Abstract

The introduction of a commitments procedure in EU antitrust policy (Article 9 of Council Regulation 1/2003) has entitled the the European Commission to extensively settle cases of alleged anticompetitive conduct. In this paper, we use a formal model of law enforcement to identify the optimal procedure to remedy cases in a context of partial legal uncertainty (Katsoulacos and Ulph in Eur J Law Econ 41(2):255–282, 2016). We discuss in particular the merits of a policy of selective commitments where firms either take strong commitments or are investigated under the standard infringement procedure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In 2003, a reform of European Union (“EU”) competition law entitled the European Commission (“the Commission”) to enter into settlements with parties suspected of infringement of Articles 101 and/or 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (“TFEU”). In exchange for “commitments”from suspected firms to change their conduct or modify their structure, the Commission closes proceedings. With this new procedure, the Commission can allegedly restore market competition expediently.Footnote 1

In the literature, the commitments procedure is often described as a substitute to infringement proceedings under Article 7 of Regulation1/2003. Wils (2008) documents two benefits on the side of the agency. First, the Commission can achieve earlier resultsFootnote 2 and second, it makes costs savings.Footnote 3 Practitioners also report benefits on the side of the firm. Since there is no formal finding that the firm is guilty of infringement, the firm avoids a variety of supplementary costs such as fines, follow-on damage actions and reputational stain. As a result, some practitioners have praised commitments decisions as a “win–win”instrument for both the Commission and the alleged infringer (Bellis 2013).

In this paper, we show that the commitments procedure is not simply a fast-track substitute of the infringement procedure that enables the Commission to achieve equivalent outcomes without, however, being constrained by similar procedural inefficiencies.Footnote 4 Rather, our main finding is that the remedies differ significantly in the two procedures.

To that end, we represent the interaction between the Commission and market players as a game with three main features. First, the Commission potentially faces different infringers. Some firms are responsible for a major harm, others have caused a minor harm. There is asymmetric information relative to the harm. Second, the illegality of the conduct is not certain. Put differently, it is not clear from the outset for both parties that the conduct satisfies the conditions for antitrust liability. While the probability of conviction is common knowledge, it is not known a priori whether a firm will be effectively convicted. This framework corresponds to what Kastoulacos and Ulph (2016, 2017) call partial legal uncertainty: firms know the harm caused by their conduct to consumers but they do not know whether the conduct will be deemed to be lawful or unlawful by the authorities (if investigated). Third, the Commission has two categories of procedural tools: the standard infringement procedure under Article 7 and the commitments procedure under Article 9. With the infringement procedure, the Commission establishes precisely the infringement as a matter of law and measures the consumer harm as a matter of fact. With the commitments procedure, the Commission enters into a settlement with the firm. The procedure does not formally establish the infringement as a matter of law and leaves possibly the harm undetermined.

Against this background, we descriptively formalize options faced by the Commission as three possible types of enforcement policies: a generalized infringement policy, a selective commitments policy and a generalized commitments policy. In the generalized infringement policy, the Commission uses Article 7 in all or most of the cases where the suspected infringement, the relevant markets and the potential remedies are similar. In the selective commitments policy, the Commission makes a mixed use of Article 7 and Article 9 for cases of a similar category.Footnote 5 This is the policy that was followed in Microsoft I (Article 7) and Microsoft II (Article 9) cases. Finally, in the generalized commitments policy, the Commission uses Article 9 in all or most cases of a similar category.

In this paper, we seek to assess the costs and benefits of those various policies. A key challenge for the authority is to screen between different levels of harm. We show that when the Commission applies generalized commitments, this leads to under enforcement of competition law. The reason is that remedies are suboptimal: in order to convince all firms to settle, the Commission must accept commitments that are set a minima. Put differently, with generalized commitments, there is a sort of “race to the bottom”effect to convince firms to settle. As a result, we conclude that, under a generalized commitments policy, the Commission applies weak remedies. This under enforcement effect could be mitigated if the commitments procedure was used selectively, with the Commission agreeing to settle with firms offering strong remedies and launching the infringement procedure for those offering weak or no remedies. Being selective in the use of commitments is a tool to bridge the information gap and limit the under enforcement problem associated with commitments. The selective commitments policy uses the threat of returning to the infringement procedure to extract strong commitments from the firm. This policy is fittingly illustrated by the Google Shopping case that the Commission closed in June 2017 with an infringement decision (under appeal). Google and the Commission were first engaged in settlement talks. Google formulated three rounds of commitments proposal. All of them were rejected by the Commission. At the time, the Commissioner in charge of competition policy publicly announced that if Google refused to improve its proposal, the Commission would switch to the standard infringement procedure.Footnote 6 In April 2015, the Commission sent a statement of objections to Google and the firm was finally convicted of an abuse of a dominant position. With the selective commitments policy, commitments are negotiated in the shadow of litigation and the competition authority uses the threat of moving back to the infringement procedure to extract strong commitments. A major issue is to make this policy credible. If a firm refuses to take strong commitments—thereby signaling that the harm to consumers is limited—the authority must be ready to start an infringement procedure. Absent this, the threat is ineffective. In brief, a selective commitments policy thus consists in using the two procedures as a screening device, one which leads to negotiate with those responsible of a major harm and one which sues those responsible of a minor harm. The merits of this policy must be compared with a generalized infringement policy. This policy suffers from potentially higher administrative costs and may fail to remedy anti-competitive harm when the legal evidence necessary to convict the firm is weak. In other words, there is a risk of a false acquittal.

With this background, the originality of our model is to show that the choice of a generalized commitments policy, of a selective commitments policy or of the standard infringement policy should hinge on the underlying case uncertainty. We focus in particular on the difference between major and minor harm and the probability of conviction with the infringement procedure. When there is little uncertainty surrounding the importance of the harm to consumers, there is a limited race to the bottom effect and the generalized use of commitments is appropriate. On the contrary, with higher uncertainty, it is optimal to apply a policy that entitles to screen between types and tailor the remedy to the harm. The choice between a selective commitments policy and a generalized infringement policy depends on the probability of being convicted in an infringement procedure. If this probability is high, the selective commitments policy is preferable because it entails lower administrative costs. If the probability is low, the threat of returning to the infringement procedure if the firm does not take strong commitments is weak and the selective commitments procedure is ineffective. The generalized infringement policy is thus advisable despite its high administrative costs and the risk of false acquittals (leaving the conduct non-remedied despite its harm because the competition authority lacks of the appropriate legal evidence). Finally, our paper also attempts to discuss the Commission’s decisional policy in the light of our model. To that end, we regroup antitrust cases that can be deemed to belong to a similar category, and we identify the enforcement policy followed by the Commission for each group.

2 Related literature

Our paper cuts through three distinct fields of the law and economics literature. First, the paper relates to the early literature on judicial settlements (Landes 1971), in particular in relation to the parties and defendants’ choice between a settlement and a trial in the criminal justice system. The paper shares analogies with contemporary models that have flourished following the development of game theory and the economics of information (Wang et al. 1994). In essence, those models review the trade-off between litigation and negotiation under asymmetric information. Some assume that the plaintiff is informed (Png 1987), others that the defendant is (Reinganum and Wilde 1986; Nalebuff 1987). Private information could be related to the importance of the damage (Bebchuk 1984) or to the likelihood of conviction (Shavell 1989) and the literature analyzes different frameworks for organizing settlement talks (Daughety and Reinganum 1993).

Second, our paper seeks to enrich the literature on optimal law enforcement focusing on the specificities of the EU antitrust regime. Few papers have so far devoted extensive economic treatment to the question of what is the optimal mix between the infringement and commitments procedures in EU antitrust policy. Choné et al. (2014) characterize the agency choice to resort to a certain degree of commitments in terms of a trade-off between the early restoration of competition and the lost deterrent effect of applying the commitments procedure (no fine)Footnote 7 and they derive an optimal commitment policy. Their model is similar to ours with the firm having private information on its benefit and the harm to consumers caused by its conduct and the authority chooses the enforcement path. The model is thus a screening model. Choné et al. (2014) recommend to use the commitments procedure systematically when the harm to consumers and the profit to the firm are moving in the same direction i.e. when more harmful actions are also more profitable. In this case, the deterrence is ineffective and the earlier restoration of competition is the main concern of the competition authority. It is only when the relation between harm and profit is non-monotonic that the competition authority uses both enforcement paths with positive probability. One of the main difference between our paper and this paper is that we consider that commitments are negotiated in the shadow of litigation while in their paper, commitments consist in terminating the practice and is screening is not an issue. As a consequence in our model, the commitments may imperfectly remedy the harm. Polo and Rey (2016) perform an exercise that is similar to ours but considering commitments as a signaling game. Their main result is to show that there is generally no separating equilibrium when commitments are proposed by the firm and therefore that this enforcement tool cannot be used to screen between different levels of harm. One of our contribution is to discuss the possibility to implement a selective commitments policy where the two procedures are used as a screening device. We consider in the main part of the text a screening model and, as an extension, a signaling model. We identify circumstances in which the selective commitments policy is time-consistent and the competition can use to screen between types. Notice that, separation of type is more complicated [but not impossible contrarily to Polo and Rey (2016)] when commitments are offered at the firm’s initiative. Observe also that our focus is on screening between actions causing different levels of harm to consumers. We assume that if the authority has moved to the stage where it is considering the abovementioned three enforcement policy options without closing the case (for instance, by rejecting complaints), it has determined that the case generates anticompetitive effects but remains uncertain on whether there is minor or serious harm. This distinguishes our paper from previous works which envision a larger set of options where the authority can also consider that a case generates pro-competitive effects.

Third, our paper can be tied to the emerging literature on antitrust agency discretion. An increasing number of studies in both the US and the EU has been devoted to the question of how agencies discretionarily channel their limited administrative resources, and prioritize cases, procedures, and remedies (Wils 2011). Hyman and Kovacic (2012, 2013), for instance, discuss how agencies with a complex policy portfolio apportion their resources. Schinkel et al. (2014) study the welfare effects of task prioritization in an agency where the head has a discretionary power over the use of budgetary resources. Our paper contributes to this literature by making recommandations on the use of commitments negotiations in antitrust, emphasizing the importance of uncertainty.

3 The model

We analyze a game between a competition authority (CA) and a firm. The game starts with the firm deciding to engage in a conduct that is possibly anticompetitive. In a second step, the authority opens an investigation against the firm suspected of infringing competition law. The reasons underpinning the opening of an investigation are diverse: complaints from rivals, customers, suppliers or trade associations, notification of a possible infringement by national competition authorities or sector specific regulators, allegations of abuse in the public domain (press, academic research, etc.). The CA has two procedural routes to investigate the case, the infringement procedure (Article 7) and the commitments procedure (Article 9). These procedures specify several tools that the CA can use to remedy anticompetitive practices. The CA can impose to the firm a change in its structure (e.g. asset divesture) or a change in its conduct (e.g. end of the anticompetitive practice, licensing obligations). In both cases, the aim is to restore competition on the market.

3.1 The firm

At the beginning of the game, the firm decides to adopt a course of conduct that is possibly prohibited under competition law. If the firm does not undertake such an action, its profit is zero and the consumer surplus is equal to S. If the firm undertakes the practice, it generates a positive profit equal to \(\pi \) and it has an impact on the consumer surplus (supra-competitive prices, rival foreclosure, delay in the introduction of new products, etc). The impact on the consumers depends on the “state of the world”. In State 1, the firm is responsible of a major harm to consumers and the surplus is reduced by \(\overline{H}>0\). In State 2, the firm is responsible of a minor harm and the surplus is reduced by \(\underline{H}\), with \(\overline{H}>\underline{H}\). In the baseline model, we will suppose that \(\underline{H}>0\) i.e. that the conduct always harms consumers. As an extension, we will consider the case where the conduct is anticompetitive in State 1 (\(\overline{H}>0\)) and procompetitive in State 2 (\(\underline{H}<0\)).

Consumer surplus is equal to \(S-\overline{H}\) in State 1 and \(S-\underline{H}\) in State 2. The probability of being in State 1 (resp. State 2) is equal to \(\nu \) (resp. \(1-\nu \)). When the firm decides to engage in anticompetitive conduct, it learns the true harm its conduct imposes to consumers.

3.2 Competition authority

The competition authority opens an investigation against the firm without knowing the importance of the harm to consumers. We suppose that, due to its greater proximity from the markets, the firm possesses private information on the state of the world that the competition authority does not have. Following the investigation, the Commission, if it believes that the case has merit, will issue a statement of objections (SO). This document informs the parties of the Commission’s objections against them. The procedure is then closed with either an infringement or a clearance decision. In the former case, the Commission can adopt structural and behavioral remedies as well as fines. Any such Article 7 decision can subsequently be appealed before the General Court. An alternative to the adoption of an Article 7 decision, and before it to the adoption of a SO, is to open commitments discussions under Article 9.Footnote 8 The commitments can be either behavioral or structural and may be limited in time and they should address the Commission’s concerns.

In the model, we will denote by R, the structural or behavioral remedy imposed by the CA (without formally distinguishing between the two). Remedies aim at correcting the harm to consumers but they represent a cost for the firm. A remedy may insufficiently (\(R<H\)), perfectly (\(R=H\)) or excessively (\(R>H\)) correct the harm to consumers. Formally, we suppose that, when the CA imposes a remedy R the consumer surplus is \(S-|H-R|\). The cost to the firm of a remedy R is a reduction of its profit by \(\alpha R\), with the parameter \(\alpha \) capturing the idea that a remedy may impact differently firms and consumers. Remedies can be imposed both in the infringement and the commitments procedures but fines can only be imposed in the infringement procedure. Finally, we will suppose that the objective of the CA is to maximize consumer surplus net of the procedural costs. In terms of consumer surplus, the first best policy consists in imposing a remedy \(R=\overline{H}\) in State 1 and \(R=\underline{H}\) in State 2.

4 Two procedures, three policies

4.1 Two procedures

4.1.1 The infringement procedure

To adopt an infringement decision, the CA must reach a finding of unlawful conduct based on a theory of harm, measure its actual or likely anticompetitive effects, design a suitable remedy and, eventually impose a fine to the infringer. At the beginning of the procedure, there is an asymmetry of information between the CA and the firm regarding the importance of the harm. In addition, the firm and the CA do not know a priori whether the alleged conduct under scrutiny can be deemed illegal. There is an uncertainty regarding the outcome of the legal investigation and, in particular, whether or not the CA will be able to find convincing evidence of unlawful conduct. If the CA investigates the case under the standard adversarial procedure (Article 7), the infringement will be established with probability p.Footnote 9 With the complementary probability \((1-p)\), there is not enough evidence to establish the infringement and the CA has to close the case.Footnote 10 Factual verifications conducted during the investigation give to the CA elements to estimate and quantify the harm to consumers caused by the firm. We suppose that the CA learns the true state of the world i.e. the importance of harm with the infringement procedure.

In our model, the information structure is the following: the firm knows the harm caused by its conduct to consumers i.e. they know the state of the world, while the CA does not. But the firm does not know whether its conduct will be qualified as legal or illegal. However, it is common knowledge that with probability p the firm’s conduct will be disallowed if investigated under Article 7. This information structure is called partial legal uncertainty by Kastoulacos and Ulph (2016). Finally notice that given that the action is harmful to consumers in both states, there is a probability \((1-p)\) of false acquittals i.e. with probability \((1-p)\) the CA cannot make the case because the evidence is poor.

Starting a standard infringement procedure is costly for both the CA and the firm. For the CA, the cost of the procedure is set to \(c>0\) and it represents all the resources that the authority must mobilize to investigate the case. For the firm, irrespective of the outcome, it is costly to be involved in an infringement procedure. It must remunerate lawyers and consultants and it suffers from an intangible cost of being under the scrutiny of an antitrust agency and possibly under negative media exposure (reputational damage). This cost for the firm is set to \(d\ge 0\).

If the CA adopts an infringement decision, it imposes a remedy R to the firm. The CA may additionally seek to punish established infringers by imposing a fine F. A fine reduces the firm’s profit but it has no impact on the consumer surplus. In our model, we suppose that fines are exogenously given.Footnote 11

4.1.2 The commitments procedure

As an alternative to the infringement procedure, the firm and the Commission can enter into commitments talks, with a view to closing the case in exchange for behavioral or structural concessions. This negotiation process, formally enshrined in Article 9, has several important features. First, the Commission has the option to return to the standard infringement procedure at any time i.e. if the parties fail to reach an agreement. Commitments are thus negotiated in the shadow of litigation. Second, under Article 9, commitments are optional and neither the firm nor the CA are obliged to participate in the negotiation. Third, with the commitments procedure, the parties and the Commission avoid lengthy oral and written proceedings. Fourth, for the firm there is no formal conviction of unlawful conduct. There are thus potential savings in both the procedural and the reputational costs compared to the infringement procedure. In line with that, we assume that negotiating settlements is costless for both parties. In other words, the costs c and d represent the additional cost of the infringement procedure.

The negotiation of commitments takes place under asymmetric information. The literature considers both screening models where the non-informed party makes a settlement offer to the informed party who then accepts or declines it (Bebchuk 1984) and signaling models where the informed party formulates the offer (Reinganum and Wilde 1986). Applied to the specific case of the commitments procedure used in the EU, Choné et al. (2014) suppose that the CA makes a commitments offer to the firm while Polo and Rey (2016) suppose that the firm is formulating an offer to the CA. The question is far from being innocent as the existence of a separating equilibrium where the CA uses a different procedure in the two states may depend on which party is formulating the commitments offers. In this paper, we will follow the approach of Choné et al. (2014) and suppose that the CA suggests commitments to the firm. If commitments are refused, the CA has the option to start the infringement procedure. We will however check, in Sect. 5.1 that our results are robust to an alternative scenario where it is the firm that is making a commitments offer to the CA.

The commitments negotiation takes place as follows:

-

1.

The CA makes a take-it-or-leave it offer R to the firm,

-

2.

The firm accepts or refuses the offer,

-

If the firm accepts the offer, the CA makes the commitments legally binding and the remedy R is implemented.

-

If the firm refuses the offer, the CA may launch an infringement procedure or abandon the case.

-

4.2 Three policies

The CA can avail itself of three policies to address anticompetitive practices: a generalized infringement policy where all cases are dealt with the infringement procedure; a selective commitments policy where the CA uses different procedures; and a generalized commitments policy.

4.2.1 Generalized infringement policy

In a generalized infringement policy, the CA exclusively uses the infringement procedure. The CA pays the cost c and discovers the state of the world. The CA can impose a remedy only if the conduct is truly unlawful (which happens with probability p). In which case the CA implements the first-best remedy \(R=\overline{H}\) in State 1 and \(R=\underline{H}\) in State 2. In addition, the CA imposes a fine F to the infringer. With probability \((1-p)\), the CA cannot remedy the conduct of the firm.

The payoffs to the firm in State 1 are \(\pi -\alpha \overline{H}-F-d\) if it is found liable of an infringement and \(\pi -d\) otherwise. Similarly, the payoffs to the firm in State 2 are respectively \(\pi -\alpha \underline{H}-F-d\) and \(\pi -d\). The expected payoffs to the firm in state \(k=1,2\) are then equal to:

The expected consumer surplus in state \(k=1,2\), net of the procedural cost c supported by the CA is:

If the CA starts the infringement procedure, the expected surplus is:

If the CA closes the case immediately without further investigation or negotiation, the consumer surplus is:

At the beginning of the game, the CA starts the infringement procedure if \(\hat{S}\ge S^\emptyset \). In the sequel, we will assume that enforcement is valuable and that the condition \(\hat{S}\ge S^\emptyset \) holds true:

Assumption 1

\( \nu p\overline{H}+(1-\nu )p \underline{H}>c\).

4.2.2 Selective commitments policy

With selective commitments, the CA screens, eventually imperfectly, the two types of harm, major and minor. To that end, it leaves the option of two different tracks to solve the case: the commitments procedure or the infringement procedure. The selective use of the two procedures is used as a screening device. The selective commitments policy works as follow. The CA offers the firm to take strong commitments. Commitments must be strong enough to be accepted in State 1 and refused in State 2. If the firm refuses the commitments, the CA opens a formal infringement procedure. To be credible, a formal investigation must be started in the case of a refusal. Indeed, the firm will agree to take strong commitments in State 1 only under the threat of returning to the formal infringement procedure in the case of a refusal. But for the CA starting an infringement after the firm’s refusal might be problematic as a refusal signals that the harm is minor. Making the selective commitments policy time-consistent is therefore a concern.

To use the two procedures to screen between the two levels of harm, the proposed remedy \(\overline{R}\) must be such that the firm accepts it in State 1 and refuses it in State 2. Formally, \(\overline{R}\) must satisfy:

Equations (7) and (8) define an upper bound \(R^{max}\) and a lower bound \(R^{min}\) for the proposed commitments, with \(R^{max}=p\overline{H}+\frac{pF+d}{\alpha }\) and \(R^{min}=p\underline{H}+\frac{pF+d}{\alpha }\). The following lemma discusses when a fully separating equilibrium exists.

Lemma 1

A selective commitments policy where the CA proposes commitments \(\overline{R}\in [R^{min},\, R^{max}]\) and, in State 1, the firm accepts the proposed commitments while, in State 2, the firm refuses them and the CA starts an infringement procedure is feasible if \(p\underline{H}\ge c\).

This separating mechanism works if—when commitments are refused—the CA decides to return to the infringement procedure at cost c. Otherwise, anticipating a termination of the case after having refused strong commitments, no firm will ever agree to settle. In a nutshell, the selective commitments procedure uses the threat of going back to Article 7 to extract strong commitments from the firm. The threat of moving back to the Article 7 procedure is the cornerstone of the selective commitments policy. Without it, the firm has no incentive to agree on strong commitments. For this reason, a fully separating equilibrium does not always exists. It exists when the CA is better off starting an infringement procedure after refusal i.e. when it knows for sure that the harm is minor. In state 2, if the CA terminates the case, the consumer surplus is \(S-\underline{H}\). If it starts an infringement procedure, the surplus is \(\hat{S}^2\). The condition in the Lemma guarantees that the selective commitments policy is time-consistent i.e. \(\hat{S}^2\ge S-\underline{H}\).Footnote 12

The consumer surplus with the separating equilibrium is equal to:

If \(p\underline{H}\le c\), there is no separating equilibrium and the only equilibrium is a semi-pooling equilibrium where the CA offers commitments such that the firm in state 1 accepts commitments with probability \(\gamma <1\). At equilibrium, \(\gamma \) should be small enough to guarantee that when the firm refuses the proposed commitments, the CA prefers to start the infringement procedure.

Lemma 2

If the CA proposes commitments \(R^{max}\), there exists \(\tilde{\gamma }\) such that there is a continuum of partial pooling equilibrium in which in State 1, the firm accepts the proposed commitments with probability \(\gamma \in [0, Min[ \tilde{\gamma }, 1]]\) and refuses them with probability \((1-\gamma \)) and, in State 2, the firm always refuses them. In case of refusal, the CA sues the infringer in the formal procedure.

Proof

see “Appendix”.

To be consistent, the selective use of the commitments policy must be such that it is optimal for the CA to start an infringement procedure in the case of refusal i.e. the benefit of starting the infringement procedure must be large enough. To that end, the CA must offer commitments that are refused with some probability in State 1 and the harm may not be perfectly remedied (the remedy must be set at \(R^{max}\)). At the semi-pooling equilibrium, the consumer surplus is:

4.2.3 Generalized commitments policy

The last policy alternative for the CA is to propose commitments \(\tilde{R}\) that would be accepted in both states. Such commitments must satisfy:

Solving Eq. (12), all commitments smaller than \(R^{min}\) will be accepted by the firm in both states. The commitments will clearly be softer. With this pooling mechanism, the firm always agrees on the proposed commitments: in State 1, because the remedy is softer compared to the infringement procedure (and the selective commitments); in State 2, because the firm’s payoff is at most equivalent (on average) to its payoff with the infringement procedure. Assumption 1 guarantees that generalized commitments are credible i.e. should a firm refuse the commitments, it will be formally investigated by the CA at cost c. The consumer surplus is equal to:

4.3 Comparing policies

There is no enforcement policy that manages to implement the first best. With the generalized infringement policy, the CA fails to remedy the competitive harm with probability \((1-p)\) because the case cannot be legally established (false acquittal). Furthermore, the procedure is the most costly. With generalized commitments, a remedy is always applied but it is not state-dependent. The selective commitments policy manages to screen between the two levels of harm at some procedural cost and, eventually, by applying a remedy that does not fully restore the consumer surplus. In this section, we formally compare the three policies, starting with the case where a separating equilibrium exists.Footnote 13

4.3.1 Case 1: \(p\underline{H}\ge c\)

To keep the comparison tractable, we will make two assumptions:

Assumption 2

\(\frac{d+pF}{\alpha }+p\underline{H}\le \overline{H} \le \frac{d+pF}{(1-p)\alpha }\).

Assumption 3

\(\nu \le \frac{1}{2}\).

Assumption 2 implies that \(R^{max}\ge \overline{H}\ge R^{min}\ge \underline{H}\) which means that the first best remedy in State 1 is implementable with the separating commitments policy but not with the generalized commitments policy. Assumption 3 implies that under a generalized commitments policy, the CA implements a remedy \(\tilde{R}=\underline{H}\) i.e. the first best in State 2. Consumer surplus under selective (Eq. 14) and generalized commitments (Eq. 15) is:

Under our assumptions, it is immediate that the selective commitments policy dominates the generalized enforcement policy. In terms of remedy, the policies are equivalent but the selective commitments policy manages to remedy the harm always in State 1 while only with probability p with generalized enforcement and at a higher cost.

Comparing \(\overline{S}\) and \(\tilde{S}\), we establish the following proposition.

Proposition 1

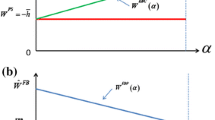

For \(p\underline{H}\ge c\), the optimal enforcement policy is:

-

a selective commitments policy if \(\nu \overline{H}-\underline{H}>0\),

-

a generalized commitments policy if \(\nu \overline{H}-\underline{H}<0\) and \( \nu (\overline{H}-\underline{H})<(1-\nu ) c\),

-

a selective commitments policy for \(p\ge p^*\) and a generalized commitments policy for \(p\le p^*\) if \(\nu \overline{H}-\underline{H}<0\) and \(\nu (\overline{H}-\underline{H})>(1-\nu ) c\), with \(p^*=\frac{c}{\underline{H}}+(1-\frac{\nu }{1-\nu }\frac{\overline{H}-\underline{H}}{\underline{H}})\) and \(p^*\in [\frac{c}{\underline{H}},1]\).

The conditions of Proposition 1 are illustrated in Fig. 1.

The selective commitments policy replicates the generalized infringement policy in State 2 while in State 1, the use of commitments eliminates the risk of false acquittals and the procedure is less costly. Therefore, a generalized infringement policy is not optimal. The choice of a commitments policy, generalized or selective, depends mainly on the underlying case uncertainty. In State 2, the comparison between generalized and selective commitments is a trade-off between risk of false acquittals and cost of procedure as above. In State 1, the firm settles with both policies but the firm takes lower commitments when the CA follows a generalized commitments policy. Commitments fail to fully remedy major harms when they are systematically used. This under enforcement cost is linked to difference between major and minor harms. Indeed, a necessary condition for generalized commitments policy to be optimal is \(\nu \overline{H}-\underline{H}<0\) which can be re-expressed as an upper limit on the difference between major and minor harms: \((\overline{H}-\underline{H}) \le \frac{(1-\nu )}{\nu }\underline{H}\).

We derive two policy implications from this discussion:

-

Policy implication 1 The selective commitments policy is optimal when the uncertainty surrounding the importance of the harm is important and for sufficiently large value of the probability of conviction.

-

Policy implication 2 The generalized commitments policy is optimal when the uncertainty surrounding the importance of the harm is limited.

4.3.2 Case 2: \(p\underline{H}\le c\)

In this second case corresponding to lower values of p, the selective commitments policy is less effective. To be consistent, commitments must be equal to \(\overline{R}=R ^{max}\) which departs from the first best policy. Moreover, commitments are use less often in State 1. These two reasons reduce the surplus associated with the selective commitments policy below \(\bar{S}\) and make the comparisons more complicated. Having said that, we can easily establish that:

Proposition 2

For \(p\underline{H}\le c\), the optimal enforcement policy is a generalized commitments policy if \(\nu \overline{H}-\underline{H}<0\).

The proof is immediate: the condition \(\nu \overline{H}-\underline{H}<0\) guarantees that for \(p=\frac{c}{\underline{H}}\), \(\tilde{S}>\bar{S}>\hat{S}\). Therefore these inequalities must be true for all lower values of p.

If the condition of Proposition 2 does not hold true, then it is possible that a generalized infringement policy is recommendable. For that, a necessary condition is \(\overline{S}\ge \tilde{S}\) i.e. generalized infringement should be preferred to generalized commitments. The condition can be expressed as:

Equation (16) defines a non-empty parameter set if the threshold value of p is smaller than \(p=\frac{c}{\underline{H}}\), that is if: \(c\ge \frac{\underline{H}^2}{\nu (\overline{H}-\underline{H})}\).

Equation (16) is a necessary condition. The generalized infringement policy is optimal if in addition the associated payoff is higher than the payoff at the semi-pooling equilibrium. But this comparison is complicated—and not only because mathematical expressions are complicated—but also because the semi-pooling equilibrium is not uniquely defined. If we take values of \(\gamma \) closes to zero, a selective commitments policy is not different from the generalized infringement policy except that the remedy is \(R^{max}\) and not the first best remedy. Hence, for low values of \(\gamma \), the condition defined in Eq. (16) is also a sufficient condition. For higher values of \(\gamma \), there is no clear comparison. Based on that, we derive a third policy implication.

-

Policy implication 3 The generalized infringement policy is optimal when the uncertainty surrounding the importance of the harm is important and for relatively low values of the probability of conviction.

This result might at first be strange as a low probability of conviction implies that the likelihood of remedying the harm with the infringement procedure is low. However, for low values of p, the selective commitments policy does not work well too. The CA is therefore in a situation where it must choose between screening between major and minor harms but leaving some of them non-remedied (generalized infringement) or remedying all cases but with a soft remedy (generalized commitments). When the uncertainty on the harm is important the first option might be preferred.

5 Extensions

5.1 Alternative timing

In Lemma 1, we derived the conditions for the existence of a fully separating equilibrium when commitments are offered by the non-informed party. In this section we check whether such an equilibrium exists when the informed party—the firm—makes the offer to the CA.Footnote 14 We focus on the following candidate equilibrium: in State 1, the firm offers to take commitments \(\bar{R}\) and the offer is accepted by the CA, while, in State 2, the firm does not propose any commitments and the CA starts an infringement procedure. This constitues a perfect Bayesian equilibrium if the following set of conditions is verified. First, in State 1, the firm should prefer to take commitments \(\bar{R}\) to an infringement procedure and, conversely in State 2, the firm should prefer the infringement procedure to the commitments \(\bar{R}\). These conditions correspond to Eqs. (7) and (8). Second, in State 1, the CA should prefer to accept the proposed commitments \(\bar{R}\) to launching an infringement procedure. Third, in State 2 when the firm does not offer commitments, the CA should prefer to start an infringement procedure rather than closing the case. Last, any other commitments offer (\(R\ne \bar{R}\)) should be refused by the CA. If all these conditions are satisfied, then \((\bar{R},\emptyset )\) is a separating equilibrium. We focus in particular on the following candidate equilibrium \((\bar{R}=\overline{H}, \emptyset )\) that replicates the separating equilibrium described in Lemma 1 when Assumptions 2 and 3 hold true.

Lemma 3

Under Assumptions 2 and 3, a selective commitments policy where the firm proposes commitments \(\overline{R}=\overline{H}\) in State 1 and these commitments are accepted by the CA while, in State 2, the firm does not formulate a commitments offer and the CA starts an infringement procedure is feasible if \(p\underline{H}\ge c\) and \(p\ge \frac{c+\underline{H}}{\nu \overline{H}+(1-\nu ) \underline{H}}\).

Proof

see “Appendix”.

Compared to Lemma 1, the conditions for a separating equilibrium when the firm formulates the commitments offer are more restrictive as it requires an additional condition. But in both frameworks considered, the key for using the procedures to screen between different level of harm is the threat of moving back to the infringement procedure if commitments are not strong enough. When the firm formulates the offer, separation is feasible only if the CA would not accept weaker commitments which restrict further the possibility of having a selective commitments policy.

We can however show that:

Corollary 1

When it exists, the separating equilibrium of Lemma 3 is the optimal enforcement policy.

Proof

This equilibrium gives a payoff of \(\bar{S}\) ; this payoff must be compared with the payoff under a generalized infringement policy \(\hat{S}\) and a generalized commitments policy \(\tilde{S}\). The condition in the lemma guarantees that \(\hat{S}\ge \tilde{S}\). Given that \(\bar{S}\ge \hat{S}\), the result is immediate. \(\square \)

The conditions guaranteeing that a separating equilibrium exists and is optimal are stronger than in the screening case. In case 1 described in Proposition 1, a selective commitments policy is optimal if \(\bar{S}\ge \tilde{S}\). In the corollary, the condition is \(\hat{S} \ge \tilde{S}\). Given that \(\bar{S}\ge \hat{S}\), the condition is stronger meaning that the selective commitments policy is used less often.

Finally, let us consider a generalized commitments policy where the firm offers the same remedy in both states and the proposal is accepted by the CA (which makes the commitments legally binding). Such an equilibrium exists whenever \(\tilde{S}\ge \hat{S}\), i.e when the CA prefers generalized commitments \(\underline{H}\) to the infringement procedure. Indeed, when \(\tilde{S}\ge \hat{S}\) the firm and the CA are better off with a generalized commitments policy compared to a generalized infringement policy. Hence, there exists a pooling equilibrium and this policy is preferred to a general enforcement policy.Footnote 15

Modifying the commitments proposal game changes the optimal enforcement policy described in Proposition 1 as follow:

Proposition 3

In case 1 (\(p\underline{H}\ge c\)), under Assumptions 2 and 3, the optimal enforcement policy when commitments are offered by the firm is :

-

If \(c\le \frac{\underline{H}^2}{\nu (\overline{H}-\underline{H})}\), equivalent to a separating commitments policy for \(p\ge \frac{c+\underline{H}}{\nu \overline{H}+(1-\nu ) \underline{H}}\) and equivalent to a generalized commitments policy \(p\in [\frac{c}{\underline{H}}, \frac{c+\underline{H}}{\nu \overline{H}+(1-\nu ) \underline{H}}]\).

-

Equivalent to a generalized enforcement policy in the other cases.

Proof

The conditions in Lemma 3 define a non-empty set if \(c\le \frac{\underline{H}^2}{\nu (\overline{H}-\underline{H})}\). If this condition is not valid, then the optimal policy is a generalized infringement policy. \(\square \)

For the reasons mentioned above, a different enforcement procedure in the two states is more complicated and therefore, the parameter space in which the selective commitments policy is optimal is reduced. The main quantitative change is that a generalized commitments policy and the generalized enforcement policy will be more often used instead.

5.2 Pro-competitive conduct

In the baseline model, we supposed that the objective of the CA is to screen between two types of harmful conducts causing major or minor harm to consumers. An alternative set-up could be the case where the conduct of the firm could be either anti-competitive causing a harm \(\overline{H}\) to consumers or pro-competitive in which case the action will increase both the firm’s profit and the consumer surplus. In our model, this would correspond to \(\underline{H}<0\). In this alternative set-up, the first best consist in refraining from intervening in State 2 to keep the surplus at \(S-\underline{H}>S\).

With the infringement procedure, the CA inefficiently remedies the pro-competitive conduct in State 2 with probability p but the associated surplus is still given by \(\hat{S}\) in Eq. (5). The main change occurs for the selective commitments procedure. Indeed, when \(\underline{H}<0\), the condition for having a separating equilibrium (\(p\underline{H} \ge c\)) will never be satisfied. The CA will never starts an infringement procedure if it knows that the conduct is pro-competitive for sure and there is no separating equilibrium. Remains the less efficient semi-pooling equilibrium. So, if the CA has to screen between pro and anti competitive conduct, the selective commitments policy is much less effective.

5.3 Deterrence

To complete our analysis, we analyze the deterrence effect of the decisional policy chosen by the CA. To that end, we suppose that there is a continuum of firms and that the firms are heterogeneous with respect to the profit derived from the conduct \(\pi \). We suppose that the distribution of \(\pi \) in the population is given by the positive and continuous density function \(g(\pi )\) on \([0, +\,\infty ]\) and \(G(\pi )\) is the associated cumulative distribution. At a first stage of the game, the firm with type \(\pi \) decides to undertake or not the conduct. Firms that expect a positive surplus from the conduct will undertake it while those expecting a negative surplus will be deterred. Absent the commitments procedure, the firm can expect a profit of \(\nu \hat{\pi }^1+ (1-\nu ) \hat{\pi }^2\), as under Assumption 1, the conduct will be systematically scrutinized by the competition authority. Define \(\hat{\pi }\) as the type \(\pi \) such that \(\nu \hat{\pi }^1+ (1-\nu ) \hat{\pi }^2=0\). All firms characterized by a parameter \(\pi \ge \hat{\pi } \) can expect a positive profit from the conduct while those with \(\pi <\hat{\pi }\) expect a negative profit. Therefore the frequency of the conduct is \(1-G(\hat{\pi })\).

With a selective commitments policy, the firms’ payoff in state 2 is \(\hat{\pi }^2\) while in state 1, the payoff is higher or equal to \(\hat{\pi }^1\). Therefore, the conduct is at least as frequent as \(1-G(\hat{\pi })\). With a generalized commitments policy, the firms’ payoff is at most \(\hat{\pi }^2\). Given that \(\hat{\pi }^2<\hat{\pi }\), the use of this policy encourages more firms to undertake possibly illegal conducts. Note that this under-deterrence effect persists if the firm knows the type before deciding to take the action. This under-deterrence effect of commitments is analyzed in greater details in Choné et al. (2014). They compare the commitments and the infringement procedures considering that commitments immediately restore competition but have no deterrent effect while the adversarial procedure is more time-consuming and the fine reduces the probability of future illegal conduct. The optimal decisional policy trades-off these two dimensions.Footnote 16

The fines imposed in the adversarial procedure play a double role. Firstly, by decreasing \(\hat{\pi }\), fines deter future illegal conduct. Secondly, fines determine the default point for negotiating commitments. Higher fines or a more systematic use of the finesFootnote 17 decrease the firm’s expected payoff in the infringement procedure and thereby increases the commitments that the firm is ready to accept.

6 Discussion of the Commission’s decisional policy

In this section, we provide a preliminary overview of the normative implications of our model. To that end, we have gathered a sample of representative antitrust cases (non cartel) decided by the Commission in the past ten years under Article 7 and Article 9. For the period 2004–2014, the Commission has officially adopted 27 antitrust decisions under the Article 7 infringement procedure and 36 antitrust decisions under the Article 9 commitments procedure. These statistics do not include unpublished decisions. In that sample, we have identified several categories of antitrust cases that can be deemed to belong to a similar category, either in terms of the sector they concern (for instance, energy) or in terms of the theory of liability that was affirmed by the Commission (for instance, margin squeeze). In turn, for each category of case, we have attempted to determine which of the three enforcement policies had been followed by the Commission. This exercise has led us to build the following typology (see Table 1). Our sample leaves aside a number of isolated cases, like for instance the Ebooks case, Siemens/Areva or Rio Tinto which are one off decisional interventions that do not seem to belong to a group of cases and which are thus unhelpful to track a specific enforcement policy pattern.

This crude empirical exercise consists in identifying the enforcement policy followed by the Commission and, in a second step to gain a first understanding of whether the policy followed by the Commission is in line with the findings of our model, in particular given the uncertainty over the importance of the harm and the probability p of conviction that prevailed in those cases. Meanwhile, we concede that we remain, as any outsider, exposed to errors of interpretation and constrained by publicly available information.

6.1 Generalized commitments

As explained previously, there are generalized commitments when the Commission treats all the cases of a certain category under the Article 9 procedure. Put differently, there is a generalized commitments policy when the negotiation of commitments is the sole issue for a certain type of case. This is the policy followed in abuse of dominance cases in the energy sector or in relation to specific practices that the Commission has declared non-priority targets, such as exploitative abuses of dominant position (European Commission 2009). According to our policy conclusions, such a policy is appropriate when there is little uncertainty on the relative importance of the harm.

6.1.1 Energy

In the electricity and gas sectors, the Commission’s decisional practice is clear. The conventional procedural route to handle such cases is the discussion of commitments (Wils 2015). In 10 cases, the Commission closed abuse of dominance proceedings with commitments. Of course, there is an exception to this (OPCOM).

The Commission’s lack of information may be less marked here than in other sectors. First, the Commission’s investigations in this sector often deal with incumbents’ conduct whose dominant position is so obvious that a large component of potential harm is established. Second, in the energy sector, the Commission enjoys a historically rich factual expertise, following the wide ranging “sector inquiry”that was completed in 2007. Third, in energy markets, the Commission works in complementarity with 28 national regulatory authorities in gas and electricity. This unique institutional specificity has informational merits, for the Commission can rely on the assistance of those institutions to gather updated market data and expert opinions on energy-related issues.

Regarding the probability of making legally the case there are, of course, endogenously not many precedents from the EU courts in the energy sector. On close examination, most if not all of the practices at hand in the energy sector seem to concern classic theories of antitrust liability. Our model suggests that a a high p and a limited uncertainty on harm make the generalized commitments policy appropriate for the energy sector.

6.1.2 Non-priority cases (excessive pricing)

A second illustration of the generalized commitments policy can be found in non-priority cases. A good illustration of this relates to exploitative abuses, and in particular excessive pricing for which the Commission expressly manifested a lack of interest in its 2009 Guidance Paper on enforcement priorities (European Commission 2009) and all cases (S&P and Rambus) were thus handled under the Article 9 procedure.

In Rambus, the Commission expressed concerns that Rambus Inc. might have abused a dominant position by intentionally concealing from the JEDEC SSO—in which Rambus participated—that it had patents and patent applications which were relevant to technology used in DRAM standardsFootnote 18 being adopted by JEDEC, and subsequently claiming unreasonable royalties for those patents from suppliers of DRAM products. The Commission’s view was that absent its intentionally deceptive conduct, Rambus would not have been able to charge the royalties it subsequently did. The Commission eventually closed its investigation by adopting an Article 9 decision that rendered legally binding commitments offered by Rambus including a promise to cap the royalties that it would charge for certain patents essential for those DRAM products.

In S&P, the Commission scrutinized the prices charged by Standard & Poor’s for the distribution of International Securities Identification Numbers (ISINs) in Europe to information service providers (news agencies) and financial institutions (banks, etc.). S&P has been designated by the American Bankers Association as the competent National Numbering Agency and as such enjoyed a monopoly for distribution of US ISINs. The Commission had concerns that S&P may have charged unfairly high prices for the distribution of US ISINs in Europe in breach of EU antitrust rules on the abuse of a dominant market position. However, it brought the case to a settlement.

Excessive pricing cases do not generate much discussion relative to the illegality of the conduct. Article 102(a) prohibits dominant firms from directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchase or selling prices or other unfair trading conditions. And it is historically clear that this provision provides a textual legal basis to catch dominant firm’s exploitative prices. Since the late 1970s, the case-law has confirmed that EU competition agencies and courts could administer Article 102(a) to curb dominant firms’ exploitative prices (United Brands; AKKA/LAA). The fact that the Commission has made little use of it is simply a deliberate policy choice.

Excessive pricing cases generate more debates in terms of the harm to competition. First, there is a widespread view that competition authorities lack the information and expertise necessary—particularly on the competitive price and on costs levels—to carry out price controls (Fisher and McGowan 1983). Accordingly, this task would be better left to sector-specific regulators (Motta and de Streel 2006). Second, there is a complete uncertainty on the incentive effects of high prices. In particular, the view that high prices are self-correcting remains quite widespread, and that if competition agencies were ever to apply Article 102(a) to dominant firms’ prices, they might deter competitive entry, and therefore undermine the dynamic nature of the competitive process (Gal 2004; Evans and Padilla 2005).

Our model suggests that a high level of uncertainty creates a risk of under-remediation. This is certainly a concern in Rambus. In that case, there was high uncertainty because licensing rates for patented products are in principle secret and the incentives effects are high when it comes to patented, technology-driven products. That explains why the Commission possibly under-remedied the case, by setting a 1.5% cap for future standards, leaving untouched the past harm inflicted by Rambus through patent harm. Moreover, there is evidence that many of Rambus’ licensing rates were below 1.5%, so the remedy did not change much to the firm’s licensing conduct. In contrast, in S&P, there was less uncertainty on the appropriate licensing level. The Commission could therefore do little harm by mandating in a decision a licensing level known by all market players to be the industry norm.

6.2 Selective commitments

The selective commitments policy is applied when the Commission entertains commitments talks with the parties, but maintains an effective threat to return to the infringement procedure. We consider this policy to be appropriate when the uncertainty on the harm is important and when the probability of conviction is relatively high.

6.2.1 Standard essential patents

The Samsung and Motorola decisions are a good example of a selective commitments policy. By way of reminder, those two cases arose in the context of the so-called smartphone war. Back in 2011, Apple ignited a worldwide patent war with Samsung for alleged infringement of several design patents. Samsung replicated by starting patent litigation in several European countries. In defense, Apple thus argued that Samsung’s actions for infringement were a violation of its FRAND promises and this was in turn akin to an unlawful abuse of a dominant position. Apple subsequently lodged abuse of dominance complaints against Samsung before the Commission, arguing that Samsung was using courts proceedings as a bargaining device, to extract from Apple supra-competitive licensing terms, a strategy known as “patent holdup”(Shapiro 2001). Apple also lodged similar complaints against Motorola.

In April 2014, the Commission adopted two decisions in those cases. The decision in the Samsung case is based on Article 9. With it, the Commission closed the case, in exchange for a commitment by Samsung to stop seeking injunctions in court, and to abide by a predetermined 12 months licensing framework. In contrast, the decision against Motorola is an Article 7 decision that finds Motorola guilty of an infringement of Article 102 TFEU, and that orders Motorola to cease seeking injunctions in court on the basis of the litigious SEPs.

Interestingly, since Apple’s initial complaints of 2011 the Commission ran both cases in parallel, though under distinct procedures. In this, the two cases are an example of selective commitments, because the firm that was discussing commitments with the Commission under Article 9—Samsung—could credibly anticipate that a failure to reach commitments would expose it to a return to the Article 7 procedure, as this procedure was the one followed with Motorola in parallel investigation.

If we review those cases through the lenses of our model, it is strikingly clear that the uncertainty regarding the possibility to declare the conduct unlawful is high and that these cases are characterized by a low value of p. As mentioned in several official papers, the legal standard applicable to the seeking of injunctions in Courts remained uncertain (Pentheroudakis 2015). Several tests competed in the case-law of the EU courts (Petit 2013; Jones 2013). Even more importantly, the uncertainty was empirically confirmed when two German courts in Dusseldorf and Mannheïm addressed requests for clarification to the Court of Justice of the European Union and to the EU Commission, respectively.Footnote 19

Regarding the importance of the harm, the discussion is less easy. To some extent, one must consider that the facts are well-established, given that it is easy to prove whether the companies have, or not, sought injunctions and have, or not, made FRAND pledges. Moreover, the relevant markets and the dominant position should be easy to establish, because the existence of a SEP gives rise to a licensing market on which the patent holder is likely dominant. The main uncertainty concerns the harm inflicted to rivals. The rate of award of injunctions by courts is indeed unclear. There is thus some uncertainty as to whether SEPs holder can at all resort to injunctions in order to extract supra competitive royalties or cross-licensing terms (hold up) or exclude as efficient rivals (foreclosure).

On close examination, the outcome of the Article 9 Samsung case is more severe than the outcome of the Article 7 Motorola case. Whilst in Motorola, the Commission merely found an infringement and ordered Motorola to cease and desist without fines, in Samsung, the commitments decision forces Samsung to comply with a predefined licensing framework under the threat of fines. Moreover, Motorola has kept its right to appeal the decision before the General Court whilst Samsung has lost it with the commitments decision.

This is in line with our model that predicts that, with selective commitments, stronger remedies are applied for the cases closed with commitments and weaker ones for cases closed with an infringement decision. It remains to establish whether these different outcomes reflect some underlying factual differences between the cases or are due to another source of heterogeneity between firms.

6.2.2 Multilateral interbank fees

The Visa decision of 2002 and the MasterCard decision of 2007 are again illustrations of the selective commitments policy. In the first decision, the Commission exempted Visa’s multilateral interbank fees model under conditions. In the second decision, it found that MasterCard had violated Article 101 TFEU, by setting on behalf of its members (i.e. banks) multilateral interbank fees (MIFs). Since then, the Commission opened two additional investigations against MasterCard and Visa, in relation to other types of MIFs and rules set by both cards’ systems. Both investigations concerned similar practices, according to the Commissions own declarations. In 2010 (and subsequently in 2014), the Commission closed the Visa case yet with another Article 9 commitments decision. The case against MasterCard is still ongoing, under the Article 7 procedural route.

The MIFs cases primarily deserve discussion in terms of probability of conviction. There is little risk on the applicability of Article 101 to MIFs. As early as 2001, the Visa grouping had itself notified its regulations to the Commission, conceding the applicability of Article 101 to their regulations, but advocating a possible exoneration on the ground that the MIFs anticompetitive effects were unclear and outweighed by redeeming efficiency benefits.

In contrast, the uncertainty relative to the harm to consumers surrounding those cases was high. Economists disagree on the opportunity to launch antitrust actions against card networks (Wright 2012) and on the welfare effect of regulating MIFs (Rochet and Tirole 2011). Furthermore, in several instances, the Commission admitted implicitly that it enjoyed a poor degree of factual information on the welfare effects of MIFs, and in particular on the possibility that MIFs yield efficiencies. This is strikingly clear from the decision of the EU Commission, in 2007, to open a sector inquiry into retail banking targeting, in particular, the level of interchange fees.

According to our model, when p is high, using the commitments procedure selectively is appropriate even tough the uncertainty on the harm is important as it is the practice for the MIFs-related cases. Conversely, when p is low as in the SEP-related cases, selective commitments are not appropriate and it is rather recommended to use a generalized infringement or a generalized commitments policy depending on the uncertainty on harm.

6.3 Generalized infringement procedure

Besides cartels (they are in principle excluded from the commitments procedure) the infringement procedure in modern EU competition law has been applied in two categories of cases, margin squeeze cases in the telecommunications sector and pay-for-delay cases in the pharmaceutical sector. Before we discuss them, recall that there is no reason to apply a generalized infringement procedure when p is high; it is rather recommended to use such an enforcement policy for low values of p combined with a high uncertainty on the damage.

6.4 Margin squeeze

A margin squeeze occurs when a dominant infrastructure provider adjusts its wholesale access rates and its retail prices in order to force rival input purchasers to compete at a loss on the retail market. In the early 2000s, entrants in the newly liberalized EU telecommunications markets increasingly complained before the Commission that incumbent players were using margin squeeze strategies to force them off the market. After 2004, the Commission opened three distinct margin squeeze cases all being dealt with under Article 7 (Telefonica S.A.; Telekomunikacja Polska; Slovak Telekom).

As for the energy cases, sector-specific regulators monitor the industry on a daily basis, and are subject to EU oversight, under the Framework Directive on electronic communications. It can thus be safely assumed that the Commission enjoyed as much factual information as it needed on those cases.

However, from a legal standpoint, the early margin squeeze allegations lodged with the Commission did not fall neatly within existing theories of antitrust liability. In margin squeeze cases, the retail prices are above cost, so it is difficult to analyze them under the precedent applicable to predatory pricing cases. Moreover, in a margin squeeze case, the dominant firm actually grants access to its infrastructure, so the case-law on refusal of access to an essential facility is not applicable. With this background, and absent a precedent of the Court of Justice of the EU confirming that margin squeezes could be deemed abusive, the Commission thus choose to cast margin squeeze cases under the infringement procedure. Interestingly, the probability of conviction increased dramatically in October 2010, when the Court of Justice held in Deutsche Telekom v Commission that margin squeezes could, under certain conditions, breach Article 102 TFEU. The Court of Justice repeated the statement in TeliaSonera in 2011, insisting at §56 that margin squeezes are a novel, “independent”form of abuse, “distinct”from the conventional abuses known in EU competition law, and in particular of refusals to supply. According to our model, it is expected that future cases will be dealt under Article 9 and a generalized commitments policy.

6.5 Pay-for-delay

Similarly, the infringement procedure also appears to be the predominant one in pharmaceutical cases, and in particular in pay-for-delay cases. In Lundbeck, Johnson&Johnson and Servier, the Commission issued article 101 and/or 102 TFEU infringement decisions against pharmaceutical companies that sought to delay generic entry into the market. In those cases, a drug originator had paid generic entrants to stay off the market after the expiry of its patent (and possibly before). None of those cases were dealt with under the Article 9 procedure. And all gave rise to significant fines.

Like in the telecommunications sector, the pay-for-delay cases did not occur in a high uncertainty context. In 2007, the Commission launched a wide ranging sector inquiry in the pharmaceutical sector and published the findings of this investigation in 2009. Its report explained that it had garnered evidence that originators had entered into pay for delay settlements with generic firms. It announced that such settlements would in the future be subject to “focused monitoring”, by subjecting pharmaceutical players to mandatory reporting requirements on a periodic basis.

In contrast, in the scholarship and in practice, a fierce amount of discussion took place on the applicable legal test, and in particular on whether those new cases should be dealt with under the rule of reason or under a per se prohibition regime (Cotter 2004; Carrier 2009). The decision of the US Supreme Court to grant certiorari in the Actavis case in 2014 bears testimony to the high degree of uncertainty that prevailed at the time. It suggests that “pay-for-delay”were new for which an authoritative clarification was needed. The US Supreme Court eventually held that pay for delay cases ought to be treated under the rule of reason. In the EU, no similar judicial precedent existed. With this important uncertainty on the probability of conviction, the selective commitments policy seemed highly risky and the Commission decided to treat these cases under the Article 7 framework.

7 Concluding remarks

In this paper, we have shown that the commitments procedure does not fully replicate the outcome of the infringement procedure, and that under some conditions, it may lead to under enforcement of the EU competition rules because the remedies applied by the Commission do not entirely eradicate the anticompetitive harm caused by the impugned practice. In brief, the remedies administered by the Commission are under-fixing. However, the use commitments may address concerns that cannot be solved in the adversarial procedure where some harmful conducts cannot be prohibited.

A critical feature of our paper is to explain that the optimal enforcement policy depends on the uncertainty that surrounds the interaction between the agency and the firm. With this, we are able to formulate a number of policy recommendations that could help agencies refine their enforcement strategies with a view to achieving a more optimal enforcement mix.

More fundamentally, our findings pave way for further research. Firstly, in the future, we intend to improve our understanding of the determinants of uncertainty. For instance, we will try to integrate the existence of complaints. The existence of complaints is indeed likely to reduce uncertainty, because complainants can supply the Commission with whatever industry data it needs.Footnote 20 Similarly, the fact that the Commission has issued a Statement of Objections (or a Letter of Facts or Supplementary Statement of Objections) should also be integrated in our model, for it also likely diminishes uncertainty (in addition to increasing the reluctance of the Commission to abandon the Article 7 track). Finally, the presence in the industry of a sector specific regulator could be factored-in. A sector-specific regulator reduces uncertainty because regulators and antitrust agencies often cooperate.

Secondly, we tend to believe that our model could reach a higher degree of granularity in relation to the probability of conviction in the sense that a distinction could be drawn between Article 101 and Article 102 TFEU cases. In particular, the application of “rule of reason” type analysis or the admission of efficiency defenses is more widespread in Article 101 cases than in Article 102 cases. In turn, this suggests that the probability of conviction may be lower in Article 101 TFEU cases than in Article 102 TFEU cases. On the other hand, there is a considerable amount of soft law guidance under Article 101 TFEU, and the rate of success of appeals in Article 101 TFEU cases is certainly higher than in Article 102 TFEU cases (which are only rarely dismissed by the Court of Justice, though the 2017 judgment in Intel may alter that trend in the future). Finally, our model could reach a higher degree of accuracy within the Article 102 cases by distinguishing between exclusionary abuse cases and exploitative abuse cases, for the later are often deemed to generate insuperable evidentiary issues. By the same token, our analysis of the Article 101 TFEU cases could distinguish between horizontal and vertical cases, for the later are generally smaller cases, where uncertainty is presumably lower.

Lastly, we hope to enrich our model so as to control for the bargaining dynamics inherent in the negotiation of commitments. We already test the relevance of who is the first to make the offer to negotiate commitments, i.e. the Commission or the firm but the information structure is considered to be the same in the signaling and the screening procedure. The model could be enriched to integrate parameters such as the intensity of judicial review, the number of formal complainants to the procedure, the existence of parallel cases with the same firm, be it before the Commission, other agencies or before the EU Courts, etc. All those factors, and others, potentially affect the Commission and the parties’ bargaining power and more fundamentally the bargaining process itself.

Notes

See Schweitzer (2009) for a complete description.

Even though in some cases commitments cases last longer than conventional infringement cases, e.g. Rio Tinto which lasted almost 5 years.

In Alrosa, the leading case on commitments, the EU Court of justice justified the use of the commitments by “consideration of procedural economy”(Wagner-Von Papp 2012).

This is the model initially suggested in the Regulation 1/2003 as interpreted by most competition scholars. In this variant, firms that have violated the antitrust rules know that they can face both types of proceedings.

As part of our standard practice in an Article 9 procedure which leads to a commitments decision and in response to our pre-rejection letters sent before the summer, some of the twenty formal complainants have given us fresh evidence and solid arguments against several aspects of the latest proposals put forward by Google. At the beginning of the month, I have communicated this to the company asking them to improve its proposals. We now need to see if Google can address these issues and allay our concerns. If Google’s reply goes in the right direction, Article 9 proceedings will continue. Otherwise, the logical next step is to prepare a Statement of Objections. Presentation of the Annual Competition Report to the European Parliament by the Commissioner J. Almunia, Sept. 23, 2014. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-14-615_en.htm.

The different deterrent effect of settlements and trials has been recognized by Polinsky and Rubinfeld (1988).

Whilst in theory, the commitments must be offered at the parties’ initiative, the practice is that the Commission will often manifest that it is ready to enter in settlement talks with the parties. In the literature, most observers confirm that the Commission has some control over the choice of the procedural route (Mariniello 2014).

As the firm has the possibility to appeal against an infringement decision, the conduct is deemed illegal only after its confirmation in appeal (should the firm decides to appeal). In our model, we do not distinguish the first instance and the appeal level and the probability p should be understood as the probability of establishing legally the infringement at the end of the legal process.

For instance, in the Velux case, the Commission concluded that the rebates offered by the suspected dominant company were not anti-competitive (Neven and de la Mano 2010). Qualcomm, Apple iTunes and MathWorks are other examples of cases that the Commission closed without finding an unlawful anticompetitive practice, sometimes after long investigations.

In practice, fines includes a basic amount for committing the infringement, an amount related to the value of sales connected with the infringement multiplied by the number of years the infringement has been taking place and a possible adjustment for mitigating or aggravating circumstances.

If the probability of conviction is different in the two states and \(p_1\ge p_2\) i.e. it is legally easier to convince the firm when it is responsible of a major damage, then it is more difficult to make the selective commitments policy time-consistent.

Comparison of the preferred institutional regime to address anti-competitive concerns is a classical, see for example Lagerlöf and Heidhues (2005) for the case of efficiency defense in merger control.

The existence of a separating equilibrium when commitments are proposed by the firm is far from being guaranteed, see Polo and Rey (2016) for an analysis of commitments as a signaling game.

To be more precise, there is a continuum of pooling equilibrium to which the commitments \(\underline{H}\) belongs to.

Though it might be difficult to commit to a given decisional policy (see also Wils (2006) on this point).

Actual decisional practices show that fines are not systematically imposed (e.g. Motorola).

“Dynamic Random Access Memory”is a memory chip technology.

In addition, some courts in the Member States have crafted new and distinct tests to deal with such cases (the German Supreme Court has for instance elaborated a novel legal theory called the Orange Book Standard to deal with such cases).

On the other hand, Wagner-Von Papp (2012) argues that complaints give rise to a risk of the Commission becoming the agent of third parties, and in in turn of disproportionate remedies.

References

Bebchuk, L. A. (1984). Litigation and settlement under imperfect information. The RAND Journal of Economics, 15(3), 404–416.

Bellis, J.-F. (2013). Article 102 TFEU: The case for a remedial enforcement model along the lines of section 5 of the FTC act. Concurrences, 1, 54–61.

Carrier, M. (2009). Unsettling drug patent settlements: A framework for presumptive illegality. Michigan Law Review, 108(37), 37–80.

Choné, P., Souam, S., & Vialfont, A. (2014). On the optimal use of commitments decisions under European competition law. International Review of Law and Economics, 37, 169–179.

Cotter, T. (2004). Antitrust implications of patent settlements involving reverse payments: Defending a rebuttable presumption of illegality in light of some recent scholarship. Antitrust Law Journal, 71(3), 1069–1097.

Daughety, A., & Reinganum, J. (1993). Endogenous sequencing in models of settlement and litigation. Journal of Law, Economics & Organization, 9(2), 314–348.

Evans, D., & Padilla, J. (2005). Excessive prices: Using economics to define administrable legal rules. Journal of Competition Law & Economics, 1(1), 97–122.

European Commission. (2009). Guidance on the commission’s enforcement priorities in applying article 82 of the EC treaty to abusive exclusionary conduct by dominant undertakings. Official Journal of the European Union 2009/C 45/02.

Fisher, F., & McGowan, J. (1983). On the misuse of accounting rates of return to infer monopoly profits. American Economic Review, 73(1), 82–97.

Gal, M. (2004). Monopoly pricing as an antitrust offense in the U.S. and the EC: Two systems of belief about monopoly. Antitrust Bulletin, 49, 343–384.

Hyman, D., & Kovacic, W. (2012). Competition agency design: What’s on the menu? GWU legal studies research paper no. 2012-135.

Hyman, D., & Kovacic, W. (2013). Competition agencies with complex policy portfolios: Divide or conquer? GWU legal studies research paper no. 2012-70.

Jones, A. (2013). Standard-essential patents: FRAND commitments injunctions and the smartphone wars. European Competition Journal, 10(1), 1–36.

Kastoulacos, Y., & Ulph, D. (2016). Legal uncertainty, competition law enforcement and optimal penalties. European Journal of Law and Economics, 41(2), 255–282.