Abstract

Recent study on gender representation in children’s literature has focused on the representations themselves, while there is less research regarding how children talk about these depictions in texts. Our work, a qualitative study of how kindergarten-aged children discuss gender during picture book read-alouds, examined how children drew on the social binary of boy/girl as they made sense of the human and non-human characters’ identities. The study looked at how children responded to questions about gender across both ambiguously-gendered characters and texts where gender norms were deliberately questioned. The findings expressed in this paper provide insight into how students’ previous experiences, along with classroom norms and text choice, influence student response. Specifically, we found that children drew on similar social norms and gendered expectations across all character types, demonstrating the importance of these societal categories on their comprehension of texts and on their sense-making of their lives and classrooms. The paper ends with implications for early childhood educators in allowing for more diverse representations when selecting texts and deliberate listening to student conversations to recognize how young learners perceive gender and identity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“There’s no such thing as a girl thing or a boy thing.”

-Janine,Footnote 1 Age 5

The above quote was uttered by a kindergartner during a discussion of which toys are appropriate for children to play with. These words echo the sentiment spoken by many children in early elementary settings: that individuals can participate in whatever activities they choose, dress however they feel comfortable, and identify in ways that they feel authentic to themselves. Despite these expressions of equity and inclusion, the reality is that, under the surface, students’ perceptions and actions demonstrate a real and maintained systemic adherence to gender binaries (boy/girl, male/female). While children often know what they are ‘supposed to’ say, school spaces often maintain the gender norms of either/or identities—in bathrooms, classrooms, and hallways—to the detriment of children whose identities do not match these expectations (Drake et al. 2003). In many spaces, society embraces a wider range of gendered identities, how individuals present and describe their own sense of gender; therefore it is critical that the field of early childhood education also openly embrace these contexts in order to make schools safe and inclusive to all students.

For many years, the use of the term ‘gender’ was synonymous with biological sex (Francis and Paechter 2015); this trend created a widely-accepted social understanding that there are boy things and girl things, and that all students must fall into one of those categories, or boxes. Through socialization through media and home life experiences, young children enter school spaces with this binary in mind. The choices that educators make during day-to-day activities such as play and instruction, can lead to either maintain this view of gender, or push towards a more nuanced understanding of identity. As one of the goals of early childhood education is to support students’ developing social and emotional awareness, issues of gender and acceptance are critical ones to address in these early school years.

Given the wide public discourse around gender in the United States, it is unsurprising that children come in with some knowledge of these topics or debates. In this study of children’s talk about gender representation in picture books, participants frequently cited this openness of identity by pointing out that there were no such things as girl things or boy things, and individuals had freedom of choice. However, when referring to texts such as books, movies, and other media, students referred to the social binary of boy/girl. As we explored how students frequently talk about gender in picture books where the characters were presented as ambiguousFootnote 2 or performing against this supposed binary, we began to question whether student responses and justification of claims changed when the characters were other than human—such as an anthropomorphized animal or object (what we refer to broadly as “non-human” in this paper). This study analyzed the reasoning behind student claims and assignment of gender based upon character type to better understand responses across human/nonhuman. This analysis is guided by the following question:

What evidence do young children draw on across character types, human versus non-human, when discussing gender in picture book representations?

Our findings indicate that children utilize similar meaning making strategies regardless of character type focusing primarily on what could be seen in the illustrations more than the words contained in the text. These findings have significant implications for how educators might use texts with both human and anthropomorphized characters to open up discussions of gender diversity and expression in early childhood educational contexts and gain a clearer insight as to how student reasoning has been informed.

Previous Research

Recent studies that have focused of gender in children’s picture books have looked specifically at bias and inequalities of representation within those texts towards a binary of male/female, boy/girl, and so on (Crisp and Hiller 2011; Mattix and Sobolak 2014). These works have shown that not only are there more male protagonists in high-quality children’s picture books, but those characters are given more interesting things to do than female or non-binary characters. Male gendered characters are permitted to solve their own problems, explore, and engage in adventurous activities. Female gendered characters are rarely the center of the narrative in these texts and are most frequently relegated to activities that maintain a binaried understanding of gender, where females are considered weaker, and not capable of performing such tasks, or given the opportunity to explore their own world. These studies focused on the content of these texts by looking specifically at surface level interpretations of the words and pictures. Very few studies exist which attempt to understand how early childhood students identify, problematize, and discuss gender in regard to representation. The larger study which this analysis is drawn from attempts to uncover and understand student talk about gender, performance, conformity and non-conformity.

Before students begin formal schooling, they are presented with representations of what it means to be a boy and girl, which can be understood as very specific features of masculinity and femininity (Blaise 2012; Crisp and Hiller 2011; Dutro 2016; Ryan et al. 2013; Smulders 2015). Through media, family interactions, and reinforced through constant reproductions of these performances in social settings, young children are given messages on what is appropriate for individuals of specific genders, while performances outside of these norms are often times considered rare, or even unfavorable. When students enter instructional settings, schools act as sites of reproduction in the way that teachers and administrators divide up play time materials, recess activities, and in responses to instructional inquiries (Sadker et al. 2009).

These perspectives are easily maintained as children tend to focus on what is real and concrete to them (Oakhill and Cain 2007). When understandings of what it means to be a boy and a girl are perpetuated through words and actions of peers, teachers, parents, and school personnel, students internalize and incorporate these ways of being into understanding as they are familiar to the students as being something they can recognize and accept. When other ways of performing gender are only talked about and not displayed in realistic, meaningful ways, then students will have a more difficult time of accepting these constructs. Because students are able to better internalize contexts with which they are already familiar, the binary is more readily maintained when texts, such as picture books, continue to portray gender identity as falling on either side of the supposed binary of boy things, and girl things. Texts that portray multiple ways of representing gender can allow students the opportunity to not only view other perspectives but allow for an opportunity to question previously held assumptions.

Picture books specifically provide a unique opportunity in student’s lives to act as windows, mirror, and/or sliding glass doors (Bishop 1990) from which to view their own lived experiences, and those of others. More simply put, texts can act as a mirror from which students can see a reflection of their lives. The characters may look and talk like them, have similar experiences and family structures. The lives of the students are reinforced in these contexts. However, this metaphor assumes that the reflected identity fits the view comfortably; in other words, for children with fluid gender identities, these ‘mirror texts’ might feel more like fun-house mirrors, where the perception of their reality is stretched or altered to match the status quo rather than representing them as they see themselves. When acting as a window, children’s literature allows individuals to look at the lives and experiences of others who may be different from them in simple ways, such as activities and family structures, to more complex instances such as language, socioeconomic status, or gender representation and performance. This metaphor implies that the student is able to comfortably remain in their own experiences without needing to question and remove themselves from their comfort zone. The most productive piece of this metaphor presented by Bishop is literature acting as a sliding glass door. While similar to a window in that a student may look upon other experiences and contexts, a sliding door would allow the student to move freely between their experiences and those of others. It is the intent of this metaphor that by moving between understandings, students will better understand the lives of others, thus creating a more robust and dynamic understanding of race, class, gender, and experience. Through exposure to different contexts through read alouds, students will be able to better understand experiences outside of former ways of knowing, both ones they can witness, and others they be experiencing for the first time. These texts can allow students to see individuals that may appear to be different due to social markers such as an opposing gender, but will then allow the individual to make connections along similar features of their lives that were not as explicitly known on the surface. Early childhood students will not be able to make these connections on their own, but need the opportunity to see others in contexts similar to their own.

Methodology

Participants

The larger study from which this analysis was drawn aimed to uncover how students talked about gender when the identity was not made clear by the characters, authors, or illustrators (Jacobs and Hill in press). Read alouds were conducted that took on an interactive theme that allowed students to engage in the conversation more openly than a traditional read aloud (Hoffman 2011; Sipe 2002, 2008). These literacy-based activities were conducted by the authors in the two kindergarten classrooms of a school in the Rust Belt region of the United States, using the methods and style of read alouds already familiar to the student participants. The school in which this study was conducted is a self-described progressive K-8 school. Twenty-four students were in each classroom and understood gender to be boy/girl as reported by the teachers. While our study revealed that some students were somewhat aware of gender variety, especially the idea of transgender, as discovered by students raising this topic during introductory activities, there was still a shared idea that eventually all people fit into either a male or female categorization. In Classroom A, 10 students identified as boys, and 14 as girls, while Classroom B had an even split at 12. The children’s reported gender identities were shared by teachers and families. While there were a range of racial identities, the majority of the children were White and almost all spoke English as their first language at home. Socioeconomic status was not collected as it was not directly relevant to this study.

Data Collection

The read alouds were conducted in both whole group, and small group settings. The students participated in a whole group reading at the beginning and end of the study, while also participating in up to four small group activities through the duration. The small groups included 6–8 students and were created by the classroom teachers. Prior to the official study, Author 2 was a regular visitor in the classroom, observing instruction and often engaging with students and teachers during instructional time. The study was conducted late in the school year, so we the authors deferred many decisions, such as group size and student placement, to the teachers as they had many months of experience with the students. In addition, the read aloud style was conducted to mirror what the classroom teachers do during literacy events (determined by observation of daily classroom interactions), and also following Sipe and Brightman’s (2009) protocols for conducting read-aloud research, which included allowing students to participate as they felt comfortable doing so, and foregoing some normal classroom requirements, such as raising their hands and remaining seated. Students were permitted to call out, discuss with peers, and approach the book to respond naturally within the literacy event, and also when responding to researcher inquiry and request. This was done in an effort to preserve student interest and excitement, while honoring their early age and development.

Prior to starting the read aloud sessions, students were informed that there was going to be a specific focus on thinking about whether characters were boys or girls or ‘not sure’, if the students were unable to assign an identity. This verbiage was used in response to the reporting of the classroom teacher that this was how the students had previously talked about gender in the classroom, as boy things and girl things. Students were also aware that we would be relying on their perceptions and understandings, and that the they would have the opportunity to discuss their thoughts and ideas during extended discussion sections. This was explained to the students so as to engage their thinking towards the overall goal of the read aloud task. It was believed by the authors that in doing so, students would be better prepared to talk about the subject matter allowing for more authentic responses.

Two rounds of texts were utilized in an effort to broaden the insight and perspectives of the students. The first set of texts were chosen as high-quality texts, using the selection as a Caldecott Award as our criteria. Specifically we then narrowed to texts whose main characters were ambiguous or ungendered (Crisp and Hiller 2011). These books were used to gauge how students identified and talked about gender when textual and illustrative clues were not present. Owl Moon (Yolen 1987) was read to the students in a whole group setting to introduce the activity and the overall study. My Friend Rabbit (Rohmann 2002) and The House in the Night (Swanson 2008) were both read in small groups. As described above, these read alouds occurred in smaller, more intimate settings where students had a greater opportunity to respond without the distraction and possibility of being overlooked in a whole class event.

The second set of texts, many of which were also Caldecott Award winners, were chosen for narratives that deliberately disrupted the boy/girl, male/female binary or addressed gender identity and representation specifically. These books were chosen to better understand how students addressed performance and identity when it was in conflict with their previous understandings as reported by the classroom teachers and staff. The texts included You Forgot Your Skirt Amelia Bloomer (Corey and Karlovitz 2000), William’s Doll (Zolotow 1972), My Princess Boy (Kilodavis 2011), The Worst Princess (Kemp 2012), Dogs Don’t Do Ballet (Kemp 2010) and Roland Humphrey is Wearing a What (Kiernan-Johnson 2012). All of the stories were read in small group settings, while Oliver Button is a Sissy (DePaola 1979) was read in large groups as a culminating activity toward the end of the data collection period.

Data Analysis

All read aloud sessions occurred in the spring of 2017 towards the end of the students’ school year and were audio recorded and transcribed by the authors. The documents were then uploaded into NVivo software and coded with an explicit focus on times when gender was discussed. We analyzed for themes that emerged from the data around children’s perceptions of gender, what aspects of the picture books they drew most heavily on for their understandings of characters’ gender, and on which conversations seemed to most promote gender equity and acceptance into the classroom. These findings were shared with the classroom teachers and the parents to foster an ongoing discussion regarding these topics in the classroom and the children’s homes.

We began with a priori codes based on our research questions and objectives and then did a cross-comparison analysis of the data to look for emic themes that emerged from the students themselves. Transcripts were coded by each author independently, the results of which were then compared between the two to ensure reliability in coding methodologies. Coding units (Miles et al. 2014) were then determined based on content analysis (Saldana 2016; Strauss and Corbin 1997). From these units, the codes found in Table 1 below show how conversations about gender identity and performance were framed during student led discussions, as well as through researcher guided prompts.

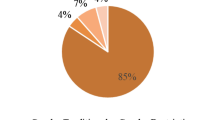

From this large-scale initial analysis (Jacobs and Hill in press), it was determined that students rely on social norms, binary, and stereotypes that authors and illustrators often employ for representing gender. These include the clothes that characters wear, the colors in which they are adorned, as well as the physical features of a character (Physical features: 31% of all visual codes; Clothing: 12% of all visual codes; Colors: 5% of all visual codes). It is also evident through this coding that the visual clues presented through the illustrations were more valuable to student understanding that the written text which was read aloud to the students.

For this article, we looked specifically at the ways students engaged in talk when the characters were human versus non-human, such as anthropomorphized animals and celestial bodies. The goal was to determine what similarities and/or differences may occur when the portrayal of the character changes from depictions that are typically gendered, to those characters that are not typically given a gendered identity. The data was pulled from the above coding system and sorted into the categories of human or non-human during this stage of analysis. We then completed another round of coding in which we specifically looked at the ways in which the children’s responses to human/non-human characters varied in terms of how they interpreted their gendered identities. Specifically, we were curious as to whether or not non-human characters allowed for a wider range of perceived gender representation.

Findings

Differences in Character Types

For the purposes of this article, we analyzed the utterances of gender into the categories of human and non-human. Human was defined as characters who were children or adults and presented in a way that is familiar to most children’s lived experiences, such as depictions of home life, engaging in play with other characters, wearing clothes, and attending school to name a few examples. Non-human characters were those instances when an animal, such as Rabbit and Mouse in My Friend Rabbit (Rohmann 2002) performed typically human traits of playing with toys, celebrating a special event, and problem solving. This label was also attached when animals were depicted performing in typical ways to their species, such as a cat caring for kittens, as was seen in The House in the Night (Swanson 2008). Within this same text, the sun and the moon were depicted as having human faces, which the students noticed and commented on regarding whether they thought it was a boy or a girl. While it is unknown if the author and illustrator intended to gender these portrayals, the students, having engaged in similar discussions for a number of sessions, assigned representation in those instances.

Once the utterances were separated by character type, the codes were then re-evaluated to determine how students discussed the gender and the associated performances of an assumed gender identity. Table 2 below displays the data across character types, specifically noting that the codes Physical Attributes, Social Constructs, and References to Illustrations as the three most commonly used codes for utterances about gender.

Upon analysis and discussion by the research team, two major findings were determined from this information. First, students relied heavily upon social norms and previous understandings of what are boy things and girl things, regardless of character type. As elaborated upon below, students discussed their perceptions of a character’s gender using similar evidence regardless if the portrayal is a child engaging in an outdoor activity with an adult, or a dog performing the final number in a ballet performance. The second finding directly relates to instruction, and the understanding that even when characters are presented without an assigned gender, students will engage in these conversations and focus on these identities as a way to make sense of the text.

Similarities Across Character Types

From this data, it can be determined that students rely on similar features of illustrated texts when assigning, rationalizing, and discussing gender and performance amongst the characters, regardless of type. Under the code Physical Attributes, for a human character, Sorrell elaborated, “So, what I was gonna say, was, not I actually think that her, um, this one’s the mom and this one’s the dad, and this one’s the little boy, because, um, now you can see them better.” Similarly, a child responding to My Friend Rabbit (Rohmann 2002) stated, “Um, because boy, um, um, because the Mouse, um the Mouse is, um, looks like a boy.” In both of these instances the characters were portrayed in ways that physically prompted the students to believe that they were male gendered. This was exemplified by pointing out while they knew boys who had long hair, it was usual for girls to have hair styles that were longer than males. In addition, during Owl Moon (Yolen 1987), students noted that girls tend to have paler faces, while boys are shown with having darker complexions. Other factors such as clothing or colors used for depictions were coded under those specific categories.

When discussing the Social Constructs that inform students notions of gender and performance during a read aloud of Dogs Don’t Do Ballet (Kemp 2010), a student commented, “Boys can wear tutus, but it’s usually only girls usually do it”. This was in direct reference to depictions of young children in a ballet class. When talking about Biff, the dog who wants to perform in a ballet, another child responded, “Well, boys can do ballet, like maybe it’s a girl.” In both these utterances, students acknowledge that males and boys can participate in ballet, but typically it’s only females who do so, and adhere to very specific standards of dress. These understandings did not vary between character types and were justifications for both human and non-human portrayals.

The code References to Illustrations was applied to utterances that were speaking directly to narrative features of the illustrations in the text. When the pictures added something to the understanding of the story, the students discussed the events that were being depicted. This code was used when students discussed multiple features of the illustrations, such as clothing and color rather than pointing them out individually. During the whole group reading of Owl Moon (Yolen 1987), Curtis pointed out, “…that the person was a girl, like with like yellow…colors and scarf and hats, and I think that’s a girl…that one’s a boy because, because like, girls use yellow and boys use red.” Later in that same text, Jody commented on the body posture of the human character by stating, “…I know it’s a girl because she bend [sic] down and put her hands together.” In these instances, multiple features informed their assignment of a gender that were depicted in the illustrative narrative put forth by the text.

These types of responses allow educators to see what stories a picture can tell, or what is missing if the visual is not enough. One student commented on the lack of visual features necessary for them to make a claim to the gender of a non-human character. While participating in a read aloud of My Friend Rabbit (Rohmann 2002) the following exchange occurred between the students and one of the authors:

Child: “We can’t tell because they don’t have clothes.”

A2: “Interesting. If they had clothes on would it be easier to tell if they were boys and girls?”

Multiple Children: “Yeah.”

Child: “Yeah cause of the colors and stuff.”

In this instance there was not enough information, either in the illustrations or the text for the students to adequately discuss the gender of the character thus adding to the finding that students rely heavily on social constructs and previous ways of knowing and talking about gender. Importantly, it was not the fact that the character was a mouse that seemed to disrupt the child’s certainty, but rather the lack of gender-identified clothing and/or colors.

The code of ‘Social Constructs’ was the most frequently used justification for students in this study. We believe that this is the most powerful factor in reasoning for the students, regardless of the character type. This reaffirms our stance referred throughout, that students’ prior knowledge and home lives have a deep and lasting impact on understandings of gender and performance, which are then used as justifications when texts are ambiguous, or characters perform against the supposed binary. With the students not differentiating their responses regardless of character type, this provides for a wide range of implications that can influence instruction and read alouds.

The Reliance on Gender as a Meaning Making Tool

Read alouds can be a tool to rethink bias and social norms that students may enter school with. This study showed that through this literacy activity, young children felt comfortable discussing their own perspective on gender, by referring to previously held understandings of constructions of identity and performance learned outside of the school space. During a small group read aloud of The Worst Princess (Kemp 2012), one of the participants recalled previous information by stating, “Because most prince, a prince means it’s a boy.” Almost immediately after, another student replied, “If it’s princess, that means it’s a girl.” We had not discussed with the students the labels of prince and princess during previous read aloud sessions, therefore the students used these literary elements to build their gendered knowledge about the characters.

By engaging in talk surrounding a topic through a piece of literature, students are given the opportunity to question previously held assumptions and hear the perspectives of peers who may hold different views of the world. Engaging in talk surrounding literature is one of the most effective ways for students to approach topics of gender, performance, race, and class (Brooks and Browne 2012). Through the guidance of a trusted adult or peer, students can be given the opportunity to talk through various contexts. Returning to The Worst Princess (Kemp 2012), one student offered that the dragon could not be female because girl dragons do not breathe smoke. This notion is rooted in the social construct that females are more delicate and could not possibly participate in such a brutish activity. However, before the author could respond, another student chimed in that, “girl dragons can breathe fire, too.” Through the event of the read aloud, a student presented a gendered notion of performance while another refuted that point, opening opportunities to question these assumptions.

This process not only allows students to be exposed to new perspectives, but it is also an opportunity for students to question their own understandings. Through the act of the read aloud, with careful questioning, students can begin to uncover where those understandings have originated from. While listening to a story about Biff the dog and his desire to do ballet (Kemp 2010), many students compared the characters as they were portrayed in the illustrations, to their own pets, or other animals they have come into contact with. Making these connections to their personal lives, shows that a student’s understanding of gender and performance can be related to their experiences and how they came to these perspectives. For many children, these connections are crafted in the home during the developmental years as they have ample exposure to family beliefs and norms. Children can then begin to identify these points as being unique to their family and themselves, while learning from peers and adults that not everyone may hold the same set of values. Read alouds provide for a safe space through which to engage these differences without fear of criticism or punishment due to differing points of view.

Another outcome from this study was the impossibility of avoiding gender when young children are engaged in read alouds of picture books; specifically, how students assign and assume gendered identities even on characters who could be assumed to be agendered such as animals or anthropomorphized objects. While the goal of the study was to determine and include student voice and perspectives pertaining to gender of characters in picture books, what was not anticipated was how the students assigned these same understandings when the conversations were directed elsewhere. During observed play time prior to the start of and throughout the data collection process, students began talking about certain toys, such as trucks and blocks having a gender, as well as art supplies and other classroom materials. In a first pass at understanding these instances, student responses were credited as being an extension of the read aloud activities in which students had just participated. However, when the researchers returned to the classroom for a culminating activity months after the conclusion of the data collection, these behaviors still existed during structured, and unstructured play times. The concepts of gender and identity remained with the students, when the activity they were engaged in was not specifically attempting to understand, or engage in this topic

Discussion and Implications

As the findings indicate, discussions of gender are necessary aspects of early childhood education, as students view characters in texts as similar regardless of the portrayal as being human, or a non-human character. Children come to school spaces already deeply aware of these social norms around gender. Even in progressive spaces, where children might be exposed to and speak more openly of gender diversity, the pervasive social narratives of the supposed binary still exist. In general, educators will be unable to avoid discussions of gender that occur in the classroom and instructional spaces. As found through this study, gender is something that exists for students that is not constrained to understandings of human existence. Early childhood learners believe animals, anthropomorphized objects, and everyday items have a gender than can be identified by specific features and ways of being. In children’s literature, even if the characters are ungendered or ambiguous, students still tend to ascribe human characteristics. It is the belief of the authors that this was done to create an understanding of a text, through the lived experience of the individual in a familiar way, through classifying individuals by their characteristics. What these characteristics say about an identity, is what the larger project from which this analysis stemmed and attempted to uncover.

Conversely, books in which ambiguously gendered animals or other objects are central characters can be utilized to get at these deeper meanings of gender and performance. Educators who are interested in uncovering student perspectives and understanding of previously held notions of gender, can implement these texts with ambiguous characters, in classroom instruction. This is in part because in these portrayals, the justification for claims must be made clearer than when a gendered character is presented. When students make claims, the evidence they provide can lead to deeper insights on the messages that society, school, and home lives provide to the children. In a study conducted on student reading experiences with A Monster Calls (Ness 2011), Aggleton (2017) found that when students had illustrations connected to the text, they considered the story in greater depth than those who had text only. Similarly, in read alouds centered on very specific topics, such as gender, students will have the opportunity to respond in greater detail when picture books are utilized over text only stories.

While we used one very specific literacy act, researcher guided read alouds, these discussions can be used in less formal ways to not only discuss gender and performance, but also other social issues that educators believe are important to question and problematize. Students are willing to identify and relate to social issues in texts, especially in picture books for early childhood students. By allowing students the opportunity to talk about these and other representations in real and meaningful ways, they will become more comfortable identifying their own perspectives and acknowledge how they can be used to shape understandings of larger social issues. Current educational policy in American schools is attempting to limit the rights of those students who identify outside of a supposed binary that is established and maintained by specific, and narrow, understandings of gender and performance. Allowing students to read and discuss a variety of topics will create a sense of understanding from which to draw upon to enact change for those in need of these positive representations.

We believe that these findings also demonstrate the importance of educators creating a space for these types of discussion and reflection. One suggestion would be an increased representation in the texts that are utilized in both formal literacy instruction, as well as available for less structured, free reading time. Students should not only see themselves represented in the text, but also the chance to interact with texts and characters from a wide variety of backgrounds and perspectives. By being exposed to these stories, students will have a wider understanding of gender and performance and will be better able to question and problematize static, binary representations that pervade social discourse. Additionally, we believe it is for the benefit of the students for educators to listen carefully to the discussions and conversations that are already occurring in school-based settings. In doing so, the educator is better prepared to address any issues of misrepresentation that may be occurring, as well as to establish a base from which to begin these topics when the time arises. Students come to school spaces with ideas and conceptions about gender which can act as a natural starting point for any discussion that may need to occur. Being aware of these already held understandings will naturally aid in furthering the conversation.

Further Research

Listening to and understanding how kindergarteners identify and justify gender in both human and non-human characters provides an understanding of how larger societal influences play a role in student understanding. We will move forward with replicating these read alouds in older grades, second and fourth, to determine if similarities or differences may exist as the students age chronologically as well as academically. In addition, there were a number of instances when students identified a character as having a gender but by the end of the read aloud, had changed their assignment. Further analysis into how and why these assignments changed will be occurring with this and other data collected across grade levels. Lastly, the results of this analysis and the larger study from which it was based, has led to a line of inquiry questioning how students would take up issues of gender identity and performance in these texts, if they were not explicitly framed as points of interest, as expressed in this study. As we move away from a binary construct of gender, we as researchers and educators must begin to question not only how students come to identify gender and performance, but the subtle nuances that can lead to a greater understanding of acceptance and care.

Conclusion

This study looked at young children’s talk about gender during read aloud sessions, where the texts specifically did not identify characters as having a gender or disrupted the social binary of male/female that many children enter school spaces understanding. Regardless of whether the characters were human or non-human, students relied heavily on social constructions of what gender is, or should be, based upon familiar markers of color, physical features, and the actions the characters engage in. The act of the read aloud event can provide an opportunity for students and teachers to engage in conversations that challenge and disrupt these previously held understandings. But the concept of gender cannot be fully avoided as it is a reliable marker of identification for young children to make meaning within a text. More importantly, this paper uncovered the lack of representation of various gendered, or ungendered identities in high-quality children’s books.

Often times, when identities that fall outside of the gendered markers of the supposed binary are present, the story that is being told focuses on the identity itself as the crux of the narrative. The character is then forced to acknowledge their identity and make attempts to come to terms with it or seek acceptance from others. This study shows that a larger set of texts need to be made available so that children can not only see themselves in the texts, but also interact with stories of other students, with whom they may share features of identity not considered before. Movements such as #WeNeedDiverseBooks calls for greater representation in children and young adult literature and provide an entry point for educators into ways of accessing these materials. Educators can use forums and information sharing entities such as these to meaningfully introduce these perspectives in classroom settings. Students are aware of multiple identities and are already engaging in these conversations. Educators can use texts similar to those utilized in this study to gain a deeper understanding of where students’ perceptions of gender and identity originate. By understanding how children identify others, a space can be created for a wider acceptance of all individuals and further the conversations that begin before students enter the classroom. Due to the nature of students using similar identifiers across character types, we can better understand student reasoning without the need to determine if the portrayal is influencing their decisions.

Notes

All names in this article are pseudonyms.

Books were determined to have ‘ambiguous’ characters when the character was not directly identified with names, pronouns, or other specific information. For example, in the text Owl Moon (Yolen 1987), the character acts as the narrator for the story and refers to themselves in the first person. The character is not given a gender in the text as pronouns such as he/she are absent. We cite this as an example of an ambiguous character as the gender of the character is not important directly referenced within the plot of the story.

References

Aggleton, J. (2017). “What is the use of a book without pictures?” An exploration of the impact of illustrations on reading experience in a monster calls. Children’s Literature in Education,48(3), 230–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-016-9279-1.

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives,6(3), 9–11.

Blaise, M. (2012). Playing it straight: Uncovering gender discourse in the early childhood classroom. London: Routledge.

Brooks, W., & Browne, S. (2012). Towards a culturally situated reader response theory. Children’s Literature in Education,43(1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-011-9154-z.

Corey, S., & Karlovitz, K. (2000). You forgot your skirt Amelia Bloomer a very improper story. New York: Scholastic Press.

Crisp, T., & Hiller, B. (2011). “Is this a boy or a girl?”: Rethinking sex-role representation in Caldecott Medal-winning picturebooks, 1938–2011. Children’s Literature in Education,42(3), 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-011-9128-1.

DePaola, T. (1979). Oliver Button is a sissy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Drake, J. A., Price, J. H., Telljohann, S. K., & Funk, J. B. (2003). Teacher perceptions and practices regarding school bullying prevention. Journal of School Health,63, 347–355.

Dutro, E. (2016). “But that’s a girls’ book” Exploring gender boundaries in children’s reading practices. The Reading Teacher,55(4), 376–384.

Francis, B., & Paechter, C. (2015). The problem of gender categorisation: Addressing dilemmas past and present in gender and education research. Gender and Education,27(7), 776–790.

Hoffman, J. L. (2011). Coconstructing meaning: Interactive literary discussions in kindergarten read-alouds. The Reading Teacher,65(3), 183–194.

Jacobs, K. B. & Hill, T. (in press). Using picture books to promote young children's understanding of gender diversity and gender equity. In A. Murrell & J. Petrie (Eds.), Diversity Across Disciplines: Research on People, Policy, Process, and Paradigm. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Kemp, A. (2010). Dogs don’t do ballet. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Kemp, A. (2012). The worst princess. New York: Random House.

Kiernan-Johnson, E. (2012). Roland Humphrey is wearing a what. Boulder: Huntley Rahara Press.

Kilodavis, C. (2011). My princess boy. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Mattix, A., & Sobolak, M. J. (2014). Focus on elementary: The gender journey in picturebooks: A look back to move forward. Childhood Education,90(3), 229–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2014.912061.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

Ness, P. (2011). A monster calls. Somerville: Candlewick.

Oakhill, J., & Cain, K. (2007). Introduction to comprehension development. In K. Cain & J. Oakhill (Eds.), Challenges in language and literacy: Children’s comprehension problems in oral and written language: A cognitive perspective (pp. 3–34). New York: The Guilford Press. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/thill116/Downloads/Challenges_in_Language_and_Literacy_Children_s_Comprehension_Problems_in_Oral_and_Written_Language_A_Cognitive_Perspective (2).pdf

Rohmann, E. (2002). My friend rabbit. London: MacMillan.

Ryan, C. L., Patraw, J. M., & Bednar, M. (2013). Discussing princess boys and pregnant men: Teaching about gender diversity and transgender experiences within an elementary school curriculum. Journal of LGBT Youth,10, 83–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2012.718540.

Sadker, D., Sadker, M., & Zittleman, K. (2009). Still failing at fairness: How gender bias cheats girls and boys in school and what we can do about it (2nd ed.). New York: Scribner.

Saldana, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

Sipe, L. R. (2002). Talking back and taking over: Young children’s expressive engagement during storybook read-alouds. Reading Teacher,55(5), 476–483.

Sipe, L. R. (2008). Storytime: Young children’s literary understanding in the classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

Sipe, L. R., & Brightman, A. E. (2009). Young children’s interpretations of page breaks in contemporary picture storybooks. Journal of Literacy Research,41, 68–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/10862960802695214.

Smulders, S. (2015). Dresses make the girl: Gender and identity from the hundred dresses to 10,000 dresses. Children’s Literature in Education,46(4), 410–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-015-9242-6.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1997). Grounded theory in practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Swanson, S. M. (2008). The house in the night. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Yolen, J. (1987). Owl moon. London: Penguin.

Zolotow, C. (1972). William’s doll. New York: Harper and Row.

Children’s Literature Cited

Corey, S., & Karlovitz, K. (2000). You forgot your skirt, Amelia Bloomer a very improper story. New York: Scholastic Press.

DePaola, T. (1979). Oliver button is a sissy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Kemp, A. (2010). Dogs don’t do ballet. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Kemp, A. (2012). The worst princess. New York: Random House.

Kiernan-Johnson, E. (2012). Roland Humphrey is wearing a what. Boulder: Huntley Rahara Press.

Kilodavis, C. (2011). My princess boy. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Ness, P. (2011). A monster calls. Somerville: Candlewick.

Rohmann, E. (2002). My friend rabbit. London: MacMillan.

Swanson, S. M. (2008). The house in the night. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Yolen, J. (1987). Owl moon. London: Penguin.

Zolotow, C. (1972). William’s doll. New York: Harper and Row.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hill, T.M., Bartow Jacobs, K. “The Mouse Looks Like a Boy”: Young Children’s Talk About Gender Across Human and Nonhuman Characters in Picture Books. Early Childhood Educ J 48, 93–102 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00969-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00969-x