Abstract

This article presents the qualitative analysis of reports obtained through participant observations collected over a 4-year period in a series of suicide survivor self-help group meetings. It analysed how grievers’ healing was managed by their own support. The longitudinal study was focused on self/other blame and forgiveness. Results show how self-blame was continuously present along all the period and how it increased when new participants entered the group. This finding indicates that self-blame characterizes especially the beginning of the participation, and that any new entrance rekindles the problem. However, no participant had ever definitively demonstrated self-forgiveness, while a general forgiveness appeared when self-blame stopped. It is also suggested how to facilitate the elaboration of self-blame and forgiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although suicide is a relatively rare event, the number of suicide survivors (defined as partners, parents, relatives and close friends) is considerable. Psychological effects of the trauma caused by suicide are quite various, involving the emotional, behavioural, physiological areas, and the following post-traumatic stress symptoms are similar to the consequences of violence (Crosby and Sacks 2002; Knight 2006; Mitchell et al. 2004). Mourners may be differentiated for many characteristics (Kristensen et al. 2014; Reed 1998; Worden 2009). For example, Cerel et al. (2014) identified four types of survivors: people who know someone who died by suicide but do not experience the severity of grief symptoms; mourners who experience significant psychological distress; survivors with short-term grief; and, long-term bereaved, with protracted reactions and need of professional help. The last three types can share some common feelings: shock, anxiety, sadness, despondency, depression and disbelief (Shear and Smith-Caroff 2002).

Additionally, some aggravating factors may join these painful conditions. In fact, since the fundamental bond of social trust is the refusal of death (Testoni 2016), the work of grief may be worsened by the social disapproval, from which isolation and many other difficulties derive (Worden 2009). Being trust the basis of any relationship constituting the social fabric (Carter and Weber 2003), the common representation of the suicidal act is a “betrayal of trust” (Jacobs 1967), and the following attribution of cause and responsibility for suicide implies complex blaming processes (Shaver 1985). While it is internalized, real or perceived stigmatization becomes self-stigma, causing in survivors intense reactions of shame, worthlessness and self-blame (Pitman et al. 2016). Such troubles hamper the possibilities to overcome the trauma by sharing with others own emotions, which are mostly inhibited, being stacked with censure, guilt, regret, loneliness, and helplessness. Furthermore, the need to know why the painful loss happened appears to mix to a high level of self-blame (Bailley et al. 1999; Bell et al. 2012; Range 1996). Blame/worthiness is characterized by long-lasting rumination, harsh feelings of being criticized, judged and condemned by society (Bailley et al. 1999; Bell et al. 2012; Grad and Zavasnik 1999; Harwood et al. 2002; Jordan 2001; Pitman et al. 2016; Silverman et al. 1994). In fact, attributional processes are particularly difficult, and incur in many attributional biases. As literature indicates (Devis et al. 1996), people who experienced traumatic life events may blame themselves by assuming that they could have avoided the accident. The acceptance of personal responsibility by these individuals (who actually did nothing to cause the problem) has stimulated considerable debate in the literature related to coping. In particular, Supiano (2012) reports five types of causal attributions in grief work: personal, external, psycho-social, un-explicable and predestination. In his opinion, the capacity of suicide survivors to grieve with resolution is mediated by their ability to make sense of the death in a way that actualizes a personal identity of self-acceptance.

In the area of trauma, it has been also evidenced the importance of a factor improving self-acceptance: the capability of forgiving. Forgiveness is not synonymous with condoning, excusing, reconciling and forgetting (Baskin and Enright 2004), but is defined as a free act chosen to give up the resentment experienced against a hurting action committed by someone else (Baskin and Enright 2004; Enright et al. 1998; Lamb 2005; Worthington et al. 2000). This deliberative act requires four core conditions: being injured in a deep way; the injurer is responsible for the damage regardless of intentions; the forgiver freely choose to decrease resentment and revenge against the injurer; the forgiver voluntarily choose to forgive and does not require an apology by the injurer (Enright et al. 1991; Freedman and Zarifkar 2016; Holmgren 1993). In self-forgiveness, persons who want to reconcile with themselves present a similar structure (Hall and Fincham 2005). Flanigan (1992) identified five phases of forgiveness: identify the hut and interpreting its meaning; choosing to re-equilibrate own life; balancing the scales that means to be aware of the existential cost of the hurt and of forgiveness; choosing to forgive the injurer. With regard to suicide survivors, there are two types of forgiveness: interpersonal (toward the others) and self-forgiveness. Self-forgiveness is the willingness to abandon self-resentment to act benevolently toward the self (Enright 1996; Hall and Fincham 2005; Petrocchi et al. 2013; Worthington 2005).

Research shows that to promote forgiveness and self-forgiveness processes it is necessary helping people to overcome resentment and bitterness (Enright and Fitzgibbons 2000; Freedman and Zarifkar 2016). This process requires expressing anger, examining the injurer from an empathetic point of view, considering the choice of forgiveness and deepening the positive feelings related to resilience (Lamb 2005). Enright et al. (1991) implemented the model of a possible forgiveness practice describing four phases and twenty units. In the first phase, “The Uncovering Phase of Forgiveness” (Units 1–8), individuals explore their defence mechanism and their blame processes. In the second phase, “The Decision Phase of Forgiveness” (Units 9–11), people start considering the option to forgive. In the third phase, “The Work Phase of Forgiveness” (Units 12–15), future forgivers work on understanding the injury and accepting the pain. In the final phase, “The Discovery Phase of Forgiveness” (Units 16–20), they find meaning in their sufferance, discovering their need for forgiveness and the feel of freedom that this choice guarantees. This perspective may result appropriate in helping suicide survivors, who blame themselves and other people for the death of their beloved one (Lee et al. 2015; Petrocchi et al. 2013). Some studies confirmed this hypothesis, showing how such a strategy can decrease anxiety, improving hopefulness and self-esteem (Al-Mabuk and Downs 1996).

There are many methodologies aimed at supporting suicide survivors, but self-help groups,—composed by a limited number of mourners—seem to be particularly effective, because their dynamics relies on the impact of social support, which involves emotions, approval, information-sharing and instrumental help (Clark 1992; De Leo 2009; Feigelman and Feigelman 2008; Gilat and Shahar 2009; Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2014). Self-help groups permit to come out from isolation, freely discussing possible motives for suicide, experimenting the universality of feelings and accepting the loss by improving empathy, asking for information, explanations and advice, while respecting others’ opinions and supporting each other (Hawton and Simkin 2008; Messina et al. 2006). Their main goals are personal empowerment, share experience, increase solidarity, stimulate hope and personal growth, learn how to cope with pain, return to normal life and, last but not least, forgive themselves and the others (Cluck and Cline 2009; De Leo 2009; De Leo et al. 2011; Lifeline Australia 2009; Osterweis 1984; Padula 2005; Pangrazzi 2016).

The Research

Aims

The main objective of this research was to verify whether the forgiveness process spontaneously appear in a self-help group composed by suicide survivors and how it matches with blame processes. In fact, following the perspective of Supiano (2012) and of Lee et al. (2015), we wanted to analyze how the different types of causal attributions, self or other blame and responsibility, intervene, and how these explanations are intertwined with forgiveness processes. Secondarily, we wanted to check the effects of the self-help group intervention, analysing if the participants had an elaboration and/or a decrease of the feelings of self/other-blame and an increase of forgiveness and acceptance of the relative’s suicide.Footnote 1

Participants

The self-help group participated in the activities (i.e. creative workshops) of the De Leo Fund Onlus (Padova—Italy). This organisation, the first aim of which is to help grieving people who experienced a traumatic loss, offers various services as courses, workshops, help-lines, forum and online chat, psychological support and self-help groups for suicide survivors. The self-help group here studied was composed by 2 men and 8 women. Among them, 6 (1 man and 5 women) had a continuous participation and 4 (1 man and 3 women) dropped out. The grievers participated at the group sessions from April 2013 to May 2016, on average one time per week. Every session took 1 h 30 min. Seven of the participants lost a son, two their father and one her husband. Five suicides were performed by hanging, one by drowning, two by shooting and two by defenestration. Five participants found the corpses, one was informed of the death by the police, one by the Italian embassy, two by relatives or acquaintances and one was present when the suicide were committed. At the time of the entry in the group, seven participants have lost their loved one from less than 1 year, two within a decade and one from more than 10 years. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the group.

Method

The research adopted a qualitative approach (Camic et al. 2003), following the CORE-Q check-list (Tong et al. 2007), in order to analyse the evolution of the feelings of guilt, blame and forgiveness, and their intertwines.

The body of the analysis was composed by the collected reports derived from narrations of the support group members, which were observed over a 4-year period by two psychologists. The reports were written by one of the two psychologists who conducted the group. Although this method implies some limitations as regards to validity in generalizing results, it is still possible to guarantee reliability due to the combination of the emic view of the observers and the interpretative etic view of the researchers, which helps understanding the critical issues emerged from the texts (Oliffe and Bottorff 2006). The facilitator and the observer of the self-help group, the two coders were psychologists and authors of this article, who followed a course at the same centre, focused on the strategies for helping post-traumatic mourners. A particular attention was paid to the reconciliation dynamics and their potential for the elaboration of grief. They discussed about the most important variables and themes to recognize in the text of the reports in order to code them in the qualitative analysis.

Data were analysed using the framework method for thematic qualitative analysis, which allows sources to be examined in terms of their principal concepts or themes (Marshall and Rossman 1999). Thematic analysis was performed in two steps. The first one classified the three main families of categories, defining the timeline of their frequencies. The second one was specifically focused on the analysis of the texts, developed following prior categories and ideas. The former were the basic “pre-figured themes” (causal attribution, self/other-blame, guilt-disorders and forgiveness) from which the latter arose as unexpected topic. The process was divided into six main phases: preparatory organization; generation of categories or themes; coding data; testing emergent ideas; searching for alternative explanations; writing up the report (Marshall and Rossman 1999). The texts were processed with Atlas.ti, a software for qualitative analysis of texts. The analysis results in network graphs, describing logical relationships between concepts and categories identified by researchers. The topic areas then form the basis for the structure of the report, within which extracts may be used to illustrate key findings.

Results

The Thematic Analysis: Phase 1—Timeline of the Themes

Analyzing the reports of the group sessions, we quantified the frequency in which there was the presence of feelings of self-blame, guilt to external contexts, psycho-physical disorders, and forgiveness, and detected the phases of the group dynamics, in particular the entry and exit of some members.

Self-blame had been remaining constant during all the 4-year group sessions and its level was generally high. Furthermore, participants never explicitly forgave themselves. However, there were periods in which self-blame decreased significantly: levels slacked off between February 2014 and April 2014 and this could be related to the entry in the group of a new participant, who did not self-blame. After the exit of this member, the self-blame level seamlessly increased until July 2014, when two other participants without self-blame process entered, promoting a decrease of this dynamic, which however did not completely disappear. In February 2015, it increased again, possibly in relation to a new mourner characterized by intense negative sentiments. In November 2015, immediately after the exit of such a person, self-blame decreased. As indicated in the Graph 1, generally, self-blame had been continuously present in the first year and, after such a period it appeared increasing especially when new participants entered the group. This finding indicates that self-blame characterizes especially the beginning of the participation of survivors in the self-help group meetings, and that their entrance rekindles the problem, if the new member has high levels of self-blame. On the contrary, if the new member has low levels of self-blame, the problem seems to decrease.

Other-blaming maintains a different trend form than the previous one. In fact, it had a fluctuating presence. In particular, it increases from February 2014 to April 2014, when new participants who did not self-blame oriented the discussion on social responsibilities. This results highlights that self-blame and other-blame are mutually excluding.

Psycho-physical disorders had been indicated as the most important causes of the suicide choice, along all the first year of group sessions. In fact, they rarely appeared during the following 2 years and, in particular, significantly decreased between February 2015 and February 2016, when a participant with high scores of self-blame and other-blame but low disorders’ guilt levels entered. Indeed, in the last months of that year, the scores of self-blame, other-blame and disorders’ guilt increased. In such a period, the personal problems of survivors begun being shared (i.e. problems in family relationship, suffering other deaths or illnesses, especially of relatives), evidencing that, while remaining extant, the difficulties related to the suicide had not been occupying the whole area of suffering.

Forgiveness spontaneously appeared only three times. This was particularly evident in December 2014, when a mourner introduced the problem inherent to the understanding of the terrible choice of their beloved one. Despite forgiveness was not stated openly, participants showed higher acceptance of such an outcome. Anyhow, no participant had ever definitively and spontaneously demonstrated self-forgiveness. Examining Graph 1, it is possible to notice on the one hand that forgiveness appeared when self-blame stopped, on the other that self-blame and forgiveness stopped when other-blame and disorders took the lead.

Thematic Analysis: Phase 2—The Contents

Looking for Causes (Self-Blame and Other-Blame)

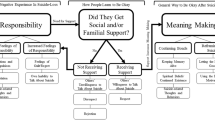

Participants were constantly focused on making sense of the suicidal choice, looking for the “personal” (of the survivor), the “external” (of the society), and the “person who died by suicide” reasons, which caused the extreme act. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the personal causes inhere in what the survivors could have or could not have done to avoid suicide. In this area, many expressions of self-blame appear, among which the inability to understand the situation and to modify the personal relationships emerges for importance. Typical expressions are the following, “Maybe I’ve failed or I’ve made a mistake in educating my son [81:48]”, “Maybe we haven’t done enough [6:38]”, “Maybe I could have helped him more [76:19]”, “Maybe I haven’t really understood his pain [61:13]”. Feeling of inadequacy and related blame were extended to close relationships, especially partners and relatives, “Would my son still be alive if I had left my husband? [39:18]”, “Maybe my husband and I haven’t been good parents; this must have created huge problems in our children [85:14]”, “During arguments, I always protected my husband instead of my sons [20:16]”.

Even if survivors could not have a direct control on external causes, blame involves also all family members, the intimate and professional relationships of the deceased person, and the health system (physicians and psychotherapists). Conflicts, especially those within the family, were often mentioned: “He had lots and lots of discussions with his father [12:19]”, “She was really angry with her husband, she thought that he was absent and indifferent [23:12]”, “My son had great difficulties to talk to his father [54:13]”, “I suffer because the bad relationships between my son and my husband could have determined my son’s choice [79:11]”. Similarly, participants denounced the school as an unsafe and violent context, unable to manage the distress of their children: “My son was bullied at school [18:11]”, “School isn’t able to perceive youth’s pain” [14:12], “No one, neither professors nor classmates were interested in intervening on time [18:14]”. Friends are blamed for having done nothing to prevent suicide: “Their friends haven’t helped and understood our sons [12:13]”, “Maybe his friends have noticed his distress but they haven’t done nothing [72:6]” or to have, in some ways, encouraged it: “Maybe someone betrayed him and that let him feel so humiliated to choose suicide [76:34]”. A different kind of other-blame involves the work context, which is considered responsible of negative influences: “Work place had a negative influence in the suicide’s choice of my husband [44:14]”, “My husband was too busy and too worried because of work troubles [78:19]”. A particular denounce was addressed to health services, where physicians and psychologists were unable to diagnose mental disorders in their relative: “The doctors underestimated the problem. They told me that my son was affected by hypothyroidism [5:27]”, “I don’t know how it can be possible that after 1 year of psychotherapy the problem did not emerged and was not sufficiently analyzed [72:31]”, “In my opinion, I think that my son’s psychologist worked too superficially [72:32]”.

Causal attributions related to the persons who died by suicide were mostly described utilizing medical language: “They told me that my son had a bipolar disorder and was constantly depressed [32:3]”, “They told me that my husband was depressed; he thought that he had made a mistake on his work but it wasn’t real [41:7]”.

Finally, causes could also be inexplicable or incomprehensible: “Maybe we won’t never know the real causes of our relatives’ suicide [31:34]”; or due to a tragic predestination determined by the confluence of several factors: “The pain of our sons was so great that everything we had done couldn’t change their choice [27:15]”, “He was too much upset to do something different than suicide [18:22]”.

Forgiveness

Forgiveness, as the Fig. 2 illustrates, is related to some aspects arisen during three main occasions in which this issue was considered. The most important component of such a factor was self-acceptance, which seems to be independent from the forgiveness of the suicidal victim. In fact, it was ambivalent, appearing as a contrast between the need to silence the self-blame versus the belief that it is impossible: “I try, but I have a great difficulty to forgive myself [2:25]”, “I cannot forgive myself for not having understood [3:10]”. The attempt to forgive the deceased person was more complex, and tallied some different intertwined facets. The first one showed the will to justify the act, through generalization and theoretical explanations, which again utilize scientific representations of handicaps on which suicidal people could not have control: “We can justify them, because in suicidal people there is a genetic predisposition which makes them unable to cope with difficulties; maybe this thing exposes them to suicide risk [16:21]”, “Life events may lead to particular directions and reactions [51:24]”. However, when this kind of reasoning ended, the reflection on the existential condition begun, confirming the representations of handicaps afflicting the persons who died, limiting their control on the events of a normal life: “People who want to choose suicide can’t listen to others and cannot accept their help [72:7]”, “They don’t have a clear vision of what they are really experiencing [27:13]”. Then, forgiveness seemed to be the result of the acceptance of the death and of the suicide choice, which was attributed to an unbearable existential sufferance derived from psychological restrictions: “I forgive him because he suffered too much and was unable to manage the discomfort [3:11]”, “I forgive his choice because I know that his sadden was too big [21:16]”. Sometime, process of forgiveness resulted in being facilitated by the presence of a note or a letter left by the deceased, where the reason for dying by suicide was explained without blaming anyone. “My son’s letter helps me to forgive him for his choice and to accept it [28:8]”.

Conclusions

Many researchers explored why people blame themselves for the events that befall them (Devis et al. 1996). Most have suggested that the blame processes produce some kind of biases, aimed at maintaining a high sense of control over their environment. This literature underlines that such distortions characterize the phenomenon of self-blame observed among those who have experienced traumatic life events (Frazier 1990).

This qualitative study focused on the relationships between attributional processes and forgiveness, through self-blame and other-blame, which appeared during the sessions of a 4-year help-group and was registered by two observers. The analysis showed that feelings of guilt never vanished, despite participants tried hard to cope with their experience and with their negative emotions. This consequence might be caused by the fact that the group was ‘open’; so, whenever a new participant entered in the group, inevitably self-blame was reactivated. This first effect permit us to underline that the most important attributional process was inherent to the personal blaming process for the tragic event, which crossed as a red line all the development of the issues appeared in the meetings. Confirming literature (Devis et al. 1996), indeed participants presented high levels of self-blame related to the idea that they could have prevented the tragedy “if only” they had done something right instead of something wrong. However, running in parallel, they frequently indicated the context as much guilt as they were. In fact, the exigence to find a cause of the suicide oriented their research of the guilty also among family relationships, friends, job networks, and even the health system. Conflicts, superficiality, bullying, job worries, indifference, incompetence, misunderstandings, envy, negative occurrences were only a part of significant external affects from which depression and existential sufferance derived for the suicidal relative. This trait is particularly important, because, despite the theme of suicide is socially stigmatized and substantially not accepted by mourners as well, the attributional processes did not incur in the bias of dispositional versus situational causes, with respect to the reasons for performing the fatal act. This effect can be interpreted as the result of a latent exigence of forgiving the suicidal victim and consequently themselves. Indeed, it is possible to imagine that the stress caused by the blaming flow, which is constantly pouring also when new adverse experiences burst into their life, presses at the threshold of survivors’ endurance requiring a solution. Undeniably, if on one hand forgiveness of suicidal relatives mostly appeared between the first and the second year, indicating the wish of accepting the suicide outcome, on the other it never appeared as self-forgiveness and it was never related to the recognition of the need of starting again a normal life.

With regard to the limits of the intervention, It is important to underline that the strategy that this self-help group followed respected the open ended strategy. While a facilitator helped participants to correctly experience the group, without orienting the narrations, on the other hand, the group seemed to be anchored to the early narration of blame. The problem has been already partially considered by literature. Feigelman and Feigelman (2011) highlights that the structure of this kind of groups with members continuously changing, may allow new participants to enter the group quickly and easily, but at the same time longer-term members could feel that the focus on early grief issues force them to re-visit continuously the same grief issues. Indeed, as Cerel et al. (2009), Myers and Fine indicate, it is possible that the open-ended format leads to individuals being re-distressed by hearing stories of traumatic deaths over and over, without learning appropriate coping techniques. Our finds confirm such quandaries, however it is important to point out the limit of our concerns and of the entire study, which focused only on the reports of a single mutual support group, participating to the activities of the De Leo Fund. In order to better verify such a hypothesis, the research should be extended to additional groups that followed the same reporting method. If so, it could be possible to hypothesize that the introduction of a facilitator able to orient narrations toward the themes of forgiveness, developing with participants the competence required by the assumption of this existential aim, may be of help. Indeed, the future direction of the present research could be exactly in such a perspective. Further developments of the study could be realized confronting open and close groups, with or without such a kind of facilitators, in order to check the differences among self-other/blame and forgiveness.

Notes

The study followed APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Furthermore it obtained the approval of the Ethics Commission of the Psychological Departments of the University of Padova.

References

Al-Mabuk, R. H., & Downs, W. R. (1996). Forgiveness therapy with parents of adolescent suicide victims. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 7(2), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1300/J085V07N02_02.

Bailley, S. E., Kral, M. J., & Dunham, K. (1999). Survivors of suicide do grieve differently: Empirical support for a common sense proposition. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 29(3), 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.1999.tb00301.x.

Baskin, T. W., & Enright, R. D. (2004). Intervention studies on forgiveness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling and Development, 82(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00288.x.

Bell, J., Stanley, N., Mallon, S., & Manthorpe, J. (2012). Life will never be the same again: Examining grief in survivors bereaved by young suicide. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 20(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.2190/IL.20.1.e.

Camic, P. M., Rhodes, J. E., & Yardley, L. (2003). Qualitative research in psychology. Expanding perspectives in methodology and design. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Carter, A. I., & Weber, L. R. (2003). The social construction of trust. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Cerel, J., McIntosh, J. L., Neimeyer, R. A., Maple, M., & Marshall, D. (2014). The continuum of “survivorship”: Definitional issues in the aftermath of suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(6), 591–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12093.

Cerel, J., Padgett, J. H., Conwell, Y., & Reed, G. A. (2009). A call for research: The need to better understand the impact of support groups for suicide survivors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39(3), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2009.39.3.269.

Clark, S. (1992). The role of the ‘Bereaved Through Suicide Support Group’ in the care of the bereaved. Canberra: ACT, Australian Institute of Criminology.

Cluck, G. G., & Cline, R. J. (2009). The circle of others: Self-help groups for the bereaved. Communication Quarterly, 34(3), 306–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463378609369642.

Crosby, A. E., & Sacks, J. J. (2002). Exposure to suicide: Incidence and association with suicidal ideation and behavior: United States, 1994. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 32(3), 321–328. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.32.3.321.22170.

De Leo, D. (2009). Suicide bereavement support group facilitation. Australia: Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing.

De Leo, D., Cimitan, A., Dyregrov, K., Grad, O., & Andriessen, K. (2011). Lutto traumatico: L’aiuto ai sopravvissuti. Aspetti teorici ed interventi assistenziali. Roma: Alpes Italia.

Devis, C., Lehman, G., Silver, D. R., Wortman, R. C., C. B., & Ellard, J. H. (1996). Self-blame following a traumatic event: The role of perceived avoidability. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 57–67.

Enright, R. D. (1996). Counseling within the forgiveness triad: On forgiving, receiving forgiveness, and self-forgiveness. Counseling & Values, 40(2), 107–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.1996.tb00844.x.

Enright, R. D., Al-Mabuk, R. H., Conroy, P., Eastin, D., Freedman, S., Golden, S., … Sarinopoulos, I. (1991). The moral development of forgiveness. In W. Kurtines & J. Gewirtz (Eds.), Moral behavior and development (pp. 123–152). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Enright, R. D., & Fitzgibbons, R. (2000). Helping clients forgive: An empirical guide for resolving anger and restoring hope. Washington, DC: APA.

Enright, R. D., Freedman, S., & Rique, J. (1998). The psychology of interpersonal forgiveness. In R. D. Enright & J. North (Eds.), Exploring forgiveness (pp. 46–62). Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin.

Feigelman, B., & Feigelman, W. (2008). Surviving after suicide loss: The healing potential of suicide survivor support groups. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 16(4), 285–304. https://doi.org/10.2190/IL.16.4.b.

Feigelman, B., & Feigelman, W. (2011). Suicide survivor support groups: Comings and goings, part I. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 19(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.2190/IL.19.2.e.

Flanigan, B. (1992). Forgiving the unforgivable: Overcoming the bitter legacy of intimate wounds. New York: Macmillan.

Frazier, P. A. (1990). Victim attributions and post-rape trauma. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 298–304.

Freedman, S., & Zarifkar, T. (2016). The psychology of interpersonal forgiveness and guidelines for forgiveness therapy: What therapists need to know to help their clients forgive. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 3(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000087.

Gilat, I., & Shahar, G. (2009). Suicide prevention by online support groups: An action theory-based model of emotional first aid. Archives of Suicide Research, 13(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110802572148.

Grad, O. T., & Zavasnik, A. (1999). Phenomenology of bereavement process after suicide, traffic accident and terminal illness (in spouses). Archives of Suicide Research, 5(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811119908258325.

Hall, J. H., & Fincham, F. D. (2005). Self-forgiveness: The stepchild of forgiveness research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(5), 621–637. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2005.24.5.621.

Harwood, D., Hawton, K., Hope, T., & Jacoby, R. (2002). The grief experiences and needs of bereaved relatives and friends of older people dying through suicide: A descriptive and case-control study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 72(2), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00462-1.

Hawton, K., & Simkin, S. (2008). Help is at hand: A resource for people bereaved by suicide and other sudden, traumatic death. Oxford: Centre for Suicide Research, University of Oxford, Department of Health.

Holmgren, M. (1993). Forgiveness and the intrinsic value of persons. American Philosophical Quarterly, 30(4), 341–351.

Jacobs, J. (1967). A phenomenological study of suicide notes. Social Problems, 15(1), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/798870.

Jordan, J. R. (2001). Is suicide bereavement different? A reassessment of the literature. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 31(1), 91–102.

Knight, C. (2006). Groups for individuals with traumatic histories: Practice considerations for social workers. Social Work, 51(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/51.1.20.

Kristensen, P., Weisæth, L., & Heir, T. (2014). Bereavement and mental health after sudden and violent losses: A review. Psychiatry, 75(1), 76–97. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2012.75.1.76.

Lamb, S. (2005). Forgiveness therapy: The context and conflict. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psycholog, 25(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0091251.

Lee, E., Enright, R., & Kim, J. (2015). Forgiveness postvention with a survivor of suicide following a loved one suicide: A case study. Social Sciences, 4(3), 688–699. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030688.

Lifeline Australia (2009). Standards and guidelines for suicide bereavement support groups. Australia: Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. (1999). Designing qualitative research (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

Messina, S., La Cascia, C., & Nuccio, L. (2006). Suicidio. E poi… Famiglia e suicidio. I vissuti di chi resta. Palermo: Afipres.

Mitchell, A. M., Kim, Y., Prigerson, H. G., & Mortimer-Stephens, M. K. (2004). Compli- cated grief in survivors of suicide. Crisis, 25(1), 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.25.1.12.

Oliffe, J. L., & Bottorff, J. L. (2006). Innovative practice: Ethnography and men’s health research. The Journal of Men’s Health & Gender, 3(1), 104–109.

Osterweis, M. (1984). Bereavement intervention programs. In M. Osterweis, F. Solomon & M. Green (Eds.), Bereavement: Reactions, consequences and care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press US.

Padula, L. (2005). L’elaborazione del lutto: Indagine sull’offerta di aiuto in Internet. Parma: Università degli Studi di Parma.

Pangrazzi, A. (2016). Il dolore non è per sempre: Il mutuo aiuto nel lutto e nelle altre perdite. Trento: Erickson.

Petrocchi, N., Barcaccia, B., & Couyoumdjian, A. (2013). Il perdono di sé. Analisi del costrutto e possibili applicazioni cliniche. In B. Barcaccia & F. Mancini (Eds.), Teoria e clinica del perdono (pp. 185–229). Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore.

Pitman, A. L., Osborn, D. P. J., Rantell, K., & King, M. B. (2016). The stigma perceived by people bereaved by suicide and other sudden deaths: A cross-sectional UK study of 3432 bereaved adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 87, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.05.009.

Range, L. M. (1996). When a loss is due to suicide: Unique aspects of bereavement. Interpersonal Loss, 1(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325029608415460.

Reed, M. D. (1998). Predicting grief symptomatology among the suddenly bereaved. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 28(3), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.1998.tb00858.x.

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Havinga, P., Van Ballegooijen, W., Delfosse, L., Mokkenstorm, J., & Boon, B. (2014). What do the bereaved by suicide communicate in online support groups? Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 35(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000225.

Shaver, G. K. (1985). The attribution of blame: Causality, responsibility and blameworthiness. New York: Springer.

Shear, M. K., & Smith-Caroff, K. (2002). Traumatic loss and the syndrome of complicated grief. PTSD Research Quarterly, 13(1), 1–8.

Silverman, E., Range, L., & Overholser, J. (1994). Bereavement from suicide as compared to other forms of bereavement. OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying, 30(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.2190/BPLN-DAG8-7F07-0BKP.

Supiano, K. P. (2012). Sense-making in suicide survivorship: A qualitative study of the effect of grief support group participation. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 17(6), 489–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2012.665298.

Testoni, I. (2016). Psicologia del lutto e del morire: Dal lavoro clinico alla death education [The psychology of death and mourning: From clinical work to death education]. Psicoterapia e Scienze Umane, 50(2), 229–252. https://doi.org/10.3280/PU2016-002004.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

Worden, J. W. (2009). Grief counseling and grief therapy. A handbook for the mental health practitioner. New York: Springer.

Worthington, E. L. (2005). Handbook of forgiveness. New York: Routledge.

Worthington, E. L., Sandage, S., & Berry, J. W. (2000). Group interventions to promote forgiveness: What researchers and clinicians ought to know. In M. E. McCullough, K. Pargament & C. E. Thoresen (Eds.), Forgiveness: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 228–253). New York: Guilford Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Testoni, I., Francescon, E., De Leo, D. et al. Forgiveness and Blame Among Suicide Survivors: A Qualitative Analysis on Reports of 4-Year Self-Help-Group Meetings. Community Ment Health J 55, 360–368 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0291-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0291-3