Abstract

The aim of our study was to assess the association between green tea consumption and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a pooled analysis of eight Japanese population-based cohort studies. Pooled hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), derived from random effects models, were used to evaluate the associations between green tea consumption, based on self-report at baseline, and risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality. During a mean follow-up of 17.3 years, among 313,381 persons, 52,943 deaths occurred. Compared with individuals who consumed < 1 cup/day, those in the highest consumption category (≥ 5 cups/day) had a decreased risk of all-cause mortality [the multivariate-adjusted HR was 0.90 (95% CI 0.87–0.94) for men and 0.82 (0.74–0.90) for women]. A similar inverse association was observed for heart disease mortality [HR 0.82 (0.75–0.90) for men, and 0.75 (0.68–0.84) for women], and cerebrovascular disease mortality [HR 0.76 (0.68–0.85) for men, and 0.78 (0.68–0.89) for women]. Among women, green tea consumption was associated with decreased risk of total cancer mortality: 0.89 (0.83–0.96) for the 1–2 cups/day category and 0.91 (0.85–0.98) for the 3–4 cups/day category. Results for respiratory disease mortality were [HR 0.75 (0.61–0.94)] among 3–4 cup daily consumers and [HR 0.66 (0.55–0.79)] for ≥ 5 cups/day. Higher consumption of green tea is associated with lower risk for all-cause mortality in Japanese, especially for heart and cerebrovascular disease. Moderate consumption decreased the risk of total cancer and respiratory disease mortality in women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Brewed tea is considered to be the second most common drink globally after water [1]. Teas from the Camellia sinensis plant include: black, green, oolong, and white tea [2]. Green tea is particularly popular in East Asian countries including Japan, and some other countries in North Africa and the Middle East [1]. In Japan, over 50% of adults consume green tea on a daily basis [3], making it an important part of Japanese lifestyle, especially in the old generations.

Several previous prospective cohort studies in Japan have reported an inverse association between green tea consumption and all-cause mortality, with varied magnitude of risk reduction (up to 50%) observed for habitual tea consumers [4, 5]. However, mixed findings have been reported for cause-specific mortality in relation to green tea. Green tea appears to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease mortality [6], such as stroke [7,8,9]. The association of green tea with overall cancer risk remains inconclusive [2, 10, 11], and contradicting results were reported for site-specific cancers including esophageal and lung cancer [12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

To better characterize health benefits of green tea, we assessed the association between green tea consumption and risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality (cancer, heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, respiratory disease, and accidents and injuries), on the basis of a pooled analysis of eight population-based cohort studies in Japan. In these cohorts most participants daily consumed green tea compared to Chinese or black tea [19].

Methods

Study population

Since 2006, the Research Group for the Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan has been conducting pooled analyses of cohort studies [20]. The aim of the Research Group is to evaluate the associations between lifestyle factors and cancer or other causes of mortality in the Japanese population. Potential cohorts were identified from the Japan Cohort Consortium, which is comprised of 10 cohorts including over 500,000 participants [20]. For the present analysis, cohort inclusion criteria were defined as follows: Japanese population-based cohorts with over 30,000 enrollees that commenced in the 1980s and 1990s, use of a validated questionnaire (details of validation included under exposure assessment) to obtain baseline data on green tea consumption, and the availability of follow-up data on cause-specific mortality. As a result, eight Japanese population-based cohort studies were eligible for the present analysis: (1) the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study-I (JPHC-I) [21], (2) the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study-II (JPHC-II) [21], (3) the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study (JACC) [22], (4) the Miyagi Cohort Study (MIYAGI) [23], (5) the Ohsaki National Health Insurance Cohort Study (OHSAKI) [24], (6) the Three-Prefecture Cohort Study—Miyagi portion (3-pref MIYAGI) [25], (7) the Three-Prefecture Cohort Study—Aichi portion (3-pref AICHI) [25], and (8) the Three-Prefecture Cohort Study—Osaka portion (3-pref OSAKA) [25]. Follow-up from the start of each cohort baseline survey to end of follow-up varied across cohorts: JPHC-I (1990 to 2011), JPHC-II (1993–1994 to 2011), JACC (1998–1990 to 2009), MIYAGI (1990 to 2013), OHSAKI (1994 to 2008), 3-pref MIYAGI (1984 to 1998), 3-pref AICHI (1985 to 2000), and 3-pref OSAKA (1983 to 2000).

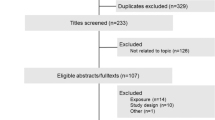

Participants were excluded if they had missing information on sex, age, area (only for JPHC and JACC studies), green tea intake, and history of cancer, stroke, or past myocardial infarction at baseline (Fig. 1). Studies were approved by the relevant institutional ethics review boards. The JPHC [19] and OHSAKI [4] studies have published papers on the association between green tea consumption and all-cause and cause-specific mortality. However, we re-analyzed the associations using more recent datasets from these cohorts.

Exposure assessment

All eight cohort studies included a self-administered questionnaire on lifestyle factors, including dietary habits. The baseline questionnaires contained questions on frequency and quantity of green tea intake. The frequency was classified into four categories: < 1, 1–2, 3–4, and ≥ 5 cups per day, which were the most commonly used categories across all included cohort studies. (Online Resource 1 and 4). Among the cohorts which reported results, only a small portion of participants never drank green tea in the: 16.6% (JPHC-I), 8% (JPHC-II), 7% (OHSAKI) and 5% (Miyagi) [26], while 18.2% (JPHC-I), 10.7% (JPHC-II), 19% (OHSAKI) and 14% (Miyagi) [26] reported occasionally drinking tea [4, 19]. Therefore these two categories were combined into one category (< 1 cup/day) [19]. Green tea in Japan is almost exclusively consumed without the addition of milk or sugar.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients between questionnaires and dietary records were used to assess validity of green tea consumption-related questions. The correlation coefficients were 0.57 for men and 0.63 for women in JPHC-I [27] and 0.37 and 0.43, respectively in JPHC-II [19, 28], 0.47 in JACC [3], 0.71 for men and 0.53 for women for OHSAKI [4, 29], and 0.71 for men and 0.53 for women in MIYAGI and 3-pref MIYAGI [29]. For 3-pref AICHI and 3-pref OSAKA, information on validation of green tea drinking was not available. However these studies asked the same green tea consumption questions as 3-pref MIYAGI [30] (Online Resource 4).

Covariate assessment

Covariate data, such as body mass index (BMI), history of diabetes and hypertension, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and coffee intake, were collected from each participating cohort. BMI was calculated as self-reported weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared at baseline. History of diabetes and hypertension was self-reported. Smoking status (never, former and current), and number of cigarettes smoked per day among current smokers were available for all participating cohorts. Alcohol consumption was quantified as ethanol intake in grams/day, based on frequency and standard portions (“go” = 180 ml or equivalent bottle of beer or glass of wine) in each cohort.

Outcome ascertainment

We assessed the associations between green tea consumption and risk for all-cause mortality and five leading causes of death in Japan (11): cancer (C00–C97), heart disease (I20–I52), cerebrovascular disease (I60–I69), respiratory disease (J10–J18 and J40–J47), and accidents and injuries (V01–X59, X60–X84, X85–Y09, and Y85–Y86). The underlying causes were recorded from death certificates compiled in the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and they were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) [31].

Statistical analysis

Person-years of follow-up were calculated using the date of the baseline surveys until the date of death or end of follow-up, whichever occurred first. Hazard ratios were estimated using a cox proportional hazards model and two-sided 95% confidence intervals for each study, with < 1 cup/day serving as the reference category. Given possible between- and within-study variations, we applied a random effects model to obtain a pooled hazard ratio estimate from the individual studies [32]. Four studies included in this pooled analysis concluded results varied between men and women, therefore we have stratified analyses by sex [4, 19, 33]. All analyses were adjusted for age at baseline (years, continuous), area (for JPHC-I, JPHC-II and JACC), smoking status [men: never, former, current (< 20 cigarettes/day, ≥ 20 cigarettes/day); women: never, former, current], alcohol intake [men: none (never/former), < once/week, regular (grams of ethanol/day) (< 23, 23 to < 46, 46 to < 69, 69 to < 92, ≥ 92); women: none (never/former), < once/week, regular (grams of ethanol/day) (< 23, ≥ 23)], BMI [kg/m2(< 18.5, 18.5 to < 25, 25 to < 30, ≥ 30)], history of diabetes (yes, no) and hypertension (yes, no), and coffee intake (cups/day). Individuals with a BMI (kg/m2) of < 14 or ≥ 40 were excluded as these are considered outliers in the Japanese context. To address reverse causality, we performed sensitivity analyses in which deaths occurring within 5 years of follow-up were excluded. We repeated analyses stratified by smoking status (current, never), for cause-specific outcomes in female non-smokers (Online Resource 3). Former smokers were excluded from this analysis. We also stratified by duration of follow-up (< 15 or ≥ 15 years) for all cause-mortality (Online Resource 2a–f).

Models were analyzed separately in each cohort. Subsequently a meta-analysis was performed using random effects models. Heterogeneity among studies was tested using Q statistics [32]. I2 statistics for highest versus reference category indicated the hazard ratio variation (in percentage) as a result of between-study heterogeneity [34]. STATA Version 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

The current pooled analysis included 313,381 participants (144,750 men and 168,631 women), aged over 40 years at baseline. During an average follow-up of 17.3 years, 52,943 deaths occurred (19,495 from cancer, 7321 from heart disease, 6387 from cerebrovascular disease, 3490 from respiratory disease, and 3382 from accidents and injuries) (Tables 1, 2, 3).

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of the populations in each Japanese cohort study (Online Resource 1). In all cohorts, age was greater than 40 years at the time of the baseline survey. The total population before exclusions consisted of 454,235 participants ranging from 31,345 (MIYAGI-II) to 110,585 (JACC). The response rate for the baseline questionnaire was greater than 80% in all included studies (average response rate: 87%). The exclusion rate was 34.52%, calculated as participants excluded from the current analysis in comparison to total participants enrolled in cohort studies initially (Fig. 1). We do not have data for all cohorts, however based on the JPHC studies, non-responders were similar to participants responding to the questionnaires [35, 36] which made up the largest portion of those excluded.

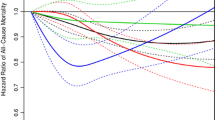

Overall, green tea consumption was associated with decreased risk of all-cause mortality in both sexes (Tables 2, 3). The inverse association was similar after stratifying by duration of follow-up in me both men and women (Online Resource 2). Among men, compared with individuals who consumed < 1 cup/day, the multivariate-adjusted HRs were 0.95 (0.92–0.98), 0.93 (0.89–0.97), and 0.90 (0.87–0.94) for individuals who consumed 1–2, 3–4, and ≥ 5 cups/day, respectively. Among women, the corresponding multivariate-adjusted HRs were 0.90 (0.85–0.95), 0.84 (0.77–0.92), and 0.82 (0.74–0.90) respectively. After excluding deaths within 5 years after the start of follow-up, these inverse associations remained consistent among women, while associations seemed attenuated among men who consumed the 1–2 and 3–4 cups/day. Results were similar in the subgroup analysis restricted to women who had never smoked before. For men, significant associations were only noted among never smokers with consumption of ≥ 5 cups/day, and among never smokers and current smokers with consumption of 3–4 cups/day.

Green tea consumption was inversely associated with heart disease mortality in men. For men who consumed 3–4 and ≥ 5 cups of green tea per day inverse associations were observed [HR (95% CI) 0.83 (0.75–0.91), and 0.82 (0.75–0.90), respectively]. In women, inverse associations with all three consumption categories were observed: HR (95% CI) was 0.80 (0.69–0.93) for 1–2 cups/day, 0.78 (0.67–0.90) for 3–4 cups/day, and 0.75 (0.68–0.84) for ≥ 5 cups/day.

Cerebrovascular disease mortality was associated with green tea in both sexes: for men, HR (95% CI) was 0.85 (0.76–0.95) for 1–2 cups/day; 0.79 (0.70–0.91) for 3–4 cups/day; and 0.76 (0.68–0.85) for ≥ 5 cups/day 0.76; for women, 0.83 (0.72–0.96) for 3–4 cups/day, and 0.78 (0.68–0.89) for ≥ 5 cups/day.

A risk reduction was observed for overall cancer mortality among women: HR (95% CI) was 0.89 (0.83–0.96) for 1–2 cups/day, 0.91 (0.85– 0.98) for 3–4 cups/day. In Table 2, the results for cancer in men suggest a weak increased risk: HR (95% CI) was 1.02 (0.96–1.08) for 1–2 cups/day, 1.02 (0.95–1.10) for 3–4 cups/day, and 1.06 (0.99–1.14) for ≥ 5 cups/day. Green tea was associated with decreased risk of death from respiratory disease in women only: HR (95% CI) was 0.75 (0.61–0.94) for 3–4 cups/day, and 0.66 (0.55–0.79) for ≥ 5 cups/day.

Discussion

In this pooled analysis including eight Japanese representative cohorts, green tea consumption was associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality, as well as cause-specific mortality, including heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, in both men and women. In addition, green tea was inversely associated with risk of total cancer mortality and respiratory disease mortality in women.

For women the risk reduction was slightly greater in the cohorts with shorter follow-up periods (< 15 years) in the 3–4 cups/day ≥ 5 cups/day consumption categories. Of individual cohorts, five cohorts reported a risk reduction ranging from 8 to 16% in men and 17–35% in women in the highest consumption category (Online Resource 2). Based on the results presented in the Online Resource 2 a clearer risk reduction emerged in this pooled analysis compared with the individual cohort results.

The association between green tea consumption and all-cause mortality among Japanese may be confounded by age, alcohol intake, coffee consumption, diabetes, hypertension, physical activity, and smoking, although the role of alcohol, BMI, and smoking is inconclusive [4, 19, 33]. Previous Japanese studies found frequent green tea consumers are less likely to habitually consume coffee [4, 19, 37, 38]. In the Japanese context, people who consumed more green tea were more likely to engage in sports [4, 19, 33]. Relevant questions in the individual cohorts included in this analysis are not comparable, therefore we did not adjust for sedentarism or sports. Family history of first-degree relatives is relevant, however comprehensive data was not collected in all included cohorts. The observed inverse association between green tea intake and all-cause mortality may be a true association and not confounded by water consumption. Typically Japanese in these cohorts drink tea and almost no water [39, 40].

A 2015 meta-analysis and two more recent Chinese studies support our findings that green tea consumption reduces the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease [6, 41, 42]. Relative risk in the meta-analysis was 0.67 (0.46–0.96) for the highest versus lowest category [6], which was comparable, slightly greater than our results for men (hazard ratio 0.82, 95% confidence interval 0.75–0.90) and women (0.75, 0.68–0.84). Several mechanisms by which green tea may reduce risk of cardiovascular disease have been proposed. Polyphenols in green tea are known to exert antioxidant effects on the cardiovascular system [43]. Within the tea family, green tea has the highest concentration of (–) epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) [44], which has been shown to regulate blood pressure, body fat [45], lipids [46], and improve glycemic control [47]. In addition, caffeine in green tea may help maintain blood vessel homeostasis [48, 49]. Collectively or individually, these tea components may modulate risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, thereby leading to decreased mortality risk.

Some compounds found in green tea, possibly act as a bronchodilator and improve pulmonary function, partially explaining the lower risk of death from respiratory disease [50]. However, the concentration of caffeine in green tea is relatively low.

Overall cancer risk is “aggregate” of the spectrum of risks conveyed by site-specific cancers. We sought to assess the impact of green tea on total cancer mortality, rather than investigate individual associations for specific cancer sites. Among women but not men, low to moderate green tea consumption was associated with lower risk of total cancer mortality: hazard ratio 0.89 (95% CI 0.83–0.96) for the 1–2 cups/day category and 0.91 (0.85–0.98) for the 3–4 cups/day category. The reason for an inverse association between green tea consumption and risk of total cancer mortality is not clear. The observed decreased risk may be due to the active ingredient of camellia sinesis, which contains polyphenol. Polyphenol as a compound may inhibit cell proliferation and promote antioxidant activity [51, 52]. EGCG mixed with other catechins may initiate apoptosis, self-destruction of tumor cells without harming healthy tissue [11]. The observed reduced risk with cancer mortality may relate to lifestyle, socioeconomic factors or other residual confounding which could vary by amount of consumption even though most Japanese consume green tea [4]. Green tea consumption was likely not driven by health concerns [4]. Interestingly, reduced cancer mortality risk was observed only in women but not in men. This male–female difference, a weak inverse association between green tea and gastric cancer was reported in a pooled analysis of six Japanese cohort studies reported by the Japanese Cancer Prevention Group [53, 54]. Two recent studies conducted in China found conflicting evidence; one found no association between green tea and total cancer mortality [41], while another among men showed a reduced risk of death from cancer [42]. Numerous case–control and cohort studies have examined the association between green tea consumption and risk of specific cancer sites, including breast, colorectal, esophageal, gastric, liver, lung, pancreatic and prostate cancer [12,13,14,15,16,17,18, 55,56,57]. Some studies have found a higher risk of esophageal cancer in participants consuming hot tea [58]. However, the findings have been mixed and inconclusive, reflecting difficulties and complexities in evaluating the effect of green tea consumption on cancer risk in humans.

Few studies have examined the association between green tea and accidents and injuries. While the confidence intervals in our study include the null, the point estimates are similar to results of other outcomes. These findings may be due to mental or psychological factors as drinking green tea may have a calming effect while simultaneously improving alertness [59]. The possibility of residual confounding unadjusted for in this analysis cannot be excluded. More research investigating different aspects of green tea consumption, psycho-social factors and death due to accidents and injuries could provide fresh insights for public health prevention strategies.

The primary strength of this study is the large sample size and nature of the individual Japanese prospective cohorts, making it representative of the whole country. This pooled analysis also has some limitations. Firstly, misclassification could have occurred as green tea consumption was assessed only once at baseline and habits may change over the course of time. Secondly, beyond the quantity consumed, the analysis does not reflect the green tea content or preparation in more detail. Brewing method and steeping duration could affect the bioavailability of polyphenols [60] and tea drinking temperature could increase the risk of esophageal cancer [58]. Thirdly, we did not have information on the chemical make-up of the beverage, which may independently affect the risk of mortality [19]. Lastly, we acknowledge a further break down of mortality for example stroke and cancer type could have been informative, however the focus of this project was on all cause and major cause groupings.

In conclusion, our pooled analysis of Japanese cohort studies suggests that higher consumption of green tea is associated with lower risk for all-cause mortality in Japanese men and women, especially for heart and cerebrovascular disease.

Abbreviations

- JPHC-I:

-

The Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study, Cohort I

- JPHC-II:

-

The Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study, Cohort II

- JACC:

-

The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study

- MIYAGI:

-

The Miyagi Cohort Study

- OHSAKI:

-

The Ohsaki National Health Insurance Cohort Study

- 3-pref MIYAGI:

-

The Three Prefecture Study—Miyagi portion

- 3-pref AICHI:

-

The Three Prefecture Study—Aichi portion

- 3-pref OSAKA:

-

The Three Prefecture Study—Osaka portion

References

Graham HN. Green tea composition, consumption, and polyphenol chemistry. Prev Med. 1992;21(3):334–50.

Boehm K, Borrelli F, Ernst E, et al. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) for the prevention of cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD005004. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005004.pub2.

Iso H, Date C, Wakai K, Fukui M, Tamakoshi A, Group JS. The relationship between green tea and total caffeine intake and risk for self-reported type 2 diabetes among Japanese adults. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):554–62.

Kuriyama S, Shimazu T, Ohmori K, et al. Green tea consumption and mortality due to cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all causes in Japan: the Ohsaki study. JAMA. 2006;296(10):1255–65. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.10.1255.

Suzuki E, Yorifuji T, Takao S, et al. Green tea consumption and mortality among Japanese elderly people: the prospective Shizuoka elderly cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(10):732–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.06.003.

Tang J, Zheng JS, Fang L, Jin Y, Cai W, Li D. Tea consumption and mortality of all cancers, CVD and all causes: a meta-analysis of eighteen prospective cohort studies. Br J Nutr. 2015;114(5):673–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114515002329.

Zhang C, Qin YY, Wei X, Yu FF, Zhou YH, He J. Tea consumption and risk of cardiovascular outcomes and total mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30(2):103–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9960-x.

Arab L, Khan F, Lam H. Tea consumption and cardiovascular disease risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(6 Suppl):1651S–9S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.059345.

Larsson SC. Coffee, tea, and cocoa and risk of stroke. Stroke. 2014;45(1):309–14. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003131.

Johnson R, Bryant S, Huntley AL. Green tea and green tea catechin extracts: an overview of the clinical evidence. Maturitas. 2012;73(4):280–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.08.008.

Eisenstein M. Tea’s value as a cancer therapy is steeped in uncertainty. Nature. 2019;566(7742):S6.

Gao YT, McLaughlin JK, Blot WJ, Ji BT, Dai Q, Fraumeni JF Jr. Reduced risk of esophageal cancer associated with green tea consumption. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86(11):855–8.

Zhong L, Goldberg MS, Gao YT, Hanley JA, Parent ME, Jin F. A population-based case-control study of lung cancer and green tea consumption among women living in Shanghai, China. Epidemiology. 2001;12(6):695–700.

Ishikawa A, Kuriyama S, Tsubono Y, et al. Smoking, alcohol drinking, green tea consumption and the risk of esophageal cancer in Japanese men. J Epidemiol Jpn Epidemiol Assoc. 2006;16(5):185–92.

Wang JM, Xu B, Rao JY, Shen HB, Xue HC, Jiang QW. Diet habits, alcohol drinking, tobacco smoking, green tea drinking, and the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in the Chinese population. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19(2):171–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0b013e32800ff77a.

Wang M, Guo C, Li M. A case-control study on the dietary risk factors of upper digestive tract cancer. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 1999;20(2):95–7.

Inoue M, Tajima K, Hirose K, et al. Tea and coffee consumption and the risk of digestive tract cancers: data from a comparative case-referent study in Japan. Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9(2):209–16.

Mu LN, Zhou XF, Ding BG, et al. A case-control study on drinking green tea and decreasing risk of cancers in the alimentary canal among cigarette smokers and alcohol drinkers. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2003;24(3):192–5.

Saito E, Inoue M, Sawada N, et al. Association of green tea consumption with mortality due to all causes and major causes of death in a Japanese population: the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study (JPHC Study). Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(7):512–518e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.007.

Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Shimazu T, et al. Evidence-based cancer prevention recommendations for Japanese. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48(6):576–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyy048.

Tsugane S, Sawada N. The JPHC study: design and some findings on the typical Japanese diet. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44(9):777–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyu096.

Tamakoshi A, Yoshimura T, Inaba Y, et al. Profile of the JACC study. J Epidemiol Jpn Epidemiol Assoc. 2005;15(Suppl 1):S4–8.

Tsuji I, Nishino Y, Tsubono Y, et al. Follow-up and mortality profiles in the Miyagi Cohort Study. J Epidemiol Jpn Epidemiol Assoc. 2004;14(Suppl 1):S2–6.

Tsuji I, Takahashi K, Nishino Y, et al. Impact of walking upon medical care expenditure in Japan: the Ohsaki Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(5):809–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyg189.

Sado J, Kitamura T, Kitamura Y, et al. Rationale, design, and profile of the Three-Prefecture Cohort in Japan: a 15-year follow-up. J Epidemiol Jpn Epidemiol Assoc. 2017;27(4):193–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.je.2016.05.003.

Tsubono Y, Nishino Y, Komatsu S, et al. Green tea and the risk of gastric cancer in Japan. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(9):632–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200103013440903.

Tsubono Y, Kobayashi M, Sasaki S, Tsugane S, JPHC. Validity and reproducibility of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire used in the baseline survey of the JPHC Study Cohort I. J Epidemiol Jpn Epidemiol Assoc. 2003;13(1 Suppl):S125–33. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.13.1sup_125.

Inoue M, Kurahashi N, Iwasaki M, et al. Effect of coffee and green tea consumption on the risk of liver cancer: cohort analysis by hepatitis virus infection status. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1746–53. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0923.

Ogawa K, Tsubono Y, Nishino Y, et al. Validation of a food-frequency questionnaire for cohort studies in rural Japan. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6(2):147–57. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2002411.

Kashino I, Akter S, Mizoue T, et al. Coffee drinking and colorectal cancer and its subsites: a pooled analysis of 8 cohort studies in Japan. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(2):307–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31320.

World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th Revision. Geneva: WHO; 1992.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Mineharu Y, Koizumi A, Wada Y, et al. Coffee, green tea, black tea and oolong tea consumption and risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease in Japanese men and women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(3):230–40. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.097311.

Saito E, Inoue M, Tsugane S, et al. Smoking cessation and subsequent risk of cancer: a pooled analysis of eight population-based cohort studies in Japan. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;51:98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2017.10.013.

Iwasaki M. Commentary: factors associated with non-participation in cohort studies emphasize the need to generalize the results with care. J Epidemiol Jpn Epidemiol Assoc. 2015;25(2):89–90. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20140269.

Iwasaki M, Yamamoto S, Otani T, et al. Generalizability of relative risk estimates from a well-defined population to a general population. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(4):253–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-006-0004-z.

Sugiyama K, Kuriyama S, Akhter M, et al. Coffee consumption and mortality due to all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer in Japanese women. J Nutr. 2010;140(5):1007–13. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.109.109314.

Tamakoshi A, Lin Y, Kawado M, et al. Effect of coffee consumption on all-cause and total cancer mortality: findings from the JACC study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(4):285–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9548-7.

Cui R, Iso H, Eshak ES, Maruyama K, Tamakoshi A, Group JS. Water intake from foods and beverages and risk of mortality from CVD: the Japan Collaborative Cohort (JACC) Study. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(16):3011–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018001386.

Tani Y, Asakura K, Sasaki S, et al. The influence of season and air temperature on water intake by food groups in a sample of free-living Japanese adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(8):907–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.290.

Zhao LG, Li HL, Sun JW, et al. Green tea consumption and cause-specific mortality: results from two prospective cohort studies in China. J Epidemiol Jpn Epidemiol Assoc. 2017;27(1):36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.je.2016.08.004.

Liu J, Liu S, Zhou H, et al. Association of green tea consumption with mortality from all-cause, cardiovascular disease and cancer in a Chinese cohort of 165,000 adult men. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(9):853–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0173-3.

Wang H, Provan G, Helliwell K. The functional benefits of flavonoids: the case of tea. In: Johnson I, Williamson G, editors. Phytochemical funtional foods. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing; 2003.

Schneider C, Segre T. Green tea: potential health benefits. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(7):591–4.

Nagao T, Hase T, Tokimitsu I. A green tea extract high in catechins reduces body fat and cardiovascular risks in humans. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(6):1473–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.176.

Zheng XX, Xu YL, Li SH, Liu XX, Hui R, Huang XH. Green tea intake lowers fasting serum total and LDL cholesterol in adults: a meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(2):601–10. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.010926.

Zheng XX, Xu YL, Li SH, Hui R, Wu YJ, Huang XH. Effects of green tea catechins with or without caffeine on glycemic control in adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(4):750–62. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.032573.

Zucchi R, Ronca-Testoni S. The sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ channel/ryanodine receptor: modulation by endogenous effectors, drugs and disease states. Pharmacol Rev. 1997;49(1):1–51.

Spyridopoulos I, Fichtlscherer S, Popp R, et al. Caffeine enhances endothelial repair by an AMPK-dependent mechanism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(11):1967–74. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.174060.

Welsh EJ, Bara A, Barley E, Cates CJ. Caffeine for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD001112. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001112.pub2.

Yang CS, Lee MJ, Chen L, Yang GY. Polyphenols as inhibitors of carcinogenesis. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105(Suppl 4):971–6.

Yang CS, Wang X, Lu G, Picinich SC. Cancer prevention by tea: animal studies, molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(6):429–39. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2641.

Japanese Cancer Prevention Group. Green tea and stomach cancer risk [in Japanese]. National Cancer Center. https://epi.ncc.go.jp/can_prev/evaluation/2947.html. Accessed 12 Nov 2018.

Inoue M, Sasazuki S, Wakai K, et al. Green tea consumption and gastric cancer in Japanese: a pooled analysis of six cohort studies. Gut. 2009;58(10):1323–32. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2008.166710.

Suzuki Y, Tsubono Y, Nakaya N, Suzuki Y, Koizumi Y, Tsuji I. Green tea and the risk of breast cancer: pooled analysis of two prospective studies in Japan. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(7):1361–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601652.

Inoue M, Robien K, Wang R, Van Den Berg DJ, Koh WP, Yu MC. Green tea intake, MTHFR/TYMS genotype and breast cancer risk: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(10):1967–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgn177.

Lin Y, Kikuchi S, Tamakoshi A, et al. Green tea consumption and the risk of pancreatic cancer in Japanese adults. Pancreas. 2008;37(1):25–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0b013e318160a5e2.

Islami F, Poustchi H, Pourshams A, et al. A prospective study of tea drinking temperature and risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32220.

Dietz C, Dekker M. Effect of green tea phytochemicals on mood and cognition. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23(19):2876–905. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612823666170105151800.

Wang Y, Ho CT. Polyphenolic chemistry of tea and coffee: a century of progress. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57(18):8109–14. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf804025c.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Cancer Center Research and Development Funds (30-A-15, 27-A-4, 24-A-3) and the Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants for the Third Term Comprehensive Control Research for Cancer (H21-3jigan-ippan-003, H18-3jigan-ippan-001, H16-3jigan-010). The funders had no role in the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation or manuscript drafting, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

MI designed the research. SKA performed the analyses, prepared the tables and drafted the paper. MI, ES, NS, ST, YL, and AS supported analyses, discussions and finalizing of the paper. HI, YL, AT, JS, YK, YS, IT, CN, TS, TM, KM, MN, and KT provided valuable feedback regarding interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

For the Research Group for the Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan: Research group members are listed at the following site (as of August 2018): http://epi.ncc.go.jp/en/can_prev/796/7955.html.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abe, S.K., Saito, E., Sawada, N. et al. Green tea consumption and mortality in Japanese men and women: a pooled analysis of eight population-based cohort studies in Japan. Eur J Epidemiol 34, 917–926 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00545-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00545-y