Abstract

Despite successful examples of multilevel government leadership on climate change policy, many local officials still face a variety of barriers, including low public support, low resources, and political division. But perhaps most significant is lack of public discussion about climate change. We propose deliberative framing as a strategy to open the silence, bridge political division, identify common and divergent interests and values, and thereby devise collective responses to climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Climate change action is one of the 17 United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), agreed by 193 countries.Footnote 1 Action on this goal includes integration of climate change measures into national policies and planning, improving resilience and adaptive capacity to climate impacts, protection of vulnerable groups and communities, and multiple other targets. Despite overwhelming acceptance of SDGs, the success of global and national climate policies continues to be uncertain, with lower-levels of government leading mitigation and adaptation efforts (Bulkeley 2010; Rabe 2008; Yi, Krause, and Feiock 2017). Many large cities around the world have set carbon reduction targets and participate in networks to share information and resources (Rosenzweig et al. 2010). Despite successful examples and motivating factors, however, local officials still face a variety of barriers. By local, we mean policy responses that take shape at the level of local administrative units (LAU), although our primary focus lies with small towns and medium size cities rather than large urban centers. Many small to medium size cities are not taking action on climate change because there is often less public support, less resources, competing priorities, and thus fewer opportunities for policy development (Bulkeley and Betsill 2013; Wood, Hultquist, and Romsdahl 2014). But perhaps the most significant barrier for LAU is a lack of public discussion about climate change (Marshall 2015; Rickards, Wiseman, and Kashima 2014). For example, although many Americans (71%) believe global warming is already happening, 62% rarely/never discuss the topic with family or friends (Leiserowitz et al. 2017). Additionally, in similar nations (Australia, United Kingdom, Canada) whose economies have high dependence on fossil-energy industries, the topic is so politically polarized that to speak in favor of climate policies can put bureaucrats at risk of losing their job or elected officials of losing the next election and can ostracize individuals from their affiliations among friends and family (McCright et al. 2016; Tranter 2013).

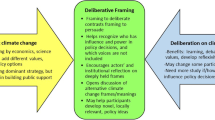

The polarizing effect of the term “climate change” stems not only from the complexity of climate science, but perhaps more so from differences in values and worldviews, which cannot be bridged by more science, information, or education (McCright et al. 2016). Human skills for reasoning are developed more to meet our social needs, rather than individual abilities to understand a problem, such as climate change; we use reason to persuade group members to see our point of view or to justify actions we have taken (Mercier and Sperber 2017). To counter the lack of climate discussion and to address polarized politics, we suggest deliberative framing at a local level. In part, this means encouraging community leaders to initiate discussions about climate change, beginning with a simple question: what do changes in the weather mean to you and your community? We see a need to integrate deliberative democracy, framing, and local policy-making to better understand and manage climate change. Deliberative framing emphasizes the importance of advancing and learning from multiple perspectives and empathizing with others’ values. The objective is to assist communities in examining and weighing trade-offs among various responses in order to advance policy frames that meet local needs while also accounting for global ways of knowing and representing the environment. Deliberative framing provides an avenue for LAU to identify common and divergent interests and values and to devise collective responses to climate change accordingly.

2 Deliberative framing

The practice of public deliberation is everywhere, examples include public participation, deliberative mini-publics, science cafes, climate conversations, and organizations like The National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation (Dietz and Stern 2008). Although definitions of deliberative democracy vary, there is some agreement on core principles: a process of public discussion that is understandable to interested stakeholders, that produces an accountable decision, and that encourages ongoing dialogue on the issues involved (Curato et al. 2017; Dietz and Stern 2008; Gutmann and Thompson 1996; Stevenson and Dryzek 2012). Questions and critiques are raised about legitimacy and effectiveness of process: who should be involved; what does success look like and how do we measure it (Beierle and Cayford 2002; Birnbaum, Bodin, and Sandström 2015; Dietz and Stern 2008; Fischer 2006; Fung and Wright 2003; Hendriks 2012)? Proponents claim that deliberation can play a useful role in situations of value conflict because through discussion, people can identify both common and divergent interests and in doing so propose multiple courses of action which increases the likelihood for stable and long-term decision-making. Experiments in various fields have shown that deliberative forums can influence policy decisions, although impacts vary and may be indirect (Barrett, Vera Schattan, and Wyman 2012; Pogrebinschi and Samuels 2014). Studies show that deliberative experiments have produced valued outcomes for participants and environmental management issues (Dietz, Ostrom, and Stern 2003; Berkes 2007; Beierle and Cayford 2002; Fung and Wright 2003).

Critics of formal public deliberation highlight a variety of drawbacks including questions about power and influence. One key concern lies with the bias of public deliberation towards the interests and practices of certain social groups (Sanders 1997; Young 1997). For instance, Sanders (1997) criticizes deliberative democratic theory for inherent bias against people who are traditionally under-represented and excluded from dialogue and decision-making processes, namely women and racial minorities. Young (1997) argues that social differences must be recognized and included if discussions and decision-making are to be just. Lupia and Norton (2017) echo these criticisms when they state that “deliberation is another way of allocating power” (p.74) because the rules and norms that aim to ensure equality in deliberative forums simply benefit those who already have access and influence. A proposed mechanism in response is to ensure a diversity of participants and multiple forms of reasoning so that varied interests and values are present. Young (1997) argues that social differences can be beneficial in deliberation because the democratic process is “a form of practical reason for conflict resolution and collective problem solving” (p. 400). Building on these points, Mansbridge (2015) describes how second-generation deliberative scholars recognize broader forms of communication including emotion and passion.

There are also methodological and logistical questions about how to scale-up from small experiments, mini-publics, and deliberative polling examples, which involve capacity building for public administrators and citizens, available resources, and time commitments (Curato et al. 2017). Additional challenges may be more political, for example, Fischer (2017) discusses the increasing pressure for action on climate change mitigation as experts continue to emphasize the limited time-frame left before serious, damaging impacts threaten the survival of human society. He argues that technocracy will become an increasingly attractive governance strategy that science and technology experts will advocate in policy-making. Fischer (2017) examines the success, to date, of deliberative forms of governance, including deliberative budgeting, community forest management, the Transition Town movement, and the Global Ecovillage Network; he finds many examples of successful implementation of deliberative practices and concludes that “eco-localism” types of governance will continue to grow, out of necessity in some places, and out of choice in other places. He also argues that these local deliberative governance efforts should be nurtured for their capacity to preserve democratic practices during a potentially painful transition time as the world addresses climate change realities.

Foregrounding framing in deliberative settings provides an avenue to address unequal power relations. Framing refers to the ways in which problems are defined, causes diagnosed, judgments made, and remedies suggested (Entman 1993). Communication inherently and inescapably involves framing by calling attention to some aspects of issues and not others. As cognitive psychologists have long recognized, when presented with uncertain issues, a person’s preferences, opinions, and judgments are not stable but are deeply influenced by the ways in which information is framed (Tversky and Kahneman 1986). Frames are simultaneously individual, in terms of the “mental maps” that inform how people see the world (Guber and Bosso 2012), and collective, in terms of the relatively structured ways in which social and environmental issues are presented for collective decision-making purposes (Dryzek and Lo, 2015). As such, frames are central sites of political power because they play a powerful role in shaping the ways in which people think about and act on policy issues.

Framing to persuade is a common strategy of politicians and environmental communicators that involves presenting messages in a strategic fashion to get people to respond in a pre-determined way (Lakoff 2010). When issues are framed for persuasion, the arguments and courses of action are established in advance and the focus is largely instrumental. By contrast, framing to deliberate seeks to outline and clarify different ways of representing a policy issue so that people can understand the differences among them and potentially come up with innovative solutions that they would not have otherwise imagined (Friedman 2007; Calvert and Warren 2014). Deliberative framing is a central strategy of organizations such as the National Issues Forum and Public Dialogue Consortium which provide documents outlining dominant and alternative policy issues to facilitate an expansive discussion about viable options (Friedman 2007; Kadlec and Friedman 2007). Deliberative framing also helps people become aware of their own assumptions and positions, enabling the possibility of deeper reflection and social learning (Pallett and Chilvers 2013).

Although multiple and conflicting frames are present in any policy discussion, dominant frames typically emerge from political, economic, or scientific elites who have the power and authority to define policy issues in line with their own interests and experiences. Political theorists refer to this as framing effects (Calvert and Warren 2014). If dominant frames appear natural and inevitable rather than contingent and contestable, they can impose significant limitations on deliberation by prematurely closing down discussion of alternative options. Ideas that challenge the interests of dominant institutions and stakeholders can also be “framed out” of discussion in subtle and at times forceful ways.

3 Climate change: From facts to frames

Climate change is a complex policy issue that can be framed in numerous ways (Boykoff 2007; Guber and Bosso 2012; Hulme 2009; Malone 2009). Climate change has been variously approached as a problem of energy, water, agriculture and food, public health, justice, colonization, patriarchy, and capitalism, each with a different way of viewing and responding to the issue. The policy frame most commonly encountered in the media and government policy assumes that economic growth is essential for human welfare and that people can control nature through science and technology (Blue 2016). Privileging the knowledge of scientists, engineers, and economists, this frame emphasizes incremental reforms such as market or technological-based solutions. Another common frame represents climate change as an energy-emission problem that requires mitigation in the form of a new energy system (Guber and Bosso 2012). An increasing number of activists and academics argue for the need to consider alternative approaches including those that foreground radical rather than incremental changes to existing economic, political, and cultural systems (Dawson 2010; Klein 2014).

Evidence suggests that formal public deliberation with climate change tends to favor dominant policy frames and, as such, normalizes extant power structures, institutional assumptions, and social practices (Blue 2016; Pallett and Chilvers 2013; Phillips 2012). This effectively limits democratic engagement by offering a small range of options to participants from the outset. As such, a key challenge for deliberative engagement lies with ensuring that dominant policy frames—particularly those authorized by scientific, economic, and political elites—do not crowd out other ways of understanding and responding to climate change. For example, studies show that reframing climate change in different terms, such as public health, elicits positive responses and may provide support for addressing climate policy actions (Myers et al. 2012; Dryzek and Lo 2015). Deliberative framing can be useful as a way to foster transformation rather than adaptation to existing systems by providing the process and space to assist people in becoming “critically aware of one’s own assumptions (and those of others), the capacity for critical reflection and open-mindedness, and the capacity to take in multiple perspectives and viewpoints, including those that challenge prevailing norms and interests” (O’Brien 2012 p. 673).

4 Employing deliberative framing of climate change at the local level

Although scholars have been examining local climate policies and responses for some time, most of the attention is directed towards large urban centers, neglecting the diverse range of smaller LAU (Wood, Hultquist, and Romsdahl 2014; Hoppe, van der Vegt, and Stegmaier 2016). Local responses to climate change take multiple forms of mitigation and adaptation strategies targeting reduction of climate change impacts and building community resilience. These strategies are shaped by numerous forces and agents including multilevel and transnational networks and policies (Bulkeley 2010). First, LAU face different policy constraints and opportunities than regions and nation-states in which they are located. Differences among and within LAU call for attention to particularity in terms of economic resources, cultural diversity, political organization, and per capita emissions. Adding to uncertainties, the impacts of climate change are highly complex and heterogeneous, calling for ground-up approaches that allow self-organization, and polycentric governing (Ostrom 2009). Given this diversity across and within LAU, different approaches to climate change may need to be deployed depending on the context at hand, as global or national frames of climate policy cannot necessarily be “downloaded” onto local contexts with successful results. Building on these efforts through deliberative framing would allow interested stakeholders to discuss their values, concerns, and understandings of the issue with a goal of developing policies for local climate change management. Local leaders could guide discussions so people understand how frames resonate within local contexts; shifting the well-worn truism “think globally, act locally” to “think locally to act globally.”

Rydin and Pennington (2000) argue that “environmental governance requires decision-making to be rooted in local arenas, without recourse to higher-tier authorities. If local interests can lobby national governments, for financial aid or subsidies, rather than find their own environmental solutions, then there will be little incentive to develop co-operative social relationships at the local scale” (p. 166). Studies have shown a variety of factors increase the likelihood that people will engage in political processes, including education level, occupation, social status, available time and resources, social capital, and living in a smaller community (Dietz and Stern 2008; Verba and Nie 1972; Hays and Kogl 2007). Since the 2008 global recession, LAU have recognized that austerity measures mean they cannot wait for national action or funding on a variety of issues, including climate change (Abels 2014; Mees 2016; Moloney and Fünfgeld 2015; Romsdahl et al. 2017). In response, LAU have developed regional services, collaborations, and strategic plans focused on sustainability (economic and environmental) and they are using deliberative engagement to build public support for these changes (Mees 2016). Across the UK, LAU strategically reframe climate change as sustainability, flood management, and energy savings (Romsdahl et al. 2017). Sustainability and resilience frames are perceived by policymakers as more positive discourse than terminology about climate change impacts and vulnerability; additionally, the lack of firm definitions for such terms is seen as a benefit in the local political arena because it allows diverse ideas to be discussed when addressing complex socio-ecological problems and relationships (Head 2014). In the USA, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, organized by ten northeast states in 2008, reframed the climate change issue in terms of public benefits. Raymond (2016) examines how advocates “emphasized the public ownership of the atmospheric commons and private corporations’ responsibility to pay for their use of it” and argues that this kind of “normative reframing” is significant in the environmental policy process, by helping to explain and predict sudden changes.

Despite climate change denialism in the USA, there is evidence of broad support for government to take action. A recent survey shows 66% of Americans believe the USA should reduce its greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), regardless of what other countries do (Leiserowitz et al. 2016). In order to develop climate policies, we need to build on this type of support. To do so, we need to discuss how climate change will affect people in their lifetime, where they live, and relative to the issues they are concerned about. For example, many Americans say global warming is an agricultural (66%), health (62%), severe weather (65%), or economic (60%) issue (Leiserowitz et al. 2017). These broad topics have different meanings to different people across different localities, but they are examples where deliberation could help identify specific policy frames and highlight how climate change may have direct or indirect impacts on issues that people are most concerned about. Many LAU officials who do talk about climate change are already strategically using other issue frames (Rasmussen, Kirchhoff, and Lemos 2017; Blue and Dale 2016; Romsdahl et al. 2017).

Experiments in deliberation provide insights on how participation can change peoples’ minds and influence policy outcomes. A notable example comes from Australia, where a 4-day public event was organized to examine impacts of deliberation on climate adaptation discourses (Hobson and Niemeyer 2011). Participants were selected through an interview process which aimed to develop a nationally representative sample population; due to recruitment challenges, women and people younger than age 30 were slightly under-represented, while people with higher education degrees were slightly over-represented. Participants included people who held a range of opinions and beliefs about climate change from “self-assured skepticism” to “alarmed defeatism.” Although framing was not a specific objective, discussions about framing emerged. For example, participants discussed the need to develop local leaders to increase grass-roots actions but emphasized that fear and negative framings of climate change should not be used for motivation. The study concludes that deliberation does change participants’ positions. Through the deliberations, they moved closer together in their discourse; afterward, there was less skepticism, more desire for action, and more willingness to act.

Significant progress has also been made in the application of deliberative principles towards “green energy” policies, especially harvesting wind energy. One example of successful application of deliberative polling on wind energy in West Texas is described by Galbraith and Price (2013). The goal of deliberative polling was to learn informed public opinion on renewable energy in the state; since the public had little information on the complex subject, the pollsters (electric utility companies) reasoned that traditional polls would have questionable value. To obtain informed public opinion, a representative sample of citizens was asked to participate in an event where they could receive additional information and ask questions of professionals. The deliberative poll revealed that the exercise changed public opinion on green energy: the median response for a price the public was willing to pay for renewable resources increased from $1.50 to $6.50 (Lehr et al. 2003). The researchers who organized the deliberation, noted: “Taken together, renewables and efficiency are clearly preferred by most customers after the event, while coal, natural gas, and power purchases are less preferred” (Lehr et al. 2003 p. 5). Results of the deliberative polling moved the state of Texas to design an impressive renewable energy policy with a higher use of wind power generation. A similar example was provided by MacArthur (2016) who discussed a deliberative polling event on renewables organized in Nova Scotia, Canada in 2004, which led to a significant shift in public opinion towards renewable energy, despite its higher cost.

In Alberta, Canada, a university-community research partnership—Alberta Climate Dialogue—organized three formal deliberation events to discuss climate-related issues in the province (Blue and Dale 2016). Overall, deliberative framing was not taken centrally as practitioners and researchers concentrated their efforts on dominant frames of climate change at provincial and large urban levels, namely, by examining the intersections between climate and energy with an attendant focus on mitigation. One event (Water in a Changing Climate) engaged smaller urban centers and incorporated deliberative framing into the participatory design from the outset to broaden the discussion beyond a focus on energy and mitigation to include water and adaptation. This approach brought discussions about GHG emissions and rising global temperatures into a local context, enabling participants to grapple with how climate change intersects with issues such as social inequality and land use changes.

Although these examples are drawn from the Global North, studies from other regions also provide insights. An example of framing comes from the United Nations supported REDD+ program implementation of CO2 emissions reduction, which uses international funding for forest protection. In small communities in Nepal, power and influence among competing national and international actors has overshadowed local concerns in initial framing of REDD+ implementation, despite a long history of local level forest policy. In situations like this, open, transparent dialogue can help shift framing from global interests to local livelihoods, confirming that mitigation efforts are implemented and provide local co-benefits (Bastakoti and Davidsen 2017). Although not specific to climate change, two other examples show success in deliberative outcomes. Deliberative planning was successfully used in Kerlala, India to develop 5-year plans in the mid-1990s, which were then accepted or rejected by votes in village meetings (Fischer 2006). Final plans were forwarded to national government for inclusion in overall development planning; despite successfully including women and being adapted and reproduced in hundreds of LAU in India, political party opposition eliminated these deliberative activities, although discussions are attempting to find a way to revive them (Fischer 2017). In Brazil, the Porto Alegre participatory budgeting model has implemented local deliberative methods since the 1980s for planning and policy issues including flooding, waste removal, road building, and even reconstruction of an entire neighborhood using strict environmental standards (Baiocchi 2003; Fischer 2017; Wampler 2010); and this deliberative model has spread to over 1500 cities in other nations (Ganuza and Baiocchi 2012).

Deliberative framing techniques are also emerging in the study of climate justice (Schlosberg and Collins 2014). As nations and LAUs make plans for developing green energy, or a green economy, to mitigate climate emissions, global labor unions have often been left out of the discussion, prompting demands for “just transitions” away from fossil fuels (Stevis and Felli 2015). Regarding climate adaptation, studies are examining “just transformations” to help define what this means, whether such transformations can be proactive, ethical, sustainable, deliberative, and participatory (Schlosberg, Collins, and Niemeyer 2017; Pelling, O’Brien, and Matyas 2015; O’Brien 2012). Deliberative framing could assist in giving communities more voice in planning, such as deciding whether or not to adapt to climate changes (Cinner et al. 2018), as well as examining questions of power and influence (Van Lieshout et al. 2017; Morrison et al. 2017).

5 Conclusion

Although deliberative processes, framing strategies, and local policies to manage climate change are not new ideas (Dietz, Ostrom, and Stern 2003), the need to combine them into an integrated approach is acute. Despite unprecedented support for the Paris Climate Agreement, climate scientists warn that we are running out of time (Jackson et al. 2017) and the current emission reduction pledges by each signatory country will not be enough to prevent 2 °C warming (UNEP 2016). Meanwhile, the first draft of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C shows that an even more challenging goal is required to control high risks for society and environment.Footnote 2 In countries like the USA and Australia, where national leaders continue to express skepticism on the need to develop climate policies and outright denial of climate science consensus, providing opportunities for stakeholders and citizens to examine various frames of climate change can provide an innovative avenue to develop practical solutions. In countries with strong national leadership on climate policy, deliberative framing can connect high-level recommendations for addressing climate change with insights and values of local stakeholders. Challenges to deliberative framing are similar to other public participation efforts and could include resistance to public involvement from politicians and public administrators; lack of time, interest, and civic experience in the public; inequities of power and influence; and lack of resources such as funding, staff, and training. As more cities, states, and businesses pledge to uphold the Paris Climate Agreement, resources can be developed to help address these participation challenges. Taking into account, local frames of environmental change can help open discussion and lead to context and place sensitive policies that resonate with local values and address regional concerns.

Despite an apparent need for deliberative framing of climate change discourse, especially considering the challenges of the post-1.5 °C warming world outlined by the IPCC, examples are few and research is sparse. But numerous examples of successful application of deliberative framing to more general issues of environmental protection and sustainability give hope for equal potential of deliberative framing in climate change policies. More research is needed to develop and implement deliberative framing in practice, including identifying examples where deliberation has influenced policy outcomes and examining different means to encourage or institutionalize collaboration between scholars and LAU decision-makers to facilitate transitions to more environmentally sustainable and socially just futures.

Notes

See the United Nations Division for Sustainable Development webpage: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org

See the draft report- http://www.ipcc.ch/report/sr15

References

Abels M (2014) Strategic alignment for the new normal: collaboration, sustainability, and deliberation in local government across boundaries. State Local Gov Rev 46(3):211–218

Baiocchi G (2003) Participation, activism, and politics: the Porto Alegre experiment. In: Fung A, Wright EO (eds) Deepening democracy. Verso, New York

Barrett, Gregory, P. Coelho Vera Schattan, and Miriam Wyman. 2012. Assessing the policy impacts of deliberative civic engagement: comparing engagement in health policy practices in Canada and Brazil. In Democracy in Motion. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bastakoti RR, Davidsen C (2017) Framing REDD at national level: actors and discourse around Nepal’s policy debate. Forests 8(3):57

Beierle, Thomas C. and Jerry Cayford. 2002. Democracy in Practice: Public Participation in Environmental Decisions Resources for the Future.

Berkes F (2007) Community-based conservation in a globalized world. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104(39):15188–15193

Birnbaum S, Bodin Ö, Sandström A (2015) Tracing the sources of legitimacy: the impact of deliberation in participatory natural resource management. Policy Sci 48(4):443–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-015-9230-0

Blue G (2016) Framing climate change for public deliberation: what role for interpretive social sciences and humanities? J Environ Policy Plan 18(1):67–84

Blue G, Dale J (2016) Framing and power in public deliberation with climate change: critical reflections on the role of deliberative practitioners. J Public Deliberation 12(1)

Boykoff MT (2007) From convergence to contention: United States mass media representations of anthropogenic climate change science. Trans Inst Br Geogr 32(4):477–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5.

Bulkeley H (2010) Cities and the governing of climate change. Annu Rev Environ Resour 35:229–253

Bulkeley H, Betsill MM (2013) Revisiting the urban politics of climate change. Environ Polit 22(1):136–154

Calvert A, Warren ME (2014) Deliberative democracy and framing effects: why frames are a problem and how deliberative mini-publics might overcome them. In: Grönlund K, Bächtiger A, Setälä M (eds) Deliberative mini-publics: involving citizens in the democratic process. ECPR Press, Colchester, UK, pp 203–224

Cinner JE, Neil Adger W, Allison EH, Barnes ML, Brown K, Cohen PJ, Gelcich S et al (2018) Building adaptive capacity to climate change in tropical coastal communities. Nat Clim Chang 8(2):117. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-017-0065-x

Curato N, Dryzek JS, Ercan SA, Hendriks CM, Niemeyer S (2017) Twelve key findings in deliberative democracy research. Daedalus 146(3):28–38

Dawson A (2010) Climate justice: the emerging movement against green capitalism. South Atlantic Quarterly 109(2):313–338

Dietz T, Stern PC (eds) (2008) Public participation in environmental assessment and decision making. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Dietz T, Ostrom E, Stern PC (2003) The struggle to govern the commons. Science 302(5652):1907–1912

Dryzek JS, Lo AY (2015) Reason and rhetoric in climate communication. Environ Polit 24(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2014.961273

Entman RM (1993) Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun 43(4):51 58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Fischer F (2006) Participatory governance as deliberative empowerment: the cultural politics of discursive space. Am Rev Public Admin 36(1):19–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074005282582

Fischer F (2017) Climate crisis and the democratic prospect: participatory governance in sustainable communities. Oxford University Press

Friedman, Will. 2007. Reframing Framing. Occasional Paper 1. Center for Advances in Public Engagement. Available at: https://apha.confex.com/recording/apha/138am/pdf/free/4db77adf5df9fff0d3caf5cafe28f496/paper227186_3.pdf

Fung, Archon and Erik Olin Wright. 2003. Deepening Democracy: Institutional Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance. Vol. 4 Verso.

Galbraith, Kate and Asher Price. 2013. The great Texas wind rush: how George Bush, Ann Richards, and a bunch of tinkerers helped the oil and gas state win the race to wind power University of Texas Press

Ganuza E, Baiocchi G (2012) The power of ambiguity: how participatory budgeting travels the globe. J Public Deliberation 8(2)

Guber, Deborah Lynn and Christopher I. Bosso. 2012. Issue framing, agenda setting, and environmental discourse. S. Kamieniecki and M. Kraft, the Oxford Handbook of US Environmental Policy: 437–460.

Gutmann A, Thompson DF (1996) Democracy and disagreement. Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass

Hays RA, Kogl AM (2007) Neighborhood attachment, social capital building, and political participation: a case study of low-and moderate-income residents of waterloo, Iowa. J Urban Aff 29(2):181–205

Head BW (2014) Evidence, uncertainty, and wicked problems in climate change decision making in Australia. Environ Plann C Gov Policy 32(4):663–679

Hendriks CM (2012) The politics of public deliberation: citizen engagement and interest advocacy. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Hobson K, Niemeyer S (2011) Public responses to climate change: the role of deliberation in building capacity for adaptive action. Glob Environ Chang 21(3):957–971

Hoppe T, van der Vegt A, Stegmaier P (2016) Presenting a framework to analyze local climate policy and action in small and medium-sized cities. Sustainability 8(9):847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090847

Hulme M (2009) Why we disagree about climate change. Cambridge University Press

Jackson RB, Le Qur C, Andrew RM, Canadell JG, Peters GP, Roy J, Wu L (2017) Warning signs for stabilizing global CO2 emissions. Environ Res Lett 12(11):110202

Kadlec A, Friedman W (2007) Deliberative democracy and the problem of power. J Public Deliberation 3(1)

Klein N (2014) This changes everything: capitalism V. The climate. Simon & Schuster, New York

Lakoff G (2010) Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environ Commun 4(1):70–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524030903529749

Lehr, R. L., W. Guild, D. L. Thomas, and B. G. Swezey. 2003. Listening to Customers: How Deliberative Polling Helped Build 1,000 MW of New Renewable Energy Projects in Texas. Golden, CO: USDOE. doi:https://doi.org/10.2172/15003900.

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C, Rosenthal S, Cutler M (2016) Politics and global warming, November 2016. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, New Haven, CT

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C, Rosenthal S, Cutler M, Kotcher J (2017) Climate change in the American mind: October 2017. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, New Haven, CT

Lupia A, Norton A (2017) Inequality is always in the room: language & power in deliberative democracy. Daedalus 146(3):64–76. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00447

MacArthur JL (2016) Challenging public engagement: participation, deliberation and power in renewable energy policy. J Environ Stud Sci 6(3):631–640

Malone, Elizabeth L. 2009. Debating climate change: pathways through argument to agreement. Routledge.

Mansbridge J (2015) A minimalist definition of deliberation. In: Heller P, Rao V (eds) Deliberation and development: rethinking the role of voice and collective action in unequal societies. World Bank, Washington DC, pp 27–50

Marshall, George. 2015. Don’t even think about it: why our brains are wired to ignore climate change. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

McCright AM, Marquart-Pyatt ST, Shwom RL, Brechin SR, Allen S (2016) Ideology, capitalism, and climate: explaining public views about climate change in the United States. Energy Res Soc Sci 21:180–189

Mees H (2016) Local governments in the driving seat? A comparative analysis of public and private responsibilities for adaptation to climate change in European and North-American cities. J Environ Policy Plan:1–17

Mercier H, Sperber D (2017) The enigma of reason. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Moloney S, Fünfgeld H (2015) Emergent processes of adaptive capacity building: local government climate change alliances and networks in Melbourne. Urban Climate 14:30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2015.06.009

Morrison TH, Neil Adger W, Brown K, Lemos MC, Huitema D, Hughes TP (2017) Mitigation and adaptation in polycentric systems: sources of power in the pursuit of collective goals. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 8(5)

Myers TA, Nisbet MC, Maibach EW, Leiserowitz AA (2012) A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. Clim Chang 113(3–4):1105–1112

O’Brien K (2012) Global environmental change II: from adaptation to deliberate transformation. Prog Hum Geogr 36(5):667–676

Ostrom, Elinor. 2009. A Polycentric Approach for Coping with Climate Change. Rochester, NY: World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5095.

Pallett H, Chilvers J (2013) A decade of learning about publics, participation, and climate change: institutionalising reflexivity? Environ Plan A 45(5):1162–1183

Pelling M, O’Brien K, Matyas D (2015) Adaptation and transformation. Clim Chang 133(1):113–127

Phillips, Louise. 2012. Communicating about climate change in a citizen consultation: dynamics of exclusion and inclusion. In Performing public participation in science and environment communication, edited by Louise Phillips, Anna Carvalho and Julie Doyle. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pogrebinschi T, Samuels D (2014) The impact of participatory democracy: evidence from Brazil’s National Public Policy Conferences. Comp Polit 46(3):313–332

Rabe BG (2008) States on steroids: the intergovernmental odyssey of American climate policy. Rev Policy Res 25(2):105–128

Rasmussen LV, Kirchhoff CJ, Lemos MC (2017) Adaptation by stealth: climate information use in the Great Lakes region across scales. Clim Chang:1–15

Raymond, Leigh. 2016. Reclaiming the atmospheric commons: the regional greenhouse gas initiative and a new model of emissions trading MIT Press.

Rickards L, Wiseman J, Kashima Y (2014) Barriers to effective climate change mitigation: the case of senior government and business decision makers. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 5(6):753–773

Romsdahl, Rebecca J., Andrei Kirilenko, Robert S. Wood, and Andy Hultquist. 2017. Assessing national discourse and local governance framing of climate change for adaptation in the United Kingdom. Environmental Communication: 1–22.

Rosenzweig C, Solecki W, Hammer SA, Mehrotra S (2010) Cities lead the way in climate-change action. Nature 467(7318):909–911

Rydin Y, Pennington M (2000) Public participation and local environmental planning: the collective action problem and the potential of social capital. Local Environ 5(2):153–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830050009328

Sanders LM (1997) Against deliberation. Polit Theo 25(3):347–376

Schlosberg D, Collins LB (2014) From environmental to climate justice: climate change and the discourse of environmental justice. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 5(3):359–374

Schlosberg D, Collins LB, Niemeyer S (2017) Adaptation policy and community discourse: risk, vulnerability, and just transformation. Environ Polit 26(3):413–437

Stevenson H, Dryzek JS (2012) The discursive democratisation of global climate governance. Environ Polit 21(2):189–210

Stevis D, Felli R (2015) Global labour unions and just transition to a green economy. Int Environ Agreements: Polit, Law Econ 15(1):29–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9266-1

Tranter B (2013) The great divide: political candidate and voter polarisation over global warming in Australia. Aust J Polit Hist 59(3):397–413

Tversky, Amos and Daniel Kahneman. 1986. Rational choice and the framing of decisions. J Bus: S278

UNEP. 2016. The Emissions Gap Report 2016. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme.

Van Lieshout M, Dewulf A, Aarts N, Termeer C (2017) The power to frame the scale? Analysing scalar politics over, in and of a deliberative governance process. J Environ Policy Plan 19(5):550–573

Verba S, Nie NH (1972) Participation in America. Harper & Row, New York

Wampler, Brian. 2010. Participatory budgeting in Brazil: contestation, cooperation, and accountability. University Park: Penn State press.

Wood RS, Hultquist A, Romsdahl RJ (2014) An examination of local climate change policies in the Great Plains. Rev Policy Res 31(6):529–554

Yi H, Krause RM, Feiock RC (2017) Back-pedaling or continuing quietly? Assessing the impact of ICLEI membership termination on cities’ sustainability actions. Environ Polit 26(1):138–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2016.1244968

Young IM (1997) Difference as a resource for democratic communication. In: Bohman JF, Vol WR (eds) Deliberative democracy: essays on reason and politics. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, p 399

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Romsdahl, R., Blue, G. & Kirilenko, A. Action on climate change requires deliberative framing at local governance level. Climatic Change 149, 277–287 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2240-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2240-0