Abstract

Belonging is an essential aspect of psychological functioning. Schools offer unique opportunities to improve belonging for school-aged children. Research on school belonging, however, has been fragmented and diluted by inconsistency in the use of terminology. To resolve some of these inconsistencies, the current study uses meta-analysis of individual and social level factors that influence school belonging. These findings aim to provide guidance on the factors schools should emphasise to best support students. First, a systematic review identified 10 themes that influence school belonging at the student level during adolescence in educational settings (academic motivation, emotional stability, personal characteristics, parent support, peer support, teacher support, gender, race and ethnicity, extracurricular activities and environmental/school safety). Second, the average association between each of these themes and school belonging was meta-analytically examined across 51 studies (N = 67,378). Teacher support and positive personal characteristics were the strongest predictors of school belonging. Results varied by geographic location, with effects generally stronger in rural than in urban locations. The findings may be useful in improving perceptions of school belonging for secondary students through the design of policy, pedagogy and teacher training, by encouraging school leaders and educators to build qualities within the students and change school systems and processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

School belonging in educational settings is positively related to good academic performance (Sari 2012), prosocial behaviours (Demanet and Van Houtte 2012; Lonczak et al. 2002), psychological well-being (Jose et al. 2012) and other positive variables. However, there appears to be a gap between understanding the importance of this construct from research and how it is transferred into day-to-day practice within schools (Allen and Bowles 2013; Collaborative for Academic Social and Emotional Learning 2003). This research-practice gap may in part stem from inconsistencies across studies that make it unclear for schools as to what helps or hinders a sense of belonging for students. The current study meta-analytically examines individual and social level factors that relate to school belonging, providing guidance for understanding the factors that schools might emphasise to best support students.

Defining School Belonging

School belonging has been described in using various terminology, including school bonding, attachment, engagement, connectedness and community (e.g. Barber and Schluterman 2008; Brown and Evans 2002; Goodenow and Grady 1993; Hawkins and Weis 1985; Libbey 2004; McNeely et al. 2002; Moody and Bearman 2004; O’Brennan and Furlong 2010; Townsend and McWhirter 2005). It has most consistently been defined as “the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school social environment” (Goodenow and Grady 1993, p. 80). This definition emphasises the multiple features of school belonging for students, as well as the broader socio-ecological context of peers, students, and teachers within the school environment. The various terms and definitions tend to share three similar operational aspects: (1) school-based relationships and experiences, (2) student-teacher relationships and (3) and students’ general feelings about school as a whole.

The Benefits of School Belonging

Research studies generally support the benefits of school belonging for both academic and psychosocial outcomes. For example, Pittman and Richmond (2007) found that a perceived sense of belonging was an important variable related to academic adjustment (e.g. grades and competence). Similarly, in a cohort of 572 young people, Gillen-O’Neel and Fuligni (2013) found that school belonging was positively associated with a higher level of academic motivation across a 4-year period. Evidence indicates that belongingness correlates with less absenteeism, better school completion, less truancy and less school misconduct (Connell et al. 1995; Croninger and Lee 2001; Demanet and Van Houtte 2012; Hallinan 2008), as well as more positive attitudes towards learning and academic self-efficacy (Battistich et al. 1995; Roeser et al. 1996).

In relation to psychosocial outcomes, school belonging has been associated with higher levels of happiness, psychological functioning, adjustment, self-esteem and self-identity (e.g. Jose et al. 2012; Law et al. 2013; Nutbrown and Clough 2009; O’Rourke and Cooper 2010), and is inversely related to incidents of fighting, bullying and vandalism, disruptive behaviour and emotional distress, risk-taking behaviours such as substance and tobacco use, and early sexualisation (e.g. Goodenow 1993; Lonczak et al. 2002; Samdal et al. 1998; Wilson and Elliott 2003).

While a sense of belonging is important for children of all ages (Quinn and Oldmeadow 2013), it may be particularly relevant to the unique and specific needs and challenges of adolescents (age 12–18) compared with other developmental stages. Adolescence is a period of identity formation, shifting social relationships, priorities and expectations, and the need to navigate the transition from childhood to adulthood (Erikson 1968; Steinberg and Morris 2001).

Identity formation is a central feature of the normative developmental trajectory of adolescence to adulthood (Hill et al. 2013), likely due to emotional maturity and the need to make considered choices regarding future directions (Allen et al. 2014). Young people tend to spend more time with peers than adults, and friendships play a key role in one’s identity and the development of social supports (Quinn and Oldmeadow 2013; Steinberg and Morris 2001). School belonging correlates with the formation of a positive identity (Brechwald and Prinstein 2011; Davis 2012).

A sense of belonging has been found to also facilitate transition into adulthood (Tanti et al. 2011) and is particularly important in middle adolescence where disconnection from schools and peers has frequently been reported (O’Brennan and Furlong 2010). Negative experiences related to a sense of belonging during adolescence can have a profound effect on psychosocial adjustment (Allen et al. 2014), whereas a sense of belonging can aid successful psychosocial adjustment (Lonczak et al. 2002; Nutbrown and Clough 2009; Sari 2012). For example, early onset of puberty may lead to a lack of assimilation with peers and psychosocial maladjustment (Mensah et al. 2013). In the Australian Temperament Project, how students felt about their school significantly related to social competence, life satisfaction, trusting others in the community, trust in authority and taking on civic responsibilities (O’Connor et al. 2010).

A Framework for Understanding School Belonging

Despite the benefits of school belonging, not belonging to school is a concern for many students across the globe (Allen and Bowles 2013; CASEL 2003; Hirschkorn and Geelan 2008). For instance, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) demonstrated that as of 2003, across 42 countries, 8354 schools and 224,058 15-year-olds, student disaffection with school ranged from 17 to 40 % (Willms 2003). On average, one in four adolescents were categorised as having low feelings of belongingness and about one in five reported low levels of academic engagement.

Schools play an important role in building groups and social networks for students and offer unique opportunities for students to develop a sense of belonging (Allen and Bowles 2013). Yet, there are considerable discrepancies in terminology and no clear frameworks that schools can follow (Libbey 2004), thus leaving schools with little guidance as to the best ways to support school belonging. A clear framework that captures the complexities of schools is needed.

From a theoretical perspective, a variety of motivational relational, sociological and socio-ecological approaches can be applied to the concept of belonging, including Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow 1968), parental involvement (Epstein 1992), attachment theory (Bowlby 1973; Cohen 1985), social capital (Putnam 2000), self-presentation (Fiske 2004) and socio-ecological themes (Bronfenbrenner 1994). Within the secondary school environment, Bronfenbrenner’s (1994) bioecological model of human development provides a framework to capture both the biological and dispositional aspects of the developing adolescent with the complex contextual features of the students’ environment. According to this framework, the adolescent is part of a broader system, which interacts with the young person’s nature to impact their development and psychosocial adjustment. Accordingly, school belonging is not simply a phenomenon that exists within the individual, but is also affected by peers, families and teachers (i.e. the microsystem); the school’s social and organisational culture and interactions with parents (i.e. the mesosystem); linkages across multiple micro- and mesosytems (i.e. the exosystem); broader policies, norms and cultural values (the macrosystem); and temporal aspects (the chronosystem). This review is organised around some aspects within these levels.

Individual Factors

At the individual level, a considerable amount of literature focuses on personal characteristics, such as motivation, personality, optimism, self-efficacy, self-esteem, sociability and social skills (e.g. Connell and Wellborn 1991; Samdal et al. 1998; Sirin and Rogers-Sirin 2004; Uwah et al. 2008). While numerous biopsychosocial aspects could be included, the review here focuses on four areas that have been identified as particularly relevant to school belonging: academic motivation, positive personal characteristics, negative personal aspects and demographic factors.

Academic motivation is defined as the expectancy of academic success through goal setting and future aspirations. It is concerned with the “extent to which students are motivated to learn and do well in school” (Libbey 2004, p. 278). According to self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan and Deci 2000), motivation includes both cognitions (such as goals and having agency to meet those goals) and behaviours (such as performance and achieving goals). From this perspective, academic motivation includes both cognitions about academics as well as actual participation and performance (e.g. Anderman 2002; Benner et al. 2008; Bonny et al. 2000; Goodenow and Grady 1993). It also includes perceived instrumentality, academic self-regulation, academic confidence, participation, motivation and performance.

Personal characteristics refer to positive and negative aspects of a student, including their personal qualities, attributes, abilities, temperament and nature. Studies suggest that positive characteristics such as self-efficacy, conscientiousness, coping skills (e.g. seeking social support, self-reliance, problem solving), positive affect, hope, school adjustment (e.g. making friends, staying out of trouble, getting along with teachers and students) and relatedness support a sense of school belonging (e.g. Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2006).

Negative personal factors such as anxiety, depression and suicide ideation are linked with a low sense of school belonging (e.g. McMahon et al. 2008; Moody and Bearman 2004; Shochet et al. 2007). Negative factors include maladaptive coping skills, psychoticism, depressive symptoms, fear of failure, negative affect (e.g. sad, gloomy, nervous, lonely, ashamed, frightened) and accumulated stress. Studies suggest a clear link between mental illness and low levels of social belonging (e.g. Shochet et al. 2011).

Demographic characteristics such as one’s gender (male versus female) and race and ethnicity (how one may identify themselves based on social, cultural or historical factors) have also been found to contribute to a sense of school belonging (Bonny et al. 2000; Ma 2003; Read et al. 2003; Sanchez et al. 2005). Age also may matter; to reduce the impact of potential developmental changes that might occur through the transition from childhood into adulthood, this review limits its focus to the secondary schooling years, to some extent controlling the potential influence of this aspect.

Micro Level Factors

The current review includes three micro factors: parent, peer and teacher support, which studies suggest are strongly linked to one’s sense of school belonging (e.g. Anderman 2003; Brewster and Bowen 2004; Garcia-Reid 2007; Goodenow and Grady 1993; Hamm and Faircloth 2005; Hattie 2009; Johnson 2009; Osterman 2000; Reschly et al. 2008; Sakiz 2012; Wang and Eccles 2012). Qualities such as teacher supportiveness and caring, presence of good friends, engagement in academic progress and academic and social support from peers and parents are all important contributors to a sense of belonging (Libbey 2004; Osterman 2000).

Parent support refers to the ability for parents or other caregivers to provide academic support as well as social support, open communication and supportive behaviour (e.g. giving encouragement, gratitude). It includes the ability to show care and compassion. Parental relationships are the first form of support a child typically receives, and although the parent-child relationship shifts through adolescence, having a supportive parent can provide a young person with a sense of safety and acceptance (e.g. Anderman 2003).

Throughout adolescence, young people increasingly look to peers for acceptance and connection. Peer support refers to trust and closeness with friends and peers. Unsupportive peers can be a source of stress and social anxiety (Wang and Eccles 2012), whereas supportive peers offer social as well as academic encouragement and can foster a sense of care and acceptance (Hamm and Faircloth 2005; Reschly et al. 2008).

Teacher support refers to teachers who promote mutual respect, care, encouragement, friendliness, fairness and autonomy. It is present when teachers are perceived as likeable, when they praise good behaviour and work and are available for personal and academic support. Supportive teachers expect students to do their best, and scaffold learning to help the student achieve. Teacher support is felt when students feel a sense of connection with their teacher.

Meso Level Factors

Schools create a climate that may be more or less supportive of student belonging. School belonging relates to the number of group memberships (Drolet and Arcand 2013) and number of extracurricular activities (i.e. activities that fall outside of the standard school curriculum, including sports teams, clubs, leadership positions, band/orchestra, etc.) to which a student is involved in (Dotterer et al. 2007; Libbey 2004). Little is understood and known about environmental features more broadly as a school level influencer of school belonging, but the school environment clearly matters (e.g. Chan 2008; Loukas et al. 2010; Osterman 2000; Waters et al. 2010). In fact, the similar relational characteristics that are used to describe school belonging are also found in definitions of school community (e.g. feeling cared for, supported and emotionally connected). School structures and policies impact a sense of fairness, and the setting itself relates to how safe and secure a student may feel at school (CDC 2009). Research investigating the school environment, therefore, has mostly focused on discipline procedures, fairness and safety policies (Anderman 2002; Brutsaert and Van Houtte 2002; Ma 2003).

Exo, Macro and Chrono Level Factors

Research on school belonging has focused primarily on individual and interpersonal factors, but broader aspects of the culture and period in time impact decisions and experiences at lower levels (Allen et al. 2016). It can be difficult to examine these systems, as they often cost considerable time and resources (Brown Kirschman and Karazsia 2014). The current review takes advantage of studies that occur in different temporal and spatial locations to approximate three macro and chrono level factors: country of study (representing the overall culture in which schools reside), urban or rural location (representing sub-cultures within a given culture) and year of study (representing different cohorts and histories points in time). Few studies have considered exosystem aspects, and thus, this level is excluded here.

A Note on Causation

While numerous themes have been linked to school belonging, it is important to note that the causal direction of associations is unclear. A bivariate association between these themes and school belonging is often tested, and while authors might claim a direction, the study designs do not allow causality to be determined. For instance, a student’s level of academic motivation may both stem from feeling a sense of belonging and also influence the extent to which the student belongs (Anderman 2003; Goodenow and Grady 1993; Ryzin et al. 2009; Whitlock 2006). While the variables described in this paper could be antecedents or consequences, have a reciprocal relationship or interact with school belonging, the literature suggests that the themes are linked with school belonging and therefore are important to consider.

The Current Study

Despite these different individual, relational and environmental factors being identified as relating to belongingness, the extent to which each one helps or hinders school belonging is unknown. Two reviews of relevant factors (CDC 2009; Wingspread Declaration 2004) have previously provided summaries and discourse on the topic. In 2003, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Division of Adolescent and School Health and the Johnson Foundation convened an international gathering of educational leaders and researchers in the USA to determine guidelines for improving school belonging. Identified strategies included providing academic support to students; applying fair and consistent disciplinary policies; creating trusting relationships amongst students, teachers and staff members; hiring and supporting capable teachers; fostering high family expectations for school performance and completion; and ensuring that every student feels close to at least one supportive adult at school (Wingspread Declaration on School Connections 2004). Building upon this work, the CDC (2009) conceptualised four factors that foster belonging in a school setting: support by school staff and other adult, positive peer groups, commitment to education and the physical environment and psychosocial climate of the school environment.

Although providing some guidance, these two reviews were narrative-based and, as such, were unable to quantify the individual effects of individual and group variables on school belonging, and clearly more research is needed in this area. The current meta-analytic review quantitatively combines effect sizes across studies to determine average associations between different factors and school belonging, as well as identifies moderators of these associations. The review is organised around 10 themes falling across multiple levels of the bioecological framework: factors relevant to the individual (academic motivation, positive and negative personal characteristics, gender, race/ethnicity), microsystem (parent, peer and teacher support) and mesosystem (extracurricular opportunities, school environment) levels. In addition, several factors that were consistently available across studies were included as possible moderators (publication, country, geographic location of school). These study characteristics could be conceived as macro system (i.e. country and school location) and chronosystem (year) variables. Thus, this paper examines:

-

1.

To what extent do each of the 10 identified themes relate to school belonging?

-

2.

Do publication year, country and geographic location moderate these associations?

Method

Literature Search

From September 2012 to March 2013, the following electronic databases were searched: Ovid Medline, Mental Health Abstracts, PsycINFO, Social Sciences Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts via SocioFile, Academic Search Premier, Social Sciences Citation Index and ERIC. These online databases contain literature from a variety of disciplines, including social science, health and education. Table 1 summarises the search terms used. Searches were initially restricted to articles published between 2002 and 2013, written in English and originating from an English-speaking country. The date restrictions were later broadened from literature published in the last decade to literature published in the last two decades (1993–2013) to increase the yield of possible studies. The reference lists of articles that met the inclusion criteria were also examined for relevant studies. In addition, to identify possible unpublished sources, emails were sent to two authors who had published two or more articles on concepts related to school belonging.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used:

-

1.

Participants were between 12 and 18 years of age on average.

-

2.

Data were collected in secondary school settings.

-

3.

Quantitative research methodology was used.

-

4.

Variables relevant to at least one of the 10 themes were included.

-

5.

School belonging (or related terms, such as school connectedness) was defined in the same way as described by Goodenow and Grady (1993).

-

6.

School belonging (or related terms) was used as a dependent variable in the study.

-

7.

School belonging was measured with more than one item.

-

8.

An effect size (Pearson r) was reported or could be calculated from the reported analyses.

Studies outlining single item measures of school belonging were excluded, as previous literature has revealed that school belonging is a complex, multi-factorial construct (e.g. Shochet et al. 2011), and thus, single item measures would not reliably measure the construct. The inclusion criteria did not strictly select studies employing random control trials (RCT) or quasi-experimental methods, given the insufficient number of such studies available within the school belonging literature.

Study Identification and Selection

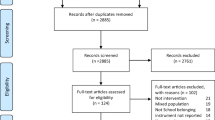

Figure 1 summarises the study selection process, based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (The PRISMA Group 2009). An initial pool of 623 studies was identified for inclusion (588 from the online database search, 35 studies from back searching, 0 studies from email solicitations). Articles were first screened according to age of sample, use of quantitative methodology, written in English and from an English-speaking country. From this primary screening, 220 studies were excluded. Then, consideration of the methodology and statistical results identified studies that included one or more of the themes as independent variables, school belonging as a dependent variable and effect sizes being available or could be calculated. This eliminated 344 studies. In all cases where data were not available, study investigators were contacted to supply the missing information, but this did not yield any further information. A final review eliminated 14 studies due to missing data or deficient measurement, resulting in a final set of 51 studies.

Study inclusion process, following the PRISMA guidelines for reporting (The PRISMA Group 2009)

Coding

The first author coded all studies into a spreadsheet. An independent coder reviewed 10 of the 51 studies. Strong inter-rater reliability occurred across the 10 studies (Cohen’s kappa coefficient κ = 0.88). Discrepancies were resolved through conversation, and agreement was met on all differences. The following information was extracted from each study: year of study, country of study, school location (urban, rural), school type (government/public, independent non-religious, independent religious), sample size, average age and age range of participants, gender (% female) and average school belonging scores (and standard deviation).

Effect Size Extraction

The Pearson r correlation coefficient was used as the indicator of effect size. For studies that directly reported an r correlation between a predictor and school belonging (k = 39, 76.5 % of studies), the reported value was recorded. Seven studies employed linear regression, and four studies used ANOVA. The reported means and standard deviations were converted to r, using the Lyons Morris calculator (www.lyonsmorris.com/ma1/index.cfm) when F values, means or standard deviations were reported, and using the Campbell collaboration calculator (www.campbellcollaboration.org/escalc/html/EffectSizeCalculator-R6.php) when t scores were reported. For the one study that employed linear regression and did not report r, the model was a simple regression and the correlation coefficient was obtained from R 2.

As studies included multiple independent variables, most studies contributed more than one effect size. The 10 themes were analysed separately, and thus, these multiple effects were retained. Three studies (Frydenberg 2009; Heaven et al. 2002; Walker 2012) included two effect sizes for a single theme. Although it is common to average the effects to create a single effect (e.g. Lipsey 1994), we kept one effect, choosing the value with the greatest cohesion to the other constructs of the themed category. For example, Heaven et al. (2002) contributed two effect sizes to the parent support independent variables: mother care and father care. As other studies used mothers as primary caregivers, the father care effect was deleted. Supplemental Table S2 notes the other items that were deleted, and includes our rationale for the effect sizes that were retained for the meta-analysis when more than one was available within a given study.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) Software (version 3.0). Average effects and 95 % confidence intervals were calculated for the 10 themes (academic motivation, emotional stability,Footnote 1 personal characteristics, parent support, peer support, teacher support, gender, race and ethnicity, environmental safety and extracurricular activities). We focus on the more generalisable random effects model but also report fixed effects estimates for completeness.

Beyond the overall effects, a value of meta-analysis is to identify moderators of the effect (Rosenthal and Dimatteo 2001). We tested one continuous moderator (year of study) and two categorical moderators: country of study (Australia, USA; dummy coded with Australia as the reference group) and location of school (urban, suburban, rural, mixed; dummy coded, with mixed as the reference group). The three moderators were simultaneously entered into a meta-regression analysis, testing their unique effect, using a random effects model. In each case, we only tested moderation for themes with 10 or more studies (excluding race, environmental and extracurricular themes).

As attempts to contact authors for unpublished studies were unsuccessful, the included studies were all published peer-reviewed research. While this may be seen as advantageous in promoting the use of scholarly quantitative research methodology, the sample may also be at risk of publication bias. To address the possible file drawer problem, we report the fail-safe N (FSN), which indicates the number of studies with contradictory findings that would be needed to reduce the average effect size to nil (Rosenthal 1991). However, the FSN focuses on statistical significance, not clinical significance. The Orwin variant provides an alternative metric, which allows comparison to an alternative level of significance. Although indicators of a meaningful effect are somewhat arbitrary, we chose to test the number of studies with nil effect (r = 0) that would be needed to reduce the overall effect below r = 0.10. We also present funnel plots, which draw the effects proportional to the precision of the estimates (Viechtbauer 2010). When a funnel plot is symmetrical, there is no evidence of publication bias. If publication bias exists and the true effect size is zero, then the funnel plot will be hollow in the middle.

Results

Overall Study Characteristics

Fifty-one studies were included in the analysis. Study information and effect sizes are summarised in Table 2, organised by each of the 10 themes. Studies were published between 1993 and 2013 (M = 2006; SD = 4.66). Sample sizes ranged from 45 to 7613 (total N = 67,378, 48.7 % female). Across the 32 studies reporting age information, participants’ mean age ranged from 12 to 18 years (M = 15.00, SD = 1.56). Studies were conducted in three countries: USA (k = 39, 76 %), Australia (k = 11, 22 %) and New Zealand (k = 1, 2 %). School locations varied, with 28.6 % located in urban settings, 21.4 % in suburban areas, 11.2 % classified as rural and 38 % mixed. Three types of schools were included: government/public (68.4 %), independent religious (4.1 %) and independent non-religious (27.6 %). Sampling techniques included random (31.6 %), convenience (50 %) and biased (18.4 %).

Across studies, 114 effects were derived from the 51 studies. Figure 2 visualises the effects and 95 % confidence interval for studies within each theme, with markers sized according to sample size. Academic motivation was the most commonly studied theme, and extracurricular activity was the least commonly studied theme. Most studies (93.9 %) found a statistically significant association between the independent variables and school belonging. One hundred seven effects were positive and 7 effects were negative. Individual effect sizes ranged from r = −0.20 (for gender, Shochet et al. 2011) to r = 0.80 (gender; Sirin and Rogers-Sirin 2005), and most effects were moderate in size. Figure 2 visualises the effects and 95 % confidence interval for studies within each theme, with markers sized according to sample size.

Average Effects by Theme

In general, most independent variables were positively related to school belonging. Table 3 summarises the number of effect sizes (k), included sample size (N) by theme, average effects (r) and 95 % confidence intervals, and Fig. 2 illustrates the overall effects. Teacher support (r = 0.46 [0.37, 0.54]) had the strongest effect, more so than peer support (r = 0.32 [0.2, 0.42]) or parent support (r = 0.33 [0.29, 0.36]), and this was followed by personal characteristics (r = 0.44 [0.36, 0.52]). For teacher support, the independent variables of autonomy, support and involvement (0.78); caring relationships (0.68); and fairness and friendliness (0.63) offered the strongest effect sizes. Extracurricular activities and race/ethnicity were not significantly related to school belonging, and in the fixed effect analysis, extracurricular activities were found to be associated with less school belonging.

Table 3 also reports the fail-safe Ns and more conservative Orwin variant as indicators of the robustness of effects. Effects were robust for parent support, teacher support, emotional stability and personal characteristics, with the Orwin FSN indicating that over 40 null studies would be needed to reduce effects to less than r = 0.10. Supplemental Figure S1 illustrates the funnel plots, mapping the Fisher Z for each study against the standard error. There is evidence of bias across the themes, although parent support and personal characteristics were the least biased amongst the 10 themes.

Moderator Effects

As indicated in Table 3, there was considerable heterogeneity for each theme, suggesting that the average effects may be impacted by research study characteristics. Publication year, country of study and geographic location of the school were tested as potential moderators, separately for each theme. Table 4 summarises the meta-regression results. Publication year moderated personal characteristics, such that effects were slightly stronger in more recent years (illustrated in Supplemental Figure S2). There were no trends for publication year for any of the other themes, indicating that correlations between each theme and school belonging were consistent over time. Country was not a significant moderator for any theme.

There was a certain level of dependency on geographical location. Significant differences were found between geographical regions in all of the themes except gender. To explore this moderating effect further, Table 5 breaks down the effect sizes (based on a random effects model) for each location (also illustrated in Supplemental Figure S2). Rural locations tended to have stronger effect sizes (r = 0.51), whereas urban locations tended to be smaller (r = 0.25). Similarly, for teacher support, the correlation in rural locations was 0.55 and in urban location, 0.31. The exception was emotional stability; the effect was strong for mixed locations (r = 0.49), whereas effects were similar in rural (r = 0.18) and urban (r = 0.21) locations.

Discussion

A sense of school belonging is an important factor that contributes to students’ academic success and psychosocial functioning. Multiple individual, social and environmental factors have been identified as possible correlates of school belonging. Stemming from Bronfenbrenner’s (1994) bioecological framework, the themes that have previously been identified in the literature were clustered into the individual level (academic motivation, emotional stability, personal characteristics, gender and race/ethnicity), the microsystem level (parent support, peer support, teacher support) and the mesosystem (extracurricular activities and environmental/school safety variables). The purpose of this meta-analysis was to examine the extent to which 10 different themes relate to school belonging, as well as investigate macrosystem (country and geographic location) and chronosystem (year of study) moderators of these effects.

Across 51 studies and over 67,000 participants, all but race/ethnicity and extracurricular activities were significantly related to school belonging, with the largest effects for teacher support and personal characteristics. Effects were moderated by geographic location, with stronger effect sizes for rural schools. As a whole, this study gives educators, school leaders and school psychologists more insight into the factors that correlate with school belonging, and potentially provides guidance for future interventions.

Individual Level Factors

Variables associated with future aspirations and goals, academic self-regulation, self-academic rating, education goals, motivation and valuing academics were related to greater school belonging. However, this was dependent on geographic location; academic motivation was strongly related to school belonging in rural and suburban schools, with much weaker correlations in urban settings. Although schools often focus on academic achievement and performance, by targeting the learning process rather than performance itself, students may benefit from both better performance and a greater sense of school belonging (see also Dweck et al. 2014). These findings are and have tangible implications for school strategies in respect to teaching and encouraging motivational skills.

Emotional stability demonstrated a sizable impact on school belonging. A growing body of research clearly illustrates the negative impact of mental illness and negative affect on the experiences of students towards school (e.g. McMahon et al. 2008; Shochet et al. 2007). The findings further support the need for mental health promotion in schools, with the early identification of students with mental health concerns by school staff members. McMahon et al. (2008) suggested that an important resource for young people is social support from others, which may act as a buffer against depressive symptoms; therefore, the themes of parent, peer and teacher support identified in this study hold great promise towards future interventions in this area (e.g. peer to peer coaching and mentoring).

One of the themes that was most strongly associated with school belonging was positive personal characteristics, such as conscientiousness, optimism and self-esteem. Literature in both personality and positive psychology disciplines have identified positive characteristics as correlates of good social relationships. Almost all of the studies showed moderate to high correlations with school belonging. The weakest correlates, though still moderate in size, were self-esteem and social self-efficacy.

Over the last decade, schools have become increasingly aware of the importance of how the personality of students impacts well-being (Friedman and Kern 2014). Social and emotional curricula have gained increasing popularity in recent years as an approach for bolstering positive personal characteristics. The growing areas of positive psychology and positive education focus on building personal strengths and positive characteristics in young people (e.g. Kern et al. 2015; Seligman et al. Linkins 2009; White and Waters 2015), and a growing number of interventions and curricula are being developed that potentially support and build these characteristics (Kern et al. 2016). However, it is unknown the extent to which developing positive personal characteristics will have the same benefit as those seen in correlational research. Different characteristics might have more of an impact or be easier to change than others. Further work is needed that describes which personal characteristics are most relevant as well as the best strategies for building these characteristics.

Demographic factors related to school belonging were less consistent. Gender was only weakly associated with school belonging, such that girls tended to feel a greater sense of belonging than boys. Race/ethnicity was not significantly related to school belonging but also was only included in four studies. Three studies (i.e. Bonny et al. 2000; Cook et al. 2012; Voelkl 1997) found a significant positive association, whereas one study found a non-significant negative effect (Whitlock 2006). Effect sizes for all studies were small (r = −0.01 to −0.25). Generalised conclusions cannot be drawn due to the small sample of studies and variability in results. Future studies should be directed towards drawing from much broader ethno-representative samples.

Micro Level Factors

A second set of themes reflected the microsystem surrounding the student. Parent, peer and teacher support were each strongly related to school belonging, thus highlighting the importance of building healthy and effective school communities and the influence of significant others. This is consistent with past research that has noted the importance of relationships for positive youth functioning (e.g. Brophy 1988; Hawkins et al. 1992; Lerner et al. 2005; Poortinga 2012; Ranson and Urichuk 2008).

Contrary to expectations, peer support, while influential towards school belonging, made less of a contribution to school belonging when compared with parent support or teacher support. Such a finding is contrary to others suggesting that peers are the strongest influence on daily behaviour at school (Steinberg 2001), but are consistent with studies that suggest that the quality of relationships matter. It may be the type of peers who determine attitudes and feelings towards school, rather than just the presence or absence of peers (Galliher et al. 2004; Gering 2009). Studies that measured caring relationships, having friends at school and positive perceptions of relationships demonstrated moderate to strong associations with school belonging, whereas associations were mixed for acceptance and perceived social support, ranging from r = 0.07 to r = 0.54. The impact of peers may depend upon the variable of interest.

A growing body of literature underscores the importance of adult relationships in a secondary school setting (e.g. Anderman 2002; Greenberger et al. 1998; Shochet et al. 2011; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2006). In line with other research (Hattie 2009), the strongest factor impacting school belonging was teacher support. Students who believe that they have positive relationships with their teachers and that their teachers are caring, empathic and fair and help resolve personal problems, are more likely to feel a greater sense of belonging than those students who perceive a negative relationship with their teachers. Negative interactions with parents or peers can even be intervened by teachers, and while the family may be the first unit to which children belong, students often spend more time at school (Hamre and Pianta 2006). Schools might support teacher-student relationships through school-sanctioned activities such as home/tutorial systems and student inductions at the start of each year. School leaders can encourage teachers to provide general pastoral support to students so that they are available to students for personal support as well as academic support. Of course, referral to relevant support services should be encouraged when student issues arise that require specialised support.

The findings also suggest that schools may benefit from enlisting the help of parents as part of a whole-school approach towards fostering school belonging. Home and school potentially can benefit from working together to create a supportive atmosphere. Schools might consider ways of involving parents in school life, such as parent information sessions and ensuring that effective communication is occurring between school and home. For example, schools could use information nights to assist parents with fostering positive parent-child relationships and positive communication skills and prioritising and valuing educational goals. School support and teaching staff may also provide appropriate referral pathways and support to parents in navigating relationships with the young person.

Mesosystem Level Factors

Mesosytem level factors of extracurricular activities and environmental/school safety variables were also explored, but were limited by the studies that included such factors. Only five studies included measures of extracurricular activities. Effects were non-significant, small (r = −0.09) and negative in the fixed effect model. Several studies suggested a positive correlation between extracurricular activities and a sense of school belonging (Blomfield and Barber 2010; Waters et al. 2010); however, there may be an optimal number of extracurricular activities a student should be involved in (Knifsend and Graham 2012), and the type of activity might matter. The six studies concerned with fostering a safe school environment (i.e. Cunningham 2007; Garcia-Reid et al. 2005; Hallinan 2008; Holt and Espelage 2003; Shochet et al. 2007; Whitlock 2006) suggested that perceived safety is important, though effects were small. Future research might focus more on mesosystem level factors, but at this time, schools might benefit more from focusing on personal characteristics and peer, parent and teacher relationships.

Macrosystem and Chronosystem Level Moderators

We included three moderators representing broader system factors. Results were consistent across country. Previous research (e.g. Willms 2003) has also shown little variability in school belongingness across countries similar to the present sample. Still, studies were primarily based in the USA and Australia, and whether or not results generalise to other countries and cultures is unknown, especially for non-western and developing countries.

Year of publication generally did not moderate results, except for the theme of personal characteristics, where there was a trend towards more positive effects in the more recent years. This rise may correspond with the increasing focus and interest in positive characteristics that has come from positive psychology (Rusk and Waters 2013). For other themes, the individual and micro level factors influencing school belonging were consistent over time.

The one factor that did matter was geographic location. Effects generally were stronger in rural and suburban areas than in urban and mixed areas, particularly for academic motivation, personal characteristics and teacher support. This finding may relate to the smaller class sizes, less disciplinary problems, greater participation in extra-curricular activities and more time for individual student-teacher interactions in rural schools than schools in urban settings (Freeman and Anderman 2005; Knoblauch and Woolfolk-Hoy 2008). It is also possible that urban schools are more heterogeneous, including both high socio-economic private schools as well as low-income, at-risk schools. Unfortunately, insufficient information was available in the studies to identify the economic status or student composition, but the impact of income and minority status should be explored as potential moderators in future research. Studies might also examine which aspects of the geographic location might have the greatest impact on the extent to which different factors relate to a sense of belonging

Limitations

Various limitations of the current meta-analysis can be observed. First, the influence of themes identified in this study with school belonging cannot be regarded as causal (Goodenow and Grady 1993). For example, the sociometer theory of Leary et al. (1995) suggests that self-esteem is a gauge that lets one monitor whether their behaviours are socially appropriate, rather than being a driver of belongingness. Similarly, if one is motivated and engaged at school and receives good results, one may equally have positive feelings about the school. Many of the studies were cross-sectional and/or focus on correlational associations, and while these factors are thought to impact school belonging, the study designs do not allow causal direction to be determined.

Second, only some studies reported student age, such that it could not be assessed as a moderator. Age also varied within each sample, such that mean levels might not capture individual variation that occurs within each sample. We limited the analysis to secondary school students, reducing the ages covered, but future studies might examine patterns of school belongingness across the adolescent years.

Meta-analysis has been the source of a variety of criticisms, such as the tendency for including articles with poor design and unreliable measures, weak criteria for article selection and bias towards selecting articles with positive and significant findings (DeCoster 2004). The current study endeavoured to overcome some of these criticisms through the use of a clearly defined inclusion criteria and methodology for data extraction and management. This resulted in a relatively small number of studies included in the analysis, compared to the initial search. Many of the initially identified studies referred to school belonging but did not include it as part of a quantitative study. The analysis was limited to secondary schools, to capture a sensitive period of adolescent development. School belonging has been used in a variety of ways. Relaxing this definition might have included a greater number of studies, but would also make the construct itself less interpretable. Despite these limitations, studies were still heterogeneous in terms of the study populations included and the measures used. Future studies might use inclusion criteria that are more or less strict.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study quantitatively identified the association between school belonging and a variety of factors. To date, the field of school belonging has relied on literature reviews to summarise and draw conclusions from a broad range of studies (i.e. CDC 2009; Wingspread Declaration on School Connections 2004). Despite the valuable contribution these reviews made to the field of school belonging, such qualitative reviews can be prone to methodological limitations due to the types of studies that are reviewed, as well as the subjective nature of the interpretation of findings from a single study (see Wolf 1986). Meta-analysis adds an element of objectivity.

Implications and Future Research and Practice

A degree of caution should be used when applying the present finding to interventions, and what these associations look like practically requires further research. Numerous studies have identified factors that are related to school belonging, and the findings here summarise the factors that have the strongest influence. A next valuable step will be determining the extent to which intervention increases these different factors and the resulting downstream effects on school belonging. These interventions may occur at any one of the socio-ecological levels. As personal characteristics and teacher support had the strongest associations with school belonging, it might be good to target one or both of these factors. One example can be drawn from Cornelius-White (2007), who found that learner-centred teacher variables were positively associated with positive student outcomes. Strategies on how schools can foster teacher support within their settings highlight an important area for further study.

Studies generally have focused on single factors, typically related to the individual or immediate context (e.g. academic motivation or parent support). The findings from this meta-analysis suggested that macro level variables moderate individual and micro level factors. For instance, there was some evidence that school belonging depended on geography for some themes but not others. Moreover, this study provides some evidence for macrosystem level influences on other levels within the school system (e.g. individual and microsystem layers). It will be beneficial in the future to study the extent to which the different socio-ecological levels interact, and which combination of factors best support student belonging.

Policy makers and change agents within governments and schools need to reassess the importance of well-being for young people at school and highlight the value of school belonging for psychosocial functioning and academic outcomes (Lonczak et al. 2002; Nutbrown and Clough 2009; Sari 2012). A bioecological framework might provide a bigger picture perspective on whole-school approaches towards cultivating school belongingness. Rather than focusing their interventions at an individual level, it may be beneficial to consider the impact of broader level factors (Roffey 2011; Waters et al. 2010; Waters 2011), which the school has more control over than individual factors or peer and parent relationships.

Findings from this study summarise themes and constructs that have a stronger or weaker influence on school belonging across multiple system levels. However, educators and psychologists should take into account the unique cultural considerations and context of each school. For example, school geography may have a slight role to play in terms of how some of the themes interact with school belonging. These findings are also only generalisable to school belonging amongst adolescents in secondary school settings and potentially schools of the same ilk. While using a random effects model allows results to be more generalised, a limited number of studies were included, which could bias the types of schools included. Different factors may be relevant for other types of schools and other educational levels.

The findings supported the importance of teachers for fostering school belonging. Schools should be careful to not undermine the importance of the student-teacher relationship, irrespective of the simplicity or natural occurrence of this relationship (Hattie 2009). A teacher’s ability to implement a curriculum or bolster the study scores of students was not reported in the literature as a concern for students, yet it can often be a pressing burden for teachers in modern-day schools (Roffey 2012; Thompson 2013). This is perhaps a reflection of the pressure by governments and legislation to prioritise academic outcomes above other important factors.

Conclusion

The advancement of school belonging research is important for schools and policy makers that advocate for primary preventative measures to foster both academic and well-being outcomes in students. By understanding the factors that are most strongly related to school belonging, schools and policy makers can identify key places in the system to intervene, or alternatively that might be markers of poor school belonging. The findings underscore the value of student-teacher relationships, not only for academic outcome (Hattie 2009) but also for a sense of belonging to a school community. Further, positive personal characteristics matter, and finding ways to develop such characteristics in young people may have a beneficial impact both on students’ sense of belonging, as well as their success in school. Schools may benefit from enlisting the help of parents and the wider community in the implementation of a whole-school intervention that addresses the individual and microsystem level variables identified in the study through a bioecological framework. Home, school and community must work together to create a supportive atmosphere that emphasises the importance of school belonging, as each facet has relevance and importance to student well-being. Factors both within and outside the student are related to their sense of school belonging. Regardless of causal directions, there is value in exploring these themes further across the multiple levels of students’ socio-ecological systems.

Notes

Markers of poor psychological functioning (e.g. depression, psychoticism, emotional distress) were combined as markers of emotional instability, which we expected to be inversely related to school belonging. For ease of presentation and consistency with other categories, we reversed the effect sizes, such that higher scores indicate less psychological distress, and label this category “emotional stability”.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

Allen, K., Ryan, T., Gray, D., McInerney, D., & Waters, L. (2014). The Social Media use in Adolescents: The positives and the pitfalls. Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 31, 18–33.

Allen, K. A., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2016). Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33, 97–121.

Allen, K., & Bowles, T. (2013). Belonging as a guiding principle in the education of adolescents. Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 12, 108–119.

Anderman, E. M. (2002). School effects on psychological outcomes during adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 795–809. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.795.

*Anderman, L. H. (2003). Academic and social perceptions as predictors of change in middle school students’ sense of school belonging. Journal of Experimental Education, 72(1), 5–22.

Barber, B. K., & Schluterman, J. M. (2008). Connectedness in the lives of children and adolescents: a call for greater conceptual clarity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43(3), 209–216.

Battistich, V., Solomon, D., Kim, D., Watson, M., & Schaps, E. (1995). Schools as communities, poverty levels of student populations, and students’ attitudes, motives, and performance: a multilevel analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 627–658.

*Benner, A. D., Graham, S., & Mistry, R. S. (2008). Discerning direct and mediated effects of ecological structures and processes on adolescents’ educational outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 44(3), 840–854.

Blomfield, C., & Barber, B. L. (2010). Australian adolescents’ extracurricular activity participation and positive development: is the relationship mediated by peer attributes? Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 10, 114–128.

*Bonny, A. E., Britto, M. T., Klostermann, B. K., Hornung, R. W., & Slap, G. B. (2000). School disconnectedness: identifying adolescents at risk. Pediatrics, 106, 1017–1021.

*Bowen, G., Richman, J. M., & Bowen, N. K. (1998). Sense of school coherence, perceptions of danger at school, and teacher support among youth at risk of school failure. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 15, 273–286.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss, volume 2: separation. New York: Basic Books.

Brechwald, W. A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 166–179.

*Brewster, A. B., & Bowen, G. L. (2004). Teacher support and the school engagement of Latino middle and high school students at risk of school failure. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 21(1), 47–67.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In T. Husen & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 1643–1647). Oxford: Pergamon/Elsevier.

*Brookmeyer, K. A., Fanti, K. A., & Henrich, C. C. (2006). Schools, parents, and youth violence: a multilevel, ecological analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35(4), 504–514.

Brophy, J. (1988). Research linking teacher behavior to student achievement: potential implications for instruction of chapter 1 students. Educational Psychologist, 23, 235–286.

Brown, R., & Evans, W. P. (2002). Extracurricular activity and ethnicity: creating greater school connection among diverse student populations. Urban Education, 37(1), 41–58. doi:10.1177/0042085902371004.

Brown Kirschman, K. J., & Karazsia, B. T. (2014). The role of pediatricpsychology in health promotion and injury prevention. In M. C. Roberts, B. Aylward, & Y. Wu (Eds.), Clinical Practice of Pediatric Psychology (pp. 136–138). New York: Guilford Press.

Brutsaert, H., & Van Houtte, M. (2002). Girls’ and boys’ sense of belonging in single-sex versus co-educational schools. Research in Education, 68, 48–57.

*Caraway, K., Tucker, C. M., Reinke, W. M., & Hall, C. (2003). Self-efficacy, goal orientation, and fear of failure as predictors of school engagement in high school students. Psychology in the Schools, 40(4), 417–428.

*Carter, M., McGee, R., Taylor, B., & Williams, S. (2007). Health outcomes in adolescence: associations with family, friends and school engagement. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 51–62.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). School connectedness: strategies for increasing protective factors among youth. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Chan, K. (2008). Chinese children’s perceptions of advertising and brands: an urban rural comparison. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25(2), 74–84.

Cohen, A. P. (1985). The symbolic construction of community. London: Tavistock.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2003). Safe and sound: an educational leaders’ guide to evidence-based social and emotional learning (SEL) programs. Retrieved from www.casel.org.

Connell, J. P., & Wellborn, J. G. (1991). Competence, autonomy and relatedness: a motivational analysis of self-system processes. In M. R. Gunnar & L. A. Sroufe (Eds.), Minnesota symposium on child psychology, 22 (pp. 43–77). Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Connell, J. P., Halpern-Felsher, B., Clifford, E., Crichlow, W., & Usinger, P. (1995). Hanging in there: behavioral, psychological, and contextual factors affecting whether African-American adolescents stay in school. Journal of Adolescent Research, 10(1), 41–63.

Cook, J. E., Purdie-Vaughns, V., Garcia, J., & Cohen, G. L. (2012). Chronic threat and contingent belonging: protective benefits of values affirmation on identity development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(3), 479–496.

Cornelius-White, J. H. D. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77, 113–143.

Croninger, R. G., & Lee, V. E. (2001). Social capital and dropping out of high school: benefits to at-risk students of teachers’ support and guidance. Teachers College Record, 103(4), 548–581.

Cunningham, N. J. (2007). Level of bonding to school and perception of the school environment by bullies, victims, and bully victims. Journal of Early Adolescence, 27(4), 457–458.

Davis, K. (2012). Friendship 2.0: Adolescents' experiences of belonging and self-disclosure online. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1527–1536.

DeCoster, J. (2004). A meta-analysis of priming effects on impression formation supporting a general model of informational biases. Personality and Social Society Review, 8(1), 2–27.

Demanet, J., & Van Houtte, M. (2012). School belonging and school misconduct: the differing role of teacher and peer attachment. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 41, 499–514. doi:10.1007/s10964-011-9674-2.

Dotterer, A. M., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2007). Implications of out-of-school activities for school engagement in African American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 391–401.

Drolet, & Arcand. (2013). Positive development, dense of belonging, and support of peers among early adolescents: perspectives of different actors. International Education Studies, 6(4), 29–38.

Dweck, C. S., Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2014). Academic tenacity: mindsets and skills that promote long-term learning. Seattle: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Epstein, J. (1992). School and family partnerships. In M. Alkin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of educational research (6th ed., pp. 1139–1151). New York: MacMillan.

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity, youth, and crisis. New York: Norton.

Fiske, S. T. (2004). Social beings: A core motives approach to social psychology. Hoboken: Wiley.

Freeman, T. M., & Anderman, L. H. (2005). Changes in mastery goals in urban and rural middle school students. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 20(1), 123–212.

Friedman, H. S., & Kern, M. L. (2014). Personality, well-being, and health. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 719–742.

Frydenberg, E. (2009). Interrelationships between coping, school connectedness and wellbeing. Australian Journal of Education, 53, 261–276.

*Galliher, R. V., Rostosky, S. S., & Hughes, H. K. (2004). School belonging, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms in adolescents: an examination of sex, sexual attraction status, and urbanicity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33(3), 235–245.

*Garcia-Reid, P. (2007). Examining social capital as a mechanism for improving school engagement among low income Hispanic girls. Youth & Society, 39, 164–181.

*Garcia-Reid, P. G., Reid, R. J., & Peterson, N. A. (2005). School engagement among Latino youth in an urban middle school context: valuing the role of social support. Education and Urban Society, 37(3), 257–275.

Gering, S. (2009). The interactions of academic press and social support: a descriptive review of the literature and recommendations for comprehensive high schools (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3393988)

Gillen-O’Neel, C., & Fuligni, A. (2013). A longitudinal study of school belonging and academic motivation across high school. Child Development, 84(2), 678–692. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01862.

Goodenow, C. (1993). Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: relationships to motivation and achievement. Journal of Early Adolescence, 13(1), 21–43. doi:10.1177/0272431693013001002.

*Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71.

Greenberger, E., Chen, C., & Beam, M. R. (1998). The role of “very important” nonparental adults in adolescent development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 27(3), 321–343.

*Hallinan, M. T. (2008). Teacher influences on students’ attachment to school. Sociology of Education, 81(3), 271–283.

Hamm, J. V., & Faircloth, B. S. (2005). The role of friendship in adolescents’ sense of school belonging. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2005(107), 61–78. doi:10.1002/cd.121.

Hamre, B., & Pianta, R. (2006). Student-teacher relationships as a source of support and risk in schools. In G. G. Bear & K. M. Minke (Eds.), Children’s needs III: development, prevention, and intervention (pp. 59–71). Bethesda: National Association of School Psychologists.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: a synthesis of meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

Hawkins, J. D., & Weis, J. G. (1985). The social development model: an integrated approach to delinquency prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention, 6(2), 73–97.

Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., & Miller, J. Y. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance-abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 64–105.

*Heaven, P. C., Mak, A., Barry, J., & Ciarrochi, J. (2002). Personality and family influences on adolescent attitudes to school and self-rated academic performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(3), 453–462.

*Henrich, C. C., Brookmeyer, K. A., & Shahar, G. (2005). Weapon violence in adolescence: parent and school connectedness as protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37, 306–312.

Hill, P. L., Allemand, M., Grob, S. Z., Peng, A., Morgenthaler, C., & Käppler, C. (2013). Longitudinal relations between personality traits and identity aspects during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 413–421.

Hirschkorn, M., & Geelan, D. (2008). Bridging the research-practice gap: research translation and/or research transformation. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 54(1), 1–13.

*Holt, M. K., & Espelage D. L. (2003). A cluster analytic investigation of victimization among high school students: are profiles differentially associated with psychological symptoms and school belonging? The Journal of Applied School Psychology, 19, 81–98.

*Jennings, G. (2003). An exploration of meaningful participation and caring relationships as contexts for school engagement. The California School Psychologist, 8, 43–52.

Johnson, L. S. (2009). School contexts and student belonging: a mixed methods study of an innovative high school. The School Community Journal, 19(1), 99–119.

Jose, P. E., Ryan, N., & Pryor, J. (2012). Does social connectedness promote a greater sense of well-being in adolescence over time? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(2), 235–251. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00783.x.

*Kaminski, J. W., Puddy, R. W., Hall, D. M., Cashman, S. Y., Crosby, A. E., & Ortega, L. A. (2010). The relative influence of different domains of social connectedness on self-directed violence in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(5), 460–473.

*Kelly, A. B., O’Flaherty, M., Toumbourou, J.W., Homel, R., Patton, G. C., White, A. & Williams, J. (2012). The influence of families on early adolescent school connectedness: evidence that this association varies with adolescent involvement in peer drinking networks. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(3), 437–447.

Kern, M. L., Adler, A., Waters, L. E., & White, M. A. (2015). Measuring whole-school well-being in students and staff. In Evidence-based approaches in positive education (pp. 65–91). Dordrecht: Springer.

Kern, M. L., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Romer, D. (2016). The positive perspective on youth development. In Evans D. L. (Ed.), Treating and preventing adolescent mental disorders (v. 2). New York: Oxford University Press (in press).

Knifsend, C., & Graham, S. (2012). Too much of a good thing? How breadth of extracurricular participation relates to school-related affect and academic outcomes during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 379–389. doi:10.1007/s10964-011-9737-4.

Knoblauch, D., & Woolfolk-Hoy, A. (2008). “Maybe I can teach those kids”. The influence of contextual factors on student teachers’ efficacy beliefs. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 166–179.

*Kuperminc, G. P., Leadbeater, B. J., & Blatt, S. J. (2001). School social climate and individual differences in vulnerability to emotional instability among middle school students. Journal of School Psychology, 39(2), 141–159.

Law, P. C., Cuskelly, M., & Carroll, A. (2013). Young people’s perceptions of family, peer, and school connectedness and their impact on adjustment. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 23(1), 115–140. doi:10.1017/jgc.2012.19.

Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: the sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 68(3), 518–553.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Almerigi, J., Theokas, C., Naudeau, S., Gestsdottir, S … & von Eye, A. (2005). Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth grade adolescents: findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 17–71.

Libbey, H. P. (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 275–283.

Lipsey, M. W. (1994). Identifying potentially interesting variables and analysis opportunities. In H. M. Cooper & L. V. Hedges (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis (pp. 111–123). New York: Sage.

Lonczak, H. S., Abbott, R. D., Hawkins, J. D., Kosterman, R., & Catalano, R. (2002). The effects of the Seattle social development project: behavior, pregnancy, birth, and sexually transmitted disease outcomes by age 21. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 156, 438–447.

Loukas, A., Roalson, L. A., & Herrera, D. E. (2010). School connectedness buffers the effects of negative family relations and poor effortful control on early adolescent conduct problems. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(1), 13–22.

Ma, X. (2003). Sense of belonging to school: can schools make a difference? Journal of Educational Research, 96(3), 340–349. doi:10.1080/00220670309596617.

Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a psychology of being. New York: D. Van Nostrand.

McMahon, S., Parnes, A., Keys, C., & Viola, J. (2008). School belonging among low-income urban youth with disabilities: testing a theoretical model. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 387–401.

McNeely, C. A., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Promoting school connectedness: evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of School Health, 72(4), 136–146.

Mensah, F. K., Bayer, J. K., Wake, M., Carlin, J. B., Allen, N. B., & Patton, G. C. (2013). Early puberty and childhood social and behavioral adjustment. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1), 118–124.

*Mo, Y., & Singh, K. (2008). Parents’ relationships and involvement: effects on students’ school engagement and performance. Research in Middle Level Education Online, 31(10), 1–11.

Moody, J., & Bearman, P. S. (2004). Suicide and friendships among American adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 94(1), 89–95.

*Nichols, S. L. (2006). Teachers’ and students’ beliefs about student belonging in one middle school. Elementary School Journal, 106(3), 255–271.

Nutbrown, C., & Clough, P. (2009). Citizenship and inclusion in the early years: understanding and responding to children’s perspectives on ‘belonging’. International Journal of Early Years Education, 17(3), 191–206. doi:10.1080/09669760903424523.

O’Brennan, L. M., & Furlong, M. J. (2010). Relations between students’ perceptions of school connectedness and peer victimization. Journal of School Violence, 9(4), 375–391.

O’Connor, M., Sanson, A, Hawkins, M. T., Letcher, P., Toumbourou, J. W., Smart, D., … Vassaollo, S. (2010). Predictors of positive development in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(7), 860–874.

O’Rourke, J., & Cooper, M. (2010). Lucky to be happy: a study of happiness in Australian primary students. Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 10, 94–107.

Osterman, K. F. (2000). Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 323–367.

Pittman, L. D., & Richmond, A. (2007). Academic and psychological functioning in late adolescence: the importance of school belonging. Journal of Experimental Education, 75, 275–290.

Poortinga, W. (2012). Community resilience and health: the role of bonding, bridging, and linking aspects of social capital. Health & Place, 18, 286–295.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Quinn, S., & Oldmeadow, J. A. (2013). Is the igeneration a ‘we’ generation? Social networking use among 9- to 13-year-olds and belonging. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 136–142.

Ranson, K. E., & Urichuk, L. J. (2008). The effect of parent–child attachment relationships on child biopsychosocial outcomes: a review. Early Child Development and Care, 178, 129–152.

Read, B., Archer, L., & Leathwood, C. (2003). Challenging cultures? Student conceptions of ‘belonging’ and ‘isolation’ at a post-1992 university. Studies in Higher Education, 28(3), 261–277.

*Reschly, A. L., Huebner, E. S., Appleton, J. J., & Antaramian, S. (2008). Engagement as flourishing: the contribution of positive emotions and coping to adolescents’ engagement at school and with learning. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 419–431.

*Roche, C., & Kuperminc, G. P. (2012). Acculturative stress and school belonging among Latino youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 34(1), 61–76.

Roeser, R. W., Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. C. (1996). Perceptions of the school psychological environment and early adolescents’ psychological and behavioral functioning in school: the mediating role of goals and belonging. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 408–422.

Roffey, S. (2011). The new teacher’s survival guide to behaviour. London: Sage.

Roffey, S. (2012). Pupil wellbeing – teacher wellbeing: two sides of the same coin? Educational & Child Psychology, 29(4), 8–17.

Rosenthal, R. (1991). Meta-analytic procedures for social research (Revth ed.). Newbury Park: Sage.

Rosenthal, R., & DiMatteo, M. R. (2001). Meta-analysis: Recent developments in quantitative methods for literature reviews. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 59–82.

*Rostosky, S. S., Owens, G. P., Zimmerman, R. S., & Riggle, E. D. B. (2003). Associations among sexual attraction status, school belonging, and alcohol and marijuana use in rural high school students. Journal of Adolescence, 26, 741–751.

Rusk, R. D., & Waters, L. E. (2013). Tracing the size, reach, impact, and breadth of positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(3), 207–221.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and wellbeing. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

*Ryan, R. M., Stiller, J. D., & Lynch, J. H. (1994). Representations of relationships to teachers, parents, and friends as predictors of academic motivation and self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence, 14(2), 226–249.

*Ryzin, M. J., Gravely, A. A., & Roseth, C. J. (2009). Autonomy, belongingness, and engagement in school as contributors to adolescent psychological wellbeing. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(1), 1–12.

Sakiz, G. (2012). Perceived instructor affective support in relation to academic emotions and motivation in college. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology, 32(1), 63–79.

Samdal, O., Nutbeam, D., Wold, B., & Kannas, L. (1998). Achieving health and educational goals through schools: a study of the importance of the climate and students’ satisfaction with school. Health Education Research, 3, 383–397.

*Sanchez, B., Colón, Y., & Esparza, P. (2005). The role of sense of school belonging and gender in the academic adjustment of Latino adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(6), 619–628.

Sari, M. (2012). Sense of school belonging among elementary school students. Çukurova University Faculty of Education Journal, 41(1), 1–11.

Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35, 293–311.

*Shochet, I. M., Dadds, M. R., Ham, D., & Montague, R. (2006). School connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: results of a community prediction study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(2), 170–179.

*Shochet, I. M., Smith, C. L., Furlong, M. J., & Homel, R. (2011). A prospective study investigating the impact of school belonging factors on negative affect in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(4), 586–595. doi:10.1080/15374416.2011.581616.

*Shochet, I. M., Smyth, T. L., & Homel, R. (2007). The impact of parental attachment on adolescent perception of the school environment and school connectedness. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 28(2), 109–118.

*Simons-Morton, B. G., Crump, A. D., Haynie, D. L., & Saylor, K. E. (1999). Student-school bonding and adolescent problem behavior. Oxford Journals, 14(1), 99–107.

*Sirin, S. R., & Rogers-Sirin, L. (2004). Exploring school engagement of middle-class African American adolescents. Youth & Society, 35(3), 323–340.

*Sirin, S. R., & Rogers-Sirin, L. (2005). Components of school engagement among African American adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 9(1), 5–13.

Steinberg, L. (2001). We know some things: parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11(1), 1–19.

Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 83–110.

*Stoddard, S. A., McMorris, B. J., & Sieving, R. E. (2011). Do social connections and hope matter in predicting early adolescent violence? American Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3–4), 247–256.

Tanti, C., Stukas, A. A., Halloran, M. J., & Foddy, M. (2011). Social identity change: shifts in social identity during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 34(3), 555–567.

The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, flow chart. Retrieved from http://www.prisma-statement.org/index.htm