Abstract

This paper reviews current known issues in student self-assessment (SSA) and identifies five topics that need further research: (1) SSA typologies, (2) accuracy, (3) role of expertise, (4) SSA and teacher/curricular expectations, and (5) effects of SSA for different students. Five SSA typologies were identified showing that there are different conceptions on the SSA components but the field still uses SSA quite uniformly. A significant amount of research has been devoted to SSA accuracy, and there is a great deal we know about it. Factors that influence accuracy and implications for teaching are examined, with consideration that students’ expertise on the task at hand might be an important prerequisite for accurate self-assessment. Additionally, the idea that SSA should also consider the students’ expectations about their learning is reflected upon. Finally, we explored how SSA works for different types of students and the challenges of helping lower performers. This paper sheds light on SSA research needs to address the known unknowns in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Future of Student Self-Assessment: Known Unknowns and Potential Directions

Student self-assessment (SSA) most generally involves a wide variety of mechanisms and techniques through which students describe (i.e., assess) and possibly assign merit or worth to (i.e., evaluate) the qualities of their own learning processes and products. This involves retrospective monitoring of previous performance (Baars et al. 2014) and reporting, hopefully truthfully, the quality of work completed. The purpose of this manuscript is to review what it is known and unknown about student self-assessment (SSA) after decades of research and, based on such evidence, highlight plausible lines of research that could make better known what we currently know is unknown. SSA has been extensively and vigorously recommended as an appropriate approach to student involvement in formative assessment, wherever the “assessment for learning” reform agenda has been advocated (Berry 2011; Black and Wiliam 1998). Hence, it is important for education that we have a clearer understanding of SSA.

While the field of empirical studies into SSA is increasing, it seemed timely to review what has been established in SSA since so many studies seem to only be replicating, in new contexts, what we already know about SSA. Hence, the purpose of this paper is to expand upon these known and unknown issues and consider plausible directions for future research. We consider that the known unknowns, which will be established in this review, are so substantial that our recommendations are unlikely to be a roadmap with clear signposts and indicators of progress. Rather, we consider that this paper functions more as a series of lighthouses highlighting well-trodden rocky shores and pointing out more profitable directions in which SSA research should head.

SSA is an important skill for at least four reasons. First, students who are trained in SSA have shown an increase in their learning and academic performance (Brown and Harris 2013; Panadero et al. 2012; Ramdass and Zimmerman 2008). Additionally, accuracy (i.e., reliable and valid assessment) in SSA is moderately associated with higher levels of outcomes (Brown and Harris 2013). Second, training in SSA can increase the use of self-regulated learning strategies (Kostons et al. 2012; Panadero et al. 2016), and vice versa, students who have good self-regulatory skills use more advanced self-assessment strategies (Lan 1998). SSA helps students regulate their own learning by requiring them to exercise metacognitive monitoring of their work and processes against standards, expectations, targets, or goals (Panadero and Alonso-Tapia 2013). Third, training SSA skills can enhance students’ self-efficacy in the tasks being performed (Olina and Sullivan 2004; Ramdass and Zimmerman 2008), but this effect has not been consistently found (e.g. Andrade et al. 2009). Fourth, SSA is related to students’ empowerment in the assessment process, which further activates their ownership of learning and use of self-regulatory strategies (Black and Wiliam 1998; Nicol and McFarlane-Dick 2006; Tan 2012a; Taras 2010). In sum, SSA appears to play an important role in academic success, and consequently, there is widespread advocacy for SSA as a powerful educational learning process (e.g., Dochy et al. 1999). Indeed, it has been recommended that a curriculum for SSA be developed so that students can develop skills in SSA in the context of classroom activities (Brown and Harris 2014).

This review is not an encyclopedic attempt to account for all studies in SSA, nor is it a meta-analysis of empirical effects (see Brown and Harris 2013 for a meta-analysis in the K-12 sector). Rather, this review represents a conceptual synthesis of the field in order to make sense of important themes and topics that need deeper examination. These included (a) establishing a clear understanding of what SSA actually is, (b) determining the role truthfulness or accuracy in SSA plays, and (c) evaluating a number of student and teacher factors that impact on the quality of SSA implementation. Therefore, the paper is organized around five topics: (1) SSA typologies, (2) accuracy of SSA, (3) the role of expertise for SSA, (4) SSA and teacher/curricular expectations, and (5) the effects of SSA for different students. Within each topic, we reflect on plausible directions as well as implications for research.

Self-Assessment Typologies

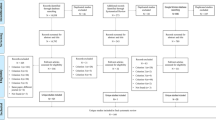

Given the breadth and generality of the SSA definition we gave at the start of the paper, we searched for comprehensive definitions of SSA. Even though self-assessment has a long tradition in practice and research (Boud and Falchikov 1989; Leach 2012; Tan 2012a), few distinctions are made among the various SSA techniques. A useful approach to defining a field is the creation of a typology in which systematic and universal distinctions, similarities, and ordered classifications are generated across multiple SSA practices. We performed a search using PsycINFO and ERIC databases with a combination of keywords (i.e., self-assessment or self-evaluation and type/s, typology/ies or format/s), without producing any results. Nevertheless, we already knew of two articles addressing typologies of SSA. Additionally, through personal communication with three self-assessment scholars, two more typologies were identified. Finally, the most recent typology was added upon its publication. Therefore, five studies that attempt to develop typologies for SSA are reviewed (Table 1).

Knowledge Interest Typology

Boud and Brew (1995) organized self-assessment around three different formats based on the “knowledge interest” pursued by the students in particular tasks: (a) technical interest: the purpose of self-assessment is to check what skills, knowledge, ideas, etc. have been correctly understood; (b) communicative interest: the purpose is communication and interpretation of the assessment elements (for example students discussing with the teacher what assessment criteria to consider); and (c) emancipatory interest: the purpose is that students engage in a critique of the standards and assessment criteria, making their own judgments about their work. Boud and Brew also distinguished between self-assessment and other related self-evaluative methods such as self-testing (students checking their performance against provided test items), self-rating (providing a scale for students to rate themselves), and reflective questioning (materials that prompt the students about what they have been reading). According to Boud and Brew, self-testing and self-rating are not SSA because “students are not normally expected to actively engage with or question the standards and criteria which are used” (p. 2). They rejected reflective questions because:

“…self-assessment is usually concerned with the making of judgments about specific aspects of achievement, often in ways which are publicly defensible (e.g. to teachers), whereas reflection tends to be a more exploratory activity which might occur at any stage of learning and may not lead to a directly expressible outcome” (p. 2).

Strengths and Gaps in the Boud and Brew Typology

Positive aspects of this typology are that it (a) was the first attempt to distinguish between different SSA, (b) emphasized the crucial role of intentions to conduct SSA, and (c) separated SSA from other less beneficial self-evaluation techniques (e.g. self-rating). Nevertheless, it is questionable whether the “emancipatory interest” is enacted and/or crucial for students at all levels of education. The emancipatory interest might well be a function of students’ increase in self-regulation throughout their school career (Paris and Newman 1990) and as such be more readily applicable to vocational and/or higher education settings (Sitzmann and Ely 2011). Secondly, the communicative interest appears to refer to the stage of criteria setting and much less to the process of self-assessment itself which, as we know, it is only the initial approach for a more efficient implementation of SSA in the classroom (Andrade and Valtcheva 2009; Panadero and Alonso-Tapia 2013). Finally, this taxonomy reflects different purposes that SSA can follow, but does not explore if they have any impact on different implementations of SSA. Therefore, it represents more a taxonomy of the purposes of SSA than of real SSA practices.

Student/Teacher Involvement Typology

Tan (2001) proposed a typology of SSA formats according to the continuum of teacher involvement, which he related to formative and summative assessment purposes. He identified six SSA formats from least to most teacher involvement and, hence, most to least formative: (a) self-awareness: students are aware of their thinking processes and assess them, but without a formal comparison (i.e., no external criteria or teachers); (b) self-appraisal: students self-assess without a formal comparison but they are aware of the external demands and assess having their teachers’ expectations in mind (in other words: the anticipation of what the teacher’s criteria might be); (c) self-determined assessment: students decide what information they need to assess their work and how and whom to ask for feedback; (d) self-assessment practice: compounded of a range of practices (although not specified in the Tan typology) in which the students self-award themselves a grade, and if there are differences with the one from the teacher, both negotiate the final grade; (e) self-assessment task: when the self-assessment only concerns assessing a specific task; and (f) self-grading/self-testing: upon request by the teacher (e.g., via task) or a system (e.g., via computer) students assess at a surface level and mainly with summative purposes. Note that this last definition was constructed by the authors based on Tan’s example, since he did not clearly define this last SSA format.

Strengths and Gaps in the Tan Typology

Positive aspects of this typology are that it (a) outlined potential effects of more in-depth SSA practices, (b) clarified the role of teachers in each of the formats, (c) presented possible effects of teachers’ expectations on students’ SSA intentions, and (d) introduced the idea of power status in the different formats—although this idea is more apparent in Tan (2001) than in the typology itself. Nevertheless, the presumption that “degree of teacher involvement” equates to an assessment being formative or summative is faulty (Hattie and Brown 2010). As stated by Hattie (2009), it is crucial to consider the use of the information (by a certain actor) to determine whether the assessment is formative or summative. While purists may argue that involving a teacher makes self-assessment summative, it is not clear that teacher-initiated SSA automatically prevents formative uses of SSA by students themselves. In the case of self-awareness, the absence of the teacher neither prevents the students themselves using the information for a summative decision nor is it automatic that the teacher played no part in the student being self-aware. Indeed, support from the teacher seems to be crucial for the development of self-regulated learning skills such as SSA (Ley and Young 2001). Additionally, the boundaries between the SSA formats are blurry, especially between self-assessment task and self-grading/self-testing.

Power and Transparency Typology

Similarly, Taras (2010) identified different SSA typologies, based on the ideas of power balance between the students and their teacher and transparency of the SSA format. In the order of the weakest to strongest—in terms of power balance and degree to which decision-making is shared between the students and their teacher—she distinguished five formats. The two weakest formats are (a) self-marking: students use “a model answer(s) with criteria (and possibly mark sheets) to compare to their own work” (p. 202); those criteria are provided by the teacher and students just apply it; and (b) sound standard of SSA where the tutor provides descriptors and exemplars of work of different quality levels, which is similar to self-marking but adding an exemplar. In contrast, three other formats were considered progressively stronger: (c) standard model in which students use criteria to evaluate their work (although Taras specifies neither where the criteria came from nor who established them), provide feedback (unclear to whom), and grade their work; (d) self-assessment with integrated tutor and peer feedback before performing independent individual self-assessment; and (e) learning contract design, in which self-assessment is established via a learning contract and the student makes all the decisions.

Strengths and Gaps in the Taras Typology

Positive aspects of this typology are that it (a) further explored the role of power balance in SSA and (b) presented the idea of transparency in SSA via the use of assessment criteria and exemplars. Nevertheless, as with Tan, it seems that the boundaries between the five formats are blurry; especially, differences between “sound standard” and “standard SSA” are difficult to distinguish. Second and most important, the differences in power and transparency (i.e., the two defining dimensions of the entire typology) (Taras 2010) are not made explicit for all SSA formats. Third, it seems contradictory that in the format where students are assumed to have the most power, they first need to make a contract (presumably with teacher implying a lack of control) before being allowed to make “all” decisions. Additionally, Taras (2015) recently presented a revision of this typology in which the two most powerful types were re-categorized as the least powerful types, but a clear rationale and justification for the re-arrangement were not provided. In our view, Taras’ revision of the typology further adds to the unclarity of SSA typologies and highlights the need for empirical evaluation of theoretical assumption underlying SSA typologies.

Presence and Form of Assessment Criteria Typology

Panadero and Alonso-Tapia developed and empirically tested a typology which proposed three SSA formats based on the presence and form of the assessment criteria (Alonso-Tapia and Panadero 2010; Panadero et al. 2013a). The three formats were (a) standard self-assessment (sometimes called self-grading) in which students are asked to self-assess without being given explicit criteria (most of the empirical research using standard SSA does not state whether, and if so how, criteria were provided); (b) use of rubrics in which students are given a rubric that includes criteria and performance standards with specific examples of the final product; and (c) use of scripts which include criteria presented as questions that the students need to answer for themselves; these are similar to prompts but focus on the task process. Scripts enhanced more self-regulation than the rubric, and both scripts and rubrics produced better learning results compared to control groups in a low-stakes experimental setting for secondary education students (Panadero et al. 2012). In higher education, when the self-assessed task counted toward final grades, rubrics (a) enhanced performance, (b) reduced performance and avoidance goals, (c) were preferred by the students in comparison to scripts or the combination of a script and rubric (Panadero et al. 2013a, 2014a), and (d) resulted in higher use of self-regulatory learning strategies, performance, and accuracy when compared to a group using standard self-assessment (Panadero and Romero 2014).

Strengths and Gaps in the Panadero and Alonso-Tapia Typology

Positive aspects of this typology are that it (a) has been empirically tested through true experimental method, (b) emphasized the differential psychological effects of SSA (e.g., self-regulated learning skills), (c) had a focus on the SA effects on learning, (d) analyzed the SSA process itself to understand what actually happens during SSA, and (e) was a practical and easily applicable typology. Nevertheless, a concern with this typology is that the SSA formats mix the assessment method (how and by which instrument a performance is scored) and the instructional approach (how the self-assessment skill is trained and/or the process of scoring is supported), as if these were interdependent constructs. A certain instructional approach may be conventionally associated with an assessment method but this is not intrinsic to teaching or assessment. Second, it is not always clear whether rubrics and scripts are self-assessment tools that aid or scaffold SSA or whether the methods are SSA itself. This is problematic since SSA itself remains an inner process, not subject to direct inspection.

Self-Assessment Procedure Typology

In a recent review, Brown and Harris (2013) classified SSA according to the format of how the self-assessment was carried out: (a) self-ratings, (b) self-marking or self-estimates of performance, and (c) criteria- or rubric-based assessments. Self-rating occurs when a rating system (e.g., checklists of tasks or processes completed or smiley face ordinal ranks) is used by the students to judge quality or quantity aspects of their work. Self-marking asks students to mark or grade their own work, using objective scoring guides (e.g., correct answer mark sheets or scoring rules). These guides contain more information regarding the task and its evaluation than the subjective rating or compliance checklists, allowing the students to score their work against an agreed standard or criterion. Finally, criteria- or rubric-based assessments guide the student in judging work against hierarchical descriptions of increasing quality. In this format, the focus is on using the rubric to guide judgment of quality concerning a complex piece of learning.

Strengths and Gaps in the Brown and Harris Typology

Positive aspects of this typology are that it (a) was grounded in empirical evidence for the formulated categories, (b) further clarified the role of scoring in SSA, (c) took a generic approach to SSA so that studies could be more easily combined, and (d) was an easily applicable typology. Nevertheless, the major concern with this typology is that it is silent about the possibility of completely unguided intuitive formats or other new formats of SSA (e.g., scripts; Panadero 2011). This has arisen because the typology is empirically derived from published studies in which external SSA mechanisms were deployed in K-12 education. This means that the typology does not include all possible formats, just those discovered in the studies reviewed. The data analysis conducted by Brown and Harris (2013) concludes that self-marking using objective scoring guides and subjective self-rating were less powerful because they did not necessarily require students to exercise complex evaluations. However, this is but an incipient typology derived empirically, rather than theoretically. It is also noted that many self-assessment researchers would probably reject the notion that self-marking or self-rating could be considered appropriate SSA formats due to their limitations (e.g., shallow learning approach to the task) (Alonso-Tapia and Panadero 2010; Boud and Falchikov 1989).

Summary of Typologies

Overall, the five typologies reflect different understandings of self-assessment based on issues of power, transparency, use and presence of assessment criteria, psychological implications and processes, participation of the students, purpose of self-assessment, assessment methods, and/or instructional support. We identified two additional tensions between the five typologies: (a) while Tan and Taras share similarities in how they conceptualize power (esp. concerning teacher vs. student control and transparency), the type of power described by Tan (2001) would not allow for the categorization by Taras (2010), and (b) while Boud and Brew (1995) explicitly rejected “reflective questions” as SSA, Panadero and Alonso-Tapia explicitly use these questions in their typology within the SSA script format (Panadero 2011).

Nonetheless, it seems appropriate that the field agrees that SSA is not a unidimensional construct. Several factors may importantly alter the nature of making a self-assessment. These include, among others (a) the medium of SSA, (b) the delay between SSA and the last learning or instructional session, (c) learners’ expectations about the type and purposes of assessment for which they will be assessed, and (d) whether learners are provided “no criteria” versus specific criteria. These various factors have different impacts on the function and effect of SSA, and their relative weight has not coherently and consistently been established. The development of a comprehensive typology would need to take into account the various current typologies informed by a systematic review of factors and conditions identified by empirical studies reviewed in this paper.

Moreover, a curricular perspective on self-assessment needs to be developed; for example, are some self-assessment techniques easier to learn or teach? and do some methods lead to more veridical/honest or accurate self-assessments? (Brown and Harris 2014). While it might be tempting to claim that certain SSA methods are superior in their impact on learning (e.g., rubrics), Brown and Harris (2013) found that the greatest and least gains were associated with rubric methods. Thus, research into conditions that maximize the benefit of any SSA method and its underlying typology is still required.

Implications for Research

A first implication is that much of what we claim to know about SSA treats the different SSA formats as if they were uniform, whereas the field has quite different understandings of SSA formats (as reflected in the five typologies) which in turn leads to different practices (Brown and Harris 2013; Panadero 2011). For example, there is no consensus as to what “standard self-assessment” even means because different SSA typologies have classified a variety of formats (e.g., those which do not or do have explicit assessment criteria and those with and without training in the application of those criteria) as the “standard SSA” format. It might be useful to define “standard SSA,” following Panadero and Alonso-Tapia (Panadero et al. 2012), as “asking students to self-assess without clearly stated assessment criteria,” though this still leaves uncertain as to whether this involves a purely descriptive act or also includes an evaluative merit-judgment.

Secondly, more information is needed about the conditions under which various SSA formats promote, or even hinder, learning. Empirical evidence that focuses on comparing learning effects related to different SSA formats is scarce, with only some exceptions (e.g., Goodrich Andrade and Boulay 2003; Panadero et al. 2012, 2013a, 2014a; Panadero and Romero 2014; Reitmeier and Vrchota 2009). In sum, there is a need for systematic coherence in how the SSA formats are described and classified within typologies. With such clarity, empirical studies into the differential impact or value of various SSA formats would be feasible. From this review, it seems reasonably clear that SSA is in danger of jingle-jangle fallacies (Roeser et al. 2006) in that different kinds of SSA are given the same name, while similar kinds of SSA are sometimes given different names. Resolving this nomenclature challenge will permit greater understanding as to what is being done and how it works.

Additionally, it is important that the field further develops a better understanding of an essential aspect of SSA in relation to the typologies. SSA can happen spontaneously and automatically in an internal way, in which students may not be aware of their own processing because it is not explicit (Winne 2011). For example, having highly automatized behaviors, such as driving a manual transmission vehicle, may under conventional circumstances be subconsciously monitored and adjusted without a great deal of reflection. However, under stressful conditions such as icy roads, greater attention is required, resulting in conscious self-regulation of the driving process. Without conscious attention to actions, consequences, and circumstances, it is difficult to consider SSA to be self-regulatory. Therefore, pedagogical external factors may not be critical for SSA to occur, though it is difficult to consider such SSA as self-regulatory. Pedagogical factors should be designed so that they stimulate and support the acquisition of SSA skills by making SSA explicit—contingent upon the SSA format adopted and instructional support provided (Kostons et al. 2012).

Except for the Panadero and colleagues typology (Panadero 2011), the SSA typologies discussed do not speak directly to the method that students use to self-assess (e.g., rubric, self-rating scale, or self-marking on an objective test, etc.). The SSA format may even interact with the assessment method (e.g., high vs. low stakes; paper-and-pencil vs. oral interaction; personal vs. shared; etc.). This interaction may produce balanced or amplified results depending on the degree to which the SSA format and assessment method are optimal or suboptimal. Furthermore, the SSA format itself (e.g., number of criteria, presentation of criteria and standards, etc.) and variation in instructional support offered (e.g., scripts, exemplars, rubrics, etc.) may produce quite different SSA experiences with differential effects depending on where students are in their learning progress.

This complex situation in which much is known to be unknown suggests that three main avenues of research are required. First, experimental studies (Shadish et al. 2002) could clarify if there are potential differential effects according to SSA format and instructional support. For example, Panadero et al. (2012) conducted three trials in which students were randomly assigned to one of 12 different experimental conditions in which type of instruction, type of self-assessment, and type of feedback were systematically manipulated and found that SSA scripts and SSA rubrics had differential effects on self-regulation and learning. Further, controlled experimental studies are needed that manipulate both main and interaction effects around the various typologies reviewed so as to establish robust evidence concerning SSA formats. Second, research from real learning settings, in which quasi-experimental and naturalistic studies are used, is needed to establish the validity of laboratory studies for authentic contexts. Third, a better understanding of what happens in terms of cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and emotional processes while students are self-assessing is crucial to develop the field. Importantly, while designing such studies, differentiation of participants by their achievement levels (e.g., high vs. low) would identify the effects in different kinds students.

Accuracy: How to Make It Happen, Is It That Important and When/If Might It Be Good Not to Be Accurate

One of the points of self-assessment is to judge appropriately what went wrong so as to correct errors and identify what went right and repeat those behaviors (Dochy et al. 1999). Hence, a key requirement of SSA is that it supports appropriate inferences about the quantity and/or quality of work being evaluated (Kane 2006; Messick 1989). In SSA, such inferences depend, in part, upon SSA decisions being reasonably realistic. Realism, sometimes referred to as veridicality (Butler 2011), identifies the degree to which student descriptions about their work are perceptibly true or accurate. Panadero et al. (2013b) have suggested that accuracy or realism in SSA is a form of construct validity. In classical test theory, accuracy in assessment is expressed through statistics such as the standard error of measurement around observed scores; in SSA, accuracy has to be captured by the accuracy or realism of self-assigned evaluations.

While it can be argued that there is no objective truth to be used as a yardstick against which self-assessment could be measured (see for a discussion on this topic Tan 2012b; Ward et al. 2002), it is socially agreed, at least in education, that the realism of a self-assessment can be determined by the alignment of that self-judgment with performance on an externally administered test or task or against the judgments of appropriate content experts, such as teachers or even peers (Topping 2003). As an example of validating student perceptions with tested performance, consider research into memory of learning, known as “Judgment Of Learning” (JOL) (Nelson and Dunlosky 1991; Dunlosky and Nelson 1994; Meeter and Nelson 2003; Thiede and Dunlosky 1999). JOL research is able to validate in experimental laboratory studies the accuracy of student predictions of how well they will do on a memory test of paired-word associations by the learner’s actual performance on the test (i.e., prospective monitoring of future performance in contrast to retrospective monitoring of previous performance which is more correctly SSA; Baars et al. 2014), providing an objective measure of the accuracy of a relatively simple form of self-assessment (i.e., How many will you get right? Which of these will you get right?).

The validity concern that arises from “inaccuracy” in SSA, especially as it is commonly applied in classroom settings which require evaluations and descriptions of complex learning outcomes (e.g., Boud et al. 2013), is that students will make decisions about their learning that are not supported by their externally observable abilities, potential, or performance (Brown and Harris 2013; Dunning et al. 2004). For example, it has been established that judgments of learning are misled by (a) strong emotions which are referred to instead of actual capability (Baumeister et al. 2015) and (b) faulty memory of having learned something (Finn and Metcalfe 2014). Students who decide not to study for an upcoming assessment because they falsely believe their work is good enough (through some failure of meta-memory) or who decide not to pursue a career option because they consider they are deficient in that domain (Vancouver and Day 2005) are using “inaccurate” SSA to make educational decisions. Feedback to learners over their schooling careers is expected to correct unrealistic SSA (Hattie and Timperley 2007), so that students come to an appropriate, correct understanding of their own performance. Certainly, allowing new learning to enter into long-term memory is a strong mechanism for ensuring accurate prospective judgments of learning (Nelson and Dunlosky 1991). In this way, it is expected that through practice students become increasingly more accurately calibrated to externally valued criteria and standards (see Dochy et al. 1999) against which their work must be evaluated.

However, one of the problems with evaluating the accuracy of SSA is that research has focused predominantly on having students estimate their proficiency in terms of how accurately they can predict their performance as a grade or score on a test (Boud and Falchikov 1989; Dochy et al. 1999; Falchikov and Boud 1989; Nelson and Dunlosky 1991; Dunlosky and Nelson 1994; Meeter and Nelson 2003; Thiede and Dunlosky 1999). Reducing SSA to a score or grade judgment might not be as important to SSA accuracy as focusing on the “content-matter” of the SSA (Ward et al. 2002). In other words, it may be much more educationally powerful if students are accurate when describing the qualities of their work (i.e., its strengths or weaknesses that need to be improved) in terms of subject, discipline, or course “content-matter” accuracy. This skill seems more complex and potentially more meaningful than simply aiming to have students give the same score or grade as their teacher would give or that they might obtain on a test (Boud and Falchikov 1989). It is clear that two students with the same test performance may have achieved similar scores through answering correctly different parts of the test, just as a teacher may award students similar grades for different reasons. It is probably more important that students are able to accurately detect or diagnose what is wrong or right about their work and why it is that way than be able to accurately predict a holistic or total score or grade their work might earn (Boud and Falchikov 1989). The grander purpose of accuracy in SSA is to help students understand pathways to improvement, rather than achieve complacency with or despair about their grades.

In this fashion, SSA is an essential sub-process of self-regulated learning (SRL) (Kirby and Downs 2007; Panadero and Alonso-Tapia 2013; Paris and Paris 2001; Zimmerman 2000). Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) cyclical model divides the self-regulated learning into three phases (i.e., forethought, performance, and self-reflection). Intuitively, self-assessment occurs during self-reflection. However, given that self-assessment is the act of reflecting and monitoring on both learning processes and outcomes, SSA could occur during the whole process of self-regulated learning (Panadero and Alonso-Tapia 2013). Thus, it is possible that SSA, despite its nomenclature, should be treated more as a component of SRL than as assessment proper, a position advocated elsewhere (Andrade 2010; Brown and Harris 2014).

In a purely private SSA (or internal feedback as put by Butler and Winne 1995), where no corroboration of the assessment is sought or available, the accuracy of SSA is simply unknown and any inferences drawn or actions taken by the student based on that self-assessment cannot be properly evaluated. In such circumstances, not only is the accuracy of SSA not known but also the consequences of inaccuracy are unknown. Further, since the results of SSA may be negative and threatening to self-esteem (Schunk 1996), some students may resist disclosing their self-assessments to anyone, including the teacher (Cowie 2009). Indeed, it has been argued that SSA ought not to be disclosed, since the reasons and effects of SSA are intensely personal and difficult to inspect (Andrade 2010). Nonetheless, research makes it clear that students are aware that the teacher is the most expert person in the classroom and some have grave doubts as to the necessity of relying on anyone’s judgment other than that of the teacher (Gao 2009; Panadero et al. 2014b; Peterson and Irving 2008). Thus, some students are resistant to the very act of assessing themselves, preferring assessment done by the teacher.

In sum, SSA appears to have mysterious psychometric properties. On the one hand, SSA is an integral part of SRL and improved learning outcomes (Panadero and Alonso-Tapia 2013; Ramdass and Zimmerman 2008). On the other hand, it has a truly unknown amount of error (or unknown degree of reliability) and unknown degree of validity, which may limit the benefits of SSA (Brown and Harris 2013). While it seems appropriate to require that other assessments be accurate, it might well be that there are benefits from engaging in SSA even if it is unrealistic or inaccurate as advocated by some on the basis that any engagement in the process regardless of its accuracy is worthwhile (Andrade 2010; McMillan and Hearn 2008). However, our position takes a realist stance (Maul et al. 2015) that requires as validation evidence that the SSA approached as accurately as possible the actual characteristics of his or her performance or product. Holding positive self-efficacy beliefs and generally positive illusions about one’s performance contributes to task motivation and performance goals, in contrast to having negative, pessimistic illusions about one’s performance, which does seem to have a negative impact on motivation (Butler 2011). Nonetheless, in the long term, it seems desirable that students overcome both positive and negative illusions and become realistic in their SSA (Boud and Falchikov 1989). Whatever benefits that may accrue to the self in thinking unrealistically about the quality of one’s own work, these are likely to be potentially misleading, especially should the student reach an inaccurate, negatively biased self-appraisal (Butler 2011). Therefore, a consideration of the factors associated with greater perceived accuracy in SSA is warranted.

Factors Associated with Increased Accuracy in SSA

Notwithstanding the conceptually troublesome nature of reliability or accuracy in SSA, research has established factors and conditions under which students may be more or less realistic or accurate in their SSA. The evidence from the K-12 schooling sector (Brown and Harris 2013; Finn and Metcalfe 2014; Ross 2006) and from higher education (Boud and Falchikov 1989; Falchikov and Boud 1989) is strikingly similar. Novices and less able learners tend to overestimate their own work quality, while students with greater performance tend to give themselves grades or marks that are more aligned with teacher or tutor judgments or external test scores. Brown and Harris (2013) reported that overall, the mean level of agreement between self-assessments and other measures of performance tended to fall in the range of r = 0.30 to 0.50 explaining some 10 to 25 % of variance between the self-assessment and some external measure of performance. However, entry to university does not equate with being a relative expert; instead, it seems there is a reset in which early university students become novices relative to advanced students. The average correlation between teacher and university student SSA was medium (r = 0.39, much like the K-12 results), though this was much higher (r = 0.69) for students in advanced courses (Falchikov and Boud 1989). The relative complexity of professional practice (e.g., taking a patient history or teaching a class of children) and social science disciplines in contrast to science subjects seems to explain the weaker calibration of SSA to teacher grading (Falchikov and Boud 1989).

The consistent result that accuracy in SSA depends on expertise and ability in the domain reflects in part the well-established problems humans have in evaluating the quality of their own work (Dunning et al. 2004), which is especially pronounced among those with the least proficiency (Kruger and Dunning 1999). There is a dual handicapping at work with learners: until expertise or competence develops, students will tend to not only not know they are weak but also believe they are good (“ignorance is bliss”). Students’ false-positive perceptions of their own expertise are an important contributor to inaccurate SSA (Olina and Sullivan 2004). Unsurprisingly, this tendency is not sustainable in the long term for academic success (Sitzmann and Johnson 2012).

As expertise or proficiency develops, self-ratings tend to become less optimistic, but much more aligned with other measures of proficiency. For example, Sitzmann and Johnson (2012) found that “underestimators” (students with lower SSA than their current performance) had higher performance than “overestimators” (students with higher SSA than their current performance), a result found in other research as well (Boud et al. 2013; Leach 2012). Nonetheless, even highly competent people can err in their self-assessments by being overly pessimistic. This was convincingly demonstrated in experiments with high school students who had worked harder to learn and tended to underestimate their proficiency, perhaps because they relied on a negative perception of the effort they had spent, rather than focusing on the positive consequences of the mental effort they had invested in learning (Baars et al. 2014). Greater expertise may produce a greater awareness of how much more there is to learn or how much better others are and thus depresses SSA (Kruger and Dunning 1999). A clear contributor to greater accuracy in self-assessment is greater competence and experience with the skill or knowledge being self-assessed.

Furthermore, research makes it clear that greater accuracy in self-assessment occurs under a number of conditions (Brown and Harris 2013; Panadero and Romero 2014; Ross 2006). For example, use of concrete, specific, and well-understood criteria or reference points when evaluating one’s own work helps (e.g., Panadero and Romero 2014). Self-assessment grounded in a comparison to specific or target score values or people, rather than vaguely described grades or people not known personally, leads to more accurate self-assessment because more specific standards promote more realistic judgments (Kostons et al. 2012; Lindblom-Ylänne et al. 2006; Panadero et al. 2012). Moreover, students who are involved in developing criteria by which their work will be assessed seem to become more accurate in SSA (Brown and Harris 2013); however, existing evidence is not conclusive and sometimes even contradictory (Andrade et al. 2010; Orsmond et al. 2000). On the other hand, relying on one’s sense of effort rather than on some objective standard leads to less accurate self-assessment and dissatisfaction with the program and can distort students’ expectations (Taras 2003).

Additionally, as long as there are high-stakes consequences for the self or ego associated with assessing one’s own work to be of low or poor quality, there will be pressure to avoid criteria that lead to negative self-assessments (Boekaerts 2011). Effective learners not only self-assess the quality of their work more often (Lan 1998) but are also open to evidence from other sources as to the quality of their work and the relative merits of their own judgment (Kruger and Dunning 1999).

However, without a mechanism that forces students to make comparisons between what they think of their own work and what others think of their work (e.g., teacher or test feedback or peer assessment), self-assessment would appear to depend greatly on individual characteristics and differences. For this reason, among others, some SSA scholars have recommended that SSA requires training in which students receive feedback about their own SSA so as to become more accurate self-assessors (Cao and Nietfeld 2005; Dochy et al. 1999; Panadero and Alonso-Tapia 2013). Many empirical studies have demonstrated that students in K-12 can be taught skills of self-assessment, for example: explicit coaching in using a self-rating checklist or rubric and giving rewards for meeting challenging goals, contributed to accuracy (Brown and Harris 2013). Explicitly modeling veridical SSA in which poor work is accurately identified by a hypothetical student was found to improve the accuracy of retrospective and prospective monitoring of learning (Baars et al. 2014). Students who are more convinced of the learning benefits when applying rigorous self-evaluation of their learning will also do this more accurately (Sitzmann and Johnson 2012).

Hence, this review has identified a number of pedagogical efforts by which students can be taught to self-assess with a reasonable degree of accuracy or realism. While greater competence and expertise contributes to more realism in SSA, this leaves the question unanswered as to whether more accurate SSA should be learned, prior to or independent of becoming more competent or proficient in a knowledge domain. Furthermore, it remains unclear as to whether students can be taught to be aware of various human biases or heuristics that contaminate their own self-evaluations (e.g., being overly optimistic about own abilities, believing own ability is above average, neglecting crucial information, making a quick rather than considered assessment, relying on memory of previous performance, activation of inaccurate prior information, believing practice results in less learning, or falsely associating emotional arousal with learning; Baumeister et al. 2015; Dunning et al. 2004; Hadwin and Webster 2013; Kahneman 2011; Koriat et al. 2002; Van Loon et al. 2013).

Nonetheless, beyond focusing on the obvious priority of developing learner competence or expertise in a domain, teachers should be able to help students learn to honestly admit the strengths or weaknesses of their own work. This will require teachers and students both accepting that realism in SSA is what needs to be focused on and rewarded, as opposed to just performance. For example, including a self-reflective component in a course-work assignment so that students gain credit for identifying ways in which their work did not meet important criteria will foreground the importance of realism. Teachers who explicitly monitor SSA comments and considerately provide feedback that corrects any illusions of competence or incompetence may help develop greater SSA accuracy. However, the validity of these pedagogical recommendations in naturalistic classroom settings is generally not well attested to and explicit research studies are still required.

Implications for the Role of (In)Accuracy for Research on SSA

While improvement seems logically to require accuracy in SSA, it is not clear that realism is automatically converted into appropriate actions that lead to improved performance. Consistent with the cyclical model of SRL, a retrospective self-reflection on performance qualities must feed into a variety of planning, goal setting, motivation, learning strategies, and metacognitive performance monitoring processes to ensure improvement (Zimmerman and Moylan 2009). Based on the principles of feedback in instructional settings (Hattie and Timperley 2007; Narciss 2008; Sadler 1989), students need to first become aware of the possibility of inaccuracy in their self-assessments, perhaps through discrepancy between SSA and external evaluations (e.g., by a teacher or peer) of their performance. This requires (a) seeking corroboration or disconfirmation concerning the validity of their self-assessments (i.e., detecting the gap between their SSA and a veridical one), (b) choosing an appropriate action or inference from a number of alternatives to correct the detected areas of improvement (correction of the gap), and (c) being able to adequately execute the chosen action (closing the gap). Given that SSA is a metacognitive skill, motivation to actively conduct such monitoring is essential (Sitzmann et al. 2010).

Yet, there are clear reasons for students not being fully honest when asked to self-assess (e.g., protecting their ego, avoiding the teacher’s disappointment, etc.) and so teachers themselves should be aware that, whether intentional or not, there is (a) error in student self-assessment and (b) various sources contribute to error in self-assessment (Brown et al. 2015; Raider-Roth 2005). For example, based on in-depth case studies of three teachers’ classrooms, Harris and Brown (2013) concluded that students were much more aware of interpersonal factors (e.g., having their SSA seen by classmates or by the teacher) impinging on realistic SSA than were their teachers. To date, it is unclear, however, what adjustments (e.g., criteria, instruction, etc.) teachers can make in light of the possibility of inaccurate SSA. When considering teachers’ beliefs about SSA and the role of SSA accuracy, Panadero et al. (2014b) found that the use of SSA in classrooms was predicted mainly by three reasons: (a) teachers’ previous experience with SSA, (b) teachers’ beliefs on SSA learning advantages, and (c) teachers’ previous participation in assessment training. Issues of accuracy or lack of accuracy in SSA did not influence teachers’ implementation of SSA, even though a majority of teachers (57 % of 944) reported that SSA was not accurate. Therefore, even if accuracy is a concern, it need not stop teachers from implementing SSA in their classrooms.

A more substantial challenge to implementing SSA in classroom settings might lie in students’ perception that SSA is not actually assessment. For example, two surveys of New Zealand secondary students demonstrated that SSA and other interactive assessment practices were not generally considered to even be “assessment” (Brown et al. 2009a, b). Furthermore, it was found that defining assessment as informal-interactive practices (including SSA) did not contribute to improved achievement (Brown et al. 2009b). Hence, teachers will need to be able to persuade students that there is benefit in reflecting on the quality of work, even if this does not contribute to assessment per se.

Moreover, if self-assessment requires high levels of proficiency in a domain, it is unclear what less able or novice learners should do when asked to engage in SSA in the presence of more able students as is commonplace in classroom environments. The social and psychological threats of admitting weakness in skill or knowledge, let alone inaccuracy in self-evaluation, create a complex space in which both teachers and students work. How such complexities can be navigated in such a way that SSA is a meaningful pedagogical experience is still unknown.

It is also unclear when SSA should be used. Formative use requires that SSA be carried out early enough in the educational process that the outcome of SSA (i.e., information on what went well or what could be improved) can be used to guide action by the student on subsequent tasks (Scriven 1991). However, the earlier the self-assessment occurs, the more likely it will be that students will have insufficient knowledge to guide accurate self-assessment. If SSA is structured around a learning conversation with a teacher, it is more likely that existing inaccuracies will be identified, though ego and self-esteem risks may actually be higher. Therefore, research is needed to identify whether there is an optimal time period and format for carrying out SSA. Furthermore, research is needed to ascertain the effect of motivational and emotional safety techniques (e.g., avoiding comparison with classmates) that teachers can use to ensure that students apply themselves veridically in self-assessment (Alonso-Tapia and Pardo 2006).

In conclusion, we consider that “scoring accuracy” (the degree of closeness from the SSA scoring to an external source) needs to be differentiated from “content accuracy.” While the vast majority of SSA accuracy research has focused on the first (e.g., Brown and Harris 2013), there is a need to study the latter which is, in our point of view and that of others (Ward et al. 2002), of greater importance. We recommend that while simple studies of “scoring accuracy” may be needed in some teaching contexts, there is a greater need to explore the interaction of SSA with variables that impact scoring accuracy. Our reading of the literature further indicates that there are significant uncertainties around (a) whether or not students can self-detect inaccuracy in their own self-assessments, (b) whether there is an appropriate “range of tolerance” for inaccuracy, (c) whether it is necessary that SSA be judged against the judgments of teachers or experts, (d) whether it is possible to benefit educationally from SSA—even when students misjudge their own performance—(e) whether students ignore or prioritize feedback that contradicts their own SSA, and (f) whether having the ability to detect inaccuracy in one’s SSA enables the student to improve. Hence, we should stop studying accuracy in isolation and start exploring the effects of the various factors reviewed above in light of the questions that seem to be certainly unanswered. Second, studies into SSA accuracy should not be based on the goal of “saving teachers’ time” because good SSA implementation takes teachers’ time and effort to provide feedback and modeling of SSA (Goodrich 1996; Dochy et al. 1999; Kostons et al. 2012; Panadero and Alonso-Tapia 2013), a matter that some teachers seem to already know (Panadero et al. 2014b).

Do We Need Expertise in the Task at Hand to Self-Assess?

As mentioned previously, if students need to have some experience performing a task to successfully self-assess their work, it would seem that much SSA research may have been wasted effort. It seems important to understand two aspects regarding expertise and SSA: first, the role of expertise in the domain (knowledge, skills) being self-assessed and, second, the role of expertise in performing realistic self-assessment as a skill in itself. These are distinct issues, and probably, both contribute to the quality and impact of SSA.

The Role of Domain Knowledge in SSA

There are at least two main conditions why prior knowledge and expertise in the task domain matter to SSA. The first condition refers to the experienced cognitive load when students perform a task for the first time, that is, the majority of their cognitive resources is invested in performing the task (Plass et al. 2010; Sweller et al. 2011), thus leaving little or no space for monitoring what they are doing (Fabriz et al. 2013). Therefore, novice learners experience a higher degree of cognitive load when processing material that has not been automatized; thus, SSA challenges working memory capacity. Second, novice learners either lack or have less elaborate cognitive schemata (i.e., declarative and procedural knowledge) for the task at hand which also increases cognitive load. Both conditions imply that the monitoring component of self-assessment is more challenging for novices (Kostons et al. 2009, 2012; Kostons 2010). Furthermore, as a consequence of being a novice, students do not have clear standards about quality work in the domain, cannot easily change their actions during performance, and have difficulty in evaluating the quality of their products (Kostons et al. 2009, 2012; Kostons 2010). These cognitive difficulties generate serious questions about the legitimacy of being asked to self-assess when a learner is still a novice in a certain task domain. This raises the key question of whether students first need to have a certain minimum domain competence before they can be asked to meaningfully self-assess (especially if SSA is aimed at more than a simple (meta)memory-dependent task like judgment of learning). It also stimulates questions about when and how to offer training in self-assessment skills, given that training for SSA is needed.

A potential solution to these questions lies in SRL approaches in which shorter cycles of goals, performance, and self-reflection are used to structure complex tasks and scaffold the ability of the learner to gain competence in the domain and SSA of performance in the domain. For example, many rubric-based assessments of writing expect students to systematically describe and evaluate complex draft essays using criteria based on multiple dimensions or components (e.g., structure of an essay, its rhetorical stance, awareness of audience needs, selection of linguistic and vocabulary items, punctuation, grammar, and spelling); this naturally poses substantial challenge to teaching, learning, and assessment. By structuring the domain task into more narrowly focused components (e.g., focus only on the structure of the argument), more cognitive resources are available for accurate SSA. Likewise, focusing SSA on the process of composition (e.g., metacognitive monitoring of attention and effort), rather than just on quality of the product, might enable more accurate SSA. Having students concurrently, rather than just retrospectively, assess work processes and works in progress has been shown to improve learning and generate greater awareness of appropriate criteria and standards against which to evaluate work (Zimmerman 1989). Nevertheless, SRL ability “during and following participation in assessment depends on the developmental characteristics of the learner, the nature of the task and domain under consideration, and the regulatory outcome desired (i.e., cognitive, motivational, or behavioral)” (Dinsmore and Wilson 2015, p. 20). Hence, studies that evaluate SSA in light of these various factors within the context of structured and scaffolded SRL processes have yet to prove conclusively that such approaches will be consistently effective.

A second condition refers to students’ knowledge of the task at hand: if students do not have any idea of what they are supposed to do within a task domain, SSA is unlikely to be a pleasant or a beneficial exercise. Especially novice or low(er)-ability students would be repeatedly confronted with knowledge about lack of (or substandard) performance, especially if reinforced by external assessments. This may be a threat to the self and/or even encourage learned helplessness and decreased self-efficacy—the latter being a crucial component of self-regulatory strategies (Panadero and Alonso-Tapia 2014; Zimmerman 2000). Given the potential for a negative experience when required to SSA, it is not surprising that “self-assessments of knowledge are only moderately related to cognitive learning and are strongly related to affective evaluation outcomes” (Sitzmann et al. 2010, p. 183). If SSA repeatedly confirmed to the student that he or she performed poorly, this may decrease motivation to invest effort in the learning task.

Just as we cannot ask students to perform a novel task with the ease and fluency of an expert, so we should not expect students to conduct SSA with ease and accuracy, until they have mastered the relevant skills. As Goodrich (1996) put it, to self-assess, one needs to learn self-assessment. Students need direct instruction in and assistance with self-assessment, as well as practice in self-assessment. There may be an optimal level of self-assessment based on students’ prior experience of SSA. In other words, first-time self-assessment could be organized in “simpler” ways for novice students, perhaps by initially requiring them to assess their performance using fewer criteria, performing simpler versions of the task, and/or by providing guided self-assessment tools (e.g., rubrics or checklists) (see Panadero 2011). Unfortunately, research on SSA has not explored this issue in depth, although it has been recently approached by Brown and Harris (2014) who provide a skeleton outline of a curriculum for introducing SSA as a self-regulating competence, rather than as an evaluative act.

Implications for Research and Teaching

There are four aspects in which students’ need for prior experience, in both the task and SSA, has implications for research and teaching. First, it needs to be clear to teachers and researchers that SSA practice is key, and this still is not discussed in sufficient detail in most reports. When it comes to Spanish teachers, the biggest predictor for the use of SSA in the classroom was teachers’ previous positive experience in the implementation of SSA (Panadero et al. 2014b). This shows clearly that teachers not only have to provide opportunities for practice to the students but also need to gain experience with SSA within their own teaching practice. For field researchers in school contexts, this suggests that consideration has to be given to both teachers’ and students’ experience with SSA as these are both important variables in evaluating SSA impact.

Second, as a conclusion from the previous aspect, an incremental, structured implementation of SSA, along the lines suggested by Brown and Harris (2014), might be more beneficial because it emphasizes the relevance of practice. This would require gradually introducing SSA formats (i.e., from simpler formats such as JOL to more complex formats such as rubrics) and helping students and teachers focus on realism in SSA. Teachers would need to learn how to provide not only opportunities for practice but also constructive feedback about the realism of SSA and the task performance to their students (Goodrich 1996). In this sense, researchers need to develop interventions that scaffold SSA with students having different expertise levels (Panadero 2011; Reitmeier and Vrchota 2009). Future research should implement studies with a longitudinal design, with several points of measurement going along with different scaffoldings of SSA. For example, after establishing baseline indications of SSA quality, students can be introduced to relevant assessment criteria and evaluated to see if simply knowing criteria makes a difference, subsequently the cumulative effective of making rubrics, exemplars, or scripts available could be evaluated. Using balanced presentation designs, researchers could establish the relative benefit of these SSA scaffolds.

Third, researchers need to study the most effective instructional practices to implement various SSA formats, especially SSA scaffolding tools such as rubrics or scripts. This is important since there is debate in the field whether complex scaffolds (e.g., a rubric containing the criteria and relevant standards) may benefit novices because they provide clarity as to what quality performance looks like (Andrade and Valtcheva 2009; Panadero and Jonsson 2013), while others have suggested that rubric-based SSA be delayed until greater competence in the domain and veridical SSA is developed (Brown and Harris 2014). Clearly, a combination of experimental designs and ecological classroom research is needed to resolve the unknown issues identified here.

Fourth, students are under pressure to acquire domain knowledge and comparatively less time and effort (if at all) is focused on fostering students’ understanding of their own learning process within a particular domain, such as being able to realistically self-reflect on process and product. This may arise from educational system pressure to meet curriculum goals that typically emphasize domain knowledge, rather than the learning process. While calling for changes to accountability mechanisms that encourage narrow approaches to learning may be ineffective, it may be more useful if SRL, including the role played by SSA, is foregrounded as a central curriculum competence (Brown and Harris 2014). In this fashion, future research should continue the avenues of SSA research into its effects on SRL as proposed by Panadero et al. (2016).

SSA and Teacher/Curricular Expectations

Especially in formal educational settings (e.g., schools and higher education), SSA focuses on students evaluating their own work relative to externally devised curricular objectives and goals. While this is entirely understandable in terms of accountability and certification, it leaves open the possibility that explicit curricular goals could be defined in terms of the minimal expected competency. Requiring students to conduct SSA relative to these lower goals may unintentionally limit learning opportunities for students whose interests and goals differ to or go beyond those of the formal curriculum.

It seems legitimate to wonder whether, by focusing student attention and SSA on the explicit (and possibly minimal) goals of a course, we may be limiting their horizons. This is not just a matter of the teacher exercising power over the student or the educational program seeking to limit the future autonomy of the learner as discussed by Tan (2012a). Consistent with psychometric theory, all assessments are samples of a domain of interest, and the best that can be expected is that the domain is represented adequately, but never completely, in an assessment (Messick 1989). Hence, there is usually much more to learn in a domain than can be contained in any one assessment method or event (i.e., test, coursework, examination, etc.) and instructional guidance for self-assessment (e.g., scripts that are aligned to course objectives) may be good scaffolds for content novices conducting SSA but may interfere with domain expertise (Panadero et al. 2014a). It is possible that students could go well beyond what courses and instructors expect and inspect. It may be that SSA techniques, especially if used as part of grading, limit students from going beyond course expectations (Bourke 2014).

Nevertheless, it could be expected that students are likely to be learning things other than the explicit intentions or outcomes of a course. If so, then we are unlikely to know what those other things might be unless students conduct a self-directed SSA that reflects upon and communicates those other outcomes. In effect, self-assessment of learning beyond what is formally and officially expected in educational or training contexts may be a legitimate part of the function of SSA. The process of reflecting on such potential learning outcomes may help students improve their learning in valuable ways (e.g., deeper learning). Especially in professional learning contexts (e.g., graduate study of medicine, engineering, education, etc.), such self-assessment may contribute positively toward a greater sense of professional identity and competencies valuable to professional practice but which are not explicitly taught or assessed (Bourke 2014).

Such an approach to SSA, based on more personal goals and expectancies, is extraneous to explicit accountability processes. Hence, we face the challenge of how teachers might stimulate this type of self-assessment. Asking students to reflect on what else they are learning seems attractive to us. However, asking students to communicate such reflections to an instructor may invalidate the substance of such assessments. It is possible students would think “if SSA reveals I am learning or thinking things unrelated to the course, will my teacher cope with that?”. The act of publicly exposing one’s extra learning outcomes may threaten the realism and honesty that students would need to bring to the task. Relationships with teachers, instructors, or tutors constitute an interpersonal and social classroom environment in which learners may prefer to protect their self-esteem (Boekaerts 2011) or privacy (Cowie 2009). High levels of trust and safety would be needed to support such self-disclosure (Alonso-Tapia and Pardo 2006). To achieve this, students would need, no doubt, the right to non-disclosure, which, of course, may frustrate a teacher’s desire to understand what else students are learning. How we might initiate such useful reflection and learn what it is students are thinking about their own learning (beyond teacher set or curricular goals) is still unknown.

Different Students = Different Self-Assessment? In the Pursuit of Helping the Weakest

Two aspects about how SSA affects different students seem well established. First, the same SSA format does not work for everyone, and the most worrying cases are the lower achievers (Kruger and Dunning 1999). Second, this issue has been largely overlooked by research other than studies exploring SSA in terms of accuracy or realism (Boud et al. 2013; Sitzmann et al. 2010). The evidence (Boud et al. 2013; Brown and Harris 2013) shows that students who differ in terms of their academic achievement (e.g., poor, medium, above average) experience different learning effects through engagement in SSA. However, we still need more evidence as there are contradictory results with some studies reporting larger learning gains through SSA for initially lower performing students (Ross et al. 1999; Sadler and Good 2006), while other studies found that average students who are more accurate in their SSA benefit the most (Boud et al. 2013). Perhaps resolution of these differing results can be found in the suggestion by Hattie (2013) that learners, regardless of ability, are better at judging the quality of their performance at a generalized rather than at a task- or item-specific level. However, the latter is preferable for pedagogical purposes in that it allows students to better determine a plan for skill improvement and generate specific goals against which to gauge progress, potentially enhancing student motivation. This contrasting grain size may explain why SSA does not have consistent impact on learners. Nevertheless, these effects have not been studied in sufficient detail, meaning that research is needed to determine the appropriate grain size of performance being evaluated.

Apart from the apparent need for a basic degree of expertise/domain knowledge (see section “Do We Need Expertise in the Task at Hand to Self-Assess?”), differing levels of student expertise appear to have different consequences. On the one hand, students with high levels of expertise in a domain show a tendency to underestimate their performance when asked to self-assess (Boud et al. 2013; Brown and Harris 2013); in other words, they miscalibrate (i.e., have negative illusions) their performance toward more negative interpretations of their real abilities. Negative illusions about ability seem to arise from multiple reasons, including (a) relatively low, though unrealistic, self-esteem (Wells and Sweeney 1986), (b) less “emotional investment in achievement outcomes,” perhaps because of a strong focus on mastery or deep learning motivations and goals (Connell and Ilardi 1987, p. 1303), and (c) believing that their level of performance is actually accessible for others (Kruger and Dunning 1999). Moreover, Butler (2011) argues that the evidence shows that the impact of unwarranted negative illusions is negative. Nevertheless, it seems possible to train students with high levels of expertise to avoid such tendencies and accept that their work is actually high-quality (Kruger and Dunning 1999).

On the other hand, low achievers are overconfident (i.e., have positive illusions) about their performance for a number of reasons such as limited level of proficiency (Dunning et al. 2003; Kruger and Dunning 1999). Lower-performing students seem to only become aware of their actual relatively poor performance if given external metacognitive prompts (Boud et al. 2013, 2015). It is possible that the positive illusions of low-performing students arise from teachers’ reluctance to provide “truthful” feedback, thus providing misleading feedback about the quality of students’ work (Otunuku and Brown 2007). Perhaps students purposefully mislead themselves so that their self-esteem does not suffer (Boekaerts 2011; Boekaerts and Corno 2005). Alternatively, lower-performing students may lack the metacognitive skills needed to evaluate themselves accurately. Nonetheless, a positive illusion or unrealistic confidence in one’s proficiency might motivate persistent effort to learn (e.g., performance approach motivation) and greater achievement in the long run (Butler 2011). Additionally, SSA may function to clarify learning targets and support growth beyond their aided zone of proximal development (Panadero and Alonso-Tapia 2013). Consequently, support in SSA might assist such students to acquire greater knowledge about the task and SSA skills. It may also be that some combination of assessment methods (e.g., checklist, rubric), instructional support (e.g., script), and the focus of that support (e.g., acquisition of domain knowledge, performing SSA, coping with realizing one’s deficiencies, etc.) could contribute to especially helping weaker learners transition into accurate SSA. Nonetheless, this aspect of SSA is under-researched.

Furthermore, it might be that in concerning ourselves with the realism of self-assessments, we are overlooking more important effects of SSA other than its contribution to enhanced performance in a specific domain. It is possible that gains in self-regulation competence arise from SSA (Brown and Harris 2013; Panadero et al. 2012), though this is not a universal result (Dinsmore and Wilson 2015). Likewise, students gain power and experience less anxiety when using rubrics for self-assessment (Andrade and Du 2005). Improved student motivation, self-efficacy, engagement, student behavior, and quality of student-teacher relationships have all been found as a consequence of self-assessment (Glaser et al. 2010; Griffiths and Davies 1993; Munns and Woodward 2006; Olina and Sullivan 2002; Schunk 1996). Yet, would such benefits be enough or should we still expect greater learning? Our position is that an educational practice, such as SSA, must promote learning to justify its place in the curriculum.

Implications for Research

A substantial conclusion from this section is that the relationship of SSA formats to learning outcomes does not seem to be constant across all levels of learner achievement or ability. Hence, research needs to specify the SSA format and the academic ability of the studied learners so as to provide adequate guidance to teachers. Consistent with our theme of hoping to enlighten rocky and disputed shores, we make some speculative and tentative suggestions as to how SSA could be implemented to improve outcomes for all learners.

It seems probable that lower-ability students could benefit from feedback in the form of progress scores that are sensitive to small improvements in performance. Perhaps expressing performance gain in terms of percentage scores might be motivating because a small performance gain of 5 out of 100 compared to a previous score of 40 is a 12.5 % increase, although it is only 8 % of the total possible gain space above the score of 40. Even if the student’s score is below average or below requirements, a small increase may motivate students to persist, much as athletes maintain motivation by recording and displaying small increases in their speed or distance. In a related fashion, we may find greater motivation and persistence toward learning if SSA were anchored to progress and improvement relative to previous performance (i.e., ipsative judgment), rather than on comparing with classmates or peers, which might encourage “competitive SSA.” At the same time, such SSA tracking needs to be conducted against socially accepted criteria and standards, because students need external criteria to determine if their performance is meeting expectations.

The lack of consequences (whether positive or negative, high or low stakes) for being unrealistic in SSA might reduce students’ motivation to conduct realistic, verifiable SSA. Finding ways to focus students on being more realistic about their performance (e.g., Kruger and Dunning 1999) may make low achievers conscious of their poor performance and help them become more realistic. However, it is unknown whether this will have positive or negative consequences and future research needs to address this issue. Nevertheless, it is not clear what happens when overestimators become realistic, and more importantly, neither is it known how overestimators might become more accurate self-assessors.

In reviewing known heuristics that mislead students into unrealistic over- or under-confidence when making an evaluation of learning, we identified many valuable insights derived from JOL research (e.g., the belief that practice indicates lack of learning, relying on inaccurate prior knowledge, remembering previously studied items, etc.). However, being predominantly experimental laboratory studies, JOL research may not be easily replicated in classroom contexts. In addition to being difficult to carry out in naturalistic contexts, JOL research has unfortunately been isolated from classroom assessment research and discussions; hence, studies that test JOL findings in classroom settings would strengthen the generalizability of that body of research.

General Future Lines of Research

There are five areas of future research that we would like to emphasize. First, research on SSA has mostly involved students from Western countries, especially from higher education contexts. However, it should not be assumed that SSA in other cultures would take the same form and have the same effects on students (Henrich et al. 2010). Therefore, cross-cultural research and greater awareness of socio-cultural values as important contextual influences are greatly needed to establish more robustly universal principles underlying SSA.

Second, coherence in the use of terminology is another area that needs further work, especially when it comes to clarifying what “standard SSA” is. A possible study would be an international Delphi study of SSA scholars seeking clarity and consensus about the types and typologies of SSA.

Third, transferring to a greater extent, the methods and conclusions developed in the field of workplace learning to educational SSA would be of benefit. There is significant empirical evidence about how workers regulate, monitor, and evaluate their work on the job. Insights as to how workers become realistic in self-appraisal should have transfer to educational settings, especially since a goal of schooling is to prepare young people for meaningful employment.

Fourth, as mentioned previously, bringing the JOL research techniques into the classroom would provide an interesting contrast to the generally retrospective approach to SSA observed in educational studies. It may be that prospective JOL studies might lend themselves to subject domains (e.g., mathematics) or topics dominated by objective knowledge (e.g., learning terminology, vocabulary, formulae, etc.) that are regularly assessed with objective tests, such as are used in JOL research. These studies might help us understand SSA in relation to quite fine-grained content.

And fifth, as pointed out previously, more research is needed into the psychological aspects of the SSA process. Future research needs to integrate SSA procedures with simultaneous data collection about thinking (e.g., think aloud protocols) and motivational and emotional aspects, perhaps through diary study methods using previously developed self-report tools. In this regard, the latest advances in the measurement of self-regulated learning (Panadero et al., 2015) could be applied to the self-assessment field to obtain more detailed data about the self-assessment psychological processes, and area that need further development.

Conclusions