Abstract

Despite the importance of traditional children’s literature in children’s literacy learning, little is still known about how fairytales can be effectively used for pedagogical purposes to facilitate young children’s critical participation in early literacy instruction. The main purpose of this article is to explore the intersection of literature-based instruction, multimodality, and early critical literacy pedagogies by examining how young children negotiate, represent, and (re)create their voices through engaging in counter-storytelling. The study was conducted at a kindergarten classroom located in a metropolitan city in South Korea. Using a qualitative case study method, multimodal data were collected for 5 months through classroom observations, one-to-one interviews with the parents and the teacher, observational field notes, and children’s artifacts. Findings suggest that it is important for teachers to value young children’s voices as storytellers and create a fluid and dynamic literacy atmosphere where young children explore their voice in exciting, intriguing, and multimodal ways. It also indicates that teachers need to encourage children to think critically and creatively through developmentally, culturally, and linguistically appropriate curricular activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Children’s literature, which is one of the most long-standing genres in history (Johnson 2012) is a valuable part of early literacy education (Virtue and Vogler 2009). It provides young readers with numerous benefits, including promoting imagination and creativity (Docherty 2014), conveying social and moral messages (Panca et al. 2015), and enhancing social, emotional, and cognitive skills (Hour 2000). Yet, children’s literature is not a simply aesthetic literary work, it is intimately related to the distribution of social power in society (e.g., Brooks and McNair 2009; Johnson 2012; Nodelman and Reimer 2003). Texts and literacy are socially situated and constructed (Dozier et al. 2006), and thus, the development of critical thinking skills should be a central focus of early literacy instruction (Siegel 2006).

As a method for analyzing deeply-entrenched narratives of original stories (Solorzano and Yosso 2002), counter-storytelling can help young readers to gain access to diverse points of views through multiple interpretations and to critically examine previously unquestioned dominant ideologies. While the use of fairytales in conjunction with counter-storytelling provides rich contexts for inference instruction and practice for young learners (Kelly and Moses 2018), many early childhood teachers do not actively incorporate counter-storytelling as a literacy instruction resource in their classrooms, primarily due to their own lack of experience and knowledge of counter-storytelling strategies.

Teaching critical thinking to children is an especially important issue in South Korea due to the prevalence of teacher-centered lessons and an authority-reverent culture. According to Sung and Apple (2003), Korean students are not accustomed to expressing a critical perspective to either teachers or texts. Because classrooms in Korean cultures have traditionally been teacher-dominated, Korean students are often discouraged from speaking up in the company of elders or authorities (Kim 2012; Lee and Lee 2012). Beginning in the late 1990s, the Korean Ministry of Education made efforts to overhaul the curriculum to emphasize problem-solving and higher-order thinking skills, yet a critical literacy curriculum that promotes students' critical thinking skills is still rarely present in Korean classrooms (Dewaelsche 2015). Given this situation, there is an urgent need to implement critical literacy pedagogies that can help students to think critically, ask questions and share original ideas through student-centered teaching approaches in Korean classrooms.

The main purpose of this article is to explore the intersection of literature-based instruction, multimodality, and early critical literacy pedagogies by examining how preschool-aged Korean children negotiate, represent, and (re)create their voices through engaging in counter-storytelling about fairytales. Specifically, this study is guided by the following two research questions: (1) How does counter-storytelling help the children to explore diverse points of views with multiple interpretations? and (2) How do the children negotiate and represent their voices through text-based interactions with their teachers and peers? By sharing empirical examples of young children’s authentic dialogues and their work, it aims to provide insights on how fairytales and counter-storytelling activities can be effectively used for pedagogical purposes to facilitate young children’s critical participation in early literacy instruction. The fundamental goal of this work is to provide an expanded vision of early literacy instruction, as well as the new role of early childhood teachers in the twenty-first century.

Theoretical Foundations

This study is grounded in several different theoretical frameworks, including critical literacy and reader response theories in order to gain insights into the complexities of children’s interactions with texts, peers, and their teacher during a counter-storytelling activity. First, critical literacy was adopted to conceptualize counter-storytelling and critical thinking. According to Freire (2000), literacy is socially situated and constructed as a means and proof of power, rather than a static entity. Critical literacy helps students to challenge the status quo and enables them to act as creative, active, and critical citizens in a democratic society (Freire 2000; McLaren 2007). Early critical literacy can serve as an important instructional tool to help young readers understand that literacy is never neutral but always embraces a particular ideology in decision-making (Beck 2005; Kim 2016, 2019; Vasquez 2014). It encourages young readers to uncover the assumptions behind a text, consider multiple points of view, and explore how the text and associated discussion might spark social justice action (Lewison et al. 2015). Informed by critical literacy, this study defines critical thinking as democratic and dialogical thinking which requires individuals to freely express their own experiences and viewpoints.

Critical literacy was also adopted to delineate the notion of counter-storytelling in this study, as it serves similar purposes as a critical literacy practice. Both critical literacy and counter-storytelling promotes diverse ways of meaning-making by encouraging children to develop their own ideas, instead of simply conforming to the dominant discourse embedded in texts. The goal of counter-storytelling is also to help readers to analyze and challenge “narratives of dominance” (Love 2004) and to create inclusive environments in schools (Solorzano and Yosso 2002). As the oldest form of education, storytelling has been used as an important educational tool in many different countries (Hamilton and Weiss 2005). Counter-storytelling, which involves “telling the stories of those people whose experiences are often not told” (Solorzano and Yosso 2002, p. 26), is a powerful method for creating meaning as well as analyzing and challenging dominant ideologies in books and the stories of those in power (Kelly and Moses 2018; Kim 2019). Counter-storytelling serves several important purposes, including analyzing the “majoritarian” stories (Solorzano and Yosso 2002, p. 26), making the underrepresented culture more visible, examining multiple viewpoints, and challenging simplistic viewing the world (Delgado and Villalpando 2002). Counter-stories in early childhood classrooms offer a semiotic way to explore a range of communicative forms, such as narrative, writing, drawing, and images, (Marshall 2016). By creating counter-stories, young children can expand their ideas, ask questions about what they read, engage in authentic discussions, and develop language and literacy skills.

This study was also informed by reader response theories, particularly Fish’s (1980) and Beach’s (1993) notion of reading as a cultural and social act. According to reader response criticism, reading involves the “interdependence” of the individual and the community. Readers’ literary responses are influenced by personal, social, and contextual factors such as readers’ prior knowledge, experience and level of literacy understanding (Beach and Freedman 1992; Moller 2004; Sipe 2000). While most reader response theories do not specially focus on young children’s responses to literature, Sipe (2008) encompasses “the visual aesthetic theory” (p. 8) of young children’s literary understanding. Children utilize their experiences to understand the text (Crawford and Hade 2000). Through the “life-to-text” connection (Sipe 2008), they create/recreate their current knowledge, make personal connections, and increase their engagement through multiple perspective-taking. In this process, they gain pleasure in perceiving the ways in which the story mirrors their own lives (Mills and Jennings 2011; Sipe 2000). Reader response perspectives provide important guidance about young children’s active roles during the reading process and the importance of creating interactive spaces for facilitating children’s critical and analytical engagement with texts.

In connection to theories of "visual" responses, the notion of multimodality was also used in this study to examine children’s use of diverse semiotic resources in responding to children's literature. Jewitt (2008) argues that prior to their acquisition of conventional reading and writing, young children use different modes of semiotic resources such as gestures, drawing, and oral language to convey their feelings, thoughts, and ideas. Children’s flexibility in using different semiotic modes in their meaning-making process facilitates social, emotional, and cognitive development (Dooley and Matthews 2009; Kress 2009). Using different communicative modalities also provides children with multiple avenues for producing and consuming texts (Dyson 2008). Based on this notion, the study defines “multimodality” as different modes, means, and materials that young children use in their meaning make process during literacy activities.

Methods

The Context

This study was conducted at a private kindergarten located in a metropolitan city in Korea. Based on constructivism as a teaching philosophy, the school employed the Nuri curriculum, the Korean national curriculum for five-year-olds, which aimed to stimulate children's critical thinking and to establish overarching principles for becoming responsible citizens of the society (KICCE 2013). Because the school followed the Nuri curriculum, which emphasizes students' critical thinking and creative thinking, no tensions were observed regarding this work while conducting this study.

Participants

Of the seven classes, Ms. Choi’s class (note: all names used in this study are pseudonyms) was selected for this study because she implemented age- appropriate critical literacy activities in her curricula and helped her students to revisit texts and explore diverse perspectives. There were twelve, five-year-old kindergartners in Ms. Choi’s classroom, and all of them participated in this study. They came from similar cultural, linguistic, social, and economic backgrounds: all of them were of Korean ethnicity and came from middle- to upper-middle-class families in South Korea. Table 1 exhibits the details of each child (See Table 1).

Having majored in early childhood education, Ms. Choi had a total of 8 years in preschool and kindergarten classrooms. Although she had not received specific training relating to critical literacy pedagogies, her previous teaching experience highlighted the importance of critical thinking in learning. As an experienced teacher who utilized a socio-constructivist learning method, she highlighted “the process” rather than “the product” of learning. Ms. Choi indicated that during her college years, she had a chance to develop some teaching strategies that can help young children to talk about what they read and think critically. In her current classroom, she often used the teaching strategies that she developed and modified, with a goal to help her students make connections with the story based on their own prior knowledge, and ultimately, to improve their critical thinking skills.

Focal Literacy Activity

The focal literacy activity, which was called “counter- storytelling activity,” was implemented during the large group learning time. Ms. Choi incorporated it in connection to a multimodal writing approach in her classroom as a way to create a space for facilitating the children’s critical engagement with fairytales. Her rationale of this activity was to provide the children with the chance to think about fairytales from alternative perspectives and to explore multiple viewpoints, rather than simply conforming to the author’s voice. For the counter-storytelling activity, the teacher and the children read fairytales together and had in-depth conversations about the stories. If a different version of the original story was available, the teacher read it as well, and compared the two versions with using a Venn Diagram. During reading, she occasionally stopped reading to help her students, in order to make connections with the story based on their prior knowledge. When they finished reading, the teacher asked the children thought-provoking questions to deepen their thoughts on the reading, focusing on how the story would be told differently if it was narrated by a different character. She also invited her students to add detail to their responses and to share their views with peers.

After finishing the initial conversation about the fairytale, the teacher provided the children with a blank sheet of paper, crayons, colored pens, and other art materials, and the children freely created their own stories through drawing based on the perspectives that they chose. During this portion of the activity, the teacher encouraged the children to perceive the text in a different way and to develop their own ideas, rather than simply conforming to the author’s voice. With the teachers’ assistance, the children created a new story, their own re-telling, on a blank sheet of paper.

Throughout the five-month observation period, the teacher read a total of eight fairytales using the counter-storytelling instructional method outlined and 96 drawings were created during the eight sessions. All of the children were familiar with the stories, as they read them at home with parents. Taking into account the large volume of data obtained and the limited space in this article, this dissemination details data specific to the children’s engagement with three fairytales. Table 2 displays the title of each fairytale text and some sample critical literacy questions that the teacher asked to the students during/after reading (See Table 2).

Data Collection and Analysis

Data Collection Procedure

Data for this article came from a larger study that used a qualitative case study approach (Dyson and Genishi 2005; Stake 2005), with an aim to capture the complexity of the children’s negotiations and representations of their voices. Multimodal data were collected over the course of a semester through classroom observations, one-to-one interviews with the parents and the teacher, observational field notes, and children’s artifacts. The process of collecting data followed the guidelines of the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation; child assent and permission was received from the parents, as well as the children. Since this study involved young children, a parental consent letter was sent to the children’s parents prior to the program, and all of the parents agreed to have their children participate in the project. During the observation period, the critical literacy activity was observed and video and audio recorded for a total of two hours per week, focusing on the children’s responses to fairytales and their social interactions with peers and the teacher during the counter-storytelling activity.

Semi-structured, one-on-one interviews were also utilized extensively with the parents and teacher, based on the technique of Seidman’s model (2013) of phenomenological interviewing. To address all of the research objectives and to ensure high quality interviews, an interview protocol was designed before conducting interviews, as outlined by Patton (2015) and Castillo-Montoya (2016). This interview protocol was refined through interview protocol refinement steps, which included the refinement of the proposed questions from formal academic language to daily conversation discourse. Also, to ensure the interview protocol feasibility, research questions were reviewed by research colleagues, focusing on the protocol structure, length, and ease of understanding. Two interviews, for 30 min each time, were conducted with the teacher, one at the beginning of the program and the other at the end. The first focused on the teacher’s teaching philosophy and experience and the goals of her critical literacy curricula. The second centered on the benefits and her concerns in implementing the critical literacy activities in her classroom. Three participating children’s parents were interviewed, following Creswell’s (2015) sampling strategy. The interviews with the parents were conducted for 20–30 min at the end of the program, focusing on their experiences in reading with their children at home, as well as their efforts to teach critical thinking skills in reading. All questions were created in advance, yet several follow-up questions were asked based on each participant’s answers. Also, following Emerson et al. (2011), field notes were created focusing on the children’s story discussions, behaviors afterwards, and their engagement in their own written texts in response to the readings. Table 3 displays the details of data collection process (See Table 3).

Data Analysis

Data analysis was based on a thematic approach to determine patterns and to examine the essential elements of the phenomena (Patton 2015; Stake 2005). Within the grounded theory approach, data analysis was conducted based on a thematic analysis, which entailed a four-step process. The first phrase of analysis involved the initial review, followed by preliminary coding methods (Emerson et al. 2011). After each observation or interview, all of the collected audio or video data were transcribed into written form, and literacy activities were grouped together and coded, using open-coding. By conducting line-by-line and whole-document analyses, the data was coded into meaningful segments using a descriptive code that could summarize the topic of the excerpt, and 137 codes were developed.

The second step consisted of identifying key concepts to find reoccurring themes and to unpack the interconnectedness among the codes. After the data were pulled apart and meaningful segments were identified (Patton 2015), an axial coding method (Corbin and Strauss 2008) was used to make connections among the open codes and find integrity across the data. Through inductive and iterative readings of these codes, the researchers identified relationships among the open codes, and found 25 emergent themes. Then, flexible categories were generated to integrate newly emergent themes into the initial categorization scheme. Table 4 exhibits the themes emerged in eight fairytales, and Table 5 displays the examples of theme categories (See Tables 4, 5).

In the third stage, the study employed Gee’s (1999) discourse analysis to examine high inference meanings. The focus was on how the children negotiated and (re-) produced their stories by bringing up their personal and cultural experiences and socially interacting with peers. Using context-based discourse analyses, the researchers analyzed each child’s literacy environment, time, and place in which the discourse occurred, as well as the relationships among the children and their culture, customs, and family backgrounds. Then, some focal interactions that seemed to best answer the research questions were selected based on the research questions.

The final stage involved triangulating data sources to increase internal validity of the data analysis and to enhance reliability (Hamel 1993; Kirk and Miller 1986). In order to validate the consistency of findings generated by different data collection methods, multiple sources of data, such as classroom observations and participant interviews, were compared and contrasted. Also, all of the coding of the data and the analysis were shared with other professionals to confirm the categories and themes across the different cases, to gain additional insights and to reduce potential bias. Moreover, a prolonged engagement (Creswell 2015) was employed to understand children’s social settings and to develop rapport and trust with them. The data analysis process is summarized in the following table (See Table 6):

Findings

As a pedagogical tool for facilitating children’s critical engagement with literature, the counter-storytelling activities provided the children with a valuable opportunity to read between the lines, to form alternative explanations, and to “talk back to text” (Enciso 1997). The children were able to playfully manipulate the story using their creativity and imagination, as the teacher helped them to deconstruct the original story, to explore previously unheard voices, and to examine multiple viewpoints. With deliberate effort made by the teacher, the children played with themes and messages embedded in the fairytales, and recreated the stories with their own voices through drawing. The following sections detail three of the episodes, and illustrates how the children’s creative, multimodal participation led to the recreation of the stories in critical and genuine ways.

“I Can Teach Cinderella Korean”: Exploring Alternative Endings in Cinderella

Critical conversations about the ending of Cinderella (Disney Storybook Art 2014) encouraged the children to approach the story from a different angle and analyze it from multiple perspectives. In the original version, Cinderella is a passive victim who suffered from a wicked stepmother and stepsisters. However, the children were able to begin to reexamine the story as they investigated it critically by having in-depth conversations with peers and the teacher. Following is the example of how the teacher initiated the discussion with the children about alternative endings of Cinderella in a critical and creative wayFootnote 1:

Teacher: (Pointing out Cinderella on the last page) Look at her. She looks so happy. So, why is she happy now?

Soyoung: (Raising a hand) She got married with the prince!

Teacher: Right! she got married, so she is happy now. But what if Cinderella never met the prince? Do you think she would never be able to be happy?

Children: (Thinking)

Heesun: She still would be happy at the end.

Teacher: Good Heesun! Why do you think so?

Heesun: (After a while) Just because. (with a quiet voice) Well, I don’t know.

Teacher: (to Heesun) Ok, you think Cinderella would be still happy at the end even without the prince. How do you think Cinderella would be happy on her own?

Children: (thinking)

Soyeon: By becoming a famous person.

Teacher: Oh, so do you mean she would be happy if she becomes famous?

Soyeon: (Nodding affirmatively)

Teacher: Yes, if you become famous, you are more likely to be happy. Then, how would Cinderella be able to become famous? Yes, Minwoo.

Minwoo: (with an excited voice) She can study hard!

Teacher: Right, she can be famous by studying hard. That is a good idea. Then, what study? What do you think Cinderella can study about? Yes Jaesung.

Jaesung: She can study Korean. I can teach her Korean!

Teacher: I love that idea! You would be a great Korean teacher Jaesung!

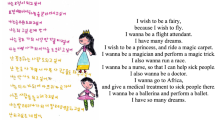

Marriage is often depicted as an important medium for “a happy ending” in fairytales. Yet, by working together to deconstruct the story, the children could explore alternative ways of achieving happiness, as the teacher asked thought- provoking questions about how Cinderella could have overcome her hardship differently. With the teacher’s question, the children playfully manipulated the story based on the original plot: Soyeon and Minwoo suggested that education would be a great way for Cinderella to overcome her difficult situation, and the other children supported their idea by adding more details. Jeasung, for example, indicated that Cinderella could study a Korean language, whereas Dongsoo and Junghee pointed out that learning how to ride a horse or make a robot would be great educational opportunities for her. Such ideas were also reflected in their own written texts that were depicted through original artwork (see Fig. 1).

Jaesung chose the theme of “language exchange” and drew about Cinderella’s learning Korean from him and his learning English from her. Unlike Jaesung, Junghee focused on the theme of horseback riding, and created a story of Cinderella taking riding lessons and becoming a world- famous horse rider. Dongsoo also re-scripted the story creatively, saying, “Cinderella is learning how to make a robot to be a robot scientist, and my best friend Taesung and I are helping her.” The children’s own stories suggested “alternative happy endings,” focusing on how Cinderella could overcome her difficult situation by her own power, rather than being rescued by Prince Charming.

“I Think Jack is a Burglar”: Reexamining Jack in Jack and the Beanstalk

Critical dialogues were sometimes initiated by the children themselves; their critical engagement was observed when they had a conversation about Jack and the Beanstalk (Geylim Books 2004). While the original story portrayed Jack positively as a “kind-hearted” and “affectionate” boy, the children reexamined him from different perspectives. The following excerpt exhibits the children’s critical dialogue about the legitimacy of Jack’s act in the giant’s castle:

Teacher: So, what happened in the story?

Soyoung: Jack took the giant’s hen and harp.

Dongsoo: (Raising a hand) But teacher! Stealing is a bad thing.

Teacher: Right! Stealing is a negative behavior. Thank you for bringing up that issue, Young. Yes, Jack took the giant’s hen while the giant was gone. Look at this hen! It lays eggs made of gold!

Children: (Looking at the illustration of the hen)

Teacher: So, what if you found this hen in the giant’s castle? Do you think you would also take it like Jack?

Soyoung: Well, the giant is a bad guy so.. (with a quiet voice) it is “maybe” fine. But I will bring it to my mom.

Teacher: Ok Soyoung. So, you think the giant is bad so it would be fine to take his belongings. Then, why do you think he is a bad guy? Did he do something bad to Jack or villagers?

Soyoung: (Thinking)

Teacher: Let’s think about what the giant did in the story. What did he do before Jack broke into his castle?

Sunhee: He was outside.

Teacher: Right. He was outside, and when he came back home, he found out that somebody broke into his castle. How would you feel if you noticed somebody broke into your house while you were gone?

Dongsoo: Angry.

Soyoung: Scared.

Teacher: Yes, he must be angry and scared too.

Minsun: (Raising a hand) I think Jack should have asked the permission from the giant before entering his house.

Heasun: (Raising a hand) And before taking his treasures.

Dongsoo: Jack is a burglar!

In the excerpt above, Dongsoo questioned the validity of Jack’s act, as he found that Jack’s behavior in the giant’s castle contradicted common moral values. Such critical question enabled the children to assess Jack’s behavior more objectively and to look at the story from different viewpoints, focusing on the giant’s situation and feelings when his treasures were stolen. For example, Minsun brought up the issue of the importance of asking permission from the owner, and Dongsoo supported her view, indicating Jack was “a burglar.” The children also attempted to represent the giant’s voice and frustration in their drawings (see Fig. 2).

Somin created the story of how the giant could have better secured his possessions by training his hen to push “112” to call the police.Footnote 2 Sungwon also focused on the security issue, indicating that “the giant hides his hen and harp in a small box with burglarproof locks to secure them, and put them inside dragon and dinosaur sculptures.” While Sungwon thought about how to better hide his treasure, Minwoo suggested a more active way of protecting the castle to secure his ownership: in his story, he arranged diverse protecting devices in front of the castle such as robots, solders, and security dragons, so that nobody would be able to reach it. These stories focused on the giant’s situation and perspective, rather than Jack’s quest to obtain the giant’s treasure.

“The Wolf Eats only Veggies”: Rethinking the Wolf in Little Red Riding Hood

The critical literacy activity also helped the children to critically examine previously unquestioned dominant ideologies in fairytales. This was particularly evident when the children talked about how wolves were portrayed in two different versions of Little Red Riding Hood (Jikyungsa 2006). Followed by reading the original story, the children had a chance to read another version, The Story of Little Red Riding Hood: From the wolf’s perspective (Shaskan 2014). While “the big bad wolf” in the original story was described as a sly character that gained entry to the girl’s grandmother’s house by pretending to be Red Riding Hood, the wolf in the other version was a vegetarian, and he did not intend to scare or harm Red Riding Hood and her grandmother. Through listening to different voices of wolves, the children were able to critically examine how wolves were portrayed differently in the two stories:

Teacher: We have two wolves here. So, what do you think about the wolf in the first story?

Soyoen: He is bad because he went to the grandma’s house and swallowed her!

Teacher: Right! He was bad. Then, what about the wolf in the other story?

Taemin: He eats only veggies.

Teacher: Yes, he was actually a vegetarian who can eat only vegetables. Do you think that the second wolf is also “bad” like the first one?

Taemin: That wolf is...(murmuring) maybe not bad because he was just confused.

Teacher: Right, the second wolf was confused with the girl’s red hood and an apple.

Soyeon: He didn’t mean to scare her!

Teacher: Yes, he didn’t mean to scare Red Riding Hood.

Taemin: (Raising a hand) I think the second wolf is fine.

Teacher: Ok. So, you guys think the first wolf is bad but the second one is maybe ok. Right? Does anyone think the second wolf is also bad?

Children: (quiet)

Teacher: Ok, some wolves are bad like the first one but we have good wolves too. Then, how would the first story have been different if the wolf in the story were good?

Children: (thinking)

Teacher: Do you think the story would be the same if it was a “good wolf”?

Soyeon: They would get along with each other.

The teacher then encouraged the children to think about similarities and differences between the two wolves using a Venn Diagram and asked questions such as how the original story could have told differently if Red Riding Hood had met a “good” wolf in the forest. This offered the children the chance to not only deepen their understandings of the cause and effect of each story, but also to speculate about the dominant image of wolf. Drawing followed by the discussion also provided the children with valuable opportunities to rethink the story and create version in their own voices. In the children’s new stories, the wolf was a friendly character who got along with Red Riding Hood and her grandmother (Fig. 3).

In Soyeon’s story, “Red Riding Hood and grandmother invited the wolf in their house, and served him a nice meal with a lot of veggies.” The wolf in Minsun’s story was also not a scary character anymore. Her story went: “The wolf goes to the same school with Red Riding Hood, and he is studying, playing puzzles, and learning songs with her.” Taemin also focused on the theme of “playing,” and drew about the day that Red Riding Hood, her grandmother, and the wolf were having fun together, playing and swimming near a stream.

Like the example data provided, the children’s stories throughout the entire data collection period were full of creativity and imagination. As the teacher created a space for relaxation and a sense of adventure through counter-storytelling, the children were able to examine alternative perspectives in texts and explore multiple interpretations. During an interview with the teacher, she also highlighted the pedagogical possibilities of counter-storytelling as an important method to help young children to deepen their thoughts on the reading and to explore diverse perspectives:

Teacher: Children are full of creativity, and they are often expressing their creative ideas in different ways, like play and drawing. I believe that teachers play a critical role in the development of student creativity. Through the counter-storytelling activity, I aimed to foster children’s critical and creative thinking skills, and I believe that it really helped the children to think critically and creatively. People might think that this kind of critical literacy activity is effective in classrooms for older students, but I think this practice can be implemented in any classrooms. With an appropriate support from teachers, young children are very capable of having critical conversations about literature and creating their own story.

Interviews that were conducted with parents after the program also supported the potential benefit of counter-storytelling as an early critical literacy practice. The following two excerpts reveal such support:

Taemin’s mother: I remember that Taemin talked about the counter-storytelling activity they did at school. He showed me his drawings and explained how his version is different from the original story. It seemed that he really enjoyed the activity and liked his version of story. Actually, I rarely read classic books to my children, because the morality in fairytales seems too outdated (but personally, I still love fairytales). I think the activity is a great way to perceive fairytales in a different way.

Minwoo’s mother: One of the biggest changes that I observed was that Minwoo started to ask questions during and after reading. He used not to ask questions when I read a book to him, but he started to ask some questions such as, “Why did the character act that way?” He also started to make comments more often, like “I think that is wrong” and “I like that.” His questions make our reading time more enjoyable. I really enjoy his creative and unpredictable comments.

In the interviews, the parents indicated that their children started to ask critical questions about what they read, and expressed their ideas in a creative way, voicing their responses, instead of simply conforming to the author’s voice. The parents also stressed that such positive changes helped them to have more critical conversations about the story with the children—such as why they liked or did not like the story, and how the story could be told differently from different angles.

Discussion

The current study investigated preschool children’s critical engagement with fairytales through counter-storytelling. In the examples provided, Ms. Choi engaged the children in counter-storytelling aimed to promote meaningful comprehension and creative exploration of texts. While agreeing and disagreeing with each other’s perspectives, the children developed their literary responses from “monologic” to “dialogic” (Beach 1993, p. 112). Through the give and take between the teacher and peers, students experienced mutuality (Goss et al. 2002), whereby each person explored their own and other’s ideas. The way in which the children investigated the plots and authored original stories by interacting with the peers and the teacher suggests that early critical literacy is a social practice enacted and formulated through social interactions. This finding also suggests that preschoolers are powerful storytellers, and they are capable of creating, recreating, and negotiating meaning.

Second, the findings support both the use of counter-storytelling in early literacy classrooms, as well as the recent view of children as powerful storytellers (Kelly 2017; Kim 2019). Stories, both told to and made up by children, serve to shape their perceptions of reality (Marshall 2016; Solórzano and Yosso 2002). Brown (2008) assets that the basic unit of human intelligibility is a story; everyone has an internal narrative that is our own inner story. This can be seen when engaging preschoolers with literature; children tend to speak candidly and openly share their responses to texts (Kelly 2017). The teacher in this study deliberately sought through open-ended questioning to not only aid examination of the fairytales but also to provide the children opportunities to practice and refine their listening and speaking skills. In this classroom, reading was not a fixed and stable investigation, as the children deconstructed the original narrative and explored multiple perspectives through collaborative language interactions. As active social participants, they read further and beyond the text (Huang 2011) and recreated it with their own voices. The finding suggests that counter-storytelling in early childhood classrooms is an effective tool to empower young children to analyze and critique story elements and draw personal meaning from texts.

Exploring nonconforming explanations of character motives and endings in fairytales can be a powerful tool for empowering children to make inferences and predictions, compare and contrast information in the text, and analyze and critique story elements (Kelly and Moses 2018). By having children participate in guided discussion and creation of their own stories, early childhood teachers can help children expand perspectives to allow viewing of typical events in atypical ways. Moreover, it offers a rich context in which to practice deconstructing the dominant discourses implicit in an author’s words; learning to tell their own stories and accept the counter-stories of their peers prepares young children for well-reasoned, civil debate in a diverse society (Kelly 2017).

The study also supports the findings of prior studies that argue that preschoolers are multimodal interpreters of their world (e.g., Albers and Sanders 2010; Dyson 2008). Young children’s understanding of texts can be enhanced with their artistic endeavors in drawings (Leland et al. 2005). In this study, Ms. Choi did not privilege decoding/producing written language over other symbol systems in order to connect to the children’s prior knowledge and to build their understanding of the ideas, topics, and words in the fairytales explored. She provided the children opportunities to call on varied semiotic resources to recreate the fairytales (i.e., oral language and drawings). Given this multimodal literacy experience, the children’s own stories emerged in different forms, including narrative, writing, and drawing, allowing them to explore a range of communicative forms in relation to the original text. Such findings highlight a multimodal perspective of literacy, whereby literacy instruction accounts for the multifaceted ways that language can be expressed.

Implications

The participating children’s critical engagement with fairytales through counter-storytelling activities provides three important lessons for early childhood teachers. First, it is an important part of early literacy education to engage in diverse ways of meaning-making, rather than by adopting unitary, monolithic, and fixed points of view. Children’s literature represents specific ideological representations of reality (Nodelman and Reimer 2003). Exploring nonconforming explanations of character motives and endings in fairytales can be a powerful tool for empowering children to make inferences and predictions, compare and contrast information in the text, and analyze and critique story elements (Kelly and Moses 2018). By having children participate in guided discussion and creation of their own stories, early childhood teachers can help children expand perspectives to allow the viewing of typical events in atypical ways. Thus, it is important that, when early childhood teachers involve young children in counter-storytelling activities, they create a fluid and multifaceted space where young children freely share their ideas. It is also crucial that they understand the transformative power of telling a story that reflects one’s own experiences, and acknowledge the “funds of knowledge” that preschoolers bring to a literacy learning experience [i.e., the prior knowledge young children already have because of their roles in their families, communities, and cultures] (Gonzalez et al. 2005).

The study also suggests that it is vital to value young children’s voices as storytellers and to foster an environment in which children are encouraged to “talk back” (Enciso 1997) to texts. Well-planned critical literacy activities, such as those that focus on counter-storytelling, can serve as a medium to help them read and write “against” texts and analyze them from multiple perspectives (Kim 2016, 2019; Vasquez 2014). Counter-storytelling activities offer a rich context in which young children practice deconstructing the dominant discourses, learn to tell their own stories and learn to listen to the stories of others. Since knowledge is socially constructed, it is important for teachers to help young children to grow up as critical thinkers by creating an inclusive space where every child feels safe to speak up and contribute ideas based on his/her views.

Lastly, this study suggests that it is important for teachers to incorporate a multimodal pedagogical approach in their literacy curricula and to help young children use a variety of symbolic modes in their meaning making. Young children create meaning not just with words, but rather by using different modes of semiotic resources-pictures, gestures, full-body movement, and music (Albers and Sanders 2010; Siegel 2006). Every child has distinctive perspectives and social experiences, and such experiences are expressed in multimodal ways (Dyson 2008; Wright 2010). Thus, in order to better support young children’s critical thinking, teachers should use a variety of multimodal ways, utilizing diverse materials. Using diverse communitive modalities allows teachers to position preschoolers as apt meaning makers, capitalizing on the “well-stocked semiotic tool kits” (Siegal 2006, p. 69) they bring to early literacy experiences.

Limitations and Future Directions

The results of this study show the possibility of incorporating early critical literacy practices, specifically counter-storytelling, to enhance young children’s critical engagement with traditional children’s literature. Since inclusion of early critical literacy in school curricula is exceedingly rare, the findings of this study will be beneficial for both early childhood teachers and literacy educators. Yet, in making this claim, the researchers acknowledge some methodological limitations of case study associated with the issues of subjectivity and generalizability. In this study, the focal children were from affluent families with college-educated parents, and thus their relevance may not extend directly to different socio-economic contexts. Also, the case investigated for this study was not representative of a wider body of similar instances in different countries. The methodological limitations call for robust research on early critical literacy practices in different racial, ethnic, socio-economic, and cultural settings.

Conclusions

According to the National Education Association (2012), one of the important instructional goals of literacy curricula in the twenty-first century is to equip students with critical thinking skills such as questioning, predicting, analyzing, comparing, evaluating, and forming opinions. In order to meet the demands of twenty-first century early literacy instruction, early childhood teachers need to encourage children to think critically and creatively through developmentally, culturally, and linguistically appropriate curricular activities (Kelly and Moses 2018; Kim 2016). To this end, teachers should create a fluid and dynamic literacy atmosphere where young children explore their voice in exciting, intriguing, and multimodal ways (Lenters and Winters 2013). Counter-storytelling, as a critical literacy practice, can offer early childhood teachers a rich context for early instruction by positioning preschoolers as capable critical literacy thinkers, powerful storytellers, and multimodal meaning-makers.

Notes

The conversation was spoken in Korean originally but translated into English by a third person. The accuracy of the translation was checked through official Korean Translation Services.

112 is an emergency police phone number in Korea.

References

Albers, P., & Sanders, J. (Eds.). (2010). Literacies, the arts and multimodality. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Beach, R. (1993). A teacher’s introduction to reader-response theories. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Beach, R., & Freedman, K. (1992). Responding as a cultural act: Adolescents’ responses to magazine ads and short stories. In J. Many & C. Cox (Eds.), Reader stance and literary understanding (pp. 162–190). Norwood, NJ: Alex Publishing Corporation.

Beck, A. S. (2005). A place for critical literacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 48(5), 394–400.

Books, G. (2004). 잭과 콩나무 [Jack and the Beanstalk]. Seoul: Geylim.

Brooks, W., & McNair, J. C. (2009). “But this story of mine is not unique”: A review of research on African American children's literature. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 125–162.

Brown, S. (2008). Play is more than fun. TED Talk. Retrieved from: https://www.ted.com/talks/stuart_brown_says_play_is_more_than_fun_it_s_vital#t-566747

Castillo-Montoya, M. (2016). Preparing for interview research: The interview protocol refinement framework. The Qualitative Report, 21(5), 811–831.

Crawford, P. A., & Hade, D. H. (2000). Inside the picture, outside the page: Semiotics and the reading of wordless picturebooks. Journal of Research in Childhood Education., 15(1), 66–80.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2015). Educational research. Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Delgado, B. D., & Villalpando, O. (2002). An apartheid of knowledge in the academy: The struggle over "legitimate" knowledge for faculty of color. Equity and Excellence in Education, 35(1), 169–180.

DeWaelsche, S. A. (2015). Critical thinking, questioning and student engagement in Korean university English courses. Linguistics and Education, 32, 131–147.

Disney Storybook Art. (2014). 신데렐라 [Cinderella]. Seoul: Dreaming Snail.

Docherty, S. (2014). 5 Reasons why fairy tales are good for children. Retrieved from https://www.scottishbooktrust.com/blog/reading/2014/06/5-reasons-why-fairy-tales-are-good-for-children.

Dooley, C. M., & Matthews, M. W. (2009). Emergent comprehension: Understanding comprehension development among young literacy learners. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 9(3), 269–294.

Dozier, C., Johnston, P., & Rogers, R. (2006). Critical literacy/critical teaching: Tools for preparing responsive teachers. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Dyson, A. H. (2008). Staying in the (curricular) lines: Practice constraints and possibilities in childhood writing. Written Communication, 25(1), 119–159.

Dyson, A. H., & Genishi, C. (2005). On the case. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Enciso, P. (1997). Negotiating the meaning of difference: Talking back to multicultural literature. In T. Rogers & A. O. Soter (Eds.), Reading across cultures: Teaching literature in a diverse society (pp. 13–41). New York, NY: Teachers College.

Fish, S. E. (1980). Is there a text in this class?: The authority of interpretative communities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Contimuum.

Gee, J. P. (1999). An introduction to discourse analysis theory and method (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Gonzalez, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2005). Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing practice in households, communities and classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Goss, M., Galbraith, P., & Renshaw, P. (2002). Socially mediated metacognition: Creating collaborative zones of proximal development in small group problem solving. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 49, 193–223.

Hamel, J. (1993). Case study methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Hamilton, M., & Weiss, M. (2005). Children tell stories. Teaching and using storytelling in the classroom. Katonah, NY: Richard C. Owen.

Hour, H. (2000). Dynamic aspect of fairy tales: Social and emotional competence through fairy tales. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 44(1), 91–105.

Huang, S. (2011). Reading “further and beyond the text': Student perspectives of critical literacy in EFL reading and writing. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 55(2), 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/JAAL.00017.

Jewitt, C. (2008). Multi-modal discourse across the curriculum. In M. Martin-Jones & A. De Mejia (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education, discourse and education (pp. 357–367). New Jersey, NY: Springer.

Jikyungsa. (2006). 빨간 모자 [Little Red Riding Hood]. Seoul: Jikyungsa.

Johnson, D. (2012). The joy of children’s literature. Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Kelly, L. B. (2017). Welcoming Counter story in the primary literacy classroom. Journal of Critical Thought and Praxis, 6(1) Article 4. Retrieved from: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1124&context=jctp

Kelly, L. B., & Moses, L. (2018). Children’s literature that sparks inferential discussion. Reading Teacher, 1, 221–229.

KICCE (2013). Policy brief. Retrieved from https://kicce.re.kr/eng/newsletter_mail/pdf/201401_brief.pdf.

Kim, S. J. (2012). Critical literacy in East Asian literacy classrooms. Perspectives on Global Development and Technology, 11(1), 131–144.

Kim, S. J. (2016). Opening up spaces for early critical literacy: Korean kindergarteners exploring diversity through multicultural books. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 39(2), 176–187.

Kim, S. J. (2019). Children as creative authors: The possibilities of counter-storytelling with preschool children. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 55(2), 72–77.

Kirk, J., & Miller, M. L. (1986). Reliability and validity in qualitative research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Kress, G. (2009). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London, UK: Routledge.

Lee, H. J., & Lee, J. (2012). Who gets the best grades at top universities? An exploratory analysis of institution-wide interviews with the highest achievers at a top Korean University. Asia Pacific Education Review, 13(4), 665–676.

Leland, C., Harste, J., & Huber, K. (2005). Out of the box: Critical literacy in a first-gradeclassroom. Language Arts, 82(5), 257–268.

Lenters, K., & Winters, K. (2013). Fracturing writing spaces: Multimodal storytelling ignites process writing. Reading Teacher, 67(3), 227–237.

Lewison, M., Leland, C., Harste, J., & Christensen, L. (2015). Creating critical classrooms: K-8 reading and writing with an edge. New York, NY: Routledge.

Love, B. J. (2004). Brown plus 50 counter-storytelling: A critical race theory analysis of the “majoritarian achievement gap” story. Equity & Excellence in Education, 37, 227–246.

Marshall, E. (2016). Counter-storytelling through graphic life writing. Language Arts, 94(2), 79–93.

McLaren, P. (2007). Life in school. Los Angeles, CA: Pearson.

Moller, K. J. (2004). Creating zones of possibility for struggling readers: A study of one fourth graders’ shifting roles in literature discussions. Journal of Literacy Research, 36(4), 419–460.

National Education Association. (2012). Preparing 21st century students for a global society: An educator's guide to “the four Cs.” Retrieved from https://www.nea.org/assets/docs/A-Guide-to-Four-Cs.pdf.

Nodelman, P., & Reimer, M. (2003). The pleasures of children’s literature. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Panca, I., Georgescub, A., & Zahariab, M. (2015). Why children should learn to tell stories in primary school? Social and Behavioral Sciences, 187, 591–595.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shaskan, T. S. (2014). 늑대가 들려주는 빨간모자 이야기[The story of Little Red Riding Hood: From the wolf’s perspective]. Seoul: Kids M.

Seidman, I. (2013). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in Education and the Social Sciences (4th ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Siegel, M. (2006). Rereading the signs: Multimodal transformations in the field of literacy education. Language Arts, 84(1), 65–77.

Sipe, L. (2000). The construction of literary understanding by first and second graders in oral response to picture storybook read-alouds. Reading Research Quarterly, 35(2), 252–275.

Sipe, L. (2008). Storytime. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Solórzano, D. G., & Yosso, T. J. (2002). Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 23–44.

Stake, R. (2005). Multiple case study analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sung, Y. K., & Apple, M. W. (2003). Democracy, technology and curriculum: lessons from the critical practices of Korean teachers. In M. W. Apple (Ed.), The state and the politics of knowledge (pp. 177–192). New York, NY: Routledge.

Vasquez, V. (2014). Negotiating critical literacies with young children. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Virtue, D. C., & Vogler, K. E. (2009). Pairing folktales with textbooks and nonfiction in teaching about culture. Social Studies and the Young Learner, 21(3), 21–25.

Wright, S. (2010). Understanding creativity in early childhood: Meaning Making and children’s drawing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S.J., Hachey, A.C. Engaging Preschoolers with Critical Literacy Through Counter-Storytelling: A Qualitative Case Study. Early Childhood Educ J 49, 633–646 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01089-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01089-7