Abstract

Counterfeit goods fraud is stated to be one of the fastest growing businesses in the world. Academic work examining the flows of counterfeit goods is beginning to build momentum. However, work analysing the financial mechanisms that enable the trade has been less forthcoming. This is despite the fact that over the last two decades official and media discourses have paid increasing attention to ‘organised crime’ finances in general. Based on an exploratory study that brought together academic researchers and law enforcement practitioners from the UK’s National Trading Standards, the aim of the current article is to offer an account of the financial management in the counterfeit goods trade. Focusing on tangible goods, the article addresses the ways in which capital is secured to allow counterfeiting businesses to be initiated and sustained, how entrepreneurs and customers settle payments, and how profits from the business are spent and invested. The study covers the UK in the broader context of what is a distinctly transnational trade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The trade in counterfeit goods is stated to be one of the fastest growing businesses in the world. According to the World Economic Forum (2015: 3) “counterfeiting and piracy […] cost the global economy an estimated $1.77 trillion in 2015, which is nearly 10% of the global trade in merchandise”. Similarly, the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) (2011:1) suggests that the counterfeiting of goods is a form of fraud that “creates enormous drain on the global economy, crowding out billions in legitimate economic activity and facilitating an “underground economy” that deprives government of revenues for vital public services, forces higher burdens on tax payers, dislocates hundreds of thousands of legitimate jobs and exposes consumers to dangerous and ineffective products”.

A Home Office study (Mills et al. 2013), estimated the scale of counterfeiting in the UK at £90 million per annum, an estimate which has been calculated on the basis of seizure data. The social and economic costs of counterfeiting (estimates of lost revenue to legitimate business, lost revenue to the exchequer, lost jobs and enforcement costs, including Criminal Justice System costs) were estimated at £400 million per annum (Mills et al. 2013). Indeed, it is considerably difficult to accurately measure the size and impact of the global trade in counterfeit goods. The trends that can be discerned must be contextualised as associated with a number of variables, such as the level of intensity of law enforcement or resolution of various governments.

Counterfeiting takes place in a number of dimensions, which include deceptive and non-deceptive counterfeits (see Camerini et al. 2014), and high and low-quality fakes. The level of imitation and intellectual property (IP) infringement can vary from the use of fraudulent names and logos that resemble a brand to the unauthorised sale of a legitimately produced designer product. The scope of product counterfeiting spans the globe and covers virtually every type of product. Statistics on seizures suggest burgeoning markets in ‘non-safety critical’ goods, such as counterfeit fashion items (Wall and Large 2010; Large 2015), watches and jewellery, and CDs/DVDs (Antonopoulos et al. 2011) as well as in products that can pose a significant risk to consumers’ health and safety, such as food, alcohol (see Lord et al. 2017; Shen and Antonopoulos 2016; Shen 2018), tobacco (Shen et al. 2010), cosmetics, medicines and medical devices (Hall and Antonopoulos 2016), pesticides, products in the defence/military supply chain (Sullivan and Wilson 2016), electrical equipment and appliances and car and aeroplane parts (Yar 2005). Recent cases highlighting the size and dynamics of the trade in harmful, ‘safety-critical’, counterfeit goods include hundreds of counterfeit aircraft microchips identified in the US defense supply chain, 45% of road fatalities in Oman attributed to counterfeit spare parts in 2012 alone (Interpol 2014; Antonopoulos and Papanicolaou 2018), and estimates claiming that the trade in counterfeit, falsified and substandard medicines has overtaken marijuana and prostitution to become the largest illicit market in the world (IRACM 2013; Hall and Antonopoulos 2016).

Academic work examining the flows of counterfeit goods is beginning to build momentum. However, work analysing the financial mechanisms that enable the trade has been less forthcoming. This is despite the fact that over the last two decades official and media discourses have paid increasing attention to ‘organised crime’ finances in general. In the main, these accounts portray crime-money as a corruptive force, a threat to social life and the stability of national and global financial systems (for a critique see van Duyne and Levi 2005; Reuter 2013). In the UK alone, the Home Office (2007) estimates the annual revenue derived from organised crime at more than £11 billion, while the attendant economic and social costs are close to £25 billion. However, despite the fact that asset recovery has become a priority for policy-makers and law enforcement agencies internationally (Levi and Osofsky 1995; Brown et al. 2012; FATF 2012), research on the financial management in illegal markets and other manifestations of ‘organised crime’ is limited, with the drug market in specific contexts being perhaps the exception (see Reuter et al. 1990; Naylor 2004; Brå 2007). There is a relatively sound understanding of finance-related issues in the drug markets, with an emphasis on prices, costs of doing business (Caulkins et al. 1999; Moeller 2012), investments and money laundering. However, not much is known about other illegal markets (cf. Reuter 1985; Moneyval 2005; Korsell et al. 2011; Petrunov 2011; Soudijn and Zhang 2013) apart from useful estimations of their proceeds (see Savona and Calderoni 2014). Two exceptions are the FINOCA 1 and FINOCA 2 projects (CSD 2015, 2018), which focused on the financial management of the illegal tobacco trade, cocaine market, VAT fraud and human trafficking across European member states.

Moreover, although considerable financial analysis of organised crime has been conducted on the disposal of the proceeds of crime and the financing of terrorism (e.g. Levi 2010a; Silke 2000), little has been done in terms of analysing or targeting individuals, structures and processes that are involved in the ‘preceeds’ of crime (Levi 2010b; see also Kruisbergen et al. 2012). Indeed, as the Head of Europol’s Financial Intelligence unit noted in an event held at the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice in 2015, “very little is known about the financial management of organised crime…” (Navarrete 2015). This is surprising given the fact that financing “is a horizontal issue for all criminal markets” (Hicks 2015: 1).

This article builds on the findings from a UK-based project investigating financial management in the counterfeit goods trade. Focusing on tangible goods, it addresses the ways in which capital is secured to allow counterfeiting businesses to be initiated and sustained, how entrepreneurs and customers settle payments, and how profits from the business are spent and invested. The study covers the UK in the broader context of what is a distinctly transnational trade. To map the main physical and financial flows in counterfeit markets, the article focuses on trade with China. Not only is China a dominant manufacturing force in the global economy with an advanced export infrastructure, it is also the major global source of counterfeits (Intellectual Property Office and Foreign and Commonwealth Office 2015; Chaudhry 2017). Evidence suggests an identification between the countries that tend to be reported as receptive markets for counterfeit products and China’s top legal trading partners, which includes the UK (see Shen et al. 2012; OECD/EUIPO 2017).

Following this introduction, the article outlines an overview of the methods used and data collected. It then offers an account of the nature of the counterfeiting business, and an examination of the financial aspects of the trade in counterfeit goods. Its final section provides discussion and concluding remarks.

Methods and data

The research took place in two phases, which allowed the project to develop iteratively. The first phase was desk-based and focused on providing the research team with a better understanding of the complex business models associated with the trade in counterfeit products. Alongside the relatively small body of published academic literature, the review included research reports by academics, research institutes, governments, national and international law enforcement agencies as well as reports by professional associations and private companies that have been either affected by specific types of counterfeiting (e.g. British American Tobacco) or commissioned by a client to conduct research on a specific market (e.g. KPMG). Open sources also included media sources; of particular relevance here were press releases from law enforcement agencies.

Counterfeiting-related information and statistics in the Chinese literature were obtained from the CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) — the largest academic database in the Chinese language. This allowed an initial examination of UK–China interconnections in the counterfeit trade. In addition to CNKI, google and baidu (the most popular Chinese search engine) were searched by using keywords in Chinese for ‘counterfeit goods’ (jia-mao-chan-pin), ‘counterfeit and inferior (goods)’ (jia-mao-wei-lie), ‘combatting product counterfeiting’ (da-ji-jia-mao) and their variations to capture all relevant cases, examples and statistics scattered in open sources. A systematic search of UK and Chinese media databases for stories relating to counterfeiting between 1987 and 2017 provided useful contextual information.

The second phase of the study involved in-depth interviews carried out in the UK with law enforcement and other government officials, academics and researchers, criminal entrepreneurs, legitimate entrepreneurs and other knowledgeable actors. For this phase of the study, participants were identified in four ways. First, during the course of the literature review and media research, specific officials from law enforcement agencies who appeared in reports or media accounts were approached. Second, potential participants — both officials and criminal entrepreneurs — had already been identified from previous research studies that members of the team have conducted on various manifestations of ‘organised crime’ including counterfeiting. In essence, snowball sampling was used as many of our initial participants introduced us to other potential participants. One of the advantages of this method of sampling is the relatively informal way of identifying participants from hard-to-reach populations, such as illegal entrepreneurs (Atkinson and Flint 2004). Third, participants — primarily from the law enforcement side — were suggested by research partners at the National Trading Standards eCrime Team, who effectively operated as our ‘gatekeepers’. Fourth, researchers identified interviewees with expert knowledge during relevant conferences and events on counterfeiting and illicit financing in the UK and Europe.

A total of 31 interviews with knowledgeable actors were conducted. During this phase of the study, the research team’s main objective was to develop a sample that could provide informed and detailed accounts of the financial aspects of counterfeiting. In line with the nature of qualitative interviewing, which values flexibility, slightly different topic guides for the two main groups of participants (‘experts’ and ‘criminal entrepreneurs’) were devised. The loose structure ensured relevant topics were covered, whilst allowing researchers to adapt questioning accordingly for individual participants. Core interview themes included: general business characteristics, starting up, payments, profits, sourcing and financial factors and decisions. Experts interviewed were also asked about their institutional and professional background and types of cases related to counterfeit products trading that their institutions handle. To provide richer context, this phase of the research also involved qualitative observations across a number of research sites. The research team visited and conducted observations at counterfeit product markets in Manchester’s Cheetham Hill (Strangeways) area and busy tourist destinations in Spain and across Vietnam and China. Some of these locations are well-known for their counterfeit markets, such as Barcelona and the Chinese city of Yiwu, a city referred to as the ‘counterfeit capital of China’ (Fleming 2014).

Transcripts and fieldnotes derived from the interviews and observations, as well as information obtained from the open sources, were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006). This approach involved open coding, clustering and theme formation. After familiarising ourselves with the available data, an initial coding framework was developed. Findings were compared and the initial coding framework was refined to its final version through discussion and consensus. The final coding framework comprising the main themes was approved by all members of the research team. Naturally, themes were induced from the information the participants disclosed. The ‘interview-data-as-a-resource’ tradition was used to reflect the interviewees’ reality about the topic (Seale 1998). The final framework was applied to all data, and the contents of each transcript as well as the notes taken in the field were coded under the appropriate themes. Data were inserted into an Excel spreadsheet providing a visual summary of the dataset that enabled authors to identify patterns. Finally, powerful and vivid extract examples from the data were selected to highlight accounts put forward. In this article, we use pseudonyms for specific participants (e.g. entrepreneurs ‘Dave’ and ‘John’).

The methodological approach outlined above sought to gather rich data to examine a previously under-researched aspect of the phenomenon of counterfeiting (Yin 2009). The interviews, in particular, provided an important insight, which would not be possible to glean from quantitative methods. Therefore, the focus was to seek a purposeful sample, which recognised the views and opinions of different relevant actors and their subjective accounts to provide authentic ‘voices’ on the issue. However, the researchers are especially mindful that official data including data derived from interviews with members of the authorities is the result of law enforcement activity, which in turn depends upon resource restrictions, the competency of agents, organisational priorities, and wider political priorities (Levi 2004). Similarly, as reflected upon by almost all researchers who have conducted interviews with ‘organised criminals’, such interviews have potential for limitations. In addition to attempts to ‘cross-check’ and ‘member-check’, in common with other qualitative research on topics related to ‘organised crime’, developing ‘trust’ with criminal entrepreneurs was essential for seeking truthful and credible accounts (Ellis and MacGaffey 1996; Titeca 2019). This was in part enabled by the research team’s existing contacts, relationships and networks in the field; however, at the same time, this risks limiting the sample to the researchers’ own personal network and, as a consequence, possibly the scope of the findings (Hobbs and Antonopoulos 2014).

Moreover, although media sources are used as sources of technical information about manifestations of ‘organised crime’, they should be treated very cautiously for a variety of reasons (see Shen and Antonopoulos 2016). Not only do they most often refer to those cases which the authorities came across, thus ignoring cases of successful (non-apprehended) ‘organised criminals’ and/or uninterrupted schemes, but they also tend to present the issues relating to the actors of ‘organised crime’ or the activity/market itself in a sensational and morally charged manner; something that has limited analytical value. Sources retrieved from search engines depend on the researcher providing keywords, a process that may lead to the exclusion of reports that are peripherally relevant but may be extremely important for the wider context of the study. Nevertheless, we think that the methodological triangulation throughout the phases of the study and the consultation of both official and ‘unofficial’ sources of information ensured methodological rigor and coherence (Tracy 2010) and has created a net that has captured the most important aspects of the financial aspects of counterfeiting providing a unique insight into this issue and generating future directions in research.

The nature of the counterfeiting business

Generally, the core of the counterfeit product supply chain comprises counterfeit manufacturing, transportation, storage and distribution/retailing. According to figures by the World Customs Organization, the US Government and the European Commission, most of the world’s counterfeit products originate from China (OECD/EUIPO 2017). In 2009, China was the source of US$205 million worth of counterfeit goods seized in the United States, which was 79% of the value of all counterfeit products seized that year (UNODC 2010). In 2014, 81% of all Intellectual Property (IP)-related seizures in the EU came from China and another 8% via Hong Kong, whereas in 2016 China was identified as the country of provenance making up almost 73% of suspected goods infringing Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) detained at EU borders in terms of value and 66% in terms of volume (OECD/EUIPO 2017). The movement of counterfeit products from China to the rest of the world is facilitated by the ownership of key shipping ports around the world. In Antwerp, for instance, one of the largest and busiest ports in the world, 3 out of 4 container docks are operated by Chinese corporations (EUROPOL/Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market 2016). Other important counterfeits producers include Turkey, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, Ghana, Morocco, Vietnam, Panama, India and Russia.

According to official and commercial association sources (see European Union 2017; Retail Times 2018), the United States and the European Union are major destinations for counterfeit products. In 2017 alone, the retail value of only the ‘top counterfeit items’ seized at EU border reached approximately € 0.5 billion (see Table 1).

A notable trend that has been observed in recent years is that the manufacturing of fakes has moved to the global North, including the EU. For example, Italy and Greece have been associated with the counterfeiting of fashion items, Lithuania with counterfeiting of alcohol and the UK with the counterfeiting of tobacco products. Currently, there are a number of illegal factories that have been dismantled by the authorities in various UK cities and towns, including Grimsby, Glasgow and Aberdeen (see Transcrime 2013; Antonopoulos and Hall 2015). According to one of our participants, the establishment of counterfeit tobacco factories within the UK has been a response to the low quality of the products manufactured in typical counterfeits-producing countries:

“Cause they were bringing crap in. Getting bales of crap tobacco from China into Poland and making cigarettes…. They’re garbage you know, and the crew asked me to fucking sell them I said no I’m out of it now, not doing fuck all for us. I said I’m not gonna sell that shit you know people don’t want them, they’re rubbish” (interview with criminal entrepreneur #2).

Intra-EU manufacturing involves brand logos being added at the point of sale in an attempt not only to reduce costs associated with production abroad but also to reduce or eliminate risks in the transportation phase by avoiding inspections by the customs at the external borders of the EU. The majority of this type of packaging material associated with (counterfeit) tobacco products, for instance, was stopped at the UK, the Netherlands or French borders and was recorded as having originated predominantly from China (EUROPOL/EUIPO 2017).

The UK has been one of the major destination countries for counterfeit products, something that is naturally affected by increased demand for branded products (Electrical Safety First n.d.; Hall and Antonopoulos 2016; Large 2019). As Electrical Safety First (n.d.) highlight, this extends to branded products that typically have higher safety risks, such as electrical products. From 2009 to 2012, for example, the UK experienced a sixfold increase in the number of counterfeit electrical goods seized by the authorities, a phenomenon fuelled by demand for “branded” designer headphones and gadgets, such as hair straighteners (The Guardian 2013). Anecdotal data gathered from enforcement officials suggests socio-economically deprived areas are usually hotspots for the sale of such counterfeit goods (see also Wiltshire et al. 2001).

Structure and scale of operations

Within the context of the counterfeiting business, some actors may be working in/for ‘organised crime groups’. However, most participants in the UK market are not always manipulated by so called ‘organised criminals’ as official accounts suggest (EUROPOL 2013). Our research found individuals involved in counterfeiting business are often self-employed entrepreneurs. What may be viewed by some as criminal collaboration between a ‘producer’ and a seller, or a wholesaler and a retailer, does not necessarily involve an employer-employee relationship but a business-to-business relationship. Indeed, an environment of great importance for the formation and consolidation of relationships for the counterfeit products trade is legal businesses. Legal businesses also operate as the context in which relationships (employer-employee and between/among partners) are forged and transformed into criminal business relationships, and dependability of individuals is manifested (see van de Bunt and Kleemans 2007).

Our research exposed a range of different schemes trading in counterfeit products that can be categorised based on scale:

-

Small-scale schemes: involving people of Eastern Europeans, Indian and Chinese heritage who live in the UK going to their countries for a short period of time and returning to the UK with the merchandise or British holidaymakers who visit counterfeit manufacturing hotspots abroad returning with various types of fakes. The type and brand of the merchandise bought in these countries to be traded in the UK is not only a case of the potential for profit but also considerations about access to potential customers that would be willing to buy the merchandise. One of our interviewees, ‘Dave’, is a 36-year old university graduate working as a full-time bartender, part-time English teacher from a city in the North West of England. He has been married to ‘Yuki’ for about 4 years (interview conducted in April 2017). They met when ‘Dave’ visited China for the first time with a friend in 2012 to teach English at a summer school for Chinese students planning to study at UK universities. Every summer he teaches for 6 weeks in Shanghai, and ‘Dave’ and ‘Yuki’ stay with ‘Yuki’s’ parents and brother in the city. In Shanghai, ‘Dave’ buys fake TAG Heuer watches for as little as £30 each to sell to UK-based customers. His decision to trade in counterfeit TAG Heuer instead of counterfeit Rolex watches is not based on being unable to access the latter brand but the fact that his potential clientele would be suspicious of the low price for Rolex — a commodity that they would find difficult to ‘back up’ anyway — and thus reluctant to buy:

“The watches are in relatively good condition and they look like the real deal. It’s not like we are selling Rolexes for £300 making people suspicious. TAG Heuer are good but not that good, and ‘Joe Bloggs’ can wear them in the pub or at work. The Rolex… you have to back it up” (interview with criminal entrepreneur #4).

-

Large-scale schemes: involve the importation of significant quantities (containers, truckloads) of various types of merchandise from China, Eastern Europe (Poland, Ukraine, Russia, Lithuania, etc.) and Arab states. The structure is largely fragmented when it comes to large-scale counterfeiting schemes, i.e. a chain of local transactions, although the structure also depends on the type of merchandise produced or smuggled, and the scale of the business. A counterfeit tobacco business is generally based on loose networks of entrepreneurs. More sophisticated products such as electronics and pharmaceuticals involve groups that are more centralised, groups with a major actor in them, who is usually very well-connected to people in other countries (Customs intelligence officer #1). The fragmentation of a network that is involved in a large-scale counterfeiting scheme is exemplified by the fact that often other members of the counterfeiting network — even those taking part in a crucial part of the process such as transportation — know very little or even nothing about the overall scheme (Interview with criminal entrepreneur #2) (see also Savona and Riccardi 2015).

In the counterfeit business (just as in other illicit markets, see Morselli and Roy 2008), the importance of ‘brokers’ — those actors that bring together two or more disconnected parts of the network — and the service they offer, is significant. Some of these brokers facilitate the entrance of individuals in a counterfeiting business or in a different level of the business. Other brokers introduce importers (even those involved in small-scale importation schemes) to the right sources of merchandise, which often ensures a certain level of quality (Interview with criminal entrepreneur #4). Brokerage can also be offered by people who are actively involved in the trade. One such example in the data is criminal entrepreneur #5, ‘John’, a 58-year-old transportation company owner. John oversees every detail in his business and applies the same principles in both his legal and illegal commercial activities. Furthermore, in many cases, brokers facilitate the international transportation of counterfeit products, storage and the provision of the relevant documentation to local authorities (EUROPOL/Officer for Harmonisation in the Internal Market 2016).

Economic, technological and extra-legal dimensions

An important aspect of the counterfeiting business, which is ignored by official, media and business analyses, is the fact that counterfeiting is embedded in legal production and trade practices in a globalised economy. There are numerous convergence points between legal and illegal supply chains. Occasionally, there is also a symbiotic relationship between the legal and counterfeit products supply chains. There is, for instance, evidence that counterfeiters have been selling designer knock-offs manufactured by the same craftspeople who produce the originals (UNODC 2010). The UK system enables open competition, and as such counterfeiters are allowed to enter the supply chain more easily because there is less supervision on the part of the authorities (EUROPOL/Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market 2016). A counterfeit product manufacturer in the vast majority of cases obtains raw materials from a legitimate material supplier. Counterfeiters often import unbranded commodities — which is not an illegal practice — and apply trademark labels and tags before the commodities are introduced into the retail market. Counterfeiting schemes take advantage of the normal commercial channels (e.g. postage services, transportation companies or maritime shipping companies and delivery companies) (Shen et al. 2010).

Counterfeiting schemes also take advantage of special economic zones (SEZs). These include free ports, free trade zones and export processing zones that are regularly used to transit counterfeit products. As deregulated conduits, free zones offer business-friendly economic environmental factors, such as the free flow of capital, lower taxes on imports and exports and less risk in terms of policing (Hall and Antonopoulos 2016. Counterfeiting entrepreneurs tend to ship their products via complex routes, with many transit points SEZ to facilitate the falsification of documents in order to hide the original point of departure of the counterfeit merchandise, to repackage and/or re-label the merchandise, and avoid interception of their merchandise by the authorities (OECD/EUIPO 2017).

Once imported in the UK, counterfeiters often use self-storage units to store counterfeit goods before they introduce them into the retail market, and these storage units are not properly (if at all) monitored by the legal companies operating them (see EUROPOL/Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market 2016). In many instances legal business are the sales or use context for the counterfeit products and integrally linked to a purely legal service process. Merchandise is very often sold in legal businesses that are related to the legal trade in the commodity (e.g. counterfeit alcohol being sold in a legal company importing alcohol and pubs).

Another important aspect of the counterfeiting business is the increasingly significant role played by information and communication technologies (ICTs), which also touches upon the role of the legal in the counterfeiting business since internet service providers, registrars, payment processors and payment gateways are integral nodes of the infrastructure needed to trade in counterfeit products online. The increase in counterfeit goods being traded has been particularly apparent in the context of various evolutionary phases in ICTs and electronic commerce since the late twentieth century, with the Internet now acting as an important avenue through which this criminal market is expanding (see Wall and Large 2010; Treadwell 2011; Hall and Antonopoulos 2016; Large 2019; Shen 2018). First, ICTs have facilitated the trade and contributed to the trade’s mutation to a significant extent. For example, apart from allowing the electronic transfer of money, it has transformed the retail activity of traders, coupled with a remarkable increase in the number of small parcels coming into the UK and corresponding deliveries in recent years (Interview with HMRC —HM Revenue & Customs— officer). Second, ICTs have expanded opportunities to engage in the business to a wide and diverse set of actors who are not necessarily involved in other forms of crime, and to experienced criminal actors looking to move into a low risk market (Interview with Police Intellectual Property Crime Unit officer; Interview with investigator for a private company). Finally, ICTs have also provided entrepreneurs with access to a significant number of potential customers. Social media sites, particularly Facebook, act as online sites for supply of counterfeit products. Some actors use a variety of social networking sites to advertise their products (Hall and Antonopoulos 2015; Intellectual Property Office 2017).

The financial management of counterfeiting

Capital to start and sustain a counterfeiting scheme

Start-up capital is required for someone to enter the counterfeiting business, cover the costs of establishing the business and operate it until some profit is generated. This initial amount depends largely on the product-type and the quantity and quality of the merchandise being traded. There is a wide range of sources that can be drawn upon for the initiation of counterfeiting operations. The first, concerning small-scale schemes, can be small funds from legitimate work and savings. This category includes start-up money from social security benefits. This becomes possible because of the extremely low funds that are required for one to enter a counterfeiting scheme selling on a small scale to friends and acquaintances. Ironically, such schemes funded by social security are essentially state-subsidised. Small-scale start-up capital can also include funds from legitimate work and savings, which allows virtually anyone with a small amount of capital to become involved in the business, from holidaymakers to students and those working internationally. The case of ‘Dave’, one of our interviewees and a counterfeit TAG Heuer watch entrepreneur, is indicative here. The money invested in his scheme is personal money; savings from his legal work as a bartender from September to June. The amount invested in buying the counterfeit watches is about £900 per year (Interview with criminal entrepreneur #4). In another case we came across a young man living with his parents operated a Facebook-based business delivering merchandise locally. He started the business by buying £200 worth of counterfeit merchandise from Bristol Fruit Market (a ‘Sunday market’ in South West England). The authorities estimated that he made a profit of £20,000 within 6 months (interview with investigator working in a private company).

Schemes are also funded with money from legal business. In this case, the actors are often owners of transportation/logistics companies or legitimate companies trading in the same commodity that is counterfeited (e.g. alcohol wholesalers trading in counterfeit alcohol). In cases where a scheme becomes successful, it can attract investment from others involved in the trade. Sometimes the criminal entrepreneurs are presented with opportunities to expand and invite people from their wider social and (legal) business circles to join the scheme. In this way, financing ‘consortia’ are established with the goal of importing larger loads of better quality merchandise.

A number of counterfeiting schemes are initiated by money invested by criminal entrepreneurs, who branch off into counterfeiting ventures after engaging in other illegal activities. For example, in one case we came across a cannabis trafficker from a city in North West England who invested money from the cannabis business into the counterfeit tobacco business because the risks were extremely low, and because he suspected that the police had become aware of his drugs business. It is also not unusual for criminals to invest small amounts of money into someone else’s counterfeiting scheme. This practice tends to be found in small localities in which everyone is familiar with one another and information about successful and profitable illegal schemes flows across social networks. We have found that this is especially the case with counterfeit tobacco (see also Antonopoulos and Hall 2015) and alcohol schemes. Occasionally, these local criminals extort their way into a counterfeiting scheme in something that could be described as a ‘forced investment’:

“I can mention one interesting case with proper criminals dealing in drugs getting involved in extortion etc. who forced their way into counterfeiting business. Poor guys selling cheap perfumes all of a sudden paid a visit by a crime group asking them in” (Interview with customs intelligence officer #1).

Some schemes are initiated by counterfeiting entrepreneurs with loans. In one of the interviews, the participant was aware of an entrepreneur who had asked for a small loan of £1500 as start-up capital from his son. In most cases, loans are provided by legitimate businesspeople. We know that loans come with differential interest rates in counterfeiting cases; however, we do not possess any information about the actual rates. Obtaining a loan for a counterfeiting scheme depends, firstly, on knowing the debtor personally and/or from previous business ventures. The latter is a common occurrence, especially among the transportation company owners who tend to collaborate on international projects, mostly in Eastern and Southern Europe. Legal business owners are more likely to be able to secure a loan and guarantee repayments because:

-

their owners tend to be known by the lenders via previous projects or simply as colleagues;

-

legal businesses have tangible assets (e.g. trucks, cranes, premises, furniture, etc.) that could possibly be liquidated, if there is a difficulty in the loan being repaid. Legal businesses also have a number of intangible but extremely important assets, such as a name and reputation in the business, which in a way guarantees some insurance for the lender;

-

legal business owners generally want to avoid the shame of not being able to repay a loan and the repercussions (financial or otherwise) this has for the borrower in the legal (and illegal) business world (Interview with forensic accountant) (see also Åkerström 1985).

Data from Chinese sources seems to suggest an additional ‘start-up’ scheme. It involves overseas (legitimate and illegitimate) businesses which have unauthorised goods made by Chinese (legitimate and illegitimate) manufacturers on an Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) basis. OEM refers to a company that makes parts and products for other companies which sell them under their own name or use them in their own manufacturing. Qian (2008) observed that a large number of private sector labour-intensive enterprises in China have been OEMs for established brand-name products in Japan and developed economies in Europe and North America. Due in part to a lack of IPR awareness among private sector manufacturers, especially village and township enterprises, IPR clauses were rarely incorporated in the OEM contracts, and neither had the issue of brand ownership ever been considered. Overseas counterfeiting entrepreneurs who are not genuine brand owners have the advantage of this negligence (Li 2007; Wang 2014). Under this scheme, financers might be legal entrepreneurs and initial production could be jointly funded by the Chinese OEM manufacturer and the overseas entrepreneurs. However, at this stage in the project we have no firm details about exactly how OEMs are financed.

The counterfeiting entrepreneurs and the investors/financiers are linked in the first instance via the local community and common acquaintances, and are often legal business partners. An investor’s share is ensured by trust. This trust is forged primarily in legal business and in previous legal and illegal projects (see von Lampe and Johansen 2004). However, in the case of ‘forced investment’ by an investor or a ‘consortium’ of investors, the major way in which a share is entrusted is fear of extortion or threat of violence (see Winlow 2001) from local criminals forcing their way into the scheme.

Settlement of payments in the counterfeiting business

Usually, small-scale criminal entrepreneurs involved in the counterfeiting business, such as ‘Dave’, tend to procure merchandise from legal retailers in other countries. Irrespective of the supplier, there are no special arrangements with regard to payment. Cash is almost always given up-front, which is also the arrangement in the transactions between sellers and buyers at the retail level; the basic principle here is “no money, no merchandise”. Occasionally, if the customer is a regular with a good record of payments, merchandise is given on credit. In one case discussed by an interviewee, counterfeit fashion items were given to a regular customer who wanted to wear them on an upcoming holiday but did not want to spend his holiday money (interview with criminal entrepreneur #5).

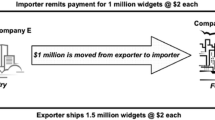

At the wholesale/importation level, however, credit is more common, especially in cases where the individuals involved have pre-existing working relationships and levels of trust. Alternatively, the provision of credit is facilitated by a broker, who may be able to vouch for the trustworthiness of the entrepreneur receiving the merchandise on credit. Other criteria of credit provision in the wholesale/importation level include evidence of how ‘healthy’ the legal business of an entrepreneur is, the presence of collaterals/assets in the criminal entrepreneur’s legal business, and evidence that payments (in previous legal and illegal projects) are delivered on time (interview with forensic accountant). According to Gambetta (2007: 87), “the best way to establish one’s reputation for trustworthiness is simple: behave well and live up to one’s promises”. When a legal business acts as the platform for the counterfeiting business, it becomes a context in which ‘good behaviour’ and meeting certain financial promises become crucial norms to be manifested and displayed whenever possible. These accounts are largely supported by our observations in China, but the extension of credit appears to be rare in the international trade in counterfeit goods with Chinese suppliers. Payment for a transaction usually starts with a nominal deposit, and the outstanding balance must be paid before the goods leave the port. In this process, agents or local international trading companies act as de facto guarantors to ensure that the goods do not leave the country without being paid for.

When the internet is used as a medium for the transactions involving counterfeit products, the payments are made either by PayPal or by credit card (interview with member of EU Intellectual Property Office). It is worth noting however, that the trend amongst large Facebook sellers based in the UK is that they increasingly prefer to be paid through bank transfers. The reasons are that when customers realise the products they bought online are fake or defective, they cannot claim their money back, as is the case with platforms such as PayPal (interview with investigator in private company). Legal businesses are used as front companies and existing payment facilities are used for the sale of counterfeit products. In terms of payments, e-commerce has simplified the process of buying and selling counterfeit goods, but also borrowing/renting the bank accounts of friends and family members (Hall and Antonopoulos 2016). Our observations in China suggest that e-payment via smartphones has now become the most popular payment method in everyday life in urban China, and zhi-fu-bao (Alipay) and wei-xing-zhi-fu (WeChat Pay) seem to be the most frequently used payment methods in transactions between Chinese suppliers and overseas buyers for both small and large schemes. Similarly, in the UK, as one interviewed academic noted “most of the lads I know involved in selling fakes do it all using Whats App, Facebook and Paypal on their phones” (Interviewed academic #2).

A variety of settlements that do not involve money are also present in a few UK cases. For example, when a batch or a truckload of the merchandise is seized by the authorities, usually at the borders, brokers and/or importers require some proof. In this case, those who are responsible for the merchandise when it was seized look for relevant weblinks or for local and/or national newspapers clippings that are scanned and sent electronically to the person who was supposed to receive the merchandise. Similarly, when a package of counterfeit UGG boots was intercepted by the HMRC, the person who was supposed to receive them was sent a letter from the HMRC stating that they have been seized. However, the customers scanned and sent this official letter to the producers and got another pair of boots free (Interview with EUROPOL official). According to an EUIPO (EU Intellectual Property Office) member:

“Some of these guys [counterfeiters] still have a policy of ‘If you’re not happy, you send it back and I’ll reimburse the money.’ Some of these guys really have a customer service. They do things very, very well” (interview with member of EU Intellectual Property Office).

In wholesale/importation schemes a number of people can act as payment facilitators. These are usually people who operate as the brokers who brought together two or more disconnected parts of the scheme in the first place. For example, in importations made in N. Ireland, people of Irish origin who live and work in China facilitate the payment process between the wholesalers and manufacturers of counterfeit cigarettes in China or the Chinese wholesalers. These Irish brokers have stayed in the country for many years, they speak the language, and they have previously conducted business with the Chinese. Financially speaking it is a simple process; the brokers operating in China are paid for their knowledge and local guanxi (social networks). They are paid towards the upper level (wholesale level) of the business, thousands of pounds per importation, or in the case of large deals, about 1% of the profit made by the UK importer. Unfortunately, because of the fragmented nature of the business and brokers’ tendency to operate on the international level, more detailed information is not currently available. What can be said, however, is that in critical moments (e.g. when a batch is late, seized, lost etc.), the broker, who was responsible for bringing together two other parties to conduct business, is the first point of contact for both parties, and makes sure that frictions of any kind are smoothed over and misunderstandings cleared. As ‘John’ — an importer who also acted as a broker for other entrepreneurs — emphatically put it during the interview: “every time a load was lost, seized, late, they busted my balls…‘Where is it? Where is he? Where are you? Who is going to pay?’...” (interview with criminal entrepreneur #5).

Payments between entrepreneurs can be settled outside the strict context of the illegal business, and spill over into the legal side of the business. This tends to be the case with business people who simultaneously do legal and illegal business. Sometimes, when a financial or other settlement cannot be made, or where there are delays in the supply of the merchandise, or bad batches, etc., ‘information’ becomes as currency in exchanges. This can be information about the legal and illegal dealings of a competitor, another legal or illegal business opportunity, or the possibility of the debtor acting as a broker between the disconnected parties:

“So we had the agreement that on such and such day I will have 350 Louis Vuitton bags. I had already paid the money and told them ‘I need the handbags on the day to push forward’. Guess what, the handbags were not delivered in time, my clients were not happy, I was not happy… The Polish [who the entrepreneur was to buy the stuff from] said ‘sorry boss, here’s your money, how can we make it up to you and stuff’. That’s not good enough, do you know what I mean… they said ‘OK, do you want to make some money? We will introduce you to our friend who wants to move handmade furniture from Krakow to London. Are we OK?’ Not bad, was it?...” (interview with criminal entrepreneur #6).

Spending and investing profits from counterfeiting

How counterfeiting money is spent and/or invested naturally depends on the profits but also the social environment of the entrepreneurs and the opportunities it offers, as well as the entrepreneur’s values and priorities (Zelizer 1989). For many the spending is survivalist in the sense that the proceeds of (primarily small-scale) entrepreneurship are used to buy essential commodities and services. The entrepreneurs who engage in this type of spending are far away from the ‘organised criminal’ stereotype. Many engage in the counterfeiting business to supplement benefits and/or low wages.

Profits from the counterfeiting business are often spent on lifestyle consumption, including luxuries (such as jewellery, antiques, cocaine, expensive cars with high running costs) that allow the conspicuous display of the counterfeiters’ success and personal wealth (see Hall et al. 2008): “quite funnily, they [counterfeiters] stick to the areas they come from, disadvantaged areas, and drive expensive cars… and they wonder why people snitch” (Interview with HMRC investigative officer). Ironically, the first thing ‘Dave’ bought with the money from his first importation of fake watches was a real TAG Heuer Carrera from a major jeweller’s chain in the UK: “I could not live with myself knowing that I wear a fake watch”. Other purchases include expensive furniture: “We can now say, ‘let’s go and buy this handmade coffee table or a dining table with 10 chairs, not six! We even got a king size bed without looking at the price” (Interview with criminal entrepreneur #4). Money is also spent on expensive holidays abroad: “Some people [counterfeiters] on Facebook it’s like they’re celebrities. Oh God, you’re in the Maldives again?” (Interview with investigator in private company) (see also Junninen 2006). In one case, which involved the importation of six metric tonnes of raw tobacco in hundreds of parcels from Belgium and the Netherlands to the UK, a criminal entrepreneur spent £1.1 million at betting shops in a single year (The Gazette 2016).

Unlike those entrepreneurs, who prefer to spend their profits on hedonistic pursuits (see Hall et al. 2008), some entrepreneurs, who are family-oriented, pay off their own and their (extended) family members’ debts and mortgages. Others in this category buy or renovate houses and other properties in the UK and abroad (Ireland, Spain or the entrepreneur’s country of origin for minority ethnic entrepreneurs) and/or pay for their children’s education. Family-oriented spending is usually modest, and in these cases entrepreneurs are careful to make sure that it does not extend too far beyond their legal income, thus avoiding too much attention (see also van Duyne and Levi 2005; Skinnari 2010).

Apart from spending, the more successful criminal entrepreneurs invest profits from counterfeiting to (legal) businesses linked to their own contacts and networks and areas of previous experience and knowledge (see also L’Hoiry 2013). For example, we came across an entrepreneur with an existing job in the food supply chain who sought to expand his business using profits from his counterfeit tobacco business. Actors are typically restricted to investing in areas in which they have some prior experience and expertise.

However, the counterfeiting business itself is also a common target for reinvestment. From the initial moment a scheme becomes successful, part of the profit is invested in subsequent schemes and occasionally — especially in the case of owners of legal businesses — towards expanding and/or diversifying. Some criminal entrepreneurs, especially those who are sole entrepreneurs or do not own a legal business that acts as a platform for their counterfeiting business, carefully consider the ‘profit-risk’ ratio of their business (see Dean et al. 2010). They deliberately re-invest relatively small amounts of money (£1000) and do not wish to expand but simply maintain a low volume-high value scheme because of the logistical complexities and risks involved in expansion or diversification; mostly financial risks that they do not have the capacity to absorb should something go wrong:

“Imagine if I brought over 100 watches… I would need a suitcase at least, and what would happen, if they are seized at the border? Exactly… my money is gone…” (Interview with criminal entrepreneur #4).

Similarly, those entrepreneurs with an online component to their business re-invest small amounts from their initial profits in order to maintain a low profile on specific online platforms:

“You just start off with one batch and then you build it up and build it up, but the problem you’ve got then is if you’re on eBay, eBay will make you become a trader so you will have to put information about yourself on there so you’d have to hide there, so there are obstacles that you’ve got to overcome and you’ve just got to hope that… we’re not watching. So that’s another way of doing it, it’s the investment is quite small” (Interview with National Trading Standards officer #3).

Investors involve criminal business-oriented investors. Although the usual route is for criminals to invest profits from other criminal business into counterfeiting because of the relatively lower risks involved, in one interesting case provided by the HMRC investigative officer we interviewed a couple that invested their profits from counterfeiting and other business activities in the construction of a hotel in Pakistan. This was used as a recruitment and transit point for individuals, who were to be trafficked into the UK for labour exploitation.

“We had information about a British Pakistani couple in Bradford. They were owners of a relatively big clothes company in Bradford and our intelligence suggested they were involved in counterfeiting. Clothes, bags, belts, you name it. We raided the premises in this area full of warehouses, and we started searching for money, products, documents. People were also working illegally in the business. One of my colleagues noticed a poster of a big building on the wall. Looked like a big house abroad but the thing is that this house was in bigger and smaller frames in their house too... In the living room, in the office, in the kitchen. Our investigation revealed that this building was in fact a hotel that was built with money from the counterfeiting business and it was used as a recruiting and harbouring venue for trafficked persons from Asia, mostly Pakistan. After they came to the UK, they would work in the clothes company, in restaurants...” (Interview with HMRC investigative officer).

Money laundering

It appears that in many UK-based cases money laundering is unnecessary because criminal entrepreneurs make relatively small profits, perhaps enough to guarantee the entrepreneur and his/her family in the UK or abroad a middle-class quality of life (see Skinnari 2010).Footnote 1 There are, however, large-scale projects in which criminal entrepreneurs need to launder significant profits to remove the specific qualities of the origin of the money and render it indistinguishable from all other money. In a survey conducted by the UK IP Crime Group, 49% of respondents to the UK’s trading standards survey indicated that they had worked on cases which involved both counterfeiting and money laundering (UK IP Crime Group cited in UNODC n.d.). In one of these cases, in 2016, a couple from the town of Ballymena in N. Ireland were sentenced for counterfeiting and money laundering offences. The couple traded in counterfeit BMW car accessories, making more than £40,000 a month. The Prosecutors requested a confiscation of the couple’s assets, which had an estimated value of over £1 million (Intellectual Property Office 2016).

Again, entrepreneurs who own a legal business have an advantage over those who do not, because they can integrate their counterfeiting proceeds with financial streams in the legal business. For example, as Lord et al. (2017) note, the proceeds of alcohol counterfeiting are hidden as an otherwise legitimate business transaction (e.g. purchase of water), and some profits are laundered via wages to employees. Our research has also identified a diverse set of money-laundering techniques involving investment in payday loan companies. The investment entry level is £100,000 and there is a typical return of approximately 30–40% (Interview with HMRC investigative officer). We have also come across investments of counterfeit proceeds in pawnshops or shops that deal in high value items. One of the criminal entrepreneurs interviewed launders money from counterfeiting in illicit puppy farms. He buys Rottweiler and Irish Wolfhound puppies for a relatively low price (£700–800) and sells them in their real/legal market value (£1200–1700) (Interview with criminal entrepreneur #5). In other cases, counterfeiting entrepreneurs launder money through cash-intensive businesses. For example, in a case we came across, the City of London Police identified Turkish counterfeiters who traded in trainers and sportswear, and laundered their proceeds through a café, which was also used to physically hide cash in safety deposit boxes.

Profits from the counterfeiting business are also sent via money transfer services from the UK to other countries, mostly in the Middle East, in which a less diligent approach or a lack of knowledge of foreign systems presents barriers to the tracking of criminal proceeds transferred abroad:

“Historically with money service bureaus it really is a challenge to keep a track because there is so much money flowing, you know, around the world and it can be very difficult to attribute it, you know. …We mentioned the Chaudhrys… this crime family in Manchester. All of their money went to Dubai, where it went from there I am not too sure. I was out there speaking to a representative of the CPSFootnote 2and she described the Dubai Authorities as having a light touch fiscal approach. When I said ‘what does that mean’ she said ‘well, they do not actually give a shit’” (Interview with UK Intellectual Property Office official).

The amounts per transfer seem to average around £2000 in order to avoid reporting thresholds, although significantly higher amounts are transferred in those cases where counterfeiting entrepreneurs know they are under investigation by the authorities (Interview with HMRC investigative officer) (see also EUROPOL Financial Intelligence Group 2015). Similarly, Hawala or hundi, informal money transfer systems (also known as ‘underground banking’) (Passas 2005), have been identified as a means of sending the proceeds of counterfeiting abroad. This method is popular in English cities such as Bradford, Manchester, Birmingham and localities of London, and among British Asian entrepreneurs involved in the counterfeiting business.

The legitimate banking system is also used for low-intensity laundering. An entrepreneur placed small chunks of his counterfeiting profits in a number of Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs). He also transferred profits from one bank account to the other in order to receive the tax-free interest for the amount deposited (interview with private investigator). However, examples of investment in offshore bank accounts are rather atypical cases because most entrepreneurs do not know people who could assist with the practicalities of setting up such accounts (see L’Hoiry 2013).

Discussion and conclusion

The counterfeiting business is yet another example of an illegal enterprise no longer “segregated, morally or physically, from the mainstream of economic society” (Naylor 1996: 80). Our research found that the trade is a fragmented business, which does not necessarily require a great degree of sophistication and management of finance and resources. Individual entrepreneurs and/or participants in counterfeiting networks are very often opportunists, who identify a small or big opportunity to secure a part of the market. Counterfeiting entrepreneurs possess skills and resources that are useful and functional for trade through their legal business and/or employment, and “for people with a legal commercial business, illegal activities can sometimes become completely interwoven with their daily pattern of activities” (Kleemans and de Poot 2008: 84). Others depend on personal and social ties that act as bridges to opportunities for profits; or what Kleemans and de Poot (2008) call ‘social opportunity structures’. In addition, these social relations “solve problems of cooperating in an environment that is dominated by distrust, suspicion and potential deceit” (van de Bunt and Kleemans 2007: 173).

ICTs facilitate communication between and among entrepreneurs who trade in counterfeit goods. The Internet now acts as an important avenue through which the counterfeiting market is expanding. There has been a significant increase in counterfeit goods being traded online. The internet is used as a medium for the transactions involving counterfeit products, with e-commerce markets simplifying the process of buying and selling. With regard to the online aspect of the counterfeiting business, however, it is important to remember that in reality the online element in the trade is largely based upon a set of established criminal acts: intellectual property crime and fraud. McQuade (2011) would define these criminal activities as adaptive in the sense that they constitute technological variations of ‘traditional’ crimes.

Financially speaking, the market in counterfeit products is an attractive market for a number of reasons. It is a potentially large market that covers virtually any legally produced commodity. It is a ‘perfectly competitive market’ (Makowski and Ostroy 2001) in the sense that anyone can get involved if they have a small amount to invest and — unlike perhaps the markets in drugs, arms, etc. — there is an extremely low entry threshold. The market is indeed open to anyone even if they (initially at least) intend to deal in small quantities.

As importers and wholesalers are primarily situated in the domain of legal business, apart from limiting risks, they have developed relevant expertise and social capital, and they have a range of options towards financing a scheme. For instance, a legal business is the platform for the easier provision of a loan by other legal entrepreneurs. Simultaneously, these legal businesses are also the terrain upon which payments are often settled and upon which the provision of credit is facilitated by trust among actors involved and by brokers who are able to vouch for the trustworthiness of the entrepreneur receiving the merchandise. In a sense, in the counterfeiting business what one can observe is the infiltration of the illegal business by the legal business, rather than the other way around. Most of the entrepreneurs we interviewed, although they manifested entrepreneurial acumen to a varying extent, did not manage profits in an efficient enough way so as to be considered a ‘threat’ to social order or the financial system. In fact, the management of profits from counterfeiting corresponded to the entrepreneurial acumen of the counterfeiter, the (immediate) surrounding economy (see Kruisbergen et al. 2015), and the entrepreneurs values and expectations (see van Duyne 2007). The entrepreneurs either possessed a small piece of the market with modest profits that simply spilled over into the legal economy, or they did not have the capacity to launder bigger profits (perhaps as a direct effect of anti-money laundering policy and practice) (Levi 2013). It is perhaps the entrepreneurs’ low value of assets coupled with their spending (many times chaotic spending) patterns that often results in “assessed levels of criminal benefits [being] unlikely to be recoverable” and attrition in confiscating the proceeds of crime (Bullock et al. 2009: 14).

When money laundering is the case, criminal entrepreneurs are embedded in legitimate businesses which provide for a very convenient extant setting for this type of financial management (see Kleemans and Van de Bunt 2008). In these cases, it is plausible to suggest that legal businesses receiving injections of cash (and indeed business opportunities) deriving from the trade in counterfeit products may have an advantage over their legal competitors that are not involved in counterfeiting or other illicit schemes (see Spapens 2017).

The generally unsophisticated financial management practices in the counterfeit products trade are the result of a number of factors, such as its fragmented, decentralised and ‘perfectly competitive’ nature, which in the UK creates an environment where crime-money is widely distributed rather than gathered in the hands of a few big players. This supports the results of research based on official data on asset-confiscation, which shows that although a large amount of organised crime-money exists, and irrespective of the type of asset this money is converted into, its distribution is unequal (see van Duyne et al. 2014). The same seems to apply to many of the counterfeiting entrepreneurs in the UK (see Bullock et al. 2009).

Overall, our research begins to draw attention to the global counterfeit goods market as one type of illicit financial flow. To date, there has been too much criminological focus on money laundering and, in socio-legal studies, too much focus on the economic losses of corporate intellectual property (IP) owners. More work is needed on the connection of money to various markets, the mechanisms involved in the connections between micro-finance, wealth management and private banks, and work that takes account of financial innovation, of which there was little knowledge pre-crisis and where legal and regulatory loopholes remain. In addition, more in-depth research work is needed to identify patterns of financial management in various counterfeit goods markets. All of this requires further collaborative research and innovative research techniques. The ambition is that our research, by drawing attention to a hugely neglected research area, will be used as an important building block for further research on the culture and economics of counterfeit goods.

Notes

Although, strictly speaking, such spending may still constitute money laundering pursuant to the UK’s anti-money laundering legislation.

Crown Prosecution Service.

References

Åkerström, M. (1985). Crooks and squares. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Antonopoulos, G. A., & Hall, A. (2015). The financial management of the illicit tobacco trade in the UK. British Journal of Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azv062.

Antonopoulos, G. A., & Papanicolaou, G. (2018). Organised crime: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Antonopoulos, G. A., Hobbs, D., & Hornsby, R. (2011). A soundtrack to (illegal) entrepreneurship. British Journal of Criminology, 51(5), 804–822.

Atkinson, R., & Flint, J. (2004). Snowball sampling. In M. S. Lewis-Beck (Ed.), The sage encyclopaedia of social research methods (pp. 1043–1044). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Brå. (2007). Where did all the money go? Stockholm: Brå.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Brown, R., Evans, E., Webb, S., Chenery, S., & Jones, M. (2012). The contribution of financial investigation to tackling organised crime. London: Home Office.

Bullock, K., Mann, D., Street, R., & Coxin, C. (2009). Examining attrition in confiscating the proceeds of crime. London: Home Office.

Camerini, D., Favarin, S., & Dugato, M. (2014). Estimating the counterfeit market in Europe. Milan: Transcrime.

Caulkins, J. P., Johnson, B., & Taylor, L. (1999). What drug dealers tell us about their costs of doing business. Journal of Drug Issues, 29(2), 323–340.

Chaudhry, P. E. (Ed.). (2017). Handbook of research on counterfeiting and illicit trade. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

CSD. (2015). Financing of organised crime. Sofia: CSD.

CSD. (2018). Financing of organised crime – Human trafficking in focus. Sofia: CSD.

Dean, G., Fahsing, I., & Gottschalk, I. (2010). Organised Crime. Oxford: OUP.

Electrical Safety First. (n.d.). A shocking rip-off. The True Cost of Counterfeit Products. Available online at: https://www.electricalsafetyfirst.org.uk/media/1510/true-cost-of-a-counterfeit.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2019.

Ellis, S., & MacGaffey, J. (1996). Research on Sub-Saharan Africa’s unrecorded international trade: Some methodological and conceptual problems. African Studies Review, 39, 19–41.

European Union. (2017). Report on EU customs enforcement of intellectual property rights. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

EUROPOL. (2013). EU serious and organised crime threat assessment. The Hague: EUROPOL.

EUROPOL Financial Intelligence Group. (2015). Why is cash still king? The Hague: EUROPOL.

EUROPOL/EUIPO. (2017). 2017 situation report on counterfeiting and piracy in the EU. The Hague: EUROPOL/EUIPO.

EUROPOL/Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market. (2016). 2015 situation report on counterfeiting in the EU. The Hague: EUROPOL/OHIM.

FATF. (2012). Financial investigations guidance. Paris: FATF.

Fleming, D. C. (2014). Counterfeiting in China. East Asia Law Review, 10, 14–35.

Gambetta, D. (2007). Trust’s odd ways. In J. Elster, O. Gjelsvik, & K. Moene (Eds.), Understanding choice, explaining behaviour (pp. 81–100). Oslo: Unipub.

Hall, A., & Antonopoulos, G. A. (2015). License to Pill. In P. C. In van Duyne, A. Maljevic, G. A. Antonopoulos, J. Harvey, & K. von Lampe (Eds.), The relativity of wrongdoing (pp. 229–252). Nijmegen: WLP.

Hall, A., & Antonopoulos, G. A. (2016). Fake meds online. London: Macmillan.

Hall, S., Winlow, S., & Ancrum, C. (2008). Criminal identities and consumer culture. Cullompton: Willan.

Hicks, T. (2015). Model approach for investigating the financing of organised crime. Sofia: CSD.

Hobbs, D., & Antonopoulos, G. A. (2014). How to research organised crime. In L. Paoli (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of organised crime (pp. 96–117). New York: OUP.

Home Office. (2007). Organised crime. London: Home Office.

ICC – International Chamber of Commerce. (2011). Estimating the global economic and social impacts of counterfeiting and piracy. Available online at: http://www.iccwbo.org/Advocacy-Codes-and-Rules/BASCAP/BASCAP-Research/Economic-impact/Global-Impacts-Study/. Accessed 15 March 2017.

Intellectual Property Office. (2016). Prison time for couple running rake BMW fake accessories. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prison-time-for-couple-running-fake-bmw-accessories-scam. Accessed 15 March 2017.

Intellectual Property Office. (2017). Share and share alike. Newport: IPO.

Intellectual Property Office and Foreign & Commonwealth Office. (2015). China-Southeast Asia anti-counterfeiting project summary report. Available online at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/482650/China-ASEAN_Anti-Counterfeiting_Project_Report.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2017.

Interpol. (2014). Against Organized Crime. Available online at: www.interpol.int. Accessed 15 March 2017.

IRACM. (2013). Counterfeit medicines and criminal organizations. Paris: IRACM.

Junninen, M. (2006). Adventurers and risk-takers. Helsinki: HEUNI.

Kleemans, E., & de Poot, C. (2008). Criminal careers in organised crime and social opportunity structure. European Journal of Criminology, 5(1), 69–98.

Kleemans, E., & Van de Bunt, H. G. (2008). Organised crime, occupations and opportunity. Global Crime, 9(3), 185–197.

Korsell, L., Vesterhav, D., & Skinnari, J. (2011). Human trafficking and drug distribution in Sweden from a market perspective. Trends in Organised Crime, 14(2–3), 100–124.

Kruisbergen, E., Van de Bunt, H., & Kleemans, E. (2012). Georganiseerde criminaliteit in Nederland. Den Haag: Boom.

Kruisbergen, E., Kleemans, E., & Kowenberg, R. (2015). Profitability, power, or proximity? European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 21(2), 237–256.

L’Hoiry, X. (2013). Shifting the stuff wasn’t any bother. Trends in Organised Crime, 16, 413–434.

Large, J. (2015). Get real don’t buy fakes’. Fashion fakes and flawed policy. Criminology and Criminal Justice., 15(2), 169–185.

Large, J. (2019). The consumption of counterfeit fashion. London: Palgrave.

Levi, M. (2004). The making of the UK’s organised crime control policies. In C. Fijnaut & L. Paoli (Eds.), Organised crime in Europe (pp. 823–851). Dordrecht: Springer.

Levi, M. (2010a). Combating the financing of terrorism. British Journal of Criminology, 50(4), 650–669.

Levi, M. (2010b). Preceeds of crime. Criminal Justice Matters, 81(1), 38–39.

Levi, M. (2013). Drug law enforcement and financial investigation practices. London: IDPC.

Levi, M., & Osofsky, L. (1995). Investigating, seizing and confiscating proceeds of crime. London: Home Office.

Li, L. (2007). Are Chinese counterfeits travelling around the world? Finance and Economics, 21, 21–23.

Lord, N., Spencer, J., Bellotti, E., & Benson, K. (2017). A script analysis of the distribution of counterfeit alcohol across two European jurisdictions. Trends in Organised Crime. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-017-9305-8.

Makowski, L., & Ostroy, J. M. (2001). Perfect competition and the creativity of the market. Journal of Economic Literature, 39, 479–535.

McQuade, S. (2011). Technology-enabled crime, policing and security. Journal of Technology Studies, 32(1), 1–9.

Mills, H., Skodbo, S., & Blyth, P. (2013). Understanding organised crime. London: Home Office.

Moeller, K. (2012). Costs and revenues in street level Cannabis dealing. Trends in Organised Crime, 15(1), 31–46.

Moneyval. (2005). Proceeds from trafficking in human beings and illegal migration. Strasbourg: CoE.

Morselli, C., & Roy, J. (2008). Brokerage qualifications in ringing operations. Criminology, 46(1), 71–98.

Navarrete, M. (2015) Europol’s role in countering criminal finances. Presentation at the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice, The Hague, March.

Naylor, R. T. (1996). From underworld to underground. Crime, Law and Social Change, 24, 79–150.

Naylor, R. T. (2004). Wages of crime. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

OECD/EUIPO. (2017). Mapping the real routes in trade of fake goods. Paris: OECD.

Passas, N. (2005). Informal value transfer systems and criminal activities. Den Haag: WODC.

Petrunov, G. (2011). Managing money acquired from human trafficking. Trends in Organised Crime, 14, 165–183.

Qian, J. (2008). Original equipment manufacture (OEM) and the infringements of trademark rights. Journal of Zhejiang University of Technology, 7(4), 474–480.

Retail Times. (2018). ‘Fake fashion items top EU border seizures, Kroll analysis shows’, Retail Times, 20th November. Available online at: https://www.retailtimes.co.uk/fake-fashion-items-top-eu-border-seizures-kroll-analysis-shows/. Accessed 14 Feb 2019.

Reuter, P. (1985). The organisation of illegal markets. Washington, D.C.: NIJ.

Reuter, P. (2013). Are estimates of money laundering volume either feasible or useful? In B. Unger & D. van der Linden (Eds.), Handbook on money laundering (pp. 224–231). Cheltenham: Elgar.

Reuter, P., MacCoun, R., & Murphy, P. (1990). Money from crime. Washington, DC: RAND.

Savona, E., & Calderoni, F. (2014). Criminal markets and mafia proceeds. London: Routledge.

Savona, E., & Riccardi, M. (Eds.). (2015). From illegal markets to legitimate businesses: The portfolio of organised crime in Europe. Milan: Transcrime.

Seale, C. (1998). Researching society and culture. London: Sage.

Shen, A. (2018). “Being affluent, one drinks wine”: wine counterfeiting in mainland China. International Journal of Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 7(4), 16–32.

Shen, A., & Antonopoulos, G. A. (2016). “No banquet can do without liquor”: alcohol counterfeiting in the People’s Republic of China. Trends in Organised Crime, 20(3–4), 273–295.

Shen, A., Antonopoulos, G. A., & von Lampe, K. (2010). The dragon breathes smoke. British Journal of Criminology, 50(2), 239–258.

Shen, A., Antonopoulos, G. A., Kurti, M., & von Lampe, K. (2012). The neoliberal wings of the smoke-breathing dragon: The cigarette counterfeiting business and economic development in China. In P. Whitehead & P. Crawshaw (Eds.), Organising neoliberalism: Markets, privatisation and justice (pp. 81–104). London: Anthem Press.

Silke, A. (2000). Drink, drugs and Rock'n'Roll: financing loyalist terrorism in Northern Ireland. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 23(2), 107–127.

Skinnari, J. (2010). The Financial Management of Drug Crime in Sweden. In P. C. In van Duyne, G. A. Antonopoulos, J. Harvey, A. Maljevic, T. Vander Beken, & K. von Lampe (Eds.), Cross-border crime inroads on integrity in Europe (pp. 189–215). Nijmegen: WLP.

Soudijn, M. R. J., & Zhang, S. X. (2013). Taking loansharking into account. Trends in Organised Crime, 16, 13–30.

Spapens, T. (2017). Cannabis cultivation in the Tilburg area. In P. C. In van Duyne, J. Harvey, G. A. Antonopoulos, & K. von Lampe (Eds.), The many faces of crime for profit and ways of tackling it (pp. 219–241). Nijmegen: WLP.

Sullivan, B. A., & Wilson, J. M. (2016). An empirical examination of product counterfeiting crime impacting the U.S. military. Trends in Organised Crime. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-017-9306-7.

The Gazette. (2016). Ciggie smugglers gambled away cash. The Gazette, December 3.

The Guardian. (2013). UK Sees Sixfold Increase in Seizure of Counterfeit Electrical Goods, The Guardian, March 29.

Titeca, K. (2019). Illegal ivory trade as transnational organized crime? An empirical study into ivory traders in Uganda. British Journal of Criminology, 59, 24–44.

Tracy, S. (2010). Qualitative quality: eight ‘big-tent’ criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851.

Transcrime. (2013). Factbook on the illicit trade in tobacco products: UK. Milan: Transcrime.

Treadwell, J. (2011). From the car book to booting it up? Criminology & Criminal Justice, 12(2), 175–191.

UNODC. (2010). The globalisation of crime. Vienna: UNODC.

UNODC. (n.d.). The Illicit Trafficking of Counterfeit Goods and Transnational Organised Crime. Available online at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/counterfeit/FocusSheet/Counterfeit_focussheet_EN_HIRES.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2017.

van de Bunt, H.G., & Kleemans, E. (2007) Organised Crime in the Netherlands. Available online at: https://english.wodc.nl/binaries/ob252_summary_tcm29-66835.pdf, Accessed 13 June 2015.

van Duyne, P. C. (2007). Criminal finances and state of the art. In P. C. In van Duyne, A. Maljevic, M. van Dijck, K. von Lampe, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Crime business and crime money in Europe (pp. 69–95). Nijmegen: WLP.

van Duyne, P. C., & Levi, M. (2005). Drugs and money. London: Routlegde.

van Duyne, P. C., de Zanger, W., & Kristen, F. (2014). Greedy of crime money. In P. C. van Duyne, J. Harvey, G. A. Antonopoulos, K. von Lampe, A. Maljevic, & A. Markovska (Eds.), Corruption, greed and crime money (pp. 235–266). Nijmgen: WLP.

von Lampe, K., & Johansen, P. O. (2004). Organised crime and trust. Global Crime, 6, 159–184.

Wall, D. S., & Large, J. (2010). Jailhouse frocks: Locating the public interest in policing intellectual property crime. British Journal of Criminology, 50(6), 1094–1116.

Wang, N. (2014). Trademark issues in regard to international OEM in China and countermeasures. Academic Exploration, 1(1), 49–93.

Wiltshire, S., Bancroft, A., & Amos, A. (2001). They’re doing people a service: qualitative study of smoking, smuggling, and social deprivation. British Medical Journal, 323, 203–207.

Winlow, S. (2001). Badfellas. Oxford: Berg.

World Economic Forum (2015) State of the Illicit Economy. Available online at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_State_of_the_Illicit_Economy_2015_2.pdf.. Accessed 11 June 2016