Abstract

Transitional age youth experiencing homelessness (TAY-EH) represent an underserved and understudied population. While an increasing number of empirical interventions have sought to address the high burden of psychopathology in this population, findings remain mixed regarding intervention effectiveness. In this systematic review of behavioral health interventions for TAY-EH, we sought to examine the structural framework in which these interventions take place and how these structures include or exclude certain populations of youth. We also examined implementation practices to identify how interventions involving youth and community stakeholders effectively engage these populations. Based on PRISMA guidelines, searches of Medline, PsycInfo, Embase, Cochrane Central, Web of Science, and ClinicalTrials.gov databases were conducted, including English language literature published before October 2022. Eligible studies reported on interventions for adolescent or young adult populations ages 13–25 years experiencing homelessness. The initial search yielded 3850 citations; 353 underwent full text review and 48 met inclusion criteria, of which there were 33 unique studies. Studies revealed a need for greater geographic distribution of empirically based interventions, as well as interventions targeting TAY-EH in rural settings. Studies varied greatly regarding their operationalizations of homelessness and their method of intervention implementation, but generally indicated a need for increased direct-street outreach in participant recruitment and improved incorporation of youth feedback into intervention design. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to examine the representation of various groups of TAY-EH in the literature on substance use and mental health interventions. Further intervention research engaging youth from various geographic locations and youth experiencing different forms of homelessness is needed to better address the behavioral health needs of a variety of TAY-EH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Transitional-age youth (youth between the ages of 16 and 25 years old) experiencing homelessness (TAY-EH) represent an understudied and underserved population in the United States. Remarkably, recent data shows that 4% of youth ages 13–17 years and 10% of youth ages 18–25 years report past-year experiences of homelessness (Morton et al., 2018a, 2018b). Furthermore, the sequelae of homelessness for these young people are widespread. In comparison to their stably housed peers, TAY-EH experience markedly higher rates of psychiatric illness, substance use disorder (SUD) (Burke et al., 2022, 2023), and medical and psychosocial morbidity (Chan et al., 2020; Rubin et al., 1996; Saperstein et al., 2014; Slesnick et al., 2018; Yates et al., 1988), and the relationships between these disorders and homelessness are complex and bi-directional (Nilsson et al., 2023). Thus, improving our understanding of how to support these youth is a critical societal need.

Structural Elements Affecting Intervention Efficacy and Equity

A growing body of literature has focused on targeted interventions for TAY-EH aimed at improving psychiatric and substance use outcomes. However, TAY-EH are a demographically, geographically, and experientially heterogeneous population (Toro et al., 2011), and the broader intervention literature lacks a comprehensive review of the current research landscape that might identify subgroups of youth not currently represented in the literature and illuminate opportunities for further research (García et al., 2020; Graham et al., 2008). Specifically, little research exists describing the structural elements of existing research studies external to particular intervention methodology that determine which TAY-EH have had access to interventions and the applicability of said interventions to the lived experience of TAY-EH. Structural study elements, encompassing those characteristics external to intervention methodology but defining and constraining the environment in which the intervention takes place, might include geographic location of study sites, sampling and recruitment techniques, definitions of homelessness, and the involvement of participants in intervention design. When examined in relation to one another, these structural elements can be used to identify assets and gaps in the extant literature on interventions for TAY-EH and thus inform equitable allocation of research-based resources.

One such example of a structural study element that influences which TAY-EH are represented in intervention studies is geographic location. For example, different states vary in their allowance of unaccompanied minors experiencing homelessness to apply for housing or shelter services (State Laws to Support Youth Experiencing Homelessness, 2023). In states that disallow unaccompanied minors to apply for services without parental notification or consent, a significant barrier to care exists for those youth for whom contacting a parent or guardian is unsafe (Ha et al., 2015). Consequently, an intervention taking place in a shelter with such rules in place is more likely to inadvertently exclude minors unable to contact a parent or guardian and thus to potentially bias intervention results. To address this type of disparity in access, informed expansion of inclusion criteria and recruitment practices can allow for the inclusion of a wider variety of youth in behavioral health interventions, promoting more equitable research practices and improving the generalizability of study results (Ruzycki & Ahmed, 2022).

As another example, structural study elements related to research design may have a significant impact on intervention efficacy and equity. Traditional academic research practices rely on a hierarchy in which the research scientist takes the role of objective investigator, while the population of interest serves as the research participant (Tobias et al., 2013). Interventions designed under this model restrict the process of study conceptualization to the investigator. In contrast, community-based participatory research, a research method gaining prominence in public health fields, includes community members as collaborators in the design of a study (Collins et al., 2018). Recent health research reviews suggest that this collaborative research model allows for more effective, culturally relevant, and sensitive implementation in comparison to traditional research frameworks (Bogart & Uyeda, 2009; Collins et al., 2018; O’Mara-Eves et al., 2015). A review by Curry et al. (2021) synthesizing findings on implementation and client engagement for interventions for youth experiencing homelessness highlighted the need for an examination of implementation efforts in quantitative studies of interventions for these youth (Curry et al., 2021). Qualitative results from the review indicated that intervention design practices such as youth and staff engagement and organization of physical space are directly tied to intervention effectiveness. As such, improving intervention design and development practices to better incorporate youth, staff, or other stakeholder perspectives not only results in more culturally relevant interventions, but may also increase participant retention and intervention effectiveness.

Recognition and analysis of these structural factors affecting research design and outcomes requires a higher-level view that is distinct from the hypothesis-driven model of testing a single research intervention. By determining which structural study elements are shared or distinct among different research interventions, we may be able to identify populations of youth who have previously been excluded from access and to help guide design of effective future interventions for TAY-EH.

Intervention Mental Health and Substance Use Outcomes

To date, research on TAY-EH has been comprised of specific interventions focused on improving psychiatric and substance use outcomes (Arnett, 2014; Gharabaghi & Stuart, 2010; Wilens & Rosenbaum, 2013). Interestingly, these studies have indicated mixed results on the efficacy of such interventions (Altena et al., 2010; Morton et al., 2020; Noh, 2018b; Wang et al., 2019; Watters & O’Callaghan, 2016). For example, a recent review examining interventions for youth experiencing homelessness in high-income countries found that while cognitive behavioral and family therapies led to improvements in mental health and substance use outcomes, other interventions showed inconsistent effects on outcome measures when compared to service as usual (Wang et al., 2019). Because many of these interventions take place in established community agencies, service as usual may consist of other non-specific support services that improve outcomes at rates similar to those in a particular intervention (Wang et al., 2019). Indeed, in a number of intervention studies for TAY-EH, mental health and substance use outcomes improve for both intervention and service as usual groups across the study duration but exhibit no significant differences between groups (Beattie et al., 2019; Linnemayr et al., 2021; Lynch et al., 2017; McCay et al., 2011; Medalia et al., 2017; Pedersen et al., 2022; Rew et al., 2022; Thompson et al., 2017; Tucker et al., 2021). Perhaps also, in these instances structural elements such as state or shelter policies not specifically addressed in individual interventions impact outcomes for all youths receiving services, potentially overriding the differential effects of a single intervention in comparison to service as usual.

Another limiting factor in TAY-EH research has been the methodological quality of existing empirical studies. Prior reviews examining intervention outcomes among TAY-EH have reported high risk of bias for many of the reviewed studies. This bias results largely from nonrandomization and poor retention rates, which is wholly unsurprising given the study population (Altena et al., 2010; Morton et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). For instance, given the transitory nature of youth experiencing homelessness, studies involving these youth often exhibit poor retention rates (Ferguson et al., 2010; Forchuk et al., 2018; Sanders et al., 2008). Furthermore, establishing the clinical equipoise required for ethical randomization of study participants has proven difficult in similar public policy interventions (MacKay, 2018; MacKay & Cohn, 2023). Improving upon these methodological limitations to decrease bias is desirable but not readily feasible. Thus, the reality of intervention implementation in settings that serve TAY-EH often prevents the methodological rigor that would allow for a lower risk of bias. As such, identifying additional tools for interrogating empirical findings at a more global scale could be of great value to the research and clinical communities that serve TAY-EH.

The Present Study

Given the substantial population of TAY-EH and these youths’ apparent psychosocial and medical needs, the creation of accessible, inclusive care that decreases risk for maladaptive outcomes remains critical. We propose that one effective means for doing so is through comprehensive examination of the landscape in which research interventions are conducted. Through the identification of the structural elements that shape research methods, eligible participants, and outcomes, we may be able to identify variables external to intervention implementation that affect study participation and outcomes. This approach is also valuable in its circumvention of challenges posed by the risk of bias present in existing interventions.

Our current review aims to characterize critical structural elements of study setting and design among intervention studies for mental health and/or SUD among TAY-EH. To our knowledge, no study has examined how patterns in the structural study elements of behavioral health interventions for TAY-EH might present an equitable or inequitable distribution of care for these youth. Our goal was to examine these elements through qualitative landscape analysis to create a comprehensive picture of youth experiencing homelessness who are and are not accounted for in the current literature. For youth currently accounted for in the literature, we also intended to identify how their perspectives and the perspectives of other community stakeholders are being incorporated into study designs in a reflection of equitable research practices.

Methods

A methodological protocol was registered with the PROSPERO systematic review protocol registry (ID: CRD42022354485). This systematic review was conducted and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021).

Search Strategy

Without language restrictions, we systematically searched the following databases from inception until October 11, 2022: Medline, PsycInfo, Embase, Cochrane Central, Web of Science, and ClinicalTrials.gov. Combinations of relevant keywords and MeSH terms can be found in the supplemental materials. Bibliographies of reviewed articles were examined for additional studies to ensure that no relevant articles were omitted.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies reported on adolescent or young adult populations ages 13–25 years experiencing homelessness. Though the focus of this review was specifically on transitional-age youth, a broader age range was included in the review to account for the developmental shift from adolescence to young adulthood. Study samples of similar age ranges (e.g., ages 12–18 or ages 18–26) were also included to better capture the variety of interventions available to transitional-age youth. Homelessness was operationalized as the lack of a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, based on definitions provided by the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (United States Code, 2020). Youth classified as runaways or street-youth were also included if they were without a fixed nighttime residence at the time of initial study involvement. Eligible interventions targeted behavioral health outcomes and included a comparator of some kind. Only English-language, peer-reviewed publications were included in the current review. No restrictions were implemented regarding study publication date.

Study Selection

Citation information was downloaded into Covidence online software (Covidence systematic review software), and duplicates were removed. The titles and abstracts of all papers were screened by two independent reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. Two independent reviewers then reviewed the full text of all relevant articles, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Articles for which full texts could not be obtained were excluded (N = 4) (Forchuk et al., 2014; Kalahasthi et al., 2022; Stewart et al., 2007; Yates et al., 1990). Records of all duplicate and excluded articles were maintained.

Data Collection

Two reviewers extracted data from the full-text studies, and all extracted data was reviewed by an independent reviewer. Extracted variables included study design, study duration, participant characteristics (i.e., demographic information, housing status, etc.), study setting, retention, and community-based participatory research practices (i.e., the engagement of stakeholders in the original study development).

Risk of Bias Assessment

To assess potential sources of bias, two investigators reviewed full texts of included papers applying the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias for randomized clinical trials (Higgins et al., 2011) and the ROBINS-I for assessing the risk of bias in nonrandomized trials (Sterne et al., 2016). The Cochrane Collaboration tool examines six domains of bias including sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other issues. The ROBINS-I examines seven domains of bias including confounding bias, selection bias, classification of intervention, deviations from intervention, missing data, measurement of outcomes, and reported results.

Results

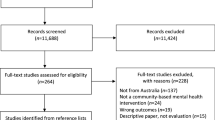

The search strategy yielded 6369 potentially relevant citations. After removing duplicates, investigators screened 3850 citations and assessed 353 full text articles. Forty-eight citations met full inclusion criteria, of which there were 33 unique studies (Fig. 1).

Methodological Quality of Included Studies

Overall, we determined that most RCTs (N = 37) were at low risk of bias for random sequence generation, blinding of participants and persons, blinding of outcome assessment, and incomplete outcome data. Most RCTs were at unclear or high risk of bias for selective reporting and allocation concealment (Fig. 2). Non-RCTs (N = 11) exhibited more variation in risk of bias assessments, with all non-RCTs having overall moderate risk of bias (Fig. 2).

Study Characteristics

Table 1 shows the main setting and sample characteristics of the 33 reviewed studies. Most studies took place in North America (n = 30). Of studies conducted in the United States (n = 24), 11 studies took place in the western part of the country (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; Booth et al., 1999; D’Amico et al., 2017; Ferguson, 2013, 2018; Ferguson & Xie, 2008; Linnemayr et al., 2021; Nyamathi et al., 2012, 2013; Pedersen et al., 2022; Peterson et al., 2006; Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005, 2009; Slesnick et al., 2007; Tucker et al., 2017, 2021), 6 in the Midwest (Chavez et al., 2020; Guo & Slesnick, 2017; Guo et al., 2014; Mallory et al., 2022; Slesnick et al., 2013b, 2015, 2016, 2020; Wu et al., 2020, 2022a, 2022b; Zhang & Slesnick, 2018; Zhang et al., 2021), 4 in the Northeast (Medalia et al., 2017; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2003; Thompson et al., 2017, 2020), 2 in the South (Rew et al., 2017; Santa Maria et al., 2021), and 1 in both the South and the Midwest (Rew et al., 2022). An additional study was conducted in both the northeastern area of the United States and in Calgary, Canada (Beattie et al., 2019; Lynch et al., 2017). Additional studies conducted in Canada (n = 4) took place in a variety of provinces, including Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal, and Moncton (Doré-Gauthier et al., 2020; Kozloff et al., 2016; McCay et al., 2011, 2015).

Most studies recruited youth from drop-in shelters (n = 12) (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; Booth et al., 1999; Chavez et al., 2020; D'Amico et al., 2017; Ferguson, 2013, 2018; Ferguson & Xie, 2008; Linnemayr et al., 2021; Nyamathi et al., 2012, 2013; Pedersen et al., 2022; Rew et al., 2022; Slesnick et al., 2007, 2015, 2020; Tucker et al., 2017, 2021; Wu et al., 2020, 2022a, 2022b; Zhang & Slesnick, 2018; Zhang et al., 2021), with an additional 3 studies recruiting from both drop-in centers and other agencies (Mallory et al., 2022; Rew et al., 2017; Santa Maria et al., 2021). The remaining studies recruited participants various types of shelters (crisis shelter, runaway shelter, etc.) (n = 9) (Guo et al., 2014; Hyun et al., 2005; Krabbenborg et al., 2017; Noh, 2018a; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2003; Shein-Szydlo et al., 2016; Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005, 2009; Slesnick et al., 2013a, 2013b; Slesnick et al., 2013a, 2013b; Thompson et al., 2017, 2020), the street (n = 1) (Guo & Slesnick, 2017; Slesnick et al., 2016), service clinics (n = 1) (Doré-Gauthier et al., 2020), and a transitional living center (n = 1) (Medalia et al., 2017). Six studies recruited participants from community agencies providing a variety of services to youth experiencing homelessness (Beattie et al., 2019; Kozloff et al., 2016; Lynch et al., 2017; McCay et al., 2011, 2015; Peterson et al., 2006), with 2 of these studies also including youth recruited directly from the street (Kozloff et al., 2016; Peterson et al., 2006).

Sample sizes of the reviewed studies ranged from 22 (McCay et al., 2011) to 602 (Rew et al., 2022) participants. The majority of studies focused exclusively on transitional-age youth, or youth between the ages of 16 and 25 (n = 17) (Beattie et al., 2019; Chavez et al., 2020; D’Amico et al., 2017; Ferguson, 2013, 2018; Ferguson & Xie, 2008; Kozloff et al., 2016; Linnemayr et al., 2021; Lynch et al., 2017; Mallory et al., 2022; McCay et al., 2011, 2015; Medalia et al., 2017; Pedersen et al., 2022; Rew et al., 2017, 2022; Santa Maria et al., 2021; Slesnick et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2017, 2020; Tucker et al., 2017, 2021; Wu et al., 2020, 2022a, 2022b; Zhang et al., 2021). Fourteen studies included transitional-age youth and younger adolescents, with the lowest included age being 11 years old (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; Booth et al., 1999; Guo & Slesnick, 2017; Guo et al., 2014; Hyun et al., 2005; Noh, 2018a; Nyamathi et al., 2012, 2013; Peterson et al., 2006; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2003; Shein-Szydlo et al., 2016; Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005, 2009; Slesnick et al., 2007, 2013a, 2013b, 2015, 2016; Zhang & Slesnick, 2018). Two studies included transitional-age youth and older young adults, with the oldest included age being 30 years old (Doré-Gauthier et al., 2020; Krabbenborg et al., 2017). In 25 studies, the samples were comprised of mostly male-identifying participants (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; Beattie et al., 2019; Booth et al., 1999; Chavez et al., 2020; D'Amico et al., 2017; Doré-Gauthier et al., 2020; Ferguson, 2013, 2018; Ferguson & Xie, 2008; Guo & Slesnick, 2017; Hyun et al., 2005; Kozloff et al., 2016; Krabbenborg et al., 2017; Linnemayr et al., 2021; Lynch et al., 2017; McCay et al., 2011, 2015; Medalia et al., 2017; Nyamathi et al., 2012, 2013; Pedersen et al., 2022; Peterson et al., 2006; Rew et al., 2022; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2003; Santa Maria et al., 2021; Slesnick et al., 2007, 2015, 2016, 2020; Thompson et al., 2020; Tucker et al., 2017, 2021; Wu et al., 2020, 2022a, 2022b; Zhang & Slesnick, 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). Eleven study samples included majority White, non-Hispanic participants (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; Booth et al., 1999; D'Amico et al., 2017; Doré-Gauthier et al., 2020; Guo & Slesnick, 2017; Kozloff et al., 2016; Nyamathi et al., 2012, 2013; Peterson et al., 2006; Rew et al., 2017; Slesnick et al., 2007, 2016, 2020; Tucker et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020, 2022a, 2022b; Zhang et al., 2021), 12 studies included majority Black or African American participants (Chavez et al., 2020; Ferguson, 2013, 2018; Ferguson & Xie, 2008; Guo et al., 2014; Linnemayr et al., 2021; Mallory et al., 2022; Medalia et al., 2017; Pedersen et al., 2022; Rew et al., 2022; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2003; Santa Maria et al., 2021; Slesnick et al., 2015, 2013a, 2013b; Thompson et al., 2020; Tucker et al., 2021; Zhang & Slesnick, 2018), 3 studies included majority Hispanic participants (Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005, 2009; Thompson et al., 2017), and 7 studies did not report on the specific race and ethnicity distributions of their participants (Beattie et al., 2019; Hyun et al., 2005; Krabbenborg et al., 2017; Lynch et al., 2017; McCay et al., 2011, 2015; Noh, 2018a; Shein-Szydlo et al., 2016). Only 10 studies reported on participant sexuality, with all of these studies having a majority of heterosexual participants (Beattie et al., 2019; D’Amico et al., 2017; Linnemayr et al., 2021; Lynch et al., 2017; Mallory et al., 2022; McCay et al., 2015; Pedersen et al., 2022; Peterson et al., 2006; Rew et al., 2017, 2022; Santa Maria et al., 2021; Slesnick et al., 2015; Tucker et al., 2017, 2021; Zhang & Slesnick, 2018).

Studies ranged greatly regarding their operationalizations of homelessness. Though all reviewed studies intended to recruit youth experiencing homelessness, only 8 studies implemented screening criteria to specifically recruit youth experiencing literal homelessness (Chavez et al., 2020; Guo & Slesnick, 2017; Kozloff et al., 2016; Mallory et al., 2022; Nyamathi et al., 2012, 2013; Santa Maria et al., 2021; Slesnick et al., 2007, 2015, 2016; Zhang & Slesnick, 2018). An additional 8 studies used time-based methods to identify eligible youth (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; Beattie et al., 2019; Booth et al., 1999; Ferguson, 2013; Ferguson & Xie, 2008; Lynch et al., 2017; McCay et al., 2011, 2015; Medalia et al., 2017; Shein-Szydlo et al., 2016), with 6 studies requiring youth to have spent the past month on the street, in a shelter, or unstably housed in order to be eligible (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; Beattie et al., 2019; Lynch et al., 2017; McCay et al., 2011, 2015; Medalia et al., 2017). Of the remaining studies, 6 reported on the percentage of participants living either on the street or in a shelter at baseline (Doré-Gauthier et al., 2020; Ferguson, 2018; Krabbenborg et al., 2017; Linnemayr et al., 2021; Pedersen et al., 2022; Rew et al., 2017; Thompson et al., 2020; Tucker et al., 2021), 4 reported only on the average amount of time spent either housed or homeless prior to baseline (D'Amico et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2014; Noh, 2018a; Slesnick et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2020; Tucker et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020, 2022a, 2022b; Zhang et al., 2021), and 7 did not provide any additional information regarding participant housing status at baseline (D'Amico et al., 2017; Hyun et al., 2005; Peterson et al., 2006; Rew et al., 2022; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2003; Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005, 2009; Thompson et al., 2017).

Regarding participant eligibility criteria, 19 studies only included participants reporting drug use or psychopathology at baseline (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; Doré-Gauthier et al., 2020; Ferguson, 2013, 2018; Ferguson & Xie, 2008; Guo & Slesnick, 2017; Guo et al., 2014; Kozloff et al., 2016; Linnemayr et al., 2021; Mallory et al., 2022; Medalia et al., 2017; Nyamathi et al., 2012, 2013; Pedersen et al., 2022; Peterson et al., 2006; Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005, 2009; Slesnick et al., 2007, 2013a, 2013b, 2015, 2016, 2020; Thompson et al., 2017, 2020; Tucker et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2020, 2022a, 2022b; Zhang & Slesnick, 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). Five studies required some form of parent/guardian involvement in order for youth to be eligible (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; Guo et al., 2014; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2003; Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005, 2009; Slesnick et al., 2013a, 2013b), with 3 of these studies requiring parent/guardian participation alongside youth participation (Guo et al., 2014; Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005, 2009; Slesnick et al., 2013a, 2013b). Only 1 study required eligible youth to have cell phone access (Linnemayr et al., 2021; Pedersen et al., 2022; Tucker et al., 2021).

Intervention Design and Implementation

Studies varied greatly in their method of intervention design and implementation (Table 2). Thirteen studies incorporated youth or agency staff feedback into their intervention design prior to intervention implementation (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; D’Amico et al., 2017; Ferguson, 2013, 2018; Ferguson & Xie, 2008; Krabbenborg et al., 2017; Linnemayr et al., 2021; Mallory et al., 2022; McCay et al., 2015; Noh, 2018a; Nyamathi et al., 2012, 2013; Pedersen et al., 2022; Peterson et al., 2006; Santa Maria et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2020; Tucker et al., 2017, 2021). Six of these studies incorporated youth or staff voices into the conceptualization of the design (Ferguson, 2013, 2018; Ferguson & Xie, 2008; Krabbenborg et al., 2017; Mallory et al., 2022; Noh, 2018a; Nyamathi et al., 2012, 2013), with 4 studies incorporating direct input from both youth and staff on the intervention design (Ferguson, 2013, 2018; Ferguson & Xie, 2008; Krabbenborg et al., 2017; Nyamathi et al., 2012, 2013) and 2 studies using youth interviews collected prior to the study conceptualization period (Mallory et al., 2022; Noh, 2018a). Seven of the 13 studies incorporated youth or staff feedback after the initial intervention design to better tailor the intervention to youth or staff preferences (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; D’Amico et al., 2017; Linnemayr et al., 2021; McCay et al., 2015; Pedersen et al., 2022; Peterson et al., 2006; Santa Maria et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2020; Tucker et al., 2017, 2021). Of these 7 studies, 4 incorporated only youth feedback (D'Amico et al., 2017; Linnemayr et al., 2021; Pedersen et al., 2022; Santa Maria et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2020; Tucker et al., 2017, 2021), 1 incorporated only staff feedback (McCay et al., 2015), and 2 incorporated both youth and staff feedback (Baer et al., 2007, 2008; Peterson et al., 2006).

Seven studies collected youth or agency staff feedback during or after intervention implementation, but not before (Beattie et al., 2019; Chavez et al., 2020; Doré-Gauthier et al., 2020; Guo & Slesnick, 2017; Kozloff et al., 2016; Lynch et al., 2017; Shein-Szydlo et al., 2016; Slesnick et al., 2016; Thompson et al., 2017). Some of these were pilot studies and as such incorporated measures of feasibility and acceptability into study outcomes. Thirteen additional studies made no mention of collecting youth or agency staff feedback at any point before, during, or after intervention implementation (Booth et al., 1999; Guo et al., 2014; Hyun et al., 2005; McCay et al., 2011; Medalia et al., 2017; Rew et al., 2017, 2022; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2003; Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005, 2009; Slesnick et al., 2007, 2013a, 2013b, 2015, 2020; Wu et al., 2020, 2022a, 2022b; Zhang & Slesnick, 2018; Zhang et al., 2021).

Discussion

The current qualitative systematic review utilized landscape analysis to examine the extant literature on the characteristics of quantitative intervention studies targeting mental health and substance use outcomes in TAY-EH. Similar to existing reviews, we found a substantial amount of empirically tested interventions for TAY-EH, with these studies varying greatly in terms of design, implementation, and duration. The current review expands upon the literature by focusing not only on intervention efficacy, but also by analyzing equity through an examination of the structural elements that shape study design, outcomes, and generalizability. Potentially impactful structural elements identified included geographic and demographic distribution, recruitment methods, and stakeholder participation in intervention design. By examining these elements, we also identified various groups of TAY-EH unaccounted for in the current literature as well as the prevalence of community-based research practices in intervention studies.

The results of this review suggest that most of the literature regarding mental health and substance use interventions for TAY-EH is generated in North America, although this finding was very likely impacted by the review’s English language restriction. Of the studies conducted in the United States, the subsections of the country with the most interventions included the West and Midwest. In comparison, the northeastern and southern parts of the country are relatively lacking in evidence for empirically evaluated interventions. Though the large number of studies conducted in the United States is indicative of researchers’ increased efforts to address the behavioral health needs of TAY-EH (Morton et al., 2020), this review highlights the need for increased geographic variability in intervention implementation. Weather varies significantly across the country, and homeless populations are at increased risk for mental or physical health changes as a result of extreme weather (Bezgrebelna et al., 2021). Moreover, individual states vary in sociodemographic makeup and may have specific policies surrounding youth homelessness that impact youth’s ability to receive care in different locations (Jones et al., 2021; A State-by-State Guide to Obtaining ID Cards, 2016). Transitional-age youth in particular are greatly affected by age-related restrictions for youth services such as foster care that vary between states. Also, states vary in their allowance for unaccompanied youth to obtain state-issued identification that may, for instance, impact a youth’s ability to obtain a job (Sanders et al., 2020; A State-by-State Guide to Obtaining ID Cards, 2016). Thus, as the rights and subsequent needs of youth and specifically TAY-EH vary among states, the mental health and substance use patterns of these youth are also likely to vary by state.

The majority of interventions in the current review were conducted in urban environments. Given that rural settings often lack community agencies for youth experiencing homelessness in comparison to urban areas, implementing interventions in drop-in clinics or shelters is most easily achieved in urban settings (Morton et al., 2018a, 2018b). Nonetheless, fewer community resources in rural settings does not necessarily correlate with lower populations of these youth, as recent research in the United States has found that rates of youth homelessness are similar across urban and rural settings (Morton et al., 2018a, 2018b). Youth experiencing homelessness in rural settings may also differ in their experience of homelessness in comparison to their counterparts in urban settings. Research suggests that youth experiencing homelessness in rural settings are more likely to be hidden in their communities (i.e., spend time couch surfing, sleeping in vehicles, etc.) and thus not be as easily identified as homeless (Farrin et al., 2005; Skott-Myhre et al., 2008). As such, intervention inclusion criteria requiring time-based measurements to identify homeless status such as time spent on the street or in a shelter, as seen in some of the reviewed studies, may unintentionally exclude youth from different settings.

The current review also identified groups of TAY-EH for whom more outreach appears necessary. Only three of the reviewed studies utilized direct street outreach to recruit youth. The majority of the studies, by having samples of youth recruited almost entirely from community agencies, limited the intervention to service-seeking youth. Reaching youth not already engaged in services is essential to determine the efficacy of these interventions, as youth in shelter settings exhibit different patterns of substance use in comparison to youth on the street (Curry et al., 2016). Also in need of targeted interventions are LGBTQIA + and gender-diverse youth. Although research suggests that these youth are at a disproportionate risk of homelessness and negative sequelae in comparison to their cisgender, heterosexual peers (Keuroghlian et al., 2014; Maccio & Ferguson, 2016), only 10 studies in the current review reported on participant sexuality, with all of these studies containing a majority heterosexual sample.

There was considerable variation in intervention design strategies in the current review. Although many of the studies incorporated youth or staff feedback into the intervention in some form, less than half of the studies explicitly described involving youth or community stakeholders in the design of the intervention. For marginalized youth such as TAY-EH who may be hesitant to engage in services, using community-based participatory research methods is particularly relevant in the creation of tailored, culturally sensitive interventions. Furthermore, as many of the studies in the current review took place in pre-existing community agencies, incorporating staff perspectives on youth needs may allow for the creation of more relevant and sustainable interventions as well as more equitable research partnerships.

Limitations

The findings of this review must be interpreted in relation to substantial limitations in the review design. As previously mentioned, the review’s inclusion of only English language articles likely resulted in the low numbers of articles from countries outside of the United States and Canada. The current discussion was thus only able to comment on the geographic distribution of interventions within these locations. A second limitation is the requirement of a comparator group for all included studies. Although this review did not assess intervention efficacy, we chose only to include interventions with some form of comparator group to establish a baseline for empirical rigor. Nonetheless, in doing so we likely excluded a number of qualitative studies that might have better incorporated youth or staff feedback into intervention implementation due to the nature of the study design. Furthermore, the high risk of bias present in many of the identified studies indicates the difficulty in establishing an adequate standard for empirical rigor. Finally, though the current review aimed to describe intervention implementation characteristics such as the incorporation of youth or staff voices, we were unable to compare these characteristics to intervention efficacy or retention given the variation in study designs. As such, we cannot comment on whether community-based participatory research practices improve either intervention efficacy or retention in samples of TAY-EH.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the current review identified several gaps and structural inequities in the current intervention literature. Fruitful follow-up interventions might address populations of TAY-EH currently less represented in the literature, such as LGBTQIA + youth or youth experiencing homelessness in rural settings. Because housing, shelter, and other policies for TAY-EH vary between states, future research might also compare how youth in different states respond to the same intervention given their varying needs. Finally, the current review identified the need for more widespread implementation of community-based participatory research frameworks into quantitative intervention studies.

Given the substantial and heterogeneous psychological and substance use needs of TAY-EH, tailored, effective interventions are greatly needed for these youth. By recognizing and addressing structural elements serving as barriers and facilitators to intervention participation, future research can create more effective and more equitable interventions.

References

Altena, A. M., Brilleslijper-Kater, S. N., & Wolf, J. L. (2010). Effective interventions for homeless youth: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38(6), 637–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.02.017

Arnett, J. J. (2014). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199929382.001.0001

Baer, J. S., Beadnell, B., Garrett, S. B., Hartzler, B., Wells, E. A., & Peterson, P. L. (2008). Adolescent change language within a brief motivational intervention and substance use outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(4), 570–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013022

Baer, J. S., Garrett, S. B., Beadnell, B., Wells, E. A., & Peterson, P. L. (2007). Brief motivational intervention with homeless adolescents: Evaluating effects on substance use and service utilization. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21(4), 582–586. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164x.21.4.582

Beattie, K., McCay, E., Aiello, A., Howes, C., Donald, F., Hughes, J., MacLaurin, B., & Organ, H. (2019). Who benefits most? A preliminary secondary analysis of stages of change among street-involved youth. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(2), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2018.11.011

Bezgrebelna, M., McKenzie, K., Wells, S., Ravindran, A., Kral, M., Christensen, J., Stergiopoulos, V., Gaetz, S., & Kidd, S. A. (2021). Climate change, weather, housing precarity, and homelessness: A systematic review of reviews. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115812

Bogart, L. M., & Uyeda, K. (2009). Community-based participatory research: Partnering with communities for effective and sustainable behavioral health interventions. Health Psychology, 28(4), 391–393. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016387

Booth, R. E., Zhang, Y., & Kwiatkowski, C. F. (1999). The challenge of changing drug and sex risk behaviors of runaway and homeless adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect, 23(12), 1295–1306. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00090-3

Burke, C. W., Firmin, E. S., Lanni, S., Ducharme, P., DiSalvo, M., & Wilens, T. E. (2023). Substance use disorders and psychiatric illness among transitional age youth experiencing homelessness. JAACAP Open. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaacop.2023.01.001

Burke, C. W., Firmin, E. S., & Wilens, T. E. (2022). Systematic review: Rates of psychopathology, substance misuse, and neuropsychological dysfunction among transitional age youth experiencing homelessness. The American Journal on Addictions, 31(6), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.13340

Chan, P. Y., Kaba, F., Lim, S., Katyal, M., & MacDonald, R. (2020). Identifying demographic and health profiles of young adults with frequent jail incarceration in New York City during 2011–2017. Annals of Epidemiology, 46, 41-48.e41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.04.006

Chavez, L. J., Kelleher, K., Slesnick, N., Holowacz, E., Luthy, E., Moore, L., & Ford, J. (2020). Virtual reality meditation among youth experiencing homelessness: Pilot randomized controlled trial of feasibility. JMIR Ment Health, 7(9), e18244. https://doi.org/10.2196/18244

Collins, S. E., Clifasefi, S. L., Stanton, J., Advisory, T. L., & B., Straits, K. J. E., Gil-Kashiwabara, E., Rodriguez Espinosa, P., Nicasio, A. V., Andrasik, M. P., Hawes, S. M., Miller, K. A., Nelson, L. A., Orfaly, V. E., Duran, B. M., & Wallerstein, N. (2018). Community-based participatory research (CBPR): Towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. American Psychologist, 73(7), 884–898. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000167

Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation. www.covidence.org

Curry, S. R., Baiocchi, A., Tully, B. A., Garst, N., Bielz, S., Kugley, S., & Morton, M. H. (2021). Improving program implementation and client engagement in interventions addressing youth homelessness: A meta-synthesis. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105691

Curry, S. R., Rhoades, H., & Rice, E. (2016). Correlates of homeless youths’ stability-seeking behaviors online and in person. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 7(1), 143–176. https://doi.org/10.1086/685107

D’Amico, E. J., Houck, J. M., Tucker, J. S., Ewing, B. A., & Pedersen, E. R. (2017). Group motivational interviewing for homeless young adults: Associations of change talk with substance use and sexual risk behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(6), 688–698. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000288

Doré-Gauthier, V., Miron, J. P., Jutras-Aswad, D., Ouellet-Plamondon, C., & Abdel-Baki, A. (2020). Specialized assertive community treatment intervention for homeless youth with first episode psychosis and substance use disorder: A 2-year follow-up study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 14(2), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12846

Farrin, J., Dollard, M., & Cheers, B. (2005). Homeless youth in the country: Exploring options for change. Youth Studies Australia, 24(3), 31–36.

Ferguson, K. M. (2013). Using the social enterprise intervention (SEI) and individual placement and support (IPS) models to improve employment and clinical outcomes of homeless youth with mental illness. Social Work in Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2013.764960

Ferguson, K. M. (2018). Nonvocational outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of two employment interventions for homeless youth. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(5), 603–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731517709076

Ferguson, K. M., Jun, J., Bender, K., Thompson, S., & Pollio, D. (2010). A comparison of addiction and transience among street youth: Los Angeles, California, Austin, Texas, and St. Louis, Missouri. Community Mental Health Journal, 46(3), 296–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9264-x

Ferguson, K. M., & Xie, B. (2008). Feasibility study of the social enterprise intervention with homeless youth. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507303535

Forchuk, C., O’Regan, T., Jeng, M., & Wright, A. (2018). Retaining a sample of homeless youth. Journal of Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(3), 167–174.

Forchuk, C., Richardson, J., Bryant, M., Csiernik, R., Edwards, B., Fisman, S., Godin, M., Mitchell, B., Norman, R., & Rudnick, A. (2014). Testing and comparing three service options for homeless youth with mental illness: Housing first, treatment first, or both together. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 17, S4–S5.

García, J. J., Grills, C., Villanueva, S., Lane, K. A., Takada-Rooks, C., & Hill, C. D. (2020). Analyzing the landscape: Community organizing and health equity. Journal of Participatory Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.13196

Gharabaghi, K., & Stuart, C. (2010). Voices from the periphery: Prospects and challenges for the homeless youth service sector. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(12), 1683–1689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.07.011

Graham, P., Evitts, T., & Thomas-MacLean, R. (2008). Environmental scans: How useful are they for primary care research? Canadian Family Physician, 54(7), 1022–1023.

Guo, X., & Slesnick, N. (2017). Reductions in hard drug use among homeless youth receiving a strength-based outreach intervention: Comparing the long-term effects of shelter linkage versus drop-in center linkage. Substance Use and Misuse, 52(7), 905–915. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2016.1267219

Guo, X., Slesnick, N., & Feng, X. (2014). Reductions in depressive symptoms among substance-abusing runaway adolescents and their primary caretakers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(1), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035380

Ha, Y., Narendorf, S. C., Santa Maria, D., & Bezette-Flores, N. (2015). Barriers and facilitators to shelter utilization among homeless young adults. Evaluation and Program Planning, 53, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2015.07.001

Higgins, J. P. T., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., Savović, J., Schulz, K. F., Weeks, L., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2011). The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343, d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

Hyun, M. S., Chung, H. I., & Lee, Y. J. (2005). The effect of cognitive-behavioral group therapy on the self-esteem, depression, and self-efficacy of runaway adolescents in a shelter in South Korea. Applied Nursing Research, 18(3), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2004.07.006

Jones, A., Sevilla, G., & Waguespack, F. D. (2021). State Index on Youth Homelessness. https://youthstateindex.com

Kalahasthi, R., Wadsworth, J., Crane, C. A., Toole, J., Berbary, C., & Easton, C. J. (2022). Establishing behavioral health services in homeless shelters and using telehealth digital tools: Best practices and guidelines. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 15(4), 208–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/ADD-07-2022-0019

Keuroghlian, A. S., Shtasel, D., & Bassuk, E. L. (2014). Out on the street: A public health and policy agenda for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth who are homeless. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0098852

Kozloff, N., Adair, C. E., Palma Lazgare, L. I., Poremski, D., Cheung, A. H., Sandu, R., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2016). “Housing first” for homeless youth with mental illness. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1514

Krabbenborg, M. A. M., Boersma, S. N., van der Veld, W. M., van Hulst, B., Vollebergh, W. A. M., & Wolf, J. R. L. M. (2017). A cluster randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of houvast: A strengths-based intervention for homeless young adults. Research on Social Work Practice, 27(6), 639–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731515622263

Linnemayr, S., Zutshi, R., Shadel, W., Pedersen, E., DeYoreo, M., & Tucker, J. (2021). Text messaging intervention for young smokers experiencing homelessness: Lessons learned from a randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(4), e23989. https://doi.org/10.2196/23989

Lynch, J., McCay, E., Aiello, A., & Donald, F. (2017). Engaging street-involved youth using an evidence-based intervention: A preliminary report of findings. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 30(2), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12179

Maccio, E. M., & Ferguson, K. M. (2016). Services to LGBTQ runaway and homeless youth: Gaps and recommendations. Children and Youth Services Review, 63, 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.02.008

MacKay, D. (2018). The ethics of public policy RCTs: The principle of policy equipoise. Bioethics, 32(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12403

MacKay, D., & Cohn, E. (2023). Public policy experiments without equipoise: When is randomization fair? Ethics & Human Research, 45(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/eahr.500153

Mallory, A. B., Luthy, E., Martin, J. K., & Slesnick, N. (2022). Variability in treatment outcomes from a housing intervention for young mothers misusing substances and experiencing homelessness by sexual identity. Children and Youth Services Review, 139, 106554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106554

McCay, E., Carter, C., Aiello, A., Quesnel, S., Langley, J., Hwang, S., Beanlands, H., Cooper, L., Howes, C., Johansson, B., MacLaurin, B., Hughes, J., & Karabanow, J. (2015). Dialectical behavior therapy as a catalyst for change in street-involved youth: A mixed methods study. Children and Youth Services Review, 58, 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.09.021

McCay, E., Quesnel, S., Langley, J., Beanlands, H., Cooper, L., Blidner, R., Aiello, A., Mudachi, N., Howes, C., & Bach, K. (2011). A relationship-based intervention to improve social connectedness in street-involved youth: A pilot study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 24(4), 208–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2011.00301.x

Medalia, A., Saperstein, A. M., Huang, Y., Lee, S., & Ronan, E. J. (2017). Cognitive skills training for homeless transition-age youth: Feasibility and pilot efficacy of a community based randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 205(11), 859–866. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0000000000000741

Morton, M. H., Dworsky, A., Matjasko, J. L., Curry, S. R., Schlueter, D., Chávez, R., & Farrell, A. F. (2018a). Prevalence and correlates of youth homelessness in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.10.006

Morton, M. H., Dworsky, A., Samuels, G. M., & Patel, S. (2018b). Missed opportunities: Youth homelessness in rural American. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Morton, M. H., Kugley, S., Epstein, R., & Farrell, A. (2020). Interventions for youth homelessness: A systematic review of effectiveness studies. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105096

Nilsson, S. F., Wimberley, T., Speyer, H., Hjorthøj, C., Fazel, S., Nordentoft, M., & Laursen, T. M. (2023). The bidirectional association between psychiatric disorders and sheltered homelessness. Psychological Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291723002428

Noh, D. (2018a). The effect of a resilience enhancement programme for female runaway youths: A quasi-experimental study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(9), 764–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1462871

Noh, D. (2018b). Psychological interventions for runaway and homeless youth. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 50(5), 465–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12402

Nyamathi, A., Branson, C., Kennedy, B., Salem, B., Khalilifard, F., Marfisee, M., Getzoff, D., & Leake, B. (2012). Impact of nursing intervention on decreasing substances among homeless youth. The American Journal on Addictions, 21(6), 558–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00288.x

Nyamathi, A., Kennedy, B., Branson, C., Salem, B., Khalilifard, F., Marfisee, M., Getzoff, D., & Leake, B. (2013). Impact of nursing intervention on improving HIV, hepatitis knowledge and mental health among homeless young adults. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(2), 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-012-9524-z

O’Mara-Eves, A., Brunton, G., Oliver, S., Kavanagh, J., Jamal, F., & Thomas, J. (2015). The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1352-y

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pedersen, E. R., Linnemayr, S., Shadel, W. G., Zutshi, R., DeYoreo, M., Cabreros, I., & Tucker, J. S. (2022). Substance use and mental health outcomes from a text messaging-based intervention for smoking cessation among young people experiencing homelessness. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 24(1), 130–134. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab160

Peterson, P. L., Baer, J. S., Wells, E. A., Ginzler, J. A., & Garrett, S. B. (2006). Short-term effects of a brief motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and drug risk among homeless adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20(3), 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164x.20.3.254

Rew, L., Powell, T., Brown, A., Becker, H., & Slesnick, N. (2017). An intervention to enhance psychological capital and health outcomes in homeless female youths. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 39(3), 356–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945916658861

Rew, L., Slesnick, N., Johnson, K., & Sales, A. (2022). Promoting healthy attitudes and behaviors in youth who experience homelessness: Results of a longitudinal intervention study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(6), 942–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.12.025

Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Song, J., Gwadz, M., Lee, M., Van Rossem, R., & Koopman, C. (2003). Reductions in HIV risk among runaway youth. Prevention Science, 4(3), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024697706033

Rubin, D. H., Erickson, C. J., San Agustin, M., Cleary, S. D., Allen, J. K., & Cohen, P. (1996). Cognitive and academic functioning of homeless children compared with housed children. Pediatrics, 97(3), 289–294.

Ruzycki, S. M., & Ahmed, S. B. (2022). Equity, diversity and inclusion are foundational research skills. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(7), 910–912. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01406-7

Sanders, B., Lankenau, S. E., Jackson-Bloom, J., & Hathazi, D. (2008). Multiple drug use and polydrug use amongst homeless traveling youth. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 7(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640802081893

Sanders, C., Burnett, K., Lam, S., Hassan, M., & Skinner, K. (2020). “You need ID to get ID”: A scoping review of personal identification as a barrier to and facilitator of the social determinants of health in North America. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124227

Santa Maria, D., Padhye, N., Businelle, M., Yang, Y., Jones, J., Sims, A., & Lightfoot, M. (2021). Efficacy of a just-in-time adaptive intervention to promote HIV risk reduction behaviors among young adults experiencing homelessness: Pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(7), e26704. https://doi.org/10.2196/26704

Saperstein, A. M., Lee, S., Ronan, E. J., Seeman, R. S., & Medalia, A. (2014). Cognitive deficit and mental health in homeless transition-age youth. Pediatrics, 134(1), e138-145. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-4302

Shein-Szydlo, J., Sukhodolsky, D. G., Kon, D. S., Tejeda, M. M., Ramirez, E., & Ruchkin, V. (2016). A randomized controlled study of cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress in street children in Mexico City. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 29(5), 406–414. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22124

Skott-Myhre, H. A., Raby, R., & Nikolaou, J. (2008). Towards a delivery system of services for rural homeless youth: A literature review and case study. Child & Youth Care Forum, 37(2), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-008-9052-8

Slesnick, N., Erdem, G., Bartle-Haring, S., & Brigham, G. S. (2013a). Intervention with substance-abusing runaway adolescents and their families: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(4), 600–614. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033463

Slesnick, N., Feng, X., Guo, X., Brakenhoff, B., Carmona, J., Murnan, A., Cash, S., & McRee, A. L. (2016). A test of outreach and drop-in linkage versus shelter linkage for connecting homeless youth to services. Prevention Science, 17(4), 450–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0630-3

Slesnick, N., Guo, X., Brakenhoff, B., & Bantchevska, D. (2015). A comparison of three interventions for homeless youth evidencing substance use disorders: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 54, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2015.02.001

Slesnick, N., Guo, X., & Feng, X. (2013b). Change in parent- and child-reported internalizing and externalizing behaviors among substance abusing runaways: The effects of family and individual treatments. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(7), 980–993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9826-z

Slesnick, N., & Prestopnik, J. L. (2005). Ecologically based family therapy outcome with substance abusing runaway adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 28(2), 277–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.02.008

Slesnick, N., & Prestopnik, J. L. (2009). Comparison of family therapy outcome with alcohol-abusing, runaway adolescents. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 35(3), 255–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00121.x

Slesnick, N., Prestopnik, J. L., Meyers, R. J., & Glassman, M. (2007). Treatment outcome for street-living, homeless youth. Addictive Behaviors, 32(6), 1237–1251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.010

Slesnick, N., Zhang, J., Feng, X., Wu, Q., Walsh, L., & Granello, D. H. (2020). Cognitive therapy for suicide prevention: A randomized pilot with suicidal youth experiencing homelessness. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 44(2), 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-019-10068-1

Slesnick, N., Zhang, J., & Yilmazer, T. (2018). Employment and other income sources among homeless youth. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 39(3), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-018-0511-1

State Laws to Support Youth Experiencing Homelessness. (2023). SchoolHouse Connection. Retrieved 6/5/2023 from https://schoolhouseconnection.org/state-laws-to-support-youth-experiencing-homelessness/

A State-by-State Guide to Obtaining ID Cards. (2016). National Network for Youth. https://nn4youth.org/a-state-by-state-guide-to-obtaining-id-cards/

Sterne, J. A., Hernán, M. A., Reeves, B. C., Savović, J., Berkman, N. D., Viswanathan, M., Henry, D., Altman, D. G., Ansari, M. T., Boutron, I., Carpenter, J. R., Chan, A.-W., Churchill, R., Deeks, J. J., Hróbjartsson, A., Kirkham, J., Jüni, P., Loke, Y. K., Pigott, T. D., & Higgins, J. P. (2016). ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ, 355, i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

Stewart, M., Reutter, L., & Letourneau, N. (2007). Support intervention for homeless youths. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 39(3), 203–207.

United States Code. (2020). General definition of homeless individual. Supplement 3, Title 42 - The public health and welfare.

Thompson, R. G., Aivadyan, C., Stohl, M., Aharonovich, E., & Hasin, D. S. (2020). Smartphone application plus brief motivational intervention reduces substance use and sexual risk behaviors among homeless young adults: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 34(6), 641–649. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000570

Thompson, R. G., Jr., Elliott, J. C., Hu, M. C., Aivadyan, C., Aharonovich, E., & Hasin, D. S. (2017). Short-term effects of a brief intervention to reduce alcohol use and sexual risk among homeless young adults: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Addiction Research & Theory, 25(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2016.1193165

Tobias, J. K., Richmond, C. A. M., & Luginaah, I. (2013). Community-based participatory research (Cbpr) with indigenous communities: Producing respectful and reciprocal research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 8(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2013.8.2.129

Toro, P., Lesperance, T., & Braciszewski, J. (2011). The heterogeneity of homeless youth in America: Examining typologies. Homelessness research institute. http://endhomelessness.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/heterogeneity-of-homelessness.pdf

Tucker, J. S., D’Amico, E. J., Ewing, B. A., Miles, J. N., & Pedersen, E. R. (2017). A group-based motivational interviewing brief intervention to reduce substance use and sexual risk behavior among homeless young adults. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 76, 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.02.008

Tucker, J. S., Linnemayr, S., Pedersen, E. R., Shadel, W. G., Zutshi, R., DeYoreo, M., & Cabreros, I. (2021). Pilot randomized clinical trial of a text messaging-based intervention for smoking cessation among young people experiencing homelessness. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 23(10), 1691–1698. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab055

Wang, J. Z., Mott, S., Magwood, O., Mathew, C., McLellan, A., Kpade, V., Gaba, P., Kozloff, N., Pottie, K., & Andermann, A. (2019). The impact of interventions for youth experiencing homelessness on housing, mental health, substance use, and family cohesion: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1528. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7856-0

Watters, C., & O’Callaghan, P. (2016). Mental health and psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents in street situations in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Child Abuse and Neglect, 60, 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.09.002

Wilens, T. E., & Rosenbaum, J. F. (2013). Transitional aged youth: A new frontier in child and adolescent psychiatry. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(9), 887–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.04.020

Wu, Q., Zhang, J., Walsh, L., & Slesnick, N. (2020). Family network satisfaction moderates treatment effects among homeless youth experiencing suicidal ideation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 125, 103548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103548

Wu, Q., Zhang, J., Walsh, L., & Slesnick, N. (2022). Heterogeneous trajectories of suicidal ideation among homeless youth: Predictors and suicide-related outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579422000372

Wu, Q., Zhang, J., Walsh, L., & Slesnick, N. (2022b). Illicit drug use, cognitive distortions, and suicidal ideation among homeless youth: Results From a randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 53(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2021.06.004

Yates, G. L., MacKenzie, R., Pennbridge, J., & Cohen, E. (1988). A risk profile comparison of runaway and non-runaway youth. American Journal of Public Health, 78(7), 820–821. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.78.7.820

Yates, G. L., Pennbridge, J. N., MacKenzie, R. G., & Pearlman, S. (1990). A multiagency system of care for runaway/homeless youth (Missing Children: The Law Enforcement Response, Issue. N. C. J. R. Service.

Zhang, J., & Slesnick, N. (2018). Substance use and social stability of homeless youth: A comparison of three interventions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32(8), 873–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000424

Zhang, J., Wu, Q., & Slesnick, N. (2021). Social Problem-solving and suicidal ideation among homeless youth receiving a cognitive therapy intervention: A moderated mediation analysis. Behavior Therapy, 52(3), 552–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2020.07.005

Funding

Funding was provided by National Institute on Drug Abuse, 3K12DA000357-22S1, Colin W. Burke.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

Timothy E. Wilens, MD: Dr. Wilens has co/edited books: ADHD in Adults and Children (Cambridge University Press), Straight Talk About Psychiatric Medications for Kids (Guilford Press), An Update on Pharmacotherapy of ADHD (Elsevier Press). Dr. Wilens has a licensing agreement with Ironshore (BSFQ Questionnaire). He is a consultant for 3D Therapeutics and serves as a clinical consultant to the US National Football League (ERM Associates), U.S. Minor/Major League Baseball, Gavin Foundation and Bay Cove Human Services. He has received funding from NIDA grant UH3DA050252. No further disclosures or conflicts to report. Colin W. Burke, MD: Dr. Burke has received funding from Harvard Medical School Zinberg Fellowship in Addiction Psychiatry Research; Massachusetts General Hospital Louis V. Gerstner Research Scholarship; NIH via the AACAP-NIDA Career Development Award in Substance Use Research (K12), Award Number 3K12DA000357-22S1. No further disclosures or conflicts to report. The remaining authors have no funding, disclosures, or conflicts to report.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval and informed consent were not required given that this study is a review of the existing literature.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lanni, S., Stone, M., Berger, A.F. et al. Design, Recruitment, and Implementation of Research Interventions Among Youth Experiencing Homelessness: A Systematic Review. Community Ment Health J 60, 722–742 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-023-01224-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-023-01224-9