Abstract

This article develops an account of political legitimacy based on the articulation of a social choice theoretic framework with the idea of public reason. I pursue two related goals. First, I characterize in detail what I call the Ideal Two-Tier Social Choice Model of Politics in conjunction with the idea of public reason. Second, I explore the implications of this model, when it is assumed that decision rules are among the constitutive features of the social alternatives on which individuals have preferences. The choice of the decision rule cannot be made independently of considerations regarding the likelihood that individuals will vote based on political judgments that are not publicly justified. The result is an account of political legitimacy according to which only “elitist” decision rules are amenable to public justification. Some of them are plainly compatible with liberal democracies as they currently exist. Others are however more naturally associated with the concept of epistocracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This article develops an account of political legitimacy based on the articulation of a social choice theoretic framework with the idea of public reason. This general objective responds to an issue that dates back to Kenneth Arrow’s (1963) impossibility theorem. This theorem has been sometimes interpreted by economists and political scientists as implying that, because there is no democratic rule that can truly express the general will of the people, the legitimacy of democratic political institutions is threatened. This view has been notably expressed by the political scientist Riker (1988), who builds on Arrow’s theorem and other social choice results to reject the “populist” account which is pervasive in democratic theory.Footnote 1

However, social choice considerations do not force one into pessimism regarding the prospects of establishing the legitimacy of democratic institutions. They also provide resources to develop a normative and idealist account of what makes legitimate political decisions and the eventual use of coercion to enforce them. Such an account has been recently sketched by Dasgupta (2021). Dasgupta alludes to a model that usefully distinguishes between the (democratic) decision rule that is used to generate a social choice from individuals’ political judgments on the one hand and the way individuals form their political judgments on the other. I label this model the Ideal Two-Tier Social Choice Model of Politics, or “Two-Tier Model” (TTM) for short.

I pursue two related and specific goals. The first objective is to provide some “skin” on this model’s “bones”. Because Dasgupta only sketches the model, he does not provide many specificities regarding the criteria based on which we could justify the use of a particular (class of) decision rule(s), nor about how individuals should form their judgments. I shall argue that the idea of public reason developed by political philosophers such as Rawls (1993) and Gaus (2012) is relevant in both cases. The basic idea is that what makes a social choice legitimate is that it can be publicly justified based on reasons that everyone could reasonably endorse. The second objective is to investigate the implications of this model, when combined with the idea of public reason, regarding the range of political institutions that can be legitimized.Footnote 2 While Dasgupta argues that the criteria based on which we should assess individuals’ political judgments and decision rules are not the same, I argue that we should also consider a suggestion made by Arrow that the choice of the decision rule must also depend on individuals’ political judgments. Then emerges a form of “stability problem” that is familiar to public reason theorists. The choice of the decision rule cannot be made independently of considerations regarding the likelihood that individuals will vote based on political judgments that are not publicly justified. Based on these considerations, I suggest that the TTM generates a dilemma for democracy: either it bends toward a “populist” path where public justification requirements are not met, or it takes an “elitist” shape acknowledging that some political judgments are inferior or even unacceptable.

The argument is developed along the following steps. Section 2 provides a detailed account of the TTM, as well as of the social choice theoretic background that surrounds its development. Section 3 focuses on the formation of individuals’ political judgments based on the idea of public reason and characterizes the concept of “publicly admissible social orderings.” Sect. 4 surveys arguments that attempt to establish the legitimacy of democratic decision rules in the face of social choice theoretic results. Section 5 extends the TTM by arguing that the choice of a decision rule should itself be responsive to individuals’ political judgments and thus to public reason. Section 6 argues that in this context, there are public reasons to give weight to the possibility that many individuals will not in practice vote based on publicly admissible social orderings. Section 7 states and discusses the ensuing populist/elitist dilemma for democracy. Section 8 concludes.

2 The ideal two-tier social choice model of politics

The concept of “social choice” and the mathematical apparatus of social choice theory apply to a very broad class of phenomena where a choice or a preference attributed to a group or a collective can be meaningfully related to the choices or preferences associated with a set of agents constitutive of this group. It follows that problems of social choice emerge both in the economic and political domains.

As a notable illustration, Arrow (1963) opens his book Social Choice and Individual Values with an analogy between democratic and market mechanisms as two collective decision procedures, the two most significant in Western democratic societies with free-market economies. The analogy transpires throughout the book, for instance when Arrow suggests an isomorphism between the consumer’s and the citizen’s sovereignty.Footnote 3 This indicates that social choice theory can be equally applied to political issues related to the properties of voting mechanisms, and economic issues concerning the normative implications of market mechanisms. But while the formal apparatus is the same in both cases, its substantive interpretation may differ. It might then be tempting to distinguish between “political social choice theory” which is mostly concerned with the properties of voting rules from “ethical social choice theory” which deals with the issue of how welfare or other normative judgments should be formed.Footnote 4

Political social choice theory is best conceived as a set of mathematical explorations of ideal voting rules. Voting rules are mappings from sets of individual preference orderings (or individual choice functions) onto social preference orderings (or social choice functions). Given how individuals order alternatives (e.g., candidates to an election, or political programs), a voting rule determines which alternative is ultimately chosen, assuming that individuals’ votes reflect their preferences. Political social choice theory is devoted to uncovering the properties of known voting rules (majority rule, Condorcet rule, Borda rule, …) and their implications in light of desirable properties that we would like a voting rule to exhibit (e.g., to not induce cycles). Because it is not concerned with the implementation of voting rules and their effectiveness in actual political circumstances, political social choice theory is only about ideal voting rules as they are characterized by a set of formal properties.

Ethical social choice theory focuses on the properties of normative judgments, taking into account welfare but also equity and justice considerations, among others.Footnote 5 It concerns the assessment and eventually, the choice that would be made by an “ethical observer” who compares social alternatives based on a set of information that they deem relevant. This set of information presumably includes in particular the preferences of the individuals belonging to the relevant population over those social alternatives. But it may also reflect other aspects, notably pertaining to the observer’s value judgments about the welfare and other elements constitutive of the situations in which the different individuals are and that should be compared. Finally, once the information set is properly defined and the observer has settled on a way to eventually make interpersonal comparisons, there is still the question of how to aggregate individuals’ competing claims over resources or other relevant factors. In sum, ethical social choice theory has to deal with the same problem as its political counterpart, except for the fact that the “informational basis” available is potentially larger and that both the context in which the social choice (or evaluation) is made and who is making them are different. The latter difference indicates that not only the relevant informational basis but also the rule through which aggregation operates may differ from those used in a political context of vote aggregation.

While strictly speaking independent, it is worth considering the possibility that collective decisions are or should be the result of the interplay between both forms of social choices. This is a possibility already entertained early on by Arrow (1963: 71 − 2) when distinguishing between the aggregation of tastes and the aggregation of values, the former being presumably the task of the “ethical observer” while the latter of some voting rule as determined by the political regime.Footnote 6 More specifically, the final step may correspond to a democratic process implemented through a democratic voting rule, as Dasgupta (2021) has recently sketched:

“Ideally, citizens would vote in line with their ‘social preferences’, not their personal interest… Arrow chose the title ‘Social Choice and Individual Values’ for his book, his intention was to draw a distinction between voting rules and directives that should guide the citizen on whom to (more accurately what to) vote for. Ethical considerations that are directed at identifying voting rules are different from the ones citizens will wish to entertain for arriving at their social preferences over alternative policies… For a citizen to discover her social preferences over, say, economic states of affairs requires a different kind of ethical reasoning. She will, for example, want to compare people’s needs, which means interpersonal comparisons of individual well-beings would be an essential feature in her exercise”. (Dasgupta, 2021: 4, emphasis in original).

I shall take this sketch as the basis for the fuller characterization of the Ideal Two-Tier Social Choice Model of Politics (TTM), a graphical representation of which is given below (see Fig. 1). Dasgupta’s proposal has many merits. First, it articulates political and ethical social choice theories in a way that clarifies the kind of considerations on which citizens should ideally vote in a democracy.Footnote 7 Second, it makes it clear why enriching the informational basis of the social choice is not a knockout solution to Arrow’s impossibility result, contrary to a widespread belief that dates back to Sen’s (1970) pioneering treatment of Arrow’s theorem. The enlargement of the informational basis made possible by the allowance of interpersonal comparisons makes sense for the first tier, i.e., in the context of the construction of persons’ social preferences. But it is a far less appealing solution for the second tier where a democratic voting rule must determine the social choice. Not only, as Dasgupta suggests, would this increase the opportunities for strategic manipulations. It would also be difficult to make sense of the meaning of these comparisons. Third, we may tentatively conjecture that while individuals’ “tastes” are highly heterogeneous, their social preferences would reveal a significant degree of similarity. In particular, they might be single-peaked, in which case Arrow’s impossibility result no longer holds (Arrow, 1963: 77 − 9).Footnote 8

Now, as it is stated, the TTM has at least two blind spots. First, it is silent about the way individuals must form, as ethical observers, their social preferences – though Dasgupta (2021: 4) alludes to a mechanism of empathetic identification. This is important because without more precisions there is no reason to conclude that social preferences must be single-peaked. Second, there is no information about the process of determination of the voting rule. It may be argued that in democratic societies this issue is already settled at the constitutional level. But as far as the choice of a voting rule encapsulates value judgments, we may want to assess the grounds based on which it has been made. In other words, the legitimacy of democratic decision rules cannot be asserted without a reflection on the principles that justify their use to the members of the democratic polity. Indeed, as a normative model of the political legitimacy of social decision-making, the TTM indicates that legitimacy depends on both (i) the properties of the decision rule used to aggregate social preferences and (ii) the properties of the social preferences that are aggregated.Footnote 9 The next section will take the existence of a democratic decision rule as an exogenous parameter to focus on the latter aspect. This assumption will be relaxed after that.

3 Public reason and publicly admissible social orderings

The first tier of the TTM is concerned with the social preferences that each individual-qua-citizen can have over social alternatives based on which they will eventually cast a vote. The idea that individuals have social preferences is not as paradoxical as it may sound. It corresponds to the plausible assumption “that each individual has two orderings, one which governs him in his everyday actions and one which would be relevant under some ideal conditions and which is in some sense truer than the first ordering” (Arrow, 1963: 82 − 3). This familiar idea has been notably formalized by John Harsanyi [(1953); (1955)] in the development of his two utilitarian theorems.Footnote 10

Harsanyi’s theorems are however controversial both with respect to their derivation and their interpretation.Footnote 11 The alternative account of social preferences that I shall defend here is based on the idea of public reason. At the most general level, public reason can be defined as the requirement “that the moral or political rules that regulate our common life be, in some sense, justifiable or acceptable to all those persons over whom the rules purport to have authority” (Quong, 2018). The attraction of the ideal of public reason lies in the fact that it captures an intuitive requirement, at least as viewed from within the political morality of liberal democratic societies. Moral and political systems formulate demands that are addressed to individuals who are presumed to have the capacity to understand and abide by them. These individuals are viewed as having the capacity to identify reasons and values that justify their attitudes and choices. Now, it will happen that the demands of moral and political systems conflict with the reasons and values normative agents have identified. In this case, an individual will not have to accept the demands that are addressed to her, unless she has reasons to do so. And more is actually needed: these reasons must ultimately defeat the initial reasons the individual had identified. Because this is true for all individuals in the relevant population, justification must be minimally public, in the sense that a moral or political demand must be justified to everyone.

An influential account is developed by John Rawls [(1993); (1997)] as part of his treatment of the “stability problem” in his theory of justice. Rejecting the earlier solution provided in a Theory of Justice (Rawls, 1971), Rawls notes that individuals cannot rationally abide by the principles of justice adopted behind the veil of ignorance unless they expect others to abide too. In this kind of assurance problem, common knowledge that everyone has decisive reasons to follow the principles of justice is required. In this context, the role of public reason is to foster stability for the right reasons, “secured by a firm allegiance to a democratic society’s political (moral) ideals and values” (Rawls, 1997: 781). In Rawls’s account, public reason is thus related to the requirement that stability must rely on a consensus rather than on a mere Hobbesian modus vivendi. It guarantees that it is publicly recognized that everyone endorses the principles of justice for the same reasons, reasons which (by definition) are not specific to a particular comprehensive doctrine, and thus related to metaphysical, religious, or other non-political beliefs.

A particularly relevant aspect of Rawls’s account in the present context is how the idea of public reason bears on the kind of judgments that individuals-qua-citizens can express in relation to the issue of the legitimacy of the exercise of coercive political power:

“when may citizens by their vote properly express their coercive political power over one another when fundamental questions are at stake? … our exercise of political power is proper and hence justifiable when it is exercised in accordance with a constitution the essentials of which all citizens may reasonably be expected to endorse in the light of principles and ideals acceptable to them as reasonable and rational… since the exercise of political power itself must be legitimate, the ideal of citizenship imposes a moral, not a legal, duty – the duty of civility – to be able to explain to one another on those fundamental questions how the principles and policies they advocate and vote for can be supported by the political values of public reason.” (Rawls, 1993: 216-7).

Translated in the terms of the TTM, the Rawlsian requirement from public reason indicates that the social preferences based on which citizens vote must be grounded on reasons that everyone publicly shares. That presumably severely restricts the range of social preferences that can legitimately be expressed.

The Rawlsian account of public reason has been criticized in particular for this last implication. In general, the requirement that moral justification and political legitimacy depend on the existence of a consensus over the “right reasons” can be seen as overly restrictive, too demanding, and ultimately unnecessary. Because of this, it has been argued that this account fails to solve the stability problem identified by Rawls.Footnote 12 As an alternative, a “convergence” account of public reason states that proper justification only requires that everyone has non-defeated reasons to agree over a principle or a policy, provided that these reasons satisfy a moderate requirement of publicity and accessibility (e.g., Gaus, 2012).

The convergence approach thus opens the door to the possibility that citizens’ social preferences are partially grounded on non-public reasons, i.e., are justified by considerations that are not shared by everyone but that are nonetheless recognized as being reasonable. How can this be captured in the TTM? Individuals-qua-citizens have to form social preferences by first taking into account each individual’s personal preferences. The latter may reflect mere tastes as suggested by Arrow, but there is presumably no reason to restrict them to the economic domains of goods. Individual preferences may reflect interests broadly conceived and, more generally, conceptions of the good. To form social preferences, citizens have then to take what I shall call the public point of view according to which the public justification of a social ordering depends on it being based on a social evaluation function that every “member of the public” would have reason to accept as a basis for making social choices.

The rationale for this characterization of the public point of view is the following. Consider a randomly chosen member of the public, Beth. As a citizen, Beth would want to cast a vote expressing a social ordering that is captured by the (transitive and reflexive) binary relation\({\succcurlyeq }_{Beth}^{*}\). Suppose that among the set X of available social alternatives, \(x\in X\) is the only one ranks as best by \({\succcurlyeq }_{Beth}^{*}\). Now, by exercising her political power, I shall say that Beth is making an authority claim to all the other members of the public by imposing x. Beth takes the public point of view as soon as she realizes that all other members of the public also have the ability to make such an authority claim. At least two implications follow for Beth. First, she has to recognize that the exercise of political power to implement x cannot be legitimate unless everyone else has reason to endorse x. Second, the same condition applies to all other members of the public taking the public point of view and making authority claims. It follows that from Beth’s perspective, it is common knowledge that the profile of social orderings \(({\succcurlyeq }_{1}^{*},\dots ,{\succcurlyeq }_{Beth}^{*},\dots ,{\succcurlyeq }_{n}^{*})\) must be such that everyone has a reason to endorse it.

It is noteworthy that this requirement does not imply that every member of the public must have the same social preferences. Indeed, suppose that the n members of the public’s conceptions of the good can be represented by real-valued functions \({g}_{i}:X\to \mathbb{R}\). For Beth to arrive at her social preferences, she has to aggregate the information contained in the profile (\({g}_{1},\dots ,{g}_{n})\) using some function F. F is a social evaluation function that transforms a given profile (\({g}_{1},\dots ,{g}_{n})\) onto a social evaluation corresponding to some binary relation \({\succcurlyeq }^{F}\). There obviously are social evaluation functions that are not conducive to the public justification of social preferences, e.g., those issuing a cyclical social evaluation or those that are not responsive to all conceptions of the good. The range of social evaluation functions that cannot be ruled out a priori is however quite large, especially if the possibility of making “interpersonal comparisons of goodness” is acknowledged.Footnote 13 These functions are reflecting and give different weights to concerns for priority, equality, sufficiency, deservedness, or individual rights. The range expands even more once we acknowledge that social evaluations of policies are made in a context of uncertainty and may or may not (and in many different ways) take into account future generations. Finally, while it seems plausible to require that social preferences must be based on social evaluations that are acyclical, transitivity or completeness are not needed – that the social evaluation identifies a non-empty maximal set of social alternatives is enough.

The bottom line is that, depending on the specific context, many social evaluation functions can serve as public reasons for members of the public to endorse a profile of social preferences. We can be more specific. Denote F the (infinite) set of social evaluation functions and take as given a profile (\({g}_{1},\dots ,{g}_{n})\) of conceptions of the good. For each member of the public i, we can partition F into two subsets, the subset of functions that i regards as relevant to make an authority claim and the complementary subset of those that she does not. Now, the above characterization of the public point of view implies that if a function F belongs in the later subset for any member of the public, then it cannot provide a public reason justifying a social choice. We are then left with a set \({\varvec{F}}^{*}\subset \varvec{F}\) of social evaluation functions that can be used as part of public reason to justify a social choice. It is unlikely that this set must be empty and in the general case, it will not be a singleton. By assumption, while each of these functions has a non-empty maximal set, it is also unlikely that the maximal sets will be an identical singleton. Now, suppose we adopt the following definition:

Public Justification of Social Alternatives.Footnote 14 A social alternative \(x\in X\) is publicly justified to the members of the public if and only if it is ranked as best by at least one social evaluation function \(F\in {\varvec{F}}^{\varvec{*}}\).

We denote \({X}^{*}\subseteq X\) the resulting set of publicly justified social alternatives. Again, it is unlikely that X* will be a singleton. From this, a very natural characterization of publicly admissible social orderings follows:

Publicly Admissible Social Orderings. A member of the public i’s social ordering \({\succcurlyeq }_{i}^{*}\) is admissible if and only if for any state\(x\in {X}^{*}\) and any state \(y\notin {X}^{*}\), \(x{\succcurlyeq }_{i}^{*}y\) and not \(y{\succcurlyeq }_{i}^{*}x\). The profile \(({\succcurlyeq }_{1}^{*},\dots ,{\succcurlyeq }_{n}^{*})\) is publicly admissible if and only each of its components is publicly admissible.

There are at least two sets of factors that can explain why we should not expect the orderings in a publicly admissible profile \(({\succcurlyeq }_{1}^{*},\dots ,{\succcurlyeq }_{n}^{*})\) to be identical. First, following Gaus’s (2012) deliberative model, we should not idealize members of the public too much. That means in particular that considerations pertaining to personal interests are still relevant from the public point of view. In the general case, members of the public’s conceptions of the good will not rank the elements in X* identically and their social orderings may reflect this disagreement. This disagreement is compounded by the fact that members of the public are imperfectly informed about everyone’s conceptions of the good and the properties of social alternatives. As I shall argue later, this last point is especially relevant because it can result in a disagreement between the members of the public about the extension of the set X* and therefore jeopardize the public justificatory endeavor. Second, while members of the public agree over a set F* of social evaluation functions that can be used to justify a social alternative, they may still each retain a preference for some functions over others. Each member will then tend to rank social alternatives that are justified by their preferred function higher than those justified by other functions. This public reason version of the TTM captures well I think the interplay between (diverse) conceptions of public interest and personal interests described for instance by Downs (1962). It also points out that the Rawlsian “duty of civility” briefly discussed above is probably too demanding. In the end, it permits the formulation of a principle of ideal democratic citizenship that departs from Rawls’s:

Ideal Democratic Citizenship. In an ideal democracy, citizens should not want to impose on others, especially if they are in the minority, an alternative that cannot be publicly justified on a suitable basis. The ideal democratic agenda should therefore be restricted to publicly justified social alternatives.

It is now time to expand the discussion to the second tier of the TTM and assess the public justification of democratic decision rules against the principle of ideal democratic citizenship. The rest of the paper is devoted to this issue.

4 Legitimacy and democratic decision rules

The TTM I have outlined in Sect. 2, following Dasgupta’s (2021) sketch, assumes from the start that the aggregation of individuals’ social preferences is done based on a democratic decision rule – so that the TMM is really more an ideal social choice model of democracy rather than politics. This invites us to ask three related questions: what does it take for a decision rule to count as democratic? Among all the democratic decision rules, which one should we consider the most relevant as far as the legitimacy of social choices is concerned? Why should we privilege democratic decision rules over non-democratic ones?

These questions have of course to be dealt with, having the main results of social choice theory in mind. This includes Arrow’s impossibility result but also Gibbard-Sattherwaitte’s theorem about the strategy-proofness of voting schemes [(Gibbard, 1973); (Satterthwaitte 1975)]. These results establish that no voting rule altogether satisfies a set of normatively desirable properties. They imply that the case for a particular (democratic) decision rule cannot be made by showing that this rule is the only one to have all the desired properties. Tradeoffs have to be made. Depending on the tradeoffs we are willing to make, we will identify a set of rules that are preferable to others.

Democratic decision rules can then be characterized in terms of their properties as they are axiomatized in social choice theory. First, democratic decision rules should not rule out a priori political judgments. That means that their domain should be unrestricted. A second property is presumably that they must respect the unanimous judgments of the citizenry. The weak Pareto condition of Arrow’s and Gibbard-Satterwaitte’s theorems implies such unanimity property. Third, they must exclude rules that systematically impose the unanimous judgments of a subgroup of the citizenry. This obviously implies that the dictatorial rule cannot be democratic, but also “oligarchic” rules systematically choosing the alternative that is unanimously ranked first by a subgroup of voters.Footnote 15 Oligarchic rules also violate a fourth property that we may want to attribute to democratic rules, the property of anonymity. It entails that all voters are treated the same, i.e., a permutation in the set of voters does not change the output of the voting rule. Finally, we may reasonably assume that democratic rules must be monotonous in the following sense: if some alternative x is among the winners for some profile of social preferences, it must remain a winner if one of the social orderings in the profile is changed such that x is now ranked higher in this ordering than it was before.

Though not necessarily a property specific to democratic rules, we may also require that they generate a definite result. That means that it must systematically, for the domain of social preferences over which they are defined, identify a set of best social alternatives, i.e., a set of “winners”. Now, the major results of social choice theory kick in. We know that if the domain of social preferences is rich enough, this will not be systematically the case, provided that the democratic social choice among any subset of alternatives must depend only on voters’ social preferences over this subset, i.e., the rules satisfy the independence of irrelevant alternative condition. Such democratic rules will sometimes generate cycles, implying that the set of winners will be empty.

If we grant the claim that at least in an electoral context, the independence condition is compelling, troubles may arise for the view that the use of democratic rules underlies political legitimacy. The results of social choice theory indeed indicate that (i) in some cases, the democratic social choice will not properly reflect citizens’ social preferences, either because (a) no social alternative can be identified as best due to a cycle or (b) it results from strategic manipulations. Moreover, (ii) the democratic social choice will often be arbitrary because it depends on the democratic rule used and there is no rule that is unambiguously superior to the others.Footnote 16

On top of these results, the idea of public reason indicates that whether there is a decisive reason to use a particular rule guaranteeing the legitimacy of the resulting social choice depends on the same justificatory requirements as those applying to individuals’ social orderings. I shall argue however that once we submit political decision rules to public reason, it is no longer obvious that democratic rules as characterized above must be systematically preferred.

5 Social preferences over decision rules

As Dasgupta (2021: 4) plausibly suggests, “[e]thical considerations that are directed at identifying voting rules are thus different from the ones citizens will wish to entertain for arriving at their social preferences over alternative policies.” Ethical and political social choice theory are not concerned with the same issues, even though within the TTM they participate to determine what makes a social choice legitimate. As a result, we should not expect that a particular reason for imposing a given requirement in ethical (political) social choice theory must also hold for political (ethical) social choice theory.Footnote 17 On the other hand, the idea of public reason indicates that even though the relevant reasons differ in the two tiers of the TTM, they must in both cases be public. The demand for public justification therefore also applies to political decision rules.

That public reason covers both tiers of the TTM is apparent in the writings of many public reason theorists. For instance, alongside his “duty of civility” that applies in the context of the TTM to the content of individuals’ social preferences, Rawls (1993: 137) characterizes a “liberal principle of legitimacy” according to which “our exercise of political power is fully proper only when it is exercised in accordance with a constitution the essentials of which all citizens as free and equal may reasonably be expected to endorse in the light of principles and ideals acceptable to their common human reason.” If we plausibly assume that this constitution must define at least some of the decision rules that serve to elect public officials, then the liberal principle of legitimacy clearly extends the domain of public reason to the choice of political decision rules.

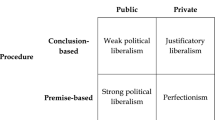

Interestingly, we already find in Arrow’s (1963: 89–91) pioneering work the idea that the choice of political decision rules is itself an object of social choice theory – an idea that he only briefly sketches and that he obviously does not articulate in terms of public reason. Basically, Arrow’s proposal is that individuals’ (social) preferences that are aggregated could also be defined over the set of political decision rules. This is particularly justified, he writes, “if the mechanism of choice itself has value to the individuals in the society.” At the formal level, the proposal entails that social alternatives in the set X are k-dimensional vectors of characteristics, i.e., \(x=({x}_{1},\dots ,{x}_{k})\) for all \(x\in X\), with the k-th characteristic the decision rule based on which x shall be selected.Footnote 18 A reduced-form version of this model partitions a social alternative x into two components, a variable \({x}_{o}\) describing the outcome and a variable \({x}_{p}\) describing the procedure through which x has been selected.

Incorporating the decision rules into the description of social alternatives implies that individuals’ social preferences also range over decision rules. I see then two plausible ways of articulating an individual’s social preferences with how they order political decision rules:

Strong decision rule preference

If we denote S ⊂ X and S’ ⊂ X the subsets of social states which are chosen by two decision rules D and D’ respectively, an individual i (socially) prefers a decision rule D to a decision rule D’ if and only for any x ∈ D and y ∈ D’, \(x{\succcurlyeq }_{i}^{*} y\).

Weak decision rule preference

An individual i (socially) prefers a decision rule D to a decision rule D’ if and only, for all pairs of x, x’ where x and x’ are identical except for the fact that x is selected by D and x’ by D’, \(x{\succcurlyeq }_{i}^{*}y\).

For the sake of illustration, consider the following example. Suppose a 5-individual society that must settle on a tax scheme. Three tax schemes are put on the agenda: a progressive scheme, a proportional scheme, and a regressive scheme. Suppose moreover that the social choice can be made along with two different decision rules: a democratic rule and a dictatorial rule. On the former, the scheme is chosen based on a Condorcet procedure. On the latter, one of the five individuals is randomly picked, and this individual’s preferred scheme is chosen. We thus have a state space X of 6 social alternatives from which to choose (see Fig. 2):

The individuals’ (social) preferences \({\succcurlyeq }_{i}^{*}\) over X are here assumed to be reflexive, complete, asymmetric, and transitive, and as follows (see Fig. 3):

The Condorcet procedure generates the following preference ordering (only keeping the social alternatives that can be chosen with a democratic rule):

Depending on whose individual is picked, the dictatorial rule will lead to the choice of x’ (with probability 1/3) or z’ (with probability 2/3). By definition, the two decision rules will not lead to the same social choice (as each decision rule eliminates one-half of the social alternatives). More importantly, which decision rule is used also makes a difference about which scheme will be chosen, as the democratic rule selects the progressive scheme, while the dictatorial rule is more likely to choose the regressive scheme. In this example, it is noteworthy that individuals do not agree with respect to which decision rule should be used. Indeed, using the above definitions of social preferences over decision rules, individual A strongly prefers the democratic rule to the dictatorial rule, while E has a contrary preference. But neither B, C, nor D has any preference in this sense. In the same way, A, B, and D have a weak preference for the democratic rule, while C and E have a weak preference for the dictatorial rule. So, there is no agreement over a decision rule, independent of the definition we use.

This disagreement can be worrisome from the perspective of public justification and legitimacy. Because the two decision rules do not lead systematically to the same outcome, using either of them results in the social choice being arbitrary. Moreover, adding a layer of decision rule, i.e., searching for a higher-order decision rule to choose lower-order decision rules is not a solution, unless we expect that unanimity will emerge somewhere in these higher orders. But this is unlikely. The difficulties are even made more severe once we realize that unless individuals’ (social) preferences ascribe a strong (maybe lexicographic) priority to which decision rule is used over the outcome it leads to (as individuals A and E in the example above), there is a strong incentive for individuals to misrepresent their views about decision rules. We may wonder then if the idea of public reason offers any way to overcome these difficulties. I shall argue that this is the case, though it comes at some price for the privileged status we tend to ascribe to democratic rules.

6 Democracy and the use of (non) public reasons

Working within the convergence account of public reason, Kogelmann (2017) argues that what he calls the “indeterminacy problem” we have just characterized is more or less acute depending on the assumption we make about the diversity of preferences in the population. At one extreme lies the “impartial culture assumption” according to which, “for every individual in the population, there is an equal chance of that individual having one of the logically possible preference orderings given the feasible set of alternatives” (Kogelmann, 2017: 222).Footnote 19 In this case, considering a set of major decision rules (plurality voting, Borda count, …), rates of convergence are relatively low and are lower the larger the population is. That means different decision rules will very often result in different social choices for the same profile of preferences. Justification and legitimacy are hard to achieve then, as we have seen.

Prospects look more promising however if the domain over which the decision rules are defined is restricted. For instance, in case we impose the “never-worse restriction”, according to which for any triple \(x,y,z\in X\), there is at least one social alternative that is never ranked worst by everyone, increasing the size of the population increases the rate of convergence on the Condorcet winner (Kogelmann, 2017: 225).Footnote 20 This is potentially an important result. Recall that we are considering the social preferences of members of the public, i.e., preferences that have already gone through the filter of public reason. By assumption, members of the public taking the public point of view only exhibit publicly admissible social orderings – at least in the case they are sufficiently informed about everyone’s conception of the good. Public reason narrows the set F of social evaluation functions to F* and correspondingly the set X of social alternatives to the set X* of public alternatives that are publicly justified. Therefore, whatever the decision rule used, its domain is restricted to the set of preference profiles where the social alternatives \(x\in {X}^{*}\) are all ranked above the social alternatives \(y\in X\setminus {X}^{*}\). In some cases, this may be enough to achieve the relevant restriction.Footnote 21 The arbitrariness that was worrying us above decreases as the size of the population increases.

Extending the definition of the members of the public’s social preferences over the set of decision rules strengthens the import of this result. Sen (2009: 110) contends, the mathematical results of social choice theory, as the one just reported, “can be input into public discussion,” they are “partly designed to be contributions to a public discussion on how these problems can be addressed and which variations have to be contemplated and scrutinized.” Members of the public can then rightfully consider that the results of social choice theory are relevant to order decision rules. Considering that convergence is a desirable result since it increases the likelihood of making legitimate social choices and thus avoiding conflicts, this may reasonably give members of the public a public reason to regard all the democratic decision results that permit convergence as almost equivalent. The social preferences over decision rules would then display a relatively high level of homogeneity among the members of the public, possibly ranking several democratic rules as best. In this case, while the choice of a decision would still remain arbitrary, this arbitrariness would be benign and indeed unproblematic from the public point of view.

Whether this optimistic outlook can be sustained depends however on the total set of considerations that are relevant from the public point of view to order decision rules. It should be first acknowledged that there is of course no guarantee that the relevant kind of restrictions will obtain for social preferences over decision rules. Notably, as Kugelberg (2022) rightfully argues, it seems to be difficult to identify a salient dimension along which (democratic) decision rules could be unanimously arranged by the members of the public – a necessary condition for the singled-peak restriction for preferences over decision rules to obtain. More generally, even though we may expect members of the public to have more structured social preferences than those corresponding to individuals’ conceptions of the good – if only because everyone agrees that the social alternatives in the subset X* must be ranked above those in the complementary subset – it is far from guaranteeing that the single-peak restriction obtains.

If we assume that the domain over which social preferences are defined includes decision rules, there is no obvious reason to not assume the same for the preferences that reflect individuals’ interests and conceptions of the good. Therefore, social preferences over decision rules should be responsive to how individuals judge decision rules based on their interests and conceptions of the good. If people tend to judge that democratic decision rules are better than non-democratic ones, this surely must count when members of the public are ordering social alternatives and thus decision rules. However, other considerations are relevant. Two, in particular, seem to be especially important.

First, given the lack of information and the general level of uncertainty in which social choices are made, and also the existence of self-serving bias, members of the public must account for the fact that both individual and social preferences may be particularly noisy. This is especially the case for preferences over decision rules. By assumption, individuals know their place in society and their conceptions of the good may reflect preferences for decision rules that are more likely to serve their interests.Footnote 22 Members of the public themselves must also acknowledge that when forming their social preferences, they may lack some relevant information about individuals’ interests or the features of social alternatives. That may justify that individual preferences over decision rules should not be aggregated the same way as preferences over other aspects of social alternatives.

Second, and even more importantly, I shall claim that members of the public have a strong (public) reason to give weight to the fact that, in political practice, individuals are unlikely to take the public point of view and to vote based on publicly admissible social orderings. In other words, while the TTM assumes that the legitimacy of democratic social choices partially depends on the content of the social preferences that serve as an input for the democratic decision rule, one of the facts accessible to the members of the public when forming their social preferences over decision rules is that in general, the input will not entirely consist of publicly admissible preferences. Or to formulate the issue in still another way, members of the public must assume that the Ideal Democratic Citizenship principle is unlikely to be respected by actual political practices.

Note that I am not arguing here that individuals always vote in ways that reflect their pure personal interests and completely disregard the “public interest.” The empirical literature on voting behavior suggests quite the contrary actually (e.g., Achen & Bartels, 2016). The problem is rather that voters’ conceptions of the public interest are likely to be distorted by many factors, including cognitive biases. Even though they do not vote to serve their personal interests, voters’ choices are likely to reflect prejudices, as well as biased treatment or just sheer lack of information. In saying this, I am not suggesting that hiding somewhere is the “true” conception of public interest and that voters’ biased conceptions are randomly dispersed around it.Footnote 23 As we have seen, social preferences are likely to be quite diverse and far from being unanimous. The bottom line is rather that voters are generally not public reasoners, both because they are not incentivized and do not have the ability to be so. But this is nonetheless exactly what the TTM and the principle of Ideal Democratic Citizenship that can be extracted from it are requiring.

One could answer that I am making an unfair requirement. The TTM is explicitly formulated as a normative model of (democratic) politics. That the assumptions of a normative model are unlikely to be satisfied in practice should not be used against it and is just irrelevant for its assessment. With this, I fully agree, however. I do not think that what we know about voters’ actual behavior disqualifies the TTM and the idea of public reason as an account of political legitimacy. This is quite the contrary actually. The claim I am making here is rather that even for a normative “ideal” model, empirical knowledge is relevant as long as this knowledge indicates that this model is likely to fail or to succeed on its very own terms. It is easier to understand this point if we characterize it in terms of a problem of stability of a similar kind as the one identified by Rawls in his theory of justice. This is exactly what has occupied Rawls in the third part of A Theory of Justice (Rawls, 1971) and in his subsequent “political turn” (Rawls, 1993). Indeed, Rawls was clear about the fact that stability considerations, i.e., whether individuals will abide by the principles of justice once the veil of ignorance is lifted, are relevant for the choice of principles of justice in the original position (Rawls, 1971: 498). Members of the public face a similar issue here. When they form their social preferences, including over decision rules, they have to acknowledge that the likely actual behavior of voters is also a relevant consideration in terms of public justification. Otherwise, the risk is to settle on a decision rule that will fail to deliver a legitimate social choice by not picking a publicly justified social alternative, while this is however the point of the whole public justificatory endeavor.

7 Populism against Elitism

The way I have just framed the problem within the TTM converges with Jason Brennan’s (2022) more general argument regarding the articulation of public reason liberalism and democracy. According to Brennan, “the public reason project appears grounded in the populist paradigm, which sees the vast majority of citizens as rather opinionated about politics.” (Brennan, 2022: 151). Here, the term “populism” refers to Achen and Bartel’s (2016) label that corresponds to the view that “voters are genuinely ideological, they have many politically-salient normative and empirical beliefs, they vote on the basis of those beliefs, and politicians in some way tend to enact the policies which voters advocate.” (Brennan, 2022: 136). The problem, Brennan goes on to argue, is that the populist account is false in light of the empirical literature on voters’ behavior and that public reason liberals tend to ignore this fact.

This clearly echoes what I have just said above. How voters actually behave is in itself a public reason that is relevant to choosing a decision rule. There is no obvious reason to exclude this information from the domain of public reason. This “realist” insight becomes especially prominent within the TTM, at least if we accept the claim that decision rules are one of the constitutive features of social alternatives over which members of the public have to form social preferences.

Where does it lead us? I think first we have to be clear on the fact that while this insight is important, it is not decisive in the sense that it does not lead to any obvious answer regarding the issue of which decision rules are amenable to public justification. In other words, I shall argue that the realist insight is a public reason to socially prefer non-democratic decision rules but falls short of identifying a single best decision rule. The second point is a more constructive one. In line with Achen and Bartel’s and Brennan’s “populist view” of voters’ behavior, we can identify a “populist view” of legitimacy. On the latter, the preferences that are aggregated through the majority rule and the social choice that results are constitutive of the general will.Footnote 24 This property confers to the social choice its legitimacy. The populist view of legitimacy is more plausible if the populist view of voters’ behavior is true. Though the latter by no means logically implies the former, the arguments briefly surveyed in Sect. 4 at least provide avenues for connecting the two views. But if the populist view of voters’ behavior is false, the populist view of legitimacy becomes hardly acceptable, especially on the TTM as we have articulated it with the idea of public reason. In general, voters will just fail to vote according to their publicly justified social preferences. Because of that, even if we grant the claim that the majority rule tracks the “general will”, this general will not be publicly justified.Footnote 25

In the context of the TTM, I, therefore, contend that the idea of public reason supports what I suggest calling the “elitist view” of legitimacy. I would characterize it in the following way,

The Elitist View of Legitimacy. Members of the public who are aware of the fact that voters are unlikely to vote based on publicly admissible social orderings have strong reasons to socially prefer elitist decision rules over democratic rules.

Let us call a decision rule “elitist” if at least one of the following is true: (i) its domain is restricted to the subset of social orderings that are publicly admissible; (ii) some voters’ social preferences are given more weight than others; (iii) it is “oligarchic.” In each case, a property of democratic decision rules as characterized in Sect. 4 is violated. The unrestricted domain condition is violated by (i), while (ii) and (iii) both violate anonymity. We can also imagine more complex elitist decision rules, e.g., a decision rule that makes the social choice depend on the unanimous judgment of an oligarchy (eventually a dictator) only in case some of the social preferences expressed are not publicly admissible and/or the social choice picks a social alternative that is not publicly justified. Elitist decision rules have in common to deny that the legitimacy of the social choice is grounded in the fact that it results from a (social) preference being held by the majority of the citizenry.

Two remarks are in order before finishing. First, while elitist decision rules are non-democratic in a purely social choice theoretic meaning, they are not all non-democratic in the sense of the political morality of Western liberal democracies. For instance, the “complex” elitist decision rule given as an illustration above is nothing but a formal and simplified version of a democratic regime with a judicial review. In general, many social decision processes that are prominent in current liberal democracies are “elitist,” reflecting the early and widespread concern that a “populist” democratic regime may issue social choices that go against basic rights and liberties or generate dire consequences. Some elitist decision rules are largely compatible with the so-called “epistemic” conception of democracy. This is especially the case with the deliberative accounts that have been developed within this conception, sometimes in conjunction with the idea of public reason (e.g., List, 2006). The main idea is that deliberative procedures could help trigger a convergence of (social) preferences and judgments, thus escaping various impossibility results but also eliminating biased or false views. What remains unclear in this literature is however how deliberations should be conducted to lead to the desired results, acknowledging that empirical evidence is mixed about their effectiveness.Footnote 26 Finally, other elitist decision rules are more in line with an “epistocratic” political regime. Giving different weights to the social preferences of voters according to some criterion is for instance similar to the system of plural voting suggested by Mill (2015). The systems of the simulated oracle and the epistocratic council with the power to veto law voted by the citizens, as discussed by Brennan (2016), also correspond to elitist decision rules.

In practice, elitist decision rules can therefore take many different shapes and are compatible with several kinds of political regimes. The use of elitist decision rules may for instance be appealing in the context of oligarchic bicameralism of the kind recently discussed by Kogelmann (2023), though not along the same design. In Kogelmann’s proposal, the higher chamber would be elected based on traditional majoritarian democratic rules while the lower chamber would be composed by sortition, i.e., a random selection among the citizenry. A more elitist version of oligarchic bicameralism would have the lower chamber elected by a majoritarian democratic rule or composed by sortition but with the upper chamber selected by an elitist decision rule, eventually more typical of an epistocratic regime. To explore all the possibilities is well beyond the scope of this paper, but the basic idea remains the same. Members of the public have strong reasons to at least counterbalance the populist tendencies of democratic decision rules with elitist rules that restrict the range of social preferences that can be expressed (violation of unrestricted domain) or grant some subgroup of voters more weight or decisiveness (violation of anonymity).

The second remark is that, while I argue that members of the public taking the public point of view have strong reasons to prefer elitist decision rules, I would not go as far as to say that there are equally strong public reasons to prefer a specific elitist decision rule over others. That means that there is no reason to expect that members of the public would unanimously prefer one elitist decision rule. Different orderings of decision rules will appear in the set of publicly admissible social orderings, the only restriction being – if my argument is correct – that social alternatives with democratic decision rules should be ranked below elitist decision rules.Footnote 27 But then, what determines the choice of a decision rule? Invoking a second-order decision rule is unlikely to solve the problem. At this point, I think that the “indeterminacy problem” cannot be solved by purely social choice theoretic means. The choice of decision rules depends on the political and social morality of society and the latter is shaped by factors that exclusively belong to social choices. As argued at length by Gaus (2012), this includes evolutionary mechanisms that put different societies on different paths, sometimes per sheer luck. A reasonable conjecture is that the range of plausible elitist decision rules and the probability that each of them is adopted is determined by the society’s political morality and culture. For instance, in a society with a strong democratic political culture where the right to vote is seen as constitutive of political equality, it is unlikely that elitist rules more naturally associated with an epistocratic regime could be effectively adopted and followed. Beyond this conjecture, the remaining indeterminacy is however not problematic if we consider that the role of political philosophy and normative economics is not to provide full-fledged solutions to normative problems but rather guidance to address those problems. This is exactly what the TTM combined with the idea of public reason do. What the TTM and the idea of public reason permit in particular is to determine if the end state of the evolutionary paths can be publicly justified to citizens, eventually motivating attempts at reforming the prevailing decision rules.

8 Conclusion

This paper has pursued two related goals. First, following Dasgupta’s (2021) sketch, I have characterized in detail the Ideal Two-Tier Social Choice Model of Politics in conjunction with the idea of public reason. Second, I have explored the implications of this model, following Arrow’s suggestion that decision rules are among the constitutive features of the social alternatives on which individuals have preferences. The result is an account of political legitimacy according to which only elitist decision rules are amenable to public justification. Because in general voters are unlikely to vote based on publicly admissible orderings, the legitimacy of social choices cannot be grounded on the fact that they reflect majoritarian social preferences. As individuals reflecting on the public justification of their social preferences over decision rules – i.e., members of the public taking the public point of view – must acknowledge this insight, only social choices based on elitist decision rules are legitimate.

While this result may sound controversial, the range and diversity of elitist decision rules should be acknowledged. Some of them are plainly compatible with liberal democracies as they currently exist. Others are however more naturally associated with the concept of epistocracy. The idea of public reason, at least in conjunction with the TTM, thus fails to establish that an epistocratic regime would necessarily be illegitimate. This is a significant result.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Notes

What Riker calls “populism” should not be confused with the meaning of this word as it is nowadays used to characterize some political movements and ideas in Western liberal democracies, though some connections could probably be made. Within political science, Patty and Penn (2014) is a recent and balanced attempt to qualify Riker’s view by developing an account of political legitimacy acknowledging the results of social choice theory. However, this account is not a social choice theoretic one properly speaking and therefore follows a different path than the one I shall take here.

See Chirat (2022) for an insightful discussion of the market/democracy analogy in economics.

The political/ethical distinction that I am making here echoes a long-lasting controversy in social choice theory and welfare economics about the implications of the former for the relevance of the latter. From the outset, Arrow argued that his impossibility result also applied to the so-called “Bergson-Samuelson” social welfare functions. On the other hand, Bergson, Samuelson, and other welfare economists maintained that, as the two kinds of social welfare functions (the Arrowian and the Bergsonian ones) were not concerned with the same domains of choice, Arrow’s “political mathematics” had no bearing on how welfare economists represent ethical judgments on market outcomes. For an early attempt to settle the controversy, see Pollak (1979). Fleurbaey and Mongin (2005) provide an assessment essentially in favor of the welfare economists, while downplaying in part the relevance of the political/ethical distinction. See also Igersheim (2019) for an historical account of the controversy.

What I call ethical social choice theory is sometimes presented as a competitor to the social contract approach to justice and equity issues, e.g., Sen (2009).

This is precisely at this point that Arrow makes the suggestion that his impossibility result also applies to the social welfare functions of welfare economics, sparking the controversy I am alluding to in footnote 3 above.

The TTM is normative because it makes a claim about the properties of the judgments to be aggregated. One may of course disagree that in a healthy democratic polity, people ought to vote based on their “social preferences.” In this paper, I am concerned with uncovering the implications of taking this normative model seriously for democracy.

The preferences of an agent i are single-peaked if and only the social states can be ordered along a line in such a way that if x is i’s preferred state, for any state z that is on the right or on the left side of x on the line, z is strictly lower in i’s ranking and, for any state y located between x and z on that line, we have \(x{\succ }_{i}y{\succ }_{i}z\), with \({\succ }_{i}\) the asymmetric and transitive relation of strict preference. Formally, single-peaked preferences are a restriction on the domain over which an Arrowian social welfare function is defined and thus correspond to a relaxation of the axiom of unrestricted domain.

The concept of (political) legitimacy is a contentious one. The rest of the discussion will proceed based on the following generic definition: a social decision is legitimate if and only it can be justifiably enforced through coercive means with respect to all members of the relevant population. Such a definition is agnostic on whether legitimacy exclusively depends on the procedure or is also responsive to the content of the social decision.

See also for instance Downs’s (1962) account of the role of public interest in a democracy. Downs suggests that voting behavior results from the articulation by citizens of their personal interests with their conception of the public interest. The view I shall defend based on the idea of public reason shares a lot with Downs’s account.

The literature on this issue has been growing fast recently. See for instance particular Gaus (2011), Thrasher and Vallier (2015; Kogelmann and Stich (2016); Kogelmann (2019); Chung, 2019, 2020a). See however Weithman (2011), Hadfield and Macedo (2012) and Quong (2010) for a defense of Rawls’s account.

See Anonymous for an account of interpersonal comparisons of goodness in a similar framework.

An anonymous referee has suggested an alternative definition more in line with Gaus’s (2012: 319) account of public justification. On this alternative definition, a social alternative x would be justified if it is ranked above the threshold of “blameless liberty” (i.e., a situation where no moral rule applies) by every social evaluation function in F*. The reason I prefer the definition given in the main text is twofold. First, Gaus is concerned with the justification of moral rules while I am more generally interested in the justification of social states. The notion of “blameless liberty” is harder to make sense of in this last case. Second, suppose that some state x is ranked above the threshold of blameless liberty by all social evaluation functions in F* but never first. Then, when comparing x with another social alternative y that is ranked first by at least one function F in F*, all members of the public will agree that F gives a reason to prefer y to x. More generally, a social state x that is not ranked first by any function in F* is always “defeated” by at least one other state that is preferred by at least one function in F* in the sense that there is always a reason to prefer an alternative state y to x. Note however that the main point made in the paper remains valid if we opt for the alternative definition. The choice between the two definitions is therefore more a matter of convenience than substance here.

See Taylor (2005: 23) for a formal definition of oligarchic rules, as well as other voting rules. Note that one of the proofs of Arrow’s theorem precisely consists in showing that, under the conditions imposed by Arrow, the existence of a decisive group of voters entails the existence of a dictator – the impossibility indeed follows from the fact that the set of voters is such a group.

See Kugelberg (2022) who argues that this more particularly creates troubles for “public reason proceduralism.”

This applies to the criteria one may want to impose to social evaluation functions and political decision rules, but also to their informational basis. For instance, while it may be legitimate to license or even to require interpersonal comparisons of utility for the former, there are reasons to consider that the latter should not depend on such comparisons in any form.

More than one characteristic can refer to a decision rule if we allow for several orders of decision rules, i.e., higher-order decisions rules that select lower-order decision rules. The idea Arrow is hinting at is then that there should be as many orders of decision rules as needed to reach unanimity at some level. Arrow (1963: 90) suggests that such a unanimous agreement is “implicit in every stable political structure.” In contrast, following convergence public reason theorists like Gaus (2012), I do not think that such unanimity is required to establish the legitimacy of social choices. Because of that, it does not add anything to the analysis to allow for decision rules of different orders.

Note that Kogelmann (2017) does not consider the case where preferences are also defined over decision rules. But the indeterminacy problem he identifies is of the same nature: the more people’s preferences are diverse (whether they order or not decision rules), the less likely are the conditions for an agreement over a decision rule to be met.

This result holds for the single-peaked restriction, but the single-peaked restriction and the never-worse restriction are actually equivalent.

The trivial case is of course the one where X has three components and one (or two) of them is not ranked first by any decision rule \(F\in {\varvec{F}}^{\varvec{*}}\). In general, never-worst is satisfied if a social alternative is ranked among the two best by every member of the public – this is only a sufficient, not a necessary condition though.

Consider for instance Acemoglu and Robinson’s (2005) account of the transition from dictatorship to democracy and the converse. Their model has two types of players – the elites and the citizens – with marked different preferences over the political regime. Elites prefer a dictatorial regime as it permits to maintain a relatively low level of taxes while citizens have a preference for a democratic regime that empower them to raise the level of taxes.

This is actually what some proponents of an “epistemic” defense of democracy are assuming when they rely on mathematical theorems as Condorcet’s jury theorem. These theorems typically assume that there is a true answer to a problem to be found, or at least that answers can be objectively ordered according to their “truthiness.” Then, providing that additional assumptions are satisfied (such as the kind of dispersion of opinions around the “true” one or their independence), these theorems show that increasing the number of voters and/or the diversity of their opinions increase the likelihood that the social choice will be the correct one. Maybe could we imagine proving a variant of these theorems applying to the TTM where the social choice correctly reflects the public interest if and only if it selects a social alternative belonging to the set X*. This is a possibility that I cannot explore here.

Alternatively, if we consider that the “general will” is automatically publicly justified, then that means that the majority rule does not track it properly, at least in practice, given what we know of voters’ behavior.

A good example is given by the French “Convention citoyenne pour le climat” that, for one year, has gathered randomly chosen citizens. With the help of experts, these citizens had the task to produce propositions of law regarding climate and the ecological transition. The law “climat et résilience” enacted the 22 August 2021 is partially grounded on the propositions of the Convention.

This depends on whether we use of strong or weak definition of preferences over decision rules, as defined in Sect. 5. If the latter, social alternatives with democratic decision rules may be ranked above elitist ones and the social ordering still be publicly admissible.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge University Press.

Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2016). Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton University Press.

Arrow, K. J. (1963). Social Choice & Individual Values. Yale University Press.

Brennan, J. (2016). Against democracy. Princeton University Press.

Brennan, J. (2022). Does Public Reason Liberalism Rest on a Mistake? Democracy’s Doxastic and Epistemic Problem. In E. Edenberg, & M. Hannon (Eds.), Political epistemology. Oxford University Press.

Chirat, A. (2022). Démocratie de la demande versus démocratie de l’offre : reconstruction et interprétation des analogies démocratie-marché. Œconomia. History, Methodology, Philosophy, no. 12–1 (March): 55–91.

Chung, H. (2019). The instability of John Rawls’s ‘Stability for the right reasons’. Episteme, 16(1), 1–17.

Chung, H., and Brian Kogelmann (2020). Diversity and rights: A social choice-theoretic analysis of the possibility of public reason. Synthese, 197(2), 839–865.

Chung, H. (2020a). The Well-Ordered Society under Crisis: A Formal Analysis of Public Reason vs. convergence discourse. American Journal of Political Science, 64(1), 82–101.

Dasgupta, P. (2021). The perils of Cosmopolitan Intellectualism. Society, 58(5), 416–423.

Downs, A. (1962). The public interest: Its meaning in a democracy. Social Research, 29(1), 1–36.

Fleurbaey, M., and Philippe Mongin (2005). The News of the death of Welfare Economics is greatly exaggerated. Social Choice and Welfare, 25(2), 381–418.

Gaus, G. (2011). A tale of two sets: Public reason in Equilibrium. Public Affairs Quarterly, 25(4), 305–325.

Gaus, G. (2012). The Order of Public Reason: A Theory of Freedom and Morality in a Diverse and Bounded World. Reprint edition. Cambridge New York,NY: Cambridge University Press.

Gibbard, A. (1973). Manipulation of Voting schemes: A general result. Econometrica, 41(4), 587–601.

Hadfield, G. K., and Stephen Macedo (2012). Rational reasonableness: Toward a positive theory of public reason. The Law & Ethics of Human Rights, 6(1), 7–46.

Harsanyi, J. C. (1953). Cardinal Utility in Welfare Economics and in the theory of risk-taking. Journal of Political Economy 61.

Harsanyi, J. C. (1955). Cardinal Welfare, Individualistic Ethics, and interpersonal comparisons of utility. Journal of Political Economy, 63(4), 309–321.

Igersheim, H. (2019). The death of Welfare Economics: History of a controversy. History of Political Economy, 51(5), 827–865.

Kogelmann, B. (2017). Aggregating out of indeterminacy: Social Choice Theory to the rescue. Politics Philosophy & Economics, 16(2), 210–232.

Kogelmann, B. (2019). Public reason’s Chaos Theorem. Episteme, 16(2), 200–219.

Kogelmann, B. (2023). In defense of (Limited) Oligarchy. Public Affairs Quarterly, 37(4), 352–370.

Kogelmann, B., & Stich, S. G. W. (2016). When public reason fails us: Convergence discourse as blood oath. American Political Science Review, 110(4), 717–730.

Kugelberg, H. D. (2022). Social choice problems with public reason proceduralism. Economics & Philosophy, 38(1), 51–70.

List, C. (2006). The discursive dilemma and public reason. Ethics, 116(2), 362–402.

Mill, J. S. (2015). On Liberty, Utilitarianism, and other essays. Oxford University Press.

Mongin, P. (2001). The Impartial Observer Theorem of Social Ethics. Economics and Philosophy, 17(02), 147–179.

Patty, J. W., & Elizabeth Maggie Penn. (2014). Social Choice and Legitimacy: The possibilities of impossibility. Cambridge University Press.

Pollak, R. A. (1979). Bergson-Samuelson Social Welfare Functions and the theory of Social Choice*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 93(1), 73–90.

Quong, J. (2010). Liberalism without perfection. OUP Oxford.

Quong, J. (2018). Public Reason. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Spring 2018. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of Justice. Oxford University Press.

Rawls, J. (1993). Political liberalism. Columbia University.

Rawls, J. (1997). The idea of public reason revisited. The University of Chicago Law Review, 64(3), 765–807.

Riker, W. H. (1988). Liberalism against populism: A confrontation between the theory of democracy and the theory of Social Choice. Reissue édition.

Satterthwaite, M. A. (1975). Strategy-Proofness and Arrow’s conditions: Existence and correspondence theorems for Voting procedures and Social Welfare functions. Journal of Economic Theory, 10(2), 187–217.

Sen, A. K. (1970). Collective Choice and Social Welfare. Holden-Day.

Sen, A. K. (2009). The idea of Justice. Harvard University Press.

Taylor, A. D. (2005). Social Choice and the mathematics of Manipulation. Cambridge University Press.

Thrasher, J., and Kevin Vallier (2015). The fragility of Consensus: Public reason, Diversity and Stability. European Journal of Philosophy, 23(4), 933–954.

Weithman, P. (2011). Why political liberalism? On John Rawls’s political turn. OUP USA.

Weymark, J. (1991). A reconsideration of the Harsanyi-Sen debate on utilitarianism. In J. Elster, & J. Roemer (Eds.), Interpersonal comparisons of well-being (pp. 255–320). Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this article has been presented in the INEM conference held in Venice in May 2023 and in the AFSE Conference held in Paris in June 2023. I thank the participants of these events for their comments, more particularly Herrade Igersheim for a fruitful discussion on some aspects of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H. wrote the full manuscript and has done the full research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hédoin, C. Public reason, democracy, and the ideal two-tier social choice model of politics. Const Polit Econ 35, 388–410 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-024-09437-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-024-09437-0