circumstances, sender-benefiting rewards fail to elicit a significant increase in recipients’ willingness to accept a referral. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6

The impact of reward type on recipients’ willingness to accept is considerably stronger under exchange relationships compared to the impact of reward type on recipients’ willingness to accept under communal relationships.

The research model for the acceptance stage is presented in Fig. 2.

4 Experiment design and data analysis

To validate our hypotheses, we conducted three studies utilizing hypothetical scenarios across diverse contexts to ensure the generalizability of our findings. The pilot study aimed to compare the effectiveness of our manipulation of relationship type. In Study 1, we investigated how the interplay between reward type and relationship type influences the willingness to recommend during the referral stage. Building on the insights from Study 1, Study 2 delved deeper into the mechanisms underlying these interactions during the referral stage. Lastly, Study 3 focused on a recipient’s willingness to accept a referral, examining the impact of both self-interested and recipient-benefiting rewards on this willingness. Additionally, we explored the mediating role of motivational inference and the moderating role of relationship type in this context.

4.1 Pilot study

A pretest was conducted to ensure the effective manipulation of the relationship between participants and the company, aimed at mitigating interference from other factors. The scenario hypothesis method was employed to simulate the relationship between participants and the company, aligning with established experimental tests of the consumer-company relationship, as outlined by Clark (1984) [37].

4.1.1 Methods

Participants We recruited 100 participants (Mage = 37.1, SD = 7.183, 65% aged 20–30, 31.25% aged 31–40; 47.5% male, 52.5% female) from the Internet platform.

Design and Procedure Participants were provided with a brief description of their relationship with a fictional restaurant, prompting them with the statement: “There is a restaurant near your home where you often eat and are satisfied with their food and service.” Following the suggestion by Clark and Mills (2012) that relationship norms can be effectively triggered in laboratory studies, scenario descriptions were utilized to evoke relationship norms, with participants randomly assigned to either exchange or communal conditions [44]. Subsequently, participants, having engaged with the material outlining the relationships, were tasked with responding to scale questions to assess the effectiveness of the relationship-type manipulation (refer to Appendix B). To control for potential interference from diverse scenarios on perceived quality, we incorporated the service quality scale, with a sample statement being: “In general, I approve of the service quality of this restaurant” [72].

4.1.2 Data analysis results

The participants’ perceptions of exchange relationships were significantly higher in the exchange relationship condition (Mexchange = 5.986, SDexchange = 0.559; Mcommon = 5.126, SDcommon = 1.265; F (98) = 19.329, p < 0.00). Participants’ perceptions of communal relationships were significantly higher in the communal condition (Mexchange = 5.514, SDexchange = 0.760; Mcommon = 6.185, SDcommon = 0.489; F (98) = 27.549, p < 0.00). There was no significant difference in perceived service quality between the two conditions (Mexchange = 6.34, SDexchange = 0.658; Mcommon = 6.46, SD common = 0.788, F (98) = 0.683, p = 0.410). The results show that manipulation is effective for relationship types. The perceived service quality in the two conditions showed no significant difference (Mechange = 6.18, SDexchang = 0.790; M Communal = 6.12, SD Communal = 0.714; t (98) = 0.342, p = 0.733). The results indicate the effectiveness of manipulating relationship types.

4.2 Study 1: Factors influencing referrers’ willingness to refer

In Study 1, we investigated the impact of the interplay between relationship type and reward type on referrers’ willingness to refer. Employing a between-subjects design in an online experiment, we evaluated the influence of reward type and relationship-type interactions on the willingness to refer within the context of a restaurant scenario.

4.2.1 Methods

Participants We recruited 208 participants (Mage = 30.63, SD = 7.613, 65% aged 20–30, 28.8% aged 31–51; 44% male, 56% female) from the Internet platform. After excluding the 15 participants who did not complete the questionnaire, 193 participants remained and took part in the study. They were randomly assigned to a 2 (relationship type: exchange vs. communal) by 2 (reward type: sender-benefiting or recipient-benefiting) between-subjects design.

Design and procedure After reading the provided text, participants were tasked with responding to questions gauging their perception of the relationship with the restaurant, alongside an overall evaluation of the restaurant’s service quality (consistent with the pilot study). Additionally, participants were prompted to envision the restaurant as a person and rate the extent to which they identified the restaurant as a close friend, family member, or businessman. The key dependent variable, reflecting their willingness to refer, was measured by asking participants, “To what extent would you join in this referral reward activity and refer the restaurant to your friends?” on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = Very willing to share, 7 = Very reluctant to share). We also tested participants’ perceptions of service quality to eliminate the interference of different scenarios. The measurement statement used was: ‘Overall, I approve of the service quality of this restaurant.’

Subsequently, participants were briefed on the specifics of a user-sharing activity initiated by the restaurant. The purpose of this activity was to encourage participants to refer a link from the restaurant page to their friends, with success defined as their friends clicking on the link and becoming new members. For the sender-benefiting group, participants were offered a 10-RMB flat cash reward, while the recipient-benefiting group received a 10-RMB flat cash reward for their friend. This setup aimed to explore the impact of reward type on willingness to refer [73]. To control for the potential influence of reward amount, a medium reward of 20% of the product price (representing 87.1% of the restaurant industry in China, with expenditures ranging between 1–100 RMB per capita in 2021) was chosen [74].

4.2.2 Data analysis results

Manipulation Check: A 2 (relationship type) by 2 (reward type) ANOVA on the exchange relationship showed that only the main effect of relationship type is significant (F (1,189) = 82.130, p < 0.01). Similarly, only the main effect of relationship type on the communal relationship was significant (F (1,189) = 178.761, p < 0.01). There was no significant difference in the perception of service quality between the two conditions (M exchange = 5.569, SD exchange = 1.002 vs. Mcommon = 5.391, SDcommon = 0.974; p = 0.134). In both scenarios, there was no significant difference in the perception of service quality (Mexchange = 6.33, SD = 0.84 vs. M communal = 6.17, SD = 0.79; p = 0.18). Therefore, the manipulation test was valid.

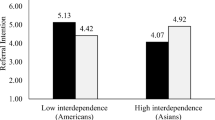

Willingness to Refer A 2 (relationship type) by 2 (reward type) ANOVA on the main effect of relationship type was not significant (Mexchange = 5.32, SDexchange = 1.025 vs. Mcommunal = 5.16, SDcommunal = 1.187, F (1,189) = 1.447, p = 0.230). The significant main effect of reward type (M sender-benefiting = 5.54, SD sender-benefiting = 0.925 vs. M recipient-benefiting = 5.24, SD recipient-benefiting = 1.134; F (1,189) = 7.671, p = 0.006) indicated that sender-benefiting rewards elicit a greater willingness to refer than recipient-benefiting rewards. These results verify H1. As shown in Fig. 4, the interaction between relationship type and reward type was significant (F(1.189) = 83.576, p < 0.00). The results of the simple effects analysis showed that for sender-benefiting rewards, willingness to refer was higher for the exchange relationship condition (Mexchange = 5.75 vs. Mcommunal = 4.39, F (1,189) = 47.459, P = 0.001). For recipient-benefiting rewards, willingness to refer was higher in the communal relationship condition (Mexchange = 4.91 vs. Mcommunal = 5.96, F (1,189) = 36.011, p = 0.000). The results are shown in Fig. 3. The experimental results supported H1 and H2.

4.2.3 Key findings

Study 1 examined the impact of relationship type and reward type on consumers’ willingness to refer. The ANOVA results indicated a significant main effect of reward type, demonstrating that sender-benefiting rewards prompted a higher inclination for referrals compared to recipient-benefiting rewards, thereby companying H1. Moreover, the interaction between relationship type and reward type was significant. Specifically, in the case of sender-benefiting rewards, consumers engaged in an exchange relationship with a company exhibited a greater willingness to refer than those in a communal relationship. Conversely, for recipient-benefiting rewards, consumers in a communal relationship demonstrated a higher willingness to refer, thereby confirming H2a and H2b. Subsequently, Study 2 delved deeper into exploring the mediation mechanisms associated with these two relationships.

4.3 Study 2: Mediating effects of economic and social motivation

The objective of Study 2 was to explore the mediating influences of economic and social motivation (H3a and H3b). To enhance external validity, diverse stimulus materials were utilized, and the study encompassed multiple participant groups. This approach aimed to mitigate the potential influence of confounding variables, including attitudes toward referrals.

4.3.1 Methods

Participants We recruited 218 participants from a university in China to participate in this experiment. After excluding those who did not approach the experiment seriously, 204 participants (Mage = 38.13, SD = 11.35, 68.1% aged 20–30, 28.3% aged 31–50; 55.1% male, 44.9% female) were enrolled in the experiment. Participants were randomly assigned to a 2 (relationship type: exchange vs. communal) by 2 (reward type: sender-benefiting or recipient-benefiting) between-subjects design.

Design and Procedure Participants were presented with introductory materials regarding a virtual cell phone brand and its referral program (see Appendix C). Following the material, the effectiveness of the relationship-type manipulation was gauged using scale questions (consistent with Study 1) to ensure the exclusion of service quality influences. Subsequently, after reviewing the details of the user-sharing activity (consistent with Study 1), participants responded to scale questions pertaining to willingness to refer, economic motivation, and social motivation, as per Hennig (2004) [50] (see Appendix C). Finally, participants provided demographic information, and their attitudes toward referrals were assessed to control for potential confounding variables with the question: “To what extent do you like referrals?” (1 = very disliked, 7 = very liked).

4.3.2 Results

Manipulation Check A 2 (relationship type) by 2 (reward type) ANOVA on the exchange relationship shows that only the main effect of relationship type is significant (F (1,200) = 11.349, p = 0.001). The perception of the exchange relationship is significantly greater in the exchange condition (Mexchange = 5.088, SDexchange = 0.963 vs. Mcommunal = 4.5621, SDcommunal = 1.241; p < 0.01). Similarly, only the main effect of relationship type on the common relationship is significant (F(1, 200) = 11.806, p < 0.01). The perception of the communal relationship under the communal condition is significantly greater (Mexchange = 4.726, SDexchange = 1.319 vs. Mcommunal = 5.281, SDcommunal = 0.961; p < 0.01); thus, the manipulation of the relationship type is successful.

Willingness to Refer a Product A 2 (relationship type) by 2 (reward type) ANOVA on willingness to refer showed a non-significant main effect of relationship type (Mexchange = 5.78, SDexchange = 0.774 vs. Mcommunal = 5.66, SDcommunal = 0.784; F (1, 200) = 1.358, p = 0.245). The significant main effect of reward type (Msender-benefiting = 5.64, SD sender-benefiting = 0.834 vs. M recipient-benefiting = 5.81, SD recipient-benefiting = 0.715; F (1, 200) = 2.834, p = 0.94, η2 = 0.029). These results verify H1. There was a significant interaction between relationship type and reward type (F (1.200) = 33.208, p = 0.000). A simple effects analysis revealed that for sender-benefiting rewards, the willingness to refer was higher for the exchange relationship condition (Mexchange = 5.372 vs. Mcommunal = 4.888, F (1,100) = 4.307, P = 0.001). For recipient-benefiting rewards, the willingness to refer was higher in the communal relationship condition (Mexchange = 4.601 vs. Mcommunal = 5.163, F (1,100) = 9.216, p = 0.003). The results are shown in Fig. 4 and again validate H2a and H2b.

Mediation Effects To examine the mediating role of economic motives, the mediating variables were examined using the bootstrap method, referring to the moderated mediation model proposed by Preacher (2007). We tested this indirect effect using Model 8 in PROCESS, with 5,000 bootstrapped samples. The results showed that the indirect effect of economic motivation was significant (β = 0.3450; SE = 0.1279; CI = (0.1141, 0.6232)). Specifically, the mediating effect was significant under the exchange relationship (β = 0.2330; SE = 0.0823; CI = (0.0840, 0.4068)), while the mediation was not significant under the communal relationship (β = −0.1120; SE = 0.0908; CI = (−0.2956, 0.0531)). Next, the mediating role of social motivation was examined using the same method, and the results showed that the indirect effect of social motivation was significant (β = 0.5327; SE = 0.1478; CI = (0.2781, 0.8524)). Specifically, the mediating effect was significant under the communal relationship (β = 0.4174; SE = 0.1165; CI = (0.1876, 0.6472)), while the mediating effect was not significant under the exchange relationship (β = −0.2133; SE = 0.1140; CI = (−0.4381, 0.115)). The results of the mediation effect test verified H3a and H3b.

4.3.3 Key findings

Study 2 revisited the impact of the interplay between the type of consumer–brand relationship and the type of reward on consumers’ willingness to refer. Notably, our findings reinforced the innate inclination towards self-interest in human nature, wherein individuals exhibit a preference for sender-benefiting rewards. The mediation test further confirms the mediating roles of economic and social motives. This study contributed to a deeper understanding of the factors and mechanisms influencing the efficacy of referrals in the first stage—the referral stage.

4.4 Study 3: Factors influencing recipients’ willingness to accept referrals

In Study 3, we scrutinized the determinants influencing a referee’s willingness to accept referrals during the acceptance stage. This investigation specifically examined the impacts of reward type on the referee’s inclination to accept a referral. Furthermore, the study delved into the mediating role of motivational inference and the moderating effect of the recipient-referrer relationship type (H4–H6).

4.4.1 Methods

Participant We recruited 136 participants from an online platform for the study, with 132 participants retained after eliminating those who did not engage seriously (Mage = 30.95, SD = 11.18, 73.5% aged 20–30, 25% aged 31–40; 52.7% male, 47.3% female). These participants were randomly assigned to a 2 (exchange vs. communal relationship) by 2 (sender-benefiting vs. recipient-benefiting) between-subjects design.

Design and Procedure Participants were initially presented with introductory materials: “You were recently looking for an English learning app and remembered that you have seen Wang’s English using this app, so you talk to him about this app. Wang tells you that this app is very good and can effectively improve the efficiency of learning English. He provides you with a download link and recommends that you download and use it.” Following this, they read texts on relationships and rewards, and responded to scale questions (refer to Appendix D). All scales utilized a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) [65], with the second term value being reverse-coded for calculating the mean values. Higher scores were indicative of exchange relationships, while lower scores were associated with communal relationships [66]. Participants also were asked to scale questions covering willingness to refer (dependent variable) [6] and motivation for sharing [49] (refer to Appendix D). Lastly, participants provided information on their gender and age.

4.4.2 Results

Manipulation Check First, an ANOVA of the friendships showed significant differences in relationship perceptions. Specifically, the exchange relationship condition had a higher score for relationship perception and was, therefore, considered an exchange relationship; the common relationship condition had a lower score and was considered a common relationship (Mexchange = 5.546, SDexchange = 1.088 vs Mcommunal = 2.164, SDcommunal = 0.832; p < 0.01). Further ANOVAs were done on the perception of exchange and communal relationships in both conditions, and the results showed that the perception of exchange relationships in the exchange condition was greater than that in the communal condition (Mexchange = 5.75, SDexchange = 1.076 vs. Mcommunal = 2.69, SDcommunal = 1.373; p < 0.01). Similarly, the perception of the common relationship was significantly greater in the common condition (Mexchange = 2.66, SDexchange = 1.253 vs. Mcommunal = 6.36, SDcommunal = 0.667; p < 0.01). and showed that the manipulation of the relationship type is successful.

Willingness to Accept A 2 (relationship type) by 2 (reward type) ANOVA showed a significant main effect of relationship type (Mexchange = 4.661, SD exchange = 1.456 vs. Mcommon = 6.193, SD common = 0.674; F(1, 132) = 61.193, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.32), a significant main effect of reward type (M recipient-benefiting = 5.947, SD recipient-benefiting = 0.880 vs. Msender-benefiting = 4.948, SDsender-benefiting = 1.551, F(1, 132) = 36.367, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.151) implies that recipient-benefiting rewards inspire a greater willingness to accept. A significant interaction of relationship type and reward type (F(1.132) = 19.829, p < 0.01) showed that the recipient-benefiting reward group was significantly more willing to accept (Mrecipient-benefiting = 5.569 vs. Msender- benefiting = 3.833, F (1,65) = 35.506, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.36).

Moderating Effects The results of the simple effect analysis showed that, under the condition of the exchange relationship, the acceptance willingness of the recipient-benefiting rewards group was significantly higher than that of the sender-benefiting reward group (Mrecipient-benefiting = 5.569 vs. M sender-benefiting = 3.833, F (1,65) = 35.506, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.36. There was no significant difference in the willingness to accept between the two groups under the condition of the communal relationship (Mexchange = 6.323 vs. Mcommunal = 6.062, F (1, 67) = 2.570, p = 0.114). The results are shown in Fig. 5 and support H6.

Mediation Effect: In this study, the same mediation test as in Study 2 was used to test the mediation of motivational inferences. The results showed that the indirect effect of motivational inference was significant (β = 0.7377; SE = 0.2558; CI = (0.2672, 1.2770)), supporting H5. Specifically, the mediating effect was significant under the exchange relationship (β = −1.1545; SE = 0.2197; CI = (−1.6166, −0.7448)), and the mediating effect was not significant under the communal relationship (β = 0.4168; SE = 0.1466; CI = (−0.7321, 0.1608)).

4.4.3 Key findings

Study 3 reveals that recipient-benefiting rewards are more widely accepted than sender-benefiting rewards in the acceptance stage (H4). The mediation analysis results support H5, demonstrating that motivational inferences mediate the relationship between reward type and willingness to accept. In conjunction with the findings of the interaction analysis, H6 is substantiated; specifically, the type of relationship between the referee and the acceptor plays a moderating role. Study 3 concentrates on the acceptance stage, specifically examining the impact of reward type on recipients’ willingness to accept. Additionally, the moderating effect of the type of recipient-referrer relationship is assessed.

5 Conclusions

Several studies have investigated the motivational dynamics of referral rewards, revealing mixed findings on the effectiveness of self-benefiting versus prosocial rewards [9, 14]. Our research contributes to this discourse by emphasizing the relevance of relational norms in shaping the impact of referral rewards. Through a series of three experimental studies and a pilot test, our findings reveal that within an exchange relationship between a referrer and a company, sender-benefiting rewards enhance the likelihood of referral engagement. Conversely, in a communal relationship, recipient-benefiting rewards foster a higher willingness to refer. Moreover, the type of reward extends its influence on the recipient’s acceptance, with sender-benefiting rewards potentially diminishing this inclination due to associated negative inferences. The moderating role of relationship norms further accentuates these effects, particularly in exchange relationships, where the type of reward exerts a more pronounced influence.

5.1 Theoretical contributions

This paper makes substantial contributions to the literature on reward referrals. Firstly, it expands the scope of rewards considered in the realm of reward referrals [56]. While prior studies often concentrated on the sender-benefiting rewards [15], our work takes a more expansive approach by merging theoretical frameworks with practical applications. Drawing from theories on pro-social behavior and altruism, we shed light on individuals’ engagement in altruistic actions aimed at aiding others or benefiting society as a whole. While altruistic behavior has undergone extensive scrutiny, it remains scarcely explored in the context of reward referrals, with Gershon’s (2020) study being a notable exception [14]. Hence, building upon Gershon’s work, our study extends existing knowledge by emphasizing the importance of recipient-benefiting rewards within the referral domain. We conduct a comprehensive examination of rewards that hold value for both the referrer and the recipient, underscoring their pivotal role in referral contexts.

Additionally, our study enhances the understanding of the efficacy of rewarded referrals by examining consumers’ intentions regarding referral and acceptance during the different stages of the rewarded referral process. Previous research has examined these two stages separately. Our study extends this research by investigating the influence of referral rewards at various stages [14]. Through rigorous experimentation, our findings offer empirical evidence that throughout the entire referral process—encompassing both the referral and subsequent acceptance stages—rewarding oneself yields greater effectiveness compared to rewards that benefit others. Embracing a comprehensive view of social e-commerce referral, our research recognizes that the success of referral hinges not only on existing consumers’ willingness to refer but crucially on prospective users’ willingness to accept. This holistic perspective transcends past epistemological constraints, offering actionable insights relevant to real-world social e-commerce contexts.

Furthermore, our study contributes to the understanding of relational norms within the context of reward referrals. We demonstrate that both the relationship norms between the company and the consumer, as well as the relationship norms between consumers, influence referral and acceptance behaviors. Our findings indicate that referrers exhibit a stronger inclination to refer sender-benefiting rewards when in exchange relationships with the company, and a higher propensity to refer recipient-benefiting rewards in communal relationships. Meanwhile, recipients display similar levels of willingness to accept recipient-benefiting rewards regardless of whether the relationship with the referrer is communal or exchange. However, the willingness to accept sender-benefiting rewards is higher in communal relationships compared to exchange ones.

Finally, our study contributes a motivational perspective to the understanding of the impact of rewards on referral effectiveness, offering a fresh viewpoint in the field of social e-commerce referrals. While prior research primarily engaged in cost–benefit analyses of rewards [49], our study delves deeper into the motivations behind rewards and their influence on referral behavior. Through an in-depth analysis of referral motivations, we not only elucidate the motivations propelled by rewards but also unveil their impact on the referrer’s perceived motivation. This novel approach enriches the existing body of research in social e-commerce referrals by introducing a new mechanism for exploring the nuanced effects of rewards on referral effectiveness.

5.2 Managerial implications

Referral marketing enables companies to use customers’ social networks to target new individuals interested in a product or service. Customers may adjust their willingness to refer based on the offered reward and their relationship type with the company. This study offers crucial insights into how social e-commerce companies can integrate incentivized referrals into their marketing strategies. In today’s digital landscape, harnessing social connections has become pivotal for acquiring customers. Our findings suggest that the influence of rewards on referring behavior varies depending on the company-consumer relationship nature. Sender-benefiting rewards are more effective in exchange relationships, while recipient-benefiting rewards resonate better in communal relationships. To maximize referral effectiveness, practitioners should tailor rewards by considering the norms of consumer relationships, rather than solely focusing on increasing the number of referrals. Although reciprocal incentives are commonly used to boost referrals, we find that details about rewards are frequently known only to the referrer and recipient. Companies can enhance social motivation by appropriately exposing reward-related information about the other party in communal relationships when providing details to consumers.

Moreover, we’ve observed that rewards favoring senders may generate a clash between market and social norms, potentially causing existing consumers to prioritize their self-interests. Furthermore, sender-benefiting rewards might lead to a perception of referrers as primarily driven by personal gain, possibly resulting in the rejection of their referral. It’s vital for practitioners to acknowledge and address this conflict to minimize any negative impacts these rewards might bring. In some reward referral programs where multiple recipients are needed for the referrer to benefit, considering the consumer relationship type becomes even more critical. This approach is particularly crucial for recipients in exchange relationships, where negative effects might arise. Hence, offering easily accessible rewards to recipients and disclosing minimal information about benefits received by the referrer could be beneficial.

Furthermore, our study underscores the importance for companies to establish and leverage brand communities for rewarding referrals. Our findings indicate that consumers engaged in a communal relationship with a company are inclined to recommend information, even without personal benefits. By fostering brand communities, companies can fortify consumer loyalty and involvement. Offering a platform for consumers to interact and engage with each other fosters a sense of belonging, nurturing stronger emotional connections between consumers and the company.

5.3 Limitations and future research directions

While this research makes substantial contributions to both theoretical understanding and practical insights, it does have certain limitations that merit consideration. First, the use of a fixed reward amount (10 RMB) in our study, while grounded in prior research findings and practices, is relatively simplistic. Exploring the effects of varying reward amounts on the efficacy of referrals would be valuable and could offer a more nuanced understanding of the impact of incentives. Second, our study primarily focused on the influence of relationship type on the acceptance stage, neglecting to investigate its effects on a referrer’s decision-making in the referral stage. The strength of a relationship can profoundly affects a referrer’s cost–benefit analysis when deciding to make a referral. Future studies should delve more deeply into the relational aspect, shedding light on its role in both the referral and acceptance stages. Third, although our study concentrated on the effects of reward and relationship types, other factors may also shape the effectiveness of referrals. Cultural differences, such as the collective orientation prevalent in Chinese/Asian cultures versus the individualistic tendencies in Western societies, might influence referral behaviors [75]. This cultural dimension was not addressed in our study, presenting an avenue for fruitful exploration in future research. Forth, our examination of the recipient’s willingness to accept was framed primarily through the lens of motivational inference. Future research could expand on this by delving deeper into the impact of rewards on recipients’ motivations and uncovering the underlying mechanisms that drive these behaviors. Lastly, our study primarily validated our hypotheses through scenario-based experiments. Future research could expand on the examination of the impact of reward types and relationship norms on consumers’ willingness to refer and accept by employing various research methodologies, such as utilizing secondary data, conducting field experiments, or engaging in behavioral observations. Addressing these limitations will contribute to a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the dynamics involved in social e-commerce referrals.

References

Wilson, A. (2020). Social media marketing: Ultimate user guide to Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Blogging, Twitter, LinkedIn, TikTok, Pinterest. Adidas Wilson.

Heinonen, K. (2011). Consumer activity in social media: Managerial approaches to consumers’ social media behavior. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 10(6), 356–364.

Wirtz, J., Tang, C., & Georgi, D. (2019). Successful referral behavior in referral reward programs. Journal of Service Management, 30(1), 48–74.

Schmitt, P., Skiera, B., & Van den Bulte, C. (2011). Referral programs and customer value. Journal of Marketing, 75(1), 46–59.

Xu, M., Yu, Z., & Tu, Y. (2023). I Will Get a Reward, Too: When Disclosing the Referrer Reward Increases Referring. Journal of Marketing Research, 60(2), 355–370.

Ryu, G., & Feick, L. (2007). A penny for your thoughts: Referral reward programs and referral likelihood. Journal of Marketing, 71(1), 84–94.

Wirtz, J., Orsingher, C., Chew, P., & Tambyah, S. K. (2013). The role of metaperception on the effectiveness of referral reward programs. Journal of Service Research, 16(1), 82–98.

Griskevicius, V., & Kenrick, D. T. (2013). Fundamental motives: How evolutionary needs influence consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(3), 372–386.

Imas, A. (2014). Working for the “warm glow”: On the benefits and limits of prosocial incentives. Journal of Public Economics, 114, 14–18.

Schwartz, D., Keenan, E. A., Imas, A., & Gneezy, A. (2021). Opting-in to prosocial incentives. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 163, 132–141.

Promberger, M., & Marteau, T. M. (2013). When do financial incentives reduce intrinsic motivation? comparing behaviors studied in psychological and economic literatures. Health Psychology, 32(9), 950.

Staub, E. (2013). Positive social behavior and morality: Social and personal influences. Elsevier.

Glazer, A., & Konrad, K. A. (1996). A signaling explanation for charity. The American Economic Review, 86(4), 1019–1028.

Gershon, R., Cryder, C., & John, L. K. (2020). Why prosocial referral incentives work: The interplay of reputational benefits and action costs. Journal of Marketing Research, 57(1), 156–172.

Berman, J. Z., & Small, D. A. (2012). Self-interest without selfishness: The hedonic benefit of imposed self-interest. Psychological Science, 23(10), 1193–1199.

Wong, A., & Sohal, A. (2002). An examination of the relationship between trust, commitment and relationship quality. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 30(1), 34–50.

Garbarino, E., & Johnson, M. S. (1999). The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70–87.

Zhang, K. Z., & Benyoucef, M. (2016). Consumer behavior in social commerce: A literature review. Decision Support Systems, 86, 95–108.

Hong, Y., Pavlou, P. A., Shi, N., & Wang, K. (2017). On the role of fairness and social distance in designing effective social referral systems. MIS Quarterly, 41(3), 787-A713.

Verlegh, P. W., Ryu, G., Tuk, M. A., & Feick, L. (2013). Receiver responses to rewarded referrals: The motive inferences framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41, 669–682.

Berman, B. (2016). Referral marketing: Harnessing the power of your customers. Business Horizons, 59(1), 19–28.

Wang, Q., Mao, Y., Zhu, J., & Zhang, X. (2018). Receiver responses to referral reward programs in social networks. Electronic Commerce Research, 18, 563–585.

Turban, E., King, D., Lee, J. K., Liang, T. P., Turban, D. C., Turban, E., King, D., Lee, J. K., Liang, T.-P., & Turban, D. C. (2015). Retailing in electronic commerce: Products and services. In Electronic commerce: A managerial and social networks perspective (pp. 103–159).

Blattberg, R. C., & Deighton, J. (1991). Interactive marketing: Exploiting the age of addressability. Sloan Management Review, 33(1), 5–15.

Myrseth, K. O. R., & Fishbach, A. (2009). Self-control: A function of knowing when and how to exercise restraint. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(4), 247–252.

Kumar, V., Petersen, J. A., & Leone, R. P. (2010). Driving profitability by encouraging customer referrals: Who, when, and how. Journal of Marketing, 74(5), 1–17.

Forsythe, I. D. (1994). Direct patch recording from identified presynaptic terminals mediating glutamatergic EPSCs in the rat CNS, in vitro. Journal of Physiology, 479(3), 381–387.

Vohs, K. D., Mead, N. L., & Goode, M. R. (2006). The psychological consequences of money. Science, 314(5802), 1154–1156.

Moore, C. (2009). Fairness in children’s resource allocation depends on the recipient. Psychological Science, 20(8), 944–948.

Wang, X., & Ding, Y. (2022). The impact of monetary rewards on product sales in referral programs: The role of product image aesthetics. Journal of Business Research, 145, 828–842.

Ahrens, J., Coyle, J. R., & Strahilevitz, M. A. (2013). Electronic word of mouth: The effects of incentives on e-referrals by senders and receivers. European Journal of Marketing, 47(7), 1034–1051.

Heyman, J., & Ariely, D. (2004). Effort for payment: A tale of two markets. Psychological Science, 15(11), 787–793.

Lingane, A., & Olsen, S. (2004). Guidelines for social return on investment. California Management Review, 46(3), 116–135.

Hinde, R. A. (1976). Interactions, relationships and social structure. Man, 1–17.

Aggarwal, P. (2004). The effects of brand relationship norms on consumer attitudes and behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 87–101.

Lim, J. S., Chock, T. M., & Golan, G. J. (2020). Consumer perceptions of online advertising of weight loss products: The role of social norms and perceived deception. Journal of Marketing Communications, 26(2), 145–165.

Clark, M. S. (1984). Record keeping in two types of relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(3), 549.

Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), 179–191.

Mullins, R. R., Ahearne, M., Lam, S. K., Hall, Z. R., & Boichuk, J. P. (2014). Know your customer: How salesperson perceptions of customer relationship quality form and influence account profitability. Journal of Marketing, 78(6), 38–58.

Hughes, J. D. (2009). An environmental history of the world: Humankind’s changing role in the community of life. Routledge.

Yang, M.M.-H. (2016). Gifts, favors, and banquets: The art of social relationships in China. Cornell University Press.

Miller, D. T. (1999). The norm of self-interest. American Psychologist, 54(12), 1053.

Martinsson, P., Myrseth, K. O. R., & Wollbrant, C. (2014). Social dilemmas: When self-control benefits cooperation. Journal of Economic Psychology, 45, 213–236.

Clark, M. S., & Mills, J. R. (2012). A theory of communal (and exchange) relationships. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, 2, 232–250.

Tuk, M. A., Verlegh, P. W., Smidts, A., & Wigboldus, D. H. (2009). Sales and sincerity: The role of relational framing in word-of-mouth marketing. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19(1), 38–47.

Elster, J. (1989). Social norms and economic theory. Journal of economic perspectives, 3(4), 99–117.

Whitener, E. M., Brodt, S. E., Korsgaard, M. A., & Werner, J. M. (1998). Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 513–530.

Reimer, T., & Benkenstein, M. (2018). Not just for the recipient: How eWOM incentives influence the recommendation audience. Journal of Business Research, 86, 11–21.

Ariely, D., Bracha, A., & Meier, S. (2009). Doing good or doing well? Image motivation and monetary incentives in behaving prosocially. American Economic Review, 99(1), 544–555.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., Walsh, G., & Gremler, D. D. (2004). Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(1), 38–52.

Grant, A. M., & Gino, F. (2010). A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(6), 946.

Pascual-Ezama, D., Prelec, D., & Dunfield, D. (2013). Motivation, money, prestige and cheats. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 93, 367–373.

Fu, J.-R., Ju, P.-H., & Hsu, C.-W. (2015). Understanding why consumers engage in electronic word-of-mouth communication: Perspectives from theory of planned behavior and justice theory. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 14(6), 616–630.

Basit, A. A., Hermina, T., & Al Kautsar, M. (2018). The influence of internal motivation and work environment on employee productivity. KnE Social Sciences.

Frederiks, E. R., Stenner, K., & Hobman, E. V. (2015). Household energy use: Applying behavioural economics to understand consumer decision-making and behaviour. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 41, 1385–1394.

Jin, L., & Huang, Y. (2014). When giving money does not work: The differential effects of monetary versus in-kind rewards in referral reward programs. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 31(1), 107–116.

Frey, B. S., & Oberholzer-Gee, F. (1997). The cost of price incentives: An empirical analysis of motivation crowding-out. The American Economic Review, 87(4), 746–755.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (2017). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Interpersonal Development, 57–89.

Sun, Y., Dong, X., & McIntyre, S. (2017). Motivation of user-generated content: Social connectedness moderates the effects of monetary rewards. Marketing Science, 36(3), 329–337.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

Ellingsen, T., & Johannesson, M. (2008). Pride and prejudice: The human side of incentive theory. American Economic Review, 98(3), 990–1008.

Martin, K. D., & Smith, N. C. (2008). Commercializing social interaction: The ethics of stealth marketing. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 27(1), 45–56.

Orsingher, C., & Wirtz, J. (2018). Psychological drivers of referral reward program effectiveness. Journal of Services Marketing, 32(3), 256–268.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900.

Harunavamwe, M., & Kanengoni, H. (2013). The impact of monetary and non-monetary rewards on motivation among lower level employees in selected retail shops. African Journal of Business Management, 7(38), 3929.

Clee, M. A., & Wicklund, R. A. (1980). Consumer behavior and psychological reactance. Journal of Consumer Research, 6(4), 389–405.

Sparkman, Jr, R. M. (1982). The discounting principle in the perception of advertising. Advances in Consumer Research, 9(1).

He, Y., You, Y., & Chen, Q. (2020). Our conditional love for the underdog: The effect of brand positioning and the lay theory of achievement on WOM. Journal of Business Research, 118, 210–222.

Brown, J. J., & Reingen, P. H. (1987). Social ties and word-of-mouth referral behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(3), 350–362.

Macy, M. W., & Willer, R. (2002). From factors to actors: Computational sociology and agent-based modeling. Annual review of sociology, 28(1), 143–166.

Pavlou, P. A., Liang, H., & Xue, Y. (2007). Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online exchange relationships: A principal-agent perspective. MIS Quarterly, 105–136.

Laroche, M., Teng, L., Michon, R., & Chebat, J. C. (2005). Incorporating service quality into consumer mall shopping decision making: A comparison between English and French-Canadian consumers. Journal of Services Marketing, 19(3), 157–163.

Zhu, Y., & Lin, P. (2019). Hedonic or utilitarian: The influences of product type and reward type on consumer referral likelihood. Journal of Contemporary Marketing Science, 2(2), 120–136.

The Restaurant industry in China. (2021). IimediaResearch [R]

Le Serre, D., Weber, K., Legohérel, P., & Errajaa, K. (2017). Culture as a moderator of cognitive age and travel motivation/perceived risk relations among seniors. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 34(5), 455–466.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix A. Literature on referral rewards

Research | Key IVs | Key DVs | Main Result | Research perspective | Rewards type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Peng, Xixian et al. (2023) | Reward, congruity | Consumers’ recommendation intention | nonmonetary rewards with moderate congruity trigger consumers’ recommendation intention in RRPs more than those with high and low congruity | Referrer | Nonmonetary rewards |

Qi Wang et al. (2017) | Reward, tie strengths | Receiver responses | People with strong ties tended to accept a referral more often than those with weak ties, because people with strong ties gave their friends’ benefits more consideration | Recipient | Social rewards (non-monetary rewards vs. market rewards (monetary rewards) |