Abstract

Endemic marine species often exist as metapopulations distributed across several discrete locations, such that their extinction risk is dependent upon population dynamics and persistence at each location. The anemonefish Amphiprion latezonatus is a habitat specialist, endemic to two oceanic islands (Lord Howe and Norfolk) and the adjacent eastern Australian coast from the Sunshine Coast to Southwest Rocks. To determine how extinction risk varies across the limited number of locations where A. latezonatus occurs, we quantified ecological, biological, and behavioural characteristics at six locations and four reef zones. The abundance of A. latezonatus and its host anemones varied considerably throughout its range, with A. latezonatus abundance being very low at Sunshine Coast and Elizabeth Reef, low at Lord Howe Island and Norfolk Island, and moderate at North Solitary Island. This species was not detected at Middleton Reef, despite local abundance of their host anemones. Abundance of A. latezonatus was generally correlated with depth and host anemone abundance, from which we infer that extirpation risk is directly proportional to their host anemone population’s size. Consistent with this, A. latezonatus social group size was positively correlated with the number of anemones inhabited. A. latezonatus may be impacted by interactions and competition with other anemonefish species in shallow (< 10 m) waters, but competition has little effect in deeper water where population abundances are highest. Significant differences in population characteristics demonstrate a need for location-specific conservation strategies and identify the Sunshine Coast population as most vulnerable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endemic species are inherently vulnerable to extinction, though extinction risk may be further compounded by other ecological, biological, and behavioural traits (Lawton 1993; Gaston 1998; Frankham 1998; Dowding and Murphy 2001; Munday 2004). Due to the discontinuities of benthic habitats in many marine systems, many endemic marine species exist as isolated metapopulations (Kritzer and Sale 2004), such that species persistence depends on the viability of each discrete population (Wiens 1989). For example, coral reefs species occur on discrete reef patches separated by deep oceans. Despite the propensity for marine species to form metapopulations, the majority of research on metapopulation persistence and variability of traits among populations has focused on terrestrial ecosystems (Hanski et al. 1997). The need to understand trait variability and persistence in populations of marine species is particularly pertinent given escalating human impacts.

Marine ecosystems are increasingly threatened by environmental change, diseases, overharvesting, and invasive species (Goldberg and Wilkinson 2004). On coral reefs, rising sea temperatures have caused bleaching events resulting in mass mortality of corals and anemones (Wilkinson 1998; Hoegh-Guldberg 1999; Hattori 2002; Hobbs et al. 2013; Hughes et al. 2017). The subsequent habitat loss has had negative flow-on effects, particularly for ecological specialists (Pratchett et al. 2008). Among the most specialised of reef fishes are anemonefishes, which have an obligate association with specific host anemones (Jones et al. 2002; Pratchett et al. 2016). The close relationship between anemones and anemonefishes means that characteristics (e.g., size, number, quality) of anemones influence the size and replenishment of anemonefish populations (Hattori 2002; Saenz-Agudelo et al. 2011; Hobbs et al. 2013; Frisch et al. 2019). Local extinction of anemonefishes has also occurred following mass bleaching of host anemones (Hattori 2002). Overharvesting of anemonefishes and their host anemones also threatens population persistence (Shuman et al. 2005; Frisch et al. 2016, 2019).

Habitat patches within a species range are often environmentally heterogeneous, leading to differences in abundance, distribution, and resource use across locations. On coral reefs, for example, the abundance and habitat use of fishes varies with reef structure, habitat size and quality (Noonan et al. 2012; Nadler et al. 2013), competition with congenerics (Ormond et al. 1996; Robertson 1996; Bonin et al. 2015), and microhabitat selectivity (Fulton et al. 2016; Pratchett et al. 2016). Due to this variability, a thorough assessment of vulnerability in marine species requires understanding how traits vary across the entire geographic range, rather than assuming a single population represents the whole.

The Lord Howe Island – Norfolk Island region (29.04–31.55°S) in the south-west Pacific Ocean is a hotspot for endemic coral reef species, where many endemics are distributed across four isolated reefs and islands (Randall 1976, 1998; van der Meer et al. 2013, 2014; Steinberg et al. 2016). Some endemics also occur on the adjacent Australian mainland coast to the west of the hotspot. This is one of the most rapidly warming ocean regions due to climate change effects on the East Australian Current (Ridgway 2007; Hobday and Pecl 2013; Robinson et al. 2015) and has already caused at least three bleaching events at Lord Howe Island which affected corals and anemones (Harrison et al. 2011; Moriarty et al. 2019).

The purpose of this study was to determine spatial variation in ecological, biological, and behavioural traits for the wideband anemonefish, Amphiprion latezonatus. This was achieved by surveying at two spatial scales (reef zone and location) at six discreet locations across its geographic range. Existing knowledge of the biology and ecology of this study species comes from research conducted at one location on mainland Australia – North Solitary Island (Richardson 1999; Scott et al. 2011). Little is known about the other populations at oceanic locations, where environmental conditions differ considerably to those experienced by mainland populations. The specific aims of this study were to determine variability among locations and across reef zones within locations in: 1) host anemone abundance and reef zone distribution; 2) A. latezonatus abundance and reef zone distribution; 3) A. latezonatus social group size and composition; 4) A. latezonatus host anemone species use and occupancy rates; and 5), life history of A. latezonatus (age and pelagic larval duration). Insufficient samples limited inferences for the fifth aim.

Methods

Study species

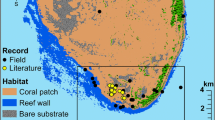

Amphiprion latezonatus occurs on rocky and coral reefs at oceanic locations (Lord Howe and Norfolk Islands) and along the subtropical east Australian coast from the Sunshine Coast to South West Rocks (Fautin and Allen 1997; Fig. 1). Along the east Australian coast, populations of A. latezonatus are extremely small, except at North Solitary Island (Richardson 1996). A. latezonatus is a habitat specialist, originally reported to inhabit only one species of anemone, Heteractis crispa (Fautin and Allen 1997; Santini and Polacco 2006). Along the Australian coastline A. latezonatus also inhabits the anemone Entacmaea quadricolor and was once recorded occupying Stichodactyla gigantea (Richardson 1999; Scott et al. 2011, 2016; Malcolm and Scott 2017).

Study species and sampling locations. a) A social group of Amphiprion latezonatus (two adults and one juvenile) in Entacmaea quadricolor at Lord Howe Island, photograph by Tane Sinclair-Taylor. b) Google Earth image of Eastern Australia and Tasman Sea showing Amphiprion latezonatus inhabited locations and study sites: Sunshine Coast (26.6500°S, 153.0667°E), North Solitary Island (29.9294°S, 153.3915°E), Middleton Reef (29.4722°S, 159.1194°E), Elizabeth Reef (29.9417°S, 159.0625°E), Lord Howe Island (31.5553°S, 159.0821°E), and Norfolk Island (29.0408°S, 167.9547°E). All sites were surveyed except North Solitary Island, where data from Scott et al. (2011), and Richardson (1996, 1999) were used

Survey design

To build on previous research undertaken at North Solitary Island, this study surveyed all three other locations known to sustain populations of A. latezonatus – Norfolk Island, Lord Howe Island, and Sunshine Coast. Two adjacent oceanic locations (Middleton Reef and Elizabeth Reef) where A. latezonatus populations have not been recorded were also surveyed because many other Lord Howe Island-Norfolk Island endemics occur at these remote reefs, as do the host anemones H. crispa and E. quadricolor (van der Meer et al. 2012, 2013, 2014). To determine variation in the distribution and abundance of A. latezonatus and its host anemones, underwater visual surveys (belt transects and timed swims) were undertaken in four distinct reef zones at all five surveyed locations: lagoon (1–3 m), outer reef crest (~5 m), outer reef slope (~15 m), and deep outer reef (~30 m). By swimming at constant speed, surveying a constant width (5 m) and recording survey duration (mins), timed swims were converted to reef area. Timed swims were used instead of belt transects in the deep outer reef to increase survey efficiency given time constraints associated with deep diving. Variability in survey area was due to differences in dive duration. Sites were randomly selected. Details of survey methods are provided in Supplement 1 and Table 1. All abundance data were standardized to abundance per 250 m−2.

Host anemone species were identified using the description by Fautin and Allen (1997). Host anemone species inhabited and occupancy rate (whether the anemone was inhabited) were recorded for every host anemone encountered in surveys. To determine social group size and composition, the size and number of A. latezonatus in each social group and the number of anemones inhabited were recorded. A social group was defined as the number of anemonefish per anemone or cluster of anemones within 1 m of each other. A. latezonatus individuals were categorised into three size classes: adult size >50 mm total length (TL), juveniles 25–50 mm TL, and new recruits <25 mm TL. Total length of each fish was either visually estimated to the nearest 5 mm or measured underwater after capture using a hand net.

Life history

All adult pairs found in anemone clusters were assumed to be breeding pairs, and surfaces within 1 m of the anemone were searched for egg clutches to determine breeding season. Egg clutches were expected during all surveys because A. latezonatus breed year-round at North Solitary Island, with a peak in the Austral summer (Richardson et al. 1997). To estimate age and pelagic larval duration (PLD), five adult individuals were captured and euthanized using a clove oil anaesthetic solution. Age was estimated by removing and transversely sectioning sagittal otoliths (ear bones) following Wilson and McCormick 1999, using the equipment and approach outlined in Hobbs et al. 2014. Increments at the otolith core were assumed to represent daily rings up to the settlement mark, which is characterized by an abrupt decrease in increment width (Wilson and McCormick 1999). Broad bands after the settlement event were assumed to be annual rings. For both PLD and age, otolith rings were counted on three different days, by the same reader. There were no differences between otoliths counts of any sampled individuals.

Statistical analyses

Distribution and abundance

All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.6.1 (R Core Team 2016). Differences in abundances of both A. latezonatus and host anemones between reef zones (deep outer reef, outer reef slope, reef crest, and lagoon) both within and between all five study locations, were examined using a Scheirer-Ray-Hare test as data were non-normal. Pairwise comparisons were examined using the Welch two sample t-test (two tailed), as it allows for unequal sample sizes. Though the t-test assumes unequal variance and normal distribution, it is still robust for skewed distributions and recommended above non-parametric tests for large datasets (Fagerland 2012). α-values were Bonferroni corrected to account for multiple comparisons. The relationship between the abundance of A. latezonatus and its host anemones was examined at Norfolk Island using a linear model that incorporated reef zone, because this was the only site where A. latezonatus inhabited multiple reef zones. Due to a lack of individuals in shallow water at Lord Howe Island, reef zone was not included in the analysis at this location.

Host use and social group size

The relationship between number of anemones inhabited and social group size was examined using a linear model with location initially included as an interaction. Any interactions that were not significant were subsequently removed from final analyses.

Results

Distribution and abundance of host anemones

A total of 3858 potential host anemones (E. quadricolor and H. crispa) were recorded in surveys across all reef zones and locations. Mean host anemone abundance differed significantly between locations and reef zones (Sheirer-Ray-Hare, p < 0.05, Table 2). Across locations, abundance was highest at Lord Howe Island (23.56 ± 7.9 SE 250 m−2) and Norfolk Island (15.5 ± 3.4 SE 250 m−2) and 19- to 76-fold lower at remaining locations: Elizabeth Reef (0.81 ± 0.63 SE 250 m−2), Middleton Reef (0.7 ± 0.3 SE 250 m−2) and Sunshine Coast (0.31 ± 0.17 SE 250 m−2) (Table S1, Fig. 2a).

Mean abundance (± SE 250 m−2) of anemone and Amphiprion latezonatus at each sampled location. a) Host anemones at all sampled locations - Norfolk Island (NI), Lord Howe Island (LHI), Sunshine Coast (SC), Elizabeth Reef (ER), and Middleton Reef (MR). North Solitary Island (NSI) data (from Scott et al. 2011 and Richardson 1996) provided as insets for comparative purposes (since mean anemonefish densities at NSI are an order of magnitude greater than at the other study sites). Statistical comparisons with North Solitary Island were not performed because raw data was not available for all samples. b) A. latezonatus at all sampled locations and North Solitary Island (inset). Locations with the same letter group are not significantly different. For p values, see Tables S1 and S5

At Norfolk Island, 942 host anemones (E. quadricolor only) were recorded in surveys. Anemone abundance differed significantly between reef zones and was highest in the lagoon (47.83 ± 3.79 SE 250 m−2) and lowest at the outer reef crest (1.46 ± 0.65 SE 250 m−2) (Table S2, Fig. 3a). Outside of surveys, one individual of another host anemone, Stichodactyla haddoni, was recorded, however it was not inhabited by any anemonefish.

Mean abundance (± SE 250 m−2) of host anemone and Amphiprion latezonatus in each reef zone. Note the scale difference of 1–2 orders of magnitude in mean densities of anemones and anemonefish. Reef zones are denoted as follows: Deep outer reef (deep), outer reef slope (slope), outer reef crest (crest), and lagoon. a) host anemones in different reef zones at Norfolk Island. b) A. latezonatus in different reef zones at Norfolk Island. c) host anemones in different reef zones at Lord Howe Island. d) A. latezonatus in different reef zones at Lord Howe Island. e) host anemones in each reef zone at Norfolk (NI) and Lord Howe (LHI) Islands. f) A. latezonatus in each reef zone at Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands. In a) through d), groups with the same letter group are not significantly different. In e) and f), significant differences between habitats are illustrated with horizontal bars, values are denoted as * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.005, and *** for p < 0.0005

At Lord Howe Island, 2776 host anemones were recorded in surveys (Fig. 2a) and included two species: E. quadricolor (90.2% of all surveyed anemones) and H. crispa, with A. latezonatus inhabiting both species. Anemone abundance differed considerably across reef zones and was highest in the lagoon (101.48 ± 30.39 SE 250 m−2), and lowest at the outer reef crest (0.05 ± 0.03 SE 250 m−2) (Table S3, Fig. 3c).

When comparing within reef zones between locations, anemone abundances were significantly greater at Norfolk than Lord Howe Island at the deep outer reef and outer reef slope, but were not significantly different at the outer reef crest and lagoon (Table S4, Fig. 3e).

At Elizabeth Reef and Middleton Reef, 48 and 62 host anemones (E. quadricolor only) were recorded, respectively (Fig. 2a). Despite surveying all reef zones, anemones were only recorded in the lagoon. Outside of surveys, one H. crispa was observed on the outer reef slope at Elizabeth Reef and was inhabited by one pair of A. latezonatus. At Sunshine Coast only one reef zone (deep outer reef) was present and 30 host anemones (all E. quadricolor) were recorded.

A. latezonatus distribution and abundance

A total of 355 A. latezonatus individuals were recorded during surveys. The mean abundance of A. latezonatus differed significantly between locations and reef zones (Sheirer-Ray-Hare, p < 0.05, Table 2). Across locations, abundance was highest at Norfolk Island (4.83 ± 1.07 SE 250 m−2) and Lord Howe Island (0.26 ± 0.06 SE 250 m−2) and lowest at Elizabeth Reef, Middleton Reef, and Sunshine Coast (0250 m−2) (Table S5, Fig. 2b).

At Norfolk Island, 314 A. latezonatus individuals were recorded in surveys. The abundance of A. latezonatus was considerably higher on the deep outer reef (5 ± 1.02 SE 250 m−2) and outer reef slope (4.86 ± 0.83 SE 250 m−2), compared to the lagoon (0250 m−2) and outer reef crest (0.25 ± 0.18 SE 250 m−2; Table S6, Fig. 3b). No other anemonefish species were recorded.

At Lord Howe Island, all 41 A. latezonatus recorded in transects were on the deep outer reef (15–30 m), where the mean abundance was 0.32 (± 0.09 SE) individuals per 250 m−2 (Table S7, Fig. 3d). Another anemonefish species, A. mccullochi, was abundant at Lord Howe Island, particularly in shallow waters (< 15 m).

Comparing within reef zones between locations, A. latezonatus abundance was significantly greater at Norfolk than Lord Howe Island at the deep outer reef and outer reef slope, but was not significantly different at the outer reef crest or lagoon (Fig. 3f, Table S8).

At the Sunshine Coast, Elizabeth Reef, and Middleton Reef, A. latezonatus were not recorded in surveys (Fig. 2b). However, two and four adults were found outside transects at Elizabeth Reef and Sunshine Coast, respectively. Two other anemonefishes (A. melanopus and A. akindynos) were present at Sunshine Coast, whilst A. mccullochi was found at Elizabeth and Middleton Reefs.

Social group size and composition

Social group size was similar at Norfolk (N = 161 groups, mean = 1.94 ± 0.06 SE, range 1 to 6 individuals) and Lord Howe Islands (N = 18 groups, mean = 2.28 ± 0.25 SE, range = 1 to 4 individuals) and across reef zones (Sheirer-Ray-Hare, p > 0.05, Table 2). 53.6% of all social groups consisted of two adults (96 of 179, Fig. 4). The number of anemones inhabited by social groups between locations or between reef zones were not significantly different (Sheirer-Ray-Hare, p > 0.05, Table 2).

Histogram of Amphiprion latezonatus social group composition. Size class is denoted as follows: a – adult, j – juvenile, nr – new recruit. Adult A. latezonatus were defined as having total length greater than 50 mm, juveniles as having total length between 25 and 50 mm, and new recruits as having total length less than 25 mm

Of the 355 A. latezonatus encountered in surveys at Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands, eight (2.25%) were classified as new recruits (< 25 mm TL), 104 (29.3%) as juveniles (25–50 mm TL), and 243 (68.45%) as adults (>50 mm TL). The new recruits:juveniles:adults ratio was 6:88:220 at Norfolk Island and 2:16:23 at Lord Howe Island. At Sunshine Coast and Elizabeth Reef, the social groups observed outside of surveys each contained two adults (N = 3 groups).

Host use

Two species of host anemone were recorded at Lord Howe Island, with 13 A. latezonatus social groups occupying E. quadricolor, two social groups occupying H. crispa, and three social groups using both host anemone species when the anemones were side by side. Adults and juveniles inhabited both E. quadricolor and H. crispa, with 17 adults and nine juveniles inhabiting only E. quadricolor, two adults and three juveniles inhabiting only H. crispa, and four adults and four juveniles inhabiting mixed species microhabitat. All new recruits inhabited only E. quadricolor. Notably, seven of the 18 A. latezonatus groups cohabitated with A. mccullochi, five of which only contained one juvenile A. mccullochi, whilst the remaining two groups contained a single adult-sized A. mccullochi. Five cohabiting groups were on E. quadricolor and two cohabiting groups were on the mixed E. quadricolor-H. crispa microhabitat.

At Norfolk Island, all surveyed A. latezonatus inhabited E. quadricolor. At Sunshine Coast, E. quadricolor was the only anemone recorded in surveys and these were mainly occupied by A. akindynos (28 individuals) and rarely by A. melanopus (2 individuals). Outside of the transects, A. latezonatus occupied E. quadricolor, with two adults in one anemone at 18 m depth, and two adults in three anemones at 20 m depth. At Elizabeth and Middleton Reefs, all anemones were recorded in the lagoon and were inhabited by A. mccullochi, despite surveying across reef zones. No A. latezonatus were recorded in surveys, but outside of transects, one adult A. latezonatus pair occupied a single H. crispa at 12 m depth on the outer reef slope at Elizabeth Reef.

A. latezonatus abundance was positively correlated with host anemone abundance across locations (R2 = 0.96, p < 0.001, n = 18, Table 3) and reef zones (R2 = 0.84, p < 0.001, n = 38, Table 4). Overall social group size was also positively correlated with the number of anemones inhabited by each social group (R2 = 0.21, p < 0.001, n = 181, Fig. 5).

Correlation between number of Amphiprion latezonatus in a social group and number of anemones inhabited by that group. Number of A. latezonatus per social group increased significantly with number of anemones in an inhabited cluster. Mean number of A. latezonatus per social group is indicated by the red diamond, the height of each shape represents the interquartile range, and the width of each shape indicates the probability abundance of the data points

Despite the positive relationship between host anemone abundance and A. latezonatus abundance across locations and reef zones, no A. latezonatus were recorded in the lagoons at either Norfolk or Lord Howe Islands, where host anemone abundances were highest (Fig. 3a–e). The relationship between host anemone abundance and A. latezonatus abundance was also different between reef zones at Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands (Table 4), where the increase in A. latezonatus abundance with increasing anemone abundance was much greater at deep outer reefs compared to outer reef crests and slopes.

Biological traits

The smallest new recruit observed in surveys measured 15 mm TL and the largest adult measured 165 mm TL. Examination of sectioned sagittal otoliths revealed that pelagic larval duration varied between 14 and 17 days, with a mean of 15.2 days (n = 5). Age estimates from otoliths of five adults were 6 (95 mm TL), 8 (109 mm TL), 9 (113 mm TL), 11 (110 mm TL), and 13 years (125 mm TL). No egg clutches were recorded at Norfolk Island in March or at Lord Howe Island in April, but in November egg clutches were observed at 2 of 18 Lord Howe Island social groups. In one social group (two adults and two juveniles occupying two H. crispa), the breeding pair consisted of a 93 mm TL male and a 100 mm TL female. The second group occupied two E. quadricolor and comprised a breeding pair – a 147 TL male and a 165 mm TL female.

Discussion

Host anemone distribution and abundance

The distribution and abundance of host anemone species (E. quadricolor and H. crispa) varies greatly between locations and reef zones, representing varying constraints on habitat availability for A. latezonatus. Host anemone abundance (both species combined) was greatest at North Solitary Island and Norfolk Island and lowest at Elizabeth Reef, Middleton Reef, and Sunshine Coast (Scott et al. 2011; this study). Across the A. latezonatus range, E. quadricolor was much more abundant than H. crispa (Scott et al. 2011; this study). Throughout the A. latezonatus range, host anemone abundance was greatest in shallow waters.

A. latezonatus distribution and abundance

Amphiprion latezonatus occurred at low to moderate abundances at North Solitary, Norfolk, and Lord Howe Islands, while abundances at the Sunshine Coast and along the Australian coastline (except North Solitary Island) were extremely low (Richardson 1996; this study), increasing their risk of extirpation. Additionally, the presence of one A. latezonatus pair at Elizabeth Reef, and of host anemones at Middleton Reef, indicate that A. latezonatus could potentially establish populations at these locations in the future. Genetic studies reveal that A. latezonatus populations (Steinberg et al. 2016) and populations of other fishes endemic to the Lord Howe Island-Norfolk Island region (van der Meer et al. 2012, 2013, 2014) are genetically isolated and contribute little to other populations in contemporary time frames. Thus, recolonization or population recovery following disturbances, or colonization of new reefs, will likely take considerable time.

Across all locations, A. latezonatus abundance increases with depth. Although some individuals were observed at 5 m depth, A. latezonatus is rare or absent in water less than 10 m deep across its range (Richardson 1996, 1999; Scott et al. 2011). This is interesting because our surveys revealed that host anemones are most abundant in shallow (< 5 m) lagoons at most locations. These shallow water anemones are occupied by other anemonefishes (A. mccullochi, A. akindynos, A. melanopus) that may outcompete A. latezonatus.

The abundance of many anemonefish species is positively correlated with their host anemone abundances (Fautin 1992; Richardson 1999; Elliott and Mariscal 2001; Mitchell and Dill 2005; Jones et al. 2008; Scott et al. 2011; Frisch et al. 2016; Howell et al. 2016). Indeed, monitoring studies reveal anemonefish abundance tracks changes in host anemone abundance (Shuman et al. 2005; Scott et al. 2011; Frisch et al. 2016; Scott and Hoey 2017) and large declines in host anemone abundance result in local anemonefish extinctions (Hattori 2002; Thomas et al. 2015). For A. latezonatus, this positive relationship also holds and implies that abundance will be negatively affected by mass bleaching or other impacts that affect host anemone abundance.

A. latezonatus social group size and composition

The average social group size for A. latezonatus was two individuals (maximum = 6) and this may be a major factor limiting its abundance and total reproductive output. At North Solitary Island, social group size was smaller, with only one to three individuals per group (Richardson 1999; Scott et al. 2011). The relative abundance of different host anemone species varies across the A. latezonatus range and this will affect the number of breeding pairs because adult fish tend to prefer E. quadricolor over H. crispa (Richardson 1996; Scott et al. 2016). Therefore, conserving E. quadricolor as fish breeding habitat is important.

A. latezonatus host use

Hecteractis crispa was considered the primary host anemone used by A. latezonatus (Fautin and Allen 1997; Santini and Polacco 2006; Ollerton et al. 2007), but this study identified E. quadricolor as the primary host at Lord Howe Island, Norfolk Island, and Sunshine Coast. At North Solitary Island, A. latezonatus occupied both H. crispa and E. quadricolor (Richardson 1996, 1999; Scott et al. 2016). The use of multiple host species decreases extinction risk associated with specialisation. Several anemonefish species alter host use across their range due to competition (Camp et al. 2016) and A. latezonatus may compete with other anemonefishes (A. mccullochi, A. akindynos, A. melanopus). Thus, the observed anemone abundance differences and the presence of potential competitors across the A. latezonatus range could contribute to differences in its host use, distribution, and abundance.

Multiple host use can also affect social group size and reproduction (Fautin and Allen 1997). For A. latezonatus, breeding pairs occupied both host anemone species, whilst group size and social group composition appeared similar. At North Solitary Island, A. latezonatus formed breeding pairs only on E. quadricolor, with H. crispa supporting juveniles (Richardson 1996; Scott et al. 2016). While this suggests that juvenile A. latezonatus may prefer H. crispa hosts, in another anemonefish species that also occupies E. quadricolor and H. crispa, all sizes of anemonefish preferred E. quadricolor as their host, but only adults occupied E. quadricolor (Huebner et al. 2012). Ontogenetic changes in host use have been reported in other anemonefishes (Fautin and Allen 1997; Chadwick and Arvedlund 2005; Huebner et al. 2012; Howell et al. 2016). For A. latezonatus, the number of host anemone species supporting breeding pairs differs across its range, likely contributing to range-wide differences in maximum potential reproductive population sizes, which in turn will alter local extinction risk.

Conclusions

Ecological and behavioural traits that influence extirpation risk differed between locations and emphasise the need for range-wide studies. These traits can also act synergistically to increase extinction risk. Based on these vulnerable traits we conclude that A. latezonatus is most at risk of extirpation at Sunshine Coast, less so at Lord Howe Island, and least at Norfolk and North Solitary Islands. Given the positive relationship between population size and host abundance, and the increasing severity and frequency of bleaching events (Hughes et al. 2017) - conserving host anemones, especially in deep outer reefs where host anemone abundance is relatively low and A. latezonatus abundance is greatest - should be a management priority to prevent A. latezonatus extirpation or extinction.

Data availability

All data and code are publicly accessible at https://doi.org/10.17632/dskhn32fsw.3.

References

Bonin MC, Boström-Einarsson L, Munday PL, Jones GP (2015) The prevalence and importance of competition among coral reef fishes. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 46:169–190

Camp EF, Hobbs JPA, De Brauwer M et al (2016) Cohabitation promotes high diversity of clownfishes in the coral triangle. Proc R Soc B 283:20160277. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.0277

Chadwick NE, Arvedlund M (2005) Abundance of giant sea anemones and patterns of association with anemonefish in the northern Red Sea. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 85:1287–1292. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315405012440

Dowding JE, Murphy EC (2001) The impact of predation by introduced mammals on endemic shorebirds in New Zealand: a conservation perspective. Biol Conserv 99:47–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00187-7

Elliott JK, Mariscal RN (2001) Coexistence of nine anemonefish species: differential host and habitat utilization, size and recruitment. Mar Biol 138:23–36

Fagerland MW (2012) T-tests, non-parametric tests, and large studies—a paradox of statistical practice? BMC Med Res Methodol 12:–78

Fautin DG (1992) Anemonefish recruitment: the roles of order and chance. Symbiosis 14:143–160

Fautin DG, Allen GR (1997) Anemone fishes and their host sea anemones: a guide for aquarists and divers. Revised edition. West Aust museum, Perth 70

Frankham R (1998) Inbreeding and extinction: island populations. Conserv Biol 12:665–675. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1523-1739.1998.96456.X

Frisch AJ, Hobbs JPA, Hansen ST, Williamson DH, Bonin MC, Jones GP, Rizzari JR (2019) Recovery potential of mutualistic anemone and anemonefish populations. Fish Res 218:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2019.04.018

Frisch AJ, Rizzari JR, Munkres KP, Hobbs JPA (2016) Anemonefish depletion reduces survival, growth, reproduction and fishery productivity of mutualistic anemone-anemonefish colonies. Coral Reefs 35:375–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-016-1401-8

Fulton CJ, Noble MN, Radford B, Gallen C, Harasti D (2016) Microhabitat selectivity underpins regional indicators of fish abundance and replenishment. Ecol Indic 70:222–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.06.032

Gaston KJ (1998) Rarity as double jeopardy. Nature 394:229–230. https://doi.org/10.1038/28288

Goldberg J, Wilkinson C (2004) Global threats to coral reefs: coral bleaching, global climate change, disease, predator plagues, and invasive species. Status coral reefs world 2004 Vol I 67–92

Hanski I, Gilpin ME, McCauley DE (1997) Metapopulation biology: ecology, genetics, and evolution. Elsevier

Harrison PL, Dalton SJ, Carroll AG (2011) Extensive coral bleaching on the world’s southernmost coral reef at Lord Howe Island, Australia. Coral Reefs 30:775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-011-0778-7

Hattori A (2002) Small and large anemonefishes can coexist using the same patchy resources on a coral reef, before habitat destruction. J Anim Ecol 71:824–831

Hobbs JPA, Frisch AJ, Ford BM et al (2013) Taxonomic, spatial and temporal patterns of bleaching in anemones inhabited by anemonefishes. PLoS one 8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070966

Hobbs JPA, Frisch AJ, Mutz S, Ford BM (2014) Evaluating the effectiveness of teeth and dorsal fin spines for non-lethal age estimation of a tropical reef fish, coral trout Plectropomus leopardus. J Fish Biol 84:328–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.12287

Hobday AJ, Pecl GT (2013) Identification of global marine hotspots: sentinels for change and vanguards for adaptation action. Rev Fish Biol Fish 24:415–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-013-9326-6

Hoegh-Guldberg O (1999) Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Mar Freshw Res 50:839–866. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF99078

Howell J, Goulet TL, Goulet D (2016) Anemonefish musical chairs and the plight of the two-band anemonefish, Amphiprion bicinctus. Environ Biol Fish 99:873–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-016-0530-9

Huebner LK, Dailey B, Titus BM, Khalaf M, Chadwick NE (2012) Host preference and habitat segregation among Red Sea anemonefish: effects of sea anemone traits and fish life stages. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 464:1–15. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09964

Hughes TP, Kerry JT, Álvarez-Noriega M, Álvarez-Romero JG, Anderson KD, Baird AH, Babcock RC, Beger M, Bellwood DR, Berkelmans R, Bridge TC, Butler IR, Byrne M, Cantin NE, Comeau S, Connolly SR, Cumming GS, Dalton SJ, Diaz-Pulido G, Eakin CM, Figueira WF, Gilmour JP, Harrison HB, Heron SF, Hoey AS, Hobbs JPA, Hoogenboom MO, Kennedy EV, Kuo CY, Lough JM, Lowe RJ, Liu G, McCulloch MT, Malcolm HA, McWilliam MJ, Pandolfi JM, Pears RJ, Pratchett MS, Schoepf V, Simpson T, Skirving WJ, Sommer B, Torda G, Wachenfeld DR, Willis BL, Wilson SK (2017) Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543:373–377. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21707

Jones AM, Gardner S, Sinclair W (2008) Losing “Nemo”: bleaching and collection appear to reduce inshore populations of anemonefishes. J Fish Biol 73:753–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.01969.x

Jones GP, Caley MJ, Munday PL (2002) Rarity in coral reef fish communities. In: coral reef fishes: dynamics and diversity in a complex ecosystem. Academic press pp 81-101

Kritzer JP, Sale PF (2004) Metapopulation ecology in the sea:from Levins’ model to marine ecology and fisheries science. Fish Fish 5:131–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2004.00131.x

Lawton JH (1993) Range, population abundance and conservation. Trends Ecol Evol 8:409–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(93)90043-O

Malcolm H, Scott A (2017) Range extensions in anemonefishes and host sea anemones in eastern Australia : potential constraints to tropicalisation. Mar Freshw Res 68:1224–1232. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF15420

Mitchell JS, Dill LM (2005) Why is group size correlated with the size of the host sea anemone in the false clown anemonefish? Can J Zool 83:372–376. https://doi.org/10.1139/z05-014

Moriarty T, Steinberg RK, Leggat B, et al (2019) Bleaching has struck the southernmost coral reef in the world. Conversat

Munday PL (2004) Habitat loss, resource specialization, and extinction on coral reefs. Glob Chang Biol 10:1642–1647. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00839.x

Nadler LE, Mcneill DC, Alwany MA, Bailey DM (2013) Effect of habitat characteristics on the distribution and abundance of damselfish within a Red Sea reef. Environ Biol Fish 97:1265–1277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-013-0212-9

Noonan SHC, Jones GP, Pratchett MS (2012) Coral size, health and structural complexity: effects on the ecology of a coral reef damselfish. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 456:127–137. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09687

Ollerton J, McCollin D, Fautin DG, Allen GR (2007) Finding NEMO: nestedness engendered by mutualistic organization in anemonefish and their hosts. Proc Biol Sci 274:591–598. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3758

Ormond RFG, Roberts JM, Jan RQ (1996) Behavioural differences in microhabitat use by damselfishes (Pomacentridae): implications for reef fish biodiveristy. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 202:85–95

Pratchett MS, Hoey AS, Wilson SK, Hobbs JPA, Allen GR (2016) Habitat-use and specialisation among coral reef damselfishes. In: Biology of damselfishes. CRC Press, pp. 102–139

Pratchett MS, Munday PL, Wilson SK et al (2008) Effects of climate-induced coral bleaching on coral-reef fishes - ecological and economic consequences. Oceanogr Mar Biol An Annu Rev 46:251–296. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420065756.ch6

R Core Team (2016) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/

Randall J (1998) Zoogeography of shore fishes of the indo-Pacific region. Zool Stud 37:227–268

Randall JE (1976) The endemic shore fishes of the Hawaiian islands, Lord Howe Island and Easter Island. Trav Doc ORSTOM 47:49–73

Richardson DL (1996) Apsects of the ecology of anemonefishes (Pomacentradae: Amphiprion) and giant sea anemones (Actinariaria) within sub-tropical eastern Australian waters. Ph.D. Thesis. Southern Cross University, Lismore

Richardson DL (1999) Correlates of environmental variables with patterns in the distribution and abundance of two anemonefishes (Pomacentridae: Amphiprion) on an eastern Australian sub-tropical reef system. Environ Biol Fish 55:255–263. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007596330476

Richardson DL, Harrison PL, Harriott VJ (1997) Timing of spawning and fecundity of a tropical and subtropical anemonefish (Pomacentridae: Amphiprion) on a high latitude reef on the east coast of Australia. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 156:175–181. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps156175

Ridgway KR (2007) Long-term trend and decadal variability of the southward penetration of the east Australian current. Geophys Res Lett 34:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL030393

Robertson DR (1996) Interspecific competition controls abundance and habitat use of territorial caribbean damselfishes. Ecology 77:885–899

Robinson LM, Gledhill DC, Moltschaniwskyj NA, Hobday AJ, Frusher S, N.Barrett, Stuart-Smith J, Pecl GT (2015) Rapid assessment of an ocean warming hotspot reveals “high” confidence in potential species’ range extensions. Glob Environ Chang 31:28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.12.003

Saenz-Agudelo P, Jones GP, Thorrold SR, Planes S (2011) Detrimental effects of host anemone bleaching on anemonefish populations. Coral Reefs 30:497–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-010-0716-0

Santini S, Polacco G (2006) Finding Nemo: molecular phylogeny and evolution of the unusual life style of anemonefish. Gene 385:19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2006.03.028

Scott A, Hoey AS (2017) Severe consequences for anemonefishes and their host sea anemones during the 2016 bleaching event at Lizard Island, great barrier reef. Coral Reefs 36:873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-017-1577-6

Scott A, Malcolm HA, Damiano C, Richardson DL (2011) Long-term increases in abundance of anemonefish and their host sea anemones in an Australian marine protected area. Mar Freshw Res 62:187–196. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF10323

Scott A, Rushworth KJW, Dalton SJ, Smith SDA (2016) Subtropical anemonefish Amphiprion latezonatus recorded in two additional host sea anemone species. Mar Biodivers 46:327–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12526-015-0390-0

Shuman CS, Hodgson G, Ambrose RF (2005) Population impacts of collecting sea anemones and anemonefish for the marine aquarium trade in the Philippines. Coral Reefs 24:564–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-005-0027-z

Steinberg RK, van der Meer MH, Walker E, Berumen ML, Hobbs JPA, van Herwerden L (2016) Genetic connectivity and self-replenishment of inshore and offshore populations of the endemic anemonefish, Amphiprion latezonatus. Coral Reefs 35:959–970. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-016-1420-5

Thomas L, Stat M, Kendrick GA, Hobbs JPA (2015) Severe loss of anemones and anemonefishes from a premier tourist attraction at the Houtman Abrolhos Islands, Western Australia. Mar Biodivers 45:143–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12526-014-0242-3

van der Meer MH, Berumen ML, Hobbs JPA, van Herwerden L (2014) Population connectivity and the effectiveness of marine protected areas to protect vulnerable , exploited and endemic coral reef fishes at an endemic hotspot. Coral Reefs. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-014-1242-2

van der Meer MH, Hobbs JPA, Jones GP, van Herwerden L (2012) Genetic connectivity among and self-replenishment within island populations of a restricted range subtropical reef fish. PLoS One 7:e49660. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049660

van der Meer MH, Horne JB, Gardner MG, Hobbs JPA, Pratchett M, van Herwerden L (2013) Limited contemporary gene flow and high self-replenishment drives peripheral isolation in an endemic coral reef fish. Ecol Evol 3:1653–1666. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.584

Wiens JA (1989) Spatial scaling in ecology. Funct Ecol 3:385–397

Wilkinson CR (1998) Status of coral reefs of the world. Townsville, Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS)

Wilson DT, McCormick MI (1999) Microstructure of settlement-marks in the otoliths of tropical reef fishes. Mar Biol 134:29–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002270050522

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the valuable support and assistance provided by: S. Gudge and I. Kerr at Lord Howe Island Marine Park; P. Wruck (Oceanpets) at the Sunshine Coast; C. Connell and I. Banton (Dive Quest, Mullaway) and A. Scott at North Solitary Island; D. Biggs (Charter Marine), J. Edward (Bounty Divers), D. Creek, M. Smith, J. Marges, K. Christian, and J. and P. Davidson (Reserves and Forestry) at Norfolk Island; and T. Ayling at Elizabeth and Middleton Reefs. We also thank the reviewers for their comments and the Lord Howe Island Board, Envirofund Australia (Natural Heritage Trust), Lord Howe Island Marine Park, Australian Department of the Environment and Water Resources and the Capricorn Star for funding and/or logistical support.

Funding

This work was financially supported by a GBRMPA Science for Management award, the Griffith/James Cook University collaborative grant scheme (2011), the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, and the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. JP Hobbs was funded by the Australian Research Council DECRA – DE200101286. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

No authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics approval

All applicable national and institutional guidelines for sampling, care, and experimental use of organisms were followed and all necessary approvals were obtained. Permits obtained are Australian Government Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities Permit for Activity in a Commonwealth Reserve number 003-RRRWN-110211-02, New South Wales Marine Parks Permit numbers LHIMP/R/2011/004 and LHIMP/R/2011/004b, and James Cook University Australia Animal Ethics Committee Approval Application ID A1605.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 25 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Steinberg, R.K., van der Meer, M.H., Pratchett, M.S. et al. Keep your friends close and your anemones closer – ecology of the endemic wideband anemonefish, Amphiprion latezonatus. Environ Biol Fish 103, 1513–1526 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-020-01035-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-020-01035-x