Abstract

This paper provides a comprehensive quantitative assessment of the employment performance of first- and second-generation immigrants in Belgium compared to that of natives. Using detailed quarterly data for the period 2008–2014, we find not only that first-generation immigrants face a substantial employment penalty (up to − 30% points) vis-à-vis their native counterparts, but also that their descendants continue to face serious difficulties in accessing the labour market. For descendants of two non-EU-born immigrants the social elevator appears to be broken. Indeed, estimates suggest that their employment performance is no better than that of their parents (whose penalty averages 19% points). Immigrant women are also particularly affected. While they are all found to face a double penalty because of their gender and origin, for women originating from outside the EU the penalty is generally even more severe. Among the key drivers of access to employment, we find: (1) education (especially for second-generation immigrants from non-EU countries), and (2) proficiency in the host country language, citizenship acquisition, and (to a lesser extent) duration of residence for first-generation immigrants. Finally, estimates suggest that around a decade is needed for the employment gap between refugees and other foreign-born workers to be (largely) suppressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

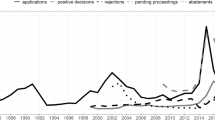

Immigration flows into OECD countries are marked by sharp fluctuations and considerable diversity between countries. Taking all countries together, however, net immigration has been consistently positive since the 1960s. The two first decades of the twenty-first century witnessed a new surge of inflows: between 2000 and 2019, the number of foreign-born residents (i.e. first-generation immigrants) in OECD countries rose by more than 60%, from 83 to 135 million people (OECD, 2020). In 2019, foreign-born individuals represented more than 10% of the OECD population, 12% on average in the European Union, 14% in the United States, and more than 20% in Canada, Australia and Switzerland (OECD, 2020). Immigration has thus become a major policy concern in many advanced economies, notably from a labour market perspective.

Belgium is a particularly interesting case study in this respect. At the beginning of the twentieth century, many foreigners entered the Belgian territory to meet the demand for low-skilled labour. Starting in the 1970s, immigrants mainly came to Belgium on family reunification visas, and since the 1990s, two new types of immigrants have gained importance: asylum seekers and undocumented workers (Martiniello & Rea, 2012). In 2019, first-generation immigrants accounted for more than 17% of the total population in Belgium (OECD, 2020), which makes this country one of the most multicultural in the OECD area (Martiniello, 2003). Unfortunately, it is also one of the worst OECD countries in terms of the employment performance of immigrants. In 2019, the employment rate among foreign-born individuals in Belgium was approximately 59% (OECD, 2020).Footnote 1 Only Greece, Mexico and Turkey had lower figures in the OECD area.

Considering foreign-born individuals as a homogenous group hides significant disparities between origins in terms of employment performance (Algan et al, 2010; Brinbaum, 2018a; Kogan, 2007; OECD, 2020; Zorlu, 2014). This is particularly the case in the EU where immigrants from other Member States benefit from simplified administrative procedures. As a result, across Europe, two distinct groups appear: on the one hand, EU-born people, whose employment rate is very close to or even higher than that of native-born people in all countries. For immigrants born outside the EU, on the other hand, access to employment is much more problematic: here, the employment rate gap was about 8% points on average in the EU in 2017. Belgium is no exception: while the gap with respect to natives was close to zero for immigrants from other EU countries, the employment rate of non-EU immigrants was 50%, almost 15% points lower than for natives.

Another concern is the labour market situation of the so-called second generation, i.e. children of immigrants. Given that the latter are born, educated and socialised in the country of residence, their relative success or failure is often seen as the ultimate benchmark of integration (Card, 2005). The standard assumption is that second-generation immigrants should fare better than their parents and ultimately ‘catch up’ with the children of native-born parents, thanks to their improved language proficiency and greater facility in getting their skills and qualifications recognised. Results for advanced economies suggest, however, that this view is somewhat too optimistic (Brinbaum, 2018a; Dustmann et al., 2010; Falcke et al., 2020; Kogan, 2007; Zorlu & van Gent, 2020). The majority of the literature supports the segmented assimilation theory, stating that second-generation immigrants might experience high levels of discrimination and downward assimilation (e.g. Portes & Rumbaut, 2001; Portes & Zhou, 1993).Footnote 2 More precisely, estimates generally show divergent intergenerational mobility patterns between different ethnic groups, with children of immigrants from poorer countries being less likely to outperform their parents (Algan et al., 2010; Brinbaum & Guégnard, 2013; Liebig & Widmaier, 2009).

The second generation of immigrants is not systematically included in the databases. The latest data available for international comparison were produced in 2014 with the ad hoc module of the Labour Force Survey that followed the first ad hoc module on the labour market situation of migrants, conducted in 2008. In 2014, Belgium had the second largest employment gap between natives and second-generation immigrants, just behind Greece, and the seventh lowest employment rate. Moreover, in comparison with other countries, Belgium shows little improvement from first- to second-generation immigrants, with an increase of 3% points compared to 6% points in Germany, 9% in France and even 12% in Sweden.

Note that comparison among EU countries is relatively difficult because of the wide variations between countries in terms of immigration history. Some countries have a very small percentage of second-generation immigrants in their population, which may bias the results or make the countries less comparable to Belgium. This is the case for Romania (0.1%) and Bulgaria (0.3%), but also for Greece (1%) and Finland (1%). Luxembourg, for example, is also a special case as only 32% of its population was native in 2014, with 51% being first-generation immigrants and 14% second-generation immigrants. Countries such as Estonia or Latvia have a higher proportion of second-generation immigrants, with more than 20% of their population having at least one foreign-born parent. In 2014, according to these data, 72% of Belgium’s population was born in Belgium with both parents also born in Belgium, 17% were born abroad and 10% had at least one foreign-born parent. Even taking into account the heterogeneities between countries, if we compare Belgium’s performance with Sweden, the country with the most similar proportion of immigrants to Belgium (69% natives, 20% first-generation immigrants and 10% second-generation immigrants) and which also has the most similar gap in terms of first-generation immigrants, Belgium falls far short of Sweden’s performance for the second generation. The employment rate of second-generation immigrants in Belgium was 59%, 12% points lower than that of native-born, compared to 80% in Sweden or 4% points lower than that of native-born.

It is not only Belgium’s poor performance in labour market integration of (both first and second generation) immigrants that makes it an interesting case study, but also the availability and richness of its administrative database: in the Crossroads Bank for Social Security (CBSS), first- and second-generation immigrants can be identified and separated into 11 origin groups.Footnote 3 Based on these administrative data merged with the 2008 and 2014 ad hoc modules of the Labour Force Survey (LFS), our paper aims to get a better understanding of the relationship between people’s migration background and their likelihood of being employed in Belgium. This linked LFS-CBSS dataset provides longitudinal information on a nationally representative sample of workers (aged 15 and over) for all quarters between 2008 and 2014. As it contains detailed information on the labour market situation of immigrants and their immediate descendants, it is particularly well suited to investigate, ceteris paribus, how first- and second-generation immigrants fare in comparison with their native counterparts. More precisely, this dataset enables us to analyse whether the children of immigrants perform better than their parents and whether they are able to catch up with the children of native-born parents in terms of access to employment. Particular attention is devoted to immigrants’ specific geographical areas of origin. We are thus able to assess whether intergenerational mobility patterns differ across ethnic groups. Moreover, we test whether the employment outcomes of first- and second- generation immigrants vary depending on their gender and level of education. We thus address the following questions: (1) “Do immigrant women face a double employment penalty?”, (2) “Is education an effective tool for reducing the native-immigrant gap?”, and (3) “Are intergenerational ethnic inequalities more persistent among women and lower educated immigrants?”. Furthermore, we study whether the origin of both parents is important in explaining the employment performance of second-generation immigrants. More precisely, we examine the following issues: (1) “Are descendants of immigrants better off when only one of their parents is foreign-born?”, (2) “Is it more detrimental to have two foreign-born parents originating from industrialised countries or to have only one parent born in a developing economy?”, and (3) “Is the father’s country of birth more harmful than that of the mother?”. Finally, as regards first-generation immigrants, beyond the impact of having a tertiary degree and being a woman (see above), we also investigate the role of various other moderators likely to affect their access to employment. These moderators include the duration of residence, citizenship acquisition, the main reason for migration, and proficiency in the host country language.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. The next section provides an overview of the literature regarding the labour market integration of first- and second-generation immigrants. In Sects. 3 to 5, we present our dataset, methodology, and descriptive statistics. The results from our econometric investigation are shown and discussed in Sect. 6. The last section concludes.

2 Literature Review

2.1 First-Generation Immigrants

The literature on the employment performance of first-generation immigrants in Belgium is quite limited, though more extensive than that on the second generation (see next section). The employment gap between first-generation immigrants and native-born people in Belgium is one of the largest in the OECD area (FPS Employment and Unia, 2017). Past research has shown that this gap remains largely unexplained after controlling for human capital and other socio-demographic characteristics (De Keyser et al., 2012; High Council for Employment, 2018; Martens et al., 2005). Using the Labour Force Survey (LFS) for the years 1996 to 2008, Corluy and Verbist (2014) further show that this unexplained employment gap is most pronounced when comparing natives to immigrants born outside the European Union (EU).Footnote 4

Although personal characteristics cannot entirely explain the employment gap, they have different implications for labour market integration depending on people’s origin. Studying gender discrimination in interaction with workers’ origin, Bentouhami and Khadhraoui (2018) showed that unlike Belgian women, for whom a gender gap emerges gradually in their career path, (non-EU) foreign women face a gender gap immediately through downgrading or over-qualification (in the health sector, for example) or through factors which prevent them from joining the labour market (such as family responsibilities, especially for single mothers, or specific rules regarding the wearing of headscarves). Algan et al (2010), studying immigrants’ employment performance in France, Germany and the United Kingdom, also found larger employment gaps for immigrant women, reaching almost 34 and 46% points for Turkish women in Germany and in France respectively and even 54 to 56% points for Pakistani and Bangladeshi women in the UK compared to native women. It is suggested that lower employment rates among female immigrants may be due to more traditional gender roles (Blau et al., 2011; Lesthaeghe & Surkyn, 1995). Disentangling this explanation from the discrimination story remains particularly difficult. The point is that immigrant women might indeed face statistical discrimination in their access to employment, as employers may expect them to be less committed to their jobs due to stronger family obligations (Baert et al., 2016).

For all, a higher level of education improves access to the labour market but is not sufficient to close the employment gap with respect to natives. Conversely, this gap is even larger for highly educated immigrants, not only in Belgium but also in other EU countries (High Council for Employment, 2018). Despite the recognition of diploma and skills, there is plenty of evidence that the labour market attributes a lower value to education and experience acquired by immigrants outside the host country (Arbeit & Warren, 2013; Nordin, 2007; OECD, 2007, 2014). This leads to mismatches in the labour market and to a higher proportion of immigrants being over-education compared to natives (i.e. to have a higher level of education than that required for the job) and this is particularly marked among highly educated immigrants (Fernandez & Ortega, 2006; Jacobs et al. 2021).

The role of job-finding networks has been highlighted in studies on the native-immigrant employment gap in countries such as France and the United States (Brinbaum, 2018b; Fernandez & Fernandez-Mateo, 2006), but no similar analysis has been conducted on Belgium so far. Note, however, that those networks are not always beneficial to immigrants especially if they provide only limited, lower-paid job opportunities or if they induce immigrants to stay in their network and disregard other potential jobs (Drinkwater, 2017; Kalter & Kogan, 2014).

Immigrants’ lack of human and cultural capital specific to the host country may gradually improve with the number of years of residence, for example if they learn the language(s) and how the labour market operates, follow training or gain local work experience. Altogether, this could help them to increase their chance of integration on the labour market. As regards the duration of residence, the results from the High Council for Employment (2018) suggest that it has a positive impact on the employment of non-EU-born immigrants. The moderating role of language proficiency has, to our knowledge, not been tested in the Belgian context. However, without a good knowledge of the host country language, it is very likely that first-generation immigrants will struggle to have their skills and qualifications recognised and hence to find a job (Chiswick & Miller, 2014).

Another factor which can positively influence the labour market outcomes of immigrants is citizenship acquisition. Using the LFS for the year 2008, Corluy et al. (2011) find that naturalisation is associated with significantly better employment outcomes among non-Western immigrants, even after controlling for the number of years of residence since migration.Footnote 5 As for the main reasons for migration, results suggest that refugees and “family-reunification” migrants have significantly lower employment probabilities than economic migrants and the native-born (High Council for Employment, 2018; Lens et al., 2018). Moreover, Lens et al. (2019), using labour market trajectories of people who arrived in Belgium between 2003 and 2009, show that refugees take significantly more time than other groups of migrants before entering their first job. In addition, they find that refugees are more likely to exit their first employment and fall into unemployment or social assistance.

2.2 Second-Generation Immigrants

Evidence regarding the employment performance of second-generation immigrants in Belgium vis-à-vis their parents and the children of native-born parents (i.e. natives) is still surprisingly scarce.Yet, findings suggest that their employment penalty is sizeable (Corluy et al., 2015; FPS Employment and Unia, 2017; Liebig & Widmaier, 2009). This situation notably results from much larger differences in educational outcomes in Belgium between second-generation immigrants and the children of native-born parents, in comparison with most other OECD countries (Pina et al., 2015; Crul et al., 2003).Footnote 6 However, recent evidence for Belgium also suggests that substantial employment gaps are still recorded between second-generation immigrants and natives after controlling for educational attainments (Corluy et al., 2015; De Cuyper et al., 2018; FPS Employment and Unia, 2017). A similar outcome has been found in other countries such as France, Germany or the United Kingdom (Algan et al., 2010; Dustmann et al., 2010; Kogan, 2007). Moreover, focusing on recent university graduates in applied sciences in the Netherlands, Falcke et al. (2020) show a clear ethnic penalty in getting a job for non-western (second-generation) immigrants even after controlling for individual characteristics, average grades or previous education.

To our knowledge, the only in-depth econometric investigation comparing access to employment for natives, first- and second-generation immigrants in the whole Belgian economy has actually been undertaken by Corluy et al. (2015). The authors rely on data from the 2008 ad hoc module of the Labour Force Survey, merged with administrative records. Their results show, in addition to the above-stated outcome, that: (1) employment rates for children of immigrants are not much better than for their parents, and (2) employment outcomes vary considerably by country of origin. In a more recent exercise, De Cuyper et al. (2018) have merged data on job seekers from the VDAB (Flanders’ Public Employment Service) and the CBSS (Crossroads Bank for Social Security) over the period 2008–2012. Their findings, relative to the Flemish region, show that exit rates to employment of second-generation non-EU immigrant job seekers are lower than for natives, even after controlling for differences in socio-economic characteristics, such as the educational level.Footnote 7

In sum, most of the literature studying the employment performance of immigrants in Belgium focuses on first-generation immigrants. In other words, very few studies distinguish between second-generation immigrants and children of native-born parents (i.e. natives). Moreover, they provide little evidence on how first-generation immigrants (potentially interacted with moderators) fare vis-à-vis the second generation. Various issues thus remain unaddressed. For instance, we have neither estimates on the employment gaps between first-generation immigrants split by main reason of migration and the second generation, nor on whether these gaps decrease as first-generation immigrants’ duration of residence increases. Last but not least, the above-cited studies devote little attention to whether moderating factors have the same effects on all ethnic groups. As a consequence, several key questions for public policy still need to be explored.

In this paper, we aim to address these shortcomings by providing a comprehensive and up-to-date quantitative analysis of the employment performance of first- and second-generation immigrants compared to the children of native-born parents. We also add to the existing literature by investigating, in depth, the role of a large range of moderators (including gender, education, parents’ countries of birth, duration of residence, naturalisation, main reason for migration, and command of the host country language) and by systematically examining whether employment gaps and intergenerational mobility patterns vary depending on immigrants’ ethnic origin.

3 Data

Our empirical analysis is based on an original dataset derived from the merging of the ad hoc modules of the Labour Force Survey (ad hoc LFS) with data from the Crossroads Bank for Social Security (CBSS). More precisely, the LFS ad hoc samples relative to the second quarters of 2008 and 2014 have been enriched with information from the CBSS for all quarters from 2008:Q1 to 2014:Q4. The number of people surveyed in the LFS ad hoc modules stands at 24,522 for 2008:Q2 and 24,610 for 2014:Q2. Only 71 people appear in both modules. Our combined LFS-CBSS dataset thus provides longitudinal information on 49,061 individuals over 28 quarters, i.e. on 1,373,708 individual-quarter observations. It is representative of people aged 15 and over in Belgium over the period 2008–2014.

Our merged dataset is particularly well suited to study how people’s origin affect their likelihood of being employed. The CBSS contains detailed information on people’s labour market status (i.e. whether they are employed, unemployed, or inactive), country of birth and nationality (both at the time of the survey and at birth), duration of residence, parents’ countries of birth, alongside demographic characteristics (such as gender and age) and other variables (such as the region of residence). As information on people’s level of education in the CBSS is quite imperfect, it has been obtained from the LFS.Footnote 8 This implies that information on people’s highest level of education is only available in 2008:Q2 for about half of the sample and in 2014:Q2 for the other half. This information has been imputed to all quarters, i.e. from 2008:Q1 to 2014:Q4, assuming people’s highest educational attainments remained constant over the investigation period. To ensure that this assumption is relevant, we restricted our sample to people aged between 30 and 64, namely those who were most likely to have completed their studies at the time of the survey. Besides education, the LFS ad hoc modules contain information on important moderators of the relation between origin and employment. They notably include the main reason for migration. This self-declared variable indicates whether migrants’ main purpose for coming to Belgium was related to: (1) employment, (2) family reasons, (3) study, or (4) international protection/asylum. Among other variables, the ad hoc LFS also provides information on migrants’ proficiency in the host country language.

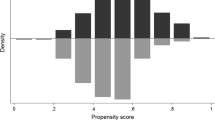

Dropping individuals younger than 30 and those older than 64 reduces the size of our sample by more than half, to around 673,000 individual-quarter observations. Further cleaning of the data (especially due to missing information on people’s highest level of education and on the country of birth of at least one of their parentsFootnote 9) results in a final sample of 538,412 observations, that is of 19,229 people observed over 28 quarters from 2008:Q1 to 2014:Q4.

4 Methodology

To gain a better understanding of how people’s migration background affects their likelihood of being employed, we estimate the following probit model:

where \({\Phi }\left( . \right)\) denotes the standard normal density, such that:

The dependent variable in Eq. (1), Ei, is a dummy taking the value 1 if the individual i (at quarter t) is employed, and 0 otherwise (i.e. if the individual is unemployed or inactive). Our main variable of interest, included in the vector Xi, is the ‘migration status’ of a person. Depending on this person’s country of birth and on that of her/his parents, she/he is classified in one of the following groups: (1) ‘Native-born with native background’ (i.e. people born in Belgium from Belgian-born parents), (2) ‘Second-generation immigrants’ (i.e. people born in Belgium with at least one foreign-born parent), and (3) ‘First-generation immigrants’ (i.e. people born outside Belgium). The reference category, in the regression analysis, is the group of ‘Native-born people with a native background’ (further referred to as ‘Natives’).

First-generation immigrants are divided into groups according to their EU or non-EU origin. We also compare the employment outcomes of those born in the EU-14 (i.e. in countries who were part of the EU before 2004, Belgium excluded) with those born in another EU country (i.e. in a country that joined the EU from 2004 onwards) and split people born outside the EU according to whether they were born in: (1) other European countries, (2) EU candidate countries, (3) the Near or Middle East, (4) other Asian countries, (5) the Maghreb, (6) other African countries, (7) the Far East or Oceania, (8) North America, and (9) South or Central America.Footnote 10

To determine the origin of second-generation immigrants, following common practice (Corluy et al., 2015; FPS Employment and Unia, 2017), the order of priority is based on the father’s country of birth.Footnote 11 Put differently, the father’s country of birth is used to define the origin of a second-generation immigrant, except if the father was born in Belgium and the mother abroad. In that case, the mother’s country of birth is retained. Second-generation immigrants from the EU are split according to whether they originate from the EU-14 or another EU country. For those originating from non-EU countries, we distinguish nine groups: (1) other European countries, (2) EU candidate countries, (3) the Near or Middle East, (4) other Asian countries, (5) the Maghreb, (6) other African countries, (7) the Far East or Oceania, (8) North America, and (9) South or Central America.

The vector Xi also contains a set of control variables. Following common practice, the latter includes a dummy for gender, 6 dummies for people’s age, 2 dummies for their level of education, 2 dummies for the region in which they are living, and 27 quarter-year fixed effects.

5 Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the breakdown of the population by origin’s groups. We find that the native population represents almost 71% of our sample, whereas 10% are second-generation immigrants and around 19% first-generation immigrants. Most second-generation immigrants originate from EU-27 countries, and especially from the EU-14. Nevertheless, around one-fifth of them have a non-EU origin, with the bulk of these people having at least one parent born in the Maghreb, other African countries or EU candidate countries. As for first-generation immigrants, almost half of them were born in the EU-27 (7.6% in the EU-14 and 1.4% in countries that joined the EU after 2004). The other half, born outside the EU, comes primarily from the Maghreb (3.2%), other African countries (2.3%), and EU candidates (1.3%).

First column of Table 2 presents summary statistics for all variables included in our econometric analysis for the whole population. The results show that, on average, 70% of people in our sample had a job during the investigation period (i.e. 2008:Q1–2014:Q4). The remaining 30% were thus either unemployed or inactive. Further descriptive statistics show that the people in our sample, aged between 30 and 64, are quite equally distributed across age groups, though their incidence is somewhat smaller in the youngest and oldest age categories. The proportion of women stands at almost 51%, the share of tertiary educated people is close to one-third, and 38% of people live in Wallonia compared to 50% in Flanders and 12% in Brussels.

To examine potential differences between natives, first- and second-generation immigrants, descriptive statistics by worker origin are presented in column 2 to 6 of Table 2. Concerning the employment rate, we observe that it is around 74% among natives, between 68 and 65% among second-generation immigrants (depending on whether they originate from the EU-27 or not) and just under 50% among first-generation immigrants. The proportion of women is similar in all categories of workers, at around 50%. The age distribution is also fairly comparable across groups, with about a quarter of workers aged 30–39, half aged 40–54, and the remaining quarter aged 55–64. However, the second generation of non-EU immigrants is much younger: most of them (61%) are under the age of 40 and only 6% are over 54. Moreover, we find that the proportion of low-educated people (i.e. people with at most a lower secondary education) is higher among immigrants (especially among immigrants born outside the EU) than among natives.Footnote 12 Finally, with respect to the region of residence, while immigrants are found to be under-represented in Flanders (relative to the share of natives living in that region), the opposite result is observed in Brussels (especially among non-EU immigrants). In Wallonia, the situation is mixed: while EU immigrants are over-represented in this region, those from outside the EU are under-represented.

In order to assess the representativeness of our sample, we first compared the distribution of people by origin in our data set (see Table 1) with that of the entire population aged between 30 and 64 in Belgium over the period 2008–2014Footnote 13 (see “Appendix 1”). The results show that the two distributions are very similar. Indeed, differences in the incidence of workers by origin are very modest. The ‘largest’ difference concerns the share of natives. However, it barely exceeds 1% point (i.e. 70.7% in our sample vs. 71.8% in the overall population). Next, we compared descriptive statistics by origin computed respectively from our sample (see Table 2) and from the entire corresponding population (see “Appendix 2”). Overall, this analysis once again confirms the representative nature of our sample. However, some small differences are worth noting. For instance, it should be highlighted that the employment rates of both natives and immigrants born outside the EU are slightly higher (by around 2% points) in our sample than in the overall population. Furthermore, it appears that low-educated people (i.e. people with at most a lower secondary education) are somewhat under-represented in our data.Footnote 14 The share of men is also slightly lower (by between 0.1 and 2.9% points depending on their origin) in our sample than in the whole corresponding population. Finally, while people living in Brussels and Wallonia are found to be slightly over-represented in our data, the opposite observation can be made for Flemish residents. In the end, while keeping these small differences in mind, we can nevertheless conclude that our sample is broadly representative of the entire population aged 30–64 in Belgium in the years 2008–2014.

6 Empirical Results

6.1 Benchmark Estimates

The marginal effects from our benchmark probit regression—see Eq. (1)—are reported in Table 3.Footnote 15 Our estimates show the employment gaps between individuals with different migration statuses, after controlling for gender, age (6 dummies), education (2 dummies), region of residence (2 dummies), and quarter-year fixed effects (27 dummies). Natives are chosen as the reference category. Differential employment probabilities, respectively for aggregated and disaggregated groups of first- and second-generation immigrants, are reported in columns (1) and (2).

The regression coefficients associated with covariates have the expected sign and are highly significant. They show that women are, ceteris paribus, 11% points less likely to have a job than men. Employment probabilities are also found to be lower among older age groups and especially among people aged 60 or more. The employment rate increases significantly with the level of education and is the highest (lowest) in Flanders (Wallonia).

Regarding our main variable of interest, i.e. the ‘migration status’ of a person, the estimates are quite clear-cut: natives are found to have, ceteris paribus, a significantly greater employment probability than first- and second-generation immigrants. The employment penalty is overall higher for people born outside Belgium than for those born in Belgium with at least one foreign-born parent.Footnote 16 Among second-generation immigrants, access to employment is the lowest for those of non-EU origin (− 13% points compared to natives) and especially for those originating from an EU candidate country (− 14% points) or from the Maghreb (− 20% points). Among first-generation immigrants, the penalty is only slightly more pronounced among those born outside the EU than among those born in the EU.Footnote 17 However, as shown in column (2), employment penalties vary substantially among those born outside the EU.They are somewhat lower for those born in other Asian and other African countries (− 10 and − 13% points, respectively) and substantially higher for those born in EU candidate countries (− 21% points), the Maghreb (− 21% points), other European countries (− 24% points) and, in particular, the Near or Middle East (− 30% points).Footnote 18

When comparing employment probabilities of first- and second-generation immigrants coming from the same geographical area, results are mixed. The penalty decreases for instance substantially for second-generation immigrants originating from other European countries (from − 24 to − 12% points). In contrast, the decrease is less significant for people originating from EU candidate countries (from − 21 to − 14% points) and remains almost unchanged for those of Maghrebin origin. Indeed, the employment penalty for people born in the Maghreb stands at − 21% points, whereas that for people born in Belgium with a least one parent of Maghrebin origin is equal to − 20% points.Footnote 19

6.2 The Role of Demographics and Parents’ Countries of Birth

In this section, we examine the moderating role of gender and education in the relationship between employment and migration status. We also investigate whether the countries of birth of both parents are equally important for explaining the employment performance of second-generation immigrants.

6.2.1 Does Gender Matter?

Our estimates so far indicate that the likelihood of having a job is, ceteris paribus, much lower for immigrants than for natives. The same is found for women in comparison with men. The question whether immigrant women face a double penalty hence deserves to be investigated. To this end, we re-estimated Eq. (1) separately by gender.

The results, reported in Table 4, first show that employment probabilities are significantly lower for immigrants, both women and men, compared to their same-sex native counterparts. Among men, the penalty is more pronounced for first- than for second-generation immigrants, as shown in columns (1) and (2). Yet, while the sons of immigrants from other African countries fare much better than their fathers (0 vs. − 13% points), the intergenerational mobility pattern is almost flat for those from EU candidate countries (− 13 vs. − 14% points), and even slightly negative for those from the Maghreb (− 17 vs. − 15% points).

As regards gender, our estimates show that the penalty is about the same for female and male (first- and second-generation) immigrants originating from the EU. In contrast, the penalty is systematically higher for female than for male immigrants originating from outside the EU (except for people from other African countries). Among second-generation immigrants, gender differences are particularly striking among people from the Maghreb (− 22 vs. − 17% points) and more limited for those from EU candidate countries (− 15 vs. − 13% points). Among first-generation immigrants, the penalty for women is often almost twice as high as that for men. This is notably the case for people from the Near and Middle East (− 41 vs. − 23% points), the Maghreb (− 29 vs. − 15% points), and EU candidate countries (− 28 vs. − 14% points).

Overall, the estimates suggest that (first- and second-generation) immigrant women of EU origin face a double penalty.Footnote 20 For those of non-EU origin (excluding other African countries), the penalty is even more pronounced: it outweighs the sum of both penalties, namely being an immigrant and being a woman.

6.2.2 Does Education Matter?

Education substantially improves people’s access to employment (as shown in Table 3). Yet, considering the existing literature (Corluy & Verbist, 2014; Damas de Matos and Liebig, 2014), it is unlikely that all people benefit equally from their educational credentials. Accordingly, it is worth investigating whether and how the employment gap between natives and immigrants depends on the latter’s level of education. To examine this issue, we re-estimated our benchmark equation separately for people with at most a degree from higher secondary education and for tertiary-educated individuals.

The results, reported in Table 5, show that the penalty is limited (up to 6% points) for second-generation immigrants of EU origin, regardless of their level of education. For the children of non-EU-born immigrants, things are quite different: the immigrant-native employment gap among the lower-educated is almost twice as big as that among the tertiary-educated (− 16 vs. − 9% points). Higher education thus has a substantial positive impact on the latter’s labour market integration. It not only favours their access to employment but also reduces their penalty compared to natives with the same degree. Yet, education does not appear to be the whole story: the penalty for tertiary-educated people originating from outside the EU is still found to be substantial, particularly for those originating from the Maghreb (− 13% points compared to tertiary-educated natives).

Among first-generation immigrants, the results show that the penalty is quite substantial overall. For those born in the EU, the employment gap is more pronounced among tertiary-educated people (− 24 vs. − 14% points). This may be explained by the difficulty for them to get their diplomas or certificates recognised by the Belgian authorities (particularly for Eastern European graduates who migrated to Belgium before 2004) and their greater reluctance to accept (or greater difficulty in obtaining) manual/low-skilled jobs, e.g. in the construction, cleaning or transport industries.Footnote 21 Proficiency in the host country language might also play a role (see our estimates in Sect. 6.3.4). For immigrants born outside the EU, the employment gap reaches 19% points for both those with at most higher secondary and tertiary education. On average, education is thus found to improve the latter’s labour market integration.Footnote 22 However, it does not reduce their (substantial) employment gap with respect to natives.Footnote 23

6.2.3 Do the Countries of Birth of Both Parents Matter?

Our benchmark estimates, reported in Table 3, show that natives have a significantly higher employment probability than people born in Belgium with at least one foreign-born parent, especially if the latter originates from a non-EU country. This outcome raises several questions: (1) “Is the penalty encountered by second-generation immigrants higher when both parents, rather than only one, are foreign-born?”, (2) “Is it more detrimental to have two foreign-born parents from the EU-27, or to have only one parent born outside the EU?”, (3) “Is the father’s country of birth more harmful than the mother’s?”. To address these questions, we re-estimated Eq. (1) focusing on the countries of birth of both parents of second-generation immigrants.

The results are reported in Table 6. Our estimates in column (1) show that second-generation immigrants face a weak penalty (up to − 4% points) when they have only one foreign-born parent, regardless of whether that parent originates from a EU-27 country or from outside the EU.Footnote 24 In other words, having one parent born in Belgium helps second-generation immigrants to get access to employment through a better social network, acquisition of cultural capital specific to Belgium, and some knowledge of the functioning of the labour market. The employment penalty is almost doubled when both parents were born in the EU-27 and is multiplied by five in the case of two parents born outside the EU. We observe indeed that, for those born in Belgium with two non-EU-born parents, the employment gap stands at − 21% points. Strikingly, this gap is of the same order of magnitude as the one for first-generation immigrants born outside the EU (estimated at − 19% points).Footnote 25

The results presented in columns (2) and (3) of Table 6 enable us to assess which parent’s country of birth (i.e. the mother’s or the father’s) is more relevant for the employment prospects of second-generation immigrants. Our estimates show that the employment penalty for people born in Belgium with only one foreign-born parent, originating either from the EU-27 or from outside the EU, is modest (of at most − 4% points), regardless of which parent was born abroad.Footnote 26

Overall, our findings thus highlight that the employment gap for second-generation immigrants is only critical when both parents were born abroad, particularly outside the EU. For people with only one foreign-born parent, the gender of the parent born abroad appears to be of minor importance.

6.3 Drivers of First-Generation Employment Outcomes

In this section, we examine a series of moderators likely to affect the employment outcomes of first-generation immigrants. We focus in turn on the duration of residence, the acquisition of the Belgian nationality (by duration of residence), the main reason for migration (by duration of residence), and the degree of command of the host country language.

6.3.1 Does the Duration of Residence Matter?

The benchmark estimates indicate that, all else equal, the employment rate is the lowest for foreign-born people. Knowing whether this outcome is mainly driven by immigrants’ initial difficulty in finding a job or whether it reflects a more persistent phenomenon is key to assess the severity of the situation. Therefore, we re-estimated Eq. (1) taking the duration of residence of first-generation immigrants explicitly into account. The results, reported in Table 7, enable us to compare the situation of natives with that of: (1) second-generation immigrants, and (2) foreign-born people with varying durations of residence (going from at most one year to over 35 years).

As expected, our estimates show that the employment penalty is, ceteris paribus, the highest for those who have been living in Belgium for at most one year. For people born in the EU-27, this penalty reaches − 32% points, compared to − 39% points for those born outside the EU. The situation is less detrimental for people with a longer duration of residence.Footnote 27 However, for people who have been living in Belgium for any duration between 10 and 20 years, the penalty is still above 19% points (regardless of whether they were born inside or outside the EU), and around 7 to 10% points after 35 years of residence. Our findings thus suggest that the pace of improvement is rather slow on average. However, we also find it to be quite heterogeneous. After 10 years of residence,Footnote 28 the penalty drops from − 22 to 0% points for people born in other Asian countries and is divided by more than 2 (from − 21 to − 9% points) for those coming from other African countries. In contrast, the penalty remains quite persistent for people born in the Maghreb and EU candidate countries: those who have been living in Belgium for more than 10 years (35 years) still encounter a penalty of around 18% points (of between 15 and 17% points). The employment gap for people born in other European countries and the Near or Middle East also remains at a high level after more than a decade of residence in Belgium (− 17 and − 24% points, respectively).

6.3.2 Does Naturalisation Matter?

A related issue is whether citizenship acquisition is associated with better employment outcomes for immigrants. To investigate this question, we re-estimated our benchmark equation splitting first-generation immigrants according to whether or not they had acquired the Belgian nationality and according to their duration of residence in Belgium. We considered the following thresholds for the duration of residence: 5 to 15 years, 16 to 30 years, and more than 30 years (see Table 8). These thresholds have been chosen to ensure that: (1) each category includes a sufficient number of data points to guarantee statistical relevance, and (2) the subdivisionFootnote 29 is coherent with the Belgian Nationality Code.

The time span of our study (2008–2014) mostly fits with a period during which Belgian nationality acquisition was quite easy.Footnote 30 Access to citizenship was basically open to all immigrants with a minimum period of lawful residence in the country. Until 2013, no specific requirements in terms of integration or knowledge of languages had to be fulfilled. Belgian’s liberal naturalisation policy was designed as a tool for fostering immigrants’ social inclusion and employment prospects. Since 2013, the logic has been reversed: the Nationality Code now specifies that immigrants have to demonstrate their social integration and, to some extent, labour market attachment in order to obtain the Belgian nationality.Footnote 31 So far, the nexus between citizenship take-up and immigrants’ labour market status has been essentially studied in countries with relatively strict acquisition rules (Fougère & Safi, 2009; Gathmann & Keller, 2018). Our study thus provides a valuable contribution to the existing literature by studying this issue in a more liberal context.

According to our data, the great majority of immigrants living on the Belgian territory during the period 2008–2014 who took up the Belgian nationality were previously non-EU nationals. Their proportion is well in excess of their share in the foreign population.Footnote 32,Footnote 33 The reason probably lies in the greater difficulty that third-country nationals encounter when they do not have the Belgian nationality, in contrast to EU nationals benefitting from the advantages of the EU membership. In particular, regarding the labour market, it should be noted that government jobs in Belgium are not open to people who do not have the nationality of an EU country.

Is citizenship take-up associated with higher employment performance among first-generation immigrants? The probit estimates, reported in Table 8, support this claim: they show that naturalised foreign-born people (originating from inside or outside the EU) have higher employment rates than their opposite numbers who did not acquire the Belgian nationality. This effect remains after controlling for the number of years of residence since migration (see columns 3 to 5 of Table 8), which supports the existence of a significant citizenship premium.Footnote 34

Among immigrants who have been living in Belgium for any duration between 5 and 15 years, this premium is estimated at 8 and 6% points for those born respectively inside and outside the EU. For those born in the EU-27, this premium remains quite stable as the duration of residence increases. In contrast, for those born outside the EU, it rises steadily and reaches 14% points for those who have been living in Belgium for more than 30 years. This outcome is due to the fact that the employment penalty for people born outside the EU and not naturalised does almost not decrease (compared to natives) as the time spent in Belgium increases. In contrast, the penalty decreases for all other categories of first-generation immigrants as their duration of residence increases.Footnote 35

6.3.3 Does the Main Reason for Migration Matter?

Migrants’ main reason for settling down in Belgium is another important moderator that needs to be tackled.Footnote 36 According to our data, among the immigrants born outside the EU and living on the Belgian territory between 2008 and 2014, around 45% declared that they came to Belgium for family reunification, 15% for a job,Footnote 37 6% for schooling, and 15% for international protection.Footnote 38, Footnote 39 For those born in the EU-27, although family-related reasons are still the main self-declared motive (40%), work-related reasons are now cited by almost 25% of them.Footnote 40

To investigate whether and how immigrants’ employment prospects are related to the main reasons that brought them to Belgium, we re-estimated Eq. (1) by splitting first-generation immigrants, born respectively in the EU-27 and outside the EU, according to whether their main declared reason for coming to Belgium was: (1) employment, (2) family reunification, (3) schooling, (4) international protection or asylum, or (5) other reasons. Moreover, to find out whether access to employment for these different groups of immigrants improves over time, our model has been estimated for varying durations of residence: less than 5 years, between 5 and 10 years, and more than 10 years.

Our results are presented in Table 9.Footnote 41 Among immigrants born outside the EU who have been in Belgium for at most 5 years, we find that the employment penalty is the highest for refugees (− 35% points),Footnote 42 somewhat smaller for those coming for family reunification (− 32% points), and the smallest for economic migrants (− 23% points). The penalty decreases for all groups of immigrants as their duration of residence increases, but not at the same pace. After more than 10 years of residence in Belgium, the ranking is substantially modified: the penalty becomes equivalent for refugees and economic migrants (around − 14% points) and somewhat greater for family-reunification migrants (− 17% points). This outcome appears to be in line with the assumption that refugees have stronger incentives to invest in the host country’s own human capital, which in turn fosters their labour market integration (Cortes, 2004). Our results show that, among immigrants born in the EU-27, the penalty is initially higher when the main reason for migrating to Belgium is related to family instead of employment (− 32 vs. − 17% points). In addition, we find that this penalty decreases for both groups of immigrants as their duration of residence increases: their penalty stands between 11 and 12% points after more than 10 years of residence in Belgium.

6.3.4 Does Proficiency in the Host Country Language Matter?

A growing literature suggests that immigrants’ proficiency in the host country language is key to their social and economic integration (Bleackley & Chin, 2004, 2010; Chiswick, 1991; Dustmann & Fabbri, 2003). However, some results also highlight that many immigrants have a hard time learning and speaking the destination language (Isphording, 2015). According to our data, this is also the case in Belgium. Descriptive statistics show that around 40% of immigrants born outside the EU have no more than intermediate skills in one of Belgium’s three official languages (i.e. Dutch, French and German) and around 20% have at most beginner skills.Footnote 43 Yet, the results are not homogeneous across countries of birth. While the share of people with at most beginner skills is moderate (i.e. below 20%) among immigrants from the Maghreb and particularly among those from other African countries, it reaches between 30 and 50% among immigrants originating from the Near and Middle East, EU candidate countries, other European countries, and Asian countries.

On average, host language proficiency is less of a concern among immigrants born in the EU-27: less than 10% have no more than beginner skills, two-thirds have intermediate skills, and for more than 20%, the host country language corresponds to their mother tongue. However, it should be highlighted that the incidence of people with at most beginner skills is much smaller among those born in the EU-14 than in other EU countries (5 vs. 33%).

Finally, descriptive statistics show that immigrants’ host language proficiency improves with years of residence. The share of people with at most beginner skills among EU-27 immigrants plummets to 3% after 10 years of residence in Belgium. For non-EU-born immigrants, this figure stands at 14%, on average. Yet, among those born in the Maghreb (EU candidate and other European countries) who have been living in Belgium for more than a decade, the share of beginners still reaches 18% (more than 25%).

How do skills in the host country language interact with immigrants’ access to employment? To examine this issue, we re-estimated our benchmark equation splitting first-generation immigrants according to their proficiency in the host country language. We distinguished between immigrants having at most beginner skills and those with at least an intermediate level. Our results, presented in Table 10, are in line with our expectations. Indeed, they show that immigrants that are more literate in the host country language are significantly more likely to have a job. This outcome is valid both for people originating from the EU-27 and from outside the EU. However, the benefits of language proficiency are found to be substantially greater for the latter.Footnote 44 The employment penalty for people born outside the EU (compared to natives) drops from − 33 to − 17% points when having at least intermediate skills, and to − 11% points when the host country language matches their mother tongue. At a more disaggregated level, we find that the gains are particularly pronounced for those originating from EU candidate countries and somewhat smaller for people from the Maghreb and other European countries.Footnote 45

To sum up, our results suggest that host language proficiency is a key driver of access to employment, especially for non-EU-born immigrants. While language skills are useful in the recruitment process and in meeting employers’ requirements, they could also help immigrants in all administrative procedures (which are complex in Belgium) and especially in accessing activation policies or training, for example.

7 Conclusion

Belgium is one of the most multicultural country in the OECD. First- and second-generation immigrants together account for around 35% of the total working-age population (BCSS, 2019; FPS Employment and Unia, 2017). At the same time, Belgium is often depicted as one of the worst OECD countries in terms of immigrants’ access to employment (OECD, 2020). Yet, econometric evidence on the relationship between people’s migration background and their likelihood of being employed in Belgium is still quite limited.

Almost all studies devoted to the Belgian economy focus on first-generation immigrants only (Corluy et al., 2011; Corluy & Verbist, 2014; De Keyser et al., 2012; High Council for Employment, 2018; Lens et al., 2018, 2019). They provide estimates of the employment penalty of foreign-born people vis-à-vis the rest of the working-age population, generally pooling together second-generation immigrants and the children of native-born parents (i.e. natives). As a result, most studies are likely to underestimate the true employment penalty of first-generation immigrants in comparison with natives. Moreover, they very seldom provide evidence on the relative employment performance of first- and second-generation immigrants. Last but not least, fairly little is known about the role of moderating factors (such as gender, duration of residence, or language proficiency) and especially about whether the latter have varying effects across ethnic groups.

In this paper, we aimed to overcome these shortcomings by providing a comprehensive and up-to-date quantitative assessment of the employment performance of first- and second-generation immigrants in Belgium compared to that of the children of native-born parents (i.e. natives). Particular attention has been devoted to immigrants’ specific geographical areas of origin. We were thus able to assess whether intergenerational mobility patterns differ across ethnic groups. We also intended to contribute to the existing literature by investigating the role of a large range of moderators (including gender, education, parents’ countries of birth, duration of residence, naturalisation, main reason for migration, and proficiency in the host country language). To this end, we combined data from the 2008 and 2014 ad hoc modules of the Belgian Labour Force Survey (LFS) with longitudinal administrative data taken from the Crossroads Bank for Social Security (CBSS), covering all quarters from 2008:Q1 to 2014:Q4.

Our regression analysis clearly indicates that people’s migration background is a fundamental determinant of their likelihood of being employed. Marginal effects from probit regressions show that first-generation immigrants face a substantial employment penalty (up to − 30% points) vis-à-vis their native counterparts, but also that their descendants continue to face serious difficulties in accessing the labour market. All else equal, the employment gap is more pronounced for the first than for the second generation. However, intergenerational mobility patterns are found to be quite heterogeneous: although the children of EU immigrants fare much better than their parents, the improvement is much more limited for those originating from EU candidate countries and almost null for second-generation immigrants from the Maghreb. These finding are in line with those obtained in earlier studies for France, which show that certain categories of second-generation immigrants, particularly from the Maghreb and Turkey, fail to close the employment gap with natives (Algan et al., 2010; Athari et al., 2019; Brinbaum, 2018a; Meurs, 2014; Meurs et al., 2006). They are also consistent with the segmented assimilation theory for these ethnic groups.

To get a better understanding of second-generation immigrants’ employment outcomes, we further scrutinized the role of their parents’ countries of birth. Our findings clearly highlight that the employment gap for the second generation is only critical when both parents were born abroad. When both parents were born outside the EU, the penalty is the highest: − 21% points. In absolute value, this penalty is 2% points higher than that encountered by first-generation immigrants born outside the EU. Accordingly, it appears that the social elevator is broken for descendants of two non-EU-born immigrants. Having at least one native parent therefore seems to be particularly helpful in accessing employment. This may be due, for example, to a better social network, the acquisition of more cultural capital specific to the host country or a better knowledge of how the labour market works (Meurs & Valat, 2019).

Our results are also quite striking with regard to gender. Indeed, they show that immigrant women (of both the first and second generation) face a double penalty when originating from the EU. For those coming from outside the EU (excluding other African countries), the results indicate that the penalty is even more severe: it outweighs the sum of both penalties, namely being an immigrant and being a woman. Evidence for other EU-15 countries also suggests a larger employment gap for immigrant women (Lee et al., 2020) and a double penalty has notably been highlighted by Meurs and Pailhé (2008) in France for Maghrebin women. This situation seems to result, at least in part, from more traditional gender roles endorsed by non-EU immigrant women and hence from their lower participation rates (Athari et al., 2019). However, our estimates for male immigrants suggest that differences in gender roles are not the whole story. Indeed, while the improvement in employment probabilities across generations is significant among male EU immigrants (− 18 vs. − 5% points respectively for the first and the second generation), for those from outside the EU, the decrease in the employment penalty is much more limited (− 15 vs. − 12% points). Moreover, the intergenerational mobility pattern appears to be flat for male immigrants from EU candidate countries (at around − 13% points) and even negative for those from the Maghreb (− 15 vs. − 17% points). These results suggest that demand-side explanations (e.g. discrimination) should not be underestimated.

Our results are less clear-cut on the moderating role of education. For the children of EU immigrants, the employment penalty is fairly limited and almost alike for the lower- and higher-educated (up to − 6% points). We thus find that education improves their access to employment in a similar way than for natives. For the children of non-EU-born immigrants, things are quite different: the immigrant-native employment gap among the low-educated is almost twice as big as that among the higher-educated (− 16 vs. − 9% points). Education thus appears to be an important tool for fostering their labour market integration. Yet, education is not the whole story, given that substantial employment penalties are still encountered by tertiary-educated descendants of non-EU-born immigrants. Our results further show that first-generation immigrants are quite vulnerable overall and that, in general, education less effectively improves their labour market integration. The problem of degree recognition is certainly part of the problem. However, other factors are also likely to be at play, for instance proficiency in the host country language. Our results indeed suggest that this factor is a key driver of access to employment, especially for immigrants born outside the EU. The latter’s employment penalty is divided by almost 2 (from − 33 to − 17% points) when they have at least intermediate skills, and by 3 when the host country language matches their mother tongue.

Another important issue addressed is whether the employment penalty encountered by first-generation immigrants is temporary or persistent. As expected, our results show that access to employment is significantly improved as the duration of residence increases. However, the pace of this improvement is relatively slow on average. Foreign-born people who have been living in Belgium for 10 to 20 years still face a penalty of more than − 19% points (regardless of whether they were born inside or outside the EU). As regards people born in EU candidate countries and in the Maghreb, the situation is even worse: their penalty still stands at between − 16 and − 20% points after 35 years of Belgian residency. According to Lee et al. (2020), assimilation patterns are quite heterogeneous in the EU-15 countries. While a significant employment penalty is still observed among immigrants after ten years of residence in Denmark, Germany, France and Italy, for example, the convergence of employment probabilities of immigrants and natives is much faster in other countries (e.g. Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom). Our estimates suggest that Belgium rather belongs to the former group of countries, especially when we consider assimilation patterns of non-EU immigrants.

We also tested whether citizenship take-up is associated with better employment outcomes for first-generation immigrants. Our study’s time span is interesting as it corresponds to a period during which Belgian nationality acquisition was quite easy. Unlike most previous studies (Fougère & Safi, 2009; Gathmann & Keller, 2018), we were thus able to examine this issue in a quite liberal context. Our estimates support the existence of a significant citizenship premium. Among EU-born immigrants, this premium stands at 8% points and is found to be quite stable with additional years of residence. Among immigrants born outside the EU, it is estimated at 5% points for those who have been living in Belgium for at most 15 years and up to 14% points for those with a longer duration of residence. In contrast to Corluy et al. (2011), we thus find that citizenship acquisition is associated with better employment outcomes for both EU- and non-EU-born immigrants.Footnote 46 Overall, our estimates seem consistent with the OECD (2020) statement that: “Naturalisation can be an important step towards integration. It encourages investment in host-country specific skills on the part of the immigrant, and reduces the uncertainty facing potential employers when making hiring or training decisions.”

Finally, we investigated whether and how immigrants’ employment prospects are related to the main reasons that brought them to Belgium. While free movement from EU countries accounts for about half of immigration flows to Belgium, non-EU-born immigrants have a variety of reasons for coming: family is first (47%), followed by international protection (24%), studies (11%) and economic activities (9%). These figures make Belgium a special case since, among European countries, family reunification and economic reasons respectively account on average for only 28% and more than a quarter of first permits issued between 2008 and 2016 (High Council for Employment, 2018).

Among non-EU-born immigrants who have been living in Belgium for at most 5 years, our results show that the employment penalty is the highest for refugees (-35% points), somewhat smaller in the case of family reunification (− 32% points), and the smallest for economic migrants (− 23% points). This penalty decreases for all categories of immigrants as their duration of residence increases, but at different paces. After 10 years in Belgium, the ranking is thus substantially modified: the penalty becomes equivalent for refugees and for economic migrants (around − 14% points) and is somewhat higher for family-reunification migrants (− 17% points). This outcome validates the thesis, notably put forward by Bevelander (2016), that refugees would start at a lower employment level upon arrival in the host country but subsequently ‘catch up’. Previous research indicates that refugees ‘catch up’ to the employment level of family-reunification migrants (Bevelander & Pendakur, 2014; Connor, 2010; Cortes, 2004; Lens et al., 2018). Our estimates suggest, though, that the employment performance of refugees converges towards that of economic migrants. This discrepancy might be related to the fact that economic migrants in our data are self-declared and include both those that found a job in Belgium prior to migration and those that did not. Be that as it may, our findings indicate that around a decade is needed for the employment gap between refugees and other foreign-born workers to be (largely) suppressed.

These findings call for concrete and targeted policy measures to improve the integration of people with a foreign background into the Belgian labour market. Education has been found to be an important tool to foster the employment prospects of second-generation immigrants, and especially of descendants of non-EU-born immigrants. Efforts to improve the academic trajectories and outcomes of these people should therefore be continued and intensified. Our estimates also show that the effectiveness of educational credentials is much more limited for first-generation immigrants. This suggests that initiatives enabling a swift recognition of immigrants’ diplomas and skills should be further promoted. Simplified administrative procedures for obtaining residence and work permits are probably also needed. The transposition of the EU’s Single Permit Directive (2011/98/EU) into Belgian law should contribute to achieving this goal.Footnote 47

Next, given that gender differences are found to be particularly pronounced (especially among non-EU born immigrants), as suggested by Corluy et al. (2015), one might consider initiatives to increase the use of formal childcare services by immigrant mothers in order to foster their employment chances.Footnote 48 In turn, extra investments are probably required to continue improving the availability, accessibility, quality and affordability of those services.

Our findings also indicate that proficiency in the host country language is key, especially for non-EU born immigrants. The provision of appropriate training and support for immigrants in their job search process should thus be further encouraged. This is especially relevant given that Belgium has three national languages. The integration pathways, which have been compulsory in Flanders since 2004, in Wallonia since 2016, in the German Community since 2017 and are planned to become mandatory in Brussels, should also contribute to this end.

Finally, our results show that substantial differences in employment outcomes among people with varying migration backgrounds are still observed after controlling for a large range of moderators. These unexplained differences might result from various factors, such as social capital, preferences and discrimination. Various initiatives have been recently taken by the Belgian authorities to strengthen the fight against discrimination based on place of birth. For instance, the law of January 2018, inserted in the Belgian Criminal Code, enables social inspectors to rely on anonymous test methods, including “mystery calls” and fake CVs, to establish whether employers are in breach of anti-discriminatory policy. At the same time, there have been some initiatives to help employers address the challenges of workforce diversity. Brussels’ Public Employment Service (Actiris), for instance, offers free assistance for recruitment and human resource management to companies willing to increase the diversity of their workforce in the capital region. While all these initiatives certainly indicate that combating discrimination against ethnic minorities is a priority in Belgium and that concrete steps are being taken, the effectiveness of these measures (and the potential need to develop new ones) remains to be investigated in future research.

Notes

Regarding neighbouring countries, while the employment rate among foreign-born individuals is the same in France as in Belgium, it is significantly higher in the Netherlands (67%) and in Germany (71%). Conversely, the employment gap with respect to natives is more similar between those countries (7% points in Germany, 8% points in France and Belgium, and 14% points in the Netherlands). The United Kingdom is a country combining a high employment rate and almost no gap with respect to natives.

EU-14, Other EU countries, EU candidate countries, Other European countries, The Maghreb, Other African countries, The Near and Middle East, The Far East and Oceania, Other Asian countries, North America, Central and South America.

Rather than focusing on employment, most articles in the literature have estimated the impact of naturalisation on immigrant wages. The evidence for a citizenship wage premium is mixed, with some articles suggesting a significant positive effect, while others do not (see e.g. Bratsberg and Raaum, 2011 and Helgertz et al., 2014). In a recent article, Peters et al. (2020) offer some theoretical explanations for this ambiguity and test their validity using information on almost all registered first-generation immigrants who migrated to the Netherlands between 1999 and 2002 for a period of 10 years. Their estimates reveal a modest one-off increase in the earnings of immigrants from less developed countries and unemployed immigrants after naturalization. Moreover, they show that the increase in immigrant earnings is more pronounced before than after naturalisation. These results suggest that immigrants anticipate the acquisition of citizenship by investing in their own human capital and thus improving their labour market performance before naturalisation. Overall, the authors thus conclude that naturalisation has a significant effect on immigrant wages but that this effect is not universal and that most of this effect occurs before obtaining citizenship.

Analysing the 2015 PISA results for Belgium, Danhier and Jacobs (2017) emphasise the low level of equity in terms of origin in the Belgian schooling system, one of the lowest among industrialised and democratic countries.

Interestingly, De Cuyper et al. (2018) also find some evidence suggesting that workplace and job-searching attitudes training is associated to relatively better exit rates to employment for second-generation immigrants. This outcome is in line with an earlier study for Flanders undertaken by Vandermeerschen et al. (2017).

To identify the level of education, the Crossroads Bank for Social Security uses information supplied by the public employment services (Actiris, ADG, Forem, VDAB). This implies that the level of education is only recorded when the person in question has already experienced unemployment during the period under study (2008–2014). That only applies to 36% of the people covered in the database. To avoid this limitation, we have chosen to rely on the level of education recorded in the 2008 and 2014 LFS ad hoc modules, which is available for all surveyed individuals. It should be noted that information on the level of education in the LFS is self-declared and therefore does not necessarily correspond to that recognised by the Belgian authorities. The highest educational attainment is determined using the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED): at most lower secondary education corresponds to ISCED levels 0 to 2, higher secondary education corresponds to ISCED level 3 to 5 and tertiary education to ISCED level 5 or above.

3740 individuals for whom the country of birth of at least one of their parents was missing have been dropped. This reduced our initial sample by 7.6%.

For a detailed description of country categories see “Appendix 1” in Piton and Rycx (2020).

This choice stems from the fact that: (1) children born in Belgium before 1st June 2014 were named after their father (since then, the legislation has become more flexible) and (2) correspondence studies have shown that callback rates depend upon the origin of job seekers’ names (Baert & Vujic, 2016; Baert et al., 2017; Biaraschi et al., 2017; Zschirnt and Ruedin, 2016).

While this is true in most EU countries (with the exception of e.g. Portugal, Ireland and the United Kingdom), the difference is particularly significant in Belgium. According to EU LFS statistics, the proportion of low-educated immigrants is almost 17% points higher than the proportion of low-educated natives in Belgium, which is the fifth largest gap among EU countries (behind Germany, Sweden, France and Finland).

Descriptive statistics for the whole population are obtained from the CBSS.

In the CBSS, educational attainments are only available for a small fraction of the population (see footnote 8). Hence, descriptive statistics from the CBSS relative to the level of education should be considered with caution.

Average marginal effects have been computed. Moreover, cluster-robust standard errors are presented between parentheses. For this purpose, we rely on the option ‘vce(cluster clustvar)’ in Stata 16, which specifies that the standard errors allow for intragroup correlation, relaxing the usual requirement that the observations be independent. That is to say, the observations are independent across groups (clusters) but not necessarily within groups. Clustering is performed at the individual (i.e. worker) level.

Estimates reported in italics in Table 3 are based on data for less than 35 individuals (i.e. 35 individuals * 4 quarters * 7 years = 980 individual-quarter-year observations). Due to micronumerosity, these estimates are likely to be misleading and should thus not be interpreted. The same comment applies to all other tables in this manuscript.

Note that our results might underestimate the employment gap between first-generation immigrants born in the EU-27 and those born outside the EU since people working for international organisations (e.g. NATO or the European Union) are recorded as inactive in the data from the BCSS (they do not pay taxes and are thus not registered as workers in administrative data). For the same reason, the penalty associated with first-generation immigrants born in North America is likely to be overestimated in column (2).

These results have been compared with those reported by the High Council for Employment (2018), which estimated ceteris paribus the employment penalty of people born outside the EU compared with those born in Belgium (independently of whether the parents of those people were born in Belgium or abroad). As expected, this comparison shows that pooling natives and second-generation immigrants together leads to underestimation of the true employment penalty for almost all categories of first-generation immigrants born outside the EU (i.e., people born in the Maghreb, other African countries, EU candidate countries, other Asian countries, the Far East and Oceania, and South and Central America) with respect to natives. At the same time, we find that ceteris paribus the employment penalty for first-generation immigrants from the Near and Middle East, other European countries and North America with respect to natives is over-estimated when pooling natives and second-generation immigrants together.