Abstract

Recent studies suggest that testing on prior material enhances subsequent learning of new material. Although such forward testing effect has received extensive empirical support, it is not yet clear how testing facilitates subsequent learning. One possible explanation suggests that interim testing informs learners about the format of an upcoming test and consequently allows them to adopt study strategies in accordance with the anticipated test format. Three experiments investigated whether the beneficial effects of testing are due to learners’ expectation with the test format or due to testing experience itself in inductive learning by varying when and how learners were informed about the format of an upcoming test. The results showed that informing learners about the test format via an interim test, but not a pretest, enhanced subsequent learning (experiment 1), and it was effective only when combined with actual test-taking experience (experiment 2). Testing appeared to enhance subsequent learning of new material when learners had an opportunity to evaluate their mastery over previously studied information. Experiment 3 further showed that these beneficial effects of testing were yielded even in the absence of feedback. Taken together, the findings suggest that mere exposure to the test format, not combined with actual testing, is not sufficient to enhance subsequent learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Imagine that you are a teacher in the classroom full of students preparing for their final exam. As you inform the students that they can ask you any question about their upcoming exam, you are presented with one of the most common questions that students pose to their teachers: “What is the format of the final test?” To prepare for an exam, students often wish to know the format of the test and believe that they can be better prepared if they study in accordance with the expected test format. For example, students might adopt a detail-oriented memorization strategy when expecting a multiple-choice test, and a more conceptual learning strategy when expecting an essay test. Indeed, several studies have shown that students change their study strategies (Finley and Benjamin 2012; Middlebrooks et al. 2017) and adjust their study time (Thiede 1996) according to the anticipated test format. Teachers also often inform their students about the format of an upcoming test, and hope that this information will help them optimize their learning. However, it is unclear whether informing students about the test format is sufficient to enhance learning. Students may adopt strategies that are perceived to be effective to prepare for a test with a specific format, but such strategies may actually be ineffective. In order to use a strategy that is actually effective to the demands of an anticipated test, students may need to test themselves with that specific format via a practice test. If actual test experience is more critical to the enhancement of subsequent learning than mere awareness of the test format, informing test format without actual testing may not be an effective strategy to enhance subsequent learning. Thus, the current study aimed to examine whether test format expectation in the absence of actual test experience can promote learning. Specifically, we used the forward testing effect paradigm and examined the effects of test format expectation and test experience itself in inductive learning.

Forward Testing Effect

Studies over the last 100 years have demonstrated a strong and positive effect of testing on learning (for reviews, see Pastötter and Bäuml 2014; Roediger III and Butler 2011; Roediger III and Karpicke 2006b; Yang et al. 2018). Testing has been known to enhance learning in two ways (Pastötter and Bäuml 2014). On one hand, taking a test improves retention of the studied material compared to restudying—the backward testing effect. Retrieval of previously studied information tends to increase long-term retention of that information more than repeated study (Roediger III and Karpicke 2006a). On the other hand, taking a test over prior material also facilitates subsequent learning of new material—the forward testing effect. Asking learners to recall previously studied information before they study new information enhances learning of the newly studied information more than repeated study even when learners had an identical learning experience with the new information (Pastötter and Bäuml 2014; Wissman et al. 2011).

Recently, the forward testing effect has been extensively researched using various terminologies: forward testing effect (Lee and Ahn 2018; Yang and Shanks 2018), interim-test effect (Wissman et al. 2011), and test-potentiated new learning (Arnold and McDermott 2013; Chan et al. 2018a; Wissman and Rawson 2018). In a standard forward testing effect paradigm, participants study multiple lists of materials. Depending on the condition, participants are tested (test condition) or not tested (control condition) after studying each preceding list. Most importantly, immediately after studying the final list, both groups of participants are tested on that final list. On this final criterial test, if the test group exhibits better memory performance than the control group, then this can be interpreted as the forward testing effect. For example, Wissman et al. (2011) demonstrated a forward testing effect in recall memory of expository texts. In the test condition, participants were asked to recall each preceding text before studying the subsequent new text, while the participants in the control condition were asked to recall the final text only. The results showed that the memory performance of the final text was always better when participants were given interim tests. Many prior studies have demonstrated the forward testing effect on retention learning using various learning materials, including words (Nunes and Weinstein 2012; Pastötter et al. 2011; Szpunar et al. 2008), face and name pairs (Davis and Chan 2015; Weinstein et al. 2011), trivia facts (Kornell 2014), texts (Wissman et al. 2011), line drawings (Pastötter et al. 2013), contents of videos (Jing et al. 2016; Szpunar et al. 2013), and spatial information (Bufe and Aslan 2018). Also, previous studies suggest that such benefit of testing is not restricted to the healthy young populations. The forward testing effect has been demonstrated with various populations, from elementary school students (Aslan and Bäuml 2016) to older populations (Pastötter and Bäuml 2019), among the people with severe traumatic brain injury (Pastötter et al. 2013), and regardless of individual differences in working memory capacity (Pastötter and Frings 2019), showing the general and robust forward effect of testing. These studies have shown benefits of interim memory tests on subsequent learning, as demonstrated in better memory performance of new material.

In addition to beneficial effect of testing on retention and memory performance, several studies demonstrated the forward testing effect on inductive learning performance (Lee and Ahn 2018; Lee and Ha 2019; Yang and Shanks 2018). For example, Lee and Ahn (2018) had participants study the painting styles of various artists across two separate sections and examined the effect of interim testing of the first section on the subsequent learning of the second section. After studying the paintings of the first section, participants either were tested or restudied the studied artists of the first section. Subsequently, all the participants studied the paintings of the second section under the same study condition, and were given a final transfer test on the second section. The final test required people to classify new paintings created by the studied artists. Thus, to successfully perform the task, the participants had to abstract general patterns of the paintings and apply what they had learned to novel paintings. Across the four experiments, participants who were tested on the first section always performed better on the final test of the second section than those who were not tested, indicating that interim testing facilitated inductive learning of subsequent new material. Similar findings were reported by Lee and Ha’s (2019) and Yang and Shanks’ (2018) studies using a painting style learning task.

Although many studies have established that the forward testing effect is a robust phenomenon in both retention and inductive learning, it is not yet clear how testing promotes subsequent learning. Several theories have been proposed to account for the forward testing effect (for reviews, see Chan et al. 2018b; Pastötter and Bäuml 2014; Yang et al. 2018; see also Kornell and Vaughn 2016). Here, we summarize largely three different explanations. First, some researchers have suggested that testing potentiates future learning by reducing proactive interference among study sessions (Bäuml and Kliegl 2013; Pastötter et al. 2011; Szpunar et al. 2008). Inducing a change in the context via testing allows learners to detach from the previously studied material, and focus more on the subsequent encoding and/or retrieval of new information. Moreover, testing is known to reduce mind wandering; this in turn may increase learners’ attentional resources in encoding of new information (Jing et al. 2016; Szpunar et al. 2013).

Second, some researchers have suggested that testing facilitated subsequent new learning by increasing learners’ test expectancy. Test expectancy can have two different meanings. One is general test expectancy that there will be a test soon (i.e., “I will be tested in the near future.”), and the other is expectation on what the test will be like (i.e., “I know the format of the test.”). To differentiate between these two, we refer to the former as test expectancy, and the latter as test format expectation throughout the paper. Previous research on test expectancy has focused on the first sense, the role of test expectancy in the forward testing effect. Interim testing increases learners’ expectancy about an upcoming test (i.e., “I will be tested again in the near future.”), and this in turn encourages them to invest greater effort in subsequent learning (Weinstein et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2017). For example, Weinstein et al. (2014) used a multiple-list learning task to examine the effect of test expectancy on subsequent learning. As a between-subject factor, the participants were required to either recall each word list or complete a simple math task once they finished studying each list. Additionally, participants were given or not given warning of a subsequent test. The participants who were warned about the upcoming test were presented with an alarm before they studied the last list that they were going to be tested on it, whereas those who were not warned studied the last list consecutively without an alarm. The final results showed that the performance differed according to the level of participants’ test expectancy. Participants who were tested consistently showed a higher level of test expectancy than those who were not tested; further, participants who were not tested showed a gradually decreased level of test expectancy. On the other hand, the group that was informed about the test but not tested demonstrated recovery of their level of test expectancy after they were alarmed about an upcoming test. They recalled more words from the final list on the cumulative test than those who were neither tested nor informed about the test. Similarly, Yang and his colleagues (Yang et al. 2019) reported a positive correlation between test expectancy and performance, indicating that high levels of test expectancy led people to study hard in subsequent study, thereby resulting in better learning performance. In sum, taking a test appears to increase learners’ expectancy that they will soon be tested again, and in turn motivate them to study harder in subsequent learning (Agarwal and Roediger III 2011).

Last but not least, the third explanation is that testing potentiates subsequent learning because it allows learners to optimize their study strategy to a more efficient one. Many studies have suggested that the forward testing effect occurs as interim testing encourages learners to evaluate and accommodate the learning strategy to use when they encounter new learning material (Chan et al. 2018a, b; Cho et al. 2017; Gordon and Thomas 2017; Lee and Ahn 2018; Wissman et al. 2011). For example, Cho et al. (2017) have suggested that testing causes learners to shift to a more efficient encoding strategy. Similarly, Lee and Ahn (2018) proposed that interim testing prepares students to learn better as it helps them evaluate the effectiveness of their current learning strategies and affects subsequent learning strategies (see also Lee and Ha 2019). In addition, Chan and his colleagues (Chan et al. 2018a) provided direct evidence on this strategy change account. They had participants study four lists of words consecutively and examined how testing affected the semantic organization of the contents of the lists that they were required to recall. The test group was tested on each list, whereas the restudy group studied the items twice. The results showed enhanced semantic organization of the studied materials among the test group, compared to the restudy control group, suggesting that testing causes learners to use superior encoding strategies.

What Is Critical? Test Format Expectation vs. Test Experience

Numerous studies have demonstrated the forward testing effect, and several explanations have been proposed to account for its underlying mechanisms. However, one critical limitation of the prior studies is that a majority of them used the same or similar test formats for both interim and final tests. Such procedure suggests a possibility that the forward testing effect might be merely a result of knowing the test format in advance, namely, test format expectation. In a typical forward testing effect paradigm, participants in the test condition are tested multiple times, and thus are exposed to the test format before they take the final test. In contrast, participants in the control condition (e.g., restudy, math) take only one single test (i.e., final test); thus, they are not exposed to the test format in advance. This procedure, however, makes it difficult to understand the mechanism by which interim testing facilitates subsequent learning. The facilitative effect of testing may be attributable to the fact that the participants who are given an interim test can anticipate the type of test they will receive later; this in turn may allow them to accordingly optimize their study strategies. Indeed, previous studies provide evidence that students change their learning strategies according to their test format expectation. For example, Finley and Benjamin (2012) had participants anticipate either a cued-recall or free-recall test. The format of the test that the participants were administered was either consistent or inconsistent with their expectations. The results revealed that the final test performance was worse when the expected and actual test formats were inconsistent rather than consistent. Moreover, analysis of the participants’ encoding strategies revealed that they tended to study according to the expected format. Similarly, in the forward testing effect paradigm, interim tests may inform learners about the kind of test that they will be receiving and cause them to accordingly adjust their encoding strategies, which in turn may enhance subsequent encoding of new information.

In fact, most of the previous studies on the forward testing effect used the same free-recall (Nunes and Weinstein 2012; Pastötter et al. 2011; Szpunar et al. 2008; Wissman et al. 2011), cued-recall (Davis and Chan 2015; Weinstein et al. 2011), or short-response test formats (Szpunar et al. 2013) for both the interim and final tests. Thus, only the participants who received an interim test were able to study in accordance with the anticipated test format. Furthermore, even if the test formats were to differ across the two test sessions, participants can still anticipate the format of the test they are finally going to receive. For example, Lee and Ahn (2018) and Lee and Ha (2019) used different test formats for the interim and final tests; nevertheless, the benefits of interim testing were evident. Specifically, they used a cued-recall test for the interim test and a multiple-choice test for the final test (experiments 3 and 4 in Lee and Ahn 2018; experiments 1–3 in Lee and Ha 2019). Although the required cognitive processes were not identical between the two tests (i.e., recall vs. recognition), the questions used in the two tests were identical (i.e., who do you think created the following painting?). In both cases, participants were required to identify the painting style of a given painting and provide the correct name of the artist. Thus, the participants in the test condition were more likely to have expectation about the format of the upcoming final test. Consequently, they may have used more effective study strategies in the following study section.

Previous studies that examined the effect of test expectancy in the forward testing effect has focused on general test expectancy (e.g., Weinstein et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2017), but did not directly examine the effect of test format expectation. To the best of our knowledge, there was only one recent study that verified the occurrence of forward testing effect when the formats of interim and final tests were clearly different (experiments 2 and 3 in Yang et al. 2019). In their experiment 2, Yang et al. (2019) showed that the test group outperformed the restudy group even when material types (paintings, texts, and face-profession pairs) and test formats (recognition, fill-in-blank, and cued-recall test) were frequently switched, indicating the transfer of forward testing effect. However, Yang et al. still cannot determine whether the forward testing effect is due to test format expectation or actual test experience itself because only the test group was exposed to diverse test formats. Unlike the test group, the control restudy group was never informed about any of the test format before the final test. Even though the material types and test formats were different between the interim and final tests, if the test group’s study strategies that were optimized for the interim test format were also effective for the final test format, the test group would show better performance than the restudy group. In order to examine the role of test format expectation in the forward testing effect, we need to examine whether the forward testing effect occurs even when the test format expectation is controlled between the test and control groups.

If the benefit of testing is merely attributable to the test format expectation, one may argue that learning can be enhanced by informing students about the test format in advance of studying, not necessarily having them take an interim test. In contrast, the test format knowledge alone may not be as beneficial as actual test experience. Numerous research on backward testing effects demonstrated the importance of actual test experience by comparing retention performance between tested and not-tested information using within-subject designs (e.g., Little et al. 2012; McDermott et al. 2014; Rowland et al. 2014). Because participants are both tested on some information and not tested on other information, they are informed of what the final test format will be like. Nonetheless, the tested information is remembered better than the non-tested information, suggesting that test format knowledge is not as beneficial as actual test experience. Therefore, the current study aimed to explore the role of actual test experience by separating the effect of test format expectation in the forward testing effect paradigm. If knowing about the test format is critical to the enhancement of subsequent learning, the participants who were informed about the test format from their prior learning, even if they were not actually tested, should perform as well as those who were tested in the middle of the study. In other words, knowledge about the test format and actual test experience will similarly facilitate the subsequent learning of new material. In contrast, if actual test experience is critical to learning, those who took an actual test on previously studied material should demonstrate better performance in subsequent learning than those who did not take an actual test.

The Present Study

A primary goal of the present study was to investigate whether the forward testing effect is due to learners’ expectation about the test format or actual test experience itself. To achieve this goal, the present study manipulated when (i.e., timing) and how (i.e., method) participants were informed about the test format and examined how their experience of the test format influences subsequent learning of new material. In addition, we controlled the general test expectancy by notifying all participants, at the beginning of the study, that they would be subjected to a final test at a later time. To investigate the forward testing effect in inductive learning, the current study chose a painting style learning task, which has been widely used in research on inductive learning (e.g., Kang and Pashler 2012; Kornell and Bjork 2008; Kornell et al. 2010; Yan et al. 2017). Several studies have examined the forward testing effect using this task (Lee and Ahn 2018; Lee and Ha 2019; Yang and Shanks 2018).

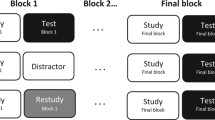

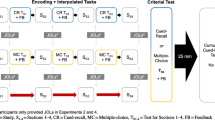

Figure 1 illustrates the procedures used in experiments 1–3. Across all the experiments, participants studied the painting styles of 12 different artists. The study material was presented across two sections: sections A and B. Each section consisted of the paintings of six different artists. Based on the condition that they were assigned to, the participants engaged in a different activity on section A before they began studying section B. Subsequently, all the participants studied the paintings of section B under the same condition. Once they had finished studying section B, all the participants did a short distractor task (i.e., simple math task), and then were given a final transfer test on both sections A and B. In the final test, the participants were required to correctly identify the artist of a new set of paintings created by the artists that they had previously learned about.

In experiment 1, the effect of when (i.e., timing) learners were informed about the test format was examined by administering a test before or after the participants studied section A. Specifically, we used a pre-test and interim-test condition as well as an additional control condition, namely, the restudy condition. The pre-test group was given a test on section A at the beginning of the experiment. In this manner, they were informed about the test format before any learning had occurred. The interim-test group was given a test after they had finished studying section A. In this manner, they were informed about the test format after initial learning of section A. In experiment 2, we examined the effect of different methods of informing learners about the test format. All the participants were exposed to the test format after initial learning of section A, but in two different ways, via an interim test or restudy. On completion of section A, only those in the interim-test condition did an actual test-taking and the restudy group simply restudied the material as in an already solved test. Finally, we conducted experiment 3 to further examine whether actual test experience is more effective in enhancing subsequent learning than restudying even in the absence of feedback.

Experiment 1

The goal of experiment 1 was to investigate the effect of the timing of informing learners about the test format. To achieve our goal, we used pretesting and interim testing effect paradigms. We asked three groups of participants (pre-test, interim-test, restudy) to engage in a different activity when they learned about the painting styles of the first section. Participants in the pre-test condition were asked to take a pretest before they began studying the first section, section A, and the format of the pretest was identical to that of the final transfer test. Thus, the pre-test group was exposed to the format of the final test before any learning had occurred. On the other hand, participants in the interim-test condition studied the paintings of section A first and then were tested on it. Thus, they were exposed to the test format via testing after initial learning had occurred (i.e., between sections A and B). Additionally, we included a control restudy condition. The participants who were assigned to this condition were not tested on section A; instead, they studied the same set of paintings twice. Hence, the restudy group was not exposed to the final test format.

If knowing about the test format is critical to the forward testing effect, the pre-test group should show better performance than any other groups for section A, and perform as well as the interim-test group for section B, because they were informed about the test format from the beginning. The pre-test group could adjust their study strategies during pretesting in accordance with the test format and use those adjusted strategies while studying subsequent sections (i.e., both sections A and B). In contrast, the interim-test group was informed about the test format and could adjust their study strategies only after studying section A; thus, they could apply those adjusted strategies only for studying section B. In addition, according to test expectancy theory (e.g., Weinstein et al. 2014), the pre-test group should demonstrate improved attention and invest greater effort in encoding information in both sections as they expect an imminent test. On the other hand, if actual test experience on the previously studied material plays a more important role, the interim-test group would outperform the other groups on the final test.

Moreover, the current research design allowed us to examine the effect of taking a pretest in inductive learning. Earlier studies suggest that learners can benefit from taking a test before they start learning—the pretesting effect (Richland et al. 2009). Taking a pretest before studying tends to improve learning to a greater extent than studying it twice. The pretesting effect has been replicated using a wide range of educational materials, including word pairs (Grimaldi and Karpicke 2012; Hays et al. 2013; Potts and Shanks 2014), face-age pairs (McGillivary and Castel 2010), trivia facts (Kornell 2014; Kornell et al. 2009), mathematical knowledge (Kapur and Bielaczyc 2012), and complex texts (Richland et al. 2009). However, it has not been examined whether taking a pretest is beneficial to inductive learning. Although testing is known as an effective learning strategy to use in inductive learning (Jacoby et al. 2010; Lee and Ahn 2018; Lee and Ha 2019; Yang and Shanks 2018), it is not clear whether pretesting also facilitates inductive learning. If pretesting and interim testing have similar facilitative effects on learning, tests that are administered at different times will similarly enhance inductive learning of subsequent material.

Method

Participants

Sample size was calculated based on the previous studies which examined the forward testing effect in inductive learning (Lee and Ahn 2018; Lee and Ha 2019). Previous studies observed effect sizes (i.e., Cohen’s ds) of the forward testing effect ranging from 0.59 to 1.31 when using a restudy group as a control condition. We conducted power analyses using G*Power (Faul et al. 2007) and found that about 11–47 participants were required in each group to observe a significant forward testing effect at 0.8 power. Therefore, 20 or more participants were recruited per condition in each experiment. Participants were 61 undergraduates (39 women, 22 men; mean age = 23 years) from a large university in South Korea. All the participants received a voucher equivalent to $5 as compensation. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the three conditions: pre-testF, interim-testF, and restudy conditions. One participant in the interim-testF condition was excluded in the data analysis because the response time on the final test was lower than 1 s, resulting in 20 participants assigned to each condition.

Design

A 3 × 2 mixed design was employed. First, the type of activity performed on section A was manipulated as a between-subject variable. Participants conducted a pretest, interim test, or restudy on the paintings of section A before moving on to study the paintings of section B. These three conditions are henceforth referred to as pre-testF, interim-testF, and restudy conditions (The superscript F indicates the provision of feedback). Feedback was included to equate the exposure to painting-artist pairs between the test and restudy conditions. Second, the section was manipulated as a within-subject variable. Therefore, all the participants studied both section A and section B and were given a final test for both sections.

Materials

The current study employed a painting style learning task that consisted of the paintings of 12 different artists. The paintings were identical to those that were used by Lee and Ahn (2018), which were originally adapted from Kornell and Bjork (2008). The artists were Georges Braque, Henri-Edmond Cross, Judy Hawkins, Philip Juras, Ryan Lewis, Marilyn Mylrea, Bruno Pessani, Ron Schlorff, Georges Seurat, Emma Ciadi, George Wexler, and Yie Mei. All the paintings were colored landscapes, and their sizes were standardized to fit the computer screen. Twelve artists were divided into two sections, six artists to section A and another six artists to section B. Six paintings of each artist were used as the study material and another four paintings of each artist as the final test material. The artist-section pairs between sections A and B were counterbalanced to control for specific item effect.

Procedure

The present research was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the university where this research took place and the informed consent was obtained from all the individuals who participated in this study. The experiment was proceeded individually on a computer in the laboratory. Before the experiment began, participants were instructed about the procedure of the study and informed about the final test. Specifically, all the participants were told that they would learn about the painting styles of various artists and would be tested later by being asked to identify correct artist’s name given a new, unfamiliar painting created by the studied artists.

All the participants first studied the 36 paintings (6 paintings × 6 artists) in section A, but in a different way according to the condition. For both the pre-testF and interim-testF conditions, before either a pretest or interim test was administered, participants were explicitly told that they would be tested in the same format of the final test. In the pre-testF condition, the participants first took a pretest on the paintings of section A before any learning occurred. The format of the pretest was a multiple-choice test, which was identical to the format of the final test that all participants would receive later. Each painting was presented on a computer screen, and the participants were asked to correctly identify the name of the artist from a list of six different names. As soon as they chose an answer, feedback was immediately provided. Specifically, a picture and the name of the artist were simultaneously presented for 1.5 s. After finishing the pretest on section A, the participants studied the paintings of section A. During this phase, a painting and the corresponding artist’s name were presented together for 3 s on the screen. The paintings of different artists were intermixed and presented in a fixed random order. In contradistinction to the pre-testF condition, in the interim-testF and restudy conditions, the participants were first given the study phase of section A. Subsequently, those in the interim-testF condition took an interim test on section A with feedback given for 1.5 s as in the pre-testF condition. The format of the interim test was exactly the same as that of the pretest, but they differed in the timing at which the tests were given. In the restudy condition, the participants did not take any test on section A; instead, they studied the same paintings of section A a second time.

Upon completion of section A, all the participants studied the paintings of another six artists in section B. This time, all the participants studied a total of 36 paintings in the same manner regardless of the conditions. The paintings were presented in the same manner as in the study phase of section A. Subsequently, participants solved simple math problems for about 3 min as a distractor task, and then were given a final transfer test. Participants were presented with the paintings that were created by the studied artists, but were never seen in any of the previous study phases. Thus, the final transfer test could be successfully done only when the participants identified the general and abstract painting styles of each artist. Similar to the pretest and interim tests, the format of the final test was a multiple-choice test. However, feedback was not provided in the final test. Participants were presented with a multiple-choice test that required them to select the name of the artist whom they believed had created the painting from a list of 12 different names. The final test comprised a total of 48 problems (4 new paintings × 12 different artists), and it was a self-paced test. At the end, the participants were debriefed and thanked.

Results

Pretest and Interim Test Performance

Participants in the pre-testF and interim-testF conditions were tested on section A before studying section B. The mean percentage of correct answers was 48.95 (SD = 15.38) in the pre-testF, and 81.05 (SD = 14.03) in the interim-testF condition.

Final Test Performance

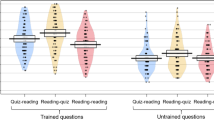

Figure 2 shows the mean percentage of correct answers on the final transfer test of sections A and B across the pre-testF, interim-testF, and restudy conditions. A 3 × 2 mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on the number of correct responses. The type of activity performed on section A (pre-testF vs. interim-testF vs. restudy) was included as a between-subject factor, while the section (A vs. B) was included as a within-subject factor. There was a significant main effect of activity, F(2, 57) = 4.51, p = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.137. The interim-testF group (M = 60.55, SD = 16.71) showed significantly better transfer performance than the pre-testF group (M = 46.80, SD = 17.87), t(38) = 2.51, p = 0.016, d = 0.79, and the restudy group (M = 42.55, SD = 17.81), t(38) = 3.30, p = 0.002, d = 1.04. The mean difference between the pre-testF and restudy group was not significant, t(38) = 0.75, p = 0.456. However, the main effect of section was not significant, F(1, 57) = 0.45, p = 0.506, indicating that overall performance was not different between section A (M = 54.83, SD = 18.55) and section B (M = 51.15, SD = 20.41). Moreover, the interaction effect between activity and section was not significant, F(2, 57) = 1.24, p = 0.297, because the performance patterns across the three conditions were similar between the two sections.

With regard to sections A and B, the interim-testF group appeared to perform better than the other groups. For section A, the interim-testF group (M = 54.30, SD = 15.62) performed numerically better than the pre-testF group (M = 45.90, SD = 18.20), t(38) = 1.57, p = 0.125, and the restudy group (M = 44.55, SD = 19.20), t(38) = 1.77, p = 0.085. However, the superior performance of the interim-testF condition did not reach a significance level. For section B, the participants in the interim-testF condition (M = 62.30, SD = 19.98) performed significantly better than those in the pre-testF condition (M = 47.55, SD = 23.85), t(38) = 2.12, p = 0.041, d = 0.67, and those in the restudy condition (M = 40.95, SD = 25.43), t(38) = 2.95, p = 0.005, d = 0.93. The mean difference between the pre-testF and restudy groups was not significant, t(38) = 0.85, p = 0.403.

Discussion

Regarding the final transfer performance, the interim-testF group, but not the pre-testF group, outperformed the restudy group. Specifically, the interim-testF group performed marginally significantly better than the restudy group for section A, and significantly better than the restudy group for section B, replicating the forward testing effect in inductive learning (Lee and Ahn 2018; Lee and Ha 2019; Yang and Shanks 2018). Both the pre-testF and interim-testF groups were exposed to the test format before they began studying the subsequent section (section B). The only difference between these two groups was the timing of testing. If the test format knowledge was important, the pre-testF group should have demonstrated better performance than the other two groups for section A, and performed as well as the interim-testF group for section B, because they had test format expectation in advance of any learning had occurred. However, this was not the case. The pre-testF group did not differ from the restudy group in any of the sections, and they performed numerically worse for section A and significantly worse for section B than the interim-testF group.

The results show that testing learners before they engaged in learning (i.e., pretest) did not seem to enhance learning even though it informed participants of the test format at the beginning. In contrast, testing after initial learning (i.e., interim test) enhanced subsequent learning of new material. These results suggest that mere knowledge about the test format does not account for the benefits of testing in the forward testing effect, rather it is important for learners to have the opportunity to test their own learning after initial learning has occurred.

It may be surprising that the pretesting effect was not found in the current study given that there were several studies showing the benefits of a pretest over restudying, even when participants’ retrieval attempts during pretesting were unsuccessful (Grimaldi and Karpicke 2012; Kornell et al. 2009; Richland et al. 2009). Two possible explanations can be considered regarding the absence of pretesting effect. One is that the pretest used in the current study may not have been an appropriate means to activate participants’ prior knowledge (Kornell et al. 2009). Another possibility is that participants may have treated the pretest session as a study session. We further discuss these explanations in “General Discussion.”

One limitation of experiment 1 is that we cannot tell whether the observed benefit of interim testing was because of knowing about the test format right before studying subsequent section, or because of an opportunity for learners to test their own learning after initial learning had occurred. That is, the pre-testF and interim-testF groups differed in two aspects: (1) when participants were informed about the test format and (2) whether participants had an opportunity to evaluate their own learning. To address this issue, the following experiment controlled when participants were informed about the test format (i.e., timing) and examined whether test format expectation or test experience itself is critical to the forward testing effect. Because pretesting was not effective in experiment 1, this condition was not included anymore in the following experiments.

Experiment 2

In experiment 2, we examined whether the benefits of interim testing would be observed when controlling for test format expectation in a more rigorous way. All the participants in experiment 2 were informed about the final test format between the two study sessions, sections A and B, either by taking an interim test or by restudying the material using a solved test format. In the interim-test condition, participants took an actual test on section A as in experiment 1. In the restudy condition, participants were given an already solved test with correct answers marked on; thus, they did not have to solve any problems. In this way, the participants of both the interim-test and restudy conditions were exposed to the test format at the same timing; however, they learned about the test format in different ways. If knowing about the test format in the middle of the study is important (between sections A and B), then the restudy group would perform as well as the interim-test group, because they also had an opportunity to adjust their study strategies in accordance with the anticipated test format before moving on to study the second section. In contrast, if actual test experience is important, the interim-test group would show better performance than the restudy group.

Method

Participants

Participants were 40 undergraduates (20 women, 20 men; Mean age = 22 years) from a large university in South Korea. All the participants received a voucher equivalent to $5. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the two conditions: interim-testF and restudyT conditions (20 participants in each condition).

Design, Materials, and Procedure

As Fig. 1 illustrated, the overall procedure of experiment 2 was similar to that of experiment 1. In experiment 2, after studying the first section, section A, participants were given a different interim activity, either an interim test or restudy, prior to the second section, section B. We henceforth refer to these two conditions as interim-testF to indicate the presence of feedback, and restudyT to indicate the provision of the test format information. For interim activity, participants were explicitly informed that they would be tested or restudy the paintings in the same format of the final test that they would receive later. In the interim-testF condition, as in experiment 1, participants took a multiple-choice test on section A. For each problem, feedback was provided for 1.5 s. In the restudyT condition, participants studied section A again, but in a different manner from experiment 1. The paintings were presented as an already correctly solved multiple-choice test. Each test problem was presented for 3 s, as in the interim-testF condition, but with a red circle marked on the correct answer among the six options, as if it is an already completed test. After the completion of the intervening activity on section A, all the materials and procedures were identical to those of experiment 1.

Results

Interim Test Performance

Only the participants in the interim-testF condition were tested on section A and the mean percentage of correct answers was 85.90 (SD = 9.10).

Final Test Performance

Figure 3 shows the mean percentage of correct answers on the transfer test of sections A and B in the interim-testF and restudyT conditions. A 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA was conducted on the number of correct responses. Interim activity (interim test vs. restudy) was included as a between-subject factor, while section (A vs. B) was included as a within-subject factor. There was a significant main effect of interim activity, F(1, 38) = 12.97, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.254. The interim-testF group (M = 61.55, SD = 14.61) showed significantly better transfer performance than the restudyT group (M = 44.30, SD = 15.77), t(38) = 3.59, p = 0.001, d = 1.16. However, there was neither a significant main effect of section, F(1, 38) = 1.66, p = 0.21, nor interaction effect between interim activity and section, F(1, 38) = 0.25, p = 0.62.

The same patterns of results were observed between the sections A and B. For section A, the interim-testF group (M = 62.75, SD = 16.97) showed significantly better performance than the restudyT group (M = 46.90, SD = 16.91), t(38) = 2.96, p = 0.005, d = 0.96, indicating that there was a backward testing effect. Likewise, for section B, the interim-testF group (M = 60.50, SD = 17.44) outperformed the restudyT group (M = 41.80, SD = 19.16), t(38) = 3.23, p = 0.003, d = 1.05, indicating a forward testing effect.

Discussion

Regardless of the section, the interim-testF group always outperformed the restudyT group, revealing both the backward and forward testing effects. All the participants in both conditions were informed that they would be tested on section A or restudy section A as per the format of the final test. Thus, the restudyT group also learned about the final test format before they started studying the second section. Accordingly, similar to the interim-testF group, the restudyT group had an opportunity to modulate their study strategy before studying the subsequent section. However, the results indicated that knowledge about the test format was not sufficient to enhance subsequent learning, suggesting that the benefits of the forward testing effect are not attributable to test format expectations. One possible explanation for such performance differences is that only the participants in the interim-testF condition were able to evaluate what they know and what they do not know during the interim test phase whereas the restudyT group was not able to tell whether they learned well or not. Thus, being exposed to the test format may not necessarily help participants evaluate their learning status and modulate their study strategy.

One caveat of the findings of experiment 2 is that testing may be more effective than restudying only when it is accompanied by feedback. In both experiments 1 and 2, feedback was always provided to the test groups to equate the exposure to painting-artist pairs between the test and restudy conditions. However, it is possible that the interim-testF group outperformed the restudyT group because they received corrective feedback. Indeed, several previous studies have shown that the benefits of testing are further enhanced when feedback is provided (Pashler et al. 2005). To examine whether the forward testing effect remains even in the absence of feedback, experiment 3 included an additional interim-test condition in which feedback was not provided. Participants in the interim-test without feedback condition might not perform as well as those who received feedback as they could evaluate their learning status only subjectively, but not objectively.

One limitation of experiment 2 is that the duration of the interim activity was quite different between the two conditions. In the interim-testF condition, participants were given a self-paced test and feedback was provided for an additional 1.5 s, whereas in the restudyT condition, each painting was presented for a fixed 3 s. Indeed, our analysis revealed that the interim-testF group (M = 3866.35 ms, SD = 1058.15) spent significantly longer time on the interim activity than the restudyT group (3000 ms), t(38) = 3.60, p = 0.001, d = 1.17. Such different duration of the interim activity might have worked as a confound; thus, in the following experiment, we ensured that the interim activities lasted for equal durations of time between the test and restudy conditions.

Experiment 3

In experiment 3, we examined whether the benefit of actual testing can be induced even when an interim test is not accompanied by feedback, compared to exposure to test format by means of restudy. Although many studies reported testing effect in the absence of feedback (Agarwal et al. 2008; Carpenter 2011; Halamish and Bjork 2011; Rowland et al. 2014), feedback still plays a significant role in learning by revealing students what they know and do not know. By realizing the gap between their current and the desired learning status, learners can optimize subsequent learning to fill this gap (Pyc and Rawson 2010, 2012). If corrective feedback plays an important role in the forward testing effect, then participants given an interim test with feedback would perform better than those who receive an interim test without feedback and the restudy group. However, if test experience itself plays an important role, the test groups would always perform better than the restudy group regardless of the provision of feedback.

Method

Participants

Participants were 76 undergraduates (39 women, 36 men; mean age = 22 years) from a large university in South Korea. All the participants received a voucher equivalent to $5. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the three conditions: interim-test, interim-testF, and restudyT conditions.

Three participants were excluded from the analysis. One participant in the interim-testF condition was excluded because the median responding time on the final test was lower than 1 s. Two other participants (1 from the interim-test and 1 from the interim-testF conditions) were excluded because their mean performance scores were 2 SD lower than the average score of the entire groups of participants, resulting in 73 participants in total (24 in the interim-test, 24 in the interim-testF, and 25 in the restudyT).

Design, Materials, and Procedure

As Fig. 1 illustrated, the overall procedure of experiment 3 was similar to that of experiment 2. There were two notable modifications made to experiment 3. First, we included an additional condition: interim-test without feedback. Thus, there were three conditions, interim test without feedback, interim test with feedback, and restudy in testing format. These three conditions are henceforth referred to as the interim-test, interim-testF, and restudyT conditions, respectively. All the participants first studied section A and were subsequently assigned to one of the different interim activities on section A. In the interim-test condition, participants took a multiple-choice test on section A without feedback. In the interim-testF condition, participants took a multiple-choice test on section A and feedback was given for 1.5 s. In the restudyT condition, participants restudied section A in a solved test format. Second, in the restudyT condition, we increased the duration of the intervening activity from 3 to 4 s for each painting presentation. In experiment 2, there was a significant difference between the interim-testF and restudyT conditions in the time spent on the interim activity. This difference might have influenced group difference in performance. Therefore, we calculated the mean of the response times in the interim-testF condition and added 1.5 s (i.e., duration of feedback); this yielded an average duration of 4 s for the interim activity. Accordingly, in the restudyT condition, participants were given 4 s for each painting presented during the interim restudy session. As in experiment 2, the paintings were presented as a solved multiple-choice test format. After the completion of the intervening activity on section A, all the materials and procedures were identical to those of experiment 2.

Results

Interim Test Performance

Participants in the interim-test and interim-testF conditions were tested on section A before studying section B. The mean percentage of correct answers was 80.75 (SD = 14.29) for the interim-test group, and 78.96 (SD = 16.62) for the interim-testF group. The interim test performance was not significantly different between the two conditions, t(48) = 0.27, p = 0.788.

Final Test Performance

Figure 4 shows the mean percentage of correct answers on the transfer test of sections A and B in the interim-test, interim-testF, and restudyT conditions. A 3 × 2 mixed ANOVA was conducted on the number of correct responses. Interim activity (interim-test vs. interim-testF vs. restudyT) was included as a between-subject factor, while section (A vs. B) was included as a within-subject factor. There was a significant main effect of section, F(1, 70) = 13.09, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.158, such that overall performance was significantly better for section B (M = 53.40, SD = 21.46) than for section A (M = 45.48, SD = 21.67). On the other hand, the main effect of interim activity was not significant, F(2, 70) = 0.41, p = 0.67. In other words, the overall final test performance did not differ among the three conditions. More interestingly, there was a significant interaction between interim activity and section, F(2, 70) = 11.20, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.242, implying that the effect of interim activity differed depending on the section.

For section A, one-way between-subject ANOVA did not reveal a significant difference across the three conditions, F(2, 70) = 1.38, p = 0.259. However, for section B, there was a significant difference among the three conditions, F(2, 70) = 5.07, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.126. With respect to the transfer performance of section B, the participants who were given an interim test without feedback (M = 60.50, SD = 15.85) showed significantly better performance than those in the restudyT condition (M = 44.68, SD = 23.03), t(47) = 2.79, p = 0.019, d = 0.80. Participants who received an interim test with feedback (M = 59.13, SD = 18.19) also showed significantly better performance than those in the restudyT condition, t(47) = 2.43, p = 0.019, d = 0.70. However, the mean difference between the interim-test and interim-testF condition was not significant, t(46) = 0.28, p = 0.781, suggesting that the benefits of interim testing are independent of the provision of feedback.

Discussion

The results demonstrated different patterns of performance between the two sections. Regarding the transfer test performance on section A, the participants from the three conditions showed similar levels of performance. Thus, unlike experiment 2, there was no indication of the backward effect of testing. This is perhaps because of the two key differences between experiments 2 and 3. First, experiment 3 had an additional interim test condition without feedback. The lack of feedback in the interim test might have reduced the performance difference between the conditions, and even resulting in superior performance of the restudy condition. Consistent with this explanation, a previous study by Pastötter and Frings (2019) reported a reversed backward testing effect (while still showing a forward testing effect), illustrating a better retention performance from the restudy condition than the test condition when interim tests were not accompanied by feedback. Second, another key difference is the duration of the restudy activity. In experiment 2, the restudyT group spent 3 s restudying each painting of section A, whereas in experiment 3, the restudyT group spent 4 s restudying each painting. The increase in study time might have attenuated the performance difference between the test and restudy groups for section A.

Although there was no backward effect of testing observed, more importantly, experiment 3 again demonstrated a forward testing effect. With regard to section B, both test groups outperformed the restudyT group. That is, regardless of whether feedback was accompanied by the interim test, the test groups always outperformed the restudyT group, indicating a strong forward testing effect. The result is consistent with the findings of Pastötter and Frings (2019), in that a lack of feedback during interim testing perhaps has little effect on the forward testing effect. Consistent with the findings of experiment 2, therefore, simply knowing about the test format was not as effective as actual test experience in enhancing subsequent learning. Experiment 3 suggests that an actual opportunity to test one’s mastery over the studied material is important and that the opportunity to do so may be adequate to enhance learning even in the absence of feedback.

General Discussion

Although extensive research has demonstrated the forward testing effect, the present study was the first to directly compare the effects of test format expectation and actual test experience in inductive learning. Using a forward testing effect paradigm, we manipulated when and how participants were informed about the format of an upcoming final test to examine the effect of knowing about the test format and actual test experience on subsequent learning. To this end, two things were controlled in the present study. First, we controlled the effect of general test expectancy by informing all the participants that they would be tested later at a final test. They were also explicitly informed that they would be presented with new and unfamiliar paintings created by the artists whom they had studied about. Second, we also controlled the effect of knowledge about the test format by requiring participants to engage in different activities that made apparent the format of the final test at different timings (experiment 1) and using different methods (experiments 2 and 3). In experiment 1, participants in the pre-testF condition were informed that they would be given a final test that entails the same format as the pretest. Thus, we predicted that if it is important to know about the test format, then the pre-testF group would outperform the other groups for section A, and perform as well as the interim-test group for section B. However, the pre-testF group did not differ from the restudy group in test performance. Further, the pre-testF group always performed worse than the interim-testF group, suggesting that knowing about the test format in advance did not enhance subsequent learning. Experiment 2 replicated the findings of experiment 1. Participants learned about the test format between the two study sections either by taking a test or by restudying in a correctly solved test format. Although all of them had the opportunity to modulate their study strategy based on the apparent test format, the interim-testF group outperformed the restudyT group. Even though both the test and restudy groups were exposed to the test format at the same timing of the study procedure, knowledge about the test format did not seem to play an important role in the forward effect of testing. Furthermore, experiment 3 showed that testing was effective in enhancing subsequent learning regardless of the provision of feedback. We compared the two interim-test groups: one that received feedback and another that did not receive feedback. Participants who did not receive feedback performed as well as those who did receive feedback on the final transfer test of section B, and they also outperformed the restudyT group, indicating a strong forward testing effect.

Taken together, the results demonstrate that the forward testing effect occurs not just because testing informs learners of the upcoming test format, but probably because testing provides learners with an actual opportunity to evaluate their mastery over the learned material. There could be several explanations that account for the beneficial effects of testing. First, learning about the format of the final test by studying in a testing format (i.e., restudyT condition) might not be as effective as actual test-taking experience in increasing participants’ test expectancy (i.e., “there will be an imminent test”). Although the restudyT group had a test format expectation, they might not have had a steady test expectancy because they were not actually tested. According to the previous studies on test expectancy, only learners who receive intervening tests maintain or increase their test expectancy across different study phases. On the other hand, the restudy group has been found to lower their test expectancy consecutively as the study progresses (Weinstein et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2017). If the participants who restudied the material using a solved test format did not really expect an upcoming test, because they were not actually tested, then their lower test expectancy might have resulted in less encoding effort in the subsequent study session, thus resulting in poorer performance on the final test. Although in all of our reported experiments we explicitly informed the participants that they would be tested later, we cannot eliminate the possibility that a lack of intervening tests may have lowered the test expectancy of the non-tested group of participants. However, it is noteworthy that the pre-testF group of experiment 1 did not benefit from testing even though they were actually tested. Because they were tested at the beginning of their learning, it is very likely that the pre-testF group had a high level of test expectancy. Therefore, test expectancy does not seem to explain the major results of the current study. Admittedly, one limitation of the current study is that we did not explicitly ask participants to report their test expectancy or test format expectation. Future studies may ask participants to self-report the level of their test expectancy and/or test format expectation to investigate whether these measures differ depending on when and how intervening activities are introduced, even when exposure to the test format is controlled for.

An alternative and more plausible explanation for the findings of this study is that prior knowledge about the test format may be less effective when it is gained by means of restudying than actual testing. When participants take an actual test, they have to retrieve what they have previously learned. For example, participants have to identify a certain painting style of a given painting and retrieve whose work has that painting style. Such retrieval attempts during interim testing might have induced context change (Bäuml and Kliegl 2013; Pastötter et al. 2011; Szpunar et al. 2008) and encouraged more effective encoding and retrieval strategies (Cho et al. 2017). Because only the participants in the interim test condition experience a context change from a study to test context, such change might have reduced the buildup of proactive interference (Szpunar et al. 2008) or induced a reset of subsequent encoding (Pastötter et al. 2011). Also, only the test group could evaluate the effectiveness of their prior study strategies during interim testing and thus they could have adopted more effective encoding or efficient learning strategies (Cho et al. 2017). Additionally, retrieval failure during interim tests might have motivated learners to exert more effort toward encoding new information on their subsequent study (Cho et al. 2017). However, when participants restudy in a solved test format, although they can clearly see what a final test would be like, they do not have to retrieve anything from their memory.

Indeed, several studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of retrieval attempts (Grimaldi and Karpicke 2012; Hays et al. 2013; Kornell et al. 2009; Lee and Ha 2019). For example, Lee and Ha (2019) found that the mere act of making judgments of learning (JOLs) on previously learned material facilitated subsequent learning of new material when it was accompanied by retrieval attempts. They had participants learn the painting styles of various artists, which were divided into two sections. Then they asked them to provide metacognitive judgements, take an interim test, or restudy the material for the first section. In experiment 1, when participants made item-level JOLs on every artist-painting pair, and thus when they were unlikely to have a retrieval attempt, making metacognitive judgments did not enhance subsequent learning compared to restudy. However, in experiment 2, when participants made category-level JOLs on each artist in the absence of accompanying paintings, and thus when they were more likely to have a retrieval attempt, making metacognitive judgments facilitated subsequent learning compared to restudy. These findings suggest that an act of retrieval is critical to the forward testing effect.

One surprising and interesting finding is that pretesting effect was not obtained in the present study. The current study is the first to investigate the effect of taking a pretest in inductive learning. Although numerous studies have examined the effect of pretesting, most of them have focused on memory performance (e.g., Hays et al. 2013; Kornell et al. 2009; Richland et al. 2009). Experiment 1 revealed that only the interim-testF condition, but not the pre-testF condition, performed significantly better than the restudy condition. The performance of the pre-testF group was similar to that of the restudy group on both sections. This suggests that the opportunity to evaluate one’s mastery over the studied material rather than the mere act of taking a test seems more crucial to the enhancement of subsequent learning. Although the pre-testF group learned about the final test format via an actual test experience, they could not evaluate their own learning because they had not yet studied any material prior to the pretest. The superior performance of the interim-testF group over the pre-testF group suggests that, in some situations, testing may be effective only when it allows learners to evaluate their current learning status. This finding of the current study is consistent with the previous research showing superior benefits of postquestions over prequestions (Geller et al. 2017; Latimier et al. 2019). For example, Geller and his colleagues (Geller et al. 2017) showed that the postquestions which were conducted after the lecture were more effective than the prequestions which were conducted before the lecture. Likewise, Latimier et al. (2019) reported a greater effect size of the post-test (d = 0.74) than the pre-test (d = 0.35), implying that it is more effective to take a test after than before study.

Still, the pretesting effect has been demonstrated across a wide range of materials. There are two possible explanations that may account for why the previously reported benefits of pretesting were not observed in the present study. First, the pretest used in our research may not have been a suitable means to activate learners’ prior knowledge. One known benefit of pretesting is that learners can activate the knowledge relevant to the target study materials during pretesting and in turn integrate that knowledge with the retrieval cues that they gain from the pretest (Grimaldi and Karpicke 2012; Kornell et al. 2009; Vaughn and Rawson 2012). For example, when given a pretesting question such as “what is total color blindness caused by brain damage called?,” even when people do not know the correct answer, they can activate related information about color blindness, and this in turn can enhance subsequent learning (Richland et al. 2009). However, the paintings used in our experiment were from relatively unknown artists; thus, participants may have not been able to activate their background knowledge during the pretest. Second, it is possible that participants might have treated the pretest merely as a study session. It is obvious that they could not correctly solve the problem at the beginning of the pretest. Indeed, their average accuracy was 38% on the first block (i.e., the first six problems) of the pretest. Accordingly, the participants may have chosen to study the feedback that was provided after their response rather than trying to test their learning by solving the problem. Such a strategy, however, will eventually put the pre-testF group in the same condition as the restudy group. Instead of trying to retrieve information, they may have just observed a given painting and relied on the feedback.

One limitation of the current study is that we used only multiple-choice tests across all the three experiments. We used this format because it was not possible to provide participants with a cued-recall test during the first phase of the experiment (i.e., pretest), obviously because they had not yet learned anything. However, there is a possibility that the effect of pretesting changes depending on the characteristics of pretests, including the test format, difficulty level, and duration of feedback. For example, although the current study provided participants with feedback during the pretest, choosing an incorrect answer might have interfered with their learning of correct artist-painting pairs. In addition, difficult pretests could have demotivated learners to solve the problems and influenced the level of effort that they invested in subsequent learning. The duration of feedback may also play an important role. The current study provided feedback for 1.5 s, and this was to equate the amount of study time between the interim-testF and pre-testF conditions. However, the feedback would be much more important in the pre-testF condition given that they had no prior study phase. Future studies are required to investigate the pretesting effect in inductive learning by varying the format and difficulty level of the test.

Another limitation is that the effect of feedback might change depending on the difficulty or performance level of interim tests. Although we demonstrated the forward testing effect regardless of feedback, the provision of feedback may play a more important role when an interim test is difficult; thus, the test provides leaners with an opportunity for improvement during interim testing. In experiment 3, the mean performance of the interim test was about 80%, implying that participants perhaps had achieved high level of learning before taking the interim test. When learning from the first study section is poor, students may have to learn through trial by trial feedback, and this will provide learners with a better opportunity to adjust their learning strategies.

Overall, the findings of the present study have a potentially important theoretical and educational implication. Although numerous studies have shown that testing of previously studied information enhances retention of subsequently studied other information (for a review, see Yang et al. 2018), only a few studies (Lee and Ahn 2018; Lee and Ha 2019; Yang and Shanks 2018) have investigated the forward testing effect in inductive learning. The current study offers another evidence that testing enhances inductive learning of new material. In the present study, participants had to abstract general patterns of the paintings and apply what they had learned to novel paintings created by the artists who were studied. Although the current study included only transfer problems at the final test, we also have evidence showing that testing helps retention of previously studied material (the backward testing effect; Jacoby et al. 2010) and of newly studied material (the forward testing effect; experiment 4 in Lee and Ahn 2018) in inductive learning. All together, these results suggest that forward testing effect is a robust phenomenon in both retention and transfer learning. Besides, the current study provides evidence that such benefit of testing seems more attributable to actual test experience than the knowledge about the test format, regardless of whether feedback is provided or not during interim testing.

In addition to the theoretical implication, the present study has practical implications for real educational settings. When students prepare for exams, they often ask their teachers about the format of the test they will receive. Students believe that knowing about the test format will help them better prepare for the test. Indeed, several previous studies have illustrated that students change their study strategies according to the anticipated test format and improve their learning performance (Finley and Benjamin 2012; Middlebrooks et al. 2017). However, the current study revealed that knowing about the test format and studying in accordance with the anticipated test format were found to not be as effective as actual test experience. According to the findings of the three experiments, simply knowing about the test format in advance of the study was not as effective as taking an actual test. Also, the beneficial effects of actual test tasking differed depending on when the test was administered. Taking a test before any learning had occurred did not enhance subsequent learning. Only interim testing (testing after initial learning had occurred) enhanced subsequent learning, and this seemed to be because testing allowed learners to evaluate their learning status and modulate their study strategies accordingly. Thus, in order to enhance learning, it may be better for teachers to provide students with an actual practice test, rather than simply inform them about the format of the test. For example, teachers may interpolate a lecture with tests. Szpunar et al. (2013) showed that such intervening tests helped encourage students to engage in learning-relevant activities while discouraging learning-irrelevant activities, thus improving learning. Specifically, while taking an online statistics course, students who were given intervening tests showed less mind wandering, more note-taking activities, and reduced test anxiety toward a final test than those who were not tested. Testing seems to be a powerful tool for effective learning in educational settings.

Conclusion

Knowledge about the test format did not account for the forward effect of testing in inductive learning. Instead, having actual test-taking experience in the middle of the study always led to enhanced performance in subsequent learning of new material. Therefore, for effective inductive learning, it is not sufficient to merely know about the test format or expect a subsequent test. What matters most is actual test experience, regardless of whether feedback is provided during interim testing or not.

References

Agarwal, P. K., & Roediger III, H. L. (2011). Expectancy of an open-book test decreases performance on a delayed closed-book test. Memory, 19(8), 836–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2011.613840.

Agarwal, P. K., Karpicke, J. D., Kang, S. H. K., Roediger III, H. L., & McDermott, K. B. (2008). Examining the testing effect with open- and closed-book tests. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22, 861–876. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1391.

Arnold, K. M., & McDermott, K. B. (2013). Test-potentiated learning: distinguishing between direct and indirect effects of tests. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39(3), 940–945. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029199.

Aslan, A., & Bäuml, K. H. T. (2016). Testing enhances subsequent learning in older but not in younger elementary school children. Developmental Science, 19(6), 992–998. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12340.

Bäuml, K. H. T., & Kliegl, O. (2013). The critical role of retrieval processes in release from proactive interference. Journal of Memory and Language, 68, 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.07.006.

Bufe, J., & Aslan, A. (2018). Desirable difficulties in spatial learning: testing enhances subsequent learning of spatial information. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1701. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01701.

Carpenter, S. K. (2011). Semantic information activated during retrieval contributes to later retention: support for the mediator effectiveness hypothesis of the testing effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37, 1547–1552. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024140.

Chan, J. C. K., Manley, K. D., Davis, S. D., & Szpunar, K. K. (2018a). Testing potentiates new learning across a retention interval and a lag: a strategy change perspective. Journal of Memory and Language, 102, 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2018.05.007.

Chan, J. C. K., Meissner, C. A., & Davis, S. D. (2018b). Retrieval potentiates new learning: a theoretical and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 144(11), 1111–1146. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000166.

Cho, K. W., Neely, J. H., Crocco, S., & Vitrano, D. (2017). Testing enhances both encoding and retrieval for both tested and untested items. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70, 1211–1235. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2016.1175485.

Davis, S. D., & Chan, J. C. K. (2015). Studying on borrowed time: how does testing impair new learning? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 41, 1741–1754.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

Finley, J. R., & Benjamin, A. S. (2012). Adaptive and qualitative changes in encoding strategy with experience: evidence from the test-expectancy paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38(3), 632–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026215.

Geller, J., Carpenter, S. K., Lamm, M. H., Rahman, S., Armstrong, P. I., & Coffman, C. R. (2017). Prequestions do not enhance the benefits of retrieval in a STEM classroom. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 2(1), 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-017-0078-z.

Gordon, L. T., & Thomas, A. K. (2017). The forward effects of testing on eyewitness memory: the tension between suggestibility and learning. Journal of Memory and Language, 95, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2017.04.004.

Grimaldi, P. J., & Karpicke, J. D. (2012). When and why do retrieval attempts enhance subsequent encoding? Memory & Cognition, 40(4), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-011-0174-0.

Halamish, V., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). When does testing enhance retention? A distribution-based interpretation of retrieval as a memory modifier. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37, 801–812. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023219.

Hays, M. J., Kornell, N., & Bjork, R. A. (2013). When and why a failed test potentiates the effectiveness of subsequent study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39, 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028468.

Jacoby, L. L., Wahlheim, C. N., & Coane, J. H. (2010). Test-enhanced learning of natural concepts: effects on recognition memory, classification, and metacognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36, 1441–1451. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020636.

Jing, H. G., Szpunar, K. K., & Schacter, D. L. (2016). Interpolated testing influences focused attention and improves integration of information during a video-recorded lecture. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 22(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000087.

Kang, S. H. K., & Pashler, H. (2012). Learning painting styles: spacing is advantageous when it promotes discriminative contrast. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26, 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1801.

Kapur, M., & Bielaczyc, K. (2012). Designing for productive failure. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 21, 45–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2011.591717.

Kornell, N. (2014). Attempting to answer a meaningful question enhances subsequent learning even when feedback is delayed. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40, 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033699.