Abstract

Public stigma is one barrier to accessing behavioral health care among Vietnamese Americans. To explore and identify features of culture and acculturation that influence behavioral health-related stigma, six focus groups were conducted with Vietnamese American participants in three generational groups and eleven key informant interviews were conducted with Vietnamese community leaders, traditional healers, and behavioral health professionals. Data were analyzed using Link and Phelan’s (Annu Rev Sociol 27(1):363–385, 2001) work on stigma as an organizing theoretical framework. Findings underline several key cultural and generational factors that intersect to affect perceptions, beliefs, and stigma about mental health treatment. In particular, participants in the youngest groups highlighted that while they recognized the value of mental health services, they felt culturally limited in their access. This appeared to be closely related to intergenerational communication about mental health. The findings suggest avenues for further research as well as interventions to increase mental health treatment access and adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The underutilization of mental health care and disparities in service access and outcomes among Asian Americans, including Vietnamese, have been attributed to a large extent to stigma and cultural characteristics of this population (Augsberger et al. 2015; Han et al. 2015; Jang et al. 2009; Jimenez et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2019; Leung et al. 2010; Masuda and Boone 2011; Spencer et al. 2010; Ta et al. 2018; Wynaden et al. 2005). Many Asian ethnic groups have cultural values of collectivity, filial piety, and holistic views of emotional and physical health, which can be incongruent with American values of independence and mind/body dualism (Leung et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2019; Masuda and Boone 2011; Wynaden et al. 2005). For recent Asian immigrants to the United States, especially resettling refugees from Southeast Asia, there can be significant barriers to diagnosing and treating mental illness. These barriers can include lack of adequate health insurance, limited culturally and linguistically accessible services, and providers’ lack of knowledge about the needs of different ethnic groups (Wynaden et al. 2005).

Despite the large number of studies on the role of culture in mental illness (MI) stigma among Asian Americans, research and programming continue to be challenged by the heterogeneity among Asian Americans (Abdullah and Brown 2011; Africa and Carrasco 2011; Chu and Sue 2011; Sue et al. 2012). The Asian American population consists of more than 50 distinct ethnic groups with much cultural variation in the way MI is perceived (Chu and Sue 2011). There is a critical need for further scholarship in this diverse group as it has implications to how service providers interpret and classify psychological symptoms, affecting the diagnosis and management of mental disorders among Asian American ethnic groups (Sue et al. 2012).

Vietnamese are the fourth largest Asian immigrant group in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau 2012). Vietnamese immigration to the US has occurred in three major waves (Han et al. 2015): (1) after the American military withdrew from Saigon, leading to the Fall of Saigon in 1975; (2) from the late 1970s to the early 1980s when many Vietnamese escaped by boat, enduring unimaginable hardship at sea, risking their life, and spending extended time in refugee camps (Ngo et al. 2000); and (3) from the late 1980s with the passage of the Orderly Departure Program and the Amerasian Homecoming Act (Bankston 2012; Kumin 2008). This immigration pattern generated different needs for services, including counseling and social services, for different generations of Vietnamese immigrants as they settled in the US and experienced different immigration and acculturation related stressors (Cheung et al. 2017; Kim-Mozeleski et al. 2018).

In Vietnamese culture, mental disorders are often labeled điên (literally translated as “madness”). A điên person and their family are often severely disgraced and consequently they become reluctant to disclose and seek help for mental health problems for fears of rejection (Sadavoy et al. 2004). Key cultural values, such as familism, put priority on families over individuals, resulting in those with MI being likely to hide it to protect their family’s reputation (Cheung et al. 2017; Nguyen and Anderson 2005). MI is also often seen as a sign of weakness (Haque 2010) or possession by supernatural entities (Kinzie 1985; Nguyen and Anderson 2005). Furthermore, because of how MI was managed in Vietnam, Vietnamese often associate it with being institutionalized and imprisoned, which contribute to increasing MI related stigma (Böge et al. 2018; Cheung et al. 2017).

For many Vietnamese immigrants in the United States, mental health is experienced within a specifically Vietnamese cultural context. In this culture, mental health disorders may be considered a consequence of one’s improper behavior in a previous life, for which the person is now being punished (Nguyen 2003). Mental disorders can also be seen as a sign of weakness, contributing to avoidance of help seeking (Fong and Tsuang 2007). Equally important is the need to protect family reputation; having emotional or mental health symptoms often implies that the person has “bad blood” or is being punished for the sins of his/her ancestors (Herrick and Brown 1998; Leong and Lau 2001), which disgraces the entire family (Wynaden et al. 2005).

Stigma is a complex construct that warrants a deeper and more nuanced understanding. In his classic work, Goffman (1986) defines stigma as a process by which an individual internalizes stigmatizing characteristics and develops fears and anxiety about being treated differently from others. Public stigma, defined by Corrigan (2004), includes the general public’s negative beliefs about specific groups that contribute to discrimination against such groups. Public stigma toward MI not only is associated with lower engagement in care, as well as lower retention and adherence to care, but can also exacerbate anxiety and depression (Britt et al. 2008; Corrigan and Shapiro 2010; Keyes et al. 2010; Link et al. 1999; Pescosolido et al. 2007; Sirey et al. 2001). While a robust exploration of stigma in general exists, a review of studies conducted with probability samples of non-institutionalized adults and children in the United States reported 36 published articles on public stigma and only three of them included Asian Pacific Islanders (Parcesepe and Cabassa 2013). This study aimed to fill this gap in the literature on MI related public stigma experienced by Vietnamese people.

According to Corrigan (2004), public stigma relies on four cues: psychiatric symptoms, lack of social skills, unusual physical appearance, and labels as an indication of MI. These cues elicit stereotypes, which lead to prejudice and result in discrimination (Corrigan 2007). However, this definition of public stigma tends to focus on the relationships between attributes, labels, and stereotypes, and puts emphasis on cognitive processing of information rather than on the discrimination that a person with an undesirable attribute experiences (Link and Phelan 2001; Link et al. 2004).

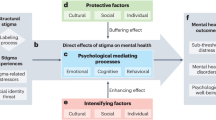

In this paper, we employed Link’s and Phelan’s (2001) framework to organize public stigma into four major components that are interrelated and convergent; discrimination experiences are incorporated into this framework. The first component, labeling, occurs when people distinguish and label human characteristics that are socially relevant, e.g. skin color. In the second component, stereotyping, cultural beliefs link the labels to undesirable characteristics either in the mind or the body of such persons, e.g. people who are mentally ill are violent. The third component is separating “us” (people without MI) from “them” (people with mental disorders) by the public. Finally, labeled persons experience status loss and discrimination, where they are devalued, rejected and excluded. Link and Phelan (2001) emphasized that stigmatization also depends on access to social, economic and political power that allows these components to unfold.

In addition to research on cultural influences on stigma, a number of studies of immigrants in the United States have examined generation status and mental health outcomes but have often reported conflicting findings (Chang et al. 2013; Montazer and Wheaton 2011; Ta et al. 2010). For example, Cervantes et al. (2013) reported more stress and mental health symptoms among first generation Hispanic adolescents, compared to second generation immigrants, and the second generation reported a greater number of stressors than the third generation immigrants; yet the second group had more delinquent and aggressor behaviors than first generation immigrants. Other studies, however, reported no significant differences in psychotic disorders between generations (Bourque et al. 2011). A few studies also reported generational differences in the use of mental health services among immigrants (Chang et al. 2013; Ta et al. 2010); much of those differences were attributed to individual’s acculturation related stressors, adaptation process, as well as changes in family culture, cohesion, and conflicts. Jang et al. (2009) did not find across-generation differences in attitudes towards mental health services among Korean Americans, but reported more negative attitudes towards depression and the mentally ill among older adults compared to younger adults. This study aims to explore MI related public stigma within the cultural context of a major immigrant population, and its variations across generations.

While it is often acknowledged that different generations may have different risks and needs for mental health care, there has been little documentation of such differences. Few researchers have investigated MI and MI stigma among young Vietnamese Americans (Kamimura et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2019; Nguyen 2019). For example, Nguyen (2019) indicated huge gaps between Vietnamese American college students and their parents, the first-generation Vietnamese immigrants, in perceptions of MI, its causes and management, as well as cultural conceptions, despite a shared heritage. Acculturation and acculturative stress were often attributed for young adults’ deviations from traditional beliefs that their parents held. Consequently, young Vietnamese Americans were less likely than their parents to believe in karma, as well as to seek advice from their parents or help from outside since they were raised to be self-sufficient (Nguyen 2019).

In summary, previous studies have also shown that public stigma related to MI was prevalent, but have not investigated different domains of stigma or how it varies across generations (Do et al. 2014). This study aimed to answer the following research questions: (1) how do Vietnamese Americans perceive public stigma related to MI? and (2) how does MI related public stigma vary across generations of Vietnamese Americans? We investigated how Link and Phelan’s (2001) four components apply to stigma expressed by Vietnamese Americans and how these components varied across generations.

Study Setting

This study was set among Vietnamese Americans in New Orleans, Louisiana (LA), one of the major hubs of Vietnamese immigrants in the U.S. Like in other states, such as Virginia, California and Texas, many Vietnamese in New Orleans, LA live in a community somewhat separate from the rest of the city. Like Vietnamese immigrants elsewhere, they experienced traumatic events of the Vietnam War and the migration from Vietnam to the United States after the Fall of Saigon in 1975, among others. Previous studies have shown a low level of mental disorders post-disaster as well as extremely low level of mental and behavioral health care among this population (Do et al. 2014; Vu and VanLandingham 2012).

Methods

Sample

This study employed two samples: one of community members for focus group discussions (FGDs) and one of community leaders and care providers for key informant interviews (KIIs). The first sample, community members, was recruited by convenience sampling through personal contacts and referrals by the community partner. Recruitment was conducted to ensure a sample that represented three generations of Vietnamese Americans in New Orleans with the following age/immigration pattern categories: (1) individuals age 56 or older who were born and grew up in Vietnam and immigrated to the United States after age 35 (39.2%); (2) individuals age 36–55 who were born in Vietnam but spent a significant part of their youth in the United States (29.4%); and (3) individuals age 18–35 who were born and grew up in the United States (31.4%). The rationale for this classification was that differential awareness and stigmatizing attitudes towards MI across generations of immigrants have been documented in previous research (Cervantes et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2009). The final sample (see Table 1) included 51 participants aged 18 or older, including 24 men (53%) and 27 women (47%). One-third of our sample had at least some college education; nearly half of them had an annual household income of less than $30,000; one in four had between $30,000 and $70,000 of annual income. The majority of them (80.4%) were Catholic, the rest were Buddhist, Baptist or others.

The second sample of key informants included six service providers (3 male and 3 female) and five community and religious leaders (3 male and 2 female). Service providers included health care providers, psychologists, and traditional medicine providers (e.g., an acupuncturist). This sample was recruited purposely through professional contacts of the researchers, and referrals from the community partner to include those who were either directly involved in mental health care or had in-depth knowledge of the community and services available. While interviews with mental health care providers may reveal overlaps or gaps in perceptions of MI stigma between them and community members, interviews with community leaders are also key since previous research has suggested that they could be important influencers and gatekeepers in mental health service utilization (Dinh 2018; Kim-Mozeleski et al. 2018; Nguyen et al. 2012a, b). Our community partner, the New Orleans East Community Health Center, played a key role in recruiting for both samples.

Data Collection

Data were collected through FGDs with the sample of community members and KIIs with service providers and community leaders. The study was reviewed and approved by Tulane University’s Institutional Review Board; a written informed consent form was obtained from each study participant. A moderator guide for the FGDs and an interview guide for the KIIs were developed by the research team in English first (see "Appendices 1 and 2"), then translated into Vietnamese by the bilingual researcher. The FGD moderator guide included questions to explore the community’s perceptions of mental health and available resources, and to understand perceived barriers and support for seeking help. FGD participants were also asked to fill out a short survey to collect their basic demographic information, such as age, sex, education, household income, and when they moved to the United States, etc. Meanwhile, the KII guide was aimed to understand Vietnamese Americans’ access and utilization of behavioral and mental health care from the care system’s and leadership’s perspectives, and to understand the community’s strengths and resources in addressing mental health problems. In this study, we used mental illness as a general term (literally translated as “bệnh tinh thần” in Vietnamese) without any further description. Similar to “mental illness” in English, the term in Vietnamese is broad and can encompass different mental health conditions, from stress, depression, to schizophrenia. Interviewers purposely did not define mental illness for participants, and instead let participants use their own culturally grounded definitions of mental illness. Interview guides contained questions about both mental illness and substance use and while substance use was mentioned occasionally, it was never discussed in any depth in any of the focus groups. Thus, it was decided to omit this focus from the final data analysis.

FGDs were conducted separately for men and women, since previous research with Asian immigrants indicated that gender played an important role in reporting mental symptoms, service utilization, as well as family support and conflicts (Leu et al. 2011; Masood et al. 2009). In addition, Vietnamese women tend to be deferral to men in conversations with others, and in decision making (Gallina and Rozel Farnworth 2016; Leahy et al. 2017; Nguyen et al. 2012a, b); holding separate FGDs for women and men would allow women to speak more freely without undue influences from male community members and worries of how they might be perceived afterwards. For each gender, three separate FGDs were conducted with the three generational groups mentioned above, for a total of six FGDs. This was done, using the same FGD guide, in order to explore differences in perceptions of mental health and services between generations. Each FGD lasted between one and one and a half hour, was conducted in the language chosen by each group: FGDs with the youngest groups were conducted in English, whereas those with the middle and the oldest groups were conducted in Vietnamese. KIIs were conducted by the two researchers based mostly on the informant’s language preference. Each interview lasted between one and two hours.

To ensure consistency in interviewing techniques and content, the two principal researchers conducted together the first two FGDs and KIIs in English with participants who were also bilingual. At the end of these FGDs and KIIs, the researchers reviewed the outcomes of the interviews and discussed areas for clarification to avoid potential confusion for participants. Later on, each researcher conducted FGDs and KIIs separately, with the English-speaking researcher conducted those in English only and the bilingual researcher conducted interviews in either language, depending on what study participants were comfortable with. The fieldwork took place between October 2016 and March 2017; all FGDs and KIIs were audio recorded. Interviews were transcribed by two graduate research assistants, one of them also fluent in Vietnamese who then translated interviews conducted in Vietnamese into English. The transcripts were reviewed by both researchers, with the bilingual researcher conducting spot check of the transcripts to ensure the accuracy of the translation.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were imported into NVivo version 11 (QSR International Pty Ltd. 2015) for coding and analysis. The analysis process utilized a Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR) approach. CQR is a data analysis process that fosters multiple perspectives and uses a consensus process to arrive at judgments about the meaning of data, the development of domains, core-ideas, and cross-analysis (Hill et al. 2005). The focus group interviews were analyzed first and then key informant interviews were analyzed using the same methods to provide triangulation of findings. The two principal researchers read through each of the transcripts and developed broad categories. Transcripts were coded using these categories. The core ideas contained in each domain were summarized into categories and were then compared across groups (both gender and generations). Throughout the process the researchers compared coding processes and discussed discrepancies until consensus was reached. Using a didactive approach, emergent themes were organized into major categories, such as components of public stigma according to Link and Phelan (2001). Intergenerational differences in stigmatizing attitudes were analyzed using an inductive approach. Draft reports were written and reviewed by everyone on the research team. All names used in this paper were pseudonyms.

Results

Three themes emerged from the data, each with corresponding sub-themes. The first theme organizes the data using Link and Phelan’s work as a framework. Therefore, subthemes correspond to components of public stigma within that framework. The second two themes capture emerging findings that further explicate or build on Link and Phelan’s work, but do not necessarily fit exactly with their components. The first two themes incorporate data from across all focus groups while the third theme explores generational differences between focus groups. These findings touch on specific aspects of Vietnamese cultural perceptions of mental illness across generations and the ways in which intergenerational relationships influence stigma.

Theme 1: Components of Public Stigma Related to Mental Illness

Our data showed evidence of stigma in general among Vietnamese Americans in New Orleans, that was voiced by FGD participants and acknowledged by key informants. However, the four components of public stigma were expressed to different extents within the study sample.

Component 1: Labeling

There was strong evidence of this component of public stigma among both FGD participants and key informants. Across groups of participants, participants agreed that it was a common belief that people with mental disorders were “crazy”, “not normal”, or “depressed”. However, there were clear meaning differences between younger and older Vietnamese. The youngest participants tended to recognize the “craziness” and “madness” as a health condition that may require professional treatment, whereas the oldest groups often stated that these conditions were short-term and likely caused by family or economic problems, such as a divorce, or a bankruptcy.

Our key informants acknowledged that people with MI were often labeled this way, and that “Vietnamese always associate it [MI] with being crazy”. Some key informants, particularly lay community leaders, also characterized individuals with MI as “not normal”, “clueless”, or having a “broken mind”. A few key informants explained how labels prevented Vietnamese from acknowledging and talking about MI. One referred to a religious belief among the community that “for them, because they are Catholic, they shouldn’t be crazy.” Others linked the label with the lack of vocabulary to describe MI, which would be discussed in detail later, as a reason for Vietnamese to avoid talking about MI. As this was an “illness” that is hard to observe by an outsider because there may not be any physical symptoms, Vietnamese people would try to avoid admitting that they had an illness that might not be “real.” A social worker, Ms. Lan, said “They don’t want to admit it [an illness]. They don’t want to get that label.”

Component 2: Stereotyping

The evidence supporting the second component, stereotyping, was not strong among Vietnamese Americans. Most FGD participants agreed that while those with mental disorders might act differently, they were not distinguishable. In a few extreme cases, mentally ill individuals were described as petty thefts or being violent towards their family members.

Component 3: Separating “Us” from “Them”

Similar to the lack of strong evidence of stereotyping, there was also no evidence of the public separating the mentally ill (“them”) from “us”. It was nearly uniformly reported that participants felt sympathetic to those with mental disorders and their family, and that all recognized that they needed help, although what was appropriate help was perceived differently across groups. The older participants often saw that emotional and financial support was needed to help individuals and families to pass through a temporary phase, whereas younger participants often reported that professional help was necessary.

Component 4: Status Loss and Discrimination

The last component, status loss and discrimination, also had strong evidence from participants. Words like “discrimination” and “stigma” were often used in all FGDs to describe direct social consequences of having a mental disorder. Social exclusion was very common. Our older participants said, “They see less of you, when they see a flaw in you they don’t talk to you or care about you. That’s one thing the Vietnamese people are bad at, spreading false rumors and discrimination.” (Mrs. Mot, older women FGD).

One’s loss of status seemed certain if their or their loved one’s mental health status was disclosed. Shame, embarrassment, being “frowned upon” and gossiped about were direct consequences of one’s mental health status disclosure. This was a prominent theme that emerged from both FGDs and interviews with our key informants. One young man said, “You get frowned upon. In the Vietnamese culture, that’s the big no–no right there. When everybody frowns upon your family and your family name, that’s when it becomes a problem.” (Mr. Khai, young men FGD).

This was tied directly to what our participants described as Vietnamese culture, where pride and family reputation were such a high priority that those with mental disorders needed to go to a great extent to protect—“We all know what saving face means” as reported by several of our young participants. Even among young participants, despite their awareness of MI and the need for professional help, the desire to avoid embarrassment and save face was so strong that one would think twice about seeking help.

No, you just don’t want to get embarrassed. I don’t want to go to the damn doctor and be like “Oh yeah, my brother got an issue. You can help him?” Why would I do that? That’s embarrassing to myself… (Mr. David, young men FGD)

Our middle-aged participants also reported,

If I go to that clinic [mental health or counseling clinic], I am hoping and praying that I won’t bump into somebody that I know from the community. (Mrs. Ba, middle-aged women FGD)

The same challenge was reported by a psychiatrist dealing with Vietnamese patients on a daily basis:

At first when I started seeing Vietnamese clients, the first client said “Doctor R., many people are not going to come to you.” She said “Now before you, there was this - I don’t know was it a social worker or someone who was working in this community and she babbled. She babbled some story or something, and it did not take long. The whole community found out.” (Psychiatrist 2)

Vietnamese people were also described as being very competitive among themselves, which led to the fact that if a family was known for having any problem, gossip would spread quickly and soon the family would be looked down by the entire community. One older woman said, “I think for Vietnamese people, they don’t help those that are in need. They know of your situation and laugh about it, see less of you, and distant themselves from you.” (Mrs. Vui, older women FGD).

Fears of being gossiped about, coupled with the need to protect the reputation of one’s extended family at all costs was well recognized by all of the Vietnamese speaking psychologists and psychiatrists that we interviewed. These providers also reported a struggle that they often faced in practice and in daily life: while they were usually preferred by Vietnamese Americans over English speaking providers, it was also much harder for them to gain trust of their Vietnamese clients as clients would fear that Vietnamese psychologists would spread gossip themselves. A Vietnamese psychiatrist who had been part of the community for more than two decades reported:

When I go to the Vietnamese community for any kind of festivals, like Chinese New Year, I have to be very low key. I have to make myself very, very invisible. If they know that I am visible in the community, they could be suspicious. They don’t want to have anything to do with me if they run into me. (Psychiatrist 1)

A community leader, Mrs. Catherine, used to house a psychiatrist’s office within her office in an attempt to provide more services to the community, described how they dealt with potential stigma:

People come [to this office] and they just go straight back there. I don’t pay attention… I think because we make it very seamless, like it’s no big deal, and I think a lot of them were benefiting from it greatly…. [omitted” they are not having to sit there and then get nervous that somebody’s gonna call their neighbor and say “Oh Dr. So-and-so is seeing so-and-so.” (Community leader)

Theme 2: Culture, Context, and Mental Illness

Sub-theme 1: Resilience

Mental disorders were reportedly seen as conditions that individuals and families needed to overcome on their own, rather than asking for help from outsiders. Many study participants across FGDs, as well as key informants, also emphasized a belief that Vietnamese Americans were often known for their perseverance and resilience, overcoming the hardships related to wars and natural disasters on their own. Interestingly, this belief was seen as a positive feature of the culture by some key informants, but a negative one by others, with regard to mental health. For example, an acupuncturist said:

The hardship in Vietnam creates good personalities and traits within people. The wisdom, quality of thinking, traits of patience, outlook of life, etc. makes us good. For example, the lotus flowers grow in muddy points [Vietnamese proverb], meaning there is beauty in the ugly. Americans have it too easy so they have it worse [when it comes to hardship]. (Acupuncturist)

Ms. Catherine, a community leader said “We don’t want to be labeled. We’ve worked too damn hard [throughout migration and resettlement processes] to be labeled that way and sometimes we don’t want to talk about it. We walk away from it.” The pride and the resilience that may be a strength that helped Vietnamese go through that long journey and build their life in a new land may also be a barrier to talking about MI.

In this school of thought, the hardship that Vietnamese have endured through decades made mental problems like stress and depression much more temporary and easier to overcome on one’s own. Another school of thought shared by other key informants, however, was that because “you are supposed to be strong. You have been through a lot already, you should be able to be strong” (reported by a priest), which made Vietnamese not believe in mental health and mental problems. Consequently, Vietnamese Americans were reluctant to acknowledge or talk about mental problems.

Sub-theme 2: Family Obligation

The aspect of resilience and self-reliance in the Vietnamese culture was intertwined with the need to protect one’s family’s reputation, being passed on from one generation to the next, reinforcing the beliefs that help for mental disorders should come from within oneself and one’s family only. Consequently, persons with mental health problems would be “Keeping it to themselves. Holding it in and believing in the power of their friends” (Mr. Toan, middle-aged men FGD) instead of seeking help.

Protection of family’s grace and reputation, as well as Vietnamese gossiping habits (perceived or real) mentioned above were prominent cultural features tied with stigmatizing attitudes related to MI. Familiasm and community cohesiveness, particularly within a small and close-knit one in New Orleans, further fosters individuals’ and families’ avoidance to lose ‘face’ and their status in the community. On the other hand, such cohesiveness within families and communities could also contributed to the lack of separation of the mentally ill from the family and the community. In addition, much of the described stigma and discrimination expressed, and consequently the reluctance to seek help, was attributed to the lack of awareness of mental health and of mental disorders.

Sub-theme 3: Mistrust of Modern Medicine

Another sub-theme that was apparent from FGDs as well as many KIIs was the mistrust in Western medicine. Not understanding how counseling or medicines work made one worry about approaching service providers or staying in treatment: “Growing up in Vietnam, we never got to go to the therapist so we don’t know how it is like.” (An acupuncturist) For many Vietnamese people treatment was only sought when experiencing physical symptoms. This hindered acknowledgement of MI and help-seeking.

Sub-them 4: Language Issues

Challenges, including the lack of vocabulary to express MI and symptoms, in the Vietnamese language, exacerbated the problem, even among those who had some understanding of mental disorders. One young man said, “When you classify depression as an illness, no one wants to be sick,… if you call it an illness, no one wants to have that sort of illness, and it’s not an illness that you can physically see…” (Mr. Jimmy, young men FGD).

Several key informants, including care providers and community leaders, raised the same issue with language. To many Vietnamese, MI was a “too heavy” word – in part because of the stigma around it, and in part because very few people understood what it meant. A word loaded with stigma, without a clear and tangible meaning, led to avoidance of using the word itself, which in turn may contribute to the persistence of perceived taboo around it. One of the psychologists interviewed said “In English, when we joke we say “Are you crazy?” It’s just a joke. It is something lighthearted, nothing serious. In Vietnamese if you say that “Mày điên à?” (Are you crazy?) it’s like putting down.”

The above-mentioned sub-themes were interrelated in the way Vietnamese Americans perceived public stigma towards MI. A young man in our focus groups summarized so well the influence of culture on MI stigma:

Us Southeast Asian, like, from my parents specifically as Vietnam War refugees. I think the reason why they don’t talk about it is because it’s a barrier that they have to overcome themselves, right? As refugees, as people who have been through the war…They don’t want to believe that they need help, and so the trauma that they carry when they give birth to us is carried on us as well. But due to the language barrier and also the, like, they say with the whole health care, in Vietnam I know that they don’t really believe in Western and Eurocentric medicine. So, from their understanding of how, like from their experience with colonization or French people, and how medicine works, they don’t believe in it. (Mr. Washington, young men FGD)

Theme 3: Differences in Mental Illness Stigma Across Generations

Marked differences were reported between the three age groups included in this study. Two key sub-themes were prominent and reported by all age groups.

Sub-theme 1: Acculturation

It was widely agreed by our FGD participants and key informants that the young generation was exposed to and influenced by the American culture, and therefore more open-minded than the older generations. A community leader whose age was comparable with our elder participants said:

… the younger generation are exposed to American culture. Their attitude seems to be half of this and half of that because they are influenced…. [omitted] For us, we still hold on to culture because we are traditional, have the dragon dance, etc. (Priest)

In several FGDs and KIIs, this difference was reported to contribute to differences in perceptions towards MI. For example, the young generation understood that MI was a health problem that was prevalent but less recognized in the Vietnamese community, whereas a prominent theme among the participants in the two older age groups was that MI was a temporary condition due to psychological stress, that it was a condition that only Caucasians had. Consequently, the providers we interviewed often reported that it was in general much harder to talk to people of middle age and older about MI among themselves or their children. A health care provider, Dr. Smith, said:

The younger folks – it’s pretty much like the other populations we care for. Their presentation doesn’t differ much from our standard primary care population…. [omitted] The older populations are the ones that typically don’t like to bring it up. (Health care provider)

Some of the components of public stigma related to MI seemed to vary between generations, e.g. the youngest participants were less likely to put a label on a person with mental health problems, compared to the oldest and middle-aged participants. This was attributed to their education, exposure to the media and information, and to them “being more Americanized”. However, there was little evidence of across-generation differences in other components of public stigma, including stereotyping, separating, and status loss and discrimination. For example, the need to protect the family reputation was so important that our young participants shared, “If you damage their image, they will disown you before you damage that image.” (Mr. Su, young men FGD).

Young people, more likely to recognize mental health problems, were also more likely to share with their close friends and to seek help, but no more likely than their older counterparts to share outside of the family—“maybe you would go to counseling or go to therapy, but you wouldn’t tell people you’re doing that.” (Ms. Sau, young women FGD). The youngest participants in our study were facing a dilemma, in which they recognized mental health problems and the need for care, yet were still reluctant to seek care or talk about it publicly because of fears of damaging the family reputation and not living up to the parents’ expectations.

Sub-theme 2: Being “Closed Off” and Pressure from Parents

One characteristic of the Vietnamese culture that was also often mentioned by our FGD participants, as well as KIIs, was the lack of sharing and openness between generations, even within a family. Grandparents, parents, and children did not usually share and discuss each other’s problems. Ms. Catherine, a community leader, who was in her 40s, said:

Sharing and talking doesn’t happen in our culture. I came over to America in 1975 at the age of five. I can’t remember a single day, a single time, when I was young when my mom and dad sat down and we talk about how we feel. I grew up in a family – and nothing wrong. I mean my parents provided, good parents, but we just never did that. (Community leader)

Parents and grandparents did not talk about problems because they needed to appear strong and good in front of their children; children did not talk about problems because they were supposed to do well in all aspects, particularly in school. The competitiveness of Vietnamese and high expectations of younger generations again came into play here and created a vicious cycle. Young people were expected to do well in school, which put pressure on them and may result in mental health problems, yet, they could not talk about it with their parents because they were not supposed to feel bad about school, and sharing was not encouraged. The Asian model minority myth and the expectations of parents that their children would do well in school and become doctors and lawyers were cited by many as a cause of mental health problems among young people.

Our parents are refugees, they had nothing and our parents want us to achieve this American Dream…. It set expectations and images for us…. It was expected for all the Asians to be in the top 10, and for, like a little quick minute I thought I wasn’t going to make it, I was crying. (Mr. Trung, young men FGD)

This sentiment was echoed by the priest that we mentioned above:

They [parents] believe that you [the younger generation] have to be strong. You are supposed to be strong. You have been through a lot already, so you should be able to be strong. (Priest)

As a result, the mental health problems got worse.

If you’re feeling bad about something, you don’t feel like you can talk about it with anyone else, especially your family, because it is not something that is encouraged to be talked about anyway, so if you are feeling poorly and you don’t feel like you could talk to anybody, I think that just perpetuates the bad feelings. (Mrs. Nam, middle aged women FGD)

While acculturation might help young Vietnamese Americans more likely to recognize mental health issues and less likely to report stigma, pressure from the older generations and being closed off to them seemed to prevent young adults to be truly open about MI and to seek professional care. Because of such internal conflicts, many young participants reported that it actually made it very difficult for them to navigate mental health issues between the two cultures, despite the awareness of the resources available.

I think it actually makes it harder. Only because you know to your parents and the culture, and your own people, it’s taboo, and it’s something that you don’t talk about. Just knowing that you have the resources to go seek it… You want advice from your family also, but you can’t connect the appointment to your family because you’re afraid to express that to your parents, you know? So, I think that plays a big part, and knowing that you are up and coming, but you don’t want to do something to disappoint your family because they are so traditional. (Mr. David, young men FGD)

Some participants felt more comfortable talking about mental health problems, like depression, if it was their friend who experienced it and confided in them, but they would not necessarily felt open if it was their problem. One older participant summarized it well “They [the young generation] are more Americanized. They are more open to other things [but] I think that mental health is still a barrier” (Mr. Toan, older men FGD).

Discussion

This study investigated how different components of public stigma related to MI were perceived among Vietnamese Americans from both the community and providers’ perspectives. This study contributes to the literature in this topic in several ways. First, it was focused on a single large Asian immigrant population rather than taking all Asian immigrants as a homogenous group. Second, it explored public stigma related to MI from both the community and providers perspectives, which has rarely been done (Cox 2018). Third, the study highlighted the inter-connection between cultural beliefs and generational differences, which also has not been done in a few studies that examined stigma differences between generations or age (Kim et al. 2019; Laqua et al. 2018).

Link and Phelan’s (2001) framework was employed to organize MI public stigma into four components. The findings highlighted labeling and status loss and discrimination as prominent components of MI public stigma among Vietnamese Americans, and showed less evidence of stereotyping and separation components. Many of our findings are consistent with previous research. For example, the apparent evidence of labeling and fears of being labeled as “mentally ill” that contributed significantly to stigmatizing attitudes has been documented with Vietnamese immigrants in the U.S. (Bui et al. 2018; Nguyen et al. 2012a, b).

The lack of strong evidence of stereotyping among our study sample is in contrast with some previous studies (Parcesepe and Cabassa 2013) which showed that Asian Pacific Islanders were more likely to perceive people with MI as dangerous – an expression of stereotyping (Anglin et al. 2006; Corrigan and Watson 2007). A possible explanation is that our study sample included individuals who lived in a very close-knit community, many of them came from the same original village in northern Vietnam, migrated together to southern Vietnam in the mid-1950s and eventually to the U.S. after the Fall of Saigon in 1975 (Do et al. 2009; Vu and VanLandingham 2012). It is plausible that such shared experiences may have enhanced the community cohesiveness, which in turn contributed to the lack of explicit stereotyping and separation. In addition, the heterogeneity within Asian Pacific Islanders themselves may have masked the Vietnamese American’s experiences when multiple ethnic groups were combined under this umbrella in previous studies.

We also found that strong cultural beliefs underlined the understanding of mental health and MI in general, and how people viewed the mentally ill. Several findings have been highlighted in previous studies with Asian immigrants; for example, a study from the perspectives of health care providers in Canada found that the unfamiliarity with Western biomedicine and spiritual beliefs and practices of immigrant women interacted with social stigma in preventing immigrants from accessing care (O'Mahony and Donnelly 2007). Fancher et al. (2010) reported similar findings regarding stigma, traditional beliefs about medicine, and culture among Vietnamese Americans. Cultural factors like fear of loss of face has also been reported to be associated with MI stigma and avoidance of seeking professional care (Bui et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2009; Leong et al. 2011; Umemoto 2004; Wong et al. 2010). Family-centered values have also been highlighted in previous studies with Vietnamese Americans as an important cultural notion that contributes to MI stigma (Nguyen 2019). Another key cultural factor emphasized by our participants was the lack of vocabulary in the Vietnamese language to describe mental health and MI. There may be a vicious cycle: because MI is considered a taboo, it is not talked about among Vietnamese, which contributes to the lack of vocabulary, which in turns prevents Vietnamese from talking about it.

Consistent with previous studies on MI stigma (Jang et al. 2009; Pedersen and Paves 2014), we found some differences between generations in stigmatizing attitudes, particularly between the youngest group and the two older groups of participants. However, on the whole, being younger did not equate to being more open, having fewer stigmatizing attitudes, or being more willing to seek care for mental health issues. Stigmatizing attitudes still existed among young people aged 18–35, although some components of stigma seemed less apparent compared to the older groups. For example, our youngest participants were less likely to report labeling than the middle-aged and the oldest participants. There was also a conflict among the younger generation, in which the need for mental health care was likely recognized but accessing care was no easier for them than for older generations. Our participants often attributed these differences to differences in cultural beliefs and the level of acculturation between generations, as mentioned above. Difficulties in balancing two different cultures and obligations to uphold family cultural values were key challenges to the young Vietnamese Americans in our study, similar to what was previously reported (Hovey et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2009; Nguyen 2019; Yeh et al. 2004). Similarly to our study, Nguyen (2019) reported that pressure from parents to succeed and to be self-sufficient kept young Vietnamese Americans from sharing mental and emotional concerns, even within the family. This is important in the context where young immigrants are more likely to have job- or school-related stressors, their sources of social support tend to be outside of the home, and family cohesion is decreasing (Jang et al. 2009; Ta et al. 2010). Young people will rely on someone—a friend, a colleague, a trusted community member—that is distant enough from their own family for support in case of MI and if/when the needs for mental health care arise, at least in the short term.

This study was designed to understand stigma as a barrier to accessing and adhering to mental health care among Vietnamese Americans. The results underline the need for culturally appropriate health care. Park et al. (2011) suggested three necessary characteristics of culturally appropriate mental health care for Asian Americans that are relevant here: (1) bicultural skills education for providers, (2) supporting families in transition from and to professional care, and (3) provider’s knowledge of Asian culture. While all of the health care givers interviewed in this study understood the public stigma related to MI, the Vietnamese psychiatrists came up with different ways to deal with such stigma, e.g. avoiding interactions with patients in public places. However, evidence-based practices that have been validated in mainstream populations should be tested and modified to meet cultural needs of Vietnamese Americans (Chu and Sue 2011). Understanding cultural biases related to reporting symptoms and care seeking among Vietnamese Americans will also encourage providers to spend time to build trust and reinforce confidentiality between providers and clients (Shannon et al. 2015), hence addressing a key barrier highlighted in this study—mistrust of providers for fear of being gossiped about.

The study underlines substantial public stigma towards the mentally ill in the Vietnamese American community, although its expression varied between generations. Results from FGD participants as well as community leaders and health care providers suggest that building trust between the community and providers is a critical first step to help the public overcome stigma. This is key in encouraging community members to share their problems and seek help, while preserving their identity and dignity (Böge et al. 2018; Dinh 2018). Recognition of potential language barriers in expressing mental health problems, acknowledging fears about seeking mental health care, and understanding a client’s cultural history and their expectations are some of the recommended ways to for mental and behavioral health care providers to build trust (Cheung et al. 2017; Logan 2017). Second, public education efforts at multiple levels (individual, group, and community) to increase the community’s knowledge of MI and address fears of being labeled and discriminated for acknowledging MI symptoms will also help reduce stigma. Nuanced interventions are needed to address challenges among different generations. For example, it may be useful to identify and introduce terminologies in Vietnamese and English for mental health that may be less offensive. Bui (2018) suggested that words like tâm trí (mind) could be less stigma inducing than tâm thần (mental health).

Additionally, interventions targeting the older generations may aim to increase understanding of MI and awareness of mental health services and service availability. Meanwhile, the younger generations may need support in solving cultural conflicts within themselves, navigating between the adaptation to the host society and maintaining Vietnamese culture, and how to address conflicts between generations in their family. Technology- and web-based interventions for sharing and receiving information may also be useful for young adults, without interfering with their attachments and interactions with the older generations and other members of the community (Sobowale et al. 2016). Similarly, building and enhancing a social support network for young people within the community may also contribute to their ability to solve cultural conflicts and address mental health care needs. It is also possible that addressing stigma among older Vietnamese Americans first may be efficient, although challenging, as reduced stigma among this generation may contribute to resolving the conflicts that young Vietnamese Americans are experiencing. Nevertheless, multilevel interventions may be needed for young Vietnamese Americans who were born in the U.S., as previous studies have shown that while they may be more acculturated that the older generations, they may have less cohesive familial bonds and are less likely to rely on family for support (Chang et al. 2013). In other words, stigma reduction efforts aiming to increase awareness and willingness to access mental health care will need to address both intrapersonal and familial conflicts among young Vietnamese Americans.

The study should be viewed in light of several considerations. First, the term “mental illness” was used very broadly in the study to indicate a condition that influences one’s feelings, mood and thinking. It may or may not affect one’s daily functions. In fact, while the majority of our study participants talked about major mental disorders with psychotic symptoms, a few also mentioned depression and substance use. Public stigma perceptions against individuals with various mental disorders can be very different; yet we were not able to discuss variations in such perceptions across disorders. Second, social desirability bias is possible. While our participants in both FGDs and KIIs were asked to reflect on past and present behaviors observed in the community, it cannot be ruled out that some responses may be influenced by the knowledge that the study’s long-term goal was to reduce MI related stigma among Vietnamese Americans. This may particularly be true with key informants who were service providers, many of whom have worked all their professional life to provider mental health services and support care seeking by community members. Consequently, they themselves were acutely aware of the need to increase MI awareness and lower stigma among Vietnamese Americans. Third, one should exercise cautions when they transfer the findings to Vietnamese Americans elsewhere. Although our Vietnamese American community has many in common with Vietnamese immigrants in the US, including the density and close-knit of the community and their migration history, many different community characteristics due to their size, location, and recent experiences with natural disasters may set our sample apart from other Vietnamese Americans. Finally, FGDs and KIIs were transcribed and translated concurrently by two graduate students, then reviewed by two researchers. The lack of professional translators or back translation may also raise concerns about the validity of the data. While the translation was reviewed by the bilingual researcher, a more systematic process that does not involve multiple transcribers and translators may increase the accuracy of the transcripts and enhance the understanding of the meanings of participant’s statements.

In conclusion, the study fills the gap in the literature on MI stigma among Vietnamese immigrants. It underscores the need to understand the nuances of stigma related to MI among Vietnamese Americans and highlights across-generation differences in public stigma. Findings suggest future multilevel directions for stigma reduction efforts, which need to be tailored to different age groups, and improving the cultural appropriateness of mental and behavioral care.

References

Abdullah, T., & Brown, T. L. (2011). Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review,31(6), 934–948.

Africa, J., & Carrasco, M. (2011). Asian-American and Pacific Islander mental health. Asian American Journal of Psychology,6(2), 107–116.

Anglin, D. M., Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2006). Racial differences in stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness. Psychiatric Services,57(6), 857–862. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.57.6.857.

Augsberger, A., Hahm, H. C., Yeung, A., & Dougher, M. (2015). Barriers to substance use and mental health utilization among Asian-American women: Exploring the conflict between emotional distress and cultural stigma. Paper presented at the Addiction Science & Clinical Practice

Bankston, C. (2012). Amerasian homecoming Act of 1988: Encyclopedia of diversity in education. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Böge, K., Hahn, E., Cao, T. D., Fuchs, L. M., Martensen, L. K., Schomerus, G., et al. (2018). Treatment recommendation differences for schizophrenia and major depression: A population-based study in a Vietnamese cohort. International Journal of Mental Health Systems,12(1), 70.

Bourque, F., van der Ven, E., & Malla, A. (2011). A meta-analysis of the risk for psychotic disorders among first-and second-generation immigrants. Psychological Medicine,41(5), 897–910.

Britt, T. W., Greene-Shortridge, T. M., Brink, S., Nguyen, Q. B., Rath, J., Cox, A. L., et al. (2008). Perceived stigma and barriers to care for psychological treatment: Implications for reactions to stressors in different contexts. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,27(4), 317–335.

Bui, Q. N., Han, M., Diwan, S., & Dao, T. (2018). Vietnamese-American family caregivers of persons with mental illness: Exploring caregiving experience in cultural context. Transcultural Psychiatry,55(6), 846–865.

Cervantes, R. C., Padilla, A. M., Napper, L. E., & Goldbach, J. T. (2013). Acculturation-related stress and mental health outcomes among three generations of Hispanic adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences,35(4), 451–468.

Chang, J., Natsuaki, M. N., & Chen, C.-N. (2013). The importance of family factors and generation status: Mental health service use among Latino and Asian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology,19(3), 236.

Cheung, M., Leung, P., & Nguyen, P. V. (2017). City size matters: Vietnamese immigrants having depressive symptoms. Social Work in Mental Health,15(4), 457–468.

Chu, J. P., & Sue, S. (2011). Asian American mental health: What we know and what we don't know. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture,3(1), 4.

Corrigan, P. (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist,59(7), 614–625. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614.

Corrigan, P. W. (2007). How clinical diagnosis might exacerbate the stigma of mental illness. Social Work,52(1), 31–39.

Corrigan, P. W., & Shapiro, J. R. (2010). Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clinical Psychology Review,30(8), 907–922.

Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2007). The stigma of psychiatric disorders and the gender, ethnicity, and education of the perceiver. Community Mental Health Journal,43(5), 439–458.

Cox, M. (2018). An exploratory study on mental illness perspectives in Hanoi.

Dinh, M.-H. N. (2018). Vietnamese buddhist Monks'/Nuns' and Mediums' views on attribution and alleviation of symptoms of mental illness. San Diego: Alliant International University.

Do, M. P., Hutchinson, P. L., Mai, K. V., & Vanlandingham, M. J. (2009). Disparities in health care among vietnamese new orleanians and the impacts of Hurricane Katrina. Research in the Sociology of Health Care,27, 301–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0275-4959(2009)0000027016.

Do, M., Pham, N. N. K., Wallick, S., & Nastasi, B. K. (2014). Perceptions of mental illness and related stigma among Vietnamese populations: Findings from a mixed method study. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health,16(6), 1294–1298.

Fancher, T. L., Ton, H., Le Meyer, O., Ho, T., & Paterniti, D. A. (2010). Discussing depression with Vietnamese American patients. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health,12(2), 263–266.

Fong, T. W., & Tsuang, J. (2007). Asian-Americans, addictions, and barriers to treatment. Psychiatry (Edgmont),4(11), 51.

Gallina, A., & Rozel Farnworth, C (2016). Gender dynamics in rice-farming households in Vietnam: A literature review.

Goffman, E. (1986). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Touchstone.

Han, M., Cao, L., & Anton, K. (2015). Exploring the role of ethnic media and the community readiness to combat stigma attached to mental illness among Vietnamese immigrants: The pilot project Tam An (Inner Peace in Vietnamese). Community Mental Health Journal,51(1), 63–70.

Haque, A. (2010). Mental health concepts in Southeast Asia: Diagnostic considerations and treatment implications. Psychology, Health & Medicine,15(2), 127–134.

Herrick, C. A., & Brown, H. N. (1998). Underutilization of mental health services by Asian-Americans residing in the United States. Issues Ment Health Nurs,19(3), 225–240.

Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, B. J., Williams, E. N., Hess, S. A., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology,52(2), 196.

Hovey, J. D., Kim, S. E., & Seligman, L. D. (2006). The influences of cultural values, ethnic identity, and language use on the mental health of Korean American college students. The Journal of Psychology,140(5), 499–511.

Jang, Y., Chiriboga, D. A., & Okazaki, S. (2009). Attitudes toward mental health services: Age-group differences in Korean American adults. Aging and Mental Health,13(1), 127–134.

Jimenez, D. E., Bartels, S. J., Cardenas, V., & Alegría, M. (2013). Stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness among racial/ethnic older adults in primary care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry,28(10), 1061–1068.

Kamimura, A., Trinh, H. N., Johansen, M., Hurley, J., Pye, M., Sin, K., et al. (2018). Perceptions of mental health and mental health services among college students in Vietnam and the United States. Asian Journal of Psychiatry,37, 15–19.

Keyes, K., Hatzenbuehler, M., McLaughlin, K., Link, B., Olfson, M., Grant, B., et al. (2010). Stigma and treatment for alcohol disorders in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology,172(12), 1364–1372.

Kim, I., Keovisai, M., Kim, W., Richards-Desai, S., & Yalim, A. C. (2019). Trauma, discrimination, and psychological distress across Vietnamese refugees and immigrants: A life course perspective. Community Mental Health Journal,55(3), 385–393.

Kim-Mozeleski, J. E., Tsoh, J. Y., Gildengorin, G., Cao, L. H., Ho, T., Kohli, S., et al. (2018). Preferences for depression help-seeking among vietnamese American adults. Community Mental Health Journal,54(6), 748–756.

Kinzie, J. D. (1985). Overview of clinical issues in the treatment of Southeast Asian refugees (pp. 113–135). Southeast Asian Mental Health: Treatment, Prevention, Services, Training, and Research.

Kumin, J. (2008). Orderly departure from Vietnam: Cold war anomaly or humanitarian innovation? Refugee Survey Quarterly,27(1), 104–117.

Laqua, C., Hahn, E., Böge, K., Martensen, L. K., Nguyen, T. D., Schomerus, G., et al. (2018). Public attitude towards restrictions on persons with mental illness in greater Hanoi area, Vietnam. International Journal of Social Psychiatry,64(4), 335–343.

Leahy, C., Winterford, K., Nghiem, T., Kelleher, J., Leong, L., & Willetts, J. (2017). Transforming gender relations through water, sanitation, and hygiene programming and monitoring in Vietnam. Gender & Development,25(2), 283–301.

Lee, S., Juon, H.-S., Martinez, G., Hsu, C. E., Robinson, E. S., Bawa, J., et al. (2009). Model minority at risk: Expressed needs of mental health by Asian American young adults. Journal of Community Health,34(2), 144.

Leong, F. T., Kim, H. H., & Gupta, A. (2011). Attitudes toward professional counseling among Asian-American college students: Acculturation, conceptions of mental illness, and loss of face. Asian American Journal of Psychology,2(2), 140.

Leong, F. T., & Lau, A. S. (2001). Barriers to providing effective mental health services to Asian Americans. Mental Health Services Research,3(4), 201–214.

Leu, J., Walton, E., & Takeuchi, D. (2011). Contextualizing acculturation: Gender, family, and community reception influences on Asian immigrant mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology,48(3–4), 168–180.

Leung, P., Cheung, M., & Cheung, A. (2010). Vietnamese Americans and depression: A health and mental health concern. Social Work in Mental Health,8(6), 526–542.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology,27(1), 363–385.

Link, B. G., Phelan, J. C., Bresnahan, M., Stueve, A., & Pescosolido, B. A. (1999). Public conceptions of mental illness: Labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health,89(9), 1328–1333.

Link, B. G., Yang, L. H., Phelan, J. C., & Collins, P. Y. (2004). Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin,30(3), 511–541.

Logan, D. G. (2017). Tips for mental health providers working with Southeast Asian Immigrants/Refugees [English and Vietnamese versions]. Psychiatry Information in Brief,14(5), 1.

Masood, N., Okazaki, S., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2009). Gender, family, and community correlates of mental health in South Asian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology,15(3), 265.

Masuda, A., & Boone, M. S. (2011). Mental health stigma, self-concealment, and help-seeking attitudes among Asian American and European American college students with no help-seeking experience. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling,33(4), 266–279.

Montazer, S., & Wheaton, B. (2011). The impact of generation and country of origin on the mental health of children of immigrants. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,52(1), 23–42.

Ngo, D., Tran, T. V., Gibbons, J. L., & Oliver, J. M. (2000). Acculturation, premigration traumatic experiences, and depression among Vietnamese Americans. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment,3(3–4), 225–242.

Nguyen, A. (2003). Cultural and social attitudes towards mental illness in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Seattle University Research Journal, Spring,2, 27–31.

Nguyen, D., Parker, L., Doan, M., & Brennan, L. (2012a). 2012. Paper presented at the ANZMAC: Decision making dynamics within the Vietnamese family unit.

Nguyen, H. T., Yamada, A. M., & Dinh, T. Q. (2012b). Religious leaders’ assessment and attribution of the causes of mental illness: An in-depth exploration of Vietnamese American Buddhist leaders. Mental Health, Religion & Culture,15(5), 511–527.

Nguyen, Q., & Anderson, L. P. (2005). Vietnamese Americans' attitudes toward seeking mental health services: Relation to cultural variables. Journal of Community Psychology,33(2), 213–231.

Nguyen, T.-N. (2019). Mental Health Perceptions in a Vietnamese American College Student Population (Doctoral dissertation)

O'Mahony, J. M., & Donnelly, T. T. (2007). The influence of culture on immigrant women's mental health care experiences from the perspectives of health care providers. Issues in Mental Health Nursing,28(5), 453–471.

Parcesepe, A. M., & Cabassa, L. J. (2013). Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: A systematic literature review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research,40(5), 384–399.

Park, M., Chesla, C. A., Rehm, R. S., & Chun, K. M. (2011). Working with culture: Culturally appropriate mental health care for Asian Americans. Journal of Advanced Nursing,67(11), 2373–2382.

Pedersen, E. R., & Paves, A. P. (2014). Comparing perceived public stigma and personal stigma of mental health treatment seeking in a young adult sample. Psychiatry Research,219(1), 143–150.

Pescosolido, B. A., Fettes, D. L., Martin, J. K., Monahan, J., & McLeod, J. D. (2007). Perceived dangerousness of children with mental health problems and support for coerced treatment. Psychiatric Services,58(5), 619–625.

QSR International Pty Ltd. (2015). NVivo qualitative data analysis software, Version 11.

Sadavoy, J., Meier, R., & Ong, A. Y. (2004). Barriers to access to mental health services for ethnic seniors: The Toronto study. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry,49(3), 192–199.

Shannon, P. J., Wieling, E., Simmelink-McCleary, J., & Becher, E. (2015). Beyond stigma: Barriers to discussing mental health in refugee populations. Journal of Loss and Trauma,20(3), 281–296.

Sirey, J. A., Bruce, M. L., Alexopoulos, G. S., Perlick, D. A., Friedman, S. J., & Meyers, B. S. (2001). Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatric Services,52(12), 1615–1620.

Sobowale, K., Nguyen, M., Weiss, B., Van, T. H., & Trung, L. (2016). Acceptability of internet interventions for youth mental health in Vietnam. Global Mental Health, 3

Spencer, M. S., Chen, J., Gee, G. C., Fabian, C. G., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2010). Discrimination and mental health-related service use in a national study of Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health,100(12), 2410–2417. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.176321.

Sue, S., Cheng, J. K. Y., Saad, C. S., & Chu, J. P. (2012). Asian American mental health: A call to action. American Psychologist,67(7), 532.

Ta, T. M. T., Böge, K., Cao, T. D., Schomerus, G., Nguyen, T. D., Dettling, M., et al. (2018). Public attitudes towards psychiatrists in the metropolitan area of Hanoi, Vietnam. Asian Journal of Psychiatry,32, 44–49.

Ta, V. M., Holck, P., & Gee, G. C. (2010). Generational status and family cohesion effects on the receipt of mental health services among Asian Americans: Findings from the national Latino and Asian American study. American Journal of Public Health,100(1), 115–121.

Umemoto, D. (2004). Asian American mental health help seeking: An empirical test of several explanatory frameworks (Doctoral dissertation, ProQuest Information & Learning)

U.S. Census Bureau. (2012). The Asian population: 2010. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf

Vu, L., & VanLandingham, M. J. (2012). Physical and mental health consequences of Katrina on Vietnamese immigrants in New Orleans: A pre-and post-disaster assessment. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health,14(3), 386–394.

Wong, Y. J., Kim, S.-H., & Tran, K. K. (2010). Asian Americans’ adherence to Asian values, attributions about depression, and coping strategies. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology,16(1), 1.

Wynaden, D., Chapman, R., Orb, A., McGowan, S., Zeeman, Z., & Yeak, S. (2005). Factors that influence Asian communities' access to mental health care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing,14(2), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00364.x.

Yeh, M., Hough, R. L., McCabe, K., Lau, A., & Garland, A. (2004). Parental beliefs about the causes of child problems: Exploring racial/ethnic patterns. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry,43(5), 605–612.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR001417 with a sub-contract to Tulane University. The authors would like to express their gratitude to Mily Nguyen and the staff at the New Orleans East Community Health Center for their assistance in recruitment and data collection. The authors thank Thuan Vuong and Chali Temple for their work in the transcription and translation of the interviews.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Focus Group Interview Guide

Introduction: Thank you for taking the time to participate in this focus group. I am going to be asking you some questions about thoughts, beliefs, and values related to mental health, mental health treatment, substance use, and substance use treatment. You do not need to talk about your own experiences with mental health or substance use. Instead, we are asking about how you perceive the Vietnamese community in general to perceive these things. You will notice you are in a group with people who are close to your own age and immigration background (came to the US young, came to the US older, or were born in the US). We are especially interested in learning about the variety within the Vietnamese community as it relates to age and immigration experience. When answering these questions you may agree with some things that other people say or you may disagree or have a different experience. This is OK. We want to make sure we are hearing everyone’s opinions and there are no “right” or “wrong” answers to these questions. We just ask that people speak respectfully when they disagree and that people speak honestly. We also ask that you keep these conversations private and not repeat what others say out in the community.

-

1.

How do you define mental health problems?

-

a.

What kinds of problems are considered mental health problems?

-

b.

What kinds of mental health problems do you see most often in your community?

-

c.

How serious do you think mental illness is in your community?

-

a.

-

2.

How do you define substance use problems?

-

a.

What kinds of problems are considered substance use problems?

-

b.

What kinds of substance use problems do you see most often in your community?

-

c.

How serious do you think substance abuse problems are in your community?

-

a.

-

3.

Do you think there are any connections between mental illness and substance abuse? If so, how?

-

a.

Probe about causes, symptoms and how the problems are managed or treated.

-

a.

-

4.

How does your community typically respond to someone with mental health or substance use problems?

-

a.

How do friends, family, and the community typically respond to people with these problems?

-

b.

What are some community beliefs about people with mental health or substance use problems?

-

a.

-

5.

What kinds of medical, spiritual, or professional treatment is available to your community for these problems?

-

a.

How likely are people to seek out this treatment?

-

a.

-

6.

Do people in your community differentiate between “Western” treatment and “traditional Vietnamese” treatment for these types of problems?

-

a.

What are the differences, if any?

-

b.

Which type of treatment are people in your community more likely to seek out?

-

a.

-

7.

Why do you think some people will not seek treatment for these problems?

-

8.

What are the things that might encourage someone to seek help for substance use or mental health problems?

-

9.

Hypothetically, if it were you, how would you like medical, spiritual, or professional personnel to treat substance use or mental health problems?

-

a.

What kinds of treatment or help would you like to have?

-

b.

How would you like your doctors to ask about mental health or substance use problems?

-

a.

-

10.

What are some of the things (family, friends, education, media, religion, etc.) that influence your beliefs and values about substance use and mental illness?

-

11.

What do you see as your community’s strengths in solving problems related to mental illness and substance abuse?

-

12.

Is there anything else you want to tell me about substance use and mental health problems in your community?

Appendix 2: Key Informant Interview Guide

Thank you for taking the time to participate in this interview. I am going to be asking you some questions about thoughts, beliefs, and values related to mental health, mental health treatment, substance use, and substance use treatment. I will also be asking about how you think these thoughts, beliefs, and values impact peoples’ willingness to seek treatment for these types of problems in the Vietnamese community. I am especially interested in your response to these questions as a person who provides care to the Vietnamese community. Your role provides critical insight.

-

1.

How do you define mental health problems?

-

a.

What kinds of problems are considered mental health problems?

-

b.

What kinds of mental health problems do you see most often in your community?

-

c.

How serious do you think mental illness is in your community?

-

a.

-

2.

How do you define substance use problems?

-

a.

What kinds of problems are considered substance use problems?

-

b.

What kinds of substance use problems do you see most often in your community?

-

c.

How serious do you think substance abuse is in your community?

-

a.

-

3.

Do you think there are any connections between mental illness and substance abuse? If so, how?

-

a.

Probe about causes, symptoms and how the problems are managed or treated.

-

a.

-

4.

What thoughts, beliefs, and values are present in the people you serve about mental illness and substance use?

-

a.

What factors (family, community, education, religion, etc.) influence these thoughts, beliefs, and values?

-

a.

-

5.

In what ways do the thoughts, values, and beliefs discussed above influence willingness to seek treatment for mental health or substance use problems?

-

6.

What are some things that would make it easier to provide or refer to treatment for behavioral health problems to the people you serve?

-

a.

What kinds of support would you like to have to provide or refer to treatment?

-

a.

-

7.

Can you please describe some specific experiences you have had treating or referring for substance use or mental health problems and what those experiences were like?

-

8.

What do you see as the community’s strengths in solving problems related to mental illness and substance abuse?

-

9.

Is there anything else you want to tell me about responding to behavioral health issues in your community?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Do, M., McCleary, J., Nguyen, D. et al. Mental Illness Public Stigma and Generational Differences Among Vietnamese Americans. Community Ment Health J 56, 839–853 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00545-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00545-y