Abstract

We implemented GeoGebra software in Rwandan secondary schools to check its effectiveness during teaching and learning geometry concepts. The quasi-experimental design was used, and four schools were purposefully selected. Two schools were from Northern Province, while the other two were selected from Kigali city. A geometry-based test composed of 15 open questions was designed to assess the teaching effect before and after learning geometry.The study was conducted from December 2020 through June 2021 with 87 students. Two schools were assigned as control while the other two as experimental groups. Each group comprised one school from Kigali and one from Northern Province. We analyzed data using SPSS and computed multivariate analysis of variance. We found that students who learned with GeoGebra outperformed those who learned without GeoGebra (M = 77.68% and SD = 14.13 versus M = 56.78% and SD = 15.77, with p < .001 and d = .254). We also found that the number of students who were able to perform each of the 15 questions increased drastically due to the potential of GeoGebra. The study recommends the use of GeoGebra in all teaching and learning activities of mathematics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Integrating information and communication technology (ICT) in the teaching and learning of mathematics and science transforms the quality of education, the teaching methodology, and the ways students and teachers behave towards the subject content (Harrison, 2005). In their study on the use of ICT in mathematics teaching, Keong et al. (2005) indicated that using ICT in mathematics enhances students’ conceptual understanding and performance. Integrating ICT tools provides rapid and direct feedback to students and improves students ‘ability to participate in problem-solving, which can be among the ways of their success in mathematics. When different technologies are provided in teaching mathematics, students become motivated, can look for better strategies which helps them in the problem-solving, interpretation of answers and making graphical representations instead of spending their time in memorizing. Therefore, adopting ICT tools for teaching mathematics influences students’ performance not only in mathematics but also in other subjects.

Chisanda and Chesitit (2015) stated that mathematics is the pure numeric science that uses models that are important tools and instruments in problem-solving. The authors further argued that no government could achieve advanced technology without the proper use of knowledge and skills in mathematics. This is in agreement with Noor-Ul-Amin (2013), who stated that mathematics is the core subject for developing theories and experiments used in daily lives to solve societal and human challenges. Rwanda Basic Education Board (REB, 2015) realized that some efforts are needed, including the revision of the Rwandan curriculum and confirm the integration of ICT tools in the teaching of mathematics and sciences at all levels of education to improve students’ knowledge, skills, and achievements or performances to make them competent.

Literature shows that embracing ICT tools like software, internet, video, and multimedia and other tools like GeoGebra supports the move from the traditional paradigm of teaching to the new teaching and learning (Mukagihana et al., 2021a; Safdar et al., 2011). GeoGebra software as an ICT tool is used to enhance theoretical and practical ways of teaching and learning arithmetic, algebra, calculus, and geometry, resulting in students’ better performance and conceptual understanding in mathematics (Keong et al., 2005). According to Uwurukundo et al. (2020), after reviewing different articles on the effectiveness of GeoGebra in the teaching of mathematics, authors observed that GeoGebra is effective in teaching and learning Mathematics since GeoGebra contributed to enhancing students’ understanding of mathematical concepts and improved students’ interest to learn mathematics.

However, the introduction of ICT tools in the learning process in Rwanda has not been successfully evaluated due to various challenges such as internet accessibility, lack of trained teachers (Ndayambaje & Ngendahayo, 2014). Thus, the researchers see benefits in introducing dynamic software to support the learning and teaching of mathematics topics, especially in the geometry of 3-dimension.

According to Arbain and Shukor (2015) and Ocal (2017), a dynamic Geometry environment is important for teaching and learning mathematics as it allows students to explore both geometry and algebraic presentations of the content structure and facilitate students in making the interpretation. Akgül (2014), in agreement with Naidoo and Govender (2014) and Bridson et al. (2013), confirmed that the use of software helps teachers and learners to perform, explore and interpret mathematics at secondary schools and enhance students’ achievement. Their study findings revealed that among the causes of low performance are students’ negative attitudes and inappropriate technology used when learning mathematics. Various researchers (Arbain & Shukor, 2015; Mathevula & Uwizeyimana, 2014; Niyukuri et al., 2020; Ocal, 2017) stated using GeoGebra in the learning of geometry helps students for the content visualization and understanding through exploration, which improve students’ attitude towards geometry and achievement.

Agyei and Voogt (2011) revealed that using a verbal approach hinders the achievement of optimum objectives of imparting knowledge to students. Their study findings further show that students’ inability to meditate over a jumble of words places them into a dilemma of not remembering concepts taught. This leads to students’ poor performance in mathematics resulting from errors, misconceptions, failure to comprehend mathematics content probably due to unprofessional teachers, inadequate motivation, and inappropriate use of ICT tools like GeoGebra software in the teaching and learning process. According to Maniraho and Mugabo (2019), students need basic learning like geometrical tools and ICT tools that help them while doing classroom activities. This will improve students’ performance and teachers’ ability to track their levels of conceptual understanding. ICT tools like GeoGebra software provide the basis for simulation, data capture, and digital recordings equipment and computer projection during instruction. GeoGebra software integration in a process of teaching and learning points, straight lines and circles of geometry is considerably used in terms of graphical representation and learners’ achievement (Mushipe, 2016). Literature reveals that students who were taught using GeoGebra software to learn geometrical concepts achieve more than those who were taught using traditional methods (Eyyam & Yaratan, 2014; Moses et al., 2012).

Studies were also conducted on teaching and learning geometry, and findings confirmed that students still face challenges in conceptual understanding and achievement. Authors indicated that even if teachers do their best to deliver content to improve students’ achievement, there is still a problem of low performance due to the students’ negative attitude towards geometry and the lack of appropriate software to be used when teaching geometry to facilitate the content manipulation, visualization and understand geometrical content (Shadaan & Leong, 2013). To fix the named problem, Shadaan and Leong (2013) used their study findings to confirm that when GeoGebra is applied to the teaching and learning of geometry, there are positive impacts on students’ understanding, attitudes, and achievement of geometry. However, similar studies were conducted and observed such challenges, but few studies have been conducted on the integration of GeoGebra to examine whether this may have an impact students’ achievement. This motivates a authors to conduct a study on the effectiveness of GeoGebra on the learning of geometry. Since students have shown disinterest in learning mathematics due to the traditional methods used by teachers (Ukobizaba et al., 2021), our findings would help teachers—especially in developing world such as Rwanda—to motivate students to learn mathematics through GeoGebra.

Thus, this study intends to determine the effect of GeoGebra software integration on learners’ achievement in geometry and answer the question: “What is the effect of using GeoGebra on improving secondary school students’ achievement in 3-D geometry? Therefore, we hypothesized that GeoGebra improves students’ academic performance more than the traditional method does. The study adopted Dubinsky and McDonald’s Action Process Object Schema (APOS) Theory (Dubinsky & McDonald, 2001). This learning theory was developed and linked with constructivist theory (Dubinsky, 2001). It was assumed that learners need to construct mental knowledge to understand both theoretical and practical mathematics concepts. According to the APOS theory, learners are supposed to deal with mathematical circumstances by constructing conceptual activities and then transforming them into processes and objects to organize schemas to handle and solve geometrical problems. Dubinsky and McDonald (2001) suggested APOS theory, where students approach perceived mathematical problem situations by constructing actions, internalizing processes, acting on transformations of objects, and constructing schemas to assess situations and solve problems. Maharaj (2013) successfully used the APOS theoretical framework to assess students’ understanding and application of derivatives. Therefore, the present study fits this theory as it involves students in software use to solve mathematical problems to construct and attain knowledge.

2 Methodology

The study adopted a quasi-experimental research method in which there was no random assignment of subjects. This research adopted a quasi-experimental non-equivalent group design (Fraenkel et al., 2012) because students and teachers were not selected randomly; instead, intact classes were selected for not disturbing the academic programs. This design involved both control and experimental groups (Dimitrov & Rumrill, 2003) examined on pre-test and post-test after the exposure to GeoGebra software. The study was conducted in 4 selected schools. Two groups (Experimental and Control) were formed and all exposed to pre-test to see whether all groups were at the same level in the geometry of 3 dimensions and post-test to check if there was statistically significant differences in the mean scores of the experimental and control groups.

The pre-test was used to assess the geometrical knowledge and skills before the intervention on geometry learning in both control and experimental groups. The post-test enabled the researcher to make a comparison between teaching geometry using traditional teaching methods and teaching using GeoGebra software. To collect data for this study, a test was designed. Quantitative data was collected through pre-tests, post-tests using achievement tests. The same test was used to collect data before and after treatment (see Box 1).

Box 1. Geometry-Based Test

1. Show that point A (1, 2, 3) belongs to the sphere x2 + y2 + z2-4x + 2y-2z-8 = 0 | |

2. Find the equation of the plane which passes through points A (1,3,5), B (-2,5,4), and C (3, -6, -5) | |

3. Calculate the angle between two planes x + y + z = 4 and x + 2y + 3z = 5 | |

4. Find the center and the radius of the sphere with equation x2 + y2 + z2—y—2z—14 = 0 | |

5. Find the equation of the line of intersection between two planes 3x—6y—2z = 15 and 2x + y-2z = 5 | |

6. Find the distance between the plane 2x-3y-3z = 12 and 6x-9y-9z = 27 | |

7. Calculate the angle between the lines AB and AC for A (1, 2, 3), B (4, 5, 5) and C (3, 2, 0) | |

8. Find the distance between the plane 3x + 5y-6z = 18 and point A (2, 4, 7) | |

9. Find the angle between the line \(\left\{\begin{array}{c}x=1+r\\ {}y=1+2r\\ {}z=1+3r\end{array}\right.\) and the plane x + y + z = 4 | |

10. Find the angle between vectors \(\overrightarrow{u}=\left(3,8,1\right)\) and \(\overrightarrow{v}=\left(2,4,7\right)\) | |

11. Find the equation of the straight line passing through points A (3, -2, 5) and B (1, 4, -2) | |

12. A line ‘d’ passes through the points A (-2, -1, 4) and B (0,3,4), and plane π has the equation π = 2x-y-3z = 4 | |

a) Show that d is parallel to π | |

b) Calculate the shortest distance between d and π | |

13. Find the intersection of two spheres x2 + y2 + z2 + 2x-6y + 1 = 0 and 4x2 + 4y2 + 4 z2 + 10x-25y-2z = 16 | |

14. Find the equation of the sphere centered at (-6, 1, 3) and with radius R = 4 | |

15. Given two vectors \(\overrightarrow{u}=\left(3,3,3\right)\) and \(\overrightarrow{v}=\left(2,0,-3\right)\) and points A (4, 3, 1) and B (-1, 2, 5) | |

a)Find the equation of the plane passing through | |

i.A point and \(\overrightarrow{v}=\left(2,0,-3\right)\), \(\overrightarrow{u}=\left(3,3,3\right)\) | |

ii.B point and \(\overrightarrow{v}=\left(3,8,1\right),\overrightarrow{u}=\left(0,0,1\right)\) | |

b)Find the angle between these two planes found on points i and ii | |

c)Are these two planes parallel or not? Explain |

This study’s target populations comprised 13 Mathematics teachers and 494 students of Senior Five Mathematics-Physics-Computer (S5 MPC) and Mathematics-Computer-Economics (S5 MCE) combinations from Kicukiro and Musanze districts. This population was found by considering 13 schools from the two selected districts within MPC and MCE combinations and by linking what the report says on the number of students to be in a classroom, which should not exceed a ratio of 38 students per classroom in public, government-aided, and private schools (Ministry of Education, 2018). Finally, four schools were selected from two districts, two schools in Musanze district, Northern Province, and two others in Kicukiro district, Kigali city in Rwanda. The study accommodated a total of 87 students of Senior Five of upper secondary school, aged between 16–19.

Prior to data collection, the research proposal was designed and submitted to the research and innovation unit at the University of Rwanda College of education (URCE) for ethical approval. We got an ethical clearance and used it to seek permission at the district level. We presented it to the selected districts to approve and provide letters to be presented to schools. Our geometry-based test was developed by ourselves and handled by educational evaluators at the URCE for content validation. It was piloted with students from another school apart from those we used before administering it to the real participants in December 2020. Fifteen out of 17 questions were found valid for final administration with a reliability analysis of Pearson r = 0.60 along two weeks. We then administered the pre-test, trained two teachers for experimental groups, and then administered the post-test. The pre-test was given to both groups, control and experimental groups, on paper-based. Teachers were trained on how to install and use GeoGebra within four days. After giving the pre-test to all students, we gave the go-ahead to all four teachers to start teaching geometry of 3-dimension. Teachers from the control group used the conventional teaching methods, using board and chalks, and teachers from the experimental group used GeoGebra as a supporting tool for teaching geometry. In the control group, the teacher introduced the content, and students were given tasks to perform in their notebooks or on the board (performing the questions and drawing charts). The teacher introduced the content in experimental groups, and students used GeoGebra to answer the questions and draw charts. GeoGebra is a dynamic software that facilitates the learning process of the geometry of 3 dimensions. It is said to be dynamic because it is used without an internet connection. It gives room for users to manipulate the software and the content. GeoGebra helps users to put coordinates of points, lines, equations of planes, and spheres. GeoGebra can allow users to solve geometry-related problems and make their interpretations. For example, Given the following points of the vertices of the triangle ABC where A (1, 2, 3), B (4, 5, 5), and C (3, 2, 0).

-

a)

Plot them on 3-D space and join them to form a triangle

-

b)

Calculate the perimeter of the triangle ABC

-

c)

Find the coordinate of the center of gravity (centroid) of the triangle ABC

-

d)

Calculate the area of triangle ABC

Geogebra is free and easy to install. However, careful input of data is required. Figure 1 shows the outcome of the above example.

After six weeks (May—June 2021), the post-test was given to both groups to check whether there is a significantly difference between students taught using the conventional method and those taught using GeoGebra software. Note that the whole unit of geometry in senior one takes 34 periods of 40 min.

3 Data analysis and Results

We analyzed data using a statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 23. We entered students’ scores of all 15 questions into the SPSS data view and then named the variables in variables views. The first column was “students’ group,” where “1” represented the control group and “2” represented the experimental group. Thus, the next two columns of data were pre-and post-test scores for both groups. Via ‘transform,’ we computed the average score (percentage) for each student. We first checked the normality of our score distribution to choose appropriate tests among parametric tests. We plotted histograms for pre-test scores and post-test scores with normal curves (see Fig. 2).

Some variables such as score ranges, skewness, and kurtosis were also computed. Skewness is a measure of the symmetry of a distribution where for instance, a negative skew indicates the long tail on the left side than one on the right side. Thus, skewness measures the relative size of the two tails, while kurtosis measures the combined sizes of the two tails. For instance, kurtosis greater than + 1 indicates that the distribution is too peaked. We found that our data were normally distributed skewness of control and experimental groups were 1.32 and 1.15, respectively, and kurtosis was 2.36 (for the control group) and 1.64 (for the experimental group). Note that the data is considered to be normal if its skewness is between ‐2 to + 2 and its kurtosis is between ‐7 to + 7 (Hair et al., 2010). The control group’s minimum and maximum (or range) scores were 0.00 and 42.35%,, respectively, while they were 0.00 and 43.53% for the experimental group. Thus we ensured to use of parametric tests such as t-test, analysis of variances. We then computed the significance of the mean score of the pre-test among both the control and experimental group to ensure the equivalence of mean scores of both groups before intervention. We found that the groups were homogeneous (p > 0.05). This ensured that our groups were at the same level before teaching intervention and had no covariates among their scores.

Since we had two independent variables (control and experiment groups) and two dependent variables (pre-and post-test), t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were not appropriate, and we were obliged to use repeated measures such as multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Via “analysis” ribbon, general linear model function, and repeated measure test, we computed the mean scores and statistical significance and plotted the visual graph of intervention groups alongside tests done. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics, while Table 2 presents inferential statistics.

Students in the control group got 13.41%, while those in the experimental group got 14.58% in the pre-test. Likewise, students in the control group got 56.78%, while those in the experimental group got 77.68% in the post-test. “N” is the sample in each group. Table 2 shows that from pre-test to post-test, students gained more irrespective of the teaching intervention provided (whether traditional or Geogebra). This gain was very high significant (p < 0.001) with a very large effect size (d = 0.909). According to Magnusson (2021), researchers often use general guidelines, such as small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (0.8), when interpreting effect size. Likewise, considering the effect of traditional and Geogebra teaching intervention, a very high statistically significant difference occurred between students in control and those in experimental groups in favor of those in the experimental group (those taught by Geogebra).

The same results in Table 2 can be well visualized in Fig. 3. It can be interpreted in a way that students’ pre-test scores in both control and experimental groups were at the same level; however, their scores shifted to above 50% scores with a large difference from control to experimental group during post-test (see Fig. 3).

4 Discussion of results

From the results above, it can be realized that GeoGebra shows an outstanding active and teaching technique that increases students’ performance. Therefore, we retain our Null hypothesis that there was statistically significant difference between students’ mean scores taught by computer-assisted learning (those taught with GeoGebra) and those taught by traditional teaching methods (those learned without GeoGebra). Our study demonstrated that students who learned with GeoGebra software were advantaged and succeeded more than their counterparts who did not learn with that software. Although those who learned without the software got an average score (more than 50%), however, those who learned with the software outperformed their counterparts. Their average shows this at the post-test stage, where those in the control group (learning without GeoGebra) got 56.78% while those in the experimental group (learning with GeoGebra) got 77.68%. And this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001). This is in agreement with Doğan and İçel (2010), who confirmed the effectiveness of GeoGebra on students’ attitude and achievement as it is used to improve their motivation which brings them to the high performance of geometry. The specific reason why this software was effective is that it allows students to visualize what they are learning. Students are also using technology to learn; therefore, they are motivated to manipulate a computer and grasp academic performance. In the literature, Ukobizaba et al. (2021) found that students lose interest in learning mathematics due to poor teaching methods. Therefore, this study showed a new and technological tool to motivate teachers in their daily routine.

More studies promoting ICT-related teaching approaches also showed statistical significance in students’ performance over traditional methods. For instance, Mukagihana et al. (2021b) observed and found the effectiveness of animations during pre-service teachers academic biology performance, (Iyamuremye et al., 2021) found a good impact of web-based discussions in the teaching and learning of chemistry, and Uwamahoro et al. (2021) found the effectiveness of computer simulation to upgrade students’ knowledge of light phenomena. Zulnaidi and Zamri (2017) used a quasi-experimental approach to investigate the effects of GeoGebra software on mathematical, conceptual understanding, and achievement. The study findings show that students who were taught using GeoGebra software had higher conceptual understanding and achievement than those taught using traditional methods. The authors confirm the capability of GeoGebra in enhancing students ‘conceptual understanding of mathematics. According Rubagiza et al. (2011), integrating ICT tools in the learning process of mathematics results in the learners’ better performance and teachers’ positive attitudes towards the use of GeoGebra software in teaching mathematics. The outcome of our GeoGebra teaching and learning facility is underpinned by its visual form and transferability of knowledge to skills. Students can see and manipulate on the computer. Such hands-on effect was shown by Ndihokubwayo et al., (2020a, 2020b), where the authors alerted that when students are given the opportunity to hands-on computer and manipulate PhET simulations, they gain more in terms of attitude, performance, and conceptual understanding.

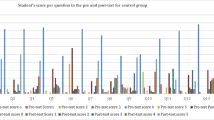

The effectiveness of GeoGebra we realized in this study may also be well shown by the rate of students who could answer or perform each of the 15 questions’ tests. Figure 4 shows that students most likely performed similarly before learning geometry. Thus, the same number of students in control or experimental groups scored in a similar score range. For instance, more than the average population (50%) in the control group could not get a score above 25%. Thus, about 78% of students scored between 0 and 25%. Likewise, all 90% of students in the experimental group scored between 0 and 25%. The blue color shows the number (%) of students who only got a score below or 25% on each test’ question.

However, after learning Geometry, students in experimental groups (those learned with GeoGebra) easily performed or increased in number during performing each of the test’s questions (see Fig. 4). See, for example; the yellow color shows a large number of students in the experimental than in the control group who were able to score above 75% (between 76 and 100%). Note that the stacked vertical bar is an accumulation of data where all intervals share 100%. Thus, 0–25, 26–50, 51–75, and 76–100 share 100%.

A typical example is on question-6, where about 69% of students are still scoring in the 0–25% range even after learning. This is understandable as these students were assigned to a control group where there was no support of GeoGebra software. The question was about finding the distance between the plane 2x-3y-3z = 12 and 6x-9y-9z = 27, and such information is well articulated by the software rather than traditional or hand manipulation such as drawing on the blackboard (see Fig. 5 during the teaching of such concept).

Question-5 also asked to find the equation of the line of intersection between two planes 3x—6y—2z = 15 and 2x + y-2z = 5. And GeoGebra was better at tackling such issues. Students in the experimental group who performed this question maximally increased (86%). Figure 6 demonstrates how the concept was taught.

Question-13 was asking to find the intersection of two spheres x2 + y2 + z2 + 2x—6y + 1 = 0 and 4x2 + 4y2 + 4 z2 + 10x—25y—2z = 16, and students (mostly, in experimental group) who were able to answer the question after learning increased. Figure 7 shows how question-13 related concept would be performed into GeoGebra.

However, it seemed students were challenged during answering question-12. [A line “d” passes through the points A (-2, -1, 4) and B (0, 3, 4) and plane π has the equation π = 2x-y-3z = 4; (a) Show that d is parallel to π, (b) Calculate the shortest distance between d and π]. The number of students who could get 51–75% or 76–100% scores did not increase drastically even if they learned with GeoGebra. Figure 8 shows how question-12 related concepts would be performed into GeoGebra.

The difficulty of question-12 related concepts would be depicted from the fact that GeoGebra needs careful manipulation. Although GeoGebra allows students to manipulate, observe, visualize and interpret, its mastery is needed. In our future investigation, we will investigate the relationship between students’ mathematical performance and the mastery of GeoGebra software. Action process object schema (APOS) theory supported our results in a line that it has shown the potentials to advance and upgrade students’ learning to and from secondary school level (Arnon et al., 2014; Maharaj, 2013). When students learn by observing and manipulating, they can understand what they took as abstract when blackboard and chalk were only available as teaching aids.

5 Concluding remark

Our study intended to determine the effect of GeoGebra software integration on learners’ achievement in geometry. We employed 87 students from four schools in Rwanda. Fourty-five students were assigned to the control group and asked their teachers to teach using traditional teaching. Fourty-two students were assigned in an experimental group where we asked their teachers to teach them using GeoGebra. Students were learning Geometry, and we formulated a performance test to evaluate the teaching intervention. We hypothesized that there would not be a difference between these groups’ mean scores after learning. However, a very high statistically significant difference existed after teaching students using different methods in favor of those taught using GeoGebra was found. At the initial stage, students were found on the same level as the average score was 13.41% in the control group while 14.58% was in the experimental group. After learning geometry, the same test was given to both groups, and the experimental group has increased their performance (77.68% versus 56.78%). We concluded that GeoGebra has the potentiality to increase students’ performance. Therefore, the outcome results recommend that teachers should adapt teaching using GeoGebra. Our specific recommendations are following:

-

Rwanda Basic Education (REB) should train teachers to use ICT integration in education software such as GeoGebra.

-

Although hardware and software components are expensive to acquire and sustain in many Rwandan secondary schools, schools’ leaders should include ICT materials in their budgets and adopt ICT usage during the teaching–learning process, and capture data about the education context inputs and outputs.

-

Since our sample size was limited, further studies may look into the effects of gender difference, school environment, students’ attitudes, and teachers’ appreciation of the use of GeoGebra.

References

Agyei, D. D., & Voogt, J. (2011). ICT use in the teaching of mathematics: Implications for professional development of pre-service teachers in Ghana. Education and Information Technologies, 16(4), 423–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-010-9141-9

Akgül, M. B. (2014). The Effect of using dynamic geometry software on eight grade students’ achivement in transformation geometry, geometric thinking and attitudes toward mathematics and technology. Middle East Technical University.

Arbain, N., & Shukor, N. A. (2015). The effects of GeoGebra on students achievement. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 172(January), 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.356

Arnon, I., Cottrill, J., Dubinsky, E. D., Oktaç, A., Fuentes, S. R., Trigueros, M., & Weller, K. (2014). APOS theory: A framework for research and curriculum development in mathematics education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7966-6

Bridson, M. R., Howie, J., Miller, C. F., III., & Short, H. (2013). On the finite presentation of subdirect products and the nature of residually free groups. American Journal of Mathematics, 135(4), 891–933. https://doi.org/10.1353/ajm.2013.0036

Chisanda, P., & Chesitit, B. (2015). Impact of ICT Integration on Mathematics Performance in Kenya: A Case Study of Public Secondary Schools in West Pokot County. November.

Dimitrov, D. M., & Rumrill, P. D. (2003). Pretest-posttest designs and measurement of change. Work, 20(2), 159–165.

Doğan, M., & İçel, R. (2010). Effect of using GeoGebra on students’ success: An example about triangles. Third International Conference on Innovations in Learning for the Future.

Dubinsky, E., & McDonald, M. A. (2001). APOS: A constructivist theory of learning in undergraduate mathematics education research. In The teaching and learning of mathematics at university level (pp. 275–282). Springer, Dordrecht.

Dubinsky, Ed. (2001). Using a Theory of Learning in College Mathematics Courses. MSOR Connections, 1(2), 10–15.

Eyyam, R., & Yaratan, H. S. (2014). Impact of use of technology in mathematics lessons on student achievement and attitudes. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(1), 31S-42S. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2014.42.0.S31

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., & Hyun, H. H. (2012). How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education (8th ed.). McGraw Hill.

Hair, J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Educational International.

Harrison, B. (2005). Information and Communication Technology Policy in Rwanda.

Iyamuremye, A., Mukiza, J., Nsabayezu, E., Ukobizaba, F., & Ndihokubwayo, K. (2021). Web-based discussions in teaching and learning: Secondary school teachers’ and students’ perception and potentiality to enhance students’ performance in organic chemistry. Education and Information Technologies, 0123456789.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10725-7

Keong, C. C., Horani, S., & Daniel, J. (2005). A Study on the Use of ICT in Mathematics Teaching. Malaysian Online Journal of Instructional Technology (MOJIT), 2(3), 43–51. file:///C:/Users/dirgha12/Downloads/A_Study_on_the_Use_of_ICT_in_Mathematics_Teaching.pdf

Magnusson, K. (2021). Interpreting Cohen’s d Effect Size: An Interactive Visualization. https://rpsychologist.com/cohend/

Maharaj, A. (2013). An APOS analysis of natural science students’ understanding of derivatives. South African Journal of Education, 33(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v33n1a458

Maniraho, J. F., & Mugabo, L. R. (2019). Grade Six Learners’ Performance in Mathematics: A Comparison between Rwanda, Botswana and South Africa. Journal of Research Innovation and Implications in Education, 3(1), 17–22. https://jriiejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/JRIIE-3-1-003.pdf

Mathevula, M. D., & Uwizeyimana, D. E. (2014). The Challenges Facing the Integration of ICT in Teaching and Learning Activities in South African Rural Secondary Schools. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 20(5), 1087–1097. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p1087

Ministry of Education. (2018). 2018 EDUCATION STATISTICS Dec (Vol. 15, Issue 2). https://doi.org/10.22201/fq.18708404e.2004.3.66178

Moses, P., Bakar, K. A., Mahmud, R., & Wong, S. L. (2012). ICT Infrastructure, Technical and Administrative Support as Correlates of Teachers’ Laptop Use. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 59, 709–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.335

Mukagihana, J., Nsanganwimana, F., & Aurah, C. M. (2021a). Effect of instructional methods on pre-service science teachers learning outcomes: a meta-analysis. Education and Information Technologies, 0123456789.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10696-9

Mukagihana, J., Nsanganwimana, F., & Aurah, C. M. (2021b). How Pre-service Teachers Learn Microbiology using Lecture, Animations, and Laboratory Activities at one Private University in Rwanda. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 20(7), 328–345. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.20.7.18

Mushipe, M. (2016). Effects of integrating GeoGebra into the teaching of linear functions on Grade 9 learners’ achievement in Mopani district. University of South Africa.

Naidoo, J., & Govender, R. (2014). Exploring the use of a dynamic online software programme in the teaching and learning of trigonometric graphs. Pythagoras, 35(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.4102/pythagoras.v35i2.260

Ndayambaje, I., & Ngendahayo, E. (2014). The use of computer based instructions to enhance Rwandan Secondary School Teachers’ ICT competency and continuous professional development. Rwanda Journal of Education, 2(2), 56–70.

Ndihokubwayo, K., Uwamahoro, J., & Ndayambaje, I. (2020a). Effectiveness of PhET Simulations and YouTube Videos to Improve the Learning of Optics in Rwandan Secondary Schools. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 24(2), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/18117295.2020.1818042

Ndihokubwayo, K., Uwamahoro, J., & Ndayambaje, I. (2020b). Usability of Electronic Instructional Tools in the Physics Classroom. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 16(11), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/8549

Niyukuri, F., Nzotungicimpaye, J., & Ntahomvukiye, C. (2020). Pre-Service Teachers’ Secondary School Experiences in Learning Geometry and Their Confidence to Teach It. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education, 16(8), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/8334

Noor-Ul-Amin, S. (2013). An effective use of ICT for education and learning by drawing on worldwide knowledge, research, and experience: ICT as a Change Agent for Education. India: Department of Education, University of Kashmir, 1–13. Scholarly Journal of Education, 2(4), 38–54.

Ocal, M. F. (2017). The Effect of Geogebra on Students’ Conceptual and Procedural Knowledge: The Case of Applications of Derivative. Higher Education Studies, 7(2), 67–78.

REB. (2015). Comptence-Based Curriculum. Curriculum Framework Pre-Primary to Upper Secondary. http://reb.rw/fileadmin/competence_based_curriculum/syllabi/curriculum_framework_final_printed.compressed.pdf

Rubagiza, J., Were, E., & Sutherland, R. (2011). Introducing ICT into Schools in Rwanda: Educational Challenges and Opportunities. International Journal of Educational Development, 3(1), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.06.004

Safdar, A., Yousuf, M. I., Parveen, Q., & Behlol, M. G. (2011). Effectiveness of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in Teaching Mathematics at Secondary Level. International Journal of Academic Research, 3(5), 67–72.

Shadaan, P., & Leong, K. E. (2013). Effectiveness of Using GeoGebra on Students’ Understanding in Learning Circles. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Technology, 1(4), 1–11.

Ukobizaba, F., Ndihokubwayo, K., Mukuka, A., & Uwamahoro, J. (2021). From what Makes Students Dislike Mathematics towards its Effective Teaching Practices Do que faz com que os alunos não gostem da matemática em direção às práticas de ensino eficazes. Bolema: Boletim de Educação Matemática, 35(70), 1200–1216.

Uwamahoro, J., Ndihokubwayo, K., Ralph, M., & Ndayambaje, I. (2021). Physics Students’ Conceptual Understanding of Geometric Optics: Revisited Analysis. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 30(0123456789), 706–718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-021-09913-4

Uwurukundo, M. S., Maniraho, J. F., & Tusiime, M. (2020). GeoGebra integration and effectiveness in the teaching and learning of mathematics in secondary schools : A review of literature. In African Journal of Educational Studies in Mathematics and Sciences (Vol. 16, Issue 1).

Zulnaidi, H., & Zamri, S. N. A. S. (2017). The Effectiveness of the GeoGebra Software: The Intermediary Role of Procedural Knowledge on Students’ Conceptual Knowledge and their Achievement in Mathematics. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education, 13(6), 2155–2180. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.01219

Acknowledgements

We got full financial support from the African Center of Excellence for Innovative Teaching and Learning Mathematics and Science (ACEITLMS) based in the University of Rwanda College of Education. This support is highly acknowledged. We would also like to pay gratitude to students and teachers in selected schools in Kigali and Musanze.

Funding

Corresponding author received the support from the African Centre of Excellence for Innovative Teaching and Leaning Mathematics and Science (ACEITLMS), University of Rwanda College of education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this study. More information can be given when needed.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Uwurukundo, M.S., Maniraho, J.F. & Tusiime Rwibasira, M. Effect of GeoGebra Software on Secondary School Students’ Achievement in 3-D Geometry. Educ Inf Technol 27, 5749–5765 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10852-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10852-1