Abstract

Unlike in breast cancer and melanoma, sentinel lymph node mapping in colon cancer is primarily used as an aid to the pathologist for accurate nodal staging. The study was undertaken to review the incidence of micro-metastasis and its impact on survival when treated with chemotherapy. The study was also undertaken to see if SLNM could guide limited colon resection in early T stage tumor as a paradigm shift. SLNM was done by subserosal injection of a blue dye. SLNs were ultra-staged by multilevel sectioning and remaining Specimen was then examined by conventional method. For the last 245 patients the specimen was divied ex vivo into two segments as segment A containing the tumor bearing portion of the colon and SLNs with attached mesentery, while segment B include distal part of the colon with attached mesentery. Nodal staging was separately examined. Of the 354 Pts, SLNM was successful in 99.9% of Pts with an average no of SLN/ Pt = 2.8 and total nodes 17.8/pt. Survival was directly related negatively with stage and nodal status. Pts with +ve LN did much better with chemotherapy than without chemotherapy. With 245 Pts, specimen A Vs B, no Pts had +ve node in specimen B with −ve LN in specimen A. SLNM results in more node/Pt, more positive node/Pt ,and more micro-metastasis who when treated with chemotherapy survive longer. Limited segmental resection in early T stage is possible when done with guidance by SLNM without compromising biology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRCa) is the third most common cause of cancer-related mortality in the USA. In 2020, the incidence and mortality of the disease are expected to reach 147,950 and 53,200 cases, respectively [1]. Prognosis of colon cancer (CCa) cases is directly related to the TNM stage of the disease. Node-negative patients have better 5-year survival than node-positive disease (70–80% vs. 30–%) [2]. Even after surgical resection in early-stage CCa (stage I and II), recurrent cancer develops in more than 15% of patients within 5 years. Various factors contribute to disease recurrences, including tumor biology, inadequate surgical resection, occult lymph nodes metastases, neurovascular invasion, bowel perforation, and insufficient lymph nodes examination [3,4,5]. Many of these patients may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy; therefore, accurate lymph node status assessment remains a major factor for the use of adjuvant chemotherapy [2].

Assessment of lymph nodes depends on tumor factors such as tumor size, grade,T/N/M stage, tumor location, and the resected specimen size; patient factors such as gender, body habitus, and age; and human factors such as experience of the pathologist and the surgeon [6]. The recommended number of retrieved lymph nodes in CCa patients is 12–15 nodes; however, over 30% of resected specimens in CCa do not achieve this minimum number. In addition, the conventional standard H&E staining of a single section of lymph nodes could miss occult tumor disease [7, 8].

Occult tumor metastases in the lymph nodes can be classified as micro-metastases—where tumor cell groups are between 0.2 mm and 2 mm in diameter—and isolated tumor cells (ITC) where the greatest diameter of the tumor cells is below 0.2 mm. The presence of micro-metastasis can worsen disease survival, with most studies showing a negligible impact of ITC on prognosis [6, 7]. Molecular upstaging is an alternative to enhancing the lymph node assessment and its accuracy in node-negative cases to detect occult tumor metastases [9]. One meta-analyses from 39 studies with a cumulative sample size of 4087 CRCa patients showed that molecular upstaging was associated with poor overall survival and disease-free survival [10].

The “sentinel lymph node” (SLN) has been defined as the first LN with the most direct drainage from a tumor site and has the highest potential to contain metastases when present. The sentinel lymph node mapping (SLNM) technique has been shown to improve positive nodal staging by 11% of patients with CCa, who may benefit from further adjuvant chemotherapy [11]. SLNM has been shown to identify the nodes with the highest risk of metastasis [12]. SLNM is an easily adopted and reproducible technique to identify the few LNs in the drainage pathway which have the highest potential of harboring metastasis [13].

SLNM is the standard of care in breast and melanoma management, as it guides the extent of lymphadenectomy. On the other hand, SLNM in CCa has primarily been used as an aid to the pathologist to identify low-volume metastatic disease. The focused evaluation of SLNs may identify micro-metastasis in at least 15% of N0 patients compared to conventional examination; these patients may benefit from additional chemotherapy [13].

Paradigm shift

Historically gastric CA in Japan presented with advanced T Stage (T3 and T4) in more than 75% of cases, requiring radical gastrectomy. Due to screening upper endoscopy over the last two decades, more than 80% of patients with gastric CA now present with early T stage (Tis, T1 and T2).

Multi-national and multi-institutional studies by Kitagawa, et al. of early-stage gastric CA patients treated by SLNM showed more than 95% patients had node −ve disease. They were treated with laparoscopic wedge resection rather than radical gastrectomy, which was standard before in early gastric CA in Japan. This paradigm shift dramatically reduced morbidity and improved quality of life without compromising survival [14].

Conventional surgery for all CCa patients includes resection of defined segments of colon along with attached segment of mesentery as part of conventional surgery (i.e., right or left hemi- colectomy). As more than 35% of patients with CCa are being diagnosed with T1 or early T2 disease due to screening colonoscopy with < 5% chance of nodal metastasis, the principle of limited resection with SLNM may be applied in early T stage CCa. This may avoid complications of extended hemicolectomy and preserve more length of colon. Hence, the study was undertaken for CCa patients to see if such limited resection could benefit some patients with early T stage disease, as opposed to formal hemicolectomy as a standard for all T-stages over the last 50 years.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of 353 consecutive CCa patients who underwent surgical resection at a single institution was done.

All patients underwent surgery by the same surgical oncologist. Before the operation, the approximate location of the primary tumor was known from colonoscopy results. An exploratory laparotomy was performed to find the extent of the primary tumor and any distant metastases. During initial mobilization of the bowel, attempts were made to minimize dissection of the mesenteric peritoneum. Once isolation of the primary lesion was performed, 1–4 ml of Lymphazurin 1% was injected subserosally by a tuberculin syringe around the primary tumor in a circumferential manner. Occasionally, slightly more than 4 ml of the dye was needed, i.e., in the case of a large primary tumor (>5 cm). Care was used to ensure that there was no injection into the lumen of the bowel.

The first to fourth blue nodes closest to the tumor with the most direct drainage from the lesion were tagged with sutures as “SLN”. They were removed en bloc with the specimen by a standard oncological resection of the primary tumor along with the draining regional LNs and mesentery.

Pathological examination

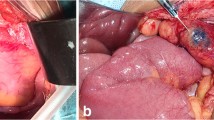

As a standard, SLNs were sectioned grossly at 2- to 3-mm intervals and totally submitted. They were examined pathologically, 4 sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and the fifth with cytokeratin immunostain (AE-1/AE-3). The remainder of the non-SLNs and the primary tumor were examined with standard pathologic methods (Fig. 1).

The decision to limit focused evaluation by multiple sections and cytokeratin immunostain to the SLNs only followed a study by Wiese et al. which analyzed whether such ultra-staging of initially negative non-sentinel lymph nodes (non-SLNs) would increase nodal positivity in CRCa. After ultra-staging of only the SLNs with 4 H&E and one with immunohistochemistry, all negative non-SLNs were also ultra-staged as in SLNs. Out of 200 consecutive patients, only 1% of patients (2 patients) changed from stage II to stage III [15].

Data regarding demographics, tumor staging, SLNM success rate, adjuvant chemotherapy, and survival were documented.

Reflecting the study of limited gastric resection after SLNM by Kitagawa et al. for early-stage gastric CA in Japan, this study was done to evaluate the possible paradigm shift of limiting colon resection for CCa. Of the 245 patients undergoing SLNM for this srudy, the resected colon specimens were surgically divied into 2 groups ex vivo. Specimen A group included the segment of the colon with the primary tumor, and the adjacent portion of the bowel along with the attached segment of mesentery with the feeding vessels and the SLNs tagged with sutures. Specimen B group included the remaining distal part of the colon with attached mesentery outside the field of SLNs. All T stages and N stages were analyzed for each segment, to understand the location of nodal metastasis for each patient (Fig. 2).

Results

A total of 353 consecutive patients were evaluated in the course of the study. The average age was 68.8 years and 48% (n = 171) of the patients were males. The majority of the patients were Caucasians (86%). The average tumor size was 4.34 cm and the average number of retrieved LNs was 17.8. The SLNM success rate was 99.97% with an average number of SLNs of 2.8. The majority of patients had stage III disease (30%), followed by stage I (26%), stage II (24.6%), stage IV (18%), and stage 0 (1.4%) (Table 1).

Overall average survival was 79 months. According to TNM stage, survival data were available for 351 patients, two of the patients lost to follow-up. The longest survival was seen in T1 patients with average of 106 months, followed by Tis patients (100 months), T2 patients (92.4 months), and T3 patients (73.4 months).The shortest average survival was seen in T4 patients with only (40 months). According to N stage, the longest survival was seen in N0 patients with average survival of (89 months), followed by N1 patients (81 months) and N2 patients (47 months). Average survival in M0 patients was 90 months, which is more than triple the average survival in M1 patients (26 months). According to the final staging, the highest average survival was seen in stage 0 patients (100 months) followed by stage I (99 months), stage II (87 months), stage III (85 months), and with the shortest survival in stage IV patients (26 months).[Table 2].

Average survival in LN-negative patients was (89 months) as compared to LN-positive patients (66 months). Average survival correlated negatively with the number of positive LNs. Patients with 1 positive LN had an average survival of (97 months) which is almost double the average survival in patients with ≥3 positive LNs. In patients with LN-positive status, average survival was better in those who received chemotherapy when compared to those who did not receive any form of chemotherapy regardless the number of positive LNs. The longest average survival was seen in patients with 1 positive LN who received chemotherapy (108 months), followed by patients with 2 positive LNs who received chemotherapy (83 months) and patients with ≥3 positive LNs (47 months) who received chemotherapy (54 months). Data from these patients also showed patients with 1 positive LN (most of which were micro-metastasis) who received chemotherapy have much higher average survival (108 months) compared to patients with negative LN status (89 months) (Table 3).

Paradigm shift evaluation

The data for the paradigm shift evaluation were available for 245 consecutive patients. Of these patients, 146 patients (59.6%) had -ve LN status, while 99 patients (40.4%) had +ve LN status (49 patients N1, 50 patients N2). Regarding T stage, there were 82 patients (33.5%) with early T stage CCa (Tis, T1, T2), while 163 patients (66.5%) with advanced T stage CCa (T3, T4). In patients with advanced CCa (163 patients only), 88 patients (54%) had +ve LN status. In early T stage CCa (82 patients only), 11 patients (13.4%) had +ve LN status. Out of these 11 patients, 9 patients (82%) had grade II disease and 2 patients (18%) had grade III disease.

Table 4 shows the LN distribution in specimens A and B. No patients in specimen B had +ve LNs in presence of −ve LNs in specimen A. Only 4 patients in specimen B had +ve LNs when they also had concurrent +ve LNs in specimen A. All these 4 patients had advanced disease with T status (T3, T4), and N status (N2), with average no of +ve LNs of 11.5, and M1 status in 3 pts (Table 5).

Discussion

Sentinel lymph node mapping (SLNM) has been used extensively in the management of early stage of breast cancer and melanoma. This has become the standard of care in many parts of the globe. This has resulted in avoidance of unnecessary nodal dissection in the presence of negative SLNs.

SLNM in colon cancer on the other hand has not been a standard of care, even though it has been used in more than 37 countries, as an aid to the pathologist for better staging by identifying presence of micrometastasis in the SLNs. This study confirms the high success rate (>99%) of SLNM with higher than an average LN yield. (>17LN/PT) and higher (>44%) nodal positivity. This study also confirmed advantage of adjuvant chemotherapy in node-positive patients compared to no chemotherapy, especially the survival was better in patients with 1 LN positive with most of them having micrometastasis compared to patients with negative SLN and no chemotherapy.

In regard to paradigm shift of the extent of colon resection, this study of 245 participants shows the benefit of SLNM in guiding the extent of colon resection in early stage of colon cancer (T1 & T2 stage) This may allow preservation of extra length of colon in early T stage colon tumor without compromising survival and with less complication and may have better quality of life.

In summary, SLNM in colon cancer is highly effective in selection of those patients who may have micrometastasis and should have adjuvant therapy and avoid those patients with no nodal disease from the need of unnecessary chemotherapy. SLNM also may guide limited colon resection in early T stage of colon cancer without compromising survival.

Conclusions

Colorectal cancer remains a major cause of death (>850,000 Pts) globally [1]. SLNM in CCa has evolved over the last two decades throughout the world (>37 countries). SLNM finds more nodes per patient, more +ve nodes per patient, and detects more patients with nodal disease and micro-metastasis than conventional surgery.

Micro-metastasis when undetected and untreated is associated with an increase in cancer recurrence and death [6, 7]. Micro-metastasis when treated with chemotherapy prolongs survival [13]. When SLNs are truly –ve, most patients may be cured without systemic therapy.

It is hypothesized that, as in the paradigm shift for extent of early-stage gastric cancer resection [14], a limited segmental resection with regional lymphadenectomy guided by SLNM may be performed by a limited resection of the length of colon, especially during minimally invasive surgery for early T stage CCa guided by SLNM.

This may allow a decrease in the unnecessary extension of bowel resection, which requires additional dissection and surgical maneuvering, potentially decreasing complications, without compromising the oncologic outcome in early-stage CCa.

Data availability

All patients included in this study are prospectively followed according to the institution IRB protocol organized into Excel spread sheet and data would be available upon reasonable request.

References

Ward E, Sherman R, Henley S, Jemal A, Siegel D, Feuer E et al (2019) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, featuring cancer in men and women age 20–49 years. JNCI 111(12):1279–1297

Ong M, Schofield J (2016) Assessment of lymph node involvement in colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Sur 8(3):179

Weixler B, Warschkow R, Güller U, Zettl A, von Holzen U, Schmied B et al (2016) Isolated tumor cells in stage I & II colon cancer patients are associated with significantly worse disease-free and overall survival. BMC Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2130-7

Protic M, Stojadinovic A, Nissan A, Wainberg Z, Steele S, Chen D et al (2015) Prognostic effect of ultra-staging node-negative colon cancer without adjuvant chemotherapy: a prospective national cancer institute-sponsored clinical trial. J Am Coll Surg 221(3):643–651

Yun H, Kim H, Lee W, Cho Y, Yun S, Chun H (2009) The necessity of chemotherapy in T3N0M0 colon cancer without risk factors. The American Journal of Surgery 198(3):354–358

Jin M, Frankel W (2018) Lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 27(2):401–412

van der Zaag E, Bouma W, Tanis P, Ubbink D, Bemelman W, Buskens C (2012) Systematic review of sentinel lymph node mapping procedure in colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 19(11):3449–3459

Mescoli C, Albertoni L, Pucciarelli S, Giacomelli L, Russo V, Fassan M et al (2012) Isolated tumor cells in regional lymph nodes as relapse predictors in stage I and II colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 30(9):965–971

Nicholl M, Elashoff D, Takeuchi H, Morton D, Hoon D (2011) Molecular upstaging based on paraffin-embedded sentinel lymph nodes. Ann Surg 253(1):116–122

Rahbari N, Bork U, Motschall E, Thorlund K, Büchler M, Koch M et al (2012) Molecular detection of tumor cells in regional lymph nodes is associated with disease recurrence and poor survival in node-negative colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 30(1):60–70

Saha S, Wiese D, Badin J et al (2000) Technical details of sentinel lymph node mapping in colorectal cancer and its impact on staging. Ann Surg Oncol 7:120–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10434-000-0120-z

Sfeclan MC, Vîlcea ID, Barišić G, Mogoantă SŞ, Moraru E, Ciorbagiu MC, Vasile I, Vere CC, Vîlcea AM, Mirea CS (2015) The sentinel lymph node (SLN) significance in colorectal cancer: methods and results. General report. Rom J Morphol Embryol 56(3):943–947 (PMID: 26662126)

Saha S, Elgamal M, Cherry M, Buttar R, Pentapati S, Mukkamala S, Devisetty K, Kaushal S, Alnounou M, Singh T, Grewal S, Eilender D, Arora M, Wiese D (2018) Challenging the conventional treatment of colon cancer by sentinel lymph node mapping and its role of detecting micrometastases for adjuvant chemotherapy. Clin Exp Metastasis 35(5–6):463–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-018-9927-5 (Epub 2018 Aug 16 PMID: 30116938)

Takeuchi H, Kitagawa Y (2015) Sentinel lymph node biopsy in gastric cancer. Cancer J 21(1):21–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/PPO.0000000000000088

Wiese D, Sirop S, Yestrepsky B, Ghanem M, Bassily N, Ng P, Liu W, Quiachon E, Ahsan A, Badin J, Saha S (2010) Ultrastaging of sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) vs non-SLNs in colorectal cancer—do we need both? Am J Surg 199(3):354–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.032

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Presented at the 8th International Cancer Metastasis Congress in San Francisco, CA, USA from October 25–27, 2019 (http://www.cancermetastasis.org). To be published in an upcoming Special Issue of Clinical and Experimental Metastasis: Novel Frontiers in Cancer Metastasis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saha, S., Philimon, B., Efeson, M. et al. The role of sentinel lymph node mapping in colon cancer: detection of micro-metastasis, effect on survival, and driver of a paradigm shift in extent of colon resection. Clin Exp Metastasis 39, 109–115 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-021-10121-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-021-10121-y