Abstract

It has been shown that both formal existence and actual use of direct democratic institutions have effects on a number of variables such as fiscal policies, quality of governance but also economic growth. Further, it has been argued that direct democratic institutions would not only have an impact on policy outcomes but influence citizen participation and attitudes toward politics. For the first time, these conjectures are tested in a large cross-country sample here. Overall, we do not find strong effects and some of the significant correlations are rather small substantially. In contrast to previous studies, voter turnout is not higher when direct democracy is available or used. Further, and also in contrast to previous studies, citizens do not express a greater interest in politics in countries with direct democracy institutions. Finally, they display lower trust in government and parties but not in parliament. These results shed some doubt on the hope that direct democracy would make for better citizens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Motivation

Direct democratic institutions significantly affect a number of economic outcomes such as government spending, government deficits and even total factor productivity [see, e.g., the survey by Matsusaka (2005)]. These effects could be called the outcome effects of direct democracy. Here, we ask whether direct democratic institutions have significant effects on political participation and attitudes toward politics. Voting on specific proposals regarding single issues could, e.g., lead citizen-voters to be better informed. It could further induce people to be more interested in politics and to spend more time discussing it with relatives, friends and workmates. We refer to these effects of direct democracy as participation—as opposed to outcome—effects. This is the first paper that systematically searches for such effects on a broad cross-country level.

The possibility that direct democratic institutions have an effect on various aspects of individuals’ participation in the political process has been alluded to by a number of authors. Butler and Ranney (1994, 18), e.g., conjecture: “Referendum voters, however ignorant and unsophisticated they may seem when measured against the theorist’s ideal citizens, seem nevertheless to be better informed and more sophisticated than voters in candidate elections.” Benz and Stutzer (2004) find evidence in favor of the conjecture that citizens in states with direct-democratic institutions are better informed than citizens in purely representative states. Some European states used referendums to pass the Maastricht treaty whereas others did not. Relying on Eurobarometer data, Benz and Stutzer find that citizens in countries with a referendum were indeed better informed both objectively (i.e. concerning their knowledge about the EU) as well as subjectively (i.e. concerning their feeling about how well they were informed). Their paper is one of very few papers that deals with the effects of direct-democratic institutions in a cross-country setting. More recently and based on 14 US elections that took place between 1978 and 2004, Schlozman and Yohai (2008) find only very modest effects of initiatives on political knowledge.

While Butler and Ranney expect referendum voters to be better informed than voters in candidate elections, they are pessimistic that direct democratic institutions will increase overall voter turnout (1994, 17): “In short, while the evidence is far from dispositive, little in recent experience supports the proposition that referendums increase voting turnout. There is no reason to suppose that the ready availability of referendums encourages other forms of participation.” A number of studies have since tested the relations between initiatives and voter turnout. Smith (2001) introduces a proxy for the salience of both initiatives and referendums and finds that more salient ballot choices are related with higher turnout. This would be particularly relevant in midterm elections. In their influential study, Smith and Tolbert (2004) compare initiative with non-initiative US states and find that the frequent use of initiatives has positive effects on voting levels, but also on civic engagement and confidence in government.

In their study, Tolbert and Smith (2005) use what has been termed the “voter eligible population” as turnout measure. Drawing on that variable, they find that initiatives significantly increase turnout not only in midterm but also in presidential elections. More recently, Donovan et al. (2009) find that independent voters (as opposed to partisan ones) are more aware of and interested in ballot measures in the midterm elections; this is not the case with regard to presidential elections. Tolbert et al. (2003) find that it is not only the sheer number of initiatives that increases turnout but also campaign spending. Again, Schlozman and Yohai (2008) pour some water into the wine by finding no effects of initiatives on voter turnout in presidential elections. Dyck and Seabrock (2010) find that increased voter turnout in ballot initiatives is a short-term effect which is not caused by a more favorable attitude regarding participation. To sum up: Smith and Tolbert (2004) found positive effects of initiatives on voter turnout, political participation as well as confidence in government. In a sense, they found that direct democracy makes for good citizens. Later studies, and in particular Schlozman and Yohai (2008), have poured lots of water into the wine. Using various ways to measure the number of initiatives and using different estimators, they are not able to find any of the significant effects that Smith and Tolbert found. In this paper, we are interested in taking this question beyond the US and ask whether direct democracy instruments are associated with higher voter turnout, more political participation and higher trust in government and other political actors in a cross-country setting.

In one of the rare papers analyzing the effects of direct democracy on a cross country level, Hug (2005) finds for a cross-section of 15 transition countries in Central and Eastern Europe that direct democratic institutions cannot explain variation in the confidence of various organizations such as government, parliament, the EU or the armed forces. In a panel for the years between 1990 and 1997 and covering the same set of countries, he does find some evidence that citizens are more satisfied with democratic development given that they have direct democratic institutions at their disposal. Dyck (2009) argues that direct democratic institutions—and their frequent use—undermine the possibility of politicians to present themselves as trustworthy which implies that more frequent use should be correlated with lower levels of trust in government. This is exactly what he finds with regard to trust in US state governments.

In summary, at least some papers have found a positive correlation between direct democratic institutions and (1) voter information, (2) voter turnout and civic engagement more broadly conceived, and (3) trust in government and other political actors. Almost all of these results have, however, been found with respect to single countries (mostly the United States) or, in case of cross-country settings, on the basis of a very limited number of countries. In this paper we ask whether any of these relations can be found in a cross-country dataset comprising up to 94 countries. In a previous paper on the economic effects of direct democratic institutions (Blume et al. 2009), we found that some of the effects are not due to the formal existence of direct democratic institutions but to their actual use. This is why we, here too, analyze both formal existence as well as actual use of direct democratic institutions.

Our main findings can be easily summarized: First, in most cases there is no measurable connection between participation and direct democracy, and when connections do appear, they are fragile. In contrast to previous studies, voter turnout is not higher when direct democracy is available or used. Second, in countries with direct democracy institutions, citizens do not express greater interest in politics. Third, in countries with direct democracy institutions, citizens express lower trust in government and political parties but not in parliament. We thus conclude that direct democracy institutions are no panacea to making for better citizens.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, a number of conjectures on why direct democratic institutions could have an impact on various aspects of political participation are developed. Since our emphasis in this paper is clearly on the empirics, this section mainly surveys the main theoretical arguments discussed in previous papers. Section 3 describes the underlying data and the estimation approach employed. Section 4 contains the estimation results and offers possible interpretations thereof. Section 5 concludes and describes possible next steps.

2 Some theoretical conjectures

Instrumentally rational citizens would practically never bother to vote as the likelihood that they will cast the decisive vote is almost zero. Since, however, voter turnout is consistently significantly higher than zero, this observation has also been coined “the paradox of voting” and has occupied public choice scholars for decades (Mueller 2003, Ch. 14 is a good overview over both the original result and the various strategies to mitigate it). But if it is irrational to vote, then it is also irrational to incur costs for being informed in the first place. Therefore, public choice scholars postulate the rationally ignorant voter.Footnote 1 If direct democracy is to increase voter turnout we need, hence, to establish two things: First, we need to show that more information makes it more likely—and rational—to vote. Second, we need to show that citizens are likely to acquire more information under direct democracy.

Matsusaka (1995) is an ingenious approach to resurrect the rational choice model of voting. Based on two observations, the model chooses to explain abstentions rather than votes. First, according to surveys, an overwhelming majority of citizens believe they ought to vote even if their candidate is certain to lose. Second, some citizens abstain because they have insufficient information to evaluate the candidates. The model now shows that it can be rational to abstain in case a citizen feels she has insufficient information about the candidates or parties’ platforms. Now, if citizens feel better informed as a consequence of direct democracy and its consequences such as intense public debates on particular issues, higher voter turnout might be the result.

It remains to be shown why citizens should be better informed under direct democracy in the first place. Various conjectures have been discussed. One consideration posits that getting informed about politics does not exclusively serve as an input in the production of a pure public good (the election result) but has some private good components: people who are well-informed about politics are more interesting to talk to, will be listened to over lunch conversations and so forth. If my reputation as an interesting lunch conversation partner depends on my being politically informed, I might have a rational interest in not being politically ignorant. Comparing countries that use direct democratic institutions with those that rely exclusively on representative elections, the overall number of elections will be higher in the former—and the investment into political competence is likely to yield higher payoffs too.

Smith (2001) argues that as ballot initiatives become more salient, the costs of acquiring information falls as citizens can gather it without much effort. He hypothesizes that turnout is positively correlated with the salience of both referendums and initiatives. But when salience is already high, the marginal effect is expected to be small. Smith (ibid.) expects this to be the case in presidential elections implying that—ceteris paribus—the effect of direct democratic institutions on voter turnout should be higher in midterm than in presidential elections. Further, if citizens frequently vote on policy issues, this might undermine the perceived importance of decisions taken by their representatives—and turnout might subsequently be lower.

The possible connection between campaign spending and voter turnout has been investigated by Cox and Munger (1989). They show that campaign spending can increase the pressure to vote. Given that overall campaign spending increases in the use of direct democracy institutions, this could be a complementary transmission channel leading to higher overall turnout.

Voting is only one form of political activity. Other forms include signing petitions, joining boycotts, participating in demonstrations and so forth. Quite generally, these forms of political activity are not easy to explain as they are subject to the problem of collective action first described by Olson (1965). Speculating about the possible relationship between direct democratic institutions and these forms of civic engagement leads to contradictory conjectures: on the one hand, one can argue that the increased political interest and awareness induced by direct democratic institutions should make other forms of political activity more likely. There would, thus, be a complementary relationship between the two. On the other hand, one can argue that the availability of established and well-respected forms of political participation such as initiatives and referendums should decrease the likelihood that people resort to alternative forms of political activity. There should, hence, be a substitutive relationship. As the relationship between these two kinds of political action is difficult to derive theoretically, an empirical test will be all the more important.

All these arguments try to remain within the standard framework of economics. Admittedly, not all of them are entirely convincing. Some economists try to modify the standard framework. Frey et al. (2004), e.g., propose that utility should not be confined to utility deriving from outcomes but should include utility deriving from (fair, good, adequate) procedures. People would not only value outcomes (what?) but also the process leading to outcomes (how?). Drawing on insights from psychology, Frey et al. argue that people have a sense of self and would value autonomy, relatedness, and competence. Being at the receiving end of hierarchies would produce procedural disutility, whereas voice, i.e. the capacity to stand up for one’s position, would be an element of a process that is perceived as fair just as participation increases (procedural) utility as it would enhance individuals’ perception of self-determination.Footnote 2

If direct democratic institutions give citizens a sense of “voice”, their utility from politics is expected to be higher than under purely representative democracy. This, in turn, should come along with higher levels of legitimacy accredited to the political system and possibly also higher levels of reported life satisfaction (aka happiness). Based on ten policy issues, Matsusaka (2010) reports that US states with direct democracy are around 18 % more likely than states without direct democracy to implement the preference of the majority as their policy. Direct democracy could, hence, indeed be a strong tool to mitigate the principal-agent-problem between citizens and government. This might, in turn, increase the overall legitimacy attributed to government.

Whether direct democratic institutions are indeed associated with higher levels of trust in political organizations such as government, parliament, and political parties is inquired into here. Theoretical predictions are, again, ambivalent. A straightforward argument claims that direct democratic institutions make governments more responsive to citizen preferences which could increase citizen trust in government. Dyck (2009) turns this argument on its head: every time an initiative is used, citizens become aware that politicians would shirk on them if they do not draw on initiatives. Dyck (2009, 6) argues that the mere existence of direct democratic institutions reminds citizens that politicians ought not to be trusted.Footnote 3 Every time direct democratic institutions are actually used, this suppresses the possibility of politicians to fulfill their obligations and thus reduces the likelihood that citizens will trust them. Previously, Citrin (1996) had argued that the initiative undermines the authority of elected officials, as they are constantly being questioned and circumvented.

Further, successful initiatives are not equivalent with their faithful implementation. Initiatives need to be implemented by government. Given that their content is not in accordance with the preferences of government, it is likely that they will be “stolen” as Gerber et al. (2001) have coined the phenomenon. If citizens experience this, their trust in government might further erode. Finally, assume that direct democratic institutions are conducive to higher levels of information regarding the political process. It cannot be excluded that better informed citizens display less trust as the higher level of information gives them little reason to trust politicians.

Matsusaka (2008) develops an argument to the contrary, hypothesizing that citizens, by removing contentious issues from their representatives, might perceive an improved ability to control them regarding the remaining issues. This could, in turn, be connected with a higher level of trust. Ex ante, the effects of direct democratic institutions on citizen trust in government are thus unclear and merit empirical analysis. Summing up, based on theoretical arguments, we do have reasons to expect direct democracy institutions to be associated with better informed citizens. Whether this translates into higher voter turnout, more frequent use of other forms of political participation and more trust in government is, however, not clear. An empirical test might, hence, shed light on these issues.

3 Data and estimation approach

In this section, we proceed in four steps. First, we present our data reflecting direct democratic institutions. Second, we discuss the variables proxying for various aspects of the political process. Third, we present bivariate correlations between our direct democratic variables and those variables proxying for the political process. Fourth, we propose our estimation approach.

3.1 Variables reflecting direct democratic institutions

The international IDEA handbook on direct democracy (2008) contains information on ten different aspects of direct democracy for up to 214 countries and territories. It reflects the situation as of January 2008. We use information for up to 94 countries only as other variables for the remaining countries are frequently lacking.

The handbook distinguishes between four different institutions of direct democracy, namely (1) referendums, (2) citizens’ initiatives, (3) agenda initiatives and (4) recall. Regarding referendums, the survey distinguishes between mandatory and optional referendums. It does not make a distinction between referendums and plebiscites. But it does make a distinction between agenda initiatives on the one hand and citizens’ initiatives on the other. An agenda initiative is defined as a direct democratic institution which “enables citizens to submit a proposal which must be considered by the legislature but is not necessarily put to a vote of the electorate” (IDEA 2008: 212). Hence, the citizen-voters are agenda-setters but not final decision-makers. This is different under citizens’ initiatives which are direct democratic institutions that allow “citizens to initiate a vote of the electorate on a proposal outlined by those citizens. The proposal may be for a new law, for a constitutional amendment, or to repeal or amend an existing law” (IDEA 2008: 213; italics in original). Under this institution, citizen-voters are, hence, both agenda-setters and final decision-makers.

Table 1 provides an overview over the possibilities of direct democratic institutions in our universe of 94 countries. According to the Handbook, referendums are possible in more than 2/3 of all countries covered. This number strikes us as very high. It is clearly higher than the percentage that we found in our previous study which was based on 88 countries.Footnote 4 We attribute the difference to the less restrictive definition employed by the authors of the Handbook. Yet, a couple of qualifications might be in order: Referendum results are binding in less than half of all countries (46.8 %. They are “partially binding” in another 21.3 %; not shown in the Table). In 10.6 % of all countries, referendums are restricted to proposed constitutional amendments. Interestingly—and nicely documenting the institutional heterogeneity regarding direct democracy—in another 8.5 % of all countries, referendums regarding constitutional amendments are not admissible. But in two out of three countries, referendums can apply to both constitutional and non-constitutional legislation. Information on bivariate correlations between the various institutions rounds up our quick overview over direct democratic institutions. Only 27 of our 94 countries combine all direct democratic institutions (i.e. mandatory referendums, optional referendums, initiatives), 16 countries rely on a mix of mandatory and optional referendums, but do not provide initiatives, 7 countries rely on a mix of optional referendums and initiatives, but do not provide mandatory referendums. This implies that societies do not make an all or nothing choice regarding direct democracy institutions, but choose a highly varied menu of them.

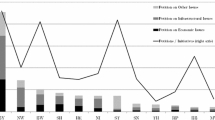

Our former study on the effects of direct democracy (Blume et al. 2009) shows that it is often the actual use of the various institutions—and not their legal foundation—that causes the effects. This is why we continue to group our variables into de jure variables on the one hand, and de facto variables on the other. Two databanks were used to construct the de facto indicators: the Search Engine for Direct Democracy and the databank provided by the Centre for Research on Direct Democracy in Aarau, Switzerland. Table 2 provides an overview over the frequency with which these institutions have been used between 1995 and 2006. The maxima of the first three institutions are all due to Switzerland. Regarding presidential plebiscites, Belarus, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Madagascar all organized three of them. Parliamentary plebiscites were most often called by the Polish parliament in the relevant period.

3.2 Variables reflecting the political process

In Sect. 2, a number of variables that could potentially be influenced by direct democratic institutions were briefly discussed, among them the degree of information that voters have, the degree to which they turn out at the election booth etc. Unfortunately, some of these variables are not readily available for a cross section. For our analysis, we rely overwhelmingly on results reported in the fifth wave of the World Values Survey (2008) which covers numerous aspects that are of interest here. 10 out of our 12 variables used here are from the World Values Survey. Table 3 offers summary statistics for the key dependent and independent variables.Footnote 5

These ten variables can be grouped into three different areas, namely (1) voter turnout, (2) interest in politics and (3) institutional trust. Voter turnout is our first dependent variable. Turnout information is also provided by IDEA (turnout data are based on all elections that took place between 2000 and 2008). We use turnout either as a percentage of registered voters or, alternatively, as a percentage of the voting age population. Both measures have advantages and disadvantages. The variable registered voters automatically controls for the exclusion of entire groups from elections; on the other hand, having mastered the hurdle of being registered is likely to increase the probability to participate in elections. The bivariate correlation between the two variables is r = 0.65.

We are interested in ascertaining whether countries with direct democratic institutions make citizen-voters more interested in politics. To test whether this is the case we rely on a question from the World Values Survey that asks “How interested would you say you are in politics?” To operationalize, we summed the percentages of those who answered “very interested” and “somewhat interested”. It turns out that Argentines are least interested in politics whereas Thais are most interested.

Direct democratic institutions might not only make people more interested in politics, but might also make them discuss political matters more frequently. The 1999–2002 wave of the World Values Survey contained a question “When you get together with your friends, would you say you discuss political matters frequently, occasionally or never?” Here, we took the percentage of those who answered “frequently”. Political matters are discussed least frequently in Singapore and most frequently in Israel.

But the effects of direct democratic institutions might be even more far-reaching. Compared to pure representative democracy, they allow for one additional kind of activity, namely voting on concrete issues (instead of on persons and/or parties alone). This might be accompanied with additional political activities such as joining boycotts, or attending peaceful demonstrations. The World Values Survey asks whether the surveyed have participated in any of these activities in the last 5 years. Romanians are least likely to participate in boycotts whereas Swedes are most likely to do so. Participation in demonstrations is least likely in Singapore and most likely in France.

If direct democracy leads people to discuss political matters more frequently or even to participate in additional political activities, it could also have an impact on the level of trust that citizens have in their government, the political parties, or parliament. To test whether the confidence in government, political parties or parliament is correlated with direct democratic institutions, we use the percentage of those who answered “a great deal”. Now, people in Macedonia display the lowest level of trust in government, trust in parties is lowest in Germany, and trust in parliament lowest in the Netherlands. Interestingly, Bangladeshis are those who trust all of these most.

Finally, having the possibility to rely on direct democratic institutions and (or) frequently resorting to them might have an impact on the citizens’ perception of how democratically their country is governed overall. The corresponding question from the World Values Survey reads: “And how democratically is this country being governed today?” The answers are on a scale from 1 (“not at all democratic”) to 10 (“completely democratic”). We use the arithmetic mean of the answers. According to the Survey, Ukranians feel least governed democratically whereas people from Ghana feel most democratically governed.

3.3 A first take at the data: bivariate correlations

Bivariate correlations enable us to get a sense of the possible relationships between direct democratic institutions and the ten dependent variables that are described in 3.2. Again, we do not only have an eye on the correlations with the formal institutions, but also on their actual use over a dozen years. And again, the differences in the various correlation coefficients are noteworthy.

Out of 60 bivariate correlations between the political participation variables and those of direct democratic institutions, 15 are correlated at least on the 10 % level of significance. The first three columns reflect our de jure measures, the last three columns the frequency of their actual use. A couple of results stand out: (1) both the possibility of optional referendums and of initiatives is negatively correlated with our proxies for trust in politics. (2) Political activity (proxied for by “joining boycott” and “demonstration”) is negatively correlated with the formal requirement for mandatory referendums but positively with the number of optional referendums that took place between 1995 and 2006.

Both results appear robust in the sense that similar dependent variables display similar bivariate correlations with our direct democracy variables. This increases our confidence in the proxies (Table 4).

Bivariate correlations are interesting to get a sense of possible interdependencies. But they can also be misleading because effects are almost never monocausal. This is why we move on to multivariate regressions now.

3.4 Toward multivariate correlations: choosing the covariates

The estimation approach used is straightforward and follows directly from the theoretical part. We are interested in estimating the dependent variable Y that can stand for any of the political participation variables introduced in Sect. 3.2 above. The vector M is made up of the standard explanatory variables conventionally used to determine the respective dependent variable. Our general specification thus takes the form

where DIR is any of four direct democracy variables,Footnote 6 Z is a vector of controls and ε is the error term. The cross-section analysis is performed by OLS, inference is based on t-statistics computed on the basis of White heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors.

Now, to tease out as much information of the data as possible, we propose to take the various forms in which direct democracy institutions have been combined in a country explicitly into account. To do so, we estimate the following equation:

where DMANREF = 1 if mandatory referendum available; DINI = 1 if initiative available; and DBOTH = 1 if both referendum and initiative available.

Generally speaking, any kind of political participation—no matter whether voting at a general election or attending a demonstration etc.—can be expected to be a function of a number of basic determinants such as income, education, the number of years a country has been democratic without interruption, the degree of democracy actually realized and ethnolinguistic fractionalization. We therefore always begin our estimates with these variables, usually complemented by a number of geographic dummy variables.

The first dependent variable we are interested in is voter turnout. Geys (2006) provides a meta-analysis of 83 aggregate-level studies that have analyzed the determinants of voter turnout and that comprise both national and sub-national elections as well as turnout for representative and direct democratic elections. In setting up our vector of standard explanatory variables, we largely follow Geys who distinguishes between institutional, socio-economic and political variables. Among the institutional variables, the electoral system has been found an important determinant for showing up at the election booth or not. Turnout is expected to be higher under proportional representation (PR) than under majority rule (MAJ) because there is a close correlation between the number of votes and the number of seats under PR (but not under MAJ), which could make potential voters believe in the importance of their vote. Further, districts are more likely to be competitive under PR than under MAJ. Powell (1980) argues that bonds between parties and groups are stronger under PR, inducing higher turnout. The most important counter-argument seems to be that PR electoral systems frequently lead to coalition governments. Then, it is really party politicians who determine the government and not the voters which would reduce the incentive of turning up on election day.Footnote 7

Quite a few electoral systems know compulsory voting. It is straightforward to assume that it will increase voter turnout which is, according to Geys’ meta-analysis, indeed the case according to the overwhelming number of studies. We control for it by a simple dummy variable.Footnote 8

Socio-economic variables are the next group of variables that Geys (2006) analyzes. Population size is expected to be a determinant of voter turnout because the larger the population, the smaller the chance that any citizen will cast the decisive vote and hence the lower the incentives to go voting if one assumes voters to be instrumentally motivated. We use the logarithm of population size to take account of the huge variation in population size between countries. Next, population stability is found to be a significant determinant of voter turnout. Population stability is high if identical persons interact over long periods of time. It has been measured by population mobility, population growth and homeownership. Here, we use the share of the urban population as a proxy for population instability on the assumption that urban citizens are more mobile and less likely to be part of established and long-lasting networks.

Finally, two political variables have been identified by Geys (2006) as being significant for explaining voter turnout, namely the closeness of the election and campaign expenditures. In a cross-country setting, it is not necessarily meaningful to compare campaign-expenditures which is why we do not include this variable. Closeness of the election can be reflected by a variable FRAC (for fractionalization) which is 100 minus the percentage of the votes secured by the largest party. The higher the value of the variable, the closer is electoral competition assumed to be.

Regarding our second group of dependent variables—namely interest in politics—, we can be a lot shorter. We are not aware of any “canonical” M-vector used to explain the degree of political interest and civic engagement found in various societies. Beyond our “all purpose vector” shortly described above, it seems, however, plausible to rely on the following variables: ideological preferences (“partisanship”); at least two, partially contradictory, conjectures come to mind: First, left-leaning people could generally be more ready to actively participate by signing petitions or joining boycotts. Second, citizens at either end of the political spectrum could be more likely to become politically active (e.g. because their own preferences are not sufficiently represented in parliament etc.). Further, it seems that less populated rural areas are less attractive for political action. We hence include the number of inhabitants per hectare (population density) taken from the Banks-database (Banks 2004).

Finally, regarding our third group of dependent variables—institutional trust—we rely on exactly the same explanatory variables as with regard to political interest and civic engagement.

3.5 Causality?

To be clear from the outset: Establishing causality based on a single cross-section is impossible. Properly speaking, we can only identify correlations. This is why we have been reluctant to talk of “effects” of direct democracy throughout the paper. But in the absence of any quasi-natural experiments and given the data limitations, establishing robust correlations seems the best we can do. And it might be worth noting that the previous literature surveyed above relies on exactly the same kind of correlations, so these results are also useful because they can be easily compared with previous research. Two problems usually loom large in such kind of exercises, namely omitted variable bias and endogeneity. We propose to implement a number of cautionary measures to rule out some possible sources of spurious correlations.

Ex ante, we cannot exclude the possibility that both the respective dependent variable and the relevant proxy for direct democracy are driven by some third variable. It could, e.g., be the case that social capital or civic engagement broadly conceived play such a role. To control for that possibility, we include proxies for both social capital and for civic engagement. Social capital is some combination between general trust and reliable networks (see, e.g., Fukuyama 1995 or Blume 2009). The general level of trust among citizens has important consequences for the development of entire societies (Knack and Keefer 1997). If trust is high, transaction costs are low and the number of transactions should correspondingly be higher. To ensure that we do not fall prey to omitted variable bias, we thus include the general level of trust in our control vector. A similar argument applies to civic engagement.

It could further be that broad civic engagement does not only increase voter turnout (and some of the other left-hand-side variables) but also causes direct democratic institutions to be created in the first place and to be used frequently later on. To control for that possibility, we rely on a variable which depicts the number of international non-government organizations active in a country which was created by Paxton (2002). We normalize the absolute number with population size and end up with a variable number of INGOs per 1.000 inhabitants.

Simply including proxies for social capital and civic engagement into the regressions is insufficient to rule out omitted variable bias. Rather, we want to be sure that the means of these variables do not significantly differ between the “treatment” and the “control” groups. Table 5 documents the means for both social capital and civic engagement for countries with direct democracy (the treatment group) and those without (the control group).

The means of the control group do not differ significantly from the means of the treatment group.Footnote 9

As always when institutions serve as the independent variable, endogeneity is a potential problem. Here, it is particularly severe as we could deal with outright reversed causality: if the citizens put little trust in their politicians, they might be more inclined to introduce direct democratic institutions.

The standard way to control for endogeneity problems is to draw on instrumental variables. To determine whether endogeneity is a problem, we run the Hausman test drawing on the age of the constitution, the percentage of the population speaking English or a European language as a broad instrument for the quality of institutions generally conceived, the ethnic fractionalization of society, the urban population as a percentage of total population in 1950 as well as the share of the population that professed to be Catholic in 1980 and a dummy variable for Switzerland.Footnote 10 These variables work quite well as instruments for the de facto use of direct democratic institutions, for their de jure counterpart, they are somewhat weaker. In order not to overburden the paper with tables, we refrain from documenting 2SLS results as long as the Hausman test indicates no problems. We do, however, document the p value of that test. There is only one case in which the Hausman test indicates an endogeneity problem, namely regarding direct democracy and trust in parliament. In that case, we explicitly had a look at 2SLS-estimates: it turns out that the correlation remains insignificant.

4 Estimation results and their interpretation

We present our findings regarding the ten dependent variables in seven Tables.Footnote 11 To save space, we only document the estimation results of the direct democracy variables. All other variables included in the respective equation are mentioned in the notes below the tables. Switzerland is clearly the country with the most frequent use of direct democratic institutions on the federal level. To ensure that our results are not driven by Switzerland, we have also excluded her from all equations reported here. Our results are robust to the exclusion of Switzerland. We further tested the robustness of our results by adding partisanship, trust, the Gini-coefficient, population density, the percentage of the population following Confucianism, and former British as well as former Spanish colonies. At times, the number of observations significantly decreases but all our results are robust to the inclusion of these additional controls.

Table 6 depicts the correlation between direct democracy and voter turnout. Regarding de jure institutions, no significant association is found. Regarding de facto institutions, the number of initiatives is negatively correlated with turnout. If anything, calling citizens to the voting booth is associated with lower, rather than higher, voter turnout. This observation seems to be more severe regarding initiatives than referendums. It could mean that there might be “too much of a good thing.” If citizens often get the chance to vote, they might get tired of it.Footnote 12 Alternatively, this could also mean that citizens prefer to vote on issues they deem as important and not on issues they perceive as less important (namely general elections). But this is a bold hypothesis that we cannot test with the available data. The voter turnout variable reflects turnout at general elections. To see whether there is something to the conjecture, we would need to know whether there is substitution going on between general election turnout and initiative turnout. Given the current data availability, we are not able to test that possibility. The result is only significant at the 10 %-level and not robust to the inclusion of a control variable on subnational referendums and should, thus, not be over-interpreted.Footnote 13

Moving on to our second group of variables, namely deliberation encompassing interest in politics as well as the propensity to discuss political matters, we find that referendums and initiatives are never significantly associated with them, no matter whether measured de jure (as a simple dummy variable) or de facto (number of referendums/initiatives having taken place over a dozen years).Footnote 14 This is why we refrain from describing the relationship between direct democracy and the frequency of political discussion separately and focus instead on the relationship between direct democracy and interest in politics (Table 7).Footnote 15

Analyzing the effects of direct democracy on the propensity to participate in political action, we find some evidence that direct democracy in the form of referendums is significantly correlated with fewer boycotts as a strong form of political protest (Table 8) but not weaker forms of protest such as demonstrations (Table 9). If this relationship was causal—which we do not know—it would indicate that political conflicts in societies having direct democracy instruments at their disposal are carried out in a less radical fashion than in those not having such instruments at their disposal. Again, the result is only significant at the 10 %-level and should, thus, not be over-interpreted.

The results with regard to the last group of dependent variables, namely trust in political organizations, display yet another structure: we find a strong and robust negative correlation between direct democracy institutions in the constitution and the trust in both governments and parties. Trust in parliaments and the democratic system as such remain, however, unaffected (Table 10).Footnote 16

How to make sense of that result? Three possibilities come to mind: First, it could be that the possibility of direct democracy was introduced as a consequence of citizens displaying low trust and confidence in their political institutions. We might, hence, deal with a case of reversed causality. Second, it could be that direct democracy makes citizens more critical concerning the outcomes achieved by governments and political parties. In other words, political action is regarded more critically. This possibility fits well with the observation that trust in democracy is unaffected by direct democratic elements. Third, it is noteworthy that the number of referendums and initiatives actually held is never significantly correlated with trust in government and parties. It could, hence, be that it is the difficulty of successfully using these instruments that drives this result. It would be interesting to take the costs (in terms of votes necessary for an initiative to take place e.g.) explicitly into account. On the basis of the available data we are, however, not able to do that. Since the Hausman test does not suggest that endogeneity is a problem we can rule out the first option. It thus seems that the availability of direct democratic institutions induces citizens to be more critical concerning party politics—and to be less trustful in government (Table 11).

Summing up our empirical results, two results stand out: Firstly, we do not find a significant positive impact of direct democracy institutions on deliberation in the form of higher voter turnout, increased interest in politics or an increased propensity to discuss politics. Secondly, direct democracy is negatively correlated with trust in parties and governments. Our findings challenge at least some of the results previously reported in the literature. How to make sense of this? First of all, it seems worth noting that none of the studies surveyed above remained uncontested. Almost every result finding that direct democracy institutions were significantly correlated with various aspects of the political process has been challenged by at least one other study not finding a significant correlation. Secondly, the overwhelming majority of studies analysing the relationship between direct democracy institutions and the political process deal exclusively with the US and more precisely with variation across US states. It appears plausible that results based on regional or even communal institutions are not identical with those reached on the nation-state level.

5 Conclusions and outlook

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper that assesses the consequences of direct democratic institutions on various aspects of political participation in a broad cross country setting. There are three main results. First, voter turnout is not significantly affected by direct democratic institutions. Second, interest in politics and participation in political action is not positively affected by direct democratic institutions either. Direct democracy institutions possibly serve as a substitute for some kinds of political participation such as boycotts. Third, institutional trust in parties and governments is negatively correlated with direct democracy. It seems that direct democratic institutions are no panacea to produce citizens that are genuinely interested in the res publica and therefore know more about it and participate more in the decision-making process. If one strives to realize such an ideal, the results reported in this study should serve as a cautionary warning.

But the results reported here should not be overinterpreted either. The number of observations is frequently not very high and we cannot claim to have established causality. This is definitely a desideratum that future studies should aim at. In addition, it would seem desirable to include other variables that might be associated with direct democratic institutions. Desirable variables include the actual degree of information that citizens really have, but also the time they really spent on discussing politics and political activities. The World Values Survey has the obvious disadvantage of relying on the self-assessment of the surveyed. It is also desirable to rerun the current study on the basis of more exclusionary variables of direct democracy.

Notes

It should really be the rationally ignorant citizen—as the theory also predicts that he will not vote.

Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (2001) analyze process preferences of US American voters empirically. They find that those who support more direct involvement of citizens in decision making are simultaneously also more likely to support delegation of decision-making competence to non-elected technocrats (such as central bankers).

Note the structural similarity to the argument that a constitution for knaves—as recommended by David Hume—crowds out mutual trust between citizens and politicians (Frey 1997).

There, we find that only 20.5 % have optional referendums. This huge difference is primarily due to plebiscites that are not distinguished from referendums here. In our earlier survey, we counted 64.8 % of all countries as allowing for plebiscites, a percentage fairly close to the 68.1 % reported here.

Here is some information on the outliers in Table 3: Israel (37.1) is an outlier regarding “discuss political matters frequently”, Sweden (31.0) one regarding “joining boycotts” and Bangladesh is an outlier with regard to all “great deal” questions (all answered with their possible maximum). Data from Bangladesh might, hence, be problematic and we include a country dummy for that country.

More specifically, we test both de jure and de facto mandatory referendums as well as the de jure and de facto initiatives. To save space, we refrain from reporting the results on optional referendums as they do not convey additional insights.

In addition to the electoral system, we propose to control for the form of government, the question i.e. whether a country has a presidential or parliamentary system. This could have an influence on voter turnout regarding legislatures because under parliamentary systems, it is the legislature that determines the head of the executive. Also, presidential systems often have a form of direct citizen participation if the president is elected directly by the citizens.

A reviewer suggested that we exclude countries with compulsory voting entirely—and not control for them with a dummy as we do. Exclusion of those countries leaves the results unaffected.

With regard to MANDREF and INI, the mean for trust is even higher in the control group.

The choice of these variables as instruments is motivated in a little more detail in Blume et al. (2009).

To save space, we report results on voter turnout only on the basis of the percentage of registered voters (and drop those based on voting population).

We did run regressions with a quadratic term. The term never reached conventional significance levels though.

Results of an alternative regression that draws on voter turnout as percent of the voting population are different in the sense that none of the variables proxying for direct democratic institutions is significant.

This result remains unchanged when the dependent variable only includes the item “very interested” and not the aggregate of both “very” and “somewhat interested.” In this case, the R2 of the entire regression raises to more than 50 %.

The significant impact of MANDREF on political interest in column 5 is not robust to the inclusion of the de facto variables.

In an exemplary fashion, Table 12 shows the relationship between direct democracy and trust in parliaments. The correlation between direct democracy and the variable “how is democracy” is also insignificant.

References

Alesina, A., Devleeschauer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S., & Wacziarg, R. (2002). Fractionalization, NBER working paper 9411.

Banks, Arthur S. (2004). Banks’ Cross-National Time-Series Data Archive. Binghamton, NY: Databanks International [distributor].

Beck, Th., Clarke, G., Groff, A., Keefer, Ph., Walsh, P. (2000). New Tools and New Tests in Comparative Political Economy: The Database of Political Institutions. Washington: The World Bank.

Benz, M., & Stutzer, A. (2004). Are voters better informed when they have a larger say in politics?—Evidence for the European Union and Switzerland. Public Choice, 119, 31–59.

Blume, L. (2009). Regionale Institutionen und Wachstum: Sozialkapital, Kommunalverfassungen und interkommunale Kooperation aus regional- und institutionenökonomischer Sicht. Marburg: Metropolis.

Blume, L., Müller, J., & Voigt, S. (2009). The economic effects of direct democracy—A first global assessment. Public Choice, 140, 431–461.

Butler, D., & Ranney, A. (1994). Theory. In D. Butler & A. Ranney (Eds.), Referendums around the world—The growing use of direct democracy, chapter 2. Washington, DC: AEI Press.

CIA (2005). The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/cia/download2005.htm.

Citrin, J. (1996). Who’s the boss? Direct democracy and popular control of government. In Stephen Craig (Ed.), Broken contract? Changing relationships between Americans and their government (pp. 268–293). Boulder: Westview Press.

Cox, G., & Munger, M. (1989). Closeness, expenditures and turnout in the 1982 US house elections. American Political Science Review, 83(1), 217–231.

Deininger, K., & Squire, L. (1996). A new data set measuring income inequality. World Bank Economic Review, 10(3), 565–591.

Donovan, T., Tolbert, C., & Smith, D. (2009). Political engagement, mobilization, and direct democracy. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(1), 98–118.

Dyck, J. (2009). Initiated distrust. Direct democracy and trust in government. American Politics Research. doi:10.1177/1532673X08330635.

Dyck, J., & Seabrock, N. (2010). Mobilized by direct democracy: Short-term versus long-term effects and the geography of turnout in ballot measure elections. Social Science Quarterly, 91(1), 188–208.

Freedom House (2005). Freedom in the World Country Ratings 1973–2005. http://65.110.85.181/uploads/FIWrank7305.xls.

Frey, B. (1997). A constitution for knaves crowds out civic virtues. The Economic Journal, 107, 1043–1053.

Frey, B., Benz, M., & Stutzer, A. (2004). Introducing procedural utility: Not Only what, but also how matters. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 160, 377–401.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York: Free Press.

Gerber, E., Lupia, A., McCubbins, M., & Kiewit, R. (2001). Stealing the initiative—How state government responds to direct democracy. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice Hall.

Geys, Benny. (2006). Explaining voter turnout: A review of aggregate-level research. Electoral Studies, 25, 637–663.

Golder, M. (2005). Democratic electoral Systems Around the World, 1946–2000. Electoral Studies, 24, 103–121.

Hibbing, John, & Theiss-Morse, E. (2001). Process preferences and American politics: What the people want government to be. American Political Science Review, 95, 145–153.

Hug, Simon. (2005). The political effects of referendums: An analysis of institutional innovations in Eastern and Central Europe. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 38, 475–499.

IDEA (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance). (2008). Direct democracy: The international IDEA handbook. Stockholm: IDEA.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 1251–1288.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., Vishny, R. (1999). The Quality of Government. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 15(1), 222–279.

Matsusaka, J. (1995). Explaining voter turnout patterns: An information theory. Public Choice, 84, 91–117.

Matsusaka, J. (2005). The eclipse of legislatures: Direct democracy in the 21st century. Public Choice, 124, 157–177.

Matsusaka, J. (2008). Direct democracy and the executive branch. In S. Bowler & A. Glazer (Eds.), Direct democracy’s impact on american political institutions (pp. 115–136). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Matsusaka, J. (2010). Popular control of public policy: A quantitative approach. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 5, 133–167.

Mueller, D. (2003). Public Choice III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Olson, M. (1965). The Logic of Collective Action. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Paxton, P. (2002). Social capital and democracy: An interdependent relationship. American Sociological Review, 67(2), 254–277.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The Economic Effects of Constitutions. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Powell, B. (1980). Voting turnout in 30 democracies: Partisan, legal and socio-economic influences. In R. Rose (Ed.), Electoral participation: A comparative analysis (pp. 5–34). London: Sage.

Schlozman, D., & Yohai, I. (2008). How initiatives Don’t always make citizens: Ballot initiatives in the American states, 1978–2004. Political Behavior, 30, 469–489.

Smith, M. (2001). The contingent effects of ballot initiatives and candidate races on turnout. American Journal of Political Science, 45(3), 700–706.

Smith, D., & Tolbert, C. (2004). Educated by initiative. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Tolbert, C. J., McNeal, R. S., & Smith, D. A. (2003). Enhancing civic engagement: The effect of direct democracy on political participation and knowledge. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 3, 23–41.

Tolbert, C., & Smith, D. (2005). The educative effects of ballot initiatives on voter turnout. American Politics Research, 33(2), 283–309.

Vanhanen, T. (2000). A New Dataset for Measuring Democracy, 1810–1998. Journal of Peace Research, 37, 252–265.

World Values Study Group (2008). World Values Survey 1981-1984, 1990-1993, 1995-1997, 1999-2001, and 2005-2008. Ann Arbor: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marc Berendsen and Andreas Block for extremely valuable research assistance and the participants of the panel “Effects of Direct Democracy on Representation and Policy-Making” at the ECPR General Conference in Potsdam (2009) as well as Matthias Dauner and Sang Min Park for questions and suggestions. Two referees of this journal made very constructive and helpful suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Voigt, S., Blume, L. Does direct democracy make for better citizens? A cautionary warning based on cross-country evidence. Const Polit Econ 26, 391–420 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-015-9194-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-015-9194-2