Abstract

This article reports the findings from a study that examined the role of economic stress and coping resources in predicting hwabyung symptoms among Koreans in the United States. The literal meaning of hwabyung is “fire illness” or “anger illness.” Koreans believe that chronic stress can cause the onset of hwabyung, manifested mainly through somatic symptoms. Data collected from an anonymous survey of 242 voluntary participants were analyzed using hierarchical multiple regression (R2). The findings demonstrated the important role that social support and sense of self-esteem play in explaining hwabyung symptoms. Also, the graduate education attained in the United States appears to play positive role in reducing the hwabyung symptoms, while being a woman can increase their vulnerability to this indigenous psychiatric illness to Korean people. Based on the findings, the implications for practice and suggestions for future study are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The primary goal of this study is to examine economic stress and coping resources as predictors of hwabyung symptoms among Koreans in the United States. Hwabyung is an indigenous psychiatric illness commonly found in Korean culture. The literal meaning of hwabyung is “fire illness” or “anger illness” as the Korean word, hwa, simultaneously connotes both fire and anger. Koreans believe that chronic stress can cause the onset of hwabyung, manifested mainly through somatic symptoms (Lee 2015).

Almost 12% of Korean immigrants suffer from hwabyung according to the study conducted by Lin and his colleagues (1992) in Los Angeles area, California. This is the only community based study that reports the prevalence of hwabyung among Koreans in the United States. Their findings demonstrate the higher prevalence of hwabyung than we find in Korea, which is estimated to be 4.1% among its general population (Min 2009). The difficulties involved in immigration might have increased the vulnerability of Korean immigrants to hwabyung.

Many Korean immigrants enjoyed a higher socioeconomic status while living in Korea that often diminished after their immigration to the United States (Duleep 2015). Their educational and professional credentials attained in Korea are often not recognized in the United States. Because of their limited English skills, many Korean immigrants experience disadvantages in the labor market and, as a consequence, suffer from day-to-day economic hardship. Thus, heightened level of hwabyung symptoms among Korean immigrants might be caused by various challenges associated with their immigration experiences including economic stress. Indeed, empirical evidence highlights the link between the economic hardship and the increased levels of psychological distress (Pulgar et al. 2016).

Korean immigrants try to deal with the difficulties associated with their immigration experiences through calling on coping resources. The sense of self-esteem is counted as a psychological coping resource (Rosenberg 1979), whereas the tangible or emotional assistance provided by family, friends or neighbors are considered to be social support (Thoits 1986). The previous findings demonstrated the positive role of these two coping resources in lessening psychological distress such as depressive symptoms (Du et al. 2016).

However, less is known about the role of economic stress and coping resources in predicting hwabyung symptoms among Koreans in the United States. The following question guided the current study: What is the relative importance of economic stress, coping resources, and the differences in individual characteristics on hwabyung symptoms? It was hypothesized that economic stress, coping resources, and the differences in individual characteristics of Korean immigrants affect the changes in hwabyung symptoms. Based on the findings, implications for practice and future study are discussed.

Psychological Ramifications of Immigration

Acculturation and Psychological Distress

Immigration is often portrayed as an “uprooting” or “re-rooting” experience due to the difficulties involved in the acculturation process (Furnham and Bochner 1986). The term acculturation refers to various changes in the life styles or behaviors that take place through reciprocal interactions between the immigrants and their new environment. The potential negative psychological effect of immigration is called acculturative stress (Berry 2006).

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) define the psychological stress as the relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised as a threat to the well-being of that person. When the demand to change exceeds the ability of individual immigrants, it can elevate their vulnerability to psychological distress such as depressive symptoms (Berry 2006). Previous findings reported the notably higher levels of depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants in the United States. The Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression (CES-D) score among Koreans in the United States ranges from 12.6 to 17.6 (Kim et al. 2013, 2016, 2010; Koh 1998; Shin et al. 2007). In addition to the personal characteristics such as gender, age, level of education, marital status, or income, the depressive symptoms of Korean immigrants are associated with English proficiency, length of stay in the United States, and affiliations with their ethnic community (Bernstein et al. 2011; Shin et al. 2011).

Culture and Illness

It is important to recognize cultural variations in psychiatric symptoms among different ethnic groups living in the United States. Kleinman (1988), a medical anthropologist, makes the distinction between illness and disease. He defines illness as the client’s “perception, experience, expression, and pattern of coping with symptoms,” in contrast to disease that can be defined as “the way practitioners recast illness in terms of their theoretical model of pathology” (p. 7). Thus, Korean immigrants’ suffering from psychiatric distress has to be understood in terms of their culture, since it shapes not only their experience with its symptoms, but also the ways they try to cope with them. Growing numbers of empirical evidence questions that the depressive symptoms may not have cultural equivalence for Koreans (Kim et al. 2013; Sin et al. 2011). As an indigenous psychiatric illness specific to Koreans, hwabyung can be a culturally appropriate measure to assess the psychological ramifications of their immigration experiences.

Hwabyung

Hwabyung is often called anger syndrome in English. Another Korean word wol-hwabyung, meaning suffocating anger illness is also interchangeably used with hwabyung. One of the astonishing features of this psychiatric distress indigenous to Korean culture is self-diagnosis (Min 2009). People with hwabyung believe that their psychological and interpersonal distresses cause the onset of their symptoms.

According to traditional Korean medicine, hwabyung occurs from a disturbance of the balance between yin (negative elements) and yang (positive elements) caused by chronic psychological distress. The accumulated neurotic fire (hwa/anger) in the heart, liver, stomach, head, and/or chest can provoke hwabyung symptoms (Khim and Lee 2003; Min 2009; Lee 2013). Western medicine, in comparison, explains hwabyung caused by a prolonged suppression of negative emotion projected on the body (Suh 2013). Hwabyung occurs when people no longer suppress their frustration, resentment, or anger, which was accumulated over a long period of time (Min 2008, 2009). Although each medical approach tries to explain hwabyung according to its own theoretical perspective, both the traditional Korean medicine and Western psychiatry see accumulated stress as the major source of hwabyung.

Symptoms Related to Hwabyung

Koreans tend to manifest psychological distress through somatic symptoms (Min 2009; Suh 2013). The primary symptoms of hwabyung include a stuffy feeling in the chest, palpitations, heaviness of the head, insomnia, localized or generalized pain, dry mouth, indigestion, anorexia, dizziness, nausea, constipation, blurred vision, cold and hot sensations in the body, face, eyes, or mouth, epigastric mass, frequent urination, and cold sweats. Other hwabyung symptoms include feelings of mortification, anger, pessimism, anxiety, nervousness, regret, loneliness, fear, guilt, shame, being short tempered, loss of interest, resentment, tearfulness, sense of suffocation, grief, exhaustion, paranoia, suicidal ideation, and feelings of helplessness and hopelessness.

Risk Factors Associated with Hwabyung

Existing studies constantly indicate that hwabyung especially affects middle-aged women with less education and fewer economic resources (Suh 2013). Life adversities of Korean women, including issues related to conjugal relationships, child rearing, and unfair criticism from their in-laws are known to be contributing factors to hwabyung. In the case of Korean men, their inability to fulfill a role of the family provider may cause their suffering from hwabyung. For instance, men usually comprise less than 10% of total patients at hwabyung clinics in Korea. After the serious financial crisis of 1997 that severely affected the Korean economy, this number increased to 30% of total patients (Kim 2006).

In the United States, both Korean men and women are at greater risk of being afflicted with hwabyung due to difficulties associated with their immigration experiences. Confronted by racial and language barriers, Korean immigrants often experience limited social mobility and opportunities for professional developments. Unfortunately, the jobs available to them are labor intensive temporary low paying positions at restaurants, drycleaners, and groceries in their ethnic communities. When their accumulated suffering is no longer bearable, it may manifest through heightened level of hwabyung symptoms.

Coping Resources

Coping resources are personality characteristics and social support that people have available for dealing with stressful life events (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). There are two types of coping resources: psychological and social resources. A sense of self-esteem refers to an individual’s appreciation of their own merits and sense of self-worth (Rosenberg 1979). It is a formidable psychological resource for individuals dealing with stressful life events. Individuals with higher self-esteem do not necessarily consider themselves better than others, but they think well of themselves.

As a social coping resource, social support refers to assistance provided by family, friends, colleagues, and members of the community (Pearlin and Schooler 1978). An underpinning assumption of social support is that individuals can attain a sense of comfort through their relatedness to others (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Empirical findings demonstrate the positive effect of both the psychological and social coping resources on lessening the psychological symptoms felt by Korean immigrants (Kim et al. 2015; Shin et al. 2007).

Significance of the Study

The significant of this study is to extend the current cross-cultural psychiatric knowledge. Using hwabyung, the current study examined the mental health impacts of immigration experiences among Koreans in a culturally appropriate way. Informed by the findings of this study, mental health clinicians can provide culturally sensitive services that can enhance resilience of Korean immigrants to transform the difficulties involved in their immigration experiences into opportunities for a better life.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This manuscript was prepared based on the study that was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Simmons College, Boston, Massachusetts in the United States. In addition, the author of this manuscript holds no conflicts of interest and is responsible for the manuscript.

Method

Data Collection Procedure

This was a cross-sectional study that employed a non-probability sample of 242 adult Korean immigrants residing in a metropolitan area located on the East Coast of the United States. In the current study, Korean immigrants are defined as those who consider the United States their permanent domicile regardless of their current immigration status. The Korean immigrants participating in this study were first-generation adult men and women, who moved to the United States after the age of 18. Additionally, participants had to read and write Korean in order to complete the Korean language questionnaire.

Potential participants were recruited at educational, religious, and other social institutions located in Korean immigrant communities. They are appropriate sites for participant recruitment since Koreans are often affiliated with at least a couple of ethnic organizations (Min 1992). The data collection procedure involved a self-administered anonymous survey. By ensuring the participants’ anonymity, this study hoped to elicit direct and honest responses from the participants. The approximate time needed to complete the questionnaire was 30 min. A $10 gift certificate was provided to the participants as a token of appreciation.

A total of 285 questionnaire packets were distributed to potential participants. Among those, 251 questionnaires (88.07%) were returned. Of those, 242 questionnaires (96.41%) were used for data analysis. Nine questionnaires were excluded because they contained minimal or no information.

Participants Characteristics

Of the 242 participants, slightly more people were women (f = 143, 59.1%) than men (f = 99; 40.9%), with a median age of 41 years. The median length of residence in the United States was 10 years. Also, most participants immigrated to the United States for their own education (f = 74, 30.6%), marriage (f = 38, 15.7%) and education for children (f = 31, 12.8%). The majority lived with a spouse or partner (f = 212, 87.6%) and almost half of the total participants own homes (f = 118; 48.8%).

Most participants attained above a high school education while living in Korea (f = 225, 92.8%). Of the 115 (47.5%) participants who attained formal education in the United States, 78 (67.8%) had received a graduate school diploma. Concerning their English proficiency, only 36 (14.9%) participants reported having no difficulties in using English. Others reported that their confidence in using English was either moderate (f = 110, 45.5%) or they had difficulties in using it (f = 94, 38.8%). The largest number of participants described themselves as professionals (f = 74, 30.6%) and approximately one-third of women participants were unemployed (f = 47, 19.4%). The individual Korean immigrant characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Standardized Instruments

The standardized data collection instruments employed in this study were either originally devised in Korean or translated from English. These standardized Korean-language instruments have adequate psychometric properties and have been widely used in many studies conducted both in Korea and the United States. To ensure the validity and reliability of the instruments prepared for this study, and make it easier for participants to answer questions, a reverse translation into Korean was conducted. In addition, a pilot test was conducted to detect potential problems related to data collection instruments and concerns that respondents may encounter while answering the questions.

Hwabyung Scale (HS)

The original HS was devised in Korean and consists of two sub-scales that assess personality and symptoms related to hwabyung (Kwon et al. 2008). In the current study, the 15-item HB symptoms sub-scale is used to assess the psychological ramifications of the immigration experiences among Koreans in the United States. The HB symptoms sub-scale measures emotional and somatic symptoms including “I feel deep anger at times” and “I have a burning sensation in my chest.” The respondents are asked to answer each item on a 5-point scale ranging from “0 = strongly disagree” to “4 = strongly agree.” The possible overall score ranged from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate increased levels of hwabyung symptoms. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the symptom dimension of the HS was 0.92.

The Economic Stress Scale (ESS)

The ESS is a Korean language version of the Family Economic Pressure Scale. Oh (2001) devised the Economic Stress Scale by modifying the second dimension of the Family Economic Pressure Scale (Conger et al. 1992). The ESS was designed to assess the financial ability of individuals to meet the eight areas of daily living expenses including housing, clothing, food, medical needs, utilities, transportation, recreational activities, and education using a four-point scale ranging from, “very insufficient” to “very sufficient.” In this study, an item that asks about the financial ability of the respondents to meet their own educational expenses was added since many Koreans immigrate to the United States to achieve better educational opportunities for themselves. An item that did not apply to the subject was assigned the score of 0. The possible overall score ranged from 0 to 36. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the ESS based on the sample of this study was 0.85.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE)

The 10-item RSE Scale was employed to assess individual Korean immigrants’ sense of self-esteem based on their self-acceptance and self-worth statements (Rosenberg 1979). Each item was answered on a 4-point scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “4 = strongly agree.” The possible overall score ranged from 10 to 40. Higher overall scores indicate a greater sense of self-esteem. The RSE Scale has five negatively worded items that reflect an individual’s negative sense of self. These negatively worded items were reverse scored in order to have higher scores represent higher self-esteem. The RSE Scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity and has been widely used across different ethnic groups. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the Korean version of the RSE Scale based on the sample of this study was 0.86.

The Social Support Scale (SSS)

To assess perceived social support, this study employed the indirectly perceived social support section of the SSS devised in Korea by Park in 1985 (as cited in Choi 2006). The indirectly perceived social support scale has been widely used in many studies conducted in Korea. This 25-item scale covers four different areas of support including emotional (7 items), informational (6 items), material (6 items), and evaluative support (6 items). The following are some items listed in the indirectly perceived social support sub-scale: “The people around me always take good care of me with love,” and “The people around me always offer me help as best as they can.” Respondents are asked to answer each item on a 5-point scale (“1 = none of them are like that” to “5 = all of them are like that”). The possible overall score ranged from 25 to 125. The higher scores indicate receiving higher levels of social support. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the indirectly perceived social support section of the SSS based on the sample of this study was 0.97.

Findings

Preliminary Analyses

First, descriptive analyses were performed to assess means, standard deviations, and range of the hwabyung symptoms, economic stress, self-esteem, and social support. The result of the data analysis shows that the mean score of hwabyung symptoms was 12.16 (SD = 8.74) with a range from 0 to 47 (possible overall score: 0–60). This mean score was almost six points lower than the findings from the previous study conducted in Korea, which was 18.38 (SD = 8.75) (Kwon et al. 2008).

In the current study, the economic stress scale was used to assess the financial ability of Korean immigrants to meet their daily living expenses. The possible overall score ranged from 0 to 36. Higher scores indicate a better ability to meet daily living expenses. In the current study, the mean score for ESS was 21.2 (SD = 6.04), which indicates above a mid-level to meet daily living expenses.

In the case of coping resources, the mean score of social support was 90.5 (SD = 14.92). When considering the possible overall score ranged from 25 to 125, the current mean score indicates above a mid-level of social support score. Additionally, the mean score of sense of self-esteem was 31.41 (SD = 4.78). The possible overall score ranged from 10 to 40. Similar to social support, the current findings indicate above a mid-level for sense of self-esteem. Table 2 summarizes the findings of the preliminary analyses.

Multivariate Analysis

A hierarchical multiple regression (\({R}^{2}\)) analysis was performed utilizing three blocks to examine the impacts of economic stress and coping recourses on hwabyung symptoms. When selecting variables for the data analyses, findings from prior studies on hwabyung and depressive symptoms were considered. Also, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) were performed to identify variables included in the data analysis.

In the first block, economic stress of Korean immigrants was entered to assess its importance separately from coping resources and individual characteristics. In the second block, sense of self-esteem and social support were added. Finally, in the third block, individual characteristics of participants were added along with a variable relevant to acculturation.

In the current study, acculturation is measured by English proficiency of participants and their lengths of residence in the United States. Approximately 77% of Korean immigrants use English as their primary language at work (Kim and Wolpin 2008). English proficiency may affect their overall functioning in other domains of everyday life including employment (Zhen 2013). Also, many Korean immigrants find opportunities for better integration as their lengths of residency extended. Their interactions with the host society become vitalized by acquiring citizenship and improving their English proficiency.

In regard to education, the previous studies demonstrated that Korean immigrants who attained higher education in the United States showed significantly increased levels of acculturation to the host culture (Oh et al. 2002). Approximately 52% of Korean immigrants aged 25 years old and over have attained a Bachelor’s degree or higher in comparison with 30% of the United States-born population (Zong and Batalova 2014). Despite their higher academic credentials attained in Korea, many Korean immigrants have limited opportunities for professional development. Such disadvantages appear to have negative impacts on their mental health (Arau´jo & Borrell 2006). Thus, in the current study, the psychological ramifications of immigration were assessed based on the graduate school education attained in the United States.

The literature on Korean immigrant often notes the difficulties associated with collecting their income (Kwon 2003). In order to increase participants’ response, the data associated with the annual family income were collected by categorizing them into the following way: (1) > $50,000; (2) ≥ $50,000 but > $75,000; (3) ≥ $75,000 but > $100,000; (4) ≥ $100,000 but > $125,000; (5) ≥ $125,000 but > $150,000; (6) ≥ $150,000.

In addition, the following variables were dichotomized for data analysis.

-

Demographic information: gender (0 = men, 1 = women), living with a spouse or partner (0 = no, 1 = yes).

-

Acculturation: English proficiency (0 = difficult, 1 = moderate or okay)

-

Education: acquiring graduate degree in the United States (0 = not checked, 1 = checked).

The Impact of Economic Stress, Coping Resources, and Individual Characteristics on Hwabyung

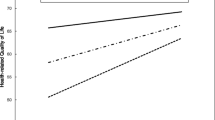

The hierarchical multiple regression (\({R}^{2}\)) analyses demonstrated that economic stress, sense of self-esteem, social support, and individual characteristics explained 37% of the variance in hwabyung symptoms [F (10, 212) = 12.44; p < .001]. The incremental change for each of the three blocks was statistically significant. When assessed separately from other variables, economic stress alone explained 2.25% of the variance in hwabyung symptoms. However, when sense of self-esteem and social support were added, the role of economic stress was no longer significant in predicting hwabyung symptoms. Contrarily, the impacts of two coping resources were found to be significant on the changes in hwabyung symptoms. For instance, social support explained whopping 14.44% of the variance in hwabyung symptoms, followed by sense of self-esteem which explained 10.24% of the variance in hwabyung symptoms.

Of all the factors included in the third block, social support (18.49%) and sense of self-esteem (7.29%) remained to be the strongest predictors in explaining hwabyung symptoms. In addition, having a graduate school education in the United States (2.56%), and being a woman (1.96%) were found to be significantly related to the changes in the hwabyung symptoms. The current findings explain the critical role that coping resources play in explaining hwabyung symptoms felt by Korean immigrants in the United States. Also highlighted is the important role that higher education attained in the United States and gender play in predicting mental health status of Korean immigrants. Table 3 presents the findings of a hierarchical multiple regression (\({R}^{2}\)) analysis.

Discussions

The findings of the current study confirmed the significant role that coping resources play in lessening the level of hwabyung symptoms. Although the graduate school education obtained in the United States might have positive impacts on the psychological well-being of Korean immigrants in the United States, being a woman can increase their vulnerability to hwabyung symptoms.

Practice Implications

The level of hwabyung symptoms among Korean immigrants participated in the current study is drastically lower (M = 12.16; SD = 8.75) than that of the previous study conducted in Korea (M = 18.38, SD = 11.41). This big discrepancy might be stemmed from the characteristics of samples. Unlike the previous study which was conducted in a medical setting on patients experiencing psychopathology, the current study collected the data at educational, religious, and other social institutions located Korean immigrant communities. The strong sense of connectedness among the participants in the present study might have a positive effect on their psychological well-being. A relatively lower level of hwabyung symptoms might also stem from their income, educational backgrounds, and lengths of residence. For instance, approximately 31.4% of participants (f = 74) reported that their annual family income exceeded 100,000 USD. Moreover, approximately, half of the participants (f = 115, 47.5%) received formal education in the United States and, of those, 78 participants reported that they had a graduate school diploma. Also, the median length of residence in the United States was 10 years. Along with their higher education, the extended length of residence in the United States enable the participants in the current study readdress the difficulties associated with their acculturation. They were able to improve economic conditions, English proficiency, and social interactions both within as well as outside of their own ethnic communities (Kim 2009). These experiences might positively influence their psychological well-being.

In the current study, economic stress plays a significant role in predicting the level of hwabyung symptoms when assessed separately from other variables. However, its association decreased when social support and sense of self-esteem were included in the analysis. This finding implies the important roles that each of two coping resources plays in predicting hwabyung symptoms. For instance, economic hardship causes various challenges in life including food insecurity, poor health, deteriorated housing conditions, and lack of health insurance coverage. Such life adversities can diminish sense of self-esteem among Korean immigrants. Similarly, economic hardship could erode perceived social support, which resulted in increased level of psychological distress. Previous findings recognized economic hardship, social support, and sense of self-esteem as key variables in explaining psychological well-being of diverse individuals (Crowe et al. 2016; Rhee 2015).

Korean immigrants find the source of social support from their own ethnic communities such as Christian churches and Buddhist temples. Through their affiliation with these religious institutions, Korean immigrants navigate the meanings of their uprooting experiences and their existential alienation in the new environment (Hurh and Kim 1990). Based on their shared understanding of the immigration experience and its challenges, the members of these institutions become an extended family. Moreover, these religious institutions are inclusive and accessible regardless of one’s sex, age, or socioeconomic status (Min 1992). They function as a “reception center” for new immigrants by providing needed assistance for their resettlement, including information and counseling on employment, business, and healthcare (Kim and Grant 1997). They also play a role as an educational center where the immigrants’ children can learn the Korean language, history, and culture. The ethnic solidarity and affinity among Korean immigrants can create a form social support that can enhance subjective well-being of individual Korean immigrants and lessen the level of hwabyung symptoms.

The findings of the current study suggest the positive effects of a graduate school education attained in the United States on reducing hwabyung symptoms among Korean immigrants. While examining the socio-cultural adaptation patterns of Korean immigrants, Hurh and Kim (1984) found that those who attained higher education in the United States tend to show better acculturation levels. Regardless of their length of residency, these Korean immigrants show a higher degree of social integration. Thus, the graduate education obtained in the United States can promote not only economic stability of Korean immigrants but also their social support system. According to Oh et al. (2002), those Korean immigrants who had received their higher education in the United States showed, as might be expected, an increased level of English proficiency. A number of other studies report that the education received in the United States and English proficiency were two important determinants of the earning power of immigrants (Melink and Toponarski 2007). The educational credentials acquired in the United States can facilitate the social integration of Korean immigrants and expand their social support systems that might otherwise be limited to within their family and their ethnic community. These positive experiences can enhance not only the sense of self-esteem among Korean immigrants but also their ability to cope with hwabyung symptoms.

When immigrating to the United States, the majority of Korean immigrant women participate in the labor market to meet the economic needs of their families. Through their role as a family provider, Korean women may find the improved economic opportunity. However, similar to their male counterparts, these women encounter challenges in labor market. Korean immigrant women frequently find service-oriented low paying temporary jobs such as helpers at restaurants and grocery stores located in their ethnic communities. Many of them become unpaid workers if their families own businesses (Park 2008). At the same time, Korean immigrant women are expected to carry out their traditional role as housewives by taking full responsibilities for housekeeping and child rearing (Lee et al. 2016). They face increased level of marital conflicts when their husbands prefer patriarchal traditions. Moreover, Korean women suffer from intergenerational conflicts due to language and cultural gaps between them and their children. Therefore, the vulnerability of Korean immigrant women to hwabyung symptoms is an expected outcome.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Study

When considering the findings of the current study, several limitations should be acknowledged. This study employed a cross-sectional survey method. It did not measure the impact of economic stress and coping resource on hwabyung symptoms over time nor did the data collected through this design allow for assessing cause and effect.

In addition, this study employed a self-administered survey that had an inherent limitation such as the possibility of under- or over-reporting due to response bias. The sampling method and geographical specificity of the data collection sites are other areas of concern. Because of the convenience sampling method and relatively small sample size, the generalization of the findings is open to question.

By employing a more rigorous data collection method including a larger number of participants from different regions of the United States, future studies should increase variability of the sample, and consequently the generalizability of the findings. In addition, duplicating the current study to a larger sample is necessary in order to acquire better understanding of the role of economic stress and coping resources in predicting the changes in the hwabyung symptoms.

The findings of the current study demonstrated the significant role of social support and self-esteem in explaining hwabyung symptoms among Koreans in the United States. However, factors affecting changes in the level of social support and self-esteem were not identified. In the future, studies should identify the sources of social support and self-esteem. Do Korean immigrants receive social support from their family members, relatives, the Korean community, or from outside of the Korean community? What are the factors that can strengthen the level of self-esteem of Korean immigrants?

Another area to explore deeper is the link between coping method and the changes in the level of hwabyung symptoms. The term coping method refers to what people think or do in order to deal with difficult life situations (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). The emotion-focused coping method aims at regulating emotional reactions to stressful events through avoiding, minimizing, distancing, and even altering the meaning of the stressful situation. In contrast, the problem-focused coping method refers to the direct management of the stressful situation. This includes learning new skills and behaviors to deal with stress provoking events. These two coping strategies can occur independently and concurrently. They also can mutually facilitate or interfere with each other throughout the coping process.

The problem-focused coping strategy appears to be preferred by those Korean immigrants who can utilize social resources, while the emotion-focused coping strategy is often employed by those who lack support from their ethnic community (Noh and Kaspar 2003). One can assume then, that the effectiveness of the coping strategy can vary depending on the available resources. Korean immigrants with fewer resources may have to rely on the emotion-focused coping strategy, while the problem-focused coping strategy is preferred by those who have better social resources. By exploring the impacts of these two coping method on hwabyung symptoms, we can increase current cross-cultural psychiatric knowledge.

Of the issues most frequently debated in the study of hwabyung is whether it is a culturally patterned psychiatric suffering arising from major depression since these two morbidities share similar symptom characteristics (Lin 1983; Lin et al. 1992; Park et al. 2001, 2002). However, other scholars see hwabyung as a culturally specific psychiatric illness among Korean people (Lee 2015; Min 2009; Min et al. 2009). For instance, hwabyung symptoms include distinctive cultural traits unique to Korean people such as Haan, a complex emotional state that involves mixed feelings of sorrow, endurance, and regret, along with feelings of hatred and revenge (Min 2009). More recently, Min (2008) proposed to construct a new diagnose called an anger disorder. Suppressed anger causes the psychological and somatic distress relevant to hwanyung and similar disorders found across different cultures. Thus, a new diagnostic category can be created by integrating clinical features of the anger related disorders. The debate about whether hwabyung is a Korean culture-bound syndrome, a form of mood disorder listed in the DSM, or needs to be categorized it as an anger disorder requires a further investigation. Such an effort will enhance not only our understanding of hwabyung but also the ability of clinicians to support those who suffer from its symptoms.

Conclusion

The findings of the current study confirm the important role that the social support and sense of self-esteem plays in predicting with hwabyung symptoms among Korean immigrants. Moreover, the findings demonstrate that graduate school education acquired in the United States can lessen the level of hwabyung symptoms. In contrast, being a woman is a risk factor that can increase their vulnerability to hwabyung symptoms.

Mental health providers working closely with Korean immigrant communities have to become familiar with specific features of hwabyung. In addition to self-diagnosis, hwabyung is known to be a chronic illness. People with hwabyung often seek out clinical intervention after 10 or longer years of suffering from its symptoms. Also, people suffer from hwabyung often diagnosed with two or more psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and somatization congruently with hwabyung (Min and Suh 2010).

In general, Korean immigrants often experience diminished social support network and self-esteem while settling in unfamiliar conditions of their new environment with limited English skills. For Korean immigrants, however, their ethnic communities becomes a wonderful source of their social support and enhanced self-esteem as it provides them both economic opportunities and a sense of ethnic solidarity.

The educational opportunities to advance their professional qualifications and English proficiency can promote social support and sense of self-esteem. Local colleges and universities are recognized as important assets that can effectively provide professional training in various forms including full-time, part-time, online education, as well as education in a workplace or classroom setting. More often than not, finding the time and the money to advance their skills can be challenging. Creating programs that are accessible, affordable and flexible enough to accommodate the needs of Korean immigrants is critical to advance their professional credentials and English proficiency. Such positive experiences can ensure not only economic stability of Korean immigrants but also their psychological well-being.

Without altering the patriarchal tradition, Korean immigrant women will continually endure multiple role obligations including wage earners, mothers, and wives. By recognizing their contributions to the well-being of the family, Korean immigrant women can enhance their sense of self. With their esteemed sense of self, Korean immigrants can challenge the patriarchal convention (Lee et al. 2016). For many Korean immigrants, family is a source of support where they can find love, security, and a sense of belonging. Indeed, the importance of family harmony in Korean culture is explained by a popular phrase ka-hwa-man-sa-sung. The literal meaning of this phrase is that a harmonious family is the origin of ten thousand successes. Indeed, as noted by previous studies, family support is found to be a significant factor in reducing psychological symptoms (Lee et al. 2004). Community mental health providers should consider creating programs for Korean immigrant couples and their children that can reinforce emotional closeness, communications skills, and harmonious interactions among them. Such efforts can promote the ability of Korean immigrant women in overcoming their vulnerability to hwabyung symptoms.

References

Araújo, B., & Borrell, L. N. (2006). Understanding the link between discrimination, life chances, and mental health outcomes among Latinos. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 28(2), 245–266.

Bernstein, K. S., Park, S. Y., Shin, J., Cho, S., & Park, Y. (2011). Acculturation, discrimination and depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants in New York City. Community Mental Health Journal, 47(1), 24–34.

Berry, J. W. (2006). Stress perspectives on acculturation. In D. L. Sam & J. W. Barry (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology, (pp. 43–57). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Choi, Y. K. (2006). The effects of social support on the women’s empowerment with family violence. Unpublished master’s dissertation, The Graduate School of University of Seoul, Seoul, South Korea.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., Simons, R. L., & Whitbeck, L. B. (1992). A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development, 63(3), 526–541.

Crowe, L., Butterworth, P., & Leach, L. (2016). Financial hardship, mastery and social support: Explaining poor mental health amongst the inadequately employed using data from the HILDA survey. SSM - Population Health, 2, 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2015.12.001.

Du, H., King, R. B., & Chu, S. K. W. (2016). Hope, social support, and depression among Hong Kong youth: Personal and relational self-esteem as mediators. Psychology, Health, and Medicine, 21(8), 926–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2015.1127397.

Duleep, H. O. (2015). The Adjustment of immigrants in the labor market. In K. J. Arrow & M. D. Intriligator (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of international migration (pp. 105–182). Oxford: Elsevier.

Furnham, A., & Bochner, S. (1986). Culture shock: Psychological reaction to unfamiliar environments. New York: Methuen.

Hur, W. M., & Kim, K. C. (1990). Religious participation of Korean immigrants in the United States. Journal of the Scientific Study of Religion, 29(1), 19–34.

Hurh, W. M., & Kim, K. C. (1984b). Adhesive sociocultural adaptation of Korean immigrants in the U.S.: An alternative strategy of minority adaptation. International Migration Review, 18(2), 188–216.

Khim, S. Y., & Lee, C. S. (2003). Exploring the nature of “Hwa-Byung” using pragmatics. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 33(1), 104–112.

Kim, B. J., Linton, K., Cho, S., & Ha, J.-H. (2016). The relationship between neuroticism, hopelessness, and depression in older Korean immigrants. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145520.

Kim, E. (2009). Multidimensional acculturation attitudes and depressive symptoms in Korean Americans. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30(2), 98–103.

Kim, E., Landis, A. M., & Cain, K. K. (2013). Response to CES-D: European American versus Korean American adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescents Psychiatric Nursing, 26(4), 254–261.

Kim, E., Seo, K., & Cain, J. C. (2010). Bi-dimensional acculturation and cultural response set in CES-D among Korean immigrants. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31(9), 576–583.

Kim, E., & Wolpin, S. (2008). The Korean American family: Adolescents versus parents acculturation to American culture. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 15(3), 108–116.

Kim, J., Kim, M., Han, A., & Chin, S. (2015). The importance of culturally meaningful activity for health benefits among older Korean immigrant living in the United States. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 10, 1–9.

Kim, M. J. (2006). The relation of stress, social support, and self-esteem to hwabyung of men. Unpublished master’s dissertation. Chung-Ang University, Seoul, South Korea.

Kim, Y., & Grant, D. (1997). Immigration patters, social support, and adaptation among Korean immigrant women and Korean American women. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 3(4), 235–245.

Kleinman, A. (1988). Rethinking psychiatry: From cultural category to personal experience. New York: Free Press.

Koh, K. B. (1998). Perceived stress, psychopathology, and family support in Korean immigrants and nonimmigrants. Yonsei Medical Journal, 39(3), 214–221.

Kwon, J. H., Kim, J. W., Park, D. G., Lee, M. S., Min, S. G., & Kwon, H. I. (2008). Development and validation of the hwabyung scale. The Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(1), 237–251.

Kwon, O. (2003). Buddhist and protestant Korean immigrants: Religious beliefs and socioeconomic aspects of life. New York: LFB Scholarly Publishing.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Lee, H., Moon, A., & Knight, B. G. (2004). Depression among elderly Korean immigrants: Exploring socio-cultural factors. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 13(4), 1–26.

Lee, J. (2013). Factors contributing to hwabyung symptoms among Korean immigrants. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 22(1), 17–39.

Lee, J. (2015). Hwabyung and depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants. Social Work in Mental Health, 13(2), 159–185.

Lee, J., Martin-Jearld, A., Robinson, K., & Price, S. (2016). Hwabyung experiences among Korean immigrant women in the United States. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 9(2), 325–349.

Lin, K. M. (1983). Hwabyung: A Korean culture bound syndrome? The American Journal of Psychiatry, 140(1), 105–107.

Lin, K. M., Lau, J. K. C., Yamamoto, J., Zheng, Y. P., Kim, H. S., Cho, K. H., et al. (1992). Hwabyung: A community study of Korean Americans. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180(6), 386–391.

Melink, M., & Toponarski, M. (2007). Language skill requirements in the labor market. Publication 613-1 MA: City of Boston; Boston Redevelopment Authority; Center for Urban and Regional Policy at North Eastern University.

Min, P. G. (1992). Structural and social functions of Korean immigrant churches in the United States. International Migration Review, 26(4), 1370–1394.

Min, S. (2008). Clinical correlates of Hwa-Byung and a proposal for a new anger disorder. Psychiatry Investigation, 5(3), 125–141.

Min, S. (2009). Hwabyung in Korea: Culture and dynamic analysis. World Cultural Psychiatry Research Review, 4(1), 12–21.

Min, S. K., & Suh, S. Y. (2010). The anger syndrome hwabyung and its comorbidity. Journal of Affective Disorders, 124(1/2), 211–214.

Noh, S., & Kaspar, V. (2003). Perceived discrimination and depression: Moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. American Journal of Public Health, 93(2), 232–238.

Oh, S. H. (2001). Factors that determine the adaptation of teenagers from low-income families. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Seoul National University, Seoul.

Oh, Y., Koeske, G. F., & Sales, E. (2002). Acculturation, stress, and depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants in the United States. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142(4), 511–526.

Park, K. J. (2008). “I can provide for my children”: Korean immigrant women are changing perspectives on work outside the home. Gender Issues, 25(1), 26–42.

Park, Y. C. (2004). Hwabyung: Symptoms and diagnosis. Psychiatry Investigation, 1(1), 25–28.

Park, Y. J., Kim, H. S., Kang, H. C., & Kim, J. W. (2001). A survey of hwabyung in middle-age Korean women. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 12(2), 115–122.

Park, Y. J., Kim, H. S., Schwartz-Barcott, D., & Kim, J. W. (2002). The concept structure of Hwa-Byung in middle aged Korean women. Health Care for International, 23, 389–397.

Pearlin, L. I., & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19(1), 2–21.

Pulgar, C. A., Trejo, G., Suerken, C., Ip, E. H., Arcury, T. A., & Quandt, S. A. (2016). Economic hardship and depression among women in Latino farmworker families. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 18(3), 497–504.

Rhee, S. (2015). Domestic violence in the Korean American family. The Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 24(1), 63–77.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books.

Shin, H., Han, H., & Kim, M. (2007). Predictors of psychological well-being amongst Korean immigrants to the United States: A structured interview survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(3), 415–426.

Shin, J. Y., D’Antonio, E., Son, H., Kim, S. A., & Park, Y. (2011). Bullying and discrimination experiences among Korean-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescents, 34(5), 873–883.

Sin, M. K., Jordan, P., & Park, J. (2011). Perceptions of depression in Korean American immigrants. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32(3), 177–183.

Suh, S. (2013). Stories to be told: Korean doctors between hwa-byung (Fire-Illness) and depression, 1970–2011. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 37(1), 81–104.

Thoits, P. A. (1986). Social support as coping assistance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 416–423.

Zhen, Y. (2013). The effects of English proficiency on earnings of U.S. foreign-born immigrants: Does gender matter? Journal of Finance and Economics, 1(1), 27–41.

Zong, J., & Batalova, J. (2014). Korean Immigrants in the United States. Washington DC: Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/korean-immigrants-united-states.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J. The Role of Economic Stress and Coping Resources in Predicting Hwabyung Symptoms. Community Ment Health J 55, 211–221 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0293-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0293-1