Abstract

Social perspective-taking is a multifaceted skill set, involving the disposition, motivation, and contextual attempts to consider and understand other individuals. It is essential for appropriate behavior in teaching contexts and social life that has been investigated across various research traditions. Because social perspective-taking enables flexible reappraisals of social situations, it can facilitate more harmonious social interactions. We aimed to systematically review the disparate literature focusing on adults’ social perspective-taking to answer the overarching question: Are there findings on factors that positively or negatively related to adults’ social perspective-taking as possible protective factor for mental health? Specific questions were which internal or external factors are related to either dispositional or situation-specific social perspective-taking and are both forms related to each other, or do they vary independently of each other in response to these factors? We reviewed 92 studies published in 56 articles in last ten years including 213,095 healthy adults to answer these questions. The findings suggested several factors (e.g., gender, perceived social interactions) related to the dispositional form. Negative relationships to self-reported or tested (cortisol levels) distress suggested dispositional social perspective-taking as a protective factor for mental health. Dispositional social perspective-taking related to the situational form and some findings suggested changes in both forms through intervention. Thus, coordinating different perspectives on oneself or others reflects flexibility in behavior related to positive social and mental health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Adults need to see and understand others’ perspectives in order to make socially and professionally appropriate responses within group contexts (e.g., Gehlbach 2004). Health research findings suggest self-reported low levels of distress to be related to the tendency to understand others’ perspectives in diverse social situations (see Wilkinson et al. 2017 for a review). For example, teaching is a special context that involves diverse group situations, raising the question of whether dispositional or situational factors are related to adults’ social perspective-taking in teaching situations. Educational research findings indicate that some teachers appear to consider and support students similar to themselves to a greater extent (Gehlbach et al. 2016), while other teachers neglect to consider students’ learning prerequisites, such as beliefs about skills or depressive mood (e.g., Bilz 2014). These teachers appear to focus on themselves rather than on their students; they do not attempt to see what their students see. We assumed that teachers’ seeing and understanding students’ perspectives may play a key role in considering students and their learning prerequisites. Our aim was to find evident factors which explain high levels or low levels of seeing and understanding others’ perspectives for new approaches in teacher education and teacher training.

Seeing what other people see basically involves a skill set (e.g., Erle and Topolinski 2015, 2017; Hegarty and Waller 2004) related to visuo-spatial perspective-taking that is activated in a social situation or context (e.g., Engen and Singer 2012). Social perspective-taking, broadly defined, allows us to represent another’s mental perspective and helps us to understand another individual’s behavior (e.g., Davis 1983). In the narrower sense, social perspective-taking involves both seeing a target person’s circumstantial point of view and being motivated to discern the target’s thoughts, motivations, and feelings in order to make accurate inferences about their perspective (Gehlbach and Brinkworth 2012; Zaki 2014). Motivation and willingness are necessary to discern available sources of evidence (e.g., using information about the target, conversation contents, or eye movements, Gehlbach and Brinkworth 2012) for social perspective-taking and to use underlying skills (e.g., mentalizing, Engen and Singer 2012; mental self-rotation, Erle and Topolinski 2017) for accurate assumptions about the target.

Research on social perspective-taking encompasses a number of different conceptual and theoretical as well as methodological approaches. Within the social perspective-taking literature, primarily, two approaches are employed and relate to different conceptual aspects of perspective-taking: (1) Social perspective-taking as disposition, the tendency to imagine another’s perspective and circumstances, across various contexts (e.g., Davis 1983; Mooradian et al. 2011), further referred to as dispositional. Davis (1980) and other researchers have described it as the cognitive dimension of empathy (e.g., Mattan et al. 2016). This dispositional social perspective-taking is often measured using a standardized inventory (e.g., Davis 1980). (2) Social perspective-taking assessed using photo, animation, or video-based tasks (e.g., Erle and Topolinski 2017; Gehlbach et al. 2012c), further referred to as situational, reflects current capacities in a specific social situation. These cognitive capacities are often assessed in experiments using various terminologies and paradigms to simulate specific social situations which require executing social perspective-taking (e.g., Ames 2004a, b; Ames et al. 2008, 2010; Epley et al. 2006; Pierce et al. 2013; Sassenrath et al. 2016). Both the dispositional and situational performance per definition imply perspective-taking with reference to a human(-like) or social target (e.g., Deroualle et al. 2015).

Situational social perspective-taking deals with the cognitive capacity to establish and flexibly modify a mental representation of another person’s perspective and circumstances. This mentalizing can be done remaining fixedly anchored in oneself, thus putting oneself in the shoes of another person and her circumstances (What would I think or do in that situation?), or simply execute projection or stereotyping (e.g., Ames 2004a; Gehlbach and Brinkworth 2012; Gehlbach and Vriesema 2019; see also Batson et al. 1997; Epley et al. 2004; Mattan et al. 2016). However, the further capacity to imagine the other person’s self and her circumstances as if one was this person requires a flexible self-anchoring (When I was this person, what would I think or do? e.g., Batson et al. 1997; Mattan et al. 2016). This mentalizing, in turn, may help us to regulate our emotional responses (e.g., Engen and Singer 2012) within positively experienced social interactions and negatively experienced conflict situations.

Interestingly, high levels of dispositional or (experimentally induced) tested physiological distress are related to deficits in social perspective-taking in individuals (e.g., Batson et al. 1997; Buffone et al. 2017; Lamm et al. 2007). Distress in these contexts is induced with stimuli which trigger negative emotional responses in an individual. Indeed, a chronic state of distress in terms of a chronic imbalance between requirements and protective factors for mental health might also be related to deficits in social perspective-taking levels. An investigation of the relationship between self-reported distress, social perspective-taking, and any mitigating factors is timely, given Americans’ dispositional social perspective-taking decreased significantly in 2010 compared to 1979 and 2000 (Konrath et al. 2011), as indexed by scores from the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis 1980), a commonly used dispositional social perspective-taking scale. Since we were interested in factors that are positively or negatively related to adults’ dispositional or situational social perspective-taking, we focused on research that social perspective-taking included as correlate (nondirected relations) or dependent variable.

Engen and Singer (2012) proposed a core network model of empathy including perspective-taking that we used as template for an extended integrating framework (see Fig. 1). The core network model of empathy is outlined in the next section. Drawing upon this model (Engen and Singer 2012), we aimed to demonstrate a proof of concept for this model by systematically reviewing both correlational and experimental behavioral findings on dispositional and situational social perspective-taking.

Integrated framework of social-perspective-taking (based on Duran and Dale 2014; Engen and Singer 2012; Epley et al. 2004; Gehlbach 2010, 2011; Johnson and Johnson 2005; Libby and Eibach 2011). 1Working memory (e.g., Meyer and Lieberman 2016) and executive functions are probably involved in executing social perspective-taking (e.g., Ruby and Decety 2003)

Theoretical Approaches on Social Perspective-Taking

Examples of prominent theoretical approaches to the social perspective-taking construct are the Piagetian theory; the concept of theory of mind; social coordination after Selman (1980); or perspective-taking as a dispositional tendency exhibited across various situations (Davis 1980). The ability to step outside oneself and assume others’ points of view is a cognitive capacity crucial to the development of the self and cognitive skills through interactions (Mead 1934). Social interactions and cognitive development are linked to the emergence of formal operations, including the capacity to engage in making assumptions and deductive reasoning, logical reasoning, and construing reality from various possibilities (Piaget and Cook 1952). This skill set has been seen as fundamental to perceiving oneself and others and adequately interpreting social interactions and relationships (Brown 1986; Fischer 1980; Lewis and Brooks-Gunn 1979).

Selman (1980) proposed a developmental view on situational social perspective-taking. He defined social perspective-taking in children and adults as coordinating two or more perspectives (e.g., oneself and another’s, or oneself and others’ intentions, Selman 1980). Social perspective-taking in terms of mind reading is conceptualized within the cognitive developmental framework of theory of mind (e.g., Baron-Cohen et al. 1985; Bukowski and Samson 2015; Converse et al. 2008; Schneider et al. 2012; Todd et al. 2015; Wimmer and Perner 1983). Theory-of-mind research largely focuses on the development of the ability to distinguish between oneself and other individuals (e.g., desires, beliefs) in children, changes over time in children and adolescents (e.g., Derksen et al. 2018; Milligan et al. 2007), and cultural variation (e.g., Lillard 1998). False-belief tasks are a prominent method for examining (the development of) young children’s (e.g., the famous Sally-Anne task), adolescent’s, or adult’s theory of mind (e.g., Baron-Cohen et al. 1985; Derksen et al. 2018).

The term perspective-taking is mentioned in syntheses of theory of mind research from 2006 and 2007 (e.g., Milligan et al. 2007; Rao et al. 2007; Singer 2006). Then, Singer (2006, p. 856) proposed to differentiate the concepts “theory of mind,” “emotional empathy,” and “perspective taking.” In accordance with that proposal, having the ability to distinguish between oneself and another’s mental perspective (i.e., theory of mind) is in our view a prerequisite for social perspective-taking instead of a synonym for the same. While a shared history has resulted in both conceptual and methodological overlaps between the social perspective-taking and theory of mind research traditions, future research should better disentangle these two constructs conceptually and empirically. Thus, theory-of-mind research per se is outside the scope of this systematic review in which we aimed to provide an overview of research on social perspective-taking specifically. Accordingly, given the overlap in usage of terms prior to Singer’s 2006 proposal, we only included research on adults’ social perspective-taking from last 10 years in our PROSPERO pre-registration protocol. Research beyond that point is more selective for social perspective-taking independent of theory of mind; indeed, two recent syntheses on theory of mind (Schaafsma et al. 2016; Derksen et al. 2018) do not even mention the term perspective-taking.

Both developmental approaches are consistent in that they assume that perspective-taking is a cognitive capacity that children learn but use differently in different contexts. Thus, adults who have normally developed this cognitive capacity are able to use social perspective-taking appropriately in a given social context (e.g., Bloom and German 2000; Epley et al. 2004; German and Hehman 2006) without instruction (e.g., Eyal et al. 2018). However, these approaches do not explain adults’ such as teachers’ intraindividual and interindividual differences in social perspective-taking.

A comprehensive approach relating to individual dispositions and situational social perspective-taking is based on literature reviews and meta-analytic results (e.g., Engen and Singer 2012; Lamm et al. 2011). It is the core network of empathy model that explains intra- and interindividual differences in empathic responses by the role of establishing a mental representation of the target individual based on perception (Engen and Singer 2012; Libby and Eibach 2011), modulation, and regulation (Engen and Singer 2012). Modulational factors are one’s own characteristics or dispositions (e.g., dispositional social perspective-taking, Gehlbach 2010, 2011; gender, mood, or personality traits, Engen and Singer 2012; see also Borkenau, and Tandler 2015 for an overview), features of the target, the relationship between oneself and the target individual (Engen and Singer 2012; see also Davis 2018 for similarity), and features of the other’s state (i.e., valence, intensity and salience, Engen and Singer 2012; see Fig. 1). Factors assigned to regulation are contextual appraisal of the perceived situation, affect, and social perspective-taking (e.g., Engen and Singer 2012; Libby and Eibach 2011). Briefly, the core network model of empathy summarizes the networks and factors involved in mentalizing, action simulation by information of a target person in a given context, and cognitive processes for emotion regulation (Engen and Singer 2012; Libby and Eibach 2011). Intraindividual emotion regulation (e.g., Webb et al. 2012) is known to be a resource for dealing with subjectively challenging situations, preventing states of distress, and protecting health.

Evidence from Previous Research

Social perspective-taking with a focus on the target person has been related to beneficial effects on cardiovascular health (e.g., Buffone et al. 2017). Underwood and Moore (1982) reviewed the existing literature on the mediating role of perspective-taking forms (e.g., social vs. visuo-spatial) on the development of altruism in children and adults. Their meta-analytic results showed gender differences based on the method of testing. For example, social perspective-taking differed between men and women (with women having an advantage) when self-report measures were used but there was no difference when physiological measures or covert observation were used (e.g., Eisenberg and Lennon 1983). Thus, gender is a relevant factor for dispositional social perspective-taking.

Davis (1980) proposed social perspective-taking as one dimension of the multidimensional construct of empathy beside empathic concern, fantasy, and personal distress. Considering Davis’ work, Gehlbach (e.g., 2004) conceptualized and investigated social perspective-taking as a multidimensional construct including the main two dimensions: (1) ability measured by accuracy in reading another person’s thoughts and feelings, and (2) motivation (i.e., is one motivated to try to read someone else’s thoughts and feelings in the first place, Gehlbach 2004). The motivation dimension can be further distinguished with respect to one’s motivation to engage in a particular social-perspective-taking episode vs. one’s motivation to engage in social perspective-taking across situations. The latter represents dispositional social perspective-taking or social-perspective-taking propensity (Gehlbach 2004).

Moreover, Chambers and Davis (2012) described an ease of self-simulation heuristic for dispositional and situational social perspective-taking. They assumed that differences in adults’ situational social perspective-taking might be explained by whether it takes more or less effort to mentalize about the target’s mind or to see what a target person sees: Situational social perspective-taking is more likely when self-simulation is easier, e.g., when similarities with the target person are perceived. As they predicted, high levels of dispositional social perspective-taking (e.g., Mattan et al. 2016) and perceived similarity (e.g., Chambers and Davis 2012) or dissimilarity (e.g., Simpson and Todd 2017; Tamir and Mitchell 2013; Todd et al. 2011) with the target have been found to be relevant factors for adults’ situational social perspective-taking. There are indeed further research branches on social perspective-taking in various contexts (e.g., Ingraham 2017), however, often outside educational contexts and including social perspective-taking as predictor variable instead of including it as dependent variable (e.g., Galinsky et al. 2005; Galinsky et al. 2008; Galinsky and Moskowitz 2000; Galinsky and Mussweiler 2001).

Taken together, the cognitive capacity to consider other individuals’ points of view via situational social perspective-taking processes could be a function of dispositional social perspective-taking as well as further relevant factors (e.g., gender, similarity). Several syntheses published in 2006 and 2007 provided overviews of existing evidence on theory of mind research from different periods of time (e.g., Milligan et al. 2007). Perspective-taking is mentioned a few times in these syntheses beside the central feature to distinguish between oneself and other individuals when one has a theory of mind (e.g., Milligan et al. 2007).

However, there is a lack of systematically reviewed literature in which studies are explicitly published under the label social perspective-taking. The relationships between social perspective-taking and positive social interactions or distress for mental health have rarely been addressed in systematic reviews. We assumed that intraindividual factors (e.g., gender, dispositional social perspective-taking, see Fig. 1), and contextual factors (e.g., characteristics of the target person and social relationship, Duran and Dale 2014; Engen and Singer 2012; Johnson and Johnson 2005) would affect situational social perspective-taking as proposed for empathy (Engen and Singer 2012). Furthermore, we expected intraindividual changes over time involving dispositional (e.g., Konrath et al. 2011) or situational social perspective-taking through intervention. A systematic overview of published studies would suggest first insights on whether adults’ dispositional and situational social perspective-taking skills are related to each other, as well as whether they are related to the internal and external (protective) factors discussed above. This is highly important for teachers’ seeing what students see and understanding behaviors of these students.

The Current Review

We adapted the core network model of empathy to dispositional and situational social perspective-taking skills, drawing upon previous theoretical contributions (e.g., Davis 2018; Gehlbach 2010, 2011; Libby and Eibach 2011; see Fig. 1). We expected dispositional and situational social perspective-taking to be related to known protective factors for mental and physical health, e.g., perceived positive social interactions and social relationships, low levels of distress, and low levels of cortisol, in correlational studies among adults. We were mainly interested in determinants of dispositional or situational social perspective-taking but also included studies with dispositional or situational social perspective-taking as a correlated variable.

We asked whether dispositional social perspective-taking affects adults’ situational social perspective-taking skills (assessed by self-report measures vs. tasks respectively); whether there are published findings available on this relationship; and whether relevant internal and external factors are related to dispositional and situational social perspective-taking. If specific conditions activate social perspective-taking processes, is there an interplay between malleable dispositional social perspective-taking and situational social perspective-taking? Here, we invoke the term malleability to refer to changes in dispositional and situational social perspective-taking due to either a specific intervention or the passage of time.

The primary outcome of interest from published studies was a proof of concept by findings of dispositions or conditions which improve dispositional or situational social perspective-taking. Evidence of intraindividual variability in personality (e.g., Fleeson 2004) or changes in personality through intervention (Roberts et al. 2017) let us expect changes in dispositional social perspective-taking through intervention as well. The secondary outcome of interest was evidence of changes in dispositional or situational social perspective-taking through intervention or over time. Accordingly, the research questions were as follows: (1) Do men and women differ in dispositional or situational social perspective-taking? (2a) What are predictors of social perspective-taking? (2b) Which factors relevant for school and health are related to social perspective-taking? (3) Which situational factors predict high levels of situational social perspective-taking? (4) What proportion of situational social perspective-taking is related to dispositional social perspective-taking? (5) What evidence is there to support the hypothesis that dispositional or situational social perspective-taking can be changed?

Method

Selection Criteria

Target individuals for the current systematic review were healthy adults above 18 years of age who participated in correlational or experimental studies presented in original peer-reviewed empirical articles; we also included peer-reviewed theoretical contributions (published in English or German). Studies of individuals under 18 years of age were excluded, as were those concerning adults diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, mental illness, or requiring additional support.

We included studies investigating both dispositional and situational social perspective-taking. However, studies on perspective-taking that did not include human(-like) targets were excluded due to our initial research question regarding adults in social situations. Previous syntheses already summarized evidence on theory of mind (e.g., Derksen et al. 2018) and empathy (e.g., Engen and Singer 2012). Due to scientific consensus that healthy adults have normally developed a theory of mind, which serves as a foundation for social perspective-taking processes (e.g., Bloom and German 2000), studies including the words “theory of mind” in the abstract or keywords or which focused on false-belief tasks were excluded. Finally, relational frame theory paradigms—which involve deictic relations that anchor a person’s perspective here and now (i.e., I is coordinated with here and now), and conversely, anchor the perspectives of others there and then (e.g., you is coordinated, from my perspective, there and then)—were excluded due to the focus on aspects of language related to executive functions (e.g., shifting between relational frames, Wolgast and Barnes-Holmes 2018).

Systematic Literature Search Procedures

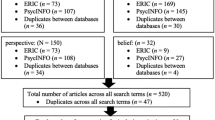

We followed search procedures outlined in our research protocol in accordance with systematic review guidelines (Moher et al. 2015; Shamseer et al. 2015). The protocol is available on PROSPERO (number: CRD42***BLINDED FOR PEER REVIEW). In contrast to recently discussed preregistrations of research hypotheses for experimental or correlational studies (e.g., Gehlbach and Robinson 2018), a PROSPERO protocol requires to set the research questions, searching strategy (i.e., which databases will be used), and inclusion and exclusion criteria for conducting a systematic review (Moher et al. 2015; Shamseer et al. 2015). First, we initially specified subject terms in English (e.g., “social perspective-taking,” “perspective-taking,” “empathy,” the complete list of terms can be obtained by the authors for reasons of space) to conduct the systematic review using electronic databases (ERIC, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and PubPsych). These subject terms were combined with the inclusion or exclusion criteria mentioned above, which we expected to find in the title, abstract, or keywords of a publication. We additionally conducted a broad search for articles containing the words “perspective-taking AND social” or “perspective-taking AND empathy” in the title, abstract, or keywords to ensure that we had identified all relevant articles. We then conducted manual searches of the references of eligible articles and key review articles. We re-ran our database searches twice over several months and retrieved a further 16 studies for inclusion. An overview gives the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram including numbers of records at each step of our systematic literature searching identification, screening, and eligibility that can be obtained from the authors for reasons of space (template from Moher et al. 2009).

Overall, the searches initially resulted in 220 publications from the databases. Manual searches of the references of eligible articles resulted in 30 publications as summarized in the flow chart. One of three post-doctoral researchers in psychology (the authors) and one student assistant (psychology graduate) screened the search results, which were then cross-referenced by the second and third researchers.

We looked for research, including theoretical contributions, on dispositional or situational social perspective-taking published between January 2008 and October 2018 due to the above-mentioned published reviews in 2006 and 2007 (Milligan et al. 2007; Rao et al. 2007; Singer 2006). Theoretical contributions were identified and incorporated into the theoretical framework (see the integrated framework in Fig. 1 for an overview). This identification step further involved two researchers screening the titles to identify ineligible records or duplicates; 22 records were excluded due to obvious ineligibility from the title and keywords or because they were duplicates. We sent inquiries for full texts to the first authors if full texts were not otherwise available.

In a second step, we screened the full texts of 214 publications and excluded 149 contributions according to the exclusion criteria defined in the protocol mentioned in the paragraph above or because of missing information (e.g., authors reported aggregate data but not the sample size at the individual level). We also reviewed the reference lists of the included studies for further eligible publications. Articles containing results on perspective-taking in adults with mental disorders, diseases, or the need for additional support, as well as a control group, were screened; we only included the control group.

Afterwards, a total of 56 publications presenting correlational and experimental studies remained for the systematic review, as displayed in Table 1. Our criteria for assessing study quality were that the following points be described: sample size for analysis, including the number of female or male participants; materials or measures used; survey or experimental procedure; description of appropriate statistical analysis and results. Questions or disagreements during the screening procedures were discussed and resolved in two one-to three-hour lab meetings per month.

Summary of Review Results

The systematic literature search procedures resulted in 56 full texts: 20 full texts including 29 correlational studies and 36 full texts including 63 experimental studies. The full texts of all of these 56 included articles were screened by one of the three researchers and the student assistant to obtain information relevant to our research questions. Another of the three researchers cross-checked the extracted information. We discussed the information in lab meetings twice a month. The 92 studies differed in research design, for example, the combination of measures in correlational studies or the research paradigms used in experimental studies. Table 1 gives an overview of the sample sizes and relevant results extracted from the full text screening of the correlational and experimental studies. Dispositional social perspective-taking was assessed in both correlational and experimental studies: as a dependent variable in six correlational studies and 27 articles from experimental research. Interestingly, the majority of these studies involved the original (e.g., Barr 2011) or an adapted version (e.g., Bostic 2014) of the dispositional perspective-taking subscale of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) developed by Davis (1980). We present the results of the systematic review grouped according to our initial questions as follows.

(1) Do men and women differ in dispositional or situational social perspective-taking? Men and women differed in dispositional social perspective-taking where women consistently have an advantage (e.g., Diehl et al. 2014; Leibetseder et al. 2001; O'Brien et al. 2013). However, the reviewed studies included in our systematic review found no differences between male and female participants with regard to the situational form visuo-spatial social perspective-taking accuracy (e.g., Arzy et al. 2006; Erle and Topolinski 2015; Mohr et al. 2010; Theodoridou et al. 2013; see Online Resource 1 for task descriptions).

(2a) What are predictors of social perspective-taking?

Gender, age, self-reported distress, and physiological distress differently predicted dispositional social perspective-taking: In cross-sectional large-scale research, dispositional social perspective-taking described an inverted u-curve between 18 and 89 years of age with a plateau between 48 and 64 years of age (e.g., O’Brien et al. 2013). Self-reported low distress levels (e.g., Buffone et al. 2017; see Table 1 for a summary) or measured low cortisol levels (e.g., Engert et al. 2014) were related to high levels of dispositional social perspective-taking. Further findings suggested a relationship between self-reported distress and threat in an imagine-self perspective-taking condition but not in an imagine-other perspective-taking condition. This relationship between distress and situational social perspective-taking is in line with other findings (e.g., Batson et al. 1997; Chambers and Davis 2012; see Online Resource 1 for task description) that suggest a need to distinguish between imagining how another feels and imagining how you would feel as two different forms of situational social perspective-taking with different empathic consequences.

(2b) Which factors relevant for school and health are related to social perspective-taking? Motivation (e.g., Pavey et al. 2012; Sassenrath et al. 2014) or the big-five personality dimensions openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness (except neuroticism, e.g., Mooradian et al. 2011) were positively related to adults’ dispositional social perspective-taking. For example, agreeableness is linked to cooperativeness that predicted adults’ dispositional social perspective-taking in research on cooperative learning (Johnson and Johnson 2005). Self-reported distress (e.g., Kordts-Freudinger 2017), antisocial behavior problems (Bach et al. 2017), and subclinical narcissism (e.g., Hepper et al. 2014) were negatively related to adults’ dispositional social perspective-taking. Davis (1983) already found a negative relationship between self-reported distress and adults’ dispositional social perspective-taking. Kordts-Freudinger (2017) conceptually replicated this negative relationship with university teachers and teaching assistants.

Teachers’ years of teaching experience and positive expectations for students (Bostic 2014), and adults’ supportive responses to children (Swartz and McElwain 2012) or adults (Verhofstadt et al. 2016) were further factors that positively related to dispositional social perspective-taking. (3) Which situational factors predict high levels of situational social perspective-taking? The own perspective (e.g., Agarwal et al. 2017, Mohr et al. 2013; Surtees et al. 2016; Wilson et al. 2017) vs. seeing what someone else sees predicted situational social perspective-taking with adults’ faster responses in own-perspective conditions (e.g., Deroualle et al. 2015; Santiesteban et al. 2017; see also Erle and Topolinski 2017; Deroualle et al. 2015; Duran et al. 2011; see Online Resource 1 for task descriptions). The ease of self-simulation heuristic related to empathic responses when deliberate efforts were made to mentalize the target person and their circumstances, when the target person’s experience was ambiguous, or when a concurrent cognitive task made further mentalizing about the target person less likely (e. g., Buffone et al. 2017; Chambers and Davis 2012).

(4) What proportion of dispositional social perspective-taking is related to situational social perspective-taking? Dispositional social perspective-taking was positively related to situational social perspective-taking in 17 articles (e.g., Duran et al. 2011; Edwards et al. 2017; Erle and Topolinski 2015; Hepper et al. 2014; Mattan et al. 2016; Pfeifer et al. 2009; Yuan et al. 2017; see Online Resource 1 for the task description). Moreover, adults with high dispositional social perspective-taking and role-taking experience were better able to situational social perspective-taking than those with low dispositional perspective-taking and no role-taking experience (e.g., Church et al. 2015).

(5) What evidence is there to support the hypothesis of changes in dispositional or situational social perspective-taking? The reviewed studies suggest that dispositional (e.g., Gorgas et al. 2015; O’Brien et al. 2013) and situational social perspective-taking (e.g., Gehlbach et al. 2012c; Gehlbach et al. 2015; Lietz et al. 2011; Meyer and Lieberman 2016; Trötschel et al. 2011; Wald et al. 2017; Wolff 2006) are malleable, as its level can change after brief interventions.

Discussion

The actual evidence reviewed stems from heterogeneous research approaches published under the label social perspective-taking in the last 10 years. The consensus view is that perspective-taking is a cognitive capacity (Mead 1934; Piaget and Cook 1952) related to mentalizing that helps individuals to regulate their emotions (e.g., Engen and Singer 2012) and make appropriate responses in a social situation (Brown 1986; Fischer 1980; Lewis and Brooks-Gunn 1979). These relations are in accordance with the integrated framework depicted in Fig. 1.

We proposed a specific theoretical position for this manuscript when it comes to the definition of what we call social perspective-taking. Specifically, the inclusion of visuo-spatial perspective-taking into this construct is a current trend (e.g., Erle and Topolinski 2017). Relations between the different forms of perspective-taking have been disputed since decades. There are accordingly different approaches to the concept of perspective-taking. Early findings on egocentrism and perspective-taking in children already stimulated researchers to discuss different forms such as visuo-spatial and social perspective-taking (e.g., Burka and Glenwick 1978; Chandler 1973; Ford 1979; Light 1983; Morss 1987; Piaget and Inhelder 1956). For example, responses to the three-mountains task developed by Piaget and Inhelder (1956) may represent a young child’s rarely developed skill to see another angle of view visuo-spatially or socially (Chandler 1973; Morss 1987; Piaget and Cook 1952). Young children expect that others see the world just as they do until they begin to experience, in addition to that egocentric point of view, many other points of view (Burka and Glenwick 1978; Chandler 1973).

Researchers did not only describe more egocentrism and less perspectivism in young children but also in children and adults with a mental disorder (e.g., autism-spectrum disorder). Burka and Glenwick (1978, p. 62) summarized “since developmental delays in perspective-taking were prognostic of social difficulties in disordered populations, measurements of perspective-taking may also be predictive of social adjustment of normal children [or other human populations] as well.” Furthermore, Light (1983) highlighted that Piaget intended “perspective” to be taken in the visuo-spatially narrow sense and supposed to extend to interpersonally understand, for example, the other's feelings, thoughts, and motives (Light 1983). Adults who have normally developed this cognitive capacity are able to use social perspective-taking appropriately depending on situational requirements, as results from different conditions in experimental studies demonstrated (e.g., Chambers and Davis 2012). These findings are relevant for guiding teacher’s appropriate responses to students (Warren 2018).

Interestingly, the reviewed studies showed that moving into a position with a similar visuo-spatial perspective like a target person’s perspective may facilitate situational social perspective-taking compared to staying in front of that person (e.g., Deroualle et al. 2015; Santiesteban et al. 2017). Thus, frequent rotating oneself in a position that allows to see what the students see might facilitate lectures from the university teacher’s point of view.

The question with regard to factors which support or impair social perspective-taking can be answered as follows (see “States of oneself” and “Contextual conditions” in Fig. 1): Adults with lower self-reported distress and cortisol levels showed consistently higher levels dispositional social perspective-taking than those with lower levels of this disposition. The negative relationship between distress and dispositional social perspective-taking (e.g., Buffone et al. 2017; Engert et al. 2014) supports our initial assumption of adults’ social perspective-taking as a protective factor for health since teachers’ distress (e.g., Wolgast and Fischer 2017) and self-focusing (e.g., Bilz 2014) are frequently discussed. This relationship is especially important for developing intervention programs to improve teacher’s mental health and prevent their burnout.

Facilitated interpersonal interactions were related to both forms dispositional (e.g., Swartz and McElwain 2012) and situational social perspective-taking (e.g. Verhofstadt et al. 2016). Especially high levels of dispositional social perspective-taking positively related to high levels of the situational form (e.g., Pfeifer et al. 2009; Yuan et al. 2017). Only the gender differences, found when self-report measures were used (see “Characteristics of oneself” in Fig. 1), are not reflected in findings from research on situational social perspective-taking the last 10 years (e.g., Erle and Topolinski 2015; Mohr et al. 2010; Theodoridou et al. 2013). Visuo-spatial social perspective-taking was tested by objective measures in these studies. The comparable accuracy between females and males using objective measures extends findings from research using physiological measures or covert observation without finding gender differences (Eisenberg and Lennon 1983).

The results from reviewed studies suggest that if a familiar person is integrated into the observing participant’s self, the target-in-distress condition could activate imagine-self situational social perspective-taking (Buffone et al. 2017; Engert et al. 2014), as described by Batson et al. (1997).

Situational social perspective-taking appears to be a skill set rather than only one skill: (1) seeing a target person in real life, virtually, or mentally and imagining the viewpoint of the target individual; (2) mentalizing about the target’s social situation and recalling information about the target person if available.

Although a large body of evidence under the label social perspective-taking exists, we found some understudied points in our integrating framework (see Fig. 1). These are educational contextual conditions such as teachers’ situational social perspective-taking in school with regard to facilitating social interactions and bolster teacher-student relationships. So, we can only speculate that teachers who experience distress or difficult social interactions rather focus on students similar to themselves (Gehlbach et al. 2016) or focus on themselves (Bilz, 2014) than those with low levels of self-reported distress or experienced easy social interactions.

Limitations of this Systematic Review

An a priori limitation of the present systematic review was that it included only peer-reviewed theoretical contributions and articles presenting correlational or experimental studies. This limitation might reflect a tendency to publish mainstream research rather than novel or marginal approaches. One important limitation is the rather narrow definition of social perspective-taking and the timeframe for articles included in this review. The systematic review does not capture the perspective-taking literature exhaustively. It is rather a proof of concept for our theoretical conceptualization depicted in Fig. 1, not as an exhaustive summary of the perspective-taking literature.

Only a few studies provided clear information about both the initial sample size (N) and sample sizes for analyses (n). Therefore, it is hard to estimate whether data were censored. Moreover, some of the reviewed articles on dispositional social perspective-taking were inconsistent, as they cited social perspective-taking items from Davis (1983), which does not provide items. In fact, Davis published the items in 1980 and cited this previous work (Davis 1980) in 1983 without re-publishing the items. Furthermore, missing data were rarely reported even when large-scale survey designs were applied (e.g., O’Brien et al. 2013). Fewer than expected numbers of psychological studies in educational contexts could be included due to the ineligibility of the methods used or the study’s specific focus (e.g., the effect of autism on situational perspective-taking in children or adolescents) outside teaching at school or in higher education. Finally, we included the studies on emotional and cognitive dimensions of empathy. However, the use of empathy measures that did not clearly distinguish between the emotional vs. cognitive dimension was a further limitation of the systematic review. Accordingly, we recommend using situational social perspective-taking tasks (e.g., Erle and Topolinski 2015) combined with self-report measures that clearly differentiate between the emotional and cognitive dimensions of empathy in future research.

Implications for Future Research and Practice

The umbrella term social perspective-taking explicitly mentioned in published articles encompasses theoretically and methodologically heterogeneous research. We propose extending the conceptualization of social perspective-taking in adults as perspective coordination, in line with existing literature regarding children (e.g., Selman 1980) and with the present results from reviewed studies (e.g., Knowles 2014). The term perspective coordination serves to highlight skills involved in coordinating different perspectives with different degrees of similarity to one’s own (e.g., Chambers and Davis 2012), and thus reflects greater behavioral flexibility (e.g., Meyer and Lieberman 2016) than the narrower concept of situational taking another’s social perspective. Indeed, no person can fully and exclusively take the social perspective of another because she or he remains developmentally anchored to his/her own situational perspective (e.g., Deroualle et al. 2015; Epley et al. 2004). For example, under experimental conditions, a person can empathize with another person and understand what they are feeling, but all of this is experienced from the person’s own perspective that has not changed (e.g., Buffone et al. 2017; Chambers and Davis 2012).

In future studies, experimental conditions might be different teaching situations based on situations observed in reality which are simulated with virtual students in a virtual environment (e.g., cooperative learning groups who sit around tables vs. move around) and situational social perspective taking tasks. Student teachers’ dispositional social perspective-taking might be assessed as baseline before presenting the teaching situation and, subsequently, the situational social perspective-taking. The experimental design could be extended to interactions with virtual students. In this case, a teaching situation would be presented, situational social perspective-taking assessed, and the participant may respond to virtual students. Experimental studies on situational social perspective-taking linked to teachers’ emotion regulation in classes would give new insights into the underlying and related processes of this social cognitive skill set.

The reviewed studies did not apply longitudinal designs. Longitudinal studies across university or school teacher’s lifespan and more interventions with undergraduates in teacher education or teachers would give further insights into changes in their dispositional or situational social perspective-taking over time. The integrated framework in Fig 1 suggests interactions and indirect effects which may be tested using a longitudinal study design. For example, teacher’s characteristics may interact with their states. Appraisals may mediate the relationship between dispositional and situational social perspective-taking. The intervention program proposed by Meyer and Lieberman (2016) might be adapted to teachers.

Conclusion

The actual reviewed evidence explains intraindividual and interindividual differences in adult’s social perspective-taking. For example, low levels of distress related to high levels of dispositional or situational social perspective-taking. This relationship may protect adult’s health. Research in schools or higher education on the difference between the relationship of dispositional social perspective-taking (cognitive empathy) with low distress levels vs. emotional empathy with high distress levels would make it possible to identify resilient teachers and teachers at risk of burnout.

However, there is a clear need for research on the relationship of teachers’ dispositional and situational social perspective-taking with their students’ emotions or even learning outcomes. Such research might show whether teachers’ dispositional social perspective-taking makes a contribution to their situational social perspective-taking in class, teacher-student interactions, and learning in school, college, or university. Especially, visuo-spatial social perspective-taking of adults in educational contexts has rarely been investigated experimentally (Wolgast and Oyserman 2019). Thus, we can only speculate about which research findings might be valid for adults in educational contexts. A teacher who makes an attempt to see what a student sees probably makes assumptions about the target; thus, seeing what a student sees might help teachers mentalize a student’s steps to solving a task in school or higher education. Further research would help shed light on basic social cognitive processes in classes.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the systematic review (in the theoretical background, integrated heuristic, method and results)

*Agarwal, S. M., Shivakumar, V., Kalmady, S. V., Danivas, V., Amaresha, A. C., Bose, A., Narayanaswamy, J. C., Amorim, M. A., & Venkatasubramanian, G. (2017). Neural correlates of a perspective-taking task using in a realistic three-dimensional environment-based task: a pilot functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience, 15, 276–281. https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2017.15.3.276.

Ames, D. (2004a). Inside the mind-reader’s toolkit: projection and stereotyping in mental state inference. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 340–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.340.

Ames, D. (2004b). Strategies for social inference: a similarity contingency model of projection and stereotyping in attribute prevalence estimates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.573.

Ames, D. L., Jenkins, A. C., Banaji, M. R., & Mitchell, J. P. (2008). Taking another person’s perspective increases self-referential neural processing. Psychological Science, 19, 642–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02135.x.

Ames, D. R., Kammrath, L. K., Suppes, A., & Bolger, N. (2010). Not so fast: The (not-quite-complete) dissociation between accuracy and confidence in thin-slice impressions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 264–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209354519.

Amorim, M.-A. (2003). “What is my avatar seeing?”: the coordination of “out-of-body” and “embodied” perspectives for scene recognition across views. Visual Cognition, 10, 157–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/713756678.

Aron, A. U., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 596–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596.

Arzy, S., Thut, G., Mohr, C., Michel, C. M., & Blanke, O. (2006). Neural basis of embodiment: distinct contributions of temporoparietal junction and extrastriate body area. Journal of Neuroscience, 26, 8074–8081. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0745-06.2006.

*Bach, R. A., Defever, A. M., Chopik, W. J., & Konrath, S. H. (2017). Geographic variation in empathy: a state-level analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 68, 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.12.007.

*Barber, S. J., Franklin, N., Naka, M., & Yoshimura, H. (2010). Higher social intelligence can impair source memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36, 545–551. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018406

*Bardi, L., Gheza, D., & Brass, M. (2017). TPJ-M1 interaction in the control of shared representations: new insights from tDCS and TMS combined. NeuroImage, 146, 734–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.10.050.

Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2004). The empathy quotient: an investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000022607.19833.00.

Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a ‘theory of mind’? Cognition, 21, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8.

*Barr, J. J. (2011). The relationship between teachers’ empathy and perceptions of school culture. Educational Studies, 37, 365–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2010.506342.

Batson, C. D., Dyck, J. L., Brandt, J. R., Batson, J. G., Powell, A. L., McMaster, M. R., & Griffitt, C. (1988). Five studies testing two new egoistic alternatives to the empathy-altruism hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 52–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.55.1.52.

Batson, C. D., Batson, J. G., Slingsby, J. K., Harrell, K. L., Peekna, H. M., & Todd, R. M. (1991). Empathic joy and the empathy-altruism hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.3.413.

Batson, C. D., Early, S., & Salvarani, G. (1997). Perspective taking: imagining how another feels versus imagining how you would feel. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 751–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297237008.

Batson, C. D., Lishner, D. A., Carpenter, A., Dulin, L., Harjusola-Webb, S., Stocks, E. L., et al. (2003). “… As you would have them do unto you”: does imagining yourself in the other’s place stimulate moral action? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1190–1201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203254600.

*Beussink, C. N., Hackney, A. A., & Vitacco, M. J. (2017). The effects of perspective taking on empathy-related responses for college students higher in callous traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.005.

Bilz, L. (2014). Are symptoms of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents overlooked in schools? Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 28, 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652/a000118.

Bloom, P., & German, T. P. (2000). Two reasons to abandon the false belief task as a test of theory of mind. Cognition, 77, B25–B31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(00)00096-2.

*Böffel, C., & Müsseler, J. (2018). Perceived ownership of avatars influences visual perspective taking. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00743.

Borkenau, P., & Tandler, N. (2015). Personality, trait models of. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Vol. 17, 2nd ed., pp. 920–924). Oxford: Elsevier.

*Bostic, T. B. (2014). Teacher empathy and its relationship to the standardized test scores of diverse secondary English students. Journal of Research in Education, 24, 3–16.

Brown, G. (1986). Case, R. (1985). Intellectual development: birth to adulthood. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 56, 220–222 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1986.tb02666.x/abstract. Retrieved on December 3, 2019

*Buffone, A. E. K., Poulin, M., DeLury, S., Ministero, L., Morrisson, C., & Scalco, M. (2017). Don’t walk in her shoes! Different forms of perspective taking affect stress physiology. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 72, 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.04.001.

Bukowski, H. B., & Samson, D. (2015). Can emotions affect level 1 visual perspective-taking? Cognitive Neuroscience, 7, 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/17588928.2015.1043879.

Burka, A. A., & Glenwick, D. S. (1978). Egocentrism and classroom adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 6, 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00915782.

*Chambers, J. R., & Davis, M. H. (2012). The role of the self in perspective taking and empathy: ease of self-simulation as a heuristic for inferring empathic feelings. Social Cognition, 30, 153–180. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2012.30.2.153.

Chandler, M. J. (1973). The picture arrangement subtest of the WAIS as an index of social egocentrism: a comparative study of normal and emotionally disturbed children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 1, 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00917632.

*Church, B. K., Peytcheva, M., Yu, W., & Singtokul, O.-A. (2015). Perspective taking in auditor-manager interactions: an experimental investigation of auditor behavior. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 45, 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2015.07.001.

Converse, B. A., Lin, S., Keysar, B., & Epley, N. (2008). In the mood to get over yourself: mood affects theory-of-mind use. Emotion, 8, 725–730. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013282.

Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85–94 https://www.uv.es/friasnav/Davis_1980.pdf. Retrieved on December 3, 2019

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multi-dimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113.

Davis, M. H. (2018). Empathy: a social psychological approach. Routledge.

De Corte, K., Buysse, A., Verhofstadt, L., Roeyers, H., Ponnet, K., & Davis, M. H. (2007). Measuring empathic tendencies: reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Psychologica Belgica, 47, 235–260. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-47-4-235.

*Deliens, G., Bukowski, H., Slama, H., Surtees, A., Cleeremans, A., Samson, D., & Peigneux, P. (2018). The impact of sleep deprivation on visual perspective taking. Journal of Sleep Research, 27, 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12595.

Derksen, D. G., Hunsche, M. C., Giroux, M. E., Connolly, D. A., & Bernstein, D. M. (2018). A systematic review of theory of mind’s precursors and functions across the lifespan. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 226, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000325.

*Deroualle, D., Borel, L., Devèze, A., & Lopez, C. (2015). Changing perspective: the role of vestibular signals. Neuropsychologia, 79, 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.08.022.

*Diehl, C., Glaser, T., & Bohner, G. (2014). Face the consequences: learning about victim’s suffering reduces sexual harassment myth acceptance and men’s likelihood to sexually harass. Aggressive Behavior, 40, 489–503. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21553.

*Dugan, J. P., Bohle, C. W., Woelker, L. R., & Cooney, M. A. (2014). The role of social perspective-taking in developing students’ leadership capacities. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 51, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1515/jsarp-2014-0001.

*Dugan, J. P., Turman, N. T., & Torrez, M. A. (2015). When recreation is more than just sport: advancing the leadership development of students in intramurals and club sports. Recreational Sports Journal, 39, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1123/rsj.2015-0008.

*Duran, N. D., & Dale, R. (2014). Perspective-taking in dialogue as self-organization under social constraints. New Ideas in Psychology, 32, 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2013.03.004.

*Duran, N. D., Dale, R., & Kreuz, R. J. (2011). Listeners invest in an assumed other’s perspective despite cognitive cost. Cognition, 121, 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2011.06.009.

Dziobek, I., Rogers, K., Fleck, S., Bahnemann, M., Heekeren, H. R., Wolf, O. T., & Convit, A. (2008). Dissociation of cognitive and emotional empathy in adults with Asperger syndrome using the Multifaceted Empathy Test (MET). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 464–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0486-x.

*Edwards, R., Bybee, B. T., Frost, J. K., Harvey, A. J., & Navarro, M. (2017). That’s not what I meant: how misunderstanding is related to channel and perspective-taking. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 36, 188–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X16662968.

Eisenberg, N., & Lennon, R. (1983). Sex differences in empathy and related capacities. Psychological Bulletin, 94, 100–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.94.1.100.

*Engen, H. G., & Singer, T. (2012). Empathy circuits. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 23, 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2012.11.003.

*Engert, V., Plessow, F., Miller, R., Kirschbaum, C., & Singer, T. (2014). Cortisol increase in empathic stress is modulated by emotional closeness and observation modality. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 45, 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.04.005.

Epley, N., Keysar, B., van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2004). Perspective taking as egocentric anchoring and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 327–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.327.

Epley, N., Caruso, E. M., & Bazerman, M. H. (2006). When perspective taking increases taking: reactive egoism in social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 872–889 [no doi available].

*Erle, T. M., & Topolinski, S. (2015). Spatial and empathic perspective-taking correlate on a self-reported level. Social Cognition, 33, 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2015.33.3.187.

*Erle, T. M., & Topolinski, S. (2017). The grounded nature of psychological perspective-taking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112, 683–695. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000081.

Eyal, T., Steffel, M., & Epley, N. (2018). Perspective mistaking: accurately understanding the mind of another requires getting perspective, not taking perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114, 547–571. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000115.

Fischer, K. W. (1980). A theory of cognitive development: the control and construction of hierarchies of skills. Psychological Review, 87, 477–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.87.6.477.

Fleeson, W. (2004). Moving personality beyond the person-situation debate: the challenge and the opportunity of within-person variability. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00280.x.

Ford, M. E. (1979). The construct validity of egocentrism. Psychological Bulletin, 86, 1169–1188. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.6.1169.

Galinsky, A. D., & Moskowitz, G. B. (2000). Perspective-taking: decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.708.

Galinsky, A. D., & Mussweiler, T. (2001). First offers as anchors: the role of perspective-taking and negotiator focus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 657–669. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.657.

Galinsky, A. D., Ku, G., & Wang, C. S. (2005). Perspective-taking: fostering social bonds and facilitating social coordination. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 8, 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430205051060.

Galinsky, A. D., Maddux, W. W., Gilin, D., & White, J. B. (2008). Why it pays to get inside the head of your opponent: the differential effects of perspective taking and empathy in negotiations. Psychological Science, 19, 378–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02096.x.

Gehlbach, H. (2004). A new perspective on perspective taking: a multidimensional approach to conceptualizing an aptitude. Educational Psychology Review, 16, 207–234. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034021.12899.11.

Gehlbach, H., Brown, S. W., Ioannou, A., Boyer, M. A., Hudson, N., Niv-Solomon, A., . . . Janik, L. (2008). Increasing interest in social studies: Social perspective taking and selfefficacy in stimulating simulations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33(4), 894–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2007.11.002

*Gehlbach, H. (2010). The social side of school: why teachers need social psychology. Educational Psychology Review, 22, 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9138-3.

*Gehlbach, H. (2011). Making social studies social: engaging students through different forms of social perspective taking. Theory Into Practice, 50, 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2011.607394.

Gehlbach, H., & Brinkworth, M. E. (2012). The social perspective taking process: strategies and sources of evidence in taking another’s perspective. Teachers College Record, 114, 226–254 http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11393842. Retrieved on December 3, 2019

Gehlbach, H., & Robinson, C. D. (2018). Mitigating illusory results through preregistration in education. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 11, 296–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2017.1387950.

Gehlbach, H., & Vriesema, C. C. (2019). Meta-bias: a practical theory of motivated thinking. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-018-9454-6.

Gehlbach, H., Brinkworth, M. E., & Wang, M.-T. (2012a). The social perspective taking process: what motivates individuals to take another’s perspective? Teachers College Record, 114, 197–225 http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11393841. Retrieved on December 3, 2019

*Gehlbach, H., Brinkworth, M. E., & Harris, A. D. (2012b). Changes in teacher–student relationships. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 690–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02058.x.

*Gehlbach, H., Young, L. V., & Roan, L. K. (2012c). Teaching social perspective taking: how educators might learn from the Army. Educational Psychology, 32, 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2011.652807.

*Gehlbach, H., Marietta, G., King, A. M., Karutz, C., Bailenson, J. N., & Dede, C. (2015). Many ways to walk a mile in another’s moccasins: type of social perspective taking and its effect on negotiation outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.035.

Gehlbach, H., Brinkworth, M. E., King, A. M., Hsu, L. M., McIntyre, J., & Rogers, T. (2016). Creating birds of similar feathers: leveraging similarity to improve teacher–student relationships and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108, 342–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000042.

German, T. P., & Hehman, J. A. (2006). Representational and executive selection resources in ‘theory of mind’: evidence from compromised belief-desire reasoning in old age. Cognition, 101, 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2005.05.006.

*Gilin, D., Maddux, W. W., Carpenter, J., & Galinsky, A. D. (2012). When to use your head and when to use your heart: the differential value of perspective-taking versus empathy in competitive interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212465320.

*Gorgas, D. L., Greenberger, S., Bahner, D. P., & Way, D. P. (2015). Teaching emotional intelligence: a control group study of a brief educational intervention for emergency medicine residents. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 16, 899–906. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2015.8.27304.

Hass, R. G. (1984). Perspective taking and self-awareness: drawing an E on your forehead. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 788–798. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.788.

Hawk, S. T., Keijsers, L., Branje, S. J. T., van der Graaff, J., de Wied, M., & Meeus, W. (2013). Examining the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) among early and late adolescents and their mothers. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95, 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2012.696080.

Hegarty, M., & Waller, D. (2004). A dissociation between mental rotation and perspective-taking spatial abilities. Intelligence, 32, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2003.12.001.

*Hepper, E. G., Hart, C. M., & Sedikides, C. (2014). Moving narcissus: can narcissists be empathic? Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 1079–1091. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214535812.

*Ingraham, C. L. (2017). Educating consultants for multicultural practice of consultee-centered consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 27, 72–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2016.1174936.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2005). New developments in social interdependence theory. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 131(4), 285–358.

*Kajonius, P. J., & Dåderman, A. M. (2017). Conceptualizations of personality disorders with the five factor model-count and empathy traits. International Journal of Testing, 17, 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/15305058.2017.1279164.

Kessler, K., & Rutherford, H. (2010). The two forms of visuo-spatial perspective taking are differently embodied and subserve different spatial prepositions. Frontiers in Psychology, 1, 213. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00213.

Kessler, K., & Thomson, L. A. (2010). The embodied nature of spatial perspective taking: embodied transformation versus sensorimotor interference. Cognition, 114, 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2009.08.015.

Keysar, B. (1994). The illusory transparency of intention: linguistic perspective taking in text. Cognitive Psychology, 23, 165–208. https://doi.org/10.1006/cogp.1994.1006.

*Knowles, M. L. (2014). Social rejection increases perspective taking. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.06.008.

*Konrath, S., O'Brien, E., & Hsing, C. (2011). Changes in self-reported empathy in American college students over time: a meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377395.

*Kordts-Freudinger, R. (2017). Feel, think, teach—emotional underpinnings of approaches to teaching in higher education. International Journal of Higher Education, 6, 217–229. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n1p217.

Lamm, C., Batson, C. D., & Decety, J. (2007). The neural substrate of human empathy: effects of perspective-taking and cognitive appraisal. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2007.19.1.42.

*Lamm, C., Decety, J., & Singer, T. (2011). Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. Neuroimage, 54, 2492–2502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.014.

Leibetseder, M., Laireiter, A., Riepler, A., & Köller, T. (2001). E-Skala: Fragebogen zur Erfassung von Empathie—Beschreibung und psychometrische Eigenschaften. Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie, 22, 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1024//0170-1789.22.1.70.

Levin, I. P., Huneke, M. E., & Jasper, J. D. (2000). Information processing at successive stages of decision making: need for cognition and inclusion-exclusion effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82, 171–193. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2000.2881.

Lewis, M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1979). Toward a theory of social cognition: the development of self. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 4, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.23219790403.

*Libby, L. K., & Eibach, R. P. (2011). Visual perspective in mental imagery. In M. P. Zanna & J. M. Olson (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology: v.44. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (1st ed., Vol. 44, pp. 185–245). s.l.: Elsevier textbooks. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385522-0.00004-4.

Lietz, C. A., Gerdes, K. E., Sun, F., Geiger, J. M., Wagaman, M. A., & Segal, E. A. (2011). The Empathy Assessment Index (EAI): a confirmatory factor analysis of a multidimensional model of empathy. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 2, 104–124. https://doi.org/10.5243/jsswr.2011.6.

Light, P. (1983). Piaget and egocentrism: a perspective on recent developmental research. Early Child Development and Care, 12, 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443830120102.

Lillard, A. (1998). Ethopsychologies: cultural variations in theories of mind? Psychological Bulletin, 123, 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.123.1.3.

Mattan, B. D., Quinn, K. A., Apperly, I. A., Sui, J., & Rotshtein, P. (2015). Is it always me first? Effects of self-tagging on third-person perspective-taking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 41, 1,100–1,117. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000078.

*Mattan, B. D., Rotshtein, P., & Quinn, K. A. (2016). Empathy and visual perspective-taking performance. Cognitive Neuroscience, 7, 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/17588928.2015.1085372.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society (Vol. 111). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

*Meyer, M. L., & Lieberman, M. D. (2016). Social working memory training improves perspective-taking accuracy. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7, 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615624143.

Milligan, K., Astington, J. W., & Dack, L. A. (2007). Language and theory of mind: meta-analysis of the relation between language ability and false-belief understanding. Child Development, 2, 622–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01018.x.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

*Mohr, C., Rowe, A. C., & Blanke, O. (2010). The influence of sex and empathy on putting oneself in the shoes of others. British Journal of Psychology, 101, 277–291. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712609X457450.

*Mohr, C., Rowe, A. C., Kurokawa, I., Dendy, L., & Theodoridou, A. (2013). Bodily perspective taking goes social: the role of personal, interpersonal, and intercultural factors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43, 1,369–1,381. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12093.

*Mooradian, T. A., Davis, M. H., & Matzler, K. (2011). Self-reported empathy and the hierarchical structure of personality. The American Journal of Psychology, 124, 99–109. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.124.1.0099.

*Morey, J. T., & Dansereau, D. F. (2010). Decision-making strategies for college students. Journal of College Counseling, 13, 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2010.tb00056.x.

Morss, J. R. (1987). The construction of perspectives: Piaget’s alternative to spatial egocentrism. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 10, 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/016502548701000301.

*Nielsen, M. K., Slade, L., Levy, J. P., & Holmes, A. (2015). Inclined to see it your way: do altercentric intrusion effects in visual perspective taking reflect an intrinsically social process? The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 68, 1931–1951. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2015.1023206.

*O’Brien, E., Konrath, S. H., Grühn, D., & Hagen, A. L. (2013). Empathic concern and perspective taking: linear and quadratic effects of age across the adult life span. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs055.

Pasch, L. A., & Bradbury, T. N. (1998). Social support, conflict, and the development of marital dysfunction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.66.2.219.

Paulus, C. (2009). Der Saarbrücker Persönlichkeitsfragebogen SPF (IRI) zur Messung von Empathie: Psychometrische Evaluation der deutschen Version des Interpersonal Reactivity Index. http://psydok.sulb.uni-saarland.de/volltexte/2009/2363/pdf/SPF_Artikel.pdf. Retrieved on December 3, 2019

*Pavey, L., Greitemeyer, T., & Sparks, P. (2012). “I help because I want to, not because you tell me to”: empathy increases autonomously motivated helping. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211435940.

*Pfeifer, J. H., Masten, C. L., Borofsky, L. A., Dapretto, M., Fuligni, A. J., & Lieberman, M. D. (2009). Neural correlates of direct and reflected self-appraisals in adolescents and adults: when social perspective-taking informs self-perception. Child Development, 80, 1,016–1,038. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01314.x.

Piaget, J., & Cook, M. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children (Vol. 8, No. 5, p. 18). New York: International Universities Press.

Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1956). The child’s conception of space. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Pierce, J. R., Kilduff, G. J., Galinsky, A. D., & Sivanathan, N. (2013). From glue to gasoline: how competition turns perspective takers unethical. Psychological Science, 24, 1986–1994. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613482144.

Rao, P. A., Beidel, D. C., & Murray, M. J. (first online 2007; 2008). Social skills interventions for children with Asperger’s syndrome or high-functioning autism: a review and recommendations. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0402-4.

Reniers, R. L. E. P., Corcoran, R., Drake, R., Shryane, N. M., & Völlm, B. A. (2011). The QCAE: a questionnaire of cognitive and affective empathy. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93, 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.528484.

Roberts, B. W., Luo, J., Briley, D. A., Chow, P. I., Su, R., & Hill, P. L. (2017). A systematic review of personality trait change through intervention. Psychological Bulletin, 143, 117–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000088.

Rosset, E. (2008). It’s no accident: our bias for intentional explanations. Cognition, 108, 771–780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2008.07.001.

Ruby, P., & Decety, J. (2003). What you believe versus what you think they believe: a neuroimaging study of conceptual perspective‐taking. European Journal of Neuroscience, 17(11), 2475-2480. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02673.x

Samson, D., Apperly, I. A., Braithwaite, J. J., Andrews, B. J., & Bodley Scott, S. E. (2010). Seeing it their way: Evidence for rapid and involuntary computation of what other people see. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 36, 1, 255–1,266. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018729

*Santiesteban, I., Kaur, S., Bird, G., & Catmur, C. (2017). Attentional processes, not implicit mentalizing, mediate performance in a perspective-taking task: evidence from stimulation of the temporoparietal junction. NeuroImage, 155, 305–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.04.055.

*Sassenrath, C., Sassenberg, K., & Scholl, A. (2014). From a distance …: the impact of approach and avoidance motivational orientation on perspective taking. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5, 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550613486672.

Sassenrath, C., Hodges, S. D., & Pfattheicher, S. (2016). It’s all about the self: When perspective taking backfires. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(6), 405-410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416659253

Schaafsma, S. M., Pfaff, D. W., Spunt, R. P., & Adolphs, R. (2015). Deconstructing and reconstructing theory of mind. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(2),65-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.11.007

Schneider, D., Bayliss, A. P., Becker, S. I., & Dux, P. E. (2012). Eye movements reveal sustained implicit processing of others’ mental states. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 14, 433–438. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025458.

Schober, M. F. (1993). Spatial perspective-taking in conversation. Cognition, 47, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(93)90060-9.

*Seinfeld, S., Arroyo-Palacios, J., Iruretagoyena, G., Hortensius, R., Zapata, L. E., Borland, D., de Gelder, B., Slater, M., & Sanchez-Vives, M. V. (2018). Offenders become the victim in virtual reality: impact of changing perspective in domestic violence. Scientific Reports, 8, 2692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19987-7.

Selman, R. L. (1980). The growth of interpersonal understanding—developmental and clinical analyses. New York: Academic Press.