Abstract

Background

Screening with fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) reduces colorectal cancer mortality; however, screening remains low in underserved populations. Mailed outreach, including an invitation letter, FIT, and test instructions, is an evidence-based strategy to improve screening.

Aims

To examine screening completion and yield in a mailed outreach program in a safety-net healthcare system.

Methods

We identified and mailed outreach invitations to patients due for screening in a large safety-net system between September 1, 2018, and August 31, 2019. We examined: (1) screening completion, the proportion of patients completing FIT or screening colonoscopy within 6 months of the mailed invitation; and (2) timely diagnostic colonoscopy, the proportion of patients completing colonoscopy within 6 months of positive FIT.

Results

We mailed 14,879 invitations to 13,190 patients. Nearly half (n = 6098, 46.2%) of patients completed screening: 4,896 (80.3%) completed FIT through mailed outreach; 1,114 (18.3%) FIT through usual care; and 88 (1.4%) screening colonoscopy through usual care. Of patients with a positive FIT (n = 289), 50.5% completed diagnostic colonoscopy within 6 months, 10.7% within 6–12 months, and 4.8% after 12 months. A total of 8 cancers and 83 advanced adenomas were detected in the 191 patients completing diagnostic colonoscopy.

Conclusion

After implementing and scaling up mailed outreach in a safety-net system, about half of patients completed screening, and the majority did so through mailed outreach. However, many patients failed to complete diagnostic colonoscopy after positive FIT. Results highlight the importance of adapting mailed outreach programs to local contexts and constraints of healthcare systems, in order to support efforts to improve CRC screening in underserved populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) with stool-based tests, including guaiac-based fecal occult blood tests (gFOBT) and fecal immunochemical tests (FIT), can reduce colorectal cancer mortality [1]. However, screening lags far behind the national goal of 80% screened [2,3,4,5], with particularly low participation in underserved populations [5,6,7,8], For example, data from the 2018 National Health Interview Survey show that, compared to White persons (67.9%), screening is lowest among American Indian/Alaska Native (54.7%), followed by Asian (58.1%) and Black (65.3%) persons. Screening is also low among Latinos (57.6%), adults with less than a high school education (54.2%), and those without insurance (30.2%) [5]. Disparities in screening contribute to an excess burden of CRC in these populations, and more recent evidence suggests disparities have worsened over time [6, 8].

Mailed outreach offering stool-based tests (hereafter, “mailed FIT outreach”) is an evidence-based strategy to improve screening and address barriers at the system, provider, and patient levels [9, 10]. Several randomized trials demonstrate effectiveness of mailed FIT outreach, with increases in screening ranging from 18 to 36% compared to usual care [9]. Many of these trials were conducted in underserved populations: we previously demonstrated that mailed FIT outreach increased one-time screening completion by nearly 30%, and increases in screening persisted over a three-year period in a large, safety-net healthcare system [11, 12]. With mounting evidence of efficacy, an important next step is to implement and scale up mailed FIT outreach in large healthcare systems or population health management programs [13].

Herein, we report screening completion and yield after implementing a mailed FIT outreach program in a large safety-net healthcare system.

Methods

Study Setting and Population

In September 2018, we implemented a mailed FIT outreach program at Parkland Health & Hospital System, Dallas County’s safety-net healthcare system. Parkland is a vertically integrated health system, including an 880-bed inpatient hospital, 12 community-based primary care clinics, and outpatient specialty clinics. Parkland uses a comprehensive electronic health record (EHR) to integrate care across inpatient and outpatient settings. Parkland provides low-cost primary and specialty care to under- and uninsured residents of Dallas County through a sliding-fee program funded by county tax dollars.

We identified patients in primary care and due for screening (age 50–64 years; no colonoscopy within 10 years or sigmoidoscopy within 5 years). We mailed eligible patients a one-sample FIT (Polymedco OC-Auto FIT CHEK), instructions for completing the test, and a postage-paid return envelope. All materials were in English and Spanish. Patients received up to three reminder calls from bilingual program staff, 2–3 weeks after the mailed invitation.

Program staff notified patients by mail of a positive FIT (pre-specified hemoglobin concentration cutoff 100 ng/mL) within seven days of the result; a nurse practitioner then contacted patients by phone and referred them for diagnostic colonoscopy. To assist with scheduling, program staff sent the endoscopy unit a weekly list of patients referred for diagnostic colonoscopy. Patients received reminder calls from program staff and the endoscopy unit five and two days prior to colonoscopy, respectively, to review instructions for bowel preparation and address questions. Diagnostic colonoscopy required a patient co-payment ranging from $0–50, depending on income.

All patients continued to receive opportunistic, visit-based screening and follow-up as part of usual care, and patients may have received a FIT or have been referred to screening colonoscopy during a primary care visit [14]. Therefore, patients completed screening with either: (1) FIT through mailed outreach; (2) FIT through usual care; or (3) screening colonoscopy through usual care.

Statistical Analysis

We examined two outcomes: (1) screening completion, defined as the proportion of patients returning a FIT or completing screening colonoscopy within 6 months of the mailed invitation; and (2) timely diagnostic colonoscopy, defined as the proportion of patients completing diagnostic colonoscopy within 6 months of a positive FIT. In sensitivity analysis, we examined the proportion of patients completing diagnostic colonoscopy within 6–12 months and after 12 months of positive FIT.

We used logistic regression to identify correlates of screening completion, including age, sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other), number of primary care visits ≤ 12 months of mailed invitation (1,2, ≥ 3), prior FIT completion (≤ 12 months of mailed invitation), and comorbidity score (0, 1–2, or ≥ 3) [15]. Associations between screening completion and correlates are reported as unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Finally, among those with a positive FIT, we described yield of diagnostic colonoscopy, including CRC and advanced adenoma. Using a structured data form to collect information from colonoscopy and pathology reports [16], we defined advanced adenoma as any adenoma with villous histology, high-grade dysplasia, or ≥ 10 mm or ≥ 3 adenomas of any size or histology.

Results

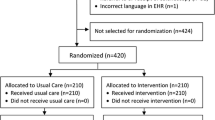

From September 1, 2018, to August 31, 2019, we mailed 14,879 invitations to 13,190 patients (Fig. 1). Median age was 57 years (IQR 53–60 years). Most patients were female (61.3%) and Hispanic (51.1%) or non-Hispanic Black (33.8%), as shown in Table 1.

Overall, 6,098 (46.2%) patients completed screening: 4896 (80.3%) completed FIT through mailed outreach; 1114 (18.3%) FIT through usual care; and 88 (1.4%) screening colonoscopy through usual care. Among patients completing FIT through mailed outreach (n = 4,896), median time to screening completion was 20 days (IQR: 12–35 days). About half (n = 2,620, 53.5%) returned the FIT prior to a reminder call, and 25.4% (n = 1243) and 21.1% (n = 1,033) returned the FIT after one and two reminder calls, respectively.

In adjusted analysis, female sex (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.16, 1.33), race, and ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black: OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.12, 1.44; Hispanic: OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.51, 1.92), prior FIT completion (OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.33, 1.63), and prior primary care visits (2 visits: OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.15, 1.36) were associated with screening completion (Table 2).

Some patients (n = 965) returned FITs that could not be processed due to an insufficient specimen (n = 487), incomplete label (n = 219), leaking or broken container (n = 176), or specimen too old (n = 83). Of these, 509 were mailed another invitation and 234 subsequently returned a FIT. A total of 5,045 FITs were resulted, of which 289 (5.7%) were positive.

Of patients with a positive FIT (n = 289), 50.5% (n = 146) completed a diagnostic colonoscopy within 6 months, 10.7% (n = 31) within 6–12 months, and 4.8% (n = 14) after 12 months. About one-third (n = 98) of patients never completed diagnostic colonoscopy, for reasons including: colonoscopy never scheduled (n = 57), patient did not attend the scheduled appointment (n = 9), patient declined or refused (n = 11), medical comorbidity (n = 7), cost or insurance coverage (n = 4), acute illness including COVID-19 infection (n = 3), and other or not specified (n = 7).

A total of 6 cancers and 66 advanced adenomas were detected in the 146 patients completing diagnostic colonoscopy within 6 months of positive FIT. An additional 1 cancer and 13 advanced adenomas and 1 cancer and 4 advanced adenomas were detected in the patients completing diagnostic colonoscopy within 6–12 months (n = 31) and after 12 months (n = 14) of positive FIT, respectively.

Discussion

Mailed FIT outreach for CRC screening has been extensively tested in randomized trials and has a robust evidence base for increasing screening [9, 10, 17], particularly in underserved populations [11, 18]. We implemented and scaled up mailed FIT outreach in a large safety-net healthcare system; eligible patients were engaged in primary care with no or very low out-of-pocket costs of screening. About half of eligible patients completed screening, and a similar proportion with positive FIT completed diagnostic colonoscopy. The most common reason for no diagnostic colonoscopy was insufficient endoscopic capacity. These results highlight the importance of adapting mailed FIT outreach to the local context and constraints of healthcare systems, in order to support continued efforts to improve CRC screening in underserved populations.

Screening completion (46.2%) in our program was similar to randomized trials (26–56%) of mailed FIT outreach, and the majority of patients completing screening did so through mailed outreach vs. usual care. These findings suggest mailed FIT outreach, when scaled up and implemented in a large safety-net health system, worked as intended by engaging patients outside of the context of a primary care visit (80% screened through mailed outreach screened) or by prompting patients to discuss screening with their physician (20% screened through usual care). Observational studies similarly support the effectiveness of mailed outreach. For example, in a large integrated healthcare system, an organized CRC screening program with mailed outreach doubled the proportion of adults up-to-date with screening (from 40% to over 80%) [19, 20]. The increase in screening was associated with a decrease in CRC incidence and mortality of 26% and 52%, respectively. In Europe, many studies report similar success with mailed outreach as part of nationwide programs implementing organized screening [21], with up to 60% of participants returning a test kit by mail. Our program extends this literature by demonstrating similar effectiveness in an underserved and often difficult-to-reach patient population. Collectively, these findings suggest organized screening programs with mailed outreach have the potential to achieve national screening goals and reduce cancer mortality in both majority, privately insured and minority, underserved populations.

As part of our mailed FIT outreach program, patients could continue to receive opportunistic, visit-based screening and follow-up as part of usual care, and patients may have been referred to screening colonoscopy during a primary care visit. However, very few (1.4%) crossed over to complete screening colonoscopy through usual care, suggesting patients and providers in our program preferred a “FIT First” screening strategy. Several studies of patient preferences for CRC screening similarly suggest patients less interested in getting screened prefer stool-based tests, which require less planning and preparation, are more convenient, and are less invasive than colonoscopy [22]. Incorporating these preferences in mailed outreach may increase the likelihood patients initiate screening. For example, several randomized trials now demonstrate patients initially offered FIT, or a choice between FIT and colonoscopy, are more likely to complete screening [23,24,25].

Despite the promise of mailed FIT outreach, still, the majority of patients in our program never completed screening; other patients returned a FIT but the test could not be resulted. One-time completion or initial uptake of screening continues to be a rate-limiting step in adherence to the screening process for safety-net populations [16, 26]. With the exception of primary care visits [27] and prior FIT completion, findings from the adjusted logistic model provide little insight into which patients complete screening. Patient-level factors, such as competing demands, mistrust, and fatalism [28]—not captured in our program—may more strongly predict screening completion than sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Similarly, among patients with a positive FIT, about half completed diagnostic colonoscopy within 6 months. Even with the assistance of a nurse practitioner and weekly tracking between program staff and the endoscopy unit, only an additional 15% of patients completed diagnostic colonoscopy after 6 months. Others have similarly reported suboptimal follow-up of positive FIT, ranging from 18 to 57% in safety-net health systems [29,30,31]. This is especially concerning because delays in diagnostic colonoscopy increase risk of advanced adenoma, any CRC, and advanced-stage disease [32, 33]. An ongoing challenge is that much of the literature is descriptive and focuses on patient characteristics associated with timely follow-up [34]. In our program, however, many of the reasons for delayed or no diagnostic colonoscopy were related to system-level factors, including insufficient endoscopic capacity or the patient was never scheduled [35]. These system-level factors persisted despite our program staff working closely with the endoscopy unit to identify patients referred but not scheduled for diagnostic colonoscopy. Provider- and system-level strategies that identify, report, and resolve abnormal findings may be better suited for diagnostic colonoscopy than patient-level interventions [36, 37]. These strategies may include prioritizing scheduling of diagnostic vs. screening colonoscopy; implementing standard tracking and reporting procedures; administrative algorithms that identify the appropriate follow-up needs of individual patients based on test results; and automated phone calls linked to test results, progressing to personal phone calls, as needed [38, 39]. More intensive navigation may also be needed to reduce disparities in follow-up among underserved patients [40].

As a growing number of healthcare systems adopt mailed FIT outreach, several unknowns remain, including sustainability and long-term effectiveness, and that we could not address given the timing and duration of our program. For example, effectiveness of FIT-based screening may be reduced when patients do not complete repeat screening every 1–2 years [41,42,43,44]. Although there may be fewer barriers to one-time FIT completion than one-time colonoscopy, repeat FIT in community settings varies widely—from 25 to 88%—and generally declines across successive screening rounds [45,46,47]. In addition, COVID-19 has impacted CRC screening programs across the USA, particularly in federally qualified health centers and other resource-constrained settings, and the volume of screening tests and procedures has substantially dropped [48, 49]. For underserved populations with already limited access to care, completing screening and timely follow-up will be a greater challenge now and in the future [50]. Finally, some guidelines recommend initiating average-risk screening at age 45 (vs. 50) years [51], and expanding screening to younger, lower-risk adults may burden health systems with already limited endoscopic capacity. There are few data on acceptability and yield of mailed FIT in younger adults. A pilot study conducted among Black patients suggests a similar proportion screened (33%) and yield (5% positive) of mailed FIT outreach in younger compared to older unscreened patients [52].

In summary, broadly implementing mailed FIT outreach may bring the current CRC screening prevalence of 65% [5] closer to the national goal of 80% [53]. Our experience implementing mailed FIT outreach in a safety-net health system included some successes but also points to several components of outreach that need to be addressed in order to further increase screening participation in underserved populations, including: (1) increase initial screening; (2); increase capacity for diagnostic colonoscopy; (3) implement system-level strategies to identify and track abnormal test results; and (4) more intensive navigation to communicate test results to patients and schedule diagnostic colonoscopy.

References

Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Jama 2016;315:2576–2594.

Paskett ED, Khuri FR. Can we achieve an 80% screening rate for colorectal cancer by 2018 in the United States? Cancer 2015.

Fedewa SA, Ma J, Sauer AG et al. How many individuals will need to be screened to increase colorectal cancer screening prevalence to 80% by 2018? Cancer 2015;121:4258–4265.

White A, Thompson TD, White MC et al. Cancer Screening Test Use - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:201–206.

Sabatino SA, Thompson TD, White MC et al. Cancer Screening Test Receipt - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:29–35.

May FP, Yang L, Corona E et al. Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening in the United States Before and After Implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:1796-1804.e2.

May FP, Yano EM, Provenzale D et al. Race, Poverty, and Mental Health Drive Colorectal Cancer Screening Disparities in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care 2019;57:773–780.

Viramontes O, Bastani R, Yang L et al. Colorectal cancer screening among Hispanics in the United States: Disparities, modalities, predictors, and regional variation. Prev Med 2020;138:106146.

Jager M, Demb J, Asghar A, et al. Mailed Outreach Is Superior to Usual Care Alone for Colorectal Cancer Screening in the USA: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci 2019.

Gupta S, Coronado GD, Argenbright K et al. Mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach for colorectal cancer screening: Summary of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-sponsored Summit. CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:283–298.

Singal AG, Gupta S, Tiro JA et al. Outreach invitations for FIT and colonoscopy improve colorectal cancer screening rates: A randomized controlled trial in a safety-net health system. Cancer 2016;122:456–463.

Singal AG, Gupta S, Skinner CS et al. Effect of Colonoscopy Outreach vs Fecal Immunochemical Test Outreach on Colorectal Cancer Screening Completion: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2017;318:806–815.

Green BB. Colorectal Cancer Control: Where Have We Been and Where Should We Go Next? JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1658–1660.

Murphy CC, Ahn C, Pruitt SL et al. Screening initiation with FIT or colonoscopy: Post-hoc analysis of a pragmatic, randomized trial. Prev Med 2019;118:332–335.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–1139.

Murphy CC, Sigel BM, Yang E, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening measured as the proportion of time covered. Gastrointest Endosc 2018.

Dougherty MK, Brenner AT, Crockett SD et al. Evaluation of Interventions Intended to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1645–1658.

Coronado GD, Petrik AF, Vollmer WM et al. Effectiveness of a Mailed Colorectal Cancer Screening Outreach Program in Community Health Clinics: The STOP CRC Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1174–1181.

Levin TR, Corley DA, Jensen CD et al. Effects of Organized Colorectal Cancer Screening on Cancer Incidence and Mortality in a Large Community-Based Population. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1383-1391.e5.

Selby K, Jensen CD, Levin TR, et al. Program Components and Results From an Organized Colorectal Cancer Screening Program Using Annual Fecal Immunochemical Testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020.

Schreuders EH, Ruco A, Rabeneck L et al. Colorectal cancer screening: a global overview of existing programmes. Gut 2015;64:1637–1649.

Hawley ST, McQueen A, Bartholomew LK et al. Preferences for colorectal cancer screening tests and screening test use in a large multispecialty primary care practice. Cancer 2012;118:2726–2734.

Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:575–582.

Mehta SJ, Induru V, Santos D et al. Effect of Sequential or Active Choice for Colorectal Cancer Screening Outreach: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1910305.

Pilonis ND, Bugajski M, Wieszczy P, et al. Participation in Competing Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Randomized Health Services Study (PICCOLINO Study). Gastroenterology 2020.

Gupta S, Sussman DA, Doubeni CA et al. Challenges and possible solutions to colorectal cancer screening for the underserved. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:dju032.

Halm EA, Beaber EF, McLerran D et al. Association Between Primary Care Visits and Colorectal Cancer Screening Outcomes in the Era of Population Health Outreach. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:1190–1197.

Doubeni CA, Selby K, Gupta S. Framework and Strategies to Eliminate Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening Outcomes. Annual review of medicine 2020;72.

Bharti B, May FP, Nodora J et al. Diagnostic colonoscopy completion after abnormal fecal immunochemical testing and quality of tests used at 8 federally qualified health centers in Southern California: opportunities for improving screening outcomes. Cancer 2019;125:4203–4209.

Issaka RB, Singh MH, Oshima SM et al. Inadequate utilization of diagnostic colonoscopy following abnormal FIT results in an integrated safety-net system. The American journal of gastroenterology 2017;112:375.

Liss DT, Brown T, Lee JY et al. Diagnostic colonoscopy following a positive fecal occult blood test in community health center patients. Cancer Causes & Control 2016;27:881–887.

Corley DA, Jensen CD, Quinn VP et al. Association Between Time to Colonoscopy After a Positive Fecal Test Result and Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Cancer Stage at Diagnosis. Jama 2017;317:1631–1641.

San Miguel Y, Demb J, Martinez ME, et al. Time to Colonoscopy After Abnormal Stool-Based Screening and Risk for Colorectal Cancer Incidence and Mortality. Gastroenterology 2021.

Selby K, Baumgartner C, Levin TR et al. Interventions to Improve Follow-up of Positive Results on Fecal Blood Tests: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:565–575.

Martin J, Halm EA, Tiro JA et al. Reasons for Lack of Diagnostic Colonoscopy After Positive Result on Fecal Immunochemical Test in a Safety-Net Health System. Am J Med 2017;130:93.e1-93.e7.

Zapka J, Taplin SH, Price RA et al. Factors in quality care–the case of follow-up to abnormal cancer screening tests–problems in the steps and interfaces of care. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2010;2010:58–71.

Zapka JM, Edwards HM, Chollette V et al. Follow-up to abnormal cancer screening tests: considering the multilevel context of care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014;23:1965–1973.

Green BB, Wang CY, Anderson ML et al. An automated intervention with stepped increases in support to increase uptake of colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:301–311.

Petrik AF, Keast E, Johnson ES et al. Development of a multivariable prediction model to identify patients unlikely to complete a colonoscopy following an abnormal FIT test in community clinics. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:1028.

Cusumano VT, Myint A, Corona E, et al. Patient Navigation After Positive Fecal Immunochemical Test Results Increases Diagnostic Colonoscopy and Highlights Multilevel Barriers to Follow-Up. Dig Dis Sci 2021.

Hardcastle JD, Armitage NC, Chamberlain J et al. Fecal occult blood screening for colorectal cancer in the general population. Results of a controlled trial. Cancer 1986;58:397–403.

Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet 1996;348:1472–1477.

Hardcastle JD, Thomas WM, Chamberlain J, et al. Randomised, controlled trial of faecal occult blood screening for colorectal cancer. Results for first 107,349 subjects. Lancet 1989;1:1160–4.

Mandel JS, Church TR, Ederer F et al. Colorectal cancer mortality: effectiveness of biennial screening for fecal occult blood. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:434–437.

Gellad ZF, Stechuchak KM, Fisher DA et al. Longitudinal adherence to fecal occult blood testing impacts colorectal cancer screening quality. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1125–1134.

Jensen CD, Corley DA, Quinn VP et al. Fecal Immunochemical Test Program Performance Over 4 Rounds of Annual Screening: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:456–463.

Murphy CC, Sen A, Watson B, et al. A Systematic Review of Repeat Fecal Occult Blood Tests for Colorectal Cancer Screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019.

Mitchell EP. Declines in Cancer Screening During COVID-19 Pandemic. J Natl Med Assoc 2020;112:563–564.

Corley DA, Sedki M, Ritzwoller DP, et al. Cancer Screening During the Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pandemic: A Perspective From the National Cancer Institute's PROSPR Consortium. Gastroenterology 2020.

Balzora S, Issaka RB, Anyane-Yeboa A et al. Impact of COVID-19 on colorectal cancer disparities and the way forward. Gastrointest Endosc 2020;92:946–950.

Wolf AM, Fontham ET, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average‐risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2018.

Levin TR, Jensen CD, Chawla NM et al. Early Screening of African Americans (45–50 Years Old) in a Fecal Immunochemical Test-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. Gastroenterology 2020;159:1695-1704.e1.

Meester RG, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, et al. Public health impact of achieving 80% colorectal cancer screening rates in the United States by 2018. Cancer 2015.

Funding

This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas under award number PP160075. The sponsor had no role in: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CCM, EAH, and AGS were involved in the study conception and design; CJ, LQ, and TZ acquired the data; all authors analyzed and interpreted the data; SY and CCM contributed to the statistical analysis; CCM drafted the manuscript; all authors contributed to the critical revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

CCM reports consulting for Freenome; AGS reports consulting for Exact Sciences and Bayer; EAH, TZ, CJ, TAM, and LQ have no conflicts to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murphy, C.C., Halm, E.A., Zaki, T. et al. Colorectal Cancer Screening and Yield in a Mailed Outreach Program in a Safety-Net Healthcare System. Dig Dis Sci 67, 4403–4409 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-07313-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-07313-7