Abstract

Steadily rising mean and extreme temperatures as a result of climate change will likely impact the air transportation system over the coming decades. As air temperatures rise at constant pressure, air density declines, resulting in less lift generation by an aircraft wing at a given airspeed and potentially imposing a weight restriction on departing aircraft. This study presents a general model to project future weight restrictions across a fleet of aircraft with different takeoff weights operating at a variety of airports. We construct performance models for five common commercial aircraft and 19 major airports around the world and use projections of daily temperatures from the CMIP5 model suite under the RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 emissions scenarios to calculate required hourly weight restriction. We find that on average, 10–30% of annual flights departing at the time of daily maximum temperature may require some weight restriction below their maximum takeoff weights, with mean restrictions ranging from 0.5 to 4% of total aircraft payload and fuel capacity by mid- to late century. Both mid-sized and large aircraft are affected, and airports with short runways and high temperatures, or those at high elevations, will see the largest impacts. Our results suggest that weight restriction may impose a non-trivial cost on airlines and impact aviation operations around the world and that adaptation may be required in aircraft design, airline schedules, and/or runway lengths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Global mean surface temperatures have increased by approximately 1 °C above pre-industrial levels, with most of that change occurring after 1980 (Walsh et al. 2014). As air temperature increases at constant pressure, air expands and becomes less dense. The lift generated by an airplane wing is a function of the mass flux across the wing surface; at lower air densities, a higher airspeed is required to produce a given lifting force (Anderson 2015). For a given runway and aircraft, there is a temperature threshold above which takeoff at the aircraft’s maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) is impossible due to runway length or performance limits on tire speed or braking energy. Above this threshold temperature, a weight restriction—entailing the removal of passengers, cargo, and fuel—must be imposed to permit takeoff (Coffel and Horton 2015, 2016; Hane 2015).

Weather is a leading cause of disruption to flight operations (Lan et al. 2006; Koetse and Rietveld 2009), either through direct impacts on airport capacity and flight routes or through cascading delays across the aviation system (Fleurquin et al. 2013). However, the study of the potential impacts of climate change on aviation is relatively recent (Thompson 2016). Prior work has suggested that both turbulence (Williams and Joshi 2013; Williams 2017) and trans-Atlantic flight times (Williams 2016) may increase due to a strengthening and shifting mid-latitude jet stream. Climate change may also result in more extreme precipitation events (O’Gorman and Schneider 2009; Kharin et al. 2007), altered mid-latitude storm tracks (Yin 2005; Coumou et al. 2015), and changes in hurricane frequency and intensity (Knutson et al. 2010; Webster et al. 2005), among other disruptions to prevailing weather patterns. Sea level rise is also likely to threaten low-lying coastal airports around the world (Hinkel et al. 2014; Parris et al. 2012; Burbidge 2016). Little work has explored these potential risks in detail in the context of the aviation sector, and they present fertile ground for future research.

This study focuses on one potential impact of climate change: an increase in weight restriction due to higher temperatures. The warming resulting from current climate change (~1 °C) has raised the mean airport density altitude (i.e., the altitude associated with air at a given pressure at standard atmospheric conditions) by approximately 100 ft, and expected additional warming of 1–3 °C by the end of the century (Collins et al. 2013) will result in further increases of additional hundreds of feet. Prior work has shown that the frequency of days on which a Boeing 737-800 requires weight restriction is likely to increase by 100–300% at several airports in the USA in the coming decades (Coffel and Horton 2015). We expand on these results by building performance models for five common commercial aircraft, the Boeing 737-800, Airbus A320, Boeing 787-8, Boeing 777-300, and Airbus A380, and calculating the change in the magnitude and frequency of weight restriction events at 19 airports (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for airport and aircraft information). Air traffic is heavily concentrated in a relatively small number of cities, and these selected locations represent the most common climates, elevations, and runway conditions found at the world’s busiest airports. We then calculate weight restriction at a variety of takeoff weights (TOWs) in both historical and future climate conditions. This analysis demonstrates a method which could be combined with aviation industry operational data to dynamically predict the weight restriction burden for an airline, taking into account fleets of diverse aircraft and daily schedules at different airports.

We project future daily airport temperatures using 27 general circulation models (GCMs) from the CMIP5 (Taylor et al. 2012) model suite under both the RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 emissions scenarios (Moss et al. 2010), using the single grid cell that includes each selected airport. We identify and correct several sources of GCM temperature bias using airport station observations from the NOAA-NCEI Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN) (see Supplementary methods). While global mean temperatures are projected to rise by 2–4 °C by 2100 relative to pre-industrial times, changes over land will be larger (Collins et al. 2013; Karl et al. 2015). Changes in extremes may be larger still, with annual maximum airport temperatures projected to increase by 4–8 °C (Horton et al. 2015), resulting in substantial fractions of the year being spent above the historical annual maximum temperature, especially in the tropics where variability is lower (Mora et al. 2013). The frequency and severity of extreme heat events have already increased due to climate change (Stott et al. 2004; Dole et al. 2011), and future mean warming and potential changes in temperature variability (Horton et al. 2015; Horton et al. 2016; Kodra and Ganguly 2014; Schär et al. 2004) are very likely to further enhance the risk of unprecedented heat waves.

We use aircraft performance data from publicly available “Airplane characteristics for airport planning” documents which are produced by manufacturers for all commercial aircraft types (Boeing 2013). These documents contain charts relating TOW, airport elevation, and air temperature to required takeoff runway length. Using these data, we fit three-dimensional surfaces relating temperature and TOW to required takeoff runway length for each aircraft type and airport elevation; Supplementary Figure 5 shows fitted surfaces and weight restriction characteristics. Using the appropriate surface for each aircraft and airport, weight restriction can be calculated at any air temperature and departure weight (see Supplementary methods).

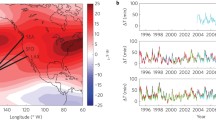

The aviation system, including aircraft and ground operations, has been developed largely based on the climate background of the 1920–1970 period. As temperatures begin to regularly exceed historical bounds, a variety of impacts are likely, from increased weight restrictions to a higher risk of heat stress for outdoor airport workers (Sherwood and Huber 2010; Pal and Eltahir 2015). Figure 1 shows historical and projected annual maximum temperature trends as well as the projected mean number of days per year that exceed the historical average annual maximum temperature at two selected airports, New York’s LaGuardia Airport (LGA) and Dubai, UAE (DXB) under the RCP 4.5 and 8.5 scenarios (see Supplementary Figure 6 for projections at all 19 airports). Rising temperatures will result in rapid increases in the number of days that exceed the historical annual maximum temperature (Hansen et al. 2012); in most cities, this frequency may rise to between 10 and 50 days per year by 2060–2080.

Left column historical and projected annual maximum temperatures at New York’s LaGuardia Airport (LGA) and Dubai (DXB). The thick black line shows the station data, and the green line is the bias-corrected multi-GCM mean. The blue line shows the bias-corrected multi-GCM mean projections under RCP 4.5 and the red line those under RCP 8.5. The shaded regions show ±1 standard deviation across the 27 GCMs, and the dashed gray lines show the linear temperature trends. The thick horizontal dashed black line shows the historical annual maximum temperature based on historical GCM data. Right column the mean number of days per year that exceeds the historical annual maximum temperature under the RCP 4.5 (blue) and RCP 8.5 (red) emissions scenarios. Shaded regions show ±1 standard deviation across the 27 GCMs

Weight restriction can be partitioned into payload reduction (i.e., passengers and/or cargo) and fuel weight reduction. When payload is reduced, less fuel is required to carry that payload, and less still is required to carry that reduced fuel load. Thus, the required payload reduction is less than the total weight restriction. We use a model of aircraft performance (EUROCONTROL 2004) to estimate the mean partitioning of a weight restriction for a Boeing 737-800 to be 83% payload and 17% fuel (see Supplementary methods). This partitioning ratio will vary somewhat for different aircraft types and flight lengths, and more exact values could be computed in future research. Using this partitioning, we calculate required payload reduction for all selected aircraft/airport combinations.

Because air traffic volume varies across airports and may change in the future, we compute weight restriction statistics as if there were one takeoff of each aircraft type during each of the 24 h in every day across all airports. In Fig. 2, we show for several airport/aircraft pairs (see Supplementary Figure 7 for full results) the mean payload reduction at the time of the daily maximum temperature on all days requiring some weight restriction from MTOW (Fig. 2). Figure 2 shows the change in the number of days per year exceeding a specified weight restriction threshold, and Fig. 2 shows the change in the number of days per year experiencing various levels of weight restriction. The changes in mean payload shown in Fig. 2 vary considerably, but most aircraft/airport pairs see 5–10% increases in payload reduction. Large changes are seen in the frequency of particular levels of weight restriction (Fig. 2), with increases by a factor of 1.5–4 common by 2060–2080; the weight restriction threshold with the maximum frequency change is shown.

Weight restriction statistics for selected aircraft/airport pairs. The left panels show the mean payload reduction on days requiring weight restriction; the black bars indicate the middle 99.3%, and red crosses indicate outliers. The middle column shows the mean number of days per year that require at least the specified payload restriction threshold; the green shaded region shows ±1 standard deviation across all 27 GCMs. The third column shows the change in the number of days per year requiring different amounts of payload reduction; the error bars show ±1 standard deviation across all 27 GCMs. All projections are made using a combination of both the RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 emissions scenarios; weight restriction projections under both scenarios are combined into one distribution, showing the full range of plausible future outcomes

Weight restriction is heavily dependent on TOW. If a flight is scheduled to depart well below its MTOW, weight restriction will likely not be needed, even at high temperatures. The distribution of TOWs depends on the specifics of airline operations including route distance, cargo and passenger loads, and fuel reserves and is difficult to estimate. Instead, we model weight restriction at TOW intervals spaced between each aircraft’s operating empty weight (OEW, the weight of the airframe with no payload and limited fuel) and MTOW. Figure 3 shows weight restriction calculated at the time of the daily maximum temperature. The left panels show the percentage of flights requiring some restriction, and the right panels show the restriction magnitude as a percentage of total fuel and payload capacity (see Supplementary Figure 2 for mean results across all hours of the day). Both panels show the historical period (1985–2005) and RCP 8.5 in 2060–2080. Climate-related increases in the percentage of flights requiring some weight restriction range from 1 to 10 percentage points, with declines in total payload and fuel capacity of 0.5–1.5 percentage points. A small change in the total aircraft fuel and payload weight represents a large decrease in capacity when aggregated across an airline’s fleet. For example, a 0.5% decrease from MTOW for a Boeing 737-800 equates to about 722 lb, or three passengers (see Supplementary methods) use the airline-standard 220 lb passenger mean weight. For a normal aircraft configuration of approximately 160 passengers, this is nearly 2% of passenger capacity. Such a decrease can have a substantial impact on airline costs.

Weight restriction as a function of TOW in the historical period (blue, 1985–2005) and the future (red, 2060–2080) under RCP 8.5. Weight is restriction calculated at the time of highest daily air temperature at each of the 19 selected airports and then averaged. The left column shows the percentage of flights with some weight restriction, and the right column shows the restriction as a percentage of total fuel and payload capacity. The shaded region shows ±1 standard deviation across 27 GCMs

While the projected change in weight restriction is relatively consistent across aircraft, the total impact of restriction varies. The large Boeing 777-300 and Boeing 787-8 are projected to experience the greatest impacts from weight restriction; for an aircraft departing near MTOW, by mid- to late century, total fuel and payload capacity may be reduced by 3–5% with 30–40% of flights experiencing some restriction. The Airbus A320 and Boeing 737-800 are less impacted; when departing near MTOW, approximately 5–10% of flights may experience some restriction, sacrificing, on average, 0.5% of their fuel and payload capacity. This is due in part to aircraft design characteristics as well as the fact that most of the world’s commercial airports (and those simulated here) have far longer runways than are required by these mid-sized aircraft, even at high temperatures. The A380 is also expected to experience little weight restriction except at extremely high air temperatures, in part due to its exclusive operation at large airports.

The weight restriction burden varies significantly between airports (see Supplementary Figures 3 and 4 for statistics on all selected airports). At New York’s LGA, a Boeing 737-800 near its MTOW may be weight-restricted approximately 50% of the time when departing at the time of the daily highest temperature and see weight reductions of close to 3.5% of fuel and payload capacity. Similarly, a Boeing 777-300 near MTOW departing from Dubai (DXB) at the time of the daily highest temperature may be weight-restricted about 55% of the time, with weight reductions of up to 6.5% of fuel and payload capacity. The averages over all 19 airports shown in Fig. 3 are lower, as they demonstrate the system-wide impact of weight restriction, including airports which are minimally affected such as London (LHR), Paris (CDG), and New York (JFK).

Technological change, including improvements in engine performance and airframe efficiency, will likely ameliorate the effects of rising temperatures to some degree. In addition, the vast majority of weight restriction will occur near the time of highest temperature; in some locations, it may prove feasible to reschedule some flights, especially those with high TOWs, to cooler hours of the day (this is already done at some airports (ICAO 2016)). Airports could also lengthen runways, although such projects are expensive and politically difficult. However, even with adaptation, potentially including new aircraft designs, takeoff performance will still likely be lower than it would have been given no climate change due to both the effects of reduced air density and degraded engine performance and thrust at higher temperatures. This fact is true of all climate impacts: even if they can be adapted to, they still have a cost. A variety of climate impacts on the aviation industry are likely to occur in the coming decades, and the sooner climate change is incorporated into mid- and long-range plans, the more effective adaptation efforts can be.

References

Anderson JD (2015) Introduction to flight. McGraw-Hill Education, New York

Boeing (2013). 737 airplane characteristics for airport planning

Burbidge R (2016) Adapting European airports to a changing climate. Transp Res Procedia 14:14–23

Coffel E, Horton R (2015) Climate change and the impact of extreme temperatures on aviation. Weather Clim Soc 7:94–102

Coffel ED, Horton RM (2016) Reply to ‘“Comment on ‘Climate change and the impact of extreme temperatures on aviation’”’. AMS Weather Clim Soc 8:207–208

Collins, M. et al., (2013) in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Working Group I Contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) (Cambridge University Press, New York) (eds. Stocker, T. F. et al.) (Cambridge University Press)

Coumou D, Lehmann J, Beckmann J (2015) The weakening summer circulation in the Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes. Science 348(80):324–327

Dole R et al (2011) Was there a basis for anticipating the 2010 Russian heat wave? Geophys Res Lett 38

EUROCONTROL (2004). Experimental centre. User manual for the Base of Aircraft Data (BADA)

Fleurquin P, Ramasco JJ, Eguiluz VM (2013) Systemic delay propagation in the US airport network. Sci Rep 3:1159

Hane FT (2015) Comment on ‘Climate change and the impact of extreme temperatures on aviation’. Weather Clim Soc 8:205–206

Hansen J, Sato M, Ruedy R (2012) Perception of climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:E2415–E2423

Hinkel J et al (2014) Coastal flood damage and adaptation costs under 21st century sea-level rise. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:3292–3297

Horton RM, Coffel ED, Winter JM, Bader DA (2015) Projected changes in extreme temperature events based on the NARCCAP model suite. Geophys Res Lett:1–10. doi:10.1002/2015GL064914

Horton RM, Mankin JS, Lesk C, Coffel E, Raymond C (2016) A review of recent advances in research on extreme heat events. Curr Clim Chang Rep 2:242–259

ICAO (2016) Environmental report

Karl TR et al (2015) Possible artifacts of data biases in the recent global surface warming hiatus. Science 348(80):1469–1472

Kharin VV, Zwiers FW, Zhang X, Hegerl GC (2007) Changes in temperature and precipitation extremes in the IPCC Ensemble of Global Coupled Model Simulations. J Clim 20:1419–1444

Knutson TR et al (2010) Tropical cyclones and climate change. Nat Geosci 3:157–163

Kodra E, Ganguly AR (2014) Asymmetry of projected increases in extreme temperature distributions. Sci Rep 4:5884

Koetse MJ, Rietveld P (2009) The impact of climate change and weather on transport: an overview of empirical findings. Transp Res Part D Transp Environ 14:205–221

Lan S, Clarke J-P, Barnhart C (2006) Planning for robust airline operations: optimizing aircraft routings and flight departure times to minimize passenger disruptions. Transp Sci 40:15–28

Mora C et al (2013) The projected timing of climate departure from recent variability. Nature 502:183–187

Moss RH et al (2010) The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 463:747–756

O’Gorman Pa, Schneider T (2009) The physical basis for increases in precipitation extremes in simulations of 21st-century climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:14773–14777

Pal JS, Eltahir EAB (2015) Future temperature in southwest Asia projected to exceed a threshold for human adaptability. Nat Clim Chang 18203:1–4

Parris, A. et al. (2012). Global sea level rise scenarios for the United States National Climate Assessment. At http://cpo.noaa.gov/sites/cpo/Reports/2012/NOAA_SLR_r3.pdf

Schär C et al (2004) The role of increasing temperature variability in European summer heatwaves. Nature 427:332–336

Sherwood SC, Huber M (2010) An adaptability limit to climate change due to heat stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:9552–9555

Stott PA, Stone DA, Allen MR (2004) Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature. doi:10.1029/2001JB001029

Taylor KE, Stouffer RJ, Meehl G a (2012) An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 93:485–498

Thompson TR (2016) Aviation and the impacts of climate change ∙ climate change impacts upon the commercial air transport industry: an overview. Carbon Clim Law Rev 10:105–112

Walsh, J. et al. (2014) Chapter 2: Our changing climate. Third US Natl. Clim. Assess

Webster PJ, Holland GJ, Curry Ja, Chang H-R (2005) Changes in tropical cyclone number, duration, and intensity in a warming environment. Science 309:1844–1846

Williams PD (2016) Transatlantic flight times and climate change. Environ Res Lett 11

Williams PD (2017) Increased light, moderate, and severe clear-air turbulence in response to climate change. Adv Atmos Sci 34:576–586

Williams PD, Joshi MM (2013) Intensification of winter transatlantic aviation turbulence in response to climate change. Nat Clim Chang 3:644–648

Yin JH (2005) A consistent poleward shift of the storm tracks in simulations of 21st century climate. Geophys Res Lett 32:1–4

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme’s Working Group on Coupled Modelling, which is responsible for the CMIP, and we thank the climate modeling groups for producing and making available their model output. For the CMIP, the US Department of Energy’s Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison provided coordinating support and led the development of software infrastructure in partnership with the Global Organization for Earth System Science Portals. Funding for this research was provided through NSF grant number DGE-11-44155 and the US DOI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.D.C. and T.R.T. jointly conceived of the study, conducted the analyses, and wrote the paper. R.M.H. provided the input at all stages.

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 16000 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coffel, E.D., Thompson, T.R. & Horton, R.M. The impacts of rising temperatures on aircraft takeoff performance. Climatic Change 144, 381–388 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-2018-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-2018-9