Abstract

Field education is a core component of the Australian entry-level professional social work qualification and has long been recognized globally as offering students significant personal and professional growth and learning. However, in Australia, as in other western countries, social work courses are under pressure to find sufficient placements for increasing numbers of social work students, many of whom bring their own complexities and learning needs. Field education programs have been responding by using a range of alternative supervision models to replace the traditional one-on-one approach but there has been little attention to their impact on the learning experiences for social work students. This paper firstly describes the major field education supervision models and their effectiveness in enhancing the student experience. It then considers the literature which discusses the various factors that contribute to quality learning in field education and developing students’ professional identity. Finally, this evidence base is used to draw implications for supervisors and social work field educators in ensuring that quality and professional standards are maintained in a changing organizational, economic and political context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There have been significant changes in the higher education sector which have impacted on the delivery of social work programs in Australia and around the world. Fiscal and managerial pressures, increased student numbers, the expectations of students as fee-paying consumers of education and fierce competition between higher education providers to attract students, are all providing a constant challenge to ensure that students receive a quality learning experience. These pressures are intensified for social work programs, especially within the field education subjects, which are required to meet an increasing demand for placements as well as to ensure that quality social work supervision occurs despite a competitive and volatile health and human service sector (Bogo 2015; Crisp and Hosken 2016; Regehr 2013).

Field education programs have responded in a range of ways to find creative and innovative placement models to ensure that there are sufficient quality placements available for students, but there has been little evaluation of their impact on the students’ learning experience. Professional social work associations and accrediting bodies require qualified social workers to guide students’ learning in field education, and recognize the importance of the supervisory relationship for professional socialization of the emerging social worker and their attainment of competencies (Australian Association of Social Workers [AASW] 2012a; Council on Social Work Education [CSWE], 2015).

A range of alternative supervision models have emerged to supplement or replace the traditional one-on-one approach with little corresponding attention to their pedagogical base or evidence of quality learning experiences for students. This paper reports on some of these developments with a particular emphasis on how student supervision is undertaken. The authors draw on the findings of a recent Australian survey that highlights various models of supervision that are currently being used in the field (Zuchowski et al. 2016), and the evidence base that reports on how students learn and what they value in developing their professional identity. These insights are used to consider whether, and how, the quality of the overall learning experience for students could be compromised when alternative placement models are used. Implications are drawn for supervisors and social work field education staff with the purpose of ensuring quality education and maintaining professional standards in changing organizational, economic and political contexts.

Background

Trends in Higher Education and Human Service Organizations

Australian higher education student numbers have grown rapidly since the removal of enrolment quotas in 1986, and a demand-driven funding system has given universities an incentive to expand, with the largest increase in enrolment occurring in health-related programs (Kemp and Norton 2014). Since 2010, another 17 Bachelor and Master of Social Work programs in Australia have been accredited by the professional association which brings the total number to 91 programs across 32 universities (AASW 2017). Ten of these are Master of Social Work programs. Eleven of these are available in distance education mode and delivered by Universities that are located in regional or rural parts of Australia. The associated growth in student numbers has contributed to difficulties in ensuring that students receive the corresponding practical experience and has become a major issue for social work programs in Australia which require that students undertake a total of 1000 h of supervised field placement as part of their professional degree (AASW 2012b).

Field education is a “cooperative” endeavor between the higher education provider, the student, agency and field educator (AASW 2012b, p. 9). However, the health and welfare sector is being restructured and reformed with the emphasis of these changes focusing on economic market principles that put organizations into competition for funding with the aim of achieving lean, cost-effective services (Healy and Lonne 2010). As a result, social workers who act as field educators or practice teachers during placement are experiencing high workloads, increased accountability and less discretional powers in their everyday work which is impacting their ability to effectively support students on placement (Barton et al. 2005; Domakin 2015; Kalliath et al. 2012; Gushwa and Harriman 2018). Social workers are often asked to combine their normal work role with providing supervision to social work students, usually without any recognition of the workload implications. Findings of an Australian study highlighted that, although social work field education supervisors generally felt supported by their organizations, they indicated that staffing and workload demands impacted on their ability to provide a quality placement and that workload relief from their client responsibilities would be the best way to support them to provide student supervision (Hill et al. 2015).

A recent Australian National Field education survey of university field education staff confirmed the higher education and industry sector issues raised above. In particular, they reported increasing student enrolments and the lack of sufficient staffing and resources. University staff reported concerns about a decrease in the quality of supervision and identified that industry partners were less available to provide supervision, did not have time to attend training and were less willing or able to take on students who may present with additional needs (Zuchowski et al. 2016). Another Australian study highlighted university field coordinators’ concerns about the recruitment processes and support of external supervisors and liaison staff with many participants stating that they were worried about the quality and preparation of external supervisors and university liaison people (Zuchowski 2015b). Similar concerns about the quality of field education have been increasingly identified elsewhere over the past years (Bogo 2015; Hay et al. 2016).

Supervision Models in Social Work Field Education

The task which lies at the heart of all of field placements is to develop student competence, the formation of a professional identity, and the supervisory relationship is recognized by professional accrediting bodies and in the literature (AASW 2012a; Bogo 2015; Cleak and Smith 2012; Ben Shlomo et al. 2012). Historically, supervision in social work field education was based on an apprenticeship model, where the students followed and copied the expert social worker. The supervision styles were founded on key concepts from clinical practice which relied on the client-practitioner relationship to facilitate and support the change process (Bennet et al. 2012; Bogo 2015; Vassos and Connolly 2014). University field education staff have continued to privilege the one-to-one supervisory relationship undertaken by a qualified social worker who works in the placement agency. This model emphasizes and reinforces the idea that personal growth and development is achieved through the traditional one-to-one relationship, where role modelling, coaching, and experiential learning can occur (Cleak and Smith 2012; Cleak and Wilson 2012; Hay et al. 2016; Hicks and Maidment 2009; Hosken et al. 2016; Noble 2011). Many studies report that this relationship is key to student learning on placement and that a problematic supervisory relationship might impede their engagement with the learning (Bogo 2006; Bennet et al. 2012).

The current practice in field education, however, shows that a range of supervision models are used. For example, the respondents to an Australian field education survey reported that field placements were supported by individual supervision, group supervision, a combination of individual and group supervision, rotational based models with different supervisors, student units with an internal supervisor and student units with an external supervisor (Zuchowski et al. 2016). In a number of the larger Australian programs, approximately half of the students received external supervision (Zuchowski et al. 2016).

This paper will discuss the various supervision models by examining the literature that considers their effectiveness in enhancing the student experience. This will be followed by a summary of the research literature that outlines best supervisory practices to develop student learning on placement and finally, the best practice frameworks for field education will be used to examine the various supervision models.

Summary of the Major Alternative Models of Supervision

Various supervision models appear in the social work literature but there are four major supervisory models in field education that are consistently being used as alternatives to, or in addition to, one-to-one supervision namely: external supervision, group supervision, rotational supervision, and co-supervision.

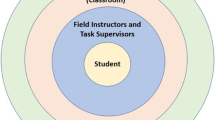

Placements with External Supervision

In the external supervision model, which is also referred to as “off-site” or the “long-arm supervision” model, the student is placed in an agency and reports to an on-site task supervisor who is an employee of the agency, and who is responsible for assigning work to the student and attending to their day-to-day learning activities (Cleak and Wilson 2012). The on-site task supervisor is often not a social worker, so the student also has an off-site, or external supervisor, who is a qualified social worker, who guides learning, helps integrate theory and classroom work and socializes the student into the profession (Maynard et al. 2015). The external supervisor, or field educator, can be a staff member at the university, someone who works in another part of the agency in which the student is placed, or a retired or private practitioner who is contracted by the social work program.

The external supervision model is often adopted by necessity, rather than by choice and has been frequently viewed less favorably by students and social work field educators (Cleak and Smith 2012). A comparison of student satisfaction with supervision and learning activities in their placements in Australia (n = 263) and Northern Ireland (n = 396) showed significant differences in satisfaction measures in relation to models of supervision with students being less satisfied when they received supervision from a long-arm supervisor, an unqualified on-site “task” supervisor who may have a qualification, but not in social work (Cleak et al. 2016; Cleak and Smith 2012).

However, there is some evidence that external supervision can offer valuable learning opportunities in emerging areas of practice (Scholar et al. 2014). A qualitative study of interviews with 15 external supervisors found that placements with external supervision can work well and offer a positive learning experience by allowing the student time away from the workplace and that their supervision is solely focused on their professional growth (Zuchowski 2015a). Thirteen students were also interviewed, and it was identified that external supervisors needed to be able to build relationships with them and the task supervisor. When these relationships worked well, students experienced a well-supported learning experience and valued the opportunity to take issues of concern outside the agency context for clarification (Zuchowski 2013). In a further study, students were surveyed about how their learning had been facilitated and supported by practice teachers. The findings showed that external supervision can deliver positive learning experiences for students, but only when there are formal partnerships in place to ensure quality outcomes (Northern Ireland Social Care Council [NISCC] 2007; Wilson et al. 2009). Placements with external supervision are strictly regulated by the NISCC which has formal partnerships with particular health and social care agencies to ensure that they provide placements with agreed quality standards (NISCC 2007). All of Northern Ireland’s practice teachers are qualified social workers and nearly all also have a post-qualifying award in practice teaching (Wilson et al. 2009), which is not a requirement in field education accreditation standards in Australia (AASW 2012a).

An evaluation of an external supervision model developed in the United Kingdom was reported by Jasper et al. (2013) based on feedback from students, on-site supervisors and external practice educators. The perceived benefits of this model included enhancing students’ understanding of multi-disciplinary perspectives and the opportunity to develop more flexible and sometimes, more self-directed, ways of working. However, this research also raised concerns about placement arrangements with external supervision including the agency’s lack of clarity and understanding of the social work role and limitations of the learning opportunities within the agency setting.

Overall, the research that has been undertaken to date on students’ perception of their learning on placements which used external supervision emphasize that these placements need to be set up and supported carefully (Maynard et al. 2015; Scholar et al. 2014).

Placements with Group Supervision

Group supervision in field education is supervision delivered to two or more students in joint sessions and can offer additional learning opportunities for student and supervisors taking on a number of students (Sussman et al. 2007). In Australia, the AASW (2012a) requires that this model of supervision can only be provided as an adjunct to individual supervision. Arkin, Freund, and Saltman (1999) describe a model of group supervision in field education that complements individual supervision, with the aim of providing students with experiences and learning in group and community work.

A number of benefits of group supervision during placement have been identified by students themselves, including peer support, learning from each other, deeper levels of learning, theory to practice integration, exploration of ethical dilemmas, and developing competence and confidence (Anand 2007; Bogo et al. 2004; Howie and MacSporran 2012). Field educators providing supervision similarly identified that group supervision could offer students advantages in peer-learning, competency in teamwork and articulating their needs, and the exploration of different theoretical orientations beneficial for the student learning experience (Sussman et al. 2007). The competence of the supervisor to facilitate the group supervision process and a comprehensive framework for the supervision are crucial elements of group supervision in field education (Arkin et al. 1999; Bogo et al. 2004; Howie and MacSporran 2012). Additionally, students might need to be matched carefully to group supervision, according to their individual stage of learning and preparedness for group supervision (Bogo et al. 2004; Howie and MacSporran 2012).

Placements with Rotational Supervision

In rotational models of supervision, the student group rotates sequentially, individually or in pairs, through two or three different service areas and different supervisors are assigned at each rotation. Rotational models of field education offer students a breadth of learning by exposing them to different practice settings and practitioners in the same organization (Regehr 2013; Vassos et al. 2018; Vassos and Connolly 2014). At the end of each rotation period, supervisors provide a handover report to the next supervisor to support the students’ learning progression through the placement. Social work student coordinators are often employed to provide additional support to students such as in offering group supervision and undertaking the mid- and final-placement assessment of individual students (Cleak and Wilson 2012).

The advantages of this model include building agency capacity to take larger numbers of students, strengthening of the partnerships between universities and communities, exposing students to new fields of practice and increasing the number of supervisors while reducing the burden on individual supervisors (Birkenmaier et al. 2012; Hosken et al. 2016).

Placements with Co-supervision

Finally, sharing supervision (co-supervision), has been presented as an effective and efficient model for supervision in field education and involves two or more social workers sharing the supervision of the student collaboratively and equally, allowing students increased access to supervision and learning through a more diverse role-modelling approach (Cleak and Smith 2012; Coulton and Krimmer 2005). Coulton and Krimmer (2005) list the key components of co-supervision in field education as mutual trust and respect and effective communication between the co-supervisors, equal commitment to the student, pre-placement contracting, reviews, common approaches to student learning, and transparency of processes. Students valued the experience of another social worker contributing to their learning, such as in shadowing their practice with clients (Cleak and Smith 2012; Cleak et al. 2016). However, Parker (2010) reported that student experiences in their study of co-supervision were mixed and there were concerns by students about supervisors colluding and students feeling they were under continued surveillance. Moreover, Parker (2010) found that there was a lack of preparation for the supervisory role by the supervisors.

Evidence Base for Positive Learning Experiences on Placement

Field placements are shaped by the unique learning opportunities presented in the agency as well as the structure and support of the supervisory relationship (Bogo 2015). This section will consider the developing evidence base that highlights the research on best practice in field placements by applying Bogo’s (2015) summary of the crucial factors that contribute to quality learning in field education as a framework for discussing them in turn. It should be noted that the social work research into the nature of teaching and learning on placement has largely been concerned with evaluating either the students’ or supervisors’ perceptions of the supervision process (Coohey et al. 2017; Fortune et al. 2001; Furness and Gilligan 2004) or the students’ perceptions of their exposure to learning opportunities and activities that promoted their social work learning on placement (Fortune and Kaye 2002; Lee and Fortune 2013a, b; Regehr et al. 2007).

The five elements summarized by Bogo (2015) are: a positive learning environment; collaborative relationships; opportunities for students to observe and debrief; multiple opportunities to actually practise; and student teaching that is based on mutual reflective dialogues, in which both the supervisor and student participate in a range of learning processes, such as linking theory to practice and coaching to enhance the learning experience. It was sometimes difficult to assign the various teaching and learning elements reported in the literature to these distinct categories as they were sometimes reported together so the best efforts were made to attribute the description that best fitted the groupings.

A Positive Learning Environment

Although there is scant research about the impact on organizations of providing field placements, Bogo (2015) suggests that students value a positive learning environment that welcomes students and views teaching and learning as beneficial to both parties. Students can bring fresh ideas, perspectives and enthusiasm (Globerman and Bogo 2003; Hay et al. 2016) and offer staff the opportunity to engage with newer theories and practices as well as validating the supervisors’ own practice (Domakin 2015; Hill et al. 2015). A significant finding from a study of student satisfaction with different supervision models in Australia indicated that students’ valued placements when the placement experience was seen as a shared responsibility between two or more social workers in the agency and other staff members offered learning opportunities as well as their primary supervisor (Cleak and Smith 2012).

Collaborative Relationships

Bogo’s (2015) second factor that reflects a quality placement includes the presence of a collaborative relationship between the student and supervisor, and one which offers strong support and encourages the student to be actively involved in their own learning. It is well recognized that students usually display high levels of stress and anxiety on placement (Coohey et al. 2017; Lefevre 2005; Wilson et al. 2009). Supervisors therefore play an influential role in providing supportive supervision and direction, including containing student anxiety, normalizing reactions to new situations and offering a collaborative learning environment that motivates students to learn (Bogo et al. 2015; Hay et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2015). Bennet et al. (2012) describe the supervisory relationship as a working agreement where a supportive supervisor provides a secure base and enables students to learn and develop a professional identity.

The literature relating to the quality of the supervisory relationship has been well documented as constituting a key influence on a student’s learning and level of satisfaction (Bennet et al. 2012; Bogo 2015; Davys and Beddoe 2015; Kanno and Koeske 2010). Kanno and Koeske’s (2010) study showed that quality supervision can generate higher student satisfaction with their placement by strongly increasing the students’ sense of empowerment and efficacy. Moreover, students reported that their learning was enhanced by a supervisory relationship that encouraged open discussion and encouraged autonomy (Knight 2001).

Social work research has highlighted that the nature of the student-supervisor relationship significantly contributed to the learning and student satisfaction with their field instructor or with their overall field experience (Fortune et al. 2001; Furness and Gilligan 2004; Lee and Fortune 2013a).

Opportunities for Students to Observe and Debrief

Davys and Beddoe (2015) reported that student observation of qualified practitioners’ work “brings into play a different set of relationships, a broader scope for observation and the excitement and challenge of accommodating greater sophistication of practice, diversity of experience and learning needs” (p. 178). Similarly, Bogo (2006) looked at field education research and summarized that students reported more satisfaction when there were more opportunities for observation; they see supervisors as more helpful, and thus perform better. Shadowing workers and practising skills and interventions has also been demonstrated to help build self-efficacy for students on placement (Parker 2006).

Research of students’ satisfaction with their placement suggests that learning is optimized when students have opportunities to observe, debrief and work with their supervisor and other experienced staff who give them contextual frameworks to connect theory and practice (Fortune et al. 2001; Fortune and Kaye 2002; Lee and Fortune 2013b).

Finally, another recent study of social work students in Northern Ireland universities (n = 396) reported that students valued regular supervision, constructive feedback about their actual practice, observing social workers, and thinking critically about the social work role highly for developing their practice competence and professional social work identity (Roulston et al. 2018).

Multiple Opportunities to Actually Practice

Fortune and Kaye (2002) outline the importance of students working independently with clients for their professional growth. In a similar vein, Csiernik’s (2001) research points to the importance of students carrying their own caseload independent of their supervisor to assist their identification as emerging social workers. Smith et al.’s (2015) study reinforces the importance of learning activities in developing a feeling of competency and social work identity. A recent study by Coohey et al. (2017) reported that learning experiences that facilitated student learning included trying out a new skill in front of the supervisor and being connected with other professionals or clients.

Student Teaching that is Based on Mutual Reflective Dialogues

Observing and practicing on its own is not sufficient for optimal learning and students need opportunities to use their learning tasks as a foundation for discussion, feedback, and analysis with their supervisors (Fortune and Kaye 2002; Fortune et al. 2001; Fortune and Lee 2004; Roulston et al. 2018). The literature also suggests that students more readily enter a dialogue about their performance and accept feedback when there is a trusting relationship between the student and supervisor, and when the supervisor is seen as knowledgeable and hence credible (Fortune and Lee 2004; Lee and Fortune 2013a).

Mutual reflective dialogue is important in developing student’s readiness for practice and can provide the evidence for that readiness for field educators. A recent study by Coohey et al. (2017) surveyed a relatively large sample (n = 149) students and found that “developmental support” was the most common behavior that facilitated their learning and that this included supervision being available and open to talk about their experience and that communication was bi-directional where students were encouraged to ask questions and to make suggestions (p. 7). Sussman et al. (2014) found that field educators considered students capacity to reflect or conceptualize practice paramount when considering for students’ readiness for entry-level practice, even if these skills required further development.

Evaluation of Alternative Supervision Models in Field Education with a Focus on the Supervisory Relationship

Social work educators have an ethical duty to ensure that students become competent social workers and, with students spending almost half of their academic hours on placement, field education programs have a heightened obligation to set good professional standards and processes. Overall, the review of the research points to the centrality of the relationship between a student and their supervisor/s to provide essential learning opportunities and to then provide the support and constructive feedback to promote learning. This endeavor requires appropriate planning, teaching and learning structures and suitable staff input, regardless of the supervisory model, so the question is whether the alternative supervisory models currently used in placements can provide the quality learning required for the development of professional skills and knowledge for an emerging social worker.

This section will now analyze the various supervision models according to some of the evidence outlined earlier that discussed the key elements that contribute to quality student learning in field education, with particular attention to the importance of the supervisory relationship as the pivotal element. External supervision is the main alternative model used in most programs in Australia and parts of the United Kingdom and has had the attention of more research scrutiny than other types of supervision and will, therefore, form the major focus of this analysis.

Placements with External Supervision

It is clear from the analysis of the research evidence that externally supervised placements have particular challenges in meeting the five key learning considerations outlined by Bogo (2015). For example, the existing research, as well as the professional accreditation bodies (AASW 2012a; NISCC 2007), emphasize that students need to observe and be observed and then receive constructive feedback from a trustworthy source (Davys and Beddoe 2015). This is a major disadvantage of the external supervision model as the qualified social worker is off-site and cannot have their practice observed or have a student’s practice directly observed, and this remains a major drawback of the model, despite its widespread adoption by social work programs. It has been reported that, apart from the required three direct observations, off-site or external practice teachers in Northern Ireland were not in a position to routinely observe the work of students and had to rely on written evidence and evaluations as a vehicle for teaching and learning within the supervision process (Wilson et al. 2009). This was also raised as a concern in another Australian study where a number of external supervisors noted that not having visual observations of their students made supervision tricky and meant that they had to rely on what the student and the agency told them (Zuchowski 2015a). More alarmingly, though, was feedback from task supervisors that many of them had no relationship with the external supervisor at all (Zuchowski 2014) which may limit their ability to provide specific feedback about students’ learning and emerging practice from their direct observations.

A number of studies indicated that identifying and modelling the role of social work is a core feature of field education practice, but the absence of a qualified social worker is usually the norm in placements using external supervision and students can be challenged by the external supervisor’s lack of contextual understanding of the agency and differing ideas between supervisors (Zuchowski 2013). Jasper et al. (2013) reported that this issue was so concerning that the current criteria for a final placement in the UK now state that, in order to support the development of professional identity, students “should not be the sole social work representative in a setting” (The College of Social Work [TCSW] 2012, p. 3). In an Australian study which asked field educators how they constructed preparedness for practice, an emphasis was given to the importance of new graduates being clear about social work values, and about the purpose and role of social work (Yu et al. 2016). Some of this can be achieved through purposeful and targeted supervision sessions with the external supervisor; however, students can be kept wondering whether what is modelled to them in practice is actually modelling social work (Zuchowski 2013).

Much of the supervisory relationship facilitates feedback about professional practice and what it is like to be a professional social worker. In placement models where the supervisor is not on-site, how this feedback is given or received can make a difference to the quality of student learning. A recent study of a large sample of social work students in Northern Ireland showed that students in settings with no social work presence missed important opportunities to listen and observe the role of social work and they reported that observing was not useful. They suggested that additional opportunities to observe social workers would have helped to define their understanding of the professional social work role (Roulston et al. 2018). Communication, role clarity and collaboration would need to be key aspects of placements with external supervision. Here the supervisory relationship extends beyond the one-to-one relationship to a supervisory triad (Henderson 2010). This triad relationship between field educators, task supervisors and students in placements with external supervision requires extra support and coordination (Abram et al. 2000; Henderson 2010).

Moreover, considering that a collaborative relationship is the basis for quality supervision as an essential part of quality field education (Bogo 2015), power dynamics need to be explored and roles discussed so that the triad relationship can offer strong support and encourage the student to be actively involved in their own learning. However, in an Australian national field education survey undertaken by the authors (Zuchowski et al. 2016), it was identified that 13 of the 17 field education programs which responded to the survey questions needed to use relatively inexperienced staff with time-limited contracts to undertake the external supervision role; one program used inexperienced staff for more than 50 students; and two programs for at least 11 students in 2015. Using newly appointed staff would limit their capacity to complete the relationship building and collaborating tasks that have been identified as important (Zuchowski et al. 2016). University staff were concerned about the impact of this on the quality of the field education learning experience (Zuchowski et al. 2016).

Finally, while some research highlights extra opportunities “…to practise direct and creative forms of social work…” in placements with external supervision (Scholar et al. 2014, p 1007), equally, placements with external supervision could limit students’ ability to practice social work. The experience of placing students in a non-traditional setting, namely Police Public Protection Investigation Units in the Northwest of England where there was no on-site social work supervision, indicated that a significant part of the placement involved just shadowing and joint working with police officers, overall resulting in insufficient social work practice experience for student learning. As a result, two-thirds of the students had additional learning opportunities negotiated for them, such as shadowing periods or attachments to Local Authority Children’s and Adults Services because students ‘were unable to meet their Key Roles’ requirements in the non-traditional setting alone (Jasper et al. 2013, p15). Cleak et al. (2016) also found that first-year students with an unqualified on-site facilitator had fewer opportunities to work directly with social workers or to practice in a social work role.

In summary, there are a number of aspects in the learning experience in field education models with external supervision that can impede the students’ learning experience to be observed in their practice by a social worker and observe a social worker in their practice. Observation and collaborative relationships are two of the key points highlighted by Bogo (2015) contributing to quality learning in field education. Additionally, a positive learning environment is also seen as desirable, and an agency with no on-site social workers may lack clarity and understanding of the social work role (Jasper et al. 2013). Close collaboration of the key players in placements with external supervision can alleviate some of the impacts, and the potential benefits of external supervision can still ensure that students have a positive learning experience. However, most crucially, placement success relies on close collaboration between the student, the supervisors and the liaison person as well as ensuring that the contextual setting of the placement is appropriate to the students’ learning needs and included required placement support (Henderson 2010; Zuchowski 2013, 2015a, 2016). In the current climate of limited resources, the concern is that less attention will be made to the careful and systematic establishment of these supervision models.

Placements with Rotational Supervision

Scarce research examines placements with rotational supervision. The key aspect contributing to student learning that can be explored with the available literature is how the presence of a strong collaborative relationship (Bogo 2015) is impacted. Although field education programs using rotational supervision models are less common, there are questions about how well the supervisor relationship can guide the learning. The model requires an extension of the one-on-one relationship, the building of trust and the establishment of good processes for collaboration and communication (Hosken et al. 2016; Vassos et al. 2018).

However, students’ and supervisors’ experience of the rotational model shows that building supervisory relationships can be difficult as it necessitates the building and earning of trust with multiple supervisors (Vassos and Connolly 2014; Vassos et al. 2018). Again, as with placements with external supervision, effort needs to be put into building collaborative relationships. It appears that when more parties are involved this becomes more complex and needs special attention. In evaluating the value of the rotational supervision models by surveying and running focus groups with small numbers of students, supervisors and liaison staff, Hosken et al. (2016) recommend a strengthened university liaison role to facilitate student learning through negotiating the learning difficulties that might arise due to the complexities of structures, intersecting power dynamics, and multiple learning and supervisory relationships.

Vassos and Connolly (2014) observed that students who are largely self-directed learners and who are orientated toward action and change are more likely to enjoy the experience; whereas students who are more reflective learners and want to fully engage with the supervisory relationship found the pace of the rotational placement challenging. For some students, needing to build new relationships after feeling comfortable in the one they had just built felt challenging (Hosken et al. 2016). In summary, rotational models of supervision in field education can work, but the emphasis needs to be on the collaborative relationships (Bogo 2015). While the language of triad relationship has not been used in rotational models, it might be advantageous to do so to ensure that the complexities that arise due to the multiple learning and supervisory relationships (Hosken et al. 2016) are explored and considered in the learning experience.

Co-supervision

Findings from the limited studies of the co-supervision model showed high levels of student satisfaction could be expected because of the presence of the learning elements indicated by Bogo (2015). Available research evidence suggests that co-supervision provide opportunities for students to observe and debrief and have opportunities to practice social work (Bogo 2015). Students in placements with co-supervision felt supported and had multiple opportunities to observe and shadow more than one worker as well as to practise in different settings (Cleak and Smith 2012). Another study, of 396 social work students, confirms the teaching and learning benefits of sharing responsibility for providing learning opportunities for students. Although students indicated that all staff contributed to their learning journey, one-third of the cohort indicated that it was “other social workers within the team” who most frequently assisted with significant learning tasks (Cleak et al. 2016). This supervision model could offer a feasible alternative for agencies wanting to offer a practice learning experience within the climate of a pressurized work environment, but conversely, it ties up two or more qualified supervisors and hence is not so attractive to field education programs. Again, careful attention to relationship dynamics and issues of power and communication is needed.

Group Supervision

Although this model has some perceived learning advantages, this form of supervision can only be used as ancillary to an on-site or external supervision approach, in recognition of the fact that students need individual time with their supervisor. There is also scant evidence of its ability to enhance the learning experience of the student according to the five domains outlined by Bogo (2015). One study compared individual and group supervision received by social work students in Israel over two consecutive years (Zeira and Schiff 2010). Students’ satisfaction with their learning were compared in four areas: evaluation of their interventions with clients, internalization of professional values, evaluation of their field instructors, and general satisfaction with field instructor and field practice. Significant differences were found in the last two, specifically in their perception of the content of the supervision and of the students’ relationships with their supervisors. The authors concluded that tracking parallel processes in group supervision may be difficult because not all group members experience or feel processes in the same way and students may expect that their professional development and growth is enhanced in a one-on-one setting.

Ensuring the Right Match

One of the mitigating factors to ensure that placements with alternative models are suitable for the growth of professional social work graduates is to look at the individual characteristics of students and their ability to thrive in field education. A number of the studies commented that the importance and usefulness of the supervisory relationship were sometimes dependent on aspects of the students themselves. A small study of supervisors found that students who were mature, self-confident and took initiative, were satisfied with external supervision (Abram et al. 2000) and other research, such as that into the rotational model, also indicated that the characteristics of the student can influence the success of the placement model (Coohey et al. 2017; Vassos and Connolly 2014). Similarly, Fortune et al. (2001) and Cleak et al. 2016) found that there are differences in students’ satisfaction with various learning activities depending on their year level; this might be related to students’ levels of maturity and need for structure. Overall, it seems individual matching of students to learning opportunities is an important process to consider.

Conclusion

Alternative placement models may offer some quality learning, but they add complexities and considerations when the one-on-one supervisory relationship is replaced with a model that includes more players and multiple relationships (Hanlen 2011). In particular, some of the studies of student satisfaction with external supervision voiced that the lack of contextual knowledge by the external supervisor was challenging, highlighting the lack of insight into the organization and the field of practice as impacting on their placement, supervision and assessment of their practice (Jasper et al. 2013; Maidment and Woodwood 2002; Zuchowski 2013).

Quality supervision can be present or absent in field education with any of the placement models and, historically, the alternative models have been set up as a last resort and to meet a shortfall in the number of traditional placements and are often established with minimal attention to the processes of building the supervisory relationship. The review of the different models suggests that setting up the placement with clear learning activities, structures and the establishment and maintenance of relationships between all key players could mitigate some of the shortcomings of the external supervision model. However, these endeavors are costly and with the current pressure to set up placements to alleviate shortages, it is difficult to imagine that field education programs have the time and resources to ensure that this occurs. Furthermore, although the research has suggested that the liaison role could play a pivotal role in these models, two recent studies of Australian field education programs reported that significant numbers of these programs contracted social workers external to the universities to provide this role with minimum hours allocated to them and many of them were new to these positions (Cleak and Venville 2018; Zuchowski et al. 2016).

Recommendations of the CSWE Summit on Field Education suggested that, as programs cultivate new placements, it would be helpful for them to develop explicit guidelines that clearly define and outline their expectations and processes through a list of specific qualities that need to be present (CSWE 2015). This review of the literature offers important messages in regard to how alternative placement models need to be structured and supported. For example, a number of studies indicated that students need a sense of self-efficacy to develop confidence in their professional preparation and that observation of supervisors and being observed in their own practice is key to developing that confidence (Bogo 2006; Parker 2006). Thus, if alternative placement models lack opportunities for observation, social work educators need to structure opportunities for observation, or clearly identify how alternative supervision could be strengthening through the use of additional teaching tools. This could be achieved, for instance, by using a range of live and technological opportunities, such as simulations (Regehr 2013) or implementing a student observation tool which requires field educators to directly observe and assess student practice (Hay et al. 2016).

In conclusion, the evidence presented in this paper suggests that, while field education programs continue to “retrofit” agency sites to make them work, especially in the absence of experienced, on-site supervisors (Gushwa and Harriman 2018), quality learning for students’ on placement may be compromised.

References

Abram, F. Y., Hartung, M. R., & Wernet, S. P. (2000). The non-MSW task supervisor, MSW field instructor, and the practicum student. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 20(1), 171–185.

Anand, J. C. (2007). Social work student units: A case study in group learning and supervision. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education. 9 (1), 6–15.

Arkin, N., Freund, A., & Saltman, I. (1999). A group supervision model for broadening multiple-method skills of social work students. Social Work Education, 18(1), 49–58.

Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW). (2012a). Australian social work education and accreditation standards (ASWEAS) 2012. In 1.2: Guidance on field education programs (pp. 1–69). Canberra: AASW.

Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW). (2012b). Australian social work education and accreditation standards (ASWEAS) 2012 (Vo1. 2(1), pp. 1–27). Canberra: AASW.

Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW). (2017). AASW accredited courses. Canberra, ACT: AASW. Retrieved from https://www.aasw.asn.au/careers-study/accredited-courses.

Barton, H., Bell, K., & Bowles, W. (2005). Help or hindrance? Outcomes of social work student placements. Australian Social Work, 58(3), 301–312.

Ben Shlomo, S., Levy, D., & Itzhaky, H. (2012). Development of professional identity among social work students: Contributing factors. The Clinical Supervisor, 31(2), 240–255.

Bennet, S., Mohr, J., Deal, K. H., & Hwang, J. (2012). Supervisor attachment, supervisory working alliance, and affect in social work field instruction. Research on Social Work Practice, 23(2), 199–209.

Birkenmaier, J., Curley, J., & Rowan, N. L. (2012). Knowledge outcomes within rotational models of social work field education. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 55(4), 321–336.

Bogo, M. (2006). Field instruction in social work. The Clinical Supervisor, 24(1–2), 163–193.

Bogo, M. (2015). Field education for clinical social work practice: Best practices and contemporary challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(3), 317–324.

Bogo, M., Globerman, J., & Sussman, T. (2004). Field instructor competence in group supervision. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 24(1–2), 199–216.

Bogo, M., Lee, B., McKee, E., Baird, S., & Ramjattan, R. (2015). Field instructors’ perceptions of foundation year students’ readiness to engage in field education. Social Work Education, 35(2), 204–214.

Cleak, H., Roulson, A., & Vreugdenhil, A. (2016). The inside story: A survey of social work students’ supervision and learning opportunities on placement. British Journal of Social Work, 46(7), 2033–2050.

Cleak, H., & Smith, D. (2012). Student satisfaction with models of field placement supervision. Australian Social Work, 65(2), 243–258.

Cleak, H., & Venville, A. (2018). Testing satisfaction with a group-based social work field liaison model: A controlled mixed methods study. Australia Social Work, 71(1), 32–45.

Cleak, H., & Wilson, J. (2012). Making the most of field placement (3rd edn.). South Melbourne: Cengage Learning Australia.

Coohey, C., Dickinson, R., & French, L. (2017). Student self-report of core field instructor behaviors that facilitate their learning. The Field Educator, 7(1), 1–15.

Coulton, P., & Krimmer, L. (2005). Co-supervision of social work students: A model for meeting the future needs of the profession. Australian Social Work, 58, 154–166.

Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). (2015). Educational policy and accreditation standards for baccalaureate and master’s social work programs. Retrieved from https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/Accreditation/Accreditation-Process/2015-EPAS/2015EPAS_Web_FINAL.pdf.aspx.

Crisp, B. R., & Hosken, N. (2016). A fundamental rethink of practice learning in social work education. Social Work Education, 35(5), 506–517.

Csiernik, R. (2001). The practice of field work: What social work students actually do in the field. Canadian Social Work, 3(2), 9–20.

Davys, A., & Beddoe, L. (2015). “Going live”: A negotiated collaborative model for live observation of practice. Practice: Social Work in Action, 27(3), 177–196.

Domakin, A. (2015). The importance of practice learning in social work: Do we practice what we preach? Social Work Education, 34(4), 399–413.

Fortune, A. E., & Kaye, L. (2002). Learning opportunities in field practica: Identifying skills and activities associated with MSW students’ self-evaluation of performance and satisfaction. The Clinical Supervisor, 21(1), 5–28.

Fortune, A. E., & Lee, M. (2004). Student’s access to educational learning activities and learning outcomes in field education. Paper presented at the Eighth Annual Conference of the Society for Social Work and Research, New Orleans, LA.

Fortune, A. E., McCarthy, M., & Abramson, J. S. (2001). Student learning processes in field education: Relationship of learning activities to quality of field instruction, satisfaction, and performance among MSW students. Journal of Social Work Education, 37(1), 111–124.

Furness, S., & Gilligan, P. (2004). Fit for purpose: Issues from practice placements, practice teaching and the assessment of students’ practice. Social Work Education, 23(4), 465–479.

Globerman, J., & Bogo, M. (2003). Changing times: Understanding social workers’ motivation to be field instructors. Social Work, 48(1), 65–73.

Gushwa, M., & Harriman, K. (2018). Paddling against the tide: Contemporary challenges in field education. Clinical Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0668-3.

Hanlen, P. (2011). Community engagement: managers’ viewpoints. In C. Noble & M. Hendrickson (Eds.), Social work field education and supervision across Asia Pacific (pp. 221–241). Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Hay, K., Dale, M., & Yeung, P. (2016). Influencing the future generation of social workers’: Field educator perspectives on social work field education. Advances in Social Work Education, 18(1), 39–54.

Healy, K., & Lonne, R. (2010). The social work & human services workforce: Report from a national study of education, training and workforce needs. Australia: Australian Council of Leaning and Teaching.

Henderson, K. J. (2010). Work-based supervisors: The neglected partners in practice learning. Social Work Education, 29(5), 490–502.

Hicks, H., & Maidment, J. (2009). Fieldwork practice in social work. In M. Connolly & L. Harms (Eds.), Social work: Contexts and practice (pp. 423–436). South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Hill, N., Egan, R., Cleak, H., Laughton, J., & Erwin, L. (2015, September). The sustainability of social work placements in a shifting landscape. Conference paper presented at the International Conference on Discovery and Innovation in Social Work Practicum Education, Hong Kong.

Hosken, N., Green, L., Laughton, J., Ingen, R. V., Walker, F., Goldingay, S., & Vassos, S. (2016). A rotational social work field placement model in regional health. Advances in Social Work & Welfare Education, 18(1), 72–87.

Howie, J., & MacSporran, J. (2012). Engaging students in practice learning through a model of group supervision. The Journal of Practice Teaching and Learning, 10(1), 27–44.

Jasper, C., Munro, L., Black, P., & McLaughlin, H. (2013). Is there a future for the use of non-traditional placement settings for final year social work students? Journal of Practice Teaching & Learning, 12(2), 5–25.

Kalliath, P., Hughes, M., & Newcombe, P. (2012). When work and family are in conflict: Impact on psychological strain experienced by social workers in Australia. Australian Social Work, 65(3), 355–371.

Kanno, H., & Koeske, G. (2010). MSW students’ satisfaction with their field placements: The role of preparedness and supervision quality. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(l), 23–38.

Kemp, D., & Norton, A. (2014). Review of the demand driven funding system. Report for the Department of Education and Training. April, 2014.

Knight, C. (2001). The process of field instruction: BSW and MSW students’ views of effective field supervision. Journal of Social Work Education, 37(2), 357–380.

Lee, M., & Fortune, A. (2013a). Do we need more “doing” activities or “thinking” activities in the field practicum? Journal of Social Work Education, 49(4), 646–660.

Lee, M., & Fortune, A. (2013b). Patterns of field learning activities and their relation to learning outcome. Journal of Social Work Education, 49(3), 420–438.

Lefevre, M. (2005). Facilitating practice learning assessment: The influence of relationship. Social Work Education, 24(5), 565–583.

Lizzio, A., Stokes, L., & Wilson, K. (2005). Approaches to learning in professional supervision: Supervisee perceptions of processes and outcome. Studies in Continuing Education, 27(3), 239–256.

Maidment, J., & Woodward, P. (2002). Student supervision in context: A model for external supervision. In S. Shardlow & M. Doel (Eds.), Learning to practice: International approaches. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing.

Maynard, S., Mertz, L., & Fortune, A. (2015). Off-site supervision in social work education: What makes it work? Journal of Social Work Education, 51(3), 519–534.

Noble, C. (2011). Field education: Supervision, curricula and teaching methods. In C. Noble & M. Henrickson (Eds.), Social work field education and supervision across Asia Pacific (pp. 3–22). Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Northern Ireland Social Care Council. (2007). NISCC designated practice learning scheme. Belfast: Northern Ireland Social Care Council.

Parker, J. (2006). Developing perceptions of competence during practice learning. British Journal of Social Work, 36, 1017–1036.

Parker, J. (2010). When things go wrong! Placement disruption and termination: Power and student perspectives. British Journal of Social Work, 40(3), 983–999.

Regehr, C. (2013). Trends in higher education in Canada and implications for social work education. Social Work Education, 32(6), 700–714.

Regehr, G., Bogo, M., Regehr, C., & Power, R. (2007). Can we build a better mousetrap? Improving measures of social work practice performance in the field. Journal of Social Work Education, 43(2), 327–343.

Roulston, A., Cleak, H., & Vreugdenhil, A. (2018). Promoting readiness to practice: Which learning activities promote competence and professional identity for student social workers during practice learning? Journal of Social Work Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1336140.

Scholar, H., McLaughlin, H., McCaughan, S., & Coleman, A. (2014). Learning to be a social worker in a non-traditional placement: Critical reflections on social work, professional identity and social work education in England. Social Work Education, 33(8), 998–1016.

Smith, D., Cleak, H., & Vreugdenhil, A. (2015). “What are they really doing?” An exploration of student learning activities in field placement. Australian Social Work, 68(4), 515–531.

Sussman, T., Bailey, S., Richardson, B., S., & Granner, F. (2014). How field instructors judge BSW student readiness for entry-level practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 50, 84–100.

Sussman, T., Bogo, M., & Globerman, J. (2007). Field instructor perceptions in group supervision. The Clinical Supervisor, 26(1–2), 61–80.

The College of Social Work. (2012). Practice learning guidance: Placement criteria (edref9). London: TCSW. Retrieved from http://www.collegeofsocialwork.org/resources/reform-resources/.

Vassos, S., & Connolly, M. (2014). Team-based rotation in social work field education: An alternative way of preparing students for practice in statutory child welfare services. Communities, Children and Families Australia, 8(1), 49–66.

Vassos, S., Harms, L., & Rose, D. (2018). Supervision and social work students: Relationships in a team-based rotation placement model. Social Work Education, 37(3), 328–341.

Wilson, G., O’Connor, E., Walsh, T., & Kirby, M. (2009). Reflections on practice learning in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland: Lessons from student experiences. Social Work Education: The International Journal, 28(6), 631–645.

Yu, N., Moulding, N., Buchanan, F., & Hand, T. (2016). How good is good enough? Exploring social workers’ conceptions of preparedness for practice. Social Work Education, 35(4), 414–429.

Zeira, A., & Schiff, M. (2010). Testing group supervision in fieldwork training for social work students. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(4), 427–434.

Zuchowski, I. (2013). From being “caught in the middle of a war” to being “in a really safe space”: Social work field education with external supervision. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 15(1), 104–119.

Zuchowski, I. (2014). Planting the seeds for someone else’s discussion: Experiences of task supervisors supporting social work placements. The Journal of Practice Teaching and Learning, 13(3), 5–23.

Zuchowski, I. (2015a). Field education with external supervision: Supporting student learning. Field Educator, 5(2), 1–17.

Zuchowski, I. (2015b). Being the university: Liaison persons’ reflections on placements with off-site supervision. Social Work Education, 34(3), 301–314.

Zuchowski, I. (2016). Getting to know the context: The complexities of providing off-site supervision in social work practice learning. British Journal of Social Work, 46(2), 409–426.

Zuchowski, I., Cleak, H., Nickson, A., & Spencer, A. (2016). Preliminary results from a national survey of Australian social work field education programs. Paper presented at the 2016 ANSZWWER Symposium, Advancing our Critical Edge in Social Welfare Education, Research and Practice, Townsville, James Cook University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cleak, H., Zuchowski, I. Empirical Support and Considerations for Social Work Supervision of Students in Alternative Placement Models. Clin Soc Work J 47, 32–42 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0692-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0692-3