Abstract

Children often prefer nonfiction to fiction books but historically, teachers have neglected nonfiction books during reads alouds. The present study examined how young readers collectively make meaning of nonfiction picturebooks with the help of the teacher and their peers during a whole group interactive read-aloud in one kindergarten classroom. Using Bakhtin’s dialogism and Rosenblatt’s reader response theory, this study captured videos of nonfiction read-alouds, interviews, and formal observations to examine how children make sense of nonfiction picturebooks during whole group read-alouds. This study exposes the social nature of learning. Findings indicate that readers of nonfiction consider the responses of those around them in their takeaways, that making sense of nonfiction is a continual and discursive process, and that children used nonfiction books as a way to connect with one another. Implications for conducting nonfiction read-alouds with young children are discussed. This research exposes the power and potential for interactive read-alouds using nonfiction picturebooks with kindergarteners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

We are currently in the “golden age of nonfiction” children’s literature (Schnazer, 2023), but researchers, teachers, and writers are still calling for nonfiction to be included in early childhood and elementary classroom curricula (Hadjioannou et al., 2023). In 2023, NCTE released a statement describing how teachers could use nonfiction in curricula related to reading, writing, visual literacy, research processes, and diversity. Nonfiction picturebooks are more engaging (Graff & Shimek, 2020; Moss, 2003), synergistic (Shimek, 2019), and aesthetically appealing (Gill, 2009; Hadjioannou et al., 2023) than ever before. Children often prefer nonfiction to fiction books but historically, teachers have neglected nonfiction books during reads alouds due their length and expository structure (Conradi Smith et al., 2022; Duke, 2000). And despite these calls for nonfiction to be included in the early childhood classroom, few researchers have examined how expert teachers conduct read alouds using nonfiction picturebooks with young children (Yenika-Agbaw et al., 2018).

Additionally, few studies examine how young children respond to nonfiction picturebooks (Shimek, 2021). For example, Sipe’s (1998) groundbreaking work on the synergy of picturebooks excluded nonfiction picturebooks. Most studies examining how young children respond as readers to nonfiction picturebooks have either neglected nonfiction completely, or have not focused on this as their central goal (Adomat, 2009; Greeter, 2016). I embarked upon this research with the goal of better understanding how teachers and students used nonfiction picturebooks in an early childhood classroom. I wondered how readers make sense of nonfiction books read collectively, during whole group interactive read-alouds, but also how their individual experiences shape their understandings of nonfiction books. Wiseman (2011) described interactive read alouds as experiences that go “beyond skills and literacy development” to become opportunities for readers to “develop, design, and acknowledge certain forms of knowledge” (p. 432). Ultimately, the purpose of this study was to explore how interactive read-alouds using nonfiction books could be a collective and dialogic process that children continue to engage in as they move throughout the world.

In recognition of the complexities and multiple layers of understanding stories, as well as the lack of research examining readers’ responses to nonfiction children’s literature, I examined how young readers collectively make meaning of nonfiction picturebooks with the help of the teacher and their peers during a whole group interactive read-alouds in one kindergarten classroom. This case study of one elementary school classroom in the Southeastern United States was undergirded by Bakhtin’s (1929/1984) concept of dialogism and Rosenblatt’s (1938/1995) transactional theory of reading. I examined how 20 kindergartners individually and collectively responded to the power of nonfiction picturebooks by conducting an interaction analysis of videos of the classes’ nonfiction interactive read-alouds. I highlighted how children engaged with nonfiction picturebooks by analyzing video recordings that captured how students communicated with one another and made sense of nonfiction picturebooks as a group of readers. Furthermore, I conducted interviews with the teacher and student participants, took field notes, collected relevant documents, and photographed moments related to nonfiction interactive read-alouds throughout the classroom over the course of six months. I engaged in all of these activities to answer the following research question: How do students transact with nonfiction picturebooks during whole group interactive read-alouds to collectively construct meaning?

Relevant Literature: Nonfiction in Early Childhood Classrooms

When it comes to approaching nonfiction in the classroom, teachers continue to rely on the discourse that “nonfiction contains factual information about the world” (Kersten, 2016, p. ii). The prevailing concerns for teaching nonfiction to young readers, then, is how to help students navigate the various text structures of nonfiction and how students comprehend nonfiction (DeVries, 2023). This focus on students being able to point to evidence has caused scholars to emphasize the close reading of texts. “Close reading is a process that helps understand both the surface and the deeper levels of complex text” (Dollins, 2016, p. 49). Close reading is labeled as a necessary skill for readers of nonfiction in order for them to recognize the various information that is important or not (DeVries, 2023) and is classified as an intense, attentive reading and rereading to obtain new information (Cummins, 2013; Fisher & Frey, 2015).

Duke (2000) argued that children’s difficulties with nonfiction books stemmed from a lack of instruction in school and that providing students with an overview of various text structures frequently used in nonfiction books would help students navigate these texts. This discourse has continued to pervade scholarly literature related to nonfiction, as numerous scholars continue to write about the various structures and changes with text structures that occur in nonfiction children’s books (Detillion, 2021; Maloch & Bomer, 2013). Belfatti (2015) demonstrated that informational/nonfiction includes more visual and textual features than fiction, which supports the instructional discourse of text structures and features. Detillion (2021) provided readers with an overview of text structures in nonfiction science books with the intention of supporting their comprehension. Chlapana (2016) designed an intervention for 15 kindergartners to determine if they could help young children navigate different text structures and found that children could accomplish this reportedly challenging task in only two months. While the prevailing discourse seems to be that understanding text structures is essential for readers of nonfiction and must be taught, Chlapana’s research shows how young children can learn how to navigate these structures in a relatively brief amount of time when provided sufficient instruction.

Additionally, comprehension in relation to strategies to navigate text structures and features continues to be heavily emphasized in teaching nonfiction in elementary schools. Fisher and Frey (2015) described how readers need to employ a variety of strategies as they read nonfiction, but readers also need to recognize when these strategies are working and when they are not to aid with comprehension. Rereading is often recommended for students to practice and engage with in order to aid in their comprehension (Detillion, 2021). Strong and colleagues (2018) suggested finding one area of study for readers to focus on, as this supports developing background knowledge, which then supports readers’ long-term comprehension. They also suggest that teachers present readers with simple texts first on a specific topic and increasingly allow the texts to become more complex. Regardless of the strategy, the scholarly emphasis on helping readers comprehend nonfiction suggests that readers’ goals or stances should be efferent in their approaches to nonfiction (Barone & Barone, 2016; Galda & Liang, 2003). Emphasizing what students take away is important, but it also ignores other essential components of the reading transaction that Rosenblatt (1938/1995) theorized about. While the discourse of teaching nonfiction in schools remains focused on assisting students with close readings, text structures, and comprehension strategies, this dissertation focuses on children’s aesthetic and efferent responses to nonfiction, not just the latter.

Nonfiction Read-Alouds

Although efforts in expanding approaches to reading nonfiction (Graff & Shimek, 2020; Dawes et al., 2019) are currently being published, studies that focus on nonfiction read-alouds also continue to emphasize efferent approaches to nonfiction and include strategies such as rereading, asking comprehension questions, and Know/Wonder/Learned charts (Yenika-Agbaw et al., 2018). Studies have shown that teachers do not read-aloud nonfiction often to children and parents read nonfiction aloud to their children about as often as teachers, which is approximately 7% of the time (Singh, 2023; Yopp & Yopp, 2000). And yet, there are a variety of scholars who have conducted research highlighting the benefits of regular nonfiction read-alouds.

Pentimonti and colleagues (2010), for example, found that nonfiction read-alouds in early childhood classrooms benefitted students’ vocabulary and the development of abstract concepts, gave students knowledge of text structures, and promoted students interests in new topics. Oliveira and Barnes (2019) emphasized how nonfiction assisted students’ construction of knowledge, allowed students to develop understandings of the real world, and provided elaboration on topics of interest for students. McClure and Fullerton (2017) examined one teacher’s use of informational read-alouds in her third-grade classroom and argued, “Teachers are able to demonstrate strategies and provide students with multiple opportunities to practice the strategies when the text is read aloud” (p. 58). Finally, research in nonfiction read-alouds emphasizes that like reading aloud fiction texts, teachers should use expression, allow students to converse about what they are hearing, find interesting books, build anticipation by only reading short segments, infuse talk throughout, and emphasize questions (Stead, 2014).

Reader Responses to Nonfiction

There are a few studies that examine reader responses to nonfiction or informational texts, but none of them examine the responses of young children or kindergarteners, specifically. Moss and Hendershot (2002) used nonfiction books with middle school students and found that the use of trade books encouraged the participation of reluctant readers. After Wilfong (2009) noted middle school students’ positive approaches to nonfiction in literature circles, Barone and Barone (2016) adapted literature circle roles to focus on informational texts with 61 fifth graders. They found that students enjoyed reading nonfiction texts and that, collectively, students worked together to make sense of the texts, they returned back to the books without prompting for further clarification, and they incorporated the vocabulary of the books into their discussions.

Khieu (2014) collected the responses of fourth graders participating in small group discussions with nonfiction literature and reported, “students responded to nonfiction in many, varied, and often unique and individual ways” (p. ii). Greeter (2016) noticed that early childhood students responded to all classroom read-alouds in multimodal ways, regardless of the genre of book. Shimek (2023) found that students often responded to nonfiction read alouds during the nonacademic parts of the day, that is the transitions between subjects, during recess, and non-instructional times. Even though these studies were instrumental in my desire to better understand how readers respond to nonfiction texts, they examined reader’s responses of nonfiction books during small groups, rather than whole group read-alouds, and they were focused on upper elementary or middle school students; whereas my goal was to observe young children’s meaning making of nonfiction. This research was designed in response to this literature and provides new thinking about nonfiction books in early childhood classrooms. It is meant to emphasize the complex meaning making that occurs beyond close readings or comprehension, including dialogic transactions with classmates and, potentially, the world. Lastly, it highlights student engagement with texts that have traditionally been overlooked in early childhood classrooms.

Theoretical Frameworks

Bakhtin (1929/1984) and Rosenblatt (1938/1995) both theorized that individuals communicate, read, and make meaning about their worlds differently, depending on their role and purpose in a given time and situation. In the present study, Bakhtin’s understanding of dialogism provided the foundation of communication and meaning-making between and among individuals, while Rosenblatt’s transaction theory of reading revealed how meaning-making occurred with nonfiction picturebooks.

Dialogism

Bakhtin (1929/1984) described dialogism as the diverging opinions of numerous voices. In a classroom, dialogism occurs when various ideas, opinions, and beliefs are shared between members of the class. As other members of the class share their thinking the listening members are also revising their understandings, interpretations, beliefs, and experiences. Bakhtin argued that dialogism results in a more complex understanding of a problem rather than a solution; his ultimate goal was to understand the variety of voices and perspectives that exist, not to find one clear answer. A dialogic teacher seeks to provide a similar experience for the class; their goal is not to provide one answer or solution to a problem but rather to emphasize the variety of opinions, understandings, and ideas within the classroom.

Rosenblatt’s Transactional Theory of Reading

Rosenblatt (1938/1995) argued against the belief that there was one “true” understanding of a text. She theorized that reading literature requires a transaction between the individual reader and the text; reading does not occur when a human looks at a page, but rather when they use their own life experiences and knowledge to make sense of the words the author wrote when they are in dialogue with the text. Even though Rosenblatt only briefly discussed what the transactional theory might look like with a group of readers, her theories have been applied to group settings by others (Adomat, 2009; Eeds & Wells, 1989; Greeter, 2016; Many & Wiseman, 1992; Sipe, 1998, 2008; Wiseman, 2011). These studies have shown that the teacher and what the teacher chooses to focus on during the read-aloud directly affects the responses that children have to the text (Many & Wiseman, 1992; Wiseman, 2011). Despite this work, Sipe (2008) argued that many existing studies of reader response were not conducted with young children, and none examined what a transactional theory of theory looks like in practice with nonfiction picturebooks.

Methods

The data presented in this article stems from a dissertation study I conducted from January – May, 2019 that examined how young readers collectively make meaning of nonfiction picturebooks individually and collectively in one kindergarten classroom. I embedded myself in this classroom two to three days a week to document and analyze the ways children respond to nonfiction picturebooks. While moving throughout the school day with the class, I also observed how children’s understandings of nonfiction picturebooks occurred not only during the immediate read-aloud event but also throughout the non-academic moments of the school day. This case study (Dyson & Genishi, 2005) used a combination of methods including collecting video of whole group read-alouds and children reading independently, semi-structured individual interviews of the teacher and students, and written observations to understand how nonfiction picturebooks were used throughout the school day. Data sources included videos of read-alouds focused on both the teacher and the students, photographs of documents that connected with nonfiction books, audio recordings of interviews, and research field notes.

Classroom Context

The school site for this research, School for Questioning (pseudonym), was a publicly funded K-5th grade magnet school located in the Southeast United States. The population of the school reflected the district at large, which was 42% White, 48% African American, 5% Hispanic, 4% Asian, and 1% other. 48% of the students in the district qualified for free and reduced lunch. The magnet school runs on a lottery system: anyone in the district can attend if they are selected, but preference is given to the siblings of children who previously attended the school.

Ms. Burnette’s (all names pseudonyms) kindergarten classroom had 21 students and a paraprofessional, Ms. Jones, per the laws of the state the school is located in. Before receiving approval from my institutions IRB and the school district’s IRB board, I met with the principal to see which classroom might be a good fit for this study. I chose Ms. Burnette’s class because she regularly conducted interactive read-alouds with nonfiction picturebooks, she received an award from a state education association, and she had a lot of support from families which would be useful for my consent process.

Data Collection and Sources

Data was collected in three phases. In phase one, I collected consent from parents and ascent from 20 students in the class, I conducted initial interviews and observations on how nonfiction was used in the classroom. In phase two, I video recorded all nonfiction read-alouds I witnessed and captured events related to the nonfiction books children heard throughout the school day using a combination of written observations, photographs, and video. In total, I recorded 23 read-alouds of nonfiction picturebooks. In phase three, I conducted final interviews and wrapped up any loose ends.

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using Sigrid Norris’ (2019) Systematically Working with Multimodal Data: Research Methods in Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Norris designed her (Inter)action Analysis to be the first “inter-disciplinary approach that has been developed specifically for the analysis of multimodal action and interaction” (p. 2). Considering my theoretical groundings, it was important that I found a method of analysis that examined how the kindergarteners communicated with one another and Ms. Burnette to create a unique learning and reading event. Norris argued that because all actions are social, they are also inherently embedded in cultural and historical contexts, and thus shouldn’t be dislocated from these events. Because actions always take place in response to and considering a particular place and time, they are inherently always mediated, meaning they exist in response to and because of what occurred before them. This aligned well with Bakhtin’s (1929/1984) notions of dialogism.

Norris (2019) divided all actions into lower-level mediated actions, which is a “mode’s smallest pragmatic unit” (p. 40). For example, a lower-level mediated action in my study could be a student raising their hand, letting out a gasp, or touching their nose. These lower-level mediated actions add up to become higher-level mediated actions, which are chains of multiple lower-level mediated actions that work together to send communication. For example, while a lower-level mediated action might be Destiny touching her nose, a higher-level mediated action would be when she uses her fingers to grasp at her nose and pull her hand away from her body three times as she says, “Better than beaks!” (Video, April). Thus, lower and higher mediated actions always exist simultaneously. I recorded the higher-level mediated actions of the teacher and students in all 23 videos of nonfiction read-alouds. Then, I was able to identify portions of the read-alouds where the children’s engagement with the nonfiction picturebooks were heightened. This included lots of movement connected to the read-aloud, separate conversations between students, or conversations among the class where more questions were raised than answered. Although I documented the higher-level mediated actions for all 23 nonfiction books, I selected eight dialogic read-aloud clips to analyze further based on the complexity of the discussion and the engagement of the children during these clips. A list of the books that sparked these dialogic learning moments can be found in Appendix A. As this study was not designed to be an intervention, these books were not provided by me, the researcher, but were books Ms. Burnette had already planned to read aloud with the students and resulted in dialogic learning experiences.

Once the eight dialogic read-alouds had been identified, I transcribed each of the video events, including language, lower-level mediated actions, and higher-level mediated actions spoken of the teacher and children, thus creating my transcripts of the interactions that occurred during the read-alouds. Finally, I coded each video transcript inductively and deductively. I selected the most frequently documented higher-level mediated actions of the teacher and kindergarteners from my initial coding as a priori codes. I also coded these transcripts in vivo, as the microanalyses allowed me to gain new insights about what occurred during the read-alouds. Coding both from a bottom-up and a top-down approach allowed me to look across the eight dialogic read-alouds and get a sense of what occurred most consistently across the events, rather than focusing on each individual read-aloud. I collapsed the a priori higher mediated actions and in vivo codes I created into larger themes, which I present in the subsequent section.

Findings

In the following sections, I highlight numerous ways children were engaging with nonfiction picturebooks during whole group read-alouds. This findings of this research found that during nonfiction read-alouds with picturebooks, students relied upon one another to make sense of the texts. They also used the books to connect with one another socially and influenced each other’s responses to texts.

Using each Other to Make Sense

Scholars have described the ways readers’ responses build upon one another during whole group interactive read-alouds (Many & Wiseman, 1992; Sipe, 2008). This was true, too, during the nonfiction read-alouds in Ms. Burnette’s class, but using video data captured both the verbal and nonverbal responses of students. For example, when reading the dedication page in March for Mama Built a Little Nest (Ward & Jenkins, 2014), the illustrator Steve Jenkins dedicated his work “For Robin” (n. p.). This provided a point of confusion for some of the students, who wondered if he was dedicating his artwork to a person or a bird.

Ms. Burnette: Mama built a little nest. For my parents Paul and Charlene, who created the best nest ever. And then, Steve Jenkins dedicated it for Robin. Ready?

Jason: Who’s Robin?

Gavin: It’s a bird!

Weston: My neighbor’s name is Robin.

Ms. Burnette: This was written in 2014. Wow!

Jason: You can’t dedicate it to a bird.

Ms. Burnette: Look at this!

Gavin: Well, sometimes. Like, Weston just said his neighbor’s name was Robin (Video, March).

Although Ms. Burnette continued with the read-aloud and did not directly answer Jason’s question, Weston and Gavin jumped in to explain what or to who Steve Jenkins might have been dedicating this book. Together, the children responded to one another’s thinking and used their personal experiences to shape their personal understandings and the meaning of the children around them.

In another example, in late February the class was reading from Jerry Pallotta and Edgar Stewart’s (1989) The Bird Alphabet Book, which presented a different bird, illustration, and fact on each page. Ms. Burnette asked the students why the illustrator, Edgar Stewart, drew six different hummingbirds on the page instead of just one. She asked,

Ms. Burnette: Anna, why do you think this picture looks like this?

Anna: Because there, they are like waiting, because, to get some, because the other person is getting it.

Ms. Burnette: Oh, so you’re saying this is them all waiting in line to get that nectar? What do you think, Callie?

Callie: Um, I think they are fighting in line, pushing each other to get away.

Ms. Burnette: You think they are fussing about who can get in there first? What do you think, Peyton?

Peyton: Um, that they’re trying to get their food and the other one is taking too long.

Ms. Burnette: Do you think so? Um, what do you think, Maddox?

Maddox: Um, he’s going too- he’s going fast to get pollen (Video, February).

Anna’s thinking included the fact from the book, which was that hummingbirds flew fast to drink nectar, but missed the piece about the hummingbird flying rapidly to eat. Callie’s response included Anna’s theory that they were in a line, but she hypothesized they were fighting, perhaps based on her experiences waiting in line as a kindergartener. Peyton, too, built upon the fact of the book, Anna’s idea, and Callie’s thinking but took the idea one step further. It wasn’t until Maddox, who had been interjecting through the entire page about how fast hummingbirds were, was able to speak and made the connection to the image being a blur that Ms. Burnette decided to stop getting ideas from students and show them how Edgar Stewart used multiple birds to make the image “like a cartoon.”

Later in the read-aloud, when Ms. Burnette called upon Joseph, he admitted, “Uh, uh, I think they are having a contest of who can get there faster.” Ms. Burnette replied, “You think there’s more than one? But remember what I told you about nonfiction books sometimes, why illustrators draw more than one to show you how they move.” Despite Ms. Burnette’s teaching, Maddox’s comment about how they move rapidly, and numerous children trying out how to see something as a “blur” with their bodies, Joseph still held onto the ideas of those first few commentators. Ms. Burnette tried to correct his thinking, but his determinations about the book had already been established. Still, although Joseph did not ultimately take away the “real” reason why the illustrator drew the picture, he did transact with the text and used the knowledge of those around him to form his opinion. This exchange, among others, shows how students’ transactions are always developing in situ and, in the case of whole group read-alouds, are built upon the ideas of those around them, regardless of the content or the genre of the book.

Connecting with One Another Socially

Students also used topics from nonfiction read-alouds to initiate conversations with one another. After Jason spent much of the morning reading a book about the orchestra and violins, Stephanie approached him and said, “You know Jason, you should come to my house. My dad plays the trumpet and he keeps it in his office!” Jason smiled and replied, “He does? Was he in an orchestra?” Stephanie excitedly added, “He used to be! You can come to my house and I can show it to you!” Jason said, “Ok! Let’s ask my mom after school.” Stephanie put both hands up in the air and shouted, “Alright!” Stephanie used Jason’s interest in a particular book to connect with him socially and further develop their friendship.

Students were very aware of each other’s interests and would often bring books to each other that they suspected they would like. This also happened when students found the names of someone in the class in a book. Clarence was reading independently in late April when he came across Connor’s name. He ran over to Connor and said, “Connor! I found your name!” He pointed at Connor, then at his nonfiction book, then back and Connor. Connor got a huge grin on his face and said, “Really?” Clarence pointed to the name in the book, and Connor followed his finger across the letters of his name. Connor then looked at the book’s cover and said, “Cool!” before Clarence returned to read alone (Video, April).

In March, again while reading Mama Built a Little Nest (Ward & Jenkins, 2014), Zuri was observed leaning in and whispering to Kennedy and pointing at the image in the book. Kennedy looked up at the book’s page and opened her mouth, presumably in surprise. After her mouth dropped open, she exclaimed, “Awww.” Although neither girl spoke out verbally loud enough for anyone else to hear them until Kennedy said “aw,” it was evident that they were discussing the book’s content and transacting together about the page. Zuri knew Kennedy would be interested in the book’s topic and used this opportunity to connect with Kennedy. In reviewing the video recordings, it was common to witness students, particularly girls, whispering quietly to one another about what they were thinking about. Although some classrooms might have discouraged this behavior, it is evident in the videos that the children are discussing concepts from the read-aloud, and thus transacting with the text and developing understandings. These “misbehaviors,” in these instances, become subtle moments of reading as transactions when you notice what children are doing and re-frame children’s actions.

Copying Each Other During Read-Alouds

Citationality is the term Bakhtin used to describe how members of a social group will mirror or cite one another (Bakhtin, 1929/1984). Citationality is often used in social situations to show congruence or communicate alignment with those around us. One of the best examples of citationality occurred during the shared reading of the big book, A Beaver’s Tale (Williams & Howe, 2007), in April. This book is a nonfiction book about beavers, but it is written as a poem, so it rhymes and has multiple lines that repeat. This made the book engaging for early readers because it was easy to remember and used a lot of repetition. During the read-aloud, multiple children on the carpet acted out the words of the book. Some children did this more subtly than others. Jason, for example, simply slapped his thigh to the song’s rhythm as he read aloud with the class. Others, like Destiny, began acting out the book with the movement of their entire body. Once Destiny acted out the push and pull motion of the lyrics a few times, students around her followed Destiny’s lead and began acting out the parts of the book using their full bodies, too. Quickly, Kennedy, Joseph, Sally, Gavin, and even Callie begin to replicate similar movements as Destiny, drawing parts of their bodies back and pushing them forward rapidly. They continued these actions throughout the read-aloud. It was evident during this reading event that the children used the gestures of those around them to shape their understandings and began to enact the book in similar ways.

Lastly, while reading Animal Acrobats (Drew, 1992), a conversation began about leopard frogs and how tiny their front legs are compared to their back legs. One child said, “My arms are shorter than my legs!” and stretched out their arms to show Ms. Burnette. Ms. Burnette agreed but said, “Yes, but they are not three times longer than your arms.” Within seconds, Lucas, Ariana, Maddox, Sally, and Weston stretched their arms and legs out on the carpet to see how long their legs were compared to theirs. They copied the body movements of their peer to conduct a measurement of their own and found that they were all pretty similar. Still, this showed how the comments, gestures, and transactions of one student greatly affected the comments, gestures, and ultimately, transactions of others and magnified how children learn from those around them. When this Kindergarten class read nonfiction books together, it was clear they were making sense not only of the text but how to respond to books and to those around them in meaningful or appropriate ways. This appropriateness was determined by the reactions of those around them, not just from the teachers but also from their peers. If a child copied the movements and gestures of the student sitting next to them, that other child could shut them down with a mean facial expression and a “stop that!” or they could smile excitedly and continue to respond physically with the child. These decisions, connections with one another, and copying of movement were an additional layer of response and negotiation the children navigated throughout the read-alouds.

Discussion

In examining how a group of young children collectively responded and made sense of the whole group interactive read-alouds in their kindergarten class, it became abundantly clear that “reading is social” (Mrs. Burnette, Personal Interview, May). Not only did children use nonfiction picturebooks to connect with one another, they also used one another to inform their own responses and copied each other’s reactions throughout the read-alouds. The students’ responses built off one another. The findings from this research highlight how a reader’s response in a whole group setting isn’t just the child interpreting what happens in a book, or interpreting what their teacher says, but rather relies upon the students around them making sense of the text, too. Through these dialogic interactions between classroom members, children did not always take away the information Ms. Burnette intended, but a more nuanced and complex understanding, filled with many voices, movements, and perspectives, was achieved. Ultimately, the kindergarteners’ takeaways were based not just on the nonfiction book and or the teacher but on the collective experience of those around them during the interactive read-aloud.

These findings also emphasize the dialogic nature of learning from all members of the classroom, but especially from the children learning from one another facilitated and modeled during the teacher’s read-alouds. Throughout this study, children consistently chose to read with one another, they talked to one another throughout the whole group read alouds, and they played together in ways that continued their understandings of the nonfiction picturebooks they were exposed to. The examples I documented emphasized the dialogic relationships that exist in classrooms, sometimes aided by the design and structure of the teacher, but often instigated by the children themselves. Students, even those who said they preferred to read alone, were far more likely to read with a friend when given the option, and video analyses of these collective readings show how children were negotiating different meanings between each other and the nonfiction books, providing a polyphony of voices and discourses. Through these negotiations, children took away new information, changed their perspectives at times, and better understood the complexities and variety of information available in the world.

From an engagement perspective, Ms. Burnette recognized the benefits of children being able to express themselves, and of the positive contributions of the children as they made connections. At times, it was challenging to hear the voices of each student in the class. Young children can only remain “on-task” for so long and teachers have expectations of being “in control” of the classroom and children’s behaviors. Yet, these outward expressions of meaning-making from the children greatly contributed to the classes’ overall understandings, shaped the direction of the classroom discussion, and ultimately, shaped much of the teaching Ms. Burnette did. Leading a dialogic classroom requires many voices to be heard. The findings from this research show that best practices for engaging in picturebooks with young children requires a lot of varied viewpoints and discourses. This is true in fiction, certainly, but is especially true when reading nonfiction picturebooks, too. These interactive read-alouds suggest that children inherently learn and communicate through interactions with one another; the more conversation and social interactions, sanctioned or not by the teacher, the better.

Teaching Implications for Early Childhood Teachers

-

Nonfiction picturebooks are more engaging than ever before (Graff & Shimek, 2020). Use them regularly through your curriculum and in a variety of ways (Hadjioannou et al., 2023).

-

Dialogic classrooms require interactive read alouds (Wiseman, 2011) with all genres, but especially nonfiction (Conradi Smith et al., 2022).

-

Students’ transactions are built upon the ideas of those around them, regardless of the content of the book (Sipe, 2008; Khieu, 2014). As teachers, this means that we need to accept a wide variety of understandings and responses to any book, even nonfiction (Rosenblatt, 1938/1995; Shimek, 2021).

-

Student’s “misbehaviors,” in many cases, may actually be their response to the read-aloud (Shimek, 2023). Notice what students are doing and allow actions that connect to the curriculum. The more we allow students to move in our classrooms, the more they learn (Greeter, 2016).

-

Expect children to copy the gestures of other students around them (Bakhtin, 1929/1984). Similar to their responses, children are learning from one another through movement, too. Teacher should allow, encourage, and model movement as a response to nonfiction books for students (Shimek, 2023).

Implications

When we consider the potential, power, and practices of nonfiction picturebooks with young children, it becomes clear that pedagogical practices in early childhood classrooms need to deviate from “traditional” models of read-alouds. Rather than children sitting quietly, with their hands in their laps, this study demonstrates that when we allow children to become a part of the learning experience, their takeaways become more complex and nuanced. As teachers of young children, then, our goal is to create a dialogic learning experience whereby students hear each other’s perspectives, work together to figure things out, and learn to connect with each other through books.

Many scholars that examine nonfiction or informational texts emphasize the reader’s need to examine text structures (Detillion, 2021; Fisher & Frey, 2015) and conduct close readings (Cummins, 2013; DeVries, 2023; Dollins, 2016). to fully understand a book, and usually recommend a linear process of: identify text structures, read headings, summarize main points of a paragraph, etc. But my findings suggest that understanding nonfiction books is not a linear process; instead, it is a process that requires readers to continually negotiate multiple sources of information over time and with the discourses and opinions of others. Although the information being read aloud to children was informative, the collective reading experience meant that children shared all information available to them, which included factual and fictional explanations for things (Shimek, 2021). The children’s ultimate takeaways from these interactive read alouds were highly dependent upon the classroom conversations and often resulted in children responding to and listening to one another, even if their peers’ suggestions were fantastical.

Ms. Burnette acknowledged how the children relied upon their experiences with each other, but this discourse opposes much of the research geared towards understanding how to teach nonfiction books to young readers (Cummins, 2013; DeVries, 2023; Galda & Liang, 2003), though is demonstrated by researchers of collective fiction reading (Adomat, 2009; Eeds & Wells, 1989; Sipe, 2008). Ms. Burnette recognized that the children each contributed understandings to the class and internalized the understandings of those around them. In this kindergarten class, reading any book was a social act. As we continue to explore picturebooks with young children, nonfiction or fiction, we must remember that the potential is not in the book, but in who engages with the book. Together, our understandings can be more nuanced, complex, and dialogic than they ever could be alone.

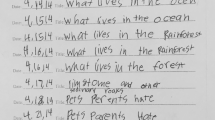

Appendix A

Nonfiction Pitcurebooks Cited and Read-Aloud by Ms. Burnette

Drew, D. (1992). Animal acrobats. Rigby Leveled Readers. HMH Books for Young Readers.

Judge, L. (2019). Born in the wild: Baby mammals and their parents. Roaringbrook Press.

Markle, S. & McWilliams, H. (2014). What if you had animal hair? Scholastic.

Mazzola, Jr. F. (1997). Counting is for the birds. Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc.

Osbourne, J. (1999). Inventions. Newbridge Educational Publishing, LLC.

Pallotta, J. & Stewart, E. (1989) The bird alphabet book. Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc.

Ward, J. & Jenkins, S. (2014). Mama built a little nest. Beach Lane Books.

Williams, R. & Howe, P. (2007) A beaver tale. McGraw-Hill Publishing.

References

Adomat, D. S. (2009). Actively engaging with stories through drama: Portraits of two young readers. The Reading Teacher, 62(8), 628–636. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.62.8.1.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). Problems of Dostoevsky’s poetics (8th ed.). (C. Emerson, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published 1929).

Barone, D., & Barone, R. (2016). Really, not possible, I can’t believe it: Exploring informational text in literature circles. The Reading Teacher, 70(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1472

Belfatti, M. A. (2015). Lessons from research on young children as readers of informational texts. Language Arts, 92(4), 270.

Chlapana, E. (2016). An intervention programme for enhancing kindergarteners’ cognitive engagement and comprehension skills through reading informational texts. Literacy, 50(3), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12085.

Conradi Smith, K., Young, C. A., & Core Yatzeck, J. (2022). What are teachers reading and why? An analysis of elementary read aloud titles and the rationales underlying teachers’ selections. Literacy Research and Instruction, 61(4), 383–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2021.2008558.

Cummins, S. (2013). Close reading of informational texts: Assessment-driven instruction in grades 3–8. Guilford Press.

Dawes, E. T., Cappiello, M. A., & Magee, L. (2019). Portraits of perseverance: Creating picturebook biographies with third graders. Language Arts, 96(3), 153–166.

Detillion, R. (2021). Using science texts to foster informational reading comprehension. The Reading Teacher, 74(6), 677–690. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1991.

DeVries, B. A. (2023). Literacy assessment and intervention for classroom teachers. Routledge.

Dollins, C. A. (2016). Crafting creative nonfiction: From close reading to close writing. The Reading Teacher, 70(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1465.

Duke, N. K. (2000). 3.6 minutes per day: The scarcity of informational texts in first grade. Reading Research Quarterly, 35(2), 202–224. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.35.2.1.

Dyson, A. H., & Genishi, C. (2005). On the case. Teachers College Press.

Eeds, M., & Wells, D. (1989). Grand conversations: An exploration of meaning construction in literature study groups. Research in the Teaching of English, 4–29.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2015). Teacher modeling using complex informational texts. The Reading Teacher, 69(1), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1372.

Galda, L., & Liang, L. A. (2003). Literature as experience or looking for facts: Stance in the classroom. Reading Research Quarterly, 38(2), 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.38.2.6.

Gill, S. R. (2009). What teachers need to know about the new nonfiction. The Reading Teacher, 63(4), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.63.4.1.

Graff, J., & Shimek, C. (2020). Revisiting reader response: Contemporary nonfiction children’s literature as remixes. Language Arts, 97(4), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.58680/la202030512.

Greeter, E. (2016). Examining meaning-making through story-based process drama in dual-language classrooms (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from: https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/41667/GREETER-DISSERTATION-2016.pdf.

Hadjioannou, X., Cappiello, M. A., Bandré, P., Burgess, M., Crawford, P., Dávila, D., & Stewart, M. (2023). Position statement on the role of nonfiction literature (K-12). National Council of Teachers of English. https://ncte.org/statement/role-of-nonfiction-literature-k-12/

Kersten, S. (2016). Nonfiction is not another name for fiction: The co-construction of nonfiction in a primary classroom (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from: https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=osu1460978333&disposition=inline

Khieu, T. L. (2014). The nature of students’ efferent or aesthetic responses to nonfiction texts in small, peer-led literature discussion groups (Doctoral Dissertation). ProQuest LLC.

Maloch, B., & Bomer, R. (2013). Informational texts and the common core standards: What are we talking about. Anyway? Language Arts, 90(3), 205.

Many, J., & Wiseman, D. L. (1992). Analyzing versus experiencing: The effects of teaching approaches on students’ responses. In J. Many, & C. Cox (Eds.), Reader stance and literary understanding: Exploring the theories, research and practice (pp. 250–276). Praeger.

McClure, E. L., & Fullerton, S. K. (2017). Instructional interactions: Supporting students’ reading development through interactive read-alouds of informational texts. The Reading Teacher, 71(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1576.

Moss, B. (2003). Exploring the literature of fact: Children’s nonfiction trade books in the elementary classroom. Guilford Publications.

Moss, B., & Hendershot, J. (2002). Exploring sixth graders’ selection of nonfiction trade books. The Reading Teacher, 56(1), 6–17.

Norris, S. (2019). Systematically working with multimodal data: Research methods in multimodal discourse analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

Oliveira, A. W., & Barnes, E. M. (2019). Elementary students’ socialization into science reading. Teaching and Teacher Education, 81, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.02.007.

Pentimonti, J. M., Zucker, T. A., Justice, L. M., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2010). Informational text use in preschool classroom read-alouds. The Reading Teacher, 63(8), 656–665. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.63.8.4.

Rosenblatt, L. (1995). Literature as exploration (5th ed.). Modern Language Association. (Original work published 1938).

Schnazer, R. (2023). A “golden age” of nonfiction Reading Rockets: Launching Young Readers. https://www.readingrockets.org/videos/golden-age-nonfiction.

Shimek, C. (2019). Sites of synergy: Strategies for readers navigating nonfiction picture books. The Reading Teacher, 72(4), 519–523. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1754.

Shimek, C. (2021). Recursive readings and reckonings: Kindergarteners’ multimodal transactions with a nonfiction picturebook. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 20(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-07-2020-0068.

Shimek, C. (2023). Movement as literacy learning in elementary classroom. In S. G., Mogge, S. Huggins, J. Knutson, E. E. Lobel, & P. Segal (Eds.). Multiple literacies for dance, physical education and sports (pp. 39–52). Springer International Publishing.

Singh, S. (2023). Engaging young children with science concepts in a community-based book distribution and animal-themed literacy intervention program. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(6), 1079–1089. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01335-0.

Sipe, L. R. (1998). How picture books work: A semiotically framed theory of text-picture relationships. Children’s Literature in Education, 29(2), 97–108.

Sipe, L. R. (2008). Storytime: Young children’s literary understanding in the classroom. Teachers College Press.

Stead, T. (2014). Nurturing the inquiring mind through the nonfiction read-aloud. The Reading Teacher, 67(7), 488–495. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1254.

Strong, J. Z., Amendum, S. J., & Conradi Smith, K. (2018). Supporting elementary students’ reading of difficult texts. The Reading Teacher, 72(2), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1702.

Wilfong, L. G. (2009). Textmasters: Bringing literature circles to textbook reading across the curriculum. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53(2), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.53.2.7.

Wiseman, A. (2011). Interactive read alouds: Teachers and students constructing knowledge and literacy together. Early Childhood Education Journal, 38(6), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-010-0426-9.

Yenika-Agbaw, V., Lowery, R. M., Hudock, L. A., & Ricks, P. H. (2018). Exploring nonfiction literacies: Innovative practices in teaching. Rowman & Littlefield.

Yopp, R. H., & Yopp, H. K. (2000). Sharing informational text with young children. The Reading Teacher, 53(5), 410–423.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shimek, C. “Reading is Social”: Dialogic Responses to Interactive Read-Alouds with Nonfiction Picturebooks. Early Childhood Educ J 52, 1615–1624 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01590-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01590-9