Abstract

This study investigated adult attachment dimensions as predictors of interpersonal forgiveness, positive emotionality, and social justice commitment through dimensions of differentiation of self. The sample consisted of 209 master’s level graduate students at a Protestant-affiliated university in the United States. Results revealed that higher attachment anxiety was associated with decreased differentiation of self and that decreased differentiation of self was then associated with lower levels of interpersonal forgiveness, positive emotionality and social justice commitment. Increased attachment avoidance was similarly associated with decreased differentiation of self, which then corresponded to lower levels of interpersonal forgiveness, positive emotionality and social justice commitment. Findings are discussed in the context of existing theory and research, and attention is given to the implications for clinical training and practice and future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Relational theories of development such as adult attachment theory (e.g., Brennan and Shaver 1995; Brennan et al. 1998; Mikulincer and Shaver 2007) and Bowen’s family systems theory (Bowen 1978; Kerr and Bowen 1988) provide a framework for understanding the influence of interpersonal dynamics on adults’ psychological health (i.e., positive and negative mood/emotionality, anxiety, and depression) and social well-being (i.e., prosociality, effective interpersonal processes, and other-oriented-ness). Empirical research has linked secure attachment experiences to several positive indicators of psychological health and social well-being, including emotion regulation, self-control, persistence, effective conflict management, and functional expression of anger (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007).

Differentiation of self (DoS), a developmental construct central to Bowen’s theory, refers to an individual’s self-regulatory capacity along intra- and inter-personal dimensions (Skowron and Schmitt 2003). DoS has similarly shown positive associations with indicators of individual level psychological health and relational level social well-being such as psychological adjustment, self-control, interpersonal forgiveness, social connectedness, and marital and life satisfaction (Holeman et al. 2011; Krycak et al. 2012; Ross and Murdock 2014; Sandage and Jankowski 2010; Skowron and Dendy 2004; Skowron et al. 2003; Williamson et al. 2007). Construct validation evidence exists for conceptualizing DoS along intra- and inter-personal dimensions, as measured by the widely used Differentiation of Self Inventory—Revised (DSI-R; Skowron and Schmitt 2003; see also, Jankowski and Hooper 2012). The intra-personal dimension is assessed by the DSI-R subscales of emotional reactivity and I-position, whereas the interpersonal dimension is assessed by the emotional cutoff subscale, and to a lesser extent the fusion with others subscale (i.e., the latter has shown convergent associations with the intrapersonal subscales in some samples). In addition, DoS dimensions have demonstrated differential associations with both psychological health and social well-being. For example, emotional cutoff uniquely predicted lower emotional distress and less interpersonal difficulties over time (Skowron et al. 2009), whereas emotional reactivity mediated the positive association between level of life stressors and psychological distress (Krycak et al. 2012).

Despite the evidence for a positive association between adult attachment security and differentiation of self (e.g., Skowron and Dendy 2004; Thorberg and Lyvers 2006; Timm and Keiley 2011; Wei et al. 2005), empirical investigations integrating both adult attachment and DoS are few. One possible explanation for the lack of research integrating both adult attachment and DoS is the perceived incompatibility between constructs (e.g., Johnson 2004; Schnarch 2009). A primary point of contention centers on how affect regulation is thought to occur, with differentiation-based approaches said to emphasize containment of or a controlled distance from emotional reactivity and attachment-based therapies described as focusing on experiencing and expressing primary emotions in ways that move through or “beyond reactivity” (Johnson 2004, p. 231).

Despite differences, there appears to be overlap between the two constructs. First, both adult attachment and DoS refer to an individual’s capacity for emotion regulation in interpersonal relationships, with insecure attachment experiences and lower levels of DoS both corresponding to increased use of dysfunctional coping strategies (Skowron and Dendy 2004; Thorberg and Lyvers 2006; Wei et al. 2005). However, DoS has been conceptualized as and empirically found to be a mechanism by which attachment experiences are associated with prosocial and health outcomes (Jankowski and Sandage 2014; Wei et al. 2005). In other words, as indicators of “felt insecurity,” the adult attachment dimensions of anxiety and avoidance are associated with lowered well-being through lowered emotion regulation capacities, as measured by the intra- and inter-personal DoS dimensions. For example, Wei et al. (2005) found that emotional reactivity mediated the positive association between both attachment anxiety and negative mood and attachment anxiety and interpersonal problems, whereas emotional cutoff mediated the associations between attachment avoidance and negative mood, and interpersonal problems. Similarly, Tasca et al. (2009) found that emotional reactivity mediated the association between attachment anxiety and both depression and eating disorder symptoms, whereas emotional cutoff mediated the attachment avoidance and depression association. Nevertheless, a second way that attachment and DoS share conceptual overlap is noted by Johnson (2004) who suggested that if DoS involves the ability to “cope with the anxiety of being different and separate from others” it is essentially “part of attachment theory” (p. 233); describing such a state “as differentiation with rather than differentiation from” others (p. 233). Schnarch (2009) similarly acknowledged that differentiation with is preferable to differentiation from. The former implies a healthy negotiation of intimacy and autonomy in significant attachment relationships whereas the latter may denote unhealthy emotional cutoff. Differentiation with is consistent with Bowen’s original conceptualization (Kerr and Bowen 1988).

The current study tests a mediation model of the associations between the adult attachment dimensions of anxiety and avoidance and indicators of well-being, with DoS dimensions as mechanisms of the respective associations in a sample of graduate students in the helping professions. Two contrasting orientations toward well-being—hedonic and eudaimonic—have been widely discussed and studied within recent positive psychology literatures (e.g., see Henriques et al. 2014; Wong 2011). In short, hedonic approaches to well-being focus on subjective feelings of individual happiness, pleasure, and life satisfaction, whereas eudaimonic views of well-being emphasize personal growth, virtue and ethical development, and relational or systemic flourishing in addition to emotional health. Our systemic approach to well-being is more eudaimonic, and we investigated three different forms of well-being which we review in relation to attachment and DoS below: (a) interpersonal forgiveness (i.e., prosociality in the form of benevolent relating to the offender, and as such is arguably one indicator of relational or social well-being), (b) positive emotionality (individual level, psychological health), and (c) social justice commitment (i.e., ethical prosociality in the form of concern for the well-being of others, and as such is arguably another indicator of relational or social well-being).

Social justice commitment might seem unrelated to “well-being” in the minds of some; however it represents a concern for the well-being of others who have suffered injustice and is considered a key ethical dimension of personal and communal or social well-being in many non-Western traditions (e.g., Joshanloo 2014; Ryff and Singer 1998). There have also been increasing calls to move beyond individualistic approaches to well-being as subjective happiness (hedonic view) and move toward defining psychological well-being in ways that explicitly include a concern for ethical values such as social justice (e.g., Cohrs et al. 2013; Henriques et al. 2014; Prilleltensky 2012). We also review research below showing social justice commitment has been negatively correlated with mental health symptoms and positively associated with other measures of virtue, well-being, and mature relational development. There have also been important calls for increased attention to social justice in the training of counselors, psychotherapists, and other helping or human service professions to overcome historical neglect of social justice in training curricula (Blackmore 2013; Košutić and McDowell 2008; Murphy et al. 2006; Sandage et al. 2014; Sandage et al. 2014). The present study fits within an emerging stream of research investigating associations between social justice commitment and other aspects of emotional and relational development and well-being (Garcia et al. 2015).

Adult Attachment, DoS, and Forgiveness

Forgiveness is a response to interpersonal conflict that involves regulating negative emotions and prosocial and benevolent relating to the offender (McCullough et al. 1997) and evidence for the positive association between attachment security and forgiveness has been consistently demonstrated. Results of a study by Lawler-Row et al. (2006), for example, indicated that securely attached participants reported greater levels of both state (i.e., forgiving a specific wrong or offender) and trait/dispositional (i.e., likelihood of or tendency to forgive) forgiveness than insecurely attached individuals following betrayals by close associates. Burnette et al. (2007) showed that secure attachment was more positively correlated with forgiveness than insecure attachment, and Burnette et al. (2009) found that insecurely attached individuals were less likely to forgive than securely attached individuals. Among anxiously attached individuals, reduced forgiveness was partially due to increased angry rumination, whereas among avoidant individuals, reduced forgiveness was partially due to a lack of empathy for the offender (Burnette et al. 2009). Last, Jankowski and Sandage (2011) found a negative association between attachment insecurity and dispositional forgiveness.

The association between DoS and interpersonal forgiveness has received considerably less empirical attention than the attachment-forgiveness association. Nevertheless, it has been theorized that higher levels of DoS would correlate with enhanced forgiveness (Hill 2001). While limited, existing research provides evidence for the positive association between DoS and forgiveness (Sandage and Jankowski 2010). DoS was also found to mediate the relationship between sacred loss/desecration (i.e., experience of transgressions which carry spiritual or religious significance) and forgiveness (Holeman et al. 2011). Holeman et al. (2011) also found that all four dimensions of DoS [i.e., emotional reactivity (ER), ‘I’ position (IP), emotional cutoff (EC), and fusion with others (FO)] predicted increased interpersonal forgiveness.

Adult Attachment, DoS, and Positive Emotionality

Both adult attachment theory and the construct of DoS center on the individual’s capacity to regulate distressing emotions. And yet, empirical research on the degree to which secure attachment is associated with positive emotion is limited (Shiota et al. 2006), and the same could be said of the literature on DoS and positive mood. Evidence supports conceptualizing negative and positive affect as relatively independent mood dimensions (Watson et al. 1988). As such, both dimensions should be studied as distinct outcomes in order to advance the literature on adult attachment and well-being. Shiota et al. (2006) found negative associations between adult attachment anxiety and the positive emotions of joy, contentment, pride and love, whereas adult attachment avoidance was negatively associated with love and compassion. Barry et al. (2007) found that anxious and avoidant attachment correlated with higher levels of negative affect and lower levels of positive affect in comparison to securely attached undergraduates, whereas high scores on attachment anxiety predicted greater negative mood and lower positive mood among participants when observing a distressed couple (Wood et al. 2012). Empirical findings specific to DoS demonstrate negative associations between DoS and negative affect (Sandage and Jankowski 2010; Skowron 2000; Krycak et al. 2012), and associations between greater DoS and increased positive emotionality (Jankowski and Sandage 2012; Sandage and Jankowski 2010).

In one of the few studies that involved both adult attachment and DoS, Wei et al. (2005) found that attachment anxiety predicted increased negative mood, with the DoS dimension of emotional reactivity as a unique mediator. In addition, Wei et al. found that the DoS dimension of emotional cutoff uniquely mediated the association between attachment avoidance and interpersonal difficulty. Mikulincer et al. (2001) examined negative emotionality in relation to both attachment and forgiveness, and found that those experimentally primed to experience secure attachment were better able than their counterparts to regulate negative emotion related to past interpersonal harms. Self-reported anxious attachment was associated with increased negative emotions when recalling past transgressions. In addition, an intervention promoting forgiveness demonstrated gains in attachment security and psychological health for insecurely attached college students from pre-test to post-test (Lin et al. 2013).

Adult Attachment, DoS, and Social Justice Commitment

We found no empirical studies exploring the association between adult attachment and social justice commitment, and the research on DoS and social justice commitment yielded only a few studies. From a theoretical perspective, social justice commitment would appear to be consistent with secure attachment. It may be that social justice commitment requires a secure base from which to engage distressing social situations. Conversely, insecure attachment experiences may reflect a tendency to avoid the suffering and injustice others experience. Low social justice commitment may also point to attachment anxiety with the corresponding emotion dysregulation precluding attention to larger social problems or the struggles of others.

Attachment has been studied in association with a number of variables closely related to social justice commitment, including empathy, compassion, altruism, and volunteerism. Mikulincer et al. (2005), for example, found that insecure attachment predicted lower levels of compassion and altruistic behavior in a sample of Israeli university students. Based on these findings, the authors hypothesized that healthy attachment promotes benevolent feelings and caring behaviors toward others, while insecurity interferes with compassion; the latter of which is consistent with the findings of Shiota et al. (2006). Gillath et al. (2005) demonstrated that adult attachment avoidance predicted decreased volunteerism. A replication of this study revealed that individuals with attachment anxiety tended to endorse egoistic motivations (i.e., self-enhancement, social approval) for volunteering (Erez et al. 2008). Mikulincer et al. (2001) found that priming secure attachment strengthened empathetic reactions to the plight of other Israeli undergraduate students. The same study revealed that individuals reporting inclinations to anxious or avoidant attachment express lower levels of empathy toward others.

Theory also suggests a link between DoS and social justice commitment. DoS is characterized by a mature sense of self, the capacity to form intimate connections, and the ability to temper interpersonal emotional reactivity. The emotion regulation aspect of DoS may facilitate optimal management of distress related to the interpersonal and systemic challenges of social justice work (Sandage et al. 2014). Also, those high in social justice commitment may be confronted with opposing views from family members, friends, co-workers, and significant others. In these cases, the ability to negotiate the demands of individuality and intimacy while avoiding emotional fusion and reactivity may serve as a buffer against relational strain (Sandage et al. 2014). Empirical evidence indicates that social justice commitment is consistent with numerous indicators of well-being and mature expressions of self-hood, including DoS (Jordan 2010; Sandage et al. 2014; Jankowski et al. 2013). Higher levels of DoS have been found to predict increased commitment to social justice (Sandage and Jankowski 2013), and hope has demonstrated a mediating effect in the DoS-social justice association (Sandage et al. 2014). Social justice commitment has also been negatively associated with mental health symptoms (Jankowski et al. 2013), and beliefs in justice for both self and others have been positively associated with life satisfaction and self-rated health (Lucas et al. 2013).

The Present Study

The present study examined the mediating role of the DoS dimensions in a model predicting interpersonal forgiveness, positive emotionality, and social justice commitment from the adult attachment dimensions of anxiety and avoidance in a sample of graduate students in the helping professions (marriage and family therapy, children and family ministry, ministry, education, and leadership). In doing so, we examined both individual level psychological health (i.e., positive and negative mood) and well-being at the relational/social level (i.e., prosociality, in the form of interpersonal forgiveness and social justice commitment). More specifically, we hypothesized that differentiation of self would mediate the negative associations between attachment dimensions and each of the dependent variables. In doing so, we sought to address the lack of research combining both adult attachment and DoS in models predicting well-being. The mediating role for DoS dimensions is based on previous research demonstrating that (a) emotional reactivity and I-position functioned as unique predictors of effortful control beyond the influence of attachment dimensions (Skowron and Dendy 2004), and (b) the dimensions of emotional reactivity and emotional cutoff mediated the associations between attachment dimensions and well-being (Tasca et al. 2009; Wei et al. 2005). Conceptually, the mediating role for DoS is grounded in an understanding that adult attachment dimensions represent a dynamic interplay of trait and “state-level (contextual) attachment” (Bell 2009, p. 192), with state attachment referring to the subjective experience of “felt security” (Granqvist and Hagekull 2000, p. 122), whereas DoS is defined as self-regulation capacity along intra- and inter-personal dimensions (Skowron and Dendy 2004; Skowron and Schmitt 2003; Skowron et al. 2003). Taken together, the proposed model posits that “felt insecurity” is negatively associated with measures of well-being and that deficits in self-regulation capacity stemming from insecure attachment experiences function as the mechanism predicting well-being. In addition, existing research findings posit a unique mediating role for different aspects of DoS when examining associations between adult attachment and well-being, which emphasizes the need to examine each dimension as a distinct mediator in the model. The sample allowed us to investigate these aspects of relational development and well-being among graduate students preparing for vocations in which psychological health and effective, prosocial relational capacity will be pivotal.

Method

Participants

Participants were 209 master’s-level students from a Protestant-affiliated university in the Midwest. They ranged in age from 21 to 63, and the mean age was 34.66 (SD = 10.81). The sample was 51.2 % female and 47.8 % male. The majority of the participants (89.5 %) identified as White/European-American, 3.8 % identified as Asian/Asian-American, 3.3 % identified as Black/African-American, 1.4 % Native American and 1.0 % as Chicano/Hispanic/Latina. Demographic data were missing for two participants.

Measures

Adult Attachment

Adult attachment was measured using the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR; Brennan et al. 1998). The ECR is a 36-item self-report measure designed to assess the anxiety (ECR-AX) and avoidance (ECR-AV) dimensions of adult attachment. Each dimension is assessed using 18 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). The anxiety scale measures preoccupation with relationships, particularly a fear of abandonment and rejection, as well as a desire to be close to others. Items include “I worry about being abandoned” and “I worry a fair amount about losing my partner.” The avoidance scale assesses the level of discomfort with emotional closeness (i.e., intimacy) within the context of romantic relationships. Examples of items from the avoidant scale include “I am nervous when partners get too close to me” and “I feel comfortable depending on romantic partners.” The ECR has demonstrated validity and achieved internal consistency scores of Cronbach’s alphas = .91 for the ECR-AX and .94 for the ECR-AV (Brennan et al. 1998). In the current study, α = .91 for ECR-AX and .93 for ECR-AV.

Differentiation of Self

The Differentiation of Self Inventory-Revised (DSI-R; Skowron and Schmitt 2003) is a 46-item self-report measure of Bowen’s concept of differentiation of self. Two of the subscales [emotional reactivity (ER), I-position (IP)] assess the intrapersonal dimension of differentiation of self (Skowron et al. 2003). The other two subscales [emotional cutoff (EC), fusion with others (FO)] assess the interpersonal dimension. Higher scores reflect greater differentiation (i.e., less ER, less EC, less FO, and more I-P). Participants rated items on a scale from 1 (not at all true of me) to 6 (very true of me). Sample items include “There’s no point in getting upset about things I cannot change” and “When things go wrong, talking about them usually makes it worse.” The DSI-R has demonstrated construct validity and a full scale internal consistency score of α = .92 (Skowron and Schmitt 2003). Scores on the subscales ranged from α = .81 to .89 (Skowron and Schmitt 2003). In the current study, internal consistency scores were α = .87 for ER, .79 for IP, .85 for EC, and .78 for FO.

Dispositional Forgiveness

An 11-item self-report version of the Disposition to Forgive Scale (DFS; McCullough et al. 2002) was used to measure an individual’s perception of her or his tendency to forgive in interpersonal relationships. The items consist of a Likert scale response from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) regarding the degree to which the individual engages in different responses to others who have hurt or angered him or her. Items include positively worded statements (e.g., “I don’t hold it against him/her for long”) and negatively worded statements (e.g., “I will find a way to even the score”). The DFS exhibited evidence of convergent and discriminant validity (McCullough et al. 2002) and has demonstrated internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha scores ranging from .81 to .88 (Sandage and Crabtree 2011; Sandage and Jankowski 2010; Sandage and Williamson 2010). Cronbach’s alpha for the DFS in the current study was .89.

Positive Emotionality

The Positive Affect (PA) scale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson et al. 1988) was used to assess positive emotionality. PA refers to a distinct mood dimension, largely independent from negative affect, with higher scores suggesting affective experiences of enthusiasm, contentment and satisfaction. The PA scale contains 10 items that have shown good internal consistency (α > .84), and the scale has demonstrated theoretically consistent convergent and discriminant validity (Merz and Roesch 2010; Watson et al. 1988). Participants rated the extent to which they generally experienced each adjective on a 5-point scale from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Sample adjectives on the PA scale include “determined,” “inspired,” and “proud.” Cronbach’s alpha for the PA scale in the current study was .88.

Social Justice Commitment

Social justice commitment was measured by extracting three items from the Horizontal subscale of the Faith Maturity Scale (FMS-H; Benson et al. 1993). The FMS-H measures commitments to altruism, compassion, and helping others. We used three items that focused on social justice commitment with language that was not explicitly religious or spiritual: (a) “I am active in efforts to promote social justice,” (b) “I speak out for equality for women and persons of color,” and (c) “I care a great deal about reducing poverty in the USA and throughout the world.” Participants rated each item on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (I strongly disagree) to 9 (I strongly agree). Scores were calculated by summing the three items. The three items had an internal consistency in this study of Cronbach’s alpha = .69.

Data Analytic Procedures

The proposed mediation model was examined using structural equation modeling (SEM) in AMOS 7.0 (Arbuckle 2006; Byrne 2010). Multivariate outliers were non-problematic (D 2 values were not distinctively apart; Byrne 2010). Multivariate normality was not violated (i.e., multivariate kurtosis critical ratio was <5.00; Byrne 2010). Individual variables of attachment avoidance, forgiveness, positive emotionality, and social justice commitment exhibited skewness (skewness critical ratios >2.5 or < −2.5), whereas univariate kurtosis was not a problem (kurtosis critical ratios were <2.5 or > −2.5). Given multivariate normality and non-problematic kurtosis values MLE analyses were conducted (Byrne 2010). Tests of the specific indirect effects were examined using the Monte Carlo Method for Assessing Mediation (MCMAM; MacKinnon et al. 2004; Preacher and Selig 2012; Selig and Preacher 2008). The MCMAM was used because the AMOS output provided total indirect effects and therefore did not permit examination of the specific indirect effects. The AMOS bootstrap procedure did provide the necessary information for conducting the MCMAM.

Results

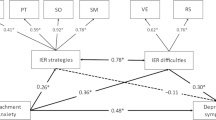

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the variables used in the analyses. Gender and age were examined in relation to each of the dependent variables, while ethnicity was not due to the small sample sizes in all but one of the groups. Age and gender were not associated with forgiveness, positive emotionality, or social justice commitment. SEM analysis tested the model for fit with the data. The model is presented with standardized regression weights from the AMOS bootstrap procedure in Fig. 1. The results supported the model: χ2 = 2.98(3), p = .39, CFI = 1.00; SRMR = .01, RMSEA = .00 (90 % CI [.00, .12]), PCLOSE = .60.

Mediation model of the associations between adult attachment, differentiation-of-self dimensions, and well-being outcome measures. Note N = 209. ATT-ANX attachment anxiety, ATT-AV attachment avoidance, ER emotional reactivity, IP I-Position, EC emotional cutoff, FO fusion with others, DF dispositional forgiveness, PE positive emotionality, SJC social justice commitment. The DSI-R involves reverse scoring such that higher scores on each subscale represent greater differentiation-of-self. χ2 = 2.98(3), p = .39, CFI = 1.00; SRMR = .01, RMSEA = .00 [90 % CI (.00, .12)], PCLOSE = .60. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Examination of the Specific Indirect Effects

The MCMAM revealed a significant specific indirect effect between attachment anxiety and forgiveness with emotional reactivity as the mediator, B = −.12, 95 % CI (−.22, −.02). The direct effect between attachment anxiety and forgiveness was nonsignificant [AMOS bootstrap analysis: B = −.15, SE = .08, 95 % CI (−.31, .01)]. The MCMAM revealed a significant specific indirect effect between attachment anxiety and positive emotionality through emotional cutoff [B = −.04, 95 % CI (−.07, −.01)] and through I-position [B = −.09, 95 % CI (−.14, −.04)]. The direct effect between attachment anxiety and positive emotionality was nonsignificant [AMOS bootstrap analysis: B = −.05, SE = .05, 95 % CI (−.14, .04)]. The MCMAM revealed a significant specific indirect effect between attachment anxiety and social justice commitment through fusion with others [B = −.42, 95 % CI (−.86, −.03)] and through I-position [B = −.49, 95 % CI (−.91, −.13)]. The direct effect between anxious attachment and social justice commitment was nonsignificant [AMOS bootstrap analysis: B = .21, SE = .44, 95 % CI (−.68, 1.06)]. A lone specific indirect effect was observed between attachment avoidance to positive emotionality through emotional cutoff [B = −.09, 95 % CI (−.16, −.03)]. The direct effect between avoidance and positive emotionality was nonsignificant [AMOS bootstrap analysis: B = −.06, SE = .06, 95 % CI (−.17, .05)]. The direct effects between avoidance and forgiveness, and avoidance and social justice commitment were also nonsignificant (see also Fig. 1).

Discussion

The results of the current study revealed significant indirect effects between attachment anxiety and each of the dependent variables (i.e., dispositional forgiveness, positive emotionality, social justice commitment) through DoS, as measured by different subscales of the DSI-R. An indirect effect was also observed between attachment avoidance and positive emotionality through DoS (i.e., interpersonal dimension, as measured by the emotional cutoff subscale of the DSI-R). The findings suggest that attachment experiences of anxiety and avoidance are incompatible with particular expressions of psychological health and social well-being; which is consistent with a number of empirical studies exploring adult attachment (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007; Shiota et al. 2006; Tasca et al. 2009; Wei et al. 2005).

Furthermore, distinct aspects of DoS mediated associations between adult attachment dimensions and the dependent variables. The association between attachment anxiety and dispositional forgiveness was mediated by increased emotional reactivity, such that increased anxiety was associated with lower DoS (i.e., increased emotional reactivity); the latter which was then associated with decreased likelihood of forgiving. This finding supports previous studies indicating attachment insecurity is less conducive to forgiveness (e.g., Burnette et al. 2007, 2009; Jankowski and Sandage 2011). Attachment anxiety involves an unyielding desire for closeness, and yet the individual feels disconnected from others which can exacerbate the experience of distress. Schnarch (2009) asserted that those whose psychological health depended on felt connection to others were unlikely to possess the internal resources to regulate one’s emotions or respond calmly in the face of relational adversity. Attachment anxiety seems to prevent persons from managing the painful emotions (i.e., anger, disappointment, and humiliation) associated with being wronged. Our findings are consistent with others who found that the ability to regulate negative emotion plays a role in dispositional forgiveness (Holeman et al. 2011; Sandage and Jankowski 2010).

The emotional cutoff and I-position aspects of differentiation uniquely mediated, when controlling for the other DoS dimensions, the association between attachment anxiety and positive emotionality. More specifically, increased anxiety was associated with lower DoS (i.e., increased emotional cutoff and decreased I-positioning), and both increased emotional cutoff and decreased I-positioning were then associated with lower positive mood. Our findings expand the findings of Shiota et al. (2006) who found negative associations between attachment anxiety and distinct positive emotions, whereas we observed intra- and inter-personal affect regulation as mechanisms of the association between attachment anxiety and positive mood. Similarly our findings expand those of Wei et al. (2005) who observed that intra-personal affect regulation was a mechanism of the association between attachment anxiety and negative mood. Anxiety seems to foster emotional distance as a means to manage relational distress, which then constricts one’s ability to experience positive affect. Anxiety may also result in difficulty maintaining a stable sense of self and standing up for what the individual believes. While such acquiescence may curb relational anxiety, it may also undermine self-respect. It is plausible that the inability to take an I-position would promote shame and restrict positive emotions. The experience of shame may also reinforce relational insecurity, perpetuating the need for validation from others.

The I-position and fusion with others dimensions of differentiation of self were found to mediate the association between attachment anxiety and social justice commitment. In this case, higher attachment anxiety predicted lower DoS (i.e., higher fusion with others and decreased I-positioning), which then predicted decreased commitment to social justice. One might speculate that a strong desire for relational closeness would be associated with greater concern for the rights and needs of others. On the other hand, attachment anxiety is often consistent with high concern for having one’s own emotional needs met and thus, persons may express less concern for the well-being of others. Our findings suggest that excessive emotional investment in one’s close relationships and the benefits accrued may undermine concern for those who are oppressed and marginalized. In terms of the mediating effect of I-position, social justice commitment often requires the ability to hold fast to personal convictions at the risk of facing scorn and opposition from others. Attachment anxiety may lessen tolerance for such risk. Disagreement or scorn may engender perceptions of relational distance, cultivating emotional turmoil and perhaps conciliation to alleviate distress.

Attachment avoidance was associated with positive emotionality indirectly through the emotional cutoff dimension of differentiation of self. More specifically, higher avoidance was associated with increased cutoff, which was then associated with decreased positive mood. Our finding is consistent with that of Wei et al. (2005) who found that emotional cutoff functioned as a unique mediator between attachment avoidance and negative mood. It is not surprising that avoidant attachment is associated with emotional cutoff. It is theorized that a function of attachment avoidance is to protect the self from the experience of disappointment, resentment, and/or trauma in the context of relationships. That being said, shielding oneself from the negative emotions commonly linked to close relationships also prevents exposure to the positive emotions that may be found through interpersonal relating. Thus, avoiding relational closeness restricts one’s ability to experience positive emotions.

No direct effects were observed between the attachment dimensions and any of the dependent variables. The findings suggest that DoS plays a unique role in the observed association between increased insecure adult attachment and lowered well-being, and that distinct dimensions play unique roles when other DoS dimensions are controlled. The findings, therefore, offer further empirical support for the notion that intra- and inter-personal capacities for affect regulation account for the positive association between secure adult attachment and well-being (Jankowski and Sandage 2014; Skowron and Dendy 2004; Wei et al. 2005), or conversely, that emotion regulation difficulties account for the negative association between insecure attachment experiences and lowered well-being.

Our hypothesis that attachment avoidance would be indirectly associated with forgiveness and social justice commitment through DoS dimensions was not supported; although the finding approached significance for social justice commitment. In the context of interpersonal offense, those inclined toward experiencing discomfort with emotional closeness (i.e., avoidance) may become genuinely indifferent to forgiveness, and therefore less likely to forgive as shown by the significant bivariate association between attachment avoidance and forgiveness. It is plausible that avoidance leads to a disregard of the need for forgiveness since the individual feels no desire for the increased intimacy associated with the relational repair that may result from forgiving the other. At first glance, it may be surprising to observe a nonsignificant indirect effect between attachment avoidance and social justice commitment; given that individual paths in the association were significant. It seems plausible however that some measure of differentiated functioning could be adaptive in social advocacy work (IP and FO dimensions did demonstrate significant positive bivariate associations with social justice commitment). Healthy DoS (i.e., balanced autonomy and connectedness) may protect the ego from opponent criticism, making one more likely to retain confidence and resolve in one’s cause. Also, social justice commitment may not require a deep connection or sensitivity to the other. One can possess admirable principles and take concrete actions to benefit others without feeling “close” to the people he or she supports.

Clinical Implications

Since this sample consisted of master’s level students in the helping professions, the most direct clinical implication pertains to the developing self of the professional. Professionals experiencing attachment anxiety and avoidance in their significant relationships and/or in clinical contexts may have difficulty balancing togetherness and separateness impulses and may need to take steps to enhance their affect regulation skills. It may be expected that in a therapeutic context that the professional’s own capacity to regulate negative affect in the face of wrongdoing or attachment injuries interfaces with her or his clients’ emotional experience and affect regulating skills. Such interface issues may limit the development of a strong therapeutic alliance and may prevent families and couples struggling to recover from relational transgressions to effectively make changes in their relationships.

Our results also suggest that individuals who resort to emotional distancing to manage attachment distress may be more vulnerable to lower levels of positive emotions. For those in the helping professions, positive emotionality and positive regard are crucial in the development of effective therapeutic alliances. Recognizing and modifying less functional means of emotional coping are likely to be important both for an individual’s psychological health, but also in strengthening therapeutic relationships. A strong sense of self within relationships (i.e., as indicated by the DoS dimension of I-position) may also influence emotional experiences, particularly among those who experience significant relational preoccupation. It may be inferred that balancing the togetherness-separateness dialectic may coincide with improved emotional outcomes for oneself and for clients.

Finally, there is increasing evidence that developing professionals’ commitment to social justice may be related to intrapersonal and interpersonal capacities for affect regulation (also see Garcia et al. 2015), which highlights the need for training to emphasize the self of the professional; especially given that social justice commitment has emerged as an important ethic for effective helping professionals (e.g., McDowell and Shelton 2002; Sandage et al. 2014). Our results suggest a link between higher levels of insecure attachment experiences (i.e., both adult attachment dimensions) and fusing with others, as well as a link between attachment anxiety and difficulty maintaining an I-position in relationships, which are then connected to a reduced commitment to social justice. Additionally, an underdeveloped sense of self within a relationship may lead to difficulty in identifying and/or holding to one’s values or convictions when such convictions are not supported by close attachment figures. It is possible that cultivating greater balance of the autonomy-connectedness dialectic may relate to enhanced concern about the welfare of others. This may involve a clarification of personal values and convictions (McDowell and Shelton 2002). Clinically, increasing clients’ commitment to social justice may not be a primary goal of therapy. On the other hand, a client’s reduced sense of empathy or caring for others may result in negative relational outcomes. As such, therapists may pay particular attention to signs of fusion and reduced autonomy, particularly for those clients experiencing attachment insecurity.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study sample consisted primarily of European-American graduate students in the context of a Protestant-affiliated university in the mid-west United States. Further research is needed with more ethnically diverse samples in other spiritual and religious contexts and non-religious contexts. Student participants in this study were also from several different graduate programs and future research might investigate potential differences in these variables across fields of study if specific hypotheses could be justified. Some students in our sample were training for ministry vocations, and research has shown clergy to be the most commonly accessed helping profession for mental health problems in the U.S. and, thus, an important population for studies in this area (Wang et al. 2003).

Additionally, other indicators of prosociality or virtuousness and well-being beyond those used in the current study (i.e., dispositional forgiveness, positive emotionality, and social justice commitment) could be used, such as humility, gratitude, empathy, trust, and intimacy. Indicators of spirituality/religiousness could also be used, since spirituality/religiousness has been integrated with both DoS (e.g., Sandage and Jankowski 2010, 2013) and adult attachment (e.g., Pereira et al. 2014; Jankowski and Sandage 2011) in studies of individual health and relational well-being. In addition, even though our conceptual ordering of variables is consistent with existing empirical research, given the correlational nature of the analyses, it could be that attachment security holds potential as an outcome measure for well-being in associations with other indicators of virtue or relational health. For example, Jankowski et al. (2013) found significant positive bivariate associations between dispositional forgiveness and social justice commitment, humility and social justice commitment, and significant negative bivariate associations between forgiveness and depression symptoms, and between humility and depression symptoms. Last, recent research has introduced self-construal (i.e., how one perceives self in relation to others) as a potentially meaningful construct in understanding the DoS-well-being association (Ross and Murdock 2014). Future research could include self-construal along with adult attachment and DoS when studying individual health and social well-being.

References

Arbuckle, J. L. (2006). Amos 7 .0 user’s guide. Chicago: SPSS, Inc.

Barry, R. A., Lakey, B., & Orehek, E. (2007). Links among attachment dimensions, affect, the self, and perceived support for broadly generalized attachment styles and specific bonds. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 340–353. doi:10.1177/0146167206296102.

Bell, D. C. (2009). Attachment without fear. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 1, 177–197.

Benson, P. L., Donahue, M. J., & Erickson, J. A. (1993). The faith maturity scale: Conceptualization, measurement, and empirical validation. In M. L. Lynn & D. O. Moberg (Eds.), Research in the social scientific study of religion (Vol. 5, pp. 1–26). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Blackmore, J. (2013). Social justice in education: A theoretical overview. In B. J. Irby, G. Brown, R. Lara-Alecio, S. Jackson, B. J. Irby, G. Brown, et al. (Eds.), The handbook of educational theories (pp. 1001–1009). Charlotte, NC: IAP Information Age Publishing.

Bowen, M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. New York: Aronson.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). New York: Guilford Press.

Brennan, K. A., & Shaver, P. R. (1995). Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 267–283. doi:10.1177/0146167295213008.

Burnette, J. L., Davis, D. E., Green, J. D., Worthington, E. L, Jr, & Bradfield, E. (2009). Insecure attachment and depressive symptoms: The mediating role of rumination, empathy, and forgiveness. Personality and Individual Difference, 46, 276–280. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.10.016.

Burnette, J. L., Taylor, K. W., Worthington, E. L., & Forsyth, D. R. (2007). Attachment and trait forgiveness: The mediating role of angry rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 1585–1596. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.033.

Byrne, B. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Cohrs, J. C., Christie, D. J., White, M. P., & Das, C. (2013). Contributions of positive psychology to peace: Toward global well-being and resilience. American Psychologist, 68, 590–600.

Erez, A., Mikulincer, M., van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Kroonenberg, P. M. (2008). Attachment, personality, and volunteering: Placing volunteerism in an attachment-theoretical framework. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 64–74. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.07.021.

Garcia, M., Košutić, I., & McDowell, T. (2015). Peace on earth/war at home: The role of emotion regulation in social justice work. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy: An International Forum, 27, 1–20. doi:10.1080/08952833.2015.1005945.

Gillath, O., Shaver, P. R., Mikulincer, M., Nitzberg, R. E., Erez, A., & Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2005). Attachment, caregiving, and volunteering: Placing volunteerism in an attachment theoretical framework. Personal Relationships, 12, 425–446. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2005.00124.x.

Granqvist, P., & Hagekull, B. (2000). Religiosity, adult attachment, and why “singles” are more religious. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 10, 111–123. doi:10.1207/S15327582IJPR1002_04.

Henriques, G., Kleinman, K., & Asselin, C. (2014). The nested model of well-being: A unified approach. Review of General Psychology, 18, 7–18.

Hill, E. W. (2001). Understanding forgiveness as discovery: Implications for marital and family therapy. Contemporary Family Therapy, 23, 369–384. doi:10.1023/A:1013075627064.

Holeman, V. T., Dean, J. B., DeShea, L., & Duba, J. D. (2011). The multidimensional nature of the quest construct forgiveness, spiritual perception, and differentiation of self. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 39, 31–43.

Jankowski, P. J., & Hooper, L. M. (2012). Differentiation of self: A validation study of the Bowen theory construct. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 1, 226–243. doi:10.1037/a0027469.

Jankowski, P. J., & Sandage, S. J. (2011). Meditative prayer, hope, adult attachment, and forgiveness: A proposed model. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 3, 115–131. doi:10.1037/a0021601.

Jankowski, P. J., & Sandage, S. J. (2012). Spiritual dwelling and well-being: The mediating role of differentiation of self in a sample of distressed adults. Mental Health, Religion, and Culture, 15, 417–434. doi:10.1080/13674676.2011.579592.

Jankowski, P. J., & Sandage, S. J. (2014). Attachment to god and dispositional humility: Indirect effect and conditional effects models. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 42, 70–82.

Jankowski, P. J., Sandage, S. J., & Hill, P. C. (2013). Differentiation-based models of forgivingness, mental health and social justice commitment: Mediator effects for differentiation of self and humility. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8, 412–424. doi:10.1080/17439760.2013.820337.

Johnson, S. M. (2004). The practice of emotionally focused couple therapy: Creating connection (2nd ed.). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Jordan, J. V. (2010). Relational-cultural therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Joshanloo, M. (2014). Eastern conceptualizations of happiness: Fundamental differences in Eastern and Western views. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 475–493.

Kerr, M. E., & Bowen, M. (1988). Family evaluation. New York: W. W. Norton.

Košutić, I., & McDowell, T. (2008). Diversity and social justice issues in family therapy literature: A decade review. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy: An International Forum, 20, 142–165. doi:10.1080/08952830802023292.

Krycak, R. C., Murdock, N. L., & Marszalek, J. M. (2012). Differentiation of self, stress, and emotional support as predictors of psychological distress. Contemporary Family Therapy, 34, 495–515. doi:10.1007/s10591-012-9207-5.

Lawler-Row, K. A., Younger, J. W., Piferi, R. L., & Jones, W. H. (2006). The role of adult attachment style in forgiveness following an interpersonal offense. Journal of Counseling and Development, 84, 493–502.

Lin, W. N., Enright, R. D., & Klatt, J. S. (2013). A forgiveness intervention for Taiwanese young adults with insecure attachment. Contemporary Family Therapy, 35, 105–120. doi:10.1007/s10591-012-9218-2.

Lucas, T., Zhdanova, L., Wendorf, C. A., & Alexander, S. (2013). Procedural and distributive justice beliefs for self and others: Multilevel associations with life satisfaction and self-rated health. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 1325–1341.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112–127. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112.

McCullough, M. E., Worthington, E. L., & Rachal, K. C. (1997). Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 321–336. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.2.321.

McDowell, T., & Shelton, D. (2002). Valuing ideas of social justice in MFT curricula. Contemporary Family Therapy, 24, 313–331. doi:10.1023/A:1015351408957.

Merz, E. L., & Roesch, S. C. (2010). Modeling trait and state variation using multilevel factor analysis with PANAS daily diary data. Journal of Research in Personality, 45, 2–9. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2010.11.003.

Mikulincer, M., Gillath, O., Halevy, V., Avihou, N., Avidan, S., & Eshkoli, Nitzan. (2001). Attachment theory and reactions to others’ needs: Evidence that activation of the sense of attachment security promotes empathic responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 1205–1224. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.1205.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford.

Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., Gillath, O., & Nitzberg, R. A. (2005). Attachment, caregiving, and altruism: Boosting attachment security increases compassion and helping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 817–839. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.817.

Murphy, M., Park, J., & Lonsdale, N. (2006). Marriage and family therapy students’ change in multicultural counseling competencies after a diversity course. Contemporary Family Therapy, 28, 303–311. doi:10.1007/s10591-006-9009-8.

Pereira, M. G., Taysi, E., Orcan, F., & Fincham, F. (2014). Attachment, infidelity, and loneliness in college students involved in a romantic relationship: The role of relationship satisfaction, morbidity, and prayer for partner. Contemporary Family Therapy, 36, 333–350. doi:10.1007/s10591-013-9289-8.

Preacher, K. J., & Selig, J. P. (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communications Methods and Measures, 6, 77–98. doi:10.1080/19312458.2012.679848.

Prilleltensky, I. (2012). Wellness as fairness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49, 1–21.

Ross, A. S., & Murdock, N. L. (2014). Differentiation of self and well-being: The moderating effect of self-construal. Contemporary Family Therapy, 36, 485–496. doi:10.1007/s10591-9311-9.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (1998). The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry, 9, 1–28.

Sandage, S. J., & Crabtree, S. (2011). Spiritual pathology and religious coping as predictors of forgiveness. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 1, 1–19. doi:10.1080/13674676.2011.613806.

Sandage, S. J., Crabtree, S., & Schweer, M. (2014). Differentiation of self and social justice commitment mediated by hope. Journal of Counseling and Development, 92, 67–74. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00131.x.

Sandage, S. J., & Jankowski, P. J. (2010). Forgiveness, spiritual instability, mental health symptoms, and well-being: Mediator effects of differentiation of self. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2, 168–180. doi:10.1037/a0019124.

Sandage, S. J., & Jankowski, P. J. (2013). Spirituality, social justice, and intercultural competence: Mediator effects for differentiation of self. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37, 366–374. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.11.003.

Sandage, S. J., & Williamson, I. (2010). Relational spirituality and dispositional forgiveness: A structural equations model. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 38, 255–266.

Schnarch, D. (2009). Intimacy and desire: Awaken the passion in your relationship. New York: Beaufort Books.

Selig, J. P., & Preacher, K. J. (2008). Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects [Computer software]. http://www.quantpsy.org

Shiota, M. N., Keltner, D., & John, O. P. (2006). Positive emotion dispositions differentially associated with big five personality and attachment style. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 61–71. doi:10.1080/17439760500510833.

Skowron, E. A. (2000). The role of differentiation of self in marital adjustment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 229–237. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.47.2.229.

Skowron, E. A., & Dendy, A. K. (2004). Differentiation of self and attachment in adulthood: Relational correlates of effortful control. Contemporary Family Therapy, 26, 337–357. doi:10.1023/B:COFT.0000037919.63750.9d.

Skowron, E. A., Holmes, S. E., & Sabatelli, R. M. (2003). Deconstructing differentiation: Self-regulation, interdependent relating, and well-being in adulthood. Contemporary Family Therapy, 25, 111–129. doi:10.1023/A:1022514306491.

Skowron, E. A., & Schmitt, T. A. (2003). Assessing interpersonal fusion: Reliability and validity of a new DSI fusion with others subscale. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29, 209–222. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01201.x.

Skowron, E. A., Stanley, K. L., & Shapiro, M. D. (2009). A longitudinal perspective on differentiation of self, interpersonal and psychological well-being in young adulthood. Contemporary Family Therapy, 31, 3–18. doi:10.1007/s10591-008-9075-1.

Tasca, G. A., Szadkowski, L., Illing, V., Trinneer, A., Grenon, R., Demidenko, N., & Bissada, H. (2009). Adult attachment, depression, and eating disorder symptoms: The mediating role of affect regulation strategies. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 662–667. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.006.

Thorberg, F. A., & Lyvers, M. (2006). Attachment, fear of intimacy and differentiation of self among clients in substance disorder treatment facilities. Addictive Behaviors, 31(4), 732–737. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.050.

Timm, T., & Keiley, M. K. (2011). The effects of differentiation of self, adult attachment, and sexual communication on sexual and marital satisfaction: A path analysis. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 37, 206–223. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2011.564513.

Wang, P. S., Berglund, P. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2003). Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Human Services Research, 38, 647–673.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Wei, M., Vogel, D. L., Ku, T. Y., & Zakalik, R. A. (2005). Adult attachment, affect regulation, negative mood, and interpersonal problems: The mediating roles of emotional reactivity and emotional cutoff. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 14–24. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.1.14.

Williamson, I., Sandage, S. J., & Lee, R. M. (2007). How social connectedness affects guilt and shame: Mediated by hope and differentiation of self. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 2159–2170. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.

Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52, 69–81.

Wood, N. D., Werner-Wilson, R. J., Parker, T. S., & Perry, M. S. (2012). Exploring the impact of attachment anxiety and avoidance on the perception of couple conflict. Contemporary Family Therapy, 34, 416–428. doi:10.1007/s10591-012-9202-x.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Drs. John O’Regan and Raja David of the Minnesota School of Professional Psychology at Argosy University, Twin Cities, for their invaluable contribution of expertise and guidance in the conceptualization and implementation of this research.

Funding

This project was supported by a grant from the Fetzer Institute (#2266).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hainlen, R.L., Jankowski, P.J., Paine, D.R. et al. Adult Attachment and Well-Being: Dimensions of Differentiation of Self as Mediators. Contemp Fam Ther 38, 172–183 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-015-9359-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-015-9359-1