Abstract

Just as its constitutional development is characterised by frequent change and substantial concentration of power, the Latin American and the Caribbean area is known to host some of the most corrupt countries of the world. A group of countries such as Chile, Barbados and Uruguay, however, report levels of corruption similar to those displayed by most European countries. We ask whether the concentration of power in the executive, as well as in the national parliament in this particular region, affect how corrupt a society is. Using panel data from 22 Latin America and Caribbean countries from 1970 to 2014, we find that constitutional power concentration is in fact a determinant of corruption. Yet, the constitutional provisions allocating powers of government appear only to be consistently important when parliament is ideologically fractionalised.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

“It is not just the bad people who effect corruptionbut the institutions that make it possible” LessigL. (2011). Republiclost: How money corrupts congress and a plan to stop it. New York: Hachette

1 Introduction

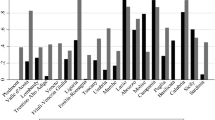

The Latin American and the Caribbean areas are known to host some of the most corrupt countries of the world. Bolivia, Nicaragua and Venezuela consistently experience high levels of corruption, similar to levels reached in Bangladesh and large parts of Sub-Saharan Africa. Yet, Barbados and Chile have traditionally experienced low corruption levels similar to those in Northern European countries, while Uruguay is about as corrupt as those in Southern Europe.

Despite differences in nature, context, and political dynamics, corruption—typically defined as the abuse of public power for personal gains—is present in all governments. A long list of studies has therefore emerged that attempt to find causal explanations of corruption (Ades and Di Tella 1999; Treisman 2002) and its detrimental effects on economic development and growth, as well as a number of features of social development (Rose-Ackerman 1999; World Bank 2001; Gupta et al. 2002; Bjørnskov and Freytag 2016). Although there is an evident relationship between corruption and particular differences in political institutions, relatively few papers have empirically studied this connection (Montinola and Jackman 2002; Dreher et al. 2008) and even fewer have explored the links between corruption and different constitutional features.

Theoretically, constitutions play an important role in averting the risk of corruption by defining both rights and the allocation and concentration of discretionary power (cf., Klitgaard 1988). This is mainly achieved through the creation of a predictable institutional environment, setting clear and enforceable norms for individuals in positions of power as well as preventing the concentration of power in the hands of a single person or body through the creation of veto institutions (Buchanan and Tullock 1962). Constitutions help maintain stability within the political environment by constraining the actions of government and distributing power among its different branches. In addition, the balance of power between the executive and the legislature is formally defined by how constitutions structure the legislative process. In order to entrench these institutions, constitutions should be stable documents (Buchanan and Tullock 1962; Ordeshook 1992).

Compared to the European constitutional tradition where new constitutions and constitutional amendments are rare events, the constitutions of most Latin American countries are characterised by frequent change and instability.Footnote 1 Unstable constitutions may fail to constrain politicians, ultimately allowing them to ignore or change the existing rules in order to accommodate rent-seeking behaviour (Versteeg and Zackin 2016). Latin America and the Caribbean nevertheless offer a particularly suitable setting for empirically testing whether the concentration of power in the executive and the national parliament in different constitutions has any effect on the levels of political corruption. The region offers sufficiently frequent constitutional changes to be able to identify effects, and the countries in the region are so similar in culture, historical background and social norms that such characteristics cannot be important confounders. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, the connection between constitutional characteristics and corruption remains unexplored in the existing literature on corruption.

In this paper, we therefore ask whether the concentration of power in both the executive branch as well as national parliament affect how corrupt a society is. We theoretically focus on the concentration defined by the constitution, i.e. through the most basic institutional decisions, and on Latin America and the Caribbean as a region with both substantial variation in corruption and constitutional change. We hypothesise that societies that present a more even concentration of power between the executive and legislative branches, and that are characterised by strong ideological fractionalisation, i.e. of no de facto political concentration should experience lower levels of corruption. As such, our considerations also lead us to the new theoretical insight that such constitutional features may only provide binding constraints when complementary parts of the institutional framework and political situation provide for a competitive political environment.

To test to which extent the classical doctrine of separation of powers limits the levels of corruption within 22 Latin American and Caribbean societies, we rely on the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset, combined with constitutional information in the Comparative Constitutions Project (CCP) and a number of additional constitutions not covered by the CCP. Measures in V-Dem of overall corruption and judicial accountability allow us to follow de facto institutional changes over time. To track changes in the constitutional concentration of power, and thus the degree to which parliament and the executive branch are constrained by constitutional design, we rely on the Index of Parliamentary Legislative Influence (IPLI) developed by Bjørnskov and Voigt (2018) and we develop a similar Index of Executive Influence (IEI).

Although our findings reveal no significant average effect of the amount of power granted by the constitution to the national parliament on the levels of corruption, they provide evidence that an increase in the concentration of power in the executive branch combined with an ideologically fractionalised environment is associated with lower levels of political corruption and higher judicial accountability.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 presents our theoretical considerations based on a review of existing literature and introduces our central hypothesis. Section 3 describes the data, main variables, and the empirical methodology employed. Finally, Sects. 4 and 5 contain our main findings and a discussion of these results in the context of various alternative explanations. Section 6 concludes.

2 Theoretical considerations

Since James Buchanan and Geoffrey Brennan developed the contractarian view in constitutional political economy, the government-citizen relationship has commonly been studied from a principal-agent perspective (Buchanan 1975; Brennan and Buchanan 1985). In this context, the government takes the role of an agent, which citizens, as principals, interact with in order to obtain security, justice and public goods. The basis of the social contract is defined by constitutional, statutory and common law. In other words, citizens rely on constitutions to establish and simultaneously control a government (Buchanan and Tullock 1962). Constitutions include features such as separation of powers, de jure certainty of frequent elections, and the definition of veto institutions to create a predictable institutional environment that with time will not only constrain those currently in power, but also bind these characteristics across generations (Buchanan and Tullock 1962).

Becker (1968) argued that for corruption to become a substantial problem, two factors have to be present. First, it requires a government or civil service with sufficient discretionary power over the allocation of the principals’ (voters’) resources. For grand corruption or state capture—i.e. corruption among politicians, high judges and other high-level political decision-makers with the aim of affecting institutional and policy decisions—it is a problem of relatively unconstrained government power while petty or bureaucratic corruption is more a problem of bureaucratic influence (cf. Knack 2007). Second, the existence of corrupt dealings rests on a relative lack of a judicial oversight and sufficiently strong and politically independent judicial institutions (Padovano et al. 2003). Such institutions would otherwise enable the detection of attempts to abuse political power to obtain rents while judicial institutions under direct political control may be prevented from investigating corruption by political actors. The extent to which politicians are capable of capturing rents is, to a large extent, determined by both their personal interest and by the influence or power office holders have over central policy decisions (Congleton 2019).

Assessing the impact of constitutional differences on grand corruption is no simple task because changes in institutional design may be driven endogenously (Negretto 2014). For instance, political institutions influence the choice of fiscal instruments, as well as the incidence of corruption (Persson 2002), but they are themselves endogenous since they are chosen, in some way, by members of the polity (Aghion et al. 2004). An important aspect of institutional design is therefore how much society chooses to delegate unchecked power to its leaders. In this sense, constitutions determine the amount of discretionary de jure power allocated to different government branches, specifying who has the right to make decisions, which decisions cannot be made, and outlining which procedures allocate which powers under which circumstances. Although all liberal democracies rely on the principle of separation of powers, the concentration of power in the executive and the legislature varies depending on how the legislative process is structured by the constitution (Diermeier and Myerson 1999). In particular, the executive and the legislative branches have different powers and incentives in different political systems such as presidential versus parliamentary democracies. In addition, the outcomes of these systems rest on the degree to which veto players, as defined by the constitution, are able to align politically or constitute effective, non-partisan veto institutions.

In this paper, we focus specifically on how the different constitutions allocate power among these bodies but combine a constitutional view with the degree to which political actors may align politically and thus de facto eliminate their role as potential veto players. Our analytical starting point is that two conditions logically must hold if constitutional veto institutions are likely to be effective in upholding de facto separation of power: veto players have to be sufficiently powerful, and they cannot be politically aligned with other political majority actors. In other words, we focus on the apparent paradox that in order to keep powerful political interests in check, one needs sufficiently powerful political veto players. While the first condition is typically defined de jure by the constitution, the second is shaped by ordinary politics.

2.1 Balancing institutional powers

In theory, the right balance of power among executive and legislative branches should allow for a conflict of interests so that each body prevents the other from abusing its power. The body in charge of maintaining the balance of power within this constitutional setting is the judicial branch. Characterised by its formal independence from the other two bodies, the judiciary is charged with preserving the integrity of the legal system, upholding the abstract concept of justice and avoiding the rent seeking and interest group pressures that corrupt the activity of the other two branches (Buchanan and Tullock 1962). When the constitution contributes to greater concentration of discretionary power, it also strengthens the incentives for the holders of specific powers to further their own interests without being held accountable by other government bodies (Buchanan and Tullock 1962; Treisman 2007). Political institutions with strong presidents and relatively weak parliamentary leaders provide one such example where power concentrated in the executive may arguably cause more corruption (cf. Gerring and Thacker 2004).

Conversely, when the constitution creates effective competition among agents, the implied checks and balances constrain the amount of transfer activity that can take place (Klitgaard 1988). Such transfers can both include direct support for groups favoured by specific political actors, and they can include direct transfers created by economic policy, unequal access to institutions such as the judiciary, and by regulatory decisions. Effective de jure separation of powers and thus limited concentration of discretionary power in either the executive or the legislature would—in a strictly constitutional analysis—reduce the incidence of corruption. Yet, for such a situation to create de facto separation of powers requires that sufficient power is actually concentrated in the vetoing political actors. Contrary to simple intuition, separation of powers therefore rests on sufficient concentration of power, but in separate actors.

2.2 Political concentration

However, as emphasised by a growing literature, the de jure institutional status may not always reflect the de facto separation of powers, institutional independence or power concentration (Ginsburg and Melton 2014; Foldvari 2017). Apparent competition can take different forms, not all institutional competition affects the de facto concentration of power and while constitutionally defined veto institutions ideally constrain political corruption by limiting the discretionary influence of potentially corrupt agents, such de jure institutions may not have de facto importance (Voigt 2013). We emphasise two types of mechanisms that may either lead constitutional power concentration to be ineffective or cause it to only be effective under specific political conditions.

First, when constitutions are unstable, veto institutions do not become entrenched, fail to prevent actors from circumventing the constitution and may de facto enable them to entirely ignore those provisions (Versteeg and Zackin 2016). In other words, constitutional instability weakens principals’ ability to monitor and control agents holding positions of power and enables the creation of mechanisms to protect those who are corrupt. In such conditions, de jure limitations on political decision-making are unlikely to result in de facto limits. This may be particularly relevant in the context of Latin America and the Caribbean where constitutions have been amended and replaced much more frequently than in Europe and most parts of Asia; in a number of cases, voters have even expressed their support for removing these constitutional mechanisms (Acemoglu et al. 2013). In addition to ensuring high levels of effective concentration of power, a number of authors have argued that the survival of authoritarian regimes in Latin America could not have been possible without the collaboration of judges (e.g. Hilbink 2007). As mentioned above, the judiciary plays an important role in ensuring the accountability of the political system. However, this is only possible if the judiciary is truly independent, or in other words, free from incentives to collude with other branches and from direct political control (Salzberger 1993). Which mechanisms exist for holding judges accountable is thus another factor we account for in this paper. Overall, these complications are more frequent in Latin America and the Caribbean and may decouple any relation between constitutional power concentration and the de facto incidence of political corruption.

Second, we argue that the political situation is likely to affect the degree to which principals can hold actual political actors and decision-makers accountable. In particular, if all decision-makers are politically aligned, the constitution may include as many veto points as possible without having any certain effect. In other words, as Henisz (2002) argues, de jure veto institutions are only likely to be effective when veto players not only have the constitutionally defined option of blocking particular decisions, but also have a juridical or political incentive to apply their blocking power. As such, we expect that the constitutional de jure separation of powers is most effective in constraining political corruption when it is accompanied by a situation of de facto political non-alignment, i.e. when different political actors with some veto strength represent different interests.

However, judging when that condition is likely to hold is not a simple matter. Multiple actors may often represent similar interests, implying that one cannot merely assess the degree of fractionalisation in parliament. In addition, fractionalisation can lead to severe rent-seeking problems, including corruption, when it results in extensive logrolling (cf. Uslaner and Davis 1975; Tullock 1981; Aidt 2019). If parliament is fractionalised, i.e. there is apparent non-alignment, extensive logrolling is likely to lead to even more political corruption than a situation in which legislative power is concentrated such that the incumbent government does not need to logroll. As such, a situation of de facto political non-alignment requires at least some level of fractionalisation in parliament and the absence of likely logrolling. In the following, we argue that such a situation is most likely when parliament is ideologically fractionalised, i.e. that ideologically different and potentially antagonistic parties are sufficiently equally represented in parliament.

2.3 Theoretical expectations

Overall, our thesis thus is that an effective separation of powers partially rests on how the constitution defines the concentration of power in the executive and legislative branches. Yet, we expect this to only have limited influence if not accompanied by a de facto situation of political non-alignment. This second condition must hold for de jure veto players to act effectively, as they otherwise have no political interest in exercising their veto power. The de jure constitutional provisions and de facto non-alignment may thus be complements in shaping problems of political corruption.

In other words, we argue that identifying the relation between the balance of power granted by the constitution and corruption, in addition to testing one of the basic principals in liberal democracies, may also offer a unique opportunity to identify a policy option to combat political corruption. In the following, we focus on the Latin American and Caribbean given the extensive variation of the levels of corruption observed across the region in addition to its unusual constitutional development. Compared to the European constitutional tradition, where new constitutions and constitutional amendments are rare events, the constitutions of most Latin American countries are characterised by frequent change and instability. According to the Comparative Constitutions Project, Ecuador has introduced ten new constitutions since 1950 and the Dominican Republic has introduced seven, while Mexico has introduced new amendments to its constitution at least once most years since 1917 (Elkins et al. 2009). Although only implementing two new constitutions, Brazil has amended its current constitution 92 times since 1988, and at least once in 45 years since 1950. On average, Latin American constitutions are substantially amended every 5 years and replaced every 10 to 15 years. This specific context allows us to capture changes in the concentration of power over time in a large number of constitutions, combined with changing de facto fractionalisation of parliamentary interests.Footnote 2

However, it bears noting that while constitutionally defined veto institutions ideally constrain political corruption by limiting the discretionary influence of potentially corrupt agents, such de jure institutions may not have de facto importance (Voigt 2013). Specifically, when constitutions are unstable, veto institutions do not become entrenched and fail to prevent actors from circumventing the constitution and may de facto enable them to entirely ignore those provisions (Versteeg and Zackin 2016). In other words, constitutional instability weakens principals’ ability to monitor and control agents holding positions of power and enables the creation of mechanisms to protect those who are corrupt.

We then ask whether de jure limitations on political decision-making also result in de facto limits. In addition to ensuring high levels of effective concentration of power, a number of authors that have argued that the survival of authoritarian regimes in Latin America could not have been possible without the collaboration of the judges (e.g. Hilbink 2007). Which mechanisms exist for holding judges accountable is thus another factor we account for in this study. Finally, we argue that the political situation is likely to affect the degree to which principals can hold actual political actors and decision-makers accountable. In particular, if all decision-makers are politically aligned, the constitution may include as many veto points as possible without having any certain effect. As Henisz (2002) argues, de jure veto institutions are only likely to be effective when veto players not only have the constitutionally defined option of blocking particular decisions, but also have a juridical or political incentive to apply their blocking power.

As such, we thus expect that the constitutional de jure separation of powers is most effective in constraining political corruption when it is accompanied by a situation of de facto political non-alignment. Hence, we argue that identifying the relation between the balance of power granted by the constitution and corruption, in addition to testing one of the basic principals in liberal democracies, also offers a unique opportunity to identify a policy option to combat political corruption.

3 Data and methodology

To capture how much political actors manipulate the instruments of the state for their own personal benefit, we use as our main outcome measures two indices from the Varieties of Democracy project (Coppedge et al. 2016). The first measure allows us to account for overall political corruption, since the index results from the average of the equally weighted assessments of four distinct types of corruption that cover both different areas and levels of the polity realm: corruption in the (1) public sector; (2) the executive branch; (3) the legislative branch; and (4) the judiciary. We therefore mainly identify consequences of the constitutional concentration of power on what is often termed either grand corruption or state capture, which we treat as a feature of government organisations (Banfield 1975; Knack 2007). Given the evidence, especially in Latin America, of judges collaborating with authoritarian regimes (Hilbink 2007) by supporting them in pursuing their agendas, we also include a direct measure of judicial accountability. This index captures the likelihood that judges are removed from their posts or otherwise disciplined if they are found responsible for serious misconduct. We thus test if variation in the amount of power concentrated in the other two branches of government has an effect on judicial accountability and thereby an indirect effect on corruption. This measure also comes from the V-Dem project database.

To account for the actual concentration of power granted by the constitution, we rely on the Index of Parliamentary Legislative Influence (IPLI) developed by Bjørnskov and Voigt (2018) and develop our own similar Index of Executive Influence (IEI). Both indices are coded based on information in the Comparative Constitutions Project (CCP), which we update and expand in two ways. We first start with the available data and expand them based on whether or not amendments change any of the 14 provisions included in either index.Footnote 3 Second, we code several additional constitutions not included in the CCP, mostly from small Caribbean island states. For each element in the indices, listed in Tables 1 and 2, we code a score of 1 when the legislature/executive has actual power, .5 if the provision is uncertain, and 0 if the legislature/executive does not have actual influence on the topic. The final IPLI and IEI are simple averages across the 14 components capturing the degree of influence that the legislature/executive has on central policy elements. These indices are available for 42 countries in the region of which 22 are covered by the V-Dem dataset.Footnote 4

In order to assess positions in the policy spectrum, we use the ideological categorisation of political parties behind the government ideology in Berggren and Bjørnskov (2017), which we update to include the most recent years and more countries in our region. Each party in parliament is coded on a simple five-step scale, capturing their ideological preferences for economic policy and institutions: − 1 corresponds to communist and unreformed socialist parties; − .5 denotes modern socialist parties; 0 are modern social democrat and non-ideological parties; .5 are conservative parties, while we reserve a score of 1 for the very few parties in Latin America and the Caribbean with a classical liberal background. As such, the measure does not necessarily capture other dimensions of political ideology than those associated with classical positions on economic policy and redistribution, regulatory activity, and property rights protection (cf. Poole and Rosenthal 2011).

We use these party categorisations to develop a measure of ideological fractionalisation, which can be interpreted as a proxy for the probability that two randomly drawn representatives from the legislature will be from different parties and of different ideological convictions. In other words, it is essentially a proxy for the lack of political and ideological alignment in parliament and thus also a proxy for the formal strength of purely political veto players. The measure is a standard Herfindahl-Hirschmann index, with each party share of seats in parliament weighted with the party’s ideological distance to the average position in parliament. The index is thus the sum of squares of all parties’ seat share in parliament (or the lower house of parliament) times its ideological distance to the average position. As such, the maximum attainable index is a situation with two parties – one far left and one far right—that each hold half of the seats in parliament. In this situation, the index will be (2 * .5)2 = 1.

In the tests in the following, we furthermore interact the IPLI and IEI (respectively) with ideological fractionalisation, which allows us to assess whether the de jure constitutional concentration of power has different effects when the ideological preferences represented in parliament are more or less diverse. We also add Berggren and Bjørnskov’s (2017) simple measure of government ideology, which is the seat-weighted average ideological position of parties in government. In additional tests, we interact with the government ideology index and with democracy in order to test alternative explanations.

As mentioned in the previous section, political institutions are to some degree endogenous and so may be their influence on constitutional design. We address this analytical problem by further including a set of a priori necessary control variables to account for effects on corruption beyond the relative bargaining power of either of the branches. A number of these variables have been highlighted in previous research as determinant characteristics leading to different institutional choices (cf. Aghion et al. 2004). Although there is no clear consensus on the causal direction of effects, the existing literature on rent-seeking and corruption finds evidence of an unambiguously negative association between trade and corruption. Most of existing studies argue that it reflects a negative impact of trade on corruption (Ades and Di Tella 1999; Gatti 1999). However, some studies have also emphasised the possibility that openness could lead to more corruption, and that corruption could affect trade (Treisman 2002). Given this evidence, we include a variable that controls for the volume of trade in each country. We add the logarithm to real GDP per capita and the size of the population as simple controls of the size and performance of the economy; these data are all from the Penn World Tables (Feenstra et al. 2015). In addition, we also control for the existence of two chambers in the national legislature, as the existence of a bicameral legislature may, on the one hand, encourage the creation of internal veto player or supermajority rules. On the other hand, it could come to favour special interests (Diermeier and Myerson 1999). Finally, we additionally control for democracy, as it may make this process more difficult and less prone to rent seeking (Acemoglu et al. 2001; Treisman 2007). However, one should notice that limitations on politicians’ rents in weakly institutionalised democracies may favour bribery or the influence of elites on politicians through non-constitutional means (Acemoglu et al. 2013). We follow recent studies in using the dichotomous indicator from Cheibub et al. (2010), which is based on a minimalist conception of democracy. The data in the following are from Bjørnskov and Rode’s (2020) update of Cheibub et al. (2010).

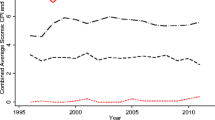

As noted above, countries in Latin American and Caribbean area display great variation in the observed levels of political corruption. Additionally, the region is characterised by substantial constitutional instability, and both anecdotal and empirical evidence suggest that under certain conditions, voters in these countries actively support the dismantling of checks and balances (Acemoglu et al. 2013). In Fig. 1, we illustrate the development over time of both corruption and the concentration of power granted by the constitution to the legislative branch, which is essentially the variation that gives us identification in the following.Footnote 5

All data are described in Table 5 in the “Appendix”. The variation over time illustrated in Fig. 1 is matched by similar variation in the IEI, and substantial variation across countries. As all estimates are obtained by two-way (country and annual) fixed effects OLS between 1970 and 2014 and across 22 Latin American and Caribbean countries, the variation that provides identification in the next section is the within-country variation over time in constitutional features and corruption. One must therefore also keep in mind that a large number of otherwise interesting characteristics such as federalism, coloniser identity and other historical influences, religion, social trust and culture, and the particular time countries became independent are fully captured by the fixed effects (cf. Treisman 2002).

4 Results

We report our main results in Table 3 where columns 1–4 display the results for the model for overall political corruption, while columns 5 and 6 show the results with the same baseline specification but using judicial accountability as the outcome variable.

Before turning to our main variables of interest, we briefly comment on the effects of our control variables. Our results indicate that larger countries with bicameral political institutions, tend to exhibit lower levels of corruption.Footnote 6 Similarly, democracies seem to have substantially less political corruption and higher levels of judicial accountability while higher levels of trade are associated with lower judiciary accountability and therefore, strongly associated with corruption.

Turning to our main estimates, although we find no significant effects on corruption from the amount of power granted by the constitution to the legislative (the IPLI), we find, in column 6, some evidence that an increase in the concentration of power of the executive branch (IEI), when interacted with the ideological fractionalisation of parliament, may be associated with better judicial accountability. However, we must emphasise that the estimate per se indicates the effect of concentration at no fractionalisation—a situation that only occurs in single-party dictatorships—and the estimate of fractionalisation per se indicates an effect at a zero value of the IEI, which we never observe (cf. Brambor et al. 2006). The potential effect of the IEI at sufficient levels of the fractionalisation index appears intuitive: an increase in effective political competition, as proxied by increasing ideological fractionalisation, constrains the de facto effective power of the executive to actions that have broad political backing. In such political circumstances, strong executive powers cannot be used to benefit narrow special interests or protect select parts of the bureaucracy. Conversely, countries with weak executive powers may lack effective oversight over the many potentially corruptible actors in such situations.

5 Are democracies different?

We nevertheless need to test whether these relatively weak findings are due to alternative explanations. As a set of final tests, we provide indications in Table 4 of whether our main results are stable to taking alternative explanations into account: whether ideological fractionalisation merely proxies for ideological differences or the existence of democracy, and whether the main findings are robust to excluding all observations from years in which countries were not fully democratic.

As a background for the first test, we note that it remains a possibility that ideological fractionalisation either merely picks up broad differences between democracies and autocracies when the relevant autocracies either do not allow multiparty parliaments or are in a position that leaves little parliamentary influence. Second, it may also be the case that it is not ideological fractionalisation per se that drives the results, but a particular ideological set-up of parliament. We deal with these problems by providing alternative interactions between the IEI/IPLI and a democracy dummy and government ideology, respectively.

An additional problem is that the literature on constitutions in general shows that constitutional constraints are often ineffective, as political actors can simply ignore them or are able to easily circumvent them (Feld and Voigt 2003; Bjørnskov and Voigt 2018). We therefore need, as a final test, to ask if the results in Table 3 are driven by autocratic episodes in our data. Similarly, we also test if the findings are driven by episodes in which countries have had no or only extremely weak veto institutions, as measured by Henisz’s (2017) PolCon III index. We address these questions by running an identical specification on the respective subsamples. For this, we define countries with actual veto institutions as the 75% of our sample that have a PolCon III index above .2.Footnote 7

We report these tests in Table 4.

We find that none of our main variables are consistently significant in the corruption regressions, with the exception of judicial accountability in columns 1–4. While the power of the executive (IEI) appears significant in columns 3 and 4, we must remind that the specifications include an interaction with fractionalisation such that the point estimate per se reflects the marginal effect at zero fractionalisation. As column 3 excludes all autocracies and column 4 excludes all societies with no or very weak veto institutions, a ‘pure’ effect of the IEI—i.e. one evaluated at zero democracy or veto institutions—will therefore be an out-of-sample prediction as these values are absent from the restricted samples.

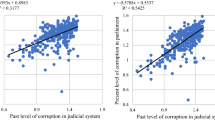

Conversely, in the right-hand side of the table where the dependent variable is judicial accountability and we restrict the sample to either only democratic observations or observations in which veto players had some influence, we find substantial evidence in columns 7 and 8, suggesting that executive concentration is positively associated with accountability when the parliament is sufficiently ideologically fractionalised (cf. the interaction term). In other words, allocating more power to the executive branch in the constitution is associated with improved institutional quality when that power is checked by effective veto politics in the form of substantial ideological differences in a democratically elected legislative branch. As a final illustration of the results, in Fig. 2 we therefore plot the marginal effects of the IEI/IPLI conditional on the level of ideological fractionalisation.

Effects at levels of ideological fractionalisation. Note: the figure illustrates the conditional estimates of IPLI and IEI with conditional 95% confidence intervals, calculated from the regressions in Table 3, columns 7 and 8

While concentration of power in parliament (the IPLI) is never significant—the 95% confidence interval denoted by the dotted grey lines in the figure always includes zero—we find evidence that above a fractionalisation level of .1, a concentration of power in the executive branch is significantly associated with higher levels of judicial accountability. A crucial side effect is that through its effects on judicial accountability, power concentration under such circumstances also limits the degree of political corruption. This is the case for approximately 20% of all observations in our data.

Finally, assessing the impact of constitutional power concentration on grand corruption is difficult because changes in institutional design may be endogenous (Negretto 2014). For this reason, a final potential worry is the problem that if corruption is as entrenched as to be endemic, one would suspect that it could affect both election outcomes and constitutional design (cf. Aidt 2003). As the coding scheme behind the Bjørnskov and Rode (2020) database implies that no society can be coded as democratic when election outcomes can be ‘bought’, we alleviate this worry by excluding all observations from autocracies in Table 4. Given that we obtain similar or stronger results than in the full sample, we believe we can reject the idea that corruption or a lack of judicial accountability is likely to substantially affect the ideological fractionalisation of parliament. In other words, we argue that this feature makes one of the two constitutive terms of the interaction between the IEI and fractionalisation plausibly exogenous such that the heterogeneous effects of constitutional concentration of power can be interpreted causally (Nizalova and Murtazashvili 2016). However, we are aware that if endemic corruption was to imply that corruption and/or judicial accountability or the deeper political causes of it could also affect constitutional design, the above interpretation might not necessarily apply to the average effect.

Yet, if reverse causality would be a main problem, we would also expect to find a general association between constitutional power concentration and corruption/judicial accountability, or at least an association in the relatively more corrupt countries in the sample. However, Figs. 5 and 6 in the “Appendix” do not indicate that there is such a general association between corruption or judicial accountability and the IEI. Further tests (not shown) also reveal that there is as little association in the half-sample with higher levels of corruption and worse judicial accountability. While this is not solid evidence of no endogeneity bias in Tables 3 and 4—we indeed do not believe that such evidence is likely to be produced with the data currently available—we argue that while we cannot rule out a minimal degree of endogeneity, it should not be a major concern, and that at least the heterogeneous effect of constitutional power concentration can be interpreted causally.

Overall, we thus find that constitutional power concentration is a determinant of corruption, and that the transmission mechanism runs through judicial accountability. Yet, the constitutional provisions allocating powers of government appear only to be consistently important under quite specific political conditions of full democracy and levels of ideological fractionalisation sufficient to create substantial de facto political competition. In other words, our findings are evidence of a complementary effect where high concentrations of power in the executive branch, combined with strong ideological fractionalisation in parliament, results in less corruption. In further tests reported in “Appendix” Table 6, we show that the same combination of constitutional and political conditions is also associated with substantially more independence from political influence of the judiciary. Conversely, we find no evidence that the effects are simply due to heavy-handed attacks on the judiciary, such that our findings could have been a reflection of political processes to dismantle democracy or similar extraordinary events. In other words, our findings are inconsistent with an interpretation in which the effects are due to political attacks on otherwise well-functioning institutions, but more likely reflections of systematic ills within the institutions. We therefore end the paper by briefly discussing the implications of these findings.

6 Conclusion

The Latin American and Caribbean area is generally known for high and persistent levels of corruption, although not all countries are equally corrupt and some have only quite minor problems. In addition to the significant variation in the levels of corruption, the region is characterised by a history of constitutional instability and high levels of effective concentration of power, which could both reduce the efficiency of its constitutional provisions and allow political actors to either circumvent or entirely ignore those provisions and diminish the credibility of veto institutions and judicial constraints.

In this paper, we uniquely combine these two topics—corruption and constitutional change—by asking whether changes in the constitutionally defined concentration of power in the executive branch and in the national parliament affect the levels of corruption in society. For our purpose, the Latin American and Caribbean area is ideal, as the combination of frequent constitutional change and substantial changes in political corruption allows us to estimate long-run effects of constitutions.

We begin the paper with a set of theoretical considerations that to some extent challenge a simple association between power allocation and corruption. The complicating factor is that the allocation of power in the executive branch can under some conditions alleviate potential corruption problems deriving from the legislative branch. As shown by Tullock (1981), these problems arise when actors in a fractionalised parliament seek political compromise by log-rolling, which gives much more room for manoeuvring for rent-seeking actors. One of several theoretical options thus is that constitutional power concentration in the executive branch can serve as an effective veto institution against substantial rent-seeking problems.

Although we find no significant direct effect of the amount of power granted by the constitution to the national parliament on the levels of corruption, our findings suggest a complementary effect: an increase in the concentration of power in the executive branch is associated with lower levels of political corruption and with higher judicial accountability. Yet, this effect only occurs when the legislature is characterised by sufficient ideological fractionalisation, i.e. when increased de jure concentration of power in the executive is checked by some level of de facto non-aligned political veto players. As such, one way of understanding these findings is that constitutional constraints on the executive and legislative branches of government are mainly effective when it is in the political interest of some actors with actual veto influence to enforce them. When this is not the case, we find no effects on corruption.

In other words, in our specific situation in Latin America and the Caribbean, it may require a fortuitous combination of de jure and de facto institutions to constrain corruption through formal institutional means. Corruption is known to be a sticky problem, which can easily persist for decades and can become endemic in some societies. Although this must remain speculative, one of the sources of this level of persistence may indeed be the rarity of achieving—wilfully or by accident—the right combination of institutions that reduce the level of political corruption. As such, our exploration of the question of the association between constitutional power concentration and corruption in this paper is only a first step towards understanding this element of the problem of corruption.

Notes

While European countries and the European offspring do occasionally implement constitutional amendments, they are much rarer than in Latin America. According to data in Elkins et al. (200), only 20 percent of all countries in Western Europe or similarly rich countries in North America and Australasia introduced a new constitution between 1970 and 2014. The average number of amendments in these countries during the same period was 12, and exploring these amendments, it is clear that most aim at defining existing constitutional rights more precisely. These numbers are dwarfed by, e.g., the 92 amendments to the Brazilian constitution since its implementation in 1988, the on average annual amendments to the constitution of Mexico, and the three new constitutions in the Dominican Republic since 1970. The typical country in Latin America and the Caribbean has implemented a new constitution every 15th year since 1950, making such implementation 11 times as likely as in Western countries.

Latin America and the Caribbean is distinct from Europe and the European offspring by having substantially more constitutional change. However, so is Africa and parts of Asia where Thailand for example has implemented 15 new constitutions since 1945. We nevertheless refrain from using data from other parts of the developing world, as African and Asian constitutional development is often characterised by the use of interim constitutions and the comparatively frequent cancellation of the constitution. By focusing exclusively on Latin America and the Caribbean, we thus avoid the problem of how to deal with the phenomenon of constitutional limbo.

In a large number of cases, all observations in the CCP are missing following constitutional amendments that were not coded. The data then reappear after either a new constitution is implemented or a major amendment is coded by the CCP team. We have filled in these missing values by reading all amendments in between observations and coding any changes within the amendments that concern the 14 provisions entering either index.

While the V-Dem dataset is quite comprehensive, it unfortunately does not include a number of the smaller countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. As such, even though our constitutional data are available for, e.g., the Bahamas, Belize and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, we cannot include these countries due to a lack of data on our outcome variables.

We also provide first indications of the association between corruption and the direction of the constitutional reforms in Figures A2 and A3 in the appendix, where we plot the association between the average corruption between 1970 and 2014 and the IPLI and EIE respectably. As the figures illustrate, the correlation between corruption and the IPLI and IEI are far from homogeneous.

Although we find significant effects of bicameral studies, we must warn against concluding too much on this basis. Because of the presence of country fixed effects, the effects are identified by a very small number of changes.

The PolCon index is in principle distributed between 0 and 1 although scores above .7 are rare. The index is composed of constitutionally defined veto structures, but corrected for whether actors within these structures are politically aligned or not. In perfectly unconstrained autocracies, the index is zero while we do observe some democracies with low scores, as potential veto players – upper chambers, high courts etc. – are politically aligned with the incumbent government. Within our sample, Colombia and El Salvador in the early 2000 s fall into this category.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91, 1369–1401.

Acemoglu, D., Robinson, J. A., & Torvik, R. (2013). Why do voters dismantle checks and balances? Review of Economic Studies, 80, 845–875.

Ades, A., & Di Tella, R. (1999). Rents, competition, and corruption. American Economic Review, 89(4), 982–993.

Aghion, P., Alesina, A., & Trebbi, F. (2004). Endogenous political institutions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 565–611.

Aidt, T. (2003). Analysis of corruption: A survey. The Economic Journal, 113, F632–F652.

Aidt, T. (2019). Corruption. In R. Congleton, B. Grofmann, & S. Voigt (Eds.), Oxford handbook of public choice (Vol. II, pp. 604–627). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Banfield, E. C. (1975). Corruption as a feature of governmental organization. Journal of Law and Economics, 18, 587–605.

Becker, G. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76, 169–217.

Berggren, N., & Bjørnskov, C. (2017). The market-promoting and market-preserving role of social trust in reforms of policies and institutions. Southern Economic Journal, 84, 3–25.

Bjørnskov, C., & Freytag, A. (2016). An offer you can’t refuse: Murdering journalists as an enforcement mechanism of corrupt deals. Public Choice, 167, 221–243.

Bjørnskov, C., & Rode, M. (2020). Regimes and regime transitions: a new dataset on democracy, coups, and political institutions. Review of International Organizations, 15, 531–551.

Bjørnskov, C., & Voigt, S. (2018). Why do governments call a state of emergency? On the determinants of using emergency constitutions. European Journal of Political Economy, 54, 110–123.

Brambor, T., Clark, W., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14, 63–82.

Brennan, G., & Buchanan, J. M. (1985). The reason of rules. Constitutional political economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buchanan, J. M. (1975). A contractarian paradigm for applying economic theory. American Economic Review, Papers & Proceedings, 55, 225–230.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143, 67–101.

Congleton, R. D. (2019). The political economy of rent creation and rent extraction. In R. Congleton, B. Grofmann, & S. Voigt (Eds.), Oxford handbook of public choice (Vol. I, pp. 604–627). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coppedge, M., Lindberg, S., Skaaning, S.-E., & Teorell, J. (2016). Measuring high level democratic principles using the V-Dem data. International Political Science Review, 37, 580–593.

Diermeier, D., & Myerson, R. B. (1999). Bicameralism and its consequences for the internal organization of legislatures. American Economic Review, 89, 1182–1196.

Dreher, A., Gaston, N., & Martens, P. (2008). Measuring globalization: Gauging its consequences. New York: Springer.

Elkins, Z., Ginsburg, T., & Melton, J. (2009). The endurance of national constitutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Feenstra, R. C., Inklaar, R., & Timmer, M. P. (2015). The next generation of the Penn world table. American Economic Review, 105, 3150–3182.

Feld, L., & Voigt, S. (2003). Economic growth and judicial independence: Cross-country evidence using a new set of indicators. European Journal of Political Economy, 19, 497–527.

Foldvari, P. (2017). De facto versus de jure political institutions in the long-run: a multivariate analysis, 1820–2000. Social Indicators Research, 130, 759–777.

Gatti, R. (1999). Corruption and trade tariffs, or a case for uniform tariffs. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 2216, the World Bank, Washington, DC.

Gerring, J., & Thacker, S. C. (2004). Political institutions and corruption: The role of unitarism and parliamentarism. British Journal of Political Science, 34, 295–330.

Ginsburg, T., & Melton, J. (2014). Does de jure judicial independence really matter? A reevaluation of explanations for judicial independence. Journal of Law and Courts, 2, 187–217.

Gupta, S., Davoodi, H., & Alonso-Terme, R. (2002). Does corruption affect income inequality and poverty? Economics of Governance, 3, 23–45.

Henisz, W. (2002). The institutional environment for infrastructure investment. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11, 355–389.

Henisz, W. (2017). The Political Constraint Index (POLCON) Dataset. Database and codebook, Accessed July, 2018 from, https://mgmt.wharton.upenn.edu/faculty/heniszpolcon/polcondataset/.

Hilbink, L. (2007). Judges beyond politics in democracy and dictatorship. Lessons from Chile. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klitgaard, R. (1988). Controlling corruption. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Knack, S. (2007). Measuring corruption: A critique of indicators in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. J Public Policy, 27, 255–291.

Montinola, G. R., & Jackman, R. W. (2002). Sources of corruption: A cross-country study. British Journal of Political Science, 32, 147–170.

Negretto, G. L. (2014). Making constitutions: presidents, parties, and institutional choice in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nizalova, O. Y., & Murtazashvili, I. (2016). Exogenous treatment and endogenous factors: Vanishing of omitted variable bias on the interaction term. Journal of Econometric Methods, 5, 71–77.

Ordeshook, P. C. (1992). Constitutional stability. Constitutional Political Economy, 3, 137–175.

Padovano, F., Sgarra, G., & Fiorino, N. (2003). Judicial branch, checks and balances and political accountability. Constitutional Political Economy, 14, 47–70.

Persson, T. (2002). Do political institutions shape economic policy? Econometrica, 70(3), 883–905.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. L. (2011). Ideology and congress. London: Routledge.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1999). Corruption and government, causes, consequences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Salzberger, E. M. (1993). A positive analysis of the doctrine of separation of powers, or: why do have an independent judiciary? Int Rev Law Econ, 13, 349–379.

Treisman, D. (2002). The causes of corruption: a cross-national study. J Public Econ, 76, 399–457.

Treisman, D. (2007). What have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-National empirical research? Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 211–244.

Tullock, G. (1981). Why so much stability? Public Choice, 37, 189–204.

Uslaner, E. M., & Davis, R. (1975). The paradox of vote trading: Effects of decision rules and voting strategies on externalities. American Political Science Review, 69, 929–942.

Versteeg, M., & Zackin, E. (2016). Constitutions unentrenched: Toward an alternative theory of constitutional design. American Political Science Review, 110, 657–674.

Voigt, S. (2013). How (not) to measure institutions. Journal of Institutional Economics, 9, 1–26.

World Bank. (2001). The World Bank annual report 2001: Year in review (English). Washington: World Bank.

Acknowledgements

We thank Roger Congleton, Peter Lewisch, Christoph Moser, Martin Rode, Paul Schaudt, Stefan Voigt, participants at the 2019 Danish Public Choice Workshop (Aarhus), the 2019 meetings of the European Public Choice Society (Jerusalem), the 2019 Beyond Basic Questions workshop (Kiel), and the 2019 conference of the European Association of Law and Economics (Tel Aviv), as well as two anonymous reviewers at this journal for helpful comments on earlier versions. Bjørnskov gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Jan Wallander and Tom Hedelius Foundation. Sáenz de Viteri would like to acknowledge the Asociación de Amigos de la Universidad de Navarra and Banco Santander for their financial support. Any remaining errors are of course entirely ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Viteri Vázquez, A.S., Bjørnskov, C. Constitutional power concentration and corruption: evidence from Latin America and the Caribbean. Const Polit Econ 31, 509–536 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-020-09317-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-020-09317-3