Abstract

Couple and family relationships are central in processes of substance use and gambling disorders, yet they remain inadequately researched and marginally addressed in services found in the health system. Multiple barriers exist that favour a focus on the individual due to organization structure and discourse, shortage of couple therapy training, and values and philosophy of addiction services. This article describes a successful strategic initiative to foster a partnership for researchers and health system decision-makers to promote a health system change. We identify impactful factors in a two-day integrated knowledge translation workshop bringing together practitioners, researchers, decision-makers and couples seeking services for gambling and substance use disorders. The initiative shifted awareness of decision-makers, built a network of collaborative relationships and created a consensus for action among stakeholders. This early integrated knowledge translation strategy opened up research partnership on a couple therapy randomized trial in the health system, training for counselors, and research opportunities for graduate students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Couple relationships are central to the development and outcomes in addictive processes (Lee 2014, 2015; Rodriguez et al. 2014), yet they remain inadequately researched and marginally addressed in services offered for substance-use disorders (SUD) (Selbekk et al. 2018; Simmons and McMahon 2012) and gambling disorders (GD). Gambling research has shown that couple conflict and problem gambling form mutually escalating recursive cycles (Lee 2014). Complex family and relational dynamics exacerbate the strain experienced by problem gambling individuals and their partners (Cheung 2015) as well as problem alcohol users (Rodriguez et al. 2014). Studies in substance use indicate that couple partners influence each other’s behaviors, shown in a preponderance of partnered substance use in heavy episodic drinking (Mushquash et al. 2013), use of opioid and cocaine (Simmons and Singer 2006), and severe alcohol use (Lee et al. 2017). Further, relational stressors and ignored couple issues are a leading factor in relapse (Fals-Stewart et al. 2005). Couples constitute the primary executive and parental unit in the family system, and directly impact children (Leonard and Eiden 2007), hence warrant being treated as a critical unit in interventions (Lee 2009). Marriage and family therapists can play a crucial role in stepping up couple-based services and contribute to advancing our knowledge in this important but neglected area in the addiction field. Addiction services are missing the mark when the relationship context is overlooked, and the complex interplay of addiction and intimate relationships remains poorly understood. This article describes a successful strategic initiative to build a partnership for researchers and health system decision-makers to open up avenues for research in couple therapy services for SUD and GD.

Barriers to Change

A provincial report released on publicly funded addiction and mental health services highlighted the lack of services and supports for families and counseling from a family system perspective, one that does not simply focus on the individual as separate from the family (Wild et al. 2014). However, an interlocking chain of barriers stand in the way. This includes a dominant institutional discourse emphasizing addiction as an individual medical and psychological problem instead of a relational one (Selbekk and Sagvaag 2016). Staff beliefs, management concerns of cost effectiveness, dictates of tradition, and a shortage of counselors trained to work with couples pose further barriers. Addiction treatment programs in many countries are organized to prioritize individual and group formats intended to change individuals’ thoughts and behavior (Tolchard 2017). Without a better understanding of couple dynamics in addiction, it is easy to subscribe to the view that couple interaction is a threat to recovery and hence partners should be treated separately (Simmons and Singer 2006). Yet evidence indicates that working with the couple unit reduces substance use more than individual counseling, and augments family functioning, including decreasing intimate partner violence and improving children’s psychosocial adjustment (Fals-Stewart et al. 2004). Couple therapy was found to be effective and beneficial to problem gamblers and their spouses (Lee and Rovers 2008; Lee and Awosoga 2014), and was experienced more positively than individual counseling (Tremblay et al. 2018).

Changing the Health System

Health system services tend to perpetuate the status quo rather than be responsive to client needs and research evidence. Working in silos, researchers, decision-makers, counselors and clients hold differing vantage points and goals that can prevent a comprehensive understanding of issues (Disis and Slattery 2010) and impede the progress of research and treatment (Gagliardi et al. 2016). The concerted effort and unified vision of stakeholders from different sectors are needed to mobilize health system change. Compounding these obstacles for partnerships and collaboration are a shortage of funding and time to hold meetings, failure of support from administrators, and existing infrastructures that cannot accommodate research as an additional demand on personnel and work routines (Ellen et al. 2013). Even when new evidence for interventions is available, poor understanding about effective research transfer methods can obstruct implementation of practice to improve services (Lang et al. 2007).

We describe a strategic initiative to raise the awareness of provincial health system decision-makers and to enlist their partnership with researchers to address the couple treatment and research gap in addiction and mental health services. This case example is offered to aid change-makers wishing to make inroads into complex health systems to develop evidence-based knowledge that would benefit those seeking couple therapy in addiction services.

Integrated Knowledge Translation

This premise of integrated knowledge translation (IKT) informs this strategic initiative. Knowledge translation refers to the process of bridging what we know and what we do through the interaction of researchers and knowledge users. Knowledge translation (KT) usually refers to end-of-study KT of applying results from research to practice, generally originating from researchers (Goldner et al. 2014). In contrast, IKT emphasizes starting the process of building research partnerships and creating knowledge together from the inception of a project (Graham et al. 2018). Such partnerships help to identify pressing issues with multiple stakeholders’ input on health problems and encourage joint solutions (Lencucha et al. 2010). When context and health system actors are absent in efficacy studies conducted in an ideal setting, the results do not necessarily translate into effectiveness in the real world (Marchand et al. 2011). We are seeing an increasing move away from efficacy studies in controlled settings to effectiveness or pragmatic studies to learn how an intervention works in a practice context (Zwarentstein and Treweek 2009). IKT can facilitate contextualized effectiveness research, active collaboration between researchers and users of knowledge throughout the entire research process (Kothari and Wathen 2013).

Canada’s health research funding programs have acknowledged the challenges of KT in grants to aid the formation of meaningful partnerships between researchers and service-providers. Such funding supports the premise of IKT in that “involving knowledge users as equal partners alongside researchers will lead to research that is more relevant to, and more likely to be useful to, the knowledge users” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research 2012, p. 2).

Methods

Structure of the IKT Initiative

An IKT workshop was held to bring together health system stakeholders for a 2-day meeting on relational issues in addiction and mental health treatment. A variety of modalities was used to promote the sharing of ideas, values, practices, research evidence, organizational culture and questions. The agenda of activities for the two days is outlined as follows:

Day 1:

-

The facilitator (contracted) used an ice-breaker activity to elicit 3 keywords to capture each participant’s view of the current state of relational and couple counseling in addiction services in the health system.

-

Using a case study, we elicited the participants’ implicit existing beliefs, concepts and frameworks, and current intervention practices in addiction treatment.

-

The workshop lead (first author) presented a PowerPoint lecture with a review of the literature of research evidence including the cost effectiveness of couple therapy (Crane et al. 2013; Morgan and Crane 2010; Morgan et al. 2013) and how relationship issues impact treatment engagement, retention, outcomes and relapse.

-

Treatment-providers illustrated on large newsprint the structure and pathway of how addiction clients move through the health services system, noting where the relational unit was addressed, if at all.

-

Treatment-providers discussed the type of outcomes data they collected for their services, how data were collected and what they considered to be successes and gaps in addiction treatment in the health services system.

-

The workshop lead presented research evidence and training outcomes on a model of systemic evidence-based couple therapy, with input from addiction counselors trained and familiar in this approach from other provinces.

-

GD couples shared their frustrated experience for services within the health system, and their experience with couple therapy in a completed research study.

-

Participants’ provided feedback on a survey for Day 1 and their expectations for Day 2.

-

Workshop participants networked at a dinner and built relationships in a relaxed atmosphere.

Day 2:

-

Participants brainstormed and used visualization to identify priorities for action, and indicated their interest on research topics that can enhance the use of relational counseling in services.

-

Participants assessed current health system change readiness, applicability and transferability of evidence, and likelihood of success.

-

Small group work was used to determine participants’ interests in furthering priorities to advance relational counseling in addiction services.

-

Participants rank-ordered system changes needed for incorporation of relational treatment for addictions.

-

One researcher familiar with the research environment helped the group to identify provincial and national funding sources.

-

Working teams were formed around identified priorities to move forward.

-

The co-lead of the workshop (second author) and a doctoral Research Assistant led the evaluation of the workshop with the surveys and focus groups.

-

The lead of the workshop brought the workshop to an energetic close with a ritual using music, movement and a game.

In sum, the workshop intentionally used multiple modalities for its activities: cognitive engagement through formal lectures, experiential engagement of participants, small and large group work and formal/ informal interactions which will be elaborated in the results.

Participants

The workshop lead invited stakeholders from past addiction-related conferences and meetings who expressed concerns about relationship issues and gaps in couple and family engagement in addiction services. Ideas and concerns were expressed at round-table discussions and conversations at these earlier meetings. All invitees agreed to participate in the workshop, in total 20 individuals. Among them were decision-makers (directors, managers, clinical supervisors, research and evaluation leads) from addiction and mental health services in the province health system (n = 9), researchers (n = 7) from four universities across Canada, previous research collaborators (n = 2), and doctoral students (n = 2). Three clients were invited as guests to share their experience in seeking couple therapy for their own or their partner’s addiction. An external facilitator was contracted to facilitate the workshop.

Ethics

The institutional research ethics officer was consulted and an ethics application for the evaluation of this workshop was not deemed necessary. However, written consent and permission were obtained from all workshop participants to use quotes from the proceedings of the workshop and their evaluations for reports and publications.

Data Collection and Analysis

Participant Surveys and Focus Groups

Workshop evaluation was conducted at two points. At the end of Day 1, a process survey was used to gauge what participants found “most helpful” and “least helpful” to determine if any changes were needed for the next day. At the end of Day 2, a summative survey was used to determine if participants felt the workshop met its stated objectives (Table 1), with the use of a Likert scale and two open-ended questions. The Day 2 survey was immediately followed by two concurrent focus groups of 30-minute duration each where questions in the survey could be explored in greater depth. Quantitative data were analyzed with SPSS version 22. Descriptive output with mean and median for the surveys were calculated.

Focus groups were conducted by a doctoral trainee and the co-lead using the same set of questions, audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. The workshop lead exempted herself to allow participants to voice their reactions to the workshop freely. The data were coded into meaning units and analyzed inductively (Braun and Clarke 2013). The coded units were organized into themes to reflect participants’ feedback. The transcripts were analyzed by two members of the team to ensure accuracy and reliability of coding and interpretation.

The mixed methods evaluation on Day 2 was designed to evaluate three key domains: (1) the effectiveness of the knowledge translation and planning workshop in achieving its aim to create partnership for action in addressing the couple relationship in addiction treatment; (2) whether the workshop enhanced participants’ understanding of the value of couple counseling as part of addiction treatment and their awareness of current gaps in practice and research; (3) the components of the planning workshop that most contributed to knowledge translation and partnership building. Focus group questions were: (1) What stood out for you the most these two days? (2) Prior to the workshop, what were your thoughts about involving family members as an interactive unit in addiction and mental health treatment? Has that perspective changed? How? What convinced you differently? (3) What might be some obstacles preventing you or your agency in working with couple and families interactively with the addicted individual? (4) What worked well/less well at this workshop with inter-sectoral stakeholders? (5) What top two research priorities would you be interested in pursuing?

Results

Surveys

Two surveys were developed by members of the team, hence the Likert scales scoring scale was different. Completion rate of both surveys was 84% (n = 16).

End of Day 1 Survey Results

Overall the participants rated their Day 1 experience as “highly satisfied” (Mean = 6.01; Median = 6 on a 7-point Likert scale where 7 = highly satisfied). In response to the feedback, minor modifications were made to the Day 2 agenda to provide time to discuss participants’ desired topics, such as couple therapy models and outcome measures.

End of Day 2 Workshop Survey Results

Using a Likert scale (5 = “strongly agree” and 1 = “strongly disagree”), 16 participants assessed the workshop effectiveness across eight categories (Table 1), with a mean rating 4.66, and a median of 5. We missed four surveys because three participants left early due to other commitments, another participant joined remotely from a different province and did not fill out the survey. Those who filled out the survey found the workshop to be highly effective in achieving its goals with particular success in fostering the exchange of ideas among practitioners, decision-makers and researchers. The workshop was found to be effective in enhancing understanding of couple and family treatment in addictions, exploration of concepts of couple therapy, and identification of research issues and opportunities. In addition, open-ended questions reflected participants’ desire to learn more about models of couple therapy (n = 3 comments). “Most useful” aspects (n = 12 comments) of the workshop were the opportunity to connect with others in the field, sharing and developing ideas for advancing services and research in the field of couple therapy. Participants felt that the inclusion of clients’ perspectives on the impact of couple therapy on addiction was highly instructive.

End of Workshop Focus Group Themes

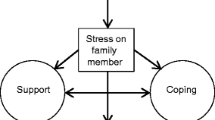

Two focus groups, each with equal numbers of participants (n = 8 participants per group) and equal representation from the three sectors participated in the end of workshop focus groups. Analysis of focus group transcripts led to the identification of two main themes: (1) new awareness, and (2) critical workshop components (Fig. 1).

New Awareness

Discrepancy Between Knowledge, Evidence and Practice

Treatment-providers and managers often do not have the time to delve into the research literature and interpret it. In their professional culture, they have more pressing tasks of managing the organization and workforce and serving the clients. Hence, it is easy for the status-quo to be maintained in the field. To overcome this knowledge to practice gap, participants found partnership-building workshops like the one described here to be especially important, and what they felt should happen on a more regular basis:

How we actually take from the research to something that is implementable and meaningful at the front lines; …a lot of that interpretation and context is maybe left to managers/directors/decisions makers… They may be overwhelmed by the tyranny of the everyday… I think this is a very important process to engage in and get past that disconnect that still exists (Decision-maker).

The workshop provided an exchange and a space for reflecting on what the field is doing, what the research shows, leading to an awareness about the discrepancy between what they know to be best practice and the deficiencies in reality when they overlook clients’ expressed needs:

We all say that we’re strength-based, that we’re client-centered, and it’s just so ironic, that working with the individual in the absence of their relationships and their family, is exact opposite of client-centered (Decision-maker).

Families and Spouses Left Out of Treatment

Researchers and decision-makers rarely hear from clients about their experiences with emerging and innovative models. Workshop participants were surprised to learn firsthand how spouses are centrally important to their partners’ addiction recovery. Unfortunately, spouses were often left on their own. One decision-maker “was impressed by the level of commitment the spouses showed to their addicted partners” when he heard the pain in a client’s voice as she described her husband’s experience with treatment:

For me it was the woman who came in and told her story about her situation with her husband …, and I just heard her pain with respect to her husband’s previous experience with [addiction services], and his perception of how he was treated (Decision-maker).

Addicted individuals often felt shame about their condition and feared burdening their spouses with their struggles in recovery. Communication between partners does not occur easily or spontaneously. Clients’ first- person stories provoked treatment-providers and decision-makers to reflect on the system’s current practice. A manager described how her thinking altered during the workshop:

We may have been unintentionally doing, not harm, but not meeting the needs of family members as well as we could have, because traditionally we have not included the family much at all (Decision-maker).

Another manager reflected on the inadequacy of their present services when family members were always seen separately from the addicted clients:

We do have a family support group, but it’s always been separate from the individual presenting with the concern, it’s almost an add-on, and now having gone through these past few days, it’s shifted in terms of my knowledge, it’s a critical component in terms of the treatment process (Decision-maker).

Complacency of the System

Decision-makers were struck by the complacency of the system with regard to family engagement in the treatment of addiction. Making changes to include couple therapy is not a simple matter as it involves training of counselors, re-allocation of counsellors’ workload and proportion of time dedicated to the different programs. Although decision-makers realized couple and family engagement had been a gap in services, the gravity of such an omission did not hit home until they heard directly from the clients’ experience. One decision-maker remarked:

I think we’ve developed a sense of complacency around not having couple or family engagement … the client’s stories brought forth the importance and impact of revisiting that (Decision-maker).

Another decision-maker described that the new awareness motivated a call to action to change the system:

To me, it’s a call to action. We may not have known in the past, but now we can’t remain ignorant anymore, there’s been evidence, so now it’s a call to action … if we can get to the place where clinicians are thinking about implications, and influence in the treatment plan (Decision-maker).

Critical new awareness stirs energy for action, even if they are small increments of change to bring back to the system that incite others to think of the implications of this couple therapy gap in addiction services.

Involving Different Levels Within an Organization for System-Wide Changes

Interaction among decision-makers and end-user clients highlighted the need to involve multiple levels within an organization to make the necessary changes. Decision-makers described the value in hearing from counselors and clients about what was actually happening in the field. One manager described a change in his thinking about the role and involvement of family therapists in the organization, currently only available in adolescent services:

We have family therapists in our service continuum, now what is their role? How can they help us? How can we tap into their expertise? What has stopped them from speaking up (Decision-maker)?

The need for multi-level system change and leveraging existing resources was brought to the fore for another decision-maker:

For me going home, it’s what does our system do, and how can we broaden, how we do that to our whole system (Decision-maker)?

The need to build capacity for omitted services through staff training is recognized:

We’re seeing that there’s a training gap too and I’m really excited that we could maybe build capacity within the staff that we currently have, in current positions (Decision-maker).

Importance of Connecting Sectors

Researchers, decision-makers, and practitioners all agreed that practice could be improved when a space was created for connection across sectors. One researcher shared:

All of the pieces of the puzzle are there, people with different skillsets, service providers, and including the stories [from clients], that is actually the most powerful stimulus to persuade funders and policy makers, you can take that all the way to the Ministry of Health in terms of, here’s the impact, and if we could get that kind of response from clients and clients’ families in a broader addiction setting, that’s a very compelling piece of the puzzle. You need the hard evidence from the appropriate controlled study, but that piece is a very powerful message…great to see that included (Researcher).

Opportunities to connect with other stakeholders in the field and to discuss the inclusion of couples and families in addiction treatment are not a common occurrence, and the design of this workshop helped create those necessary connections:

Having opportunities to be seated at a table, opportunities to connect with some of the researchers, some of the informal break time…to me it’s important about how we make it happen here (Decision-maker).

Critical Workshop Components

Participants identified six critical components that led to the effectiveness of the workshop (Fig. 2).

Singular Focus

A sustained focus on one compelling issue was a key element to the workshop success, in this case, the couple counseling gap in addiction services. Participants found other workshops with knowledge translation on topics too broadly defined were less successful. The sharp “clear focus” led to the “bonding” of the group, allowing for concentrated discussion to emerge, and generated practical steps and strategies through consensus towards research and implementation.

Knowledgeable and Enthusiastic Leader

Participants cited the knowledgeable leadership providing evidence-based knowledge as central to galvanizing the group energy to propel the group in the intended direction.

It’s an interesting comparison to other such groups that we’ve tried to convene over recent years that didn’t seem to have gelled so well…we’re focused on a particular area and we had a champion of that area who is so enthusiastic about it, to teach us, and moreover brought the clients’ accounts, all key educational components to this meeting (Researcher).

Hearing the Clients’ Stories

Decision-makers are often a few steps removed from the lived experience of their clients, hence hearing first-hand from clients on how they were impacted without the couple services they needed was a wake-up call. During the workshop, two interviews were conducted with three client end-users who sought couple services in the health system and who subsequently took part in a couple therapy randomized trial to receive the couple therapy they were looking for. The first of these interviews featured Ray (pseudonym) who struggled with alcohol and gambling disorders, and his wife, Lesley (pseudonym). The second couple featured Karen (pseudonym) who, like Ray and Lesley, despaired of finding the help for couples within the system's addiction counseling services.

The “client perspective” component of the workshop called the attention of decision-makers to what was missing in the health system. An example that struck a chord in workshop participants was Lesley’s description that showed the disconnection and isolation between her and her husband:

I had no idea what all was happening in Ray’s life. Ray was really struggling … he had considered suicide, and I was quite scared and worried. The couple therapy was needed because everything that was happening was for Ray. He had services for him, but they didn’t include me…Like I was on my own, and it was really difficult…he had to go out every night for AA, he had to do all these things. His life became very busy, and nothing was happening for me in mine.

Ray had found it difficult to confide in his wife about his addictions:

It’s a lot easier to talk to a group of strangers than it is to talk to someone you love, and someone you don’t want to disappoint … the couples therapy allowed us to work on that.

The missing piece in addiction services is helping couples work through their marital issues together, both current family and their family-of-origin experiences. It became apparent from the couples’ accounts how difficult it was for them to talk to each other without some professional support. Treating the addiction and couple relationship as mutually influential draws upon a systemic understanding of addiction, which was a new perspective for some participants.

Another example that spoke to decision-makers was Karen’s tale of her own husband’s struggle with GD. She told of ways in which couple counseling helped them navigate that turbulent period of their life together. Her account is especially enlightening because it illustrates the ways in which lack of communication can impact addiction.

I wanted to protect my husband. He went through hell when he was younger… every time [couple therapist] would ask Ken a question, Ken would say this much, and then I would “blah blah blah.” And [the couple therapist] turned to me, and said, “Karen, you need to let him speak for himself.” It was eye-opening for me to understand that he wasn’t doing this to us, that his addiction was something that he couldn’t control, and I have to make room for him to express himself.

Karen alluded to the many "layers of the onion" including Ken’s reticence to talk and ask for help, and the healing from his traumatic childhood maltreatment, which otherwise carried over into his relationship with their son. Five years later, “our relationship is way better than it’s ever been,” she relayed, “I trust that he’s not going to gamble again—he won’t even buy 50/50 tickets at a hockey game.”

These poignant clients’ stories heightened decision-makers' awareness that despite the health system’s professed intention of serving families, in reality, family services were limited and impoverished. This realization troubled the decision-makers’ conscience as illustrated by the following comment:

We talk a lot around engaging the consumer … but we don’t really do it. So, once again, this kind of forwards the importance of having that stakeholder/consumer input, and the importance of hearing them (Decision-maker).

It was comments like Karen’s using common-sense language that spoke to the decision-makers, implicating the publicly funded system as responsible for the neglect of families afflicted by addiction, and insisting that awareness of such issues be augmented in the future:

I think that the government is doing a disservice to people; if they’re going to offer gambling, and they’re going to make money off it, then they need to make sure that the people who have a problem with it are treated properly… it became something what had to do with our family unit and with me. We had no guidance on where to go. I would have had to educate myself on addiction; so to me, I feel like, if not for the Congruence Couple Therapy program, then something that’s very similar to it, should be offered to heal the relationship (Client end-user).

Intentional Selection of Multi-sectoral Participants

It should be mentioned that many of the participants had some prior acquaintance with one another at provincial, inter-provincial meetings and symposia. Participants were united in one common interest: their concern for relationship issues in addiction and their desire to make a meaningful change. The intentional homogeneity of this group in their concerns for couples and their knowledge of the addiction field favoured its getting to a consensus for action in a short-time, although a broader-based, more heterogeneous group could be assembled for later-stage projects in the progressive diffusion of innovation (Rogers 2003). As one participant observed:

I think that we all came here because we’re pretty much self-selected, convinced that we need to do more relational work in addiction treatment, so that was almost a given for our presence here…we wouldn’t have come if we didn’t think that was of value. Moments that stuck out with me that I appreciated were the mix of clinicians, front-line, management, administration, research, and clients, that mix is very rich (Decision-maker).

By creating an atmosphere where traditional barriers such as differences in discipline, position and practice were lowered, the participants could step into another’s day-to-day context and gain a larger picture of where and how change can be synchronized to take place. Nutrition breaks, lunches and a group dinner allowed the group to interact at a social level to build camaraderie.

Researchers and service-providers mostly exist as two solitudes. A partnership-building workshop such as this helps to bridge the two operational and institutional cultures:

When we had a small group, some of the system questions being asked made it clear to me that we don’t really know each other’s systems very well, what are our processes, and these kind of things will really aid with how we look at research, interventions, and how we look at each other’s systems (Decision-maker).

Emotional and Experiential Modalities Balanced the Cognitive

The workshop used both emotional and experiential modalities of engagement in addition to the cognitive. An icebreaker exercise elicited participants’ experience in the field with couple and family counseling. The key words supplied by participants depicted the current state of couple and family counseling in the treatment system, such as “neglected, fractured, under-trained, excluded, rarely.” Key words such as “much needed, potent, dynamic, emerging, hopeful” showed the common aspirations regarding the importance of family and couple services.

Other experiential components of the workshop including clients’ accounts and case role-play exercise gave service providers and decision-makers a “window into the couples’ lived experience.” Role-players in the simulated cases were overcome by the visceral impact of speaking to their partner in the “here and now” and “eye to eye” in an authentic way without pretence. One manager said:

What prompted the call to action? I think it was the practical implications, it was the role play, as uncomfortable as it was at the start, it was my experience in that role play (Decision-maker).

Knowledge translation needed experiential stories that connect with emotions, such as those narrated by client end-users. Two addiction counselors trained in a systemic couple therapy model from another province provided first-hand accounts of their couple counseling with diverse client populations and how their training changed their practice and organizational systems in which they work. Evidence from research met with clients’ and other counselors’ real-life stories to create “a very powerful message.” Knowledge shared in the cognitive domain was balanced by experiential stories that engaged the emotions.

Committing to Action

Service flow maps showing where couple and family counseling could fit in the system gave a visual portrayal of potential new pathways generated through group discussion. A list of funding sources and community partners was brainstormed. A consensus building exercise resulted in ranked research priorities and formed a Relational Research Inter-Provincial Network. Members of this Network later sought out the funding and coalesced quickly for a major grant application. Small teams were formed around identified project priorities according to participants’ interests.

So this is exactly the kind of event that forms real pieces of networks… bringing a focal group together and seeking some funding opportunities that gives it some impetus to drive it forward…We can check the box on relevance, accountability and research quality (Researcher).

Workshop Outcomes

We were able to document the outcomes of the workshop in the research development that ensued within 2 years after the workshop.

Research Collaboration

The workshop mobilized collaboration across sectors and directional steps to improve service for couples in addiction services. A sub-group of researchers proceeded with a literature review of evidence-based systemic models for couple treatment in addiction and decided to use the results of a newly published meta-analysis of the efficacy of systemic therapies on adults with mental disorders, including addictive disorders. The meta-analysis covered articles published or presented by May 2014 (Pinquart et al. 2014). A key selection criterion was trials of therapies with a theoretical systemic orientation, as the authors noted that not all couple and family therapies are systemic and may also use other theoretical principles such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (Pinquart et al. 2014). Articles in the meta-analysis were identified by “comprehensive searches in well-established psychological and medical electronic databases” (Pinquart et al. 2014, p. 3). Inclusion was limited to randomized controlled trials, a design deemed to be most scientifically rigorous for testing intervention effects. The meta-analysis compared as well as integrated the results of studies that met criteria. Among the eight studies identified on addictive disorders, only three used conjoint couple therapy alone. Two of these trials were without efficacy when compared to controls (Karno et al. 2002; Zweben et al. 1988). The third, Congruence Couple Therapy, showed efficacious results with minimal treatment controls and was the only study with a follow-up for GD and its comorbidities (Lee and Awosoga 2014). Hence this was the model selected for further implementation study in the health system.

Acting as gate-keepers and leaders, health system directors, managers and supervisors were pivotal in helping researchers navigate the complexity of the health system. Within a year of this workshop, the collaborative team of researchers and the health system decision-makers successfully competed for three research grants for the purpose of: (1) evaluating a couple therapy training for addiction counselors; (2) investigating the effectiveness of couple therapy for gambling and alcohol disordered end-users and their partners; and (3) monitoring changes in depression symptoms in client end-users undergoing couple therapy. Researchers across two universities collaborated on crafting the research proposals.

Decision-makers gave approval and organizational support for research to be conducted in the health system. Supervisors gave their counselors release time for receiving couple therapy training and implementation in the clinical setting. Counselors assisted with recruitment and data collection. Health system internal evaluators contributed to collecting evaluation data on the couple therapy training, and the counselors’ assessment of the applicability and feasibility of making couple therapy a new option in addiction and mental health services.

Research Training

The partnership-building workshop and ensuing projects provided learning and research opportunities for more than 15 graduate and undergraduate trainees in addiction counseling, counseling psychology and health sciences, resulting in posters, publications and theses. The benefits from the partnership between researchers and the health system are multiplicative.

Discussion

Early Involvement of Decision-Makers in Knowledge Translation

Passive KT, as in disseminating textual or informational knowledge in the form of reports, databases, and websites, are not effective in changing practice; face-to-face interaction is necessary for systems-level change and uptake (Mareeuw et al. 2015; Miller et al. 2006). However, specifications of the type of interactions that facilitate IKT are seldom found in the literature (Bottorff 2015). This article describes how a two-day IKT workshop could effectively engage the health system to work with researchers incorporating client end-users’ input to enhance addiction services. Impactful components identified in this article for effective partnership-building add to the sparse literature on participatory KT in addiction and couple therapy research.

A pre-dominant focus on dissemination at the end of research over the early process of partnership-building for knowledge creation is featured in the substance abuse literature (Damschroder and Hagedorn 2011). Elements of KT in many gambling projects are discussed only implicitly rather than explicitly (Mackay et al. 2015). Marriage and family therapy is just beginning to recognize the importance of dissemination and implementation in expanding the impact of research findings into clinical settings (Withers et al. 2017). This project demonstrates elements important in IKT for the procurement of research funding and providing training in couple therapy in addiction clinical settings to further our understanding of couple therapy for addictive disorders and their comorbidities.

Critical Components of Integrated KT Workshop Design

The knowledge-broker role is one not readily embraced by researchers. Efforts spent in organizing participatory partnership-building workshops are time-consuming and are usually not well rewarded by publications in high impact journals (Mareeuw et al. 2015). Moreover, planning and creating a participatory workshop and its design with an evaluation component is not intuitive to many researchers (D’Alonzo 2010), but it is one that may come more easily to systems-thinkers and practitioners such as those in marriage and family therapy. It is an area where marriage and family therapists’ unique systemic skills and thinking combined with their sensitivity to political and contextual factors can make multi-level large-system changes happen.

Effective IKT utilizes both cognitive and emotive components. Couple stories lent authenticity and accentuated the emotional and human dimension of the issues at hand. Clients’ involvement is a new and growing concept in health science research, from agenda setting to protocol development and interpretation of research findings (Shippee et al. 2015), offering a balancing perspective to that of the researchers and service-providers (McKevitt et al. 2010). In this IKT workshop, client end-users helped to identify research and service gaps, speaking to the important couple therapy elements that helped them heal their relationships and addiction. Currently, we know more about the processes of client engagement than the outcomes of client engagement (Esmail et al. 2015). From this evaluation, we learnt that client end-users’ accounts can make a deep impression on decision-makers that transformed decision-makers’ awareness of couples’ relational needs and their awareness of the deficiencies in existing services.

Research from psychology and neurobiology provides support for the concept of multiple intelligences that include emotion, music, and kinesthetic engagement (Gardner 1983) in fostering change of meaning perspectives and transformative learning in adults (Taylor 2001). Interactive activities in our IKT workshop heightened engagement, using pictures, diagrams, role-plays, and a closing ritual with music, game and movement. Brain research is revealing a more integrated relationship between reason and emotion than posited (Ledoux 1989) and the two work together to transform how we perceive and act in the world. The combined experiential and cognitive aspects of the workshop were reportedly key to its impact, and could be incorporated more strategically in future interactive KT.

Doing Research Together

As gate-keepers, directors and managers are important research partners in opening doors into the complex health system, especially in the implementation of effectiveness and pragmatic trials that are deemed to have greater real-world value for applications than efficacy studies in the controlled laboratory setting (Singal et al. 2014). Funders of research need to continue to support these early-stage planning and partnership initiatives and the evaluation of the impactful ingredients that make them effective. Marriage and family therapists can suitably deploy their systems thinking and skill-set by involving stakeholders at various system levels to facilitate couple therapy and research within addiction treatment.

References

Bottorff, J. L. (2015). Knowledge translation: Where are the qualitative health researchers? Qualitative Health Research,25(11), 1461–1462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315611266.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2012). Guide to knowledge translation planning at CIHR: Integrated and end-of-grant approaches. Ottawa, ON: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada.

Cheung, N. W. (2015). Social strain, couple dynamics and gender differences in gambling problems: Evidence from Chinese married couples. Addictive Behaviors,41, 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.013.

Crane, D. R., Christenson, J. D., Dobbs, S. M., Schaalje, G. B., Moore, A. M., Pedal, F. F. C., … Marshall, E. S. (2013). Costs of treating depression with individual versus family therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 39(4), 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00326.x.

D’Alonzo, K. T. (2010). Getting started in CBPR: Lessons in building community partnerships for new researchers. Nursing Inquiry,17, 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2010.00510.x.

Damschroder, L. J., & Hagedorn, H. J. (2011). A guiding framework and approach for implementation research in substance use disorders treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors,25, 194. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022284.

Disis, M., & Slattery, J. (2010). The road we must take: Multidisciplinary team science. Science Translational Medicine,1, 22cm9. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3000421.

Ellen, M., Leon, G., Bouchard, G., Lavis, J., Ouimet, M., & Grimshaw, J. (2013). What supports do health system organizations have in place to facilitate evidence-informed decision making? A qualitative study. Implementation Science,8, 84–103. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-84.

Esmail, L., Moore, E., & Rein, A. (2015). Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: Moving from theory to practice. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research,4, 133–145. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer.14.79.

Fals-Stewart, W., O’Farrell, T. J., & Birchler, G. R. (2004). Behavioral couples therapy for substance abuse: Rationale, methods, and findings. Science & Practice Perspectives,2(2), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1151/spp042230.

Fals-Stewart, W., O’Farrell, T. J., Birchler, G. R., Cordova, J., & Kelley, M. L. (2005). Behavioral Couples Therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse: Where we’ve been, where we are, and where we were going. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy,19, 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(99)00026-4.

Gagliardi, A., Berta, W., Kothari, A., Boyko, J., & Urquhart, R. (2016). Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: A scoping review. Implementation Science,11, 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0399-1.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind. New York: Basic Books.

Goldner, E. M., Jenkins, E. K., & Fischer, B. (2014). A narrative review of recent developments in knowledge translation and implications for mental health care providers. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry,59, 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405900308.

Graham, I. D., Kothari, A., & McCutcheon, C. (2018). Moving knowledge into action for more effective practice, programmes and policy: Protocol for a research programme on integrated knowledge translation. Implementation Science, 13(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0700-y.

Karno, M. P., Beutler, L. E., & Harwood, T. M. (2002). Interactions between psychotherapy procedures and patient attributes that predict alcohol treatment effectiveness: A preliminary report. Addictive Behaviors,27, 779–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00209-X.

Kothari, A., & Wathen, C. N. (2013). A critical second look at integrated knowledge translation. Health Policy,109(2), 187–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.11.004.

Lang, E., Wyer, P., & Haynes, R. B. (2007). Knowledge translation: Closing the evidence to practice gap. Annals of Emergency Medicine,49, 355–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.08.022.

Ledoux, J. E. (1989). Cognitive–emotional interactions in the brain. Cognition and Emotion,3, 267–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699938908412709.

Lee, B. K. (2009). Congruence couple therapy for pathological gambling. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction,7, 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9464-3.

Lee, B. K. (2014). Towards a relational framework for pathological gambling (Part I): Five circuits. Journal of Family Therapy,36, 371–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2012.00588.x.

Lee, B. K. (2015). Towards a relational framework for pathological gambling (Part II): Congruence. Journal of Family Therapy, 37(1), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2012.00591.

Lee, B. K., & Awosoga, O. (2014). Congruence couple therapy for pathological gambling: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Gambling Studies,31(3), 1047–1068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9464-3.

Lee, B. K., & Rovers, M. (2008). ‘Bringing torn lives together again’: Effects of the first congruence couple therapy training application to clients in pathological gambling. International Gambling Studies, 8(1), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459790701878137.

Lee, B. K., Shi, Y., Gaelzer, J., Awosoga, O., & Christensen, D. (2017, November). Couples seeking Congruence Couple Therapy treatment for alcohol and gambling problems in a randomized trial. Poster presentation at the Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse (CRISM), Prairie Node, 2nd Annual Gathering, Calgary, AB.

Lencucha, R., Kothari, A., & Hamel, N. (2010). Extending collaboration for knowledge translation: Lessons from the community-based participatory research literature. Evidence and Policy,6, 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-59.

Leonard, K. E., & Eiden, R. D. (2007). Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology,3, 285–310. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424.

Mackay, T. L., Petermann, L., Hurrell, C., & Hodgins, D. (2015). Knowledge translation in gambling research: A scoping review. International Gambling Studies,15, 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2014.1003575.

Marchand, E., Stice, E., Rohde, P., & Becker, C. B. (2011). Moving from efficacy to effectiveness trials in prevention research. Behaviour Research and Therapy,49, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.008.

Mareeuw, F. D., Vaandrager, L., Klerkx, L., Naaldenberg, J., & Koelen, M. (2015). Beyond bridging the know-do gap: A qualitative study of systemic interaction to foster knowledge exchange in the public health sector in The Netherlands. BMC Public Health,15, 922. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2271-7.

McKevitt, C., Fudge, N., & Wolfe, C. (2010). What is involved in research and what does it achieve? Reflections on a pilot study of the personal cost of stroke. Health Expectations,13, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00573.x.

Miller, W. R., Sorensen, J. L., Selzer, J. A., & Brigham, G. S. (2006). Disseminating evidence-based practices in substance abuse treatment: A review with suggestions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment,31, 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005.

Morgan, T. B., & Crane, D. R. (2010). Cost-effectiveness of family-based substance abuse treatment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 36(4), 486–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2010.00195.x.

Morgan, T. B., Crane, D. R., Moore, A. M., & Eggett, D. L. (2013). The cost of treating substance use disorders: Individual versus family therapy. Journal of Family Therapy, 35(1), 2–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2012.00589.x.

Mushquash, A. R., Stewart, S. H., Sherry, S. B., Mackinnon, S. P., Antony, M. M., & Sherry, D. L. (2013). Heavy episodic drinking among dating partners: A longitudinal actor–partner interdependence model. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors,27, 178. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026653.

Pinquart, M., Oslejsek, B., & Teubert, D. (2014). Online). Efficacy of systemic therapy on adults with mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy Research,26, 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2014.935830.

Rodriguez, L. M., Neighbors, C., & Knee, C. R. (2014). Problematic alcohol use and marital distress: An interdependence theory perspective. Addiction Research & Theory,22(4), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2013.841890.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovation (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Selbekk, A. S., Adams, P. J., & Sagvaag, H. (2018). “A problem like this is not owned by an individual”: Affected family members negotiating positions in alcohol and other drug treatment. Contemporary Drug Problems,45(2), 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450918773097.

Selbekk, A. S., & Sagvaag, H. (2016). Troubled families and individualised solutions: An institutional discourse analysis of alcohol and drug treatment practices involving affected others. Sociology of Health & Illness,38, 1058–1073. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12432.

Shippee, N.D., Domecq Garces, J.P., Prutsky Lopez, G.J., Wang, Z., Elraiyah, T.A., Nabhan, M., … Murad, M.H. (2015). Patient and service user engagement in research: A systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expectations, 18, 1151–1166. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12090.

Simmons, J., & McMahon, J. M. (2012). Barriers to drug treatment for IDU couples: The need for couple-based approaches. Journal of Addictive Diseases,31(3), 242–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2012.702985.

Simmons, J., & Singer, M. (2006). I love you… and heroin: Care and collusion among drug-using couples. Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention and Policy,1, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-1-7.

Singal, A. G., Higgins, P. D., & Waljee, A. K. (2014). A primer on effectiveness and efficacy trials. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology,5, e45. https://doi.org/10.1038/ctg.2013.13.

Taylor, E. W. (2001). Transformative learning theory: A neurobiological perspective of the role of emotions and unconscious ways of knowing. International Journal of Lifelong Education,20, 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370110036064.

Tolchard, B. (2017). Cognitive-behavior therapy for problem gambling: A critique of current treatments and proposed new unified approach. Journal of Mental Health,26, 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.

Tremblay, J., Dufour, M., Bertrand, K., Blanchette-Martin, N., Ferland, F., Savard, A. C., et al. (2018). The experience of couples in the process of treatment of pathological gambling: Couple versus individual Therapy. Frontiers in Psychology,8, 2344. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02344.

Wild, T. C., Wolfe, J., Wang, J., & Ohinmaa, A. (2014). Gap analysis of public mental health and addictions programs (GAP-MAP). Final report. Edmonton: Government of Alberta. Retrieved February 18, 2018, from https://alberta.cmha.ca/documents/gap-map-final-report/.

Withers, M. C., Reynolds, J. E., Reed, K., & Holtrop, K. (2017). Dissemination and implementation research in marriage and family therapy: An introduction and call to the field. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy,43(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12196.

Zwarentstein, M., & Treweek, S. (2009). What kind of randomized trials do we need? Canadian Medical Association Journal,180, 998–1000. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.082007.

Zweben, A., Pearlman, S., & Li, S. (1988). A comparison of brief advice and conjoint therapy in the treatment of alcohol abuse: The results of the marital system study. British Journal of Addiction,83, 899–916. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb01583.x.

Funding

This project was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Partnerships for Health Services Improvement Planning Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Bonnie Lee is the developer of Congruence Couple Therapy, an integrated systems model for substance abuse and gambling treatment. Robert Gilbert and Rebecca Knighton have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, B.K., Gilbert, R. & Knighton, R. Couple Therapy in Substance Use and Gambling Disorders: Promoting Health System Change. Contemp Fam Ther 42, 228–239 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-020-09536-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-020-09536-8