Abstract

The aim of the present study was to assess the relationship between illness-related characteristics, such as symptom severity and psychosocial functioning, and specific aspects of family functioning both in patients experiencing their first episode of psychosis (FEP) and chronically ill patients. A total of 50 FEP and 50 chronic patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (most recent episode manic severe with psychotic features) and their family caregivers participated in the study. Family functioning was evaluated in terms of cohesion and flexibility (FACES IV Package), expressed emotion (FQ), family burden (FBS) and caregivers’ psychological distress (GHQ-28). Patients’ symptom severity (BPRS) and psychosocial functioning (GAS) were assessed by their treating psychiatrist within 2 weeks from the caregivers’ assessment. Increased symptom severity was associated with greater dysfunction in terms of family cohesion and flexibility (β coefficient −0.13; 95 % CI −0.23, −0.03), increased caregivers’ EE levels on the form of emotional overinvolvement (β coefficient 1.03; 95 % CI 0.02, 2.03), and psychological distress (β coefficient 3.37; 95 % CI 1.29, 5.45). Family burden was found to be significantly related to both symptom severity (β coefficient 3.01; 95 % CI 1.50, 4.51) and patient’s functioning (β coefficient −2.04; 95 % CI −3.55, −0.53). No significant interaction effect of chronicity was observed in the afore-mentioned associations. These findings indicate that severe psychopathology and patient’s low psychosocial functioning are associated with poor family functioning. It appears that the effect for family function is significant from the early stages of the illness. Thus, early psychoeducational interventions should focus on patients with severe symptomatology and impaired functioning and their families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Families play a central role in providing long-term care and support to patients with psychosis. When a family member has been diagnosed with schizophrenia or related psychotic disorders, the whole family has to cope with the resulting medical appointments and hospital admissions and with a series of changes in family interactions. Since families have assumed a greater role in providing care for relatives with psychosis, understanding the determinants of dysfunctional family dynamics has become an important focus of research.

The study of family interactions is especially important in the early stages of the illness when most of the changes are observed (Birchwood and Macmillan 1993). The past several decades have produced two important areas of inquiry involving families of patients experiencing their first episode of psychosis (FEP). One line of inquiry has focused on family communication patterns and interactions, usually characterized as expressed emotion (EE), and the other on family burden (FB) and experience of caring for an ill relative [see review by Koutra et al. (2014c)]. Several decades of research have established EE as a highly reliable psychosocial predictor of relapse in psychosis from the early stages of the illness and later on (Alvarez-Jimenez et al. 2012; Butzlaff and Hooley 1998). Researchers, following the diathesis-stress model of psychopathology, have proposed that EE is an environmental stressor that can precipitate or cause relapse of psychosis among genetically vulnerable individuals (Hooley and Hiller 2000).

The symptoms of psychosis have been investigated in a variety of studies aiming to elucidate their impact on caregivers. Recent investigations that have included FEP patients suggest that patient’s symptomatology and psychosocial functioning may have a limited effect on family relationships. A number of studies have shown no relation between symptom severity and impaired functioning in family EE (Heikkila et al. 2002, 2006; Meneghelli et al. 2011; Moller-Leimkuhler 2005; Raune et al. 2004), whereas only one study revealed that patients’ symptoms were positively correlated with both the caregiver-rated and patient-rated EE (Mo et al. 2008). In a similar vein, some studies have shown that symptom severity was not linked to FB (Moller-Leimkuhler 2005) or caregivers’ psychological distress (Addington et al. 2003; McCleery et al. 2007), while others suggested that the level of FB was predicted by patient’s symptomatology (Tennakoon et al. 2000; Wolthaus et al. 2002).

A variety of studies supported a strong association between illness-related variables and family environment of patients with chronic and enduring psychosis. Specifically, family EE was found to be influenced by patient’s total symptom severity and negative symptoms (King 2000). Also, caregivers’ greater burden was predicted by patients’ increased symptom severity (Grandon et al. 2008; Hjarthag et al. 2010; Hou et al. 2008; Lowyck et al. 2004; Perlick et al. 2006; Provencher and Mueser 1997; Roick et al. 2007; Schene et al. 1998) and impaired functioning (Hjarthag et al. 2010; Tang et al. 2008). Some studies examined the symptoms divided into positive and negative symptoms, and showed that higher burden was predicted by patients’ both increased positive and negative symptoms (Lowyck et al. 2004; Perlick et al. 2006; Provencher and Mueser 1997; Roick et al. 2007; Schene et al. 1998) or by positive symptoms alone (Grandon et al. 2008; Tang et al. 2008).

Deficits in psychosocial functioning can be observed in early stages of psychotic disorders, during acute exacerbations, and as part of the residual syndrome (Ballon et al. 2007). Such impairments include poor social interaction, difficulties in maintaining relationships with family and friends, and/or inadequate performance in the workplace (Green et al. 2000). Moreover, the social difficulties and deficits that are apparent during the early stages of the illness resemble the difficulties and deficits that are characteristic of patients in the later stages of the illness (Hooley 2000).

In Greece, the vast majority of patients diagnosed with psychosis return to their communities (Basta et al. 2013; Madianos et al. 1997) after discharge from hospital and depend on the assistance and continued involvement of their families. While living with a patient with long-term psychosis, the majority of family members experience stigma-related phenomena which are associated with changes in social status, isolation and constant tension (Koukia and Madianos 2005). Like other Mediterranean societies, Greek society does not easily tolerate deviant behaviour, although some changes in attitudes toward mental illness were observed over the last decades (Madianos et al. 1999). In addition, although the Greek family is seemingly a nuclear family (Georgas 1999; Katakis 1998; Papadiotis and Softas-Nall 2006; Softas-Nall 2003), in reality it functions as an extended one (Georgas 1999, 2000) characterized by cohesiveness and tight knit bonds and interactions. In this regard, illness in one family member may affect family dynamics and result in substantial burden for the entire family.

The aim of the present study is to examine the effect of patient’s symptom severity and psychosocial functioning in a variety of aspects of family life in a Greek sample of FEP and chronic patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. To our knowledge, thus far no studies have been conducted in families of either FEP or chronic patients to ascertain patient’s symptom severity and functioning on family cohesion and flexibility, whereas such research with regard to caregiver’s EE status and FB is limited. Family functioning is a multifaceted concept which includes numerous constructs including family cohesion and flexibility and we suggest that many dimensions need to be assessed for a fuller understanding of such a complex entity as the family. In this paper, we tested the hypothesis that family dysfunction in terms of cohesion and flexibility, as well as high levels of relatives’ EE, FB, and psychological distress would be related to patient’s greater severity of illness and impaired functioning. And if dysfunctional interactions among family members are associated with patient’s symptomatology and functional level, one would expect that these associations would differ in patients due to confounding variables, such as chronicity of the illness.

Methods

Participants

Sample size estimation was based on medium expected effect sizes, according to Cohen’s criteria (1988), for power 0.80 and confidence level 0.05. A total of 104 patients consecutively admitted to the Inpatient Psychiatric Unit of the University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece, and their family caregivers were contacted and informed about the purpose of the present study during a 12-month period (October 2011–2012). Finally, 100 (response rate 96.1 %) patients and their family caregivers agreed to participate. The sample consisted of 50 FEP patients and 50 chronic patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (most recent episode manic severe with psychotic features). For the purposes of this study, FEP patients were recruited upon first hospitalization whereas chronic patients had two or more hospitalizations, while the duration of illness was also taken into consideration. Thus, the vast majority of chronic patients (74.0 %) had an onset of illness at 4 years or longer and more frequent hospitalizations (M = 3.88; SD = 2.45), whereas the majority of FEP patients had an onset of illness of 12 months or less (40.0 %) or 1–4 years (34.0 %) and only one hospitalization (Koutra et al. 2014b). In addition, a thorough search and assessment of the patients’ medical records was done by the research team to ensure that the present psychotic episode was their first (for FEP patients), second or other episode (for chronic patients). The key caregiver was defined as the person who provides the most support devoting a substantial number of hours each day in taking care of the patient.

To be eligible for inclusion in the study, the patients had to meet the following criteria: (1) to be between 17 and 40 years old, (2) to have a good understanding of the Greek language, (3) to have been out of hospital for at least 6 weeks and considered stabilised by their treating psychiatrist, (4) to be living with a close relative, and (5) to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) or International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) and with no evidence of organicity, significant intellectual handicap, or primary diagnosis of substance abuse. Inclusion criteria for the caregivers were: (1) to be between 18 and 75 years old, (2) to have a good understanding of the Greek language, (3) to have no diagnosed psychiatric illness, and (4) to be either living with, or directly involved in the care of the patient.

Procedure

Caregivers were interviewed by the first author in individual sessions in the Psychiatric Clinic of the University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece, where participants were asked to take part in a study assessing family functioning of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Caregivers were given an information sheet describing the aims of the study. The time needed to complete the interview was approximately 75–90 min. Patients’ socio-demographic and clinical data were extracted from medical records and confirmed during the interview by the caregivers, whereas patients’ symptoms and functioning were assessed by their treating psychiatrist within 2 weeks from the caregivers’ assessment. All participants involved in the present study provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University Hospital in Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

Measures

Patients’ Measures

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall and Gorham 1962) is a comprehensive 18-item symptom scale, which includes items that address somatic concern, anxiety, emotional withdrawal, conceptual disorganization, guilt feelings, tension, mannerisms and posturing, grandiosity, depressive mood, hostility, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behaviors, motor retardation, uncooperativeness, unusual thought content, blunted affect, excitement, and disorientation. The BPRS is used as part of a clinical interview in which the clinician makes observations among several symptomatic criteria and relies upon patient self-report for other criteria. The BPRS total score is used to assess global symptom change. The scale has been translated and standardized for the Greek population by Paneras and Crawford (2004), and has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient 0.80).

Global Assessment Scale

The Global Assessment Scale (GAS; Endicott et al. 1976) is a rating scale for evaluating the overall functioning of a patient during a specified time period on a continuum from psychological or psychiatric illness to health. The scale ranges from 0 (inadequate information) to 100 (superior functioning). The scale is divided into ten equal intervals: 1–10, 11–20, and so on to 81–90 and 91–100. Particularly, 81–90 and 91–100 mean “positive mental health” (superior functioning, a wide range of interests, social effectiveness, warmth, and integrity); 71–80: with no or only minimal psychopathology; 31–70: outpatients; 1–40: inpatients. The measure is designed for the use of clinicians. The data can be collected from patients, reliable informant, or a case record. The scale has been translated and standardized for the Greek population by Madianos (1987), and has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Intraclass correlation coefficient 0.74).

Caregivers’ Measures

Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales IV Package

Family functioning was assessed by means of the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales IV Package (FACES IV Package; Olson et al. 2007) based on the Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Systems (Olson et al. 1979). The FACES IV Package contains the six scales from FACES IV, as well as the Family Communication Scale (FCS) and the Family Satisfaction Scale (FSS), and includes 62 items in total. The scales are self-report and they can be completed by all family members over the age of 12 years.

The FACES IV (Olson et al. 2007) measures family functioning in terms of cohesion and flexibility. The instrument contains a total of 42 items and displays a six-factor structure of family functioning including two balanced subscales assessing the intermediate range of cohesion and flexibility (Balanced Cohesion and Balanced Flexibility) and four unbalanced subscales assessing the high and low extremes of cohesion and flexibility (Disengaged and Enmeshed for cohesion, Rigid and Chaotic for flexibility). Responses range from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. Higher scores on the balanced scales are indicative of healthier functioning, and the converse holds truth for the unbalanced scales. To determine the amount of balance versus unbalance in a family system, Cohesion, Flexibility, and Total Circumplex ratio scores can be calculated. When each score of the Cohesion and Flexibility ratios is at one and higher, the family system has more balanced levels of cohesion and flexibility. When the Total Circumplex ratio is one or higher, the family system is viewed as more balanced and functional.

Family Communication Scale (FCS) (Olson and Barnes 1996) is a 10-item scale which addresses many of the most important aspects of communication in a family system. Responses range from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree” and a higher score indicates more positive communication.

Family Satisfaction Scale (FSS) is, also, a 10-item scale that assesses the satisfaction of family members in regard to family cohesion, flexibility and communication (Olson 1995). Responses range from 1 “very dissatisfied” to 5 “extremely satisfied” and a higher score on the scale indicates greater satisfaction in family system.

The Greek adaptation of FACES IV Package (Koutra et al. 2013) demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α coefficient ranges from 0.59 to 0.92 for the eight scales) and high test–retest reliability (Intraclass correlation coefficient ranges between 0.94 and 0.98 for the eight scales).

Family Questionnaire

EE was measured via the Family Questionnaire (FQ; Wiedemann et al. 2002). The FQ is a 20-item self-report questionnaire measuring the EE status of relatives of patients with schizophrenia in terms of in terms of emotional overinvolvement (EOI) and critical comments (CC). EOI includes unusually over-intrusive, self-sacrificing, overprotective, or devoted behaviour, exaggerated emotional response, and over-identification with the patient, whereas CC is defined as an unfavourable comment on the behavior or the personality of the person to whom it refers (Leff and Vaughn 1985). The measure consists of 10 items for each subscale. Responses range from 1 “never/very rarely” to 4 “very often” and a higher total score indicates higher EE. The developers provide a cut-off point of 23 as an indication of high CC, and 27 for EOI. The FQ has excellent psychometric properties including a clear factor structure, good internal consistency of subscales and good inter-rater reliability. The FQ has been translated and validated for the Greek population by Koutra et al. (2014a), and has demonstrated good psychometric properties including a clear factor structure, high internal consistency of subscales (Cronbach’s α coefficient 0.90 for CC and 0.82 for EOI) and high test–retest reliability (Intraclass correlation coefficient 0.99 for CC and 0.98 for EOI).

Family Burden Scale

The Family Burden Scale (FBS; Madianos et al. 2004) was used to measure FB. The FBS consists of 23 items. The four FBS dimensions are defined as follows: (A) Impact on daily activities/social life (eight items): defined in terms of burden experienced regarding disruption of daily/social activities; (B) Aggressiveness (four items): captures the presence of episodes of hostility, violence and destruction of property; (C) Impact on health (six items): assesses signs and symptoms of psychopathology reported by the family caregiver; (D) Economic burden (five items): defined in terms of financial problems created by the patient’s illness. Factor A, B, and D items tap objective burden; whereas C items underlie subjective burden. The developers provide a cut-off point of 24 (for the total scale score) to produce the best values of sensitivity and specificity. The scale has been originally developed and standardized in the Greek population and has demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranges from 0.68 to 0.85 for the four FBS dimensions) and test–retest reliability (Pearson’s r correlation coefficient ranges from 0.88 to 0.95).

General Health Questionnaire

The General Health Questionnaire-28 item version (GHQ-28; Goldberg et al. 1997), a self-administered instrument that screens for non-psychotic psychopathology in clinical and non-clinical settings, was used to assess relatives’ psychological distress. Its four subscales measure somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction and severe depression. In the GHQ-28 the respondent is asked to compare his recent psychological state with his usual state on a four-point scale (0-not at all, 1-no more than usual, 2-rather more than usual, 3-much more than usual). In the present study the Likert scoring procedure (0, 1, 2, 3) is applied providing a more acceptable distribution of scores and the total scale score ranges from 0 to 84. Higher scores on the scale are indicative of poorer psychological well-being. The Greek version of GHQ-28, using the Likert response scale, has acceptable psychometric properties (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient 0.90) and a recommended cut-off score of 23/24 for identifying persons at high risk for a psychiatric disorder (Garyfallos et al. 1991).

Potential Confounders

Potential confounders evaluated included caregivers’ and patients’ characteristics that have an established or potential association with patients’ symptoms and overall functioning, as well as with family functioning variables. Caregivers’ characteristics included relative’s age, education (low level ≤9 years of school, medium level ≤12 years of school and >9 years of school, high level: some years in university or university degree), origin (urban vs. rural), family structure (two-parent family vs. one-parent family), and number of family members. Patients’ characteristics included patient’s gender (male vs. female), education (low level ≤9years of school, medium level ≤12 years of school and >9 years of school, high level: some years in university or university degree), working status (working vs. not working), diagnosis (schizophrenia vs. bipolar disorder), chronicity of the illness (FEP vs. chronic patients), and onset of mental illness (≤12 months, 1–4 years, >4 years).

Statistical Analysis

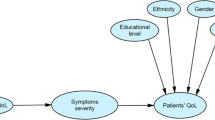

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline characteristics of the participants. The characteristics of FEP patients were compared with those of chronic patients depending on the distribution of the variables: Chi square tests for categorical data, independent sample t tests for the comparison of normally distributed variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple test comparisons. The primary exposures of interest were patient’s symptom severity (BPRS) and psychosocial functioning (GAS) and the main outcome variables were family cohesion and flexibility (FACES IV), EE (FQ), FB (FBS) and caregivers’ psychological well-being (GHQ-28). Multivariable linear regression models were fit to estimate the associations between severity of patient’s symptoms (a per 10 unit increase in BPRS) and functioning (a per 10 unit increase in GAS) and family variables after adjusting for confounders, as well. Potential confounders related with both the outcomes and the exposure of interest in the bivariate associations with a p value <0.2 were included in the multivariable models. Separate multivariable models were built having as an outcome each one of the family measures. Effect modification by illness’s chronicity was evaluated using the likelihood ratio test through inclusion of the interaction terms in the models (statistically significant effect modification if p value <0.05). Estimated associations are described in terms of β-coefficients (beta) and their 95 % confidence intervals (CI). All hypothesis testing was conducted assuming a 0.05 significance level and a two-sided alternative hypothesis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 19 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of family caregivers participated in the study. The sample consisted of 15 males (15.0 %) and 85 females (85.0 %), ranging in age from 28 to 75 years with a mean age of 56.80 years (SD = 9.98). The 64.0 % had finished elementary or high school and the vast majority of the sample (72.0 %) were not currently working. The 82.0 % were living in urban areas and the 63.0 % were married. Finally, the 92.0 % were parents, the 81.0 % were living with the patient, and the 95.0 % had daily contact with the patient. In terms of family structure, the 64.0 % of the families were two-parent families while the 36.0 % were one-parent families.

Patients’ socio-demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 2. The sample consisted of 66 males (66.0 %) and 34 females (34.0 %), ranging in age from 17 to 40 years with a mean age of 31.09 ± 5.75 years (x ± SD). The vast majority of the patients were single (85.0 %), they came from urban areas (91.0 %), and they were living in urban areas (86.0 %). Half of the sample had finished lyceum or had some years in university. The 86.0 % were not working at the time of the assessment, whereas almost half of the sample had no income. As far as diagnosis, 82.0 % had schizophrenia, while 18.0 % had bipolar disorder. The patients had an onset of illness between 15 and 39 years of age with a mean age of 24.03 ± 5.48 years (x ± SD). Half of the patients had an onset of illness at 4 years or longer. The 50.0 % of the sample were FEP (they had one hospitalization) and the 50.0 % were chronic patients (they had two or more hospitalizations). The length of longer hospitalization was up to 20 days for the 65.0 % of the sample, and more than 20 days for the 35.0 %. All patients were under pharmacotherapy, whereas only a limited proportion of patients were additionally under psychotherapy (4.0 %) or underwent a psychosocial rehabilitation programme (2.0 %).

Associations of Patients’ Symptom Severity and Psychosocial Functioning with Socio-demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The two exposure variables, BPRS and GAS, were highly correlated to each other (rho = − 0.79; p < 0.001). In our sample, patient’s symptom severity and overall functioning were significantly related to patient’s gender and chronicity of the illness, indicating more severe symptoms and impaired functioning for males as compared to females, as well as for chronic patients compared to FEP patients. Also, patient’s overall functioning was positively associated with patient’s educational level and working status, indicating that highly educated and working patients were more functional than non-working and less educated patients (Table 2).

Associations Between Symptom Severity with Family Outcomes, Multivariate Analysis

Multivariable analysis adjusted for confounding variables revealed that greater symptom severity, as measured by the BPRS scale, was significantly associated with lower scores in Cohesion Ratio (β coefficient −0.14; 95 % CI −0.26, −0.01), Flexibility Ratio (β coefficient −0.12; 95 % CI −0.22, −0.03), and Total Circumplex Ratio (β coefficient −0.13; 95 % CI −0.23, −0.03) of FACES-IV Package. Regarding caregivers’ EE status, a per 10 unit increase in the BPRS scale was associated with 1.03 units increase in the EOI subscale of the FQ (β coefficient 1.03; 95 % CI 0.02, 2.03). Symptom severity was also associated to both objective and subjective burden (total burden increase 3.01; 95 % CI 1.50, 4.51), as well as caregiver’s psychological distress (total increase in general health index: 3.37; 95 % CI 1.29, 5.45). No significant interaction between BPRS scale and illness’s chronicity was observed (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Associations Between Symptom Patient’s Psychosocial Functioning and Family Outcomes, Multivariate Analysis

Patient’s improved overall functioning was significantly associated with reduced caregiver’s burden (total burden reduction −2.04; 95 % CI −3.55, −0.53). More specifically, a per 10 unit increase in the GAS score was associated with 1.37 and 0.82 unit decrease in objective (β coefficient −1.37; 95 % CI −2.49, −0.24) and subjective (β coefficient −0.82; 95 % CI −1.50, −0.15) burden, respectively. Finally, a per 10 unit increase in the GAS score was related to 0.77 unit decrease in severe depression subscale (β coefficient −0.77; 95 % CI −1.52, −0.03) of the GHQ. No significant interaction between GAS score and illness’s chronicity was observed (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study we investigated how different aspects of family functioning in families of patients with psychosis are associated with illness-related characteristics, such as symptom severity and patient’s psychosocial functioning. Of the two clinical variables investigated in this study, our results demonstrated that symptom severity rather than the functional status of the patient had the most significant impact on family cohesion and flexibility, as well as caregiver’s EE status in terms of EOI, and psychological distress; both symptom severity and patient’s functioning were found to be related to FB, proving a close connection of these two dimensions in the long-term treatment of psychosis. Furthermore, even though chronicity of the illness (FEP vs. chronic patients) was estimated to be the stronger confounder in the relationship between symptom severity, as well as patient’s psychosocial functioning and family outcomes, our findings indicated no significant interaction effect of chronicity in the afore-mentioned associations.

In this paper, we tested the hypothesis that unhealthy family functioning in terms of cohesion and flexibility is associated with patient’s greater severity of illness and impaired psychosocial functioning. Within the Circumplex Model (Olson et al. 1979), cohesion is how systems balance their separateness versus togetherness and flexibility is on how systems balance stability versus change. Our results indicated that as patient’s symptom severity increased family caregivers of either FEP or chronic patients experienced greater unbalanced levels of cohesion and flexibility in the family. In light of this, the family system was viewed as less balanced and functional and thus families experienced higher levels of dysfunction. Since previous research has not investigated this aspect, we found the results interesting as well as reasonable. According to our findings, no significant association of patients’ psychosocial functioning with family cohesion and flexibility was found. Interestingly, contrary to our assumptions, neither symptom severity nor functioning was found to impact family communication, which is considered facilitating of cohesion and flexibility, as well as family satisfaction.

In line with prior research, we hypothesized that the poorer psychiatric status of the patient would be related to higher levels of EE, FB and caregiver’s psychological distress. As far as caregivers’ EE is concerned, our findings indicated that increased symptom severity was linked to elevated levels of caregiver’s EOI. Although previous research on FEP patients has shown no impact of patient’s symptom severity and impaired functioning on either caregivers’ EOI or CC (Heikkila et al. 2002, 2006; Meneghelli et al. 2011; Moller-Leimkuhler 2005; Raune et al. 2004), in the study of King (2000) both EOI and CC were influenced by patient’s total symptom severity and especially by negative symptoms. Furthermore, in a previous Greek study (Mavreas et al. 1992), high EE in the form of EOI was related to both negative and positive symptoms, indicating that high EOI might reflect efforts on the part of the relatives to cope with the difficulties of living with a patient experiencing higher levels of negative symptoms. Our results indicated that high levels of EOI might be a reaction to increased symptom severity, independently of the patient being either in the early stages of the illness or later on. EOI has been found to be a dominant cultural feature of the behavior of Greek families (Mavreas et al. 1992). Thus, the more ill the patient, the more likely the caregivers would express their concern in terms of over-concern and protection (which in exaggerated form becomes EOI), rather than irritation, dislike or disapproval of the patient’s behavior.

We, also, found that increased symptomatology and a low functional level of either FEP or chronic patients contributes to greater burden for their caregivers. Earlier studies on FEP (Tennakoon et al. 2000; Wolthaus et al. 2002) or chronic patients (Grandon et al. 2008; Hjarthag et al. 2010; Hou et al. 2008; Lowyck et al. 2004; Perlick et al. 2006; Provencher and Mueser 1997; Roick et al. 2006; Schene et al. 1998; Tang et al. 2008) point in the same direction. There are multiple perspectives leading to an understanding of the similarity of FEP and chronic patients’ caregivers regarding their burden status. Psychotic symptoms are associated with impaired everyday functioning which may impact on the patient’s behavior and capacity to carry out daily activities. Impaired competence and efficiency results in the patient’s dependence on caregiver, thus increasing the level of his/her burden. In addition, the limited resources in community care in Greece makes the already difficult task of caregiving even more of a struggle. The lack of professional help, i.e. psychosocial rehabilitation groups, as well as inadequate family psychoeducation/support, may heighten caregivers’ worries and often places the onus of care and monitoring solely on them. This may lead to a more intrusive manner of engaging with the patient resulting in vicious cycle of greater burden for all. Furthermore, due to the difficult economic conditions in Greece, there are limited opportunities for mental health patients to work on a regular basis or in subsidized employment. In our study, the 86 % of the patients were not working. As a result, the majority of the patients spend most of the day and nearly every day confined home, whereas few of them receive public welfare benefits.

Finally, a strong association between symptom severity and caregivers’ psychological distress was found indicating that the more severe the patient’s symptoms the greater the distress for family caregivers. Although earlier research on FEP patients has shown no links between patient’s symptomatology and caregivers’ psychological distress (Addington et al. 2003; McCleery et al. 2007), this association proved remarkably robust in chronic patients (Mitsonis et al. 2012; Winefield and Harvey 1993). Finally, while patient’s level of functioning appeared to be unrelated to general health index of GHQ indicating no impact on caregivers’ psychological distress in our study, it was significantly associated with a specific domain of distress, i.e. severe depression in caregivers of patients with psychosis.

In our sample, a significant negative correlation between patient’s psychosocial functioning and symptom severity was found, similarly with previous findings (Schaub et al. 2011). Furthermore, consistently with the existing literature, symptom severity and functioning were significantly related to patient’s gender, educational level, working status, and chronicity of the illness. Male patients were found to experience more severe symptoms (especially negative symptoms) than female ones (Cowell et al. 1996; Gur et al. 1996; Shtasel et al. 1992), whereas females were found to have a milder range of interpersonal problems and are characterized by better social functioning than males (Hass and Garratt 1998; Sorgaard et al. 2001). This can be attributed to the later illness’s onset and the development of family dynamics (Sorgaard et al. 2001), i.e. women are more likely to have been married, to be able to live independently, and to be employed, despite having similar symptom profiles with men (Andia et al. 1995). Also, patient’s education and working status have been shown to be predictive of functional outcome, as non-working patients show significantly worse functional outcomes (Hoffmann et al. 2003; Honkonen et al. 2007; Schennach-Wolff et al. 2009). Finally, research suggests that patients with longer overall illness duration appeared to have less favourable functional outcomes (Haro et al. 2008; Schennach-Wolff et al. 2009).

The strengths of the present study include its large sample size, the assessment of various aspects of family functioning by using standardized tools and the high participation rate (96.1 %). Furthermore, patients who participated in the present study constitute a rather homogenous group, since they all live in a specific region in Crete, and are treated in the same department where similar therapeutic interventions take place. It should be noted that the Inpatient Psychiatric Unit of the University Hospital of Heraklion is the only public facility in the East part of the island of Crete, covering a population of about 400.000 residents. Moreover, the inclusion of two groups of patients (FEP and chronic) for comparison allowed us to eliminate and isolate confounding variables and bias. Furthermore, all assessments were performed during a specific post-hospitalization time period (patients had to have been out of hospital for at least 6 weeks). This selection criterion represents strength in our study, since it allows for some control of functioning difficulties related to adjustment to a recent diagnosis for FEP patients or a recent relapse for chronic patients.

However, there are several limitations in the present study that deserve acknowledgement. First, the population of patients and caregivers were from one catchment area and hence, generalizability may be limited. Future research should include larger and representative samples and data from different diagnostic groups. Second, due to its cross-sectional design, our study limits the direct inference of causation. Although difficult to conduct, longitudinal investigations of family functioning are needed to examine the mechanisms and mediators leading to the development of unhealthy family functioning. A third limitation is the definition of “FEP” and “chronic” patients. Even though the duration of illness was also taken into consideration, chronicity defined by the number of hospitalizations has some limitations because the number of hospitalizations may be influenced by social factors and by the level of psychiatric health care system. (i.e. some patients may have an episode of psychosis before their first admission to hospital while others may have been admitted to hospital with a non-psychotic disorder before they later develop their FEP). Also, psychosis illness length was based on number of admissions rather than days/weeks, which is a much more accurate measurement to compare FEP versus chronic patients early with later course psychosis patients (i.e. as in the study of Onwumere et al. 2008). On the other hand, the criterion of admission is a definite nondisputable event, whereas onset of illness based on history of symptoms is subject to recall bias, ambiguous assessment and documentation of the symptomatology, etc. In addition, although the inclusion of patients whose symptoms had been stable for at least 6 weeks is reasonable to test association of symptoms with family functioning dimensions, this would not test one feature of symptoms, namely unpredictability, which has been found to associate with EE in one study (MacCarthy et al. 1986). Moreover, the use of the FQ to assess EE may limit the validity of the analysis because the FQ does not measure hostility and may miss some high-EE cases; however, the Camberwell Family Interview (Vaughn and Leff 1976) is very labour intensive. In addition, the exclusion of caregivers with a history of psychiatric disorder might limit the generalizability of the findings, as previous research has shown that many caregivers suffer from anxiety or depression and a small percentage will have psychosis themselves. Furthermore, another possible limitation is that the interaction effect of chronicity was examined using a variable that compares FEP (one hospitalization) with chronic patients (two or more hospitalizations). Finally, the capping of patients at age 40 might weaken the testing of chronicity; however, including older patients might have led to groups with large differences in terms of age and family structure that would have made the comparisons problematic.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our study serves as an important step toward recognizing the association of specific illness-related variables with family functioning in psychosis. Clarification of the relationship between the psychiatric status of the patient and the family environment is necessary in that understanding how psychiatric symptoms impact family interactions from the early stages of the illness could inform the development of more effective psychosocial interventions for both patients and their families. The results of our study are taken as an indication that dysfunctional levels of family cohesion and flexibility, high levels of caregivers’ EOI and psychological distress can be primarily tied to patient’s increased symptom severity, whereas both symptom severity and patient functioning were found to be important contributing factors that impact caregivers’ burden. Chronicity of the illness does not appear to be a moderating factor in the afore-mentioned relationships. Given that many influences on the caregivers were not measured within the context of the present study, such as a variety of cognitive influences (Kuipers et al. 2010), it would be more accurate to mention that illness-related characteristics, such as symptom severity and patient’s psychosocial functioning, might be one important influence on specific aspects of family functioning in psychosis from the early stages of the illness and later on.

These findings indicate that psychoeducational interventions from the early stages of the illness should focus on both the patient and his/her family aiming not only at reducing symptoms but also maximizing patient’s psychosocial functioning, thus contributing to ameliorating family’s level of dysfunction. A large number of positive effects of psychoeducation have been reported in patients with psychotic disorders, including high reductions in relapse and rehospitalization rates, better treatment adherence and improvement in psychosocial functioning (Cassidy et al. 2001; Dixon et al. 2001; Falloon 2003; McWilliams et al. 2010; Murray-Swank and Dixon 2004; Pekkala and Merinder 2002; Pharoah et al. 2010). Taking into serious consideration that patients who have achieved a lower symptom level and a better level of functioning seemed to live in less stressful family environments, we suggest that family dysfunction can be reduced by developing understandings of family dynamics and functioning. This entails that family psychoeducational interventions should be considered aiming at improving dysfunctional family interactions and thus minimizing disruption to family life (Kuipers et al. 2002; Pharoah et al. 2010).

References

Addington, J., Coldham, E. L., Jones, B., Ko, T., & Addington, D. (2003). The first episode of psychosis: The experience of relatives. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 108(4), 285–289.

Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Priede, A., Hetrick, S. E., Bendall, S., Killackey, E., Parker, A. G., et al. (2012). Risk factors for relapse following treatment for first episode psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Schizophrenia Research, 139(1–3), 116–128.

Andia, A. M., Zisook, S., Heaton, R. K., Hesselink, J., Jernigan, T., Kuck, J., et al. (1995). Gender differences in schizophrenia. The Journal of Nervous Mental Disease, 183(8), 522–528.

Ballon, J. S., Kaur, T., Marks, I. I., & Cadenhead, K. S. (2007). Social functioning in young people at risk for schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 151(1–2), 29–35.

Basta, M., Stefanakis, Z., Panierakis, C., Michalas, N., Zografaki, A., Tsougkou, M., et al. (2013). Deinstitutionalization and family burden following the psychiatric reform. European Psychiatry, 28(Suppl 1), 1.

Birchwood, M., & Macmillan, F. (1993). Early intervention in schizophrenia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 27(3), 374–378.

Butzlaff, R. L., & Hooley, J. M. (1998). Expressed emotion and psychiatric relapse: A meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55(6), 547–552.

Cassidy, E., Hill, S., & O’Callaghan, E. (2001). Efficacy of a psychoeducational intervention in improving relatives’ knowledge about schizophrenia and reducing rehospitalisation. European Psychiatry, 16(8), 446–450.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cowell, P. E., Kostianovsky, D. J., Gur, R. C., Turetsky, B. I., & Gur, R. E. (1996). Sex differences in neuroanatomical and clinical correlations in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(6), 799–805.

Dixon, L., McFarlane, W. R., Lefley, H., Lucksted, A., Cohen, M., Falloon, I., et al. (2001). Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services, 52(7), 903–910.

Endicott, J., Spitzer, R. L., Fleiss, J. L., & Cohen, J. (1976). The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry, 33(6), 766–771.

Falloon, I. R. (2003). Family interventions for mental disorders: Efficacy and effectiveness. World Psychiatry, 2(1), 20–28.

Garyfallos, G., Karastergiou, A., Adamopoulou, A., Moutzoukis, C., Alagiozidou, E., Mala, D., et al. (1991). Greek version of the General Health Questionnaire: Accuracy of translation and validity. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 84(4), 371–378.

Georgas, J. (1999). Family as a context variable in cross-cultural psychology. In J. Adamopoulos & Y. Kashima (Eds.), Social psychology and cultural context (pp. 163–175). Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Georgas, J. (2000). Psychodynamic of family in Greece: Similarities and differences with other countries. In A. Kalatzi-Azizi & E. Besevegis (Eds.), Issues of training and sensitization of workers in centers for mental health of children and adolescents (pp. 231–251). Athens: Ellinika Grammata.

Goldberg, D. P., Gater, R., Sartorius, N., Ustun, T. B., Piccinelli, M., Gureje, O., et al. (1997). The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 191–197.

Grandon, P., Jenaro, C., & Lemos, S. (2008). Primary caregivers of schizophrenia outpatients: Burden and predictor variables. Psychiatry Research, 158(3), 335–343.

Green, M. F., Kern, R. S., Braff, D. L., & Mintz, J. (2000). Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: Are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 26(1), 119–136.

Gur, R. E., Petty, R. G., Turetsky, B. I., & Gur, R. C. (1996). Schizophrenia throughout life: Sex differences in severity and profile of symptoms. Schizophrenia Research, 21(1), 1–12.

Haro, J. M., Novick, D., Suarez, D., Ochoa, S., & Roca, M. (2008). Predictors of the course of illness in outpatients with schizophrenia: A prospective three year study. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 32(5), 1287–1292.

Hass, G. L., & Garratt, L. S. (1998). Gender differences in social functioning. In K. T. Mueser & N. Tarrier (Eds.), Handbook of social functioning in schizophrenia (pp. 149–180). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Heikkila, J., Ilonen, T., Karlsson, H., Taiminen, T., Lauerma, H., Leinonen, K. M., et al. (2006). Cognitive functioning and expressed emotion among patients with first-episode severe psychiatric disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 47(2), 152–158.

Heikkila, J., Karlsson, H., Taiminen, T., Lauerma, H., Ilonen, T., Leinonen, K. M., et al. (2002). Expressed emotion is not associated with disorder severity in first-episode mental disorder. Psychiatry Research, 111(2–3), 155–165.

Hjarthag, F., Helldin, L., Karilampi, U., & Norlander, T. (2010). Illness-related components for the family burden of relatives to patients with psychotic illness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(2), 275–283.

Hoffmann, H., Kupper, Z., Zbinden, M., & Hirsbrunner, H. P. (2003). Predicting vocational functioning and outcome in schizophrenia outpatients attending a vocational rehabilitation program. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38(2), 76–82.

Honkonen, T., Stengard, E., Virtanen, M., & Salokangas, R. K. (2007). Employment predictors for discharged schizophrenia patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(5), 372–380.

Hooley, J. M. (2000). Social factors in schizophrenia. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(4), 238–242.

Hooley, J. M., & Hiller, J. B. (2000). Personality and expressed emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(1), 40–44.

Hou, S. Y., Ke, C. L., Su, Y. C., Lung, F. W., & Huang, C. J. (2008). Exploring the burden of the primary family caregivers of schizophrenia patients in Taiwan. Psychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences Journal, 62(5), 508–514.

Katakis, C. (1998). The three identities of the Greek family. Athens: Ellinika Grammata.

King, S. (2000). Is expressed emotion cause or effect in the mothers of schizophrenic young adults? Schizophrenia Research, 45(1–2), 65–78.

Koukia, E., & Madianos, M. G. (2005). Is psychosocial rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients preventing family burden? A comparative study. Journal of Psychiatry & Mental Health Nursing, 12(4), 415–422.

Koutra, K., Economou, M., Triliva, S., Roumeliotaki, T., Lionis, C., & Vgontzas, A. N. (2014a). Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Greek version of the Family Questionnaire for assessing expressed emotion. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(4), 1038–1049.

Koutra, K., Triliva, S., Roumeliotaki, T., Lionis, C., & Vgontzas, A. (2013). Cross-Cultural adaptation and validation of the Greek version of the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales IV Package (FACES IV Package). Journal of Family Issues, 34(12), 1647–1672.

Koutra, K., Triliva, S., Roumeliotaki, T., Stefanakis, Z., Basta, M., Lionis, C., et al. (2014b). Family functioning in families of first-episode psychosis patients as compared to chronic mentally ill patients and healthy controls. Psychiatry Research, 219(3), 486–496.

Koutra, K., Vgontzas, A. N., Lionis, C., & Triliva, S. (2014c). Family functioning in first-episode psychosis: A systematic review of the literature. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49, 1023–1036.

Kuipers, E., Lam, D., & Leff, J. (2002). Family work for schizophrenia: A practical guide. London: Gaskell Press.

Kuipers, E., Onwumere, J., & Bebbington, P. (2010). Cognitive model of caregiving in psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 196(4), 259–265.

Leff, J., & Vaughn, C. (1985). Expressed emotion in families: Its significance for mental illness. New York: Guilford Press.

Lowyck, B., De Hert, M., Peeters, E., Wampers, M., Gilis, P., & Peuskens, J. (2004). A study of the family burden of 150 family members of schizophrenic patients. European Psychiatry, 19(7), 395–401.

MacCarthy, B., Hemsley, D. R., Shrank-Fernandez, C., Kuipers, L., & Katz, R. (1986). Unpredictability as a correlate of expressed emotion in the relatives of schizophrenics. British Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 727–731.

Madianos, M. (1987). Global Assessment Scale: Reliability and validity of the Greek scale (in greek). Encephalos, 24, 97–100. [in Greek].

Madianos, M., Economou, M., Dafni, O., Koukia, E., Palli, A., & Rogakou, E. (2004). Family disruption, economic hardship and psychological distress in schizophrenia: Can they be measured? European Psychiatry, 19(7), 408–414.

Madianos, M. G., Economou, M., Hatjiandreou, M., Papageorgiou, A., & Rogakou, E. (1999). Changes in public attitudes towards mental illness in the Athens area (1979/1980–1994). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 99(1), 73–78.

Madianos, M., Papaghelis, M., Filippakis, A., Hatjiandreou, M., & Papageorgiou, A. (1997). The reliability of SCID I in Greece in clinical and general population. Psychiatriki, 8, 101–108. [in Greek].

Mavreas, V. G., Tomaras, V., Karydi, V., Economou, M., & Stefanis, C. N. (1992). Expressed Emotion in families of chronic schizophrenics and its association with clinical measures. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 27(1), 4–9.

McCleery, A., Addington, J., & Addington, D. (2007). Family assessment in early psychosis. Psychiatry Research, 152(2–3), 95–102.

McWilliams, S., Egan, P., Jackson, D., Renwick, L., Foley, S., Behan, C., et al. (2010). Caregiver psychoeducation for first-episode psychosis. European Psychiatry, 25(1), 33–38.

Meneghelli, A., Alpi, A., Pafumi, N., Patelli, G., Preti, A., & Cocchi, A. (2011). Expressed emotion in first-episode schizophrenia and in ultra high-risk patients: Results from the Programma 2000 (Milan, Italy). Psychiatry Research, 189(3), 331–338.

Mitsonis, C., Voussoura, E., Dimopoulos, N., Psarra, V., Kararizou, E., Latzouraki, E., et al. (2012). Factors associated with caregiver psychological distress in chronic schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(2), 331–337.

Mo, F. Y. M., Chung, W. S., Wong, S. W., Chun, D. Y. Y., & Wong, K. S. (2008). Expressed emotion in relatives of Chinese patients with first-episode psychosis in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry, 17(2), 38–44.

Moller-Leimkuhler, A. M. (2005). Burden of relatives and predictors of burden. Baseline results from the Munich 5-year-follow-up study on relatives of first hospitalized patients with schizophrenia or depression. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 255(4), 223–231.

Murray-Swank, A. B., & Dixon, L. (2004). Family psychoeducation as an evidence-based practice. CNS Spectrum, 9(12), 905–912.

Olson, D. H. (1995). Family Satisfaction Scale. Minneapolis, MN: Life Innovations.

Olson, D. H., & Barnes, H. (1996). Family Communication Scale. St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota.

Olson, D. H., Gorall, D. M., & Tiesel, J. W. (2007). FACES IV manual. Mineapolis, MN: Life Innovations.

Olson, D. H., Sprenkle, D. H., & Russell, C. (1979). Circumplex Model of marital and family systems: I. Cohesion and adaptability dimensions, family types, and clinical applications. Family Process, 18(1), 3–28.

Onwumere, J., Kuipers, E., Bebbington, P., Dunn, G., Fowler, D., Freeman, D., et al. (2008). Caregiving and illness beliefs in the course of psychotic illness. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 53(7), 460–468.

Overall, J. E., & Gorham, D. R. (1962). The brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Report, 10, 799–812.

Paneras, A., & Crawford, J. R. (2004). The use of the brief Psychiatric Rating Scale in Greek psychiatric patients. Scientific Annals of the Psychological Society of Northern Greece, 2, 183–201. [in Greek].

Papadiotis, V., & Softas-Nall, L. (2006). Family systemic therapy: Basic approaches, theoretical positions and practical applications. Athens: Ellinika Grammata. [in Greek].

Pekkala, E., & Merinder, L. (2002). Psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database System Review, 2, CD002831.

Perlick, D. A., Rosenheck, R. A., Kaczynski, R., Swartz, M. S., Canive, J. M., & Lieberman, J. A. (2006). Components and correlates of family burden in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 57(8), 1117–1125.

Pharoah, F., Mari, J., Rathbone, J., & Wong, W. (2010). Family intervention for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database System Review, 12, CD000088.

Provencher, H. L., & Mueser, K. T. (1997). Positive and negative symptom behaviors and caregiver burden in the relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 26(1), 71–80.

Raune, D., Kuipers, E., & Bebbington, P. E. (2004). Expressed emotion at first-episode psychosis: Investigating a carer appraisal model. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184, 321–326.

Roick, C., Heider, D., Bebbington, P., Angermeyer, M., Azorin, J., Brugha, T., et al. (2007). Burden on caregivers of people with schizophrenia: comparison between Germany and Britain. British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 333–338.

Roick, C., Heider, D., Toumi, M., & Angermeyer, M. (2006). The impact of caregivers’ characteristics, patients’ conditions and regional differences on family burden in schizophrenia: A longitudinal analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 114(5), 363–374.

Schaub, D., Brune, M., Jaspen, E., Pajonk, F.-G., Bierhoff, H.-W., & Juckel, G. (2011). The illness and everyday living: Close interplay of psychopathological syndromes and psychosocial functioning in chronic schizophrenia. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 261, 85–93.

Schene, A. H., van Wijngaarden, B., & Koeter, M. W. (1998). Family caregiving in schizophrenia: Domains and distress. Schizophrenia Buletinl, 24(4), 609–618.

Schennach-Wolff, R., Jager, M., Seemuller, F., Obermeier, M., Messer, T., Laux, G., et al. (2009). Defining and predicting functional outcome in schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Research, 113(2–3), 210–217.

Shtasel, D. L., Gur, R. E., Gallacher, F., Heimberg, C., & Gur, R. C. (1992). Gender differences in the clinical expression of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 7(3), 225–231.

Softas-Nall, B. (2003). Reflections of forty years of family therapy, research and systemic thinking in Greece. In K. Ng (Ed.), Global perspectives in family therapy: Development, practice, and trends (pp. 125–146). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Sorgaard, K. W., Hansson, L., Heikkila, J., Vinding, H. R., Bjarnason, O., Bengtsson-Tops, A., et al. (2001). Predictors of social relations in persons with schizophrenia living in the community: A Nordic multicentre study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 36(1), 13–19.

Tang, V. W., Leung, S. K., & Lam, L. C. (2008). Clinical correlates of the caregiving experience for Chinese caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(9), 720–726.

Tennakoon, L., Fannon, D., Doku, V., O’Ceallaigh, S., Soni, W., Santamaria, M., et al. (2000). Experience of caregiving: Relatives of people experiencing a first episode of psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 529–533.

Vaughn, C., & Leff, J. (1976). The measurement of expressed emotion in the families of psychiatric patients. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 15(2), 157–165.

Wiedemann, G., Rayki, O., Feinstein, E., & Hahlweg, K. (2002). The Family Questionnaire: Development and validation of a new self-report scale for assessing expressed emotion. Psychiatry Research, 109(3), 265–279.

Winefield, H. R., & Harvey, E. J. (1993). Determinants of psychological distress in relatives of people with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 19(3), 619–625.

Wolthaus, J. E., Dingemans, P. M., Schene, A. H., Linszen, D. H., Wiersma, D., Van Den Bosch, R. J., et al. (2002). Caregiver burden in recent-onset schizophrenia and spectrum disorders: The influence of symptoms and personality traits. Journal of Nervous Mental Disease, 190(4), 241–247.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all patients and their caregivers participated in the present study. Special thanks to the psychiatrists and the whole staff of the Psychiatric Clinic of the University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece for their contribution and understanding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koutra, K., Triliva, S., Roumeliotaki, T. et al. Family Functioning in First-Episode and Chronic Psychosis: The Role of Patient’s Symptom Severity and Psychosocial Functioning. Community Ment Health J 52, 710–723 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9916-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9916-y